1. Introduction

Preclinical studies have shown that ultra-high dose rate (UHDR) irradiation can significantly reduce radiation damage to normal tissues without compromising tumor control, a phenomenon known as the FLASH effect. The FLASH effect has been confirmed in various types of ionizing radiation, different species, and experimental systems [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6]. However, the mechanism of the FLASH effect remains unclear. Ionizing radiation-induced nuclear DNA damage included base damage, single-strand breaks (SSBs), double-strand breaks (DSBs), DNA cross-links, and clustered damage, which were the key cause of cell death and the important topic in radiobiology. However, it is still unclear whether UHDR irradiation can reduce nuclear DNA damage. Therefore, studying different types of DNA damage after UHDR is of great significance for a deeper understanding of the mechanism of the FLASH effect.

The impact of UHDR irradiation on nuclear DNA damage remains controversial. Some studies have found that genomic DNA damage (53BP1 foci) after UHDR irradiation is as much as that after conventional dose rate irradiation (CONV) [

7], while Favaudon et al.'s study [

8] suggests that UHDR can reduce DNA damage (53BP1 foci, γH2AX foci) in normal human lung cells. For cell experiments, the effect of FLASH on the DNA damage can be influenced by factors such as cell type, the kind of damage marker, observation time, and experiment method. Additionally, existing experiments indicate that a dose threshold was required to observe the FLASH effect [

9]. At relatively large doses, commonly used markers for characterizing DNA damage in cell level, such as foci and micronuclei formation, are prone to dose saturation effects. As a result, it was difficult to accurately measure the extent of DNA damage in irradiated cells. Moreover, it is also challenging to measure different types of DNA damage, such as base damage and SSBs. Therefore, choosing an appropriate biological system and measurement method is crucial for in-depth quantitative research on DNA damage under FLASH conditions.

This study will use plasmids as a classic simplified biological system for research. Plasmids had the advantages of being easy to manipulate and having a well-defined structure. Using an electron FLASH beam, we will quantitatively study the types and extent of DNA damage at UHDR and explore the impact of plasmid concentration on DNA damage, providing important evidence for clarifying the mechanism of DNA damage at UHDR.

