Submitted:

28 January 2025

Posted:

29 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

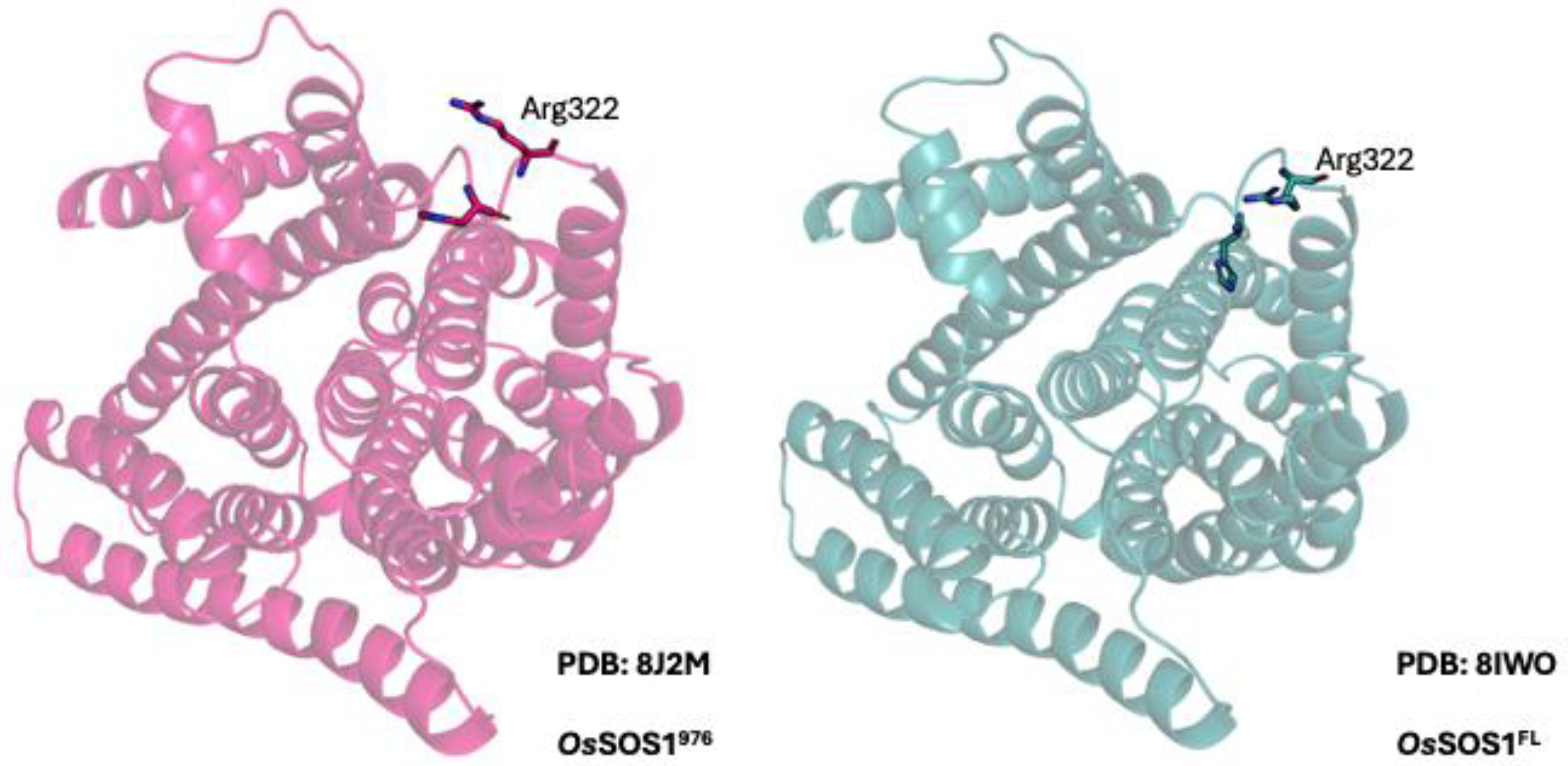

2.1. SOS1 Alignment and Modeling- Salt Tolerant Strains of Plants Have Evolved Adaptations to Cope with the Presence of Extraneous Sodium.

