1. Introduction

The rise in atmospheric concentrations of greenhouse gases, especially carbon dioxide (

), has become a critical environmental challenge, leading to the urgent need for effective mitigation strategies [

1]. Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS) technologies have gained significant attention as a promising approach to reduce

emissions from industrial and energy-related sources [

2,

3]. Estimates suggest that CCS technologies could contribute to 25–67% of

emissions reductions in heavy industries [

4]. The CCS process entails the capture of

from industrial emissions, its transport to an underground storage reservoir, and its injection into deep geological formations, where it is expected to remain securely stored within the pore spaces of the rock [

5]. However, the potential impact of CCS activities has raised concerns such as

leakage, induced fractures, and groundwater contamination (

Figure 1) [

4].

When

dissolves in groundwater, it forms carbonic acid, lowering the pH and altering hydrogeochemical processes, which could mobilize various ions and contaminants [

6]. This can contaminate groundwater, jeopardizing its suitability for essential uses such as drinking water, agriculture, and industrial applications [

7].

-based contaminants in groundwater can cause adverse health effects for water populations, including gastrointestinal diseases, neurological disorders, and reproductive problems [

8]. Additionally, the contaminated groundwater can impair crop growth and quality in agricultural applications, reducing food security and causing economic losses for farmers [

9]. Industrial processes that rely on clean water may also suffer, as contaminants can interfere with manufacturing processes, reduce product quality, and increase operational costs due to the need for additional water treatment measures [

10].

The potential risks of groundwater contamination from hazardous waste, nonhazardous industrial waste, municipal solid waste, and special waste have been recognized by several studies [

11,

12,

13,

14]. However, there is still a need for comprehensive field investigations and experimental analyses to assess the real-world impacts of CCS activities on groundwater quality. This is important for the CCS projects, where proximity to populated areas and groundwater resources increases the potential for environmental and public health concerns. In this context, the present study aims to evaluate the impact of CCS activities on groundwater quality near the Barnett Zero CCS project, an onshore

storage site in Wise County, North Texas. Despite the significance of this project, the potential impact on groundwater resources in the surrounding area has not yet been explored. This research aims to establish a baseline for groundwater quality parameters and monitor potential changes resulting from CCS operations by conducting a field study and experimental investigation. We collect groundwater samples from monitoring wells near the CCS site and control sites estimated to be unaffected by

storage activities due to the early stages of injections and distance. We then use laboratory analyses, including the analysis of major ions, heavy metals, and organic contaminants, to assess the potential impacts of the Barnett Zero CCS project on groundwater quality. We compare areas near the CCS site with control sites to isolate the specific effects of CCS activities, understand potential risks, and develop effective monitoring and mitigation strategies to protect groundwater resources. By addressing the critical issue of groundwater protection, this study will support the broader goal of mitigating greenhouse gas emissions while ensuring the preservation of essential groundwater resources for current and future generations.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 provides a detailed overview of the study area and the Barnett Zero CCS project.

Section 3 outlines the research methodology, including field sampling techniques, laboratory analytical methods, and data analysis approaches.

Section 4 presents the results and discussion, including the characterization of groundwater quality parameters and assessing potential impacts from CCS activities, highlighting possible risks and mitigation strategies for protecting groundwater resources in the context of CCS operations.

Section 5 examines the limitations of the study and proposes future research directions.

Section 6 discusses the broader implications of the findings and outlines future research needs. Section 7 concludes the study, summarizing the key findings and contributions and suggesting future research directions.

2. Study Area

The Barnett Zero project in Wise County, Texas, is a commercial CCS initiative by the BKV Corporation and EnLink Midstream [

15]. As shown in

Figure 2a, Wise County is located in north-central Texas. Due to the region’s favorable geological conditions for carbon storage, the county has been proposed for the CCS project. The target injection zone in Wise County is the Ellenburger Group formation, which is a porous and permeable carbonate reservoir suitable for

storage [

16]. As shown in

Figure 2b, the overlying Barnett Shale acts as a thick, low-permeability caprock, providing an effective seal to prevent upward migration of

.

The Barnett Zero project represents reducing

emissions associated with natural gas production in the Barnett Shale region. The project is forecast to achieve an average storage rate of up to 210,000 metric tons of

e annually over its lifetime [

19]. EnLink transports natural gas produced by BKV in the Barnett Shale to its natural gas processing plant in Bridgeport, Texas. At the Bridgeport plant, the

waste stream is captured and transported to a BKV facility. The captured

is then compressed at the BKV facility. Finally, the compressed

is sequestered via BKV’s nearby underground injection control well, which is a Class II commercial carbon sequestration well [

19,

20].

Figure 3 shows the gas processing plant,

pipeline route, and one

injection well. The Railroad Commission (RRC) of Texas granted a permit for injection into the Ellenburger Group formation, specifying a maximum allowable surface pressure of 4,500 pounds per square inch gauge (psig) for this project. The authorized injection well also has a permitted depth interval ranging from 9,350 to 10,250 feet within the Ellenburger Group formation [

21].

The initial

injection into the Barnett Zero facility commenced operations safely and on schedule in November 2023 [

20].