2. Results

2.1. Comparison of SSBs Between CONV-RT and FLASH-RT

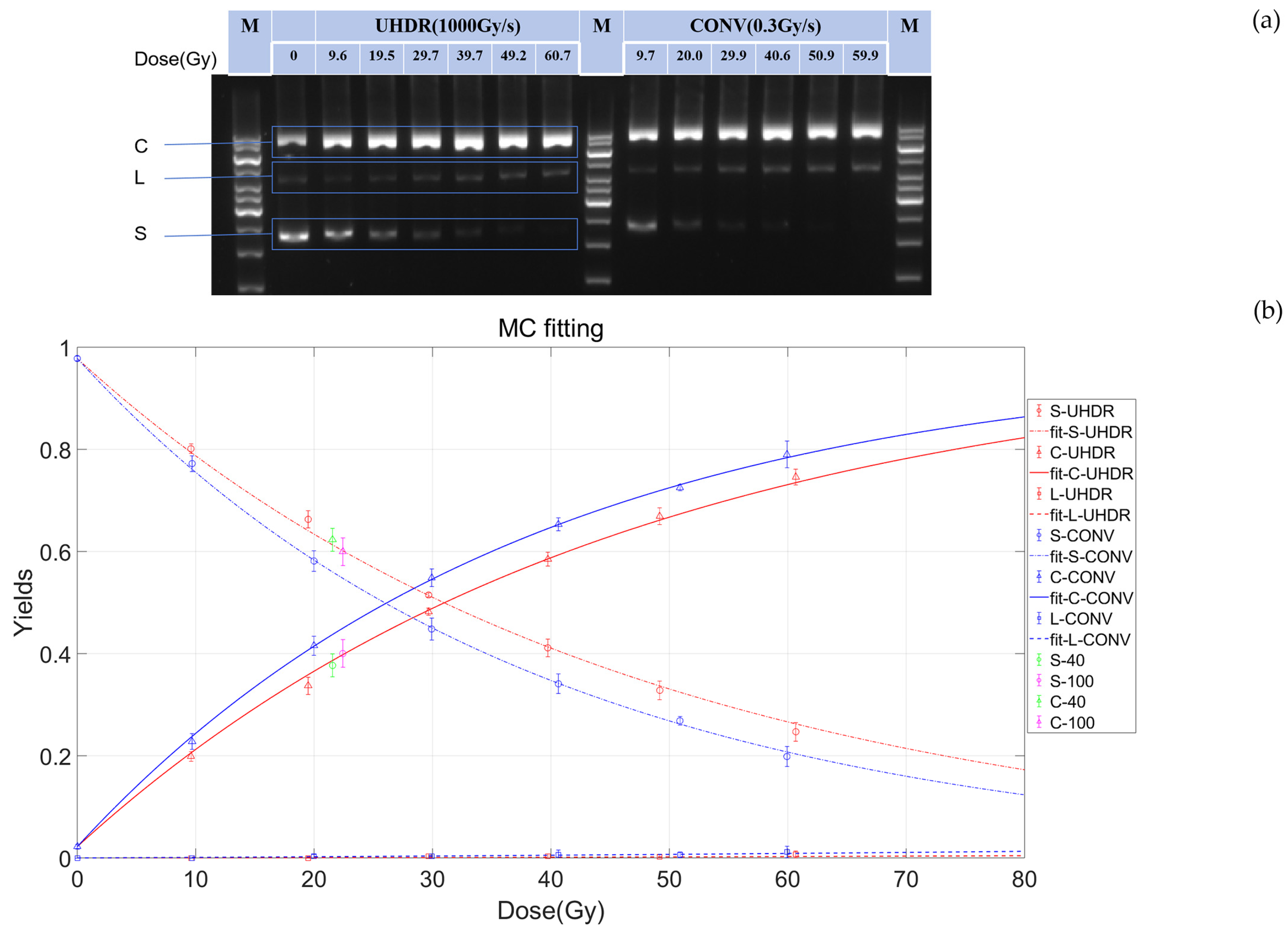

To systematically investigate the differences in DNA damage induced under FLASH and CONV conditions, we conducted gradient experiments with a dose range of 0–60 Gy using pBR322 plasmids as the subject. Standard plasmid DNA has three basic conformations: supercoiled (S), linear (L), and open circular (C). Since plasmids in different conformations have distinct electrophoretic mobility, bands can be observed at different positions after electrophoresis. Therefore, gel electrophoresis can be used to separate different subtypes of pBR322 plasmids and observe the changes in plasmid structure with irradiation dose. As shown in

Figure 1a, after irradiation, the plasmids exhibited supercoiled (S), linear (L), and open circular (C) structures. Compared with the bands of non-irradiated plasmids, the intensity of the open circular structure band increased after irradiation, indicating a higher content of SSBs in the irradiated plasmids. With increasing dose, the content of supercoiled structure gradually decreased, while the open circular structure correspondingly increased with dose, and the content of linear structure remained almost unchanged (

Figure 1). At the same dose, the intensity of the supercoiled structure band under UHDR was higher than that under CONV (

Figure 1a), indicating that UHDR irradiation reduced plasmid breakage.

To further quantify these observations, image analysis software and mathematical models was exploited to analyze the effects of UHDR and CONV irradiation on DNA subtypes quantitatively. First, we used ImageJ software to quantify the gel imaging results, and then employed Equations 4–6 to obtain the functions of relative yields of DNA subtypes with radiation dose (

Figure 1b). The yield of DSBs was very low, which was less than 2% of that of SSBs (

Figure 1b). In addition, the induction rate of SSBs induced by irradiation (expressed in units of SSB/Gy/molecule) for UHDR and CONV were 21.7±0.4×10⁻

3 SSB/Gy/molecule and 25.8±0.3×10⁻

3 SSB/Gy/molecule, respectively, which were similar to the values obtained using Equations 7–10. Calculated by Equations 7–10, the SSBs induction rate for UHDR was 22.1, significantly lower than that for CONV (25.9) (

Table 1). This indicates that UHDR can significantly reduce the induction of SSBs.

2.2. The Differences in Base Damage Under FLASH and CONV Conditions

Base damage is considered as another major type of DNA damage induced by radiation. At the present study, Fpg enzyme and Nth enzyme, which can recognize and excise damaged purine bases and pyrimidine bases respectively, were utilized to convert DNA base damage into SSBs.

