Submitted:

28 January 2025

Posted:

29 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

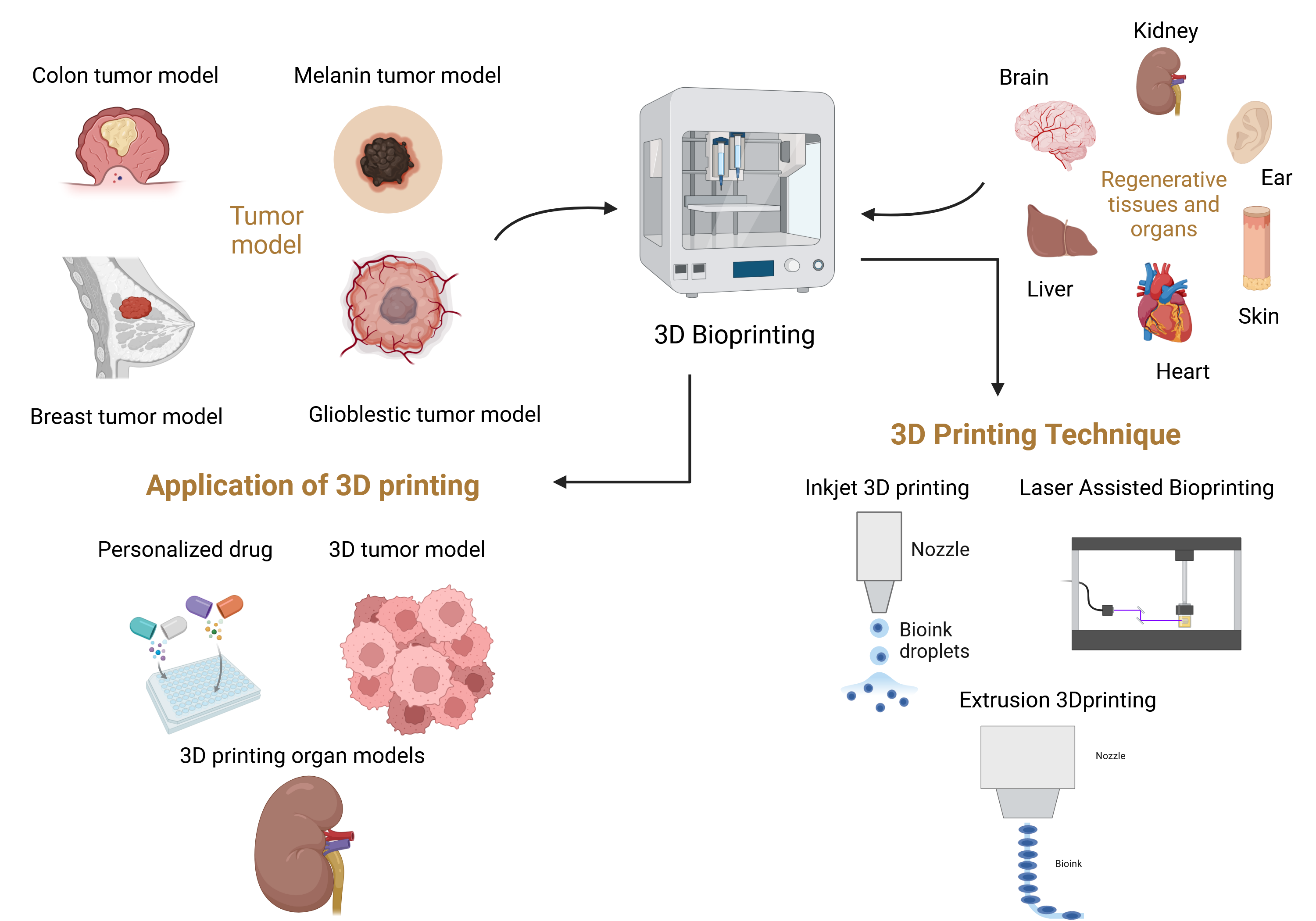

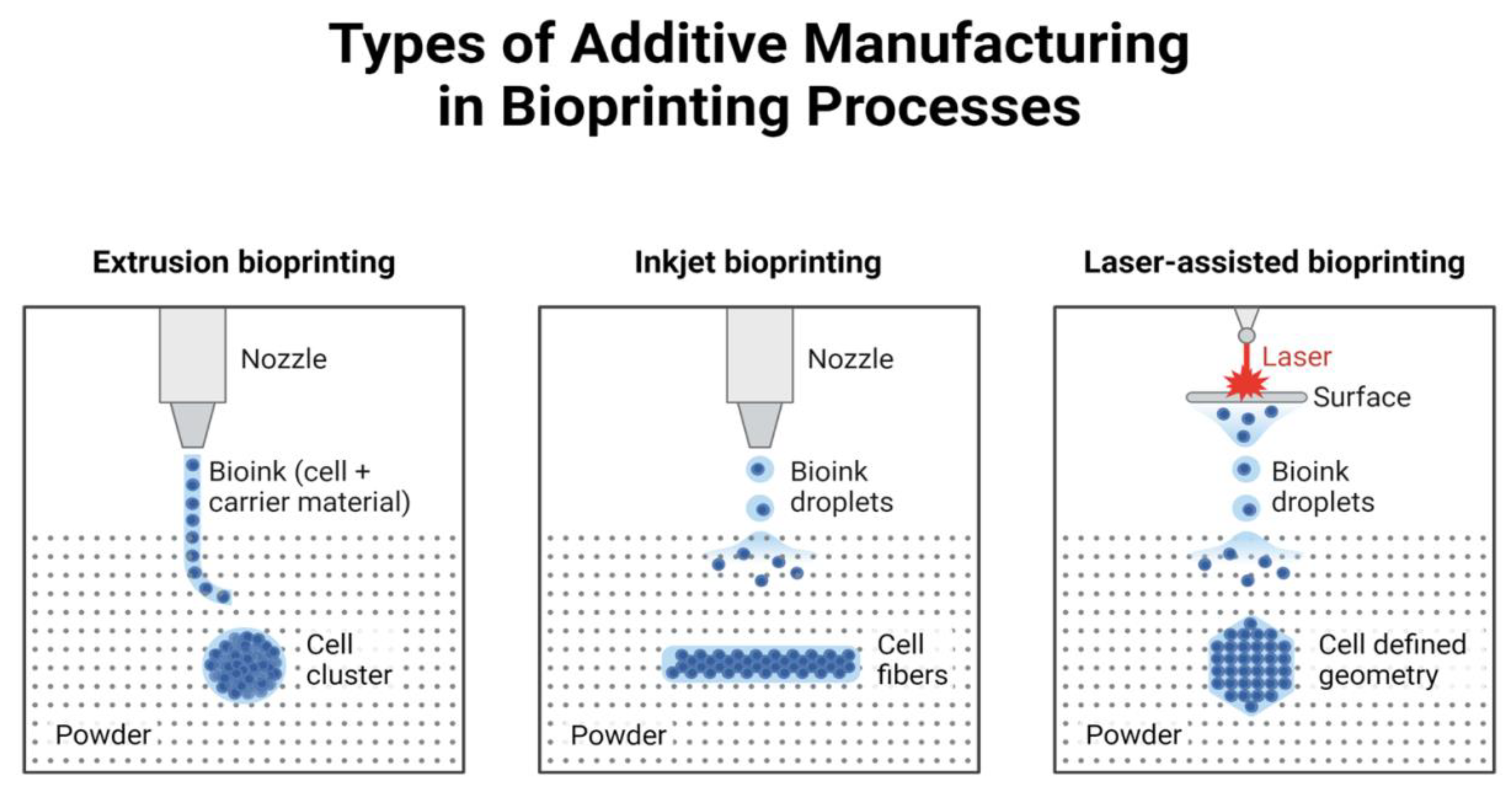

2. Technical Methods of 3D Printing

2.1. Inkjet Bioprinting

2.2. Extrusion Bioprinting

2.3. Light-Assisted Printing

2.3.1. Direct Laser Writing (DLW):

- High Precision: DLW enables the construction of microvascular networks, crucial for mimicking tumor angiogenesis.

- Customizability: The technique allows the incorporation of multiple bioinks, including cancer cell-laden hydrogels, extracellular matrix proteins, and growth factors, to create physiologically relevant models.

- Flexibility: It supports the integration of pre-formed cancer cell spheroids, allowing for rapid assembly of complex tumor structures.

- Material Limitations: The need for photosensitive bioinks restricts the range of compatible materials.

- Throughput: The high resolution of DLW comes at the cost of slower fabrication times, making it less suitable for large-scale models.

- Cost: The equipment and processing requirements for DLW are more expensive than alternative bioprinting methods, such as extrusion printing.

2.3.2. Laser-Induced Forward Transfer (LIFT)

- Cell Viability: LIFT has been shown to maintain high cell viability due to its non-contact nature and precise energy control.

- Resolution: The technique allows for the deposition of droplets with diameters as small as a few microns, enabling the creation of fine structures and intricate tissue architectures.

