Submitted:

24 January 2025

Posted:

27 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

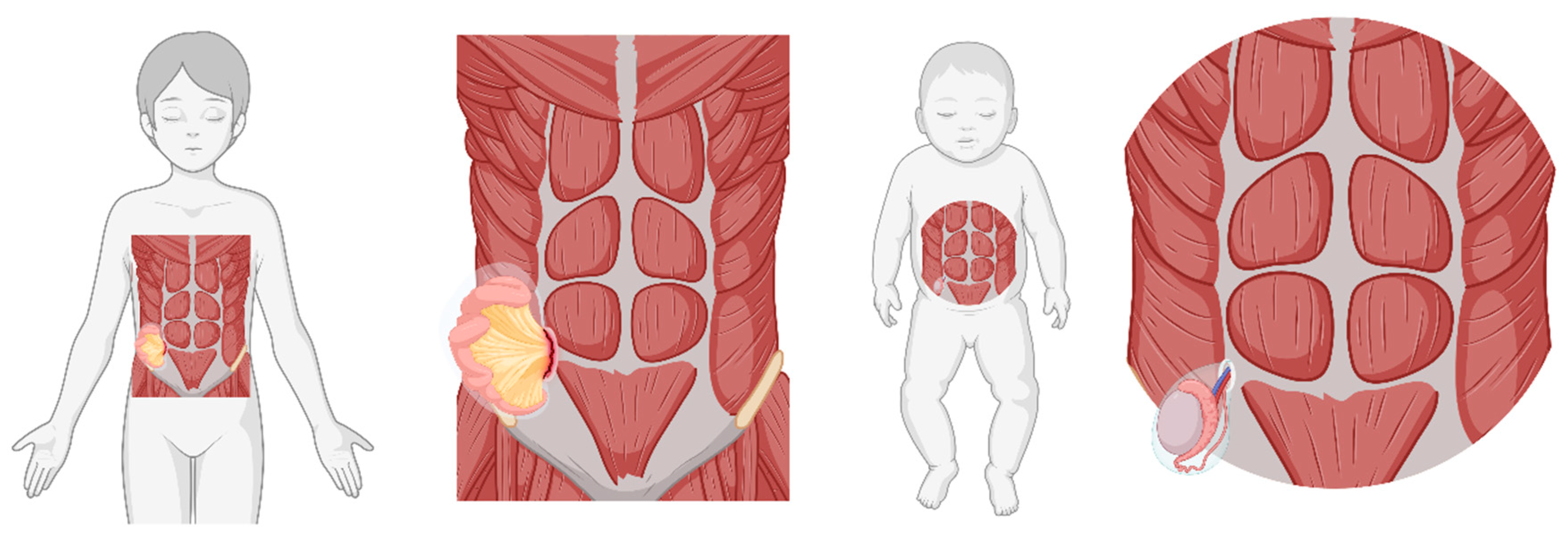

Anatomy and Embryology of Semilunaris Line (Spigelian Line)

Methods

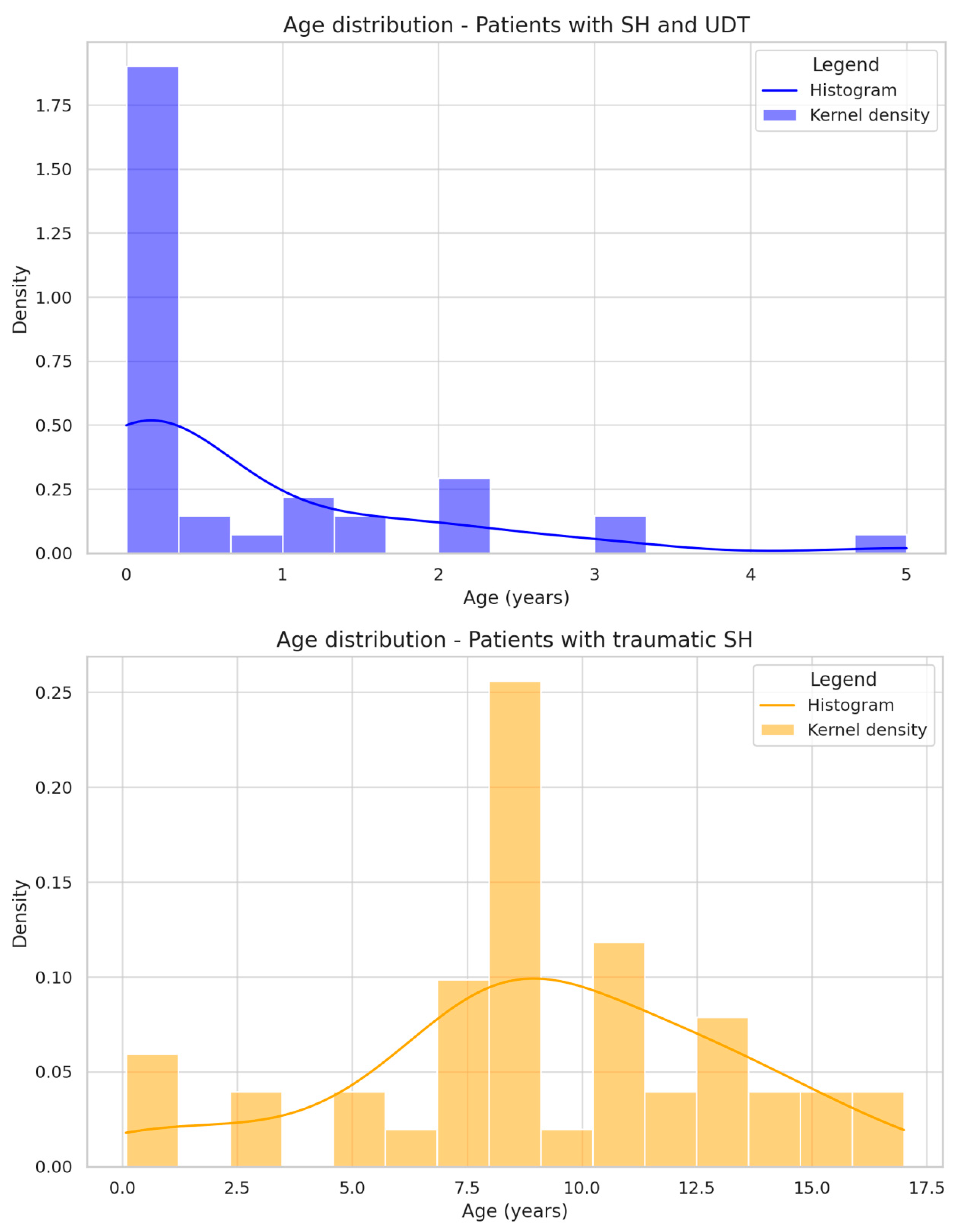

Results

Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Conflicts of interest

Financial statement/funding

Contributor declaration page (CRediT statement)

