1. Introduction

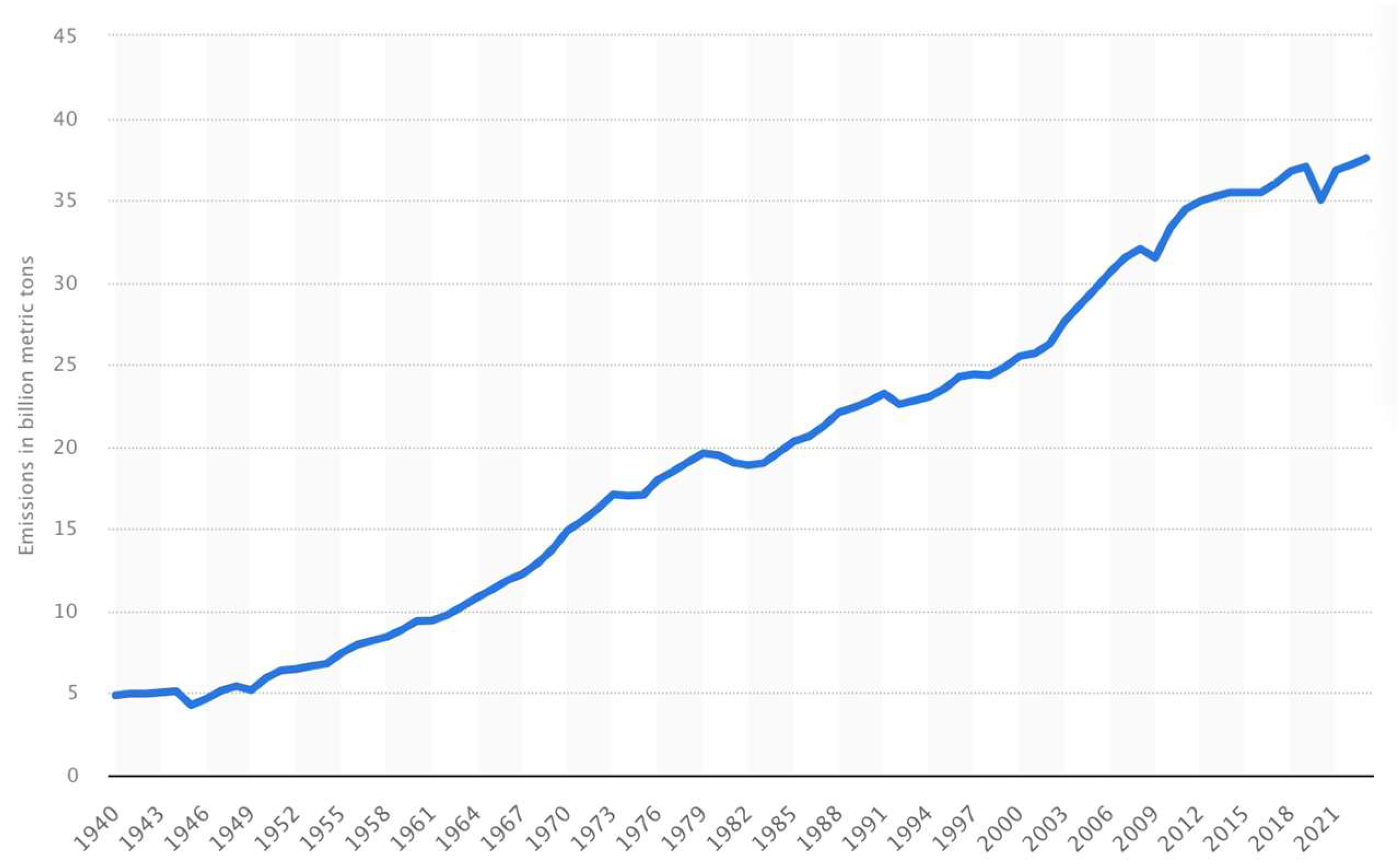

Greenhouse gas emission (GHG) is a global issue that has made stakeholders continually formulate policies to control it; yet, its emission is increasing (

Figure 1). Using 1990 as a baseline period, stakeholders in environmental sustainability expect a 60% GHG emission reduction in 2050 [

1]. In 2015, these stakeholders reached an agreement in Paris, termed the Paris Agreement, on the need to maintain an average global temperature of 2oC. Currently, stakeholders in environmental sustainability agreed that a robust national action policy is required to achieve a 2021 follow-up agreement on climate change that was held in Glasgow [

2]. One objective of the National action policy is to address the issue of urbanisation, which has led to an increase in GHG emissions [

2].

Urbanisation is inevitable in today's global economy [

3]. This need has made the campaign against climate change challenging because scholarly reports have shown that the transportation sector is the major contributor to carbon emissions globally because it has failed to implement efficient decarbonisation strategies for GHG emissions [

4,

5,

6,

7]. The emissions come from the transportation modes – road, marine, rail and air – used to transport humans and goods worldwide [

8,

9]. The machinery used for transportation are major source of GHG gases such as carbon dioxide (CO

2), methane (CH

4), and nitrous oxide (N

2O) [

10]. These gases are the by-products of fossil fuels used as the major energy source in transportation systems [

11].

Figure 1.

Global CO

2 emission [

12].

Figure 1.

Global CO

2 emission [

12].

Today’s volume of transportation sector calls for an urgent need to minimise greenhouse gases, especially CO

2, which have adverse environmental consequences on our planet – such as the depletion of natural resources [

2,

6,

13]. The current rise in global temperatures is among the environmental problems of CO

2 emissions [

14,

15]. By implication, this problem has led to extreme weather conditions, which have resulted in the ecosystem and biodiversity disruption [

4]. Human health and well-being have been on the receiving end of these disruptions [

4,

11]. Poor air quality in our environment resulting from air pollution and smog formation from transportation-related emissions are responsible for several public health problems, for example [

1,

16].

Stakeholders have recognised this problem by proposing frameworks that will assist communities in transit to sustainable transportation means - they will depend on low-carbon energy sources [

7]. First, the proposed frameworks have established the need for behavioural changes toward clean energy sources, such as solar energy [

17]. Second, their frameworks contain technological innovations that minimise dependence on fossil fuels for transporting humans and goods. Third, there is documentation on the policy interventions that seek to improve energy management in this sector. Lastly, some frameworks contain infrastructure improvements in the transportation industry towards a sustainable environment [

7]. Artificial intelligence (AI) integration in transportation systems is among the infrastructural improvements that will help to reduce carbon footprint in transportation systems.

AI integration in the transportation sector has several benefits that will help to solve some of the environmental impacts of this sector. For instance, this sector will enhance its safety, improve accessibility and increase its system reliability. Beyond these benefits, AI tools in the transportation sector will help to optimise different operations that are not limited to traffic management, logistics operations and route planning. Furthermore, AI tools can optimise fuel consumption, reduce greenhouse emissions, and improve this sector's overall efficiency.

This study’s objectives are tripartite: it provides an overview of carbon emissions in the transportation sector and discusses the justification for this emission reduction. Under this objective, the study examines recent challenges and the environmental impacts of carbon emissions from different sectors in the transportation industry, such as vehicles and ships. The second objective considered AI as a promising tool for managing and reducing carbon footprint in the transportation industry. Under this objective, this study reviewed different AI tools and algorithms regarding optimising greenhouse emissions, transportation networks, operations and energy consumption. The last objective deals with case studies and directions for further studies. Based on this study’s tripartite objectives, this study aims to contribute to the ongoing discussion on climate change mitigation strategies.