- Compatibility: LIFT can accommodate various bioinks, including those containing fragile living cells, making it ideal for cancer models requiring physiological accuracy.

- Thermal Effects: While the energy used in LIFT is finely tuned, excessive laser intensity can generate heat, potentially compromising cell viability.

- Material Transfer Limitations: The uniformity and reproducibility of material transfer depend on the bioink's viscosity and the laser's energy settings.

2.3.3. Laser-Induced Side Transfer (LIST)

2.3.4. Laser-Induced Bubble Printing (LIBP)

3. Opportunities Provided by 3D Bioprinted Cancer Models

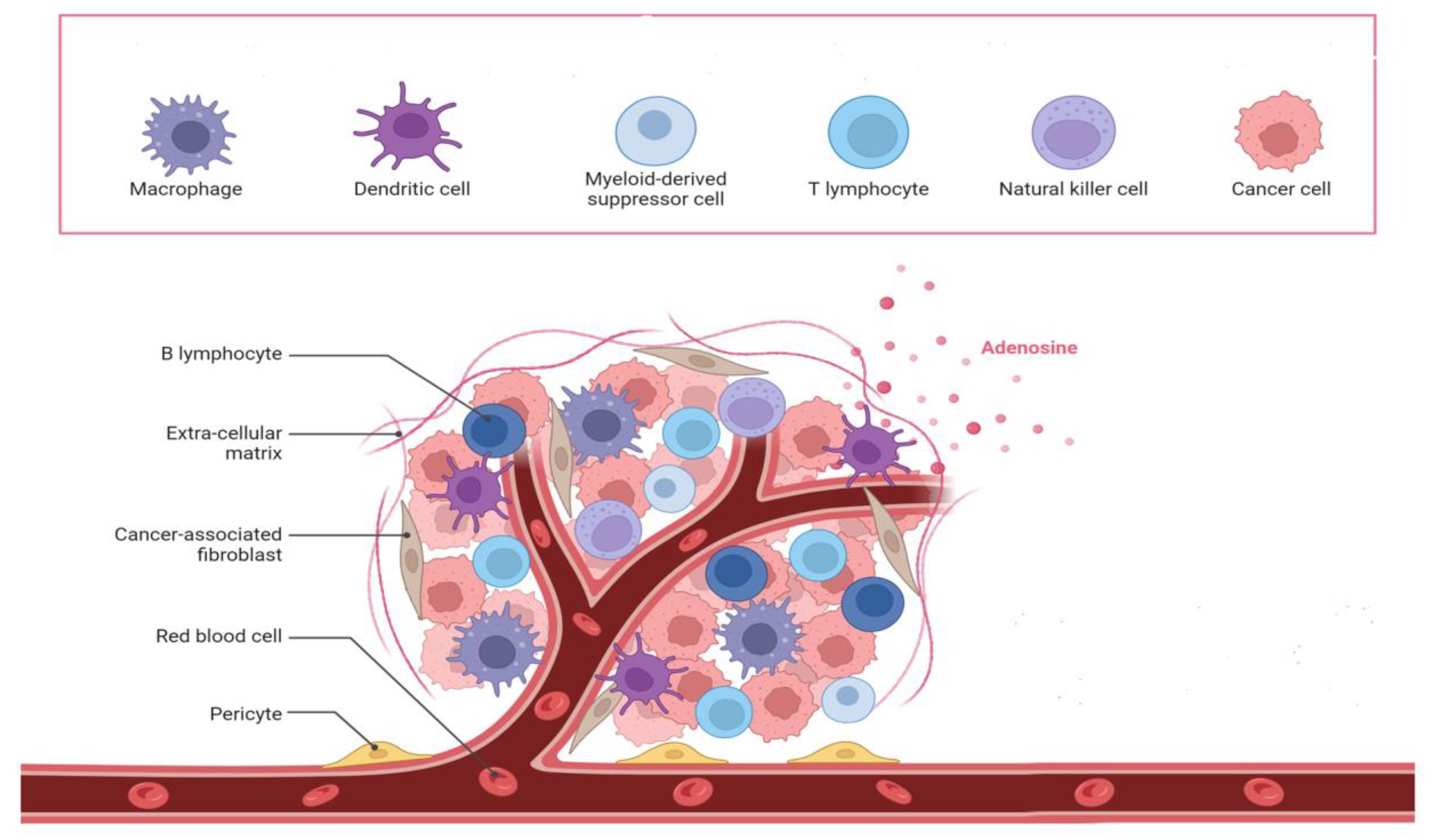

3.1. Tumor Microenvironment Characteristics.

3.1.1. Enhanced Tumor Microenvironment

3.2. Personalized Medicine

3.3. Drug Discovery and Screening

4. Challenges Facing 3D Bioprinted Cancer Models

4.1. Technical Challenges in 3D Bioprinting

4.2. Reproducibility in 3D Bioprinted Cancer Models

4.3. Standardization of Protocols

4.4. Bioink Limitations

4.4.1. Biocompatibility Issues

4.4.2. Mechanical Properties

5. Current Advances and Emerging Solutions

5.1. AI Optimization in Bioprinting

5.2. Hybrid Techniques in Bioprinting

5.3. Microfluidics in Bioprinting

5.4. Advanced Formulations of Bioink

6. Future Prospects and Implications for Cancer Research

7. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kang Y, Datta P, Shanmughapriya S, et al. (2020) 3D Bioprinting of Tumor Models for Cancer Research. ACS Appl Bio Mater. 3(9):5552-5573. [CrossRef]

