1. Introduction

Inappropriate use of antimicrobials is magnified in the context of low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), where there are not only the formal means to access antimicrobials through doctor prescriptions but also multiple informal channels, such as over-the-counter sales, self-medication, sharing of prescriptions and medicines with friends and families and through quacks (Jonas et al., 2017; Otaigbe and Elikwu, 2023; Velazquez-Meza et al., 2022). This multiplicity brings diverse socio-cultural implications in shaping processes of prescribing, dispensing, and consumption of antimicrobials. These implications play out within institutional and regulatory frameworks and shape the efficacy of their implementation (Lim et al., 2020; Mukherjee et al., 2024). Understanding these multiple socio-cultural-institutional implications in conjunction with biomedical information made visible by the prescription slip provides the basis to develop a unified “biosocial” perspective on the nature and determinants of antimicrobial prescriptions.

Our primary unit of analysis is the prescription slip, which has historically played a key role in defining medical practice and structuring the doctor-patient relationship. In LMIC settings, the prescription also structures the patient’s relationship with multiple others such as the pharmacist, who often substitutes for the doctor in providing advice to patients on what drugs to consume and how (Beyene et al., 2014; Ganesh Kumar et al., 2013; Ryan et al., 2014; Saleh et al., 2015). These relationships help shape access to therapeutics and allow for explorations of information and power asymmetries between doctors, patients, and pharmacists.

The research question that this paper pursues is “How does a biosocial approach help in understanding the nature of prescription practices and their determinants?”. Empirically, the research is conducted within the context of an ongoing research study in India.

The rest of this paper is structured as follows. After this introduction, the next section briefly proposes the biosocial approach to help analyze the antimicrobial prescribing challenge. Following this, we provide details of the research methods (section 3), and then the case study description (section 4). In section 5, we present the analysis and discussion followed by brief conclusions.

2. The “Biosocial” Approach: For Unifying the Bio and Social of Antimicrobial Prescribing

2.1. The Biosocial Approach

Current streams of research on antimicrobial prescriptions are dominated by two relatively isolated streams of studies, one primarily biomedical and the other social. The biomedical stream focuses primarily on the determinants, mutations, and emergence of diseases (Minssen et al., 2020; Wozniak et al., 2022), and in prescription studies, they seek to account for the pharmacological characteristics of antimicrobials (Muteeb et al., 2023). An example of such an approach is presented in a recent paper by Shetty, et. al. (2024) who evaluated prescriptions across multiple tertiary facilities in India and analyzed deviations from standard treatment guidelines (Shetty et al., 2024). They evaluated 4838 prescriptions for their completeness (in terms of formulation, dose, duration, and frequency of administration), and how they adhered to standard treatment guidelines (STGs) developed by the Department of Health Research, ICMR, Government of India. Further, it was argued that these deviations had implications for drug interactions, lack of response, increase in cost of treatment, preventable adverse drug reaction (ADR), and antimicrobial resistance.

While such a biomedical analysis is crucial in understanding the therapeutic efficacy of drugs, the patient is missing from the analysis, who also plays a role in shaping not only what antimicrobials are prescribed, but also their dispensing and consumption. More recently, the social stream of research seeks to analyze the social, cultural, and political determinants of diseases to address this lack. For example, (Charani, 2022, Charani et al., 2021) from their studies in India emphasized the importance of considering gender, caste, and literacy in such analysis. While this development represents an important step in incorporating the patient’s perspective, it does not adequately incorporate the biomedical aspects of the prescriptions.

Keeping these bio and social streams of research separate represents dualism, as it is the same disease in focus highlighted through the prescription slip, which has combined influences of the biomedical and social. Focusing only on one creates one-sided causality arguments, which necessarily tend to be incomplete. To overcome this dualism and create a more duality-oriented perspective, Seeberg et al (2020) have developed the concept of the “biosocial”, which reflects an anthropological understanding that the bio and social are inseparable, evolving as complex intertwined ensembles over time (Seeberg, 2020 Biosocial Worlds, n.d.). The biosocial serves as an ontological position to analyze mutual and dynamic interactions between the biological, social, and context. Seeberg (2023) develops this perspective through the example of multidrug-resistant Tuberculosis (MDR-TB), which is showing alarming levels of increase, attributed not only to the biomedical condition but more closely to living conditions, population density, environmental and sanitation conditions (Seeberg, 2023). He argues for the development of a novel research paradigm that de-separates the bio and social, towards creating a more unified knowledge basis.

We develop this concept of the biosocial to analyze the interaction between biomedical and social elements, where the biomedical is understood through the drugs specified in the prescription slips and the social through discussions and interactions with clinicians, pharmacists, and patients. These two streams of analysis are then combined to understand the “what” and “why” of prescriptions to develop a more holistic biosocial approach. This represents a unique contribution of this research, which emphasizes that antimicrobials are not fixed medical objects but embody multiple constructed rationalities within different local contexts.

2.2. The Challenge of Antimicrobial Prescribing: Culture Matters

Antimicrobial prescribing presents a paradox for healthcare provision. Unnecessary use of antimicrobials can lead to resistance, harm patients, and increasing treatment costs. Unjustified therapy with narrow-spectrum antimicrobials that ineffectively treat causative pathogens can also be detrimental to patients (Llor and Bjerrum, 2014). Excessive use of antimicrobials not only jeopardizes our ability to treat and prevent microbial infections but also puts many common medical procedures (such as C-sections) to contain fatal risks (Salam et al., 2023). The prescription slip specifies the antimicrobials to use, thus playing a crucial role in managing the risks and opportunities of antimicrobials and their efficacy for care processes. Over, under and non-optimal use of antimicrobials is shaped by social conditions, as argued by Charani (2022) as “culture matters”.

Unless we understand the socio-cultural and behavioral drivers for antimicrobial use and develop contextually fit, equitable strategies to address them, no number of new antimicrobials will cut the tide of emerging antimicrobial resistance and its spread through populations (page 1506) (8).

Cultural influences emerge from multiple sources including medical specialists, national cultural characteristics, behavioral traits, and organizational policies and practices. Liu et al. (2019, 2019b) analyzed the interconnections within a hospital setting between intrinsic and extrinsic factors, and for example, noted female doctors were less likely to prescribe antimicrobials as they were more comfortable in adopting the “wait and see” principle, while also being more likely to succumb to patient requests for antimicrobials. There are also national-level cultural differences, for example, Holland showed the lowest use of antimicrobials in Europe, while France, Belgium, Italy, and Germany were relatively higher (Cars et al., 2001). Deschepper et al. (2008) drew upon Hofstede’s (2001) model of national cultural characteristics to analyze differences in antimicrobial prescribing across 14 European countries (Deschepper et al., 2008). Countries with high uncertainty avoidance, which reflects a propensity to avoid uncertainty and risk, were more prone to prescribing antimicrobials, while Protestant societies, with values of austerity and simplicity, favored limited use of antimicrobials, while Catholic societies, more hierarchical and ritualistic, favored higher levels of antimicrobial use.

Behavioral aspects also shape antimicrobial prescribing practices. While junior doctors tended to rely more on broad-spectrum antimicrobials, senior doctors favored lower levels of prescribing. Charani (2022) highlighted differences between medical specialists and clinicians, who may want to value their expertise and experience, as well as that of their peers (Charani, 2022). Marliere et al. (2000) in their study across 6000 households in Brazil, found a widespread practice of patients storing unused drugs at home for use in future episodes of illness (Marlière et al., 2000).

