1. Introduction

Colon cancer is one of the important oncological problems in developed countries and ranks second among all cancer types in terms of incidence worldwide [

1]. According to the data of the World Health Organization (WHO) in 2020, more than 1.9 million people worldwide were diagnosed with colon cancer and approximately 1 million people died due to colon cancer [

1]. Colon cancer, which represents one out of every 10 cancer cases and deaths, has higher incidence and mortality rates in men than in women [

1]. Combination therapy of colon cancers with polyphenols and chemotherapy has been one of the strategies used in cancer treatment in recent years [

2,

3]. Increasing the effectiveness of certain cancer drugs reduces the cost of treatment by shortening the length of hospital stay of patients and provides social impact. Therefore, it is considered necessary to develop this approach. SsnB has been classified as a polyphenol isolated from the plant roots of

Sparganium stoloniferum [

4]. Its structure is like classes of polyphenolic compounds such as isocoumarins and xanthones [

5]. The structure is shown below in

Scheme 1 [

6] (data are computed by PubChem, https: //pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov, accessed on 28 January 2025).

Scheme 1.

Structure of Sparstolonin [

6].

Scheme 1.

Structure of Sparstolonin [

6].

In this study, the efficacy of SsnB, a polyphenol that has not yet been studied as a TLR 2 and TLR 4 antagonist in colon cancer, was investigated. Toll-Like receptors recognize pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) and regulate inflammatory responses as important components of the innate immune system [

7]. However, chronic activation of TLRs leads to the formation and progression of the tumor microenvironment in many types of cancer, especially colon [

8]. It has been reported that overexpression of TLR 4 promotes tumor growth and metastasis in colon cancer due to inflammation [

9]. In this context, the inhibition of TLR signaling pathways is considered as a promising approach in the treatment of colon cancer. Studies have reported that TLR 2 and 4 are expressed in human HCT-116 colon cancer cell line [

10,

11,

12]. The activation of TLR 2 and 4 signal transduction pathways in the human colon cancer cell line induces ERK phosphorylation, inducing cell proliferation via NF-kB and suppressing apoptosis [

13]. SsnB has been shown to reduce NF-kB expression by suppressing TLR 2 and TLR 4 in gastric cancer cells and adipocytes [

14,

15,

16]. Based on these findings, we hypothesized that SsnB could be antiproliferative in colon cancer cells through TLR 2 and TLR 4 signaling pathways. To the best of our knowledge, the antiproliferative effect of SsnB in colon cancer was not investigated through TLR 2 and TLR 4 signaling pathways.

The effects of sphingolipid metabolism on cancer development and progression have gained importance in recent years [

17]. In a recently published study by our group, we discovered that administering 25 µM SsnB to estrogen receptor-positive breast and ovarian cancer cells dramatically reduced their S1P levels and caused a substantial buildup in intracellular concentrations of ceramides [

18]. The formation of physiologically active sphingolipids is now understood to have important roles in the genesis and progression of cancer. Ceramide plays a crucial role in the metabolism of sphingolipids and suppresses tumor growth in a variety of cancerous cells by triggering apoptosis and anti-proliferative reactions [

19]. According to certain studies, there may also be a connection between TLR signaling and the metabolism of sphingolipids, particularly the synthesis of ceramide, which is involved in cancer treatment [

20]. Therefore, the effect of SsnB on ceramide, S1P and C1P levels were also determined in human colon cancer cells.

3. Discussion

The results of this study show that treating HCT-116 cells with 10 nM PMA for 12 h significantly increased cell proliferation. There was no significant change in cell proliferation in BJ fibroblast cells that received PMA at the same dose and time. PMA is a protein kinase C (PKC) activator and regulates cell proliferation and biological processes such as apoptosis by PKC activation [

21,

22,

23]. Incubation of HCT-116 cells with 25 μM SsnB for 12 hours significantly reduced cell proliferation in the presence and absence of PMA. No statistically significant change in cell proliferation occurred in the presence and absence of PMA in BJ fibroblast cells treated with SsnB at the same dose and period. Studies have shown that the administration of SsnB to cancer and endothelial cells reduces cell proliferation [

24,

25,

26,

27,

28] SsnB has been reported to inhibit cancer-related processes such as cell migration, invasion, and angiogenesis by stopping the cell cycle at G1 or G2/M checkpoints [

26]. Administration of SsnB at concentrations between 10-100 μM has been found to show potent antiproliferative effects in various cell types, including neuroblastoma [

4], prostate cancer [

24,

28] and pancreatic cancer [

27] models. Within our literature review, this study is the first to examine PMA-dependent proliferation of SsnB in HCT-116 human colon cancer and healthy BJ fibroblast cells.

A significant increase in the intracellular levels of C18, C20, C22 and C24 ceramides occurred in HCT-116 cells treated for 12 h with a concentration of 25 μM of SsnB compared to all experimental groups. This is the first study to evaluate the impact of SsnB on endogenous sphingolipid levels in human colon cancer cells. Most of the research on SsnB concentrates on its anti-proliferative, anti-inflammatory, and anti-angiogenic properties, which are mainly achieved via inhibiting NF-κB and STAT1 signaling [

29] and modifying Toll-like receptor (TLR) pathways [

15]. When TLR4 or TLR1/TLR2 or TLR2/TLR6 ligands were used to stimulate mouse macrophages, SsnB significantly reduced the production of inflammatory cytokines [

15]. Evaluated research has not provided sufficient evidence on the effects of SsnB on lipid metabolism or ceramide levels. Ceramide production in cancer cells and TLR signaling have a complicated interaction. According to certain studies, there may be a connection between TLR signaling and the metabolism of sphingolipids, particularly the synthesis of ceramide, which is involved in cancer treatment [

30]. There aren't many solid examples of TLR antagonists directly boosting ceramide synthesis, though. Increased TLR expression has been linked to oncogenesis and the progression of cancer in cancer cell lines [

31]. TLRs regulate the inflammatory responses in cancer cells. However, there is ongoing debate over the connection between TLR and cancer. TLRs have been demonstrated to both accelerate and appear to slow the progression of cancer [

32,

33,

34].

