Submitted:

27 January 2025

Posted:

29 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Methods

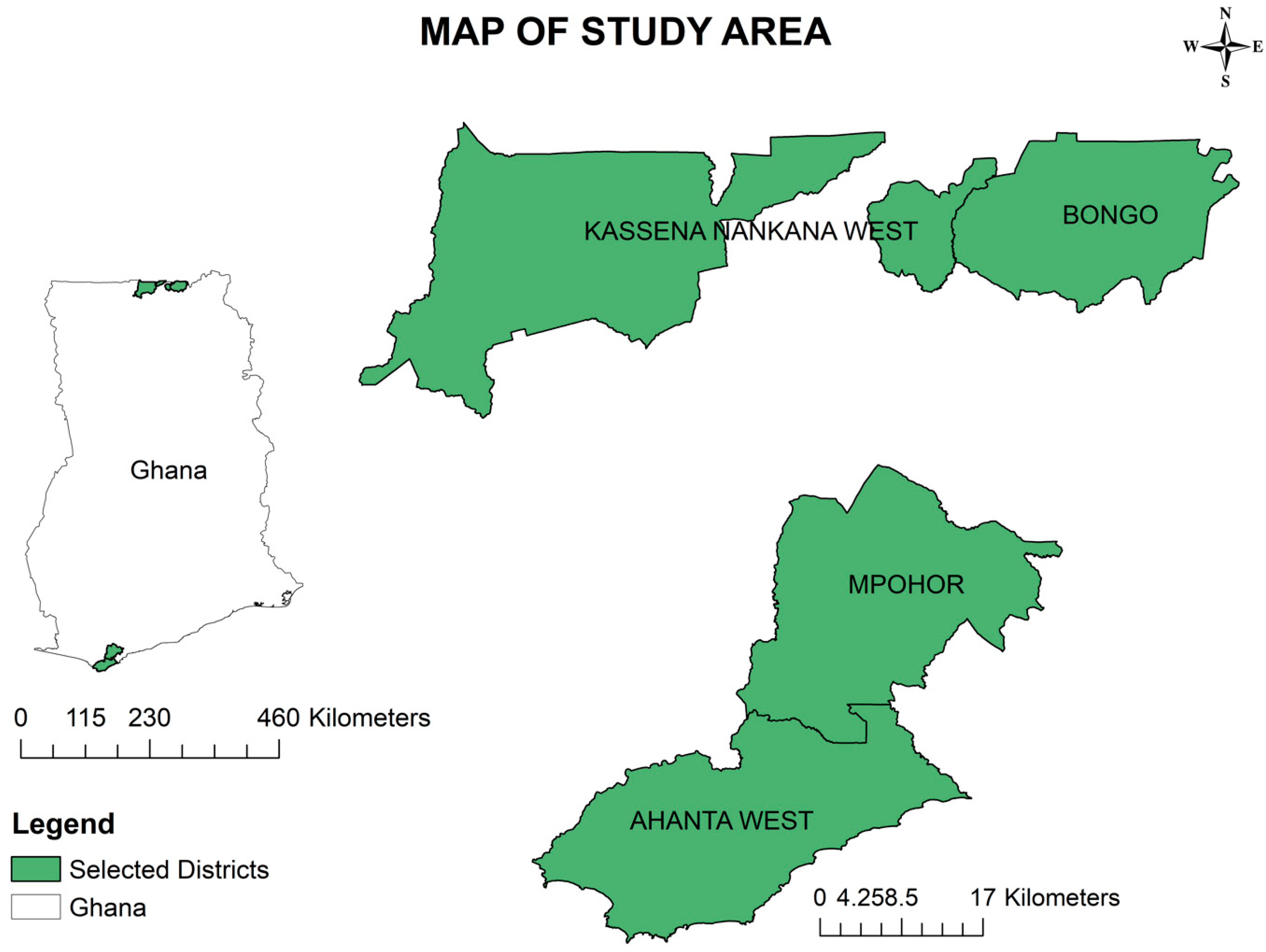

Study sites

Selection criteria

Inclusion criteria

Exclusion criteria

Bongo and Kassena Nankana West

Community engagement

Sample size estimation

Wuchereria bancrofti screening

Blood sampling

Circulating filarial antigen (CFA) screening

Immunochromatographic test (ICT)

Filariasis test strip (FTS)

