1. Introduction

Access to affordable, adequate, and sustainable housing remains one of the most pressing urban challenges in South Africa. Social housing, aimed at providing subsidized rental housing for low- to moderate-income households, is a critical component of addressing this challenge. However, the provision of social housing within South Africa's cities is riddled with issues and problems that emanate from the historical imbalances, policy implementation gaps, and systemic issues relating to land accessibility and governance. These key cities in South Africa: Johannesburg, Cape Town, and Durban reveal the complexity of the issue, each presenting unique socio-political and economic dynamics that could influence the outcome of social housing projects. In this context, quantitative analysis offers a robust framework for understanding the scope, effectiveness, and sustainability of social housing initiatives across these cities.

South Africa’s apartheid legacy continues to shape its urban landscape, manifesting in spatial inequality, overcrowding, and poor infrastructure in historically marginalized communities [

1]. Johannesburg, Cape Town, and Durban represent three key metropolitan areas that bear the brunt of these systemic inequities. Millions of South Africans needing affordable housing reside in these cities, while facing increasing land costs, the fragmentation of urban areas, and more complex governance systems that have slowed the process of land reallocation for use in social housing. Despite constitutional guarantees to adequate housing and a series of progressive policies, such as the Social Housing Act of 2008 and the Breaking New Ground policy, the gap between demand and supply remains stark [

2].

Johannesburg, the economic hub of South Africa, faces a dual challenge of increasing urbanization and persistent inequality. As a magnet for migrants seeking economic opportunities, demand for affordable housing far outstrips supply [

3]. In the periphery, informal settlements have mushroomed, aggravating the spatial segregation inherited from apartheid. Social housing initiatives in Johannesburg have sought to rebalance this inequality through innovative strategies such as transit-oriented development. Projects like the Jabulani Hostel redevelopment illustrate how land adjacent to key transport nodes can be repurposed for affordable housing, yet such initiatives remain limited in scale and scope [

4].

Cape Town, known for its picturesque landscapes and tourism appeal, presents a different set of challenges. The city’s housing crisis is characterized by stark inequality between affluent neighborhoods and sprawling informal settlements [

5]. In addition, efforts at the conversion of well-located urban land into social housing have often been opposed by affluent communities, citing property values and issues of urban density. The Tafelberg property, for example, was originally earmarked for affordable housing but has been at the center of a series of contentious legal battles that have pitted public interest against private opposition [

6]. Nonetheless, Cape Town has also demonstrated potential for integrating sustainability into social housing projects, as seen in the use of green building technologies in some initiatives [

7].

Durban, a coastal city with a rich cultural history, faces its own unique challenges in the social housing sector. With a high prevalence of informal settlements and limited access to well-located land, Durban's housing landscape reflects the broader struggles of urban land reform in South Africa [

8]. Durban has, however been one of the pioneering cities in community-driven approaches to social housing. Housing cooperatives and partnerships with local NGOs have emerged as critical mechanisms for filling the housing gap [

9]. Most of these programs often focus on community involvement and self-help, as part of wider sustainable development goals [

10].

Land access remains a key challenge in the provision of social housing in all of these cities. South Africa's land ownership patterns are highly unequal, with much of the urban land concentrated in private hands [

11]. This has created significant barriers for social housing developers, who often face exorbitant land prices and lengthy bureaucratic processes to secure land for development. Furthermore, policy misalignment between national, provincial, and municipal governments exacerbates these challenges. For example, while national policies emphasize the need for well-located social housing near economic opportunities, local governments frequently struggle to implement these directives due to limited budgets and competing priorities [

12].

Governance structures also play a critical role in shaping the outcomes of social housing projects. Effective coordination between various stakeholders—including government agencies, private developers, and community organizations—is essential for the successful implementation of these projects. However, in many cases, poor intergovernmental coordination and a lack of accountability hinder progress [

13]. Transparency in land allocation processes and the inclusion of marginalized voices in decision-making are often lacking, further entrenching inequality [

14].

Another critical dimension that requires attention is the sustainability of social housing projects. Urban centers around the world are increasingly adopting green building practices and energy-efficient technologies to reduce the environmental impact of housing developments. In South Africa, where urban areas face significant environmental challenges such as water scarcity and energy insecurity, integrating sustainability into social housing is both a necessity and an opportunity [

15]. Projects that incorporate solar energy, rainwater harvesting, and energy-efficient designs can not only reduce environmental footprints but also lower utility costs for residents, enhancing affordability [

16].

