1. Introduction

The number of heavy metals in terrestrial and aquatic habitats has increased in tandem with rising levels of urbanization and industrialization [

1]. Heavy metals from improperly managed industrial waste are released into the environment, eventually making their way to humans through the food chain [

2].

Numerous industrial processes, including electroplating, the manufacture and disposal of nickel-cadmium batteries, fuels, and pigments, allow toxic metal ions to infiltrate the biosphere. Furthermore, several of them such as cadmium (II), mercury (II), chromium (vi) and lead (II) are known to be extremely poisonous at low concentrations, not biodegradable, and to tend to accumulate in living beings, producing major sickness and disorders. As a result, chromium and cadmium are harmful substances for the environment [

3].

Silica gel immobilized with diverse organic compounds that can chelate metals, has drawn a lot of attention among the many adsorbents [

4]. This is because compared to other organic and inorganic supports, this silica support has clear advantages.

Two techniques, Cerevisiae and Leuconostoc mesenteroides immobilised in silica materials, were developed by Siobodanka

et al. [

5] to remove cadmium ions from aqueous solutions. The cerevisiae composite and L. mesenteroides had maximum theoretical binding capacities of 54 mg/g and 90 mg/g, respectively. According to Nnaji

et al. [

6], heavy metal removal from contaminated sites can be accomplished economically and sustainably by employing strategies like phytoaccumulation and phytostabilization. Nazaripour

et al. [

7] examined several approaches for removing heavy metal ions from wastewater, including membrane and adsorption techniques. With an emphasis on adsorption techniques, Rao and Peddy [

8] examined a variety of approaches for treating mining effluents. Using treated date pits, Al-Sharani and AlSharani [

9] evaluated the removal of Cr (II) and Co (II) ions from aqueous solutions, demonstrating their efficacy and environmental friendliness. The various adsorption techniques for the real-time removal of heavy metals from wastewater were examined by Gupta and Ali [

10]. The efficiency of using agricultural waste materials to remove heavy metals from wastewater was examined by Mohan and Singh [

11]. The kinetics involved in the adsorption of chromium and cadmium ions were examined by Ho and McKay [

12]. To eliminate inorganic contaminants from environmental water, Natalia

et al. [

13] evaluated the adsorption affinities for EDTA-functionalized samples. The results indicated that Pb (II) had the highest adsorption value (195.6 mg/g) and Mn (II) had the lowest value (49.4 mg/g). The adsorption capacity of silica beads functionalised with aminosilane coupling agents, 3-glycidyloxypropyl triethoxysilane, [3-(2-aminoethylamino) propyl] triethoxysilane (AEAPTES), and polyethylenimines (PEIs), for the chromium (VI) ion was examined by Nishino

et al. [

14]. They found that AEAPTES had the maximum adsorption at the initial pH of 3.0. To remove chromium oxyanions from aqueous solutions, Surucic

et al. [

15] used sorbent surfaces with diethylene and amino propyl silane groups, respectively. They discovered that diethylyne triamine produced better results. Using horsetail to create an amorphous powder, Guevara-Lora and Wronski [

16] created an adsorption material for Cr (VI) ions that demonstrated adsorption capacity for the ion following treatment with dodecylamine surfactants.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals and Solutions

Pure chromatographic grade silica (mesh size 60-200 um), cadmium (II) sulphate, ethanol, methanol, 3-aminopropyl trimethoxy silane, Salicylaldehyde, Dichloroethane, glacial acetic acid and distilled deionized water were used. The chemicals are of analytical grade.

Standard solutions of 1000 mg/L of cadmium and chromium were prepared as stock solutions from their salts, Cadmium (II) Sulphate, Cd (II)SO4.8H2O and Chromium (III) Nitrate. This was done by dissolving 3.14 g of cadmium and 6.78 g of chromium in 1000 cm3 of distilled deionized water. From the stock solution, working solutions of varying initial concentrations of metal ions were prepared by serial dilution using distilled deionized water.

2.2. Instrumentation

The concentrations of the metal ions were analysed with a Buck Scientific Atomic Absorption spectrophotometer model 210/211 VGP Buck Scientific, USA). The wavelengths used for the cadmium ions was 228.9 nm and while that of chromium was 357.9 nm. Fourier Transform Infra-Red (FT-IR) spectra were recorded on Shimadzu FTIR-84005 machine (Norwalk, CT, USA) using KBr pellets. The pH measurements were made using Corning Scholar 425 digital pH meter (NY USA). Batch adsorption processes were conducted using thermostatic water bath shaker, SHZ-82 (China) at 150 rpm.

