1. Introduction

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), diabetes is a chronic condition that occurs either when the pancreas does not produce enough insulin or when the body cannot effectively use the insulin it produces. In 2019, diabetes was the direct cause of 1.5 million deaths, with 48% of these deaths occurring before the age of 70. Type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM), in particular, is characterized by insufficient insulin production, requiring daily insulin administration. In 2017, there were 9 million people with T1DM globally, with the majority living in high-income countries. The exact cause and prevention methods for T1DM remain unknown [

1].

The importance of exercise in the prevention and management of diabetes has been extensively documented in literature. However, for individuals with T1DM, exercise can pose risks, such as hypoglycemia. Another critical factor influencing diabetes management is an individual's psychological state. Increased stress can negatively impact glycemic control and overall disease management in people with diabetes [

2]. Stress triggers the release of hormones like cortisol and adrenaline, which impair insulin effectiveness, often resulting in hyperglycemia [

3]. Additionally, blood glucose levels and mood are closely interconnected, with elevated glucose levels adversely affecting mood [

4]. According to Van Tilburg et al. (2001), subclinical depressive moods significantly impact glycemic control in individuals withT1DM. Hence, improved mood may positively influence diabetes management [

5]. Another systematic review and meta-analysis supports that engaging regularly in exercise can improve health related quality of life and consequently glycemic control in patients with T2DM [

6].

Enjoyment is also a crucial factor in promoting adherence to exercise programs [

7]. Patients with T1DM experienced improved quality of life, heightened motivation to exercise, and enhanced enjoyment—key contributors to psychological well-being—after participating in a 6-week exercise program [

8]. Intrinsic motivation plays a vital role in participation and commitment to exercise programs [

9]. Notably, enjoyment and intrinsic motivation for exercise are strongly linked; when individuals find an activity enjoyable, their intrinsic motivation to engage in it increases [

10].

The use of Virtual Reality (VR) is increasingly being incorporated into the management of diabetes, particularly in education, prevention, and treatment strategies [

11]. VR-based education programs are considered powerful tools for promoting self-management of diabetes due to their immersive learning experiences and enhanced communication with patients [

12]. Studies have shown that VR interventions effectively reduce pain and anxiety while improving glycemic control, adherence to treatment protocols, and satisfaction in children with T1DM [

13]. The improvements in balance and fall prevention were supported by a systematic review and meta-analysis, but the findings indicated no significant reduction in glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) levels [

14]. It is also important to be mentioned that VR exercise can be an attractive tool that decreases dyspnea symptoms and can enhance performance during exercise, and consequently can increase exercise engagement in patients [

15]. These results suggest that while VR interventions offer numerous psychological and physical benefits, their direct impact on long-term glycemic markers may require further investigation.

Research on VR exercise in diabetes management is still in its early stages. VR has shown promising results among patients with type 2 diabetes, demonstrating high adherence to exercise programs and improving diabetes-related factors. For instance, VR exercise programs can enhance exercise outcomes while reducing the risk of falls in type 2 diabetes patients [

16]. According to Lee et al. (2023), such interventions can positively affect blood glucose levels, muscle mass, physical activity, and glycemic control [

17]. Furthermore, another study indicated that physical activity levels significantly increased after participating in a VR-based exercise program [

18]. For T1DM, the available research is even more limited. Preliminary findings suggest that video games and VR environments are being explored for T1DM education and management. These tools have proven to be safe, engaging, and effective in fostering confidence in diabetes management and promoting positive behavior changes [

19,

20].

This study current study aims to explore the effects of VR exercise on biological and psychological parameters in individuals with T1DM, comparing these effects with traditional exercise. It also evaluates the acceptability, usability, intention for future use, and preference for a VR-based exercise system.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Setting

