Submitted:

29 January 2025

Posted:

30 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

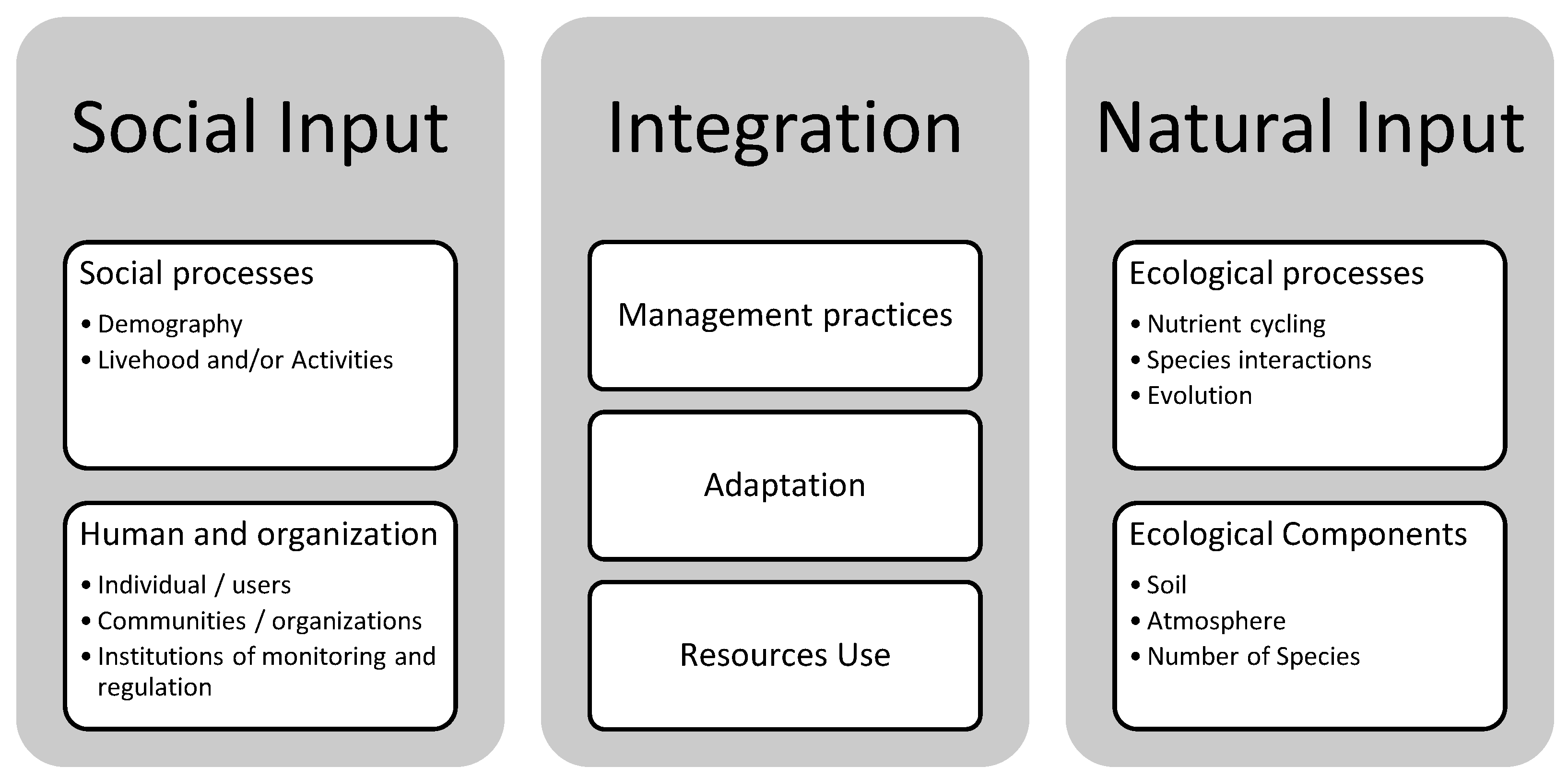

2.1. Beaches as Socio Ecological-Systems

2.2. Traditional Beach Monitoring

2.3. Perceptions of beachgoers’ Anti-Social Behavior and Their Implication for Beach/Destination Management

2.4. Crowding

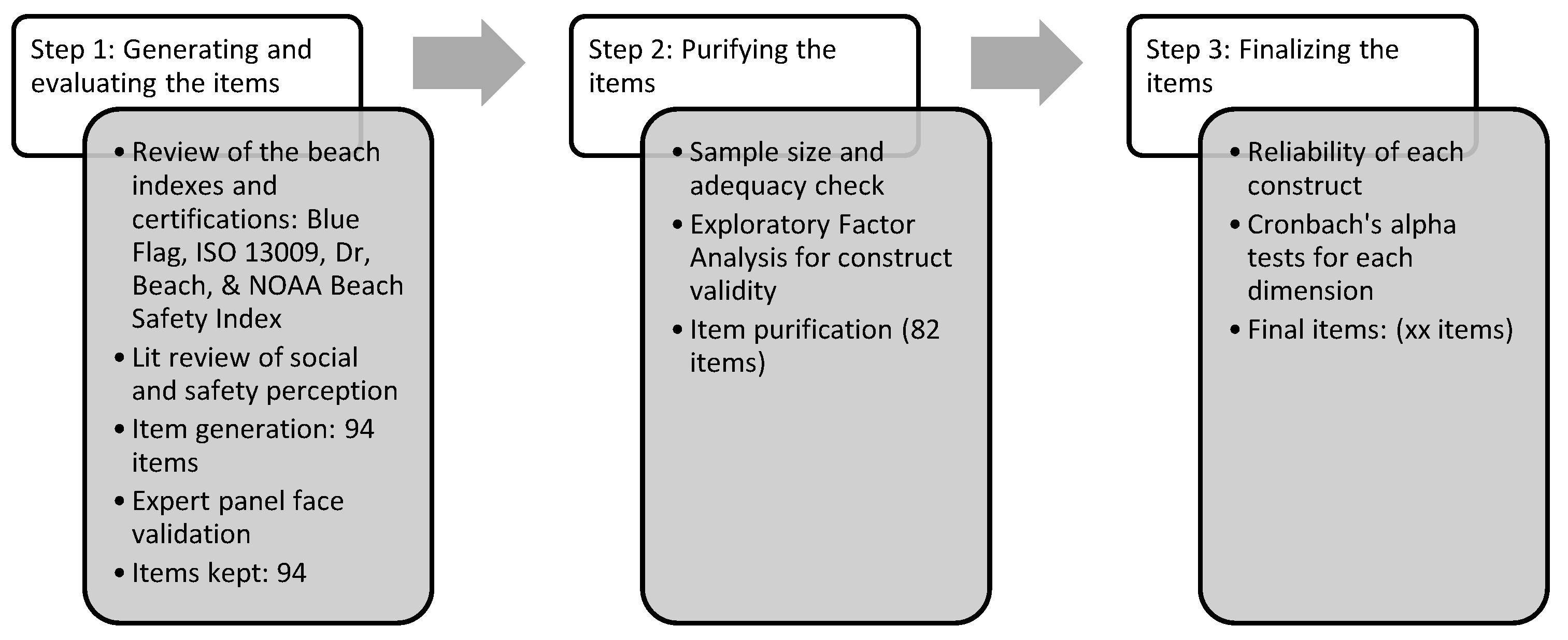

3. Methods

3.1. First Step: Generating and Evaluating Items

3.2. Second Step: Purifying Items

3.3. Third Step: Finalizing Items

4. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions and Limitations

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CIB | Comprehensive Index for Beaches |

| EFA | Exploratory Factor Analysis |

| SES | Socio-Ecological Systems |

References

- World Bank. Sustainable tourism can drive the blue economy. Available online: https://blogs.worldbank.org/en/voices/Sustainable-Tourism-Can-Drive-the-Blue-Economy (accessed on 27 January 2025).

- Dodds, R.; Holmes, M.R. Beach tourists: What factors satisfy them and drive them to return. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2019, 168, 158–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Micallef, A.; Williams, A. Beach Management: Principles and Practice; Routledge: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Ariza, E.; Pons, F.; Breton, F. Is “socio-ecological culture” really being taken into account to manage conflicts in the coastal zone? Inputs from Spanish Mediterranean beaches. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2016, 134, 183–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.L.; Bau, Y.P. Establishing a multi-criteria evaluation structure for tourist beaches in Taiwan: A foundation for sustainable beach tourism. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2016, 121, 88–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houston, J.R. The economic value of beach nourishment in South Carolina. Shore Beach 2021, 89, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staines, C.; Morgan, D.; Ozanne-Smith, J. Threats to tourist and visitor safety at beaches in Victoria, Australia. Tour. Mar. Environ. 