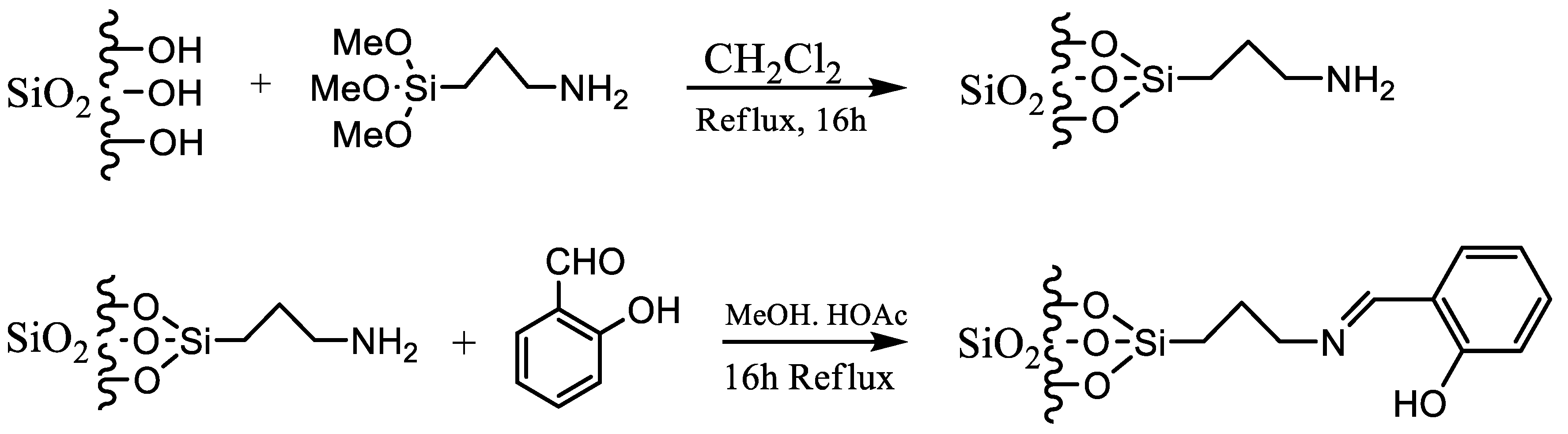

2.3. Synthesis of Schiff Base and Schiff Base Immobilized Silica

The Schiff base used in this work was prepared by mixing 5 ml of 10 % salicylaldehyde solution with 5.0 ml of 3-aminopropyl trimethoxy silane, and the mixture stirred. This was followed with a gradual addition of 0.1 mol/dm

3 NaOH to the mixture for about 30 minutes. The final mixture was left for about 15 minutes, filtered, washed with cold ethanol and dried. The modification process was carried out according to a method described by Mortazavi

et al.,[

17] with slight modifications. The initial step involved the production of SiO

2-supported aminopropyl trimethoxy silane (APTS), by refluxing 5.0 g of pure silica powder with 5.0 ml of 3-aminopropyl trimethoxy silane in 50 ml dichloromethane for 16 hours. The solid precipitate was filtered and washed off with distilled water and dried at room temperature. The second step involved the addition of 5 ml of 10 % salicylaldehyde and 10 ml of acetic acid to the suspension of the silica-supported aminopropyl trimethoxy silane in 60 ml methanol and the reaction mixture refluxed for another 16 hours to produce a salicylaldehyde-modified 3-aminopropyl trimethoxy silane (APTS). Both the pure silica and the salicylaldehyde modified APTS were tightly covered and carefully labelled for the adsorption studies.

The two steps involved in the modification process are shown in

Picture 1.

2.4. Removal Studies With Batch Methods

Adsorption studies were conducted in labelled 100 cm

3 beakers having 0.2 g of each of the adsorbents (silica and functionalized silica) with 25 cm

3 of the adsorbates (solutions of metal ions). The flasks were agitated on a stirrer at a constant speed of 150 rpm. At the end of the experiments, residual cadmium and chromium ions concentrations were analysed using Atomic Adsorption Spectrophotometer (AAS). The amount of metal ions adsorbed by the adsorbents (mg/g) was calculated according to equation 1.

where q

e (mg/g) is the amount adsorbed, C

o (mg/L) is the first metal ion concentration in solution, C

e (mg/L) is the residual/equilibrium concentration of metal ions, v = volume of adsorbate solution in litre, while m = mass of the adsorbent used.

The best contact time was determined to be 40 minutes and used in all the adsorption experiments. Uptake experiments of metal ions at different pHs (i.e. 2, 4, 6, 8 and 10) were conducted by placing 0.2 g of each of each of the adsorbents having 25 ml solution of cadmium with an initial concentration of 50 mg/L. The pH was adjusted using 0.1 M HCl and 0.1 M NaOH. The residual concentration of cadmium and chromium ions were found using AAS. The amount of metal ions adsorbed by the adsorbents was calculated using equation 1. The results showed that qe maximum observed was at pH 7.0 (silica) and 6.0 (Salicylaldehyde APTS).

