Introduction

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is a chronic condition characterized by high blood sugar levels due to the body's inability to produce or effectively use insulin. This condition disrupts the metabolism of carbohydrates, fats, and proteins, leading to various health complications. The main types of diabetes include type 1 diabetes (an autoimmune condition where the body attacks insulin-producing cells), type 2 diabetes (where the body becomes resistant to insulin or doesn't produce enough), and gestational diabetes diagnosed or develops during early or mid-pregnancy [

1].

Diabetes mellitus can lead to a range of serious long-term complications affecting various parts of the body. Chronic high blood sugar levels can damage small and large blood vessels and nerves, leading to conditions such as heart disease, stroke, kidney disease, and eye problems [

2]. One of the most common complications is diabetic neuropathy (DN), and about 60% of diabetic men have varying degrees of nerve injury manifested by neuropathic pain, numbness, and tingling, particularly in the legs and feet. It has been reported that diabetic neuropathic pain is associated with local neuroinflammation and activation of glial cells where microglia and astrocytes become activated and release inflammatory mediators, which play a role in regulating pain signal transmission [

3].

Diabetic-induced hyperalgesia is a condition where individuals with diabetic neuropathy experience an increased sensitivity to pain. This can manifest as spontaneous pain or heightened responses to normally non-painful stimuli. The mechanisms behind hyperalgesia are complex and involve factors such as the formation of advanced glycation end products, inflammatory cytokines, and oxidative stress [

4].

Flavonoids are a group of natural substances, with different phenolic structures, can be found in fruits, vegetables, grains, roots, bark, stems, flowers, tea and wine. These natural products have many health benefits as they contain biologically active phytochemical constituents [

5].

Flavonoids have been used in cosmetics, anti-wrinkle skin care products [

6], and in natural dyes [

7]. However, the most pronounced applications of flavonoids are in medical field. Flavonoids have been widely used as antioxidant, anticancer, antimicrobial, antiviral, antiangiogenic, neuroprotective, and antiproliferative agents [

8]. They also prevent cardiometabolic disorders [

9] and have been shown to maintain better cognitive performance with age [

10].

Over 6000 different classes and subclasses of flavonoids have been identified to date and are primarily synthesized by a variety of plants. Structurally, flavonoids have a 15-carbon skeleton, featuring two benzene rings linked by a three-carbon chain, hence classified as C6-C3-C6 compounds [

11]. Depending on the carbon of the C ring to which the B ring is attached, as well as the degree of oxidation and unsaturation of the C ring, flavonoids can be split into a variety of distinct subgroups: isoflavones in which the B ring is attached to the C ring at position 3, neoflavonoids where the B ring binds to position 4 of the C ring. In addition, typical flavonoids in which the B ring is linked to position 2 of the C ring can be classified into 6 subgroups (based on the structural peculiarities of the C ring) including flavones, flavonols, flavanones, flavanonols, catechins or flavanols, and anthocyanins. Finally, flavonoids with an open C-ring are called chalcones [

5].

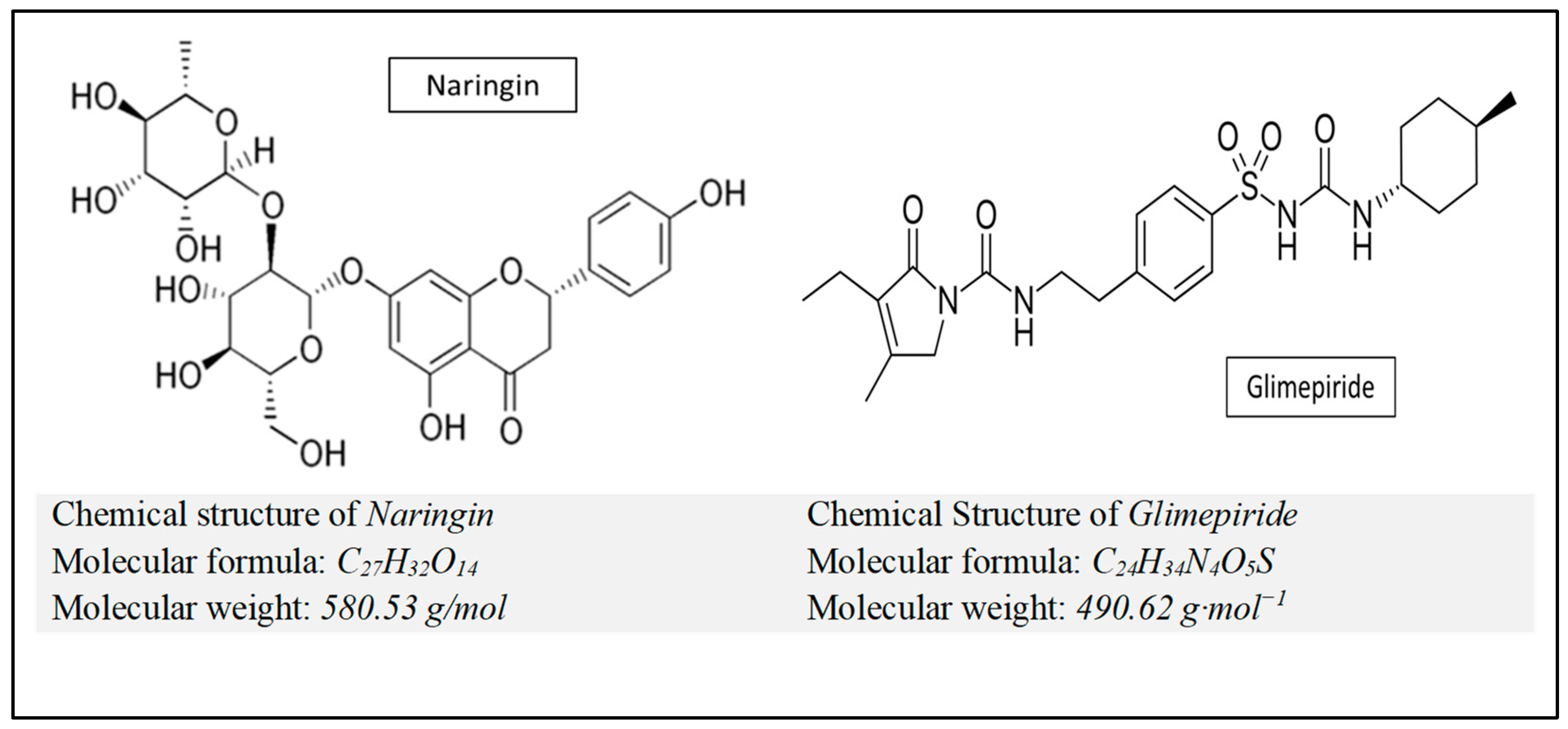

Naringin is a flavanone glycoside, scientifically known as 4’,5,7-trihydroxyflavanone-7-rhamnoglucoside, found in grapes and citrus fruits (the major flavonoid of grapefruit). Many studies have reported several biological effects of naringin such as anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, antiviral, antihypertensive, hepatoprotective, nephroprotective, immunomodulatory, and anticancer activities, but some studies have also shown naringin related side effects and drug interactions [

12].

