Submitted:

25 January 2025

Posted:

27 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

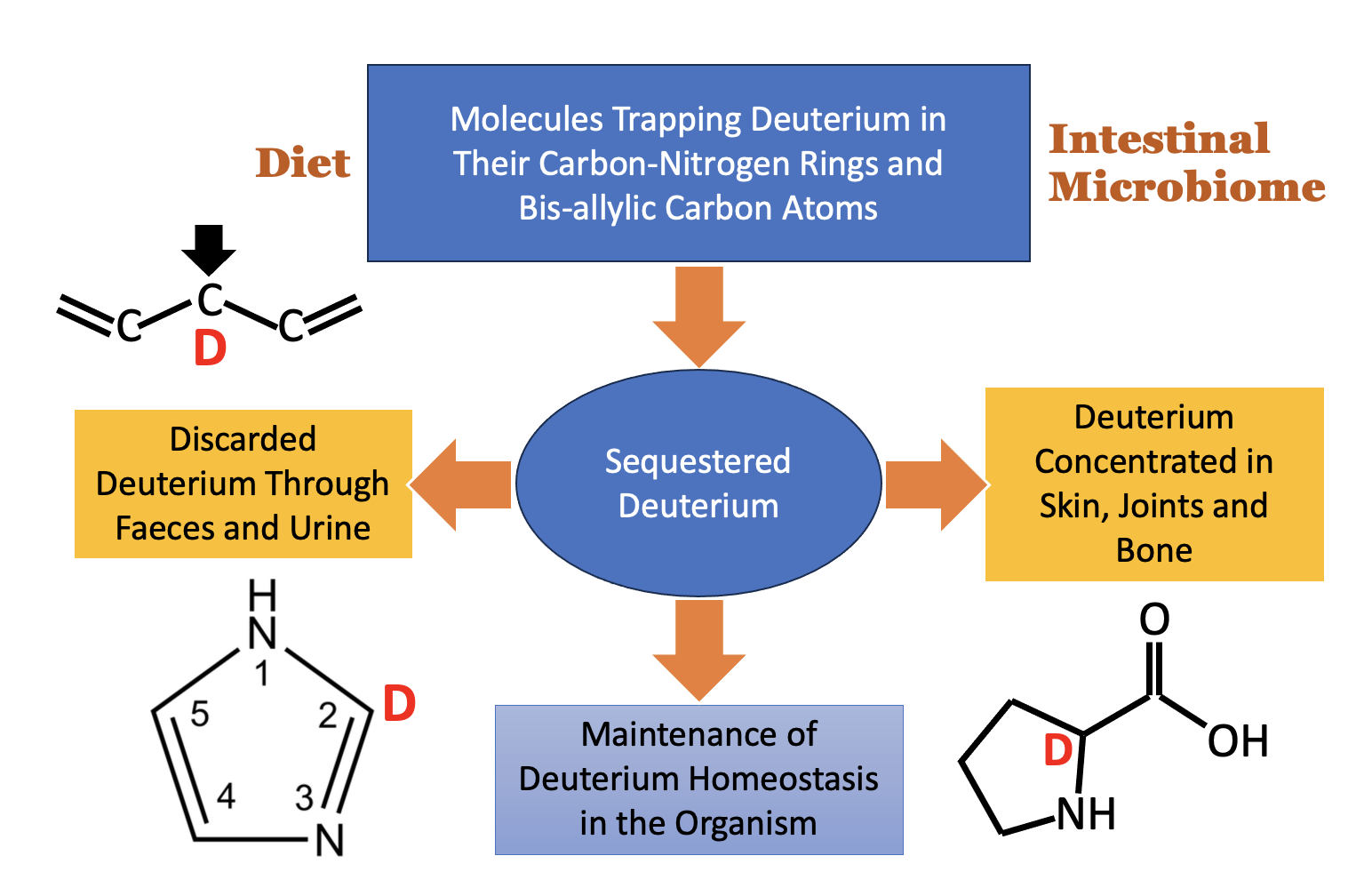

1. Introduction

2. Hydrogen/Deuterium Exchange: A Brief History

3. Lutein and Carotenoids

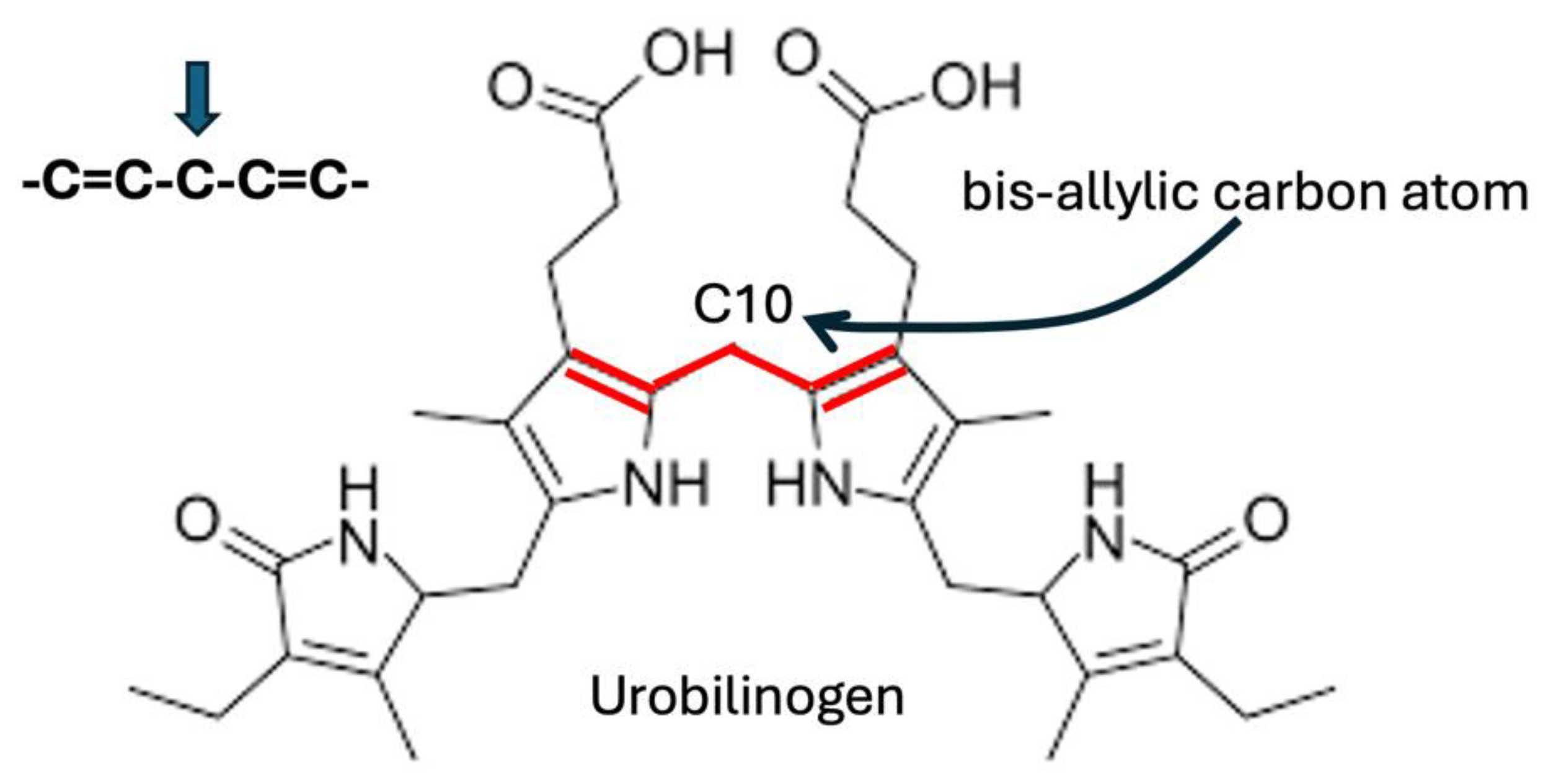

4. Hemoglobin Metabolism and Bilirubin Cycling

5. Gut Microbial Processing Beyond Bilirubin: Bis-allylic Carbon

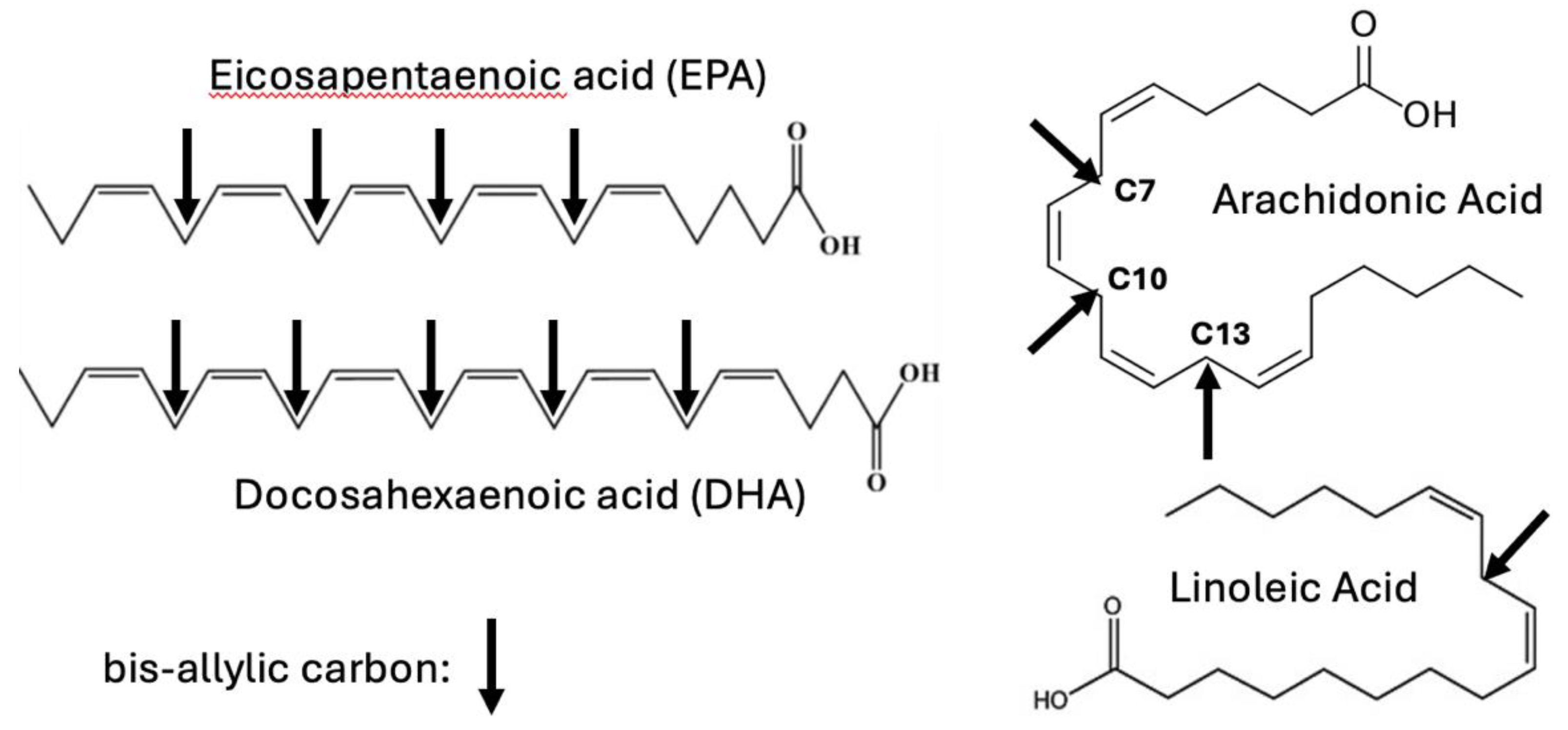

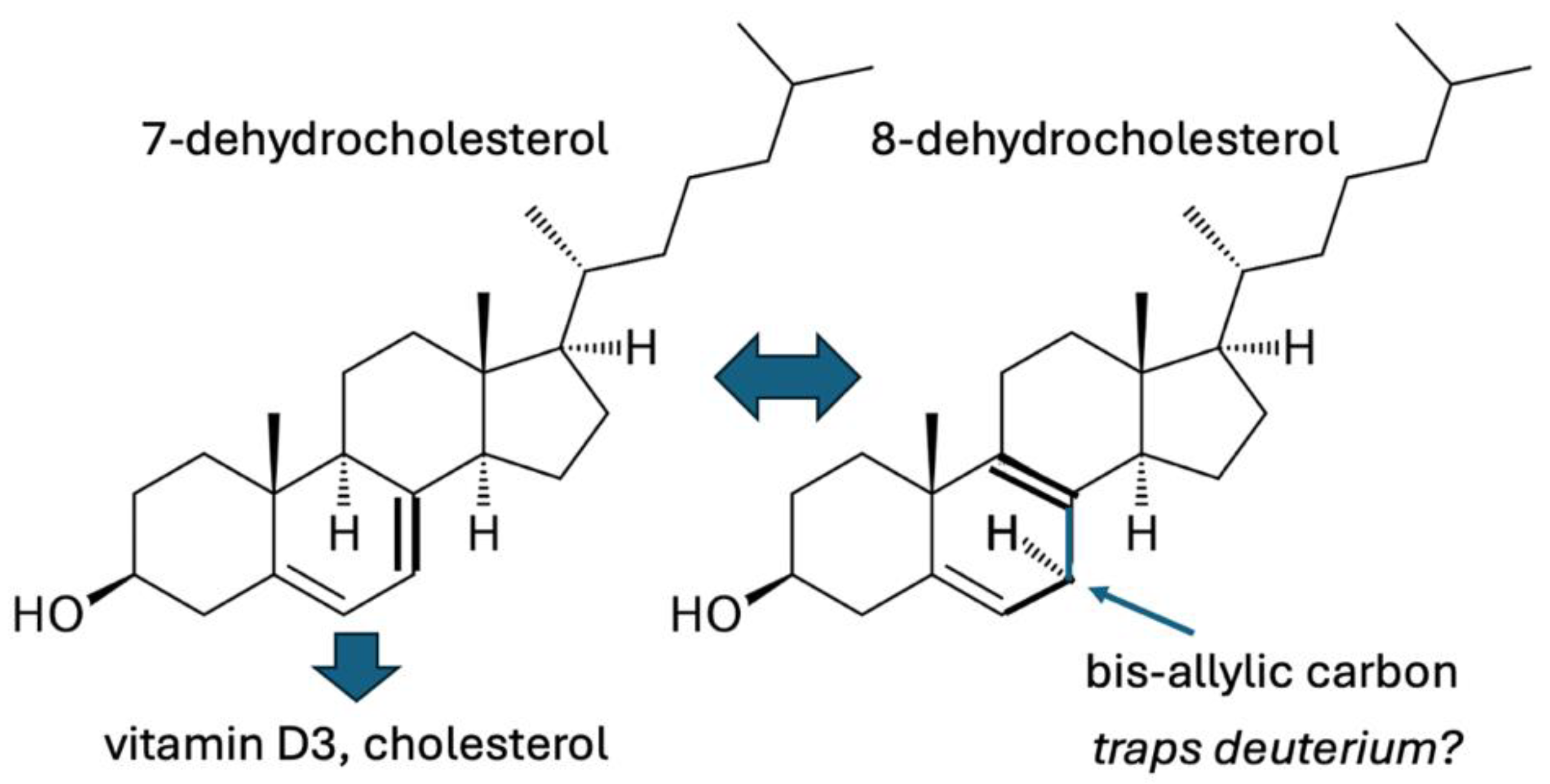

6. Other Biologically Active Molecules Containing Bis-allylic Carbon

6.1. Lipid Peroxidation of Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids

6.2. Can Deuterated PUFAs Be Therapeutic in the Plasma Membrane?

6.3. A Role for Deuterium in the Resolution of Inflammation

7. Histidine, Histamine, Histamine Metabolites, and the Imidazole Ring

7.1. C2 in the Imidazole Ring Traps Deuterium

7.2. Metabolism of Histidine by Intestinal Flora and Mast Cells

8. Proline

8.1. Proline Traps Deuterium in C1

8.2. Cyclic Peptides

9. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zong, Y.; Li, H.; Liao, P.; Chen, L.; Pan, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Zhang, C.; Liu, D.; Zheng, M.; Gao, J. Mitochondrial dysfunction: mechanisms and advances in therapy. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2024, 9, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seneff, S.; Kyriakopoulos, A.M. Taurine prevents mitochondrial dysfunction and protects mitochondria from reactive oxygen species and deuterium toxicity. Amino Acids. 2025, 57, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagel, Z.D.; Klinman, J.P. Update 1 of: Tunneling and dynamics in enzymatic hydride transfer. Chem Rev. 2010, 110, PR41–PR67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutcliffe, M.J.; Masgrau, L.; Roujeinikova, A.; Johannissen, L.O.; Hothi, P.; Basran, J.; Ranaghan, K.E.; Mulholland, A.J.; Leys, D.; Scrutton, N.S. Hydrogen tunnelling in enzyme-catalysed H-transfer reactions: flavoprotein and quinoprotein systems. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2006, 361, 1375–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeCoursey, T.E.; Cherny, V.V. Deuterium isotope effects on permeation and gating of proton channels in rat alveolar epithelium. J Gen Physiol. 1997, 109, 415–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olgun, A. Biological effects of deuteronation: ATP synthase as an example. Theor Biol Med Model. 2007, 4, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krichevsky, M.I.; Friedman, I.; Newell, M.F.; Sisler, F.D. Deuterium fractionation during molecular hydrogen formation in marine pseudomonad. J Biol Chem. 1961, 236, 2520–2525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.-H.; Steinberg, L.; Suda, S.; Kumazawa, S.; Mitsui, A. Extremely low D/H ratios of photoproduced hydrogen by cyanobacteria. Plant and Cell Physiology 1991, 32, 897–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, E.A.; Rensner, J.J.; Larsen, K.R.; Bellaire, B.; Lee, Y.J. Rapid antibiotic susceptibility testing by deuterium labeling of bacterial lipids in on-target microdroplet cultures. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom 2022, 33, 1221–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saikia, D.; Vijay, A.; Cebajel Bhanwarlal, T.; Singh, S.P. Validating the utility of heavy water (Deuterium Oxide) as a potential Raman spectroscopic probe for identification of antibiotic resistance. Spectrochim Acta A Mol Biomol Spectrosc. 2024, 321, 124723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grocholska, P.; Bąchor, R. Trends in the hydrogen-deuterium exchange at the carbon centers. Preparation of internal standards for quantitative analysis by LC-MS. Molecules. 2021, 26, 2989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leadlay, P.F.; Albery, W.J.; Knowles, J.R. Energetics of triosephosphate isomerase: deuterium isotope effects in the enzyme-catalyzed reaction. Biochemistry. 1976, 15, 5617–5620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewis, C.A.; Parker, S.J.; Fiske, B.P.; McCloskey, D.; Gui, D.Y.; Green, C.R.; Vokes, N.I.; Feist, A.M.; Vander Heiden, M.G.; Metallo, C.M. Tracing compartmentalized NADPH metabolism in the cytosol and mitochondria of mammalian cells. Mol Cell. 2014, 55, 253–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rozman, M. The gas-phase H/D exchange mechanism of protonated amino acids. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2005, 16, 1846–1852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kersteen, E.A.; Raines, R.T. Catalysis of protein folding by protein disulfide isomerase and small-molecule mimics. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2003, 5, 413–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Schwörer, S.; Berisa, M.; Kyung, Y.J.; Ryu, K.W.; Yi, J.; Jiang, X.; Cross, J.R.; Thompson, C.B. Mitochondrial NADP(H) generation is essential for proline biosynthesis. Science 2021, 372, 968–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, J.; Coote, M.L.; Easton, C.J. Validation of the distal effect of electron-withdrawing groups on the stability of peptide enolates and its exploitation in the controlled stereochemical inversion of amino acid derivatives. J. Org. Chem. 2011, 76, 5907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, J.; Easton, C.J.; Coote, M.L. The distal effect of electron-withdrawing groups and hydrogen bonding on the stability of peptide enolates. J Am Chem Soc. 2010, 132, 5515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bąchor, R.; Setner, B.; Kluczyk, A.; Stefanowicz, P.; Szewczuk, Z. The unusual hydrogen-deuterium exchange of α-carbon protons in N-substituted glycine-containing peptides. J Mass Spectrom. 2014, 49, 43–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bąchor, R.; Dbowski, D.; Łęgowska, A.; Stefanowicz, P.; Rolka, K.; Szewczuk, Z. Convenient preparation of deuterium-labeled analogs of peptides containing N-substituted glycines for a stable isotope dilution LC-MS quantitative analysis. J Pept Sci. 2015, 21, 819–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitra, S.; Rauf, A.; Tareq, A.M.; Jahan, S.; Emran, T.B.; Shahriar, T.G.; Dhama, K.; Alhumaydhi, F.A.; Aljohani, A.S.M.; Rebezov, M.; Uddin, M.S.; Jeandet, P.; Shah, Z.A.; Shariati, M.A.; Rengasamy, K.R. Potential health benefits of carotenoid lutein: An updated review. Food Chem Toxicol. 