1. Introduction

Breast cancer is the most common cancer among women globally and a leading cause of cancer-related deaths. Data shows that more than 32000 deaths have been avoided annually in Canada due to early detection and treatment improvement [

1]. Screening mammography will reduce breast cancer mortality up to 31% according to New York Health Insurance plan trial and Swedish Two-Country trial, if screening mammography is applied to women population between 40 and 74 year [

2,

3]. After these promising results, screening mammography has spread worldwide. Screening mammography is associated with false positive lesions by identifying abnormalities that are not cancers, leading to anxiety, unnecessary testing and biopsies. Another disadvantage is the over diagnosis. Over diagnosis is about 11 to 22% and refers to the detection of cancers that would not have caused symptoms or will not lead to death during a person's lifetime. These types of indolent cancers may evolve slowly, remain dormant, meaning they would never become clinically significant [

4]. In this study we investigate the potential of spectrometric analysis of urine as a method of breast cancer metabolites detection and the ability to discriminate between cancer patients and cancer free patients. By tailoring this approach we may screen the population through urine analysis and detecting patients at risk that will require mammography and biopsy. The rate of over diagnosis and false positive may decrease offering a good impact on healthcare costs and population quality of life.

SERS profiling of urine represents an emerging liquid biopsy strategy for breast cancer diagnosis [

5,

6,

7,

8]. SERS combines high sensitivity (comparable to fluorescence emission) with the advantages of label-free molecular detection. Its rapid analysis capability and cost-effectiveness makes it particularly attractive for clinical applications [

8,

9,

10,

11]. SERS relies on the interaction of molecules with metallic nanosurfaces, resulting in the enhanced Raman signal of adsorbed species [

12]. This mechanism provides high specificity, as only molecules with strong affinities for the metal surface, such as purine metabolites, are predominantly detected, while other urine metabolites have a much lower contribution to the spectral pattern [

9,

13].

Among various biofluids, urine offers unique advantages for cancer diagnostics due to its non-invasive collection, minimal pre-processing requirements, and potential to reflect systemic metabolic changes [

13]. Despite its promise, the clinical translation of SERS-based analysis of urine has been hindered by several factors, as discussed below.

The adsorption of purine metabolites such as uric acid, hypoxanthine, and xanthine is influenced by the pH [

14] of urine, which varies between 4 and 9 [

15]. Since the pKa values of purine metabolites fall within this pH range, their protonation states and thus their affinities for the metal surface can vary, significantly affecting their SERS spectral signatures [

16,

17].

A second confounding factor for the SERS signal is represented by the dilution of urine (specific gravity), which also varies widely between 1.002 to 1.037. For most clinical markers measured in urine, the confounding effect of urine dilution is eliminated by normalization to creatinine concentration since the daily excretion of creatinine is relatively constant [

18]. To the best of our knowledge, such a normalization strategy has not yet been implemented for the SERS signal of urine.

In addition to analytical confounding factors, the clinical translation of SERS-based analysis of urine for cancer detection has also been hindered by the lack of interpretability of the SERS spectra. Indeed, there is an important overlap between the SERS bands of different purine metabolites, which impedes a clear identification of the biochemical markers that ultimately enable the classification of samples via machine learning algorithms.

In this study, we investigated the effect of pH on the SERS signal of urine, aiming to minimize spectral variability caused by pH fluctuations. We also analyzed simulated urine mixtures consisting of uric acid, hypoxanthine, xanthine and creatinine in physiological concentrations, with the aim of understanding the specific contributions of these markers on the overall SERS signal of urine at various pH values. Finally, we explored the possibility to use creatinine as an internal standard for eliminating the confounding effects of urine dilution. By establishing a standardized approach of eliminating the confounding effects of variations in urine pH and dilution and by improving the interpretability of the SERS signal of urine, this study aims to enhance the reliability of SERS spectroscopy for cancer detection and highlight its potential as a non-invasive diagnostic tool.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patient Enrolment