2005, 1, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariza, E.; Jimenez, J.A.; Sarda, R.; Villares, M. Proposal for an integral quality index for urban and urbanized beaches. Environ. Manag. 2010, 45, 965–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lucrezi, S.; Saayman, M.; Van der Merwe, P. An assessment tool for sandy beaches: A case study for integrating beach description, human dimension, and economic factors to identify priority management issues. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2016, 134, 84–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arozarena Llopis, I.; Gutiérrez Echeverría, A. Management Tools for Safety in Costa Rica Beaches. In Beach Management Tools—Concepts, Methodologies and Case Studies; Botero, C.M., Pereira, C., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 441–467. [Google Scholar]

- Roca, E.; Villares, M. Integrating social perceptions in beach management. In Beach Management Tools—Concepts, Methodologies and Case Studies; Botero, C.M., Pereira, C., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 875–893. [Google Scholar]

- Wilks, J.; Pendergast, D. Beach safety and millennium youth: Travellers and sentinels. In Tourism and Generation Y.; Benckendorff, P., Moscardo, G., Pendergast, D., Eds.; CABI: Wallingford, UK, 2009; pp. 98–108. [Google Scholar]

- Uebelhoer, L.; Koon, W.; Harley, M.D.; Lawes, J.C.; Brander, R.W. Characteristics and beach safety knowledge of beachgoers on unpatrolled surf beaches in Australia. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2022, 22, 909–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). [Title of the document if available]. Available online: https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/156293 (accessed on 27 January 2025).