- Colombo E ,Cattaneo M G (2021) Multicellular 3D Models to Study Tumour-Stroma Interactions. Int J Mol Sci. 22(4). [CrossRef]

- Zimmer J, Castriconi R ,Scaglione S (2021) Editorial: Recent 3D Tumor Models for Testing Immune-Mediated Therapies. Front Immunol. 12:798493. [CrossRef]

- Zhou Y ( 2016) Understanding the cancer/tumor biology from 2D to 3D. J Thorac Dis. 8(11):E1484-E1486. [CrossRef]

- Ren Y, Yang X, Ma Z, et al.(2021) Developments and Opportunities for 3D Bioprinted Organoids. Int J Bioprint. 7(3):364. [CrossRef]

- Stone L (2014) Kidney cancer: A model for the masses--3D printing of kidney tumours. Nat Rev Urol. 11(8): 428. [CrossRef]

- Zhang XY, Zhang YD (2015) Tissue engineering applications of three-dimensional bioprinting. Cell Biochem Biophys. 72(3):777–782. [CrossRef]

- Melchels FPW, Domingos MAN, Klein TJ et al (2012) Additive manufacturing of tissues and organs. Prog Polym Sci. 37(8):1079–1104. [CrossRef]

- Boland T, Xu T, Damon B, Cui X (2006) Application of inkjet printing to tissue engineering. Biotechnol J 1(9):910–917. [CrossRef]

- Calvert P (2007) Printing cells. Science. 318(5848):208–209. [CrossRef]

- Cui X, Booland T, D’Lima DD, Lotz MK (2012) Thermal inkjet printing in tissue engineering and regenerative medicine. Recent Patents Drug Deliv Formul. 6(2):149–155. [CrossRef]

- Sumerel J, Lewis J, Doraiswamy A, Deravi LF, Sewell SL, Gerdon AE, Wright DW, Narayan RJ (2006) Piezoelectric ink jet processing of materials for medical and biological applications. Biotechnol J. 1(9):976–987. [CrossRef]

- Cui XF, Breitenkamp K, Finn MG et al (2012) Direct human cartilage repair using three-dimensional bioprinting technology. Tissue Eng Part A. 18(11–12):1304–1312. [CrossRef]

- Cui XF, Boland T (2009) Human microvasculature fabrication using thermal inkjet printing technology. Biomaterials. 30(31):6221–6227. [CrossRef]

- Weiss LE, Amon CH, Finger S et al (2005) Bayesian computeraided experimental design of heterogeneous scaffolds for tissue engineering. Comput Aided Des. 37(11):1127–1139. [CrossRef]

- Campbell PG, Weiss LE (2007) Tissue engineering with the aid of inkjet printers. Expert Opin Biol Therapy. 7(8):1123–1127.

- Saunders RE, Derby B (2014) Inkjet printing biomaterials for tissue engineering: bioprinting. Int Mater Rev. 59(8):430–448.

- Setti L, Fraleoni-Morgera A, Ballarin B et al (2005) An amperometric glucose biosensor prototype fabricated by thermal inkjet printing. Biosens Bioelectron. 20(10):2019–2026. [CrossRef]

- Chen FM, Lin LY, Zhang J et al (2016) Single-cell analysis using drop-on-demand inkjet printing and probe electrospray ionization mass spectrometry. Anal Chem. 88(8):4354–4360. [CrossRef]

- Ozbolat IT, Yu Y (2013) Bioprinting toward organ fabrication: challenges and future trends. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 60(3):691–699. [CrossRef]

- Kim H, Lee S (2020) Printability and physical properties of iron slag powder composites using material extrusion-based 3D printing. Journal of Iron and Steel Research International. 28 (1): 111–121. [CrossRef]

- Asif M (2018) A new photopolymer extrusion 5-axis 3D printer. Addit. Manuf. 23: 355–361. [CrossRef]

- Liu Q, Zhai W (2022) Hierarchical porous Ceramics with Distinctive microstructures by Emulsion-based direct ink writing. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 14 (28):32196–32205. [CrossRef]

- Qiu J (2021) Constructing customized Multimodal Phantoms through 3D printing: a Preliminary evaluation. Frontiers in Physics. 9. [CrossRef]

- Atakok G, Kam M, Koc HB (2022) Tensile, three-point bending and impact strength of 3D printed parts using PLA and recycled PLA filaments: a statistical investigation. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 18:1542–1554. [CrossRef]

- Chang J, Sun X ( 2023) Laser-induced forward transfer based laser bioprinting in biomedical applications. Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology. 11: 01-11. [CrossRef]

- Al Javed MO, Bin Rashid A ( 2024) Laser-assisted micromachining techniques: an overview of principles, processes, and applications. Advances in Materials and Processing Technologies. 1-44. [CrossRef]

- Garg A, Yang F, Ozdoganlar OB, LeDuc PR (2024) Physics of microscale freeform 3D printing of ice. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 121: p.e2322330121. [CrossRef]

- Tay RY, Song Y, Yao DR, Gao W (2023) Direct-ink-writing 3D-printed bioelectronics. Materials Today. 71: 135-151. [CrossRef]

- Mojdeh M, Hamid R, Fatemeh Y, Abbas R, Francesco B (2024) Advancements in tissue and organ 3D bioprinting: Current techniques, applications, and future perspectives. Materials & Design. 240:112853. [CrossRef]

- Yongcong F, Yuzhi G, Tiankun L, Runze X, Shuangshuang M, Xingwu M, Ting Zh, Liliang O, Zhuo X, Wei S (2022) Advances in 3D Bioprinting. Chinese Journal of Mechanical Engineering: Additive Manufacturing Frontiers 1:100011.

- Young OM, Xu X, Sarker S, Sochol R D (2024) Direct laser writing-enabled 3D printing strategies for microfluidic applications. Lab on a Chip. 24: 2371-2396. [CrossRef]

- Garciamendez-Mijares CE, Aguilar FJ, Hernandez P, Kuang X, Gonzalez M, Ortiz V, Riesgo RA, Ruiz DSR, Rivera VAM, Rodriguez JC, Mestre FL (2024) Design considerations for digital light processing bioprinters. Applied physics reviews. 11:031314. [CrossRef]

- Das A, Ghosh A, Chattopadhyaya S, Ding CF (2024) A review on critical challenges in additive manufacturing via laser-induced forward transfer. Optics & Laser Technology. 168:109893. [CrossRef]

- Marcos F, Pere S (2020) Laser-Induced Forward Transfer: A Method for Printing Functional Inks. Crystals. 10:651. [CrossRef]

- Mierke CT (2024) Bioprinting of Cells, Organoids and Organs-on-a-Chip Together with Hydrogels Improves Structural and Mechanical Cues. Cells. 13:1638. [CrossRef]

- Chang J, Sun X (2023) Laser-induced forward transfer based laser bioprinting in biomedical applications. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 11:1255782. [CrossRef]

- Molpeceres C, Ramos-Medina R, Marquez A (2023) Laser transfer for circulating tumor cell isolation in liquid biopsy. Int J Bioprint, 9: 720. [CrossRef]

- Gabriella NH, Yuchao F, Bertrand V, Antonio I, Andreas D, Claire P, Aude C, Frank P L, Fabien G, Ioannis p (2024) Laser-assisted bioprinting of targeted cartilaginous spheroids for high density bottom-up tissue engineering. Biofabrication. 16:045029. [CrossRef]

- Yang Z (2023) Laser-Induced Forward Transfer of Functional Microdevices.