The study included a group of n=18 patients who were histologically confirmed with early stage breast cancer (BC) and referred to our hospital for elective surgery between 2023 and 2024. We also included a group of n=10 control subjects (CTRL) represented by female patients that had benign screening mammography in the last 12 months. All breast cancer patients were diagnosed after breast mammography detection of malignant lesion. All patients included in BC-group had proven histology of breast cancer through true-cut biopsies prior to surgery. After positive diagnosis and proper staging patients were presented to the Hospital Multidisciplinary Team (MDT) discussion. After MDT approval, upfront radical surgery was performed with no neoadjuvant treatment prior to surgery. Surgical procedure implied lumpectomy or mastectomy with sentinel lymph node biopsy. Post operatory histopathological assessment of the specimens was performed in order to confirm complete excision and evaluate the nodal status. Patients with large palpable masses, suspicious lymph nodes, neoadjuvant hormonal therapy or chemotherapy were excluded. 24 hours prior to surgical procedure, we harvested 10 ml of urine. In the CTRL group patients that underwent screening mammography and approved to participate to our study required 10 ml of urine harvested. Urine was stored at -80 degrees Celsius.

The study was approved by the Ethical Committee of the 1st Surgical Clinic, County Emergency Clinical Hospital in Cluj-Napoca, and informed consent was obtained from all patients enrolled in the study.

2.2. SERS Spectra Acquisition

The SERS spectra were obtained using a portable Raman spectrometer (Avantes) operated in a clinical setting. For each sample, three 10-second acquisitions were performed using a 532 nm laser excitation line (50 mW). Hydroxylamine hydrochloride reduced silver nanoparticles (hya-AgNPs) were employed as the SERS substrate [

19], and calcium ions (Ca²⁺) were used to enhance the SERS spectra of urine [

9]. A mixture of 45 µL of hya-AgNPs, 5 µL of urine, and 5x10⁻

3 M Ca(NO

3)

2 was prepared (final concentration of Ca

2+ was 5x10

-4 M). Subsequently, 10 µL of the mixture was placed on a microscope slide, and a Raman probe was used to acquire the SERS spectra. pH adjustments were performed on 100 µL aliquots of urine samples by adding HNO

3 and NaOH until the desired pH value was reached. Each spectrum represents an average of three acquisitions, 10 s integration time each.

2.3. Data Analysis

All data were preprocessed using the Quasar-Orange software (Bioinformatics Laboratory of the University of Ljubljana [

20]). SERS spectra were truncated in the 500–1800 cm⁻¹ range, followed by rubber band baseline correction and vector normalization. Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was performed, retaining the first principal components (PCs) that explained 95% of the cumulative variance. The explained variance is illustrated in

Supplementary Figure S1. For the analysis of unprocessed urine samples at physiological pH values, eight principal components (PCs) were retained. In contrast, for urine samples adjusted to controlled pH values, seven PCs accounted for 95% of the cumulative variance. The PCs used to depict the sample distribution were selected based on Student's t-test.

The PCs explaining 95% of the cumulative variance were then used as input for Random Forest (RF) classifiers comprising ten trees, validated through leave-one-out cross-validation.

3. Results and Disscusion

3.1. pH-Dependent SERS Spectral Variations of Urine Metabolites

The adsorption of molecules from a complex matrix like urine occurs competitively, driven by their relative affinity for the metal surface, which in turn depends on pH.