Original work

Data availability

Informed consent

Ethical Approval

References

- Skandalakis, P.N.; Zoras, O.; Skandalakis, J.E.; Mirilas, P. Spigelian hernia: Surgical anatomy, embryology, and repair technique. Am Surg. 2006, 72, 42–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huttinger, R.; Sugumar, K.; Baltazar-Ford, K.S. Spigelian Hernia. In StatPearls [Internet]; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island (FL), 2024. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hanzalova, I.; Schäfer, M.; Demartines, N.; Clerc, D. Spigelian hernia: Current approaches to surgical treatment-a review. Hernia 2022, 26, 1427–1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Jones, B.C.; Hutson, J.M. The syndrome of Spigelian hernia and cryptorchidism: A review of paediatric literature. J Pediatr Surg. 2015, 50, 325–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larsen, W.J. Human Embryology; Elsevier, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Sadler, T.W. Langman’s Medical Embryology; Wolters Kluwer, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, K.L.; Persaud, T.V.N.; Torchia, M.G. Before We Are Born: Essentials of Embryology and Birth Defects; Elsevier, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Vierstraete, M.; Pereira Rodriguez, J.A.; Renard, Y.; Muysoms, F. EIT Ambivium, Linea Semilunaris, and Fulcrum Abdominalis. J Abdom Wall Surg. 2023, 2, 12217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Scopinaro, A.J. Hernia in Spigel’s semilunar line in a newborn. Semana Med 1935, 1, 284. [Google Scholar]

- Hurwitt, E.S.; Borow, M. Bilateral Spigelian hernias in childhood. Surgery 1955, 37, 963–8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- LANDRYRM Traumatic hernia. Am J Surg. 1956, 91, 301–2. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isaacson, N.H. Spigelian Hernia. Report of four cases. Med Ann Dist Columbia 1956, 58, 23–26. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, T.H., Jr. Traumatic hernia of the abdominal wall. Am J Surg. 1959, 97, 340–1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts, G.R. TRAUMATIC ABDOMINAL WALL RUPTURE. Br J Surg. 1964, 51, 153–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertelsen, S. The surgical treatment of spigelian hernia. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1966, 122, 567–72. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hurlbut, H.J.; Moseley, T. Spigelian hernia in a child. South Med J. 1967, 60, 602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graivier, L.; Alfieri, A.L. Bilateral Spigelian hernias in infancy. Am J Surg. 1970, 120, 817–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graivier, L.; Bernstein, D.; RuBane, C.F. Lateral ventral (spigelian) hernias in infants and children. Surgery 1978, 83, 288–90. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Graivier, L.; Bronsther, B.; Feins, N.R.; Mestel, A.L. Pediatric lateral ventral (spigelian) hernias. South Med J. 1988, 81, 325–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herbert, R.J.; Turner, F.W. Traumatic Abdominal Wall hernia in a 7-year-old child. J Pediatr Surg 1977, 12, 609–610. [Google Scholar]

- Constantino, L.; Contestabile, D.; Rocua, E. Strangulated spigelian hernia in a child. Riv Chir Pediatr 1974, 16, 236–238. [Google Scholar]