In India, overuse and non-use of antimicrobials are particularly influenced by the sale of non-prescription-based antimicrobials, despite legislation against it. The Government of India’s Policy for Containment of AMR (2011) to prevent over-the-counter sales of antimicrobials and making it mandatory for pharmacists to document their transactions is weakly implemented (Kotwani et al., 2021). Similar has been the fate of the Government’s “Redline campaign” in 2016 to create public awareness of the rational use of antimicrobials to help curb self-medication. There is a current directive by the government for pharmacists to dispense antimicrobials in blue envelopes to distinguish them from other drugs. Patients, rather than getting a prescription from a doctor to access antimicrobials, adopt multiple other channels, to circumvent the prevailing regulations.

Various national-level guidelines have been developed by the National Center for Disease Control (NCDC), and the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) to guide the use of antimicrobials (

Table 1). These guidelines have been difficult to implement, given the various resources and capacity constraints, and the different socio-cultural influences in play.

We have highlighted the various biomedical and socio-cultural conditions that influence antimicrobial prescriptions. We analyze them in unison through the biosocial perspective.

3. Material and Methods

3.1. The Research Context

The Study Was designed under a larger 4-year research project, one component of which was to understand how antimicrobials prescribing shape AMR. The empirical focus was on a public health facility situated in a city in Northern India with an estimated population of 13,200, which is two-thirds rural. The population there has a literacy rate of 93.31%, higher than the state average of 82.80%, with males at higher levels than women (95.63% to 90.87%).

This study was conducted at a 50-bedded public community health center, serving 200-250 outpatients daily from the catchment population within a 4-5 km radius of the facility. The facility has a team of 13 doctors, covering ophthalmology, dentistry, medicine, dermatology, general medicine, microbiology, pediatrics, obstetrics and gynecology. The hospital provided free biochemistry lab facilities, and in 2021 established a Microbiology lab for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (AST) of urine, stool, and pus samples. There also was an Inpatient ward, which was usually vacant, except in cases of emergency or during the rainy season. The facility hosted two pharmacies (dispensary and civil), with the dispensary within their premises, open from 9 am to 4 pm, providing free notified essential drugs. The civil pharmacy, located outside the premises, provided 24/7 services and a 10-15% discount on drugs. There were multiple private pharmacies just outside the premises (see images below), where patients would buy drugs perceived to be of higher quality but more expensive.

3.2. Research Design

Ethics approvals and permissions from the Senior Medical Officer (SMO) were taken before initiating the research. The pharmacist was also oriented towards the study. The data collection was conducted by a trained Microbiologist, who was local to the area and participated in the development, pilot testing of the data collection tool, and trained in its deployment. Data collection involved multi-methods, including:

3.3. Quantitative Study of Prescription Patterns

Prescription slips were collected from patients visiting the hospital pharmacy after an OPD encounter. The researcher stood outside the pharmacy and based on a random sampling method, approached patients (irrespective of their age and gender) and after taking their verbal consent, selected their slips that included antimicrobials. About 2-3% of the patients coming to the pharmacy were approached every day during the period Aug 2022 - July 2023, to gain insights of seasonal variations.

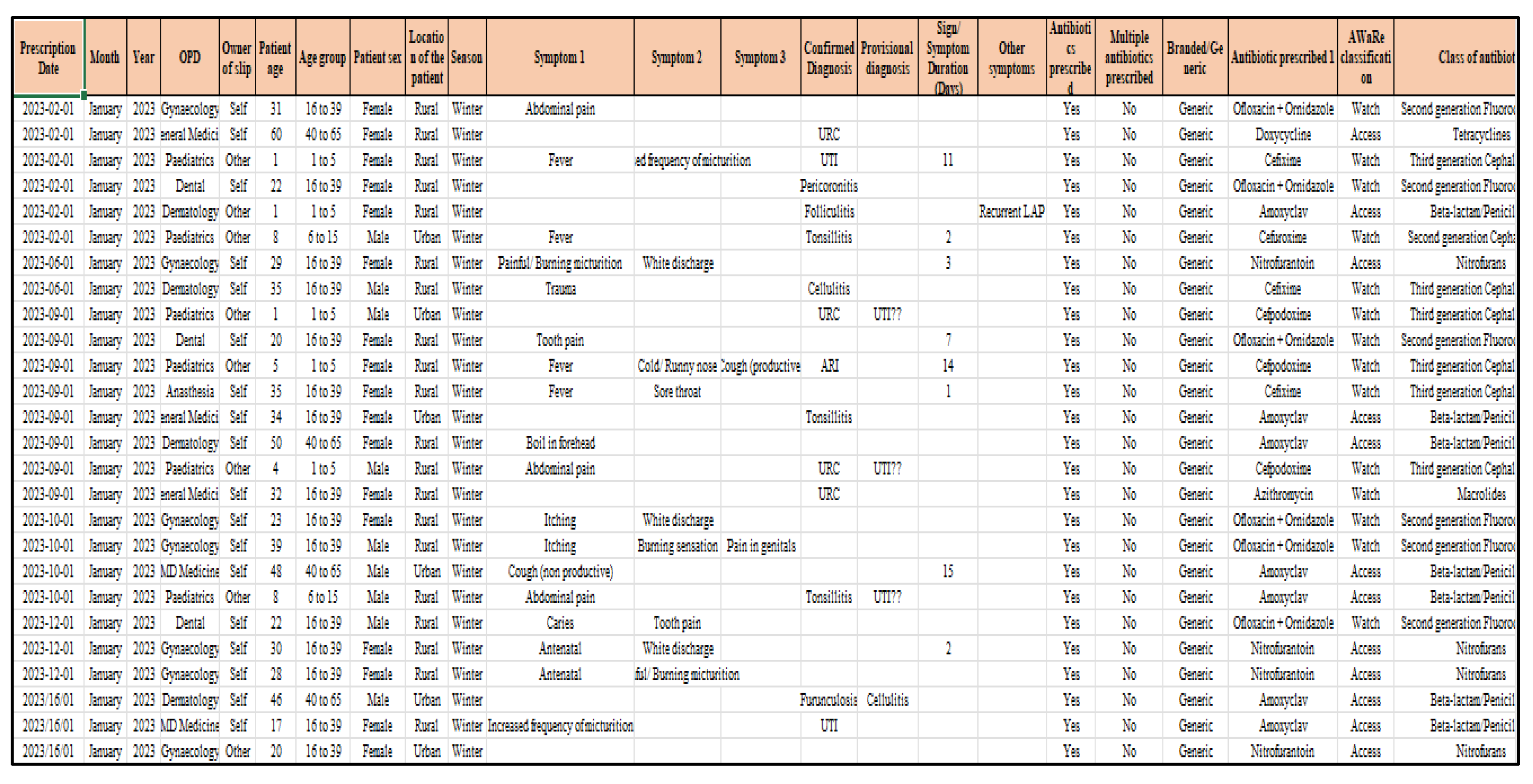

The images of selected prescriptions were captured, while anonymizing the patient’s name, by the researcher using her mobile phone. The image was then studied to extract relevant details such as prescription date, age, sex, location of residence, name of antimicrobials, whether branded, generic and if from the essential drugs list, symptoms or confirmed diagnosis, whether an AST was ordered, legibility of the doctor’s handwriting, and any other follow up notes and advise (see

Figure 1). These details were then taken into an Excel sheet and then imported into a database to develop the analytics.