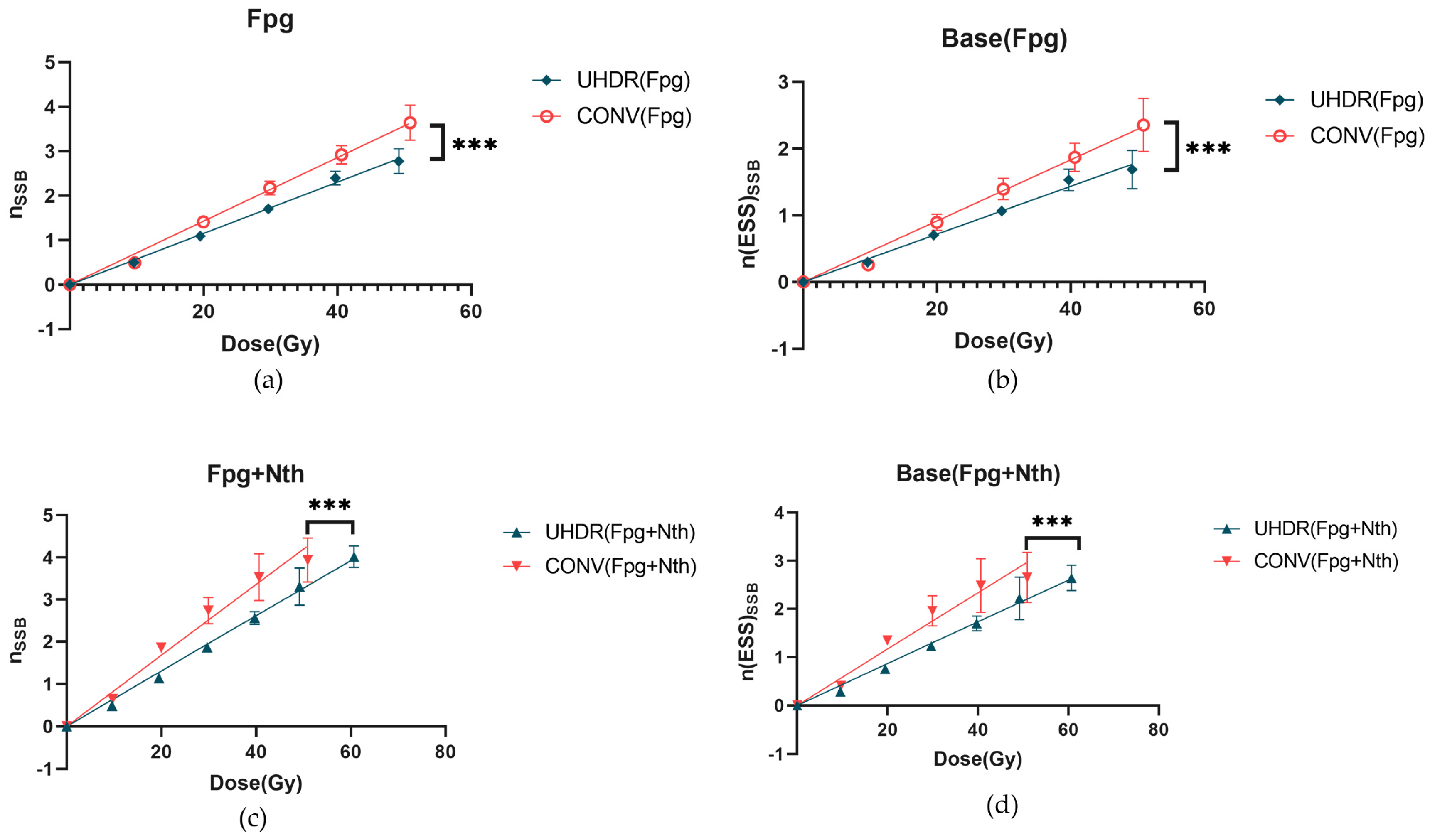

Using Equations 7-10, the induction rates of SSBs induced by irradiation under different conditions were calculated. As shown in

Figure 2a, after treatment with Fpg enzyme, the induction rate of SSBs induced by UHDR irradiation was 57.7±1.7×10⁻

3 SSB/Gy/molecule, significantly lower than that of CONV irradiation, which was 71.4±2.5×10⁻

3 SSB/Gy/molecule. With increasing irradiation dose, the difference in the yield of SSBs per plasmid (

) between the UHDR and CONV groups gradually increased. Further analysis using Equations 7-11 revealed that the induction rate of Fpg-sensitive sites by UHDR irradiation was 35.9±1.8×10⁻

3 SSB/Gy/molecule, also significantly lower than that of CONV irradiation, which was 45.8±2.5×10⁻

3 SSB/Gy/molecule, (

Figure 2b). As the dose increased, the difference in the net yield of enzyme-sensitive sites per plasmid (

) between the UHDR and CONV groups also became more pronounced. These results once again confirmed that UHDR irradiation can significantly reduce not only SSBs but also base damage.

When samples were treated with both Fpg and Nth enzymes, the induction rate of SSBs induced by UHDR irradiation was 65.4±1.2×10⁻

3 SSB/Gy/molecule, significantly lower than that of CONV irradiation, which was 84.0±4.6×10⁻

3 SSB/Gy/molecule (

Figure 2c). Additionally, the calculated induction rate of base damage was 43.3±1.9×10⁻

3 SSB/Gy/molecule for UHDR irradiation, also significantly lower than that of CONV irradiation, which was 58.4±4.5×10⁻

3 SSB/Gy/molecule (

Figure 2d). The induction rate of DSBs induced by irradiation after enzyme treatment are listed in

Table 1, the difference between enzyme-treated and untreated samples represented cluster damage. However, its proportion was too low, and it is associated with high-frequency high errors. Therefore, further investigation was not conducted in this study. These data further indicated that UHDR irradiation had a significant effect in reducing both SSBs and base damage.