Surrogate determination of Wuchereria bancrofti clearance after treatment using Immunochromatographic test (ICT) cards or filariasis test strip (FTS)

Immunochromatographic test (ICT) cards or filariasis test strip (FTS) scoring method

Wuchereria bancrofti clearance assessment using Mann-Kendall’s time-series trend analysis, Sens slop, and Pettitt’s point-of-change estimations

Estimation of parasitaemia

Wuchereria bancrofti parasite counts using Sedgwick-Rafter counting chamber

Wuchereria bancrofti parasite counts using thick blood film

Wuchereria bancrofti parasite counts using nucleopore filtration parasitaemia estimation

Antigenaemia prevalence

DNA extraction from blood and packed cells (whole blood having no serum)

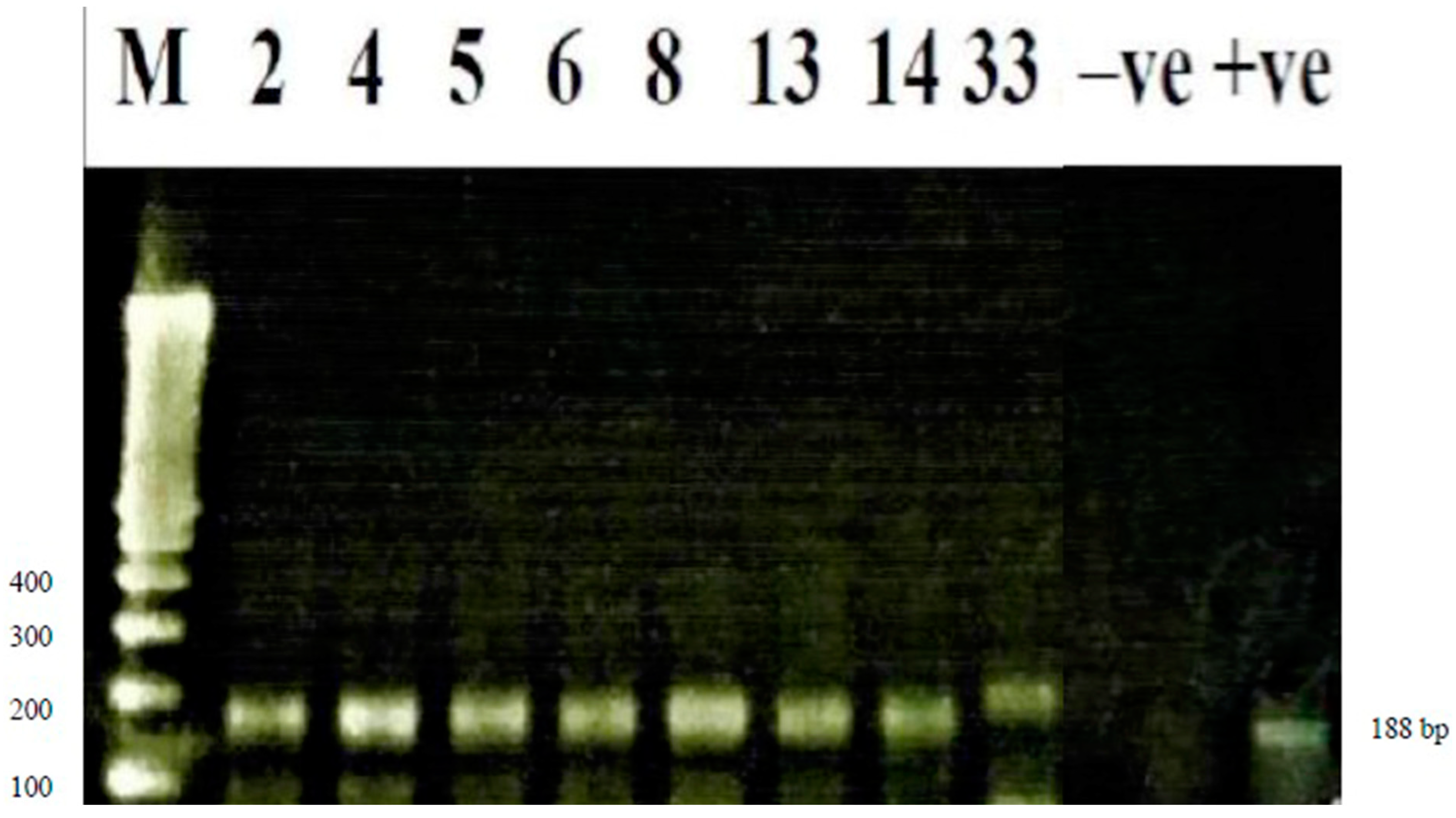

Wuchereria bancrofti detection using conventional polymerase chain reaction (PCR)