- Sohn, J.I.; Alakshendra, A.; Kim, H.J.; Kim, K.H.; Kim, H.D. Understanding the new characteristics and development strategies of coastal tourism for post-COVID-19: A case study in Korea. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saayman, M.; Saayman, A. How important are Blue Flag awards in beach choice? J. Coast. Res. 2017, 33, 1436–1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennington-Gray, L.; Schroeder, A.; Wu, B.; Donohoe, H.; Cahyanto, I. Travelers’ perceptions of crisis preparedness certification in the United States. J. Travel Res. 2014, 53, 353–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, L.; Dodds, R. Perceived effectiveness of Blue Flag certification as an environmental management tool along Ontario’s Great Lakes beaches. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2017, 141, 107–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, J.E.; Kaiser, R.A.; Steele, R.J. Perceptions of beach safety: A comparison of beach users and managers. Coast. Manag. 1989, 17, 349–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Short, A.D.; Hogan, C.L. Rip currents and beach hazards: Their impact on public safety and implications for coastal management. J. Coast. Res. 1994, 10, 197–209. [Google Scholar]

- Sardá, R.; Valls, J.F.; Pintó, J.; Ariza, E.; Lozoya, J.P.; Fraguell, R.M.; Jimenez, J.A. Towards a new integrated beach management system: The ecosystem-based management system for beaches. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2015, 118, 167–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colford, J.M., Jr.; Wade, T.J.; Schiff, K.C.; Wright, C.C.; Griffith, J.F.; Sandhu, S.K.; Weisberg, S.B. Water quality indicators and the risk of illness at beaches with nonpoint sources of fecal contamination. Epidemiology 2007, 18, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pranzini, E.; Pezzini, G.; Anfuso, G.; Botero, C.M. Beach safety management. In Beach Management Tools—Concepts, Methodologies and Case Studies; Botero, C.M., Pereira, C., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 397–420. [Google Scholar]

- Brander, R.W.; Williamson, A.; Dunn, N.; Hatfield, J.; Sherker, S.; Hayen, A. Evaluating the effectiveness of a science-based community beach safety intervention: The Science of the Surf (SOS) presentation. Cont. Shelf Res. 2022, 241, 104722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, R.J. From beaches to beach environments: Linking the ecology, human use, and management of beaches in Australia. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2000, 43, 495–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poe, M.R.; Norman, K.C.; Levin, P.S. Cultural dimensions of socioecological systems: Key connections and guiding principles for conservation in coastal environments. Conserv. Lett. 2014, 7, 166–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stojanovic, T.; McNae, H.M.; Tett, P.; Potts, T.W.; Reis, J.; Smith, H.D.; Dillingham, I. The “social” aspect of social-ecological systems: A critique of analytical frameworks and findings from a multisite study of coastal sustainability. Ecol. Soc. 2016, 21. [Google Scholar]

- Berkes, F.; Colding, J.; Folke, C. (Eds.) Navigating Social-Ecological Systems: Building Resilience for Complexity and Change; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- McGinnis, M.D.; Ostrom, E. Social-ecological system framework: Initial changes and continuing challenges. Ecol. Soc. 2014, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basurto, X.; Gelcich, S.; Ostrom, E. The social–ecological system framework as a knowledge classificatory system for benthic small-scale fisheries. Glob. Environ. Change 2013, 23, 1366–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Defeo, O. Sandy beach fisheries as complex social-ecological systems: Emerging paradigms for research, management, and governance. In Sandy Beaches and Coastal Zone Management, Proceedings of the Fifth International Symposium on Sandy Beaches, Rabat, Morocco, 11–12 September 2011; Travaux de l’Institut Scientifique: Rabat, Morocco, 2011; pp. 111–112. [Google Scholar]

- Leslie, H.M.; Basurto, X.; Nenadovic, M.; Sievanen, L.; Cavanaugh, K.C.; Cota-Nieto, J.J.; Aburto-Oropeza, O. Operationalizing the social-ecological systems framework to assess sustainability. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 5979–5984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cumming, G.S. Theoretical frameworks for the analysis of social–ecological systems. In Social-Ecological Systems in Transition; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2014; pp. 3–24. [Google Scholar]