2.3. The Effect of Plasmid Concentration on Radiation-Induced SSBs and Base Damage

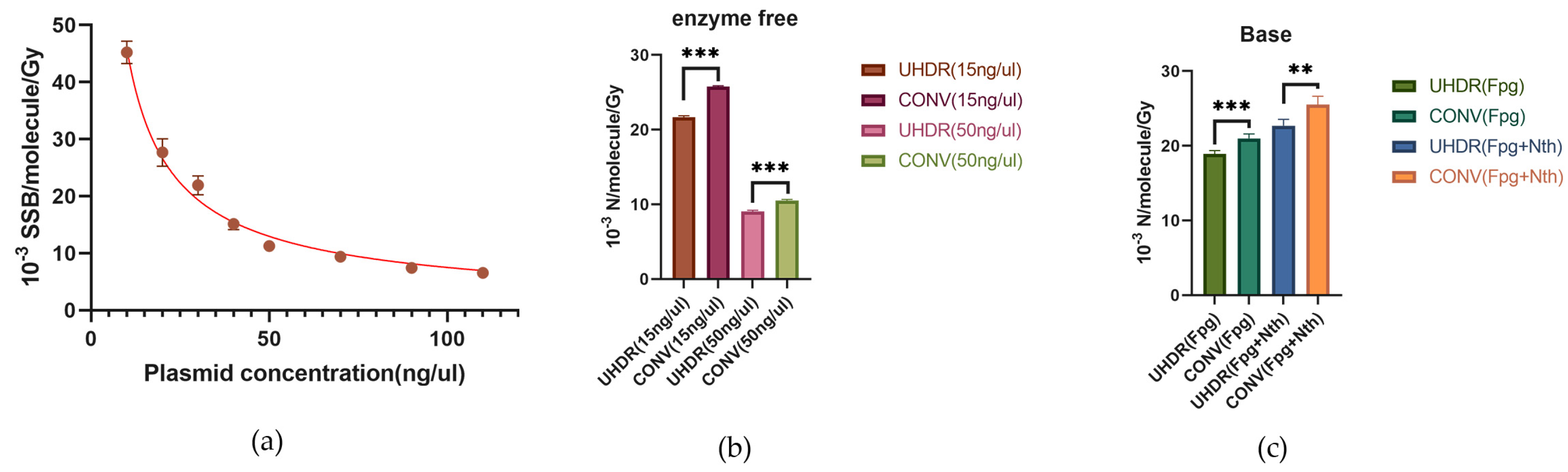

As can be seen from

Table 1, there were differences in the absolute values of SSBs among different studies. It suggested that plasmid concentration may also play an important role in affecting the induction of SSBs and base damage by irradiation. Therefore, we investigated the influence of concentration on the induction rates of radiation-induced SSBs and base damage. As shown in

Figure 3a, the induction rate of SSBs gradually decreased with increasing plasmid concentration. In our previous experiments, we used a plasmid concentration of 15 ng/µL. For comparison, in this experiment, we used a plasmid concentration of 50 ng/µL. The results showed that compared with the 15 ng/µL concentration, the induction rate of radiation-induced SSBs was lower in the high-concentration samples (50 ng/µL) (

Figure 3b). Consistently, the induction rate of SSBs in high-concentration plasmids in UHDR group was still significantly lower than that in CONV group, with a 14% reduction in SSB induction. Additionally, after treatment with Fpg enzyme or Fpg+Nth enzymes, the induction rate of damage at Fpg-sensitive sites in UHDR group was 18.9±0.9×10⁻

3 SSB/Gy/molecule, significantly lower than that in CONV group (21.0±1.2×10⁻

3 SSB/Gy/molecule). Moreover, the induction rate of damage at Fpg+Nth enzyme-sensitive sites in UHDR group were also significantly lower than that in CONV group (22.7±1.7×10⁻

3 SSB/Gy/molecule

versus 25.5±2.2×10⁻

3 SSB/Gy/molecule) (

Figure 3c). The induction rate of SSBs induced by irradiation after enzyme treatment are listed in

Table 1. These results indicate that although plasmid concentration affects the overall level of SSBs and base damage, it does not change the conclusion that UHDR irradiation can reduce the induction of SSBs and base damage.

3. Discussion

UHDR irradiation is believed to significantly reduce radiation damage to normal tissues, but the mechanisms underlying the sparing effect remain unclear. Although several hypotheses, such as the DNA integrity hypothesis, radical recombination hypothesis, and immune hypothesis, have been proposed to explain the sparing effect [

14,

15], the impact of UHDR on DNA damage is still a matter of debate [

7,

8,

16,

17]. In this study, we used plasmid DNA to investigate the effects of UHDR irradiation on different types of DNA damage. We found that compared to CONV irradiation, UHDR irradiation significantly reduced SSBs and preserved more polymeric structures. These findings are consistent with conclusions from other studies involving protons, electron beams, and high-energy electron beams [

2,

10,

12,

13,

16,

17]. Despite that a significant difference in the induction rates of DSBs, the content of linear structures is very low and thus a significant difference in linear structure content between UHDR and CONV irradiation can only be observed at high doses (60 Gy). Only a few studies have observed that UHDR irradiation can reduce DSBs [

13].

To further investigate radiation-induced base damage, we employed enzymatic treatments. Two enzymes were primarily used in this study: Fpg enzyme and Nth enzyme. Both are bifunctional enzymes with N-glycosylase and AP lyase activities [

18,

19]. However, they differ in their specific functions: Fpg enzyme mainly recognizes and excises damaged purine bases, such as 8-oxoG and FapyG [

18], while Nth enzyme targets damaged pyrimidine bases, including thymine glycol, 5,6-dihydroxythymine, 5-hydroxy-5-methylhydantoin, and uracil glycol [

19]. Although only one study has used Fpg enzyme [

12], no FLASH relevant studies have been conducted using Nth enzyme. Our results showed that compared to untreated samples, treatment with one enzyme increased the yield of SSBs because base damage can be converted into SSBs. Treatment with both enzymes produced more SSBs than treatment with Fpg enzyme alone due to the different cleavage sites of the two enzymes. Compared to CONV irradiation, UHDR irradiation produced fewer SSBs under the same dose conditions, regardless of whether one or both enzymes were used. Moreover, by subtracting the untreated group from the enzyme-treated groups, we observed that UHDR irradiation induced significantly fewer base damages under the same dose conditions.

