1. Introduction

Social media and algorithmic technologies have transformed modern communication, information sharing, and social interactions. However, as these technologies have become deeply embedded in our daily lives, researchers have begun to uncover a darker side to their widespread adoption.

A growing body of evidence suggests that the pervasive use of social media and exposure to algorithmic curation can have profound negative impacts on mental health, fuelling depression, anxiety, and the propagation of harmful ideologies [

1]. The social media context, with its distinct affordances and lack of salient cues for the epistemic quality of content, can make people particularly susceptible to the influence of false claims and misinformation [

2].

The spread of misinformation by social bots and the virality of low-quality information online pose a severe threat, with real-world consequences ranging from dangerous health decisions to manipulations of financial markets [

3]. Paradoxically, the platforms envisioned as modern public squares have become breeding grounds for manipulation, astroturfing, trolling, and impersonation [

4].

Researchers have highlighted the complex interplay of socio-cognitive, ideological, and algorithmic biases that enable these manipulative practices. These practices exploit and exacerbate our innate vulnerabilities to misleading information [

3,

4].

As we grapple with these emerging challenges, we must scrutinise the hidden costs of relying on social media and algorithmic technologies and develop strategies and policies that promote these powerful tools’ responsible and ethical use.

While the benefits of social media and algorithmic technologies are undeniable, the growing body of research calls for a more nuanced understanding of their potential harms. Policymakers, tech companies, and the public must collaborate to address these issues and ensure that the digital landscape remains a space for genuine, productive discourse and decision-making.

The ongoing debate surrounding the ethical implications of technological advancements presents a multifaceted issue that necessitates a comprehensive examination. Adopting a balanced approach to consider these technologies and potential drawbacks is vital. Furthermore, an in-depth analysis of the underlying factors contributing to these developments and the key stakeholders involved is essential. In this context, it is imperative to scrutinise the technology design and the prevailing business model to ascertain their roles and responsibilities in shaping the ethical usage of these innovative services. Therefore, the primary objective of this paper is to illuminate the intricate dynamics of this discourse.

We also discuss algorithmic technology and social media companies’ business models and strategies, which are often driven by the pursuit of user engagement and data extraction for targeted advertising. This profit-centric orientation can lead to prioritising engagement over responsible content curation, amplifying sensitive curation-leading information. Furthermore, the algorithmic design of social media platforms can facilitate the spread of misinformation and manipulative narratives, undermining informed decision-making and threatening the integrity of democratic processes.

2. The Intersection of Technology, Misinformation, and Mental Health

The rapid evolution of technology and the omnipresence of social media platforms have fundamentally transformed how we communicate, access information, and perceive the world around us. While these advancements have brought numerous benefits, such as instant connectivity, vast information resources, and innovative ways to share experiences, they have also introduced a series of hidden costs that are increasingly coming to light. The pervasive use of social media has led to a phenomenon known as the "social dilemma," where individuals find themselves trapped in a cycle of constant social comparison, validation-seeking, and addiction to the instant gratification provided by these platforms [

5].

This displaced behaviour theory suggests that when individuals cannot cope healthily with stress or negative emotions, they may turn to social media for temporary relief, ultimately damaging their mental well-being [

6].

The intersection of technology and social media has raised significant concerns regarding mental health, as studies have shown correlations between excessive social media use and issues such as anxiety, depression, and loneliness [

6]. The pressure to present a curated, idealised version of oneself online can exacerbate feelings of inadequacy and lead to harmful comparisons.

Furthermore, the design of social media platforms—characterised by infinite scrolling, notification-driven engagement, and algorithmically curated content—can disrupt healthy behaviours and contribute to a "displayed behaviour” phenomenon. This occurs when individuals participate in instant gratification activities that diminish their long-term well-being [

6].

Beyond the mental health implications, the rapid dissemination of misinformation and the use of manipulation tactics on social media platforms pose a significant threat to the integrity of public discourse and democratic decision-making. The combination of social media sites, the proliferation of social bots, and human susceptibility to emotional appeals and cognitive biases create a perfect storm for spreading false claims, conspiracy theories, and politically motivated narratives [

3,

7].

These dynamics can undermine trust in institutions, fragment worldviews, and hinder our ability to reach consensus on critical public issues. As the digital landscape becomes increasingly complex, we must address these challenges head-on to safeguard individual well-being and preserve the integrity of our social and political systems.

Policymakers, technology companies, and the public must collaborate to develop comprehensive strategies to mitigate the harmful effects of social media and algorithmic technologies. This may involve enhanced regulation, greater transparency, and the implementation of ethical design principles that prioritise user well-being over engagement and profit [

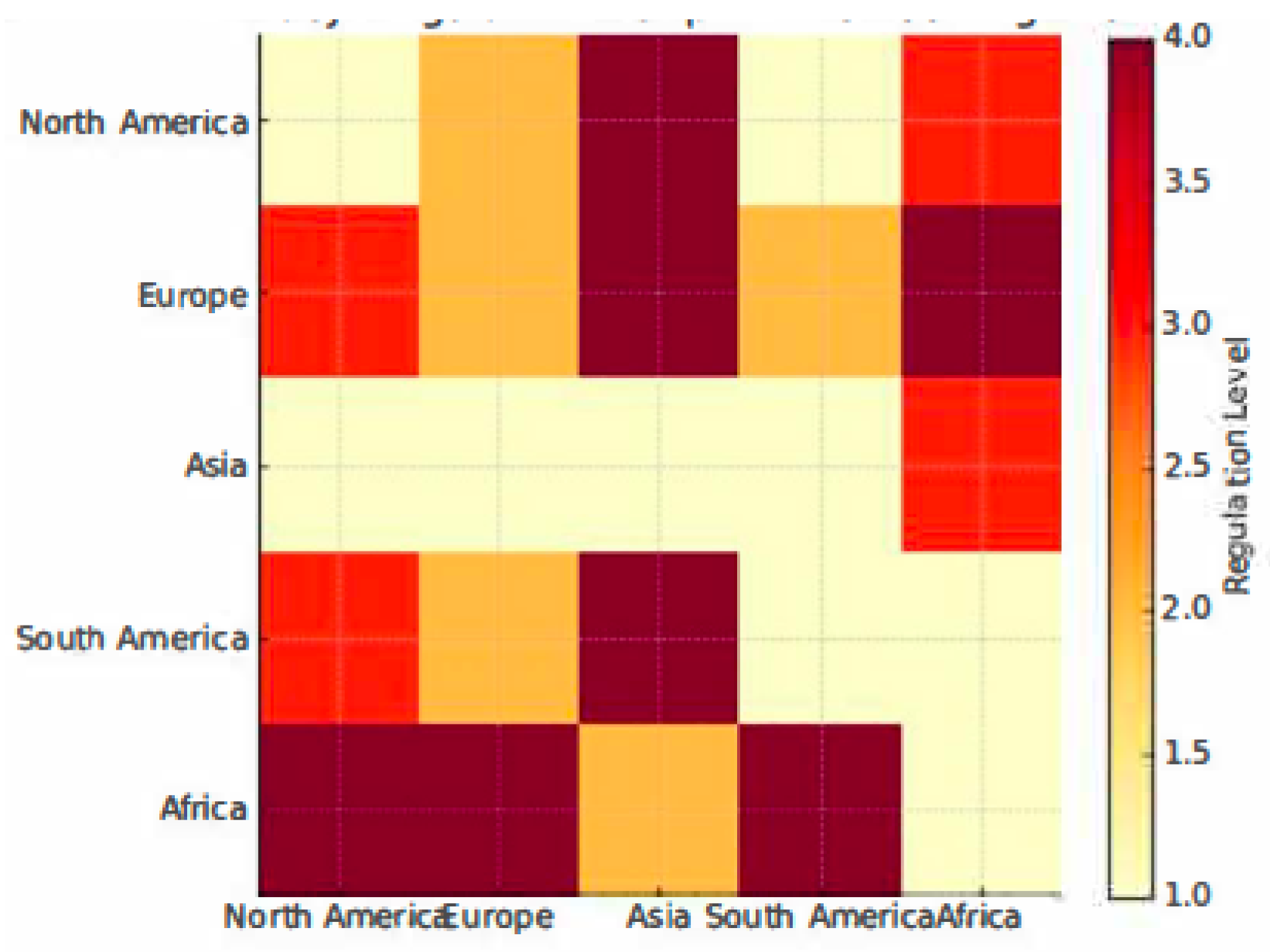

7]. Privacy regulations vary significantly across regions (

Figure 1), with some jurisdictions implementing stricter data protection laws than others. The disparity in enforcement underscores the need for global cooperation in safeguarding user rights.

By recognising social media’s hidden costs and mediating them proactively, we can harness these technologies’ positive potential while minimising their detrimental impact on mental health, social cohesion, and democratic discourse.

Additionally, the ease with which misinformation can spread on social media platforms seriously threatens public discourse and democracy. False information, conspiracy theories, and fake news can increase rapidly, often outpacing factual content and leading to widespread confusion and division [

8,

9].

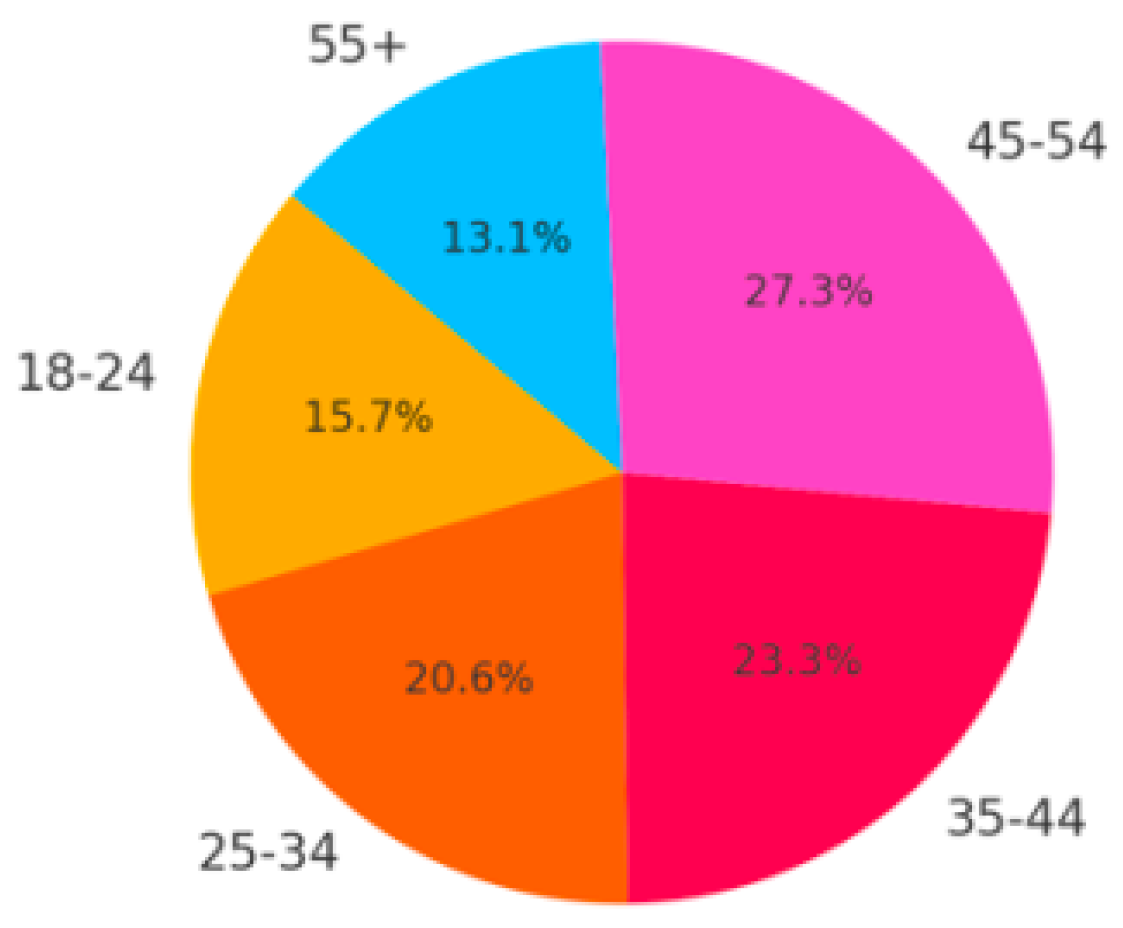

Demographics engaging with conspiracy content often span diverse age groups, socio-economic backgrounds, and education levels, though certain patterns emerge. Studies suggest younger adults, particularly those active on social media, are more likely to encounter and share conspiracy content due to algorithmic recommendations and online echo chambers. Individuals with lower levels of trust in authority, higher susceptibility to cognitive biases, or feelings of marginalisation are more likely to engage with such material. Additionally, times of societal uncertainty, such as during pandemics or political crises, often see a surge in conspiracy belief among people seeking to make sense of complex or threatening events. As depicted in

Figure 2, the distribution of demographics engaging with conspiracy content highlights that individuals aged 45-54 show the highest engagement levels, followed by the 35-44 age group. This pattern may be attributed to the increased likelihood of exposure to misinformation through social media, algorithmic recommendation systems, and pre-existing cognitive biases. Younger demographics, while also active online, demonstrate slightly lower engagement, potentially due to a more critical approach to digital content. However, during times of societal uncertainty, such as pandemics or political instability, engagement across all age groups tends to increase.

This dynamic can undermine trust in institutions, fuel extremism, and make reaching consensus on critical public issues increasingly tricky. Addressing this challenge requires a multifaceted approach that combines technological solutions, enhanced regulation, and a renewed emphasis on media literacy and critical thinking skills. Technology companies must take greater responsibility for the content and behaviours on their platforms, deploying algorithms and content moderation practices that prioritise truth and authenticity over engagement and profitability [

10]. Manipulative practices employed by tech companies to maximise user engagement also come under scrutiny. Algorithms designed to keep users hooked can exploit psychological vulnerabilities, creating addictive behaviours and reducing the quality of online interactions. Understanding these hidden costs is crucial for developing strategies to mitigate the negative impacts of technology and social media, ensuring that these powerful tools can enhance rather than detract from our well-being and societal cohesion. In the face of increasing criticism, major technology corporations have continued to expand their influence. The technology industry is currently facing increased scrutiny, with recent studies highlighting the connection between mental health and social media usage. This research suggests a concerning trend of excessive dependence on electronic devices, enabling individuals to isolate themselves from the outside world. Consequently, this amplified reliance on technology poses a significant threat as disseminating increasingly sophisticated fake news content undermines societies globally. Notably, the unanticipated ramifications of Twitter’s inception over 12 years resulted in a complex interplay of societal and technological challenges. Moreover, there is a pervasive concern regarding the cessation of Russian cyberattacks, requiring platforms such as YouTube to refocus their efforts on purging detrimental content.

Plastic surgeons have recently introduced the term” Snapchat dysmorphia” to describe” a phenomenon where” young individuals desire surgical procedures to resemble their filtered versions typically showcased on social media platforms [

11]. In India, the detrimental consequences of fake news have been tragically illustrated by the deaths of a dozen individuals at the hands of internet lynch mobs [

12]. This is a stark reminder that misinformation can have real, devastating implications. Moreover, in the current climate of misinformation, unfounded fears have surfaced regarding the transmission of the coronavirus through the consumption of Chinese cuisine. This showcases a concerning shift from the information age to an era of widespread disinformation [

13].