2021, 154, 112328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhosale, P.; Serban, B.; Bernstein, P.S. Production of deuterated lutein by chlorella protothecoides and its detection by mass spectrometric methods. Biotechnol Lett 2006, 28, 13711375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thiagarajan, P.; Parker, C.J.; Prchal, J.T. How do red blood cells die? Front Physiol. 2021, 12, 655393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fraser, S.T.; Midwinter, R.G.; Berger, B.S.; Stocker, R. Heme oxygenase-1: a critical link between iron metabolism, erythropoiesis, and development. Adv Hematol. 2011, 2011, 473709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; de Montellano, P.R. The binding sites on human heme oxygenase-1 for cytochrome p450 reductase and biliverdin reductase. J Biol Chem. 2003, 278, 20069–20076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weaver, L.; Hamoud, A.R.; Stec, D.E.; Hinds, T.D., Jr. Biliverdin reductase and bilirubin in hepatic disease. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2018, 314, G668–G676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Wu, C.; Li, L.; Shi, H.; Li, C.; Yin, S. Toward nanotechnology-enabled application of bilirubin in the treatment and diagnosis of various civilization diseases. Mater Today Bio. 2023, 20, 100658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, B.; Levy, S.; Dufault-Thompson, K.; et al. BilR is a gut microbial enzyme that reduces bilirubin to urobilinogen. Nat Microbiol 2024, 9, 173184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, T.; Sato, K.; Akiba, M.; Ohnishi, M. Urobilinogen, as a bile pigment metabolite, has an antioxidant function. Journal of Oleo Science 2006, 55, 191–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, Y.A. Emerging roles of polyunsaturated fatty acid synthesis pathway in colorectal cancer. Anim Cells Syst (Seoul). 2023, 27, 61–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayala, A.; Muoz, M.F.; Argelles, S. Lipid peroxidation: production, metabolism, and signaling mechanisms of malondialdehyde and 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2014, 2014, 360438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mylonas, C.; Kouretas, D. Lipid peroxidation and tissue damage. In Vivo. 1999, 13, 295–309. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Djuricic, I.; Calder, P.C. Beneficial outcomes of omega-6 and omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids on human health: an update for 2021. Nutrients. 2021, 13, 2421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, X.Z.; Hennig, R.; Adrian, T.E. Lipoxygenase and cyclooxygenase metabolism: new insights in treatment and chemoprevention of pancreatic cancer. Mol Cancer. 2003, 2, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schneider, C.; Pozzi, A. Cyclooxygenases and lipoxygenases in cancer. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2011, 30, 277–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaikh, S.R.; Edidin, M. Polyunsaturated fatty acids and membrane organization: elucidating mechanisms to balance immunotherapy and susceptibility to infection. Chem Phys Lipids. 2008, 153, 24–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lone, A.M.; Taskn, K. Proinflammatory and immunoregulatory roles of eicosanoids in T cells. Front Immunol. 2013, 4, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, B.A.; Buettner, G.R.; Burns, C.P. Free radical-mediated lipid peroxidation in cells: oxidizability is a function of cell lipid bis-allylic hydrogen content. Biochemistry. 1994, 33, 4449–4453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shchepinov, M.S. Polyunsaturated fatty acid deuteration against neurodegeneration. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2020, 41, 236–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, S.C.W.; Furman, R.; Axelsen, P.H.; Shchepinov, M.S. Free radical chain reactions and polyunsaturated fatty acids in brain lipids. ACS Omega. 2022, 7, 25337–25345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaudoin-Chabot, C.; Wang, L.; Smarun, A.V.; Vidovi, D.; Shchepinov, M.S.; Thibault, G. Deuterated polyunsaturated fatty acids reduce oxidative stress and extend the lifespan of C. elegans. Front Physiol. 2019, 10, 641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- James, G.; Bohannan, W.; Adewunmi, E.; Schmidt, K.; Park, H.G.; Shchepinov, M.S.; Agbaga, M.P.; Brenna, J.T. Pharmacokinetics and metabolism in mouse retina of bis-allylic deuterated docosahexaenoic acid (D-DHA), a new dry AMD drug candidate. Exp Eye Res. 2022, 222, 109193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, L.J.; Zhang, J.H.; Gomez, H.; Murugan, R.; Hong, X.; Xu, D.; Jiang, F.; Peng, Z.Y. Reactive oxygen species-induced lipid peroxidation in apoptosis, autophagy, and ferroptosis. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2019, 2019, 5080843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volinsky, R.; Cwiklik, L.; Jurkiewicz, P.; Hof, M.; Jungwirth, P.; Kinnunen, P.K. Oxidized phosphatidylcholines facilitate phospholipid flip-flop in liposomes. Biophys J. 2011, 101, 1376–1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volinsky, R.; Kinnunen, P.K. Oxidized phosphatidylcholines in membrane-level cellular signaling: from biophysics to physiology and molecular pathology. FEBS J. 2013, 280, 2806–2816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIntosh, T.J. Organization of skin stratum corneum extracellular lamellae: diffraction evidence for asymmetric distribution of cholesterol. Biophys J. 2003, 85, 1675–1681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryant, G.; Taylor, M.B.; Darwish, T.A.; Krause-Heuer, A.M.; Kent, B.; Garvey, C.J. Effect of deuteration on the phase behaviour and structure of lamellar phases of phosphatidylcholines - Deuterated lipids as proxies for the physical properties of native bilayers. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 2019, 177, 196–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Xian, W.J.; Gao, Y.; Jiang, S.; Yu, Q.H.; Zheng, Q.C.; Zhang, Y. Higd1a protects cells from lipotoxicity under high-fat exposure. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2019, 2019, 6051262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valero, T. Mitochondrial biogenesis: pharmacological approaches. Curr Pharm Des. 2014, 20, 5507–5509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, J.; Xu, Y.; Zhao, S.; Xiong, L.; Jing, J.; Lui, S.; Huang, J.; Shi, H. The biological impact of deuterium and therapeutic potential of deuterium-depleted water. Front Pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1431204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahnt, A.S.; Schebb, N.H.; Steinhilber, D. Formation of lipoxins and resolvins in human leukocytes. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 2023, 166, 106726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chandrasekharan, J.A.; Sharma-Walia, N. Lipoxins: nature’s way to resolve inflammation. J nflamm Res. 2015, 8, 181–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Bell, B.A.; Song, Y.; Zhang, K.; Anderson, B.; Axelsen, P.H.; Bohannan, W.; Agbaga, M.P.; Park, H.G.; James, G.; Brenna, J.T.; Schmidt, K.; Dunaief, J.L.; Shchepinov, M.S. Deuterated docosahexaenoic acid protects against oxidative stress and geographic atrophy-like retinal degeneration in a mouse model with iron overload. Aging Cell. 2022, 21, e13579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karra, L.; Haworth, O.; Priluck, R.; Levy, B.D.; Levi-Schaffer, F. Lipoxin B promotes the resolution of allergic inflammation in the upper and lower airways of mice. Mucosal Immunol. 2015, 8, 852–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chi, J.; Cheng, J.; Wang, S.; Li, C.; Chen, M. Promising anti-inflammatory tools: biomedical efficacy of lipoxins and their synthetic pathways. Int J Mol Sci. 2023, 24, 13282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Navratil, A.R.; Shchepinov, M.S.; Dennis, E.A. Lipidomics reveals dramatic physiological kinetic isotope effects during the enzymatic oxygenation of polyunsaturated fatty acids ex vivo. J Am Chem Soc. 2018, 140, 235–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean, A.M.; Dean, F.M. Carbocations in the synthesis of prostaglandins by the cyclooxygenase of PGH synthase? A radical departure! Protein Sci. 1999, 8, 1087–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elharram, A.; Czegledy, N.M.; Golod, M.; Milne, G.L.; Pollock, E.; Bennett, B.M.; Shchepinov, M.S. Deuterium-reinforced polyunsaturated fatty acids improve cognition in a mouse model of sporadic Alzheimer’s disease. FEBS J. 2017, 284, 4083–4095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, L.J. 2nd, Milne, G.L. Isoprostanes. J Lipid Res. 2009, 50, S219–S223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raefsky, S.M.; Furman, R.; Milne, G.; Pollock, E.; Axelsen, P.; Mattson, M.P.; Shchepinov, M.S. Deuterated polyunsaturated fatty acids reduce brain lipid peroxidation and hippocampal amyloid-peptide levels, without discernable behavioral effects in an APP/PS1 mutant transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2018, 66, 165–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