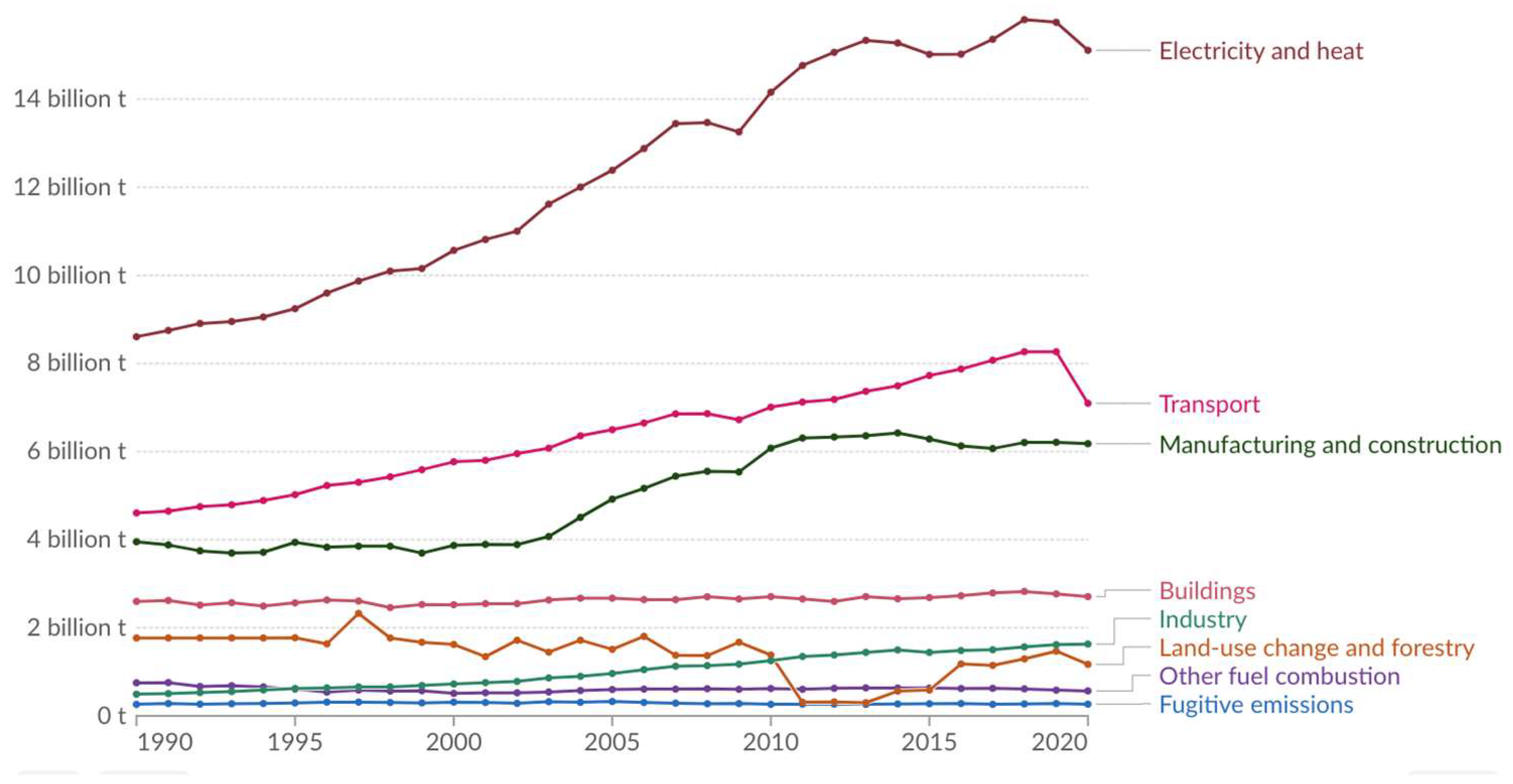

Figure 2.

Sectorial CO

2 emission [

18].

Figure 2.

Sectorial CO

2 emission [

18].

2. Carbon Emissions and Transportation systems

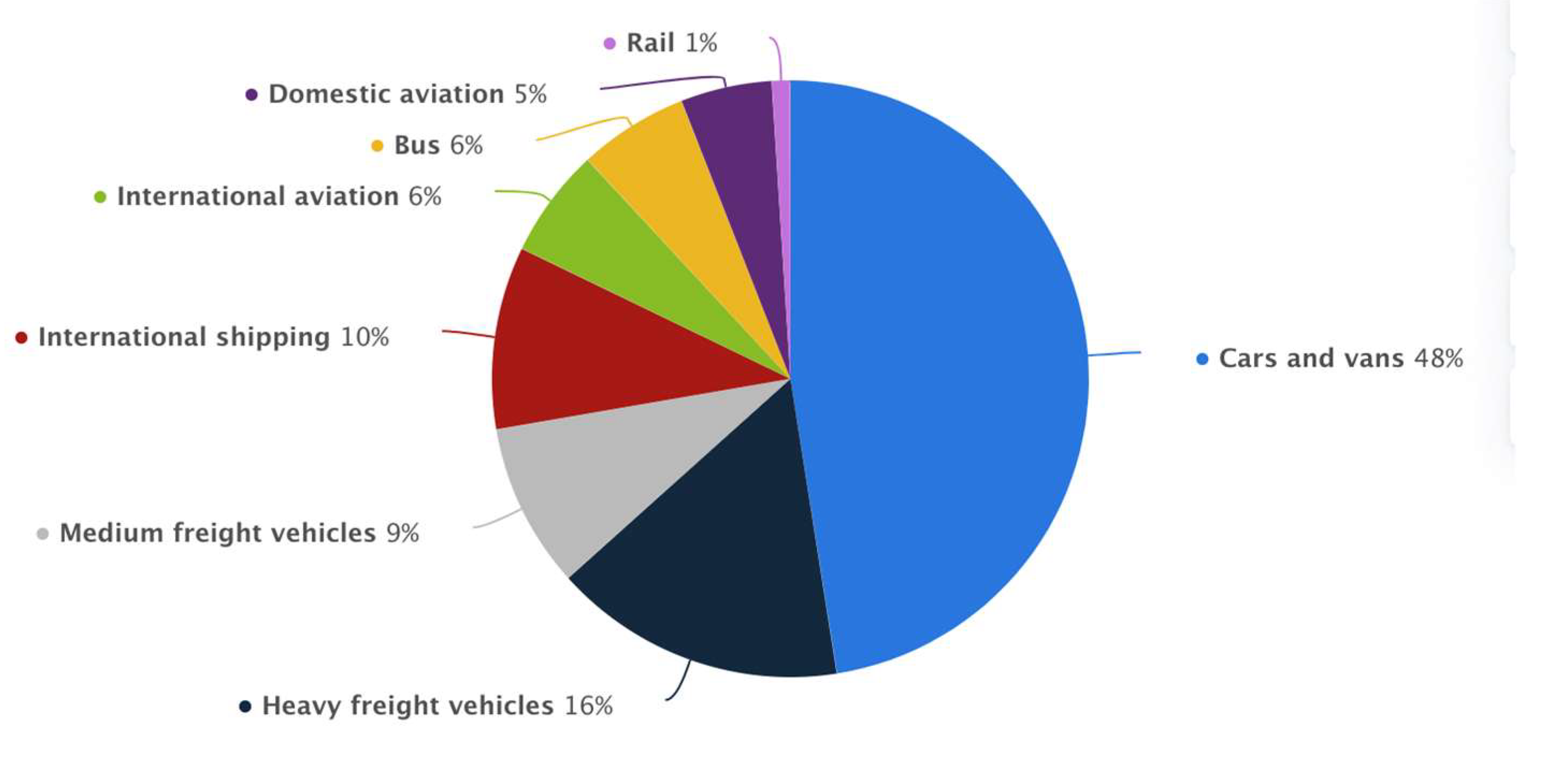

The increase in travelling and growth in global trade is responsible for the rise in carbon emissions from the transportation system [

19]. According to [

20], the contributions of the different transportation means are different, with road transport (cars, trucks, buses) about 48% of global CO2 emission (

Figure 3). This problem has led to the proliferation of electric vehicles (EVs), especially in developing countries such as the United States and England [

21,

22], to cut down on CO

2 emissions.

