Submitted:

25 January 2025

Posted:

27 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animal Experiments

2.2. Plasmids and Cloning

2.3. Generation of Bovine iPSCs

2.4. Small Interfering RNA Sequencing

2.5. Culturing Bovine iPSCs

2.6. Alkaline Phosphatase Staining

2.7. Quantitative Real-Time PCR (qRT-PCR) Analysis

2.8. Immunofluorescence Staining

2.9. Embryoid body (EB) Formation

2.10. Teratoma Formation

2.11. Measurement of Reactive Oxygen Species

2.12. Analysis of Mitochondrial Membrane Potential

2.13. Western Blot

2.14. RNA-Seq Sample Collection and Library Preparation

2.15. ChIP-seq Sample Collection and Library Preparation

2.16. RNA-Seq and ChIP-Seq Data Analysis

2.17. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. MBD3 KD Promotes Reprogramming, Pluripotency, and Differentiation Potential of Bovine iPSCs

3.2. MBD3 KD Reduce DNA Damage Indicated by Reduction of γH2AX but Not RAD51 and BRCA1 During Bovine iPSCs Reprogramming

3.3. ROS Level Was Reduced by MBD3 KD to Avoid DNA Damage in Bovine iPSCs

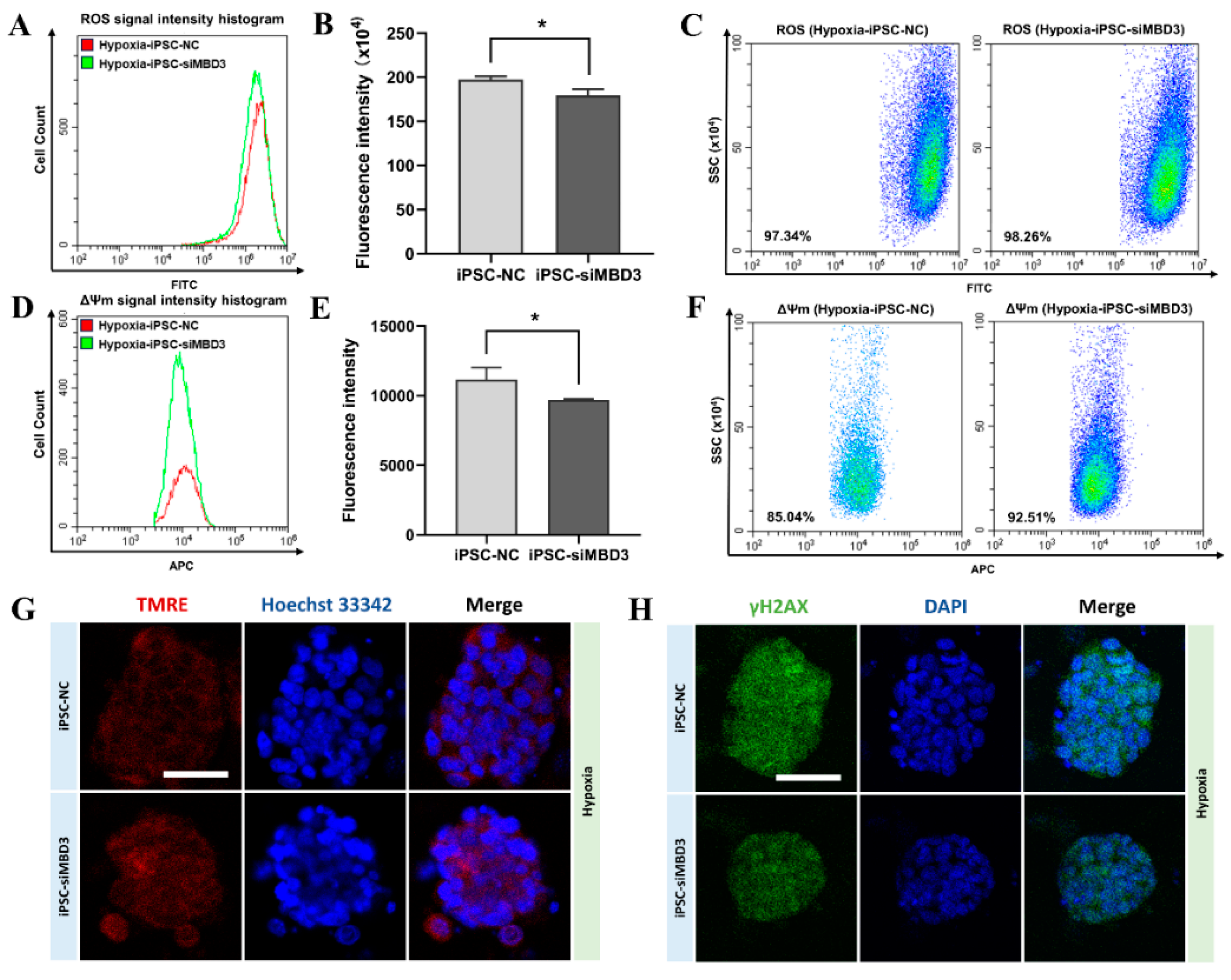

3.4. ROS Produced by Oxidative Stress in Bovine iPSCs Under Hypoxia Condition Was Reduced by MBD3 KD

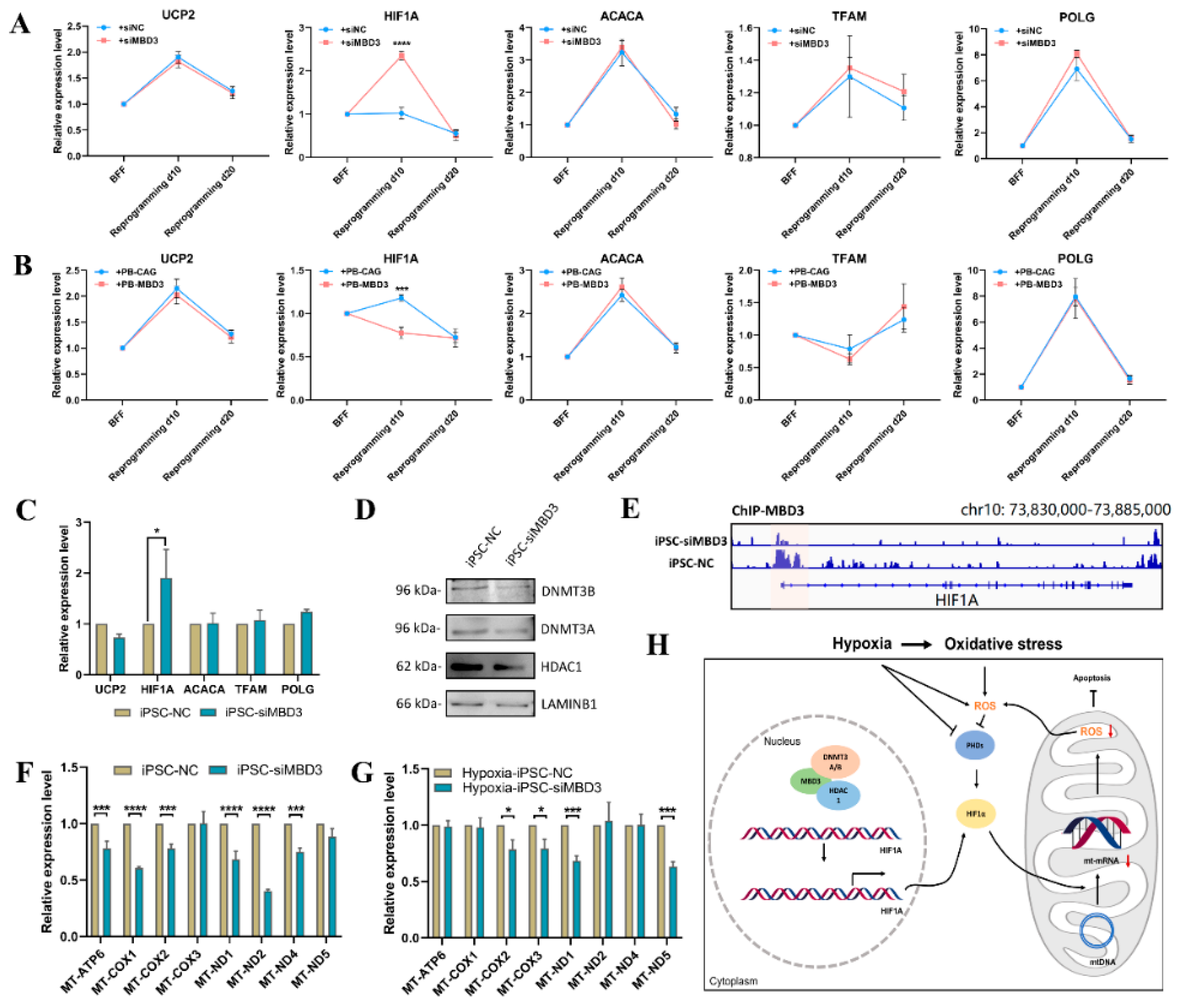

3.5. HIF1A Expression Was Increased by MBD3 KD to Resist ROS Generated by Oxidative Stress in Bovine iPSCs

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| OSKC | OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, C-MYC |

| MBD3 | methyl-CpG binding domain protein |

| NuRD | nucleosome remodeling and deacetylase |

| HIF1A | hypoxia-inducible factor 1A |

| LCDM | recombinant human LIF, CHIR99021, (S)-(+)-dimethindene maleate, and minocycline hydrochloride |