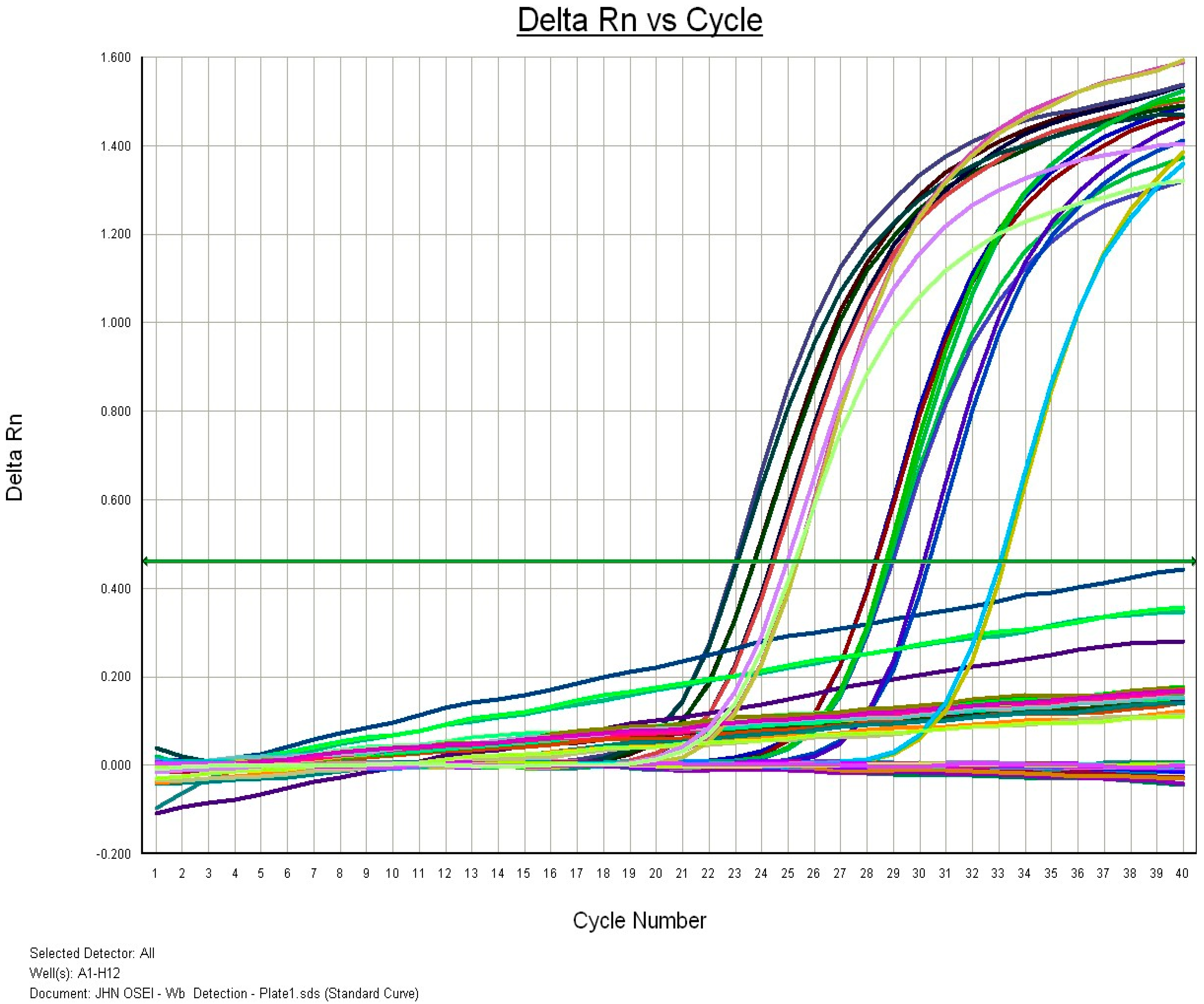

Wuchereria bancrofti detection using real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR)

