Submitted:

27 January 2025

Posted:

28 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

Related Work

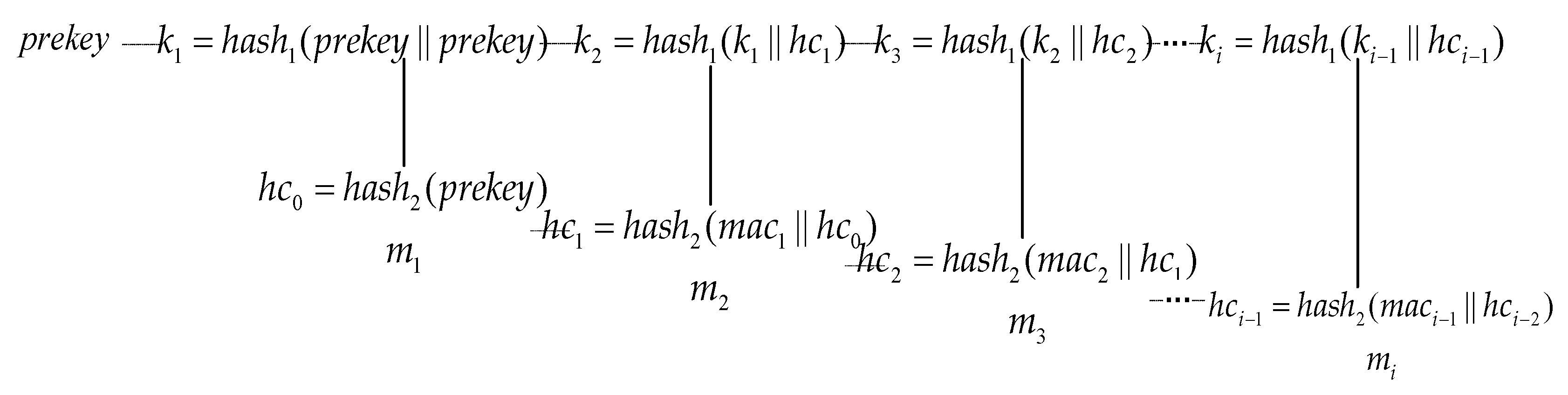

2.1. Message Hash Chain

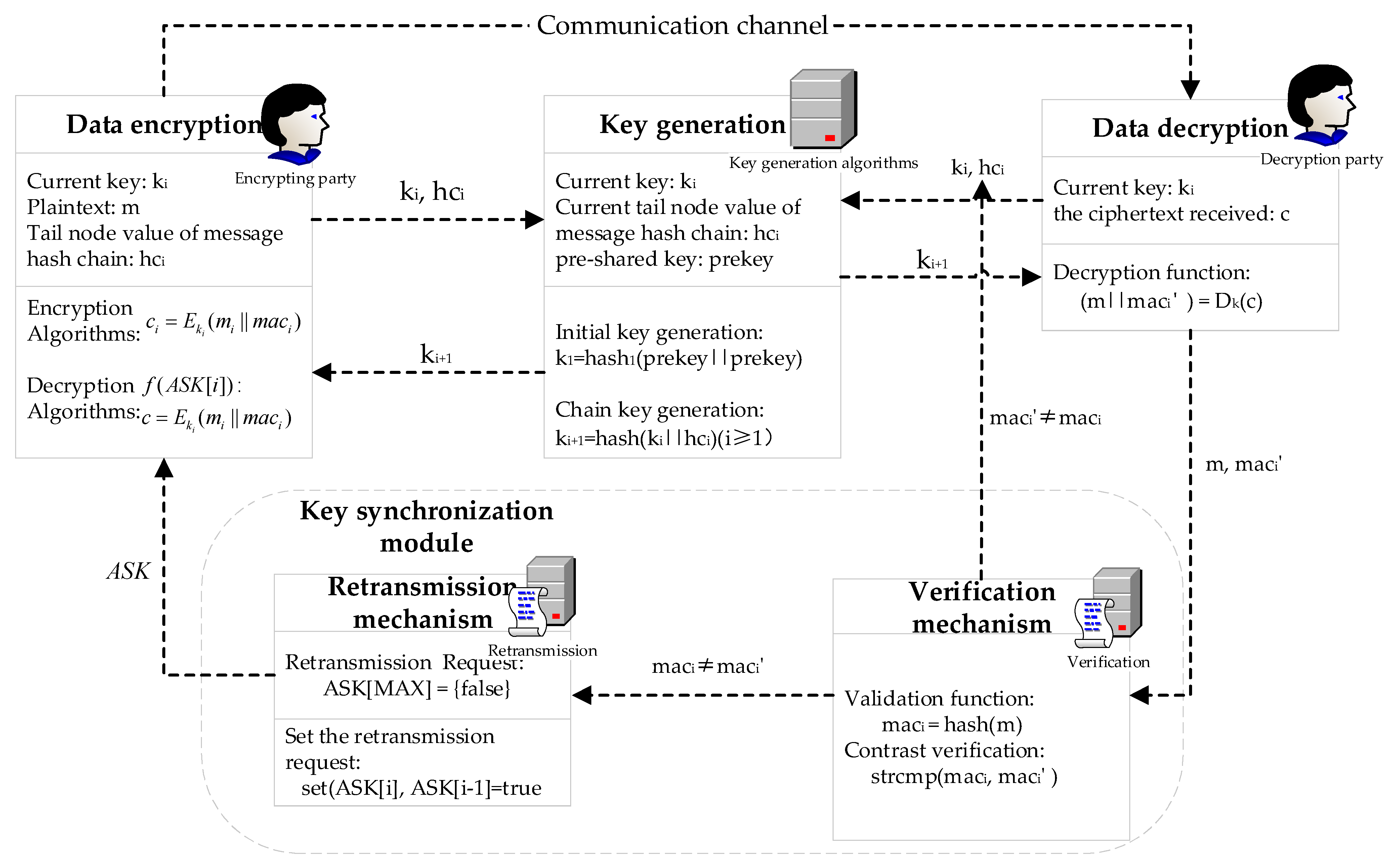

3. Chain Key Model

3.1. Symbol Description

- If , then .

- If, then , and the decryption satisfies .

- If , the verification is successful, and the plaintext is consideres valid.

- If , the verification fails, and an error message is returned (e.g., "MAC verification failed").

3.2. Specific Process

3.3.1. Sender Procedure

| Algorithm 1. Sender Process |

| Input: pre-shared key , message , plaintext hash value Output: ciphertext |

| 1. |

| 2. |

| 3. |

| 4. |

| 5. |

| 6. |

| 7. |

| 8. |

| 9. |

| 10. |

| 11. |

| 12. |

3.3.2. Receiver Process

| Algorithm2. Receiver Process |

| Input: pre-shared key , ciphertext , key Output: message |

| 1. |

| 2. |

| 3. |

| 4. |

| 5. |

| 6. |

| 7. |

| 8. |

| 9. |

| 10. |

| 11. |

| 12. |

| 13. |

| 14. |

| 15. |

3.2. Chain key and Self-Synchronizing Stream Cipher

4. Salsa Stream Cipher Optimization Based on Chain Key

5. Security Analysis

5.1. Symbol Description

- The one-wayness of the hash function : An attacker cannot infer prekey from .

-

The confidentiality of the pre-shared key prekey : An attacker cannot directly access prekey .Thus, the security of is determined by the one-wayness of the hash function, as well as the confidentiality of prekey .

- The one-wayness of the hash function

- The unpredictability of the plaintext sequence

- The confidentiality of the pre-shared key prekey .

- The one-wayness of the hash functions and .

- The unpredictability of the plaintext sequence

- The confidentiality of the pre-shared key prekey .