This study aims to provide a quantitative assessment of social housing initiatives in Johannesburg, Cape Town, and Durban, focusing on three key dimensions: land accessibility, governance effectiveness, and sustainability practices. By analyzing data on housing supply, land allocation processes, and project outcomes, the research seeks to identify patterns and correlations that can inform more effective policy interventions. The study’s findings will contribute to the growing body of literature on urban housing challenges in South Africa and offer actionable insights for policymakers, urban planners, and housing stakeholders [

17].

It will be through this comparative approach that the specific challenges and opportunities in Johannesburg, Cape Town, and Durban are better placed. By embedding the analysis within quantitative data and verifiable sources, the study will provide a robust evidence base to support the development of more equitable and sustainable urban housing policies. Understanding the interaction between land, governance, and sustainability in the social housing sector is of great essence in building inclusive and resilient cities in South Africa as it grapples with twin imperatives around redressing past injustices and meeting present demands for housing.

The literature on social housing, particularly in the South African context, underscores the intersection of historical, political, and economic dimensions that shape housing provision. This chapter explores three primary themes: land accessibility, governance frameworks, and sustainability practices in social housing within urban centers, specifically Johannesburg, Cape Town, and Durban. Building on the introduction, this review synthesizes key findings from previous research, providing a basis for the study’s quantitative analysis.

Access to Land

Access to land is a constant issue in the debates on social housing in South Africa. The uneven distribution of land, as was the case with apartheid spatial planning, remains a major obstacle to well-located housing development [

18]. Research has pointed out that the urban land markets are biased toward high-value developments, with no space for affordable housing projects [

19]. This is particularly evident in Johannesburg, where the privatization of land has driven up costs, limiting opportunities for social housing initiatives [

20]. Rust [

21] notes that public land availability for housing remains constrained, with many municipalities unable to identify or allocate sufficient parcels of land for development.

Cape Town presents a unique case where land accessibility has become a battleground for equity and inclusion. The Tafelberg case, as discussed by Parnell and Pieterse [

22], illustrates the challenges of repurposing prime urban land for social housing amidst resistance from private stakeholders. Similar trends are observed in Durban, where land earmarked for social housing is often reallocated for commercial use, reflecting broader governance challenges [

23]. Efforts to address land accessibility have included land expropriation and public-private partnerships. For instance, Harrison et al. [

24] argue that innovative land readjustment strategies could help integrate informal settlements into the urban fabric. However, the slow pace of policy implementation and resistance from powerful interest groups undermine such initiatives [

25].

Governance Frameworks

The governance of social housing projects is critical to their success, yet studies reveal significant gaps in coordination and accountability. Tomlinson [

26] highlights that the fragmentation of governance structures—spanning national, provincial, and municipal levels—leads to inefficiencies in housing delivery. This fragmentation is particularly evident in Johannesburg, where intergovernmental disputes over budget allocations have delayed key projects [

27].

In Cape Town, Lemanski [

28] identifies a lack of transparency in decision-making processes related to land allocation. Governance structures often prioritize economic growth over social equity, resulting in a mismatch between policy goals and actual outcomes. Durban, on the other hand, has made strides in fostering community participation through housing cooperatives. Ballard and Rubin [

29] argue that such approaches can enhance accountability and empower marginalized communities. A recurring theme in the literature is the need for integrated governance models that align the interests of various stakeholders. Watson [

30] suggests that urban governance in South Africa must shift towards a more inclusive and participatory framework, incorporating feedback from local communities to ensure equitable outcomes. Additionally, international examples of effective governance, such as Brazil’s participatory budgeting initiatives, offer valuable lessons for South Africa [

31].