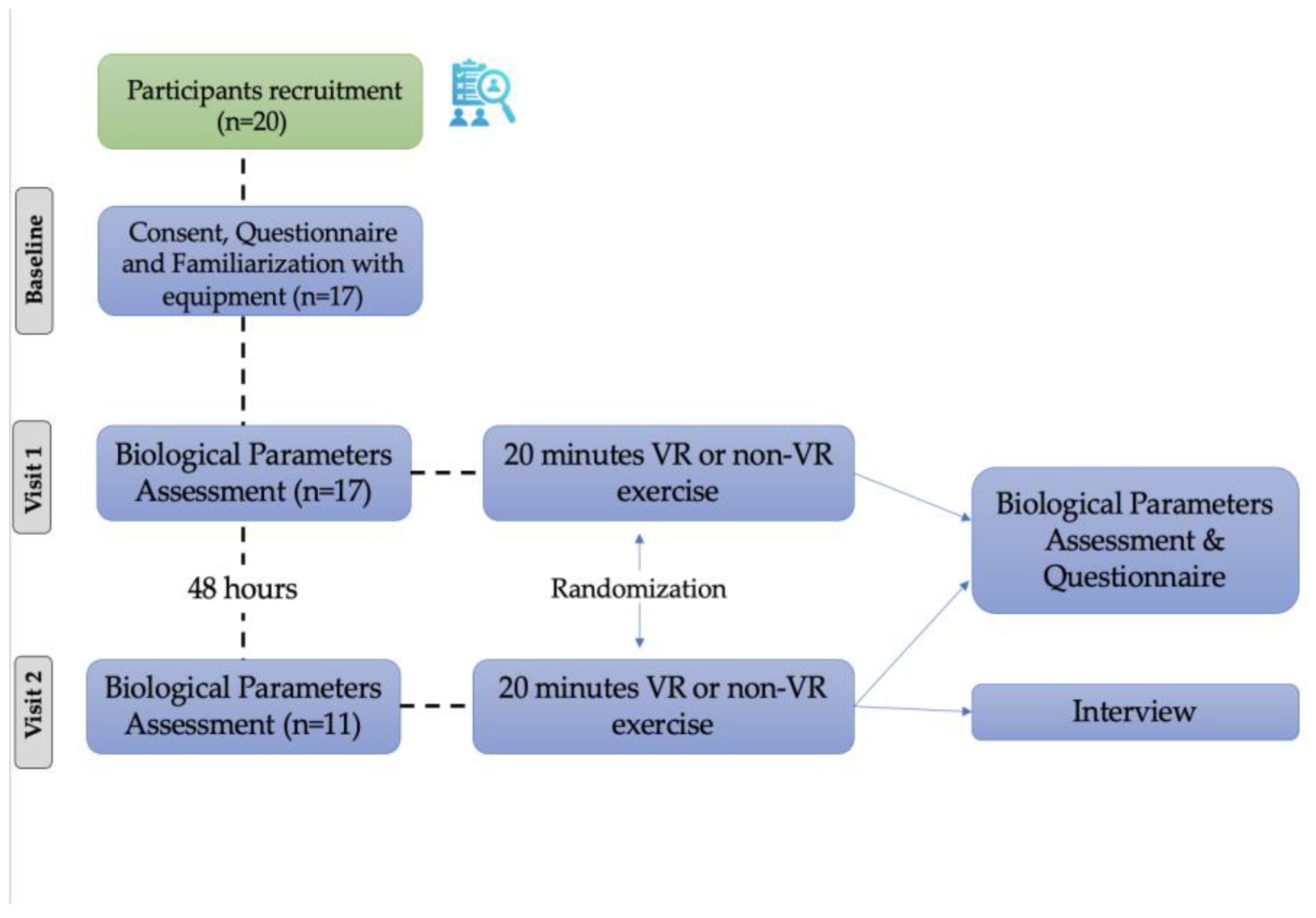

In our study, 11 patients with Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus (T1DM), participated (

Figure 1). The participants (male n=6; age=31.73 ± 9.65 years; body mass index = 24.8±2.7 kg/m

2; tertiary education = 81.8%; self-reported physical activity = 81.8%; frequency of physical activity = 9.1% two times per week, 45.5% three times per week, 18.2% four times per week, and 9.1% six times per week; exercising for: 45-min = 36.4%, 60-min = 18.2%, 90-min = 27.3%) were recruited by the Endocrinology clinic of the University Hospital of Larissa and the study was conducted at the General University Hospital of Larissa from October 2022 to February 2023. The study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of the University of Thessaly (1829/13.10.2021) and all participants gave written consent in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration on Human Research Participation [

21].

Inclusion criteria: age between ≥20 and ≤45 years and waist circumference less than 1.05 m. Exclusion criteria: wearing glasses, history of COVID-19 infection and hospitalization [

15], contraindications to exercise, including physical limitations such as neurological, orthopedic, cognitive, or psychiatric problems [

22].

2.2. Data Collection

This study employed a randomized crossover trial design, consisting of two exercise trials performed on a cycle ergometer. In the VR trial, participants cycled while wearing a VR headset and using the VR exercise App for Dementia and Alzheimer’s patients (VRADA), following the methodology outlined in previous studies [

15,

22,

23,

24]. Version 4.1 of the VRADA app was used for this study, excluding the cognitive tasks. The second trial involved traditional cycling on the cycle ergometer without the VR-system. The two trials were conducted 48 hours apart, more specifically, the experimental procedures were executed every Tuesday and Thursday. All participants completed the first questionnaire, in the first visit, 30 minutes prior VR or non-VR trial which included questions about demographic characteristics, use of technology, anxiety and depression levels (Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale questionnaire, [

25,

26]), sleep quality (Pittsburg Sleep Quality Index- PSQI, [

27,

28]), quality of life (12-item Short Form Survey (SF-12), [

29]) and mood (Profile of Mood States (POMS)- [

30,

31]). In the second visit, they completed the mood questionnaire (Profile of Mood States (POMS)- [

30,

31]) 30 minutes prior VR or non-VR trial. After each trial, all participants completed questionnaires about mood (POMS – [

30,

31]), self-efficacy and self-efficacy expectations [

32,

33], interest/enjoyment (IMI- [

34,

35]) and attitudes [

36]. Those who exercised in VR environment answered also questionnaires about personal innovativeness [

36], usability [

37], VR equipment satisfaction [

38] and acceptance: perceived enjoyment [

39] and intention for future use [

39,

40]. At the end of the last visit, participants also completed a questionnaire about preference regarding the two types of exercise they experienced and answered in a semi-structured interview. Prior to completed the questionnaires, anthropometric characteristics were measured using standard medical equipment and Δchest, (i.e. the difference between the chest circumference at maximum inhalation and exhalation), waist-hip ratio and neck circumference were calculated [

41].

Figure 2.

VR exercise system.

Figure 2.

VR exercise system.

2.3. Experimental Protocol

In the first visit, participants were informed about the study's objectives, signed the consent form, encouraged to ask questions and answered the first questionnaire. Then, participants adjusted their position on the cycle ergometer and those who exercised first with the VR application, familiarized themselves with the VR system equipment. They received detailed instructions on the procedure and equipment use and were encouraged to ask questions. After that, biological parameters were assessed. A 20-minute low-speed (15–20 km/h

-1) trial on the cycle ergometer followed. Before and after each trial heart rate (chest strap sensor, Polar, Kempele, Finland) and blood pressure (manual sphygmomanometer BP, Mac, Nagoya, Japan), blood glucose (using a device placed on the patient's arm that provides glucose readings via smartphone scanning, Freestyle Libre), dyspnea and leg fatigue (Borg CR-10 scale, [

42]) were recorded. Mean arterial blood pressure (MAP) was calculated according to equation [

43] with the following: MAP

(mmHg) =

.

