1. Introduction

The communication that arises between people has undergone continuous changes during the last decades due to digital technologies [

1]. The era of information and communication technologies (ICT) began in the early 90’s, whose development and diffusion contribute to various areas of people’s lives [

2]. The incorporation of ICT has changed the nature of communication, socialization, entertainment, shopping and learning [

3]. ICT increase economic growth in both rich and poor countries, with the benefits of their use being greater in the latter, so stimulating the use of ICTs in these countries by reducing the cost of Internet and cell phones is of vital importance [

4]. ICT transform the structure and enhance the activity of different economic sectors through various channels, resulting in good economic performance, improved productivity, cost reduction and labor efficiency [

5]. In both developing and developed countries, ICT have changed daily life at the individual, organizational and national levels [

6], transforming the way activities are carried out in both the social and economic spheres [

7]. However, according to Chesley [

8], the use of ICT may have negative implications, as they could be significantly altering the working conditions of contemporary workers. According to Salanova [

9] the use of ICT can trigger technostress, which is defined as a negative psychological state related to the use of ICTs or the threat of their use in the future, which is conditioned by the perception of a mismatch between the demands and resources related to the use of ICT that leads to a high level of unpleasant psychophysiological activation and the development of negative attitudes towards ICT. A specific experience of technostress is technoaddiction, due to an excessive use and an uncontrollable compulsion to use technology at all times and in any place and for long periods of time [

10]. According to Samaha and Hawi [

11] technoaddiction has a significant negative impact on a personal level, decreasing satisfaction with life. On the other hand, the excessive use of ICT could lead to different adverse effects on physical and mental health [

12]. In this regard, it has been reported that addictive behavior in the use of ICT can cause people to be physically inactive [

13,

14]. The relationship between techno addiction and physical activity has been investigated in several studies. A study among young adults found a moderately negative correlation between mobile phone addiction and physical activity [

15], suggesting that those young adults with higher levels of mobile phone addiction had lower levels of physical activity. A similar finding was reported in a study on university students, which indicated that individuals with a stronger addiction to smartphones exhibited lower levels of physical activity [

16]. Wang et al. [

17] investigated the mediating role of subjective well-being in the relationship between physical activity and internet addiction among students. The study concluded that physical activity directly reduces internet addiction and indirectly influences it by enhancing subjective well-being.The aim of this study is to systematically review the relationship between technoaddiction and physical activity to answer the following questions: Are there specific relationships according to population characteristics? Is technoaddiction associated with low levels of physical activity?

2. Materials and Methods

In this review, the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and MetaA-nalyses (PRISMA) guidelines [

18,

19,

20] were used, and the PICOS (participants, inter-ventions, comparators, outcomes, and study design) strategy was used to establish the eligibility criteria for the articles [

21].

According to Grant and Booth there are 14 different types of reviews used in scientific research. These are the critical review, literature review, mapping review/systematic map, meta-analysis, mixed studies review/mixed methods review, overview, qualitative systematic review/qualitative evidence synthesis, rapid review, scoping review, state-of-the-art review, systematic review, systematic search and review, systematized review, and umbrella review. The systematic review systematically evaluates and synthesizes research evidence by adhering to certain established guidelines in order to perform a thorough and comprehensive search, and integrates a quality assessment of articles, which can determine inclusion or exclusion of these [

22].

According to the current checklist of the PRISMA guidelines [

20], the following quality steps for systematic reviews were verified according to the following items: (1) title, (2) structured abstract, (3) rationale, (4) objectives, (5) eligibility criteria, (6) sources of information, (7) search strategy, (8) selection process, (9) data extraction process, (10a) and (10b) data items, (11) study risk of bias assessment, (14) reporting bias assessment, (16a) and (16b) study selection, (17) study characteristics, (18) risk of bias in studies, (19) results of individual studies, (20) results of syntheses, (23) discussion, (25) support, (26) competing interests, and (27) availability of data, code, and other materials. The following items were excluded from the PRISMA guidelines due to their non-applicability to the objectives of this review: (12) effect measures, (13) methods of synthesis, (15) certainty assessment, (21) reporting biases, (22) certainty of evidence, and (24) registration and protocol. In addition, the initial search for articles was performed using bibliometric procedures [

23].