3.4. Qualitative Study to Understand the “Why” of Prescriptions

Observations and discussions were carried out with patients, pharmacists, and clinicians to understand the “why” of the prescriptions, from their respective perspectives. In informal interactions with patients, we sought to understand their level of awareness about what antimicrobials were, why they believed they were prescribed, and how they should be consumed. The researcher also conducted observations of patient-pharmacist interactions, to understand the kind of queries the patient had and the responses received from the pharmacist. Issues were further discussed with 16 patients (6 males and 10 females all in the age group 25-50 years), 7 doctors (3 General Practitioners, 1 each from Dental, Microbiology. Dermatology, and Anesthesia) and 2 Pharmacists. Further, telephonic follow-ups after due consent were conducted with 9 patients who had visited the microbiology lab for a culture test and had been prescribed antimicrobials. They were asked if they had complied or not with the prescription regime, whether they had collected their test reports, and what they did with them. These different discussions and observations were recorded by the researcher in her field diary.

3.5. Data Analysis

The data analysis process, oriented toward developing a biosocial perspective on prescription practices, was conducted in three phases. The first was the phase of quantitative data analysis, to discern the biomedical patterns underlying prescribing. The data recorded in the Excel data sheet was imported into a database system, to first develop summary statistics to characterize the data, and then analyzed concerning with respect to WHO core parameters (such as the AWaRe classification average number of antimicrobials dispensed per encountered/visit, % of drugs prescribed by generic name, % of encounters with an antimicrobial prescribed), national guidelines, and other indicators such as compliance to Essential Drug Lists (EDLs). The second was the qualitative data analysis which first involved compiling all the textual data in a Word file, then the next involved the reading of this text file by the different authors to discern their respective themes which were then discussed to agree on the final themes. As a third step, the quantitative and qualitative analysis was combined to interpretively understand how the identified qualified themes could be related to the biomedical patterns discerned through the quantitative analysis. This triangulation helped to develop the biosocial perspective on prescription patterns.

4. Results

4.1. Summary Statistics

A total of 1175 patients’ prescriptions were screened (

Table 2), and their demographic features summarized (

Table 3).

4.2. Evaluation Of Antibiotic Prescription Patterns

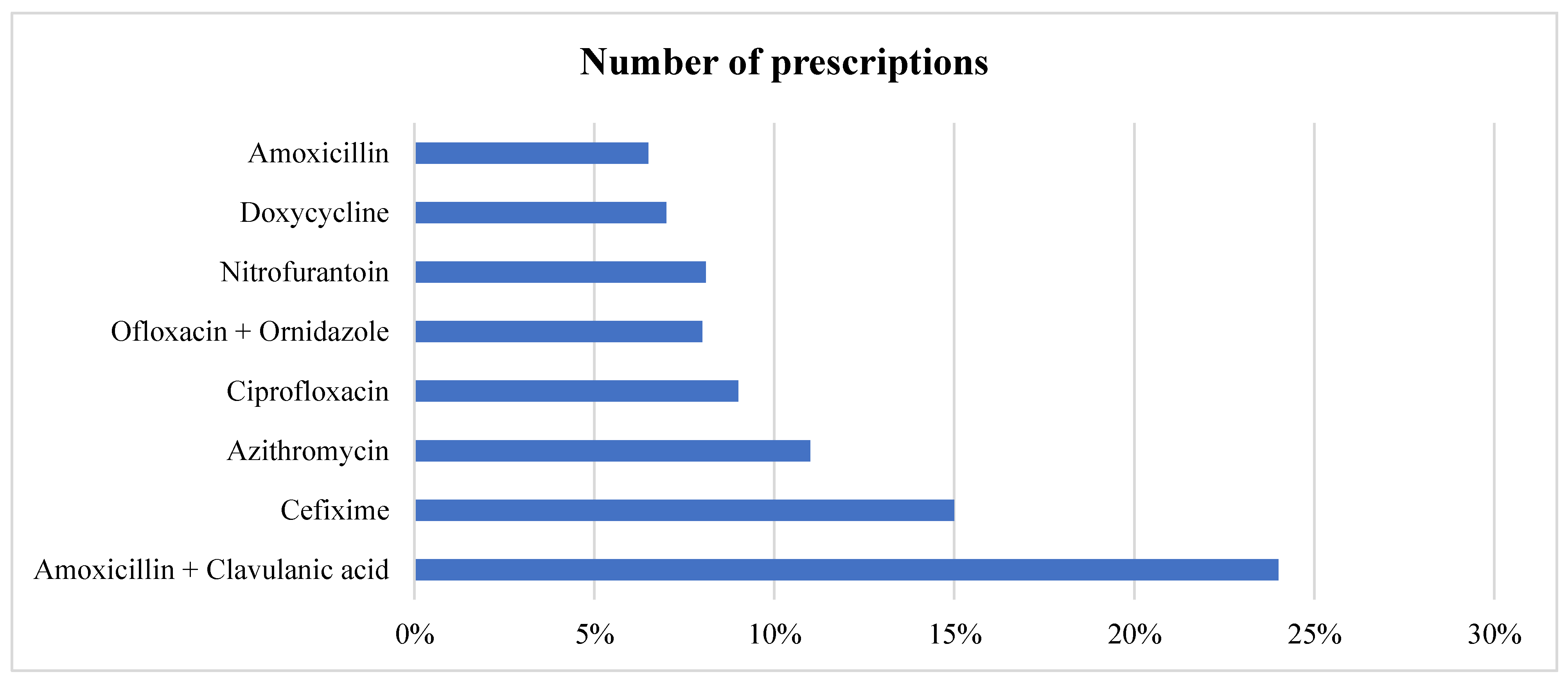

In all the prescriptions where antibiotic is prescribed, in total, 8 different antimicrobials were prescribed to various patients, with three accounting for more than 50% of prescriptions. Amoxicillin + Clavulanic acid and Cefixime were the most prescribed (24% and 15%, respectively), followed by Azithromycin given to (11%) patients. Broad-spectrum antimicrobials accounted for 852 (74.02%) of the total prescriptions as shown in

Table 4 and

Figure 2. In cases of multiple antimicrobial prescriptions, the most given second antimicrobials were Metronidazole and Cefixime. We also stratified the data based on gender. The top five antimicrobials given to female patients were Amoxicillin + Clavulanic acid, followed by Cefixime, Azithromycin, Ofloxacin + ornidazole, and Ciprofloxacin. For male patients, it was Amoxicillin + Clavulanic acid, Cefixime, Azithromycin, Ciprofloxacin, and Doxycycline.

Table 4. Distribution of Prescribed Antimicrobials by Class, Spectrum, and AWaRe Category.