The VR exercise system was selected because it was hypothesized to reduce stress, which could potentially lower blood glucose levels, enhance motivation for engaging in exercise, and provide a safe and controlled approach to managing glucose levels during exercise.

The environment provided optimal conditions for facilitating exercise. The temperature was 21 ± 1°C, and the relative humidity was maintained at 48 ± 5%. The space was quiet, with noise levels kept below 20 decibels. Adequate ventilation was provided, and participants exercised without the use of protective face masks, allowing for natural breathing and comfort. The lighting was sufficient, further supporting a conducive exercise environment. The intervention was delivered by a researcher specializing in exercise and a doctor with expertise in diabetes, ensuring proper guidance and safety throughout the study. No modifications or adaptations were made for any participant, as they were not deemed necessary. After the trial, all participants completed questionnaires.

After 48 hours (second visit), before starting the trial, participants completed a questionnaire. Then, as in the first visit, biological parameters were assessed pre and post the 20-minute trial. Finally, after the trial participants filled the questionnaire depending on the exercise condition performed and replied in the semi-structured interview. All of them were randomized to determine the order in which they would complete trials.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

A power of 85% and confidence interval of 95% were adopted, with an estimated value for a type I error of 5% for the sample size calculation in this study. A value for 17 patients was obtained. However, since this is a novel combined interventional approach, we recruited 20 patients. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to assess the normality of the data, determining whether parametric or non-parametric statistical analyses were appropriate. All data are presented as means, SD, medians and percentages. The Independent-samples t-test or non-parametric Mann-Whitney U test, Paired samples t-test or Wilcoxon Signed Rank test and Correlation analysis (Pearson or Spearman) were conducted. Cohen's d was calculated from the mean difference between groups (M1 and M2), and by the pooled SD:

Cohen's d= and SDpooled=.

For all tests, a p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. The IBM SPSS 21 statistical package (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used for all statistical analyses.

3. Results

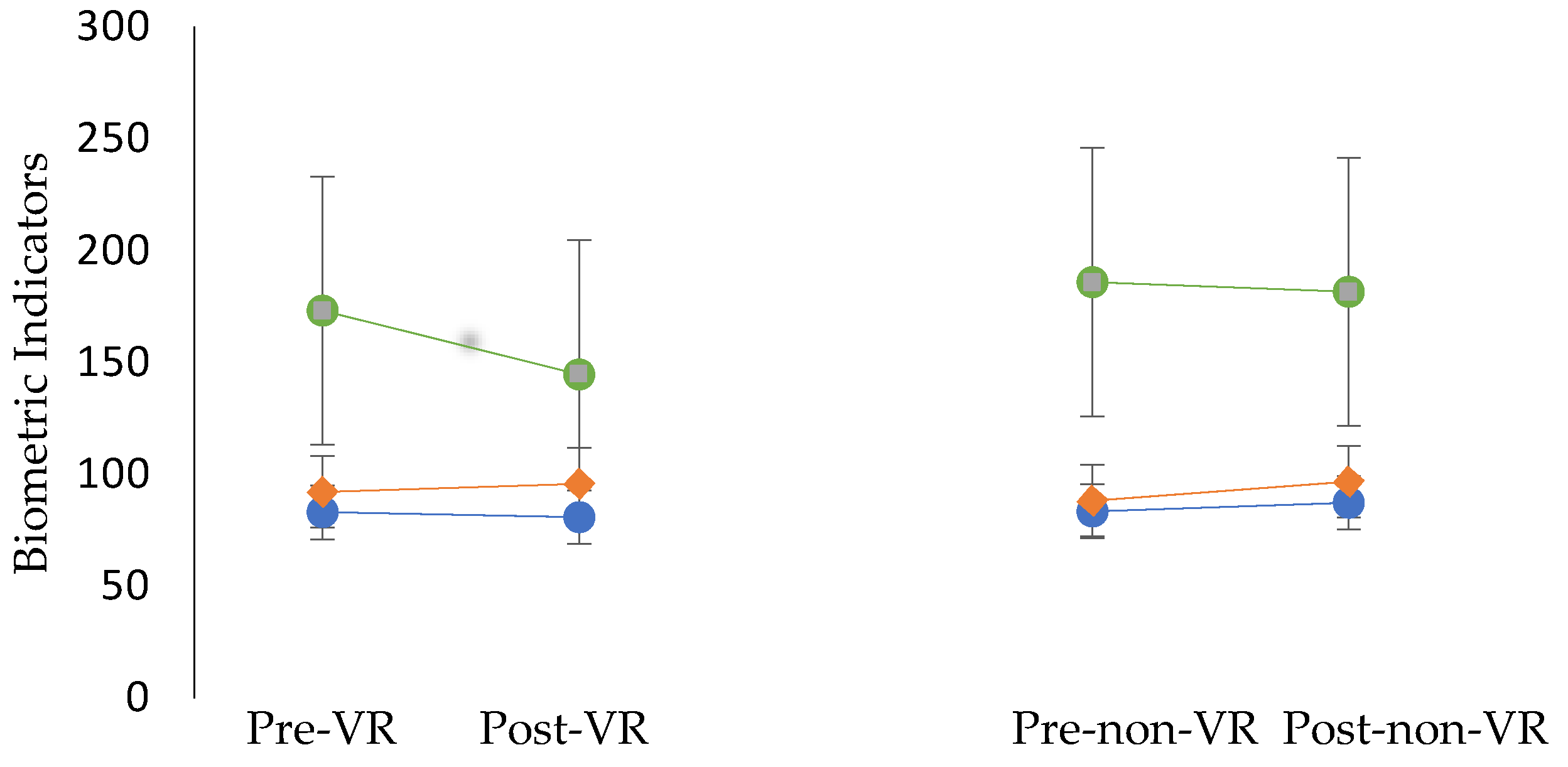

Results didn’t show statistically significant differences in the changes (baseline and after trial) for heart rate, blood glucose and mean arterial pressure in two trials. Results are presented in

