1. Introduction

Follicular lymphoma (FL) is considered an indolent disorder with a relatively favorable outcome [

1,

2]. It is the second most common non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) in developed countries, accounting for approximately 20-25% of NHL worldwide [

3,

4]. Several immunochemotherapeutic (ICT) combinations or a regimen of lenalidomide and rituximab remain valid options for many patients [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9]. Rituximab maintenance as a post-induction consolidation strategy is well established by the phase III PRIMA and GALLIUM studies [

10,

11]. Most patients achieve long-term remissions, with median survival rates of almost 20 years [

10,

11]. However, while the main aims of achieving remission and improve quality of life have been met, there are several other unmet needs: first, to improve survival in the 15-20% of patients who are refractory to initial treatment or who experience disease progression during the first two years after first-line therapy (POD24) [

12,

13,

14]; second, to mitigate the toxicity of anti-CD20 maintenance for patients who achieve full metabolic remission [

15].

In order to address these unmet needs, various clinical, molecular, pathological, and imaging biomarkers have been shown to predict survival rates at the time of diagnosis and could be used to determine the optimal therapy. However, many of these tools are inaccessible in daily clinical practice and have not been sufficiently tested [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24]. Several studies confirm that results of end-of-induction (EOT) positron emission tomography (PET) after ICT strongly predict the progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) [

25,

26]. Likewise, EOT minimal residual disease (MRD) has an impact on prognostic [

27]. In cases of absence of OS benefit and increased risk of infection with frontline antibody maintenance, using PET might be relevant to guide the therapeutic approach; even more so in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic and the high infection rate [

10,

11,

15,

28]. Dynamic risk assessment using EOT PET [

15,

29] or EOT PET plus MRD measured by Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) of the t(14;18) translocation is currently under evaluation as a response-adapted treatment platform. Nevertheless, when using PET and/or MRD at EOT, patients have already undergone the complete cycle of ICT. If the results from interim PET would be equally predictive, they would allow for earlier identification of patients with a high risk of poor outcomes and could facilitate anticipated interventions (including potentially earlier changes in therapy).

On the contrary of classical Hodgkin lymphoma or diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) [

31,

32,

33,

34], the prognostic value of results from iPET in FL is yet to be established. Some studies suggest that positive iPET results are associated with poorer PFS [

35,

36,

37], while others indicate that they are not prognostic [

38,

39]. Recently, our group and Fernández-Miranda et al. showed that cfDNA MRD positivity in liquid biopsy during an interim evaluation had a prognostic impact on PFS in a small group of patients treated with first-line ICT [

40,

41]. This shows that cfDNA MRD could be complementary to iPET results to establish a prognosis and adapt the therapy.

The primary aim of this study was to determine if iPET could identify patients with FL at high risk of relapse after receiving systemic frontline therapy (mainly ICT) and establish a proof of concept for a platform designed for clinical trials of response-adapted treatment following only four cycles of initial ICT. Moreover, we aimed to evaluate the additional predictive value of cfDNA MRD.

2. Materials and Methods

Patients

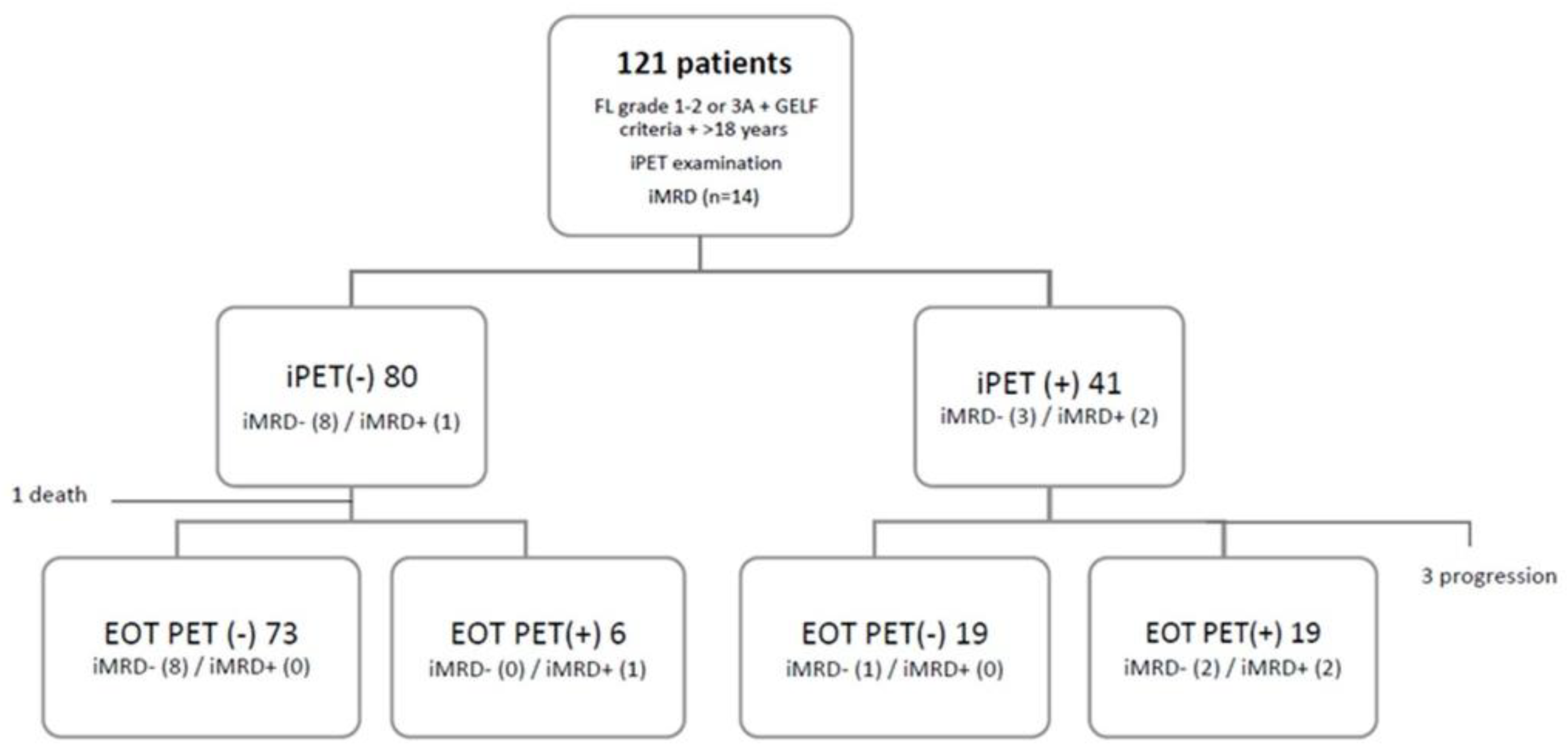

We retrospectively evaluated newly diagnosed FL patients who received first-line therapy and underwent basal, interim (after four cycles of therapy ), and EOT PET scans between 2012 and 2022 at three academic hospitals from the GELTAMO (Grupo Españolde Linfomas/Trasplante Autólogo de Médula Ósea) group (Hospital Universitario 12 de Octubre, Instituto Catalán de Oncología and Complejo Hospitalario de Toledo). The inclusion criteria were the following: (1) being over 18 years; (2) having a histologically confirmed FL grade 1-2 or 3A; (3) fulfilling GELF (Groupe D’Etude des Lymphomes Folliculaires) criteria at the moment of initiating systemic treatment; (4) having an iPET scan. We obtained clinical, laboratory, treatment, and PET examination data. Additionally, interim cfDNA data was available for 14 of them (

Figure 1).