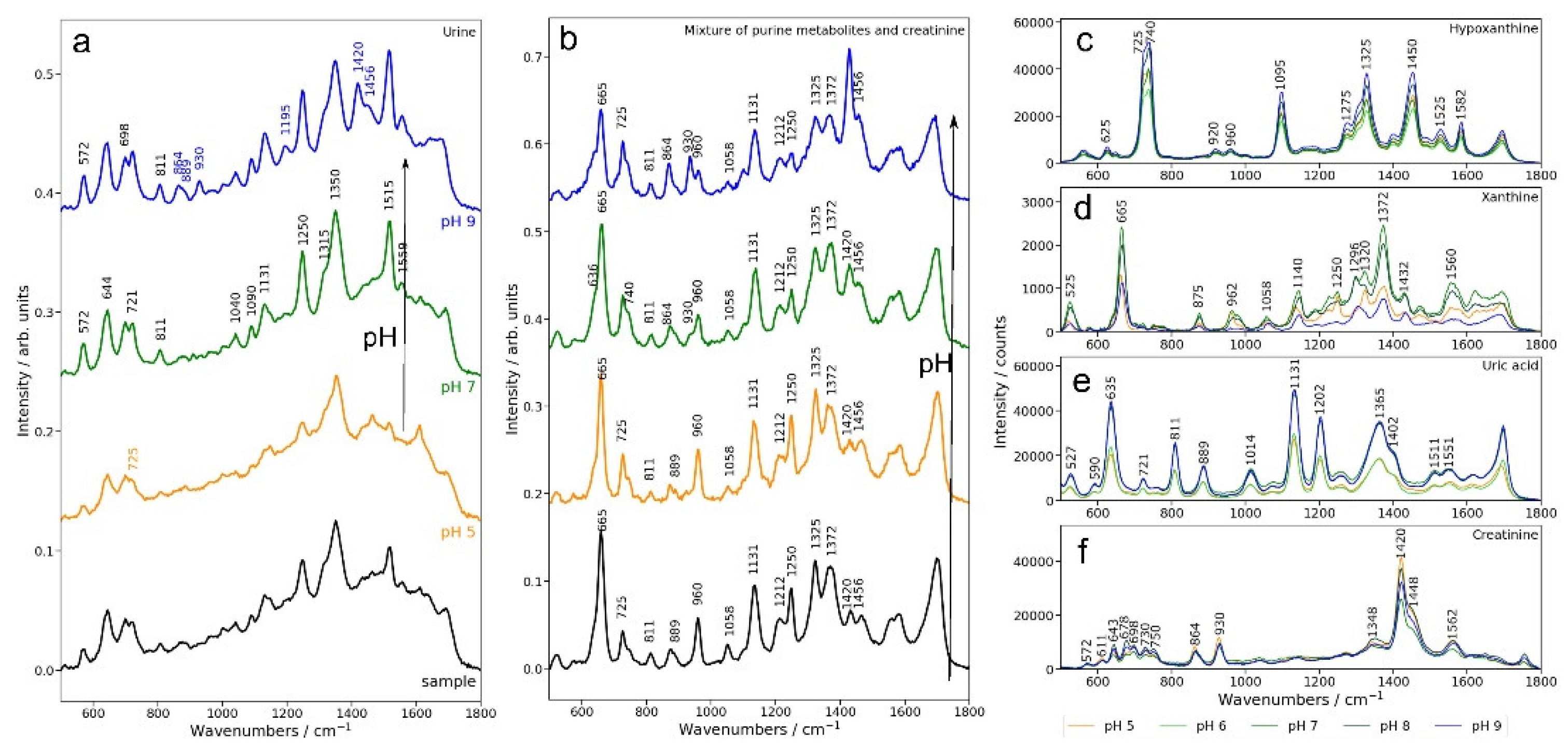

Figure 1a displays the SERS spectra of real urine samples from patients with breast cancer (n=18) and control subjects (n=10) grouped based on their initial pH (i.e. as collected). The initial pH values of the urine samples ranged from 5 to 7, consistent with the normal physiological pH range of 4–9 [

15]. The SERS spectra of urine at their initial pH highlighted main key bands corresponding to hypoxanthine (725, 1090, 1456 cm⁻¹), and lower-intensity bands associated with uric acid at 811, 889, 1131, and 1515 cm⁻¹. The comparative spectra of urine at different pH values also show that the most detailed spectral features are present under alkaline conditions (pH 9).