- Virapongse, A.; Brooks, S.; Metcalf, E.C.; Zedalis, M.; Gosz, J.; Kliskey, A.; Alessa, L. A social-ecological systems approach for environmental management. J. Environ. Manag. 2016, 178, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moffatt, S.; Kohler, N. Conceptualizing the built environment as a social–ecological system. Build. Res. Inf. 2008, 36, 248–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarda, R.; Valls, J.F.; Pintó, J.; Ariza, E.; Lozoya, J.P.; Fraguell, R.M.; Jimenez, J.A. Towards a new integrated beach management system: The ecosystem-based management system for beaches. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2015, 118, 167–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlacher, T.A.; Schoeman, D.S.; Dugan, J.; Lastra, M.; Jones, A.; Scapini, F.; McLachlan, A. Sandy beach ecosystems: Key features, sampling issues, management challenges, and climate change impacts. Mar. Ecol. 2008, 29, 70–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitman, R.L.; Nevers, M.B. Escherichia coli sampling reliability at a frequently closed Chicago beach: Monitoring and management implications. J. Environ. Health 2004, 67, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiedman, D.; Page, J.B. Drug use on the street and on the beach: Cubans and Anglos in Miami, Florida. Urban Anthropol. 1982, 11, 213–235. [Google Scholar]

- Millie, A. Anti-social behaviour, behavioural expectations and an urban aesthetic. Br. J. Criminol. 2008, 48, 379–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catalano, R.F.; Hawkins, J.D. The social development model: A theory of antisocial behavior. In Delinquency and Crime: Current Theories; Hawkins, J.D., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1996; pp. 149–197. [Google Scholar]

- Calkins, S.D.; Keane, S.P. Developmental origins of early antisocial behavior. Dev. Psychopathol. 2009, 21, 1095–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voyer, M.A.; Gollan, N. Contested spaces: We shall fight on the beaches. Available online: https://ro.uow.edu.au/lhapapers/2870/ (accessed on 27 January 2025).

- Araya López, A. Policing the ’Anti-Social’ Tourist. Mass Tourism and ’Disorderly Behaviors’ in Venice, Amsterdam, and Barcelona. Partecip. Confl. 2020, 13, 1190–1207. [Google Scholar]

- Deery, M.; Jago, L. Social impacts of events and the role of anti-social behaviour. Int. J. Event Festiv. Manag. 2010, 1, 8–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrano Giné, D.; Jurado Rota, J.; Pérez Albert, M.Y.; Bonfill Cerveró, C. The Beach Crowding Index: A tool for assessing social carrying capacity of vulnerable beaches. Prof. Geogr. 2018, 70, 412–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobsen, J.K.S.; Iversen, N.M.; Hem, L.E. Hotspot crowding and over-tourism: Antecedents of destination attractiveness. Ann. Tour. Res. 2019, 76, 53–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Ruyck, M.C.; Soares, A.G.; McLachlan, A. Social carrying capacity as a management tool for sandy beaches. J. Coast. Res. 1997, 13, 822–830. [Google Scholar]

- Kainthola, S.; Singh Kaurav, R.P. Research at the crowding and tourism: Insights. Tour. Int. Interdiscip. J. 2024, 72, 648–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarlow, P.E. Crime and tourism. In Tourism in Turbulent Times; Mansfeld, Y., Pizam, A., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2006; pp. 93–106. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, Q.; Hu, H.; Kavan, P. Factors influencing perceived crowding of tourists and sustainable tourism destination management. Sustainability 2016, 8, 976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Q.; Pearce, P. Tourist perception of crowding and management approaches at tourism sites in Xi’an. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2011, 16, 325–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, T. Residents’ perceptions on tourism impacts and quality of life: The case of Faro. Master’s Thesis, Universidade do Algarve, Faro, Portugal, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Seabra, C.; Dolnicar, S.; Abrantes, J.L.; Kastenholz, E. Heterogeneity in risk and safety perceptions of international tourists. Tour. Manag. 2013, 36, 502–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, C.; Zhang, J.; Morrison, A.M. Developing a scale to measure tourist perceived safety. J. Travel Res. 2021, 60, 1232–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, C. Field surveys of the effect of lamp spectrum on the perception of safety and comfort at night. Light. Res. Technol. 2010, 42, 313–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi Amin, F.; Rezayati, M.; van de Venn, H.W.; Karimpour, H. A mixed-perception approach for safe human–robot collaboration in industrial automation. Sensors 2020, 20, 6347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennington-Gray, L.; Schroeder, A. International tourists’ perceptions of safety and security: The role of social media. Matkailututkimus 2013, 9, 7–20. [Google Scholar]