2.1. Search Strategy

A set of articles was used as a homogeneous citation base, avoiding the impossibility of comparing indexing databases that use different calculation bases to determine journals’impact factors and quartiles [

24,

25,

26,

27,

28], relying on the Web of Science (WoS) core collection, selecting articles published in journals indexed this database, from a search vector on Technoaddiction: {TS = (technoaddiction OR (technological NEAR/0 addiction))}, and on the Scopus database, from a search vector on Technoaddiction: {(TITLE-ABS-KEY (technoaddiction) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (technological W/0 addiction))}, without restricted temporal parameters. The extraction was performing on 25 november 2024. Only documents typified by WoS and Scopus as articles were included, regardless of whether these documents had additional parallel typification by these databases.

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

The selection of articles was specified based on eligibility criteria: the target population (participants), the interventions (methodological techniques), the elements of comparison of these studies, the outcomes of these studies, and the study designs (the criteria of the PICOS strategy as shown in

Table 1).

2.3. Study Selection and Data Extraction

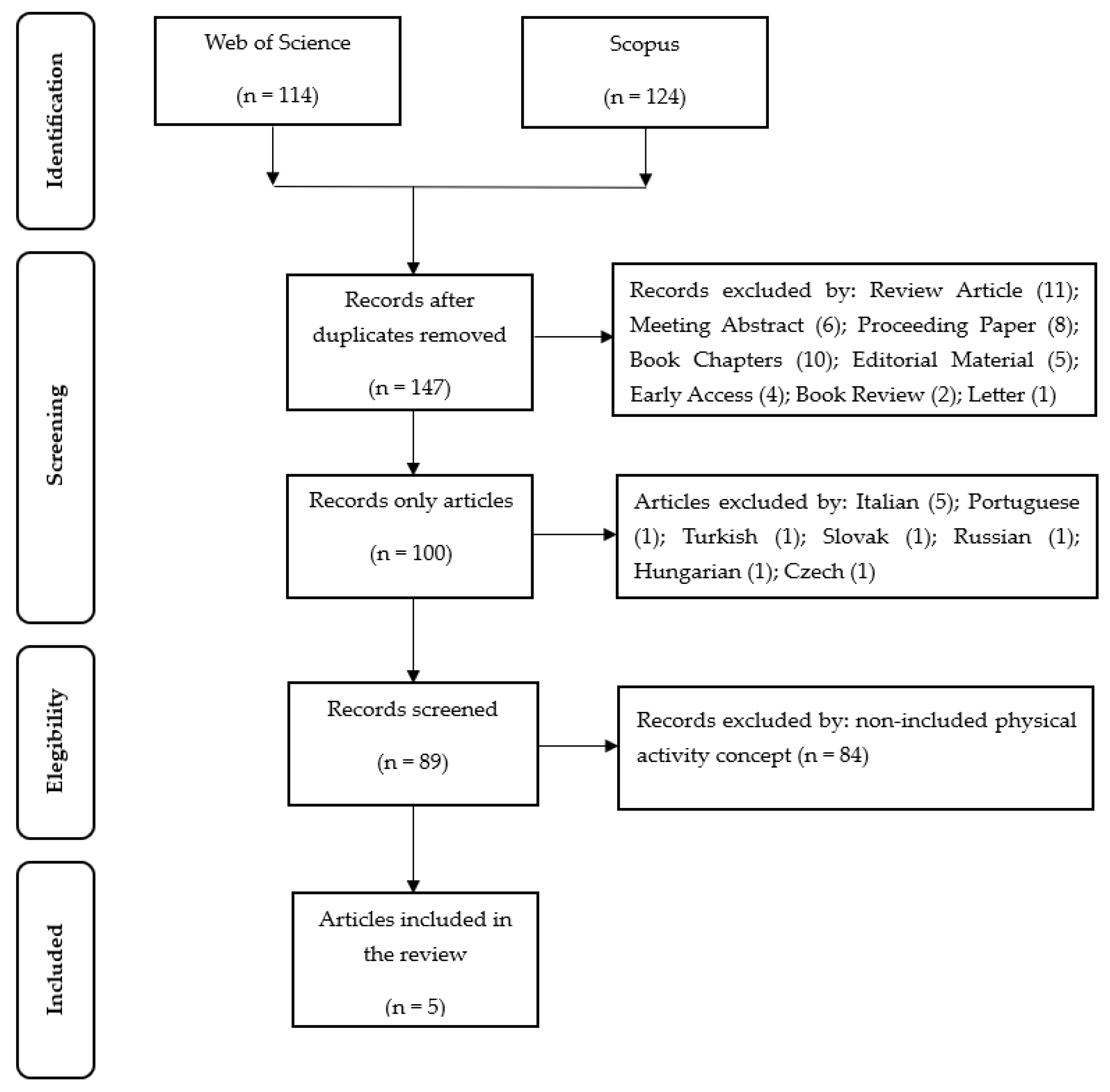

In the first step, any duplicates were manually removed. Then, the titles and abstracts of articles were checked for relevance by two researchers. They subsequently, independently from each other, reviewed the full texts of potentially eligible articles. Any disagreements were discussed with a third researcher until consensus was reached.

Then, they excluded reviews, meeting abstracts, proceedings papers, book chapters, editorial materials, early access, book reviews, and letters. They excluded articles that were not related to the concept of physical activity. Also, articles in Italian, Portuguese, Turkish, Slovak, Russian, Hungarian, and Czech were excluded.

2.4. Quality Assessment and Risk of Bias

The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) scale was used for the assessment of the risk of bias among the included studies. The MMAT scale is a valid measure of the methodological quality of the article. Two authors independently conducted the studies, and a third author was recruited in case of any argument.

Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT), a checklist used in systematic reviews based on synthesis of qualitative and quantitative evidence, includes criteria for the evaluation of mixed studies; it defines the study category, and 7 items are applied according to a score from zero to one, to obtain a final percentage mean. Studies are considered as high quality > 75%, moderate quality 50–74%, and low quality < 49%. Studies with values below 75% were excluded from the category analysis and discussion [