5.1. Key Extensibility Security

5.1. Security Analysis of Salsa Stream Cipher Based on Chain Key

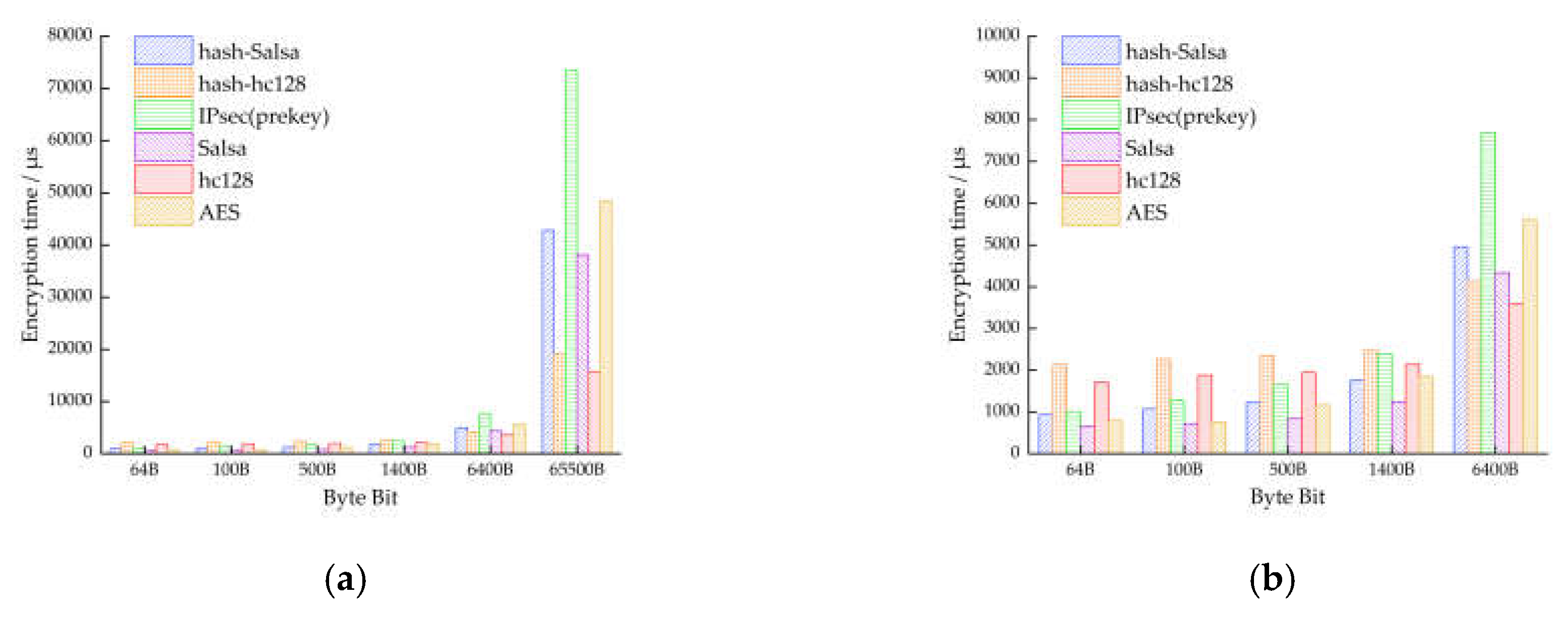

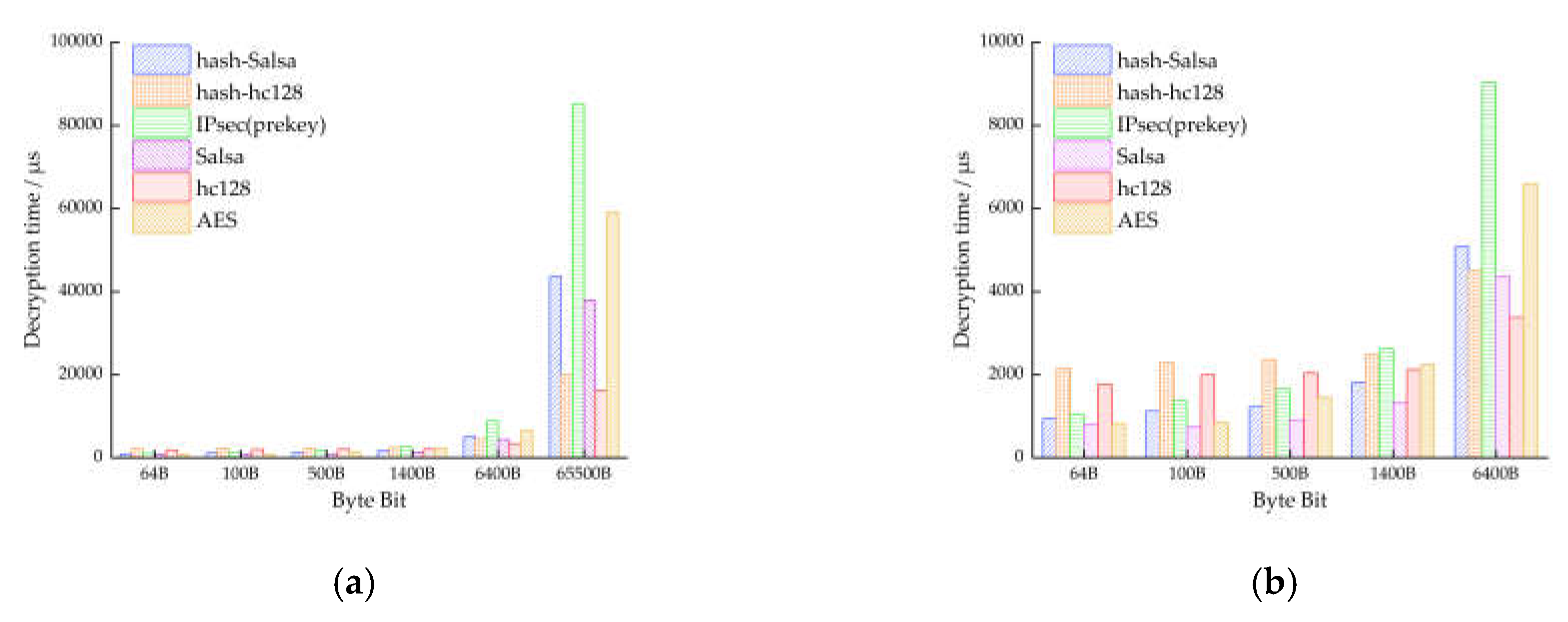

6. Experimental Analysis