In accordance with the above, the main objective of the present work was to evaluate and compare the potential antidiabetic, lipid-lowering, anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects of naringin and glimepiride which may alleviate diabetic peripheral sensory neuropathy in rats.

Materials and Methods

The animal experiments were performed in accordance with the guidelines and recommendations of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC), after being approved by the Ethical Review Committee of Damietta Faculty of Medicine, Al-Azhar University, Damietta, Egypt (IRB 00012398, 11 March 2024).

Drugs and Chemicals

Naringin and STZ were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich Chemical Co., Burlington, MA, USA. Glimepiride was obtained from Sanofi-Aventis, Egypt. All other chemicals and reagents utilized in this study were of analytical quality and were purchased commercially at the purest grade available.

Figure 1.

Chemical structure, molecular formula and molecular weight of naringin and glimepiride).

Figure 1.

Chemical structure, molecular formula and molecular weight of naringin and glimepiride).

Animals

Healthy adult male Sprague-Dawley rats (n = 40, aged 9 – 12 weeks, weighing 150 - 180 g) were obtained from the animal house of the National Research Centre (NRC) in Giza, Egypt. The animals were housed in clean polypropylene cages (5 rats/cage) and were kept under standard laboratory conditions: temperature (22 ± 2°C), humidity (30% - 50% RH), and a 12/12 h light/dark cycle. They had free access to water and standard rat chow throughout the adaptation period. Experimental procedures were conducted in the animal house of Damietta Faculty of Medicine, Al-Azhar University, Damietta, Egypt.

Induction of Diabetes and Animal Grouping

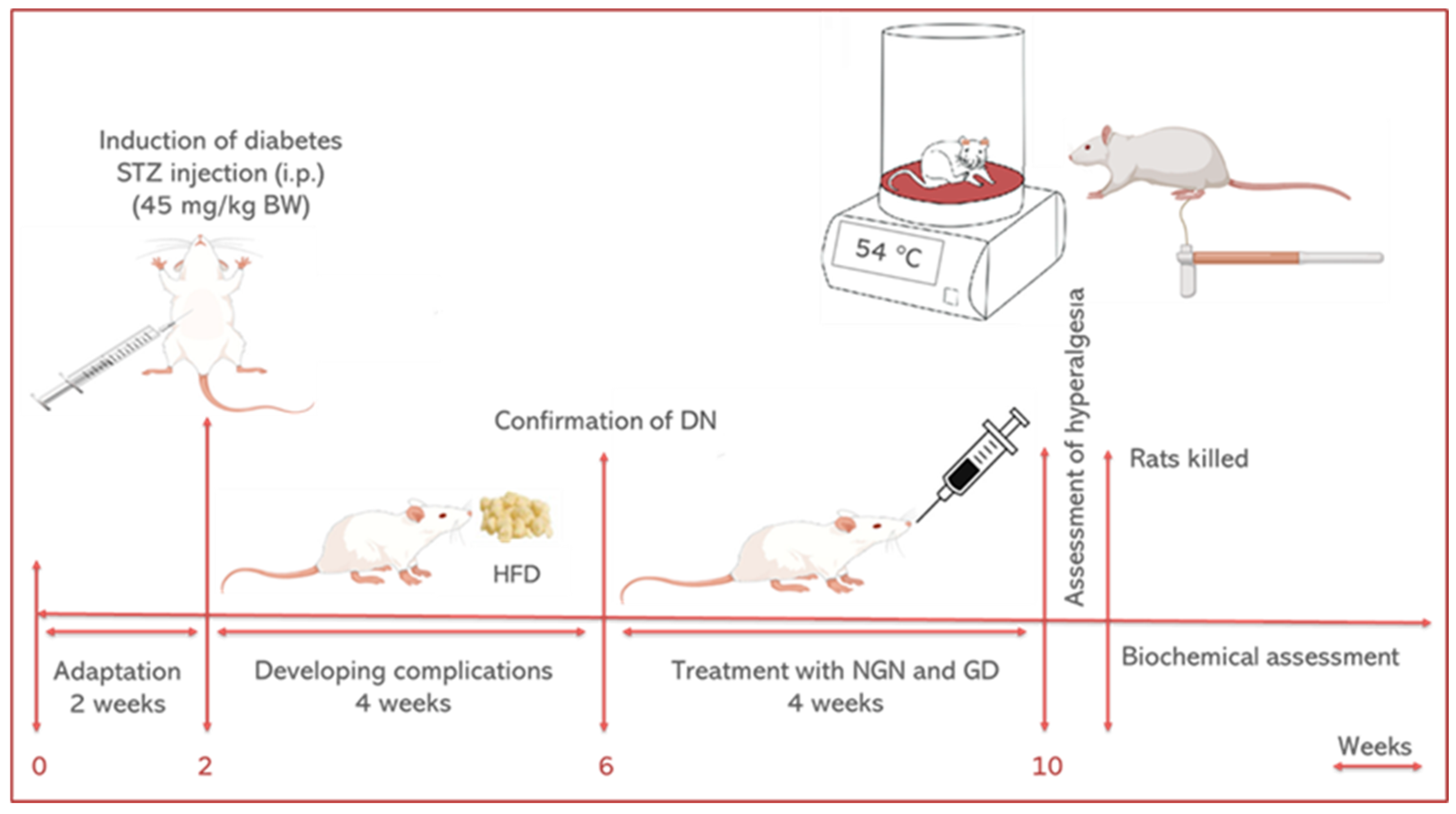

After a two weeks adaptation period, experimental diabetes was induced in 30 rats after 16 hours fast by a single intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection of STZ (45 mg/kg BW) dissolved in citrate buffer (0.1 M, pH 4.5) [

13]. Blood samples were obtained from rat lateral tail veins 36 hours after STZ injection and the fasting blood glucose (FBG) levels were measured by a glucose strip test in a glucometer (Easy Gluco Blood Glucose Monitoring system, Infopia, Korea). Rats with FBG ≥ 250 mg/dl from at least 3 samplings were considered diabetic. Diabetic rats were fed a high-fat diet (HFD) instead of standard rat chow, for 4 weeks until the duration of the experiment to induce diabetic complications such as diabetic neuropathy [

14]. The rats were then divided into four groups as follows:

Group 1: Normal control (NC)- 10 non-diabetic rats received citrate buffer (pH 4.5) and normal drinking water.