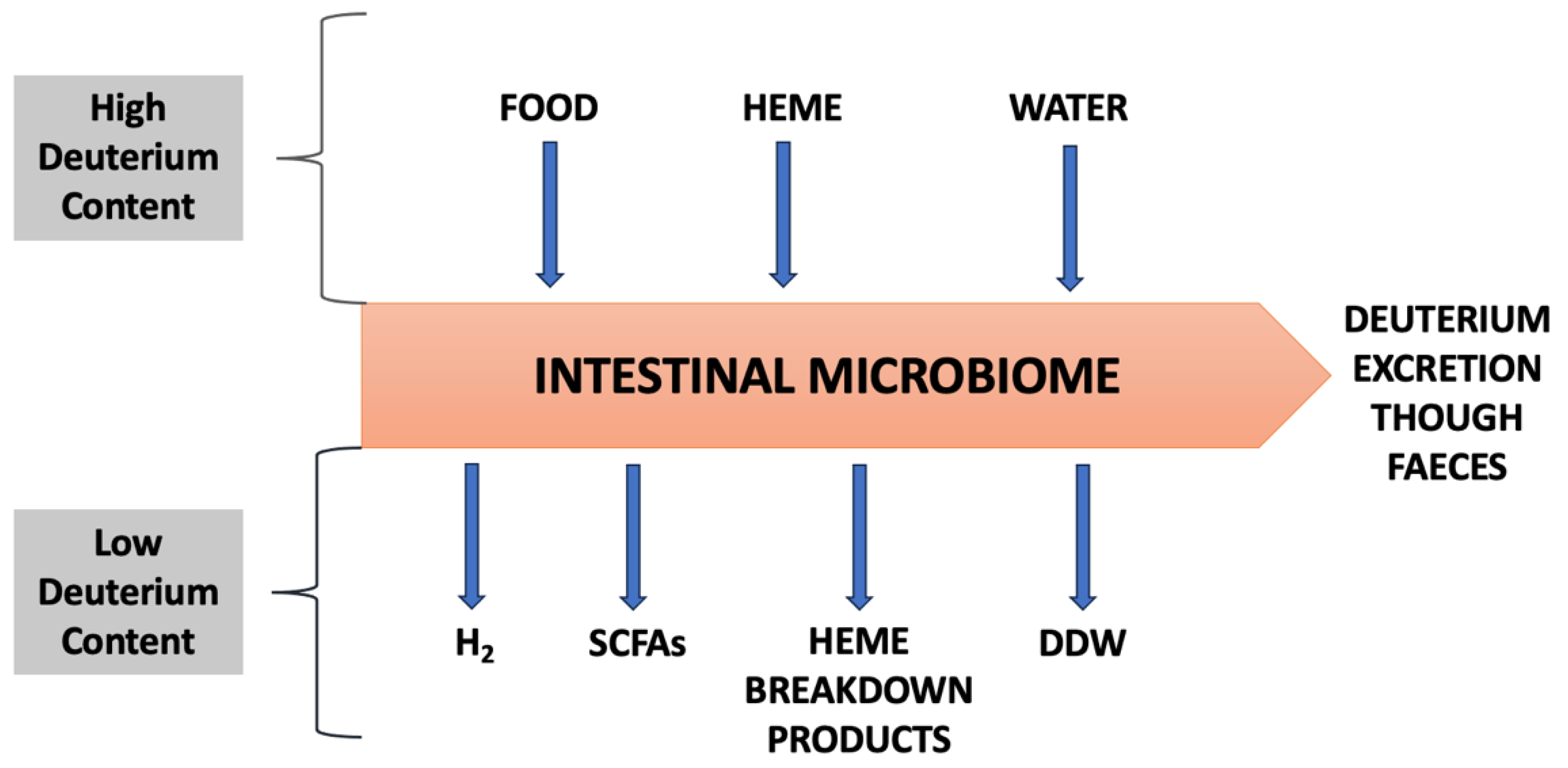

- Seneff, S.; Kyriakopoulos, A.M. Cancer, deuterium, and gut microbes: A novel perspective. Endocrine and Metabolic Science 2025, 17, 100215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batta, A.K.; Tint, G.S.; Shefer, S.; Abuelo, D.; Salen, G. Identification of 8-dehydrocholesterol (cholesta-5,8-dien-3 beta-ol) in patients with Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome. J Lipid Res. 1995, 36, 705–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheveleva, N.N.; Markelov, D.A.; Vovk, M.A.; Tarasenko, I.I.; Mikhailova, M.E.; Ilyash, M.Y.; Neelov, I.M.; Lahderanta, E. Stable deuterium labeling of histidine-rich lysine-based dendrimers. Molecules. 2019, 24, 2481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miyagi, M.; Nakazawa, T. Significance of histidine hydrogen-deuterium exchange mass spectrometry in protein structural biology. Biology (Basel). 2024, 13, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cebo, M.; Kielmas, M.; Adamczyk, J.; Cebrat, M.; Szewczuk, Z.; Stefanowicz, P. Hydrogen-deuterium exchange in imidazole as a tool for studying histidine phosphorylation. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2014, 406, 8013–8020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullangi, V.; Zhou, X.; Ball, D.W.; Anderson, D.J.; Miyagi, M. Quantitative measurement of the solvent accessibility of histidine imidazole groups in proteins. Biochemistry. 2012, 51, 7202–7208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiorani, M.; Del Vecchio, L.E.; Dargenio, P.; Kaitsas, F.; Rozera, T.; Porcari, S.; Gasbarrini, A.; Cammarota, G.; Ianiro, G. Histamine-producing bacteria and their role in gastrointestinal disorders. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023, 17, 709–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, C.; Major, A.; Rendon, D.; Lugo, M.; Jackson, V.; Shi, Z.; Mori-Akiyama, Y.; Versalovic, J. Histamine H2 Receptor-Mediated Suppression of Intestinal Inflammation by Probiotic Lactobacillus reuteri. mBio. 2015, 6, e01358–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thangam, E.B.; Jemima, E.A.; Singh, H.; Baig, M.S.; Khan, M.; Mathias, C.B.; Church, M.K.; Saluja, R. The role of histamine and histamine receptors in mast cell-mediated allergy and inflammation: the hunt for new therapeutic targets. Front Immunol. 2018, 9, 1873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akin, C. Mast cell activation syndromes. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 2017, 140, 349–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillespie, E.; Levine, R.J.; Malawista, S.E. Histamine release from rat peritoneal mast cells: inhibition by colchicine and potentiation by deuterium oxide. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 1968, 164, 158–165. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Venskutonytė, R.; Koh, A.; Stenström, O.; Khan, M.T.; Lundqvist, A.; Akke, M.; Bäckhed, F.; Lindkvist-Petersson, K. Structural characterization of the microbial enzyme urocanate reductase mediating imidazole propionate production. Nat Commun. 2021, 12, 1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koh, A.; Molinaro, A.; Ståhlman, M.; Khan, M.T.; Schmidt, C.; Mannerås-Holm, L.; Wu, H.; Carreras, A.; Jeong, H.; Olofsson, L.E.; Bergh, P.O.; Gerdes, V.; Hartstra, A.; de Brauw, M.; Perkins, R.; Nieuwdorp, M.; Bergström, G.; Bäckhed, F. Microbially produced imidazole propionate impairs insulin signaling through mTORC1. Cell. 2018, 175, 947–961.e17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaw, L.M. The insulin receptor substrate (IRS) proteins: at the intersection of metabolism and cancer. Cell Cycle. 2011, 10, 1750–1756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Liu, G.; Guo, J.; Su, Z. The PI3K/AKT pathway in obesity and type 2 diabetes. Int J Biol Sci. 2018, 14, 1483–1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molinaro, A.; Bel Lassen, P.; Henricsson, M.; Wu, H.; Adriouch, S.; Belda, E. , et al. Imidazole propionate is increased in diabetes and associated with dietary patterns and altered microbial ecology. Nat Commun. 