- Barker, M.; Page, S.J.; Meyer, D. Urban visitor perceptions of safety during a special event. J. Travel Res. 2003, 41, 355–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Abdul Aziz, F.; Song, M.; Zhang, H.; Ujang, N.; Xiao, Y.; Cheng, Z. Evaluating visitor usage and safety perception experiences in national forest parks. Land 2024, 13, 1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennington-Gray, L.; Schroeder, A.; Wu, B.; Donohoe, H.; Cahyanto, I. Travelers’ perceptions of crisis preparedness certification in the United States. J. Travel Res. 2014, 53, 353–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Astrachan, C.B.; Moisescu, O.I.; Radomir, L.; Sarstedt, M.; Vaithilingam, S.; Ringle, C.M. Executing and interpreting applications of PLS-SEM: Updates for family business researchers. J. Fam. Bus. Strateg. 2021, 12, 100392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamantopoulos, A.; Winklhofer, H.M. Index construction with formative indicators: An alternative to scale development. J. Mark. Res. 2001, 38, 269–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saayman, M.; Saayman, A. How important are Blue Flag awards in beach choice? J. Coast. Res. 2017, 33, 1436–1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, L.; Dodds, R. Perceived effectiveness of Blue Flag certification as an environmental management tool along Ontario’s Great Lakes beaches. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2017, 141, 107–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Micallef, A.; Williams, A. Beach Management: Principles and Practice; Routledge: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Netemeyer, R.G. Scaling Procedures: Issues and Applications; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Pallant, J. SPSS Survival Manual: A Step by Step Guide to Data Analysis Using IBM SPSS.; Routledge: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Leatherman, S.P.; Leatherman, S.B.; Rangel-Buitrago, N. Integrated strategies for management and mitigation of beach accidents. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2024, 253, 107173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Short, A.D.; Hogan, C.L. Rip currents and beach hazards: Their impact on public safety and implications for coastal management. J. Coast. Res. 1994, 10, 197–209. [Google Scholar]

- Colford, J.M., Jr.; Wade, T.J.; Schiff, K.C.; Wright, C.C.; Griffith, J.F.; Sandhu, S.K.; Weisberg, S.B. Water quality indicators and the risk of illness at beaches with nonpoint sources of fecal contamination. Epidemiology 2007, 18, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Botero, C.M.; Pereira, C.; Anfuso, G.; Cervantes, O.; Williams, A.T.; Pranzini, E.; Silva, C.P. Recreational parameters as an assessment tool for beach quality. J. Coast. Res. 2014, 70, 556–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pranzini, E.; Pezzini, G.; Anfuso, G.; Botero, C.M. Beach safety management. In Beach Management Tools—Concepts, Methodologies and Case Studies; Botero, C.M., Pereira, C., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 397–420. [Google Scholar]

- Brander, R.W.; Williamson, A.; Dunn, N.; Hatfield, J.; Sherker, S.; Hayen, A. Evaluating the effectiveness of a science-based community beach safety intervention: The Science of the Surf (SOS) presentation. Cont. Shelf Res. 2022, 241, 104722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilks, J.; Pendergast, D. Beach safety and millennium youth: Travellers and sentinels. In Tourism and Generation Y.; Benckendorff, P., Moscardo, G., Pendergast, D., Eds.; CABI: Wallingford, UK, 2009; pp. 98–108. [Google Scholar]

- Taff, B.D.; Rice, W.L.; Lawhon, B.; Newman, P. Who started, stopped, and continued participating in outdoor recreation during the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States? Results from a national panel study. Land 2021, 10, 1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohn, J.I.; Alakshendra, A.; Kim, H.J.; Kim, K.H.; Kim, H.D. Understanding the new characteristics and development strategies of coastal tourism for post-COVID-19: A case study in Korea. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). [Title of the document if available]. Available online: https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/156293 (accessed on 27 January 2025).

- Uebelhoer, L.; Koon, W.; Harley, M.D.; Lawes, J.C.; Brander, R.W. Characteristics and beach safety knowledge of beachgoers on unpatrolled surf beaches in Australia. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2022, 22, 909–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houston, J.R. The economic value of beach nourishment in South Carolina. Shore Beach 2021, 89, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houston, J.R. The value and resilience of beach tourism during the COVID pandemic. Shore Beach 2023, 91, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- James, R.J. From beaches to beach environments: Linking the ecology, human use, and management of beaches in Australia. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2000, 43, 495–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poe, M.R.; Norman, K.C.; Levin, P.S. Cultural dimensions of socioecological systems: Key connections and guiding principles for conservation in coastal environments. Conserv. Lett. 2014, 7, 166–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stojanovic, T.; McNae, H.M.; Tett, P.; Potts, T.W.; Reis, J.; Smith, H.D.; Dillingham, I. The “social” aspect of social-ecological systems: A critique of analytical frameworks and findings from a multisite study of coastal sustainability. Ecol. Soc. 2016, 21. [Google Scholar]

- Refulio-Coronado, S.; Lacasse, K.; Dalton, T.; Humphries, A.; Basu, S.; Uchida, H.; Uchida, E. Coastal and marine socio-ecological systems: A systematic review of the literature. Front. Mar. Sci. 2021, 8, 648006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Blue Flag | NOAA Beach Safety Index | Dr. Beach | ISO 13009 |

|

Safety Infrastructure and Services: The beach must provide lifeguards or adequate safety equipment like life buoys and first-aid stations. Information on emergency contacts and response plans must be displayed clearly. There should be facilities to ensure that the beach is accessible to all users, including people with disabilities.The beach must provide well-maintained and clearly labeled access points and walkways to ensure safe passage. |