Group 2: Diabetic Control (DC)- 10 diabetic rats received normal drinking water.

Group 3: Naringin-treated diabetic rats (NGN-D)- 10 diabetic rats, treated with naringin (100 mg/kg BW/day) by intra-gastric gavage for 4 weeks [

15].

Group 4: Glimepiride-treated diabetic rats (GD-D)- 10 diabetic rats, received glimepiride (0.5 mg/kg BW/day) orally for 4 weeks [

16].

Body weight (BW) was measured at the beginning (initial BW) and end (final BW) of the experiment. The next day after treatment, hyperalgesia was assessed by several behavioral tests, blood samples were collected from retro-orbital veins, and the rats were then lightly anesthetized with ether and killed by decapitation. The animal’s brains were removed, cleared of adhering fat, washed with ice-cold saline, and stored on ice. The animal experiments were approved by the Ethics Committee of Damietta Faculty of Medicine, Al-Azhar University, Damietta, Egypt (IRB 00012398, 11 March 2024).

Figure 2.

Graphical experimental design.

Figure 2.

Graphical experimental design.

Preparation of Plasma, Serum, and Brain Homogenate Samples

For measurement of insulin, TNF-α, and IL-6, plasma was separated by collecting a portion of the blood into heparinized tubes and centrifuging it at 600×g for 15 minutes. While another portion of the blood was centrifuged at 3000×g for 15 minutes to separate the serum for determination of glucose, TG, t-cholesterol, HDL-C, LDL-C, and NO.

On the other hand, the stored brain tissues were washed with ice-cold saline, dried, cut into small pieces and then homogenized in ice-cold buffer (10 mM KH2PO4; 20 mM EDTA; 30 mM KCl). The resulting homogenate was centrifuged at 1000×g for 10 min at 4°C, and the isolated supernatant was used for determination of brain oxidants and antioxidant defense markers.

Biochemical Assay in Serum and Brain Homogenate

Serum glucose, triglycerides (TG), total cholesterol (t-cholesterol), low-density lipoprotein–cholesterol (LDL-C), high density-lipoprotein–cholesterol (HDL-C), proinflammatory cytokine including TNF-α, and IL-6 were measured by enzymatic methods using commercially available kits (RayBiotech), according to the manufacturer’s recommendations.

Oxidative Stress Markers

Brain level of Malondialdehyde (MDA), was measured following the method of Ohkawa et al., [

17] The enzyme activity of superoxide dismutase (SOD) was measured by the conventional technique described by Marklund and Marklund [

18]. Nitric oxide (NO) and Catalase (CAT) enzyme activity were calorimetrically assessed according to Montgomery and Dymock [

19] and Aebi [

20] respectively. Glutathione peroxidase (GPx) enzyme activity was assessed following the method of Paglia and Valentine [

21] and Factor et al., [

22] by measuring NADPH oxidation at 340 nm in the presence of glutathione.

Assessment of Diabetes-Induced Hyperalgesia

Diabetes-induced hyperalgesia was evaluated in the diabetic rats by observing pain thresholds and pain perception using behavioral tests including hot plate, tail immersion, and mechanical sensitivity (von Frey) tests [

23].

In the

hot plate test, rats were placed individually on a hot plate at a temperature of 54 ± 0.1°C, and the latency to front and hind paw licking, rubbing, or jumping to avoid the heat was determined. To avoid tissue damage, a cutting time of 30 seconds was set [

24].

The

tail immersion test was carried out by immersing the rat's tail in a hot water bath maintained at 42 ± 0.5 °C and determining the duration before tail withdrawal (the shortness of which indicates hyperalgesia) [

25].

In

Mechanical sensitivity (von Frey) test, rats were placed individually in mesh-floored boxes and allowed to adapt for 20 minutes. Calibrated von Frey filaments were pressed perpendicularly on the plantar surface of the hind paw with a sufficient force to bend the filament for 6 seconds. With animals that didn’t give a response, filaments of the next-greater force were applied, while in presence of a response, filaments of the next-lower force were used. Each animal was tested 4 to 5 times at 5 minutes intervals, and the mean values were used [

26].

Statistical Analysis

The results were analyzed for statistical significance by Statistical Packages for Social Science (SPSS) program (release 7.5.1 SPSS Inc, Chicago, Illinois, 1996). Quantitative data were expressed as means ± SEM of 10 animals/group. A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used when comparing between more than two means and Post Hoc test (Tukey's test) was used for multiple comparisons between different variables. Differences between groups were considered significant at P ≤ 0.05.

Results

Effect of Treatment on Body Weight and Glycemic Status of Diabetic Rats

As shown in

Table 1, there were no statistically significant differences (p > 0.05) in the body weight (BW) between the studied groups at the beginning of the experiment. While at the end of the experiment, diabetic rats showed a decrease in the final BW, with a significantly reduced weight gain (P < 0.01) compared to the normal control (NC) rats. Treatment with naringin or glimepiride resulted in significant weight gain and recovery of the reduced BW compared with the diabetic control (DC) rats (p < 0.01).

Table 1 also shows that naringin and glimepiride significantly modulate the glycemic status of diabetic rats by decreasing plasma glucose and increasing insulin levels compared with DC rats (P < 0.01).