In summary, compared to CONV irradiation, UHDR irradiation can reduce SSBs, base damage, and DSBs, especially a significant reduction in SSBs and base damage. This may be because low-LET radiation (such as X-rays and electron beams) primarily induces DNA damage through free radical-mediated indirect effects. One hypothesis suggested that UHDR irradiation instantaneously generated high concentrations of peroxyl radicals, increasing the probability of peroxyl radical recombination and thereby reducing damage induced by peroxyl radicals [

20]. Experiments have shown that different dose rate irradiations produce similar amounts of H· and OH· radicals in aqueous solutions, but the content of lipid peroxides is reduced in UHDR group [

21]. The more compelling experimental evidence was that increasing the concentration of Tris solution reduced the induction rates of radiation-induced SSBs for both kinds of dose rates [

10]. When eliminating radicals, the damage produced by the two kinds of dose rates was the similar at the same dose [

11]. Therefore, free radicals recombination played an important role in reducing DNA damage under UHDR conditions.

Furthermore, we compared the effects of plasmid damage among different published studies [

2,

10,

12,

13]. We found that there were certain differences in the absolute values of radiation-induced SSB induction rates among different groups (

Table 1). Although differences in radiation types and fitting methods contributed to these variations, our study revealed that plasmid concentration during irradiation had a more significant impact. After increasing the plasmid concentration to 50 ng/µL, the radiation-induced SSB induction rate we obtained was lower and closer to that reported by Konishi et al. [

12]. Although the concentration ranges studied differ, the findings of Kong et al. also support this conclusion [

22]. At present study, to ensure accurate measurement of irradiation doses using EBT3 and EBT XD films, we reduced the plasmid concentration (15 ng/µL), thereby significantly lowering the dose required to achieve the same level of damage as with the high plasmid concentration (50 ng/µL). Additionally, recognizing the important role of free radicals recombination in the FLASH sparing effect, we used PBS instead of Tris-EDTA buffer (TE buffer) to dilute the plasmids, reducing the Tris concentration in the plasmid solution to 0.3 mM. This lowered the radical scavenging rate of Tris, making the plasmid samples more susceptible to radical attack and increasing DNA damage at the same dose. Therefore, when comparing results from different research groups, factors such as plasmid concentration and Tris concentration in the plasmid solution should be taken into consideration.

All the results above indicate that the pBR322 plasmid model is useful for understanding the effects of UHDR on DNA damage. However, it should be noted that studying the quantity and types of DNA damage are only the initial steps in understanding the biological effects of UHDR. Further research is needed to investigate the subsequent impacts of UHDR, such as DNA repair, cell cycle, cell survival, and tissue damage.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Sample Preparation

The pBR322 plasmid DNA solution (4361 bp, 0.5 μg/μl in 1×TE) was purchased from Thermo Scientific. More than 90% of it was in supercoiled circular form (form 1) and there was no any linear form (form 3). Plasmid DNA solution was diluted in PBS buffer (1X, pH 7.4) to be 15 ng/μl or 50ng/ul and each DNA sample was prepared in 0.2 mL PCR tubes (PCR-02-C, Axygen) containing 50 μL of DNA solution for irradiation.