Natural hazards

|

Safety infrastructure Availability of lifeguards and their effectiveness Safety measures for preventing drownings and accidents (e.g., flags, signage) Presence of rip currents and water hazards |

Beach Safety and Security: Lifeguard services First aid facilities Safety signage Emergency response plans |

|

Environmental Education and Information: Environmental education activities must be offered and promoted to beachgoers. Information about the local ecosystem, environmental phenomena, and cultural sites should be available at the beach. Display of Blue Flag information and a code of conduct for the area is required. |

Aesthetics preservation Preservation of wildlife and natural ecosystems Efforts to maintain sand dunes, wetlands, and vegetation Sustainability and conservation efforts, including waste management |

Beach Operation and Maintenance: Regular beach cleaning schedules Infrastructure maintenance (e.g., walkways, restrooms) Managing overcrowding and user density |

|

|

Water Quality: Beaches must meet excellent water quality standards based on testing for certain pollutants (e.g., E. coli, enterococci). No industrial, wastewater, or sewage-related discharges are allowed to affect the beach area. Frequent water testing should be conducted to ensure that swimming water is clean and safe. |

Environmental Issues cleanliness and clarity of the water Absence of harmful algal blooms and pollutants Temperature of the water Color and texture of the sand Absence of debris, litter, and oil deposits Degree of erosion or beach nourishment activities Presence of rip currents and water hazards |

Environmental Management: Waste management and recycling Water quality monitoring Biodiversity protection Sustainable use of natural resources |

|

|

Environmental Management: The beach must implement effective waste management and recycling measures to minimize litter. Restroom facilities should be clean and properly maintained. The beach area should comply with zoning regulations, ensuring that the natural environment is protected (e.g., sand dunes, flora and fauna). Sustainable transportation options should be promoted to reduce the environmental footprint. |

Infrastructure for beach use Cleanliness and regular maintenance of the beach Accessibility for people with disabilities Availability of restrooms, showers, and other facilities Parking availability Nearby food and accommodation options Recreational opportunities like beach sports or nearby parks |

Services and Amenities: Accessibility for all users, including people with disabilities Clean and well-maintained facilities (e.g., toilets, showers) Availability of food and beverage services Parking and transportation options |

|

|

Aesthetic value Scenic beauty of the beachViews of natural landscapes like dunes, cliffs, and forests |

Tourist and Visitor Information: Providing up-to-date information about beach conditions Educational programs about marine conservation Information on local wildlife and habitats Monitoring visitor satisfaction Collecting and responding to feedback Regular staff training on safety and customer service |

| Dimension | Items | Citations |

| Beach Environmental Issues | Presence of litter, water pollution, visible industrial waste or sewage discharge, oil in the water, turbidity, floatable debris (e.g., wood, plastic, bottles), bad odor, temperature extremes, rip currents, strong waves and currents. | [64,65,66,69,70,71,72,80] |

| Beach Infrastructure/Amenities | Access to the beach, access for disabled individuals, showers, toilets, seating, informational signage, first aid equipment, lifeguards, webcams, warning signage, waste disposal bins, areas for separating recyclable waste. | [74,75,76] |

| Perception of Safety | Feeling of personal safety on the beach, safety of belongings, frequency of accidents (e.g., water-related, sand-related, recreational fishing, motor vehicles), presence of criminal activity, crowd control measures. | [77,78,79] |

| Social Behavior | Incidence of overcrowding, noise levels (e.g., from cars or radios), off-road driving on the beach, competition for beach space, alcohol and drug use, types of activities (e.g., sand sports, boating, fishing), presence of domestic animals. | [81,82,83,84,85] |

| Aesthetics of the Natural Environment | Scenic quality, beach width, softness of sand, presence of marine wildlife, vegetation nearby, overall cleanliness of beach areas, maintenance of promenades or natural spaces. | [64,65,66,69,70,71,72,80] |

| Dimension | Item Number | Item |

| Beach Environmental Issues | 1 | Scenery |

| 2 | Beach width | |

| 3 | Softness of sand | |

| 4 | Algae vegetation and natural debris | |

| 5 | Plenty of marine wildlife (e.g., birds) | |

| 6 | Vegetation nearby | |

| 7 | Well-kept grounds/promenades or natural environment | |

| 8 | The water was turbid | |

| 9 | There were submerged rocks | |

| 10 | There was a steeply sloping bottom | |

| 11 | There were seaweed/jellyfish on the beach | |

| 12 | There were harmful algae blooms | |

| 13 | I spotted sharks | |

| 14 | Has a good environment | |

| 15 | Is beautiful | |

| 16 | Is well preserved | |

| 17 | I encountered a lot of litter | |

| 18 | The water was very polluted | |

| 19 | There was visible industrial waste or sewage-related discharge | |

| 20 | There was oil in the water | |

| 21 | There were floatable in the water (wood, plastic articles, bottles, etc.) | |

