1. Introduction

In this paper, we translate the properties of the Möbius transformations of the Riemann sphere to the second symmetric product of the complex plane

. That is, let

T be a Möbius map, consider two complex numbers

z,

w, and consider the sets of the form

, in the space

, called the second symmetric product of the complex plane

, which we will topologize through the Hausdorff metric, see [

2] and [

6].

To study the geometry of these transformations in this space, we introduced a model for

, that is, there is a homeomorphism from

to a more suitable space in which we can have a better understanding of the geometry induced by

, for any Möbius transformation

T. The homeomorphic model of

is the space

where

and

s is a relation on elements of the form

, see [

9].

Given a Möbius transformation in the Riemann sphere, we will define in the second symmetric space , the function given by , whenever T is defined in z and w. Recall that for , , so we need to change the definition of when z or w are equal to ; this change will produce discontinuities at some points, but on the other hand the change will be compatible to have some results similar to properties inherent in the set of Möbius transformations.

In

Section 3, we define the set

, where each

is taken with its corresponding domain and image. We look closely how the domains of these maps change depending on

T and we describe the action of these maps via the usual generators of the group of Möbius transformations, describing in Propositions 2–5 the action of the generators in the space

.

Some transitivity properties of the usual Möbius transformations can be translated on transitivity features of the set in . In Proposition 8, we prove that is 2-transitive in if the corresponding points have the same cross ratio.

Now, if we consider the set of Euclidean circles and the family of lines in , the corresponding objects in are Möbius strips and semi-planes, respectively. Proving first that preserves these sets of Möbius strips and semi-planes, we show in Theorem 8, that acts transitively in those sets. We also define maps that preserve the Möbius strips generated by Euclidean circles in and prove some properties of these maps.

As any Möbius transformation

T, different to the identity, is conjugated to a map of the form

with

or to the map

, in

Section 5, we extend this result for maps in the set

in Theorems 10, 11, and 12, depending if

T is parabolic, hyperbolic or elliptic, respectively. Finally, we show how the corresponding maps to

in

act.

2. Preliminaries

In this section, we will briefly present the definitions and results about Möbius transformations and the second symmetric product of , that we will need in the rest of the paper.

2.1. Möbius Transformations

First, let us describe some basic facts about Möbius transformations, for more details, see [

1] and [

4]. Let

be the Riemann sphere. We will denote by Aut

the set of all automorphisms of

, that is, functions of the form

with

complex numbers such that

. The transformations

are known as

linear fractional or

Möbius transformations. These transformations form a group under composition, where the inverse map of

T is given by

Moreover, as T does not determine the coefficients uniquely, since , , , correspond to the same transformation T, for , the group Aut is isomorphic to the projective general linear group and to the projective special linear group, that is, Aut, thus from now on we can assume that .

There are four special type of Möbius transformations that generate Aut:

The map ( is a rotation of the Riemann sphere by an angle .

The transformation , that interchange 0 and ∞.

The map () fixes 0 and ∞, and acts in the plane as a similarity transformation.

The transformation () fixes ∞ and acts as a translation in the complex plane.

One of the important properties of the group Aut is that maps circles in to circles in . In order to be more precise, the circles in are the usual Euclidean circles and the straight lines in (which can be thought as circles through infinity).

Theorem 1. If C is a circle in and if Aut, then is a circle in .

The group Aut also has several properties about transitivity, the following are the ones we will use in this paper.

Theorem 2. If and are triples of distinct points in , then there is a unique Aut such that , for .

Corollary 1. If Aut and T fixes three distinct points of , then T is the identity map.

Theorem 3. If C and are circles in , then there exists some Aut such that .

In general Aut is not 4-transitive, but if two 4-tuple of distinct points have the same cross ratio, there is some Möbius transformation that send one 4-tuple into the other. Recall that the cross ratio of four complex numbers is defined as with the convention of taking limits if some .

Theorem 4. Let and be 4-tuples of distinct elements of . Then there exists some Aut with , if and only if the two 4-tuples have the same cross ratio.

Consider a circle

C in

given by the equation

, with

,

. If

, then

C is a Euclidean circle in the complex plane, and then there exists a transformation in the complex plane that fixes

C. This transformation is given by

and it is called the inversion in

C. Moreover, if

Aut

, then

is another circle, then we have that

.