- Piqué, A, Charipar KM (2021) Laser-induced forward transfer applications in micro-engineering. Handbook of Laser Micro-and Nano-Engineering. [CrossRef]

- Xing F, Xu J, Yu P, Zhou Y, Zhe M, Luo R, Liu M, Xiang Z, Duan X, Ritz U (2023) Recent advances in biofabrication strategies based on bioprinting for vascularized tissue repair and regeneration. Materials & Design. 229:111885. [CrossRef]

- Ventura RD (2021) An overview of laser-assisted bioprinting (LAB) in tissue engineering applications. Medical Lasers; Engineering, Basic Research, and Clinical Application. 10:76-81. [CrossRef]

- Suamte L, Tirkey A, Barman J, Babu PJ (2023) Various manufacturing methods and ideal properties of scaffolds for tissue engineering applications. Smart Materials in Manufacturing. [CrossRef]

- Manshina AA, Tumkin II, Khairullina EM, Mizoshiri M, Ostendorf A, Kulinich SA, Makarov S, Kuchmizhak AA, Gurevich EL (2024) The second laser revolution in chemistry: Emerging laser technologies for precise fabrication of multifunctional nanomaterials and nanostructures. Advanced Functional Materials. 34:2405457. [CrossRef]

- Sota K, Mondal S, Ando K, Uchimoto Y, Nakajima T (2024) Nanosecond laser texturing of Ni electrodes as a high-speed and cost-effective technique for efficient hydrogen evolution reaction. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy. 93: 1218-1226. [CrossRef]

- all GN, Fan Y, Viellerobe B, Iazzolino A, Dimopoulos A, Poiron C, Clapies A, Luyten FP, Guillemot F, Papantoniou I (2024) Laser-assisted bioprinting of targeted cartilaginous spheroids for high density bottom-up tissue engineering. Biofabrication. 16:045029. [CrossRef]

- Erfanian M, Mohammadi A, Orimi HE, Zapata-Farfan J, Saade J, Meunier M, Larrivée B, Boutopoulos C( 2024) Drop-on-demand bioprinting: A redesigned laser-induced side transfer approach with continuous capillary perfusion. International Journal of Bioprinting. 10: 2832.

- Mareev E, Minaev N, Zhigarkov V, Yusupov V (2021) Evolution of Shock-Induced Pressure in Laser Bioprinting. Photonics. 8:374. [CrossRef]

- Qu J, Dou C, Xu B, Li J, Rao Z, Tsin A ( 2021) Printing quality improvement for laser-induced forward transfer bioprinting: Numerical modeling and experimental validation. Physics of Fluids. 33:071906. [CrossRef]

- Wan Z, Liu Z, Zhang Q, Zhang Q, Gu M (2024) aser Technology for Perovskite: Fabrication and Applications. Advanced Materials Technologies. 9: 2302033. [CrossRef]

- Ng W L, Shkolnikov V( 2024) Jetting-based bioprinting: process, dispense physics, and applications. Bio-Design and Manufacturing. 7:771–799. [CrossRef]

- Gundu S, Varshney N, Sahi AK, Mahto SK (2022) Recent developments of biomaterial scaffolds and regenerative approaches for craniomaxillofacial bone tissue engineering. Journal of Polymer Research. 29:73. [CrossRef]

- Aadil KR, Bhange K, Kumar N, Mishra G (2024)Keratin nanofibers in tissue engineering: bridging nature and innovation. Biotechnology for Sustainable Materials. 1: 1-21. [CrossRef]

- Cheng F, Song D, Li H, Ravi SK, Tan SC ( 2025) Recent Progress in Biomedical Scaffold Fabricated via Electrospinning: Design, Fabrication and Tissue Engineering Application. Advanced Functional Materials. 35:2406950. [CrossRef]

- Gruene M, Deiwick A, Koch L, Schlie S (2011) Unger, C.; Hofmann, N.; Bernemann, I.; Glasmacher, B.; Chichkov, B. Laser Printing of Stem Cells for Biofabrication of Scaffold-Free Autologous Grafts. Tissue Eng. Part C Methods.17:79–87. [CrossRef]

- Hakobyan D, Médina C, Dusserre N, Stachowicz ML, Handschin C, Fricain JC, Guillermet-Guibert J, Oliveira H (2020) Laser-assisted 3D bioprinting of exocrine pancreas spheroid models for cancer initiation study. Biofabrication. 12:035001. [CrossRef]

- Sorkio A, Koch L, Koivusalo L, Deiwick A, Miettinen S, Chichkov B, Skottman H (2018) Human stem cell based corneal tissue mimicking structures using laser-assisted 3D bioprinting and functional bioinks. Biomaterials. 171:57–71. [CrossRef]

- Catros S, Fricain JC, Guillotin B, Pippenger B, Bareille R, Remy M, Lebraud E, Desbat B, Amédée J, Guillemot F (2011) Laserassisted bioprinting for creating on-demand patterns of human osteoprogenitor cells and nano-hydroxyapatite. Biofabrication. 3:025001. [CrossRef]

- Michael S, Sorg H, Peck CT, Koch L, Deiwick A, Chichkov B (2013) Vogt, P.M.; Reimers, K. Tissue Engineered Skin Substitutes Created by Laser-Assisted Bioprinting Form Skin-Like Structures in the Dorsal Skin Fold Chamber in Mice. PLoS ONE. 8:e57741. [CrossRef]

- Gruene M, Pflaum M, Deiwick A, Koch L, Schlie S, Unger C, Wilhelmi M, Haverich A, Chichkov B (2011) Adipogenic differentiation of laser-printed 3D tissue grafts consisting of human adipose-derived stem cells. Biofabrication. 3:015005. [CrossRef]

- Nakielski P, Rinoldi C, Pruchniewski M, Pawłowska S, Gazi´ nska M, Strojny B, Rybak D, Jezierska-Wo´zniak K, Urbanek O, Denis P (2021) Laser-Assisted Fabrication of Injectable Nanofibrous Cell Carriers. Small. 18:2104971. [CrossRef]

- Guillotin B, Souquet A, Catros S et al (2010) Laser assisted bioprinting of engineered tissuewith high cell density andmicroscale organization. Biomaterials. 31(28):7250–7256. [CrossRef]