- Atiemo, E.A.; Goswami, G. Traumatic ventral hernia. J Trauma. 1974, 14, 181–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Houlihan, T.J. A review of Spigelian hernias. Am J Surg. 1976, 131, 734–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jarvis, P.A.; Seltzer, M.H. Pediatric Spigelian hernia: A case report. J Pediatr Surg. 1977, 12, 609–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bar-Maor, J.A.; Sweed, Y. Spigelian hernia in children, two cases of unusual etiology. Pediatr Surg Int 1989, 4, 357–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchiner, J.C. Handlebar hernia: Diagnosis by abdominal computed tomography. Ann Emerg Med. 1990, 19, 812–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Damschen, D.D.; Landercasper, J.; Cogbill, T.H.; Stolee, R.T. Acute traumatic abdominal hernia: Case reports. J Trauma. 1994, 36, 273–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kubalak, G. Handlebar hernia: Case report and review of the literature. J Trauma. 1994, 36, 438–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Komura, J.; Yano, H.; Uchida, M.; Shima, I. Pediatric spigelian hernia: Reports of three cases. Surg Today. 1994, 24, 1081–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pul, N.; Pul, M. Spigelian hernia in children--report of two cases and review of the literature. Yonsei Med J. 1994, 35, 101–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wright, J.E. Spigelian hernia in childhood. Pediatr Surg Int 1994, 9, 170–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silberstein, P.A.; Kern, I.B.; Shi, E.C. Congenital spigelian hernia with cryptorchidism. J Pediatr Surg. 1996, 31, 1208–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iuchtman, M.; Kessel, B.; Kirshon, M. Trauma-related acute spigelian hernia in a child. Pediatr Emerg Care. 1997, 13, 404–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perez, V.M.; McDonald, A.D.; Ghani, A.; Bleacher, J.H. Handlebar hernia: A rare traumatic abdominal wall hernia. J Trauma. 1998, 44, 568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ostlie, D.J.; Zerella, J.T. Undescended testicle associated with spigelian hernia. J Pediatr Surg. 1998, 33, 1426–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kubota, A.; Shono, J.; Yonekura, T.; Hoki, M.; Asano, S.; Hirooka, S.; Kosumi, T.; Kato, M.; Oyanagi, H. Handlebar hernia: Case report and review of pediatric cases. Pediatr Surg Int. 1999, 15, 411–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Salem, A.H. Congenital spigelian hernia and cryptorchidism: Cause or coincidence? Pediatr Surg Int. 2000, 16, 433–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, J.J. Concomitant Spigelian and inguinal hernias in a neonate. J Pediatr Surg. 2002, 37, 659–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Losanoff, J.E.; Richman, B.W.; Jones, J.W. Spigelian hernia in a child: Case report and review of the literature. Hernia 2002, 6, 191–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fraser, N.; Milligan, S.; Arthur, R.J.; Crabbe, D.C. Handlebar hernia masquerading as an inguinal haematoma. Hernia 2002, 6, 39–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levy, G.; Nagar, H.; Blachar, A.; Ben-Sira, L.; Kessler, A. Pre-operative sonographic diagnosis of incarcerated neonatal Spigelian hernia containing the testis. Pediatr Radiol. 2003, 33, 407–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goliath, J.; Mittal, V.; McDonough, J. Traumatic handlebar hernia: A rare abdominal wall hernia. J Pediatr Surg. 2004, 39, e20–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raveenthiran, V. Congenital Spigelian hernia with cryptorchidism: Probably a new syndrome. Hernia 2005, 9, 378–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaos, G.; Gardikis, S.; Zavras, N. Strangulated low Spigelian hernia in children: Report of two cases. Pediatr Surg Int. 2005, 21, 736–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torres de Aguirre, A.; Cabello Laureano, R.; García Valles, C.; Garrido Morales, M.; García Merino, F.; Martínez Caro, A. Hernia de Spiegel: A propósito de 2 casos asociados a criptorquidia [Spigelian hernia: Two cases associated to cryptorchidism]. Cir Pediatr. 2005, 18, 99–100. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Durham, M.M.; Ricketts, R.R. Congenital spigelian hernias and cryptorchidism. J Pediatr Surg. 2006, 41, 1814–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O'Sullivan, O.; Bannon, C.; Clyne, O.; Flood, H. Hypospadias associated undescended testis in a Spigelian hernia. Ir J Med Sci. 2006, 175, 77–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, V.R. Ravi; Singal, Arbinder Kumar1,. Undescended testis in spigelian hernia. Journal of Indian Association of Pediatric Surgeons 2007, 12, 233–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aksu, B.; Temizöz, O.; Inan, M.; Gençhellaç, H.; Başaran, U.N. Bilateral spigelian hernia concomitant with multiple skeletal anomalies and fibular aplasia in a child. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2008, 18, 205–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Litton, K.; Izzidien, A.Y.; Hussien, O.; Vali, A. Conservative management of a traumatic abdominal wall hernia after a bicycle handlebar injury (case report and literature review). J Pediatr Surg. 2008, 43, e31–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fascetti-Leon, F.; Gobbi, D.; Gamba, P.; Cecchetto, G. Neonatal bilateral spigelian hernia associated with undescended testes and scalp aplasia cutis. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2010, 20, 123–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christianakis, E.; Paschalidis, N.; Filippou, G. Low Spigelian hernia in a 6-year-old boy presenting as an incarcerated inguinal hernia: A case report. J Med Case Reports 2009, 3, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rushfeldt, C.; Oltmanns, G.; Vonen, B. Spigelian-cryptorchidism syndrome: A case report and discussion of the basic elements in a possibly new congenital syndrome. Pediatr Surg Int. 2010, 26, 939–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Vega, Y.; Zequeira, J.; Delgado, A.; Lugo-Vicente, H. Spigelian hernia in children: Case report and literature review. Bol Asoc Med P R. 2010, 102, 62–4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Singal, A.K.; Ravikumar, V.R.; Kadam, V.; Jain, V. Undescended testis in Spigelian hernia--a report of 2 cases and review of the literature. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2011, 21, 194–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inan, M.; Basaran, U.N.; Aksu, B.; Dortdogan, Z.; Dereli, M. Congenital Spigelian hernia associated with undescended testis. World J Pediatr. 2012, 8, 185–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopez, R.; King, S.; Maoate, K.; Beasley, S. Trauma may cause Spigelian herniae in children. ANZ J Surg. 2010, 80, 663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, J.; Wood, J.; Bevan, C.; Cheng, W.; Wilson, G. Traumatic abdominal wall hernia--a case report and literature review. J Pediatr Surg. 2011, 46, 1642–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopez, R.; King, S.; Maoate, K.; Beasley, S. Laparoscopic repair of paediatric traumatic Spigelian hernia avoids the need for mesh. ANZ J Surg. 2011, 81, 396–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bilici, S.; Güneş, M.; Göksu, M.; Melek, M.; Pirinçci, N. Undescended testis accompanying congenital Spigelian hernia: Is it a reason, a result, or a new syndrome? Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2012, 22, 157–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rathore, A.; Simpson, B.J.; Diefenbach, K.A. Traumatic abdominal wall hernias: An emerging trend in handlebar injuries. J Pediatr Surg. 2012, 47, 1410–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Decker, S.; Engelmann, C.; Krettek, C.; Müller, C.W. Traumatic abdominal wall hernia after blunt abdominal trauma caused by a handlebar in children: A well-visualized case report. Surgery 2012, 151, 899–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parihar, D.; Kadian, Y.S.; Raikwar, P.; Rattan, K.N. Congenital spigelian hernia and cryptorchidism: Another case of new syndrome. APSP J Case Rep. 2013, 4, 41. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Thakur, S.K.; Gupta, S.; Goel, S. Traumatic spigelian hernia due to handlebar injury in a child: A case report and review of literature. Indian J Surg. 2013, 75, 404–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Upasani, A.; Bouhadiba, N. Paediatric abdominal wall hernia following handlebar injury: Should we diagnose more and operate less? BMJ Case Rep. 2013, 2013, bcr2012008501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Balsara, Z.R.; Martin, A.E.; Wiener, J.S.; Routh, J.C.; Ross, S.S. Congenital spigelian hernia and ipsilateral cryptorchidism: Raising awareness among urologists. Urology 2014, 83, 457–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spinelli, C.; Strambi, S.; Pucci, V.; Liserre, J.; Spinelli, G.; Palombo, C. Spigelian hernia in a 14-year-old girl: A case report and review of the literature. European J Pediatr Surg Rep. 2014, 2, 58–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Talutis, S.D.; Muensterer, O.J.; Pandya, S.; McBride, W.; Stringel, G. Laparoscopic-assisted management of traumatic abdominal wall hernias in children: Case series and a review of the literature. J Pediatr Surg. 2015, 50, 456–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pederiva, F.; Guida, E.; Maschio, M.; Rigamonti, W.; Gregori, M.; Codrich, D. Handlebar injury in children: The hidden danger. Surgery 2016, 159, 1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montalvo Ávalos, C.; Álvarez Muñoz, V.; Fernández García, L.; López López, A.J.; Oviedo Gutiérrez, M.; Lara Cárdenas, C. Atypical hernia defects in childhood. Rev Pediatr Aten Primaria. 2015, 17, 139–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volpe, A.; Virgone, C.; Gamba, P. Successful conservative management of handlebar hernia in children. Pediatr Int. 2017, 59, 105–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shea, B.; Fasano, G.; Cohen, I.T. Pediatric Spigelian hernia: A case report and review of the literature. Journal of Pediatric Surgery Case Reports 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamal, N.R.; Shubhangi, S. Spigelian Hernia in 2-Year-Old Male Child: A Rare Case Report. JOJ Case Stud. 2017, 3, 555612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinaldi, V.E.; Bertozzi, M.; Magrini, E.; Riccioni, S.; Di Cara, G.; Appignani, A. Traumatic Abdominal Wall Hernia in Children by Handlebar Injury: When to Suspect, Scan, and Call the Surgeon. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2020, 36, e534–e537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sinopidis, X.; Panagidis, A.; Alexopoulos, V.; Karatza, A.; Georgiou, G. Congenital Spigelian Hernia Combined with Bilateral Inguinal Hernias. Balkan Med J. 2018, 35, 402–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sengar, M.; Mohta, A.; Neogi, S.; Gupta, A.; Viswanathan, V. Spigelian hernia in children: Low versus classical. J Pediatr Surg. 2018, 53, 2346–2348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- So, H.F.; Nabi, H. Handlebar hernia - A rare complication from blunt trauma. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2018, 49, 118–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Vega-Mata, N.; Vázquez-Estevez, J.J.; Montalvo-Ávalos, C.; Raposo-Rodríguez, L. Laparoscopic Spigelian hernia repair in childhood. Literature review [Abordaje laparoscópico de una hernia de Spiegel en edad pediátrica. Revisión de la literatura]. Cir Cir. 2019, 87, 101–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deshmukh, S.S.; Kothari, P.R.; Gupta, A.R.; Dikshit, V.B.; Patil, P.; Kekre, G.A.; Deshpande, A.; Kulkarni, A.A.; Hukeri, A. Total laparoscopic repair of Spigelian hernia with undescended testis. J Minim Access Surg. 2019, 15, 265–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Nagara, S.; Fukaya, S.; Muramatsu, Y.; Kaname, T.; Tanaka, T. A case report of rare ZC4H2-associated disorders associated with three large hernias. Pediatr Int. 2020, 62, 985–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taha, A.; Algethami, N.E.; AlQurashi, R.; Alnemari, A.K. Outcome of Orchidopexy in Spigelian Hernia-Undescended Testis Syndrome. Cureus 2021, 13, e13714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- García Sánchez, P.; Bote Gascón, P.; González Bertolín, I.; Bueno Barriocanal, M.; López López, R.; de Ceano-Vivas la Calle, M. Handlebar Hernia: An Uncommon Traumatic Abdominal Hernia. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2021, 37, e879–e881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sinacer, S.; Semari, B.Z.; Khemari, S.; Kharchi, A.; Haif, A.; Soualili, Z. Congenital Spigelian hernia in a neonate associated with several anomalies: A case report. J Neonatal Surg 2021, 10, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thamri, F.; Houidi, S.; Zouaoui, A. Traumatic Spigelian hernia in a child. J Pediatr Surg Case Rep. 2021, 75, 102099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonuguntla, A.; Thotan, S.P.; Pai, N.; Kumar, V.; Prabhu, S.P. Congenital Spigelian Hernia With Ipsilateral Ectopic Testis. Ochsner J. 2022, 22, 277–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kropilak, A.D.; Sawaya, D.E. Traumatic Spigelian Hernia in a Pediatric Patient Following a Bicycle Injury. Am Surg. 2022, 88, 1933–1935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okumuş, M.; Zerbaliyev, E.; Akdağ, A. Congenital spigelian hernia and ipsilateral undescended testis: An ongoing etiological debate – A case report. Int J Abdom Wall Hernia Surg 2022, 5, 209–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kangabam, B. Traumatic Spigelian Hernia Following Blunt Abdominal Trauma. Cureus 2023, 15, e35564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Farina, R.; Pennisi, M.; Desiderio, C.; Valerio Foti, P.; D'Urso, M.; Inì, C.; Motta, C.; Galioto, S.; Garofalo, A.; Clemenza, M.; Ilardi, A.; Lavalle, S.; Basile, A. Spigelian-cryptorchidism syndrome: Lesson based on a case report. Radiol Case Rep. 2024, 19, 3372–3375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ablatt, S.; Escobar, M.A., Jr. Spigelian hernia and cryptorchidism syndrome: Open spigelian hernia repair and laparoscopic one-stage orchiopexy for ectopic testis. BMJ Case Rep. 2025, 18, e261858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