30].

3. Results

The search vector extracted a total of 147 records without repetitions from Web of Science database and Scopus database from 2000 to 2024. Excluding records according to the PICOS tool (see

Table 1), non-article records (47) and non-English-language and non-Spanish-language articles (11) resulted in 89 records for screening (details in

Supplementary File Table S1). In addition, 84 articles not related to the physical activity concept are also excluded. Thus, reducing the corpus analyzed to 5 full-text articles in English and Spanish retrieved and screened using the selection criteria defined in the previous section (See

Figure 1).

Using the PRISMA guidelines, five articles were selected [

20].

Table 2 shows details, which are authors, publication sources, indexation, citations, and study designs. In addition,

Table 3 details each 5 articles’ eligibility criteria using (MMAT) Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool.

All studies are considered as high quality >75%, and were included from the analysis, and discussion.

Table 2.

Selected articles by PRISMA guidelines.

Table 2.

Selected articles by PRISMA guidelines.

| Authors |

Affiliations |

Journal |

Publication

Year |

Sample |

WoS Index |

Pubmed

(Y/N) |

Times Cited,

WoS Core |

Category of

Study Designs |

| Mamani-Jilaja et al. [31] |

Universidad Nacional del Altiplano Puno |

Retos |

2024 |

n = 384 |

ESCI |

N |

0 |

Quantitative descriptive |

| Ospankulov et al. [32] |

Kazakh National Pedagogical University named after Abay; Ataturk University; Al-Farabi Kazakh National University; L.N. Gumilyov Eurasian National University |

International Journal of

Education in Mathematics, Science, and Technology |

2023 |

n = 252 |

ESCI |

N |

2 |

Quantitative descriptive |

| Tarjibayeva et al. [33] |

The National Academy of Education named after I. Altynsarin; National Scientific and Practical Center of Physical Culture

of Education and Science of the Republic of Kazakhstan; |

International Journal of Education in Mathematics, Science,

and Technology |

2023 |

n = 60 |

ESCI |

N |

0 |

Quantitative non-randomized |

| Estrada-Araoz et al. [34] |

Universidad Nacional Amazónica de Madre de Dios |

Brazilian Journal of Rural Education |

2021 |

n = 232 |

ESCI |

N |

1 |

Quantitative descriptive |

| Hosen et al. [35] |

CHINTA Research Bangladesh, Dhaka; Department of Public Health and Informatics, Jahangirnagar University, Dhaka; Department of Management Sciences, Shaheed Zulfikar Ali Bhutto Institute of Science and Technology, Islamabad; Exercise Psychophysiology Laboratory, Institute of KEEP Collaborative Innovation, School of Psychology, Shenzhen University |

Risk Management and Healthcare Policy |

2021 |

n = 601 |

SCI-E + SSCI |

Y |

52 |

Quantitative descriptive |

Table 3.