Table 1 and

Figure 3. Additionally, no statistically significant differences were found in the medians of variables of dyspnea (pre-VR: 0.1±0.3; post-VR: 0.1±0.3; Pre-non-VR: 0.1±0.3; post non-VR: 0.1±0.3), leg fatigue (pre-VR: .18±.60, post VR: .27±.65, Pre-non-VR: 0.3±0.7, post non-VR: 0.2±0.6). According to the correlation analysis, the chest expansion had a medium negative correlation (p<0.05) with glucose levels post-non-VR trial. Independent samples t-test was conducted between Δchest and blood glucose t(

9)=-2.287, p=0.024.

In POMS questionnaire appeared that there was a statistically significant difference in the participants' median of mood scores before and after the trial. The results showed a statistically significant difference (Z = -0.774, p<0.05) after the VR-based trial with Cohen’s d 0.54. Specifically, the participants' median mood score increased following the VR trial (Median = 63) compared to the baseline measurement (Median = 61). Therefore, it can be concluded that exercising in the virtual environment led to an improvement in mood. However, no statistically significant difference was found in mood when participants exercised without the VR system (p =0.439, Cohen’s d=-0.31).

Self-efficacy and self-efficacy expectations were assessed after each trial, but no statistically significant differences were found in self-efficacy (p = 0.869, Cohen’s d= 0.05) or self-efficacy expectations (p=0.399, Cohen’s d= 0.40) between the two trials.

Interest/enjoyment was evaluated after each trial. The results revealed statistically significant differences (U = 17, p <0.001). Participants reported higher interest/enjoyment scores after the VR trial, Means and Standard Deviations are presented in Table 3.

It was investigated whether there was a statistically significant difference in participants' median preference between the two trials. The results indicated statistically significant differences (Z = -2.836, p<0.05) with median for preference for VR =5 and for non-VR =1.

Attitudes towards exercise were assessed after each trial and no statistically significant differences were observed in their attitudes (p =0.220) between the two trials.

Personal innovativeness, perceived enjoyment, intention for future use, usability, and VR equipment satisfaction were assessed after the VR trial. High scores were recorded across all variables, as presented in

Table 2.

Semi-Structured Interview

The semi-structured interview included questions regarding participants’ emotions, expectations, and perceptions of the usability and tolerability of the VRADA system. Most of the participants reported that they would use this VR system for exercise, did not experience any difficulties, and required no extra time to understand how it works. Most participants felt a sense of presence and control, although they remarked that the virtual environment appeared artificial. None of them reported feelings of discomfort, and only one individual mentioned experiencing distraction during the experience. Participants described the VR exercise system as enjoyable, motivating to engage in physical activity, and effective in making time pass more quickly. However, a small percentage indicated that they would not want to use this system for regular exercise. Finally, participants suggested that young people, individuals unable to exercise outdoors, and those who do not typically enjoy exercise would find this system particularly beneficial.

4. Discussion

The aim of this study was to investigate the effects of VR exercise on biological and psychological parameters in individuals T1DM, compared with traditional exercise, and to assess their acceptance, intention for future use, usability, and preference. Our findings provide insights into the impact of the VR exercise system on participants' biological parameters and mood compared to traditional exercise. As the results of our previous studies revealed, VR-based exercise is well accepted, user-friendly and offers positive benefits in diverse populations [

15,

22,

23]. Other researchers indicate that VR interventions are effective in alleviating pain and anxiety, enhancing glycemic control, promoting adherence to treatment protocols, and increasing satisfaction among children with T1DM. It is also supported that VR interventions can have a positive impact on blood glucose levels, muscle mass, physical activity, and overall glycemic control [

13]. Similarly, Senior et al. (2016) reported a significant increase in physical activity levels following participation in a VR-based exercise program [

18]. Moreover, a recent study by Elsholz, Pham, and Zarnekow (2025) explored the taxonomy of research and commercial VR exercise applications, highlighting the differing priorities of each domain. Research applications often focus on scientific precision and skill development under controlled conditions, whereas commercial applications emphasize motivation, fun, and competitiveness, catering to a broader audience. This distinction is crucial for designing VR interventions that not only target psychological and biological outcomes in T1DM patients but also ensure long-term engagement and adherence [

44].