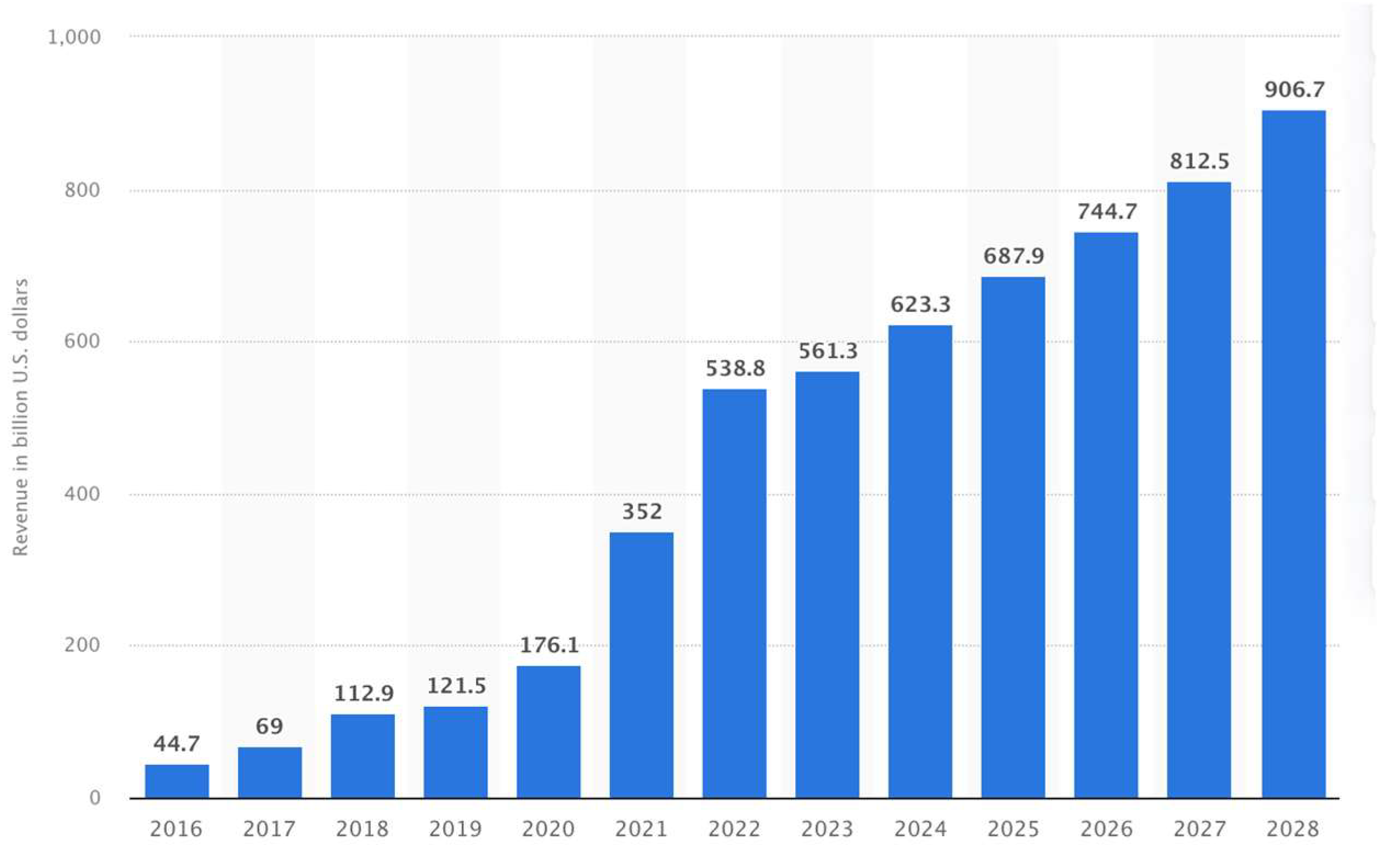

Figure 4 shows that the revenue from global sales of EVs is rising exponentially because of the campaign against climate change [

23].

Scholarly publications about climate change are among the reasons for the projected rise in EVs [

17]. This attempt to control climate change via technology has been recognised as an approach to mitigate GHG emissions from road transport systems [

17]. Technology and energy users' behaviours nexus will help to further mitigate against climate change [

17]. Behavioural change in road transport will improve human health due to pollutants reduction, such as dust and gases. For example, [

1] used a life cycle assessment approach to assess the GHG impact on the environment and human health. This approach enables them to establish that vehicles are the major contributors to CO

2 emissions into our environment. On the other hand, the NO

x from vehicles are responsible for human health problems. [

2] expanded the analysis of road transport on climate change from a circular economy perspective. They investigated the relationship between vehicle life cycle production and energy consumption based on three transportation scenarios – micro, meso, and macro transportation systems. The investigation showed that it is difficult to address climate change in a community where economic, societal and environmental sustainability is unbounded [

2].

[

24] established that public transportation modes are major carbon emission contributors compared to private transportation modes - they observed that more vehicles are used for public transportation than private. Based on this observation, they developed a system thinking model that improves carbon emissions from road transport systems. They recommended incorporating efficient pricing and prioritisation, transport mobility, and transport accessibility for improving quality public transportation. [

25] analysed the life-cycle carbon emissions in urban and rural settings from a private transportation perspective. They observed a 7.69% increase in life-cycle carbon emissions when a petrol-powered vehicle in a rural community (260 g) was compared with a similar vehicle in an urban setting. This difference is due to the prevalence of traffic in urban settings [

26].

[

27] investigated the environmental impacts of two transportation systems: road and rail transportation systems. Their methodology entails analysing carbon emissions from passengers using these transportation systems. They observed that an average of 1.58% increase in carbon emission would come from passengers using the road as a means of transportation when compared with when the same passengers use rail as a means of transportation (30 grCO

2epkm–1). Their study concluded that a rail transportation system is environmentally friendly when compared with a road transportation system. This conclusion aligns with the work of [

28]. They pointed out that the average carbon emissions from road and rail transport systems are 31.9 and 120.4 gCO

2/km, respectively. According to [

28], an aggregator system is required to control carbon emissions from road and rail transport systems. After investigating different policy scenarios that were aimed at aggregating these systems, they observed that Euro emissions standard implementation in the UK does not yield satisfactory results for carbon emission reduction. On the other hand, they found out that a policy that deals with changing of vehicle fleet enhance emission reduction.

The implementation of a vehicle fleet policy as a strategy for reducing carbon emissions yields better results when it is implemented using an inhomogeneous fleet with vehicles of different sizes [

29]. According to [

29], focusing fuel on consumption, instead of distance travelled, is a more reliable way of reducing carbon emissions. This assertion is based on the fact that a proportional relationship does not exist between a vehicle’s fuel consumption and distance travelled due to weight variation in a vehicle. Hence, they established that a vehicle's fuel consumption depends on its gross weight – net weight and actual payload. [

30] explained that drivers' driving style affects a vehicle's fuel consumption rate. Furthermore, they reported that tolling on roads affects fuel consumption, especially on roads with a non-electronic tolling system. Areas with non-electronic tolling systems can improve fuel consumption with a traffic control system [

31].

A traffic control system helps to reduce travelling time and road traffic congestion [

32]. These benefits have made scholars consider traffic emissions as a means of reducing carbon emissions [

32]. According to [

32], the intelligent-vehicle-based method is used to improve driving behaviours and reduce carbon emissions. The traffic-management-based method is another traffic control system, that is used to balance traffic emissions, hence optimising traffic schedules on a road network. Traffic control systems produce efficient results that optimise traffic delays and emissions are synergically analysed for a situation [

32]. According to [

33], vehicle speed management in traffic management is a viable approach to reducing carbon emissions, especially in residential communities. In practice, the bi-objective of reducing traffic and carbon emissions sometimes conflicts [

34]. To address this problem, [

34] recommended a Pareto optimisation approach for generating a compromise solution to get a win-win situation for traffic control and carbon emissions.

The trade-off between traffic control and carbon emissions is a complex problem [

35]. The complexity has made scholars apply different approaches towards reducing carbon emissions in the transport industry [

36,

37,

38]. For instance, traffic light optimisation has been used to reduce vehicles' carbon emissions in urban communities [

36]. This optimisation considered traffic flow and fuel consumption as the objective function, and they are optimised and solved using meta-heuristics such as differential evolution [

36]. [

35] modelled traffic flow, safety and carbon emission as a multi-objective optimisation problem. They considered this problem as a ramp metering problem. In the model, they included bottlenecks and feeders in the ramp metering algorithm. This inclusion allowed them to generate compromise solutions for traffic flow, safety and emissions.

AI model benefits have made it a promising tool for carbon emission management in the transport industry, especially road transport. AI implementation in road transport systems comes with several benefits: First, AI can generate real-time information about road traffic and carbon emissions. Second, AI implementation in transport systems does not require specialised skills. Third, the implementation cost of AI in transport systems is low when compared with other solutions for traffic control and carbon emissions monitoring. Lastly, AI implementation in road transport systems does not come with a bias because it reduces human interference with traffic control and carbon emisions monitoring. The next section contains a review of AI applications in road transport systems.