To study the geometry of the Möbius transformations, there is a classification in conjugacy classes according to the number of fixed points and to the corresponding trace of the matrix associated in to every map in Aut. The next results summarize this classification.

Theorem 5. Let , with . If , then T has two fixed points in ; if and T is not the identity map, then T has one fixed point in .

For , consider the maps if and . We will say that two maps T and S are conjugated if there exists another transformation V such that .

Theorem 6. Let T be a non-identity element in Aut, then there exists some such that T is conjugate to in Aut.

Remark 1. When , the map T has only one fixed point and it is conjugated to by a Möbius transformation S that sends to ∞. Since , then any is moved by towards as n goes to infinity. In this case T is called parabolic.

Remark 2. If T in not parabolic, then it has two fixed points and and is conjugated to with , that fixes 0 and ∞, by means of a Möbius transformation S such that and . If , for all and hence for all . In the same way if , then for all (the two cases for are basically the same since we just replace by ). We conclude that if , all points are moved by T away from one of these fixed points towards the other. If , T is called hyperbolic, and loxodromic otherwise. If , with , then is a rotation , so has not limit for , hence neither for . In this case T is called elliptic.

2.2. Second Symmetric Product of

The

second symmetric product of

, denoted by

, is the set

The space

has the topology induced by the following metric

where

,

is the usual metric in

, and

A and

B are subsets of

. Given

X a compact subset of

, the space

can also be topologized through the Vietoris topology: if

are nonempty subsets of

and

, then define

a base for the Vietoris topology is given by the family of the sets

, where

and

are open subsets of

. The Vietoris topology and the topology induced by the Hausdorff metric coincide in

.

Let

X be a connected and compact subspace of

. It is known that

is a continuum itself [

7]. In [

2] it is proven that, for

,

is homeomorphic to a 2-cell. In [

6], it is proven that for the 1-sphere

,

is homeomorphic to a Möbius strip.

2.3. A Model for

To have a better understanding of the space , sometimes we will work in a model of , that is, a continuous and bijective copy of . Let be the space , where , the unit circle and such that s is a relation defined by , for all .

Definition 1. Let

be the function

given by

We observe that is a well defined, bijective and bicontinuous function, with the corresponding topologies. We will call the model of .

Remark 3. Observe that given a point , with , and , we can obtain its preimage under as follows: u must be the midpoint of two points and in the complex plane such that and , where , then and are points in the circle with center u and radius , such that the segment is a diameter of the circle. Hence, and .