2020, 11, 5881, Erratum in: Nat Commun. 2020 Dec 21; 11(1): 6448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alili, R.; Belda, E.; Fabre, O.; Pelloux, V.; Giordano, N.; Legrand, R.; Bel Lassen, P.; Swartz, T.D.; Zucker, J.D.; Clment, K. Characterization of the gut microbiota in individuals with overweight or obesity during a real-world weight loss dietary program: a focus on the Bacteroides 2 enterotype. Biomedicines. 2021, 10, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebelos, E.; Bucci, M.; Karjalainen, T.; Oikonen, V.; Bertoldo, A.; Hannukainen, J.C.; Virtanen, K.A.; Latva-Rasku, A.; Hirvonen, J.; Heinonen, I.; Parkkola, R.; Laakso, M.; Ferrannini, E.; Iozzo, P.; Nummenmaa, L.; Nuutila, P. Insulin resistance is associated with enhanced brain glucose uptake during euglycemic hyperinsulinemia: a large-scale PET cohort. Diabetes Care. 2021, 44, 788–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figley, C.R. Lactate transport and metabolism in the human brain: implications for the astrocyte-neuron lactate shuttle hypothesis. J Neurosci 2011, 31, 4768–4770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Choudhury, G.R.; Winters, A.; Prah, J.; Lin, W.; Liu, R.; Yang, S.-H. Hyperglycemia alters astrocyte metabolism and inhibits astrocyte proliferation. Aging and Disease 2018, 9, 674–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Wang, B.; Dong, J.; Li, Y.; Zhang, S.; Zeng, X.; Xiao, H.; Fan, S.; Cui, M. Gut microbiota-derived l-histidine/imidazole propionate axis fights against the radiation-induced cardiopulmonary injury. Int J Mol Sci. 2021, 22, 11436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, P.; Zhang, X.; Liu, N.; Tang, L.; Peng, C.; Chen, X. Pyroptosis: mechanisms and diseases. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2021, 6, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.E.; Lee, J.Y.; Yoo, D.H.; Park, H.H.; Choi, E.J.; Nam, K.H.; Park, J.; Choi, J.K. Imidazole propionate ameliorates atopic dermatitis-like skin lesions by inhibiting mitochondrial ROS and mTORC2. Front Immunol. 2024, 15, 1324026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lv, D.; Zheng, W.; Zhang, Z.; Lin, Z.; Wu, K.; Liu, H.; Liao, X.; Sun, Y. Microbial imidazole propionate affects glomerular filtration rate in patients with diabetic nephropathy through association with HSP90α. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Res. 2024, 1871, 119703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruze, R.; Liu, T.; Zou, X.; Song, J.; Chen, Y.; Xu, R.; Yin, X.; Xu, Q. Obesity and type 2 diabetes mellitus: connections in epidemiology, pathogenesis, and treatments. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2023, 14, 1161521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arumugam, M.; Raes, J.; Pelletier, E.; Le Paslier, D.; Yamada, T.; Mende, D.R. , et al. Enterotypes of the human gut microbiome. Nature. 2011, 473, 174–180, Erratum in: Nature. 2011 Jun 30; 474(7353): 666Erratum in: Nature. 2014 Feb 27;506(7489):516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramirez, J.; et al. Antibiotics as major disruptors of gut microbiota. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2020, 10, 572912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, S.H.; Nguyen Ngoc Minh, C.; de Sessions, P.F.; Jie, S.; Tran Thi Hong, C.; Thwaites, G.E.; Baker, S.; Pham, D.T.; Chung The, H. The impact of antibiotics on the gut microbiota of children recovering from watery diarrhoea. NPJ Antimicrob Resist. 2024, 2, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panda, S.; El khader, I.; Casellas, F.; Lpez Vivancos, J.; Garca Cors, M.; Santiago, A.; Cuenca, S.; Guarner, F.; Manichanh, C. Short-term effect of antibiotics on human gut microbiota. PLoS One. 2014, 9, e95476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, S.; Hollis, A. The effect of antibiotic usage on resistance in humans and food-producing animals: a longitudinal, One Health analysis using European data. Front Public Health. 