| iPSCs | induced pluripotent stem cells |

| AP | alkaline phosphatase |

| ESCs | embryonic stem cells |

| EB | embryoid body |

| qRT-PCR | quantitative real-time PCR |

| PCA | principal component analysis |

| GO | Gene Ontology |

| GSEA | Gene Set Enrichment Analysis |

| PL | placental lactogen |

| EpiSCs | epiblast stem cells |

| FBS | fetal bovine serum |

| BFFs | bovine fetal fibroblast |

| ROS | reactive oxygen species |

| DDR | DNA damage response |

| DSBs | double-strand breaks |

| γH2AX | phosphorylated form of H2AX |

| TMRE | tetramethylrhodamine |

References

- Takahashi, K.; Yamanaka, S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell 2006, 126, 663–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaffer, S.; Goh, P.; Abbasian, M.; Nathwani, A. C. Mbd3 Promotes Reprogramming of Primary Human Fibroblasts. International journal of stem cells 2018, 11, 235–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leighton, G.; Williams, D. C. The Methyl-CpG-Binding Domain 2 and 3 Proteins and Formation of the Nucleosome Remodeling and Deacetylase Complex. J Mol Biol 2020, 432, 1624–1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ee, L. S.; McCannell, K. N.; Tang, Y.; Fernandes, N.; Hardy, W. R.; Green, M. R.; Chu, F.; Fazzio, T. G. An Embryonic Stem Cell-Specific NuRD Complex Functions through Interaction with WDR5. Stem Cell Reports 2017, 8, 1488–1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaji, K.; Nichols, J.; Hendrich, B. Mbd3, a component of the NuRD co-repressor complex, is required for development of pluripotent cells. Development 2007, 134, 1123–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.; Sun, J.; He, N.; An, L.; Hou, C.; Du, F. Nucleosome remodeling and deacetylation complex and MBD3 influence mouse embryonic stem cell naive pluripotency under inhibition of protein kinase C. Cell Death Discov 2022, 8, 344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rais, Y.; Zviran, A.; Geula, S.; Gafni, O.; Chomsky, E.; Viukov, S.; Mansour, A. A.; Caspi, I.; Krupalnik, V.; Zerbib, M.; Maza, I.; Mor, N.; Baran, D.; Weinberger, L.; Jaitin, D. A.; Lara-Astiaso, D.; Blecher-Gonen, R.; Shipony, Z.; Mukamel, Z.; Hagai, T.; Gilad, S.; Amann-Zalcenstein, D.; Tanay, A.; Amit, I.; Novershtern, N.; Hanna, J. H. Deterministic direct reprogramming of somatic cells to pluripotency. Nature 2013, 502, 65–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mor, N.; Rais, Y.; Sheban, D.; Peles, S.; Aguilera-Castrejon, A.; Zviran, A.; Elinger, D.; Viukov, S.; Geula, S.; Krupalnik, V.; Zerbib, M.; Chomsky, E.; Lasman, L.; Shani, T.; Bayerl, J.; Gafni, O.; Hanna, S.; Buenrostro, J. D.; Hagai, T.; Masika, H.; Vainorius, G.; Bergman, Y.; Greenleaf, W. J.; Esteban, M. A.; Elling, U.; Levin, Y.; Massarwa, R.; Merbl, Y.; Novershtern, N.; Hanna, J. H. Neutralizing Gatad2a-Chd4-Mbd3/NuRD Complex Facilitates Deterministic Induction of Naive Pluripotency. Cell Stem Cell 2018, 23, 412–425.e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- dos Santos, R. L.; Tosti, L.; Radzisheuskaya, A.; Caballero, I. M.; Kaji, K.; Hendrich, B.; Silva, J. C. MBD3/NuRD facilitates induction of pluripotency in a context-dependent manner. Cell Stem Cell 2014, 15, 102–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ming, J.; Lin, L.; Li, J.; Wu, L.; Fang, S.; Huang, T.; Fu, Y.; Liu, D.; Zhang, W.; Li, C.; Yang, Y.; Huang, Y.; Qin, Y.; Kuang, J.; Huang, X.; Guo, L.; Zhang, X.; Liu, J.; Chen, J.; Zhao, C.; Wang, B.; Pei, D. Cell fate decision by a morphogen-transcription factor-chromatin modifier axis. Nature communications 2024, 15, 6365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Li, C.; Ming, J.; Wu, L.; Fang, S.; Huang, Y.; Lin, L.; Liu, H.; Kuang, J.; Zhao, C.; Huang, X.; Feng, H.; Guo, J.; Yang, X.; Guo, L.; Zhang, X.; Chen, J.; Liu, J.; Zhu, P.; Pei, D. The