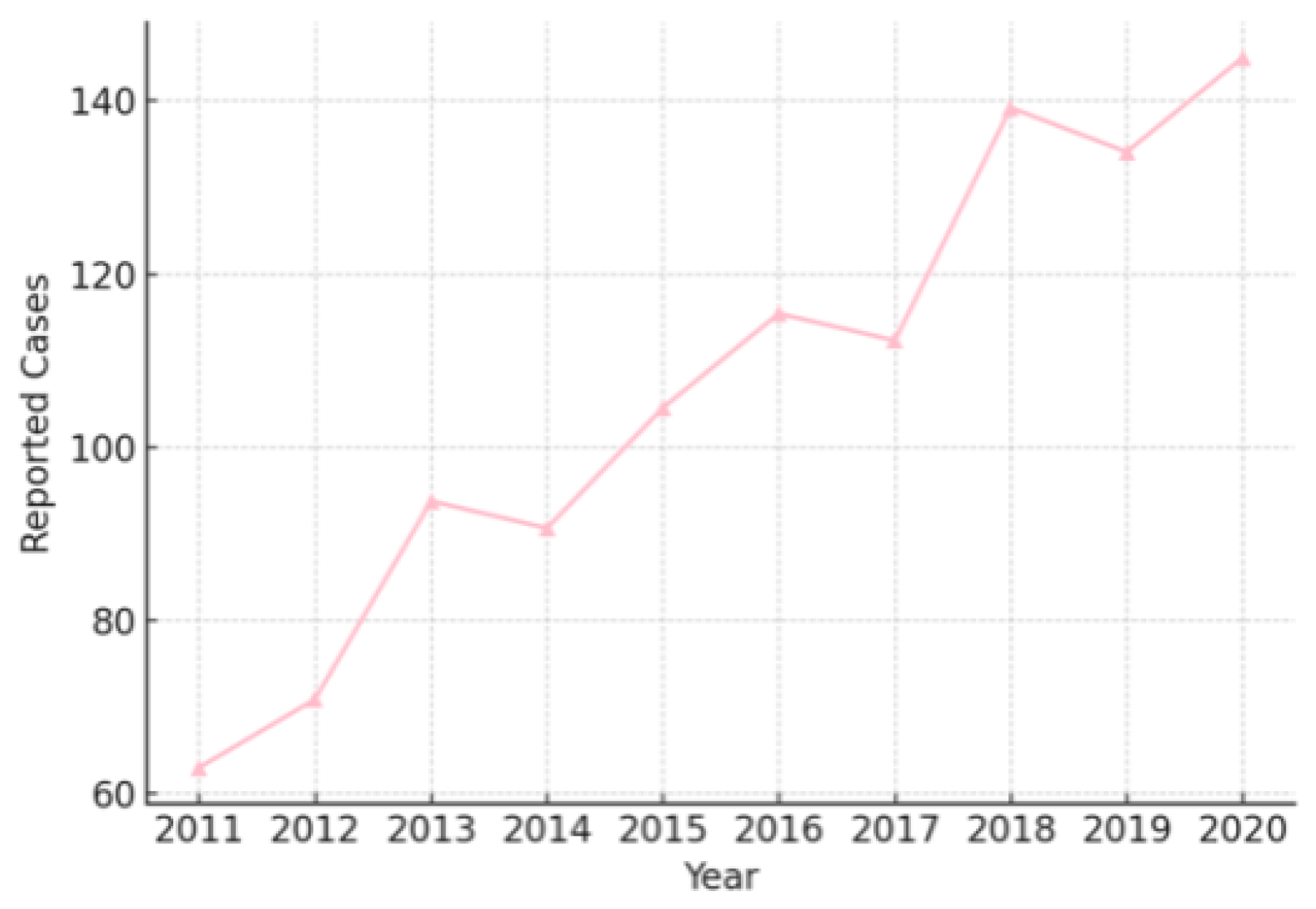

A survey by the American Academy of Facial Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery reported that 55% of surgeons had patients requesting procedures to improve their appearance in selfies, an increase from 42% in 2015. This trend is particularly prevalent among younger demographics, with 90% of Snapchat users aged between 13 and 24 and 60% being female. The pervasive use of beauty filters has raised concerns about their impact on self-esteem and body image, especially among adolescents. A study found that 60% of girls felt upset when their real appearance did not match their filtered images. The increasing trend in reported cases of Snapchat dysmorphia underscores the psychological impact of augmented reality filters on self-perception. The data suggests a direct correlation between the widespread adoption of beauty-enhancing filters and a rise in cosmetic surgery consultations among younger demographics. This trend raises ethical concerns about digital beauty standards and their influence on mental health, particularly among teenagers who may develop unrealistic expectations of their physical appearance. These statistics, shown in

Figure 3 underscore the growing influence of social media on individuals’ perceptions of beauty and the increasing demand for cosmetic procedures to align with these altered standards.

The current state of the tech industry is rife with grievances, scandals, data theft, tech addiction, fake news, and election hacking. It raises the question of whether there is an underlying cause that gives rise to these multifaceted issues simultaneously. The absence of a singular designation for this problem within the tech industry calls for a broader understanding. As one surveys the current landscape, one sees an impression of a world descending into chaos, prompting reflection on whether this is the new normal or a result of an inexplicable influence. Ideally, a more widespread comprehension of these dynamics should not be the exclusive domain of the tech industry but rather common knowledge for all.

3. Business Strategies of Technology and Social Media Companies

The contemporary business strategy of major technology companies, such as Facebook and Google, revolves around acquiring and commercialising user attention. These companies provide complementary services to users, which advertisers essentially finance. The primary commodity marketed to advertisers is user attention. Revenue is derived from the display of advertisements, which subtly influence and shape user behaviour and perception. This gradual and imperceptible transformation in user conduct and perception constitutes the commodity monetised by these firms.

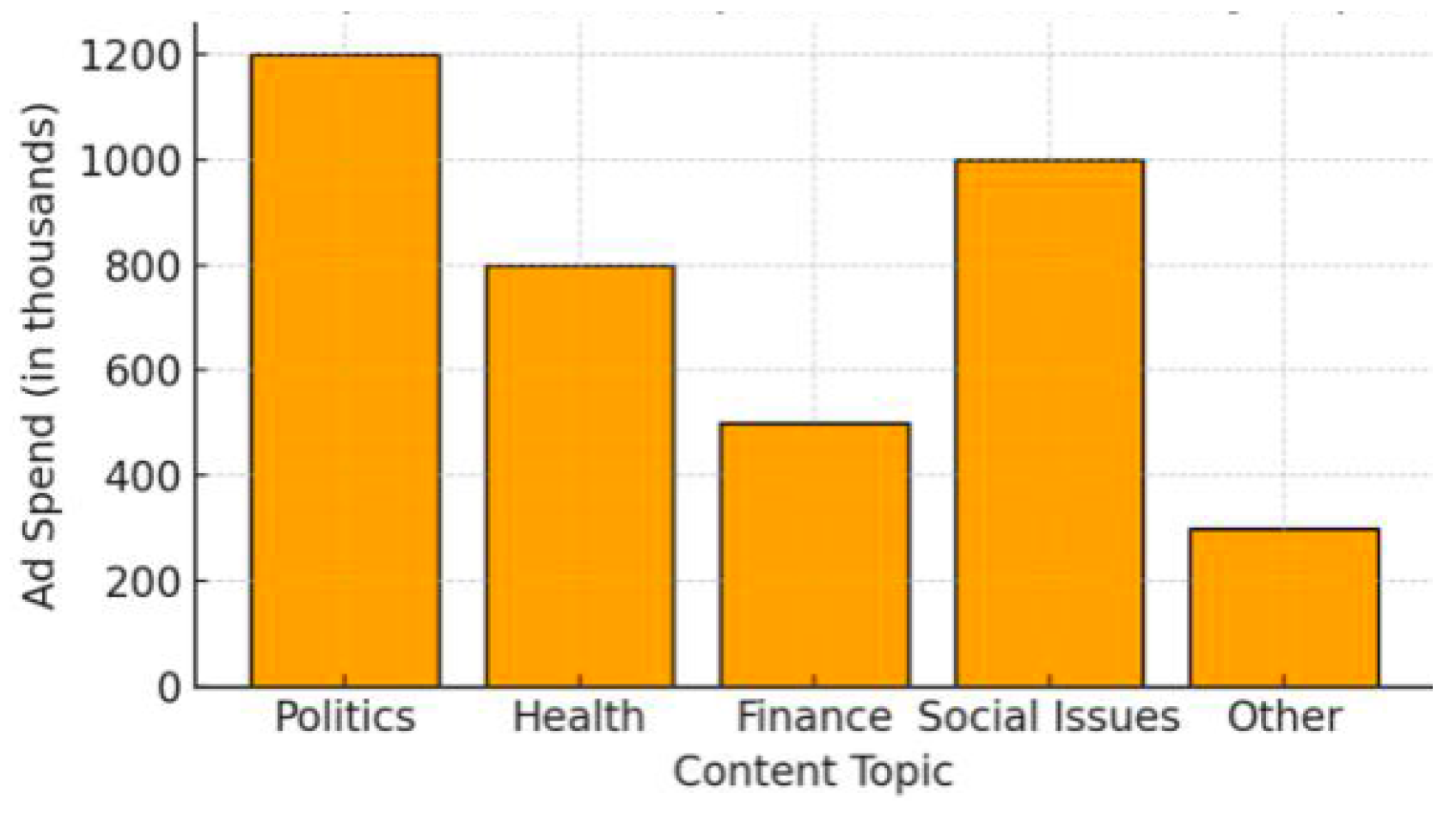

Figure 4 illustrates how various topics receive differential levels of advertising spend for manipulative content, particularly in politically charged discussions, health misinformation, and consumer behavior influences. The dominance of certain topics suggests a deliberate effort by entities to drive engagement through controversial or misleading content. The financial incentive for such manipulation aligns with platform algorithms that prioritise engagement, often at the cost of information credibility.

Consequently, the paramount value proposition lies in the capacity to influence and alter individuals, rendering their attention the most prized asset. This aligns with the business’s” perennial aspiration for” guaranteed successful advertisement placement, which epitomises its trade. They essentially sell certainty. Success in this sphere hinges on accurate predictions, necessitating copious amounts of data [

14].

Researchers refer to this phenomenon as" "surveillance capitalism”, which is the concept of companies making money by extensively tracking people’s movements and activities through large technology firms [

15]. Their primary goal is to ensure that advertisers achieve maximum success. This creates a new and unprecedented marketplace that trades exclusively in human futures. Like there are markets for trading in commodities like pork bellies or oil futures, we now have markets that deal in human futures on a massive scale. These markets have generated trillions of dollars, making internet companies the wealthiest in human history.

Individuals must recognise that their online activities are subject to extensive surveillance, tracking, and measurement. Every interaction is meticulously monitored and logged, including specific details such as the time spent viewing particular images. The level of understanding extends to detecting instances of loneliness and depression and even examining past relationships. This surveillance encompasses a broad spectrum of personal traits, extending to an individual’s personality type that surpasses the extent of information ever amassed in the annals of human history. With minimal human oversight, an autonomous system processes this data to generate increasingly accurate human behaviour and characteristics forecasts.

4. Facebook’s Data Utilisation and Ethical Concerns

Some researchers view the development as a "re-engineering" of human nature, suggesting that these companies are intruding upon and reshaping the most intimate aspects of personhood. This may have profound implications for the future of human autonomy and free will [

16,

17,

18]. This new paradigm’s unequal distribution of power and wealth raises ethical concerns as a few individuals and entities gain disproportionate influence over society [

19].

Numerous individuals believe that Facebook sells out when, in fact, it is contrary to Facebook’s business interests. The platform utilises this data to construct predictive models of user behaviour, with the most accurate model yielding competitive advantages [

20]. Moreover, as user browsing speed decelerates” towards the end of their average session duration, Facebook strategically generates additional content to maintain user engagement [

21]. This strategic approach suggests that Facebook has developed an intricate model of users” online habits, encompassing their clicks, watched videos, and liked posts. This model enables Facebook to anticipate interactions and curate content that sustains user interest [

22,

23,

24,

25].

Facebook’s utilisation of user data goes beyond mere sales or exploitation. The platform employs sophisticated predictive modelling to gain competitive advantages by anticipating and shaping user behaviour [

20]. As users’ browsing slows towards the end of their average session, Facebook strategically generates additional content to sustain their engagement [

21]. This strategic approach demonstrates Facebook’s intricate understanding of users’ online habits, encompassing their clicks, watched videos, and liked posts [

22,

23,

24,

25]. By analysing this wealth of data, Facebook can accurately predict user interactions and curate personalised content that keeps them captivated and invested in the platform. While controversial, This extensive data-driven strategy is central to Facebook’s business model and ability to attract and retain users, ultimately driving its commercial success.

While the benefits of social media platforms are widely recognised, significant ethical concerns regarding data privacy and the potential for manipulative tactics also exist. Data serves as the foundation of the surveillance capitalism business model, and individuals’ personal information is the raw material that fuels this system [

26,

27]. The monetisation of user attention and the exploitation of human psychology for commercial gain raise critical ethical questions about the appropriate use of technology and the safeguarding of individual autonomy.

5. Privacy Trade-Offs in the Age of Big Data

As the digital landscape continues to evolve, the tension between the benefits of data-driven technologies and the preservation of individual privacy has become increasingly pronounced. The proliferation of social media, the ubiquity of smartphones, and the rise of smart cities have all contributed to the exponential growth of data streams, which can be mined and analysed to gain profound insights into people’s lives [

26].