Results

| Region | District | Community | Wuchereria bancrofti Screening | Prevalence | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number Observed | ICT Positive | Mf | ICT (%) | Mf (%) | |||

| Positive | |||||||

| Western | HAhanta West | Antseambua | 159 | 2 | - | 1.3 | - |

| Asemkow | 370 | 3 | 1 | 0.8 | 0.3 | ||

| CMpohor | Ampeasem | 349 | 0 | - | - | - | |

| Obrayebona | 510 | 0 | - | - | - | ||

| Upper East | HKassena Nankana West | Badunu | 385 | 3 | - | 0.8 | - |

| Navio (Sanwu) Central | 332 | 4 | - | 1.2 | - | ||

| CBongo | Atampiisi Bongo | 413 | 7 | - | 1.7 | - | |

| Balungu Nabiisi | 455 | 14 | 4 | 3.1 | 0.9 | ||

| Region | District | Community | Microfilariae Concentration | Microfilariae Density | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thick Blood Film (mf/ml) | Sedgwick Count (mf/ml) | Thick Blood Film (mf/ml) | Sedgwick Count (mf/ml) | |||

| Western | HAhanta West | Antseambua | - | - | - | - |

| Asemkow | 283.9 | 410.0 | 283.9 | 410.0 | ||

| CMpohor | Ampeasem | - | - | - | - | |

| Obrayebona | - | - | - | - | ||

| Upper East | HKassena Nankana West | Badunu | - | - | - | - |

| Navio (Sanwu) Central | - | - | - | - | ||

| CBongo | Atampiisi Bongo | - | - | - | - | |

| Balungu Nabiisi | 16.7 | 30.0 | 44.5 | 25.0 | ||

| 83.5 | - | |||||

| - | 20.0 | |||||

| 33.4 | - | |||||

Wuchereria bancrofti clearance and repopulation/reinfection estimation

Discussion

Conclusion

Recommendation

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Abbreviation | Meaning |

| ABI | Applied Biosystems Instrument |

| ABZ | Albendazole |

| AW | Ahanta West |

| CDC | Center for Disease Control and Prevention |

| CFA | Circulating Filarial Antigen |

| CHPS | Community-Base Health Planning and Service |

| DDCO | District Disease Control Officer |

| DEPC | Diethylprocarbonate |

| DHMT | District Health Management Team |

| DNA | Deoxyribonucleic acid |

| dNTP | Deoxynucleotide triphosphate |

| EDTA | Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid |

| FTS | Filarial Test Strip |

| GMT | Greenwich Mean Teime |

| GPELF | Global Programme to Eliminate Lymphatic Filariasis |

| ICT | Immunochromatographic Test |

| 1D | Identification |

| IVM | Ivermectin |

| IVM/VC | Integrated Vector Management/Vector Control |

| KNW | Kassena Nankana West |

| LDR | Long DNA Repeat |

| LF | Lymphatic Filariasis |

| MDA | Mass Drug Administration |

| MMDP | Morbidity Management and Disability Prevention |

| MOFA | Ministry of Food and Agriculture |

| NAMRU | Naval Medical Research Unit |

| NMIMR | Noguchi Memorial Institute for Medical Research |

| NTD | Neglected Tropical Diseases |

| PCR | Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| RT-PCR | Reverse Transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| TAS | Transmission Assessment Survey |

| USA | United States of America |

| UV | Ultraviolet |

| WHA | World Health Assembly |

| WHO | World Health Organisation |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

Appendix B.1

| # | Participant | Baseline | X1st.Follow.Up | X2nd.Follow.Up | X3rd.Follow.Up |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | P1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| 2 | P2 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 |

| 3 | P3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| 4 | P4 | 2 | 2 | Travelled | Travelled |

| 5 | P5 | 2 | 2 | 2 | Travelled |

| 6 | P6 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| 7 | P7 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 1 |

Appendix B.2

| Score = -2 | Var(Score) = 34.66667 | denominator = 17.14643 | tau = -0.117 | 2-sided pvalue = 0.86513 |