Eligibility criteria using (MMAT) Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool.

Table 3.

Eligibility criteria using (MMAT) Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool.

| Authors |

Journal |

Publication

Year |

Category of

Study Designs |

S1 |

S2 |

1,1 |

1,2 |

1,3 |

1,4 |

1,5 |

2,1 |

2,2 |

2,3 |

2,4 |

2,5 |

3,1 |

3,2 |

3,3 |

3,4 |

3,5 |

4,1 |

4,2 |

4,3 |

4,4 |

4,5 |

Quality |

| Mamani-Jilaja et al. [31] |

International Journal of

Education in Mathematics, Science, and Technology |

2024 |

Quantitative descriptive |

1.0 |

1.0 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

1.0 |

1.0 |

1.0 |

0.0 |

1.0 |

86% |

| Ospankulov et al. [32] |

International Journal of Education in Mathematics, Science,

and Technology |

2023 |

Quantitative descriptive |

1.0 |

1.0 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

1.0 |

0.0 |

1.0 |

1.0 |

1.0 |

86% |

| Tarjibayeva et al. [33] |

Brazilian Journal of Rural Education |

2023 |

Quantitative non-randomized |

1.0 |

1.0 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

1.0 |

1.0 |

1.0 |

0.0 |

1.0 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

86% |

| Estrada-Araoz et al. [34] |

Risk Management and Healthcare Policy |

2021 |

Quantitative descriptive |

1.0 |

1.0 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

1.0 |

1.0 |

1.0 |

0.0 |

1.0 |

86% |

| Hosen et al. [35] |

International Journal of

Education in Mathematics, Science, and Technology |

2021 |

Quantitative descriptive |

1.0 |

1.0 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

1.0 |

1.0 |

1.0 |

0.0 |

1.0 |

86% |

Mamani-Jilaja et al. [

31] analyzed the relationship between cell phone dependency and physical activity in Peruvian university students, using two questionnaires; the first one called mobile phone dependency [

36], composed of 22 items to be evaluated with a Likert-type response scale; and the second one of their own elaboration called physical activity in university students, constructed on the basis of ten items with a dichotomous response scale. According to the results obtained, cell phone dependence had a significant impact, 86%, on the low rate of physical activity among students.

The research by Ospankulov et al. [

32] studied the relationship between participation in sports and technological addictions in elementary school students and, in addition, whether there were differences according to sex and type of school, whether public or private. The Technology Addiction Scale [

37], which consists of four subdimensions with a five-point Likert-type scale; and the Sport Participation Questionnaire scale [

38], which consists of 20 items in total with a five-point Likert-type scale, were used. It was found that participation in sports was at a moderate level, with no significant differences according to sex and type of school. Participants’ online gaming habits were found to be high and their techno-logical addictions moderate, with differences according to sex and type of school. In general, it was found that females used social networks more, while males partially showed a high level of addiction to digital games. There was a significant negative relationship between technological addiction and the level of physical activity, where the level of addiction of students who regularly play sports is lower than that of those who do not.

The study by Tarjibayeva et al. [

33] examined the effect of an in-training program developed to increase healthy nutrition, physical activity and reduce technological addiction on the behaviors and habits of young athletes. An experimental and control group was formed, each of 30 people, with 15 female and 15 male athletes in each, with an average age of 16.8 years in the experimental group, and 16.9 years in the control group. In the experimental group, a program of nutritional education, physical activity and reduction of technology addiction was applied. The Dutch Eating Behavior Scale [

39], which consists of three subscales: emotional eating, restrictive eating and external eating; the Physical Activity Questionnaire [

40], which consists of 9 questions in which the answers given to the questionnaire are scored between 1 and 5 and the 10th question that asks if there is any obstacle to physical activity during the last week; and the Technology Addiction Scale [

37], which consists of four subdimensions with a five-point Likert-type scale, were applied. According to the results of the study, the athletes in the experimental group, to whom the program was applied, showed a significant decrease in negative eating behaviors, a significant increase in physical activity levels, and a significant decrease in techno-logical addictions, compared to their peers in the control group.