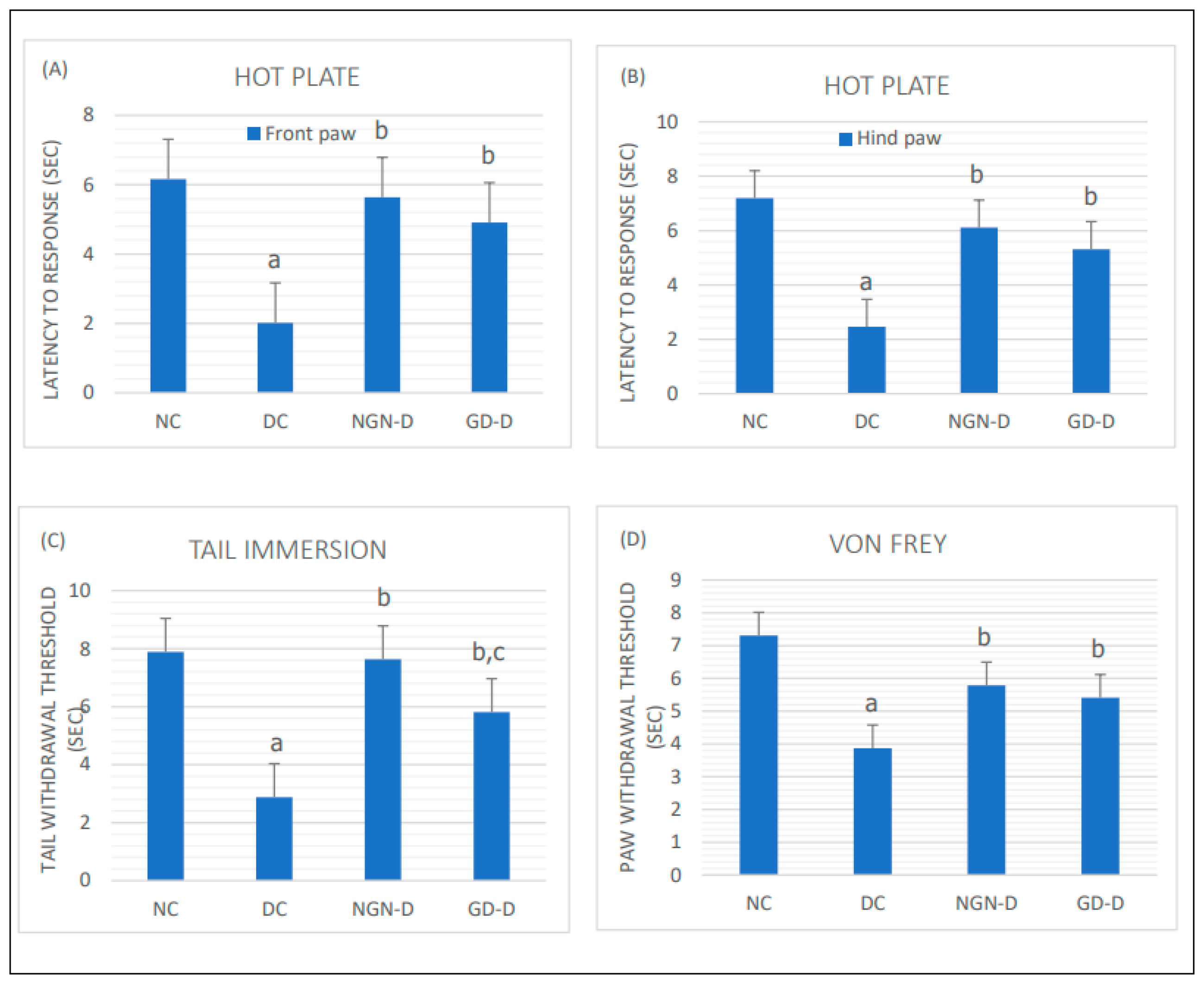

Effect of Treatment on Pain Threshold

The results of hot-plate and tail-immersion tests revealed a significantly decreased pain threshold in diabetic rats as compared with the NC rats (p < 0.01). Both tests revealed a significant increase in nociceptive threshold in both naringin-treated and glimepiride-treated diabetic rats as compared to untreated DC rats (p < 0.01), with a more pronounced response in the tail-immersion test to naringin compared to glimepiride (p < 0.05) (

Figure 3).

Also, the results of the mechanical sensitivity (von Frey) test revealed a significant reduction in the tactile withdrawal threshold in DC rats compared with the normal controls (p < 0.01), which is significantly corrected when diabetic rats were treated with either naringin, or glimepiride (

Figure 3).

Naringin or glimepiride significantly increased response latency in hot plate test and tail immersion tests, and tactile withdrawal threshold in von Frey test, more significantly for naringin than for glimepiride.

Effect of Treatment on Lipid Profile and Inflammatory Cytokines in Diabetic Rats

As shown in

Table 2, diabetic rats reported significantly higher levels of NO, TG, t-cholesterol, LDL-C, TNF-α, and IL-6 with a significant reduction in HLD-C compared with the NC rats. Interestingly, the naringin and glimepiride-treated diabetic groups experienced ameliorated alterations in NO, serum lipids, as well as plasma IL-6 and TNF-α with almost the same degree of efficacy for all observed parameters except for the proinflammatory cytokines, where the anti-inflammatory effect of naringin was more pronounced than that of glimepiride (p < 0.05).

Effect of Treatment on Brain Oxidants and Antioxidant Defense Markers

Table 3 shows the effect of treatment with naringin and glimepiride on brain oxidants and antioxidant defense markers in diabetic rats, where the DC rats had a significant increase in brain content of MDA, with a significant decrease in brain GSH, GPx, SOD, and CAT compared to the NC group. Conversely, the naringin-treated and glimepiride-treated diabetic rats exhibited almost normalized brain content of MDA, GSH, GPx, SOD, and CAT.