Analysis of PET/CT Imaging

All patients were required to fast for at least 6 hours prior to the PET scan. Basal, interim, and EOT PET scans were performed by expert nuclear medicine radiologists who were blinded to patient outcomes. PET examinations were performed using either the General Electric Discovery MI (GEDMI) scanner or the Siemens Biograph 6 scanner, following injection of 2.5-5 MBq/Kg 2-deoxy-2-[fluorine-18]fluoro- D-glucose (FDG). PET scans obtained with a low-dose protocol were used for anatomic localization and attenuation correction of the PET images. PET scans were scored by experienced PET physicians using Deauville score (DS) standards in agreement with Lugano classification definitions: (1) no uptake above background; (2) uptake ≤ mediastinum; (3) uptake > mediastinum but ≤ liver; (4) uptake > liver; and (5) uptake markedly > liver or area of new disease [

42]. A positive PET result was defined by a DS of 4 or 5, while scores 1-3 were considered negative or complete response (CR). The maximum standardized uptake value (SUVmax) was recorded during both the basal and interim PET scans. In cases where PET scans did not show FDG uptake, the SUVmax was recorded as 1. We calculated the ΔSUVmax by dividing the difference in SUVmax between the basal PET and interim PET by the basal SUVmax. When basal SUVmax was inferior to 10 we considered not assessable [

43]. Histological transformation (HT) to high-grade B-cell lymphoma was suspected due to imaging or clinical changes and was confirmed by performing a tissue biopsy.

Baseline Genotyping and iMRD

Lymph node genomic DNA and plasma cfDNA basal samples were sequenced with a short-length Ampliseq Custom Panel on an Ion S5 System platform (Life Technologies, Thermo Fisher Scientific) with an average coverage of 2,150x, as previously described [

40] (

Supplementary Table 1).

All somatic mutations were screened through follow-up cfDNA liquid biopsies. A median of 14.4 ng/mL of plasma (range 2 - 489 ng/mL) was obtained from two 8mL EDTA tubes. We calculated the cfDNA interim minimal residual disease (iMRD) value for each sample, including demultiplexing, false positive rate control, and biological and technical noise correction following a previously described bioinformatic pipeline [

40] (

Supplementary Table 2).

Statistics

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS® Statistics, V21.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The primary endpoint was PFS, measured from the date of treatment initiation until the date of disease progression, death from any cause, or last follow-up. Disease progression was determined through an imaging evaluation and suspicion of HT was confirmed or ruled out by biopsy. OS was defined as the time from initiation of treatment to death from any cause or last follow-up. Univariate and multivariate Cox regressions were used to evaluate links between demographic, clinical and analytical prognostic factors and both PFS or OS, with hazard ratios (HR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI). The value of the most important prognostic scores (FLIPI, FLIPI2 and PRIMA-PI) was also analyzed. iPET and EOT PET values were also determined by Cox regression and Kaplan-Meier curves. All statistical tests were two-sided and a cut-off p value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Patient Characteristics

Baseline characteristics of the 121 patients are shown in

Table 1. The median age at diagnosis was 62 years (range 27-87), 52% of patients were male, and 75% of patients had FL grade 1-2. Most patients (92.5%) had advanced Ann-Arbor stage and only 24% had B symptoms at the time of diagnosis. High-risk FLIPI, FLIPI2, and PRIMA-PI scores were observed for 58%, 46%, and 31.5% of patients, respectively. Patients received treatment a median of one month (range 0-94) after diagnosis.

Only 17 patients (14%) were initially assigned to a watch-and-wait strategy. All of them were finally treated because of achieving GELF criteria. Consistently with current management strategies for FL (6,9,11), 78% of patients (n=94) received R-CHOP (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone) treatment, whereas 20% (n=24) underwent R-B (rituximab and bendamustine) treatment. The remaining 3 patients received anti-CD20 or duvelisib. Of the 118 patients receiving ICT; 114 (97%) completed 6 cycles. Four patients (3%) only received four cycles because of disease progression (n=3) or sepsis-related death (n=1). Most patients (87%) underwent rituximab maintenance, which was not administered to 15 patients because of adverse events (n=6), physician decision (n=2), intercurrent malignancy (n=2), or other unknown reasons (n=5).

The median follow-up period for all patients was 34 months (range 3-115). During the follow-up period, excluding 3 patients (2.5%) who were ICT refractory to therapy , 19 patients (15.7%) experienced POD24 after ICT, whereas 13 patients (10.7%) relapsed more than 24 months after receiving ICT. Twelve patients died, with 3 deaths being attributed to lymphoma progression, 2 to secondary neoplasia, and 7 to infectious complications. The 5-year PFS and OS rates were 64% (95% CI 58%-69%) and 88% (95% CI 84%-92%), respectively. During follow-up 3 patients showed HT to high-grade B-cell lymphoma at 6, 10, and 72 months

3.2. Risk Factors for Progression-Free Survival Analysis

Univariate analysis revealed that the following factors were related to an inferior PFS rate: more than 4 nodal areas, an elevated β2 microglobulin, hemoglobin levels below 12g/dL, elevated serum lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), and not receiving rituximab maintenance. Only nodal areas and rituximab maintenance were also significantly associated with PFS in multivariate analysis. (

Table 2). A prior watch-and-wait strategy or type ICT regimen (Rituximab Bendamustine vs R-CHOP) did not predict worse outcomes. None of the prognostic factors analyzed demonstrated a prognostic impact on OS rates.

We also analyzed the prognostic implications of FLIPI, FLIPI2, and PRIMA-PI scores (

Supplementary Figure 1). All three indexes were prognostic of PFS outcomes and FLIPI had the highest sensitivity index (82%) in detecting a relapse, and its positive predictive value was 40%. The prognostic impact of these scores was not evidenced in patients who received R-B treatment, probably because of their limited number.

3.3. PET Analysis

DSs for interim and EOT PET scans are documented in

Supplementary Table 3. Of the interim PET scans, 12 patients (10%) were classified as DS1, 27 (22%) as DS2, 40 (33%) as DS3, 31 (26%) as DS4, and 9 (8%) as DS5. Overall, 40 patients (34%) were considered iPET(+). Of them, three patients were classified as having refractory disease and were therefore excluded from the PFS analysis. One patient died before completing six cycles of ICT. An EOT PET scan was assessable for 114 patients (as mentioned before 4 didn’t finish induction and 3 patients were evaluated by TC). A DS of 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 were assigned to 27 patients (23%), 26 patients (22%), 35 patients (30%), 17 patients (15%), and 9 patients (8%), respectively (

Supplementary Table 3). Overall, 26 patients (23%) were considered EOT PET (+). DS1 was more frequently observed in EOT PET than in iPET, while DS4 was less commonly reported in EOT PET. Basal SUVmax was obtained for 113 patients (93%), with a median of 12.7 (range 4-57.2). Interim SUVmax was recorded for 99 patients (82%), with a median of 3 (range 1-37.9); of those, 36 (36%) showed values greater than 3.7. Additionally, we could calculate the ΔSUVmax in 57 patients.