2.5. Adsorption Isotherms

Cadmium and chromium ions concentrations of 10, 20, 30, 40, 50 and 60 mg/L were prepared and used to obtain the adsorption isotherm data on the adsorption process. After equilibration, 5 ml of the filtrate was used for the determination of residual metal ion concentration by AAS. The amount of metal ions adsorbed by the adsorbents were calculated according to equation 1.

2.6. Kinetic Adsorption Experiments

The kinetic study used 0.2 g of the adsorbents at their respective optimum pHs. Data were obtained after treatment of a series of 25 ml of the adsorbents with 50 mg/L of metal ions solutions. These series of samples were quenched at time intervals of 20, 30, 40, 50 and 60 minutes by filtration. The concentration of the filtrate was analysed by AAS. These results were used to obtain the adsorption kinetics.

3. Results And Discussion

3.1. Characterization of Materials

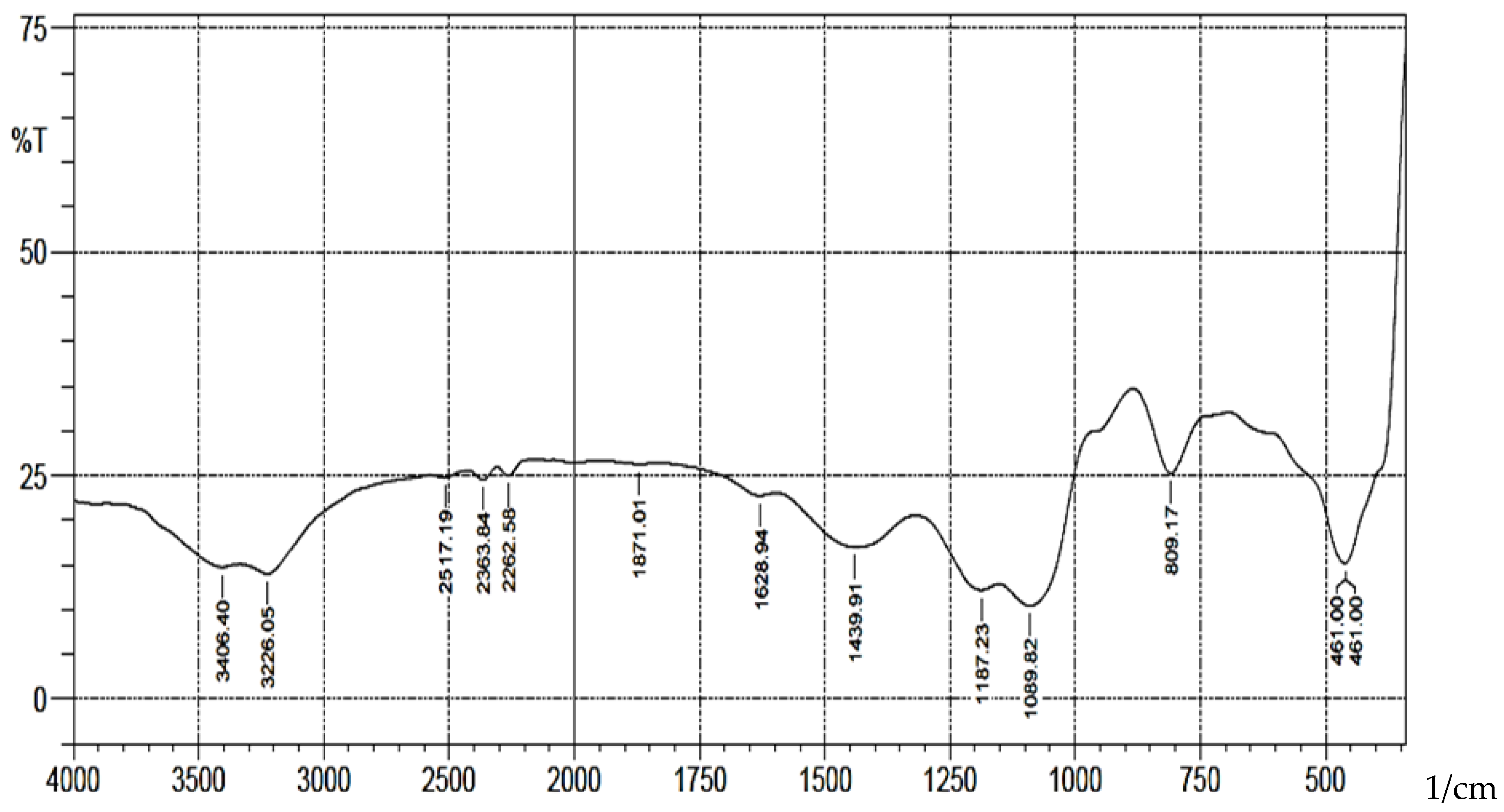

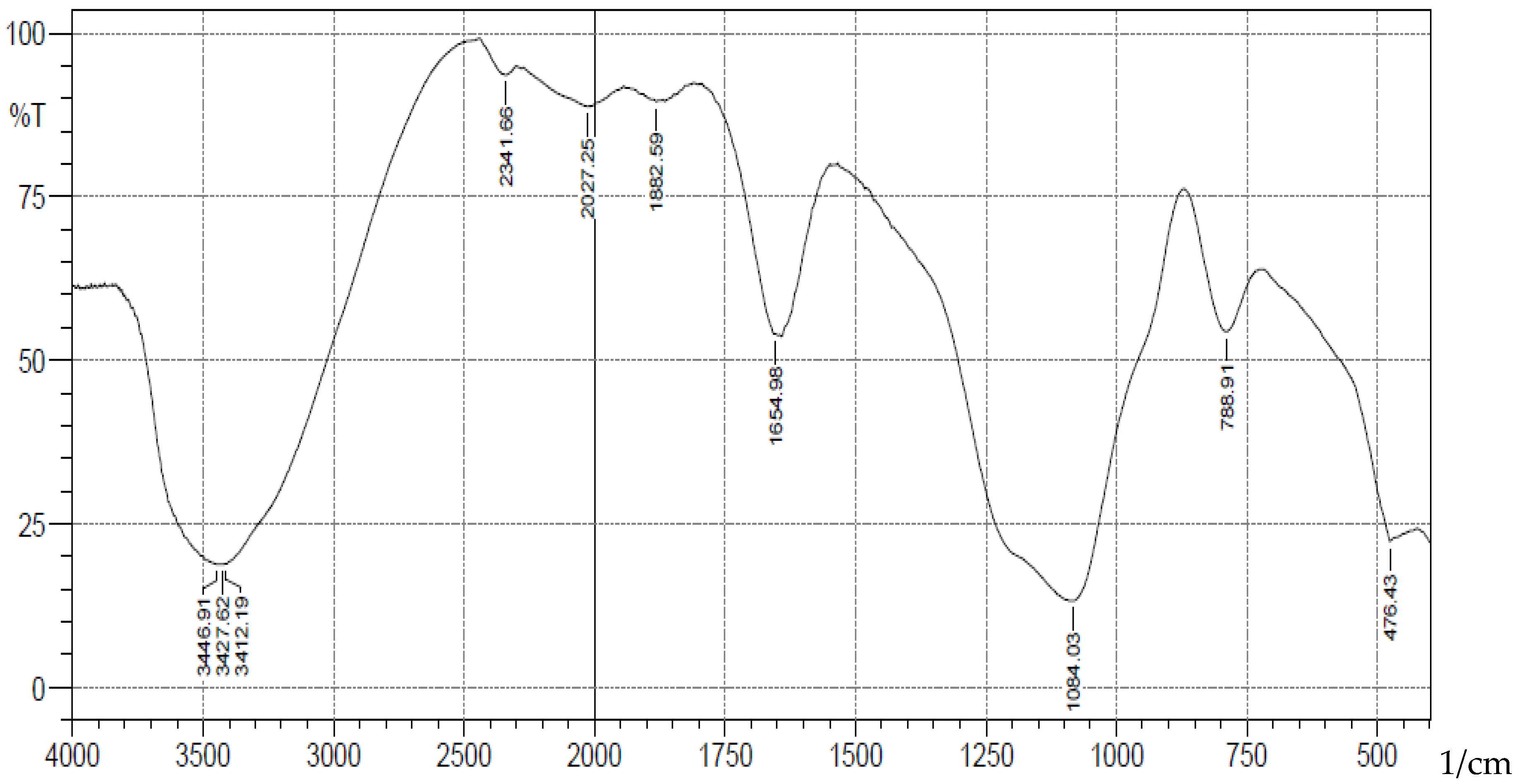

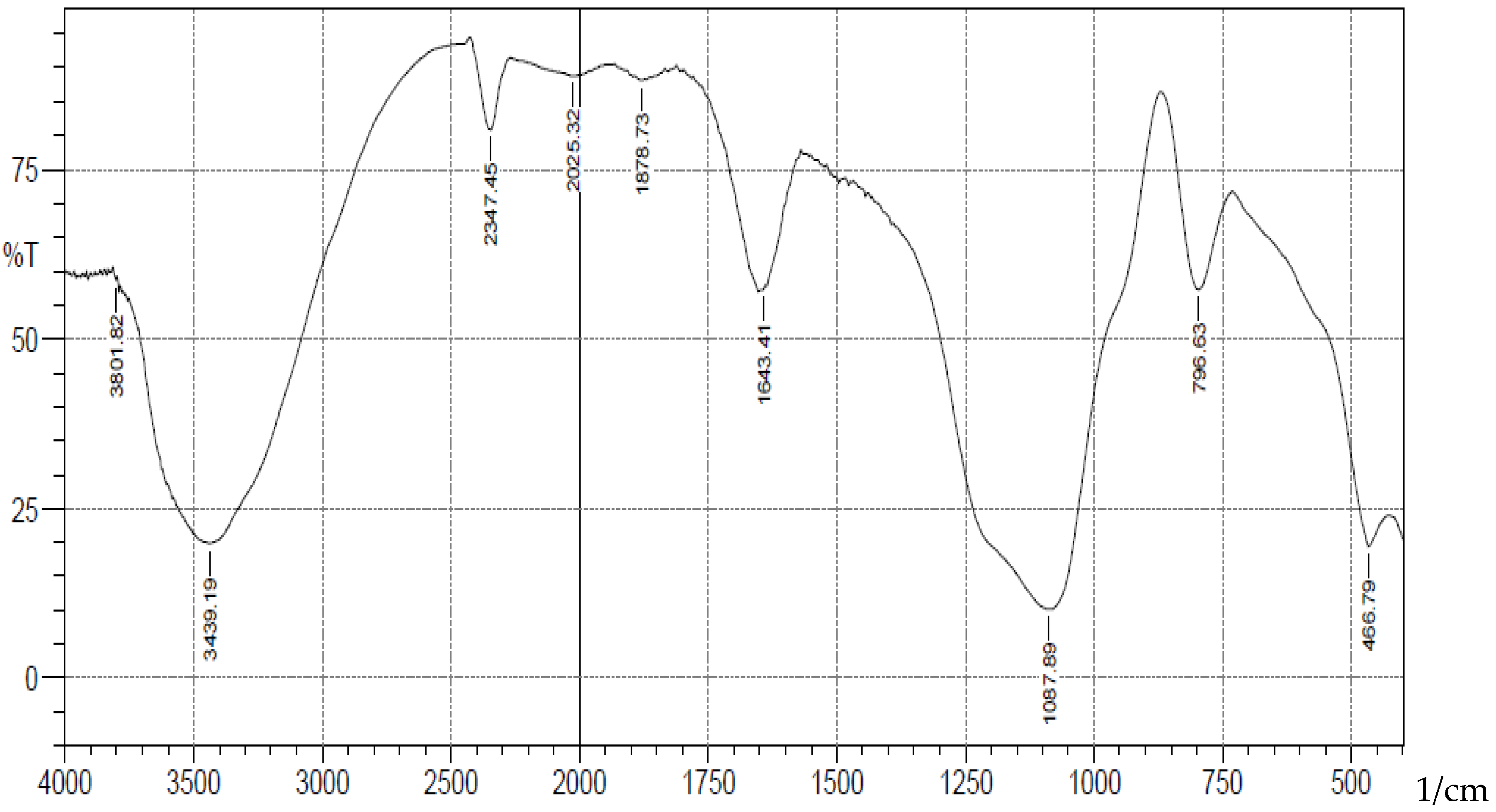

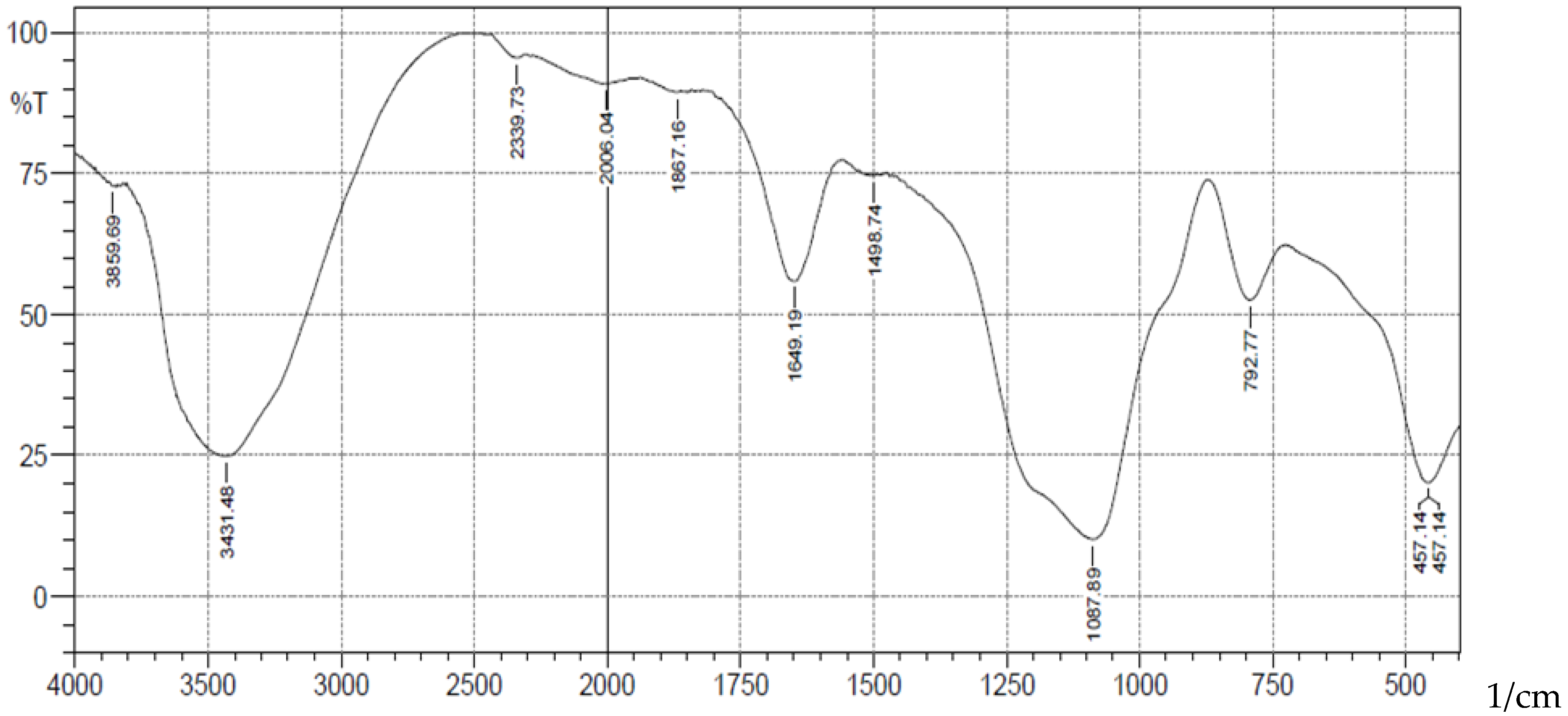

A schematic representation of synthesis of the Schiff base is shown in scheme 1. The FT-IR spectra (

Figure 1) showed absorption bands at 3406-3226(b), 1089(vsp), 809(m) and 461(s) cm