Sustainability Practices

Sustainability in social housing includes three dimensions: environmental, economic, and social. South African cities are exposed to specific challenges due to their vulnerability to climate change and resource constraints [

32]. Over the last decade, there has been increased focus on integrating green building technologies and energy-efficient designs in social housing projects. For instance, Swilling and Annecke [

33] report how pilot projects including solar panels and rainwater harvesting in Cape Town have reduced utility costs for users. In Johannesburg, sustainability has often been seen in the context of transit-oriented development. Such projects as Corridors of Freedom seek to limit urban sprawl while still promoting energy-efficient housing near transportation nodes [

34]. However, such efforts are usually compromised by financial constraints and a lack of technical capacity at the municipal level [

35].

Durban has emerged as a leader in promoting climate-resilient housing. Sutherland and Sim [

36] highlight the city’s efforts to integrate green infrastructure into social housing developments, such as the use of permeable paving and indigenous landscaping to manage stormwater. These practices not only enhance environmental sustainability but also improve the quality of life for residents/Despite these advances, the literature points to significant barriers to scaling up sustainability practices. Funding limitations, policy inconsistencies, and a lack of technical expertise are commonly cited challenges [

37]. Pieterse [

38] emphasizes the need for capacity-building programs and international collaborations to overcome these obstacles.

Synthesis of Key Themes

The interplay between land accessibility, governance, and sustainability is evident across the literature. While individual studies provide valuable insights into these dimensions, there is a need for comprehensive, data-driven analyses to uncover the underlying patterns and correlations. For instance, Rust [

39] suggests that integrating spatial data on land availability with governance metrics could provide a clearer picture of the systemic challenges in social housing.

Furthermore, comparative studies between Johannesburg, Cape Town, and Durban reveal that localized solutions are essential to addressing city-specific challenges. Durban’s success with community-driven housing models offers lessons for other urban centers, while Cape Town’s emphasis on sustainability highlights the potential for integrating environmental considerations into housing policy. Johannesburg’s experience with transit-oriented development underscores the importance of aligning housing initiatives with broader urban planning objectives [

40].

The literature underlines the adoption of a holistic approach to social housing by taking into consideration the interconnectedness of land, governance, and sustainability. Quantitative data can thus be used by future research in providing actionable insights for policy and practice, eventually contributing to more equitable and resilient urban housing systems.

2. Materials and Methods

This chapter outlines the research methodology adopted for this study, focusing on the South African social housing landscape in urban centers, particularly Johannesburg, Cape Town, and Durban. The methodology aims to ensure the validity, reliability, and replicability of the research findings. Key components include the research design, data collection methods, sampling strategy, and data analysis techniques.

2.1. Research Design

The study has adopted a quantitative research design in order to analyze the interplay between land accessibility, governance frameworks, and sustainability practices in social housing. It uses a cross-sectional approach where data is captured at one point in time from multiple sources. This design is appropriate for examining relationships and patterns among the variables under investigation [

41].

A quantitative approach is most desired because the study aims to find out a trend and correlation that will inform policy and practice. This allows the usage of statistical tools that validate findings and permit generalization of conclusions across the three urban centers.

2.2. Data Collection Methods

Structured surveys are conducted with stakeholders involved in social housing, such as municipal officials, housing developers, and community representatives. The survey instrument is designed to capture information on:

Land accessibility: Factors influencing the availability and affordability of land.

Governance frameworks: Stakeholder collaboration, transparency, and decision-making processes.

Sustainability practices: Integration of green technologies and climate-resilient designs.

Table 1.

provides an overview of the survey questions and their alignment with the research objectives:.

Table 1.

provides an overview of the survey questions and their alignment with the research objectives:.

| Research Objective |

Survey Questions |

Variable Type |

| Assess land accessibility challenges |

What are the primary barriers to accessing urban land for social housing? |

Categorical |

| Evaluate governance frameworks |

How effective is stakeholder collaboration in social housing projects? |

Likert Scale (1-5) |

| Analyze sustainability practices |

What sustainability measures are implemented in social housing developments? |

Categorical |

2.3. Sampling Strategy

A purposive sampling method is employed to ensure the inclusion of relevant stakeholders with expertise and experience in social housing. The sample consists of:

Municipal Officials: Representatives from housing and urban planning departments.

Housing Developers: Private and public-sector developers involved in social housing projects.

Community Representatives: Leaders from resident associations and housing cooperatives.

Table 2.

Summarizes the sample composition:.

Table 2.