| Author | Country | Patient´s age | Patient´s Sex | Laterality | Associated malformations/anomalies | Complications associated with SP | Relevant background |

Defect size | Radiological studies | Treatment | Surgical approach/findings | Surgical outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scopinaro et al. (1935) [9] | - | 6-days-old | Male | - | - | Strangulation | - | - | - | - | - | Death |

| Hurwitt et al. (1955) [10] | - | 8y | Male | Bilateral | - | - | - | Right side: 2,6 cm | - | - | - | - |

| Landry et al. (1956) [11] | - | 14y | Male | Left | - | - | Previous local trauma | 4cm | - | - | - | - |

| Isaacson et al. (1956) [12]* | USA | 3y | Male | Right | - | - | Nail puncture | - | - | - | - | - |

| Wilson et al. (1959) [13] | USA | 2.5y | Male | Left | - | - | Previous local trauma (automobile) | - | Plain abdominal x-ray: traumatic hernia of the abdominal wall | Surgical | ESR 6 days after the accident Hernial sac containing omentum and transverse colon. Repair: Interrupted silk suture |

- |

| Roberts et al. (1964) [14]***** | UK | 9y | Male | Left | - | - | Previous local trauma (bicycle handlebar) | 7x3 cm | - | Surgical | Repair: Interrupted catgut suture | Favorable (6m follow-up) |

| Bertelsen S (1966) [15]* | - | 9y | Male | Right | - | - | - | 2x2 cm | - | - | - | Favorable |

| Hurlbut et al. (1967) [16] | USA | 8y | Male | Right | - | - | Previous local trauma | 3x5 cm | Plain abdominal X-ray: gas-filled small bowel loops compatible with incarcerated hernia | Surgical | ESR | Favorable |

| Graivier et al. (1967-1988) [17-19]. | USA | 1) 10m 2) 6m 3) 6m 4) 9m 5) 15y 6)17y 7)15m 8)4y 9)10d |

1) Male 2) Male 3) Male 4) Male 5) Female 6) Female 7) Female 8) Female 9) Female |

1) Bilateral 2) Right 3) Right 4) Left 5) Right 6) Bilateral 7) Bilateral 8) Left 9) Left |

1) Umbilical Hernia and bilateral indirect Inguinal hernias |

- | - | 1) 2x5 cm (left) 1x3 cm (right) |

- | Surgical | Patients 1-8: ESR Patient 9: loss of follow-up previous to surgery Hernial sacs: resected or reduced Repair: Interrupted silk suture |

Favorable. No recurrences (follow-up up to 19y) |

| Herbert et al. (1973) [20] | Canada | 7y | Male | Left | - | - | Previous local trauma (bicycle handlebar) | 4cm | Plain Abdominal X-ray: acute gastric dilatation | Surgical | ESR 3 weeks after the accident. SH Repair: Interrupted 2-0 polyglycolic acid suture. | Favorable |

| Constantino et al. (1974) [21] | - | 8y | Male | Left | - | Strangulation | - | - | - | - | - | Favorable |

| Atiemo et al. (1974) [22]***** | Ghana | 6y | Male | Left | Splenic enlargement (physical examination) | - | Previous local trauma (cow goring) | - | - | Surgical | ESR 6 days after the accident. Full abdominal wall hernia. Primary repair. | Favorable |

| Houlihan et al. (1976) [23] | USA | 21y | Male | Bilateral | - | - | - | - | - | - | ESR | Favorable |

| Jarvis et al. (1977) [24] | USA | 13y | Female | Left | - | - | - | 3 cm | - | Surgical | SH. Peritoneal sac present. | - |

| Bar-Maor et al. (1989) [25] | Israel | 1) 5y 2) 3m |

1) Female 2) Male |

1) Right 2) Left |

2) Left Bochdalek hernia | - | 1) Abdominal blunt trauma (road accident) 2) Previous abdominal surgery with forceful stretching of the abdominal wall (Bochdalek hernia) |

1) 4 cm 2) 1 cm |

- | 1) Conservative (spontaneous resolution) 2) Surgical |

ESR. SH | Favorable |

| Mitchiner et al. (1990) [26]***** | USA | 7y | Male | Left | - | Incarceration | Previous local trauma (bicycle handlebar) | 6 cm | CT (oral and intravenous contrast media): rent in the anterior abdominal wall with a loop of small bowel exteriorized in the subcutaneous tissue | Surgical (Urgent) |

3 feet of viable small bowel found in the subcutaneous tissue protruding through a large fascial defect. Reduction and primary repair. |