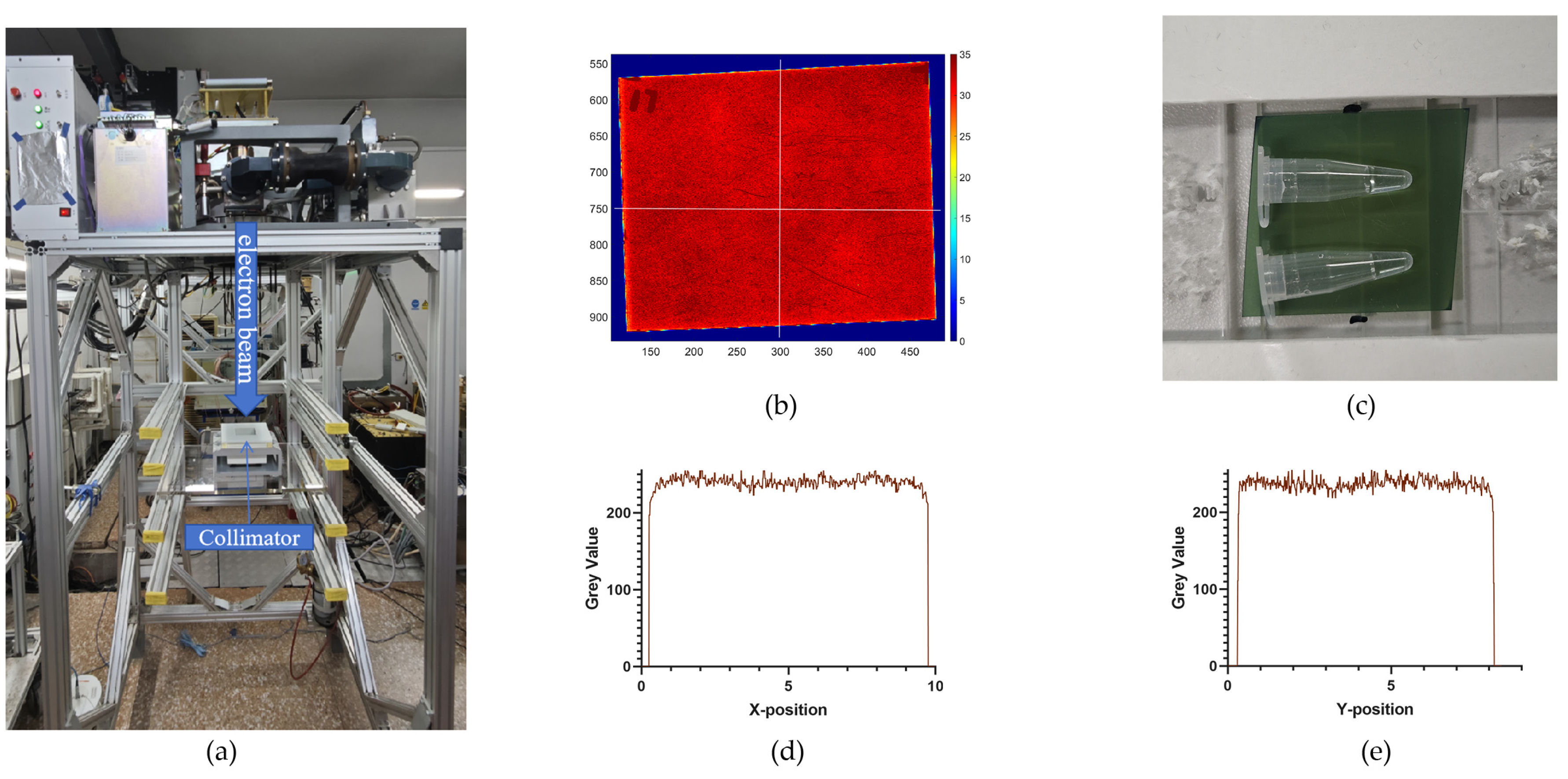

4.2. Irradiation

Irradiation experiments were performed at an electron linear accelerator, which provided a vertically irradiated electron beam with an energy of 6 MeV (

Figure 4), in the Department of Engineering Physics, Tsinghua University, Beijing, China. Irradiation altered the dose rate by changing the Source-to-Surface Distance (SSD), pulse width, and pulse frequency. The formula for calculating the pulse dose rate is as follows: Pulse Dose Rate = Single Pulse Dose×Pulse Frequency. Prior to irradiation, the single pulse dose was confirmed using EBT 3 and EBT XD films. During irradiation, the film was placed beneath the sample, and the dose was calculated by reading the film at 3 minutes after irradiation.

4.3. Enzyme Treatment

The Fpg enzyme working solution (from New England Biolabs) and Fpg+Nth enzyme working solution were prepared using Fpg enzyme, Nth enzyme, the NEBuffers (for Fpg and Nth), recombinant albumin and TE buffer (1X, pH 8.0) according to the protocol [

18]. For samples requiring enzyme treatment, withdraw 10 µl of plasmid sample (pBR322 DNA: 150 ng) and add 1 Unit of enzyme working solution, incubate at 37°C for 1 hour, then add 3 ul of EDTA solution (0.5M, pH 8.0) to terminate the reaction.

4.4. Agarose Gel Electrophoresis and Quantification of DNA Strand Breaks

10 µl of plasmid sample (pBR322 DNA: 150 ng) was mixed with 5 µl of TE buffer (1X, pH 8.0) to dilute to a concentration of 10 ng/µl. Take 5 µl of the diluted plasmid sample (pBR322 DNA: 50 ng) and add 1 µl of 6X TriTrack DNA loading buffer (Thermo Scientific), mix well, and then subject it to electrophoresis on a 1% agarose gel (pre-mixed with NA-Red) in Electrophoresis Buffer (1X Tris Acetate-EDTA buffer) at 130V and 23℃ for 1 hour. Under these electrophoresis conditions, SSBs that are less than six base pairs apart (one on each complementary strand) are detected as DSBs [

23]. Subsequently, a fluorescent gel image is recorded, exported in the original TIFF format, and analyzed using ImageJ.

Using image analysis software, the total fluorescence intensity corresponding to the three forms of plasmid DNA was determined, namely the three bands for supercoiled circular (no strand breaks, noted S), open circular (with SSB, noted C), and linear (with DSB, noted L).

To calculate the fraction of three forms, the following equations were used:

where

,

,

represented the peaks of Form 1-3 recorded in ImageJ respectively.