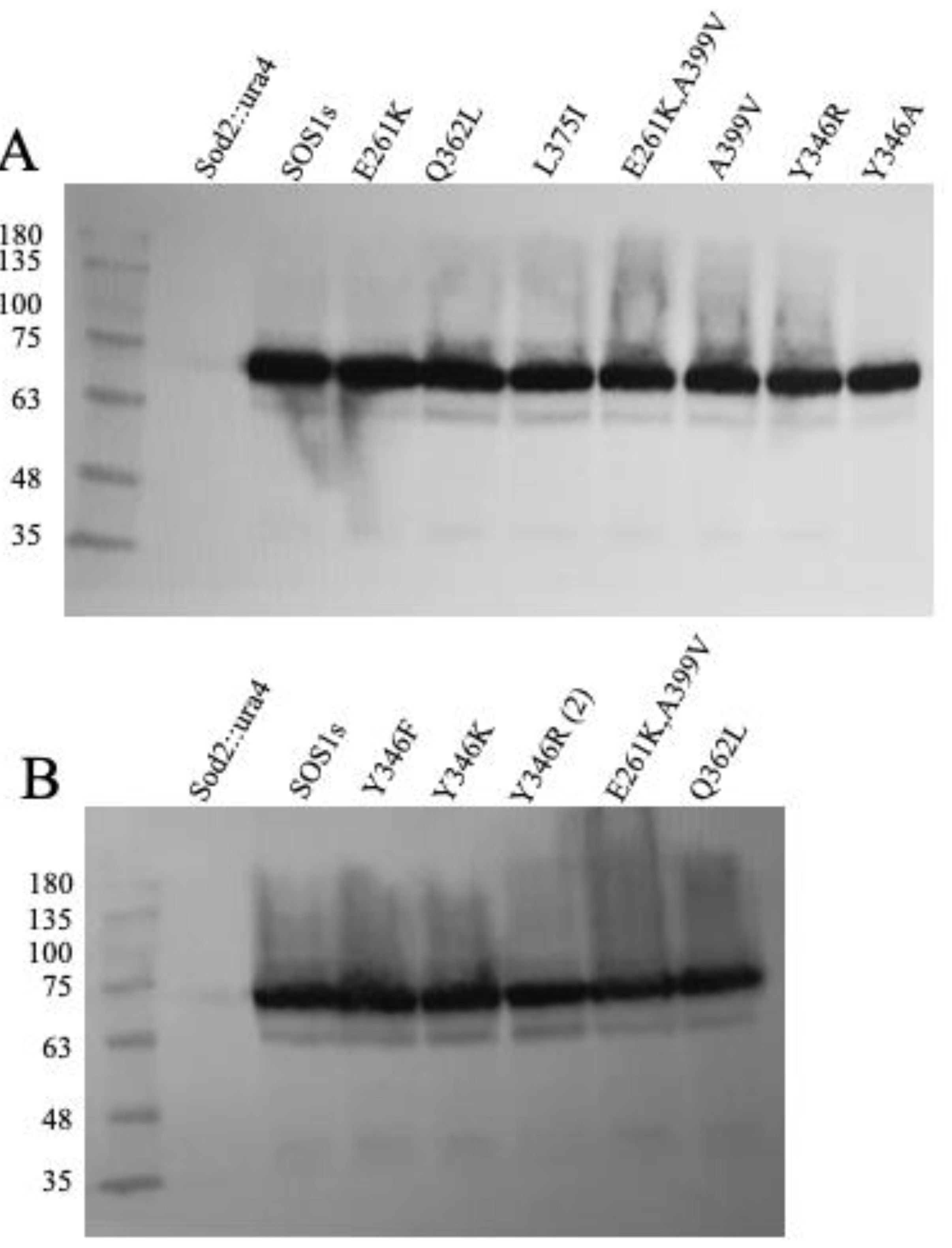

2.2. Expression of Wild Type and Mutant SOS1 in S. pombe-

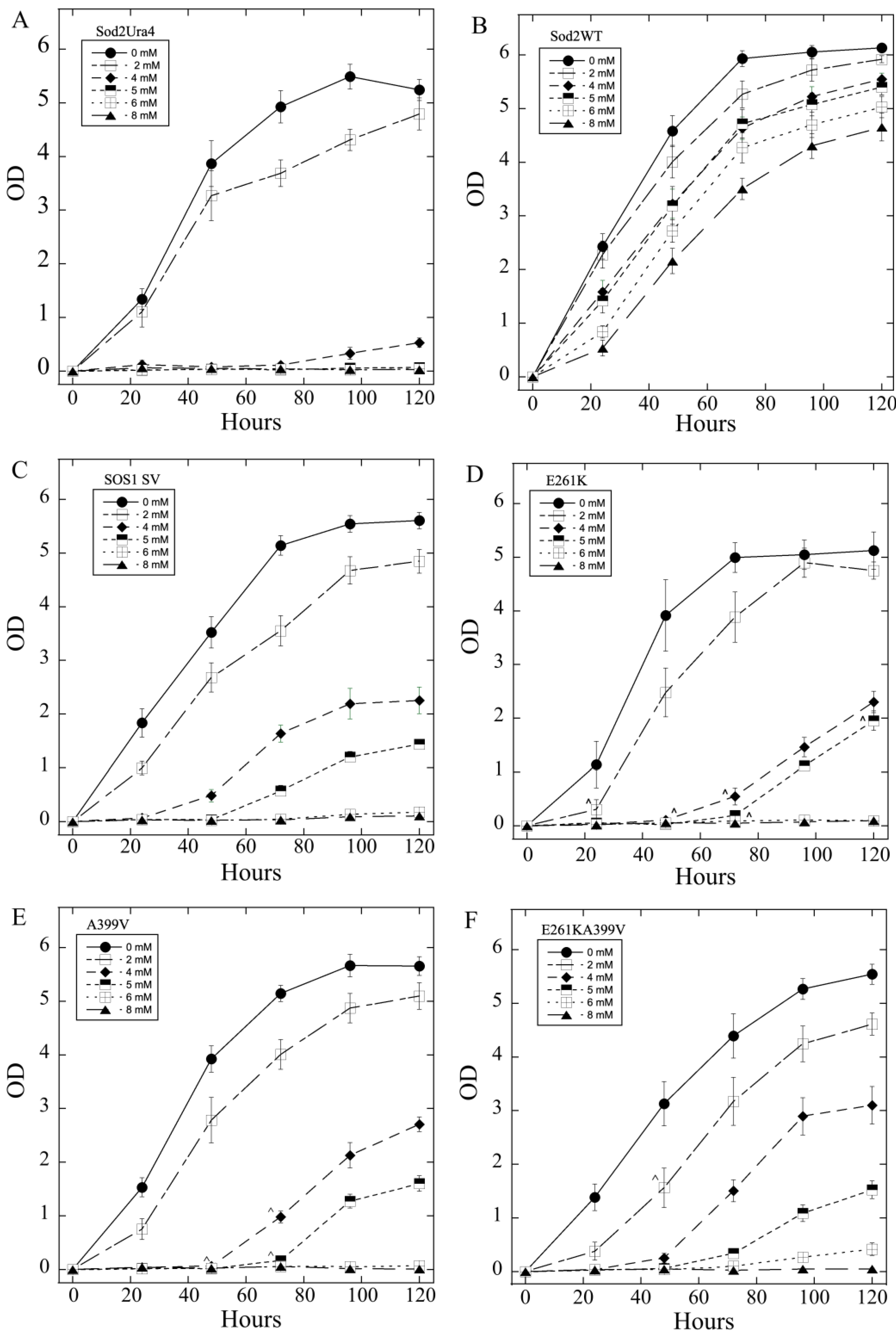

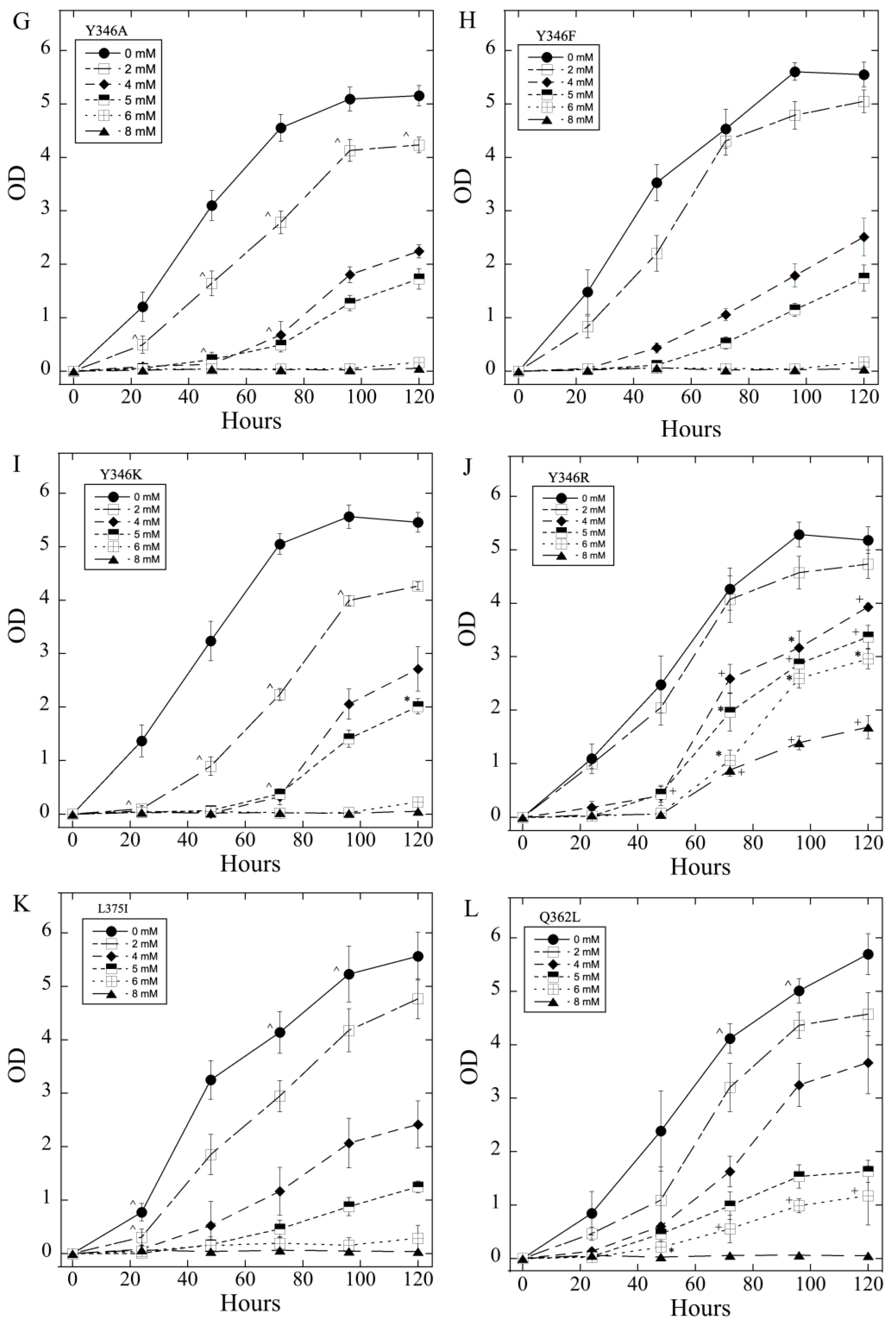

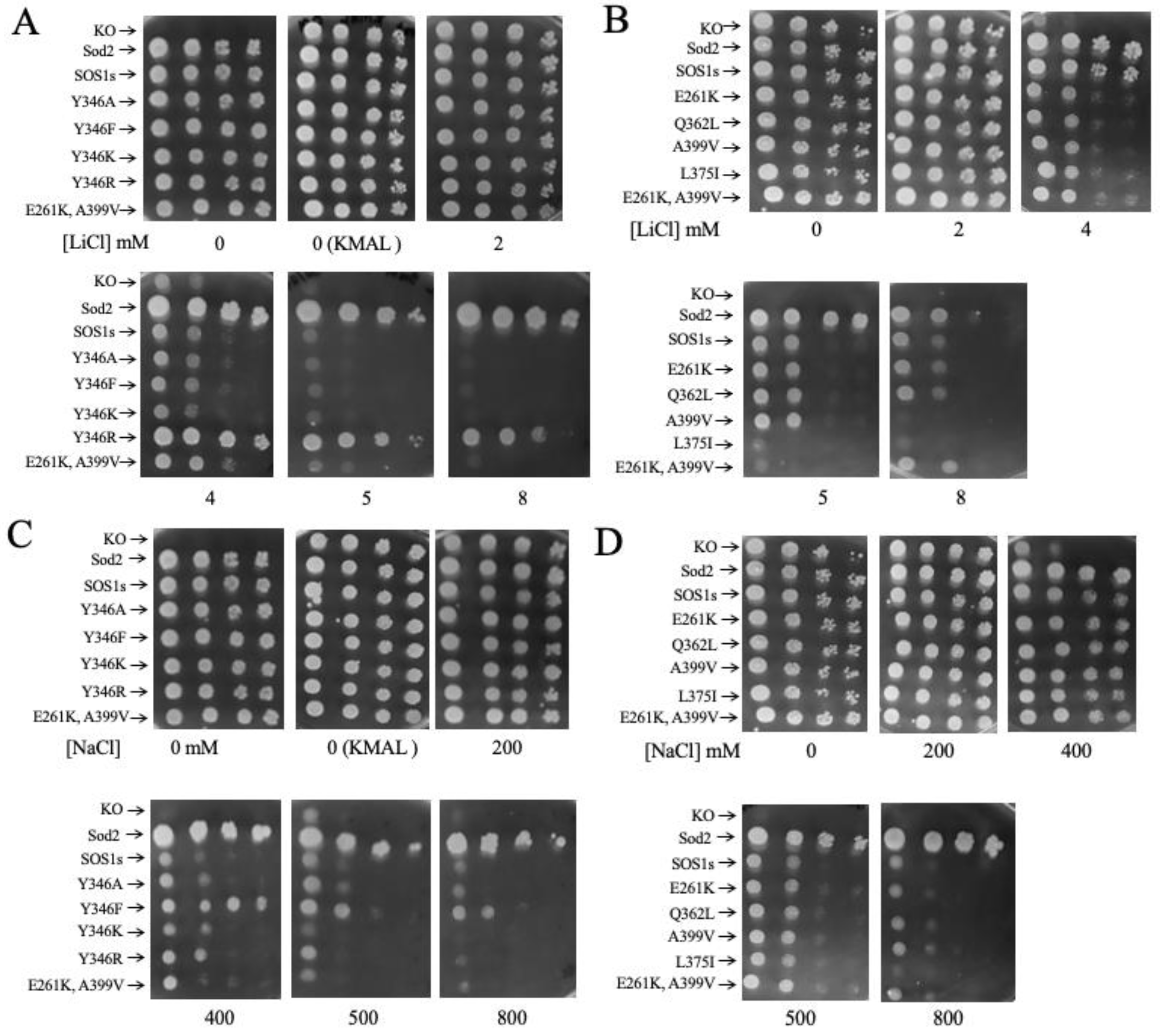

2.3. Salt Tolerance of Wild Type and Mutant SOS1 in S. pombe-

| ||||||||

| Mutant | Growth in 2-5 mM LiCl | Growth in 6, 8 LiCl mM | Growth in 200- 500 mM NaCl | Growth in 600, 800 mM NaCl ( | ||||

| E261K | - | + | - | = | ||||