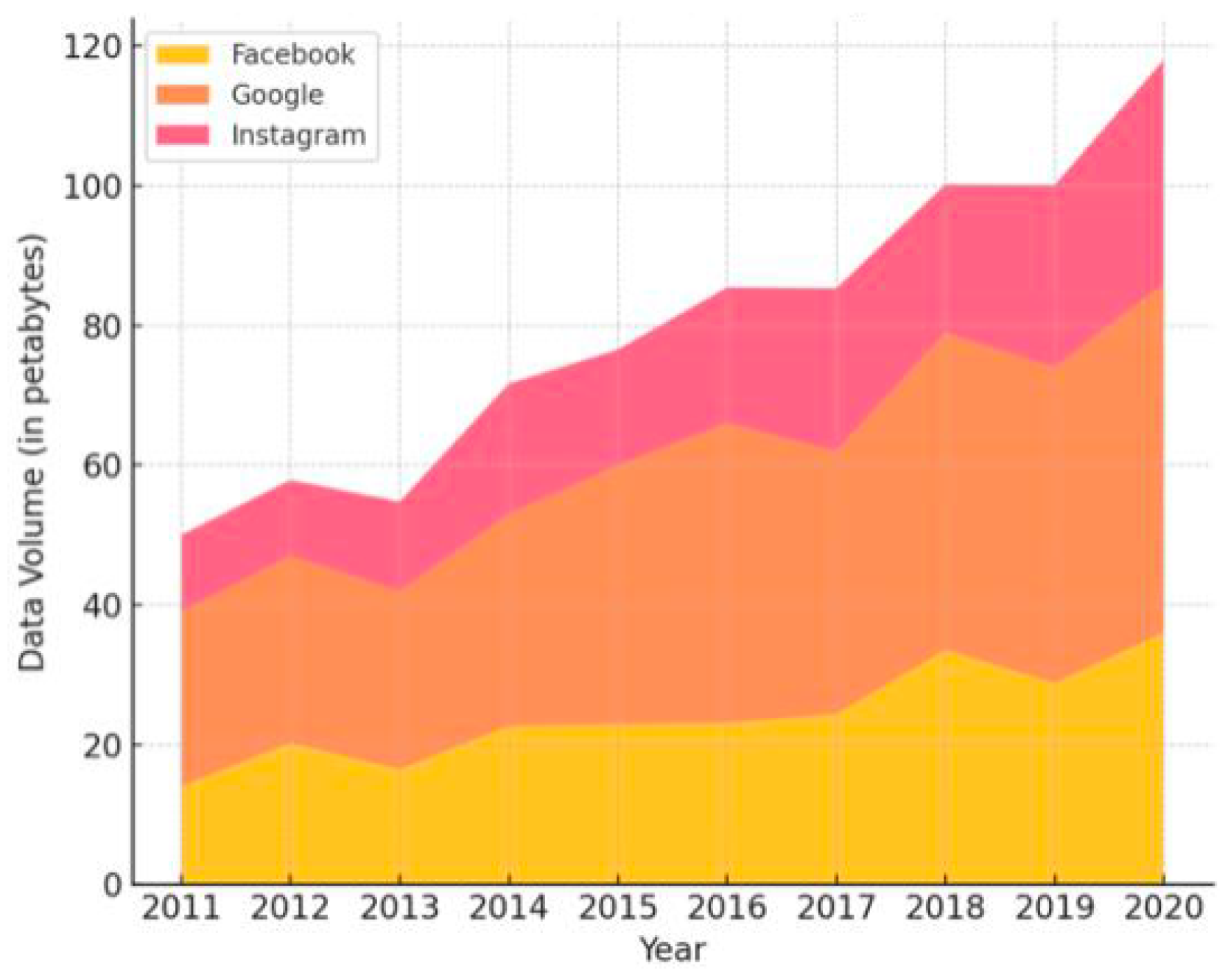

The exponential growth in global data streams (see

Figure 5) highlights the expanding role of digital platforms in modern life. While this increase enables greater connectivity and data-driven decision-making, it also raises concerns about privacy, data security, and user autonomy. Tech giants’ acceleration of data collection underscores the need for robust regulatory frameworks to manage ethical considerations and prevent potential misuse.

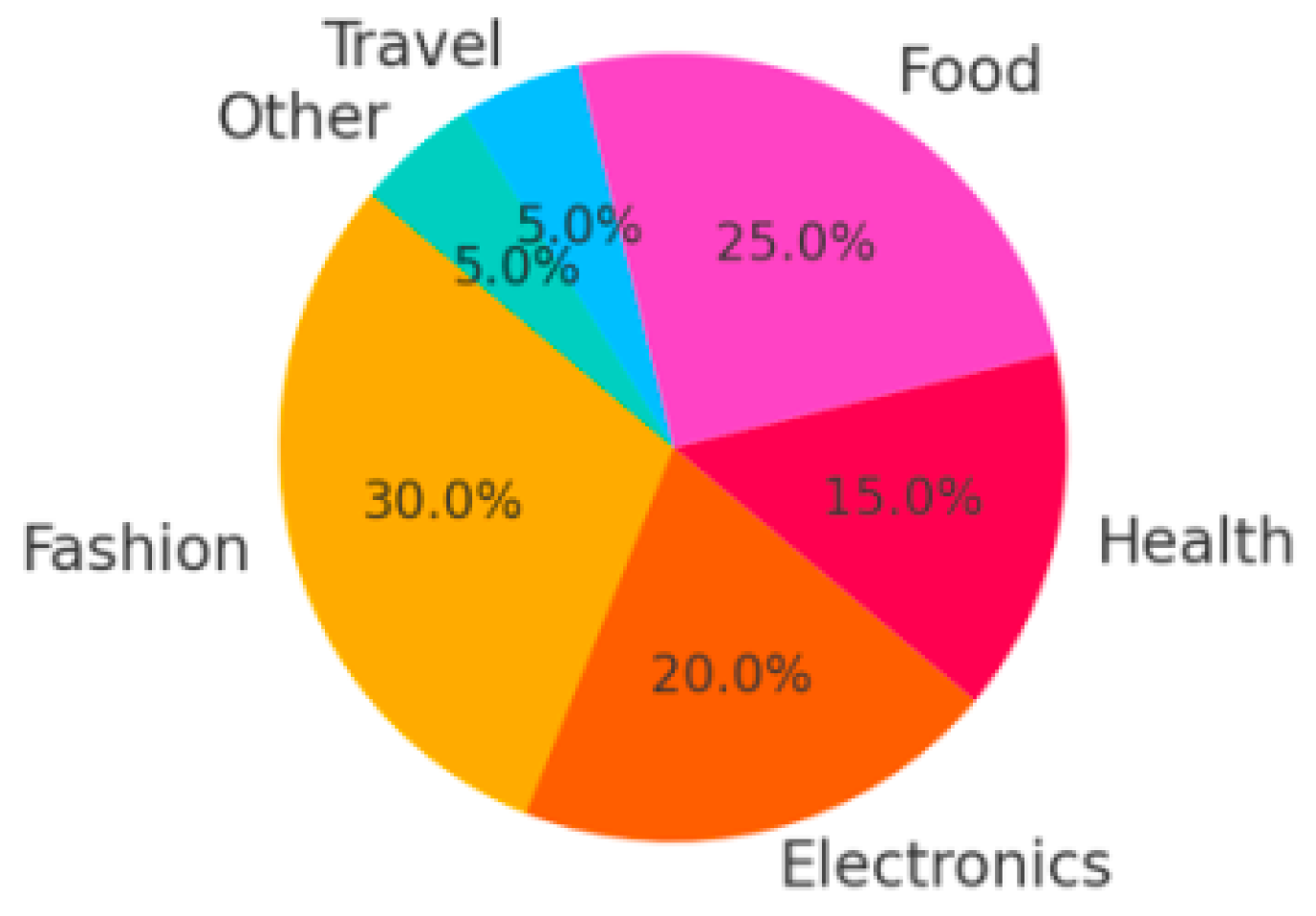

This data can be leveraged to provide personalised recommendations, targeted advertising, and enhanced customer experiences. The impact of social media on consumer behaviour is evident in the increasing reliance on influencer marketing and targeted advertising, depicted in

Figure 6. Platforms leverage user data to personalise recommendations, often blurring the lines between organic content and sponsored advertisements. While this approach enhances user engagement, it also raises concerns about consumer manipulation and data-driven persuasion tactics. By doing so, individual’s personal information and behavioural patterns are exposed, potentially compromising their privacy [

28].

The asymmetry of power in data access and utilisation is a significant concern. Large technology companies possess the resources and capabilities to collect, analyse, and monetise vast troves of user data. At the same time, individuals often have limited awareness or control over how their information is used [

26].

This imbalance can lead to a "double bin" for users who may feel compelled to participate in these data-driven networks to maintain social connections and access desired services, even if it means sacrificing some degree of privacy.

Figure 7 demonstrates a paradox where users, despite growing awareness of privacy risks, continue to engage with data-driven networks. The prevalence of these platforms in everyday life creates an ecosystem where opting out is not a viable option for most individuals. Consequently, regulatory interventions and ethical business practices are needed to ensure transparency and safeguard users’ digital rights. The risks include the potential for misuse, manipulation, and infringement of personal autonomy, as companies can leverage their data-driven insights to influence user behaviour and decision-making.

The dilemma of data privacy and the power dynamics inherent in surveillance capitalism underscores the need for a comprehensive and nuanced understanding of the ethical implications of big data and intelligent technologies [

29]. Researchers have highlighted the importance of developing robust privacy regulations, empowering individuals with greater control over their data, and fostering a more transparent and accountable data ecosystem [

30,

31,

32].

As the digital revolution continues to reshape our lives, we must address these complex issues and strive to balance the benefits of data-driven innovation and the fundamental right to privacy and self-determination.

6. Objectives and Ethical Implications of Tech Business Strategies

Tech businesses mainly have three primary objectives: (1) Engagement goal: to enhance user activity and sustain user engagement; (2) Growth goal: to retain users and incentivise them to invite more individuals to utilise the platform; and (3) Advertising goal: to optimise advertising revenue while concurrently achieving the goals above [

33]. These objectives are steered by algorithms that dictate content presentation to bolster these metrics. At Facebook, the notion of dynamically adjusting these objectives and metrics exists, akin to fine-tuning specific elements based on immediate requirements, such as expanding the user base in a particular region or maximising advertising. This degree of accuracy and authority is widespread among numerous tech enterprises.

In contemporary society, the predominant mode of communication, particularly for younger generations, has shifted towards online connectivity. However, the financial underpinning of this digital connection often involves a third party who seeks to manipulate the interactions between individuals. This pervasive influence has contributed to developing a global generation shaped by a context where communication and culture are imbued with manipulation. Consequently, deceit and deception have emerged as fundamental components that permeate our societal interactions.

The early neuroscientists and psychologists were pioneers in comprehending the intricate workings of the human mind. Their empirical approach allowed for real-time experimentation, akin to the method employed by magicians who exploit certain aspects of the human psyche to create illusions. Despite professionals in domains such as medicine, law, and engineering possessing extensive knowledge in their respective fields, they may need a deeper understanding of their vulnerabilities, constituting a distinct discipline relevant to all individuals.

7. Persuasive Technology and the Quest for User Attention

Tech companies have increasingly leveraged persuasive technologies to captivate and retain user attention. These technologies are designed to influence human behaviour, often in subtle and subconscious ways, with the primary objective of driving engagement and commercial success [

34,

35].

The concept of persuasive technology revolves around purposely designed features aimed at covertly modifying human behaviour and instilling unconscious habits [

36]. For example, the ubiquitous pull-down refresh action on digital devices gives rise to a positive intermittent reinforcement reminiscent of the mechanics of slot machines in Las Vegas. The overarching goal lies in deeply embedding unconscious routines within users, engendering sustained engagement without their conscious realisation—an intentional design technique to influence user behaviour and foster enduring product engagement strategically.

Photo tagging on social media like Facebook presents a compelling case study. When users receive an email notification that they have been tagged in a photo, they are inclined to engage with the content promptly. This behaviour is rooted in human psychology, as individuals respond quickly to social cues [

37,

38]. It is worth noting that the email does not contain the photo but rather a notification of its availability. Integrating the photo within the email would significantly streamline the content. Facebook has the potential of this feature to drive user engagement and implement it accordingly. By doing so, the platform leveraged this functionality to boost user interaction and frequent photo tagging among its user bases.

8. Growth Hacking and the Exploitation of User Psychology

The concept of "growth hacking" has emerged as a strategic approach for tech companies to expand their user base and achieve exponential growth rapidly. Rather than relying solely on traditional marketing methods, growth hacking encompasses diverse techniques that exploit human psychology and cognitive biases to propel user acquisition and retention.

One prominent growth hacking tactic is using social proof, where companies leverage the influence of other users’ actions and opinions to persuade individuals to join or engage with the platform [

39]. Techniques like displaying the number of active users, showcasing positive reviews, or highlighting the popularity of a product can trigger the psychological phenomenon of social conformity, leading users to perceive the service as more desirable and trustworthy.

Another growth hacking strategy involves the strategic use of scarcity and urgency. Tech companies often create a sense of limited availability or time-sensitive offers to induce users to fear missing out (FOMO), prompting them to sign up or purchase before the opportunity expires [

40].

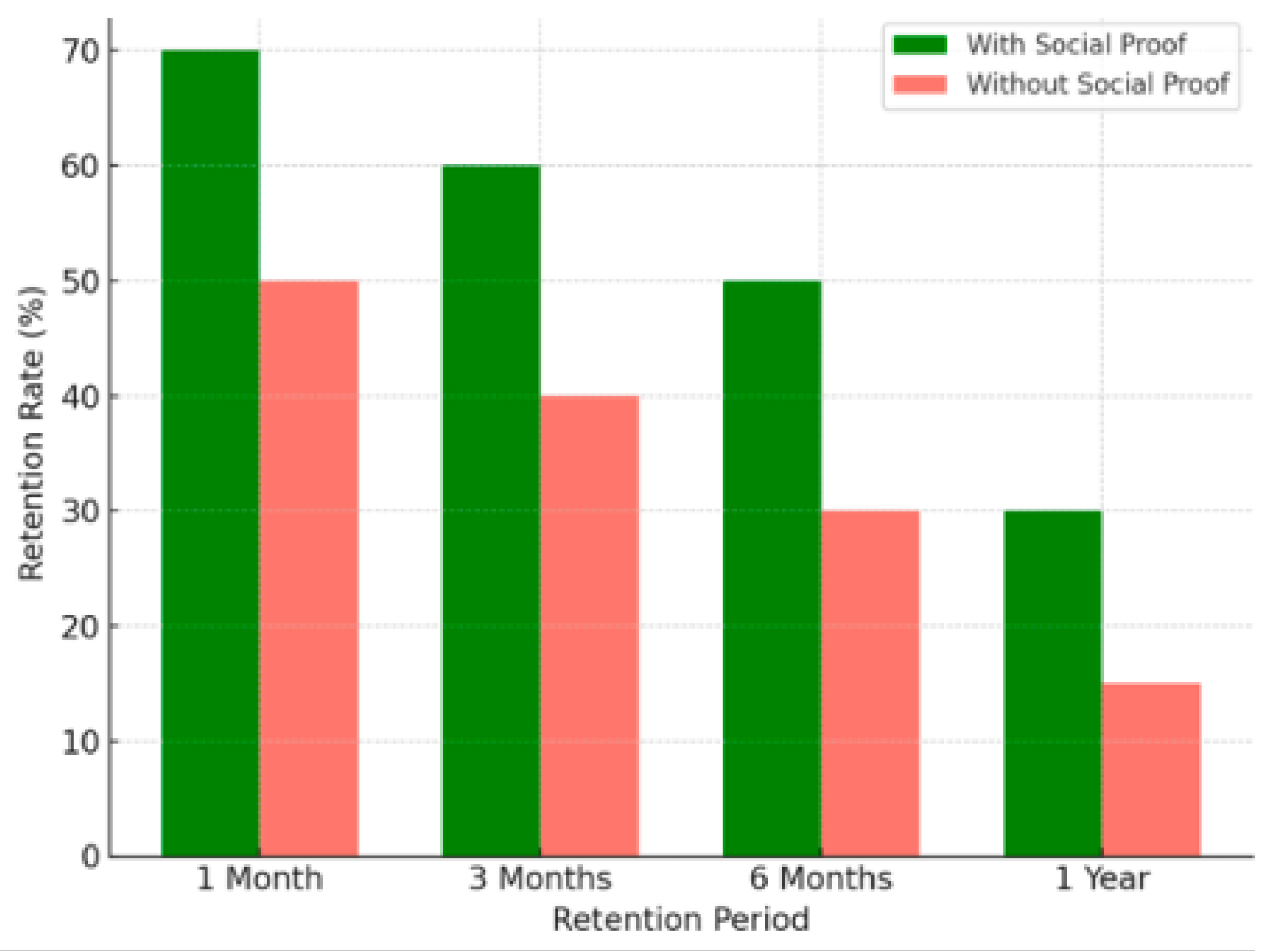

Figure 8 illustrates the effectiveness of social proof strategies in retaining users. Platforms that prominently display engagement metrics, such as likes, shares, and comments, encourage users to stay engaged longer. This approach capitalises on psychological factors, such as fear of missing out and peer influence, to sustain user activity.