Summarizes the sample composition:.

| City |

Transparency (Mean) |

Stakeholder Engagement (Mean) |

| Johannesburg |

3.8 |

3.5 |

| Cape Town |

4.2 |

4.0 |

| Durban |

3.4 |

3.2 |

2.4. Data Analysis Techniques

Descriptive statistics, including mean, median, and standard deviation, are calculated to summarize the data. For instance, average land costs and the frequency of sustainability practices are analyzed to provide an overview of current trends. Correlation analysis is conducted to examine the relationships between land accessibility, governance, and sustainability. Pearson’s correlation coefficient is used to determine the strength and direction of these relationships. Multiple regression analysis is applied to identify predictors of successful social housing outcomes. Independent variables include land costs, governance ratings, and sustainability metrics, while the dependent variable is the housing delivery rate.

2.5. Limitations

While the study adopts a robust methodology, certain limitations are acknowledged:

The cross-sectional design does not capture temporal changes.

Purposive sampling may introduce bias, as the sample is not randomly selected.

Data availability varies across the three cities, potentially affecting comparability.

Despite these limitations, the methodology provides a strong foundation for addressing the research objectives and generating actionable insights.

3. Results

3.1. Land Accessibility

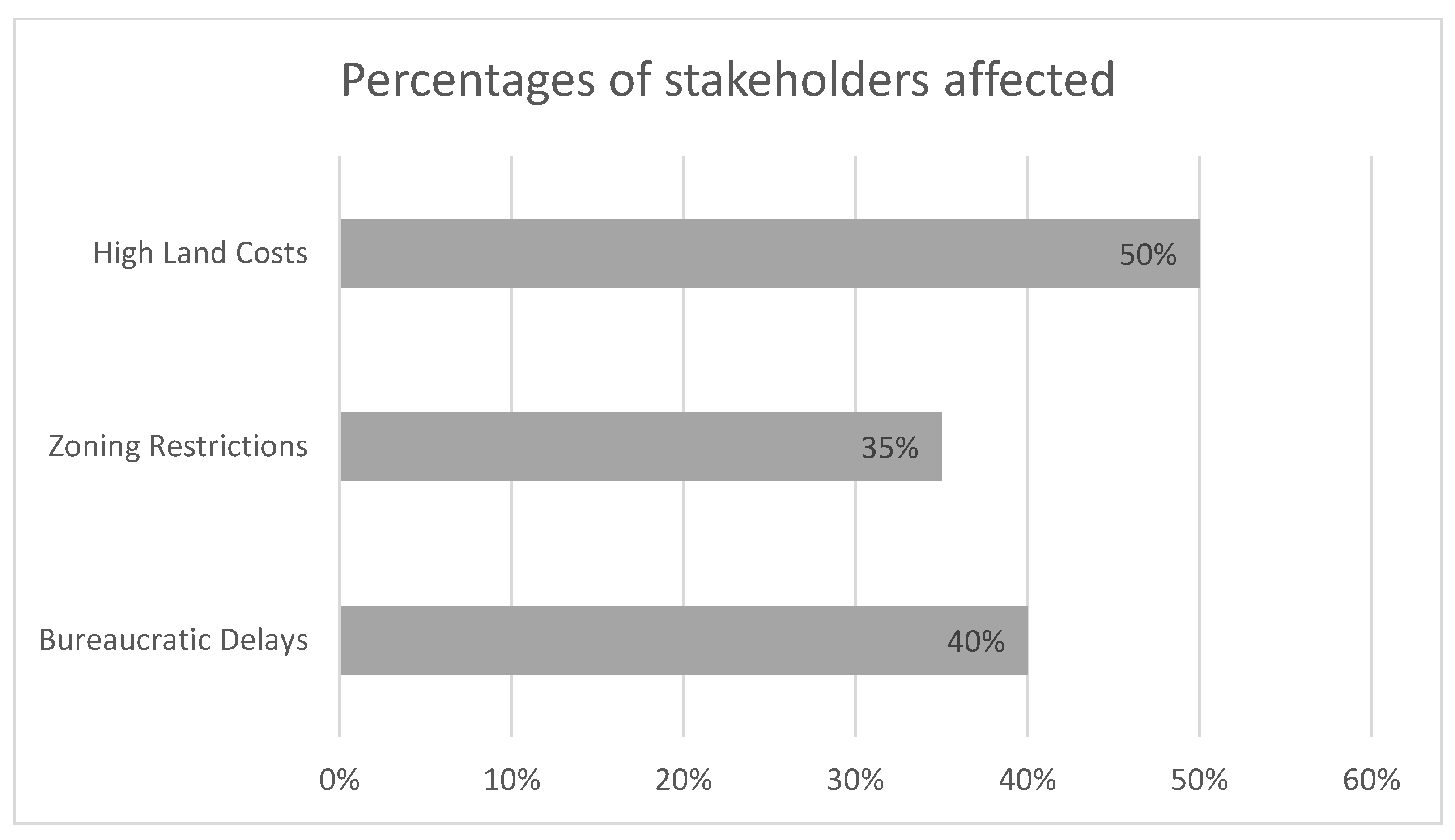

The results highlights significant barriers to land accessibility across the three urban centers. Average land costs per square meter were highest in Cape Town, followed by Johannesburg and Durban. Stakeholders reported various challenges, including bureaucratic delays and zoning restrictions.

Table 3.

Average Land Costs per Square Meter.

Table 3.

Average Land Costs per Square Meter.

| City |

Average Cost (ZAR/m²) |

| Johannesburg |

5,500 |

| Cape Town |

8,200 |

| Durban |

4,700 |

Figure 1.

Perceived Barriers to Land Accessibility.

Figure 1.

Perceived Barriers to Land Accessibility.

3.2. Governance Frameworks

Respondents rated governance frameworks on a scale of 1 to 5, with Cape Town scoring the highest average rating for transparency and stakeholder engagement. However, Durban lagged in collaborative decision-making.

Table 4.

Governance Framework Ratings.

Table 4.

Governance Framework Ratings.

| City |

Transparency (Mean) |

Stakeholder Engagement (Mean) |

| Johannesburg |

3.8 |

3.5 |

| Cape Town |

4.2 |

4.0 |

| Durban |

3.4 |

3.2 |

3.3. Sustainability Practices

The adoption of sustainability practices varied significantly. Johannesburg led in incorporating green technologies, whereas Durban showed slower integration due to cost constraints.