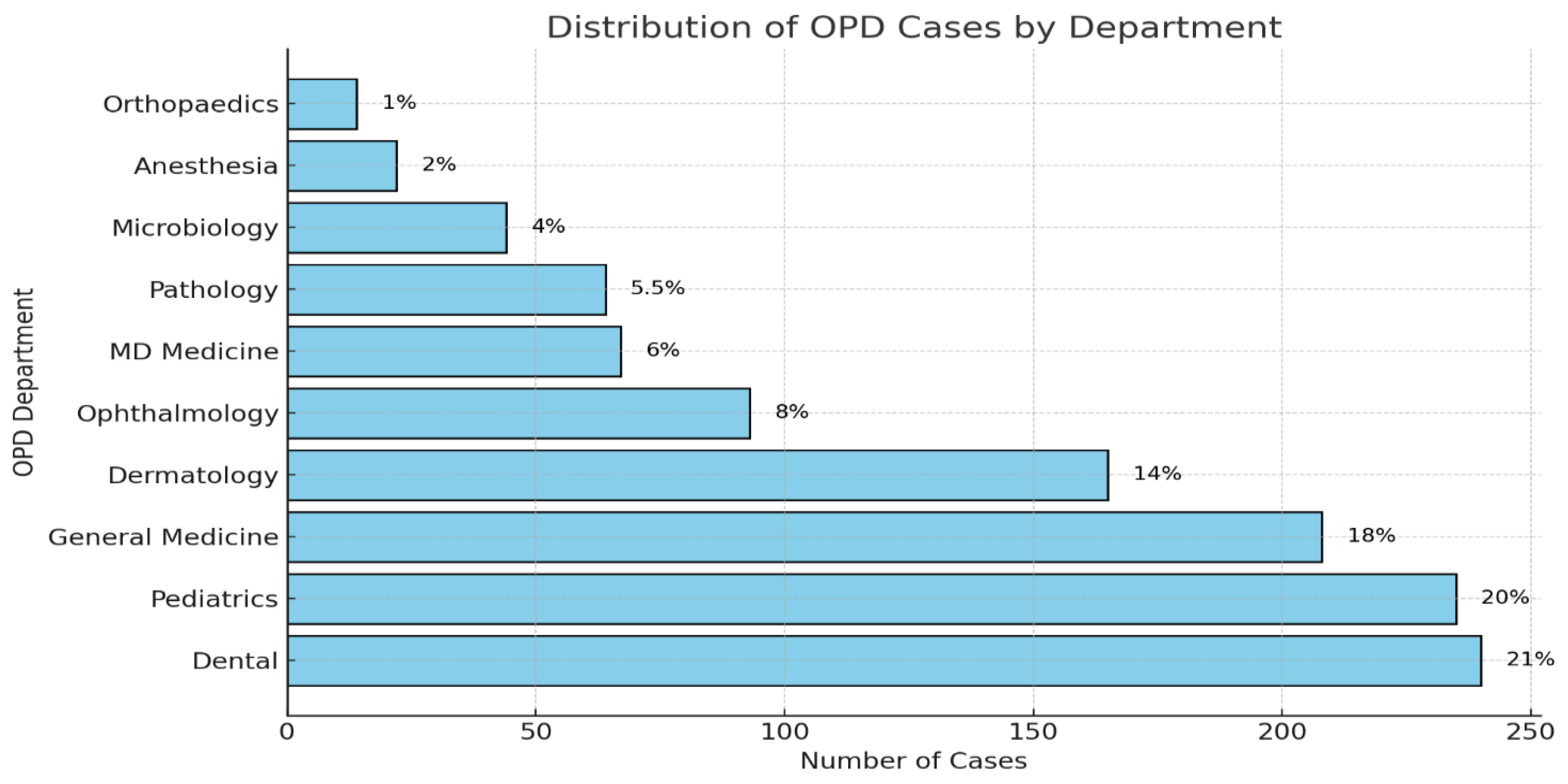

4.3. Source of Prescriptions

The Dental OPD was the biggest source of prescriptions (21%) followed by Pediatrics (20%), then General Medicine (18%), Dermatology (14%), and last was Gynecology (8%) as shown in

Figure 3.

4.4. Most Prescribed Antimicrobials for Symptomatic Treatment

We found the most common symptoms against which antimicrobials were prescribed were Dental caries, respiratory conditions like fever, Pneumonia, and other skin-related conditions like cellulitis, Acne, UTI (Urinary Tract infections), and Tonsillitis. The most prescribed antimicrobial for dental Caries was Ofloxacin + Ornidazole followed by Amoxicillin and Amoxicillin + Metronidazole. For acute respiratory conditions, Amoxicillin + clavulanic acid was the most prescribed along with Cefixime and Azithromycin. In cases of Pneumonia, it was Amoxicillin + clavulanic acid followed by Azithromycin and for UTIs, it was Cefixime syrup for children and Nitrofurantoin for adults. For Tonsillitis (Otolaryngological condition) it was Amoxicillin + clavulanic acid followed by Azithromycin and Cefixime. For skin cellulitis, it was Amoxicillin + clavulanic acid followed by Cefixime.

Table 5.

Patterns of Antimicrobial Prescription by Diagnosis, Classification, and Spectrum.

Table 5.

Patterns of Antimicrobial Prescription by Diagnosis, Classification, and Spectrum.

| S No. |

Diagnosis/ Sign/ Symptom |

Broad categorization |

Top antimicrobials prescribed for it |

Class of antimicrobial |

Broad and Narrow spectrum |

| 1. |

Caries |

Dental condition |

Ofloxacin+ornidazole |

2nd generation Fluoroquinolones

|

Broad spectrum |

| Amoxicillin |

Aminopenicillins |

Broad spectrum |

| Amoxicillin- Metronidazole |

Aminopenicillins + 2nd generation Fluoroquinolones |

Broad + Narrow spectrum |

| 2. |

ARI |

Respiratory condition |

Amoxicillin + clavulanic acid |

Aminopenicillins + Beta- lactamase |

Broad spectrum |

| Cefixime |

3rd generation Cephalosporins |

Broad spectrum |

| Azithromycin |

Macrolides |

Broad spectrum |

| 3. |

UTI |

Urogenital condition |

Cefixime

|

3rd generation Cephalosporins |

Broad spectrum |

Nitrofurantoin

|

Nitrofuran |

Broad spectrum |

| Amoxicillin + clavulanic acid |

Aminopenicillins + beta lactamase inhibitor |

Broad spectrum |

| 4. |

Tonsillitis |

Otolaryngological condition

|

Amoxicillin + clavulanic acid |

Aminopenicillins + beta lactamase inhibitor |

Broad spectrum |

| Azithromycin |

1st generation Macrolides |

Broad spectrum |

| Cefixime |

3rd generation Cephalosporins |

Broad spectrum |

| 5. |

Acne / Acne vulgaris |

Respiratory condition |

Azithromycin |

1st generation Macrolides |

Broad spectrum |

| Doxycycline |

1st generation Tetracycline |

Broad spectrum |

| 6. |

Cellulitis |

Skin condition |

Amoxicillin + clavulanic acid |

Aminopenicillins + beta- lactamase inhibitor |

Broad spectrum |

| Cefixime |

3rd generation Cephalosporins |

Broad spectrum |

| 7. |

Fever |

Respiratory condition |

Azithromycin |

1st generation Macrolides |

Broad spectrum |

| Cefixime |

3rd generation Cephalosporins |

Broad spectrum |

| Doxycycline |

1st generation Tetracyclines |

Broad spectrum |

| 8. |

Diarrhea |

Gastroenteritis |

Ciprofloxacin |

2nd generation Fluoroquinolones |

Broad spectrum |

| Ofloxacin + ornidazole |

2nd generation Fluoroquinolones |

Broad spectrum |

4.5. WHO AWaRe Classification

WHO classified antimicrobials in AWaRe (Access, Watch, and Reserve) categories. Access includes the first or second-choice antimicrobials that are most effective with the least potential for resistance. The Watch category includes the first or second-choice antimicrobials used for a limited number of infections through empirical and non-targeted therapies (Koya et al., 2022). We found 5 antimicrobials (Amoxicillin + clavulanic acid, Nitrofurantoin, Doxycycline, Amoxicillin and Metronidazole) prescribed among all the prescriptions from the Access category which accounts for 62.76% of total prescriptions and the remaining 7 Cefixime, Azithromycin, Ciprofloxacin, Ofloxacin-ornidazole, Cefpodoxime, Moxifloxacin, and Cefuroxime). Comprising 37% were from the Watch category (No antimicrobials were prescribed from the Reserve category).