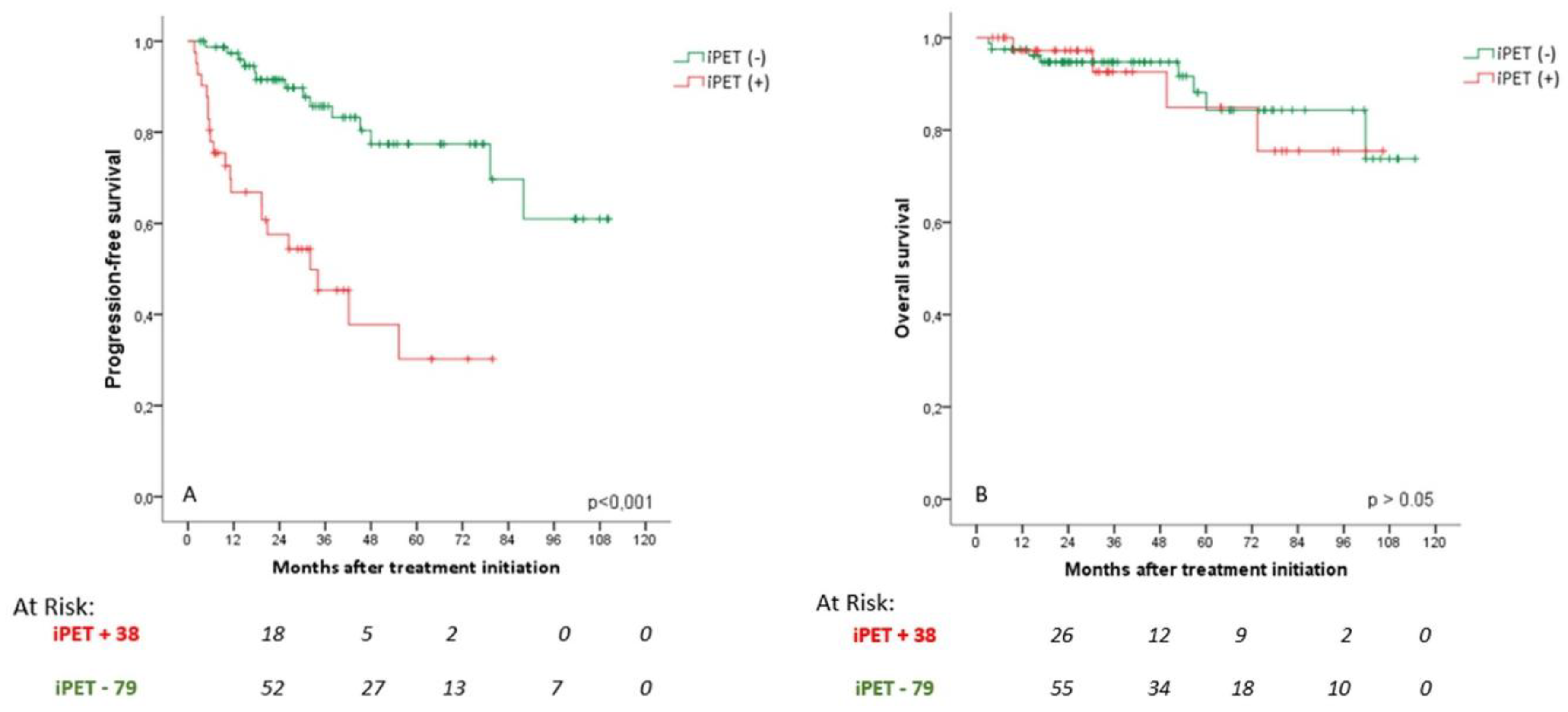

3.4. Prognostic Value of iPET

The estimated 5-year PFS rate was 77% for patients with a negative iPET in comparison with 30% for those with a positive iPET (HR 4.3, 95% CI 2.1-8.9; p < 0.001) (

Figure 2A). No significant difference in OS was observed (

Figure 2B).A percentage of 34% and 7.6% of patients with iPET(+) and (-) experienced POD24, respectively (HR 7.9, 95% CI 2.8-22.4; p < 0.001). Negative iPET scores showed a negative predictive value of 94% for POD24.The PFS curves overlapped for patients with an iPET DS of 1, 2, or 3, as well as for patients with DS of 4 or 5. Thus, we continued to categorize DS3 as iPET(-) (

Supplementary Figure 2A). The patients with DS5 (n=9) did not show a higher rate of POD24 than patients with DS4 (n=31) (2-year PFS rate of 44.4% vs 60.4%, p = 0.767)

Interim ∆SUVmax was not a significant predictor of PFS, although it presented a trend towards significance (p = 0.087). Patients with a ∆SUVmax of less than 71% had a 5-year PFS of 46% (95% CI 26%-67%) in comparison with 86% (95% CI 80%-92%) for those with ∆SUVmax greater or equal to 71% (

Supplementary Figure S3).

In a multivariate analysis including variables associated with lower PFS rate (nodal areas > 4, elevated β2 microglobulin, hemoglobin < 12g/dL, elevated LDH, rituximab maintenance, high-risk FLIPI, and high-risk PRIMA-PI), an iPET(+) and high-risk FLIPI were significant predictors of PFS (HR 4.2, 95% CI 1.7-10.3, p = 0.022; and HR 3.7, 95% CI 1.2-11.0, p = 0.021, respectively).

3.5. Prognostic Value of EOT PET

The EOT CR rate was 81.5%. The EOT PET findings were predictive of relapse, as patients with EOT PET (+) had a 2-year PFS of 48.5% in comparison with 90.9% of those with EOT PET(-) (HR 5.1, 95% CI 2.5-10.4, p < 0.001) (

Supplementary Figure 4A). Among the patients with EOT PET(+), 60% (15 out of 25) relapsed in a median of 7 months (range 4-55); among patients with EOT PET(-), 18.5% (17 out of 92) relapsed in a median of 26 months (range 10-88). We did not observe a significant difference in OS between patients with EOT PET(+) and EOT PET(-) (

Supplementary Figure 4B). A total of 48% and 7.7% of patients with EOT PET(+) and (-) presented POD24, respectively (HR 11.1, 95% CI 3.7-33.3, p<0.001). As previously described for iPET, PFS curves overlapped for patients with an EOT PET DS of 1, 2, or 3 and DS 4 and 5 (

Supplementary Figure 2B).

In a multivariate analysis including variables associated with lower PFS rate, we obtained similar results as for iPET: EOT PET and high-risk FLIPI remained significant predictors of PFS (HR 4.6, 95% CI 1.5-13.6, p = 0.007 and HR 3.5, 95% CI 1.2-10.6, p = 0.026).