Appendix B.3

| z = -0.16984 |

n = 7 |

p-value = 0.8651 |

alternative hypothesis: true z is not equal to 0 | 95 percent confidence interval: -0.5000 0.3333 |

sample estimates: Sen’s slope 0 |

Appendix B.4

| U* = 5 |

p-value = 1.364 |

alternative hypothesis: two.sided | sample estimates: | probable change point at time K 6 |

| # | Participant | Baseline | X1st.Follow.Up | X2nd.Follow.Up | X3rd.Follow.Up |

| 6 | P6 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

Appendix C.1

| # | Participant | Baseline | X1st.Follow.Up | X2nd.Follow.Up | X3rd.Follow.Up |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | P8 | 2 | 2 | Travelled | Travelled |

| 2 | P9 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| 3 | P10 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 1 |

| 4 | P11 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 5 | P12 | 2 | Travelled | Travelled | Travelled |

| 6 | P13 | 2 | 2 | Travelled | 2 |

| 7 | P14 | 2 | 2 | 2 | Travelled |

| 8 | P15 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| 9 | P16 | 2 | Travelled | Travelled | 1 |

| 10 | P17 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| 11 | P18 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| 12 | P19 | 2 | 2 | 2 | Travelled |

| 13 | P20 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| 14 | P21 | 2 | 0 | Travelled | 0 |

| Score = 20 |

Var(Score) = 288 |

denominator = 76.31514 |

tau = 0.262 |

2-sided pvalue = 0.26289 |

| z = 1.1196 |

n = 14 |

p-value = 0.2629 |

alternative hypothesis: true z is not equal to 0 | 95 percent confidence interval: 0.00 0.167 |

sample estimates: Sen’s slope 0 |

| U* = 30 |

p-value = 0.3187 |

alternative hypothesis: two.sided | sample estimates: | probable change point at time K 4 |

| # | Participant | Baseline | X1st.Follow.Up | X2nd.Follow.Up | X3rd.Follow.Up |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4 | P11 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Score = -13 |

Var(Score) = 293 |

denominator = 78.08329 |

tau = -0.166 |

2-sided pvalue = 0.48327 |

| z = -0.70105 |

n = 14 |

p-value = 0.4833 |

alternative hypothesis: true z is not equal to 0 | 95 percent confidence interval: -0.2000 0.0000 |

sample estimates: Sen’s slope 0 |

| U* = 19 |

p-value = 0.9573 |

alternative hypothesis: two.sided | sample estimates: | probable change point at time K NA, 7, 8, NA, 9 |

| # | Participant | Baseline | X1st.Follow.Up | X2nd.Follow.Up | X3rd.Follow.Up |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7 | P14 | 2 | 2 | 2 | Travelled |

| # | Participant | Baseline | X1st.Follow.Up | X2nd.Follow.Up | X3rd.Follow.Up |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8 | P15 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| # | Participant | Baseline | X1st.Follow.Up | X2nd.Follow.Up | X3rd.Follow.Up |

| 9 | P16 | 2 | Travelled | Travelled | 1 |

| # | Participant | Baseline | X1st.Follow.Up | X2nd.Follow.Up | X3rd.Follow.Up |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | P22 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| 2 | P23 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 1 |

| 3 | P24 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| Score = -37 |

Var(Score) = 311.6667 |

denominator = 82.61356 |

tau = -0.448 |

2-sided pvalue = 0.041431 |

| z = -2.0392 |

n = 15 |

p-value = 0.04143 |

alternative hypothesis: true z is not equal to 0 | 95 percent confidence interval: -0.1667 0.0000 |

sample estimates: Sen’s slope 0 |

| # | Participant | Baseline | X1st.Follow.Up | X2nd.Follow.Up | X3rd.Follow.Up |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | P25 | 2 | 2 | Travelled | Travelled |

| 2 | P26 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| 3 | P27 | 2 | 2 | Travelled | Travelled |

| 4 | P28 | 2 | 2 | Travelled | Travelled |

| Score = -28 |

Var(Score) = 538 |

denominator = 124.8199 |

tau = -0.224 |

2-sided pvalue = 0.2444 |

| z = -1.1641 |

n = 20 |

p-value = 0.2444 |

alternative hypothesis: true z is not equal to 0 | 95 percent confidence interval: 0.0000 0.0000 |

sample estimates: Sen’s slope 0 |

| # | Participant | Baseline | X1st.Follow.Up | X2nd.Follow.Up | X3rd.Follow.Up |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | P29 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| 2 | P30 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| Score = -9 |