6.1. Chain key Experiment Analysis

6.1.1. Chain key Generation Efficiency

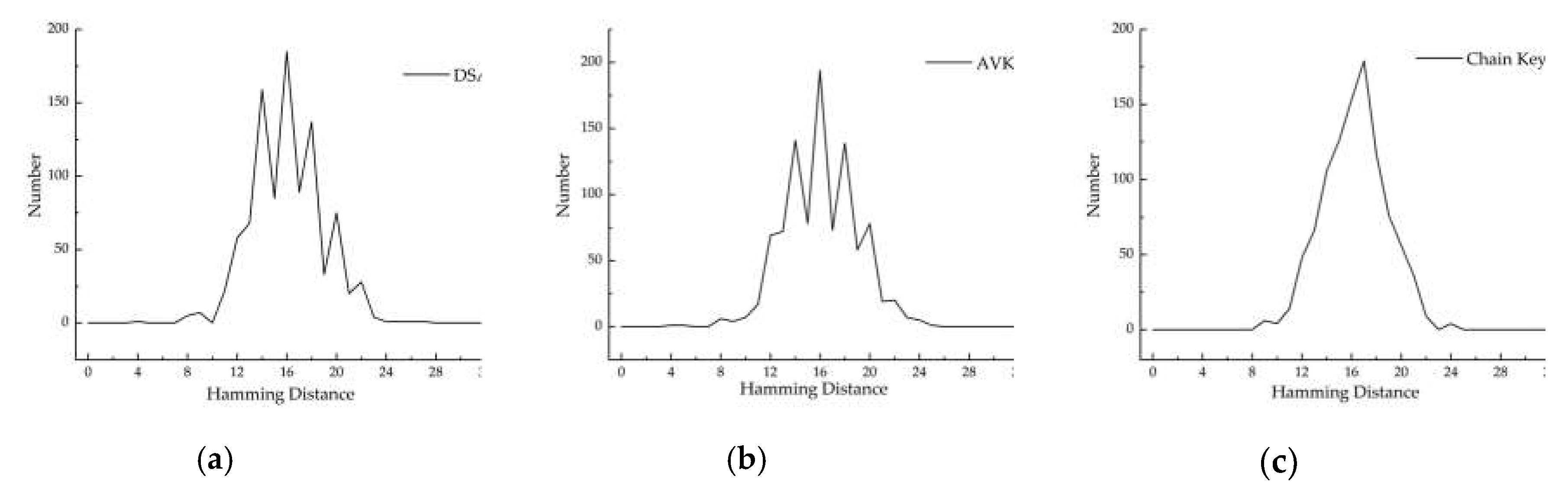

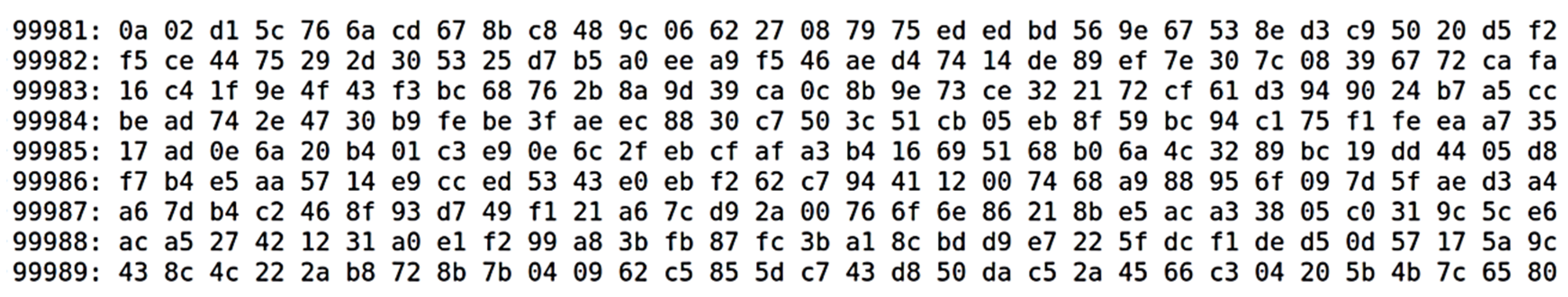

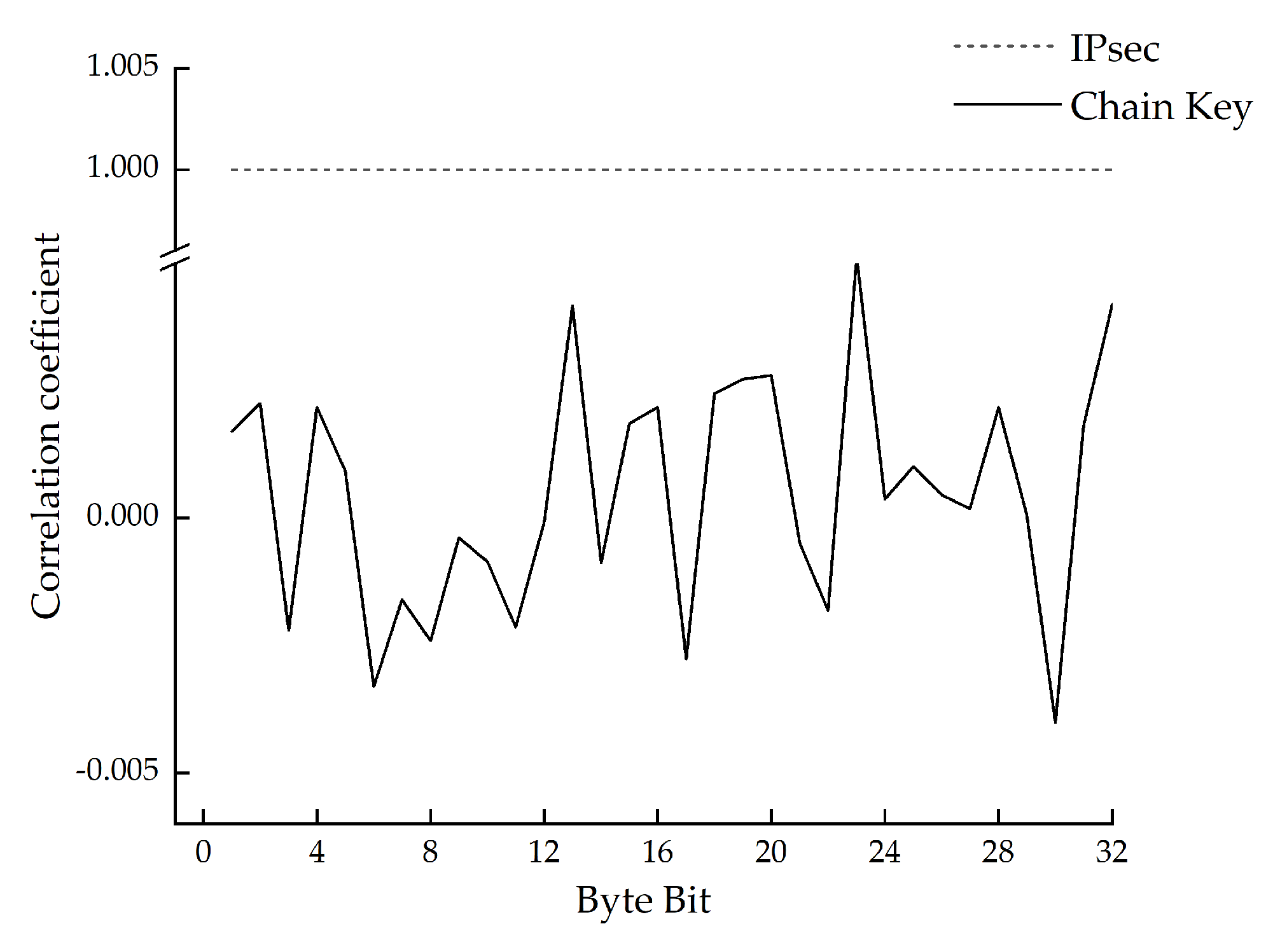

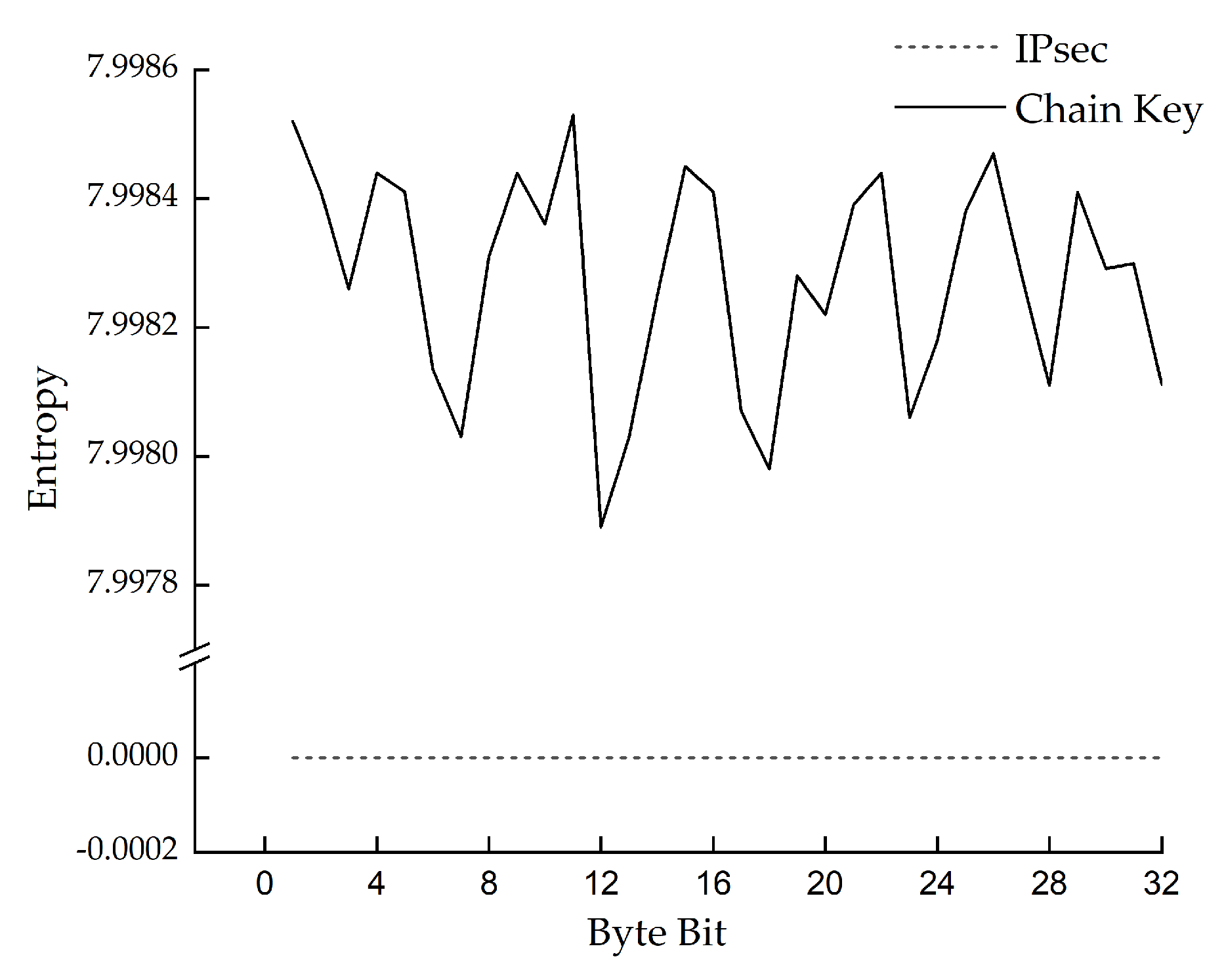

6.1.3. Chain key Randomness Test

6.1. Analysis of Salsa Stream Cipher Based on Chain key

7. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

References

- Ghanem, K.; Ugwuanyi, S.; Hansawangkit; J.McPherson, R.; Khan, R.; Irvine, J. Security vs bandwidth: performance analysis between IPsec and OpenVPN in smart grid. In 2022 International Symposium on Networks, Computers and Communications (ISNCC), 2022,pp. 1-5. IEEE.