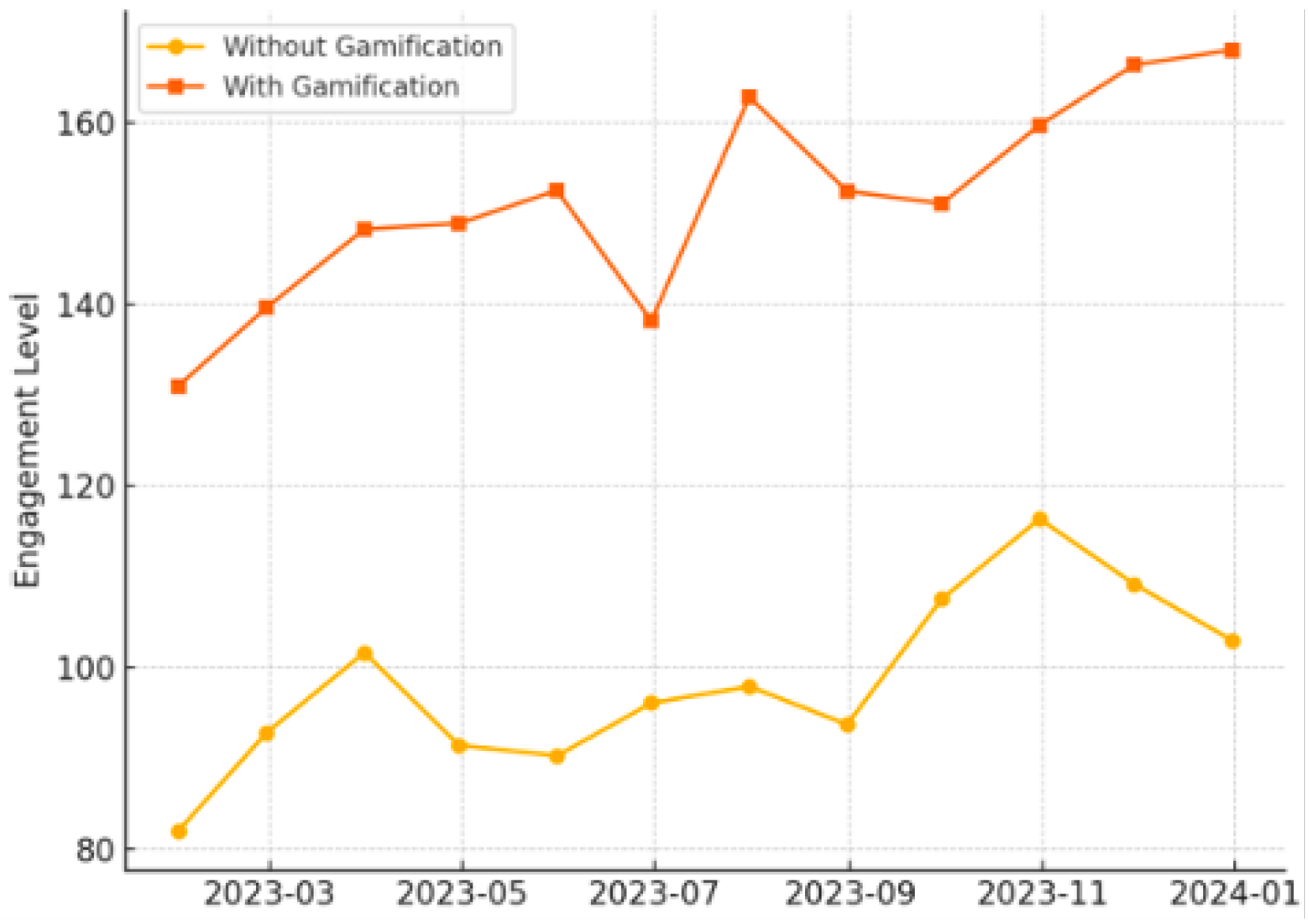

Another growth hacking technique employed by tech companies is the strategic implementation of gamification, wherein game-like elements are integrated into non-game contexts. Features such as point systems, leaderboards, and virtual rewards can tap into users’ innate desires for achievement, competition, and status, enhancing engagement and fostering a sense of loyalty to the platform. As shown in

Figure 9, gamification strategies, such as badges, leaderboards, and rewards, have been shown to significantly increase user engagement. By tapping into intrinsic motivations for achievement and competition, these features foster prolonged platform interaction. However, excessive reliance on gamification can lead to compulsive behaviours, necessitating ethical considerations in design.

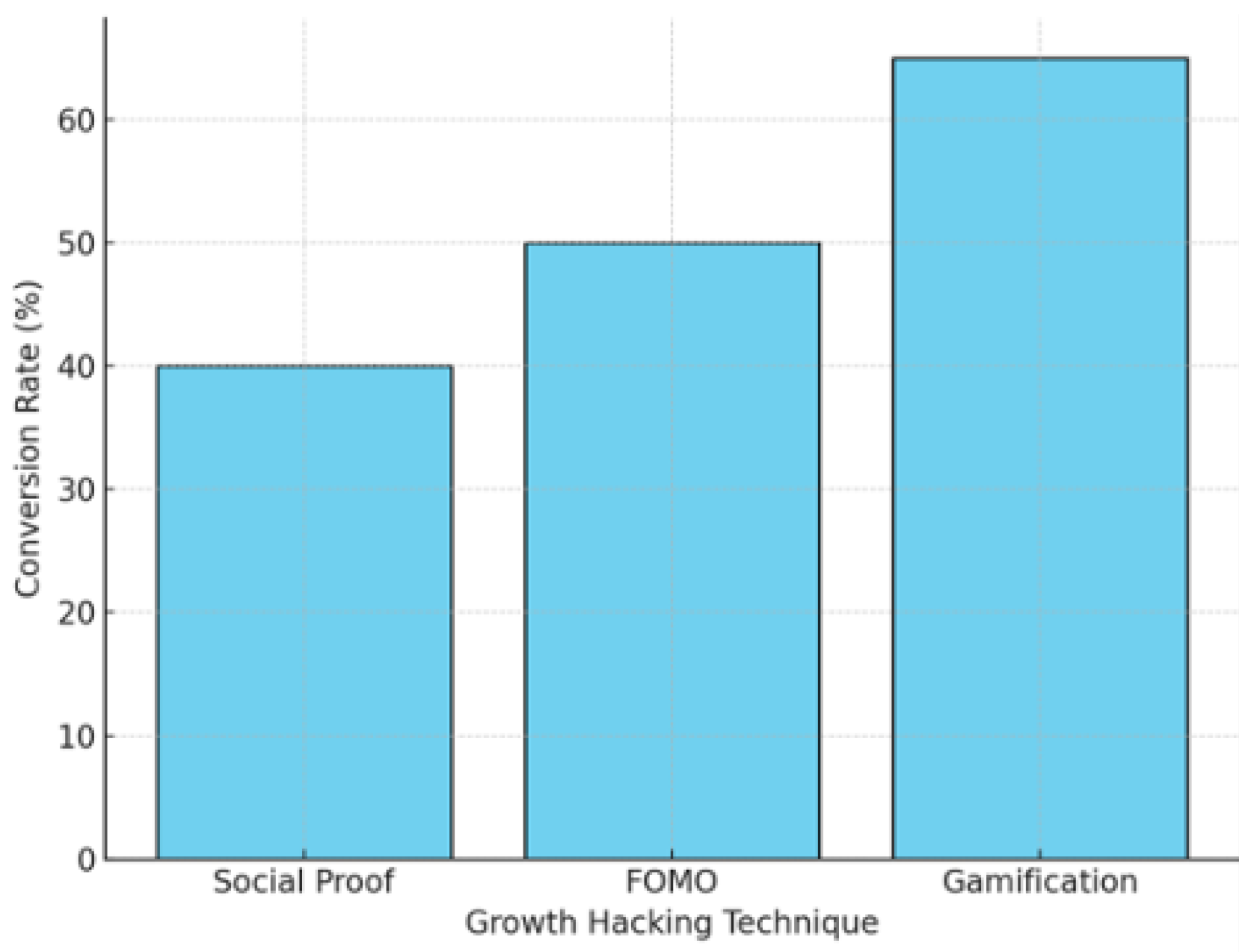

These growth hacking tactics leverage a deep understanding of human psychology, cognitive biases, and social dynamics to propel user engagement and acquisition. Companies that excel at growth hacking expand their user base and achieve exponential growth rapidly, often outpacing their competitors [

41,

42,

43]. Growth hacking techniques, including referral programs, FOMO, and gamification, have been instrumental in driving rapid user adoption. The data in

Figure 10 reflects how platforms that employ psychological triggers, such as scarcity and urgency, achieve higher conversion rates. However, ethical concerns arise when these tactics exploit cognitive biases to influence decision-making.

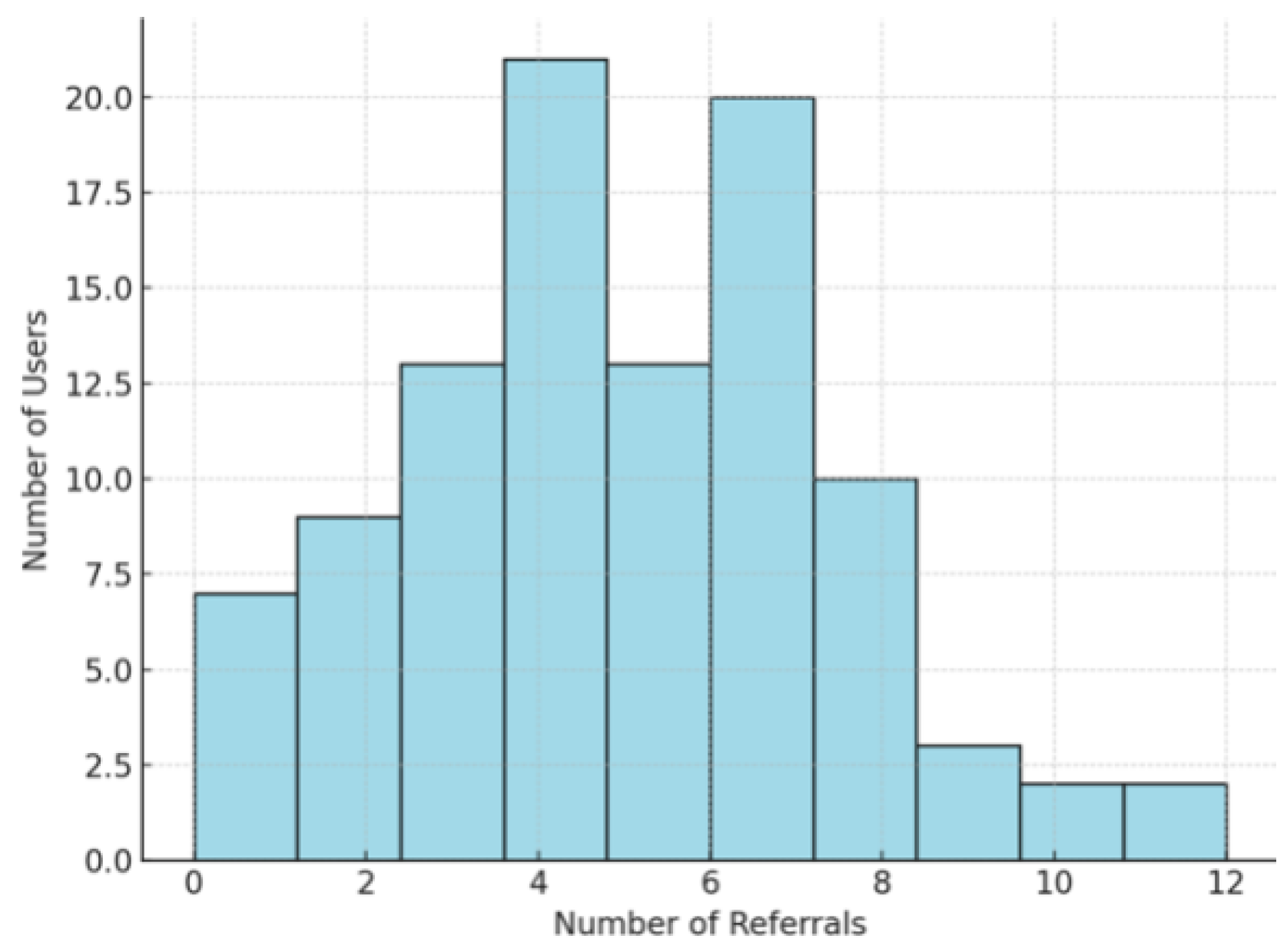

Within the technological exists a distinct discipline known as growth hacking, wherein engineering teams leverage psychological strategies to elicit increased user signups, engagement, and referrals. Notably, the former head of growth at Facebook espoused the efficacy of attaining each user to introduce seven friends within days (see

Figure 11). Based on perpetual experimentation and minor feature modifications, this approach has been widely adopted within Silicon Valley, with companies like Google and Uber employing similar methodologies [

44]. These referral-based growth strategies leverage existing users to acquire new ones through incentivised sharing. This method capitalises on trust within social circles, making it one of the most effective yet ethically ambiguous marketing approaches. While it enhances user base expansion, concerns regarding data privacy and targeted advertising arise. Moreover, such practices have been subject to ethical scrutiny due to their perceived manipulative nature.

9. Subliminal Manipulation and Psychological Experimentation on Social Media

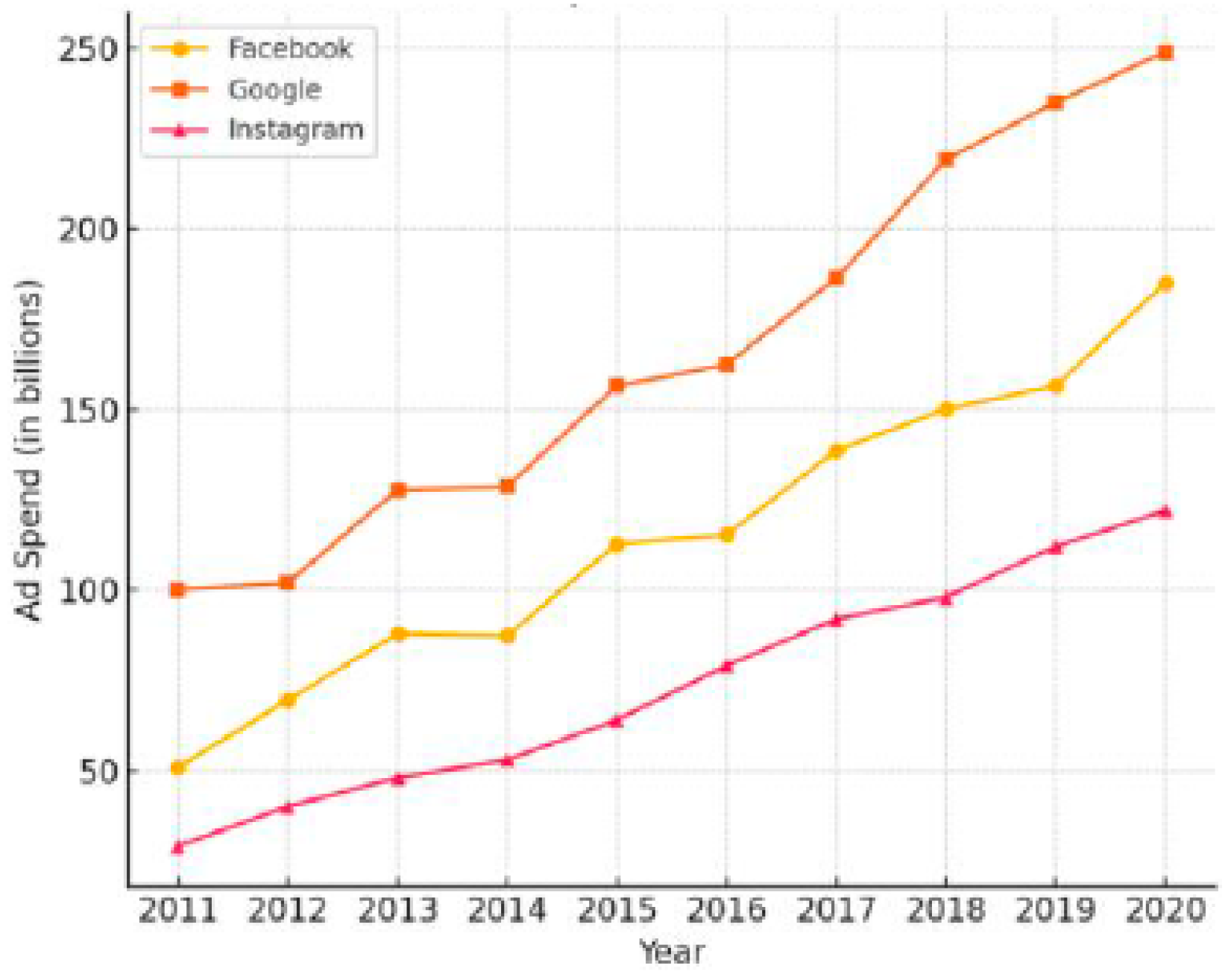

Social media platforms have been at the forefront of leveraging user data and advanced analytical techniques to influence user behaviour subtly. Techniques such as "privacy suckering" - tricking users into sharing private information - have been employed to gather detailed user profiles that can be exploited for targeted advertising and content curation.