3. AI and Carbon Emission Nexus in the Road Transport System

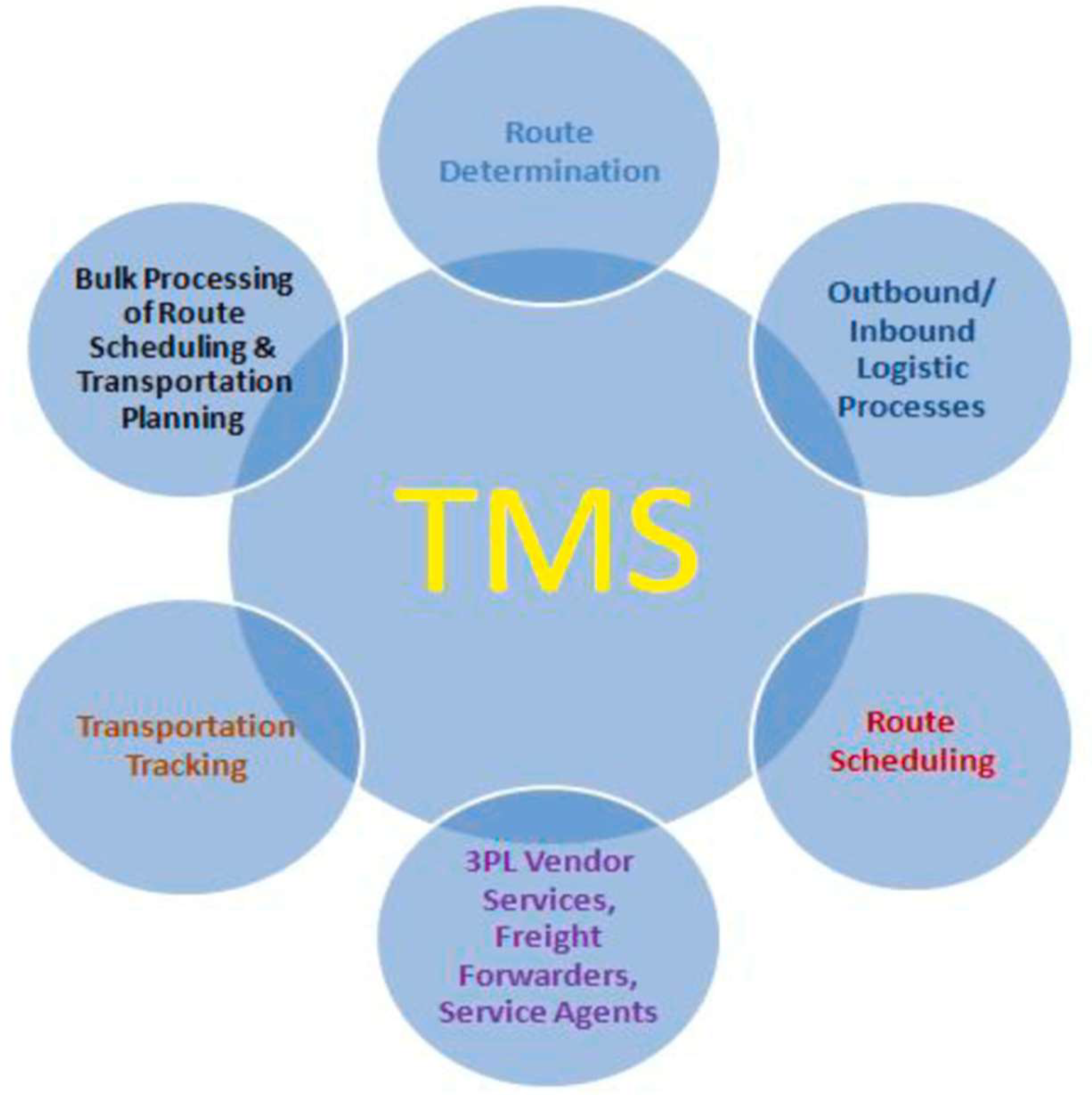

Intelligent transport system (ITS), AI applications in the transport sector, have found several applications in the transportation industry (

Figure 5). First, it has been established that ITS can address transportation tracking problems. Internet of Things [

39] and fuzzy logic [

40] are among the tools used for designing transportation tracking systems. Second, ITS generates information about route scheduling for transportation problems. Addressing this problem involves the application of meta-heuristics because of its complexity – genetic algorithm [

41], branch and cut algorithm [

42], and differential evolution algorithm [

43] have been successfully used to optimise a vehicle's route schedule.

The remaining paragraphs in this section focused on AI applications in road transport systems with an emphasis on carbon emissions.

3.1. Traffic Management

Traffic management has been transformed by AI implementation [

45,

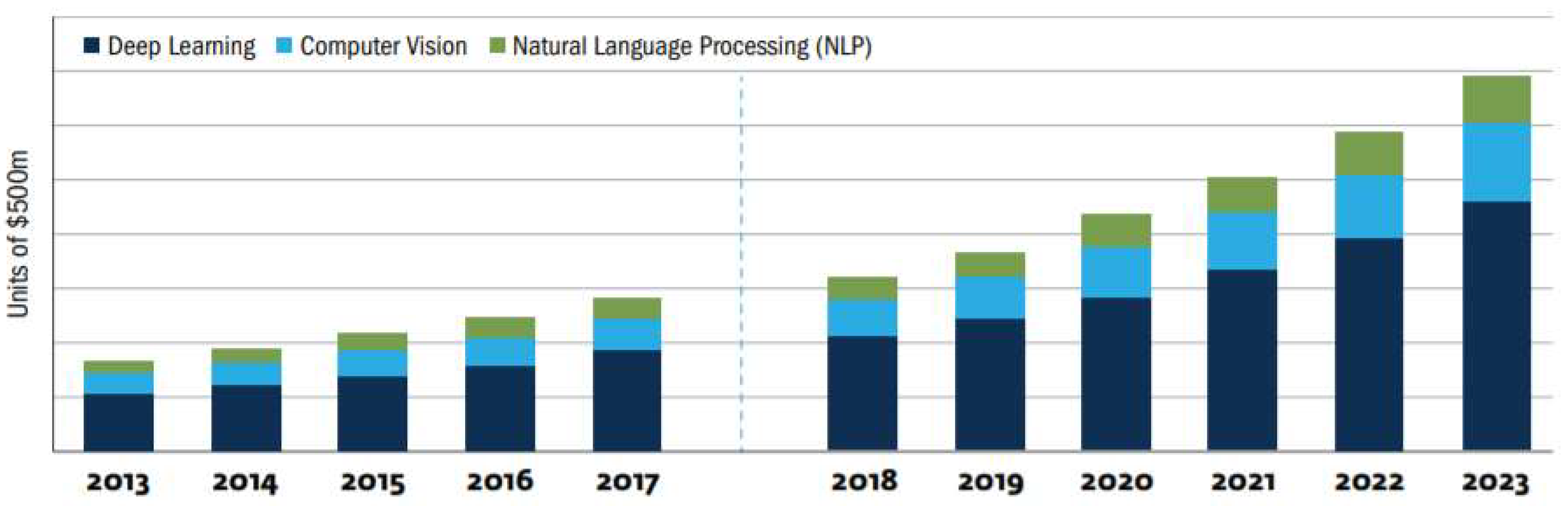

46]. AI has helped to improve traffic flow and safety in different communities. This improvement has led to an increase in AI in the transportation market (

Figure 6). With AI technologies, traffic prediction has been enhanced and optimised during long and short-term transportation within a community. The enhancement is due to the adoption of sensors and cameras that have impacted GPS devices' performance in supporting traffic congestion prediction and bottleneck in a road network. The prediction enables the implementation of proactive measures that enable timely congestion alleviation and travelling time reduction.

With AI technologies, historical data on road accidents have been analysed in order to identify patterns and implement strategies for safety measures’ implementations [

48]. Speed cameras and speed bumps are among the safety measures that traffic management authorities are deploying to improve road safety. These devices can minimise accidents’ likelihood in a community. Apart from this benefit, AI technologies have helped to improve decisions on road conditions and traffic flow [

49]. Furthermore, AI technologies have assisted experts in making informed decisions on infrastructure improvements, such as identifying areas where bridges or roads expanded, and should be constructed for improved traffic flow [

50].

Route management is another benefit of AI in road transport management [

51]. AI algorithms make it easier to consume less fuel by suggesting the best route that vehicles should use to optimise time and energy – this benefit improves ridership expectations [

52]. Autonomous vehicle proliferation is contained in the subset of AI technologies benefits in road transport systems [

53]. These vehicles have not only reduced road accidents but have also improved traffic flow and congestion in urban communities. They have made our roads to be safer and more sustainable for commuters.

3.2. Fuel Consumption

Reduction in fuel consumption is a major benefit of AI technology implementation in the road transport sector [

54]. AI technologies can predict the amount of fuel that a vehicle will consume to get to its destination [

30]. This prediction is carried out by rerouting vehicles to avoid congestion and bottlenecks as a means of minimising fuel consumption. The aggregation of this benefit reduces the amounts of CO

2 from road transport systems.

Autonomous vehicles can improve driving efficiency when compared with human drivers [

55]. They achieve this by minimising a vehicle’s acceleration and braking which has direct impacts on fuel consumption [

30]. The vehicle capacity of optimising routes has an impact on a vehicle's fuel usage. Furthermore, the use of AI technologies to optimise engine design and tyre efficiency helps to reduce vehicles' fuel consumption [

56]– thereby reducing CO

2 emission. AI technology's capacity to reduce CO

2 emissions is enormous through EV adoption. The presence of AI technologies in EVs allows these vehicles to process information about driving patterns and battery technology [

57]. This benefit has enhanced the transition from gasoline-powered vehicles to EVs which is a major boost to the fight against CO

2 emission.