4.6. Incomplete Prescriptions

Antimicrobials Sensitivity Test (AST) reports were available in only 12 cases (1%) of slips studied and there were 106 cases (9.2%) where future tests were ordered. Some prescriptions were missing details of dosage (22.15%), duration of treatment (1.91%), and frequency of administration (2.86%). The diagnosis was often not mentioned, or the writing was illegible to understand. Further, the terminologies used for categorizing different signs and symptoms or diagnoses were highly variable. For example, fever with pain abdomen, burning micturition with abdominal pain, and tooth pain with extractions were all recorded as provisional diagnoses. More than 74% of prescriptions are related to broad-spectrum antimicrobials (e.g. Amoxicillin + Clavulanic Acid, Ciprofloxacin, Doxycycline, and Cefixime), with more than 90% of patients being given antimicrobials empirically.

5. Discussion

5.1. Qualitative Data Analysis

Theme 1: Poor Understanding Amongst Patients of What Are “Antimicrobials”

Most patients said that they had no idea about “what are antimicrobials”. Some mentioned that they didn’t care about the name of the medicine if it was freely available in the hospital and was effective in curing their illness. Another patient laughed and said, “It was the job of the doctor to know about medicines and not us”. From the 16 patients interviewed, only one male and 2-3 females had heard about antimicrobials. One female patient who was asked why she had been prescribed antimicrobials for long-term pain in her teeth, said that she was unaware about how antimicrobials could help. This response was similar to the reply of another female patient who had been prescribed antimicrobials for her child. Another male patient who was having a fever and was prescribed antimicrobials said he was prescribed some medicines for fever but had no idea that they were. There was another female patient, in her mid-twenties, who we observed buying antimicrobials from the pharmacist, and when asked what she was buying, “She was buying some medicines to treat an infection, and she knew about this since a doctor, a prior acquaintance of hers, had informed her that he was prescribing antimicrobials to be taken for 5 days. These observations were similar to a study conducted in Bahir Dar City, Northwest Ethiopia, which found that only 48.5% of participants had moderate knowledge about antimicrobial resistance and usage (City et al., 2024). In an another study, Hong et al. found that at an individual level, participants faced challenges in accessing healthcare knowledge and adhering to social expectations surrounding care (Hong et al., 2024).

We found two male patients, aged about 35 and 50 years who were diagnosed with Upper Respiratory Tract Infection but had not been prescribed antimicrobials, much to their dismay and disappointment, since they believed then they would not be cured. Patients who had previously been prescribed antimicrobials for a particular health problem, built expectations that for future health episodes of all kinds, they must be given antimicrobials. Similar to this, in a global survey by the World Health Organization (WHO), found that public knowledge and awareness about antibiotic use and antimicrobial resistance were generally low, with many people holding misconceptions about the necessity and effectiveness of antibiotics for various illnesses (Id et al., 2021).

While most patients had little knowledge of what antimicrobials are or how they work, a few because of prior experience, had some basic knowledge. Some patients believed that antimicrobials were a cure for all illnesses.

Theme 2: Limited Knowledge and Awareness of Antimicrobial Prescription Among Patients

When patients were asked whether they were counseled and told by the doctors about what was being prescribed to them, most said “no” and just told them to get the medicines written on the slip from the pharmacy. One patient coming out of the dermatology department said that the doctor had told him to buy the medicines and come back to him to understand how to take the medicines”. We observed that the microbiologist and dermatologist shared a common room and talked to each other about patients, which may have resulted in the advice to patients to come back, something which was not normal practice. Often patients who were told to return after 7 days of treatment (or earlier if there was an emergency), never returned. A study in Nigeria found that many patients were not adequately counseled about their medications by doctors, similar to our observations, which potentially led to miscommunication and misuse of medications (Id et al., 2022).

In our observations of patient-pharmacist interactions, we found it interesting to note the level of trust the patient had with the pharmacist, and always solicited opinions and advice on the drugs written in the prescription slip. One patient asked the pharmacist “Can you give medicines like one for the gas (gastroenterology) problem you had previously given”. The pharmacist replied: “If you are not comfortable then you can skip these as they are not so important but do not tell the doctor that I gave you this advice”. Both shared a laugh, and the patients returned the medicines with a thank you.

Our observations clearly indicated that patients were reluctant to go back to the doctor and clarify doubts about the drugs prescribed. When asked by a pharmacist why this was the case, the patient said, “If we went back to the doctor, he would get angry, so why don’t you please tell us.” The pharmacist said “This is their (the doctor’s) work on counseling patients and not ours). But then he took their prescriptions and started telling them again about the drugs prescribed to them. Then after the patient left the pharmacist told the researcher “We do the work of the doctor also but still people will always complain about what work we have”. In one case, the patient was diagnosed with an upper respiratory tract infection and inquired with the pharmacist if they had been prescribed an antimicrobial or not. When the pharmacist replied “No”, the patient was very disappointed as he thought he would not get cured. As the patient was leaving, the researcher asked him how he knew about antimicrobials. He replied that in the past he had a similar fever and cough, and from the Primary Health Care facility, he was prescribed antimicrobials which cured him in a few days. Such tendencies have also been reported from UK where patients often turned to pharmacists for advice on medication use, especially when reluctant to approach their doctors (Bpharm and Schafheutle, 2018).

We observed an interesting difference between the parents of pediatric patients, who demanded prescriptions of branded antimicrobials from the doctors. Parents mentioned that “they can be careless in their own case and other adults in their family but preferred to buy branded antimicrobials for their children”. We saw in 71 slips from the Pediatric OPD, that branded antimicrobials were prescribed such as Amoxicillin + clavulanic acid and Cefixime syrup. Parents perceived the quality of medicines dispensed from the hospital pharmacy to be poor and so demanded branded medicines which they would procure from external pharmacies. The higher cost was not a consideration in such cases. This was also confirmed by the child specialist who prescribed branded medicines as they believed that the quality of medicines available in the hospital pharmacy was inferior to those available in the private pharmacies. To illustrate, the specialist asked the researcher to taste the Vitamin C tablets available in the hospital dispensary and compare them with those available outside. He explained that “if the taste and quality of such a basic thing is poor inside the hospital then what can we expect from the other medicines”. The physician was hesitant to share further details about the drug quality and pointed towards the political pressures involved in the tendering of drugs in the hospital, and how this affected the quality of drugs purchased.

We developed short vignettes of 9 patients whom we followed up with. In nearly all cases, we noted that when instructed by the doctor, the patient waited to get the AST report before commencing on the antimicrobials and tended to complete the dosage prescribed. In a few cases, patients discontinued antimicrobials midway through the course, either because they felt better or felt pain in the stomach when taking the drugs. One patient told us she was prescribed a 5-day antimicrobials course, but after 2 days did not feel better, and went instead to a private hospital for treatment. She attributed the problem to the doctor for not giving proper medicines. One patient, who had pus cells, but the AST showed a sterile sample, was still given antimicrobials as a precautionary measure. Another female patient who was pregnant was advised by her family members not to take excessive medicines since she was pregnant.