Toll-like receptors have emerged as critical players in cancer biology, making them appeal to therapeutic targets due to their elevated expression in various tumors, including human colon cancer [

8]. TLR2, TLR3, and TLR4 are overexpressed in most colon cancer cells [

35]. However, in the context of colon cancer, aberrant TLR signaling has been linked to both tumor-promoting and tumor-suppressing effects, underscoring the complexity of targeting these pathways for therapeutic purposes [

36]. For more than thirty years, bladder cancer has been treated with Bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG), the TLR2/TLR4 agonist that is the most effective TLR ligand in cancer therapy [

37]. Its effectiveness highlights the therapeutic potential of TLR pathway modulation in oncology. During tumor development, TLR4 activation promotes the production of proinflammatory chemokines and immunosuppressive cytokines in an unregulated manner. This environment facilitates immune evasion, angiogenesis, and metastasis, as observed in human colon cancer [

38]. These findings highlight the potential of TLR4 antagonists as a novel therapeutic strategy. Our findings suggest that manipulating TLR signaling holds significant therapeutic promise, particularly through the modulation of ceramide synthesis. Ceramide, a bioactive lipid, plays a crucial role in inducing cancer cell death and overcoming drug resistance [

39]. In the context of TLR signaling, the small molecule SsnB has been hypothesized to influence ceramide synthesis, thereby enhancing ceramide-driven apoptosis in colon cancer cells. This mechanism involves TLR inhibition to create a pro-apoptotic environment characterized by ceramide accumulation, which, coupled with attenuated survival signaling, selectively induces apoptosis in cancer cells. Such dual modulation underscores the potential of SsnB as a targeted therapeutic agent in colon cancer characterized by dysregulated TLR pathways and survival mechanisms.

We discovered that administering 25 µM SsnB to colon cancer cells for 12 hours dramatically reduced their S1P and C1P levels. As far as we are aware, our study is the first to show that colon cancer cells treated with SsnB had lower S1P levels. Examples of functional sphingolipid metabolites that are vital to the biological pathways that are fundamental to the pathophysiology of cancer are C1P and S1P [

40]. Both S1P and C1P sets off mechanisms that transform it into a lipid that promotes cancer [

41].

We observed that MyD88, p-ERK, p-NF-kB, TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 were significantly suppressed in cancer cells treated with SsnB compared to the control groups. These findings align with previous studies indicating that SsnB inhibits key inflammatory and survival pathways in cancer cells [

18]. The MyD88/NF-kB signaling axis is a central pathway in regulating inflammatory responses and tumor progression in colorectal cancer [

42]. Activation of MyD88, an adaptor protein, triggers a signaling cascade involving p-ERK and NF-kB, leading to the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 [

43]. These cytokines not only promote a pro-tumorigenic microenvironment but also enhance cancer cell proliferation, survival, and metastasis [

43]. The suppression of MyD88 and downstream mediators like p-ERK and p-NF-kB by SsnB suggests a potent anti-inflammatory effect, which could disrupt the tumor-supportive inflammatory milieu. Notably, NF-kB is often constitutively activated in various cancers, contributing to the expression of genes involved in cell survival, invasion, and chemoresistance [

44]. By inhibiting NF-kB activation, SsnB may diminish the expression of its target cytokines, including TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6, which are critical for maintaining cancer cell viability and immune evasion.

Our results also highlight the therapeutic potential of SsnB in targeting cytokine-mediated pathways. TNF-α and IL-1β, key pro-inflammatory cytokines, are known to enhance angiogenesis, tumor invasion, and resistance to apoptosis. IL-6 further supports tumor growth through the activation of STAT3, a transcription factor implicated in cancer cell proliferation and metastasis in colorectal cancer cells [

45]. The downregulation of these cytokines by SsnB may mitigate their tumor-promoting effects and enhance cancer cell susceptibility to apoptosis.

In summary, SsnB exerts its anti-cancer effects by downregulating MyD88, p-ERK, and p-NFκB signaling, along with suppressing the pro-inflammatory cytokines TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6. This comprehensive inhibition disrupts the tumor-supportive microenvironment and enhances apoptosis, offering a promising therapeutic approach for cancer treatment. This study's limitations include its reliance on HCT-116 cancer cells and BJ fibroblasts, which do not fully represent cancer heterogeneity or normal cell behavior. The in vitro model cannot replicate complex in vivo tumor dynamics, including immune and stromal interactions. PMA, used to induce inflammation, may not mimic natural tumor promotion. The limited dose range and treatment duration for SsnB leave long-term efficacy and safety unexplored.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Cell Culture