Estrada-Araoz et al. [

34] described the technostress of students of the professional career of Education of a public university in the Peruvian Amazon during the COVID-19 pandemic. A Technostress Questionnaire [

41] consisting of 20 items with a five-point Likert-type scale was applied, which evaluates 3 dimensions: technoanxiety (items 1 to 9), technoaddiction (items 10 to 17) and technofatigue (items 18 to 20). It was found that students were characterized by moderate levels of technostress, with low levels of technoanxiety and moderate levels of technoaddiction and technofatigue. In addition, women who were younger and working had slightly higher levels of technostress. The research suggests that it would be important to encourage digital disconnection for students to engage in physical activities, family care and socialization.

Hosen et al. [

35] investigated the prevalence and associated factors of problematic smartphone use during the COVID19 pandemic among Bangladeshi students. They applied the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-2) scale for depression [

42,

43], the Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD-2) scale for anxiety [

43,

44], and the Smartphone Application-Based Addiction Scale for problematic smartphone use [

45]. It is highlighted that approximately half of the respondents were engaged in physical exercise, while 53.9% reported sleeping 6-7 hours per day, more than half of the respondents reported using the internet for a longer period (more than 5 hours), 43.3% and 32.6% of the participants, respectively, scored as depressed and anxious, 86.9% of participants had problematic smartphone use, with no significant differences according to gender, and participants who were physically inactive were more likely to be addicted compared to others. Participants who suffered from psychological problems, such as depression and anxiety, were significantly more likely to be problematic smartphone users.

4. Discussion

The systematic review presented in this manuscript examines 147 scientific articles from Web of Science and Scopus databases on physical activity associated with the technoaddiction, performing a screening that results in 5 articles being reviewed in depth.

According to the relationship between technoaddiction and physical activity levels, the studies reviewed clearly highlight a significant negative relationship between technoaddiction and physical activity. For instance, Mamani-Jilaja et al. [

31] found that cell phone dependency significantly impacted Peruvian university students, with 86% showing lower physical activity rates. Similarly, Ospankulov et al. [

32] reported that students with higher technological addiction levels demonstrated lower participation in sports, emphasizing the detrimental effects of technoaddiction on physical activity habits.

These findings suggest that excessive reliance on technology displaces time that could otherwise be allocated to physical activity, highlighting a direct trade-off between sedentary behaviors and active lifestyles.

In reference with the population-specific relationships. The University Students, oth Mamani-Jilaja et al. [

31] and Estrada-Araoz et al. [

34] explored technoaddiction in university students, emphasizing its impact during critical developmental phases. Estrada-Araoz et al. [

34] also noted moderate levels of technostress during the COVID-19 pandemic, with students reporting moderate levels of technoaddiction and low levels of physical activity.

In elementary school students, Ospankulov et al.’s findings [

32] show different patterns in younger populations, where digital gaming addiction was more prominent among boys, while social media usage was higher among girls. Both forms of addiction correlated with lower physical activity levels, regardless of school type (public or private).

The study over athletes, Tarjibayeva et al. [

33] demonstrated that structured interventions combining physical activity, nutritional education, and technology addiction reduction strategies yielded positive outcomes in adolescent athletes. This suggests that even among active individuals, targeted programs are necessary to mitigate the influence of technology.

Under pandemic contexts, Hosen et al. [

35] highlighted the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on increased smartphone addiction and associated physical inactivity in Bangladeshi students. This period further exacerbated sedentary behaviors and highlighted the link between psychological distress (e.g., anxiety and depression) and problematic smartphone use.

Related to the impact of interventions, Tarjibayeva et al.’s [

33] study underscores the efficacy of intervention programs in combating the negative effects of technoaddiction. By introducing structured physical activity programs alongside nutritional education, the experimental group exhibited a significant decrease in technology addiction, an increase in physical activity, and improved eating behaviors. This provides a potential model for addressing technoaddiction in broader populations.

Ospankulov et al. [

32] and Estrada-Araoz [

34] et al. identified gender-based differences, where women exhibited higher social media usage and slightly higher technostress levels, while men were more prone to gaming addiction. These differences suggest that interventions may need to be tailored based on demographic characteristics to effectively address the root causes of technoaddiction and encourage physical activity.