Favorable (4 months follow-up) |

| Damschen et al. (1994) [27]***** | USA | 5y | Male | Right | - | - | Previous local trauma (bicycle handlebar) | - | - | Surgical | Urgent surgery: SH. Small bowel herniating through the muscle layers. Repair: Interrupted polyglycolic acid suture. | Lost to follow-up (unknown) |

| Kubalak G (1994) [28]***** | USA | 8y | Male | Right | - | - | Previous local trauma (bicycle handlebar) | 6 cm | - | - | - | Favorable (2y follow-up) |

| Komura et al. (1994) [29] | Japan | 1) 6m 2) 8m 3) 3y |

1) Female 2) Female 3) Male |

1) Right 2) Right 3) Left |

1) Ipsilateral mediastinal neuroblastoma (10-12th IC spaces) - Incidental diagnosis of tumor during ultrasound examination of the SH. 2) Ipsilateral mediastinal neuroblastoma (9-10th IC spaces) |

- | 2) Previous tumor extirpation (1 week before) | 1) 5x3 cm 2) 4cm 3) 7cm |

3) US: hernial orifice 4x3 cm. Thin muscular layer in the area (3 mm). MRI: fatty infiltration of internal oblique/transverse muscles | 1) Surgical 2) Conservative 3) Surgical |

1) SH. Peritoneal sac present. Primary repair (mattress 3-0 silk sutures)** 3) SH. Primary repair (mattress 2-0 silk sutures)** |

1) Favorable (5y follow-up) 2) Favorable (spontaneous resolution) *** 3) Favorable (2m follow-up) |

| Pul et al. (1994) [30] | Turkey | 1) 18m 2) 2,5m |

1) Male 2) Male |

1) Right 2) Right |

1) Right UDT 2) Right indirect inguinal hernia |

- | - | 1) 7x7 cm 2) 4x4 cm |

1) Surgical | 1) SH. Small ring defect (1x1cm). Peritoneal sac present and excised. Primary repair. 2) SH. Small ring defect (2 cm). Peritoneal sac present and excised. Primary repair. |

1) Favorable 2) Favorable |

|

| Wright JE. (1994) [31] | Australia | 1) 19m 2) 5y 3) 7y |

1) Male 2) Male 3) Male |

1) Right 2) Right 3) Left |

- | - | - | - | - | 3) Surgical | 3) SH. Peritoneal sac present (not excised). Two-layer repair | 3) Favorable (8y follow-up) |

| Silberstein et al. (1996) [32] | Australia | 1) Newborn 2) Newborn |

1) Male 2) Male |

1) Left 2) Right |

1) Contralateral generalized abdominal musculature weakness. Left UDT. 2) Right UDT. |

- | - | 2) 3 cm | - | 1) Surgical (10w of age) 2) Surgical (4.5m of age) |

1) SH. Peritoneal sac present containing left testis (small in size, without testicular-epididymal dissociation). Absence of inguinal canal. Primary repair and orchidopexy. 2) HS. The internal oblique and transversalis muscles were poorly developed. Peritoneal sac present containing right testis. Absence of inguinal canal. Primary repair and orchidopexy. |

- |

| Iuchtman et al. (1997) [33] | Israel | 7y | Male | - | - | - | Previous local trauma (bicycle) | - | US: normal | Surgical | Urgent surgery: SH. Peritoneal protrusion (intact peritoneum). Primary repair without mesh. | Favorable |

| Pérez et al. (1998) [34]***** | USA | 11y | Male | Left | - | - | Previous local trauma (bicycle handlebar) | - | - | Surgical | Urgent surgery: SH. Peritoneal tearing. Repair in layers. | Favorable |

| Ostlie et al. (1998) [35] | USA | Newborn | Male | Right | 1) Right UDT. The right testis was palpable on the hernial sac. | - | - | 1.5 cm | - | Surgical | SH. Thinning of the layers. Absence of inguinal canal. Peritoneal sac containing the right testis. Primary repair (absorbable sutures) and orchidopexy. | - |

| Kubota et al. (1999) [36]***** | Japan | 9y | Male | Right | - | - | Previous local trauma (bicycle handlebar) | 4 cm | CT: rent in the abdominal wall through which intestinal loops protruded into the subcutaneous space. |

Surgical | SH. Peritoneal rupture. Primary repair | Favorable |

| Al-Salem et al. (2000) [37] | Saudi Arabia | 1) 3m 2) Newborn |

1) Male 2) Male |

1) Left 2) Left |

1) Left UDT. 2) Micrognathia, cleft palate, malformed ears, right clubfoot, malformed left lower limb, left UDT. Left testis palpable on the hernial sac. (Insulin-dependent diabetic mother). |

- | - | 1) 5 cm | 1) US: normal | 1) Surgical | 1) SH. Peritoneal sac present containing left testis (small in size, without testicular-epididymal dissociation) and sigmoid colon. Primary repair and orchidopexy. | 1) Favorable (2.5y follow-up) 2) Died before surgery (sepsis, not related to SH) |

| White J (2002) [38] | USA | 1m | Female | Right | Bilateral inguinal hernia. | Incarceration/small bowel obstruction. | SH appeared in the immediate postoperative period after bilateral inguinal hernia repair. | 1.5 cm (ring) | Plain abdominal X-ray: Partial small bowel obstruction US: bowel in the mass, under the skin |

Surgical | SH. Reduction of the small bowel, primary repair. | Favorable |

| Losanoff et al. (2002) [39] | USA | 12y | Male | Right | - | Omentum incarceration mimicking acute appendicitis. | . | 1.5 cm | Plain chest and abdominal X-rays: Normal | Surgical (urgent) | Normal appendix. SH with incarcerated and infarcted omentum. Resection, primary repair | Favorable (6m follow-up) |

| Fraser et al. (2002) [40]***** | UK | 11y | Male | Right | - | Inguinal hematoma | Previous local trauma (bicycle handlebar) | 12x8 cm (bulge) | US: disruption of the muscle layers of the abdominal wall with bowel and free fluid lateral to the rectus muscle. Plain abdominal X-ray (lateral): A collection of gas was visible in the anterior abdominal |

Surgical | Traumatic hernia involving all layers of the lower abdominal wall above the inguinal canal. Primary repair (absorbable suture). | Favorable |

| Levy et al. (2003) [41] | Israel | 1) 1m 2) 5w |

1) Male 2) Male |

1) Bilateral 2) Left |

1) Bilateral UDT. 2) Left UDT. |

1) Incarceration | - | 2) 5 cm | 1) US (Right side): HS containing Incarcerated bowel loops and the undescended right testis US (Left side): small SH containing the undescended left testis 2) US: left SH containing bowel loops and the undescended left testis |

1) Right side: Surgical (urgent) Left side: Surgical (deferred, with 10m) 2) Surgical (deferred, with 2m) |

1) Right side: SH. Small bowel reduction, primary repair, right orchidopexy Left side: SH primary repair, left orchidopexy 2) SH. Peritoneal sac present containing small bowel and left testis. Reduction, primary repair, and orchidopexy |

Favorable |

| Goliath et al. (2004) [42] ***** | USA | 11y | Male | Right | - | - | Previous local trauma (bicycle handlebar) | - | CT: Intestinal loops protruding through a defect in the abdominal wall into the subcutaneous space. |