Human colon cancer (HCT-116) and healthy human fibroblast cell lines (BJ) were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC; Manassas, VA, USA). Cells were cultured in 25 cm2 culture flasks using Dulbecco's Modified Eagle's Medium (DMEM, Sigma, Cat. #D5648, St. Louis, MO, USA) with high glucose. The medium was supplemented with, 3.7 g/L sodium bicarbonate (Sigma-Adrich), 10% (v/v) heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Gibco, Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY, USA), 100 U/mL penicillin (Gibco), 100 μg/mL streptomycin (Gibco), 1% sodium pyruvate (Gibco) and 5 μg/100 mL amphotericin B (Gibco). The prepared medium was sterilized by vacuum filtering through a 0.22 μm bottle-top filter and stored at 4°C. The cells were incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2 and 95% humidified air. When cells reach 80% density, they were lifted from the flask surface via trypsin-EDTA (0.05% Trypsin/0.02% EDTA; Gibco) and suspended and passed to new flasks.

4.2. Application of Sparstolonin B and Phorbol 12-Myristate 13-Acetate

Five mg SsnB (MW= 268.22 g/mol; Merck Millipore, Cork, Ireland, #SML1767) was dissolved in 1.854 ml of DMSO to yield a stock concentration of 10 mM. The prepared main stock was diluted with DMSO to create an intermediate stock of 1 mM. One mM SsnB was diluted with cell culture medium to concentrations of 3.125, 6.25, 12.5, 25 and 50 μM. MTT [3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide] cell viability analysis was used to determine the dose and duration of application.

Five mg PMA (MW= 616.83 g/mol; LC Laboratories, Canada, #P-1680) was dissolved in 1 ml DMSO to prepare a stock concentration of 8.1 mM. The prepared main stock was diluted with DMSO to create an intermediate stock of 1 mM. One mM of PMA intermediate stock was diluted with cell culture medium to concentrations of 1, 5, and 10 nM. Dose and duration of administration were determined by MTT analysis.

4.3. Cell Viability Analysis

MTT (Gold Biotechnology Inc., St. Louis, MO, USA) was dissolved at a concentration of 5 mg/mL in PBS and sterilized by passing through a filter with a pore diameter of 0.22 μm. Before MTT analysis, HCT-116 and BJ fibroblast were plated in 96 well plates and waited for one night to adhere. After adhesion, 200 μl of cell culture medium containing either DMSO (1 μL/mL), PMA (1-10 nM) and/or SsnB (3.125-50 μM) were added to the wells. After 12-18 hours of incubation, the media were withdrawn, fresh medium containing MTT was added (90 μL medium + 10 μL MTT with a total volume of 100 μL) and the 96 well plate was incubated for 2 hours. Purple formazan crystals formed at the bottom of the wells were dissolved with 100 μL of DMSO and absorbance was measured at 570 and 690 nm via a spectrophotometric plate reader (MicroQuant, Bio-Tek Instruments Inc., Charlotte, VT, USA). The percentage of cell viability was calculated so that the absorbance in the control group represented 100% cell viability [Cell viability (%) = (Abs sample / Abs control) x 100]. According to the results of the MTT test, five different experimental groups were formed for each cell line.

4.4. Immunofluorescence Staining

Approximately 100,000 cells/well were plated in an 8 well chamber slide (Merck Millipore, Cork, Ireland) and cells were allowed to adhere overnight. Following 12 hour incubation of treatment groups, cells were washed 2 times with cold PBS and were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) solution for 10 minutes. After two washes in PBS, cells were permeabilized in 0.2% Triton-X-100 (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) for 10 min and washed five times with PBS. Afterwards, 5% normal goat serum (NGS; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA) was used for blocking for 30 minutes, 200 μl of primary antibody was applied, and the chamber slide was kept at 4°C overnight. Primary antibodies were diluted with ab-diluent (PBS containing 5% NGS and 0.2% Tween 20). The primary antibodies used were PCNA rabbit polyclonal ab (1:100 dilution, #bs-0754R, Bioss Antibodies Inc., Woburn, MA, USA), phospho-ERK1/2 (Thr202/Tyr204) rabbit polyclonal ab (1:200 dilution, #AF1015, Affinity Biosciences, Changzhou, Jiangsu, China), phospho-NF-kB rabbit polyclonal ab (1:200 dilution, #AF2006, Affinity Biosciences, Changzhou, Jiangsu, China), MyD88 rabbit polyclonal ab (1:100 dilution, # BT-AP05682, BT Lab, Shanghai, China) and cleaved-caspase 3 rabbit polyclonal ab (1:100 dilution, #9664S, Cell Signaling Tech., Massachusetts, USA). After the primary antibody incubation, the incubation medium was withdrawn, 3 washes were performed with PBS, and 200 μl of fluorophore-labeled secondary antibody (Alexa Fluor, 1:1000 dilution, ab150077 Abcam, Cambridge, UK) was added. Cells were incubated at room temperature for 45 minutes and after incubation, cells were washed with PBS 2 times and a drop of DAPI was applied (Fluoroshield with DAPI #F6057, Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) to stain cell nuclei. The slides were covered with coverslips without air bubbles. Imaging was performed with a fluorescence microscope (Olympus BX61 fully automated, Tokyo, Japan) using DP controller software. Alexa Fluor was imaged at 488 nm excitation and 505-525 nm emission, while DAPI was imaged at 350 nm excitation and 440-460 nm emission. Fluorescence was measured using NIH ImageJ 1.53e software and calculated with the formula CTCF (corrected total cell fluorescence) = ID (integrated density)- [ASC (area of selected cell) x BMF (background mean fluorescence)].