3.3. CO2 Prediction

As mentioned previously, the transportation sector is a major contributor to CO

2; hence, CO

2 prediction from this sector is a major endeavour [

58]. There is a need to carry out this prediction accurately to support the fight against climate change. Scholars have identified AI as a robust tool for developing predictive models that will support policies about CO

2 emissions from the transport sector [

49]. AI algorithms use information about road conditions, fuel consumption, and traffic patterns to design models that generate information about vehicle CO

2 generation. In some models, vehicle characteristics, such as speed and acceleration, and weather conditions are considered as features for such predictive models [

59].

AI models can learn a vehicle’s attributes that are not apparent to humans based on historical data about a vehicle [

60]. The models achieve this task by learning from large data which are used to train the model and validate its accuracy. The training enables models to generate real-time information about CO

2 from a vehicle [

61]. Implementation of the information from the trained model helps to promote public transportation and EVs in urban centres. In addition, AI-based prediction enables stakeholders to select appropriate strategies for dealing with CO

2 emissions in the transport sector [

62].

4. Roles of Artificial Intelligence in Road Traffic Management

Studies have shown that traffic has a direct relationship with the volume of CO2 emission [

63,

64,

65]. Hence, scholarly reports have been presented on the importance of AI as a tool for managing traffic to minimise CO2 emissions. Some of the AI algorithms, that has found applications in road traffic management and the transportation sector include Artificial Neural Networks (ANN) [

63], Support Vector Machines (SVM) [

66], and Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO)[

67].

Table 1 presents some of the studies dedicated to the application of AI in traffic management, outlining the specific applications and locations.

[

61] used ANN to forecast short-term traffic conditions by analyzing traffic volume, speed, density, time and day-of-a week pattern. This helped planning routes better and reduced fuel consumption for vehicles operating in the area. Likewise, [

62] implemented LSTM neural networks to forecast traffic speed in China using real-time data from the field (travel time tables and traffic volume) for adaptive traffic signal control and route optimization. These studies demonstrate that the use of AI enables precise short-term traffic forecasts with which transport authorities can adjust traffic flows ahead of time to reduce idle time and thereby minimize emissions. In these densely populated urban areas, the models themselves bring about significant improvements in flow and CO₂ reduction.

Other AI technologies like deep learning and reinforcement learning have also been adopted in enhancing traffic management systems. [

68] used Reinforcement learning to dynamically modify traffic signal timings in real time by learning from pattern from pervious data. Benefiting from the advantages related to occupancy and speed, hybridization of algorithm such as ANN and genetic algorithms have also been found to be effective in traffic management [

69]. Another advantage of this approach is that it has the capability of simultaneously managing multiple objectives to ensure a compromise between traffic management and emission reduction.

[

68]AI-controller traffic management can also be incorporated into smart city infrastructure to minimize emission and enhance services. This would involve installation of Io-enabled sensors at intersection to monitor traffic and provide real-time data to AI algorithms for assessment. The output of this process is then used to control the traffic. the efficient control of traffic reduces commuting time and consequently emissions. Cities such as Barcelona and Amsterdam have incorporated adopted AI-driven technologies into their cities; these align urban mobility with sustainability goals [

71].

The implementation of AI-controlled traffic management although comes at a high cost of infrastructure including purchase of sensors, communication networks, and establishment of data centre, has its inherent long term benefits. It lowers fossil fuel consumption which reduces emissions translating to improved air quality. Research has shown that a CO2 emission reduction of between 10-15% can be achieved deploying AI-optimized traffic flow infrastructure. This would result in significant fuel savings and a reduction in public health costs associated with air pollution [

72]. AI-ontrolled traffic management system can also improve safety outcomes on the road.

Despite the advantages of deploying AI for traffic management, it also comes with various ethical and technical concerns. Because of the quantity of data required, one of the major ethical issues is related to data privacy. Another threat is cybersecurity; a cyber-attack can compromise and disrupt the system. Furthermore, AI may prioritize the optimization of certain neighborhoods over others leading to the question of justice and equity [

73]. In addressing these concerns, effective regulations and frameworks is essential. These framework and regulatory policies must prioritize accountability, security, data privacy, data protection, and safety.

5. Challenges of AI Implementation in the Road Transport System

As AI continues to transform and revolutionise the transportation industry, stakeholders have yet to harmonise and optimise the activities in the transportation ecosystem due to diverse challenges that are technical and non-technical [

74]. For example, data availability and computational power are major challenges when deploying AI models in the transportation industry [

44]. There are also social and security concerns about AI deployment in the transportation industry. Likewise, human factors, infrastructure and environmental issues are contained in the web of challenges which are limiting AI deployment in the transportation industry.

Table 2 presents a summary of AI challenges in road transport. The next sections discussed the impacts of the factors mentioned above on AI implementation in the transportation industry.

5.1. Technical Challenges

Data quality and availability are at the front burners of the technical challenges that have limited AI implementation in the transportation industry [

75]. Machine learning models' performance depends on the quantity of data used to develop models [

76]. In terms of road transport, large data about traffic and accident patterns as well as road conditions matter when developing an AI model for road users [

77]. Further, information about vehicle speed and weather conditions is required to develop robust AI models for community use [

49]. Unfortunately, most communities lack the infrastructure to reliably collect and store information about the features mentioned above. On the one hand, unreliable data affect the predictive power of an AI model thereby undermining the AI system’s efficiency. On the other hand, processing reliable data for real-time applications requires infrastructure with high computational power.

Infrastructure is required for designing dynamic traffic systems that will process incoming data for identifying patterns within a split-second. Currently, several communities lack a budget for infrastructure that can make traffic decisions within a split-second [

78]. In short, the existing traffic infrastructure in several communities is obsolete and those cannot collect and store large amounts of data to support AI technology implementation in their transportation industry. Attempts to upgrade such infrastructure are not only expensive, but it is also incompatible with modern traffic management software. This challenge is intricate in communities where multiple agencies are responsible for transport management because multi-system upgrading will be required.

5.2. Safety and Security Challenges

Safety is at the heart of every transport system because any system failure has severe implications that might lead to loss of life [

79]. Hence, stakeholders are sceptical about transferring certainty transport management activities to AI systems because misinterpreting information about their transport attributes will lead to unpredictable consequences, such as accidents and injuries. For example, an AI system can fail to perform satisfactorily in areas with poor lighting and this might lead to poor pedestrian detection – the consequence might be accidents. Apart from system malfunction, AI systems are prone to cyber-attacks. The consequences of cyber attacks, security threats, are enormous in transport systems because of the interconnectivity that exists in these systems.

Gridlocks and accidents are some of the consequences of cyber attacks on a transport system once the system is hacked [

80]. Designing a robust AI system for the transport system is a formidable challenge because hackers are continually devising techniques to perpetuate their evil acts in the transportation industry. Hence, there is a need for stringent regulations that will support AI implementations in transportation to prevent the implementation of non-robust AI systems in the transportation industry. Unfortunately, several communities are yet to draft laws and policies that will make it difficult for robust AI systems implementation in the transport industry. For example, there are limited policies on penalties for failed AI systems usage that lead to accidents [

81]. This ethical concern has made several stakeholders jettison AI implementation in the transport industry. They are waiting for directions on who is responsible for a failed AI system: the manufacturer, the driver, or the AI developer.

5.3. Human Factors Challenges

Trust is a major issue in AI systems’ implementations in the transport industry [

82]. For example, people are apprehensive and sceptical about assigning their responsibility to AI technologies – this issue has led to a poor proliferation of autonomous vehicles, especially in communities with high road transport accident records. When autonomous vehicles fail in such communities, it will not only affect public trust in autonomous vehicles but will also affect their implementations for other transport management systems in the environment.

Investigations on AI failures have been tracked to unpredictable human behaviours [

83]. This unpredictableness has limited AI implementation in transport systems. Jaywalking and sudden lane changes are among the unpredictableness of drivers' behaviours. The nexus between drivers, pedestrians and other road conditions has not been perfected. Autonomous vehicle manufacturers need to design mechanisms that will adequately address this problem to improve drivers’ experience and expectations.

The myth that AI will displace people from jobs is also affecting its implementation in the transport system. Drivers, traffic controllers and maintenance workers are among the people that AI implementation will affect in the transport sector [

84]. These workers are among the people discouraging AI implementation in this sector. Rather than opposing AI implementations, technocrats opined that their concern should be about retraining and upskilling to catch up with innovations in the AI tech space. Upskilled workers will be required to take up the new job opportunities generated by AI implementation. Retraining and upskilling costs in AI are capital intensive; investment in retraining and upskilling is a major challenge for stakeholders in the transport sector.