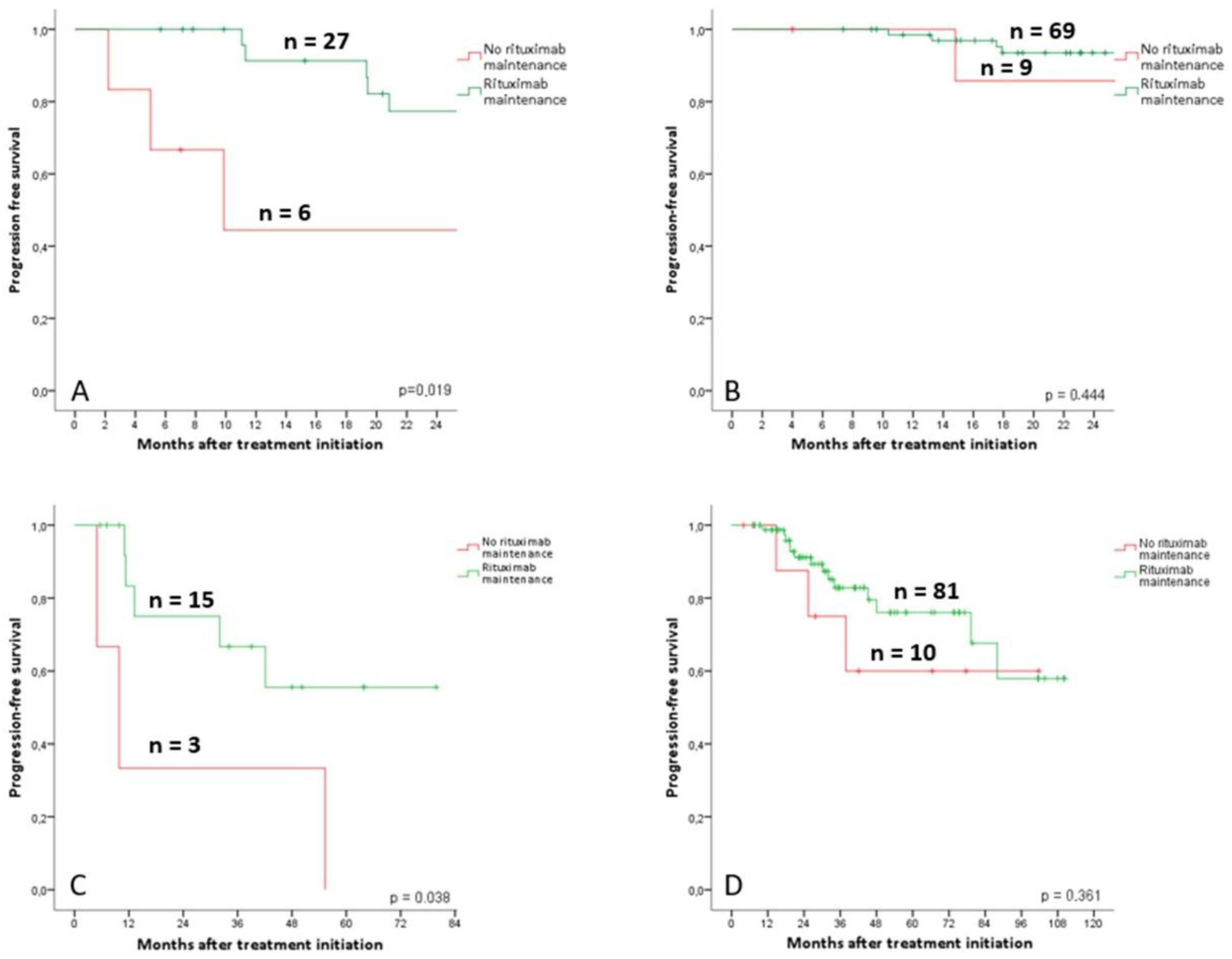

3.6. Rituximab Maintenance Value According to PET Response

In the subgroup of 33 patients with iPET(+) we observed a lower rate of POD24 in the patients under rituximab maintenance (2-year PFS of 44% for patients with no rituximab maintenance, and 77% for patients under rituximab maintenance, p = 0.019) (

Figure 3A). In the subgroup of 78 patients with iPET(-), rituximab maintenance was not relevant to predict POD24 (2-year PFS of 94 for patients with no rituximab maintenance, and % vs 86% for patients under rituximab maintenance, p = 0.444) (

Figure 3B).

Similar to iPET, in the 18 patients with EOT PET(+), rituximab maintenance was predictive of better outcomes of POD24 (2-year PFS 33% for patients with no rituximab maintenance vs 75% for patients under rituximab maintenance, p = 0.038) (

Figure 3C). In the 91 patients with EOT PET(-), rituximab maintenance did not predict a lower rate of disease progression (2-year PFS 86% for patients with no rituximab maintenance vs 91%% for patients under rituximab maintenance, p = 0.361) (

Figure 3D).

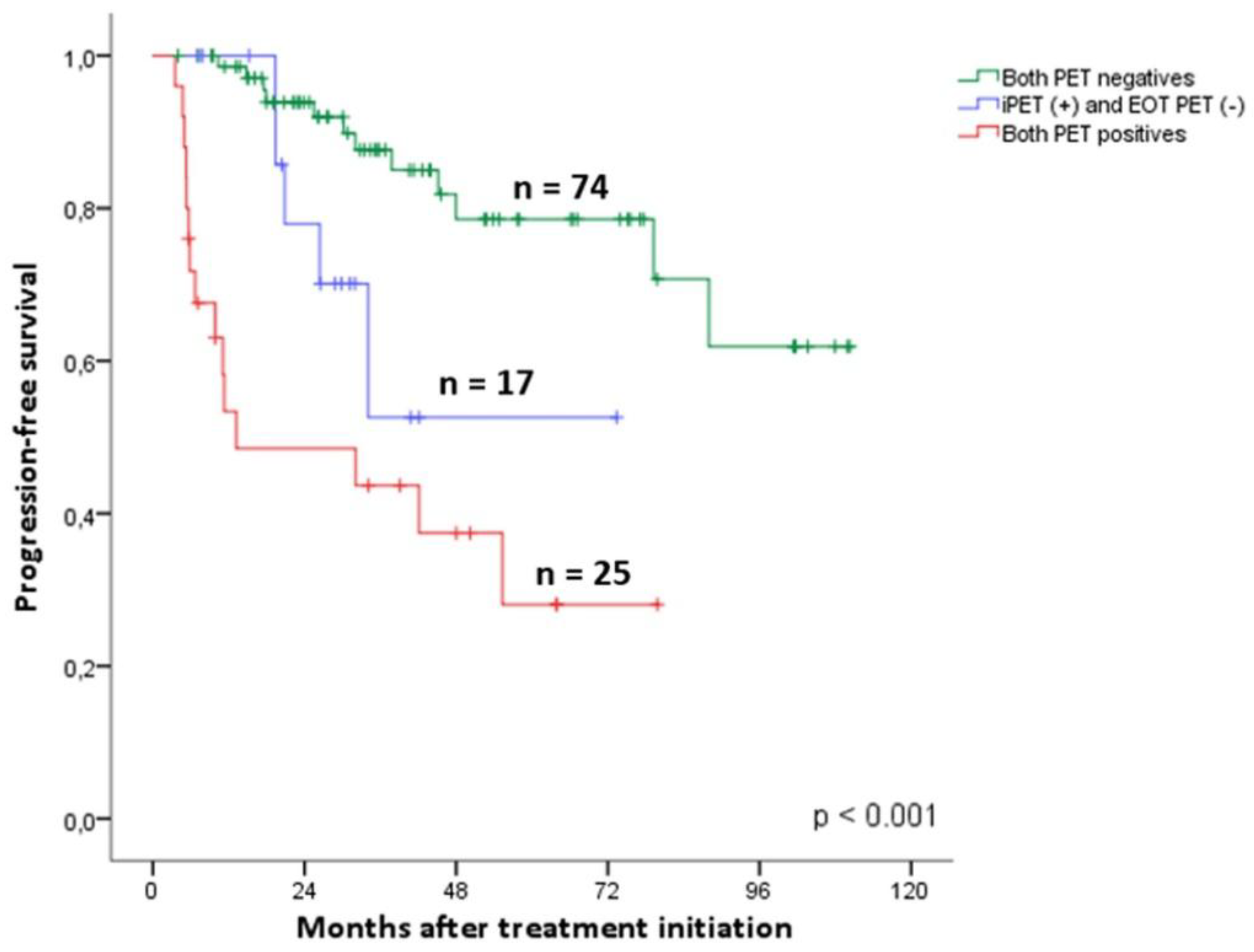

3.7. Dynamics of PET Analysis

Patients who converted from a positive iPET to a negative EOT PET (n=17) had inferior PFS than those who had both examinations negative (n=74, HR 3.2, CI 95% 1.1-9.7, p = 0.039). Also, we observed no statistical differences between patients with both examinations positive (n=25) and patients with a positive iPET and negative EOT PET (n=17, HR 2.6, CI 95% 0.9-7.4, p = 0.081). (