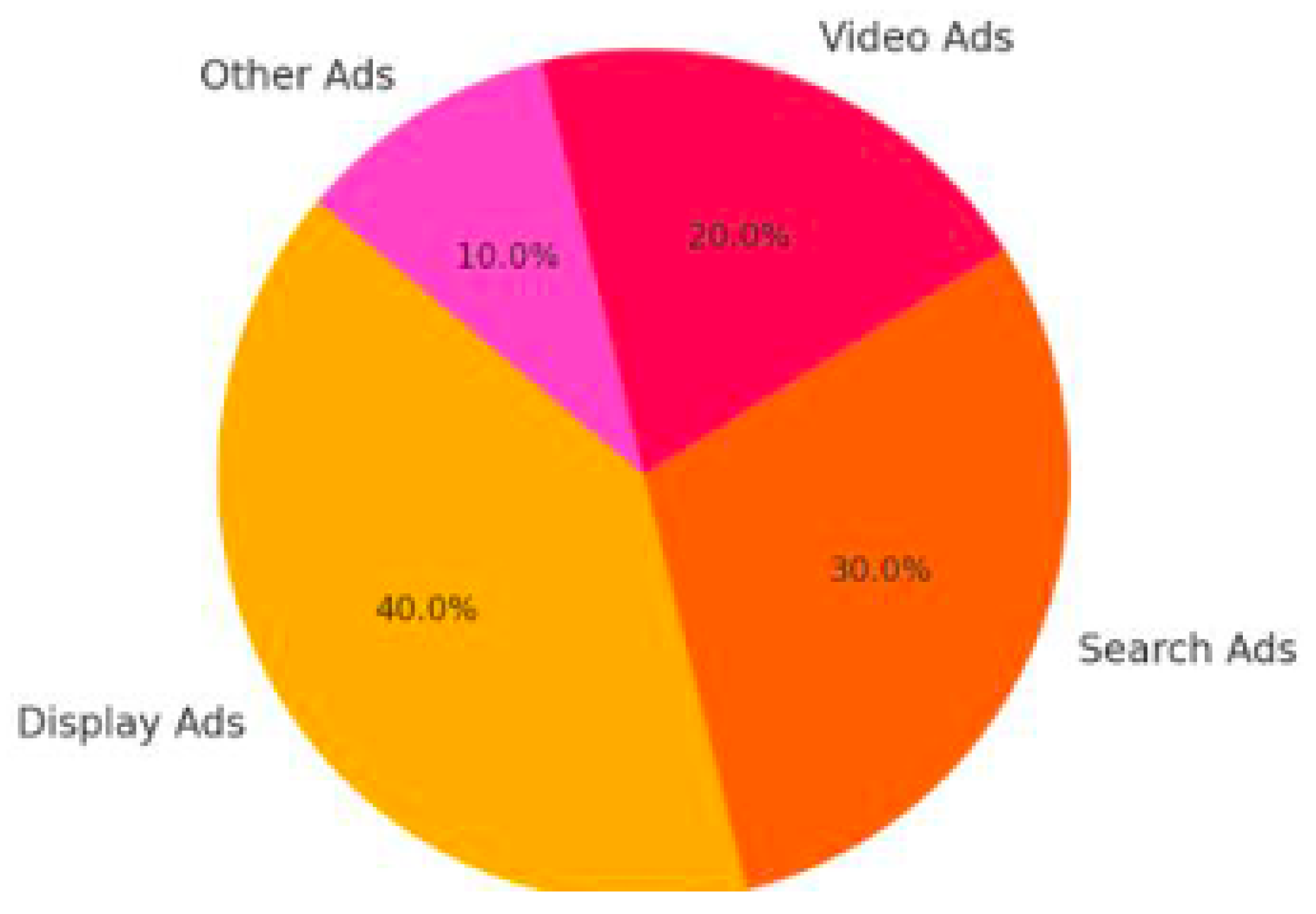

Figure 12 demonstrates the continuous increase in advertising expenditures on social media platforms, reflecting the shift from traditional marketing to digital-first strategies. This growth underscores the commercialisation of user engagement, where data-driven ad targeting has become the dominant revenue model. The implications for user autonomy and privacy require further scrutiny. This breakdown of advertising revenue, shown in

Figure 13 highlights the dominance of targeted ads, influencer partnerships, and promoted content. The dependency on ad-based monetisation raises concerns about content neutrality, as platforms prioritise engagement-driven content over unbiased information dissemination.

Moreover, social media giants have conducted psychological experiments on their user base without explicit consent to understand how to influence emotions and decision-making more effectively. Facebook’s widely publicised "emotional contagion" study, in which the platform manipulated the news feeds of nearly 700,000 users to study the spread of positive and negative emotions, exemplifies the extent to which these companies are willing to experiment on their users in pursuit of commercial objectives [

45].

The social media platform Facebook executed large-scale contagion experiments to analyse the impact of subliminal cues on Facebook pages on stimulating voter turnout during the midterm elections [

46]. The results indicated that these subtle cues effectively influenced real-world behaviour and emotions without the user” conscious awareness. The endeavour is leveraging artificial intelligence to comprehend and manipulate stimuli that prompt human responses, resembling a symbolic replication of nerve cell stimulation to observe leg movement in a spider. This approach can be likened to psychological incarceration, where individuals are unknowingly subjected to manipulation for profiteering [

47,

48]. The ultimate objective is to expedite the psychological manipulation of individuals and subsequently provide them with a dopamine hit. Several prominent social media platforms such as Facebook, Instagram, WhatsApp, Snapchat, and Twitter have adeptly, although consciously, exploited vulnerabilities in human psychology to enhance user engagement. The consciousness of these psychological vulnerabilities, presumably known to the creators and innovators of these platforms, did not deter them from proceeding with these strategies.

The emergence of bicycles did not provoke societal alarm; instead, people readily embraced the innovation. No catastrophic proclamations were made, such as bicycles jeopardising family bonds or undermining democratic foundations. A vital distinction arises when considering tools versus non-tools: tools patiently await utilisation, while non-tools incessantly demand attention, manipulate, and seduce. This shift from a tools-based technological environment to one rooted in addiction and manipulation characterises the modern era. Social media, for instance, is not a passive tool; it possesses distinct goals and employs psychological exploitation to attain them.

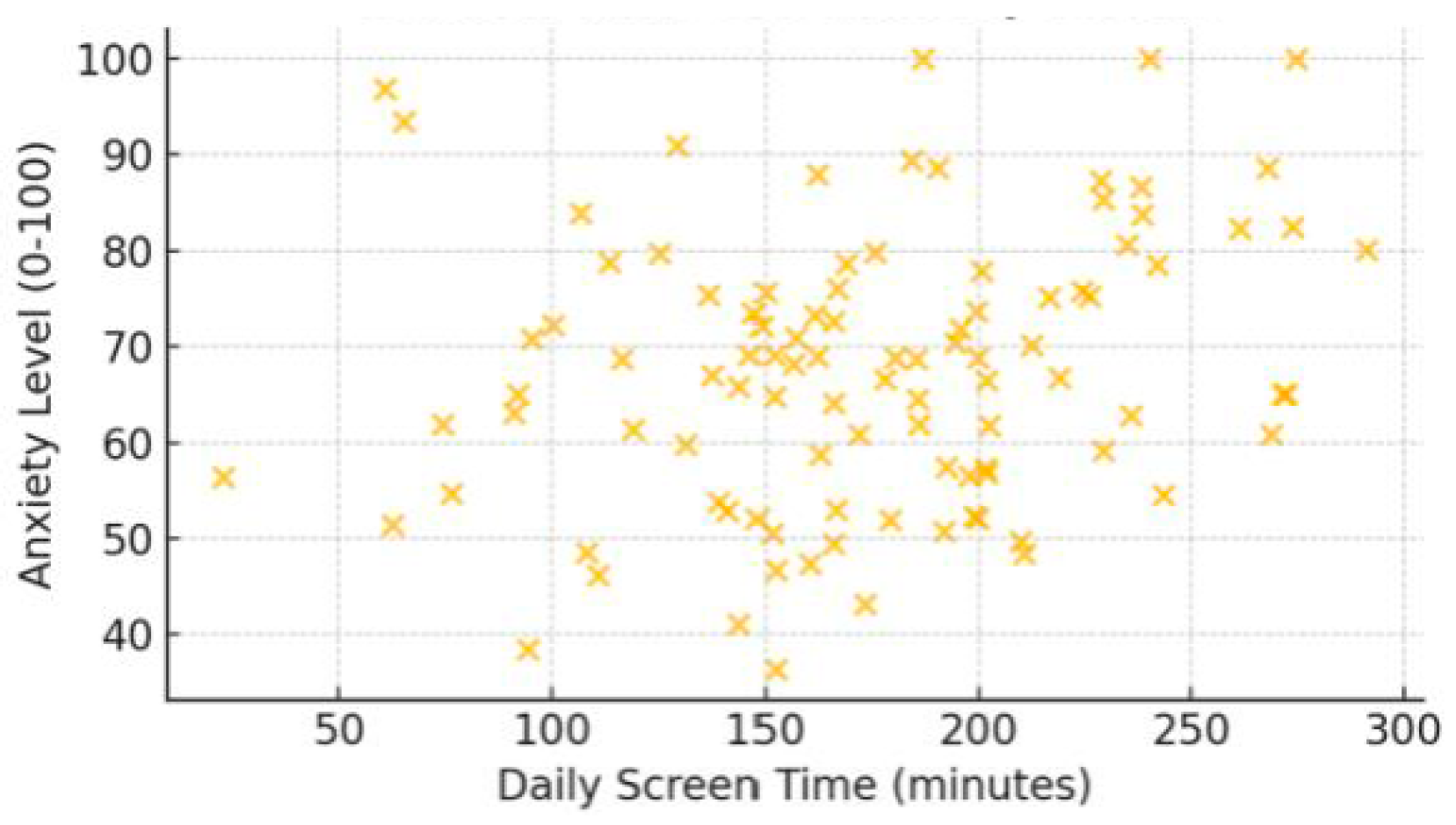

When social media is likened to a drug, it becomes evident that humans possess an innate biological drive to connect with others. This drive triggers the release of dopamine and activates reward pathways. Eons of evolution have honed this mechanism to facilitate communal living, mating, and procreation. Consequently, optimised to amplify human connection, social media inevitably harbours addictive potential. As shown in

Figure 14, a clear correlation emerges between increased screen time and heightened anxiety levels, particularly among adolescents. The always-connected nature of digital platforms contributes to stress, sleep disturbances, and social comparison pressures. These findings underscore the need for digital well-being initiatives and mindful technology use.

Crucially, the development of technological products did not prioritise the well-being and protection of children under the guidance of child psychologists. Instead, these products were engineered to create algorithms that suggest content and enhance images. The issue goes beyond mere attention-steering and delves into the pervasive influence of social media on children’s self-esteem and identity; individuals are driven by fleeting signals of online validation, equating these ephemeral digital metrics with personal worth and truth. This tenuous form of popularity fosters feelings of emptiness and perpetuates an unrelenting cycle of seeking subsequent validation. The implications, magnified by 2 billion users and societal perceptions, are profoundly concerning.

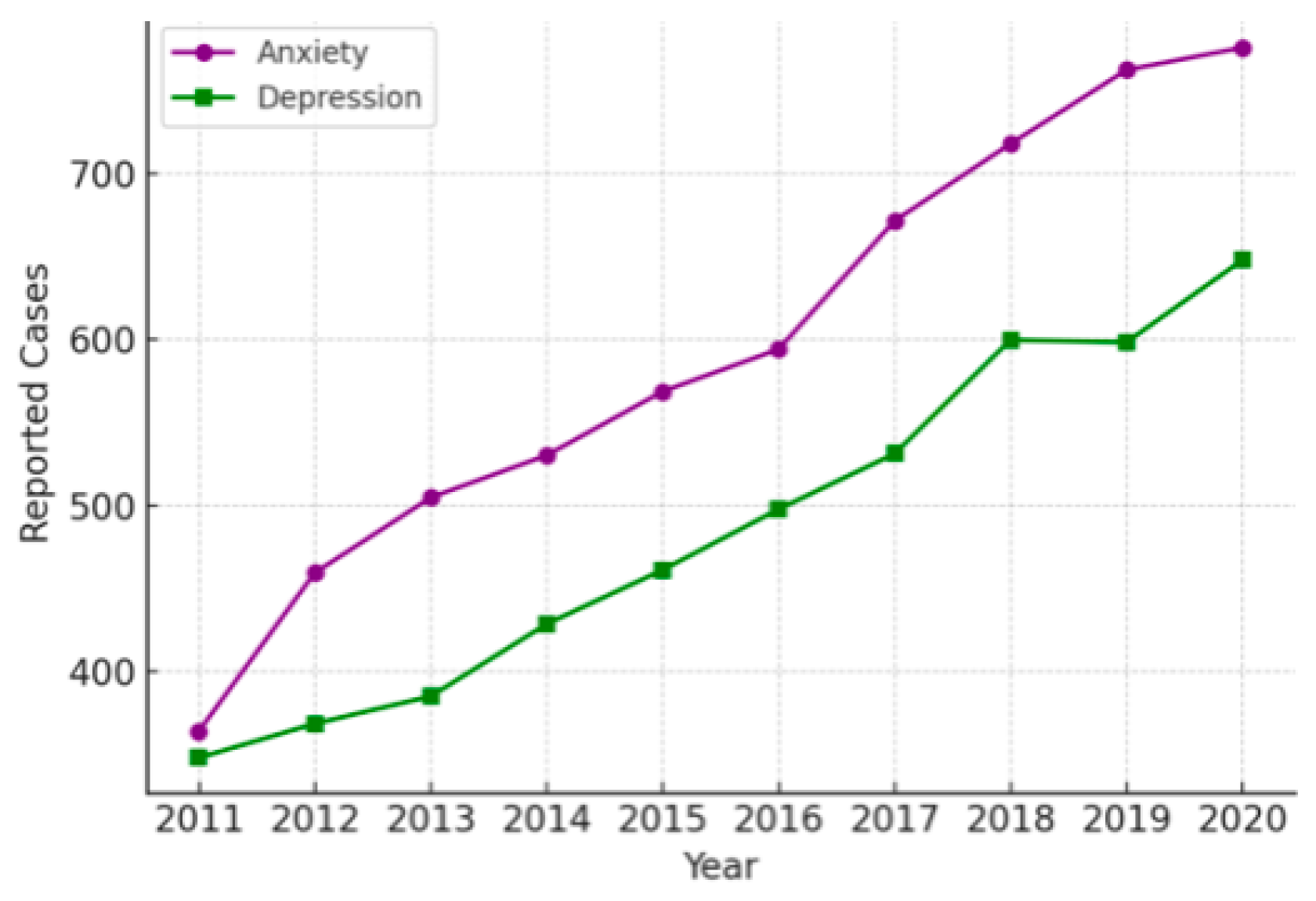

10. The Rise of Adolescent Mental Health Issues in the Social Media Era

The prevalence of depression and anxiety among American adolescents has experienced a substantial increase beginning around 2011-2013. Hospital admission rates for self-harming behaviours among teenage girls per 100,000 remained relatively stable until approximately 2010-2011, after which a significant increase was observed [

49].