4.5. DNA Damage Modeling

Using a robust curve-fitting model by McMahon and Currell [

24], fractions of three forms were plotted as a function of irradiation dose (Gy), where

represented the fractions of supercoiled circular, open circular and linear structures respectively,

are the corresponding yields of supercoiled circular, open circular and linear structures in the control sample respectively,

is the dose,

and

represented the induction rate of SSBs and DSBs by radiation (N/molecule/Gy):

4.6. Base Damage Modeling

The yield of SSBs per plasmid (

) and DSBs (

) and net yield of enzyme-sensitive sites per plasmid (

) were calculated using the equations described by Povirk et al. [

25], respectively:

where

,

and

represented the induction rate of SSB, DSB and base damage by radiation (N/molecule/Gy), and were determined using linear regression in GraphPad Prism 8.

4.7. Statistics

At the present study, at least three independent replicates were carried out for every experiment. The results were presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD). To determine significant differences between groups, we employed the Student's t-test and the F-test. The Student's t-test was used to compare the means of two related groups. The F-test was used to compare the variances between two groups of data to verify the assumption of homogeneity of variances. Significant differences were determined by the p-value, with thresholds of p < 0.01 for extremely significant differences.

5. Conclusions

Given the important role of DNA damage in cell survival and proliferation, the radiation induced DNA damage closely affected tumor control and normal tissue complication. However, the effect of UHDR irradiation on the DNA damage was still unclear. In the present study, through qualitative and quantitative analysis, it was found that UHDR had significant effect on reducing SSBs compared to CONV. When treated with Fpg and Nth enzyme, the induction rates of base damage in UHDR group was also obviously lower than that in CONV group. In addition, we found that plasmid concentration also affected the degree of damage, with lower SSB induction at higher plasmid concentration for both FLASH and CONV. For high-concentration plasmids, the induction rates of SSBs of UHDR was still 14% lower than that of CONV, indicating that UHDR-induced damage reduction was independent of plasmid concentration. This study provided a better ex-planation for understanding the different types of DNA damage induced by UHDR, which was of great significance for further understanding the mechanism of FLASH effect.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Q.-B. Fu and Y.-C. Wang; methodology, Q.-B. Fu; software, Y.-C. Wang; validation, Y.-C. Wang, Y. Zhang and C.-Y. Huang; formal analysis, T.-C. Huang; investigation, Q.-B. Fu and Y.-C. Wang; resources, Q.-B. Fu; data curation, Y.-C. Wang; writing—original draft preparation, Y.-C. Wang; writing—review and editing, Q.-B. Fu and T.-C. Huang; funding acquisition, Q.-B. Fu. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Key R&D Program of China (No. 2022YFC2402300) and National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 12441518).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available within the article.

Acknowledgments

Thanks very much for Dr. Jiaqi Qiu, Mr. Jian Wang and Prof. Hao Zha for the kind support of the UHDR irradiation experiment at Tsinghua University.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Gaide, O.; Herrera, F.; Jeanneret Sozzi, W.; Gonçalves Jorge, P.; Kinj, R.; Bailat, C.; Duclos, F.; Bochud, F.; Germond, J.-F.; Gondré, M.; et al. Comparison of Ultra-High versus Conventional Dose Rate Radiotherapy in a Patient with Cutaneous Lymphoma. Radiother Oncol 2022, 174, 87–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohsawa, D.; Hiroyama, Y.; Kobayashi, A.; Kusumoto, T.; Kitamura, H.; Hojo, S.; Kodaira, S.; Konishi, T. DNA Strand Break sInduction of Aqueous Plasmid DNA Exposed to 30 MeV Protons at Ultra-High Dose Rate. J Radiat Res 2022, 63, 255–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, F.; Yang, Y.; Zhu, H.; Wang, J.; Xiao, D.; Zhou, Z.; Dai, T.; Zhang, Y.; Feng, G.; Li, J.; et al. First Demonstration of the FLASH Effect with Ultrahigh Dose Rate High-Energy X-Rays. Radiother Oncol 2022, 166, 44–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vozenin, M.-C.; De Fornel, P.; Petersson, K.; Favaudon, V.; Jaccard, M.; Germond, J.-F.; Petit, B.; Burki, M.; Ferrand, G.; Patin, D.; et al. The Advantage of FLASH Radiotherapy Confirmed in Mini-Pig and Cat-Cancer Patients. Clin Cancer Res 2019, 25, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Favaudon, V.; Caplier, L.; Monceau, V.; Pouzoulet, F.; Sayarath, M.; Fouillade, C.; Poupon, M.-F.; Brito, I.; Hupé, P.; Bourhis, J.; et al. Ultrahigh Dose-Rate FLASH Irradiation Increases the Differential Response between Normal and Tumor Tissue in Mice. Sci Transl Med 2014, 6, 245ra93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saade, G.; Bogaerts, E.; Chiavassa, S.; Blain, G.; Delpon, G.; Evin, M.; Ghannam, Y.; Haddad, F.; Haustermans, K.; Koumeir, C.; et al. Ultrahigh-Dose-Rate Proton Irradiation Elicits Reduced Toxicity in Zebrafish Embryos. Adv Radiat Oncol 2023, 8, 101124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, X.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, W.; Wang, J.; Xiao, D.; Ren, H.; Wang, T.; Gao, F.; Liu, Z.; Zhou, K.; et al. FLASH X-Ray Spares Intestinal Crypts from Pyroptosis Initiated by cGAS-STING Activation upon Radioimmunotherapy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2022, 119, e2208506119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fouillade, C.; Curras-Alonso, S.; Giuranno, L.; Quelennec, E.; Heinrich, S.; Bonnet-Boissinot, S.; Beddok, A.; Leboucher, S.; Karakurt, H.U.; Bohec, M.; et al. FLASH Irradiation Spares Lung Progenitor Cells and Limits the Incidence of Radio-Induced Senescence. Clin Cancer Res 2020, 26, 1497–1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Q.-B.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.-C.; Huang, T.-C.; Zhu, H.-Y.; Deng, X.-W. Systematic Analysis and Modeling of the FLASH Sparing Effect as a Function of Dose and Dose Rate. NUCL SCI TECH 2024, 35, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanstall, H.C.; Korysko, P.; Farabolini, W.; Corsini, R.; Bateman, J.J.; Rieker, V.; Hemming, A.; Henthorn, N.T.; Merchant, M.J.; Santina, E.; et al. VHEE FLASH Sparing Effect Measured at CLEAR, CERN with DNA Damage of pBR322 Plasmid as a Biological Endpoint. Sci Rep 2024, 14, 14803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, H.; Yuan, Q.-G.; Phyllis, Z.; et al. Ultra-high dose rate irradiation induced DNA strand break in plasmid DNA[J]. Chin J Radiol Med Prot,2023,43(03):161-167. [CrossRef]