- Koch L, Deiwick A, Schlie S et al (2012) Skin tissue generation by laser cell printing. Biotechnol Bioeng. 109(7):1855–1863. [CrossRef]

- Ali M, Pages E, Ducom A et al (2014) Controlling laser-induced jet formation for bioprinting mesenchymal stem cells with high viability and high resolution. Biofabrication. 6(4):045001. [CrossRef]

- NahmiasY, Schwartz RE,VerfaillieCMet al (2005) Laser-guided direct writing for three-dimensional tissue engineering. Biotechnol Bioeng. 92(2):129–136. [CrossRef]

- Odde DJ, Renn MJ (1999) Laser-guided direct writing for applications in biotechnology. Trends Biotechnol. 17(10):385–389. [CrossRef]

- Wang ZJ, Abdulla R, Parker B et al (2015) A simple and highresolution stereolithography-based 3D bioprinting system using visible light crosslinkable bioinks. Biofabrication. 7(4):045009. [CrossRef]

- Lee W, Debasitis JC, Lee VK et al (2009) Multi-layered culture of human skin fibroblasts and keratinocytes through threedimensional freeform fabrication. Biomaterials 30(8):1587–1595. [CrossRef]

- MinD,LeeW, Bae I-H,Lee TR,Croce P,Yoo S-S (2017) Bioprinting of biomimetic skin containing melanocytes. Exp Dermatol.1–7. [CrossRef]

- Kim BS, Lee JS, Gao G et al (2017) Direct 3D cell-printing of human skin with functional transwell system. Biofabrication. 9(2):025034. [CrossRef]

- Xu F, Celli J, Rizvi I et al (2011) A three-dimensional in vitro ovarian cancer coculture model using a high-throughput cell patterning platform. Biotechnol J. 6(2):204–212. [CrossRef]

- Faulkner-JonesA, FyfeC,CornelissenDJ et al (2015) Bioprinting of human pluripotent stem cells and their directed differentiation into hepatocyte-like cells for the generation of mini-livers in 3D. Biofabrication. 7(4):044102. [CrossRef]

- Ávila HM, Schwarz S, Rotter N, Gatenholma P (2016) 3D bioprinting of human chondrocyte-laden nanocellulose hydrogels for patient-specific auricular cartilage regeneration. Bioprinting. 1–2:22–35. [CrossRef]

- Lee JS, Hong JM, Jung JW et al (2014) 3D printing of composite tissue with complex shape applied to ear regeneration. Biofabrication. 6(2):1–12. [CrossRef]

- Muller M, Ozturk E, Arlov O et al (2017) Alginate sulfatenanocellulose bioinks for cartilage bioprinting applications. Ann Biomed Eng. 45(1):210–223. [CrossRef]

- 34. Huang S, Yao B, Xie JF et al (2016) 3D bioprinted extracellular matrix mimics facilitate directed differentiation of epithelial progenitors for sweat gland regeneration. Acta Biomater. 32:170–177. [CrossRef]

- GaoQ, LiuZ,Lin Z, Qiu J,LiuY, LiuA,WangY,XiangM, Chen B, Fu J, He Y (2017) 3D bioprinting of vessel-like structures with multilevel fluidic channels. ACS Biomater Sci Eng. 3(3):399–408. [CrossRef]

- Ozbolat IT,ChenH,YuY(2014) Development of ’Multi-arm Bioprinter’ for hybrid biofabrication of tissue engineering constructs. Robot Comput Integr Manuf. 30(3):295–304. [CrossRef]

- Zhang B, Gao L, Gu L, Yang H, Luo Y, Ma L (2017) Highresolution 3D bioprinting system for fabricating cell-laden hydrogel scaffolds with high cellular activities. Procedia Cirp. 65:219–224. [CrossRef]

- Khalil S, Nam J, Sun W (2005) Multi-nozzle deposition for construction of 3D biopolymer tissue scaffolds. Rapid Prototyp J. 11(1):9–17. [CrossRef]

- Kang HW, Lee SJ, Ko IK et al (2016) A 3D bioprinting system to produce human-scale tissue constructs with structural integrity. Nat Biotechnol. 34(3):312–319. [CrossRef]

- Dilip K C, Rui LR, Subhas CK, Awanish K, Chinmaya M (2024) Nanomaterials-Based Hybrid Bioink Platforms in Advancing 3D Bioprinting Technologies for Regenerative Medicine. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 10(7):4145–4174. [CrossRef]

- Hao W, Wang Z, Dimitra L, Haoyi Y, Darius G, Hongtao W, Cheng-Feng P, Parvathi Nair Suseela N, Yujie K, Tomohiro M, John You En Ch, Qifeng R, Maria F, Mangirdas M, Saulius J, Min G, Joel K W Y (2023) Two-Photon Polymerization Lithography for Optics and Photonics: Fundamentals, Materials, Technologies, and Applications. ADVANCED FUNCTIONAL MATERILAS.33:2214211. [CrossRef]

- Hyunmin Ch, Won-Sup L, Won Seok Ch (2024) Three-dimensional photopolymerization additive manufacturing technology based on two-photon polymerization. JMST Advances. 6:371-377. [CrossRef]

- Balkwill FR, Capasso M, Hagemann T (2012) The Tumor Microenvironment at a Glance. J. Cell Sci. 125 (23):5591−5596. [CrossRef]

- Kerkar SP, Restifo NP (2012) Cellular Constituents of Immune Escape within the Tumor Microenvironment. Cancer Res. 72(13):3125−3130. [CrossRef]

- Baghban R, Roshangar L, Jahanban-Esfahlan R, Seidi K, Ebrahimi-Kalan A, Jaymand M, Kolahian S, Javaheri T, Zare P (2020)Tumor Microenvironment Complexity and Therapeutic Implications at a Glance. Cell Commun. Signaling.18 (1): 1−19. [CrossRef]

- Jin Y, Ai J, Shi J (2015) Lung Microenvironment Promotes the Metastasis of Human Hepatocellular Carcinoma Cells to the Lungs. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Med.8 (6): 9911−9917.

- Iwahori K (2020) Cytotoxic CD8+ Lymphocytes in the Tumor Microenvironment. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol.1224: 53−62. [CrossRef]

- Maimela NR, Liu S, Zhang Y (2019) Fates of CD8+ T Cells in Tumor Microenvironment. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J.17:1−13. [CrossRef]

- Sharonov GV, Serebrovskaya EO, Yuzhakova DV, Britanova OV, Chudakov DM (2020) B Cells, Plasma Cells and Antibody Repertoires in the Tumour Microenvironment. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 20 (5): 294−307. [CrossRef]

- Wang S, Liu W, Ly D, Xu H, Qu L, Zhang L (2019) Tumor-Infiltrating B Cells: Their Role and Application in Anti-Tumor Immunity in Lung Cancer. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 16 (1): 6−18. [CrossRef]

- Larsen SK, Gao Y, Basse PH (2014) NK Cells in the Tumor Microenvironment. Crit. Rev. Oncog. 19 (1-2): 91−105.