Discussion

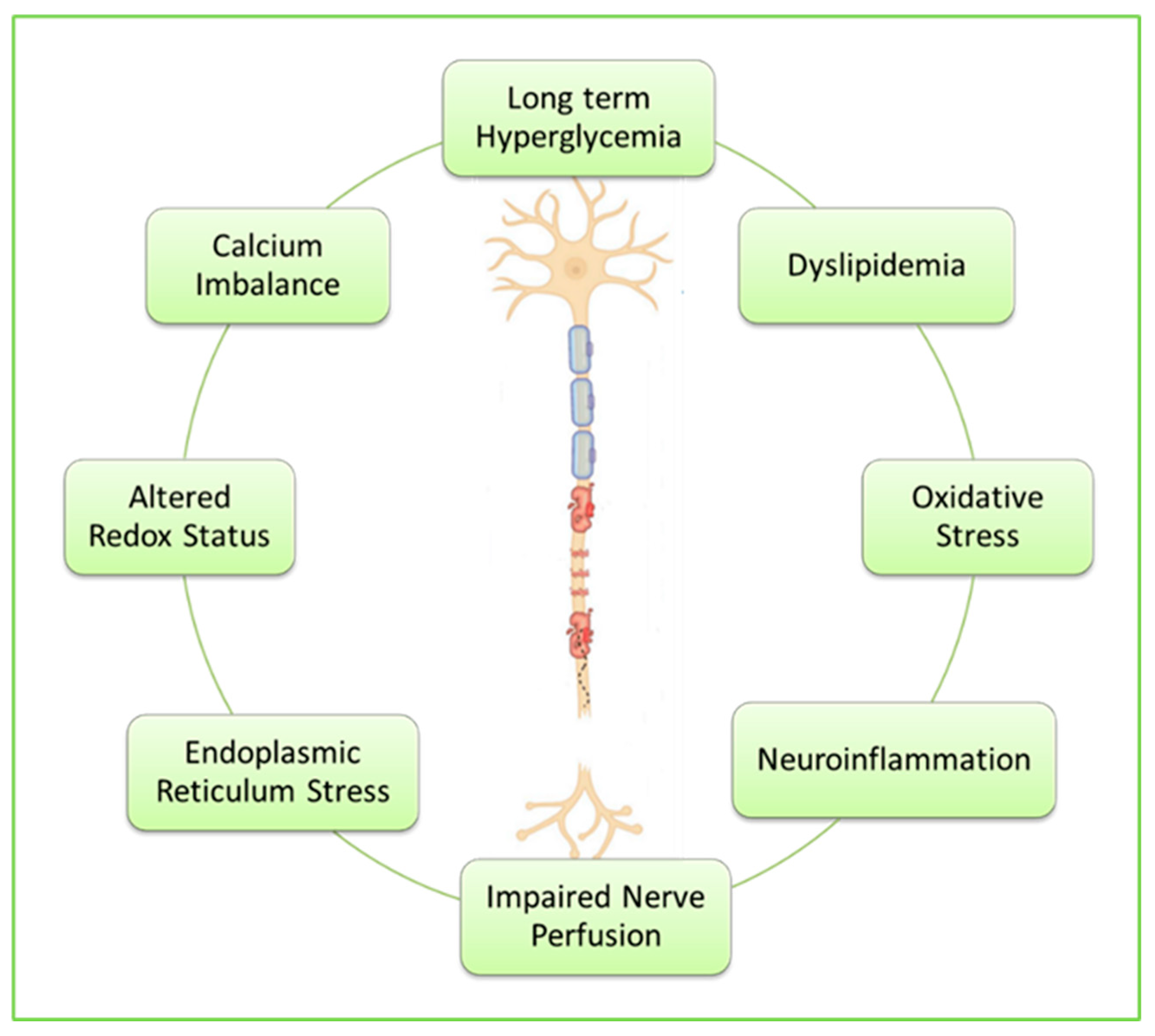

Diabetic neuropathy is difficult to study because of the complex multiple causes of diabetic nerve damage including long-term hyperglycemia, dyslipidemia, inflammation, oxidative stress, growth factor deficiency, and accumulation of advanced glycation end products (AGEs) due to exposure of protein and fat to sugars [

27].

The precise mechanisms underlying the STZ diabetes-induced neurodegeneration are also complex and multifactorial, most notably increased production of free radicals due to oxidative stress to which nerve cells are particularly vulnerable due to their greater reliance on oxidative phosphorylation as compared with other cells [

28]. Hyperglycemia also causes endoplasmic reticulum stress, leading to various neuronal apoptotic processes [

29]. Additional mechanisms include dyslipidemia, impaired nerve perfusion, disrupted redox status, chronic low-grade neuroinflammation, and disturbed calcium homeostasis [

30].

Figure 4.

Key mechanisms underlying diabetes-induced neurodegeneration.

Figure 4.

Key mechanisms underlying diabetes-induced neurodegeneration.