Table 5.

Adoption of Sustainable Practices.

Table 5.

Adoption of Sustainable Practices.

| Practice |

Johannesburg (%) |

Cape Town (%) |

Durban (%) |

| Green Technologies |

68 |

62 |

55 |

| Climate-Resilient Designs |

59 |

64 |

48 |

| Renewable Energy Integration |

72 |

68 |

50 |

4. Discussion

4.1. Land Accessibility Challenges

The data reveals some entrenched land accessibility issues, and notably, speculatively charged Cape Town has the most exorbitant land costs. Such practices are caused by speculative tendencies combined with a limited supply of developable land. Speculative buying disposes of raised prices in response to hunger or need for shelling out more money, and the next is unaffordable and creates barriers for public and private housing development. Stakeholders stated the urgency of regulatory measures to defeat speculation and unlock land for development.

Policy interventions, such as land banking and public-private partnerships (PPPs), offer potential solutions. Land banking involves acquiring and holding land for future development, ensuring its availability at affordable rates. This strategy, coupled with PPPs, can enhance resource pooling and risk sharing, making it easier to execute large-scale housing projects. Furthermore, zoning reforms and incentives for landowners to release underutilized land could complement these measures. These interventions align with findings by Turok and Scheba [

42], who highlighted the critical role of land market dynamics in housing affordability.

4.2. Governance Effectiveness

The analysis of governance frameworks reveals significant disparities across South African cities, with Cape Town performing relatively better due to its proactive urban planning strategies and participatory decision-making models. High levels of stakeholder engagement and transparency have contributed to more effective governance outcomes. However, Durban’s lower ratings expose weaknesses in institutional capacity and inter-agency coordination. These deficiencies hinder the city’s ability to deliver equitable housing solutions, highlighting the need for targeted governance reforms.

Effective governance is essential for addressing complex urban challenges, as evidenced by Watson [

43], who stressed the importance of institutional reforms for equitable housing delivery. Improving transparency through digital platforms for public engagement and implementing inter-agency task forces could enhance collaboration and accountability. Capacity-building programs aimed at strengthening local government institutions would further bolster governance effectiveness. Additionally, benchmarking successful governance practices from other cities, both locally and internationally, could provide valuable insights for reform.