Figure 4).Conversion from a negative iPET to a positive EOT PET was very rare (4 patients), 2 of which showed disease progression at 5 and 13 months. After more than 4 years of follow-up, the other 2 remained progression-free (see section cfDNA analysis for more information).

3.8. cfDNA Analysis

A total 14 patients had iMRD measurements by cfDNA after four cycles of ICT [

40]. 3 patients tested iMRD(+) and 11 were iMRD(-). All patients with a positive iMRD experienced a relapse at 6, 11, and 31 months after the initiation of ICT. Only one patient with a negative iMRD progressed after 19 months of cycle 1 R-CHOP treatment [

40]. The test showed a specificity of 91% and a sensitivity of 100% in detecting progression.

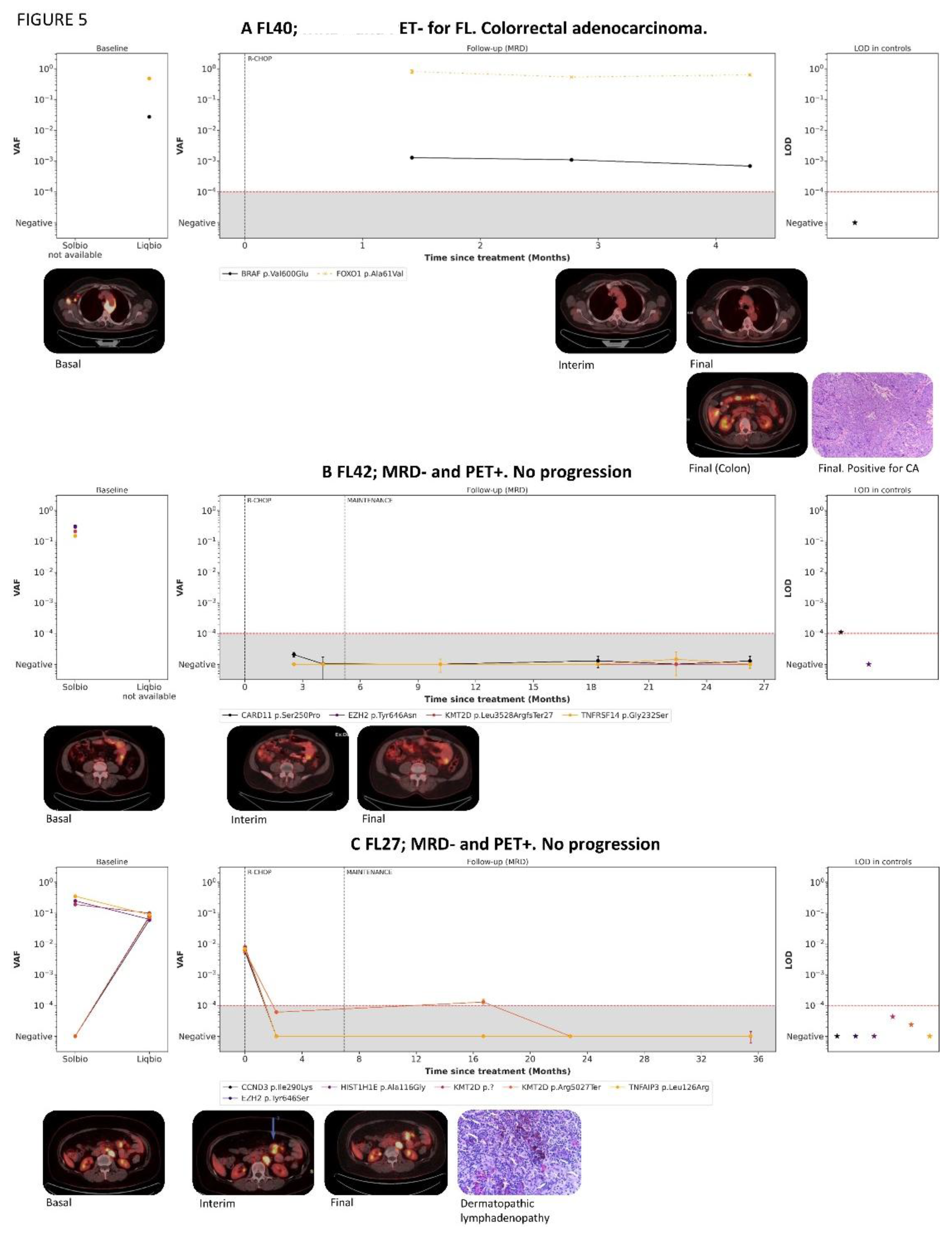

Two out of the 3 patients with iMRD(+) had a positive iPET. The remaining patient was a 67-year-old woman diagnosed with FL in an advanced stage with gastric and bone infiltration. She received six cycles of R-CHOP treatment with no significant side effects. However, the EOT PET resulted in an incidental mass in the transverse colon. Upon biopsy, the mass was diagnosed as colorectal adenocarcinoma. MRD analysis found that the mutation BRAF V600E, which corresponds to the solid tumor, was present in all of the samples, including the initial sample acquired at the time of FL diagnosis, 6 months prior to the detection of the adenocarcinoma (

Figure 5A).

Of the 11 patients with iMRD(-), 3 showed a positive iPET (DS4) but only 1 patient presented disease progression. Of the other two, the first (

Figure 5B) was a 69-year-old male diagnosed with FL grade 1-2, exhibiting bulky disease and gut infiltration, intermediate FLIPI and low PRIMA-PI. In the basal PET, the SUVmax was low (5.72). He was treated with 6 cycles of R-CHOP and both interim and EOT PET were DS4 (SUVmax 2.62) with increased gut metabolic activity. After treatment, a biopsy did not detect evidence of lymphoma. Rituximab maintenance treatment was initiated, and after the administration of 6 rituximab doses, the PET showed CR (DS3). The second patient (

Figure 5C) was a 60-year-old female diagnosed with FL grade 3A, Ann-Arbour stage 3, high LDH levels, and no bone marrow or extranodal infiltration. The basal PET showed high SUVmax (22.52) and infiltration in 4 supra and infradiaphragmatic nodal regions. After 4 cycles of R-CHOP treatment, the iPET showed a partial response (DS4, SUVmax 7.44). Following the sixth cycle and completion of induction, the EOT PET remained partial response (DS4) because of mesenteric lymphadenopathies with high metabolic activity (SUVmax 12.79) and the appearance of a new submandibular lymphadenopathy. The biopsy of this last lymphadenopathy revealed dermatopathic lymphadenopathy. Subsequently, rituximab maintenance was initiated and after 3 cycles the PET showed CR.