- Shannon, C. E. Communication theory of secrecy systems[J]. The Bell system technical journal, 1949, 28(4): 656-715.

- WANG,J.B.; ZHANG,W.Z. Provably-Secure Randomized Block Cipher Approaching to Perfect Secrecy[J]. Journal of Cryptologic Research,2021,8(5):808-819.

- AI,X.; WU, M. D.; WU, X. D.; Design of one-time pad SM4 algorithm[J]. Cyberspace Security, 2018, 9(2): 20–23.

- ZHANG, Y.J.; MA, J.M.; WEI, Y.Y. Self-synchronizing sequence cipher algorithm based on block encrypting synchronization information[J], Journal of Computer Applications, 2016, 36(S1): 42–45.

- Prajapat, S.; Porwal, A.; Jaiswal, S.; Saifee, F.; Thakur, R. S. Generalized Parametric Model for AVK-Based Cryptosystem. In Networking Communication and Data Knowledge Engineering:2018, Volume 2,pp. 217-227. Springer Singapore.

- Francq, J.; Besson, L.;Huynh, P.;Guillot, P.; Millerioux, G.; Minier, M. Non-triangular self-synchronizing stream ciphers. IEEE Transactions on Computers, 2020,71(1), 134-145. [CrossRef]

- LIU,H.F.; CAO,Y.M.; LIANG, X.L. Improved DES Based On Stream Cipher[J], Computer Applications and Software,2019,36(9). 317–320.

- Chakrabarti P, Bhuyan B, Chowdhuri A, et al. A novel approach towards realizing optimum data transfer and Automatic Variable Key (AVK) in cryptography[J]. IJCSNS, 2008, 8(5): 241.

- Goswami R S, Chakraborty S K, Bhunia A, et al. New techniques for generating of automatic variable key in achieving perfect security[J]. Journal of the Institution of Engineers (India): Series B, 2014, 95: 197-201.

- Goswami R S, Chakraborty S K, Bhunia A, et al. New approach towards generation of automatic variable key to achieve perfect security[C]//2013 10th International Conference on information technology: new generations. IEEE, 2013: 489-491.

- Singh B K, Banerjee S, Dutta M P, et al. Generation of automatic variable key to make secure communication[C]//Proceedings of the International Conference on Recent Cognizance in Wireless Communication & Image Processing: ICRCWIP-2014. Springer India, 2016: 317-323.

- Chunka C, Banerjee S, Goswami R S. A Novel Key Generating Scheme of Automatic Variable Key[C]//2019 IEEE International Conference on Advanced Networks and Telecommunications Systems (ANTS). IEEE, 2019: 1-5.

- Jiang, W.; Wang, Y.; Ye, S. A Memorable Communication Method Based on Cryptographic Accumulator. Electronics 2024, 13, 1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JIANG,W.B.;GUO,Y.N. Signature and authentication method based on message hash chain[J]. Application Research of Computers. 2022, 39(4): 1183–1189.

- Bernstein, D. J. The Salsa20 family of stream ciphers. In New stream cipher designs: the eSTREAM finalists. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg. 2008, 84-97.

- LI,Z.M. Design and analysis of the hash functions[D]. Beijing University of Posts and Telecommunications,2009.

- WANG, J. Formalizaion of SHA256 algorithm for blockchain[D]. Beijing University of Chemical Technology,2022.

- Goswami, R.S.;Chakraborty, S.K.; Bhunia, A.; Bhunia, C.T. New approach towards generation of automatic variable key to achieve perfect security. In 2013 10th International Conference on information technology: new generations ,2013,pp. 489-491. IEEE.

- Chunka, C.; Banerjee, S.; Goswami, R. S. A Novel Key Generating Scheme of Automatic Variable Key. In 2019 IEEE International Conference on Advanced Networks and Telecommunications Systems (ANTS) ,2019,pp. 1-5. IEEE.

- LI, Z.S. Pseudo-random sequence design and its randomness analysis[D]. University of Electronic Science and Technology of China,2019.