4.5. Determination of TLR 2 and TLR 4 mRNA Expression

OMIM (Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man) database was used as a source for all mRNA sequences. OligoYap 9.0 software (SNP Biotechnology R&D Ltd., Ankara, Turkey) was used to design primers and probes.

Supplementary Table S1 lists the primers and probes that were used. The One-run RT PCR kit (SNP Biotechnology R&D Ltd., Ankara, Turkey) was used to conduct real-time PCR analysis. Several forward and reverse primer concentrations were used in the optimization process to determine the lowest primer concentration that would produce the highest ΔRn (the difference between the sample's minimum and maximum fluorescence). Using various probe concentrations at the ideal primer concentrations allowed for the determination of the ideal probe concentration. The concentration of the probe that yielded the lowest cycle threshold (Ct) value was found to be the optimal one.

Total RNA extraction was performed using a commercial kit and the manufacturer's instructions (SNP Biotechnology R&D Ltd., Ankara, Turkey). The extracted RNA was dissolved in 70 μL of TE buffer [10 mM Tris-HCl, 0.1 mM EDTA (pH 7.5)]. 10 μL of the dissolved RNA was diluted with 490 μL of distilled water (1:50 dilution). The diluted RNA sample was tested for absorbance at 260 and 280 nm using spectrophotometry. The purity of the RNA samples was assessed using the test results at 260 and 280 nm. Samples with a 260 nm/280 nm ratio of less than two were suitable for analysis. The absorbance at 260 nm was used to calculate the samples' RNA content. At 260 nm, 40 μg/mL of RNA was equivalent to an absorbance unit of 1. Sample RNA (100 ng/μL), one-run mix, primer-1 (100 pmol), primer-2 (100 pmol), and probe (100 pmol) were all included in the sample preparation for each assay.

RT-PCR analysis was performed using the Mx3000p Multiplex Quantitative PCR system (Stratagene, CA, USA). The cycle conditions were as follows: step 1, 10 minutes at 42 °C (1 cycle); step 2, 5 seconds at 90 °C and step 3, 45 seconds at 60 °C (40 cycles). Using MxPro QPCR Software for the Mx3000P system, the log-linear phase of amplification was monitored to obtain Ct values for each RNA sample. All reactions were conducted in three repetitions, and the mRNA levels of each gene normalized to beta actin were expressed as a 2-(ΔΔct) fold change.

4.6. ELISA Measurements

PCNA was determined with a non-competitive sandwich ELISA kit (cat. #ELK5141 Biotechnology; Denver, CO, USA). HCT-116 and BJ fibroblasts (107 cell/mL) were subjected to ultrasonication, and supernatants were collected by centrifugation at 4°C for 10 min at 1500 × g. The amount of PCNA was determined in accordance with the kit instructions and the samples were measured in a spectrophotometric plate reader at 450 nm. PCNA concentration in the samples was calculated using a standard curve and reported as ng/cell count.

Protein levels of TLR2 (cat # E0358Hu. BT Lab, Shanghai, China), TLR4 (cat # E0346Hu. BT Lab, Shanghai, China), MyD88 (cat. #E1870Hu BT Lab, Shanghai, China), TNF-α (cat. #E0082Hu. BT Lab, Shanghai, China), IL-1β (cat # E0143Hu BT Lab, Shanghai, China) and IL-6 (cat. #E0090Hu BT Lab, Shanghai, China) were assessed using sandwich ELISA kits in cell lysates. Cell pellets from the experimental groups were suspended in 250 μL of cold PBS for the cell samples. Sonication (Bandelin Sonopuls HD 2070, Bandelin Elec., Germany) broke up the cells totally. After centrifuging the lysates at 1500 × g for 10 minutes at 2–8°C, the supernatants were gathered. Spectrophotometric absorbance measurements were made at 450 nm using the measurement procedures outlined in the kit manuals. To analyze sample concentrations on nonlinear standard curves, GraphPad Prism software was used for curve fitting and interpolation. The results were expressed in milligrams of cell protein.

4.7. TUNEL Analysis

Cell death was detected using the One-Step TUNEL Assay Kit (Elabscience; Houston, Texas, USA, E-CK-A320). This technique relies on the use of fluorescent markers to identify double-stranded DNA breaks that take place in apoptotic cells. The test protocol was followed in the preparation of each sample and reagent. On chamber slides (Merck Millipore, Cork, Ireland), 100,000 cells were transferred per well. After treatment and incubation according to experimental groups, the cells were fixed using fixative buffer (paraformaldehyde) for 20 minutes at room temperature. The slides were washed three times with PBS for five minutes each after fixation. DNase I (200 U/mL) was added to create positive controls, which were then incubated for 25 minutes at 37°C. Negative controls did not receive TdT Enzyme treatment; instead, they were incubated with an identical volume of buffer. All other groups received 100 μL of TdT, which was then incubated for 25 minutes at 37°C. Following incubation, each slide received 50 μL of labeling working solution, which was then incubated for 60 minutes at 37°C in a humidified environment. The slides then went through three 5-minute PBS washes. Upon the removal of the chambers and a tissue-cleaning procedure, a drop of DAPI (Sigma-Aldrich; St. Louis, MO, USA) was applied to each slide. A fluorescence microscope (Olympus BX61 fully automated, Tokyo, Japan) was used to view the fluorescence intensity after a clean, air-bubble-free coverslip was put in place.