4. Discussion

This retrospective study is one of the largest examining the prognostic value of iPET scans in FL frontline therapy, and the only one specifically designed to test the complementary value of cfDNA in this context. Additionally, we analyzed the prognostic significance of EOT PET scans and assessed other clinical and analytical risk factors associated with disease progression. Consistent with current management strategies for FL [

6,

9,

10], most patients received treatment with R-CHOP and underwent rituximab maintenance. The fraction of patients that experienced POD24 was similar to previously reported rates [

13,

14].

The PET scan responses assessed by DS, SUVmax, and ∆SUVmax were similar to those previously described [

36,

37]. The iPET was a strong predictor of PFS; supporting data recently published by Merryman et al, who proved iPET to be a significant predictor of PFS in FL patients [

37]. In the multivariate analysis, only iPET(+) and high-risk FLIPI were significant for PFS, indicating that a dynamic evaluation of responses could better identify patients who require early intervention [

30,

40]. Interestingly, patients with a DS of 4-5 on an iPET scan (observed in 34% of FL grade 1–3A patients) who later showed a negative EOT PET had inferior PFS than those for whom both scans were negative. These findings suggest that iPET imaging could help identify patients with a negative EOT PET who are at high risk of relapse. In contrast, only a small fraction of patients with a DS of 1-3 on an iPET scan had POD24 in comparison with the patients with a DS of 4–5. Although it should take with care, the lower POD24 rates observed in the patients under rituximab maintenance in the iPET(+) subgroup is of particular interest.

PET has a crucial role in initial staging and EOT response assessment in FL [

42]. EOT PET has been proven to be highly predictive of prognosis within FL patients’ group [

25,

26]. However, few studies evaluated the prognostic value of iPET scans [

35,

36,

37,

38,

39]. Nearly all these studies used older PET response criteria (e.g., International Harmonization Project criteria) and were limited by small sample sizes. More recently, Merryman and colleagues investigated the use of DS for the interpretation of iPET scans in a retrospective cohort of 128 patients with FL grade 1-3B [

37]. Interim PET scans were performed after 2-4 cycles of ICT and proved to be a significant predictor of PFS. Patients who had DS of 4-5 had worse PFS rates than those who had DS of 1-2 [

37].

Developing response-adapted clinical trials on the basis of only PET scans has some limitations, such as the tests’ limited sensitivity and specificity and the subjective radiologist interpretation of the results [

44,

45]. One important finding of this study is the added value of using a LiqBio-MRD in an early interim evaluation. This test showed a specificity of 91% and a sensitivity of 100% in detecting progression in 14 patients after 4 cycles of ICT treatment. This suggests that it can be used to identify patients who required alternative treatment strategies during the natural course of FL. Moreover, two patients with iPET(+) did not progress (

Figure 5B and C), which resulted to be false positives of the PET technique. Another patient who did not progress during the study showed a positive iMRD test (mutation BRAF V600E) and was later diagnosed with adenocarcinoma.

From a translational/clinical perspective, these findings indicate that the use of PET for the evaluation of response in FL has the potential to serve as a tool for designing response-adapted treatment strategies. In recent years, the clinical need for response-adapted maintenance led to the use of EOT PET for guiding treatment in three different clinical trials [

29,

30,

46]. In the FOLL12 clinical trial a 807 patients were randomly assigned b to receive response-adapted ICT treatment guided by PET and molecular studies. The authors hypothesized that intensifying interventions for patients with the highest putative risk of poor survival, defined as those with persistent evidence of illness on the basis of molecular evaluation (MRD-positive) and metabolic imaging (PET-positive), would yield the greatest impact on outcomes Although with unfavorable global results [

30]., this study demonstrates the feasibility of a response-adapted approach in FL using EOT PET scans. Additionally it is important to mention, that unlike our LigBio-MRD analysis, MRD analysis was conducted by real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR), , leaving up to 40% of FL cases ineligible for MRD assessment. Several studies in DLBCL [

47,

48], cHL [

49], and more recently in FL [

40,

41,

50] confirm that a liquid biopsy MRD analysis by Next Generation Sequencing based on somatic mutations is an emerging non-invasive test that can detect malignancy, monitor treatment response, and define treatment with high accuracy.

Considering our findings, iPET evaluation should be considered as a valuable biomarker for FL patients receiving frontline ICT. It could also be used to define treatment-adapted clinical trials, particularly when combined with LiqBio MRD. Earliest use of Immune-based therapies (e.g., CAR T cell therapy, bispecific antibodies) could be a promising alternative for iPET (+) and/or LiqBio MRD patients who are likely to have poor outcomes with ICT treatments.

To our knowledge, this is the second study exploring the significance of ΔSUVmax in iPET scans of first-line FL patients. In contrast to Merryman’s findings [

37], we cannot strongly propose an optimal ΔSUVmax threshold for further investigation in prospective clinical trials.

Our study has some limitations, such as the small sample size and the limited follow-up in an indolent disease. Nevertheless, 97.5% of the patients received ICT, leading to a homogeneous cohort of 118 patients. The main inconvenience of the study is the absence of a centralized nuclear medicine radiologist to review all the PET scans. Nevertheless, most patients underwent evaluation at nearly two occasions to avoid potential bias. We recognize other important sources of variability among our study cohorts, such as the differences in the generation of PET scanners utilized. However, it is worth noting that all patients underwent iPET assessments with the same timing. Despite the need to perform larger studies to further confirm our findings, our preliminary LiqBio MRD data, demonstrate a promising proof-of-principle for using cfDNA in early response evaluation for FL patients under first-line treatment (mainly first line ICT)

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, the data suggests that a positive iPET scan can predict PFS and POD24 in first-line FL patients. Furthermore, the LiqBio MRD preliminary data indicate that it may complement PET scans and help to identify both false-positive patients and CR patients who are at risk of early progression. These findings suggest that iPET should be explored as a tool for response-adapted treatment strategies in FL patients.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org, Supplementary_figures, Supplementary_Tables.

Author Contributions

MP: SB, and AJ-U designed the research. AM, GF, IZ, RI and SB defined the bioinformatic pipeline and performed sequencing analysis., MP, PL-P, GF, IZ, RI, AC-O, TB, AR-I, CG, PS, ER, MC, RA, MC, JM-L, and AJ-U provided patient samples and clinical data. All authors analyzed and interpreted the data. MP, SB, and AJ-U wrote the manuscript, which was approved by all authors.

Funding

This study has been funded by Instituto de Salud Carlos III, (ISCIII) and co-funded by the European Union through the projects, PI21/00314, CP22/00082, and CRIS cancer foundation.

Institutional Review Board Statement

: All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

Alejandro Martin-Muñoz, is employee of Altum Sequencing Co. Rosa Ayala, and Joaquín Martínez are equity shareholders of Altum Sequencing Co. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.Abbreviations.