Figure 4 shows the monthly

injection volumes in thousand cubic feet (MCF) for the Barnett Zero facility during the late months of 2023 and the initial months of 2024 [

22]. The data shows a gradual increase in injection volumes throughout 2024, starting from 112,473 MCF in January and peaking at 327,261 MCF in August 2024. Notably, injection operations began in November 2023 with an initial volume of 29,150 MCF and subsequently increased to 130,049 MCF in December 2023. This progression highlights the ramp-up phase of injection activities as the facility moved toward full-scale operation. The injection zone is well below and isolated from any major aquifers in the area; however, faults and undetected fractures within the formation still pose some risk of

leakage into groundwater [

4]. These faults and fractures could potentially serve as pathways for the migration of

or other operational by-products and contaminants, highlighting the importance of ongoing monitoring and risk management strategies to ensure the safety and integrity of the storage site and to avoid groundwater contamination.

4. Results and Discussion

We collected groundwater samples from monitoring wells to establish baseline groundwater quality data. The locations of the wells are highlighted in

Figure 5a. In each well, we measured pH, temperature, conductivity, and DO to assess initial groundwater conditions, following protocols for sample collection, preservation, and handling to ensure accurate results (

Figure 5b).

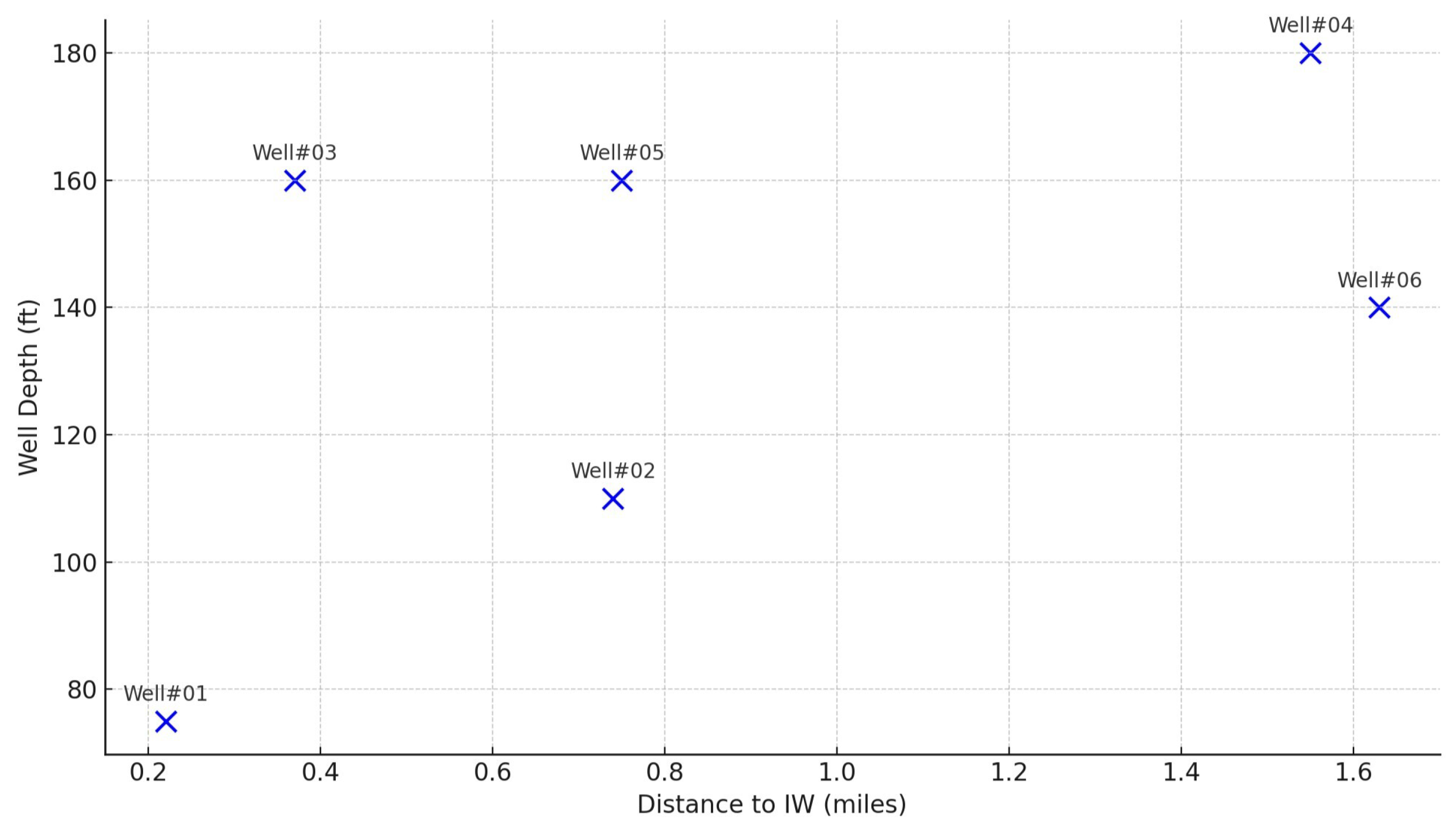

Figure 6 shows the relationship between well depth and the distance of each well from the injection well (IW). The monitoring wells (Well #1, Well #2, Well #3, and Well #5) are located within a one-mile radius of the Barnett Zero CCS injection well, while the control wells (Well #4 and Well #6) are located beyond a one-mile radius, unaffected by the CCS operations. Wells that are closer to the injection well do not follow a clear pattern of depth variation; for instance, Well#01, which is the closest to the IW, has a shallower depth compared to other wells such as Well#03 and Well#05, which are deeper. Control wells show greater depths than some of the monitoring wells. The monitoring and control wells have depths ranging from 75 ft to 180 ft, while the significantly deeper injection well reaches a depth of 9,350 ft, corresponding to the target geological formation (Ellenburger Group) for

storage.