Theme 4: Doctors Justify Their Prescriptions on Medical Grounds

Doctors described the common ailments against which they prescribed antimicrobials to be Upper Respiratory Tract Infections, Pneumonia, Acute dysentery, Tonsillitis, UTIs, skin issues (such as Cellulitis, Abscess, Furuncle, and Carbuncle), and Dental cases (such as Cellulitis, Abscess and Caries). It was interesting to see that most doctors said that they always ordered an AST before initiating antimicrobials, while our analysis indicated that was not the case. One doctor told us that he would often start with a first-line drug while waiting for the AST report and would change the regimen if resistance was detected. This often did not happen as patients did not frequently return for consultation. Another doctor said, “We can’t make the patient wait, we must give them something, and if we see pus in some patient then I order for an AST but also start with the empirical therapy. Dental doctors did not order for an AST and initiated antimicrobials as a precautionary measure.

The drugs that the doctors felt were most effective were Amoxicillin, Doxycycline, and Azithromycin, which differed from our analysis which showed the most prescribed drugs were Amoxicillin + Clavulanic, Cefixime, Azithromycin, and Ciprofloxacin which belong to Amino penicillin + Beta-lactamase inhibitor, 3rd generation Cephalosporins, Macrolides and Fluoroquinolones respectively. Most doctors said that they prescribed drugs from the EDL, a point also confirmed by our analysis. While many physicians report that they follow guidelines for AST, in practice there is a deviation due to time constraints and perceived patient expectations (Knesebeck et al., 2019).

Doctors admitted that they had limited time to counsel patients and expected the pharmacists to do so. In saying that less than 20% of the patients who they advised to return for a follow-up visit, actually did, they implicitly suggested the futility of their counseling. Interestingly, we found differences in what was prescribed based on the prescriber, as shown in

Table 6.

Theme 5: Limited Compliance of Prescriptions to National Guidelines

We found limited compliance of prescriptions with the biomedical guidelines provided by apex national medical research institutions of the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) and the National Centre for Disease Control (NCDC). This discrepancy is summarized in

Table 7.

5.2. Phase 3 Analysis

Building the Biosocial Perspective

While the quantitative data analysis reflected the biomedical parameters of what drugs were prescribed, the qualitative analysis threw light on the perspectives of patients, clinicians, and pharmacists, the “why” underlying the prescriptions. In triangulating these two streams of analysis, we develop the “

biosocial” perspective, reflecting that bio and social are not separate but two sides of the same coin. Given the significant diversity in socio-cultural, economic, and health status across population groups, it is difficult to attribute any single reason for the diversity in prescriptions, but our approach helps to identify dominant tendencies on why certain antimicrobials were prescribed. Furthermore, information provided on prescription slips is often limited, such as missing information on confirmed diagnoses and prior history of prescriptions. However, looking at patterns over many slips and months provides an understanding of what antimicrobials are being prescribed and why (

Table 8).

5.3. Biosocial Themes

In public community health settings, prescription practices are severely influenced by biosocial components including both the social and biomedical dynamics. We discuss the different biosocial themes that emerged from our analysis.

Theme 1: Minimizing Biomedical Risks of Infections Through Broad-Spectrum Antimicrobials

Clinicians tend to mitigate risks in treating suspicious infections using broad-spectrum (>50%) antimicrobials such as Amoxiclav, Cefixime, and Azithromycin. This study supports the findings of Amritpal et al. (2018) who found that more than 65% of prescriptions were from broad-spectrum antimicrobials such as Amoxicillin- Clavulanic acid, Ceftriaxone, Ciprofloxacin, Clindamycin, and Piperacillin-tazobactam (Kaur et al., 2018). The biomedical justification is that these drugs provide medical cover against a variety of pathogens, which enables clinicians to respond quickly to ambiguity surrounding bacterial infections, particularly created by the limitations of diagnosis and incomplete information of a patient’s medical history. This minimizes the risk of treatment failure, particularly in critical circumstances where delays in effective antimicrobial therapy may lead to serious complications or even death for patients.

While this approach helps minimize immediate clinical challenges, it brings up significant concerns regarding antimicrobial stewardship. From the demand side, a key social condition that promotes the significant use of broad-spectrum antimicrobials is the limited knowledge most patients have about antimicrobials and the implications (Llor and Bjerrum, 2014). Over and inappropriate use of broad-spectrum antimicrobials is a serious concern where diagnostic facilities are limited, which could lead to continued use of broad-spectrum agents. This inference emphasizes the need to both enhance diagnostic capacity and simultaneously build awareness of patients.

Theme 2: Hospital Drugs Perceived to Be of Insufficient Quality for Treating Children

A critical issue concerns the perception of inadequate quality of antimicrobials available, particularly for pediatric patients in the hospital pharmacy. We found that 80 (11.8%) of the drugs prescribed from the pediatric OPD cases were branded medicines outside the EDL, such as Amoxicillin + clavulanic acid and Cefixime syrup. One child specialist told us that there were political pressures involved in the tendering of drugs, to go for the lowest-price generic drugs, which potentially compromised quality. A few parents told us that, they may buy drugs from the hospital pharmacy for themselves and adult family members, which may be of suspect quality, but will not risk their children even given the attraction of lower-priced generic drugs. For children, they preferred the branded more expensive drugs from private pharmacies, which were abundantly available. Contributing to this poor perception may be the simple packaging and labels of generic drugs.

Even though 98% of prescriptions in the hospital aligned with the EDL in the hospital, many clinicians expressed concerns about the inadequacy of available formulations for effectively treating children. The lack of age-appropriate dosing or paediatric formulations may contribute to the reluctance of clinicians to prescribe these drugs. The high percentage of prescriptions based on generic names (91%) also raised concerns regarding the regularity and dependability of these formulations, even though they are inexpensive. The overall effectiveness of paediatric care may be impaired in situations when the quality of drugs is unknown, leading doctors to look for other treatments and potentially expose children to undesirable treatment plans. There is an urgent need to promote better access to high-quality paediatric drugs and their availability in the pharmacy. Addressing this crucial gap in healthcare delivery requires both the promotion of reliable pharmaceutical sources and improved training in paediatric pharmacology.

A similar study (Norlin et al., 2021) found that nearly 25% of antimicrobials prescribed to children were inappropriate or unnecessary. This behaviour can be seen as also being encouraged by the pharmaceutical nexus (Smith et al., 2021), where the medical representatives, in collusion with the doctors and pharmacists, promote certain branded medicines. Commercial interests complemented by weak regulation, are often important drivers of the sale of sub-optimal quality branded drugs. Important research needs this raises is to study the quality of lower-priced branded drugs, to separate perception from reality.

Theme 4: Time Pressures of Doctors’ Limits Counseling of Patients

The high patient volumes experienced by clinicians create substantial time pressures that impede their ability to engage in meaningful patient counseling. This becomes a crucial handicap, given the poor knowledge and awareness of patients, of what are antimicrobials and how they should be consumed. Doctors have a serious lack of time for interactions with patients which leads to poor communication concerning treatment plans, potential negative outcomes, and the importance of following prescribed therapy. Despite their assertions that they offer counseling, many patients often leave appointments without an adequate understanding of their medications and why and how they should consume them. This information gap is often filled by pharmacists who provide advice to patients, particularly on administrative issues of how the drugs should be consumed but not on the biomedical characteristics of the drugs. This important piece of information thus does not come from either the doctor or the pharmacist, and patients are left largely on their own. This raises the importance of collaborative care approaches, involving doctors, pharmacists and patients, for more effective treatment compliances (Foo et al., 2020).