As we expected, positive results were found in participants’ acceptance and usability of the VR exercise system, as well as in their preference for this type of exercise, supporting the potential of this approach as a complementary tool in T1DM management. Our results showed a decrease in blood glucose levels after VR exercise compared to typical cycling. In 20 minutes of VR exercise, there was an 8% reduction. It is well known that during aerobic exercise, glucose uptake by muscles is increased [

45]. Additionally, previous studies have shown that increased stress raises blood glucose levels and leads to poor glucose control [

46]. VR exercise provided an enjoyable activity in a pleasant environment, which helped reduce stress and, consequently, led to a greater reduction in glucose levels compared to regular exercise. According to Lee et al. (2023), a VR-based exercise program can positively affect glucose control in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) [

17]. A two-week VR exercise program consisting of 30-minute sessions at an intensity of 65-70% of maximum heart rate produced effects similar to running, with fewer hypoglycemic episodes in T1DM patients [

47]. However, a systematic review and meta-analysis concluded that longer-duration VR exercise programs did not show statistically significant improvements in glycated hemoglobin in diabetic patients [

14]. There are few studies in the literature that evaluate the immediate effects of VR exercise compared to traditional exercise on biometric parameters. One study found that biological responses to exercise stimuli were similar in both exercise trials when conducted with the same duration and intensity [

48], consistent with the findings of our study. However, the decrease in glucose levels was much lower in the non-VR condition. Nevertheless, a negative correlation was found between Δchest (cut off = 7 cm) and blood glucose after non-VR (difference 7%). This finding provides insight that physical fitness influences the change in glucose after exercise [

49]. Additionally, patients who had a greater Δchest had lower blood glucose levels. However, physical fitness did not have as significant impact as the improvement in mood and stress reduction from the exercise, resulting in a less pronounced change in glucose levels [

50,

51].

This finding is further supported by the statistically significant improvement in participants' mood following exercise in a virtual environment (Z = -0.774, p<0.05), while no significant change was observed after engaging in traditional exercise (p=0.44). Similar results were found regarding participants' interest/enjoyment (U = 17, p<0.01) and preference for VR-based exercise (Z = -2.836, p<0.05). The combination of exercise and VR enhances enjoyment, boosts energy, and reduces fatigue, as supported by other studies [

52]. According to Plante et al. (2003) using VR without exercise increased fatigue and tension (approximately 60%), lowering energy levels (approximately 7%) [

52]. In agreement with this, Gomes et al. (2021) observed that participants found VR gaming exercises more enjoyable than running [

48]. Mood improvements following VR exercise compared to traditional cycling are also supported by Ochi et al. (2024), who concluded that this type of exercise could enhance well-being across different populations [

53]. Intrinsic motivation plays a key role in exercise participation and adherence [

9]. The strong link between enjoyment and intrinsic motivation suggests that when people enjoy exercising, their motivation to continue increases [

10]. However, another study comparing VR cycling with outdoor cycling reported that while VR exercise positively influenced engagement and physiological responses, outdoor cycling provided greater benefits in motivation, enjoyment, and intention to adhere to exercise [

54].

Patients with T1DM, in addition to the inability to produce insulin, are at risk for developing cardiovascular diseases, as hyperglycemia and insulin deficiency are associated with strain on the cardiovascular system. Changes in MAP are influenced by cardiac output and systemic vascular resistance. Additionally, the autonomous nervous system plays a crucial role in regulating MAP. When MAP is elevated, parasympathetic activity increases, which leads to a reduction in cardiac output. Conversely, when MAP is low, sympathetic tone increases, resulting in an increase in cardiac output and systemic vascular resistance. Increased sympathetic tone also occurs during exercise and periods of psychological stress [

43]. The autonomous nervous system plays a critical role in the body's response to stress. Stress reduces parasympathetic tone and increases sympathetic activity, leading to an elevated heart rate, blood pressure, and the release of hormones such as cortisol. Reduced parasympathetic activity negatively affects the regulation of the vagus nerve, which is important for heart rate variability and recovery. Long-term, this can impact cardiovascular health. Strengthening parasympathetic tone through exercise or relaxation techniques can help mitigate these effects [

55]. According to our results, the MAP did not show significant changes overall; however, it was observed that in the non-VR trial, there was a greater increase in MAP with a 9.6% rise. This phenomenon can be attributed to the fact that during VR exercise, stress was reduced, leading to a lower sympathetic tone, and consequently, a smaller change in MAP with a 3.9% rise. This is significant because during this form of exercise, there is a reduced need for blood circulation from an already burdened cardiovascular system due to the disease [

56].

Finally, participants scored highly in personal innovativeness, indicating a preference for experimenting with new technologies, which likely contributed to the high scores for perceived enjoyment and future use intention. Participants also rated the usability and system equipment highly. VR system usability is suggested to enhance acceptance and engagement [

57]. Moreover, enjoyment directly correlates with adherence to exercise programs, and VR can be used as a tool to improve adherence [

58]. The semi-structured interviews yielded encouraging results regarding participants' experiences with the VR system. The reported sense of presence in the virtual world could lead to changes in attitudes toward this exercise modality and increased enjoyment. Positive attitudes can enhance the intention for future use [

59].

Strengths and Limitations of the Study

To the best of our knowledge, no studies have assessed the biological and psychological factors in individuals with T1DM while comparing VR-based exercise to non-VR exercise. Based on our results, it appears that exercise performed in a pleasant environment can have a positive impact on both psychological and biological factors in individuals with T1DM. Therefore, we recommend the inclusion of outdoor activities, VR exercise, or the integration of new technologies into their exercise programs to enhance both their physical and psychological well-being.