- Liao Z, Tan ZW, Zhu P, Tan NS (2019) Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts in Tumor Microenvironment − Accomplices in Tumor Malignancy. Cell. Immunol. 343:103729. [CrossRef]

- Monteran L, Erez N (2019) The Dark Side of Fibroblasts: Cancer- Associated Fibroblasts as Mediators of Immunosuppression in the Tumor Microenvironment. Front. Immunol.10:1−15. [CrossRef]

- Chouaib S, Kieda C, Benlalam H, Noman MZ, Mami-Chouaib F, Rüegg C (2010) Endothelial Cells as Key Determinants of the Tumor Microenvironment: Interaction with Tumor Cells, Extracellular Matrix and Immune Killer Cells. Crit. Rev. Immunol. 30(6):529−545.

- Walker C, Mojares E, Del Río Hernández A (2018) Role of Extracellular Matrix in Development and Cancer Progression. Int. J. Mol. Sci.19 (10):3028. [CrossRef]

- Padhi A, Nain AS (2020) ECM in Differentiation: A Review of Matrix Structure, Composition and Mechanical Properties. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 48 (3):1071−1089. [CrossRef]

- Mierke CT (2019) The Matrix Environmental and Cell Mechanical Properties Regulate Cell Migration and Contribute to the Invasive Phenotype of Cancer Cells. Rep. Prog. Phys. 82 (6): 064602. [CrossRef]

- Fischer T, Wilharm N, Hayn A, Mierke CT (2017) Matrix and Cellular Mechanical Properties Are the Driving Factors for Facilitating Human Cancer Cell Motility into 3D Engineered Matrices. Converg. Sci. Phys. Oncol. 3 (4): 044003. [CrossRef]

- Pathak A, Kumar S (2012) Independent Regulation of Tumor Cell Migration by Matrix Stiffness and Confinement. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A.109 (26) :10334−10339. [CrossRef]

- Whiteside TL (2008) The tumor microenvironment and its role in promoting tumor growth. Oncogene. 27:5904–5912. [CrossRef]

- Wang X, Li X, Ding J, Long X, Zhang H, Zhang X, Jiang X, Xu T (2021) 3D bioprinted glioma microenvironment for glioma vascularization. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part A.109: 915–925. [CrossRef]

- Chen K, Jiang E, Wei X, Xia Y, Wu Z, Gong Z, Shang Z, Guo S (2021) The acoustic droplet printing of functional tumor microenvironments. Lab Chip. 21:1604–1612.

- Liu Y, Liu Y, Zheng X, Zhao L, Zhang X (2020) Recapitulating and Deciphering Tumor Microenvironment by Using 3D Printed Plastic Brick–Like Microfluidic Cell Patterning. Adv. Health Mater.9:e1901713. [CrossRef]

- Duan J, Cao Y, Shen Z, Cheng Y, Ma Z, Wang L, Zhang Y, An Y, Sang S(2022) 3D Bioprinted GelMA/PEGDA Hybrid Scaffold for Establishing an In Vitro Model of Melanoma. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 32:531–540. [CrossRef]

- Jiang T, Munguia-Lopez J, Flores-Torres S, Grant J, Vijayakumar S, De Leon-Rodriguez A, Kinsella, JM (2018) Bioprintable Alginate/Gelatin Hydrogel 3D In Vitro Model Systems Induce Cell Spheroid Formation. J. Vis. Exp.137:e57826. [CrossRef]

- Kim J, Jang J, Cho DW (2021) Controlling Cancer Cell Behavior by Improving the Stiffness of Gastric Tissue-Decellularized ECM Bioink With Cellulose Nanoparticles. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 9: 605819. [CrossRef]

- Aveic S, Janßen S, Nasehi R, Seidelmann M, Vogt M, Pantile M, Rütten S, Fischer H (2021) A 3D printed in vitro bone model for the assessment of molecular and cellular cues in metastatic neuroblastoma. Biomater. Sci. 9:1716–1727.

- Lv K, Zhu J, Zheng S, Jiao Z, Nie Y, Song F, Liu T, Song K (2021) Evaluation of inhibitory effects of geniposide on a tumor model of human breast cancer based on 3D printed Cs/Gel hybrid scaffold. Mater. Sci. Eng. C Mater. Biol. Appl. 119:111509. [CrossRef]

- Vanderburgh J, Sterling JA, Guelcher SA (2017) 3D Printing of Tissue Engineered Constructs for In Vitro Modeling of Disease Progression and Drug Screening. Ann. Biomed Eng. 45:164–179. [CrossRef]

- Chen Y, Bian L, Zhou H, Wu D, Xu J, Gu C, Fan X, Liu Z, Zou J, Xia J (2020) Usefulness of three-dimensional printing of superior mesenteric vessels in right hemicolon cancer surgery. Sci. Rep. 10:11660. [CrossRef]

- Park JW, Kang HG, Kim JH, Kim HS (2021) The application of 3D-printing technology in pelvic bone tumor surgery. J. Orthop. Sci. 26:276–283. [CrossRef]

- Zeng N, Yang J, Xiang N, Wen S, Zeng S, Qi S, Zhu W, Hu H, Fang C (2020) Application of 3D visualization and 3D printing in individualized precision surgery for Bismuth-Corlette type III and IV hilar cholangiocarcinoma. Nan Fang Yi Ke Da XueXue Bao. 40:1172–1177, (In Chinese).

- Huang X, Liu Z, Wang X, Li XD, Cheng K, Zhou Y, Jiang XB (2019) A small 3D printing model of macroadenomas for endoscopic endonasal surgery. Pituitary. 22: 46–53. [CrossRef]

- Emile SH, Wexner SD (2019) Systematic review of the applications of three-dimensional printing in colorectal surgery. Color. Dis. 21:261–269. [CrossRef]

- Hong D, Lee S, Kim T, Baek JH, Kim WW, Chung KW, Kim N, Sung TY (2020) Usefulness of a 3D-Printed Thyroid Cancer Phantom for Clinician to Patient Communication. World J. Surg. 44:788–794. [CrossRef]

- Burdall OC, Makin E, Davenport M, Ade-Ajayi N (2016) 3D printing to simulate laparoscopic choledochal surgery. J. Pediatric Surg. 51: 828–831. [CrossRef]

- Smelt JL, Suri T, Valencia O, Jahangiri M, Rhode K, Nair A, Bille A (2019) Operative Planning in Thoracic Surgery: A Pilot Study Comparing Imaging Techniques and Three-Dimensional Printing. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 107: 401–406. [CrossRef]

- Wang L, Wang H, Jiang Y, Ji Z, Guo F, Jiang P, Li X, Chen Y, Sun H, Fan J (2020) The efficacy and dosimetry analysis of CT-guided 125I seed implantation assisted with 3D-printing non-co-planar template in locally recurrent rectal cancer. Radiat. Oncol. 15:179. [CrossRef]

- Yoon SH, Park S, Kang CH, Park IK, Goo JM, Kim YT (2019) Personalized 3D-Printed Model for Informed Consent for Stage I Lung Cancer: A Randomized Pilot Trial. Semin. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 31:316–318. [CrossRef]

- Shen Z, Xie Y, Shang X, Xiong G, Chen S, Yao Y, Pan Z, Pan H, Dong X, Li Y (2020) The manufacturing procedure of 3D printed models for endoscopic endonasal transsphenoidal pituitary surgery. Technol. Health Care. 28:131–150.