Finally, there are broader implications, related to psychological health, Hosen et al.’s findings [

35] indicate a strong association between psychological issues such as depression and anxiety and problematic smartphone use. This suggests a cyclical relationship: technological addiction not only decreases physical activity but also exacerbates mental health issues, which in turn increases dependence on technology.

Also associated with psychological health, Estrada-Araoz et al. [

34] emphasized the importance of encouraging digital disconnection to promote physical activities, family interaction, and socialization. This aligns with the broader notion that balancing digital engagement and physical activity is critical for holistic well-being.

5. Conclusions

The evidence reviewed demonstrates a clear and significant relationship between technoaddiction and reduced physical activity, with notable variations across age, gender, and contextual factors. To address these issues, it’s necessary an educational campaigns, associated with raise awareness about the impact of excessive technology use on physical health. Also structured interventions, implement programs that combine physical activity, healthy habits, and technology use reduction. Promote digital detox, based on encouraging scheduled breaks from technology to engage in physical activities, especially in university and school settings.

Associated with mental health support, its key integrates psychological counseling to address underlying issues, like anxiety and depression that contribute to technoaddiction. Finally develop tailored solutions, where design interventions that consider demographic characteristics, including gender and activity levels.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.E.-M., F.M.-C. and A.V.-M.; methodology, C.E.-M. and A.V.-M.; validation, C.E.-M. and N.S.G.; formal analysis, C.E.-M., F.M.-C., M.E.G.V. and A.V.-M.; writing—original draft preparation, C.E.-M., F.M.-C., M.E.G.V., A.V.-M., N.S.G., G.S.-S. and J.C.A.; writing—review and editing, C.E.-M., F.M.-C., G.S.-S. and J.C.A.; supervision, C.E.-M.; funding acquisition, C.E.-M., A.V.-M., N.S.G. and G.S.-S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The Article Processing Charge (APC) was partially funded by Universidad de Concepción (Code: VRID Nº 2023000959INT). Additionally, the publication fee (APC) was partially financed through the Publication Incentive Fund, 2025, by the Universidad Central de Chile (Code: APC2025), Universidad Arturo Prat (Code: APC2025), Universidad Finis Terrae (Code: APC2025), Universidad Católica de la Santísima Concepción (Code: APC2025), and Universidad de Las Américas (Code: APC2025).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable; this study does not involve humans or animals.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Fernández-Batanero, J. M.; Montenegro-Rueda, M.; Fernández-Cerero, J.; García-Martínez, I. Digital competences for teacher professional development. Systematic review. Eur. J. Teach. Educ. 2020, 1–19. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, Z.; Le, H. P. Linking Information communication technology, trade globalization index, and CO2 emissions: Evidence from advanced panel techniques. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 8770–8781. [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, F.; Ward, R.; Ahmed, E. Investigating the influence of the most commonly used external variables of TAM on students’ Perceived Ease of Use (PEOU) and Perceived Usefulness (PU) of e-portfolios. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 63, 75–90. [CrossRef]

- Appiah-Otoo, I.; Song, N. The impact of ICT on economic growth—Comparing rich and poor countries. Telecommun. Policy 2021, 45, 102082. [CrossRef]

- Kallal, R.; Haddaji, A.; Ftiti, Z. ICT diffusion and economic growth: Evidence from the sectorial analysis of a periphery country. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2021, 162, 120403. [CrossRef]

- Roztocki, N.; Weistroffer, H. R. Conceptualizing and researching the adoption of ICT and the impact on socioeconomic development. Inf. Technol. Dev. 2016, 22, 541–549. [CrossRef]

- Rao-Nicholson, R.; Vorley, T.; Khan, Z. Social innovation in emerging economies: A national systems of innovation-based approach. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2017, 121, 228–237. [CrossRef]

- Chesley, N. Information and communication technology use, work intensification and employee strain and distress. Work Emp. Soc. 2014, 28, 589–610. [CrossRef]

- Salanova, M. S. Trabajando con tecnologías y afrontando el tecnoestrés: El rol de las creencias de eficacia. Rev. Psicol. Trab. Organ. 2003, 19(3), 225–246. http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=231318057001.