4.8. Determination of Apoptotic Cells by Flow Cytometry

The apoptotic effects of PMA and SsnB on HCT-116 and BJ cells were assessed using an Annexin-V/PI apoptosis kit (Elabscience: #E-CK-A211, Texas, USA). Cells were treated as previously described, washed with PBS, and detached using Trypsin-EDTA. After suspension in PBS, 1×10⁶ cells were transferred to flow cytometry tubes, washed twice, and centrifuged at 125×g for 5 minutes. The supernatant was discarded, and cells were resuspended in 500 µL Annexin-V binding buffer. Annexin-V-FITC (5 µL) and PI (5 µL) were added, and the mixture was incubated for 20 minutes at room temperature. Fluorescently labeled cells were analyzed immediately on the FACS Canto II flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA) with appropriate settings. Data were processed using BD FACS Diva 6.1.3 software, and results were expressed as percentages of total cell staining.

4.9. Sphingolipidomic Analysis

Samples were prepared for SM and CER analysis as previously described [

46]. Cell lysates (100 mg/ml protein) were mixed with 2 μL of a 5000 ng/mL internal stock solution, and then 375 μL of chloroform:methanol (1:2, v/v) was added. After 30 seconds of sonication and 5 minutes of vortexing with 100 μL of distilled water, the mixture was allowed to rest at room temperature for 30 minutes. The mixture was centrifuged at 2000 × g for five minutes after incubation, and the supernatant was gathered. After adding 125 μL of distilled water and 125 μL of chloroform, the supernatant was vortexed and allowed to sit at room temperature for an additional half hour. After incubation, a nitrogen stream (VLM, Bielefeld, Germany) was used to dry 500 μL of the top organic layer in a new glass tube. The dried residue was dissolved in 100 μL of methanol:formic acid (99.9:0.1) and then placed into insert vials for LC-MS/MS analysis.

Ceramide and sphingomyelin levels were measured using an LC/MSMS instrument (LCMS-8040, Shimadzu Corporation, Japan) paired with an ultra-fast liquid chromatography system (LC-20 AD UFLC XR) [

46]. Standards were obtained from Avanti Polar Lipids, with a labeled internal standard (C16 CER d18:1/16:0) from Cambridge Isotope Laboratories. Sphingolipid standards were prepared by sonication at 40°C in methanol. Chromatographic separation was achieved on an XTerra C18 HPLC column (2.1 mm × 50 mm, Waters, MA, USA) at 60°C with a 10 μL injection volume and a 0.450 mL/min flow rate. Gradient elution lasted 30 minutes with mobile phases of water/acetonitrile/2-propanol and acetonitrile/2-propanol. Positive electrospray ionization (ESI) and multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) were used for detection. Calibration ranges were linear between 39–625 ng/mL.

4.10. Protein Measurements

The protein concentration in all samples were determined at 595 nm via Coomassie reagent (Thermo Scientific; Rockford, USA). Bovine Serum Albumin was used as standard in this measurement.

4.11. Statistical Analyses

SigmaPlot 15 or GraphPad Prism 8.4.3 were used for statistical analyses. Normality tests determined data distribution. Non-parametric tests were used for non-normal data. Experimental groups were compared using Kruskal-Wallis or One-Way ANOVA, followed by post-hoc tests to identify specific group differences when significant differences were found. Results are detailed in figure legends.

Figure 1.

Cell viability and proliferation in HCT-116 and BJ cells. (A) Values are mean ± SD and n=8. Statistical analysis was by 2-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons. #, p<0.01 vs. control, DMSO, 3.125 and 6.25 μM groups within the same incubation period. *, p<0.001 vs. control, DMSO, 3.125, 6.25 and 12.5 μM groups within the same incubation period. $, p<0.001 vs. all other groups within the same incubation period. ¶¶¶, p<0.01 18 h vs. 12 h and 16 h. ¶¶, p<0.01 18 h vs.16 h. ¶, p<0.01 18 h vs.12 h. (B) Values are mean ± SD and n=8. Statistical analysis was by 2-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons. *, p<0.05 vs. control within the same incubation period. #, p<0.01 vs. control and DMSO within the same incubation period. ¶, p<0.01 12 h vs.16 h and 18 h. ¶¶, p<0.01 12 h vs.16 h. (C) HCT-116 cells were treated with DMSO (1 μL/mL), SsnB (25 μM), and/or PMA (10 nM) for 12 h. Values are mean ± SD and n=8. Statistical analysis was by one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons. *, p<0.05 vs. all other groups. #, p<0.05 vs. DMSO and PMA. (D) Values are mean ± SD and n=8. Statistical analysis was by 2-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons. *p< 0.05 vs. control DMSO and 6.25 μM groups within the same incubation period. #, p<0.05 vs. control, DMSO, 3.125, 6.25 and 12.5 μM groups within the same incubation period. $, p<0.05 vs. all other groups within the same incubation period. (E) Values are mean ± SD and n=8. Statistical analysis was by 2-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons. *, p< 0.05 vs. control, 1 and 5 nM groups within the same incubation period. #, p<0.05 vs. 1 nM group within the same incubation period. (F) BJ cells were treated with DMSO (1 μL/mL), SsnB (25 μM), and/or PMA (10 nM) for 12 h. Values are mean ± SD and n=8. (G) HCT-116 and BJ cells were treated with DMSO (1 μL/mL), SsnB (25 μM), and/or PMA (10 nM) for 12 h. Images were acquired via a 40× objective. (H) Proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) was immunofluorescent stained in HCT-116 and BJ cells treated with DMSO (1μ/ml), SsnB (25 μM), and/or PMA (10 nM) for 12 hours (40× objective). (I) PCNA fluorescence staining in HCT-116 cells was quantified using ImageJ software. Values are mean ± SD and n=8. Statistical analysis was by one way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons. *, p < 0.001, vs. all other groups. #, p < 0.01, vs. control, DMSO and PMA groups. (J) Levels of PCNA protein in HCT-116 cells. Values are mean ± SD and n=6. Statistical analysis was by one way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons. *, p < 0.01, vs. all other groups. #, p < 0.01, vs. SsnB. (K) PCNA fluorescence staining in BJ cells is quantified using ImageJ software. Values are mean ± SD and n=8. (L) Levels of PCNA protein in BJ cells. Values are mean ± SD and n=6.