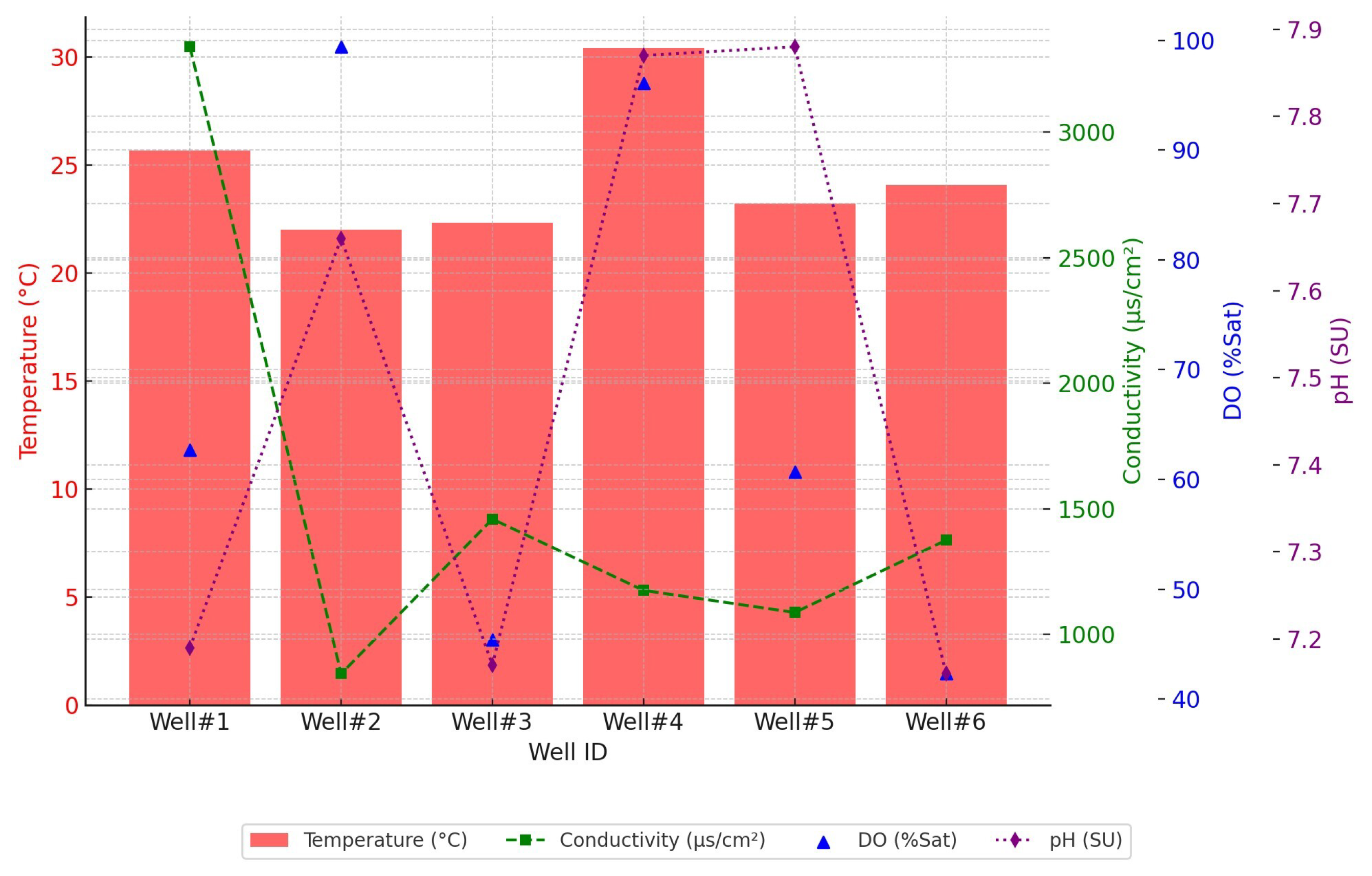

Figure 7 shows the pH, temperature, conductivity, and DO for each well. The pH values for the monitoring and control wells indicate that the groundwater is slightly alkaline, with pH values ranging from 7.16 to 7.88. The temperatures in these wells also vary more widely than initially stated, from

in Well #2 to 30.39°C in Well #4. This temperature variability might suggest localized thermal anomalies or differences in well depth, tank storage, and geological formation. Conductivity values range from 843 to

, with Well #1 displaying the highest conductivity, showing a higher ion concentration than the other wells. DO levels also show significant variation, with the highest saturation observed in Well #2 (99.4%) and the lowest in Well #6 (42.3%), indicating differences in oxidation-reduction conditions among the wells. Wells closer to the injection well do not show a consistent trend in DO levels, which may be influenced by factors such as local hydrogeology, well depth, and proximity to the CCS operations.