- FAN, L.M.; FENG, D.G.; CHEN, H. Study on the Correlation Between Randomness Tests Based on Entropy[J]. Journal of Software, 2009, 20(7): 1967–1976.

| Symbol | Description |

| The initial key negotiated and allocated by the communicating parties through some secure protocol. | |

| The key required for encrypting the i-th group of plaintext, which is also the i-th node value in the chain key. | |

| The i-th group of plaintext. | |

| The ciphertext corresponding to the i-th group of plaintext . | |

| Encrypting with key to obtain the ciphertext . | |

| Decrypting with key to obtain the plaintext . | |

| Hashing for generating node values in the chain key. | |

| Hashing for generating node values in the message chain. | |

| The i-th node value in the message hash chain. | |

| The message authentication code (MAC) corresponding to the plaintext . In this paper, the MAC is implemented as the hash value of . |

| Comparison Metric | Self-Synchronizing Stream Cipher | Chain Key Model |

| Key Synchronization | Self-synchronizing | Computation Synchronization |

| Plaintext Participation Form | Ciphertext | Plaintext |

| Forward Secrecy | Yes | Yes |

| Backward Secrecy | No | Yes |

| Complexity |

| Keystream Source | Attack Complexity |

| Truly Random Sequence | |

| Communication Mode | 1s | 10s | 100s | |

| Chain key |

Message Transmission Volume/Packets | 1675 | 16522 | 151062 |

| Total Message Length/Bytes | 1112816 | 10744416 | 119830932 | |

| Bit Rate/bps | 8902528 | 8595532.8 | 9586478.56 | |

| DH Key Negotiation |

Message Transmission Volume/Packets | 391 | 12365 | 114020 |

| Total Message Length/Bytes | 310231 | 9014271 | 92014231 | |

| Bit Rate/bps | 2481848 | 7211416.8 | 7361138.48 | |

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | |

| AVK | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 16 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 96 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 238 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 313 |

| ASAVK | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 266 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 330 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 158 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 155 |

| DSAVK | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 7 | 0 | 22 | 58 | 68 | 159 | 85 | 185 |

| DAVK | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 7 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 98 | 0 | 232 | 0 | 285 |

| AVKMSB | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 4 | 7 | 17 | 69 | 72 | 141 | 78 | 194 |

| Chain key | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 4 | 14 | 48 | 66 | 106 | 126 | 153 |

| 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 | 31 | 32 | |

| AVK | 0 | 0 | 0 | 231 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 91 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 15 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| ASAVK | 0 | 0 | 0 | 76 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 15 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| DSAVK | 89 | 137 | 33 | 75 | 20 | 28 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| DAVK | 0 | 227 | 0 | 93 | 0 | 21 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| AVKMSB | 73 | 139 | 58 | 78 | 19 | 20 | 7 | 5 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Chain key | 179 | 117 | 76 | 56 | 36 | 9 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Mean() | Variance() | |

| DSAVK | 15.962 | 9.394 |

| MSBAVK | 16.012 | 8.614 |

| Chain key | 16.267 | 6.407 |

| Algorithm | Encryption / Decryption | Authentication | Seed Key Update Frequency | Communication Key Error Correction and Synchronization |

| Fast (per-packet) | √ | |||

| Fast (per-packet) | √ | |||

| () | Slow (fixed interval) | - | ||

| (Pre-shared Key) | Slow (fixed interval) | - | ||

| Fast (per-packet) | √ |

| Test Content | 64B | 100B | 500B | 1400B | 6400B | 65500B | |

| Encryption/μs | 934 | 1071 | 1235 | 1761 | 4958 | 42804 | |

| Decryption/μs | 942 | 1123 | 1222 | 1824 | 5084 | 43660 | |

| Encryption/μs | 660 | 719 | 846 | 1247 | 4336 | 38156 | |

| Decryption/μs | 792 | 743 | 910 | 1326 | 4360 | 37870 | |

| Encryption/μs | 2138 | 2267 | 2347 | 2471 | 4146 | 19157 | |

| Decryption/μs | 2162 | 2296 | 2359 | 2500 | 4508 | 20177 | |

| Encryption/μs | 1712 | 1881 | 1947 | 2138 | 3600 | 15636 | |

| Decryption/μs | 1774 | 1994 | 2039 | 2121 | 3378 | 16254 | |

|

(Pre-shared Key) |

Encryption/μs | 1011 | 1277 | 1658 | 2387 | 7692 | 73484 |

| Decryption/μs | 1043 | 1376 | 1660 | 2619 | 9028 | 85201 | |

| (No Authentication) | Encryption/μs | 791 | 760 | 1167 | 2001 | 6545 | 60826 |

| Decryption/μs | 819 | 848 | 1456 | 2349 | 7533 | 72613 | |

| Encryption/μs | 8784 | 9156 | 9738 | 11999 | 17157 | 68877 | |

| Decryption/μs | 93298 | 96284 | 101692 | 103294 | 97948 | 161392 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).