References

- Cheah CY, Chihara D, Ahmed M, Davis RE, Nastoupil LJ, Phansalkar K, et al. Factors influencing outcome in advanced stage, low-grade follicular lymphoma treated at MD Anderson Cancer Center in the rituximab era. Ann Oncol 2016;27:895–901. [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Ubieto A, Grande C, Caballero D, Yáñez L, Novelli S, Hernández-Garcia MT, et al. Autologous stem cell transplantation for follicular lymphoma: favorable long-term survival irrespective of pretransplantation rituximab exposure. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2017;23:1631–40. [CrossRef]

- Anderson JR, Armitage JO, Weisenburger DD. Epidemiology of the non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas: Distributions of the major subtypes differ by geographic locations. Ann Oncol 1998;9(7):717-20. [CrossRef]

- Bastos-Oreiro M, Muntañola A, Panizo C, González-Barca E, Villambrosia S, Córdoba R, et al. RELINF: prospective epidemiological registry of lymphoid neoplasms in Spain. A project from the GELTAMO group. Ann Hematol 2020;99(4):799-808. [CrossRef]

- Flinn IW, van der Jagt R, Kahl BS, Wood P, Hawkins TE, Macdonald D, et al. Randomized trial of bendamustine-rituximab or R-CHOP/R-CVP in first-line treatment of indolent NHL or MCL: the BRIGHT study. Blood 2014; 123: 2944–2952. [CrossRef]

- Hiddemann W, Kneba M, Dreyling M, Schmitz N, Lengfelder E, Schmits R, et al. Frontline therapy with rituximab added to the combination of cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (CHOP) significantly improves the outcome for patients with advanced-stage follicular lymphoma compared with therapy with CHOP alone: results of a prospective randomized study of the German Low-Grade Lymphoma Study Group. Blood 2005;106(12):3725-32. [CrossRef]

- Morschhauser F, Fowler NH, Feugier P, Bouabdallah R, Tilly H, Palomba ML, et al. Rituximab plus lenalidomide in advanced untreated follicular lymphoma. N Engl J Med 2018;379: 934–947. [CrossRef]

- Marcus R, Davies A, Ando K, Klapper A, Opat S, Owen C, et al. Obinutuzumab for the first-line treatment of follicular lymphoma. N Engl J Med 2017; 377:1331–1344. [CrossRef]

- Bachy E, Seymour JF, Feugier P, Offner F, López-Guillermo A, Belada D, et al. Sustained Progression-Free Survival Benefit of Rituximab Maintenance in Patients With Follicular Lymphoma: Long-Term Results of the PRIMA Study. J Clin Oncol 2019;37(31):2815-2824. [CrossRef]

- Salles G, Seymour JF, Offner F, López-Guillermo A, Velada D, Xerri L, et al. Rituximab maintenance for 2 years in patients with high tumour burden follicular lymphoma responding to rituximab pluschemotherapy (PRIMA): A phase 3, randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2011;377:42-51.

- Marcus R, Davies A, Ando K, Klapper W, Opat S, Owen C, et al. Obinutuzumab for the First-Line Treatment of Follicular Lymphoma. N Engl J Med 2017;377(14):1331-1344. [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Ubieto A, Grande C, Caballero D, Yáñez L, Novelli S, Hernández MT, et al. Progression-free survival at 2 years post-autologous transplant: a surrogate endpoint for overall survival in follicular lymphoma. Cancer Med 2017;6:2766–74. [CrossRef]

- Casulo C, Dixon JG, Le-Rademacher J, Hoster E, Hochster H, Hiddemann W, et al. Validation of POD24 as a robust early clinical endpoint of poor survival in FL from 5225 patients on 13 clinical trials. Blood 2022;139:1684–93. [CrossRef]

- Murakami S, Kato H, Higuchi Y, Yamamoto K, Yamamoto H, Saito T, et al. Prediction of high risk for death in patients with follicular lymphoma receiving rituximab plus cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisolone in first-line chemotherapy. Ann Hematol 2016;95(8):1259-69. [CrossRef]

- Zhang L, Ghielmini M, Cheson BD, Ujjani C. Pros and cons of rituximab maintenance in follicular lymphoma. Cancer Treat Rev 2017;58:34-40. [CrossRef]

- Federico M, Bellei M, Marcheselli L, Luminari S, Lopez-Guillermo A, Vitolo U, et al. Follicular Lymphoma International Prognostic Index 2: A New Prognostic Index for Follicular Lymphoma Developed by the International Follicular Lymphoma Prognostic Factor Project. J Clin Oncol 2009;27(27):4555-62. [CrossRef]

- Solal-Céligny P, Roy P, Colombat P, White J, Armitage JO, Arranz-Saez R, et al. Follicular Lymphoma International Prognostic Index. Blood 2004;104(5):1258-65. [CrossRef]

- Bachy E, Maurer MJ, Habermann TM, Gelas-Dore B, Maucort-Boulch D, Estell JA, et al. A simplified scoring system in de novo follicular lymphoma treated initially with immunochemotherapy. Blood 2018;132(1):49-58. [CrossRef]

- Mondello P, Fama A, Larson MC, Feldman AL, Villasboas JC, Yang ZZ, et al. Lack of intrafollicular memory CD4 + T cells is predictive of early clinical failure in newly diagnosed follicular lymphoma. Blood Cancer 2021;11(7):130. [CrossRef]

- Mir F, Mattiello F, Grigg A, Herold M, Hiddemann W, Marcus R, et al. Follicular Lymphoma Evaluation Index ( FLEX ): A new clinical prognostic model that is superior to existing risk scores for predicting progression-free survival and early treatment failure after frontline immunochemotherapy. Am J Hematol 2020;95(12):1503-10. [CrossRef]

- Pastore A, Jurinovic V, Kridel R, Hoster E, Staiger AM, Szczepanowski M, et al. Integration of gene mutations in risk prognostication for patients receiving first-line immunochemotherapy for follicular lymphoma: a retrospective analysis of a prospective clinical trial and validation in a population-based registry. Lancet Oncol 2015;16(9):1111-22. [CrossRef]

- Jurinovic V, Kridel R, Staiger AM, Szczepanowski M, Horn H, Dreyling MH, et al. Clinicogenetic risk models predict early progression of follicular lymphoma after first-line immunochemotherapy. Blood 2016;128(8):1112-20. [CrossRef]

- Huet S, Tesson B, Jais JP, Feldman AL, Magnano L, Thomas E, et al. A gene expression profiling score for prediction of outcome in patients with follicular lymphoma: a retrospective training and validation analysis in three international cohorts. Lancet Oncol 2018;19:549–61. [CrossRef]

- Meignan M, Cottereau AS, Versari A, Chartier L, Dupuis J, Boussetta S, et al. Baseline Metabolic Tumor Volume Predicts Outcome in High–Tumor-Burden Follicular Lymphoma: A Pooled Analysis of Three Multicenter Studies. J Clin Oncol 2016;34(30):3618-26. [CrossRef]

- Trotman J, Barrington SF, Belada D, meignan M, MacEwan R, Owen C, et al. PET investigators from the GALLIUM study. Prognostic value of end-of-induction PET response after first-line immunochemotherapy for follicular lymphoma (GALLIUM): secondary analysis of a randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2018;19:1530–1542. [CrossRef]

- Dupuis J, Berriolo-Riedinger A, Julian A, Brice P, Tychyj-Pinel C, Tilly H, et al. Impact of [(18)F]fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography response evaluation in patients with high-tumor burden follicular lymphoma treated with immunochemotherapy: a prospective study from the Groupe d’Etudes des Lymphomes de l’Adulte and GOELAMS. J Clin Oncol 2012;30(35):4317-22. [CrossRef]