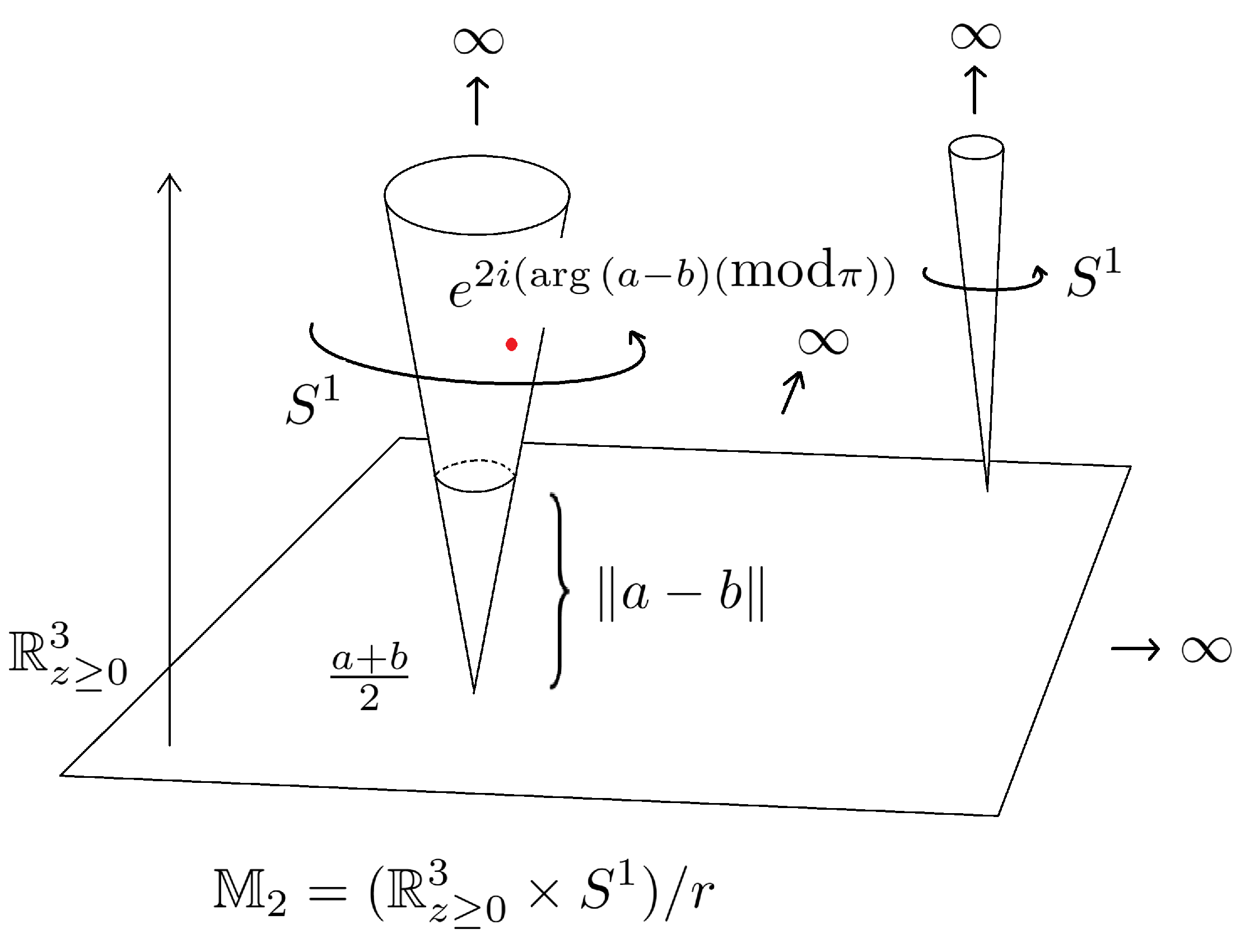

In

Figure 1, we can observe a representation of the model

, for instance over any point

, the midpoint of

a,

, there is a cone

V with vertex at

t, so any two points

z,

with midpoint

t has a representation in

V at height

and angle

.

Let , observe that there exists a closed disk D, that contains x and y in its interior, then is a neighborhood of in . Given that is a compact set, it follows that is a Hausdorff and a locally compact topological space, then it is possible to consider the Alexandroff’s compactification, denoted by . The point added is denoted by ∞ (observe that this point will correspond to the pair of points in , for each ). Note that in the sets such that are mapped by to a open topological disk, hence the Alexandroff’s compactification of such a set will be homeomorphic to . Moreover, observe that the singletons together with the point ∞ in is homeomorphic to .

3. Extension of the Möbius Transformations to the Space

Let

be a Möbius transformation in the Riemann sphere, let us define in the second symmetric space

, the function

given by

In particular, observe that if , then , hence the geometry of T in will be reflected in . As T has an inverse map , it is easy to see that in some appropriate domains and are the identity maps.

Observe that we can use the map , to translate the definition of T all the way to , that is, we can conjugate the map in some appropriate domain, via , to obtain a map in . So, from now on by convention, for any object X in , we will use for the object in generated by X, and for the corresponding object in the model .

Recall that a Möbius transformation T has at most two fixed points, and let us assume that T does not fix the point at infinity in the Riemann sphere. First, suppose that T has only one fixed point , then the map has also as the only fixed point; meanwhile, if T fixes two distinct points and , then has three fixed points: .

As the map T is defined in , we need to consider the image and pre-image of the point at infinity, that is, and . Let us define the sets and , then we have our first result for the map .

Lemma 1. For any Aut, the map is an homeomorphism.

Proof. Assume that . First, let us prove that is a bijection. Let and be two points in , such that , then it follows that . If , then for which , therefore ; if now , then , and then or ; in the former case, , and in the latter case, . In any case, we have that , since T is a one-to-one map, for which it follows the injectivity of .