To better understand the assignment of the SERS bands of urine, we systematically analyzed the effect of pH on the SERS signal of simulated urine represented by a mixture of the main contributors to the SERS signal (uric acid, xanthine, hypoxanthine and creatinine) at physiologically relevant concentrations (

Figure 1b). In parallel, we analyzed the SERS signals of uric acid, xanthine, hypoxanthine, and creatinine individually across the same range of pH values (

Figure 1c–f).

Uric acid exhibited the strongest SERS signals at pH 9, consistent with the increased concentration of anionic uric acid in this pH range (

Figure 1e). This trend is also reflected in the SERS spectra of real urine (

Figure 1a) as well as in the SERS spectra of simulated urine (

Figure 1b), where the intensity of the SERS bands at 635, 811, 889, and 1131 cm⁻¹ attributed to uric acid increases progressively from pH 5 to pH 9.

Xanthine exhibited maximal SERS intensity at pH 7, with diminished signals under both acidic and alkaline conditions (

Figure 1d). In the case of urine and simulated urine, its detection in urine samples is challenging because of significant overlap with uric acid bands, particularly at 665 and 1559 cm⁻¹ (

Figure 1a,b). In simulated urine, increasing the pH results in a shift from a sharp band at 665 cm⁻¹, associated with xanthine, to a reduction of this band and the emergence of a shoulder as uric acid becomes more prominent in the SERS spectrum. A distinct band at 1250 cm⁻¹, attributed to xanthine, is also observed, which slightly decreases with higher pH in simulated urine. In contrast, in real urine, this band slightly intensifies with increasing pH (

Figure 1a).

Hypoxanthine exhibited its highest SERS intensity at pH 9 (

Figure 1c), although its spectral variations between pH 5 and 9 were relatively subtle. In real and simulated urine samples, the hypoxanthine SERS bands at 725, 740, and 1090 cm⁻¹ are well-defined across all pH values in this range (

Figure 1a). Two distinct bands, at 725 cm⁻¹ and 740 cm⁻¹, were identified, both corresponding to hypoxanthine. The 725 cm⁻¹ band is attributed to the keto tautomer, while the 740 cm⁻¹ band represents the enolic tautomer [

21]. Notably, in urine samples, the keto tautomer is predominant, which explains the absence of the 740 cm⁻¹ band in the SERS spectrum of urine (

Figure 1a) [

22].

Creatinine showed its strongest SERS signals at pH 5, with minimal variation across the pH range (

Figure 1f). However, in real and simulated urine samples, the creatinine SERS band at 1420 cm⁻¹ was only observed at pH 9, while the intensity of the SERS band at 572 cm⁻¹ increased with rising pH values.

In conclusion, for uric acid and hypoxanthine, the higher intensity of the SERS signal in real and simulated urine under alkaline conditions (pH 9) parallels the behavior of these metabolites when measured alone. In contrast, there is a disjunction between the effect of pH on the SERS intensity of creatinine bands in real or simulated urine on the one hand and creatinine alone: the SERS bands of creatinine are favored by alkaline conditions, but this is not the case for creatinine measured alone.

Thus, the observed variations in SERS signals are not solely attributable to the adsorption behavior of individual metabolites but are also influenced by competitive adsorption on the metal surface at different pH values. Colloidal nanoparticles (NPs) offer a limited adsorption surface, which is typically saturated at analyte concentrations of 10⁻⁵–10⁻⁴ M. Above this concentration metabolite adsorption becomes competitive, driven by their relative affinities for the silver surface. The protonation state, which varies with pH, plays a critical role in determining these affinities.

In the case of creatinine, the reduced intensity of the creatinine-associated bands in acidic conditions likely reflects its decreased adsorption affinity when competing with uric acid, hypoxanthine, and xanthine, which exhibit stronger affinities for the silver surface under these conditions. However, under alkaline conditions, despite the lower SERS intensity of individual creatinine, the competition dynamics shifts and in this environment, all metabolites, including creatinine, successfully adsorb onto the silver surface, becoming clearly detectable in the SERS spectrum.