Surgical | Defect throughout his entire abdominal wall, including the fascia, muscular layers, and peritoneum, with bowel protruding into the subcutaneous space, leaving his skin and intraabdominal organs completely intact. Primary repair |

Favorable |

| Raveenthiran V (2005) [43] | India | Newborn (2d) | Male | Right | Imperforate anus. Bilateral UDT. Hypoplastic scrotum. Left inguinal hernia (noted with 1m of life), umbilical hernia (noted with 2m of life) | - | - | 5x5cm | US: bowel loops in the intermuscular plane at the site of the SH | Surgical (deferred, with 13m) | SH. Peritoneal sac present containing right testis. Absence of inguinal canal. | Favorable |

| Vaos et al. (2005) [44] | Greece | 1) 20m 2) 8m |

1) Male 2) Male |

1) Left 2) Right |

- | 1) Strangulation 2) Strangulation |

- | 1) 2.5 cm (bulge), 2 cm (ring) 2) 2 cm (bulge), 1 cm (ring) |

1) Plain abdominal X-ray: several gas-fluid levels in the small bowel | 1) Surgical (urgent) 2) Surgical (urgent) |

1) SH. Peritoneal sac present containing incarcerated viable small bowel loops and infarcted omentum. Omentectomy, reduction, primary repair. 2) SH. Peritoneal sac present containing incarcerated viable small bowel loops. Reduction, primary repair. |

1) Favorable (12m follow-up) 2) Favorable (6m follow-up) |

| Torres de Aguirre (2005) [45] | Spain | 1) Newborn 2) Infant (5w) |

1) Male 2) Male |

1) Right 2) Bilateral |

1) Right UDT. 2) Bilateral UDT. |

1) Incarceration 2) Right incarceration |

- | - | 1) US and Plain abdominal x-ray: incarcerated right inguinal hernia | 1) Surgical (urgent) 2) Surgical (urgent) |

1) SH. Peritoneal sac present containing incarcerated small bowel and right testis. Reduction, primary repair, and orchidopexy 2) Bilateral SH. Right: Peritoneal sac present containing incarcerated viable small bowel loops. Reduction, primary repair. Left: peritoneal sac present containing a hypoplastic left testis with epididymal-testicular dissociation. Orchiectomy and primary repair. |

Favorable |

| Durham et al. (2006) [46] | USA | 1) 8m 2) 13m 3) 14m**** 4) 2m**** |

1) Male 2) Male 3) Male 4) Male |

1) Left 2) Bilateral 3) Bilateral 4) Right |

1) Left UDT 2) Bilateral UDT 3) Bilateral UDT 4) Bilateral UDT |

- | - | - | - | Surgical | 1) SH. Peritoneal sac present containing left testis. Orchidopexy and primary repair 2) bilateral SH. Staged repair: right side with 13m and left with 16m. Peritoneal sac present containing testes. Orchidopexy and primary repair (absorbable sutures, 8-ply SIS mesh on right side) 3) bilateral SH. Repair. Testicles found in their ipsilateral SH sac. Orchidopexy and primary repair 4) With 13m: Right intraabdominal testis: orchidopexy. Right SH: primary repair. With 16m: left inguinal orchidopexy. |

1) Complication: scrotal abscess. Loss of follow-up 2) Favorable (laxity on the right side where the SIS patch was used) 3) Favorable (45m follow-up) 4) Favorable (12m follow-up) |

| O´Sullivan et al. (2006) [47] | Ireland | 4m | Male | Left | Left UDT. Hypospadias. | - | - | - | - | Surgical | SH. Peritoneal sac present containing left testis. Orchidopexy, primary repair. | - |

| Kumar et al. (2007) [48] | India | 3y | Male | Right | Right UDT. | - | - | 7 cm (neck of peritoneal sac) | - | Surgical | SH. Peritoneal sac present containing right testis. Orchidopexy, primary repair (VYPRO mesh) | Favorable |

| Aksu et al. (2007) [49] | Turkey | 4y | Female | Bilateral | Consanguineous parents. Multiple skeletal anomalies. | - | - | 6.5 cm (bulges), 3x2 cm (right ring) 2x1 cm (left ring) |

- | Surgical | Bilateral SH. Internal oblique and transverse abdominus missing. Peritoneal sac present containing small bowel loops. Reduction, primary repair (3/0 Vicryl sutures). | Favorable (8m follow-up) |

| Litton et al. (2008) [50]***** | UK | 13y | Male | Right | - | - | Previous local trauma (bicycle handlebar) | CT: herniation of bowels. No intraabdominal injury | Conservative (spontaneous resolution) | - | Favorable (4m follow-up) | |

| Fascetti-Leon et al. (2009) [51] | Italy | Newborn | Male | Bilateral | Bilateral UDT. Scalp aplasia cutis. Hypertelorism, delayed growth, small head circumference, hypoplasia of the nasal alae, dentition anomalies | - | - | - | US: bilateral SH. Bilateral UDT | Surgical | Bilateral SH. Peritoneal sac present containing testes. Orchidopexy and primary repair (VICRYLTM mesh) | Favorable (12m follow-up) |

| Christianakis et al. (2009) [52] | Greece | 6y | Male | Left | - | Inguinoscrotal pain | - | 1.5 cm (ring) | - | Surgical | SH. Peritoneal sac present. Primary repair (non-absorbable sutures) | Favorable (8y follow-up) |

| Rushfeldt et al. (2010) [53] | Norway | Newborn | Male | Right | Right UDT | Incarceration | - | - | US: SH with hernial sac between the obliquus externus and the obliquus internus (7mm hernia opening) containing right testis and a loop of small bowel. | Surgical (urgent) | SH. Peritoneal sac present containing incarcerated viable small bowel loops and right testis Reduction, orchidopexy, primary repair. | Favorable |

| Vega et al. (2010) [54] | Puerto Rico | 9y | Male | Left | - | - | - | - | - | Surgical | SH. Primary repair. | - |

| Singal et al. (2011) [55] | India | 1) 3y 2) 3m |

1) Male 2) Male |

1) Right 2) Left |

1) Right UDT 2) Left UDT. Glanular hypospadias |

- | - | 1) 7 cm (ring/neck) | - | Surgical | 1) SH. Thinned out internal oblique. Peritoneal sac present containing right testis. Orchidopexy and primary repair (VYPRO mesh) 2) SH. Peritoneal sac present containing left testis. No inguinal canal nor gubernaculum present. Orchidopexy and primary repair |

1) Favorable (4y follow-up) 2) Favorable (1y follow-up) |

| Inan et al. (2011) [56] | Turkey | Newborn (26d) | Male | Right | Right UDT | - | - | 3 cm (bulge), 2 cm (ring) | US: fascial plane defect through the linea semilunaris with herniation of bowel loops between the internal and external oblique muscles. Absence of testis in right scrotum. No inguinal canal nor spermatic cord. |

Surgical | SH. Thinning of layers. Peritoneal sac present containing right testis. Orchidopexy and primary repair. | Complication: scrotal abscess (postoperative day 8) and atrophy of the testis |

| Lopez et al. (2011) [57,58] | New Zealand | 14y | Male | Left | - | - | Previous local trauma (bicycle handlebar) | - | CT: herniation of fat and vessels through a defect in the abdominal wall musculature consistent with a diagnosis of SH |