| A399V | - | = | + | = | ||||

| E261KA399V | - | = | + | = | ||||

| Y346A | -,- | = | + | = | ||||

| Y346F | = | = | +, ^ | = | ||||

| Y346K | -,- | - | = | + | ||||

| Y346R | +++ | +++ | = | = | ||||

| L375I | =, * | = | -,- | - | ||||

| Q362L | =, * | +, * | = | = | ||||

| ||||||||

| Mutant | Growth in 2, 4 mM LiCl | Growth in 5, 8 LiCl mM | Growth in 200, 400 mM NaCl | Growth in 500, 800 mM NaCl | ||||

| E261K | - | = | = | = | ||||

| A399V | - | - | = | = | ||||

| E261KA399V | - | - | = | = | ||||

| Y346A | = | = | = | = | ||||

| Y346F | = | = | + | + | ||||

| Y346K | = | = | = | = | ||||

| Y346R | ++ | +++ | = | = | ||||

| L375I | = | -- | = | = | ||||

| Q362L | = | = | = | = | ||||

3. Discussion

| Mutation | Oligonucleotide | Restriction Site |

| E261K | CAATGACACTGTtATAaAGATTACTCTTACAATTGC | Psi1 |

| Y346A | AGTGATAAGATTGCCgcaCAAGGGAAcTCATGGCGATTTC | -EcoR1 |

| Y346F | AGTGATAAGATTGCCTtcCAAGGGAAcTCATGG | -EcoR1 |

| Y346K | AGTGATAAGATTGCCaagCAAGGGAAcTCATGGCGATTTC | -EcoR1 |

| Y346R | GATAAGATTGCCcgCCAAGGGAAcTCATGGCGATTTC | -EcoR1 |

| L375I | GGAGTTCTATATCCAaTTcTgTGcagaTTTGGCTATGGTTTG | BsgI |

| Q362L | CTATACGTTTACATCCtcCTcTCGCGTGTTGTTG | BseR1 |

| A399V | GGTTTGAGGGGCgTcGTGGCTCTTGCAC | -Bts1 |

| E261KA399V | caatgacactgttataaAgattactcttacaattgcGGTTTGAGGGGCgTcGTGGCTCTTGCAC | Psi & Bts1 |