3.2. Implications for Diagnostic Applications

The pH-dependent analysis of urine samples as well as of metabolites, both individually and in mixtures, revealed that pH 9 yields the most intense SERS bands, including the SERS bands of creatinine, which could be used as an internal standard to control for urine dilution. Creatinine is a convenient internal standard to control for urine dilution because the daily output in humans is relatively constant (around 1 g). Thus, we sought to explore whether bringing all urine samples to pH 9 followed by normalization to the creatinine band at 1420 cm-1 improves the classification accuracy.

Towards this end, we compared the results of the principal component analysis (PCA) performed on urine samples at their initial pH and after bringing the urine samples to fixed pH values. The results showed that the spectral differentiation between the control (CTRL) and breast cancer (BC) groups was optimal for urine samples brought to pH 5 and pH 9 (

Figures S2–S6). Given that urine samples brought to pH 9 also featured creatinine-associated SERS band suitable for normalization, we propose it as the optimal pH for SERS-based diagnostics.

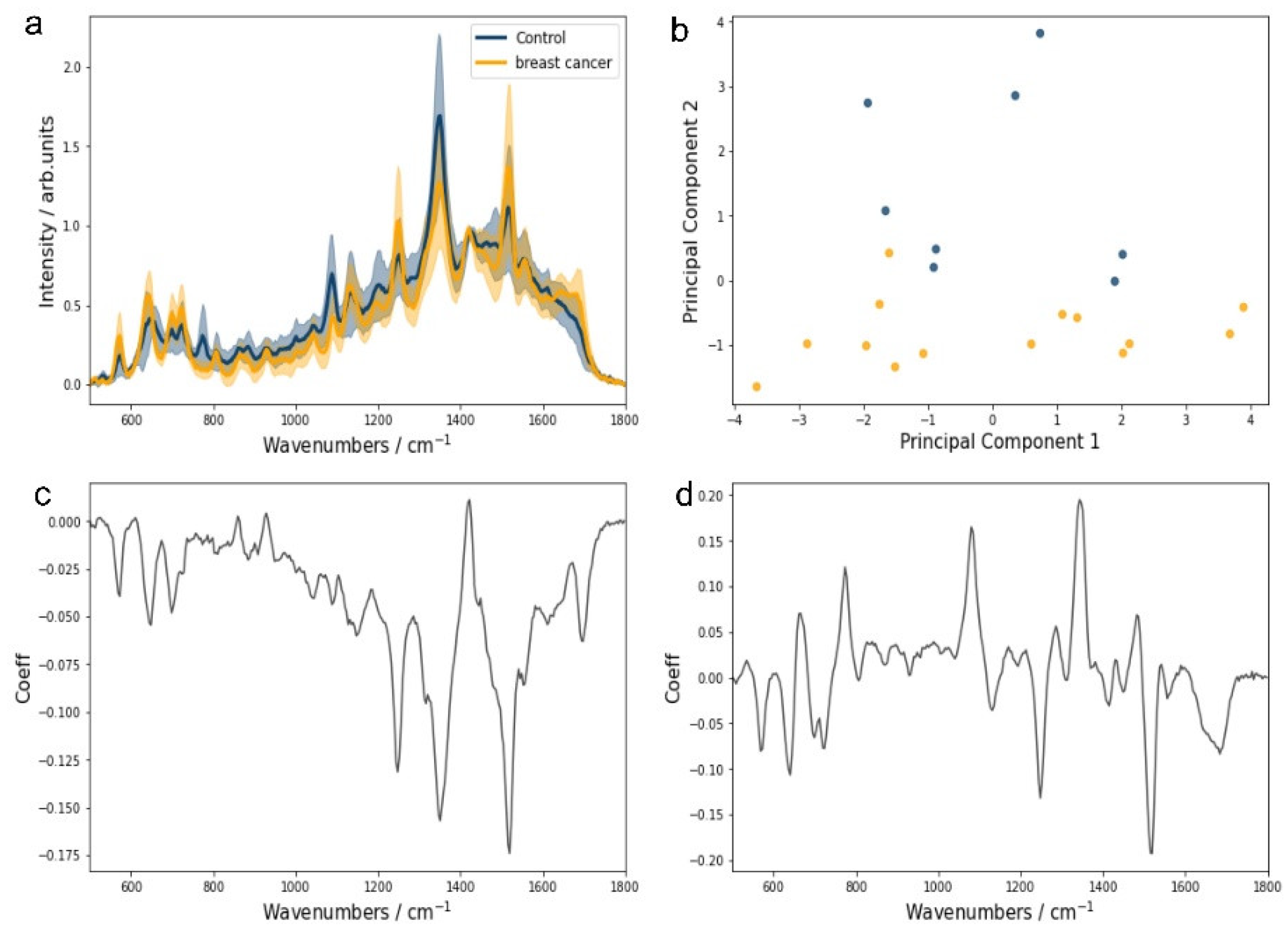

Figure 2 presents the normalized SERS spectra (relative to the 1420 cm⁻¹ creatinine band) of urine at pH 9 (

Figure 2a) and the resulting PCA scatter plot (

Figure 2b), illustrating the separation of BC and CTRL groups based on PC1 and PC2 score values (

Figure 2c,d).

The normalization of urine SERS spectra to the creatinine band at 1420 cm⁻¹ evidenced significant differences between CTRL and BC groups. Notably, the intensities of the SERS bands associated with hypoxanthine (725 cm⁻¹) and uric acid (889 and 1131 cm⁻¹) were distinct between the groups (

Figure 2a). The scatter plot of PC1 and PC2 score values indicates unsupervised grouping, primarily driven by PC2 (

Figure 2b). The loading plot for PC2 score values shows a negative correlation with SERS bands at 774, 1080, and 1334 cm⁻¹, which were unassignable to the purine metabolites analyzed in this study and were more prevalent in the CTRL group (

Figure 2b,c). Conversely, bands associated with uric acid and xanthine were more pronounced in the BC group, highlighting their potential diagnostic relevance.