- Chen Y, Zhang J, Chen Q, Li T, Chen K, Yu Q, Lin X (2020) Three-dimensional printing technology for localised thoracoscopic segmental resection for lung cancer: A quasi-randomised clinical trial. World J. Surg. Oncol. 18: 223. [CrossRef]

- Lan Q, Zhu Q, Xu L, Xu T (2020) Application of 3D-Printed Craniocerebral Model in Simulated Surgery for Complex Intracranial Lesions. World Neurosurg. 134:e761–e770. [CrossRef]

- Wang L, Cao T, Li X. Huang L (2016) Three-dimensional printing titanium ribs for complex reconstruction after extensive posterolateral chest wall resection in lung cancer. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 152: e5–e7.

- Valente KP, Khetani S, Kolahchi AR, Sanati-Nezhad A, Suleman A, Akbari M (2017) Microfluidic technologies for anticancer drug studies. Drug Discov. Today. 22:1654–1670. [CrossRef]

- Serrano DR, Terres MC, Lalatsa A (2018) Applications of 3D printing in cancer. J. 3D Print. Med. 2:115–127. [CrossRef]

- Marei I, Abu Samaan T, Al-Quradaghi MA, Farah AA, Mahmud SH, Ding H and Triggle CR (2022) 3D Tissue-Engineered Vascular Drug Screening Platforms: Promise and Considerations. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 9:847554. [CrossRef]

- Chen X, Chen H, Wu D, Chen Q, Zhou Z, Zhang R, Peng X, Su YC, Sun D (2018) 3D printed microfluidic chip for multiple anticancer drug combinations. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 276: 507–516. [CrossRef]

- Zhao X, Du S, Chai LM, Xu Y, Liu L, Zhou X, Wang J, Zhang W, Liu CH, Wang X (2015) Anti-cancer drug screening based on a adipose-derived stem cell/hepatocyte 3D printing technique. J. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 5:273.

- J.Gonzalez-Barahona JM, Robles G (2023) Revisiting the reproducibility of empirical software engineering studies based on data retrieved from development repositories. Information and Software Technology. 164: 107318. [CrossRef]

- Moreau D, Wiebels K, Boettiger C (2023) Containers for computational reproducibility .Nature Reviews Methods Primers. 3:50. [CrossRef]

- Ding Y, DeSarbo WS, Hanssens DM, Jedidi K (2020) The past, present, and future of measurement and methods in marketing analysi. Marketing Letters. 31:175–186. [CrossRef]

- Dong Y, Zhou X, Ding Y, Luo Y, Zhao H (2024) Advances in tumor microenvironment: applications and challenges of 3D bioprinting," Biochemical and Biophysical. 730:150339. [CrossRef]

- Zeng Y, Hao D, Huete A, Dechant B, Berry J (2022) Optical vegetation indices for monitoring terrestrial ecosystems globally. Earth & Environment. 3:477–493. [CrossRef]

- Catacutan DB, Alexander J, Arnold A (2024) Machine learning in preclinical drug discovery. Nature Chemical. 20:960–973. [CrossRef]

- Ren F, Aliper A, Chen J, Zhao H, Rao S, Kuppe C (2024) A small-molecule TNIK inhibitor targets fibrosis in preclinical and clinical models. Nature. [CrossRef]

- Vergis N, Patel V, Bogdanowicz K (2024) IL-1 Signal Inhibition in Alcohol-Related Hepatitis: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial of Canakinumab. Clinical. [CrossRef]

- Sztankovics D, Moldvai D, Petővári G, Gelencsér R, Krencz I, Raffay R, Dankó T, Sebestyén A (2023), 3D bioprinting and the revolution in experimental cancer model systems—A review of developing new models and experiences with in vitro 3D bioprinted breast cancer tissuemimetic structures. Pathol. Oncol. Res. 29:1610996. [CrossRef]

- Wang X, Yang X, Liu X, Shen Z, Li M, Cheng R, Zhao L (2024) 3D bioprinting of an in vitro hepatoma microenvironment model: establishment, evaluation, and anticancer drug testing. Acta Biomaterialia. 185: 173-189. [CrossRef]

- Gogoi D, Kumar M, Singh J (2024) A comprehensive review on hydrogel-based bio-ink development for tissue engineering scaffolds using 3D printing. Annals of 3D Printed Medicine. 15: 100159. [CrossRef]

- Bini F, D’Alessandro S, Agarwal T (2023) Biomimetic 3D bioprinting approaches to engineer the tumor microenvironment. Int J Bioprint. 9(6): 1022. [CrossRef]

- Himanshu T, Sandeep MS, Avanish SP, Shilpi Ch (2022) Hydrogel based 3D printing: Bio ink for tissue engineering. Journal of Molecular Liquids. 367:120390. [CrossRef]

- Guan X, Fei Z, Wang L, Ji G (2025) Engineered streaky pork by 3D co-printing and co-differentiation of muscle and fat cells. Food Hydrocolloids. 158:110578. [CrossRef]

- Pereira I, Lopez-Martinez MJ, Villasante A, Introna C, Tornero D, Canals JM and Samitier J (2023), Hyaluronic acid-based bioink improves the differentiation and network formation of neural progenitor cells. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 11:1110547. [CrossRef]

- Rahman TT, Wood N, Akib YM, Qin H (2024) Experimental Study on Compatibility of Human Bronchial Epithelial Cells in Collagen–Alginate Bioink for 3D Printing. Bioengineering. 11(9): 862. [CrossRef]

- Wei Q, An Y, Zhao X, Li M, Zhang J (2024) Three-dimensional bioprinting of tissue-engineered skin: Biomaterials, fabrication techniques, challenging difficulties, and future directions: A review. International Journal of Biological. 266: 131281. [CrossRef]

- Wang J, Cui Z, Maniruzzaman M (2023) Bioprinting: a focus on improving bioink printability and cell performance based on different process parameters. International journal of pharmaceutics. 640:123020. [CrossRef]

- Zhang H, Wang Y, Zheng Z, Wei X, Chen L, Wu Y (2023) Strategies for improving the 3D printability of decellularized extracellular matrix bioink. Theranostics.13 (8):2562–2587. [CrossRef]

- Morenikeji A, Fabien B, Romain S, Noelia MS, Sylvie B, Ian S, Martial S (2024) Evaluation of the printability of agar and hydroxypropyl methylcellulose gels as gummy formulations: Insights from rheological properties. International Journal of Pharmaceutics. 654:123937. [CrossRef]

- Lee SC, Gillispie G, Prim P, Lee SJ (2020) Physical and chemical factors influencing the printability of hydrogel-based extrusion bioinks. Chemical reviews. 120(19):10834–10886. [CrossRef]