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Materials

4.2. Plasmids and Site-Directed Mutagenesis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SOS | Salt Overlay Sensitive |

| SOS1s | Salt Overlay Sensitive 1 protein shortened at the C-terminus |

| At | Arabidopsis thaliana |

| TM | Transmembrane |

| GFP | Green fluorescent protein |

References

- Frommer, W. B.; Ludewig, U.; Rentsch, D. Taking transgenic plants with a pinch of salt. Science 1999, 285(5431), 1222–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apse, M. P.; Blumwald, E. Engineering salt tolerance in plants. Current opinion in biotechnology 2002, 13(2), 146–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deinlein, U.; Stephan, A. B.; Horie, T.; Luo, W.; Xu, G.; Schroeder, J. I. Plant salt-tolerance mechanisms. Trends in plant science 2014, 19(6), 371–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.; Vinocur, B.; Altman, A. Plant responses to drought, salinity and extreme temperatures: towards genetic engineering for stress tolerance. Planta 2003, 218(1), 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, H.; Pardo, J. M.; Batelli, G.; Van Oosten, M. J.; Bressan, R. A.; Li, X. The Salt Overly Sensitive (SOS) pathway: established and emerging roles. Mol Plant 2013, 6(2), 275–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.; Quintero, F. J.; Pardo, J. M.; Zhu, J. K. The putative plasma membrane Na(+)/H(+) antiporter SOS1 controls long- distance Na(+) transport in plants. Plant Cell 2002, 14(2), 465–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salazar, O. R.; Chen, K.; Melino, V. J.; Reddy, M. P.; Hribova, E.; Cizkova, J.; Berankova, D.; Arciniegas Vega, J. P.; Caceres Leal, L. M.; Aranda, M.; Jaremko, L.; Jaremko, M.; Fedoroff, N. V.; Tester, M.; Schmockel, S. M. SOS1 tonoplast neo-localization and the RGG protein SALTY are important in the extreme salinity tolerance of Salicornia bigelovii. Nat Commun 2024, 15(1), 4279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sze, H.; Chanroj, S. Plant Endomembrane Dynamics: Studies of K(+)/H(+) Antiporters Provide Insights on the Effects of pH and Ion Homeostasis. Plant physiology 2018, 177(3), 875–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez-Rosales, M. P.; Galvez, F. J.; Huertas, R.; Aranda, M. N.; Baghour, M.; Cagnac, O.; Venema, K. Plant NHX cation/proton antiporters. Plant Signal Behav 2009, 4(4), 265–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanin, M.; Ebel, C.; Ngom, M.; Laplaze, L.; Masmoudi, K. New Insights on Plant Salt Tolerance Mechanisms and Their Potential Use for Breeding. Front Plant Sci 2016, 7, 1787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, Y.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, J.; Duan, L.; Li, Z. SOS1 gene overexpression increased salt tolerance in transgenic tobacco by maintaining a higher K(+)/Na(+) ratio. J Plant Physiol 2012, 169(3), 255–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.; Lee, B. H.; Wu, S. J.; Zhu, J. K. Overexpression of a plasma membrane Na+/H+ antiporter gene improves salt tolerance in Arabidopsis thaliana. Nature biotechnology 2003, 21(1), 81–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Q.; Chen, Z. Z.; Zhou, X. F.; Yin, H. B.; Li, X.; Xin, X. F.; Hong, X. H.; Zhu, J. K.; Gong, Z. , Overexpression of SOS (Salt Overly Sensitive) genes increases salt tolerance in transgenic Arabidopsis. Mol Plant 2009, 2(1), 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duscha, K.; Martins Rodrigues, C.; Muller, M.; Wartenberg, R.; Fliegel, L.; Deitmer, J. W.; Jung, M.; Zimmermann, R.; Neuhaus, H. E., 14-3-3 Proteins and Other Candidates form Protein-Protein Interactions with the Cytosolic C-terminal End of SOS1 Affecting Its Transport Activity. International journal of molecular sciences 2020, 21, (9). [CrossRef]