Next, we investigated whether adjusting all urine samples to pH 9 followed by normalization to creatinine would optimize classification accuracy. To assess this, the first five PCs from each pH condition were used as input for a Random Forest (RF) classifier. The results indicated a trend of increasing classification accuracy with higher pH levels (

Supplementary Table S1). Correction to pH 9 combined with normalization to the creatinine band at 1420 cm⁻¹ achieved the best performance, with a classification accuracy of 92.9% (

Table 1).

Additionally, PCA of the SERS spectra of urine acquired at pH 9, followed by normalization to creatinine, captured the highest proportion of cumulative variance within the first five PCs (

Figure S7).

A notable limitation of this study is the small sample size, which precluded robust external validation of the RF models. However, the head-to-head comparison of PCA and RF model results provided valuable evidence supporting the critical role of pH adjustment and normalization to creatinine bands in enhancing SERS-based diagnostic tools for breast cancer. Validation of these findings in larger cohorts is warranted.

4. Conclusions

This study underscores the clinical potential of surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy (SERS) as a non-invasive tool for breast cancer detection through urine analysis. By addressing key challenges such as pH variability and urine dilution, we demonstrated that urine at pH 9 yields the most detailed and diagnostically valuable spectral features. The significant contributions of metabolites like hypoxanthine, uric acid, and creatinine to the SERS signal at this optimal pH enhance the method's sensitivity and specificity. Normalizing the SERS spectra to the creatinine band effectively mitigates dilution effects, leading to improved classification accuracy with machine learning models, particularly random forest algorithms. These findings pave the way for integrating SERS into clinical workflows, potentially reducing reliance on more invasive procedures like biopsies and lowering the rates of overdiagnosis and false positives in breast cancer screening. Further validation with larger, diverse patient cohorts will be essential to confirm these results and fully realize the potential of SERS-based urine analysis as a practical, cost-effective liquid biopsy tool in oncology.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Figure S1: Cumulative explained variance for samples, pH 5 (B) pH 7(C) pH 9 (D); Figure S2: Supplementary