5.4. Infrastructure Challenges

Apart from investment in the transport sector workforce, investment in this sector’s infrastructure is a major challenge. A community needs to invest in data centres to optimise AI implementation in its transport sector [

85]. Furthermore, investment is required for communication networks, sensors and cameras for AI implementation to be successful in a transport system. This infrastructure is required for data collection for AI systems to provide real-time information in the transport ecosystem. Therefore, a community with inadequate infrastructure might need to upgrade their system or build infrastructure that will enable AI implementation; the cost of upgrading, or building, a system is capital-intensive.

When upgrading a transport system, experts are often faced with interoperability challenges because they might need to connect traffic systems and other road safety technologies [

86]. This task is challenging because the technologies are owned and operated by different stakeholders. For example, the government are often in charge of traffic management systems, while individuals control and manage vehicle fleets. Experts will have to find a common ground for these stakeholders to come together to design a smart transport system for a community – this activity is complex, cumbersome and challenging because of conflicting stakeholders’ interests.

5.5. Environmental Challenges

AI infrastructure consumes energy to collect and process data for real-time information generation [

85]. For example, equipment, such as sensors and processors, in autonomous vehicles consume energy continuously when collecting and analysing information from their environments. Likewise, smart traffic management systems depend on data centres for their operations – data centres are energy-consuming centres. Therefore, AI infrastructure competes with other energy centres in a community. This competition increases a community's energy storage in a community where energy generation is a major challenge.

This problem also creates energy inequality because AI systems are most likely to be deployed in communities where wealthier people live. Communities where wealthier people dominate are therefore likely to have improved traffic management systems compared to communities where poor people live. This imbalance creates a societal problem. Hence, equitable accessibility of AI technologies, in respective of socio-economic status, is a chanllenge, especially in developing countries.

6. Conclusions

This study presented the AI and carbon emission nexus concerning road transportation. The nexus was considered because of global concern about greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions from the transportation sector. It was observed that stakeholders are aiming for a 60% reduction by 2050 compared to 1990 levels. In the transportation sector, road transport contribution accounts for about 48% of global CO2 emissions. Attempts at addressing this problem have led to the proliferation of Electric vehicles (EVs) in developed countries, such as United Kingdom and the US. EVs can reduce CO2 emissions to an acceptable level. Scholars’ reports showed that EVs, which are privately owned, have not contributed more to CO2 reduction because public transportation modes contribute more to carbon emissions than private modes. Furthermore, this study observed that rail transportation is generally more environmentally friendly than road transportation.

The literature showed that different strategies have been documented for carbon emissions reduction in the transportation sector. Vehicle fleet policies, fuel consumption optimization, traffic control systems, and speed management were among the frequently used strategies in this sector. Also, this study observed that AI is emerging as a promising tool for carbon emission management in the transport sector. It offers several benefits for the sector. For example, it provides real-time information about low implementation costs and reduces human bias in traffic control and emission monitoring. Other benefits of AI in this sector include tracking problems and route scheduling optimization. In addition, it was observed that the global market for AI in the transportation sector is growing because of its capacity to analyse historical data.

Artificial Neural Networks (ANN), Support Vector Machines (SVM), and Long Short-Term Memory Neural Networks are among the AI algorithms in the transport system. These algorithms use historical data to predict CO2 emissions from the transport sector based on different features. Road conditions, fuel consumption, and traffic patterns were among the features used to predict CO2 emissions. Furthermore, it was observed that there is traffic and CO2 emissions. Apart from CO2 emissions management, AI technologies have helped to optimise traffic prediction and management.

This study observed that the implementation of AI in transportation faces technical challenges. Data quality, availability, and high-performance infrastructure are among the challenges affecting AI implementation in the transportation industry. In terms of safety and security concerns, it observed that system failures and vulnerability to cyber-attacks are hindering AI adoption in transportation systems. Furthermore, lack of trust in AI technologies and fear of job displacement contribute to human challenges in AI implementation. This study observed that low investment in data centres and communication networks are among the major infrastructure challenges affecting AI adoption in transportation systems. Lastly, high energy consumption affects AI adoption in this system.

References

- D. Burchart-Korol and P. Folęga, ‘Impact of Road Transport Means on Climate Change and Human Health in Poland’, PROMET - TrafficTransportation, vol. 31, no. 2, pp. 195–204, Apr. 2019, .

- V. H. S. De Abreu, M. G. Da Costa, V. X. Da Costa, T. F. De Assis, A. S. Santos, and M. de A. D’Agosto, ‘The role of the circular economy in road transport to mitigate climate change and reduce resource depletion’, Sustainability, vol. 14, no. 14, p. 8951, 2022.

- A. Schaefer, H. D. Jacoby, J. B. Heywood, and I. A. Waitz, ‘The Other Climate Threat: Transportation: A global travel surge is inevitable, but runaway growth of mobility-related CO 2 emissions is not’, Am. Sci., vol. 97, no. 6, pp. 476–483, 2009.

- P. Hughes, Personal transport and the greenhouse effect. Routledge, 2013. Accessed: Jun. 09, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.taylorfrancis.com/books/mono/10.4324/9781315066448/personal-transport-greenhouse-effect-peter-hughes.

- K. J. Shah et al., ‘Green transportation for sustainability: Review of current barriers, strategies, and innovative technologies’, J. Clean. Prod., vol. 326, p. 129392, 2021.

- E. Uherek et al., ‘Transport impacts on atmosphere and climate: Land transport’, Atmos. Environ., vol. 44, no. 37, pp. 4772–4816, 2010.

- D. Howey, R. North, and R. Martinez-Botas, ‘Road transport technology and climate change mitigation’, Grantham Inst. Clim. Change Imp. Coll. Lond., vol. 10, 2010, Accessed: Jun. 15, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.imperial.ac.uk/media/imperial-college/grantham-institute/public/publications/briefing-papers/Road-transport-technology-and-climate-mitigation---Grantham-BP-2.pdf.

- Y. Van Fan, S. Perry, J. J. Klemeš, and C. T. Lee, ‘A review on air emissions assessment: Transportation’, J. Clean. Prod., vol. 194, pp. 673–684, 2018.

- S. Aminzadegan, M. Shahriari, F. Mehranfar, and B. Abramović, ‘Factors affecting the emission of pollutants in different types of transportation: A literature review’, Energy Rep., vol. 8, pp. 2508–2529, 2022.

- O. Velychko and T. Gordiyenko, ‘Methodologies of Evaluation of the Greenhouse Gases Emission from Diesel Transport’, in Proc. of Intern. 17th Symp. IMEKO TC, 2010, pp. 8–10. Accessed: Jun. 09, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.imeko.org/publications/tc19-2010/IMEKO-TC19-2010-001.pdf.

- S. Singh et al., ‘Hydrogen: A sustainable fuel for future of the transport sector’, Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev., vol. 51, pp. 623–633, 2015.

- Ian Tiseo, ‘Annual carbon dioxide (CO₂) emissions worldwide from 1940 to 2023’. Accessed: Jun. 10, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.statista.com/statistics/276629/global-co2-emissions/.

- L. Winkler, D. Pearce, J. Nelson, and O. Babacan, ‘The effect of sustainable mobility transition policies on cumulative urban transport emissions and energy demand’, Nat. Commun., vol. 14, no. 1, p. 2357, 2023.

- M. Kabir et al., ‘Climate change due to increasing concentration of carbon dioxide and its impacts on environment in 21st century; a mini review’, J. King Saud Univ.-Sci., vol. 35, no. 5, p. 102693, 2023.

- L. J. Nunes, ‘The rising threat of atmospheric CO2: a review on the causes, impacts, and mitigation strategies’, Environments, vol. 10, no. 4, p. 66, 2023.

- R. D. P. Astuti and A. U. Rauf, ‘Outdoor air pollution due to transportation, landfill, and incinerator’, in Health and Environmental Effects of Ambient Air Pollution, Elsevier, 2024, pp. 257–302. Accessed: Jun. 09, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780443160882000065.

- J. K. Stanley, D. A. Hensher, and C. Loader, ‘Road transport and climate change: Stepping off the greenhouse gas’, Transp. Res. Part Policy Pract., vol. 45, no. 10, pp. 1020–1030, Dec. 2011, . [CrossRef]

- Hannah Ritchie, Pablo Rosado, and Max Roser, ‘Breakdown of carbon dioxide, methane and nitrous oxide emissions by sector’. Accessed: Jun. 10, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://ourworldindata.org/emissions-by-sector.