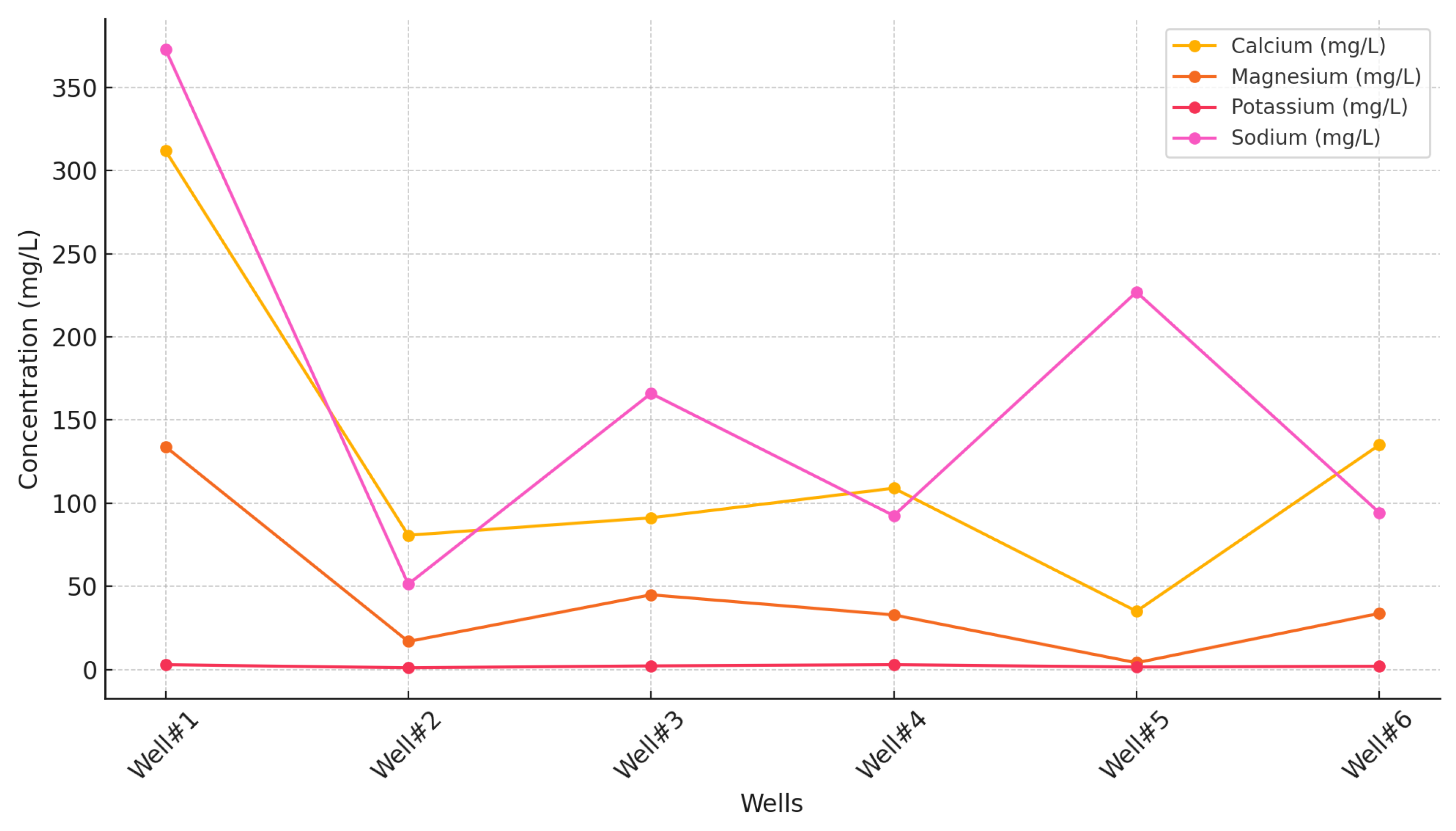

Figure 8 presents an analysis of major ions in groundwater samples. The results show variations in ion concentrations between monitoring wells located near the CCS site and control wells situated further away. Notably, calcium and sodium are the predominant cations detected, with concentrations in monitoring wells showing increases of up to 20% for calcium and 15% for sodium compared to control wells. Specifically, Well#1 showed the highest calcium concentration at 312 mg/L, while sodium levels reached 373 mg/L, indicating a potential influence of CCS activities on groundwater chemistry. Magnesium and potassium concentrations also varied across the wells, with monitoring wells generally exhibiting higher levels than control wells. For instance, Well#1 reported magnesium levels of 134 mg/L, significantly higher than the control well’s maximum of 33.7 mg/L. The presence of elevated ion concentrations in monitoring wells suggests that CO

2 interactions with groundwater may be mobilizing these ions, potentially altering the hydrogeochemical balance in the aquifer system. The observed increases in ion concentrations highlight the importance of ongoing monitoring to assess long-term trends and potential risks associated with CCS operations. Although these values are below harmful thresholds, continued research is essential to establish a more robust understanding of how CCS activities may impact groundwater chemistry over time.