Figure 2. Mean SERS spectra of Control and Breast cancer patients with standard deviations at the real pH value of the samples: pH 5 (C), pH 7 (E), pH 9 (G), and the scatter plot of the significant PCs for the discrimination of the two groups at normal pH (B), pH 5 (D), pH 7 (F), and pH 9 (H). For the physiological pH, PC2 was found to be significant (p = 0.007). For pH 7, PC1 (p = 0.0002) and PC2 (p = 0.03) were significant. For pH 5, PC2 (p = 0.02) and PC5 (p = 0.001) were significant. For pH 9, PC1 was significant (p = 0.0001); Figure S3: Loading plot of Principal Component 1 (A) and PC 2 (B) from the PCA analysis of sample at their initial pH values; Figure S4: Loading plot of Principal Component 1 (A) and PC 2 (B) from the PCA analysis of sample at pH 5; Figure S5: Loading plot of Principal Component 1 (A), PC 2 (B) and PC7 ()C from the PCA analysis of sample at pH 7; Figure S6: Loading plot of Principal Component 1 (A) and PC 2 (B) from the PCA analysis of sample at pH 9; Figure S7: Cumulative explained variance for samples at pH 9 normalized to creatinine; Table S1: Classification performance of the Random Forest classifier for control and breast cancer samples, evaluated using SERS spectra of urine measured at native pH and adjusted pH levels of 5, 7, and 9.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.A., N.L., and S.D.I.; methodology, D.A., V.M., N.L., and S.D.I.; software, R.G.C.; validation, D.A., N.L., and S.D.I.; formal analysis, R.G.C., M.D., G.C., G.C.D., V.B.; investigation, R.G.C., M.D.; resources, D.A., G.C.D., N.L.; data curation, V.M.; writing—original draft preparation, D.A., R.G.C., G.C.; writing—review and editing D.A.,V.M., V.B., G.C.D., N.L., S.D.I.; visualization, R.G.C., M.D.; supervision, D.A., N.L.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by Iuliu Hatieganu University of Medicine and Pharmacy Cluj-Napoca, Romania, Doctoral Research Project no.4107/01.10.2017 and by the Romanian Ministry of Research and Innovation, CCCDI-UEFISCDI, project number PN-IV-P2-2.1-TE-2023-0342.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by the Ethical Committee of the 1st Surgical Clinic, County Emergency Clinical Hospital in Cluj-Napoca, and informed consent was obtained from all patients enrolled in the study.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| SERS |

Surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy |

| hya-AgNPs |

Hydroxylamine hydrochloride reduced silver nanoparticles |

| PCA |

Principal Component Analysis |

| PCs |

principal components |

| RF |

Random Forest |

| NPs |

Colloidal nanoparticles |

References

- Society, C.C., Canadian Cancer Society’s Advisory Committee on Cancer Statistics. Canadian Cancer Statistics 2016. 2016: Toronto, ON.

- Tabár, L., et al., Reduction in mortality from breast cancer after mass screening with mammography. Randomised trial from the Breast Cancer Screening Working Group of the Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare. Lancet, 1985. 1(8433): p. 829-32.

- Shapiro, S., et al., Selection, follow-up, and analysis in the Health Insurance Plan Study: a randomized trial with breast cancer screening. Natl Cancer Inst Monogr, 1985. 67: p. 65-74.