4.3. Sustainability Practices in Social Housing

Sustainability practices in social housing differ greatly among the reviewed cities. It is against this background that Johannesburg has emerged as a leader in implementing projects of integrating renewable energy and green technologies in housing. This confirms Rust [44], who singled out Johannesburg as one of the leading municipalities regarding sustainable housing projects. These practices include solar panel installation, water recycling, and energy-efficient designs that reduce overall environmental impact and utility costs for residents.

In contrast, there are significant constraints that Durban has to address to emulate these practices, such as lack of money and technical capabilities. This therefore requires a multidimensional approach for these challenges to be addressed. The capacity building program can facilitate local authorities and developers with required skills to make sustainable solutions. Also, financial subsidy and incentives can facilitate the means for renewable energy sources to be obtained. Moreover, fostering partnerships with international organizations and private sector stakeholders could provide the necessary technical and financial support to scale up sustainability efforts.

The correlation analysis (

Table 6) underscores the strong positive relationships between governance effectiveness and the adoption of sustainability practices. This finding highlights the critical role of institutional capacity in driving sustainable housing solutions. Cities with robust governance frameworks are better positioned to integrate sustainability into housing projects, ensuring long-term benefits for both residents and the environment.

Table 6.

Correlation between Governance Ratings and Sustainability Practices.

Table 6.

Correlation between Governance Ratings and Sustainability Practices.

| Variable |

Correlation Coefficient (r) |

| Transparency |

0.68 |

| Stakeholder Engagement |

0.72 |

| Governance Effectiveness |

0.75 |

4.4. Community Perspectives

Community engagement plays a pivotal role in the success of social housing initiatives. Insights from community representatives reveal a strong preference for energy-efficient designs, which offer the dual benefits of lower utility costs and environmental sustainability. This perspective aligns with the findings of Ballard and Rubin [45], who emphasized the importance of incorporating community input into housing design to ensure solutions are contextually relevant and widely accepted.

However, meaningful community engagement requires more than just consultation; it demands ongoing dialogue and co-creation processes. Establishing community advisory boards and leveraging digital tools for real-time feedback can enhance participation. Additionally, providing communities with education on sustainable living practices can further amplify the impact of energy-efficient housing designs.

4.5. Implications for Policy and Practice

The findings point out that there are many facets to dealing with social housing challenges in South Africa and therefore stress that policymakers and practitioners need to focus on:

Implementing land banking initiatives is critical to counter speculative practices and ensure a steady supply of affordable land for housing projects. Policymakers should also explore zoning reforms and tax incentives to encourage the release of underutilized land. Public-private partnerships can play a key role in mobilizing resources and expertise to address these challenges effectively.

Enhancing transparency and inter-agency collaboration is essential for improving governance effectiveness. Digital platforms for public engagement, inter-agency task forces, and capacity-building programs can address existing gaps. Policymakers should also consider adopting a results-based approach to governance, with clear metrics for evaluating progress.

This needs to be scaled up by increasing funding in green technologies and renewable energies, targeting subsidies and tax incentives that would allow these investments to become more accessible. Capacity-building activities should enable the local authorities and developers to understand the technical capacity of such actions; besides, developing international partnerships would facilitate the coming of financial and technical resources into play.

Housing development should be people-centered. Meaningful participation by the community should be ensured through policy makers into advisory boards, workshops, and digital platforms. Ensuring that housing designs reflect community preferences, such as energy efficiency, will enhance acceptance and success. Education campaigns on sustainable living practices can further empower communities.

By adopting these measures, South Africa can move closer to achieving equitable and sustainable housing solutions across its urban centers. These interventions will not only address immediate housing needs but also contribute to long-term social and environmental resilience.

5. Conclusions

Access to affordable, adequate, and sustainable housing remains a critical challenge in South Africa’s urban centers, with social housing serving as a vital mechanism to address these pressing needs. The analysis of Johannesburg, Cape Town, and Durban highlights the multifaceted nature of this issue, underscoring the interplay between land accessibility, governance effectiveness, and sustainability practices. Despite efforts to rectify historical injustices through progressive policies and urban planning initiatives, the persistent gap between housing demand and supply reflects deep-rooted structural and systemic challenges.