Despite the encouraging results, this study has several limitations that should be mentioned. First, the small sample size limits the generalizability of the findings and the statistical power to detect potential differences in biological parameters. There were several dropouts, accounting for 45% of the participants. Despite the positive effects and high levels of usability and acceptance of the VR-exercise system that we found in our previous studies [

15,

22,

23] there were many participants who didn’t complete the experimental procedure. However, this can be supported by the literature, while exercise adherence is challenging for this population [

60]. Second, while the study demonstrated improvements in mood and enjoyment, the short duration of the intervention prevents conclusions about long-term effects or adherence to VR-based exercise. Additionally, the lack of a control group that did not engage in exercise restricts the ability to isolate the specific effects of VR-based cycling compared to a non-exercise condition. Future studies should include larger, more diverse samples and longer intervention periods to validate these findings and explore the broader implications of VR exercise in T1DM management. They can also explore bioinformatic indicators to better understand the mechanisms underlying the benefits of VR exercise and develop environments that are both enjoyable and engaging for participants.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, a single session of VR exercise improved mood and increased interest/enjoyment compared to traditional exercise. However, no differences were observed in heart rate, blood pressure, or blood glucose levels. Participants showed a strong preference for using the VR system for exercise, with high scores in acceptance, usability, and future use intention, and no negative emotions reported. Future research with a larger sample of individuals with T1DM could investigate the effects of longer-term VR exercise programs compared to traditional cycling on blood glucose levels and other biological indicators. Continuous glucose monitoring throughout the exercise sessions could also be included.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.T, V.T.S, E.T., M.H., A.B, G.D.; methodology, V.T.S., E.T, & Y.T.; formal analysis, E.T.; investigation, E.T., V.T.S. G.D; data curation, E.T.; writing—original draft preparation, E.T, V.T.S.; writing—review and editing, E.T., V.T.S., Y.T., M.H; visualization, Y.T, V.T.S, E.T.; supervision, Y.T. .All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of University of Thessaly (protocol code 1829, 13 October 2021).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to the patients who participated in this study and to the staff of the University Hospital of Larissa for their invaluable support in conducting the research and assisting with patient recruitment.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest

References

- World Health Organization (WHO). Physical Activity Fact Sheet. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/physical-activity [accessed on 22 September 2024].

- Egede, J.K.; Campbell, J.A.; Walker, R.J.; Egede, L.E. Perceived Stress as a Pathway for the Relationship Between Neighborhood Factors and Glycemic Control in Adults With Diabetes. Am. J. Health Promot. 2022, 36, 269–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diabetes UK. Stress and Diabetes. Available online: https://www.diabetes.org.uk/living-with-diabetes/emotional-wellbeing/stress [accessed on 14 November 2024].

- Hermanns, N.; Scheff, C.; Kulzer, B.; et al. Association of glucose levels and glucose variability with mood in type 1 diabetic patients. Diabetologia 2007, 50, 930–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Tilburg, M.A.L.; McCaskill, C.C.; Lane, J.D.; Edwards, C.L.; Bethel, A.; Feinglos, M.N.; Surwit, R.S. Depressed Mood Is a Factor in Glycemic Control in Type 1 Diabetes. Psychosomatic Medicine 2001, 63, 551–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabag, A.; Chang, C.R.; Francois, M.E.; Keating, S.E.; Coombes, J.S.; Johnson, N.A.; Pastor-Valero, M.; Rey Lopez, J.P. The Effect of Exercise on Quality of Life in Type 2 Diabetes: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2023, 55, 1353–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilkie, L.; Mitchell, F.; Robertson, K.; Kirk, A. Motivations for physical activity in youth with type 1 diabetes participating in the ActivPals project: a qualitative study. Practical Diabetes 2017, 34, 151–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alarcón-Gómez, J.; Chulvi-Medrano, I.; Martin-Rivera, F.; Calatayud, J. Effect of High-Intensity Interval Training on Quality of Life, Sleep Quality, Exercise Motivation and Enjoyment in Sedentary People with Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 12612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckworth, J.; Lee, R.E.; Regan, G.; Schneider, L.K.; DiClemente, C.C. Decomposing intrinsic and extrinsic motivation for exercise: Application to stages of motivational readiness. Psychology of Sport and Exercise 2007, 8, 441–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klompstra, L.; Deka, P.; Almenar, L.; et al. Physical activity enjoyment, exercise motivation, and physical activity in patients with heart failure: A mediation analysis. Clinical Rehabilitation 2022, 36, 1324–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaughan, N. Virtual Reality Meets Diabetes. Journal of Diabetes Science and Technology 2024, 0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reagan, L.; Pereira, K.; Jefferson, V.; Evans Kreider, K.; Totten, S.; D'Eramo Melkus, G.; Johnson, C.; Vorderstrasse, A. Diabetes Self-management Training in a Virtual Environment. Diabetes Educ. 2017, 43, 413–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruber, N.; Shemesh-Iron, M.; Kraft, E.; Mitelberg, K.; Mauda, E.; Ben-Ami, M.; Mazor-Aronovitch, K.; Levy-Shraga, Y.; Levran, N.; Levek, N.; Zimlichman, E.; Pinhas-Hamiel, O. Virtual reality's impact on children with type 1 diabetes: a proof-of-concept randomized cross-over trial on anxiety, pain, adherence, and glycemic control. Acta Diabetol. 2024, 61, 215–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yim, Y.R.; Hur, M.H. Effects of virtual reality program on glycated hemoglobin, static and dynamic balancing ability, and falls efficacy for diabetic patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Korean Academy of Fundamental Nursing 2023, 30, 155–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stavrou, V.T.; Vavougios, G.D.; Kalogiannis, P.; Tachoulas, K.; Touloudi, E.; Astara, K.; Mysiris, D.S.; Tsirimona, G.; Papayianni, E.; Boutlas, S.; Hassandra, M.; Daniil, Z.; Theodorakis, Y.; Gourgoulianis, K.I. Breathlessness and exercise with virtual reality system in long-post-coronavirus disease 2019 patients. Front Public Health 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.; Shin, S. Effectiveness of virtual reality using video gaming technology in elderly adults with diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2013, 15, 489–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.J.; Hong, J.H.; Hur, M.H.; Seo, E.Y. Effects of Virtual Reality Exercise Program on Blood Glucose, Body Composition, and Exercise Immersion in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2023, 20, 4178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senior, H.; Henwood, T.; de Souza, D.; Mitchell, G. Investigating innovative means of prompting activity uptake in older adults with type 2 diabetes: A feasibility study of exergaming. J. Sports Med. Phys. Fitness 2016, 56, 1221–1225. [Google Scholar]