This dependence of patients on pharmacists emphasizes the necessity of collaborative care approaches, in which pharmacists can be extremely important in medication management and patient education, which necessarily needs to be complemented with the doctor’s biomedical advice. The low levels of literacy and the high percentage (80% and more) of rural residents, made the patients often under-equipped to ask doctors these questions. Further, patients themselves often demanded antimicrobials from the doctor (Sharma et al., 2021), raising the need for doctors to set aside adequate time to counsel patients. This is however, easier said than implemented in practice.

Theme 5: Follow-Up Visits by Patients Depend on Their State of Health and Social Advice, Often at the Cost of Defying Doctors’ Advice

We reported that only 30% of patients complete their antimicrobial course during follow-up visits, suggesting a worrying trend in which patient behavior is more affected by their own understanding of their health condition than by physician recommendations. Unless they have chronic problems or need continuous drugs, many patients stop taking drugs as soon as they start to feel better and frequently neglect returning for follow-up appointments. This reveals a serious absence of patient education leading to non-adherence of doctor’s advice.

Many patients told us that they were asked to do the AST before being prescribed antimicrobials. Often the treatment was started without the AST, but after the culture reports, prescriptions were modified. We found that in a few cases, the patients stopped the medicines when they felt better, which often led to the recurrence of infections. Encouraging follow-up visits is crucial for monitoring patient progress and ensuring adherence to prescribed therapies (Lee et al., 2023). In a few cases, on the phone call, the husband would reply on behalf of his wife, which could not let us ascertain first-hand the outcomes. This raises the possibility that patients fail to fully understand the justification for antimicrobial courses and the implications of ceasing medication abruptly. Better health outcomes and a reduction in the emergence of AMR could come from educational initiatives that emphasize the significance of follow-up visits, adherence to prescribed courses, and open communication from medical professionals.

Theme 6: Symptoms Guiding Prescription of Antimicrobials

The clinical symptoms that drive antimicrobial prescriptions predominantly included fever, abdominal pain, burning micturition, and symptoms related to upper respiratory tract infections (URTIs). Clinicians often respond to these symptoms by prescribing antimicrobials, reflecting a pattern that prioritizes immediate symptom relief over evidence-based treatment protocols. Patients with prior histories of antimicrobial use are particularly influential in this dynamic, as they often demand antimicrobials based on their past experiences which enhances prescriptions (Avent et al., 2020), often inappropriate (Sulis et al., 2020). Our study raises similar concerns about the overuse of antimicrobials in certain OPD settings, especially dental, paediatrics, and skin. In many cases, such as dental, the antimicrobials are prescribed as a precautionary measure, or due to the issue of people not being able to afford definitive dental treatment, therefore getting recurrent infections.

We found next to no cases in which antimicrobial therapy was initiated after an AST. This reliance on symptomatic presentation exacerbates over-prescriptions and is even seen in better-resourced settings such as Australia ( (Yau et al., 2021). We also found that in many cases of viral infections, antimicrobials were prescribed, as also noted in other studies for the treatment of URTIs (Machado-Duque et al., 2021). During COVID-19, India saw large spike in the use of antimicrobials. To combat these trends, it is essential to foster a culture of diagnostic rigor that encourages healthcare providers to utilize appropriate testing and guidelines in making prescribing decisions. While this represents more of an idealized practice, it is hard to implement given the resource and capacity constraints that exist. However, we believe our research can help flag these needs more strongly.

6. Conclusions

Our study is among the first of its kind in India which presents a biosocial perspective on prescription patterns in a community health context and offers important insights into the link between integrated biological data and the social determinants influencing antimicrobials prescriptions. While quantitative analysis uncovers trends and frequently prescribes antimicrobials, qualitative data describes the social dynamics that impact prescription decisions by elucidating the attitudes and reasons of patients, physicians, and pharmacists. The results highlight how the perceptions of patients and clinicians about infections and treatment, their time constraints, and the use of broad-spectrum antimicrobials impact prescribing practices that might not be in accordance with optimum policies for antimicrobial stewardship. The necessity for comprehensive efforts that address both clinical and social dimensions is highlighted, such as perceptions about the quality of hospital drugs and patient adherence patterns. By incorporating the biosocial elements that influence antimicrobial prescribing, this approach suggests pathways to improve healthcare outcomes and reduce AMR involving enhanced diagnostic capacities, patient education, and support for evidence-based prescribing practices.

Author Contributions

conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, investigation, visualization, and writing—original draft, SS: investigation, visualization, and writing— review and editing, visualization, resources, supervision, VM: conceptualization, formal analysis, investigation, visualization, and writing—original draft, AM: investigation, supervision, resources, RKB: visualization, investigation.

Funding

The project is supported through funding received from the Research Council of Norway towards the Equity AMR research project.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the HISP India team members for their collaborative efforts and support, as well as the state government and hospital authorities for their invaluable contributions to this research project.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there was no conflict of interest.

References

- Alqarni, M.A.; Alshammari, N.A.; Aljohani, A.A.; Alenezi, B.H.; Alsubhi, I.M.; Al-Harbi, H.R.; Alamri, K.A.; Algthami, N.D.; Alhosayni, S.A.; Alsukhayri, O.M.; et al. The Role Of Community Pharmacists In Educating Patients About Drug Interactions And Medication Safety. 2023, 10, 276–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avent, M.L.; Cosgrove, S.E.; Price-Haywood, E.G.; van Driel, M.L. Antimicrobial stewardship in the primary care setting: from dream to reality? BMC Fam. Pr. 2020, 21, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beyene, K.A.; Sheridan, J.; Aspden, T. Prescription Medication Sharing: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Am. J. Public Heal. 2014, 104, e15–e26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hindi, A.M.K.; Schafheutle, E.I.; Jacobs, S. Patient and public perspectives of community pharmacies in the United Kingdom: A systematic review. Heal. Expect. 2017, 21, 409–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cars, O.; Mölstad, S.; Melander, A. Variation in antibiotic use in the European Union. Lancet 2001, 357, 1851–1853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charani, E. BSAC Vanguard Series: Why culture matters to tackle antibiotic resistance. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2022, 77, 1506–1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mesafint, E.; Wondwosen, Y.; Dagnaw, G.G.; Gessese, A.T.; Molla, A.B.; Dessalegn, B.; Dejene, H. Study on knowledge, attitudes and behavioral practices of antimicrobial usage and resistance in animals and humans in Bahir Dar City, Northwest Ethiopia. BMC Public Heal. 2024, 24, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deschepper, R.; Grigoryan, L.; Lundborg, C.S.; Hofstede, G.; Cohen, J.; Van Der Kelen, G.; Deliens, L.; Haaijer-Ruskamp, F.M. Are cultural dimensions relevant for explaining cross-national differences in antibiotic use in Europe? BMC Heal. Serv. Res. 2008, 8, 123–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foo, K.M.; Sundram, M.; Legido-Quigley, H. Facilitators and barriers of managing patients with multiple chronic conditions in the community: a qualitative study. BMC Public Heal. 2020, 20, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, S.G.; Adithan, C.; Harish, B.; Roy, G.; Malini, A.; Sujatha, S. Antimicrobial resistance in India: A review. J. Nat. Sci. Biol. Med. 2013, 4, 286–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, Y.H.T.; van Doorn, R.; Van Nuil, J.I.; Lewycka, S. Dilemmas of care: Healthcare seeking behaviours and antibiotic use among women in rural communities in Nam Dinh Province, Vietnam. Soc. Sci. Med. 2024, 363, 117483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaam, M.; Naseralallah, L.M.; Hussain, T.A.; Pawluk, S.A. Pharmacist-led educational interventions provided to healthcare providers to reduce medication errors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLOS ONE 2021, 16, e0253588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdu-Aguye, S.N.; Labaran, K.S.; Danjuma, N.M.; Mohammed, S. An exploratory study of outpatient medication knowledge and satisfaction with medication counselling at selected hospital pharmacies in Northwestern Nigeria. PLOS ONE 2022, 17, e0266723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonas, O.B. , Irwin, A., Berthe, F.C.J., Le Gall, F.G., Marquez, P. V., 2017. Drug-Resistant Infections: A Threat to Our Economic Future. World Bank Rep.