Var(Score) = 93 |

denominator = 34.85685 | tau = -0.258 |

2-sided pvalue = 0.40679 |

| z = -0.82956 |

n = 10 |

p-value = 0.4068 |

alternative hypothesis: true z is not equal to 0 | 95 percent confidence interval: -0.2500 0.0000 |

sample estimates: Sen’s slope 0 |

| # | Participant | Baseline | X1st.Follow.Up | X2nd.Follow.Up | X3rd.Follow.Up |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | P31 | 2 | 2 | Travelled | 2 |

| 2 | P32 | 2 | 2 | Travelled | 2 |

| 3 | P33 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Score = -4 |

Var(Score) = 194.6667 |

denominator = 63.16645 |

tau = -0.0633 |

2-sided pvalue = 0.82975 |

| z = -0.21502 |

n = 15 |

p-value = 0.8298 |

alternative hypothesis: true z is not equal to 0 | 95 percent confidence interval: 0.0000 0.0000 |

sample estimates: Sen’s slope 0 |

| U* = 13 |

p-value = 1.509 |

alternative hypothesis: two.sided | sample estimates: | probable change point at time K 1 |

| # | Participant | Baseline | X1st.Follow.Up | X2nd.Follow.Up | X3rd.Follow.Up |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | P31 | 2 | 2 | Travelled | 2 |

References

- Dunyo SK, Appawu M, Nkrumah FK, Baffoe-Wilmot A, Pedersen EM, Simonsen PE: Lymphatic filariasis on the coast of Ghana. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 1996, 90(6):634-638.

- Dzodzomenyo M, Dunyo SK, Ahorlu CK, Coker WZ, Appawu MA, Pedersen EM, Simonsen PE: Bancroftian filariasis in an irrigation project community in southern Ghana. Tropical Medicine and International Health 1999, 4(1):13-18.

- Gyapong JO, Badu JK, Adjei S, Binka FN: Bancroftian filariasis in the Kasena-Nankana district of the upper east region of Ghana - a preliminary study. Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 1993, 96:317-322.

- Gyapong JO, Dollimore N, Binka FN, Ross DA: Lay reporting of elephantiasis of the leg in northern Ghana. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 1995, 89:616-618.

- Gyapong JO, Magnussen P, Binka FN: Parasitological and clinical aspects of Bancroftian filariasis in the Kasena Nankana District, Upper East Region, Ghana. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 1994, 88(5):555-557.

- Chiphwanya J, Mkwanda S, Kabuluzi S, Mzilahowa T, Ngwira B, Matipula DE, Chaponda L, Ndhlova P, Katchika P, Mahebere Chirambo C et al: Elimination of lymphatic filariasis as a public health problem in Malawi. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2024, 18(2):e0011957.

- Mathiarasan L, Das LK, Krishnakumari A: Assessment of the Impact of Morbidity Management and Disability Prevention for Lymphatic Filariasis on the Disease Burden in Villupuram District of Tamil Nadu, India. Indian J Community Med 2021, 46(4):657-661.

- de Souza DK, Ahorlu CS, Adu-amankwah S, Otchere J, Mensah SK, Larbi IA, Mensah GE, Biritwum N-k, Boakye DA: Community-based trial of annual versus biannual single-dose ivermectin plus albendazole against Wuchereria bancrofti infection in human and mosquito populations : study protocol for a cluster randomised controlled trial. Trials 2017, 18:448.

- Mehta PK, Maharjan M: Assessment of antigenemia among children in four hotspots of filarial endemic districts of Nepal during post-MDA surveillance. Trop Med Health 2023, 51(1):47.

- Pi-bansa S, Osei JHN, Kartey-Attipoe WD, Elhassan E, Agyemang D, Otoo S, Dadzie SK, Appawu MA, Wilson MD, Koudou BG et al: Assessing the Presence of Wuchereria bancrofti Infections in Vectors Using Xenomonitoring in Lymphatic Filariasis Endemic Districts in Ghana. Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease 2019, 4:49.

- Biritwum NK, Frempong KK, Verver S, Odoom S, Alomatu B, Asiedu O, Kontoroupis P, Yeboah A, Hervie ET, Marfo B et al: Progress towards lymphatic filariasis elimination in Ghana from 2000-2016: Analysis of microfilaria prevalence data from 430 communities. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2019, 13(8):e0007115.