- R. Robinson et al., ‘Travelling through a warming world: climate change and migratory species’, Endanger. Species Res., vol. 7, pp. 87–99, Jun. 2009, . [CrossRef]

- Ian Tiseo, ‘Distribution of carbon dioxide emissions produced by the transportation sector worldwide in 2022, by sub sector’. Accessed: Jun. 10, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1185535/transport-carbon-dioxide-emissions-breakdown/.

- E. A. Etukudoh, A. Hamdan, V. I. Ilojianya, C. D. Daudu, and A. Fabuyide, ‘Electric vehicle charging infrastructure: a comparative review in Canada, USA, and Africa’, Eng. Sci. Technol. J., vol. 5, no. 1, pp. 245–258, 2024.

- S. P. Sathiyan et al., ‘Comprehensive assessment of electric vehicle development, deployment, and policy initiatives to reduce GHG emissions: opportunities and challenges’, IEEE Access, vol. 10, pp. 53614–53639, 2022.

- Mathilde Carlier, ‘Global electric vehicle revenue forecast 2016-2028’.

- E. Suryani, R. A. Hendrawan, P. F. E. Adipraja, B. Widodo, U. E. Rahmawati, and S.-Y. Chou, ‘Dynamic scenario to mitigate carbon emissions of transportation system: A system thinking approach’, Procedia Comput. Sci., vol. 197, pp. 635–641, 2022.

- J. Montoya-Torres, O. Akizu-Gardoki, and M. Iturrondobeitia, ‘Measuring life-cycle carbon emissions of private transportation in urban and rural settings’, Sustain. Cities Soc., vol. 96, p. 104658, 2023.

- T. Peng, X. Yang, Z. Xu, and Y. Liang, ‘Constructing an environmental friendly low-carbon-emission intelligent transportation system based on big data and machine learning methods’, Sustainability, vol. 12, no. 19, p. 8118, 2020.

- V. Dimoula, F. Kehagia, and A. Tsakalidis, ‘A Holistic Approach for Estimating Carbon Emissions of Road and Rail Transport Systems’, Aerosol Air Qual. Res., vol. 16, no. 1, pp. 61–68, 2016, . [CrossRef]

- C. Zuo, M. Birkin, G. Clarke, F. McEvoy, and A. Bloodworth, ‘Reducing carbon emissions related to the transportation of aggregates: Is road or rail the solution?’, Transp. Res. Part Policy Pract., vol. 117, pp. 26–38, 2018.

- H. W. Kopfer, J. Schönberger, and H. Kopfer, ‘Reducing greenhouse gas emissions of a heterogeneous vehicle fleet’, Flex. Serv. Manuf. J., vol. 26, no. 1–2, pp. 221–248, Jun. 2014, . [CrossRef]

- M. Ehsani, A. Ahmadi, and D. Fadai, ‘Modeling of vehicle fuel consumption and carbon dioxide emission in road transport’, Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev., vol. 53, pp. 1638–1648, 2016.

- S. Zhang et al., ‘Real-world fuel consumption and CO2 (carbon dioxide) emissions by driving conditions for light-duty passenger vehicles in China’, Energy, vol. 69, pp. 247–257, 2014.

- S. Lin, B. De Schutter, Y. Xi, and H. Hellendoorn, ‘Integrated urban traffic control for the reduction of travel delays and emissions’, IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst., vol. 14, no. 4, pp. 1609–1619, 2013.

- M. Madireddy et al., ‘Assessment of the impact of speed limit reduction and traffic signal coordination on vehicle emissions using an integrated approach’, Transp. Res. Part Transp. Environ., vol. 16, no. 7, pp. 504–508, 2011.

- L. Chen and H. Yang, ‘Managing congestion and emissions in road networks with tolls and rebates’, Transp. Res. Part B Methodol., vol. 46, no. 8, pp. 933–948, 2012.

- H. Xie, L. Tu, J. Fang, and S. M. Easa, ‘Proactive highway traffic control with intelligent multi-objective optimisation algorithm’, Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng. - Transp., vol. 175, no. 2, pp. 65–75, Apr. 2022, . [CrossRef]

- J. Garcia-Nieto, J. Ferrer, and E. Alba, ‘Optimising traffic lights with metaheuristics: Reduction of car emissions and consumption’, in 2014 International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN), IEEE, 2014, pp. 48–54. Accessed: Jul. 02, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/abstract/document/6889749/.

- C. Osorio and K. Nanduri, ‘Urban transportation emissions mitigation: Coupling high-resolution vehicular emissions and traffic models for traffic signal optimization’, Transp. Res. Part B Methodol., vol. 81, pp. 520–538, 2015.

- D. Abudayyeh, A. Nicholson, and D. Ngoduy, ‘Traffic signal optimisation in disrupted networks, to improve resilience and sustainability’, Travel Behav. Soc., vol. 22, pp. 117–128, 2021.

- W. K. A. U. K. Fernando, R. M. Samarakkody, and M. N. Halgamuge, ‘Smart Transportation Tracking Systems Based on the Internet of Things Vision’, in Connected Vehicles in the Internet of Things, Z. Mahmood, Ed., Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2020, pp. 143–166. [CrossRef]

- S. Liu, S. Huang, X. Xu, J. Lloret, and K. Muhammad, ‘Efficient visual tracking based on fuzzy inference for intelligent transportation systems’, IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst., vol. 24, no. 12, pp. 15795–15806, 2023.

- M. Hajiaghaei-Keshteli, S. Molla-Alizadeh-Zavardehi, and R. Tavakkoli-Moghaddam, ‘Addressing a nonlinear fixed-charge transportation problem using a spanning tree-based genetic algorithm’, Comput. Ind. Eng., vol. 59, no. 2, pp. 259–271, 2010.

- İ. Karaoğlan and S. E. Kesen, ‘The coordinated production and transportation scheduling problem with a time-sensitive product: a branch-and-cut algorithm’, Int. J. Prod. Res., vol. 55, no. 2, pp. 536–557, Jan. 2017, . [CrossRef]

- D. E. Ighravwe and S. A. Oke, ‘A Workforce and Truck Allocation Model in a Solid Waste Management System: A Case from Nigeria’, Appl. Environ. Res., vol. 43, no. 3, pp. 60–78, 2021.

- L. S. Iyer, ‘AI enabled applications towards intelligent transportation’, Transp. Eng., vol. 5, p. 100083, 2021.

- O. Ghaffarpasand, A. M. Jahromi, R. Maleki, E. Karbassiyazdi, and R. Blake, ‘Intelligent geo-sensing for moving toward smart, resilient, low emission, and less carbon transport’, in Artificial Intelligence and Data Science in Environmental Sensing, Elsevier, 2022, pp. 39–55. Accessed: Jun. 30, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780323905084000113.

- R. H. Kim and H.-G. Min, ‘ARCTO: AIoT System for Reducing Carbon Emissions Using Traffic Optimization’, in 2022 18th IEEE/ASME International Conference on Mechatronic and Embedded Systems and Applications (MESA), IEEE, 2022, pp. 1–6. Accessed: Jun. 30, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/abstract/document/10004459/.

- Artur Haponik, ‘AI, big data, and machine learning in transportation’. Accessed: Oct. 16, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://addepto.com/blog/ai-big-data-and-machine-learning-in-transportation/.

- G. A. M. Meiring and H. C. Myburgh, ‘A review of intelligent driving style analysis systems and related artificial intelligence algorithms’, Sensors, vol. 15, no. 12, pp. 30653–30682, 2015.

- R. Abduljabbar, H. Dia, S. Liyanage, and S. A. Bagloee, ‘Applications of artificial intelligence in transport: An overview’, Sustainability, vol. 11, no. 1, p. 189, 2019.

- E. Ranyal, A. Sadhu, and K. Jain, ‘Road condition monitoring using smart sensing and artificial intelligence: A review’, Sensors, vol. 22, no. 8, p. 3044, 2022.

- K. Meduri, G. S. Nadella, H. Gonaygunta, and S. S. Meduri, ‘Developing a Fog Computing-based AI Framework for Real-time Traffic Management and Optimization’, Int. J. Sustain. Dev. Comput. Sci., vol. 5, no. 4, pp. 1–24, 2023.

- H. Lipson and M. Kurman, Driverless: intelligent cars and the road ahead. Mit Press, 2017. Accessed: Oct. 16, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=2rpNEAAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PR7&dq=+AI+algorithms+make+it+easier+to+connsume+more+fuel+by+suggesting+the+best+route+that+vechicles+should+use+in+order+to+optimise+time+and+energy+%E2%80%93+this+benefit+improves+ridership+expectations&ots=m1C22VeNYF&sig=dPEeC15bjCNCK9-RsYmq-5kyijo.

- O. Vermesan et al., ‘Automotive intelligence embedded in electric connected autonomous and shared vehicles technology for sustainable green mobility’, Front. Future Transp., vol. 2, p. 688482, 2021.