- Kaur, A.; Bhagat, R.; Kaur, N.; Shafiq, N.; Gautam, V.; Malhotra, S.; Suri, V.; Bhalla, A. A study of antibiotic prescription pattern in patients referred to tertiary care center in Northern India. Ther. Adv. Infect. Dis. 2018, 5, 63–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knesebeck, O.v.D.; Koens, S.; Marx, G.; Scherer, M. Perceptions of time constraints among primary care physicians in Germany. BMC Fam. Pr. 2019, 20, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotwani, A.; Joshi, J.; Lamkang, A.S. Over-the-Counter Sale of Antibiotics in India: A Qualitative Study of Providers’ Perspectives across Two States. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koya, S.F.; Ganesh, S.; Selvaraj, S.; Wirtz, V.J.; Galea, S.; Rockers, P.C. Consumption of systemic antibiotics in India in 2019. Lancet Reg. Heal. - Southeast Asia 2022, 4, 100025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.Y.; Shanshan, Y.; Lwin, M.O. Are threat perceptions associated with patient adherence to antibiotics? Insights from a survey regarding antibiotics and antimicrobial resistance among the Singapore public. BMC Public Heal. 2023, 23, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, J.M.; Singh, S.R.; Duong, M.C.; Legido-Quigley, H.; Hsu, L.Y.; Tam, C.C. Impact of national interventions to promote responsible antibiotic use: a systematic review. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2019, 75, 14–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Liu, C.; Wang, D.; Deng, Z.; Tang, Y.; Zhang, X. Determinants of antibiotic prescribing behaviors of primary care physicians in Hubei of China: a structural equation model based on the theory of planned behavior. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control. 2019, 8, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llor, C.; Bjerrum, L. Antimicrobial resistance: risk associated with antibiotic overuse and initiatives to reduce the problem. Ther. Adv. Drug Saf. 2014, 5, 229–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Machado-Duque, M.E.; García, D.A.; Emura-Velez, M.H.; Gaviria-Mendoza, A.; Giraldo-Giraldo, C.; Machado-Alba, J.E. Antibiotic Prescriptions for Respiratory Tract Viral Infections in the Colombian Population. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marlière, G.L.L.; Ferraz, M.B.; dos Santos, J.Q. Antibiotic consumption patterns and drug leftovers in 6000 Brazilian households. Adv. Ther. 2000, 17, 32–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minssen, T.; Outterson, K.; Van Katwyk, S.R.; Batista, P.H.D.; Chandler, C.I.R.; Ciabuschi, F.; Harbarth, S.; Kesselheim, A.S.; Laxminarayan, R.; Liddell, K.; et al. Social, cultural and economic aspects of antimicrobial resistance. Bull. World Heal. Organ. 2020, 98, 823–823A. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, A.; Surial, R.; Sahay, S.; Thakral, Y.; Gondara, A. Social and cultural determinants of antibiotics prescriptions: analysis from a public community health centre in North India. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1277628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muteeb, G. , Rehman, T., Shahwan, M., Aatif, M., 2023. Origin of Antibiotics and Antibiotic Resistance, and Their Impacts on Drug Development : A Narrative Review 1–54.

- Norlin, C.; Fleming-Dutra, K.; Mapp, J.; Monti, J.; Shaw, A.; Bartoces, M.; Barger, K.; Emmer, S.; Dolins, J.C. A Learning Collaborative to Improve Antibiotic Prescribing in Primary Care Pediatric Practices. Clin. Pediatr. 2021, 60, 230–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Otaigbe, I.I.; Elikwu, C.J. Drivers of inappropriate antibiotic use in low- and middle-income countries. JAC-Antimicrobial Resist. 2023, 5, dlad062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- E Ryan, R.; Santesso, N.; Lowe, D.; Hill, S.; Grimshaw, J.M.; Prictor, M.; Kaufman, C.; Cowie, G.; Taylor, M. Interventions to improve safe and effective medicines use by consumers: an overview of systematic reviews. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2014, 2022, CD007768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salam, A.; Al-Amin, Y.; Salam, M.T.; Pawar, J.S.; Akhter, N.; Rabaan, A.A.; Alqumber, M.A.A. Antimicrobial Resistance: A Growing Serious Threat for Global Public Health. Healthcare 2023, 11, 1946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleh, N.; Awada, S.; Awwad, R.; Jibai, S.; Arfoul, C.; Zaiter, L.; Dib, W.; Salameh, P. Evaluation of antibiotic prescription in the Lebanese community: a pilot study. Infect. Ecol. Epidemiology 2015, 5, 27094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seeberg, J. An Epidemic of Drug Resistance: Tuberculosis in the Twenty-First Century. Pathogens 2023, 12, 652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, M.; Payal, N.; Devi, L.S.; Gautam, D.; Khandait, M.; Hazarika, K.; Sardar, M. Study on Prescription Audit from a Rural Tertiary Care Hospital in North India. J. Pure Appl. Microbiol. 2021, 15, 1931–1939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shetty, Y.; Kamat, S.; Tripathi, R.; Parmar, U.; Jhaj, R.; Banerjee, A.; Balakrishnan, S.; Trivedi, N.; Chauhan, J.; Chugh, P.K.; et al. Evaluation of prescriptions from tertiary care hospitals across India for deviations from treatment guidelines & their potential consequences. Indian J. Med Res. 2024, 159, 130–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, R.; Loh, M.; Mills, D. Prescription audit. Br. Dent. J. 2021, 230, 189–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sulis, G.; Adam, P.; Nafade, V.; Gore, G.; Daniels, B.; Daftary, A.; Das, J.; Gandra, S.; Pai, M. Antibiotic prescription practices in primary care in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLOS Med. 2020, 17, e1003139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodrigues, A.T.; Ferreira, M.; Roque, F.; Falcão, A.; Ramalheira, E.; Figueiras, A.; Herdeiro, M.T. Physicians’ attitudes and knowledge concerning antibiotic prescription and resistance: questionnaire development and reliability. BMC Infect. Dis. 2015, 16, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velazquez-Meza, M.E.; Galarde-López, M.; Carrillo-Quiróz, B.; Alpuche-Aranda, C.M. Antimicrobial resistance: One Health approach. Veter- World 2022, 15, 743–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worlds, B. n.d. No Title.

- Wozniak, T.M.; Cuningham, W.; Ledingham, K.; McCulloch, K. Contribution of socio-economic factors in the spread of antimicrobial resistant infections in Australian primary healthcare clinics. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 2022, 30, 294–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yau, J.W.; Thor, S.M.; Tsai, D.; Speare, T.; Rissel, C. Antimicrobial stewardship in rural and remote primary health care: a narrative review. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control. 2021, 10, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).