It is clear that for any pair of point , neither equal to , there are points such that and , by the surjectivity of T, and therefore is onto. Now, observe that is the inverse map of .

Finally, to establish the continuity of the map observe that and , so by the continuity of T and the characterization of the open sets in the Hausdorff topology on we have the result. □

Observe that if

, then the map

can be defined in all

as in relation (

1), and it is an homeomorphism there. For a general map

, we can think of the action of

in

as follows. For any

, we define the cone of vertex at

w as the set

. Let

and

. Then

acts sending the cone

with vertex at

one-to-one to the cone

with vertex at

, since

, for any

. In fact, using the same arguments in the proof of Lemma 1, we have the following.

Lemma 2. Let be an element in Aut, then the map is an homeomorphism, for any .

There are some special cones that need to be considered in the definition of . Suppose that is a fixed point of T, then the cone is invariant under , that is, is a homeomorphism from to ; when T has two fixed points and , the two cones and intersect each other in the other fixed point of .

So far, we have defined

only in

(and then

only in

), so we need to extend the definition of

. Observe that the set where we have not defined

yet is precisely the cone

, which will be called the

singular cone for T, and the other cone

, will be called the

singular value cone for T. For

, define the function

as follows

Remark 4. Since T is bijective map in , we have that is a bijection from to . Also, observe that in the cone , the map sends continuously circles at some particular height to topological circles in . Moreover send points in the cone close to the vertex to points in the cone close to infinity, and points in close to infinity to points in close to the vertex .

In this way, we have defined in , and therefore in all since was already defined in . Moreover . Thus, we have extended the definition of to with image , so in a natural way we can extend the definition of to , sending and . Using the notation that we have been using so far, we have the following result.

Theorem 7. Let be a Möbius transformation in the Riemann sphere. Then the map is a bijective map, continuous in and continuous in .

Proof. By Lemma 1, the map

is an homeomorphism in

. As

in a bijective way by Equation (

2), and

and

, we conclude that

is a bijection. By Remark 4, we see that

is continuous within

. □

Remark 5. Since by Lemma 1, the map is an homeomorphism, any extension of the map in must has image . If we consider a sequence of points that converges to a point in and consider the open set in that contains the point , for some , then there exists such that if , it follows that . This means that for all , and or and , hence, there are sequences of complex points , such that , , as and for . As T is a continuous map, it follows that , therefore we can not have continuity for the map when we approach from .

Remark 6. It seems that we can use another compactification of , different from Alexandroff’s compactification, in such a way the map is an homeomorphism in this new space, we just add a cone with vertex at infinity compatible with the topology of ; however we will lost the advantages to have the model for such as to be able to have a geometric description of the maps . Another possible direction is to work in the second symmetric product of the Riemann sphere , but we again lost the possible model to describe the geometry of the maps .

Nevertheless, the map is a bijective map, so we can define the set of transformations , where is defined as before, hence the set is a group with the composition of maps as its group operation. In fact, if and are two Möbius transformations, then we have that is well defined in all . We will explore more about the structure of this group in a future manuscript.

3.1. Generators of

We will show now that all the maps in are compositions of the following four maps:

, ;

, for ;

, ;

, .

Observe that

,

and

are homeomorphisms defined in all

, meanwhile

is defined in all points

, with

, but we can extend the definition of

in its singular cone

as in relation (

2), that is,

, for

, and observe that for

J its singular cone coincide with its singular value cone.

Proposition 1. Let S be a map in , then S can be expressed as a composition in some order of the maps , , and .

Proposition Let Aut such that , and assume that . If , we know that , where y , hence it is straightforward to see that .

Now, when , , where . By the first part of the proof, , for some , and . Therefore . Note that the previous decomposition of even works for the singular cone , take , then .

Let us analyze the geometry of these generators maps in the space . In order to do that, let us work in the model of . Since is an homeomorphism we can conjugate any map to a map , that is, , extending the definition to infinity in a natural way. In particular, the elements of can be thought acting in , so in some cases we will not make distinction if the context is clear.

Let us start with the map

,

, and the analysis for the other maps will be similar. In this case, the conjugation gives a map

such that

; the left side composition satisfies that

and the right side composition is equal to

then the following result follows directly.