Figure 1.

Cell viability and proliferation in HCT-116 and BJ cells. (A) Values are mean ± SD and n=8. Statistical analysis was by 2-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons. #, p<0.01 vs. control, DMSO, 3.125 and 6.25 μM groups within the same incubation period. *, p<0.001 vs. control, DMSO, 3.125, 6.25 and 12.5 μM groups within the same incubation period. $, p<0.001 vs. all other groups within the same incubation period. ¶¶¶, p<0.01 18 h vs. 12 h and 16 h. ¶¶, p<0.01 18 h vs.16 h. ¶, p<0.01 18 h vs.12 h. (B) Values are mean ± SD and n=8. Statistical analysis was by 2-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons. *, p<0.05 vs. control within the same incubation period. #, p<0.01 vs. control and DMSO within the same incubation period. ¶, p<0.01 12 h vs.16 h and 18 h. ¶¶, p<0.01 12 h vs.16 h. (C) HCT-116 cells were treated with DMSO (1 μL/mL), SsnB (25 μM), and/or PMA (10 nM) for 12 h. Values are mean ± SD and n=8. Statistical analysis was by one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons. *, p<0.05 vs. all other groups. #, p<0.05 vs. DMSO and PMA. (D) Values are mean ± SD and n=8. Statistical analysis was by 2-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons. *p< 0.05 vs. control DMSO and 6.25 μM groups within the same incubation period. #, p<0.05 vs. control, DMSO, 3.125, 6.25 and 12.5 μM groups within the same incubation period. $, p<0.05 vs. all other groups within the same incubation period. (E) Values are mean ± SD and n=8. Statistical analysis was by 2-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons. *, p< 0.05 vs. control, 1 and 5 nM groups within the same incubation period. #, p<0.05 vs. 1 nM group within the same incubation period. (F) BJ cells were treated with DMSO (1 μL/mL), SsnB (25 μM), and/or PMA (10 nM) for 12 h. Values are mean ± SD and n=8. (G) HCT-116 and BJ cells were treated with DMSO (1 μL/mL), SsnB (25 μM), and/or PMA (10 nM) for 12 h. Images were acquired via a 40× objective. (H) Proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) was immunofluorescent stained in HCT-116 and BJ cells treated with DMSO (1μ/ml), SsnB (25 μM), and/or PMA (10 nM) for 12 hours (40× objective). (I) PCNA fluorescence staining in HCT-116 cells was quantified using ImageJ software. Values are mean ± SD and n=8. Statistical analysis was by one way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons. *, p < 0.001, vs. all other groups. #, p < 0.01, vs. control, DMSO and PMA groups. (J) Levels of PCNA protein in HCT-116 cells. Values are mean ± SD and n=6. Statistical analysis was by one way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons. *, p < 0.01, vs. all other groups. #, p < 0.01, vs. SsnB. (K) PCNA fluorescence staining in BJ cells is quantified using ImageJ software. Values are mean ± SD and n=8. (L) Levels of PCNA protein in BJ cells. Values are mean ± SD and n=6.

Figure 2.

Evaluation of the TLR2-TLR4 signaling pathway in HCT-116 cells. Cells were treated with DMSO (1 μL/mL), SsnB (25 μM), and/or PMA (10 nM) for 12 h in all experiments. (A) PCR analysis of TLR2. Data shows mean ± SD and n=4 different measurements. Statistical analysis was performed by Kruskal-Wallis test and the difference between the groups was determined by Tukey's test. *, p<0.05 vs. SsnB. (B) PCR analysis of TLR4. Data shows mean ± SD and n=4 different measurements. Statistical analysis was performed by Kruskal-Wallis test and the difference between the groups was determined by Tukey's test. *, p<0.01 vs. SsnB. (C) Protein levels of Toll-like Receptor 2 (TLR2). Data shows mean ± SD and n=6 different measurements. Statistical analysis was by one way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons. *, p<0.001 vs. all other groups. (D) Protein levels of TLR4. Data shows mean ± SD and n=6 different measurements. Statistical analysis was by one way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons. *, p<0.001 vs. all other groups. (E) Myeloid differentiation primary response protein (MyD88), phospho-ERK and phospho-NF-kB was immunofluorescent stained in HCT-116 cells. (40× objective). (F) MyD88 fluorescence staining was quantified using ImageJ software. Values are mean ± SD and n=8. Statistical analysis was by one way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons. *, p < 0.001, vs. all other groups. **, p < 0.001, vs. control and DMSO groups. (G) Protein levels of MyD88. Data shows mean ± SD and n=6 different measurements. Statistical analysis was by one way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons. *, p<0.001 vs. all other groups. (H) Phospho-ERK fluorescence staining was quantified using ImageJ software. Values are mean ± SD and n=8. Statistical analysis was by one way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons. *, p < 0.01, vs. all other groups. (I) Phospho-NF-kB fluorescence staining was quantified using ImageJ software. Statistical analysis was by one way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons. *, p<0.001 vs. all other groups. (J) Protein levels of tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α). Data shows mean ± SD and n=6 different measurements. Statistical analysis was by Kruskal-Wallis test and the difference between the groups was determined by Dunn’s multiple comparisons. *, p<0.05 vs. control, DMSO and SsnB. (K) Protein levels of interleukin 1Β (IL-1B). Data shows mean ± SD and n=6 different measurements. Statistical analysis was by one way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons. *, p<0.05 vs. all other groups. (L) Protein levels of IL-6. Data shows mean ± SD and n=6 different measurements. Statistical analysis was by one way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons. *, p<0.001 vs. all other groups.