- Mallik, R.; Patel, M.; Atkinson, B.; Kar, P. Exploring the Role of Virtual Reality to Support Clinical Diabetes Training—A Pilot Study. J. Diabetes Sci. Technol. 2022, 16, 844–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Theng, Y.L.; Lee, J.W.Y.; Patinadan, P.V.; Foo, S.S.B. The use of videogames, gamification, and virtual environments in the self-management of diabetes: A systematic review of evidence. Games Health J. 2015, 4, 352–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Medical Association. WMA Declaration of Helsinki – Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. Available online: [https://www.wma.net/policies-post/wma-declaration-of-helsinki-ethical-principles-for-medical-research-involving-human-subjects/](https://www.wma.net/policies-post/wma-declaration-of-helsinki-ethical-principles-for-medical-research-involving-human-subjects/) [accessed on 11 January 2025].

- Touloudi, E.; Hassandra, M.; Stavrou, V.T.; Panagiotounis, F.; Galanis, E.; Goudas, M.; Theodorakis, Y. Exploring the Acute Effects of Immersive Virtual Reality Biking on Self-Efficacy and Attention of Individuals in the Treatment of Substance Use Disorders: A Feasibility Study. Brain Sci. 2024, 14, 724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touloudi, E.; Hassandra, M.; Galanis, E.; Goudas, M.; Theodorakis, Y. Applicability of an Immersive Virtual Reality Exercise Training System for Office Workers during Working Hours. Sports (Basel) 2022, 10, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassandra, M.; Galanis, E.; Hatzigeorgiadis, A.; Goudas, M.; Mouzakidis, C.; Karathanasi, E.M.; Petridou, N.; Tsolaki, M.; Zikas, P.; Evangelou, G.; Papagiannakis, G.; Bellis, G.; Kokkotis, C.; Panagiotopoulos, S.R.; Giakas, G.; Theodorakis, Y. Exercise Program Effects on Alzheimer's Disease Risk Factors: A Study on Older Adults. JMIR Serious Games 2021, 9, e24170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zigmond, A.S.; Snaith, R.P. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 1983, 67, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michopoulos, I.; Douzenis, A.; Kalkavoura, C.; Christodoulou, C.; Michalopoulou, P.; Kalemi, G.; Fineti, K.; Patapis, P.; Protopapas, K.; Lykouras, L. Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS): Validation in a Greek General Hospital Sample. Ann. Gen. Psychiatry 2008, 7, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buysse, D.J.; Reynolds, C.F.; Monk, T.H.; Berman, S.R.; Kupfer, D.J. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI): A New Instrument for Psychiatric Research and Practice. Psychiatry Res. 1989, 28, 193–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petropoulakos, K.; Papakonstantinou, V.; Pentsi, S.; Souzou, E.; Dimitriadis, Z.; Billis, E.; Koumantakis, G.; Poulis, I.; Spanos, S. Validity and Reliability of the Greek Version of Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index in Chronic Non-Specific Low Back Pain Patients. Healthcare (Basel) 2024, 12, 557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ware, J.; Kosinski, M.; Keller, S.D. A 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey: Construction of Scales and Preliminary Tests of Reliability and Validity. Med. Care 1996, 34, 220–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McNair, D.; Lorr, M.; Doppleman, L. POMS Manual for the Profile of Mood States, 27th ed.; Educational and Industrial Testing Service: San Diego, CA, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Maggouritsa, M.; Kokaridas, D.; Theodorakis, Y.; Patsiaouras, A. The Effect of a Physical Activity Programme on Improving Mood Profile of Patients with Schizophrenia. Int. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2014, 12, 253–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Guide for Constructing Self-Efficacy Scales. In Self-Efficacy Beliefs of Adolescents; Pajares, T., Urdan, T., Eds.; Information Age Publishing: Greenwich, CT, 2006; pp. 307–337. [Google Scholar]

- Megakli, T.; Vlachopoulos, S.; Thøgersen-Ntoumani, C.; Theodorakis, Y. Impact of Aerobic and Resistance Exercise Combination on Physical Self-Perceptions and Self-Esteem in Women with Obesity with One-Year Follow-Up. Int. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2017, 15, 236–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goudas, M.; Biddle, S.; Fox, K. Perceived Locus of Causality, Goal Orientations, and Perceived Competence in School Physical Education Classes. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 1994, 64, 453–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goudas, M.; Dermitzaki, I.; Bagiatis, K. Predictors of Student’s Intrinsic Motivation in School Physical Education. Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. 2000, 15, 271–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, R.; Prasad, J. A Conceptual and Operational Definition of Personal Innovativeness in the Domain of Information Technology. Information Systems Research 1998, 9, 204–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooke, J. SUS - A Quick and Dirty Usability Scale. In Usability Evaluation in Industry; Jordan, P.W., Thomas, B., McClelland, I.L., Weerdmeester, B., Eds.; Taylor & Francis Ltd.: Bristol, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Mrakic-Sposta, S.; Di Santo, S.G.; Franchini, F.; Arlati, S.; Zangiacomi, A.; Greci, L.; Moretti, S.; Jesuthasan, N.; Marzorati, M.; Rizzo, G.; Sacco, M.; Vezzoli, A. Effects of Combined Physical and Cognitive Virtual Reality-Based Training on Cognitive Impairment and Oxidative Stress in MCI Patients: A Pilot Study. Front Aging Neurosci. 2018, 10, 282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rasimah, C.M.Y.; Ahmad, A.; Zaman, H.B. Evaluation of User Acceptance of Mixed Reality Technology. AJET 2011, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. Constructing a Theory of Planned Behavior Questionnaire. 2006. Available online: https://people.umass.edu/aizen/ (accessed on 25 January 2023).