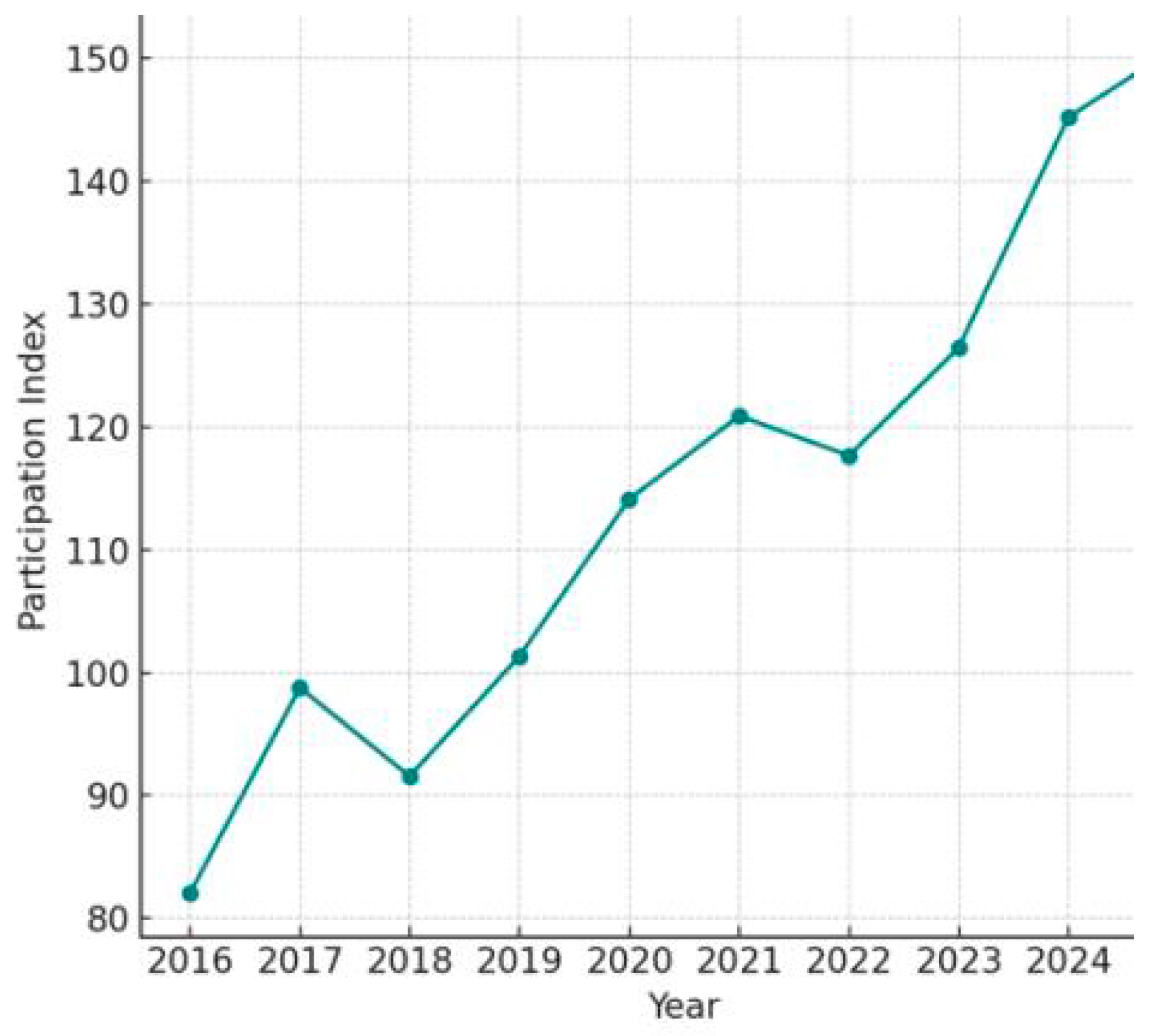

Figure 15 shows the rising trend in social media-related mental health issues aligns with the growing prevalence of digital connectivity. This increase amounted to 62% for older adolescent girls (15-19 years old) and nearly tripled to 189% for preteen girls. Moreover, suicide rates for older teenage girls increased by 70% compared to the previous decade, while preteen girls saw a staggering 151% increase [

50]. These trends have been linked to the pervasive influence of social media on Generation Z, the cohort born after 1996 who were the first to engage with social media during middle school [

51]. This shift has led to a reduction in traditional activities, with adolescents devoting more time to electronic devices, resulting in heightened anxiety, emotional fragility, depression, and a diminished propensity for risk-taking. Furthermore, there has been a notable decline in the acquisition of driver’s licenses and participation in driver’s semantic interactions among this demographic. The implications of these changes extend beyond the individuals themselves, with families also experiencing trauma and bewilderment in response to these shifting societal patterns.

The proliferation of certain online services has been linked to detrimental effects, including an increase in self-harm and suicide rates. Parents are increasingly concerned about the manipulative tactics employed by tech designers, which hijack their children’s attention, impede their children’s pursuits, and subject them to unrealistic beauty standards. Historically, safeguards were in place to protect children from such influences, as evidenced by regulations governing advertising to children during Saturday morning cartoons. However, the advent of platforms like YouTube for kids has effectively dismantled these protections, leaving an entire generation susceptible to the digital pacifiers that exacerbate discomfort, loneliness, uncertainty, and fear while concurrently stunting their capacity to cope with these emotions autonomously [

52].

The Challenges of Advancing Technology and AI Integration

The rapid advancement of technology poses significant concerns, mainly due to the exponential growth in processing power over the years. For instance, comparing the processing power from the 1960s to today reveals a staggering increase of about a trillion times, far surpassing the rate of improvement observed in other domains, such as automotive technology. Our human physiology and brains have not undergone fundamental changes in this time. As technology evolves, human existence may become increasingly intertwined with advanced hardware and computing systems that operate with goals misaligned with our own. This raises pertinent questions regarding the potential consequences and outcomes of this intersection.

In the contemporary landscape, the ubiquitous presence of technology holds significant implications for society. Integrating artificial intelligence (AI) in corporate behemoths such as Google necessitates critically examining its operational dynamics [

53,

54,

55]. The expansive facilities housing myriad interconnected computers, interwoven with complex algorithms and programs, underscore the scale at which AI operates. These algorithms, as elucidated, are not inherently objective; instead, they are designed to optimise specific definitions of success—commonly, profit. Through machine learning, the computer system incrementally enhances its capabilities to achieve predefined outcomes, albeit with an inherent autonomy that transcends human intervention.

Furthermore, the opaque nature of these systems, understood by only a select few within companies like Facebook and Twitter, contributes to a pervading sense of relinquished control. As a result, individuals find themselves pitted against an AI entity that possesses an intricate understanding of their behaviour. At the same time, their comprehension of the AI remains limited to mundane facets such as cat videos and birthday notifications. This lopsided dynamic calls into question the fairness of such engagement [

56,

57].

When considering the digital landscape, the analogy of Wikipedia can elucidate the issue of personalised content. Analogously, the uniformity of content on Wikipedia represents a unique commonality in the digital sphere. If, however, the platform were to adopt a model whereby each user is presented with a personalised definition in exchange for financial compensation, it would intrude into the user” privacy, effectively leading to the customisation of information based on commercial interests. This hypothetical scenario mirrors the current state of personalised content on various online platforms such as Facebook, YouTube, and Google, where users are exposed to tailored information based on their geographic location and individual preferences. Consequently, individuals with similar social circles may still encounter vastly different content. Ultimately, this implementation results in the fragmentation of reality, akin to 2.7 billion personalised Truman Show [

58], wherein users are confined to their subjective digital realms, similar to the protagonist of The Truman Show who, before the outcome, remained oblivious to the true nature of his environment.

Consider the difference between Wikipedia’s standardised content, a platform for global users, and the social media giant” personalised content delivery systems. Personalised content tailored to individual user characteristics creates a fragmented online experience, with each user living in a s reality. This phenomenon is comparable to 2.7 billion Truman Shows, with commercial interests and algorithms shaping these realities. This prompts questions about the impartiality of the information presented to users. Examples include search engine results and social media news feeds. This highlights the potential impact of personalised content delivery on users’ perceptions and understanding of various user manipulation practices using social media.

11. The Weaponisation of Social Media and Its Real-World Impact

Government weaponisation of social media has raised significant concerns due to its real-world consequences. One notable case is the situation in Myanmar, where the widespread use of Facebook, often pre-loaded onto new phones, has been linked to severe offline harm. A recent investigative report has revealed the platform’s struggle to address hate speech in Myanplatform [

59,

60]. Facebook inadvertently provided the military and other nefarious parties with a means to manipulate public opinion and fuel violence against the Rohingya Muslims, resulting in mass killings, village burnings, mass rapes, and other grave crimes against humanity, forcing 700,000 Muslims to flee the country.

This case underscores the immense power of social media platforms. They can be leveraged to amplify misinformation, conspiracy theories, and hate speech, ultimately leading to real-world harm.