NuRD complex cooperates with SALL4 to orchestrate reprogramming. Nature communications 2023, 14, 2846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tubbs, A.; Nussenzweig, A. Endogenous DNA Damage as a Source of Genomic Instability in Cancer. Cell 2017, 168, 644–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouwman, B. A. M.; Crosetto, N. , Endogenous DNA Double-Strand Breaks during DNA Transactions: Emerging Insights and Methods for Genome-Wide Profiling. Genes (Basel) 2018, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, S. P.; Bartek, J. , The DNA-damage response in human biology and disease. Nature 2009, 461, 1071–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neganova, I.; Vilella, F.; Atkinson, S. P.; Lloret, M.; Passos, J. F.; von Zglinicki, T.; O'Connor, J. E.; Burks, D.; Jones, R.; Armstrong, L.; Lako, M. , An important role for CDK2 in G1 to S checkpoint activation and DNA damage response in human embryonic stem cells. Stem Cells 2011, 29, 651–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, E. H.; Yoon, S.; Koh, Y. E.; Seo, Y. J.; Kim, K. P. , Maintenance of genome integrity and active homologous recombination in embryonic stem cells. Exp Mol Med 2020, 52, 1220–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zalzman, M.; Falco, G.; Sharova, L. V.; Nishiyama, A.; Thomas, M.; Lee, S. L.; Stagg, C. A.; Hoang, H. G.; Yang, H. T.; Indig, F. E.; Wersto, R. P.; Ko, M. S. , Zscan4 regulates telomere elongation and genomic stability in ES cells. Nature 2010, 464, 858–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abd El-Hafeez, A. A.; Sun, N.; Chakraborty, A.; Ear, J.; Roy, S.; Chamarthi, P.; Rajapakse, N.; Das, S.; Luker, K. E.; Hazra, T. K.; Luker, G. D.; Ghosh, P. , Regulation of DNA damage response by trimeric G-proteins. iScience 2023, 26, 105973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathieu, J.; Zhou, W.; Xing, Y.; Sperber, H.; Ferreccio, A.; Agoston, Z.; Kuppusamy, K. T.; Moon, R. T.; Ruohola-Baker, H. , Hypoxia-inducible factors have distinct and stage-specific roles during reprogramming of human cells to pluripotency. Cell Stem Cell 2014, 14, 592–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Choi, M.; Margineantu, D.; Margaretha, L.; Hesson, J.; Cavanaugh, C.; Blau, C. A.; Horwitz, M. S.; Hockenbery, D.; Ware, C.; Ruohola-Baker, H. , HIF1alpha induced switch from bivalent to exclusively glycolytic metabolism during ESC-to-EpiSC/hESC transition. EMBO J 2012, 31, 2103–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathieu, J.; Zhang, Z.; Nelson, A.; Lamba, D. A.; Reh, T. A.; Ware, C.; Ruohola-Baker, H. , Hypoxia induces re-entry of committed cells into pluripotency. Stem Cells 2013, 31, 1737–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, P.; Zhang, P.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, L.; Cui, G.; Guo, X.; Wang, H.; Zhang, X.; Shi, Y.; Yu, Z. , HIF-1alpha/Actl6a/H3K9ac axis is critical for pluripotency and lineage differentiation of human induced pluripotent stem cells. FASEB J 2020, 34, 5740–5753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, X.; Duan, S.; Yi, F.; Ocampo, A.; Liu, G. H.; Izpisua Belmonte, J. C. , Mitochondrial regulation in pluripotent stem cells. Cell Metab 2013, 18, 325–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sena, L. A.; Chandel, N. S. , Physiological roles of mitochondrial reactive oxygen species. Mol Cell 2012, 48, 158–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiang, J.; Wang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, J.; Liu, F.; Han, X.; Lu, Z.; Li, C.; Li, Z.; Gao, Y.; Tian, Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, X. , LCDM