Figure 2.

Evaluation of the TLR2-TLR4 signaling pathway in HCT-116 cells. Cells were treated with DMSO (1 μL/mL), SsnB (25 μM), and/or PMA (10 nM) for 12 h in all experiments. (A) PCR analysis of TLR2. Data shows mean ± SD and n=4 different measurements. Statistical analysis was performed by Kruskal-Wallis test and the difference between the groups was determined by Tukey's test. *, p<0.05 vs. SsnB. (B) PCR analysis of TLR4. Data shows mean ± SD and n=4 different measurements. Statistical analysis was performed by Kruskal-Wallis test and the difference between the groups was determined by Tukey's test. *, p<0.01 vs. SsnB. (C) Protein levels of Toll-like Receptor 2 (TLR2). Data shows mean ± SD and n=6 different measurements. Statistical analysis was by one way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons. *, p<0.001 vs. all other groups. (D) Protein levels of TLR4. Data shows mean ± SD and n=6 different measurements. Statistical analysis was by one way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons. *, p<0.001 vs. all other groups. (E) Myeloid differentiation primary response protein (MyD88), phospho-ERK and phospho-NF-kB was immunofluorescent stained in HCT-116 cells. (40× objective). (F) MyD88 fluorescence staining was quantified using ImageJ software. Values are mean ± SD and n=8. Statistical analysis was by one way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons. *, p < 0.001, vs. all other groups. **, p < 0.001, vs. control and DMSO groups. (G) Protein levels of MyD88. Data shows mean ± SD and n=6 different measurements. Statistical analysis was by one way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons. *, p<0.001 vs. all other groups. (H) Phospho-ERK fluorescence staining was quantified using ImageJ software. Values are mean ± SD and n=8. Statistical analysis was by one way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons. *, p < 0.01, vs. all other groups. (I) Phospho-NF-kB fluorescence staining was quantified using ImageJ software. Statistical analysis was by one way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons. *, p<0.001 vs. all other groups. (J) Protein levels of tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α). Data shows mean ± SD and n=6 different measurements. Statistical analysis was by Kruskal-Wallis test and the difference between the groups was determined by Dunn’s multiple comparisons. *, p<0.05 vs. control, DMSO and SsnB. (K) Protein levels of interleukin 1Β (IL-1B). Data shows mean ± SD and n=6 different measurements. Statistical analysis was by one way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons. *, p<0.05 vs. all other groups. (L) Protein levels of IL-6. Data shows mean ± SD and n=6 different measurements. Statistical analysis was by one way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons. *, p<0.001 vs. all other groups.