| 22 | The water smelled bad | |

| 23 | There was a lot of marine debris (nets, fishing materials) | |

| 24 | Is polluted | |

| 25 | There were pests (biting flies, ticks, mosquitoes) | |

| Beach Infrastructure/Amenities | 26 | Developed local urbanism |

| 27 | Access to the beach | |

| 28 | Access points for disabled people | |

| 29 | Showers | |

| 30 | Toilets | |

| 31 | Toilets for disabled people | |

| 32 | Chairs | |

| 33 | Explanatory signage | |

| 34 | First aid equipment | |

| 35 | Lifeguards or lifesaving equipment | |

| 36 | Webcams | |

| 37 | Warning signage | |

| 38 | Shore protection structures | |

| 39 | Lost children’s services | |

| 40 | Information boards nearby | |

| 41 | Information on major access points, lifeguard stations, other beach facilities, or parking areas | |

| 42 | A map of the beach indicating different facilities must be displayed | |

| 43 | The area patrolled (for beaches with lifeguards) | |

| 44 | Telephones | |

| 45 | Drinking water | |

| 46 | Car and bicycle parking areas | |

| 47 | Authorized camping sites near the beach | |

| 48 | Defined zoned areas (swimming, surfing, sailing, boating, etc.) | |

| 49 | Nearby public transportation | |

| 50 | Waste disposal bins | |

| 51 | Facilities for the separation of recyclable waste materials | |

| 52 | There is healthcare available in the destination | |

| 53 | There is enforcement of transport safety at the destination | |

| 54 | The destination is pedestrian-friendly | |

| 55 | There are enforcement patrols in the destination | |

| 56 | There is traffic control in the destination | |

| Climate and Natural Factors | 57 | How was the weather there? |

| 58 | The water temperature was too cold | |

| 59 | The water temperature was too hot | |

| 60 | The waves were too strong | |

| 61 | The waves were really big | |

| 62 | There were too many waves | |

| 63 | There were strong currents | |

| 64 | There were rip currents | |

| 65 | The air temperature was extreme (too hot or too cold) | |

| 66 | The wind was too strong | |

| Social Behavior | 67 | Presence of domestic animals |

| 68 | There is frequent overcrowding | |

| 69 | There is a lot of noise (e.g., cars, highways, trains, radios) | |

| 70 | People often drive off-road (in the sand) | |

| 71 | There is competition for free use of the beach | |

| 72 | There is a high level of crime (e.g., assaults) | |

| 73 | Pickpocketing is common | |

| 74 | There have been human casualties (e.g., drowning) | |

| 75 | There have been water-related accidents (e.g., surfing, diving, snorkeling) | |

| 76 | There have been sand-related sports/activities accidents | |

| 77 | Recreational fishing-related accidents are frequent | |

| 78 | There have been accidents involving boats and jet skis | |

| 79 | Motor-vehicle-related accidents occur on the beach | |

| 80 | Slips, trips, and falls are common | |

| 81 | There have been accidents related to the use of drugs and alcohol on the beach | |

| Perception of Safety | 82 | Is the beach safe |

| 83 | Is dangerous | |

| 84 | The destination as a whole is safe | |

| 85 | I have been safe in the destination in the past | |

| 86 | The destination is secure | |

| 87 | I feel safe touring the destination in the daytime | |

| 88 | I feel safe walking the destination’s streets after dark | |

| 89 | I feel safe driving or using public transport at the destination | |

| 90 | I feel safe driving at the destination | |

| 91 | I feel safe staying in hotels at the destination | |

| 92 | I believe I could be a victim of crime in the destination | |

| 93 | The destination is a violent place | |

| 94 | It could be terrorist attacks on the destination |

| Dimension | Item Description |

| Beach Environmental Issues | Scenery |

| Is polluted | |

| Has a good environment | |

| Is beautiful | |

| Is well preserved | |

| The beach is well preserved | |

| The beach has a good environment | |

| Beach Infrastructure/Amenities | Developed local urbanism |

| Explanatory signage | |

| Car and bicycle parking areas | |

| Defined zoned areas (swimming, surfing, sailing, boating, etc.) | |

| Information on major access points, lifeguard stations, other facilities |

| Dimension | Item Number | Item Description | Factor Loading for each dimension |