Proposition 2. The map acts in the following way , for , and .

As a result we can determine the geometry of the map in , stated as follows.

Corollary 2. The map acts conjugated as a double rotation with the same angle, in fact, this double rotation moves a point around a topological torus.

Proof. Just observe that since is conjugated to , and by Proposition , , the orbit of the point stays at the same height and the first and third coordinates are rotated by the same angle, so the result follows. □

In the same way, we can determine the action of corresponding maps and in the space .

Proposition 3. The map acts as follows, , for , and .

Proof. From the conjugation

, we obtain that

from where it follows the claim, observing that

. □

Using the definition in [

8] of a topological attractor, we have the following.

Corollary 3. The point with coordinates is a fixed point of , which is a global topological attractor for the dynamics of , when .

Proof. Remember that s is the relation defined by for all , so all points can be identified to the point . Now it is clear that is a fixed point of . By Proposition 3, the map is defined as , hence iterating this map, we obtain that , and since , we obtain that , as . □

Proposition 4. The map acts in the following way , for , and .

Proof. From the conjugation

, we obtain that

from where it follows the claim. □

The next result follows directly from Proposition .

Corollary 4. The orbit of every point in under the map goes to infinity.

Finally, let us analyze the action of the map

in

. Using the conjugation

, we get, first of all for

, that

On the other hand, , hence , where , , and , are the complex numbers that depends of u as in Remark 3.

In the cone

we get that

That is, , for and . In this way we can prove the following.

Proposition 5. The map satisfy that , the identity map in the model of .

Proof. For , we have that , then as , the result follows. In the cone , just notice that , conjugating with the map we have the result. □

4. Transitivity of

In this section we will prove several results about transitivity in the space . Let us start with two triples of distinct points in , that is, and , then we can consider the triples of distinct points in : and . The first instance of transitivity is the following.

Proposition 6. If and are triples of distinct points in , then there is a unique such that , for all , with .

Proof. By Proposition 2, there is Aut such that , for , then , for all , with .

Suppose there is another element in such that . Consider the image of the first point, , then there are two cases. If , then , and taking one of the other two points in , we see that . By Proposition 2, we have that and then . In case that , then , but we have that which is a contradiction since , this finish the proof of the uniqueness of the map . □

Using the same argument as in the proof of the uniqueness in the previous result, we obtain the next Corollary.

Corollary 5. If fixes three distinct point of the form , then is the identity map.

We can use again the 3-transitivity of Aut and the arguments of the proof of Proposition 6 to prove the following result.

Proposition 7. Consider two pairs of points , and , in with and , then there is a unique such that and .

As a corollary we obtain that the Möbius transformations in act transitively in the set of cones .

Corollary 6. Let and be two singletons in . Then there exists such that , that is, is transitive in .

Proof. Consider different points , and , , by the 3-transitivity of Aut there exists a transformation such that for . Hence , and . Let be a point in , with , then ; for points , we get . □

For general points in , we can prove 2-transitivity of the set if these points combined have the same cross ratio.

Proposition 8. If and are pairs of distinct points in , such that the cross ratio of is equal to the cross ratio of , then there is such that and .

Proof. By Proposition 2, there exists Aut such that , for , then and . □

4.1. Transitivity of Möbius Bands

Let us consider the family of Euclidean circles in and the family of lines in , remember that Aut sends in itself, in fact, the action is transitive there.

We have observed that is homeomorphic to a Möbius strip, then is a Möbius band , for any . Moreover, passing to the model , we can see that is a Möbius band that intersects the subset of exactly in C.

It is not difficult to see that is homeomorphic to a semi-plane in the model , for any , in fact, .

Lemma 3. Let K be an element in , then for any map S in , the set is homeomorphic to a Möbius strip or homeomorphic to a semi-plane in the model .

Proof. Let S be an element of , then the corresponding map Aut (that is, ) satisfies that is an Euclidean circle or a line in . Assume first that is an element of , the proof for the other case is similar. Passing to the model , consider the set .

First, if is an Euclidean circle, then is a Möbius band. Since and , for any , it follows that .