- Salanova, M. S.; Llorens, S.; Cifre, E.; Nogareda, C. NTP 730: Tecnoestrés: Concepto, medida e intervención psicosocial. Inst. Nac. Seg. Hig. Trab. 2007. Available online: https://www.insst.es/documents/94886/327446/ntp_730.pdf/55c1d085-13e9-4a24-9fae-349d98deeb8a (accessed on 16 December 2024).

- Samaha, M.; Hawi, N. S. Relationships among smartphone addiction, stress, academic performance, and satisfaction with life. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 57, 321–325. [CrossRef]

- Elhai, J. D.; Dvorak, R. D.; Levine, J. C.; Hall, B. J. Problematic smartphone use: A conceptual overview and systematic review of relations with anxiety and depression psychopathology. J. Affect. Disord. 2017, 207, 251–259. [CrossRef]

- Hinojo-Lucena, F. J.; Aznar-Díaz, I.; Cáceres-Reche, M. P.; Trujillo-Torres, J. M.; Romero-Rodríguez, J. M. Problematic Internet Use as a Predictor of Eating Disorders in Students: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Study. Nutrients 2019, 11(9), 2151. [CrossRef]

- Cóndor-Chicaiza, J.; Chimba-Santillán, A.; Cóndor-Chicaiza, M.; Romero-Obando, M.; Posso-Pacheco, R. Desarrollo de proyectos interdisciplinarios en la educación remota ecuatoriana. Rev. EDUCARE 2021, 25(2), 306–321. [CrossRef]

- Xiao, W.; Wu, J.; Yip, J.; Shi, Q.; Peng, L.; Lei, Q. E.; Ren, Z. The Relationship Between Physical Activity and Mobile Phone Addiction Among Adolescents and Young Adults: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Observational Studies. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2022, 8, e41606. [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.-E.; Kim, J.-W.; Jee, Y.-S. Relationship between smartphone addiction and physical activity in Chinese international students in Korea. J. Behav. Addict. 2015, 4, 200–205. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Xu, X.; Wu, Q.; Zhou, C.; Yang, G. The mediating effect of subject well-being between physical activity and internet addiction of college students in China during the COVID-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional study. Front. Public Health 2024, 12, 1368199. [CrossRef]

- Liberati, A.; Altman, D.G.; Tetzlaff, J.; Mulrow, C.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Ioannidis, J.P.; Clarke, M.; Devereaux, P.J.; Kleijnen, J.; Moher, D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: Explanation and elaboration. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2009, 62, e1–e34.

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. The PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for sstematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097.

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, 71.

- Methley, A.M.; Campbell, S.; Chew-Graham, C.; McNally, R.; Cheraghi-Sohi, S. PICO, PICOS and SPIDER: A comparison study of specificity and sensitivity in three search tools for qualitative systematic reviews. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2014, 14, 579.

- Grant, M.J.; Booth, A. A typology of reviews: An analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Inf. Libr. J. 2009, 26, 91–108. [CrossRef]

- Porter, A.L.; Kongthon, A.; Lu, J.C. Research profiling: Improving the literature review. Scientometrics 2002, 53, 351–370.

- Mongeon, P.; Paul-Hus, A. The journal coverage of Web of Science and Scopus: A comparative analysis. Scientometrics 2016, 106, 213–228.

- Harzing, A.-W.; Alakangas, S. Google Scholar, Scopus and the Web of Science: A longitudinal and cross-disciplinary comparison. Scientometrics 2016, 106, 787–804.

- Falagas, M.E.; Pitsouni, E.I.; Malietzis, G.; Pappas, G. Comparison of PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar: Strengths and weaknesses. FASEB J. 2008, 22, 338–342.

- Chadegani, A.A.; Salehi, H.; Yunus, M.M.; Farhadi, H.; Fooladi, M.; Farhadi, M.; Ebrahim, N.A. A comparison between two main academic literature collections: Web of Science and Scopus databases. ASS 2013, 9, 5.

- Bakkalbasi, N.; Bauer, K.; Glover, J.; Wang, L. Three options for citation tracking: Google Scholar, Scopus and Web of Science. Biomed. Digit. Libr. 2006, 3, 7.

- Hong, Q.N.; Fàbregues, S.; Bartlett, G.; Boardman, F.; Cargo, M.; Dagenais, P.; Gagnon, M.; Griffiths, F.; Nicolau, B.; O’Cathain, A.; et al. The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) version 2018 for information professionals and researchers. Educ. Inf. 2018, 34, 285–291.