- Dunn, B.K., et al., Cancer overdiagnosis: a challenge in the era of screening. J Natl Cancer Cent, 2022. 2(4): p. 235-242. [CrossRef]

- Bonifacio, A., et al., Surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy of blood plasma and serum using Ag and Au nanoparticles: a systematic study. Anal Bioanal Chem, 2014. 406(9-10): p. 2355-65. [CrossRef]

- Vázquez-Iglesias, L., et al., SERS sensing for cancer biomarker: Approaches and directions. Bioactive Materials, 2024. 34: p. 248-268. [CrossRef]

- Liu, X., Y. Jia, and C. Zheng, Recent progress in Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy detection of biomarkers in liquid biopsy for breast cancer. Front Oncol, 2024. 14: p. 1400498. [CrossRef]

- Moisoiu, V., et al., Breast Cancer Diagnosis by Surface-Enhanced Raman Scattering (SERS) of Urine. Applied Sciences, 2019. 9(4): p. 806. [CrossRef]

- Moisoiu, V., et al., SERS liquid biopsy: An emerging tool for medical diagnosis. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces, 2021. 208: p. 112064. [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y., L. Lin, and J. Ye, Human metabolite detection by surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy. Materials Today Bio, 2022. 13: p. 100205. [CrossRef]

- Phyo, J.B., et al., Label-Free SERS Analysis of Urine Using a 3D-Stacked AgNW-Glass Fiber Filter Sensor for the Diagnosis of Pancreatic Cancer and Prostate Cancer. Analytical Chemistry, 2021. 93(8): p. 3778-3785. [CrossRef]

- Le Ru, E.C. and P.G. Etchegoin, Chapter 4 - SERS enhancement factors and related topics, in Principles of Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy, E.C. Le Ru and P.G. Etchegoin, Editors. 2009, Elsevier: Amsterdam. p. 185-264.

- Iancu, S.D., et al., SERS liquid biopsy in breast cancer. What can we learn from SERS on serum and urine? Spectrochim Acta A Mol Biomol Spectrosc, 2022. 273: p. 120992. [CrossRef]

- Lu, D., et al., pH-Adjusted Liquid SERS Approach: Toward a Reliable Plasma-Based Early Stage Lung Cancer Detection. Analytical Chemistry, 2024.

- Cook, J.D., et al., Urine pH: the effects of time and temperature after collection. J Anal Toxicol, 2007. 31(8): p. 486-96. [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, J., K. Mukherjee, and T.N. Misra, pH dependent Surface enhanced Raman scattering study of Hypoxanthine. J. Raman Spectrosc.31, 427 (2000). 2000. 31. [CrossRef]

- Muniz-Miranda, F., A. Pedone, and M. Muniz-Miranda, Raman and Computational Study on the Adsorption of Xanthine on Silver Nanocolloids. ACS Omega, 2018. 3(10): p. 13530-13537. [CrossRef]

- Selistre, L., et al., Average creatinine–urea clearance: revival of an old analytical technique? Clinical Kidney Journal, 2023. 16(8): p. 1298-1306. [CrossRef]

- Leopold, N. and B. Lendl, A New Method for Fast Preparation of Highly Surface-Enhanced Raman Scattering (SERS) Active Silver Colloids at Room Temperature by Reduction of Silver Nitrate with Hydroxylamine Hydrochloride. The Journal of Physical Chemistry B, 2003. 107(24): p. 5723-5727. [CrossRef]

- Toplak, M., et al., Quasar: Easy Machine Learning for Biospectroscopy. 2021. 10(9): p. 2300. [CrossRef]

- Huang, W., et al., Density functional theory and surface enhanced Raman spectroscopy studies of tautomeric hypoxanthine and its adsorption behaviors in electrochemical processes. Electrochimica Acta, 2015. 164: p. 132-138. [CrossRef]

- Araujo de Oliveira, A.P., C.A. Wegermann, and A.M.D.C. Ferreira, Keto-enol tautomerism in the development of new drugs. Frontiers in Chemical Biology, 2024. 3. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).