medium supports the derivation of bovine extended pluripotent stem cells with embryonic and extraembryonic potency in bovine-mouse chimeras from iPSCs and bovine fetal fibroblasts. FEBS J 2021, 288, 4394–4411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, D.; Langmead, B.; Salzberg, S. L. , HISAT: a fast spliced aligner with low memory requirements. Nature methods 2015, 12, 357–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson, M. D.; McCarthy, D. J.; Smyth, G. K. , edgeR: a Bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics (Oxford, England) 2010, 26, 139–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, G.; Wang, L. G.; Han, Y.; He, Q. Y. , clusterProfiler: an R package for comparing biological themes among gene clusters. Omics : a journal of integrative biology 2012, 16, 284–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Durbin, R. , Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics (Oxford, England) 2009, 25, 1754–1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, T.; Meyer, C. A.; Eeckhoute, J.; Johnson, D. S.; Bernstein, B. E.; Nusbaum, C.; Myers, R. M.; Brown, M.; Li, W.; Liu, X. S. , Model-based analysis of ChIP-Seq (MACS). Genome biology 2008, 9, R137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shao, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Yuan, G. C.; Orkin, S. H.; Waxman, D. J. , MAnorm: a robust model for quantitative comparison of ChIP-Seq data sets. Genome biology 2012, 13, R16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, G.; Wang, L. G.; He, Q. Y. , ChIPseeker: an R/Bioconductor package for ChIP peak annotation, comparison and visualization. Bioinformatics (Oxford, England) 2015, 31, 2382–2383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanna, J.; Saha, K.; Pando, B.; van Zon, J.; Lengner, C. J.; Creyghton, M. P.; van Oudenaarden, A.; Jaenisch, R. , Direct cell reprogramming is a stochastic process amenable to acceleration. Nature 2009, 462, 595–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, J.; Yang, J.; Gao, X.; Wu, B.; Zhao, G.; Bao, S.; Hu, S.; Liu, P.; Li, X. , Characterization of the single-cell derived bovine induced pluripotent stem cells. Tissue & cell 2017, 49, 521–527. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, L.; Gao, X.; Zheng, Y.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, G.; Ren, J.; Zhang, J.; Wu, J.; Wu, B.; Chen, Y.; Sun, W.; Li, Y.; Su, J.; Ding, Y.; Gao, Y.; Liu, M.; Bai, X.; Sun, L.; Cao, G.; Tang, F.; Bao, S.; Liu, P.; Li, X. , Establishment of bovine expanded potential stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2021, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogliotti, Y. S.; Wu, J.; Vilarino, M.; Okamura, D.; Soto, D. A.; Zhong, C.; Sakurai, M.; Sampaio, R. V.; Suzuki, K.; Izpisua Belmonte, J. C.; Ross, P. J. , Efficient derivation of stable primed pluripotent embryonic stem cells from bovine blastocysts. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2018, 115, 2090–2095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, A. C. H.; Peng, Q.; Fong, S. W.; Lee, K. C.; Yeung, W. S. B.; Lee, Y. L. , DNA Damage Response and Cell Cycle Regulation in Pluripotent Stem Cells. Genes (Basel) 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, J.; Lv, W.; Ye, X.; Wang, L.; Zhang, M.; Yang, H.; Okuka, M.; Zhou, C.; Zhang, X.; Liu, L.; Li, J. , Zscan4 promotes genomic stability during reprogramming and dramatically improves the quality of iPS cells as demonstrated by tetraploid complementation. Cell Res 2013, 23, 92–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawamura, T.; Suzuki, J.; Wang, Y. V.; Menendez, S.; Morera, L. B.; Raya, A.; Wahl, G. M.; Izpisua Belmonte, J. C. , Linking