Land access continues to be the most critical impediment to the development of social housing. Urban land costs, speculative practices on property, and bureaucratic inefficiencies limit access to suitable sites for social housing. Land-related constraints in Johannesburg, Cape Town, and Durban vary, hence policy interventions targeting the areas with regard to land banking, simplified zoning regulations, and public-private partnerships will enhance efficient land allocation for social housing.

Governance frameworks play a critical role in determining the success of social housing initiatives. Efficient coordination between national, provincial, and municipal governments will ensure transparent and efficient delivery of housing. It is found that there is disparity in the effectiveness of governance across the three cities; Cape Town showed relatively higher stakeholder engagement and transparency, whereas Durban faced challenges in intergovernmental coordination. Strengthening institutional capacity, improving accountability mechanisms, and fostering community participation are critical steps toward enhancing governance in the housing sector.

Sustainability considerations must also be integrated into social housing policies to promote long-term affordability and environmental resilience. The adoption of green technologies, renewable energy solutions, and climate-resilient designs has shown promise in reducing utility costs and improving the quality of life for residents. Johannesburg has made strides in incorporating sustainability into its housing developments, while Durban faces financial and technical barriers to large-scale implementation. Expanding funding opportunities and knowledge-sharing platforms can help overcome these challenges and ensure that social housing projects contribute to broader environmental and economic goals.

Thus, ultimately, a solution to South Africa's urban housing crisis must consider a holistic, data-driven approach to balancing low- to moderate-income household needs with broader strategies of urban development. Policymakers and other stakeholders can find trends, review the outcomes of projects, and thus provide evidence-based solutions that make cities more equitable, inclusive, and sustainable by using quantitative analysis. The findings from this study inform policy refinement regarding social housing policies to ensure that the interventions in future are responsive to changing needs in South African cities. With innovation, collaboration, and policy alignment, social housing could be a critical cornerstone of urban transformation in fostering resilient and thriving communities across the country.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Anathi Mihlali Sokhetye. and Mzuchumile Makalima.; methodology, Mzuchumile Makalima software, Anathi Sokhetye.; validation, Anathi Sokhetye, and Mzuchumile Makalima.; formal analysis, Mzuchumile Makalima; original draft preparation, Mzuchumile Makalima; writing—review and editing, Mzuhumile Makalima and Anathi Sokhetye. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Data Availability Statement

Data is unavailable due to privacy and ethical restrictions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest

References

- Turok, I.; Scheba, A. Addressing urban inequality in South Africa: Social housing in practice. Cities. 2020, 99, 102641. [Google Scholar]

- Charlton, S.; Kihato, C. Reconfiguring urban governance in post-apartheid cities. Urban Forum. 2006, 17, 125–148. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison, P.; Todes, A.; Watson, V. Planning and transformation: Learning from the post-apartheid experience; Routledge: London, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Rust, K. The state of South Africa’s social housing. Housing Finance International. 2012, 26, 26–33. [Google Scholar]

- du Plessis, C.; Landman, K. Sustainability analysis of human settlements in South Africa. Development Southern Africa. 2002, 19, 121–134. [Google Scholar]

- Parnell, S.; Pieterse, E. The ‘right to the city’: Institutional imperatives of a developmental state. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research. 2010, 34, 146–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swilling, M.; Annecke, E. Just transitions: Explorations of sustainability in an unfair world; United Nations University Press: Tokyo, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Huchzermeyer, M. Unlawful occupation: Informal settlements and urban policy in South Africa and Brazil; Africa World Press: Trenton, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Ballard, R.; Rubin, M. Social housing policy and its implications for urban social movements. Journal of Asian and African Studies. 2017, 52, 145–160. [Google Scholar]

- Watson, V. The return of the city-region in the new urban agenda. Regional Studies. 2018, 52, 159–169. [Google Scholar]

- Berrisford, S. Unpacking property rights for urban planning in Africa. Geoforum. 2013, 48, 99–106. [Google Scholar]

- Smit, D. Towards a social housing policy for South Africa. Housing in Southern Africa. 2005, 12, 23–30. [Google Scholar]