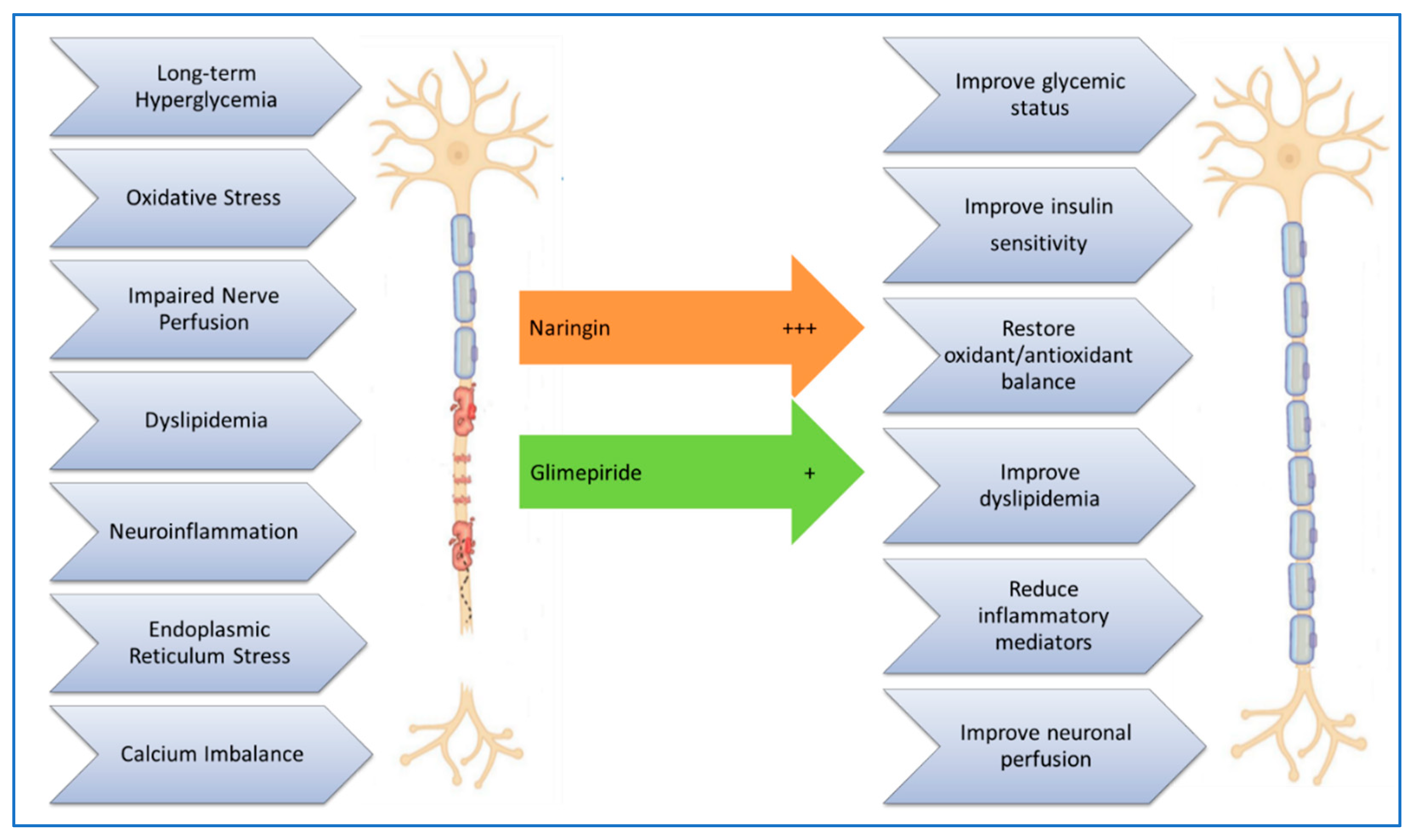

In the present study we investigated the neuroprotective properties of naringin (a citrus flavonoid) and glimepiride (a standard antidiabetic drug) on STZ-induced peripheral diabetic neuropathy in rats by investigating and comparing their hypoglycemic, hypolipidemic, antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects.

The results showed marked increase in serum levels of blood glucose, TG, t-cholesterol, LDL-C, and NO with a concomitant decrease in HDL-C and BW secondary to induction of diabetes in rats. Diabetic rats also showed a significant decrease in brain antioxidants (GSH, GPx, SOD, and CAT) with a concomitant increase in brain MDA. Furthermore, diabetic rats showed a significant decrease in plasma insulin levels while the levels of inflammatory cytokines (IL-6 and TNF-α) were significantly increased. These results align with other studies that have observed increased serum levels of blood glucose, TG, t-cholesterol, and LDL-C, accompanied with a decreased serum HDL-C, elevated brain MDA, and reduced brain antioxidant enzyme activities, as well as significantly increased plasma levels of IL-6 and TNF-α, with significantly decreased plasma insulin levels in diabetic rats [

23,

31,

33].

In this study, treatment of diabetic rats with naringin or glimepiride resulted in significant weight gain and nearly normalized plasma glucose and insulin levels. These results are consistent with previous studies showing that naringin can improve insulin sensitivity and reduce blood glucose levels by modulating key enzymes involved in glucose metabolism [

34,

35,

36].

Results of the current study also demonstrated that naringin or glimepiride reduced pain hypersensitivity and improved hyperalgesia in diabetic rats, as evidenced by increased response latency in hot plate and tail immersion tests, and tactile withdrawal threshold in von Frey test, with naringin showing a more pronounced effect in the tail-immersion test suggesting its stronger anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties [

37]. This is supported by other research suggesting that naringin can reduce neuroinflammation and oxidative stress, which are key contributors to neuropathic pain [

14]. These results are also similar to previous studies that observed a reduced pain threshold in animals after diabetes induction and a dose-dependent improvement after treatment with naringin [

38,

39].

Elevated levels of TG, t-cholesterol, and LDL-C, along with reduced HDL-C, are common in diabetes and contribute to cardiovascular risk. Proinflammatory cytokines have often been linked to the induction of neuropathic pain, increased excitability of afferent sensory nerves, demyelination and altered permeability of the blood-nerve barrier leading to peripheral neuronal degeneration [

40,

41]. Our study showed that naringin or glimepiride significantly improved the lipid profile and reduced inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α and IL-6) in diabetic rats, with naringin showing a more pronounced anti-inflammatory effect. This highlights their role in alleviating diabetic dyslipidemia and inflammation, which are critical factors in the development of diabetic complications. These results are in line with the observation that naringin reduces hypercholesteremia in rats fed a HFD by inhibiting the enzyme 3-hydroxy-3-methyl-glutaryl-coenzyme A reductase (HMG-CoA reductase) resulting in lower plasma LDL-C and TG levels, without impacting HDL-C levels [

42]. Hu and Zhao [

43], Tsai et al. [

44] and Bai et al. [

45] also observed that chronic treatment of diabetic rats with naringin, significantly inhibited production and release of these inflammatory mediators.

Oxidative stress plays a central role in the pathogenesis of diabetes and its complications. Our study found that diabetic rats exhibited increased levels of MDA and decreased brain levels of GSH, GPx, SOD, and CAT. Treatment with naringin or glimepiride attenuated oxidative stress and improved antioxidant capacity in the brains of diabetic rats, indicating their potential to protect against oxidative damage. This is consistent with other studies showing that naringin has strong antioxidant properties via decreasing lipid peroxidation and buildup of reactive oxygen species (ROS) [

46], lowering SOD, GSH, GPx, and CAT activities [

47].

Comparative Efficacy

While both naringin and glimepiride demonstrated positive effects in managing diabetes and its complications, naringin appeared to have a more pronounced impact on reducing neuroinflammation and oxidative stress. This indicates that naringin could be a more effective treatment option, especially for diabetic neuropathy. The study's findings are supported by other research showing that naringin can modulate various biochemical pathways involved in glucose and lipid metabolism, inflammation, and oxidative stress [

48].

Figure 5.

Scheme summarizing some of the molecular mechanisms of diabetes-induced neuronal damage, and how treatment with naringin or glimepiride improves it.

Figure 5.

Scheme summarizing some of the molecular mechanisms of diabetes-induced neuronal damage, and how treatment with naringin or glimepiride improves it.