Now assume that is a line in , this happens if and the point is a point on C. Remember that in this case , and ; then we only consider the image of , that is, is a complete line since . It follows that still is a whole semi-plane and once again, using that , we get that , which conclude the proof. □

Now we will prove transitivity for a family of Möbius strips in . Consider the set , that is, consists of Möbius bands and semi-planes generated by Euclidean circles and lines in , respectively.

Theorem 8. The set acts transitively on , that is, if , , then there exists such that .

Proof. Let and be two elements in . Let , be two different points in and let , be two different points in , then are in the same Euclidean circle or in the same line in , that generates the Möbius strip or the semi-plane , and the same holds for , they are in the same Euclidean circle or in the same line in , that generates the Möbius strip or the semi-plane .

Notice that since , are different, then there are at least three different complex numbers in the set , and the same happens in the set . By Proposition 2 there is a unique Möbius transformation S that sends the three different points in A into the three different points in B. Since three points suffice to determine a circle or a line, then , thus and the result follows. □

The next result characterize the sets in using cross ratio.

Corollary 7. Let be an element in and let be a point in . Then .

Proof. First, observe that is a line in . The set is generated by an Euclidean circle or a line K in . Let T be the Möbius transformation such that , then if it follows that . By Theorem 2, and the result follows. □

4.2. Inversion in Möbius strips

Let

C be a circle in

given by the equation

, with

,

. If

, then

C is a Euclidean circle in the complex plane, and then there exists a transformation in the complex plane that fixes

C, such transformation is given by

and it is called the inversion in

C. This transformation fixes point-wise the set

C, sends the center of

C to infinity and vice versa, and

is the identity map. Moreover, if

Aut

, then

is another circle and we have that

.

Given an Euclidean circle

C in

, we have that

is homeomorphic to a Möbius strip, for which we can define its inversion as follows. Let

be the corresponding Möbius band in the model

, and let

given by

, where

is given by

, for

, and

, where

is the center of

C. We call the map

the inversion in the Möbius band

. Then we have the following properties for the map

, taking

as in (

3) from now on.

Proposition 9. The map fixes point-wise the Möbius strip and is the identity map in .

Proof. As fixes the set C point-wise, it follows that if . Thus , we conclude that fixes point-wise.

The second statement follows from the fact that , for any ; and . □

Remark 7. For any complex number z we know that , then it follows that is a fixed point for , that is, not only fixes the Möbius strip , but has infinitely many other fixed points. Observe that these points correspond to infinite rays coming out from the manifold boundary of the fixed Möbius strip; and these rays do not intersect. Therefore, the fixed set is homeomorphic to a real projective plane minus a point. Moreover, every point in is a fixed point or a periodic point of period 2 under .

Now let us consider two Möbius bands , in , so we know that there is a Möbius transformation T such that , then the next result follows.

Proposition 10. The inversions and of two Möbius bands and in , respectively, are conjugated in the subset of .

Proof. Just observe that there is a Möbius transformation such that . Since , it follows that in , and then after conjugating with we obtain , in . □

Note that we can extend the conjugation to , since we must have that , and then use the map . Notice that when is a line we have that , then .

In particular, consider the real line , then for any Euclidean circle C, we can send C to by a Möbius transformation , then the point since . Thus , where . In , we get that , and , since , where as . In this way, we have defined the conjugation in all and then we can pass to .

Theorem 9. For any element in , the inversion in is conjugated to the map , given by , for , and .

Proof. Let

T be the Möbius transformation such that

, and we assume that

C is an Euclidean circle, the case when

C is a line is similar. Since

, it follows that the map

is defined in

as

. Thus

is defined in

, using the conjugation

, we obtain that

is equal to

, and the result follows in

.

To complete the proof, observe that for points

, we get that

but since

, then

,

and

, so we can conclude that for

it follows that

, as well. □

5. Conjugacy Classes in

For , consider the maps if and , otherwise; all these maps are elements in Aut. Then, if T is a non-identity element in Aut, then T is conjugate to for some . In this section we will extend this result for maps in , starting with the case .

5.1. Parabolic Maps

Let be a Möbius transformation with only one fixed point at , then T is called a parabolic transformation and it is conjugated to the map . Let S be the Möbius transformation that conjugates T and , remember that , so for some . In order to see the conjugation in , we need to consider the singular cones of T and S.