- El Mahi, H.; Perez-Hormaeche, J.; De Luca, A.; Villalta, I.; Espartero, J.; Gamez-Arjona, F.; Fernandez, J. L.; Bundo, M.; Mendoza, I.; Mieulet, D.; Lalanne, E.; Lee, S. Y.; Yun, D. J.; Guiderdoni, E.; Aguilar, M.; Leidi, E. O.; Pardo, J. M.; Quintero, F. J. A Critical Role of Sodium Flux via the Plasma Membrane Na(+)/H(+) Exchanger SOS1 in the Salt Tolerance of Rice. Plant physiology 2019, 180(2), 1046–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oh, D. H.; Leidi, E.; Zhang, Q.; Hwang, S. M.; Li, Y.; Quintero, F. J.; Jiang, X.; D'Urzo, M. P.; Lee, S. Y.; Zhao, Y.; Bahk, J. D.; Bressan, R. A.; Yun, D. J.; Pardo, J. M.; Bohnert, H. J. Loss of halophytism by interference with SOS1 expression. Plant physiology 2009, 151(1), 210–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q.; Guan, C.; Wang, P.; Ma, Q.; Bao, A. K.; Zhang, J. L.; Wang, S. M., The Effect of AtHKT1;1 or AtSOS1 Mutation on the Expressions of Na(+) or K(+) Transporter Genes and Ion Homeostasis in Arabidopsis thaliana under Salt Stress. International journal of molecular sciences 2019, 20, (5). [CrossRef]

- Wu, S. J.; Ding, L.; Zhu, J. K. SOS1, a Genetic Locus Essential for Salt Tolerance and Potassium Acquisition. Plant Cell 1996, 8(4), 617–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, Z.-P.; McCullough, N.; Martel, R.; Hemmingsen, S.; Young, P. G. Gene amplification at a locus encoding a putative Na+/H+ antiporter confers sodium and lithium tolerance in fission yeast. EMBO J. 1992, 11, 1631–1640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, A.; Dutta, D.; Fliegel, L., Expression and characterization of the SOS1 Arabidopsis salt tolerance protein. Mol Cell Biochem 2016, 415, (1-2), 133-43. [CrossRef]

- Quintero, F. J.; Martinez-Atienza, J.; Villalta, I.; Jiang, X.; Kim, W. Y.; Ali, Z.; Fujii, H.; Mendoza, I.; Yun, D. J.; Zhu, J. K.; Pardo, J. M. Activation of the plasma membrane Na/H antiporter Salt-Overly-Sensitive 1 (SOS1) by phosphorylation of an auto-inhibitory C-terminal domain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2011, 108(6), 2611–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, K.; Wu, Y. , Footprints of divergent evolution in two Na+/H+ type antiporter gene families (NHX and SOS1) in the genus Populus. Tree Physiol 2018, 38(6), 813–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X. Y.; Tang, L. H.; Nie, J. W.; Zhang, C. R.; Han, X.; Li, Q. Y.; Qin, L.; Wang, M. H.; Huang, X.; Yu, F.; Su, M.; Wang, Y.; Xu, R. M.; Guo, Y.; Xie, Q.; Chen, Y. H. Structure and activation mechanism of the rice Salt Overly Sensitive 1 (SOS1) Na(+)/H(+) antiporter. Nat Plants 2023, 9(1), 1924–1936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Pan, C.; Chen, Q.; Xie, Q.; Gao, Y.; He, L.; Li, Y.; Dong, Y.; Jiang, X.; Zhao, Y. Architecture and autoinhibitory mechanism of the plasma membrane Na(+)/H(+) antiporter SOS1 in Arabidopsis. Nat Commun 2023, 14(1), 4487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nunez-Ramirez, R.; Sanchez-Barrena, M. J.; Villalta, I.; Vega, J. F.; Pardo, J. M.; Quintero, F. J.; Martinez-Salazar, J.; Albert, A. Structural insights on the plant salt-overly-sensitive 1 (SOS1) Na(+)/H(+) antiporter. Journal Mol Biol 2012, 424(5), 283–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dutta, D.; Ullah, A.; Bibi, S.; Fliegel, L. Functional Analysis of Conserved Transmembrane Charged Residues and a Yeast Specific Extracellular Loop of the Plasma Membrane Na(+)/H(+) Antiporter of Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Sci Rep 2019, 9(1), 6191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, D.; Shin, K.; Rainey, J. K.; Fliegel, L. Transmembrane Segment XI of the Na(+)/H(+) Antiporter of S. pombe is a Critical Part of the Ion Translocation Pore. Sci Rep 2017, 7(1), 12793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dibrov, P.; Young, P. G.; Fliegel, L. Functional analysis of amino acid residues essential for activity in the Na+/H+ exchanger of fission yeast. Biochemistry 1998, 36, 8282–8288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dutta, D.; Fliegel, L. Structure and function of yeast and fungal Na(+) /H(+) antiporters. IUBMB life 2018, 70(1), 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugiura, Y.; Saito, Y.; Endo, T.; Makita, Y., Effect of the Ionic Radius of Alkali Metal Ions on Octacalcium Phosphate Formation via Different Substitution ModesC. Crystal Growth & Design 2019, 19, (7), 4162-4171.