Conclusion

In summary, the study highlights the therapeutic potential of both naringin and glimepiride in managing diabetes and its complications. Both compounds were effective in improving body weight, glycemic status, pain sensitivity, lipid profile, neuroinflammation, and oxidative stress in diabetic rats. Notably, naringin exhibited more significant anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects. These findings suggest that naringin could be a valuable addition to diabetes treatment, offering benefits beyond glycemic control, such as protection against neuropathy, dyslipidemia, and oxidative damage. A limitation of this study is that we didn’t thoroughly investigate all the molecular mechanisms of naringin’s mitigating effects in diabetic neuropathy, more in-depth research on its detailed mechanisms of action is needed.

Author contributions

Osama M. Mehanna, Basem H. Elesawy and Ahmad El Askary conceived and designed this study. All authors provided the materials. Mohamed Gaber Mohamed Hassan, Walid Mostafa Sayed Ahmed, Mohamed Ramadan Abd El Aziz Elnady, Mustafa Muhammad Alqulaly, Mohamed Awad Shahien, Soha S. Nosier and Ahmed Hamed Bedair El-Assal performed the experiments, analyzed and interpreted the data. Osama M. Mehanna provided great help for the laboratory technique, experiments, and data analysis. Osama M. Mehanna, Ahmad S. Abd El Monsef, Mohamed Ali Mahmoud Elmoghazy, Ahmed I. Sharahili and Mohamed Mansour Khalifa wrote the final draft of the article. Osama M. Mehanna, Basem H. Elesawy and Ahmad El Askary revised the final draft of the written article. All authors have read and approved the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The animal study protocol was approved by the Ethical Review Committee of Damietta Faculty of Medicine- Al Azhar University, Damietta, Egypt (IRB 00012398, 11 March 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Exclude this statement

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Deanship of Graduate Studies and Scientific Research, Taif University for funding this work.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- Banday MZ, Sameer AS, Nissar S. Pathophysiology of diabetes: An overview. Avicenna J Med. 2020, 10, 174–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Chawla, A. , Chawla, R., and Jaggi, S. Microvascular and macrovascular complications in diabetes mellitus: distinct or continuum? Indian Journal of Endocrinology and Metabolism 2016, 20, 546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palpagama TH, Waldvogel HJ, Faull RLM, Kwakowsky A. The Role of Microglia and Astrocytes in Huntington's Disease. Front Mol Neurosci. 2019, 12, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Said, G. Diabetic neuropathy--a review. Nat Clin Pract Neurol. 2007, 3, 331–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panche, A. N. , Diwan, A. D., and Chandra, S. R. Flavonoids: an overview. Journal of Nutritional Science 2016, 5, e47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danihelová, M. , Viskupičová J., Šturdík E. Lipophilization of flavonoids for their food, therapeutic and cosmetic applications. Acta Chim. Slovaca. 2012, 5, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villela, A. , van Vuuren M.S., Willemen H.M., Derksen G.C., van Beek T.A. Photo-stability of a flavonoid dye in presence of aluminum ions. Dyes Pigment. 2019, 162, 222–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Z. , Wang J., Chen Z., Ma Q., Guo Q., Gao X., Chen H. Antioxidant, antihypertensive, and anticancer activities of the flavonoid fractions from green, oolong, and black tea infusion waste. J. Food Biochem. 2018, 42, e12690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazidi, M. , Katsiki N., Banach M. A higher flavonoid intake is associated with less likelihood of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: Results from a multiethnic study. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2019, 65, 66–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguiar, L.M. , Geraldi M.V., Cazarin C.B.B., Junior M.R.M. Functional Food Consumption and Its Physiological Effects. In Bioactive Compounds; Campos M.R.S., Ed.; Woodhead Publishing; Sawston, UK, 2019; pp. 205–225.

- Nabavi, S.M. , Samec D., Tomczyk M., Milella L., Russo D., Habtemariam S., Suntar I., Rastrelli L., Daglia M., Xiao J., et al. Flavonoid biosynthetic pathways in plants: Versatile targets for metabolic engineering. Biotechnol. Adv. [CrossRef]

- Zeng X, Su W, Zheng Y, et al. Pharmacokinetics, Tissue Distribution, Metabolism, and Excretion of Naringin in Aged Rats. Front Pharmacol. 2019, 10, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito M, Kondo Y, Nakatani A, Hayashi K, Naruse A. Characterization of low dose streptozotocin-induced progressive diabetes in mice. Environ Toxicol Pharmacol. 2001, 9, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmad, M.F.; Naseem, N.; Rahman, I.; Imam, N.; Younus, H.; Pandey, S.K.; Siddiqui, W.A. Naringin Attenuates the Diabetic Neuropathy in STZ-Induced Type 2 Diabetic Wistar Rats. Life 2022, 12, 2111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pengnet S, Sumarithum P, Phongnu N, Prommaouan S, Kantip N, Phoungpetchara I, Malakul W. Naringin attenuates fructose-induced NAFLD progression in rats through reducing endogenous triglyceride synthesis and activating the Nrf2/HO-1 pathway. Front Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 1049818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- A. Salama and N. N. Yassen. A cytoprotectant effect of morus alba against streptozotocin-induced diabetic damage in rat brains. Der Pharma Chemica 2017, 9, 24–30. [Google Scholar]

- H. Ohkawa, N. Ohishi, K. Yagi, Anal. Biochem. 1979, 95, 351. [Google Scholar]

- Marklund, S.; Marklund, G. Involvement of the superoxide anion radical in the autoxidation of pyrogallol and a convenient assay for superoxide dismutase. Eur. J. Biochem. 1974, 47, 469–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- H. A. Montgomery. J. Dymock, Analyst 1961, 86, 414. [Google Scholar]

- Aebi. Methods Enzymol. 1984, 105, 121. [CrossRef]

- D. E. Paglia, W. N. Valentine, J. Lab. Clin. Med. 1967, 70, 158. [Google Scholar]

- V. M. Factor, A. Kiss, J. T. Woitach, P. J. Wirth, S. S. Thorgeirsson, J. Biol. Chem. 1998, 273, 15846. [Google Scholar]

- Bilkei-Gorzo, O. M. Abo-Salem, A.M. Hayallah, K.Michel, C. E. Müller, A. Zimmer, Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 2008, 77, 65. [Google Scholar]

- Abo-Salem OM, Ali TM, Harisa GI, Mehanna OM, Younos IH, Almalki WH. Beneficial effects of (−)-epigallocatechin-3-O-gallate on diabetic peripheral neuropathy in the rat model. J Biochem Mol Toxicol. 2508. [CrossRef]