First, consider the singular cone of S, that is, that coincide with the cone , then is given by . So the conjugation in is given by , then we defined in as . Similarly, in the singular cone of T, we have that, , and the last quantity we would like to be equal to , then we define in .

In any other cone , with , we have that , in , that is, . Using the relation , we can conjugate the action of in to the action of in .

Remark 8. In

, we obtain that

Remark 9. Meanwhile in

, we get, setting

and

Setting we get the following result.

Theorem 10. Let be a map with only one fixed point, then W is conjugated to the map given by , for , and .

Proof. As W has only one fixed point in , then for a parabolic map. Since T is conjugated to the map , then the result follows by Proposition 4, taking , since for any , the map . □

Corollary 8. The orbit of every point in under a parabolic map in tends to the fixed point of the map.

Proof. Let us start in

, since

by 8, it follows that

then

, as

n goes to infinity. Since

, then

. The argument for points in

and in

is the same, by Remark 9 and Theorem 10. □

5.2. Hyperbolic, Loxodromic and Elliptic Maps

Now, let be a Möbius transformation with two fixed points and , then it is conjugated to the map with , by means of a Möbius transformation S such that and , that is, we can take . If and , then T is called hyperbolic; otherwise T is called loxodromic; If , the map T is called elliptic. As in the parabolic case, in order to find the map that is conjugated to , we need to consider some special subsets of and some generalities about the conjugation in this setting before to analyze the different cases.

Let us consider three special cones: the singular cone of T, , and the cones , , where the singular cone of S coincide with . Observe that , , for , and . For points in we would like to have that , so we define in . In the same way, in we need to happen that , so we define in . Finally, if we set and , we have that in we must have that , so we define in .

For , we have that , that is, in any cone . Using the relation , we can conjugate the action of in to the action of in .

Proceeding as in Remarks 8 and 9, we obtain the conjugation in the corresponding domains. In

, we obtain that

Meanwhile in

, we get, setting

and

5.2.1. Hyperbolic and Loxodromic Maps

Let be a Möbius transformation conjugated to with . Let , then we get the following result.

Theorem 11. Let be a map such that T is a hyperbolic map. Then is conjugated to the map given by , for , and .

Proof. From the conjugation

, we obtain that

from where it follows the claim. □

By the action of

in

, that is, by Equations (

4)–(

6) and by Theorem 11, as well as Remark 2, we conclude the following result.

Corollary 9. The orbit of every point in under a hyperbolic or loxodromic map in tends to one of the fixed point of the map and away from the other fixed point.

As in the classical theory of Möbius transformation, we can make a geometric distinction between hyperbolic and loxodromic elements in . Remember that T, a hyperbolic Möbius transformation, always has an invariant disc in the complex plane, that is, it leaves its boundary invariant, so the corresponding map must leave a Möbius strip invariant; meanwhile a loxodromic element can not leave any Möbius band invariant.

5.2.2. Elliptic Maps

Let be a Möbius transformation with two fixed points and conjugated to the map with but . Let we get the following result.

Theorem 12. Let be a map such that T is an elliptic map. Then is conjugated to the map given by , for , and .

Proof. The proof follows the same lines as before, from the relation

, we obtain that

from where it follows the claim. □

By the final part of the Remark 4 and the previous Theorem, for an elliptic map T, the set has no limit, for any point , with .

The period or order of a Möbius transformation T is the least positive integer m such that is the identity map, if such an integer exists. So we have the next consequence of Theorem 12.

Corollary 10. If T is a non-identity Möbius map with finite period n, then the map conjugated to satisfies that is the identity map in .

Proof. Since

T has finite period, then it is an elliptic map conjugated to the map

, with

,

and

. By Theorem 12,

is conjugated to the map

given by

, for

,

and

. Then

which proves the claim. □

We can say a little more about elliptic maps with finite period. Since is the identity map, we have that , for . Recall that , and then since is the identity. Hence, for , we have that , and then , therefore . In order to get the identity we need to iterate the map times to get the identity, that is, . Thus, for any elliptic Möbius map with finite period, we get a map in that also has finite period, which gives us an example of a finite subgroup in .