2023, 11, 1170426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrillo-Larco, R.M.; Anza-Ramírez, C.; Saal-Zapata, G.; Villarreal-Zegarra, D.; Zafra-Tanaka, J.H.; Ugarte-Gil, C.; Bernabé-Ortiz, A. Type 2 diabetes mellitus and antibiotic-resistant infections: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2022, 76, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunaevsky, Y.E.; Tereshchenkova, V.F.; Oppert, B.; Belozersky, M.A.; Filippova, I.Y.; Elpidina, E.N. Human proline specific peptidases: a comprehensive analysis. Biochim Biophys Acta Gen Subj. 2020, 1864, 129636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mateos, B.; Conrad-Billroth, C.; Schiavina, M.; Beier, A.; Kontaxis, G.; Konrat, R.; Felli, I.C.; Pierattelli, R. The ambivalent role of proline residues in an intrinsically disordered protein: from disorder promoters to compaction facilitators. J Mol Biol. 2020, 432, 3093–3111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, W.J.; Raleigh, D.P. Local control of peptide conformation: stabilization of cis proline peptide bonds by aromatic proline interactions. Biopolymers. 1998, 45, 381–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maguire, O.R.; Taylor, B.; Higgins, E.M.; Rees, M.; Cobb, S.L.; Simpkins, N.S.; Hayes, C.J.; O’Donoghue, A.C. Unusually high α-proton acidity of prolyl residues in cyclic peptides. Chem Sci. 2020, 11, 7722–7729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuccinardi, T.; Rizzolio, F. Editorial: Peptidyl-prolyl isomerases in human pathologies. Front Pharmacol. 2019, 10, 794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Wu, Y.R.; Yang, H.Y.; Li, X.Z.; Jie, M.M.; Hu, C.J.; Wu, Y.Y.; Yang, S.M.; Yang, Y.B. Prolyl isomerase Pin1: a promoter of cancer and a target for therapy. Cell Death Dis. 2018, 9, 883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sletten, M.R.; Schoenheimer, R. The metabolism of 1(-)-proline studied with the aid of deuterium and isotopic nitrogen. J Biol Chem 1944, 153, 113–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gharibi, H.; Chernobrovkin, A.L.; Eriksson, G.; Saei, A.A.; Timmons, Z.; Kitchener, A.C.; Kalthoff, D.C.; Lidn, K.; Makarov, A.A.; Zubarev, R.A. Abnormal (hydroxy)proline deuterium content redefines hydrogen chemical mass. J Am Chem Soc. 2022, 144, 2484–2487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, G.; Berger, E.; Bang, H. Kinetic beta-deuterium isotope effects suggest a covalent mechanism for the protein folding enzyme peptidylprolyl cis/trans-isomerase. FEBS Lett. 1989, 250, 267–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joo, S.H. Cyclic peptides as therapeutic agents and biochemical tools. Biomol Ther (Seoul). 2012, 20, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramadhani, D.; Maharani, R.; Gazzali, A.M.; Muchtaridi, M. Cyclic peptides for the treatment of cancers: a review. Molecules. 2022, 27, 4428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guan, J.; Li, F.; Kang, D.; Anderson, T.; Pitcher, T.; Dalrymple-Alford, J.; Shorten, P.; Singh-Mallah, G. Cyclic glycine-proline (cGP) normalises insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) function: clinical significance in the ageing brain and in age-related neurological conditions. Molecules. 2023, 28, 1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guan, J.; Krishnamurthi, R.; Waldvogel, H.J.; Faull, R.L.; Clark, R.; Gluckman, P. N-terminal tripeptide of IGF-1 (GPE) prevents the loss of TH positive neurons after 6-OHDA induced nigral lesion in rats. Brain Res. 2000, 859, 286–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva-Reis, S.C.; Sampaio-Dias, I.E.; Costa, V.M.; Correia, X.C.; Costa-Almeida, H.F.; Garca-Mera, X.; Rodrguez-Borges, J.E. Concise overview of glypromate neuropeptide research: from chemistry to pharmacological applications in neurosciences. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2023, 14, 554–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Molecule | Chemical Formula | # Hydrogens |

|---|---|---|

| biliverdin | C33H34N4O6 | 34 |

| bilirubin | C33H36N4O6 | 36 |

| mesobilirubin | C33H40N4O6 | 40 |

| urobilin | C33H42N4O6 | 42 |

| urobilinogen | C33H44N4O6 | 44 |

| stercobilin | C33H46N4O6 | 46 |

| stercobilinogen | C33H48N4O6 | 48 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).