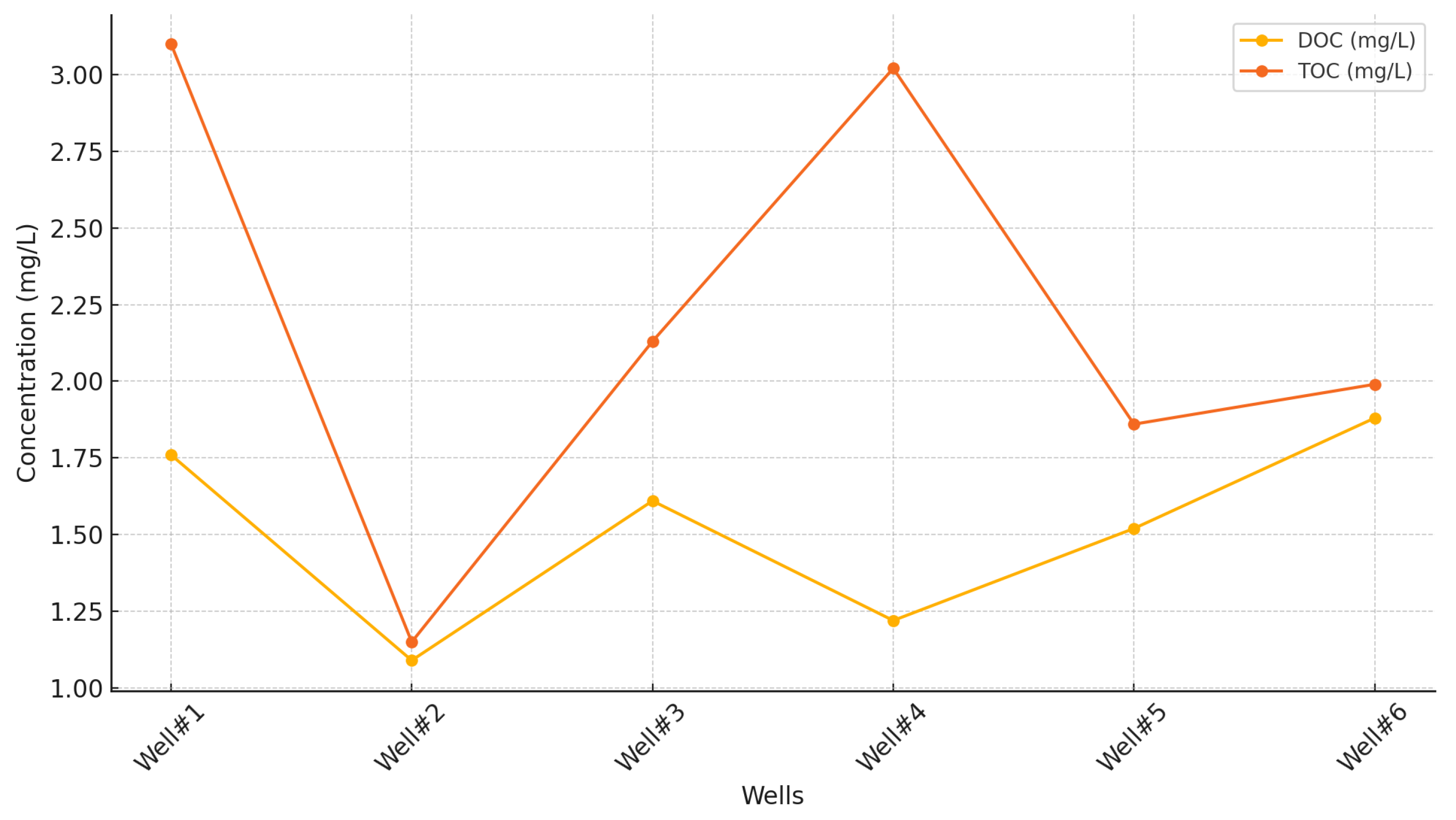

Figure 9 shows the notable variability in DOC and TOC levels across the six sampled wells. DOC levels ranged from 1.09 mg/L to 1.88 mg/L, with Well#6 recording the highest value at 1.88 mg/L and Well#2 the lowest at 1.09 mg/L. The average DOC across all wells was 1.51 mg/L. TOC concentrations exhibited a broader range, spanning from 1.15 mg/L to 3.10 mg/L. Well#1 showed the highest TOC at 3.10 mg/L, while Well#2 again recorded the lowest at 1.15 mg/L, with an overall average of 2.21 mg/L. These findings highlight heterogeneity in organic carbon content across the wells.

Monitoring wells and control wells displayed distinct characteristics in terms of organic carbon composition. Well#1, a monitoring well, exhibited the highest TOC (3.10 mg/L) but only moderate DOC (1.76 mg/L), suggesting the presence of particulate organic carbon. In contrast, Well#2, another monitoring well, consistently showed the lowest organic carbon content for both DOC (1.09 mg/L) and TOC (1.15 mg/L), indicating minimal organic matter contributions. These variations suggest that monitoring wells may reflect localized influences, possibly linked to CCS activities or natural geochemical processes. Control wells, on the other hand, presented contrasting patterns. Well#4 had the second-highest TOC (3.02 mg/L) but relatively low DOC (1.22 mg/L), pointing to the proportion of particulate organic matter. Conversely, Well#6 recorded the highest DOC (1.88 mg/L) but moderate TOC (1.99 mg/L), indicating a predominance of dissolved organic compounds. These findings suggest that control wells might be influenced by local geological features or external factors, such as land use practices, rather than direct CCS impacts.