Surgical | SH. Laparoscopic repair | - |

| Yan et al. (2011) [59] ***** | Australia | 8y | Male | Right | - | - | Previous local trauma (BMX handlebar) | - | CT: TAWH | Surgical (urgent) | TAWH. Primary repair | Favorable (1m follow-up) |

| Bilici et al. (2012) [60] | Turkey | 1) 6m 2) 1y 3) 2y 4) 5y |

1) Male 2) Male 3) Male 4) Male |

2 patients: left 2 patients: right |

4 patients: Ipsilateral UDT | 4 patients: abdominal distension | - | 1.5 to 2.5 cm | - | Surgical | SH. Peritoneal sac present containing ipsilateral testis (all cases). Absence of inguinal canal Orchidopexy and primary repair | Favorable (6m follow-up) |

| Rathore et al. (2012) [61] ***** | USA | Five patients (9-15y) 1) 15y 2) 15y 3) 13y 4) 9y 5) 11y |

All male | - | - | Three patients with associated visceral injury: 1,4) cecal wall hematoma, 2) duodenal hematoma, pancreatic contusion | Previous local trauma (bicycle handlebar) in all patients | - | CT (patient no.5): compatible with an SH | Surgical | - | 2) pancreatic pseudocyst. 1) persistent pain. Three cases evolved favorably. |

| Decker et al. (2012) [62] ***** | Germany | 13y | Male | Right | - | Abdominal wall hematoma | Previous local trauma (bicycle handlebar) | - | CT: 18.39 mm gap in the fascia of the abdominal rectus muscle and the internal and external oblique muscles with two intestinal loops | Surgical | SH. Primary repair. | Favorable |

| Parihar et al. (2013) [63] | India | 3m | Male | Right | Right UDT | - | - | - | US: testis in the layers of the abdominal wall, along with small bowel loops, echoes. | Surgical | SH. Peritoneal sac present containing ipsilateral testis. Absence of inguinal canal. Orchidopexy and primary repair | Favorable |

| Thakur et al. (2013) [64] | India | 9y | Male | Right | - | - | Previous local trauma (bicycle handlebar) 5 weeks before | 6x4 cm (bulge), 4x4 cm (ring) |

US: 4x4 cm defect along the right semilunar line with small bowel loops | Surgical | SH. Peritoneal sac present (opened). Primary repair (non-absorbable sutures) | Favorable (18m follow-up) |

| Upasani et al. (2013) [65] ***** | UK | 12y | Male | Left (upper) | - | - | Previous local trauma (BMX handlebar) | 10x10 cm (bulge),2cm (ring) | US: abdominal wall hematoma. CT: 2 cm fascial defect with fat herniating through the defect | Conservative (partial resolution) | - | Favorable (6m follow-up) |

| Balsara et al. (2014) [66] | USA | Newborn (2w) | Male | Left | Left UDT | - | - | - | US: normal-sized left testicle within the SH in the left lower quadrant with loops of bowel. | Surgical | Exploratory laparoscopy: vas deferens and spermatic vessels entering the hernia sac. Left testis confirmed to lie within the sac itself. Open correction: SH. Hernial sac present containing left testis. Orchidopexy and primary repair. | Favorable (7m follow-up) |

| Spinelli et al. (2014) [67] | Italy | 14y | Female | Right | - | One-year history of recurrent abdominal pain. | - | 1.5 cm | US: fascial defect in right hemiabdomen | Surgical | SH. Hernia lipoma. Peritoneal sac present containing greater omentum. Reduction and primary repair. | Favorable |

| Talutis et al. (2014) [68] | USA | 1) 9y 2) 7y 3) 11y 4) 7y |

1) Male 2) Male 3) Male 4) Female |

1) Left 2) Right 3) Left 4) Right |

- | 1) Contusion to the mid-jejunum. 2) Mesenteric defect in the ileocecal region 4) Ileal perforation |

1,3,4) Previous local trauma (bicycle handlebar) 2) ATV collision |

1) 4x3 cm | 1) CT: 4x3 cm fascial defect (SH) with a contusion to the mid-jejunum. 4) CT: Handlebar sign. Evidence of RLQ abdominal wall defect with herniation |

1-3) Surgical | 1,3,4) Laparoscopic. Conversion to open surgery. 2) Open surgery |

1-4) Favorable |

| Pederiva et al. (2015) [69] ***** | Italy | 9y | Male | Left | - | Ileal perforation (not diagnosed at CT) | Previous local trauma (bicycle handlebar) | - | CT: abdominal wall hematoma. Defect through rectus sheath between left rectus abdominis and internal and external oblique. Intraabdominal fat herniated through the defect. | Surgical | Laparotomy. Intestinal resection. Primary repair (absorbable sutures). | Favorable |

| Montalvo et al. (2015) [70] | Spain | 1m | Female | Left | Left UDT | - | - | - | US (NR) | - | SH. Laparoscopic approach: Peritoneal sac present containing left testis. Orchidopexy. NO primary repair | Favorable (unknown follow-up) |

| Volpe et al. (2016) [71] ***** | Italy | 1) 8y 2) 9y |

1) Male 2) Male |

1) Right 2) Right |

- | - | 1) Previous local trauma (bicycle handlebar) 2) Previous local trauma (bicycle handlebar) |

1) 1.5 cm 2) 1 cm |

1) US: 1.5 cm hernia between the rectus and the internal oblique with herniation of the omentum 2) US: 1 cm defect with bowel herniation |

1) Conservative 2) Conservative |

- | 1) Favorable (last control: 3mm defect) (12m follow-up 2) Favorable (last control: 3 mm defect) (2m follow-up |

| Shea et al. (2017) [72] | USA | 16y | Male | Left | - | - | Previous local trauma (bicycle handlebar) | 1x1cm | CT: SH in the anterior left lower abdominal wall. | Surgical | SH. No peritoneal sac. Primary repair (absorbable sutures) | Favorable |

| Kamal et al. (2017) [73] | India | 2y | Male | Right | Patchy frontal hair loss, left eye deviation, bilateral UDT. | - | - | - | US: defect in the anterior abdominal wall lateral to the rectus muscle with herniation of preperitoneal fat. Absence of both testes in the scrotal sac. CT: SH with small bowel herniation. Both testes on the inguinal region | Surgical | SH. Peritoneal sac present. Primary repair One month later, bilateral orchidopexy. |

Favorable |

| Rinaldi et al. (2017) [74] ***** | Italy | 1) 12y 2) 13y |

1) Male 2) Male |

1) Left 2) Right |

- | - | 1) Previous local trauma (bicycle fall) 2) Previous local trauma (bicycle fall) |

1) 5 cm | 1) US: no peritoneal lesions; CT: defect in left anterior abdominal wall between lateral margin of the left rectus and medial margin of ipsilateral oblique muscles. 2) US: right rectus hemorrhage, free liquid in the right lower quadrant. CT: defect of the right anterior abdominal wall, with a slight separation between the right rectus and the oblique muscules. |