- N. T. D. Modelling Consortium Lymphatic Filariasis Group: The roadmap towards elimination of lymphatic filariasis by 2030: insights from quantitative and mathematical modelling [version 1; peer review: 2 approved]. Gates Open Res 2019, 3:1538.

- World Health Organization: NTD Roadmap 2021–2030. World Health Organization 2019:1-25.

- Biritwum NK, de Souza DK, Marfo B, Odoom S, Alomatu B, Asiedu O, Yeboah A, Hervie TE, Mensah EO, Yikpotey P et al: Fifteen years of programme implementation for the elimination of Lymphatic Filariasis in Ghana: Impact of MDA on immunoparasitological indicators. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2017, 11(3):e0005280.

- General Report Volume 3A: Population of Regions and District.

- Mofa: Mpohor. In.; 2018: Web page-Web page.

- Mofa: Ahanta West. In.; 2018: Web page-Web page.

- Ghana Statistical S: 2010 Population & Housing Census: Regional Analytical Report - Upper East Region. In.; 2013: 1-196.

- Ghana Statistical S: 2010 Population & Housing Census: District Analytical Report - Mpohor District. In.; 2014: 1-68.

- Mofa: Kassena Nankana: Physical and Natural Environment. In.; 2018: Web pages-Web pages.

- Mofa: Bongo. In.; 2018: Web page-Web page.

- WHO/Department of control of neglected tropical diseases: Lymphatic filariasis: monitoring and epidemiological assessment of mass drug administration - A manual for national elimination programmes. In: LYMPHATIC FILARIASIS. Edited by Ichimori K. WHO Press, World Health Organization, 20 Avenue Appia, 1211 Geneva 27, Switzerland: WHO; 2011: xviii, 79 p.

- Chesnais CB, Vlaminck J, Kunyu-Shako B, Pion SD, Awaca-Uvon NP, Weil GJ, Mumba D, Boussinesq M: Measurement of Circulating Filarial Antigen Levels in Human Blood with a Point-of-Care Test Strip and a Portable Spectrodensitometer. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2016, 94(6):1324-1329.

- Chesnais CB, Missamou F, Pion SD, Bopda J, Louya F, Majewski AC, Weil GJ, Boussinesq M: Semi-quantitative scoring of an immunochromatographic test for circulating filarial antigen. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2013, 89(5):916-918.

- de Souza DK, Otchere J, Ahorlu CS, Adu-Amankwah S, Larbi IA, Dumashie E, McCarthy FA, King SA, Otoo S, Osabutey D et al: Low Microfilaremia Levels in Three Districts in Coastal Ghana with at Least 16 Years of Mass Drug Administration and Persistent Transmission of Lymphatic Filariasis. Trop Med Infect Dis 2018, 3:105.

- Dickerson JW, Eberhard ML, J. LP: A technique for microfilarial detection in preserved blood using nuclepore filters. J Parasitol 1990, 76(6):829-833 PMID: 2123924.

- Derua YA, Rumisha SF, Batengana BM, Max DA, Stanley G, Kisinza WN, Mboera LEG: Lymphatic filariasis transmission on Mafia Islands, Tanzania: Evidence from xenomonitoring in mosquito vectors. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2017, 11(10):e0005938.

- Rao RU, Atkinson LJ, Ramzy RMR, Helmy H, Farid HA, Bockarie MJ, Susapu M, Laney SJ, Williams SA, Weil GJ: A real-time PCR-based assay for detection of Wuchereria bancrofti DNA in blood and mosquitoes. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2006, 74(5)::826–832.

- Zhong M, McCarthy J, Bierwert L, Lizotte-Waniewski M, Chanteau S, Nutman TB, Ottesen EA, Williams SA: A Polymerase Chain Reaction Assay for Detection of the Parasite Wuchereria bancrofti in Human Blood Samples. 1996, 54(4):357–363.

- Opoku M, Minetti C, Kartey-Attipoe WD, Otoo S, Otchere J, Gomes B, de Souza DK, Reimer LJ: An assessment of mosquito collection techniques for xenomonitoring of anopheline-transmitted Lymphatic Filariasis in Ghana. Parasitology 2018, 145:1783–1791.