- Arenas-Monreal, L.; Galvan-Estrada, I. G.; Dorantes-Pacheco, L.; Márquez-Serrano, M.; Medrano-Vázquez, M.; Valdez-Santiago, R.; Piña-Pozas, M. Alfabetización sanitaria y COVID-19 en países de ingreso bajo, medio y medio alto: Revisión sistemática. Global. Health Promot. 2023, 17579759221150207.

- Mamani-Jilaja, D.; Laque-Córdova, G.; & Flores-Chambilla, S. Mobile phone dependence and low physical activity in university students. Retos: Nuevas Tend. Educ. Fís. Deporte Recreación 2024, 56, 974–980.

- Ospankulov, Y.; Nurgaliyeva, S.; Zhumabayeva, A.; Zhunusbekova, A.; Tolegenuly, N.; Kozhamkulova, N.; Zhalel, A. Examining the relationships between primary school students’ participation in sports and technology addictions. Int. J. Educ. Math. Sci. Technol. 2023, 11(3), 804–819. [CrossRef]

- Tarjibayeva, S.; Adilova, V.; Tsitsurin, V.; Sadykov, S.; Akhmetova, B. Investigation of the effects of the training program on negative nutrition and technology addiction in young athletes. Int. J. Educ. Math. Sci. Technol. 2023, 11(5), 1258–1274. [CrossRef]

- Estrada-Araoz, E. G.; Gallegos-Ramos, N. A.; Huaypar-Loayza, K. H.; Paredes-Valverde, Y.; Quispe-Herrera, R. Tecnoestrés en estudiantes de una universidad pública de la Amazonía peruana durante la pandemia COVID-19. Rev. Bras. Educ. Campo 2021, 6, e12777. [CrossRef]

- Hosen, I.; Al Mamun, F.; Sikder, M. T.; Abbasi, A. Z.; Zou, L.; Guo, T.; Mamun, M. A. Prevalence and Associated Factors of Problematic Smartphone Use During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Bangladeshi Study. Risk Manag. Healthc. Policy 2021, 14, 3797–3805. [CrossRef]

- Chóliz, M. Mobile phone addiction: a point of issue. Addiction 2010, 105(2), 373–374. [CrossRef]

- Young, K. S. Internet Addiction: The Emergence of a New Clinical Disorder. Cyberpsychol. Behav. 1998, 1(3), 237–244.

- Gill, D. L.; Gross, J. B.; Huddleston, S. Participation motivation in youth sports. Int. J. Sport Psychol. 1983, 14(1), 1–14.

- Van Strien, T.; Frijters, J. E.; Bergers, G. P.; Defares, P. B. The Dutch Eating Behavior Questionnaire (DEBQ) for assessment of restrained, emotional, and external eating behavior. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 1986, 5(2), 295–315.

- Kowalski, K. C.; Crocker, P. R.; Faulkner, R. A. Validation of the physical activity questionnaire for older children. Podiatry Exerc. Sci. 1997, 9(Suppl. 2), 174–186.

- Cazares, M. Adaptación de dos escalas para medir tecnoestrés y tecnoadicción en una población laboral mexicana. Tesis de Pregrado, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México: México, 2019.

- Kroenke, K.; Spitzer, R. L.; Williams, J. B. W. The Patient Health Questionnaire-2: validity of a two-item depression screener. Med. Care 2003, 41(11), 1284–1292. [CrossRef]

- Löwe, B.; Wahl, I.; Rose, M.; et al. A 4-item measure of depression and anxiety: validation and standardization of the Patient Health Questionnaire-4 (PHQ-4) in the general population. J. Affect. Disord. 2010, 122(1–2), 86–95. [CrossRef]

- Kroenke, K.; Spitzer, R. L.; Williams, J. B. W.; Monahan, P. O.; Löwe, B. Anxiety disorders in primary care: prevalence, impairment, comorbidity, and detection. Ann. Intern. Med. 2007, 146(5), 317–325. [CrossRef]

- Csibi, S.; Griffiths, M. D.; Cook, B.; Demetrovics, Z.; Szabo, A. The psychometric properties of the smartphone application-based addiction scale (SABAS). Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2018, 16(2), 393–403. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).