1) Surgical (urgent) 2) Surgical (urgent) |

1) SH. Omentum identified under the skin. Primary repair (absorbable sutures). 2) Exploratory laparoscopy. Peritoneal repair (partial report) |

1) Favorable 2) Favorable |

| Sinopidis et al. (2018) [75] | Greece | Newborn | Male | Left | Bilateral inguinal hernias | - | - | - | US: preperitoneal fat protruding through a defect of the transversalis fascia | Surgical | 2-month-old: bilateral inguinal hernia repair 5-month-old: SH. Preperitoneal fat adhered to the tip of the hernial sac. Primary repair. |

Favorable (18m follow-up) |

| Sengar et al. (2018) [76] | India | 1) 12y 2) 4y 3) 4y 4) 2.5y 5) 2.3y 6) 2y 7) 1.6y 8) 1m 9) 1m 10) 6d |

1) Female 2) Female 3) Male 4) Male 5) Male 6) Male 7) Male 8) Female 9) Male 10) Male |

1) Bilateral 2) Right 3) Left 4) Bilateral 5) Right 6) Right 7) Right 8) Left 9) Right 10) Left |

5) Right UDT 6) Right UDT 7) Right UDT 9) Umbilical hernia, lumbar hernia 10) Hypospadias |

- | - | - | - | Surgical | 3) SH containing small bowel 5,6,7,10) SH containing testis. All testes were normal without epidydimal-testicular dissociation. In all cases orchidopexy was performed. 2 cases could be brought down up to a high scrotal level only All cases: primary repair. |

Favorable (2m-8y follow-up) |

| Fai-So et al. (2018) [77] ***** | Australia | 10y | Male | Left | - | Incarcerated sigmoid colon | Previous local trauma (bicycle handlebar) | - | CT: SH with a loop of sigmoid colon | Surgical (urgent) | Exploratory laparoscopy. Primary repair (laparoscopic). Absorbable sutures. | Favorable (5w follow-up) |

| Vega-Mata et al. (2019) [78] | Spain | 13y | Male | Right | - | Obesity (BMI 32.5) | - | - | US: 7mm SH with fat herniation | Surgical | SH. Peritoneal sac containing omentum. Primary repair (laparoscopic). Non-absorbable sutures. | Favorable (1y follow-up) |

| Deshmukh et al. (2019) [79] | India | 11m | Male | Left | Left UDT | - | - | - | - | Surgical | SH. Laparoscopic repair: Peritoneal sac present containing left testis. Orchidopexy and primary repair | - |

| Nagara et al. (2020) [80] | Japan | Newborn | Male | Left | Right-sided inguinal hernia. Left UDT. ZC4H2 associated disorders: Congenital contractures of upper and lower extremities, hypokinesia, paraesophageal hiatal hernia |

Small bowel incarceration | - | - | CT: left SH with incarcerated small bowel. Right-sided inguinal hernia. | Conservative | - | Death (SH incarceration, sepsis) |

| Taha et al. (2021) [81] | Saudi-Arabia | 50d | Male | Right | Right UDT | Incarceration | - | - | Plain abdominal X-ray: distended bowel loops, gasless lower abdomen, and right lower quadrant lucency. US: small amount of intraperitoneal free fluid and a loop of bowel herniated through the abdominal wall, defect; the defect was (10 mm) in diameter. |

Surgical (urgent) | SH. Peritoneal sac present containing fluid, small bowel loops, and the right testis. Reduction, orchidopexy, primary repair | Complication: scrotal infection (conservative management). Testicular atrophy (2y follow-up) |

| García-Sanchez et al. (2021) [82] ***** | Spain | 11y | Female | Right | - | - | Previous local trauma (bicycle handlebar) | 2.4x1.8 cm | US: 2.4x1.8 cm defect between rectus abdominis and oblique/transversus with omentum and small bowel loops inside | Surgical | - | Favorable (1w follow-up) |

| Sinacer et al. (2021) [83] | Algeria | Newborn | Male | Right | Right inguinal hernia (incarcerated), bilateral UDT, polydactyly (right hand), anal stenosis (type 1 diabetic mother) | - | - | 1.5 cm | - | Surgical | SH. Peritoneal sac present containing small bowel loops and the left testis. Reduction, orchidopexy, primary repair (non-absorbable sutures) | - |

| Tahmri et al. (2021) [84] | Tunisia | 9y | Male | Right | - | - | Previous local trauma (bicycle handlebar) | 2 cm | US: right rectus abdominis hematoma. Diastasis between the lateral edge of the rectus abdominis and the ipsilateral oblique and transverse muscles resulting in a 14 mm hernia sac containing omentum | Surgical | SH. Peritoneal sac present. Primary repair (absorbable sutures) | Favorable |

| Gonuguntlaet al. (2022) [85] | India | 3m | Male | Left | Left UDT | - | - | - | US: 2 abdominal wall defects. 1) in the left iliac fossa (1.6 cm) 2) posterosuperior to the the first defect in the posterior abdominal wall lateral to the kidney (1.3 × 0.6 cm). Left testis not visible. |

Surgical | SH. Laparoscopic repair. Absence of inguinal canal and gubernaculum.Orchidopexy and primary repair | Favorable (1y follow-up) |

| Kropilak et al. (2022) [86] | USA | 8y | Male | Left | - | - | Previous local trauma (bicycle handlebar) | - | CT: traumatic SH in the left lower quadrant with incarceration of loops of small bowel and associated stranding of surrounding tissues. | Surgical (urgent) | Diagnostic laparoscopy. Laparotomy conversion. SH. Small bowel mesenteric injury with a devitalized jejunum. Intestinal resection and anastomosis. Primary repair (absorbable suture) | |

| Okumus et al. (2022) [87] | Turkey | Newborn | Male | Right | Right UDT | - | - | 2-3 cm | Plain abdominal X-ray: intestinal loops under the skin, US: Ventral hernia | Surgical | SH. Peritoneal sac present containing the right testis. Orchidopexy, primary repair. | Favorable (6m follow-up) |

| Kangabam et al. (2023) [88] | India | 17y | Male | Right | - | - | Previous local trauma (motorcycle handlebar) | 1 cm | US: 1x1 cm defect in right Spigelian aponeurosis with herniating bowel loops CT: confirmation of findings |

Conservative (patient´s choice) | - | - |

| Farina et al. (2024) [89] | Italy | 4m | Male | Left****** | Left UDT | Large Bowel Incarceration | - | US: 5,8 mm hernia breach containing a sac with colon loop, adipose tissue, fluid collection and a testicle. | Surgical (urgent) | Herniopexy and testicle repositioning in the scrotal sac | Favorable | |

| Ablatt et al. (2025) [90] | USA | 2w | Male | Left | Left UDT, bilateral inguinal hernia, umbilical hernia | - | - | US: left inguinal hernia containing fluid and nonobstructive bowel. SH not diagnosed. | Surgical (urgent) | Open umbilical hernia repair, laparoscopic left orchiopexy, open SH repair, open left inguinal hernia repair, open right inguinal hernia repair | Favorable (6w follow-up) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).