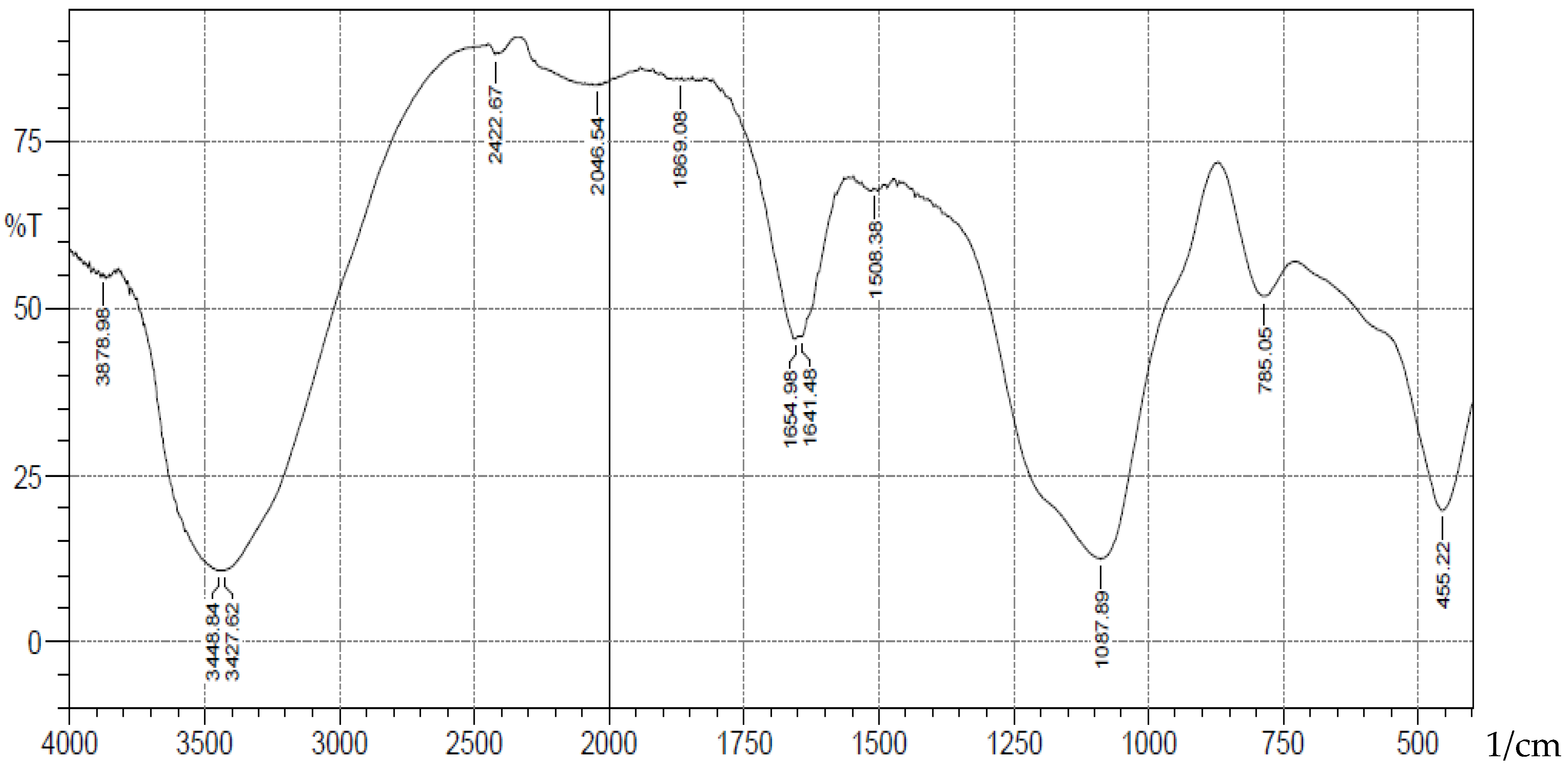

-1 corresponding to stretching vibrations of silanol -OH, asymmetric stretching vibration of Si-O, symmetric stretching vibration of Si-O-Si, and asymmetric Si-O-Si bonding respectively. After immobilization with 3-aminopropyl trimethoxy silane (APTS) and salicylaldehyde, other characteristic vibrational frequencies corresponding to more functional groups are visible. The bonding of Cd (II) and Cr (II) ions unto silica and functionalized silica are in

Figure 2,

Figure 3,

Figure 4 and

Figure 5 respectively.