The difference between TOC and DOC values across all wells ranged from 0.06 mg/L in Well#2 to 1.80 mg/L in Well#4, underscoring the variability in particulate organic carbon. However, no clear distinction emerged between monitoring and control wells regarding overall organic carbon patterns. This heterogeneity likely reflects a combination of natural geological variability and localized influences rather than a direct impact of CCS activities. The observed variability highlights the importance of continued monitoring to identify potential long-term trends or changes related to CCS operations. Further analysis over time will be essential to understand whether CCS activities contribute to shifts in organic carbon content or whether these differences are primarily driven by natural and anthropogenic factors in the region.

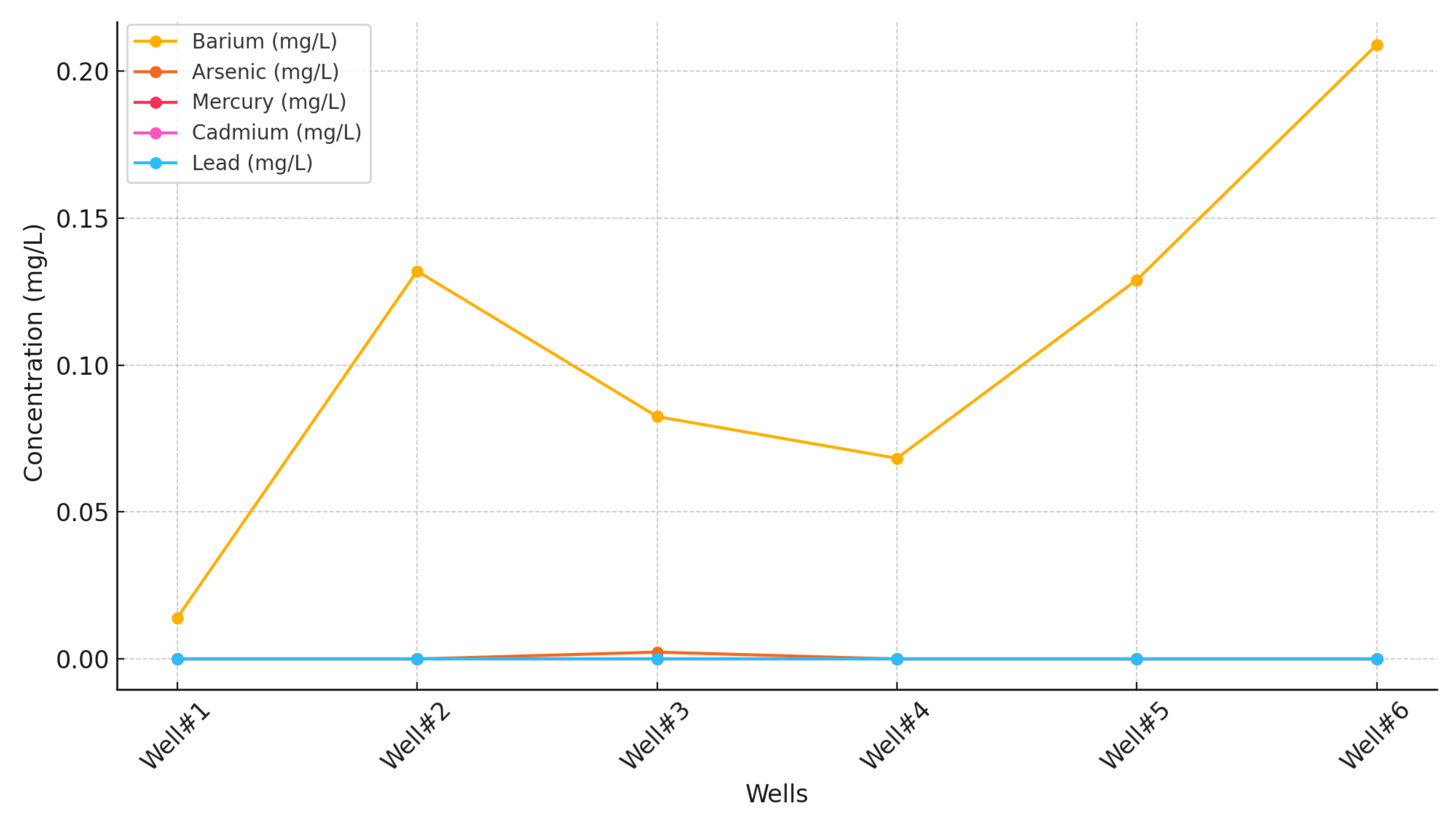

Figure 10 presents heavy metal concentrations across six wells. Barium (Ba) was the most prevalent heavy metal, detected in all wells at varying concentrations. Well #6 had the highest barium level (0.209 mg/L), while Well #1 had the lowest (0.0140 mg/L). The consistent presence of barium suggests its natural occurrence in local geological formations, with variations likely influenced by differences in aquifer characteristics or water sources. Arsenic (As) was detected only in Well #3 at 0.00236 mg/L, exceeding the method detection limit (MDL) of 0.0004 mg/L. The MDL represents the lowest concentration a laboratory can confidently detect and report with 99% certainty that the value is above zero [

34]. This isolated occurrence warrants further investigation to determine whether it results from natural geological variations or potential CCS activities. The absence of arsenic in other wells suggests its presence in Well #3 may be localized. Trace elements such as Ba and As can occur naturally in groundwater, particularly in aquifer systems where geochemical conditions cause the dissolution of these elements from rock and mineral formations, including sulfide ore deposits, igneous rocks, sandstone, and limestone [

35]. Mercury (Hg), cadmium (Cd), and lead (Pb) were not detected in any wells, with all measurements falling below their respective MDLs (0.00003 mg/L for mercury, 0.0002 mg/L for cadmium, and 0.0006 mg/L for lead). While these results are positive from a water quality perspective, ongoing monitoring remains essential for the early detection of potential future contamination.