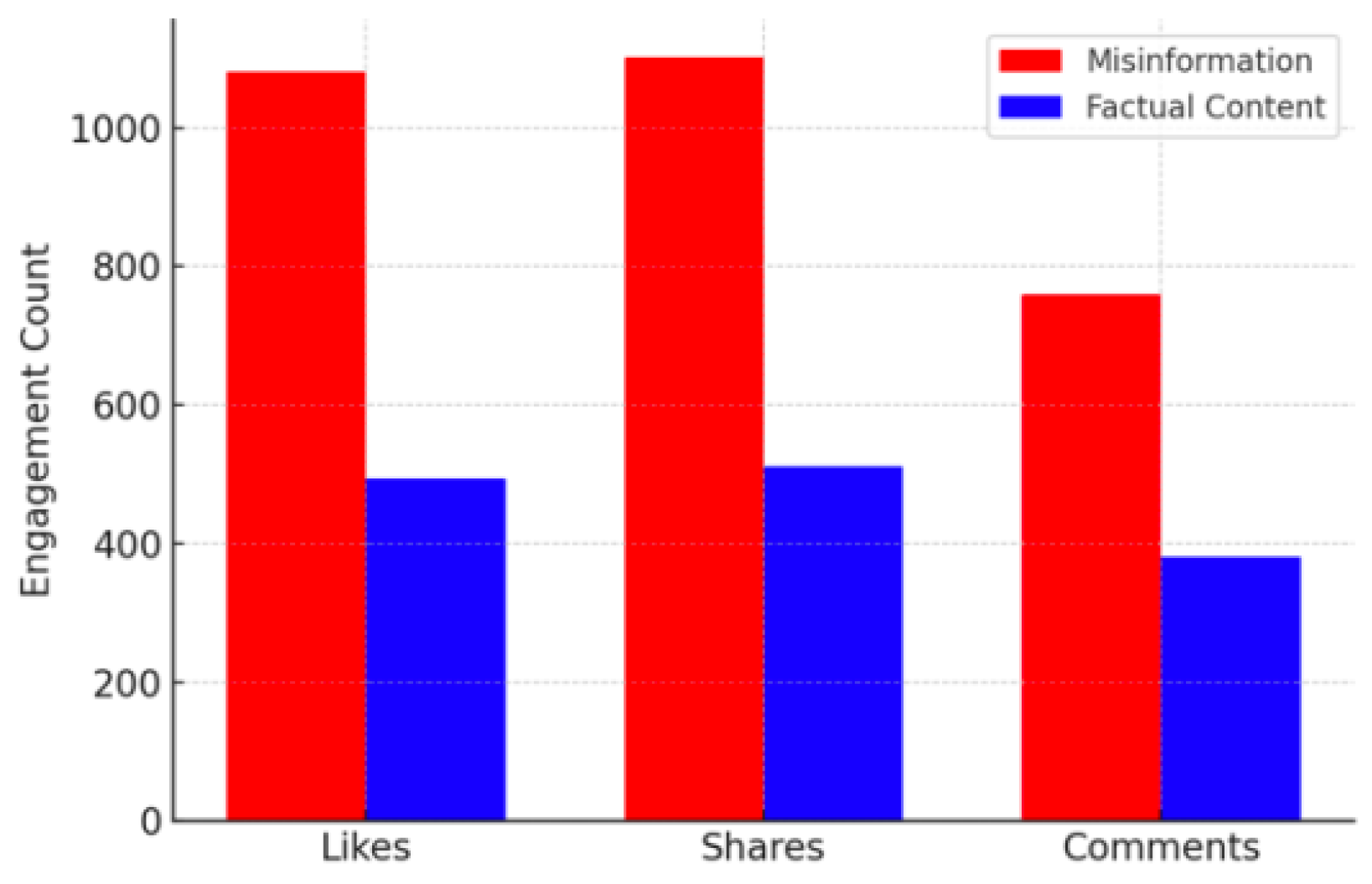

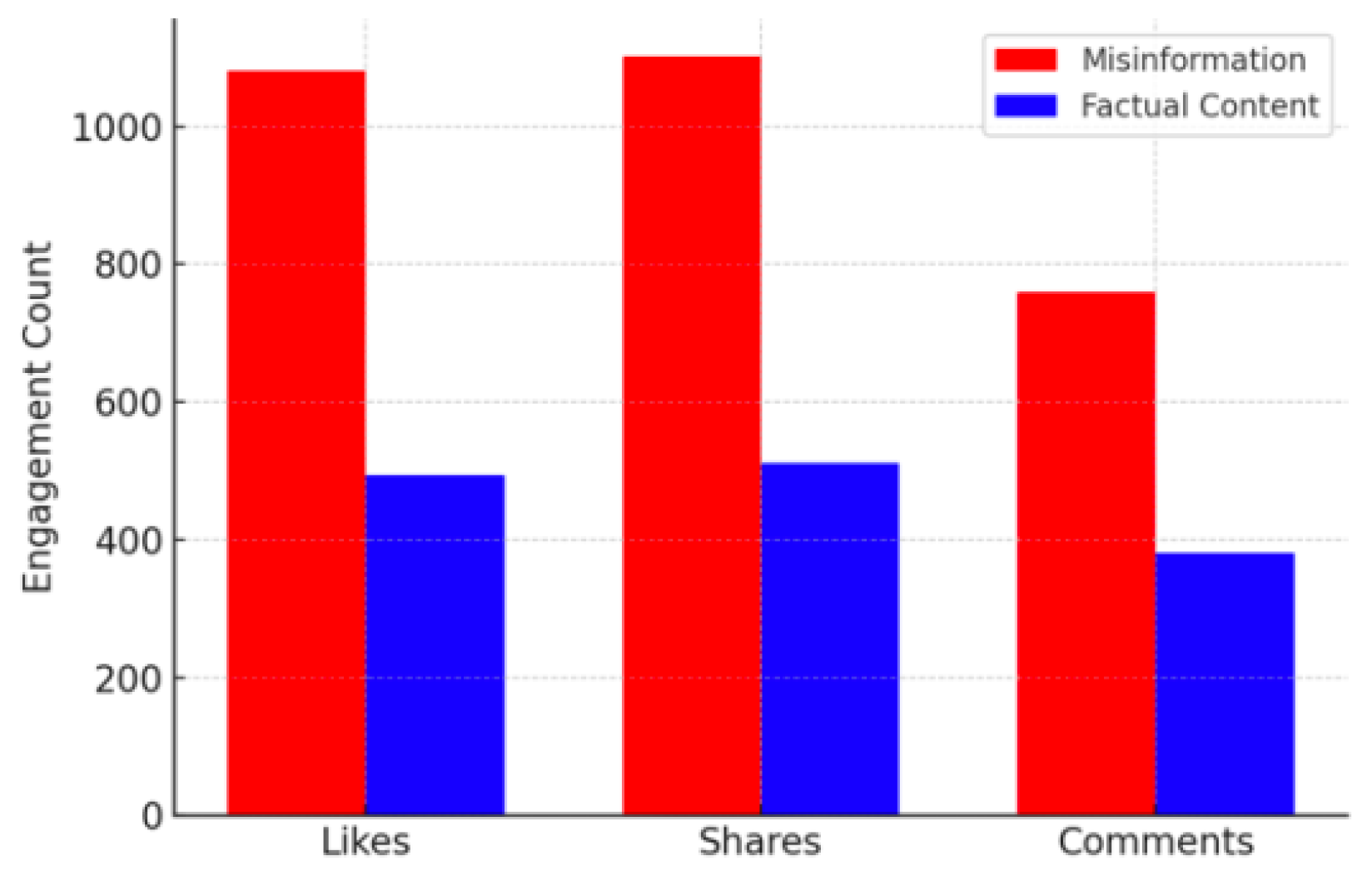

Figure 20 indicates how misinformation consistently outperforms factual content in engagement metrics, highlighting the algorithmic preference for sensationalism over accuracy. The virality of false information presents a significant challenge for content moderation and digital literacy efforts. Thus, unchecked, social media can become a breeding ground for disseminating false narratives, fuelling discord and societal division. This is not limited to Myanmar; various other nations, including the United States, have grappled with weaponising social media to influence public opinion and sway political outcomes.

Figure 16.

Engagement levels: Misinformation vs factual content.

Figure 16.

Engagement levels: Misinformation vs factual content.

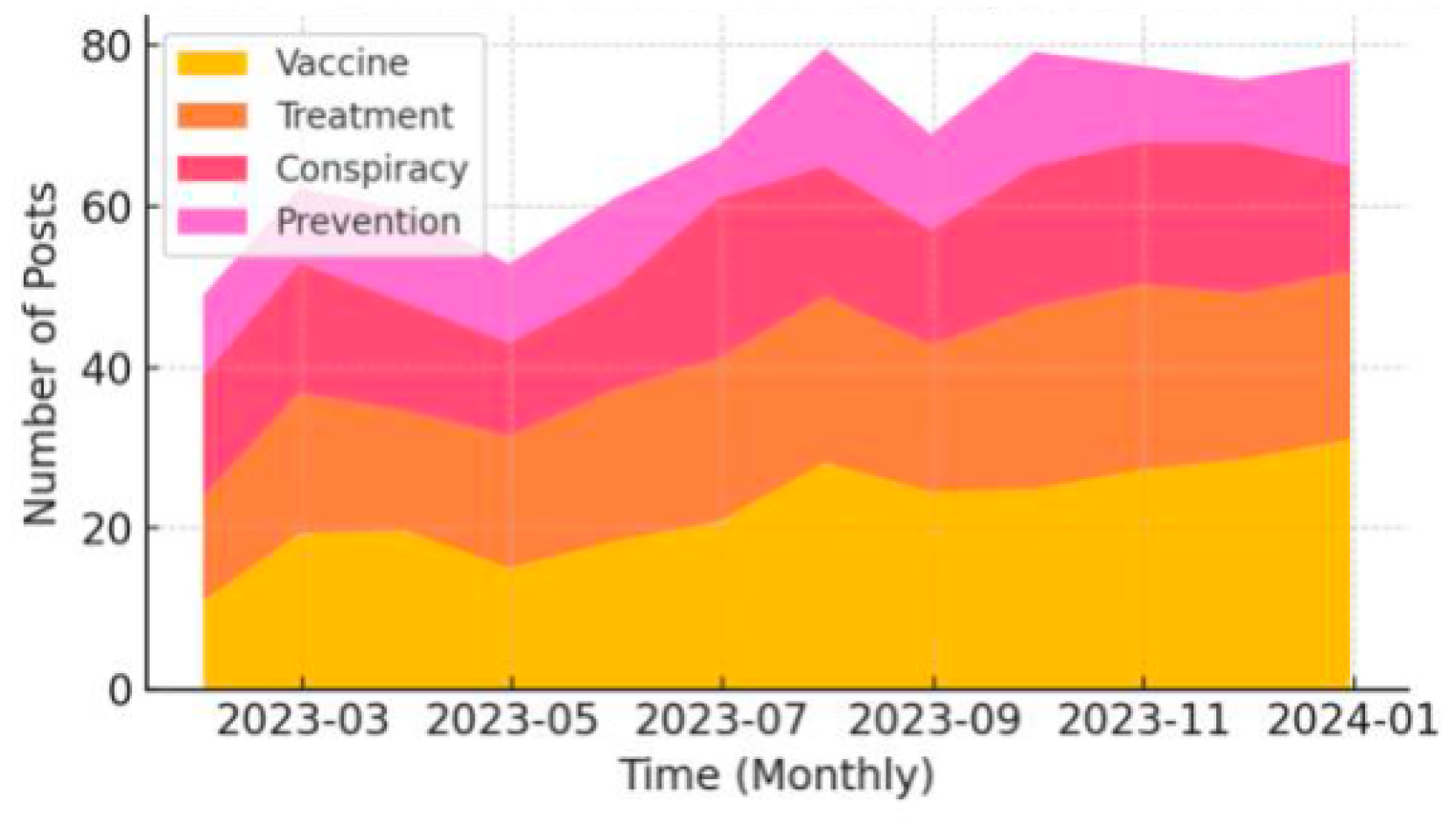

The COVID-19 pandemic saw an unprecedented surge in misinformation, ranging from conspiracy theories to false medical advice (

Figure 17). This trend underscores the need for proactive misinformation mitigation strategies, including real-time fact-checking and platform accountability measures.

The role of social media in the global battle of narratives cannot be overstated. Social media platforms have become a powerful tool for international actors to shape public opinion and influence political outcomes. The ease with which digital manipulation strategies can be deployed on social media makes it challenging for policymakers, military leaders, and intelligence agencies to keep pace and adapt. The ubiquitous nature of information transmission on these platforms has enabled the spread of propaganda, misinformation, and disinformation at an unprecedented scale.

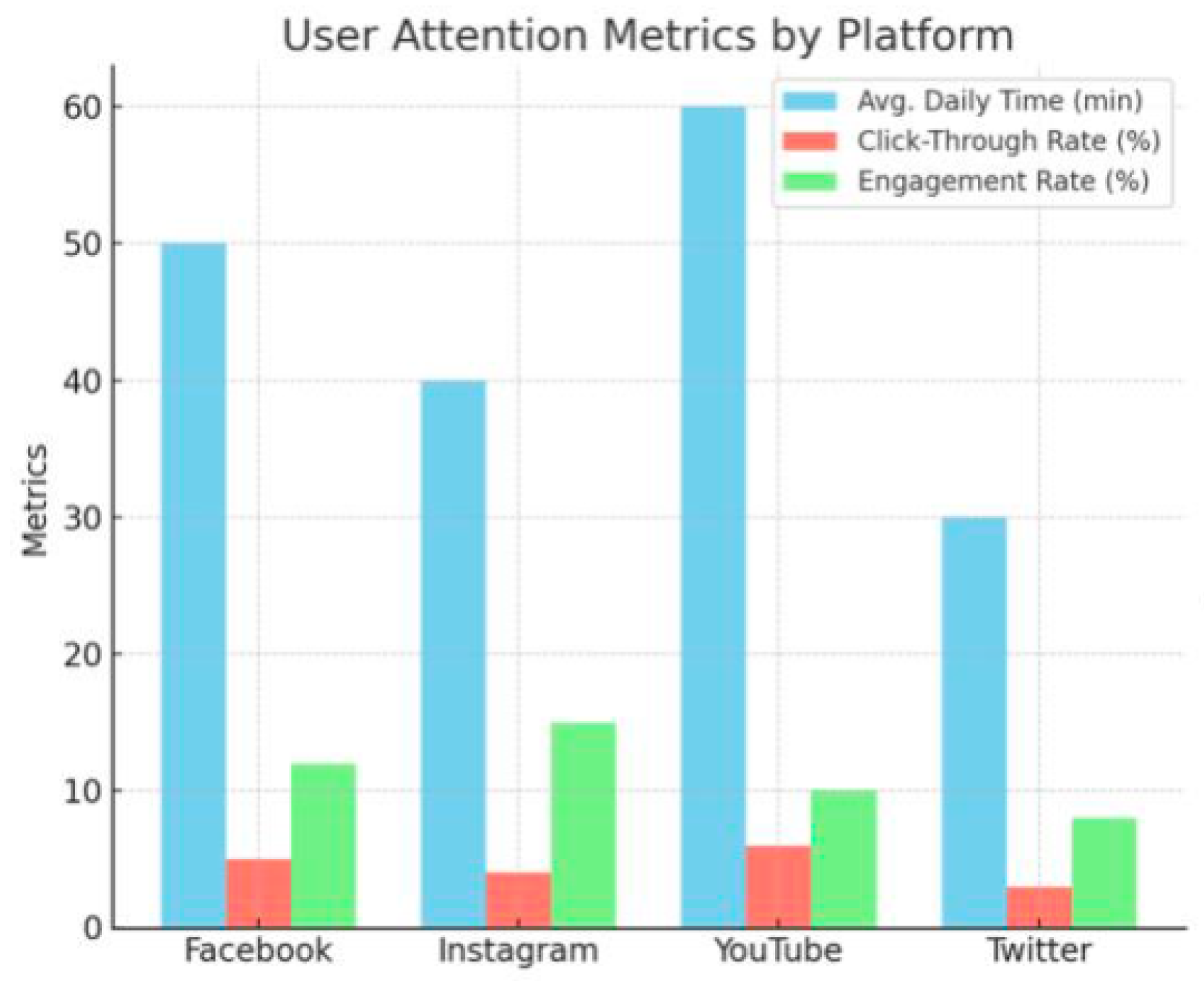

Figure 18 illustrates how different platforms use various engagement tactics to capture and maintain user attention. While short-form content encourages quick interactions, long-form content promotes deeper engagement.

12. The Double-Edged Sword of Modern Technology and Social Media

Customers can summon a car with a button on their smartphones, and within 30 seconds, it arrives to transport them to their desired location; this occurrence embodies a sense of technological magic and is genuinely astounding. No doubt, but the original motive for creating the like button centred on spreading positivity and love in our global community. However, the unforeseen consequences have led to instances of teenage depression stemming from a lack of likes, as well as contributing to political polarisation. It is unlikely that the originators of these features had malicious intent, but the business model presents inherent challenges. Implementing substantial changes risks losing considerable shareholder value and facing legal repercussions, rendering it a formidable task. The core issue lies within the existing financial incentives that drive these enterprises, thus necessitating a realignment of these incentives in any proposed remedy. Addressing digital privacy and the regulation of data collection are critical considerations that warrant legislative attention, mirroring the protective measures in place for other sensitive information. Subsequently, it is apparent that current circumstances predominantly favour safeguarding corporate rights and privileges, diverging from a user-centric focus [

61].

The current state of technology presents a double-edged sword; while it has revolutionised communication, productivity, and access to information, it also poses significant risks that demand immediate attention. The pervasive nature of digital devices and platforms has led to concerns over privacy breaches, cyberbullying, and the decline of face-to-face social interactions. Social media, in particular, has been linked to mental health issues such as anxiety and depression, often exacerbated by the constant comparison with others [

6,

62]. Moreover, the spread of misinformation and the reinforcement of echo chambers through algorithm-driven content curation threaten democratic processes and societal harmony. To address these issues, collective action is imperative. Open conversations about the responsible use of technology and public pressure on tech companies to prioritise ethical practices are crucial. By fostering a culture of accountability and demanding transparency, society can better manage the adverse effects of technology.

13. Practical Steps for Managing Technology’s Influence

The rapid advancement of technology has undoubtedly transformed our lives, but it has also created a myriad of challenges that require our immediate attention. A comprehensive approach involving policymakers, tech companies, and the general public is necessary to address the concerns outlined in the previous sections.

First and foremost, robust regulations and oversight mechanisms must be established to hold tech companies accountable for the consequences of their products and services. Data privacy laws should be strengthened to protect individuals’ personal information from misuse, and clear guidelines should be in place for the collection, storage, and utilisation of user data. Additionally, measures should be taken to address the spread of misinformation and manipulate public opinion through social media platforms.

Another crucial step is for tech companies to prioritise ethical practices and user well-being over financial gain. This may involve rethinking their business models, redesigning algorithms to promote meaningful connections and well-being, and investing in digital literacy initiatives to empower users to navigate the online landscape safely and responsibly.

Ultimately, the responsibility for managing technology’s influence lies with policymakers, tech companies, and individual users. Developing a critical understanding of technology’s impact on our lives, cultivating healthy digital habits, and advocating for positive change can contribute to a more balanced and equitable relationship with technology.

On an individual level, practical steps can be taken to reduce the influence of technology. Uninstalling non-essential apps, turning off notifications, and using alternative tools designed to enhance productivity and well-being can help mitigate the impact of constant digital engagement. Additionally, practising critical information consumption is essential in an era of rampant misinformation. This involves fact-checking sources, diversifying the media consumed, and deliberately seeking out opposing viewpoints to foster a well-rounded perspective [

63]. By engaging with diverse opinions, individuals can break free from the confines of echo chambers and develop a more nuanced understanding of complex issues.

Figure 20.

Engagement levels: Misinformation vs factual content.

Figure 20.

Engagement levels: Misinformation vs factual content.