- Uroz M, Stoddard AE, Sutherland BP, Courbot O (2024) Differential stiffness between brain vasculature and parenchyma promotes metastatic infiltration through vessel co-option. Nature Cell. [CrossRef]

- Link R, Weißenbruch K, Tanaka M (2024) Cell shape and forces in elastic and structured environments: from single cells to organoids. Advanced Functional. 34: 2302145. [CrossRef]

- Mao H, Yang L, Zhu H, Wu L, Ji P, Yang J (2020) Recent advances and challenges in materials for 3D bioprinting. Progress in Natural, Elsevier. 30(5):618-634. [CrossRef]

- Murphy SV, De Coppi P, Atala A (2020) Opportunities and challenges of translational 3D bioprinting. Nature biomedical engineering. 4:370–380. [CrossRef]

- Levato R, Jungst T, Scheuring RG, Blunk T (2020) From shape to function: the next step in bioprinting. Advanced. 32(12):1906423. [CrossRef]

- Phung LX, Ta TQ, Pham VH, Nguyen MTH, Do T (2024) The development of a modular and open-source multi-head 3D bioprinter for fabricating complex structures. Bioprinting. 39:e00339. [CrossRef]

- Hwang DG, Choi H, Yong U, Kim D, Kang W (2024) Bioprinting-assisted Tissue Assembly for Structural and Functional Modulation of Engineered Heart Tissue Mimicking Left Ventricular Myocardial Fiber Orientation. Advanced. 36(34):2400364. [CrossRef]

- De Spirito M, Palmieri V, Perini G, Papi M (2024) Bridging the gap: integrating 3D bioprinting and microfluidics for advanced multi-organ models in biomedical research. Bioengineering.11 (7):664. [CrossRef]

- Rathnayaka M, Karunasinghe D, Gunasekara C (2024) Machine learning approaches to predict compressive strength of fly ash-based geopolymer concrete: A comprehensive review. Construction and Building Materials. 419:135519. [CrossRef]

- Ramesh S, Deep A, Tamayol A, Kamaraj A, Mahajan C (2024) Advancing 3D bioprinting through machine learning and artificial intelligence. Bioprinting 38:E00331. [CrossRef]

- Levato R, Dudaryeva O (2023) Light-based vat-polymerization bioprinting. Nature Reviews.47. [CrossRef]

- Makode S, Maurya S, Niknam SA (2024) Three dimensional (bio) printing of blood vessels: from vascularized tissues to functional arteries. 16(2):022005. [CrossRef]

- Bercea M (2023) Rheology as a tool for fine-tuning the properties of printable bioinspired gels. Molecules. 28(6):2766. [CrossRef]

- Niculescu AG, Chircov C, Bîrc˘a AC, Grumezescu AM (2021) Fabrication and Applications of Microfluidic Devices: A Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22: 2011. [CrossRef]

- Ferreira M, Carvalho V, Ribeiro J, Lima RA, Teixeira S (2024) Advances in Microfluidic Systems and Numerical Modeling in Biomedical Applications: A Review. Micromachines. 15(7):873. [CrossRef]

- Taghizadeh M, Taghizadeh A, Yazdi MK, Zarrintaj P (2022) Chitosan-based inks for 3D printing and bioprinting. Green. 24: 62-101. [CrossRef]

- Fatimi A, Okoro OV, Podstawczyk D, Siminska-Stanny J (2022) Natural hydrogel-based bio-inks for 3D bioprinting in tissue engineering: a review. Gels.8(3):179. [CrossRef]

- Satchanska G, Davidova S, Petrov PD (2024) Ntural and Synthetic Polymers for Biomedical and Environmental Applications. Polymers. 16:1159. [CrossRef]

- Benwood C, Chrenek J, Kirsch RL, Masri NZ (2021) Natural biomaterials and their use as bioinks for printing tissues. Bioengineering. 8(2):27. [CrossRef]

- Sánchez DH, Comtois-Bona M, Muñoz M, Ruel M (2024) Manufacturing and validation of small-diameter vascular grafts: A mini review. Iscience. 27:109845. [CrossRef]

- Arulmozhivarman JC, Rajeshkumar L (2024) Synthetic fibers and their composites for biomedical applications. Synthetic and Mineral, Elsevier. 495-511. [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty J, Mu X, Pramanick A, Kaplan DL (2022) Recent advances in bioprinting using silk protein-based bioinks. Biomaterials. 287:121672. [CrossRef]

- Matai I, Kaur G, Seyedsalehi A, McClinton A (2020) Progress in 3D bioprinting technology for tissue/organ regenerative engineering. Biomaterials. 226:119536. [CrossRef]

- Mirshafiei M, Rashedi H, Yazdian F, Rahdar A (2024) Advancements in tissue and organ 3D bioprinting: Current techniques, applications, and future perspectives. Materials & Design. 240:112853. [CrossRef]

- Lee SJ, Jeong W, Atala A (2024) 3D Bioprinting for Engineered Tissue Constructs and Patient-Specific Models: Current Progress and Prospects in Clinical Applications. Advanced Materials. 2408032. [CrossRef]

| Print methods | Bioinks | Resolution | Material Deposition rate | Suitability | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Laser-assisted printing |

Fibrinogen, collagen, GelMA |

1–50μm | High | High-resolution skin, vessel, and tumor models. | [63,64,65,66,67,68] |

|

Inkjet printing |

Collagen, poly(ethylene glycol) dimethacrylate (PEGDMA), fibrinogen, alginate, GelMA |

50–500μm | Medium | Medium-resolution structures; drug testing. | [13,69,70,71,72,73] |

|

Extrusion printing |

Gelatin, polycaprolactone (PCL), polyethylene glycol (PEG), alginate, hyaluronic acid (HA), polyamide(PA), polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) dECM, nanocellulose |

>50μm | Low | Large-scale tissue scaffolds. | [74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83] |

| Photopolymerization | Photosensitive Hydrogels | Sub-1 µm (TPP/DLP) | Medium to High | High-resolution, cell-laden tumor and organ-on-chip models. | [84,85] |

| Method | Advantages | Disadvantages | Latest Developments (2025) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inkjet Printing | High efficiency; low cost; compatible with multi-material printing. | Limited viscosity of bioinks; potential cell damage from droplet ejection. | Advances in nozzle designs to reduce shear stress on cells. |

| Extrusion Printing | Affordable; wide range of bioink viscosities; high cell density deposition. | Low resolution; slower for complex structures; limited material types. | Multi-material extrusion allowing for gradient tissue constructs. |

| Laser-Assisted Printing | High precision; non-contact printing; adaptable for living cells. | Equipment cost; challenges with scalability; potential thermal effects. | LIFT techniques now employ hydrogel coatings instead of metal layers. |

| Photopolymerization (TPP/DLP) | Exceptional resolution (sub-micron); suitable for creating intricate structures. | Limited to photosensitive materials; potential phototoxicity. | Expanded use of biocompatible photoinitiators for living cell encapsulation. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).