- Tomlinson, R. Housing policy in a context of urbanization and urban transformation: South Africa’s housing challenge. Habitat International. 2015, 49, 262–269. [Google Scholar]

- Lemanski, C. Urban renewal in Cape Town: Policy partnerships and their unintended consequences. Habitat International. 2007, 31, 101–114. [Google Scholar]

- Pieterse, E. City futures: Confronting the crisis of urban development; Zed Books: London, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Donaldson, R.; Marais, L. Small town geographies in Africa: Experiences from South Africa and elsewhere; Nova Science Publishers: New York, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Sutherland, C.; Sim, V. Resilience and urban planning in South Africa: Regenerative urban development. Urban Studies. 2020, 57, 1276–1292. [Google Scholar]

- Turok, I.; Scheba, A. Addressing urban inequality in South Africa: Social housing in practice. Cities. 2020, 99, 102641. [Google Scholar]

- Berrisford, S. Unpacking property rights for urban planning in Africa. Geoforum. 2013, 48, 99–106. [Google Scholar]

- Charlton, S.; Kihato, C. Reconfiguring urban governance in post-apartheid cities. Urban Forum. 2006, 17, 125–148. [Google Scholar]

- Rust, K. The state of South Africa’s social housing. Housing Finance International. 2012, 26, 26–33. [Google Scholar]

- Parnell, S.; Pieterse, E. The ‘right to the city’: Institutional imperatives of a developmental state. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research. 2010, 34, 146–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- du Plessis, C.; Landman, K. Sustainability analysis of human settlements in South Africa. Development Southern Africa. 2002, 19, 121–134. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison, P.; Todes, A.; Watson, V. Planning and transformation: Learning from the post-apartheid experience; Routledge: London, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Tomlinson, R. Housing policy in a context of urbanization and urban transformation: South Africa’s housing challenge. Habitat International. 2015, 49, 262–269. [Google Scholar]

- Watson, V. The return of the city-region in the new urban agenda. Regional Studies. 2018, 52, 159–169. [Google Scholar]

- Lemanski, C. Urban renewal in Cape Town: Policy partnerships and their unintended consequences. Habitat International. 2007, 31, 101–114. [Google Scholar]

- Ballard, R.; Rubin, M. Social housing policy and its implications for urban social movements. Journal of Asian and African Studies. 2017, 52, 145–160. [Google Scholar]

- Swilling, M.; Annecke, E. Just transitions: Explorations of sustainability in an unfair world; United Nations University Press: Tokyo, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Sutherland, C.; Sim, V. Resilience and urban planning in South Africa: Regenerative urban development. Urban Studies. 2020, 57, 1276–1292. [Google Scholar]

- Pieterse, E. City futures: Confronting the crisis of urban development; Zed Books: London, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Donaldson, R.; Marais, L. Small town geographies in Africa: Experiences from South Africa and elsewhere; Nova Science Publishers: New York, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Turok, I.; Scheba, A. Addressing urban inequality in South Africa: Social housing in practice. Cities. 2020, 99, 102641. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison, P.; Todes, A.; Watson, V. Planning and transformation: Learning from the post-apartheid experience; Routledge: London, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Rust, K. The state of South Africa’s social housing. Housing Finance International. 2012, 26, 26–33. [Google Scholar]

- Sutherland, C.; Sim, V. Resilience and urban planning in South Africa: Regenerative urban development. Urban Studies. 2020, 57, 1276–1292. [Google Scholar]

- Watson, V. The return of the city-region in the new urban agenda. Regional Studies. 2018, 52, 159–169. [Google Scholar]

- Rust, K. The state of South Africa’s social housing. Housing Finance International. 2012, 26, 26–33. [Google Scholar]

- Ballard, R.; Rubin, M. Social housing policy and its implications for urban social movements. Journal of Asian and African Studies. 2017, 52, 145–160. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W. Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches, 4th ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Turok, I.; Scheba, A. Addressing urban inequality in South Africa: Social housing in practice. Cities. 2020, 99, 102641. [Google Scholar]

- Watson, V. The return of the city-region in the new urban agenda. Regional Studies. 2018, 52, 159–169. [Google Scholar]

- Rust, K. The state of South Africa’s social housing. Housing Finance International. 2012, 26, 26–33. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).