| Beach Environmental Issues α=.922 |

1 | The water smelled bad | 0.804 |

| 2 | The water was turbid | 0.781 | |

| 3 | There was oil in the water | 0.772 | |

| 4 | There was visible industrial waste or sewage-related discharge | 0.765 | |

| 5 | Floatables were in the water (wood, plastic articles, bottles) | 0.758 | |

| 6 | There was a lot of marine debris (nets, fishing materials) | 0.753 | |

| 7 | The waves were too strong | 0.747 | |

| 8 | There was a steeply sloping bottom | 0.730 | |

| 9 | There were too many waves | 0.727 | |

| 10 | There were harmful algae blooms | 0.727 | |

| 11 | The water was very polluted | 0.715 | |

| 12 | The wind was too strong | 0.710 | |

| 13 | There were rip currents | 0.710 | |

| 14 | There were strong currents | 0.689 | |

| 15 | The water temperature was too cold | 0.684 | |

| 16 | The waves were really big | 0.663 | |

| 17 | There were submerged rocks | 0.643 | |

| 18 | I spotted sharks | 0.635 | |

| 19 | The water temperature was too hot | 0.613 | |

| 20 | I encountered a lot of litter | 0.600 | |

| 21 | There were seaweed/jellyfish on the beach | 0.582 | |

| 22 | There were pests (biting flies, ticks, mosquitoes) | 0.565 | |

| 23 | The air temperature was extreme (too hot or too cold) | 0.562 | |

| 24 | Presence of domestic animals | 0.552 | |

| Beach Infrastructure/Amenities α=.900 |

25 | First aid equipment | 0.764 |

| 26 | Lost children’s services | 0.696 | |

| 27 | Drinking water | 0.694 | |

| 28 | Toilets for disabled people | 0.688 | |

| 29 | A map of the beach indicating different facilities | 0.672 | |

| 30 | Telephones | 0.662 | |

| 31 | Nearby public transportation | 0.649 | |

| 32 | Lifeguards or lifesaving equipment | 0.648 | |

| 33 | Toilets | 0.647 | |

| 34 | Authorized camping sites at/near the beach | 0.644 | |

| 35 | Webcams | 0.636 | |

| 36 | Defined zoned areas (swimming, surfing, sailing, boating, etc.) | 0.636 | |

| 37 | The area patrolled (for beaches with lifeguards) | 0.624 | |

| 38 | Information boards closely displayed | 0.622 | |

| 39 | Chairs | 0.617 | |

| 40 | Facilities for the separation of recyclable waste materials | 0.576 | |

| 41 | Showers | 0.564 | |

| 42 | Shore protection structures (revetments, seawalls, groins, etc.) | 0.529 | |

| 43 | Information on major access points, lifeguard stations, etc. | 0.509 | |

| 44 | Access points for disabled people | 0.500 | |

| 45 | Warning signage | 0.427 | |

| 46 | There is available healthcare at the destination | 0.424 | |

| Climate and Natural Factors α=.871 |

47 | How was the weather there? | 0.710 |

| 48 | The water temperature was too cold | 0.684 | |

| 49 | The water temperature was too hot | 0.613 | |

| 50 | The waves were too strong | 0.576 | |

| 51 | The waves were really big | 0.564 | |

| 52 | There were too many waves | 0.529 | |

| 53 | There were strong currents | 0.509 | |

| 54 | There were rip currents | 0.500 | |

| 55 | The air temperature was extreme (too hot or too cold) | 0.427 | |

| 56 | The wind was too strong | 0.421 | |

| Social Behavior α=.951 |

57 | There have been accidents involving boats and jet skis | 0.868 |

| 58 | There have been sand-related sports/activities accidents | 0.848 | |

| 59 | There have been accidents related to the use of drugs/alcohol | 0.819 | |

| 60 | There have been water-related accidents | 0.816 | |

| 61 | Recreational fishing-related accidents are frequent | 0.789 | |

| 62 | Motor-vehicle-related accidents occur on the beach | 0.777 | |

| 63 | Slips, trips, and falls are common | 0.750 | |

| 64 | Pickpocketing is common | 0.734 | |

| 65 | There is a high level of crime (e.g., assaults) | 0.719 | |

| 66 | There have been human casualties (e.g., drowning) | 0.693 | |

| 67 | People often drive off-road (in the sand) | 0.662 | |

| 68 | There is competition for free use of the beach | 0.651 | |

| 69 | There is frequent overcrowding | 0.648 | |

| 70 | I believe I could be a victim of crime in the destination | 0.643 | |

| 71 | It could be terrorist attacks on the destination | 0.588 | |

| 72 | There is a lot of noise (e.g., cars, highways, trains, radios) | 0.585 | |

| 73 | The destination is a violent place | 0.556 | |

| Perception of Safety α=.861 |

74 | The destination is safe | 0.839 |

| 75 | The destination is secure | 0.804 | |

| 76 | I feel safe touring the destination in the daytime | 0.759 | |

| 77 | I feel safe walking the destination’s streets after dark | 0.731 | |

| 78 | I feel safe driving or using public transport in the destination | 0.699 | |

| 79 | I feel safe staying in hotels in the destination | 0.687 | |

| 80 | I feel safe driving in the destination | 0.668 | |

| 81 | I have been safe in the destination in the past | 0.637 | |

| 82 | The beach is safe | 0.567 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).