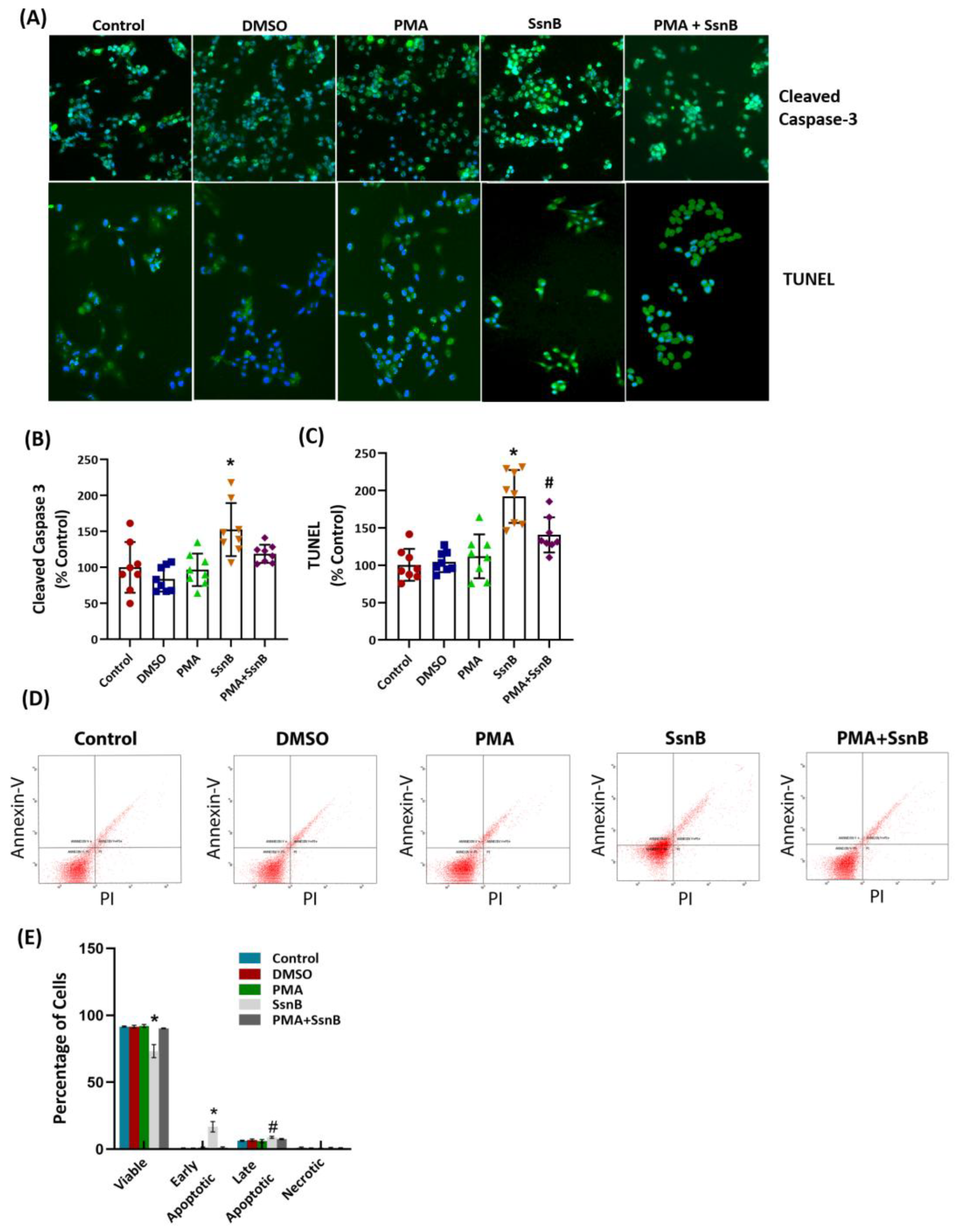

Figure 3.

Apoptosis in HCT-116 cells. Cells were treated with DMSO (1 μL/mL), SsnB (25 μM), and/or PMA (10 nM) for 12 h in all experiments. (A) Representative immunofluorescent cleaved caspase-3 and TUNEL staining. Double-labeled images were obtained using a 40x objective lens. (B) Cleaved caspase-3 fluorescence staining was quantified using ImageJ software. Values are mean ± SD and n=8 different measurements. Statistical analysis was by one way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons. *, p < 0.01, vs. control, DMSO and PMA. (C) TUNEL staining was quantified using ImageJ software. Values are mean ± SD and n=8. Statistical analysis was by one way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons. *, p < 0.01, vs. all other groups. #, p<0.05 vs. control. (D) Representative analysis of apoptosis in HCT-116 cells by Annexin V–FITC and PI labeled flow cytometry. In each panel, the lower left quadrant shows viable cells, the upper left quadrant shows early apoptotic cells, the upper right quadrant shows late apoptotic cells, and the lower right quadrant shows necrotic cells. 10,000 cells were gated and analyzed for each condition. (E) Quantitative analysis of Annexin-V and PI labeling in HCT-116 cells experimental groups by flow cytometry. Data are representative of three separate experiments and values are given as mean ± SD. Statistical analysis was performed by one-way ANOVA analysis. The difference between groups was determined by the Tukey test. *, p<0.05, compared to control, DMSO, PMA and PMA+SsnB groups. #, p<0.05, compared to control and PMA groups.

Figure 3.

Apoptosis in HCT-116 cells. Cells were treated with DMSO (1 μL/mL), SsnB (25 μM), and/or PMA (10 nM) for 12 h in all experiments. (A) Representative immunofluorescent cleaved caspase-3 and TUNEL staining. Double-labeled images were obtained using a 40x objective lens. (B) Cleaved caspase-3 fluorescence staining was quantified using ImageJ software. Values are mean ± SD and n=8 different measurements. Statistical analysis was by one way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons. *, p < 0.01, vs. control, DMSO and PMA. (C) TUNEL staining was quantified using ImageJ software. Values are mean ± SD and n=8. Statistical analysis was by one way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons. *, p < 0.01, vs. all other groups. #, p<0.05 vs. control. (D) Representative analysis of apoptosis in HCT-116 cells by Annexin V–FITC and PI labeled flow cytometry. In each panel, the lower left quadrant shows viable cells, the upper left quadrant shows early apoptotic cells, the upper right quadrant shows late apoptotic cells, and the lower right quadrant shows necrotic cells. 10,000 cells were gated and analyzed for each condition. (E) Quantitative analysis of Annexin-V and PI labeling in HCT-116 cells experimental groups by flow cytometry. Data are representative of three separate experiments and values are given as mean ± SD. Statistical analysis was performed by one-way ANOVA analysis. The difference between groups was determined by the Tukey test. *, p<0.05, compared to control, DMSO, PMA and PMA+SsnB groups. #, p<0.05, compared to control and PMA groups.

Table 1.

Sphingolipid levels in HCT-116 cells.

Table 1.

Sphingolipid levels in HCT-116 cells.