- Aboagye-Antwi F, Kwansa-Bentum B, Dadzie SK, Ahorlu CK, Appawu MA, Gyapong J, Wilson MD, Boakye DA: Transmission indices and microfilariae prevalence in human population prior to mass drug administration with ivermectin and albendazole in the Gomoa District of Ghana. Parasit Vectors 2015, 8:562.

- Amuzu H, Wilson MD, Boakye DA: Studies of Anopheles gambiae s.l (Diptera: Culicidae) exhibiting different vectorial capacities in lymphatic filariasis transmission in the Gomoa district, Ghana. Parasites & Vectors 2010, 3:85.

- Appawu MA, Dadzie SK, Baffoe-Wilmot A, Wilson MD: Lymphatic filariasis in Ghana: entomological investigation of transmission dynamics and intensity in communities served by irrigation systems in the Upper East Region of Ghana. Tropical Medicine and International Health 2001, 6(7):511-516.

- Boakye DA, Baidoo HA, Glah E, Brown C, Appawu M, Wilson MD: Monitoring lymphatic filariasis interventions: Adult mosquito sampling, and improved PCR - based pool screening method for Wuchereria bancrofti infection in Anopheles mosquitoes. Filaria J 2007, 6:13.

- Boakye DA, Wilson MD, Appawu MA, Gyapong J: Vector competence, for Wuchereria bancrofti, of the Anopheles populations in the Bongo district of Ghana. Ann Trop Med Parasitol 2004, 98(5):501-508.

- Ughasi J, Bekard HE, Coulibaly M, Adabie-Gomez D, Gyapong J, Appawu M, Wilson MD, Boakye DA: Mansonia africana and Mansonia uniformis are Vectors in the transmission of Wuchereria bancrofti lymphatic filariasis in Ghana. Parasites & Vectors 2012, 5:89.

- Ughasi JC, Berkard H, Gomez D, Appawu M, Wilson MD, Boakye DA: Mansonia species are potential vectors of lymphatic filariasis in Ghana. American Journal Of Tropical Medicine And Hygiene 2010, 83(5):302-302.

- Pi-Bansa S, Osei JHN, Joannides J, Woode ME, Agyemang D, Elhassan E, Dadzie SK, Appawu MA, Wilson MD, Koudou BG et al: Implementing a community vector collection strategy using xenomonitoring for the endgame of lymphatic filariasis elimination. Parasit Vectors 2018, 11:672.

- Kyelem D, Biswas G, Bockarie MJ, Bradley MH, El Setouhy M, Fischer PU, Henderson RH, Kazura JW, Lammie PJ, Njenga SM et al: Determinants of Success in National Programs to Eliminate Lymphatic Filariasis: A Perspective Identifying Essential Elements and Research Needs. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2008, 79(4):480–484.

- World Health Organization: Integrating neglected tropical diseases into global health and development: fourth WHO report on neglected tropical diseases. In. Edited by IGO LCB-N-S. Geneva; 2017.

- World Health O: Global Programme to Eliminate Lymphatic Filariasis: Progress Report 2000-2009 and Strategic Plan 2010-2020. World Health Organization 2010:1-93.

- Biritwum NK, Yikpotey P, Marfo BK, Odoom S, Mensah EO, Asiedu O, Alomatu B, Hervie ET, Yeboah A, Ade S et al: Persistent 'hotspots' of lymphatic filariasis microfilaraemia despite 14 years of mass drug administration in Ghana. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 2016, 110:690-695.

- Osei-Atweneboana MY, Awadzi K, Attah SK, Boakye DA, Gyapong JO, Prichard RK: Phenotypic evidence of emerging ivermectin resistance in Onchocerca volvulus. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2011, 5(3)::e998.

- Mehta PK, Maharjan M: Assessment of microfilaremia in 'hotspots' of four lymphatic filariasis endemic districts of Nepal during post-MDA surveillance. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2024, 18(1):e0011932.

| Region | District | Community | Community Population Size | Sample Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Western | HAhanta West | Antseambua | 215 | 162 |

| Asemkow | 938 | 389 | ||

| CMpohor | Ampeasem | 734 | 348 | |

| Obrayebona | 1972 | 496 | ||

| Upper East | HKassena Nankana West | Badunu | 1159 | 422 |

| Navio (Sanwu) Central | 733 | 348 | ||

| CBongo | Atampiisi Bongo | 1207 | 455 | |

| Balungu Nabiisi | 1450 | 428 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).