- Galimberti S, Luminari S, Ciabatti E, Grassi S, Guerrini F, Dondi A, et al. Minimal residual disease after conventional treatment significantly impacts on progression-free survival of patients with follicular lymphoma: the FIL FOLL05 trial. Clin Cancer Res 2014;20:6398–405. [CrossRef]

- Levavi H, Lancman G, Gabrilove J. Impact of rituximab on COVID-19 outcomes. Ann Hematol. 2021;100(11):2805-2812. [CrossRef]

- Trotman J, Presgrave P, Carradice DP, Lenton DS, Gandhi MK, Cochrane T, et al. Lenalidomide Consolidation Added to Rituximab Maintenance Therapy in Patients Remaining PET Positive After Treatment for Relapsed Follicular Lymphoma: A Phase 2 Australasian Leukaemia & Lymphoma Group NHL26 Study. Hemasphere 2023;7(3):e836. [CrossRef]

- Luminari S, Manni M, Galimberti S, Versari A, Tucci A, Boccomini C, et al.Response-adapted postinduction strategy in patients with advanced-stage follicular lymphoma: the FOLL12 study. J Clin Oncol 2022;40:729–39. [CrossRef]

- Johnson P, Federico M, Kirkwood, Fossa A, Berkahn L, Carella A, et al. Adapted treatment guided by interim PET-CT scan in advanced Hodgkin’s lymphoma. N Engl J Med 2016;374:2419–2429. [CrossRef]

- Borchmann P, Goergen H, Kobe C, Lohri A, Greil R, Eichenauer DA, et al. PET-guided treatment in patients with advanced-stage Hodgkin’s lymphoma (HD18): final results of an open-label, international, randomised phase 3 trial by the German Hodgkin Study Group. Lancet 2017;390:2790–2802.

- Casasnovas R-O, Bouabdallah R, Brice P, Lazarovici J, Ghesquieres H, Stamatoullas A, et al. PET-adapted treatment for newly diagnosed advanced Hodgkin lymphoma (AHL2011): a randomised, multicentre, non-inferiority, phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol 2019;20:202–215. [CrossRef]

- Dührsen U, Müller S, Hertenstein B, Thomssen H, Kotzerke J, Mesters R, et al. Positron emission tomography-guided therapy of aggressive non-Hodgkin lymphomas (PETAL): a multicenter, randomized phase III trial. J Clin Oncol 2018;36:2024–2034. [CrossRef]

- Boo SH, O JH, Kwon SJ, Yoo IR, Kim SH, Park GS, et al. Predictive value of interim and end-oftherapy 18F-FDG PET/CT in patients with follicular lymphoma. Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2019;53:263–269. [CrossRef]

- Dupuis J, Berriolo-Riedinger A, Julian A, Brice P, Tychyj-Pinel C, Tilly H, et al. Impact of [18 F] fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography response evaluation in patients with high–tumor burden follicular lymphoma treated with immunochemotherapy: a prospective study from the Groupe d’Etudes des Lymphomes de l’Adulte and GOELAMS. J Clin Oncol 2012;30:4317–4322. [CrossRef]

- Merryman RW, Michaud L, Redd R, Mondello P, Park H, Spilberg G, et al. Interim Positron Emission Tomography During Frontline Chemoimmunotherapy for Follicular Lymphoma. Hemasphere 2023;7(2):e826. [CrossRef]

- Bishu S, Quigley JM, Bishu SR, Olsasky SM, Stem RA, Shostrom VK, et al. Predictive value and diagnostic accuracy of F-18-fluoro-deoxy-glucose positron emission tomography treated grade 1 and 2 follicular lymphoma. Leuk Lymphoma 2007;48:1548–1555. [CrossRef]

- Lu Z, Lin M, Downe P, et al. The prognostic value of mid- and post-treatment [(18)F]fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) positron emission tomography (PET) in indolent follicular lymphoma. Ann Nucl Med. 2014;28:805–811. 22. Zhou Y, Zhao Z, Li J, et al. [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Ubieto A, Poza M, Martin-Muñoz A, Ruiz-Heredia Y, Dorado S, Figaredo G, et al. Real-life disease monitoring in follicular lymphoma patients using liquid biopsy ultra-deep sequencing and PET/CT. Leukemia. 2023;37(3):659-669. [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Miranda I, Pedrosa L, Llanos M, Franco FF, Gómez S, Martín-Acosta P, et al. Monitoring of Circulating Tumor DNA Predicts Response to Treatment and Early Progression in Follicular Lymphoma: Results of a Prospective Pilot Study. Clin Cancer Res. 2023;29(1):209-220. [CrossRef]

- Cheson BD, Fisher RI, Barrington SF, Cavalli F, Schwartz LH, Zucca E, et al. Recommendations for initial evaluation, staging, and response assessment of Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphoma: the Lugano classification. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(27):3059-3068. [CrossRef]

- Kurch L, Hüttmann A, Georgi TW, Rekowski J, Sabri O, Schmitz C, et al. Interim PET in Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma. J Nucl Med. 2021;62(8):1068-1074. [CrossRef]

- Barrington SF, Mir F, El-Galaly TC, Knapp A, Nielsen TG, Sahin D, et al. Follicular Lymphoma Treated with First-Line Immunochemotherapy: A Review of PET/CT in Patients Who Did Not Achieve a Complete Metabolic Response in the GALLIUM Study. J Nucl Med. 2022;63(8):1149-1154. [CrossRef]

- Ansell SM, Armitage JO. Positron Emission Tomographic Scans in Lymphoma: Convention and Controversy. Mayo Clin Proc. 2012;87(6):571-580. [CrossRef]

- Pettitt AR, Barrington S, Kalakonda N, Khan UT, Jackson R, Carruthers S, et al. NCRI PETREA TRIAL: A PHASE 3 EVALUATION OF PET-GUIDED, RESPONSE-ADAPTED THERAPY IN PATIENTS WITH PREVIOUSLY UNTREATED, ADVANCED-STAGE, HIGH-TUMOUR-BURDEN FOLLICULAR LYMPHOMA. Hematol Oncol 2019;37: 67-68. [CrossRef]

- Kurtz DM, Soo J, Co Ting Keh L, Alig S, Chabon JJ, Sworder BJ, et al. Enhanced detection of minimal residual disease by targeted sequencing of phased variants in circulating tumor DNA. Nat Biotechnol 2021;39(12):1537–47. [CrossRef]

- Kurtz DM, Scherer F, Jin MC, Soo J, Craig AFM, Esfahani MS, et al. Circulating tumor DNA measurements as early outcome predictors in diffuse Large B-cell lymphoma. J Clin Oncol 2018;36(28):2845-2853. [CrossRef]

- Spina V, Bruscaggin A, Cuccaro A, Martini M, Di Trani M, Forestieri G, et al. Circulating tumor DNA reveals genetics, clonal evolution, and residual disease in classical Hodgkin lymphoma. Blood 2018;131(22):2413-2425. [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Ubieto A, Martín-Muñoz A, Poza M, Dorado S, García-Ortiz A, Revilla E, et al. Personalized monitoring of circulating tumor DNA with a specific signature of trackable mutations after chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy in follicular lymphoma patients. Front Immunol 2023;14:1188818. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).