The analysis of organic contaminants, including TPH and VOCs, did not reveal any detectable levels of contamination in the groundwater samples collected from the monitoring wells. TPH levels were consistently reported as non-detect, with all results below the MDL of 0.19 mg/L. This indicates the absence of hydrocarbons typically associated with oil and gas operations. Similarly, VOCs such as BTEX compounds (benzene, ethylbenzene, toluene, and xylene) were reported as non-detect, with all results below the MDL of 0.3 g/L. Although these VOCs are of particular concern due to their high mobility in groundwater and potential health risks, the absence of detectable concentrations suggests they are not currently impacting groundwater quality in the study area.

SVOCs were also analyzed, with a particular focus on phenol, to assess potential contamination. Anthracene, chrysene, naphthalene, and phenol—compounds often associated with industrial processes and known for their environmental persistence—were all reported as non-detect, with concentrations below their respective MDLs (0.014 g/L for anthracene, 0.021 g/L for chrysene, 0.02 g/L for naphthalene, and 0.035 g/L for phenol) across all monitoring and control wells. These findings indicate that these and other SVOC contaminants were not present in the groundwater during the sampling period. While SVOCs can pose long-term risks to groundwater quality because of their persistence, the lack of detectable levels suggests that the groundwater has not been impacted by nearby industrial activities or CCS operations. Continued monitoring will be crucial to ensure that ongoing CCS activities do not introduce hydrocarbons or other volatile and semi-volatile organic compounds into the groundwater system.

The findings represent the importance of ongoing groundwater quality assessment in CCS-affected regions. While no immediate contamination risks were identified, the observed variations in ion concentrations and organic carbon levels suggest potential geochemical interactions that merit further study. The elevated levels of certain ions in monitoring wells compared to control wells indicate possible mobilization of dissolved species, which could be influenced by injection and subsurface geochemical reactions. Additionally, the isolated occurrence of arsenic in Well #3, though not widespread, underscores the need for further investigation to determine whether it is a natural anomaly or a result of CCS-related processes. Hence, long-term monitoring will be essential to distinguish between natural hydrogeochemical processes and possible CCS-induced changes, ensuring the continued protection of groundwater resources.

6. Conclusions

The increasing concentration of atmospheric carbon dioxide () necessitates the development of Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS) technologies as a viable strategy to mitigate greenhouse gas emissions. However, concerns persist regarding the potential environmental risks associated with CCS, particularly its impact on groundwater quality. This study addressed these concerns by evaluating groundwater quality near the Barnett Zero CCS project in Wise County, Texas, and assessing the potential hydrogeochemical effects of injection. The results showed both immediate observations and implications for long-term environmental monitoring. While our analyses indicated increases in certain ion concentrations, specifically calcium and sodium, by up to 20% and 15%, respectively, in monitoring wells closer to the CCS site compared to control wells, these findings highlighted the necessity of regular monitoring in the vicinity of CCS operations. Total Organic Carbon (TOC) levels, which varied from 1.15 mg/L to 3.10 mg/L with the highest near the CCS operations, suggested ongoing geochemical interactions that could pose risks if not continuously assessed. Furthermore, the detection of arsenic in one monitoring well, albeit at low concentrations, underscored the potential for CCS activities to mobilize trace heavy metals. Importantly, the absence of significant levels of heavy metals and hydrocarbons provided initial reassurance about the safety of CCS as currently managed. However, the detection of barium across all wells and the specific presence of arsenic highlighted the complex nature of subsurface geochemistry once influenced by injected . These results advocated for the implementation of comprehensive risk management strategies, including robust baseline data collection, ongoing environmental monitoring, and adaptive management practices capable of responding to any signs of groundwater contamination.

This study confirmed that while CCS technologies hold considerable promise for reducing atmospheric emissions, their deployment must be managed carefully to mitigate any unintended consequences on groundwater resources. Continuous research and monitoring remain essential to ensure that CCS can be implemented safely and effectively as part of broader efforts to combat climate change. Future work should focus on extending the monitoring network, increasing the frequency of sampling, and enhancing analytical methods to capture more detailed data on potential contaminants. These efforts will be crucial in developing a more thorough understanding of the long-term impacts of CCS on groundwater systems and ensuring the environmental integrity of this important climate technology.

Figure 1.

Main potential risks associated with CCS activities including leakage, induced fractures, and groundwater contamination.

Figure 1.

Main potential risks associated with CCS activities including leakage, induced fractures, and groundwater contamination.

Figure 2.