- Stavrou, V.T.; Vavougios, G.D.; Astara, K.; Siachpazidou, D.I.; Papayianni, E.; Gourgoulianis, K.I. The 6-Minute Walk Test and Anthropometric Characteristics as Assessment Tools in Patients with Obstructive Sleep Apnea Syndrome. A Preliminary Report during the Pandemic. J. Pers. Med. 2021, 11, 563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borg, E.; Borg, G.; Larsson, K.; Letzter, M.; Sundblad, B.M. An Index for Breathlessness and Leg Fatigue. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2010, 20, 644–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeMers, D.; Wachs, D. Physiology, Mean Arterial Pressure. [Updated 2023 Apr 10]. In StatPearls [Internet]; StatPearls Publishing:: Treasure Island (FL), 2024; Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK538226/# (accessed on 25 January 2025).

- Elsholz, S.; Pham, K.; Zarnekow, R. A taxonomy of virtual reality sports applications. Virtual Reality 2025, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colberg, S.R.; Sigal, R.J.; Yardley, J.E.; Riddell, M.C.; Dunstan, D.W.; Dempsey, P.C.; Horton, E.S.; Castorino, K.; Tate, D.F. Physical Activity/Exercise and Diabetes: A Position Statement of the American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care 2016, 39, 2065–2079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Surwit, R.S.; Schneider, M.S.; Feinglos, M.N. Stress and Diabetes Mellitus. Diabetes Care 1992, 15, 1413–1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brito Gomes, J.L.; Vancea, D.M.M.; Farinha, J.B.; Barros, C.B.A.; Costa, M.C. 24-Hour Blood Glucose Responses After Exergame and Running in Type-1 Diabetes: An Intensity- and Duration-Matched Randomized Trial. Sci. Sports 2023, 38, 726–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, J.L. de B.; Vancea, D.M.M.; Araújo, R.C. de; Soltani, P.; Guimarães, F.J. de S.P.; Costa, M.da C. Cardiovascular and Enjoyment Comparisons after Active Videogame and Running in Type 1 Diabetes Patients: A Randomized Crossover Trial. Games Health J. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Yardley, J.E.; Brockman, N.K.; Bracken, R.M. Could Age, Sex, and Physical Fitness Affect Blood Glucose Responses to Exercise in Type 1 Diabetes? Front. Endocrinol. 2018, 9, 674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihailova, A.; Kaminska, I. Lung Volumes Related to Physical Activity, Physical Fitness, Aerobic Capacity, and Body Mass Index in Students. SHS Web of Conferences 2016, 30, 00017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burhanuddin, S.; Suwardi, S.; Jumareng, H.; Anugrah, B.A. The Effect of the Vital Capacity of the Lungs, Nutrition Status, Physical Activity, and Sport Motivation towards Physical Fitness for Male Students at Secondary Schools in Indonesia. Multicultural Educ. 2021, 7, 347–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plante, T.G.; Aldridge, A.; Bogden, R.; Hanelin, C. Might Virtual Reality Promote the Mood Benefits of Exercise? Comput. Hum. Behav. 2003, 19, 495–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochi, G.; Ohno, K.; Kuwamizu, R.; Yamashiro, K.; Fujimoto, T.; Ikarashi, K.; Kodama, N.; Onishi, H.; Sato, D. Exercising with Virtual Reality Is Potentially Better for the Working Memory and Positive Mood Than Cycling Alone. Ment. Health Phys. Act. 2024, 27, 100641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poli, L.; Greco, G.; Gabriele, M.; Pepe, I.; Centrone, C.; Cataldi, S.; Fischetti, F. Effect of Outdoor Cycling, Virtual and Enhanced Reality Indoor Cycling on Heart Rate, Motivation, Enjoyment and Intention to Perform Green Exercise in Healthy Adults. J. Funct. Morphol. Kinesiol. 2024, 9, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Porges, S.W. Cardiac Vagal Tone: A Physiological Index of Stress. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 1995, 19, 225–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Julián, M.T.; Pérez-Montes de Oca, A.; Julve, J.; et al. The Double Burden: Type 1 Diabetes and Heart Failure—A Comprehensive Review. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2024, 23, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, Y.-M. Exploring Usability, Emotional Responses, Flow Experience, and Technology Acceptance in VR: A Comparative Analysis of Freeform Creativity and Goal-Directed Training. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 6737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, D.R.; Rougeau, K.M. Punching Up the Fun: A Comparison of Enjoyment and In-Task Valence in Virtual Reality Boxing and Treadmill Running. Psychol. Int. 2024, 6, 842–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tussyadiah, I.P.; Wang, D.; Jung, T.H.; tom Dieck, M.C. Virtual Reality, Presence, and Attitude Change: Empirical Evidence from Tourism. Tour. Manag. 2018, 66, 140–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borus, J.S.; Laffel, L. Adherence Challenges in the Management of Type 1 Diabetes in Adolescents: Prevention and Intervention. Curr. Opin. Pediatr. 2010, 22, 405–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).