- Shi, H.; Ishitani, M.; Kim, C.; Zhu, J. K. The Arabidopsis thaliana salt tolerance gene SOS1 encodes a putative Na+/H+ antiporter. PNAS U S A 2000, 97(12), 6896–6901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.; Wang, D.; Dong, W.; Song, Z.; Dou, K. Over-expression of Na(+)/H (+) exchanger 1 and its clinicopathologic significance in hepatocellular carcinoma. Med Oncol 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shang, G. A. O.; Li, Y. U. A. N.; Hong, Z. H. A. I.; LIU, C. L.; HE, S. Z.; LIU, Q. C., Overexpression of SOS genes enhanced salt tolerance in sweetpotato. Journal of Integrative Agriculture, 11(3), 378-386. Journal of Integrative Agriculture 2012, 11, (3), 378-386.

- Dutta, D.; Esmaili, M.; Overduin, M.; Fliegel, L. Expression and detergent free purification and reconstitution of the plant plasma membrane Na(+)/H(+) antiporter SOS1 overexpressed in Pichia pastoris. Biochim Biophys Acta Biomembr 2020, 1862(3), 183111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahnenberger, K. M.; Jia, Z.; Young, P. G. Functional expression of the Schizosaccharomyces pombe Na+/H+ antiporter gene, sod2, in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1996, 93, 5031–5036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padan, E. The enlightening encounter between structure and function in the NhaA Na+-H+ antiporter. Trends Biochem Sci 2008, 33(9), 435–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rimon, A.; Amartely, H.; Padan, E. The crossing of two unwound transmembrane regions that is the hallmark of the NhaA structural fold is critical for antiporter activity. Sci Rep 2024, 14(1), 5915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Padan, E.; Kozachkov, L.; Herz, K.; Rimon, A. NhaA crystal structure: functional-structural insights. J Expl Biol 2009, 212 Pt 11, 1593–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beauchamp, D. L.; Khajehpour, M., The effect of lithium ions on the hydrophobic effect: does lithium affect hydrophobicity differently than other ions? Biophys Chem 2012, 163-164, 35-43.

- Li, H.; Francisco, J. S.; Zeng, X. C. Unraveling the mechanism of selective ion transport in hydrophobic subnanometer channels. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2015, 112(35), 10851–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fliegel, L. Functional analysis of conserved polar residues important for salt tolerance of the Na+/H+ exchanger of Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2004, 43, 16477–16486. [Google Scholar]

- Fliegel, L. The Na+/H+ exchanger isoform 1. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2005, 37(1), 33–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, A.; El-Magd, R. A.; Fliegel, L. Functional role and analysis of cysteine residues of the salt tolerance protein Sod2. Mol Cell Biochem 2014, 386(1-2), 85–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndayizeye, M.; Touret, N.; Fliegel, L. Proline 146 is critical to the structure, function and targeting of sod2, the Na+/H+ exchanger of Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Biochim Biophys Acta 2009, 1788(5), 983–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fliegel, L.; Wiebe, C.; Chua, G.; Young, P. G. Functional expression and cellular localization of the Na+/H+ exchanger Sod2 of the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Canadian journal of physiology and pharmacology 2005, 83(7), 565–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slepkov, E. R.; Chow, S.; Lemieux, M. J.; Fliegel, L. Proline residues in transmembrane segment IV are critical for activity, expression and targeting of the Na+/H+ exchanger isoform 1. Biochem J 2004, 379 Pt 1, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, N. L.; Wang, H.; Harris, C. V.; Singh, D.; Fliegel, L. Characterization of the Na+/H+ exchanger in human choriocarcinoma (BeWo) cells. Pflugers Archiv Eur J Physiol 1997, 433, 792–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katoh, K.; Standley, D. M. MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: improvements in performance and usability. Mol Biol Evol 2013, 30(4), 772–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robert, X.; Gouet, P., Deciphering key features in protein structures with the new ENDscript server. Nucleic acids research 2014, 42, (Web Server issue), W320-4. [CrossRef]

- DeLano, W. L. Pymol: An open-source molecular graphics tool. CCP4 Newsl. Protein Crystallogr 2002, 82(1), 82–92. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).