- M. K. Nasir, R. Md Noor, M. A. Kalam, and B. M. Masum, ‘Reduction of Fuel Consumption and Exhaust Pollutant Using Intelligent Transport Systems’, Sci. World J., vol. 2014, pp. 1–13, 2014, . [CrossRef]

- S. Aoki, C.-W. Lin, and R. Rajkumar, ‘Human-robot cooperation for autonomous vehicles and human drivers: Challenges and solutions’, IEEE Commun. Mag., vol. 59, no. 8, pp. 35–41, 2021.

- H. Nagar, R. Machavaram, P. Kulkarni, and P. Soni, ‘AI-based engine performance prediction cum advisory system to maximise fuel efficiency and field performance of the tractor for optimum tillage’, Syst. Sci. Control Eng., vol. 12, no. 1, p. 2347936, Dec. 2024, . [CrossRef]

- M. Ghalkhani and S. Habibi, ‘Review of the Li-ion battery, thermal management, and AI-based battery management system for EV application’, Energies, vol. 16, no. 1, p. 185, 2022.

- A. M. Nassef, A. G. Olabi, H. Rezk, and M. A. Abdelkareem, ‘Application of artificial intelligence to predict CO2 emissions: critical step towards sustainable environment’, Sustainability, vol. 15, no. 9, p. 7648, 2023.

- Y. Zhou, A. Ravey, and M.-C. Péra, ‘A survey on driving prediction techniques for predictive energy management of plug-in hybrid electric vehicles’, J. Power Sources, vol. 412, pp. 480–495, 2019.

- M. Zhu, X. Wang, and Y. Wang, ‘Human-like autonomous car-following model with deep reinforcement learning’, Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol., vol. 97, pp. 348–368, 2018.

- Y. Yin, H. Wang, and X. Deng, ‘Real-time logistics transport emission monitoring-Integrating artificial intelligence and internet of things’, Transp. Res. Part Transp. Environ., vol. 136, p. 104426, 2024.

- N. Uriarte-Gallastegi, G. Arana-Landín, B. Landeta-Manzano, and I. Laskurain-Iturbe, ‘The Role of AI in Improving Environmental Sustainability: A Focus on Energy Management’, Energies, vol. 17, no. 3, p. 649, 2024.

- K. Kumar, M. Parida, and V. K. Katiyar, ‘Short term traffic flow prediction for a non urban highway using artificial neural network’, Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci., vol. 104, pp. 755–764, 2013.

- M. S. Dougherty and M. R. Cobbett, ‘Short-term inter-urban traffic forecasts using neural networks’, Int. J. Forecast., vol. 13, no. 1, pp. 21–31, 1997.

- E. I. Vlahogianni, ‘Optimization of traffic forecasting: Intelligent surrogate modeling’, Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol., vol. 55, pp. 14–23, 2015.

- M. Castro-Neto, Y.-S. Jeong, M.-K. Jeong, and L. D. Han, ‘Online-SVR for short-term traffic flow prediction under typical and atypical traffic conditions’, Expert Syst. Appl., vol. 36, no. 3, pp. 6164–6173, 2009.

- I. O. Olayode, L. K. Tartibu, M. O. Okwu, and U. F. Ukaegbu, ‘Development of a hybrid artificial neural network-particle swarm optimization model for the modelling of traffic flow of vehicles at signalized road intersections’, Appl. Sci., vol. 11, no. 18, p. 8387, 2021.

- X. Ma, Z. Tao, Y. Wang, H. Yu, and Y. Wang, ‘Long short-term memory neural network for traffic speed prediction using remote microwave sensor data’, Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol., vol. 54, pp. 187–197, 2015.

- E. I. Vlahogianni, M. G. Karlaftis, and J. C. Golias, ‘Optimized and meta-optimized neural networks for short-term traffic flow prediction: A genetic approach’, Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol., vol. 13, no. 3, pp. 211–234, 2005.

- C. Goves, R. North, R. Johnston, and G. Fletcher, ‘Short term traffic prediction on the UK motorway network using neural networks’, Transp. Res. Procedia, vol. 13, pp. 184–195, 2016.

- O. Ghaffarpasand, A. M. Jahromi, R. Maleki, E. Karbassiyazdi, and R. Blake, ‘Intelligent geo-sensing for moving toward smart, resilient, low emission, and less carbon transport’, in Artificial Intelligence and Data Science in Environmental Sensing, Elsevier, 2022, pp. 39–55. Accessed: Nov. 08, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780323905084000113.

- C. Osorio and K. Nanduri, ‘Urban transportation emissions mitigation: Coupling high-resolution vehicular emissions and traffic models for traffic signal optimization.’, Transp. Res. Part B Methodol., vol. 81, pp. 520–538.

- Y. K. Dwivedi et al., ‘Artificial Intelligence (AI): Multidisciplinary perspectives on emerging challenges, opportunities, and agenda for research, practice and policy.’, Int. J. Inf. Manag., vol. 57, p. 101994, 2021.

- O. Vermesan and J. Bacquet, Cognitive Hyperconnected Digital Transformation: Internet of Things Intelligence Evolution. River Publishers, 2017. Accessed: Oct. 16, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=nPIxDwAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PP1&dq=+As+AI+continues+to+transform+and+revolutionise+the+transportation+industry,+stakeholders+have+yet+to+harmonise+and+optimise+the+activities+in+the+transportation+ecosystem+due+to+diverse+challenges+that+are+technical+and+non-technical&ots=Kxx44paJLI&sig=V-siK3wJReq2HrGOPjJUfONDDYc.

- I. Daniyan, K. Mpofu, R. Muvunzi, and I. D. Uchegbu, ‘Implementation of Artificial intelligence for maintenance operation in the rail industry’, Procedia CIRP, vol. 109, pp. 449–453, 2022.

- M. I. Jordan and T. M. Mitchell, ‘Machine learning: Trends, perspectives, and prospects’, Science, vol. 349, no. 6245, pp. 255–260, Jul. 2015, . [CrossRef]

- S. Olugbade, S. Ojo, A. L. Imoize, J. Isabona, and M. O. Alaba, ‘A review of artificial intelligence and machine learning for incident detectors in road transport systems’, Math. Comput. Appl., vol. 27, no. 5, p. 77, 2022.

- Y. Mandali, ‘Applications of microsimulation traffic data in infrastructure construction projects using 3D/4D CAD models’, 2013, Accessed: Oct. 16, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://repositories.lib.utexas.edu/items/069a5f0c-1cf9-4a18-ab21-ff11d4fd3fa9.

- R. Amalberti, ‘The paradoxes of almost totally safe transportation systems’, in Human error in aviation, Routledge, 2017, pp. 101–118. Accessed: Oct. 16, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.taylorfrancis.com/chapters/edit/10.4324/9781315092898-7/paradoxes-almost-totally-safe-transportation-systems-amalberti.

- S. Vivek, D. Yanni, P. J. Yunker, and J. L. Silverberg, ‘Cyberphysical risks of hacked internet-connected vehicles’, Phys. Rev. E, vol. 100, no. 1, p. 012316, Jul. 2019, . [CrossRef]

- M. U. Scherer, ‘Regulating artificial intelligence systems: Risks, challenges, competencies, and strategies’, Harv JL Tech, vol. 29, p. 353, 2015.

- A. V. S. Madhav and A. K. Tyagi, ‘Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI): Connecting Artificial Decision-Making and Human Trust in Autonomous Vehicles’, in Proceedings of Third International Conference on Computing, Communications, and Cyber-Security, vol. 421, P. K. Singh, S. T. Wierzchoń, S. Tanwar, J. J. P. C. Rodrigues, and M. Ganzha, Eds., in Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems, vol. 421. , Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore, 2023, pp. 123–136. [CrossRef]

- Y. K. Dwivedi et al., ‘Artificial Intelligence (AI): Multidisciplinary perspectives on emerging challenges, opportunities, and agenda for research, practice and policy’, Int. J. Inf. Manag., vol. 57, p. 101994, 2021.

- D. Lenior, W. Janssen, M. Neerincx, and K. Schreibers, ‘Human-factors engineering for smart transport: Decision support for car drivers and train traffic controllers’, Appl. Ergon., vol. 37, no. 4, pp. 479–490, 2006.

- S. S. Gill et al., ‘AI for next generation computing: Emerging trends and future directions’, Internet Things, vol. 19, p. 100514, 2022.

- S. Djahel, R. Doolan, G.-M. Muntean, and J. Murphy, ‘A communications-oriented perspective on traffic management systems for smart cities: Challenges and innovative approaches’, IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor., vol. 17, no. 1, pp. 125–151, 2014.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).