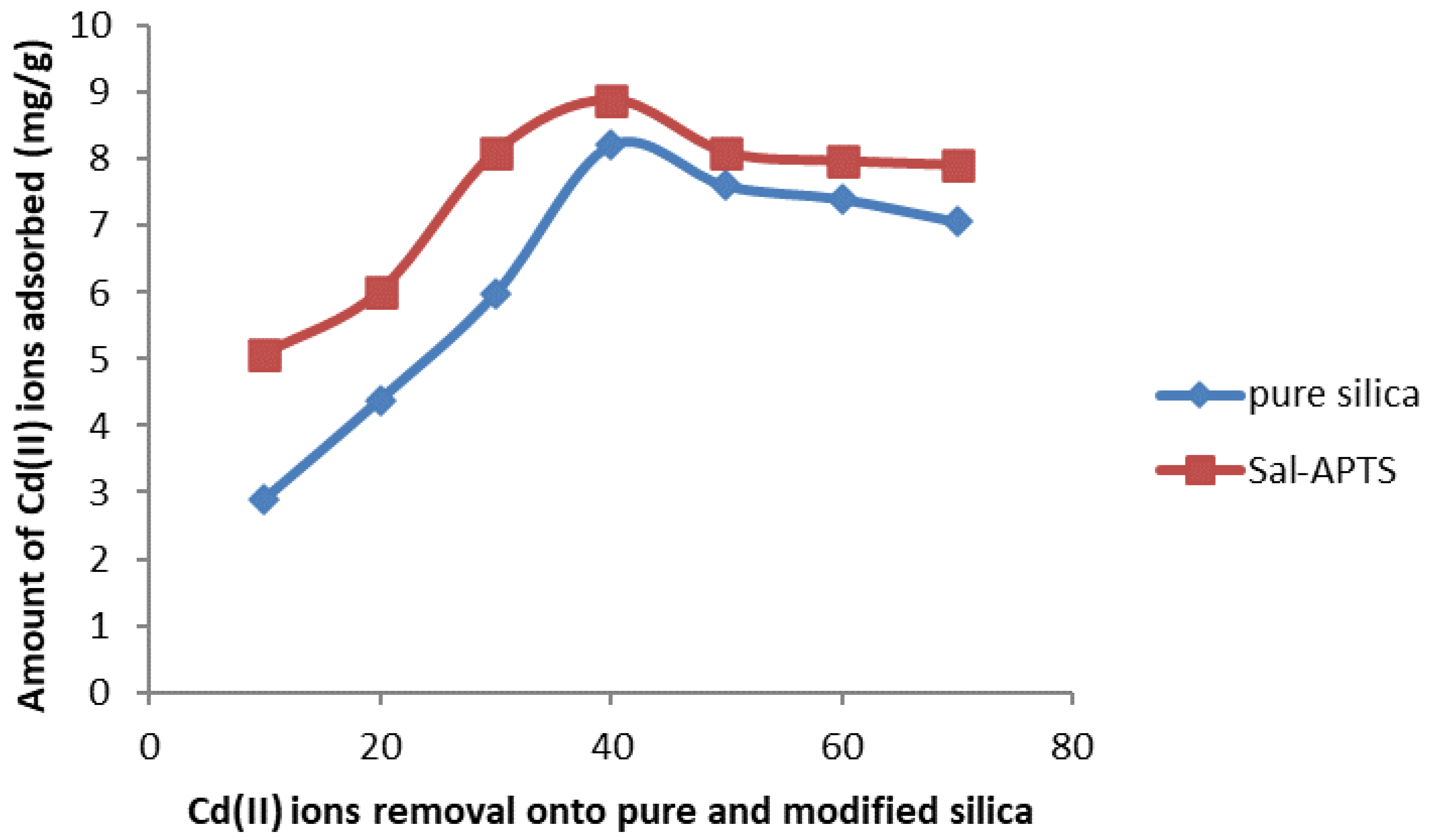