- Konishi, T.; Kusumoto, T.; Hiroyama, Y.; Kobayashi, A.; Mamiya, T.; Kodaira, S. Induction of DNA Strand Breaks and Oxidative Base Damages in Plasmid DNA by Ultra-High Dose Rate Proton Irradiation. Int J Radiat Biol 2023, 99, 1405–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perstin, A.; Poirier, Y.; Sawant, A.; Tambasco, M. Quantifying the DNA-Damaging Effects of FLASH Irradiation With Plasmid DNA. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2022, 113, 437–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vozenin, M.-C.; Bourhis, J.; Durante, M. Towards Clinical Translation of FLASH Radiotherapy. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2022, 19, 791–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limoli, C.L.; Vozenin, M.-C. Reinventing Radiobiology in the Light of FLASH Radiotherapy. Annu Rev Cancer Biol 2023, 7, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perstin, A.; Poirier, Y.; Sawant, A.; Tambasco, M. Quantifying the DNA-Damaging Effects of FLASH Irradiation With Plasmid DNA. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2022, 113, 437–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souli, M.P.; Nikitaki, Z.; Puchalska, M.; Brabcová, K.P.; Spyratou, E.; Kote, P.; Efstathopoulos, E.P.; Hada, M.; Georgakilas, A.G.; Sihver, L. Clustered DNA Damage Patterns after Proton Therapy Beam Irradiation Using Plasmid DNA. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2022, 23, 15606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hatahet, Z.; Kow, Y.W.; Purmal, A.A.; Cunningham, R.P.; Wallace, S.S. New Substrates for Old Enzymes. 5-Hydroxy-2’-Deoxycytidine and 5-Hydroxy-2’-Deoxyuridine Are Substrates for Escherichia Coli Endonuclease III and Formamidopyrimidine DNA N-Glycosylase, While 5-Hydroxy-2’-Deoxyuridine Is a Substrate for Uracil DNA N-Glycosylase. J Biol Chem 1994, 269, 18814–18820. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Dizdaroglu, M.; Laval, J.; Boiteux, S. Substrate Specificity of the Escherichia Coli Endonuclease III: Excision of Thymine- and Cytosine-Derived Lesions in DNA Produced by Radiation-Generated Free Radicals. Biochemistry 1993, 32, 12105–12111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Labarbe, R.; Hotoiu, L.; Barbier, J.; Favaudon, V. A Physicochemical Model of Reaction Kinetics Supports Peroxyl Radical Recombination as the Main Determinant of the FLASH Effect. Radiother Oncol 2020, 153, 303–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Froidevaux, P.; Grilj, V.; Bailat, C.; Geyer, W.R.; Bochud, F.; Vozenin, M.-C. FLASH Irradiation Does Not Induce Lipid Peroxidation in Lipids Micelles and Liposomes. Radiation Physics and Chemistry 2023, 205, 110733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, F.-Q.; Wang, X.; Ni, M.-N.; Sui, L.; Yang, M.-J. Effect of Concentration of DNA and Dose Rate in DNA Damage Induced by γ Ray[J]. Nuclear Physics Review, 2007, 24(2): 103-107. [CrossRef]

- Hanai, R.; Yazu, M.; Hieda, K. On the Experimental Distinction between Ssbs and Dsbs in Circular DNA. Int J Radiat Biol 1998, 73, 475–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McMahon, S.J.; Currell, F.J. A Robust Curve-Fitting Procedure for the Analysis of Plasmid DNA Strand Break Data from Gel Electrophoresis. Radiat Res 2011, 175, 797–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Povirk, L.F.; Wübter, W.; Köhnlein, W.; Hutchinson, F. DNA Double-Strand Breaks and Alkali-Labile Bonds Produced by Bleomycin. Nucleic Acids Res 1977, 4, 3573–3580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).