- S. A. Kanaan, N. E. Saade, J. J. Haddad, A. M. Abdel Noor, S. F. Atweh, S. J. Jabbur and B. Safieh-Garabedian, Endotoxin-induced local inflammation and hyperalgesia in rats and mice: a new model for inflammatory pain. Pain 1996, 66, 373–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh P, Bansal S, Kuhad A, Kumar A, Chopra K. Naringenin ameliorates diabetic neuropathic pain by modulation of oxidative-nitrosative stress, cytokines and MMP-9 levels. Food Funct. 2020, 11, 4548–4560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang HL, Zhang GY, Dai WX, Shu LP, Wei QF, Zheng RF, Lin CX. Dose-dependent neurotoxicity caused by the addition of perineural dexmedetomidine to ropivacaine for continuous femoral nerve block in rabbits. J Int Med Res. 2019, 47, 2562–2570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sangi, S. M. A. , and Jalaud, N. A. A. Prevention and treatment of brain damage in streptozotocin induced diabetic rats with Metformin, Nigella sativa, Zingiber officinale, and Punica granatum. Biomedical Research and Therapy 2019, 6, 3274–3285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abo-Salem OM, Harisa GI, Ali TM, El-Sayed el-SM, Abou-Elnour FM. Curcumin ameliorates streptozotocin-induced heart injury in rats. J Biochem Mol Toxicol. 2014, 28, 263–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roghani M, Baluchnejadmojarad T. Hypoglycemic and hypolipidemic effect and antioxidant activity of chronic epigallocatechin-gallate in streptozotocin-diabetic rats. Pathophysiology. 2010, 17, 55–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X. , Guo, C., & Kong, J. Oxidative stress in neurodegenerative diseases. Neural regeneration research 2012, 7, 376–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman, E. L. , Nave, K. A., Jensen, T. S., and Bennett, D. L. H. New Horizons in Diabetic Neuropathy: Mechanisms, Bioenergetics, and Pain. Neuron 2017, 93, 1296–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albers JW, and Pop-Busui R. Diabetic neuropathy: mechanisms, emerging treatments, and subtypes. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2014, 14, 473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Okesina, K.B. , Odetayo, A.F., Adeyemi, W.J. et al. Naringin Prevents Diabetic-Induced Dysmetabolism in Male Wistar Rats by Modulating GSK-3 Activities and Oxidative Stress-Dependent Pathways. Cell Biochem Biophys 2024, 82, 3559–3571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barajas-Vega JL, Raffoul-Orozco AK, Hernandez-Molina D, et al. Naringin reduces body weight, plasma lipids and increases adiponectin levels in patients with dyslipidemia. Int J Vitam Nutr Res. 2022, 92, 292–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam MA, Subhan N, Rahman MM, Uddin SJ, Reza HM, Sarker SD. Effect of citrus flavonoids, naringin and naringenin, on metabolic syndrome and their mechanisms of action. Adv Nutr. 2014, 5, 404–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osama Mohamed Ahmed and Ayman Moawad Mahmoud and Adel Abdel-Moneim and Mohamed B Ashour “Antidiabetic effects of hesperidin and naringin in type 2 diabetic rats.” (2012). https://api.semanticscholar. 3903.

- Kandhare, A.D.; Raygude, K.S.; Ghosh, P.; Ghule, A.E.; Bodhankar, S.L. Neuroprotective effect of naringin by modulation of endogenous biomarkers in streptozotocin induced painful diabetic neuropathy. Fitoterapia 2012, 83, 650–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vij, N.; Mazur, S.; Zeitlin, P.L. CFTR Is a Negative Regulator of NFκB Mediated Innate Immune Response. PLoS ONE 2009, 4, e4664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, H.Y.; Kim, S.H.; Jeong, H.J.; Kim, S.Y.; Shin, T.Y.; Um, J.Y.; Kim, H.M. Epigallocatechin-3-gallate inhibits secretion of TNF-α, IL-6 and IL-8 through the attenuation of ERK and NF-κB in HMC-1 cells. Int. Arch. Allergy Immunol. 2007, 142, 335–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chertoff, M.; Di Paolo, N.; Schoeneberg, A.; Depino, A.; Ferrari, C.; Wurst, W.; Pfizenmaier, K.; Eisel, U.; Pitossi, F. Neuroprotective and neurodegenerative effects of the chronic expression of tumor necrosis factor alpha in the nigrostriatal dopaminergic circuit of adult mice. Exp. Neurol. 2011, 227, 237–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baskaran, G.; Salvamani, S.; Ahmad, S.A.; Shaharuddin, N.A.; Pattiram, P.D.; Shukor, M.Y. HMG-CoA reductase inhibitory activity and phytocomponent investigation of Basella alba leaf extract as a treatment for hypercholesterolemia. Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 2015, 9, 509–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- C. Y. Hu and Y. T. Zhao, Analgesic effects of naringenin in rats with spinal nerve ligation-induced neuropathic pain. Biomed. Rep. 2014, 2, 569–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. J. Tsai, C. S. Huang, M. C. Mong, W. Y. Kam, H. Y. Huang and M. C. Yin, Anti-inflammatory and antifibrotic effects of naringenin in diabetic mice. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2012, 60, 514–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- X. Bai, X. Zhang, L. Chen, J. Zhang, L. Zhang, X. Zhao, T. Zhao and Y. Zhao, Protective Effect of Naringenin in Experimental Ischemic Stroke: Down-Regulated NOD2, nitric oxide synthase and cyclooxygenase-2 expression in macrophages than in microglia. Nutr. Res. 2010, 300, 858–864. [Google Scholar]

- A Bakheet S, M Attia S. Evaluation of chromosomal instability in diabetic rats treated with naringin. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2011, 2011, 365292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, A.M.; Ashour, M.B.; Abdel-Moneim, A.; Ahmed, O.M. Hesperidin and naringin attenuate hyperglycemia-mediated oxidative stress and proinflammatory cytokine production in high fat fed/streptozotocin-induced type 2 diabetic rats. J. Diabetes Complicat. 2012, 26, 483–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oyindamola, O. A, Adewale G. B, Christiana T. A, Adebola I. K, Tolulope A. O, Tejumade S. U. Naringin ameliorates cognitive impairment in streptozotocin/nicotinamide induced type 2 diabetes in Wistar rats. Physiology and Pharmacology 2022, 26, 20–29. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).