the p53 tumour suppressor pathway to somatic cell reprogramming. Nature 2009, 460, 1140–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marion, R. M.; Strati, K.; Li, H.; Murga, M.; Blanco, R.; Ortega, S.; Fernandez-Capetillo, O.; Serrano, M.; Blasco, M. A. , A p53-mediated DNA damage response limits reprogramming to ensure iPS cell genomic integrity. Nature 2009, 460, 1149–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sies, H. , Oxidative stress: a concept in redox biology and medicine. Redox Biol 2015, 4, 180–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Gong, W.; Wu, S.; Perrett, S. , Hsp70 in Redox Homeostasis. Cells 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H. S.; Zhou, Y. N.; Li, L.; Li, S. F.; Long, D.; Chen, X. L.; Zhang, J. B.; Feng, L.; Li, Y. P. , HIF-1alpha protects against oxidative stress by directly targeting mitochondria. Redox Biol 2019, 25, 101109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Semenza, G. L. , Hypoxia-inducible factor 1: regulator of mitochondrial metabolism and mediator of ischemic preconditioning. Biochim Biophys Acta 2011, 1813, 1263–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, H. S.; Hwang, I.; Choi, K. A.; Jeong, H.; Lee, J. Y.; Hong, S. , Generation of induced pluripotent stem cells without genetic defects by small molecules. Biomaterials 2015, 39, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arvindekar, S.; Jackman, M. J.; Low, J. K. K.; Landsberg, M. J.; Mackay, J. P.; Viswanath, S. , Molecular architecture of nucleosome remodeling and deacetylase sub-complexes by integrative structure determination. Protein Sci 2022, 31, e4387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srinivas, U. S.; Tan, B. W. Q.; Vellayappan, B. A.; Jeyasekharan, A. D. , ROS and the DNA damage response in cancer. Redox Biol 2019, 25, 101084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, X.; Vikash, V.; Ye, Q.; Wu, D.; Liu, Y.; Dong, W. , ROS and ROS-Mediated Cellular Signaling. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2016, 2016, 4350965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, D. F.; Li, X. F.; Xu, H.; Wang, Z.; Liang, Q. Q.; Li, C. G.; Wang, Y. J. , Mechanism of resveratrol on the promotion of induced pluripotent stem cells. Journal of integrative medicine 2013, 11, 389–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simsek, T.; Kocabas, F.; Zheng, J.; Deberardinis, R. J.; Mahmoud, A. I.; Olson, E. N.; Schneider, J. W.; Zhang, C. C.; Sadek, H. A. , The distinct metabolic profile of hematopoietic stem cells reflects their location in a hypoxic niche. Cell Stem Cell 2010, 7, 380–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J. Y.; Wang, T. T.; Li, C.; Wang, Z. F.; Li, S.; Ma, L.; Zheng, L. L. , Semaphorin 3A-hypoxia inducible factor 1 subunit alpha co-overexpression enhances the osteogenic differentiation of induced pluripotent stem cells-derived mesenchymal stem cells in vitro. Chin Med J (Engl) 2020, 133, 301–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katagiri, N.; Hitomi, H.; Mae, S. I.; Kotaka, M.; Lei, L.; Yamamoto, T.; Nishiyama, A.; Osafune, K. , Retinoic acid regulates erythropoietin production cooperatively with hypoxia-inducible factors in human iPSC-derived erythropoietin-producing cells. Sci Rep 2021, 11, 3936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayabe, H.; Anada, T.; Kamoya, T.; Sato, T.; Kimura, M.; Yoshizawa, E.; Kikuchi, S.; Ueno, Y.; Sekine, K.; Camp, J. G.; Treutlein, B.; Ferguson, A.; Suzuki, O.; Takebe, T.; Taniguchi, H. , Optimal Hypoxia Regulates Human iPSC-Derived Liver Bud Differentiation through Intercellular TGFB Signaling. Stem Cell Reports 2018, 11, 306–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).