Furthermore, setting boundaries for technology use, especially for children, is vital. Limiting screen time and encouraging offline activities can support healthier development and prevent dependency on digital devices [

64,

65]. Parents and educators must collaborate to establish guidelines that promote balanced technology use while protecting children’s mental and emotional well-being. Overall, the negative impacts of technology require a multifaceted approach, combining individual responsibility with collective action. By taking personal steps to manage technology use and advocating for systemic changes, we can ensure that technology is a tool for progress rather than a source of harm.

14. Conclusion

Rapid technological advancements have undoubtedly transformed our lives and presented many challenges that demand our attention. While digital technologies can potentially improve development outcomes and lift millions out of poverty, they can also heighten political divisions, undermine democracy, and exacerbate inequality.

A comprehensive approach is necessary to address these concerns. Robust regulations and oversight mechanisms must be established to hold tech companies accountable for the consequences of their products and services. At the same time, tech companies must prioritise ethical practices and user well-being over financial gain, which may involve rethinking their business models and redesigning algorithms.

On an individual level, practical steps can be taken to reduce the influence of technology, such as uninstalling non-essential apps, turning off notifications, and practising critical information consumption. Setting boundaries for technology use, especially for children, is also vital to promoting healthier development and preventing dependency on digital devices.

By taking personal steps to manage technology use and advocating for systemic changes, we can ensure that technology is a tool for progress rather than a source of harm. Through open conversations, public pressure, and collective action, we can strive to create a digital landscape that enhances our well-being and supports the flourishing of human potential.

References

- Bucher, T. (2020, September 1). The right-time web: Theorizing the virologic of algorithmic media. SAGE Publishing, 22, (9), 1699–1714. [CrossRef]

- Epstein, Z. , Sirlin, N., Arechar, A. A., Pennycook, G., & Rand, D. G. (2023, March 3). The social media context interferes with truth discernment. American Association for the Advancement of Science, 9(9). [CrossRef]

- Shao, C. , Ciampaglia, G. L., Varol, O., Flammini, A., & Menczer, F. (2017, July 24). The spread of misinformation by social bots. Cornell University. [CrossRef]

- Lou, X., Flammini, A., & Menczer, F. (2019, July 13). Manipulating the Online Marketplace of Ideas. Cornell University. https://arxiv.org/abs/1907.06130.

- Altuwairiqi, M. , Kostoulas, O., Powell, G., & Ali, R. (2019, January 1). Problematic Attachment to Social Media: Lived Experience and Emotions. Springer Nature, 795–805. [CrossRef]

- Khalaf, A. , Alubied, A. A., Khalaf, A., & Rifaey, A. A. (2023, August 5). The Impact of Social Media on the Mental Health of Adolescents and Young Adults: A Systematic Review. Cureus, Inc. [CrossRef]

- Madan, G. D. (2022, January 1). Understanding misinformation in India: The case for a meaningful regulatory approach for social media platforms. Cornell University. [CrossRef]

- Geeng, C. , Yee, S., & Roesner, F. (2020, ). Fake News on Facebook and Twitter: Investigating How People (Do not) Investigate. [CrossRef]

- Riego, N. C. R. , & Villarba, D. B. (2023, January 1). Utilization of Multinomial Naive Bayes Algorithm and Term Frequency Inverse Document Frequency (TF-IDF Vectorizer) in Checking the Credibility of News Tweet in the Philippines. Cornell University. [CrossRef]

- Cisternas, G. , & Vásquez, J. D. (2022, January 1). Misinformation in Social Media: The Role of Verification Incentives. RELX Group (Netherlands). [CrossRef]

- Cho, M. , Li, A. Y., Furnas, H., & Rohrich, R. J. (2020, July 1). Current Trends in the Use of Social Media by Plastic Surgeons. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 146, (1), 83e–91e. [CrossRef]

- Chartier, C. , Chandawarkar, A., Gould, D. J., & Stevens, W. G. (2020, June 20). Insta-Grated Plastic Surgery Residencies: 2020 Update. Oxford University Press, 41(3), 372–379. [CrossRef]

- King, M. T. (2020, July 2). Say no to bat fried rice: changing the narrative of coronavirus and Chinese food. Taylor & Francis, 28, (3), 237–249. [CrossRef]

- Choi, H. , Mela, C. F., Balseiro, S., & Leary, A. (2020, June 1). Online Display Advertising Markets: A Literature Review and Future Directions. Institute for Operations Research and the Management Sciences, 31, (2), 556–575. [CrossRef]

- Falch, M. (2020, November 26). Surveillance capitalism - a new techno-economic paradigm? [CrossRef]

- Mamlouk, L. , & Segard, O. (2015, February 1). Big Data and Intrusiveness: Marketing Issues. Indian Society for Education and Environment, 8, (S4), 189. [CrossRef]

- Sam, J. S. (2019, December 26). The Age of Surveillance Capitalism: The Fight for a Human Future at the New Frontier of Power. Routledge, 4, (2), 242–244. [CrossRef]

- Zuboff, S. (2015, March 1). Big other: Surveillance Capitalism and the Prospects of an Information Civilization. SAGE Publishing, 30, (1), 75–89. [CrossRef]

- Herrera, J., Berrocal, J., García-Alonso, J., Murillo, J. M., Chen, H., Julien, C., Mäkitalo, N., & Mikkonen, T. (2021, January 1). Personal Data Gentrification. Cornell University. [CrossRef]

- Summers, M. (2020, October 6). Facebook isn’t free: Zero-price companies overcharge consumers with data. Cambridge University Press, 7, (2), 532–556. [CrossRef]

- Nazarov, A. D. (2020, January 1). Impact of Digital Marketing on the Buying Behavior of Consumer. [CrossRef]

- Grinberg, N., Dow, P. A., Adamic, L., & Haamah, M. (2016, May 7). Changes in Engagement Before and After Posting to Facebook. [CrossRef]

- Hodis, M. , Sriramachandramurthy, R., & Sashittal, H. C. (2015, February 24). Interact with me on my terms: a four segment Facebook engagement framework for marketers. Taylor & Francis, 31, (11-12), 1255–1284. [CrossRef]

- Kassa, Y. M. , Cuevas, R., & Cuevas, A. (2018, January 1). A Large-Scale Analysis of Facebook’s User-Base and User Engagement Growth. Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers, 6, 78881. [CrossRef]

- Kooti, F., Subbian, K., Mason, W., Adamic, L., & Lerman, K. (2017, January 1). Understanding Short-term Changes in Online Activity Sessions. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, K. B. , Bouhorma, M., & Ahmed, M. B. (2014, October 25). Age of Big Data and Smart Cities: Privacy Trade-Off. International Journal of Engineering Trends and Technology, 16, (6), 298–304. [CrossRef]

- Vishwanath, A. , Xu, W. W., & Ngoh, Z. (2018, January 13). How people protect their privacy on Facebook: A cost-benefit view. Wiley-Blackwell, 69, (5), 700–709. [CrossRef]

- Kitova, E. , & Melgunova, A. (2019, May 24). The Reflection of the Social Value Hierarchy in the Concepts of Data Protection and Freedom of Information. Ball State University 2019, 8(2), 330–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurkiewicz, C. L. (2018, January 18). Big Data, Big Concerns: Ethics in the Digital Age. Taylor & Francis, 20, (sup1), S46–S59. [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, S. , Chen, Y., Nissim, K., Parkes, D. C., Siek, K. A., & Wilcox, L. (2020, January 1). Modernizing Data Control: Making Personal Digital Data Mutually Beneficial for Citizens and Industry. Cornell University. [CrossRef]

- Burr, C., Taddeo, M., & Floridi, L. (2020, January 13). The Ethics of Digital Well-Being: A Thematic Review. Springer Science+Business Media, 26, (4), 2313–2343. [CrossRef]

- West, S. M. (2017, July 5). Data Capitalism: Redefining the Logics of Surveillance and Privacy. SAGE Publishing, 58, (1), 20–41. [CrossRef]

- Chan-Olmsted, S. M. , & Wolter, L. (2018, January 2). Perceptions and practices of media engagement: A global perspective. Taylor & Francis, 20, (1), 1–24. [CrossRef]

- Chilana, P. K., Holsberry, C., Oliveira, F., & Ko, A. J. (2012, May 5). Designing for a billion users. [CrossRef]

- Qudaih, H. A. Qudaih, H. A., Bawazir, M. A., Usman, S. H., & Ibrahim, J. (2014, April 25). Persuasive Technology Contributions Toward Enhancing Information Security Awareness in an Organization. Seventh Sense Research Group, 10(4), 180–186. [CrossRef]

- Lukyanchikova, E. , Askarbekuly, N., Aslam, H., & Mazzara, M. (2023, May 16). A Case Study on Applications of the Hook Model in Software Products. Software 2023, 2(2), 292–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azer, J. , Blasco-Arcas, L., & Alexander, M. (2023, July 25). Visual Modality of Engagement: Conceptualization, Typology of Forms, and Outcomes. SAGE Publishing, 27, (2), 231–249. [CrossRef]

- Dhir, A. , & Torsheim, T. (2016, October 1). Age and gender differences in photo tagging gratifications. Elsevier BV 2016, 63, 630–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miquel-Ribé, M. (2020, January 1). Dark User Experience: From Manipulation to Deception. Bloomsbury Academic, 40–48. [CrossRef]

- Lee, D., Hosanagar, K., & Nair, H. S. (2018, November 1). Advertising Content and Consumer Engagement on Social Media: Evidence from Facebook. Institute for Operations Research and the Management Sciences, 64, (11), 5105–5131. [CrossRef]

- Aria, R. , Archer, N., Khanlari, M., & Shah, B. (2023, March 30). Influential Factors in the Design and Development of a Sustainable Web3/Metaverse and Its Applications. Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute, 15(4), 131-131. [CrossRef]

- Lithoxoidou, E. E., Paliokas, I., Gotsos, I., Krinidis, S., Tsakiris, A., Votis, K., & Tzovaras, D. (2018, June 26). A Gamification Engine Architecture for Enhancing Behavioral Change Support Systems. [CrossRef]

- Pasca, M. G. , Renzi, M. F., Pietro, L. D., & Mugion, R. G. (2021, June 18). Gamification in tourism and hospitality research in the era of digital platforms: A systematic literature review. Emerald Publishing Limited, 31(5), 691-737. [CrossRef]

- Houghton, D. , Pressey, A. D., & Istanbulluoglu, D. (2020, March 1). Who needs social networking? An empirical enquiry into the capability of Facebook to meet human needs and satisfaction with life. Elsevier BV, 104, 106153-106153. [CrossRef]

- Agozie, D. Q. , & Nat, M. (2022, August 10). Do communication content functions drive engagement among interest group audiences? An analysis of organisational communication on Twitter. Palgrave Macmillan, 9(1). [CrossRef]

- Wang, M. , Chang, W., Kuo, K., & Tsai, K. (2023, August 11). Analyzing image-based political propaganda in referendum campaigns: from elements to strategies. Springer Nature, 12(1). [CrossRef]

- Kim, S. , Roe, D. G., Choi, Y. Y., Woo, H., Park, J., Lee, J. I., Choi, Y., Jo, S. B., Kang, M. S., Song, Y. J., Jeong, S., & Cho, J. H. (2021, April 9). Artificial stimulus-response system capable of conscious response. American Association for the Advancement of Science, 7(15). [CrossRef]

- Shih, C. , Naughton, N., Halder, U., Chang, H., Kim, S., Gillette, R., Mehta, P. G., & Gazzola, M. (2023, September 1). Hierarchical Control and Learning of a Foraging CyberOctopus. Wiley, 5(9). [CrossRef]

- Steinhoff, A. , Ribeaud, D., Kupferschmid, S., Raible-Destan, N., Quednow, B. B., Hepp, U., Eisner, M., & Shanahan, L. (2020, June 22). Self-injury from early adolescence to early adulthood: age-related course, recurrence, and services use in males and females from the community. Springer Science+Business Media, 30(6), 937–951. [CrossRef]

- Spiller, H. A. , Ackerman, J., Spiller, N., & Casavant, M. J. (2019, July 1). Sex- and Age-specific Increases in Suicide Attempts by Self-Poisoning in the United States among Youth and Young Adults from 2000 to 2018. Elsevier BV, 210, 201–208. [CrossRef]

- Nesi, J. (2020, March 1). The Impact of Social Media on Youth Mental Health. North Carolina Medical Journal, 81(2), 116–121. [CrossRef]

- Alshamrani, S. S., Abusnaina, A., & Mohaisen, A. (2020, November 1). Hiding in Plain Sight: A Measurement and Analysis of Kids’ Exposure to Malicious URLs on YouTube. [CrossRef]

- Hussein, B. R. , Halimu, C., & Siddique, M. T. (2021, January 1). The Future of Artificial Intelligence and its Social, Economic and Ethical Consequences. Cornell University. [CrossRef]

- Khakurel, J. , Penzenstadler, B., Porras, J., Knutas, A., & Zhang, W. (2018, November 3). The Rise of Artificial Intelligence under the Lens of Sustainability. Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute, 6(4), 100-100. [CrossRef]

- Vinuesa, R. , Azizpour, H., Leite, I., Balaam, M., Dignum, V., Domisch, S., Felländer, A., Langhans, S. D., Tegmark, M., & Nerini, F. F. (2020, January 13). The role of artificial intelligence in achieving the Sustainable Development Goals. Nature Portfolio, 11(1). [CrossRef]

- Portacolone, E. , Halpern, J., Luxenberg, J. S., Harrison, K. L., & Covinsky, K. E. (2020, July 21). Ethical Issues Raised by the Introduction of Artificial Companions to Older Adults with Cognitive Impairment: A Call for Interdisciplinary Collaborations. IOS Press, 76(2), 445–455. [CrossRef]

- Shank, D. B. , & Gott, A. (2019, August 1). People’s self-reported encounters of Perceiving Mind in Artificial Intelligence. Elsevier BV, 25, 104220–104220. [CrossRef]

- Xu, C. , Li, J., Abdelzaher, T., Ji, H., Szymański, B. K., & Dellaverson, J. (2020, January 1). The Paradox of Information Access: On Modeling Social-Media-Induced Polarization. Cornell University. [CrossRef]

- Ridout, B. , McKay, M., Amon, K. L., Campbell, A., Wiskin, A. J., Du, P., Mar, T., & Nilsen, A. R. (2020, December 1). Social Media Use by Young People Living in Conflict-Affected Regions of Myanmar. Mary Ann Liebert, Inc., 23(12), 876–888. [CrossRef]

- Calderón, F. , Balani, N., Taylor, J., Peignon, M., Huang, Y., & Chen, Y. (2021, November 25). Linguistic Patterns for Code Word Resilient Hate Speech Identification. Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute 2021, 21(23), 7859–7859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howe, E. G. , & Elenberg, F. (2020, October 1). Ethical Challenges Posed by Big Data. Journal of Ethics, 17, 24–30.

- Ulvi, O. , Karamehić-Muratović, A., Baghbanzadeh, M., Bashir, A., Smith, J., & Haque, U. (2022, January 11). Social Media Use and Mental Health: A Global Analysis. Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute, 3(1), 11–25. [CrossRef]

- Kozyreva, A. , Wineburg, S., Lewandowsky, S., & Hertwig, R. (2022, November 8). Critical Ignoring as a Core Competence for Digital Citizens. SAGE Publishing 2022, 32(1), 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J. (2016, October 1). Early Learning and Educational Technology Policy Brief. http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED571882.pdf.

- Magis-Weinberg, L. , & Berger, E. (2020, June 19). Mind Games: Technology and the Developing Teenage Brain. Frontiers Media, 8. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).