(a) Wise County, located in north-central Texas; (b) Cross sections E-W and N-S Ellenburger Group formation. The Ellenburger Group formation serves as the target injection zone due to its porous and permeable carbonate reservoir properties, with the Barnett Shale acting as a low-permeability caprock to securely contain the stored

[

17,

18].

Figure 2.

(a) Wise County, located in north-central Texas; (b) Cross sections E-W and N-S Ellenburger Group formation. The Ellenburger Group formation serves as the target injection zone due to its porous and permeable carbonate reservoir properties, with the Barnett Shale acting as a low-permeability caprock to securely contain the stored

[

17,

18].

Figure 3.

Map showing the location of the injection well and gas processing plant involved in the Barnett Zero project in Wise County, Texas. This commercial CCS initiative by BKV Corporation and EnLink Midstream aims to reduce emissions from natural gas production in the Barnett Shale region. waste captured from EnLink’s Bridgeport plant is stored underground via one injection well.

Figure 3.

Map showing the location of the injection well and gas processing plant involved in the Barnett Zero project in Wise County, Texas. This commercial CCS initiative by BKV Corporation and EnLink Midstream aims to reduce emissions from natural gas production in the Barnett Shale region. waste captured from EnLink’s Bridgeport plant is stored underground via one injection well.

Figure 4.

Monthly injection volumes (in thousand cubic feet, MCF) for the Barnett Zero facility during late 2023 and early 2024. Injection operations commenced in November 2023, with a gradual increase in volumes observed through 2024 as the facility transitioned to full-scale operation.

Figure 4.

Monthly injection volumes (in thousand cubic feet, MCF) for the Barnett Zero facility during late 2023 and early 2024. Injection operations commenced in November 2023, with a gradual increase in volumes observed through 2024 as the facility transitioned to full-scale operation.

Figure 5.

(a) Locations of monitoring (blue markers) and control (green markers) wells for baseline groundwater quality assessment near the Barnett Zero CCS site; (b) Field parameters measured included pH, temperature, conductivity, and dissolved oxygen (DO) to evaluate initial groundwater conditions, following strict sample collection and handling protocols.

Figure 5.

(a) Locations of monitoring (blue markers) and control (green markers) wells for baseline groundwater quality assessment near the Barnett Zero CCS site; (b) Field parameters measured included pH, temperature, conductivity, and dissolved oxygen (DO) to evaluate initial groundwater conditions, following strict sample collection and handling protocols.

Figure 6.

Scatter plot showing the relationship between well depth (in feet) and the distance to the injection well (in miles). Each well is labeled with its corresponding Well ID.

Figure 6.

Scatter plot showing the relationship between well depth (in feet) and the distance to the injection well (in miles). Each well is labeled with its corresponding Well ID.

Figure 7.

Comparison of key water quality parameters (temperature, conductivity, dissolved oxygen, pH) across six wells (Well#1 to Well#6.

Figure 7.

Comparison of key water quality parameters (temperature, conductivity, dissolved oxygen, pH) across six wells (Well#1 to Well#6.

Figure 8.

Concentration of major ions across wells.

Figure 8.

Concentration of major ions across wells.

Figure 9.

Dissolved Organic Carbon (DOC) and Total Organic Carbon (TOC) levels across sampled wells.

Figure 9.

Dissolved Organic Carbon (DOC) and Total Organic Carbon (TOC) levels across sampled wells.

Figure 10.

Heavy metal concentrations across the wells.

Figure 10.

Heavy metal concentrations across the wells.

Table 1.

Summary of laboratory tests performed on groundwater samples to monitor potential impacts from leakage or CCS activities. The analyses are categorized into major ion concentrations, organic carbon levels, heavy metal presence, and organic contaminant detection. Each test helps to detect contamination, geochemical shifts, or evidence of migration.

Table 1.

Summary of laboratory tests performed on groundwater samples to monitor potential impacts from leakage or CCS activities. The analyses are categorized into major ion concentrations, organic carbon levels, heavy metal presence, and organic contaminant detection. Each test helps to detect contamination, geochemical shifts, or evidence of migration.

| Category |

Test Name |

Description |

| Major Ion Analyses |

Hardness, Total SM2340B-2011 |

Measures the total hardness of water, expressed as calcium carbonate (CaCO3). |

| |

Anions by SW9056A |

Analyzes various anions, such as chloride and sulfate, in the water sample. |

| |

Alkalinity by -2011 |

Assesses the ability of water to neutralize acids, indicating buffering capacity. |

| Organic Carbon Analyses |

Dissolved Organic Carbon by SW9060A |

Quantifies organic carbon present in dissolved form in the water sample. |

| |

Total Organic Carbon by E415.1 |

Measures total organic carbon in both dissolved and particulate forms. |

| Heavy Metal Analyses |

Mercury by SW7470A |

Detects mercury levels in the sample, important for assessing toxicity. |

| |

ICP-MS Metals by SW6020A |

Utilizes Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry to analyze trace metals. |

| Organic Contaminant Analyses |

Low-level Texas TPH by TX1005 |

Measures low concentrations of Total Petroleum Hydrocarbons (TPH) in water. |

| |

Low-Level Semivolatiles by 8270D |

Detects low levels of semivolatile organic compounds (SVOCs) in the sample. |

| |

Low-Level Volatiles by SW8260C |

Analyzes low levels of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) in the sample. |