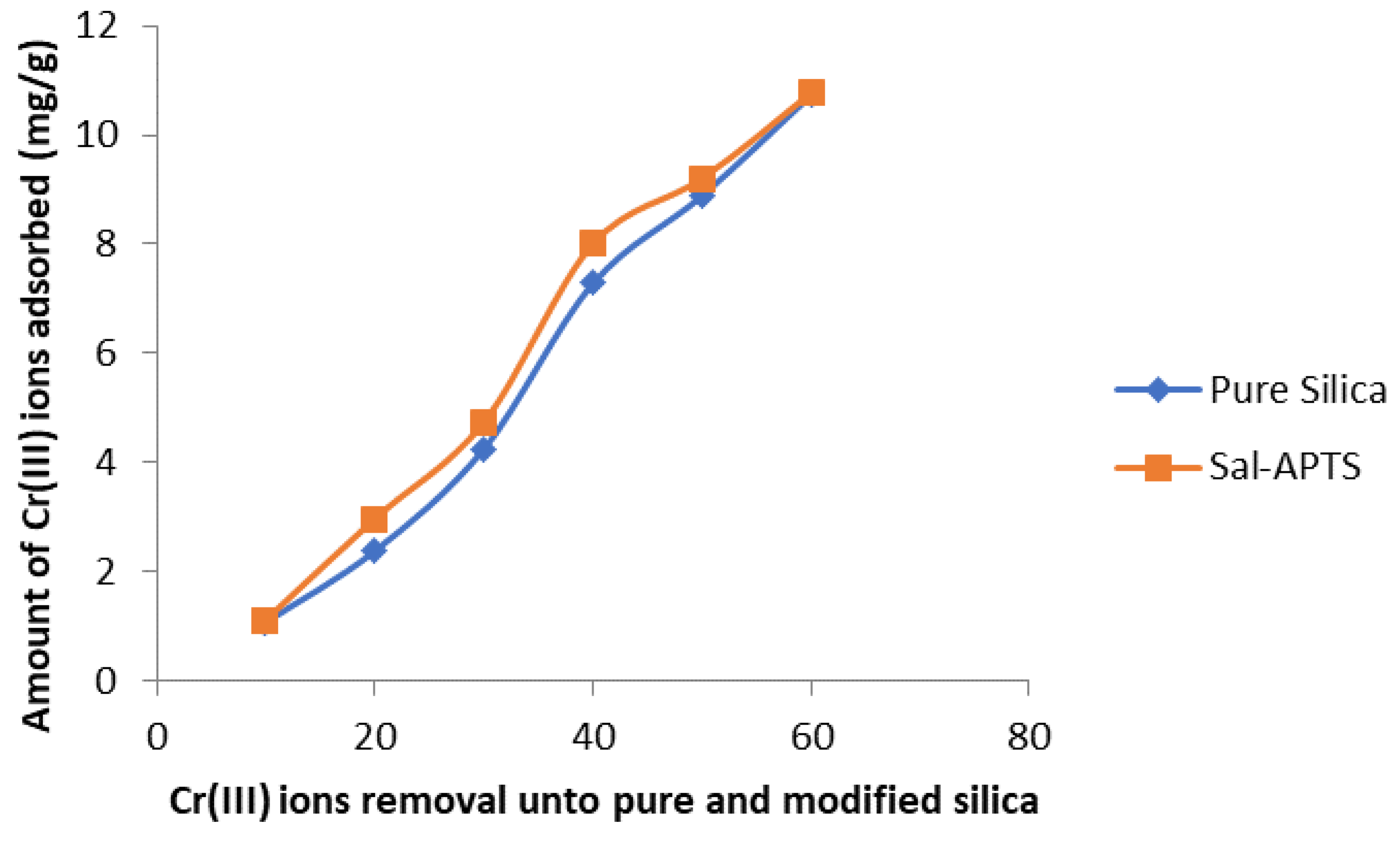

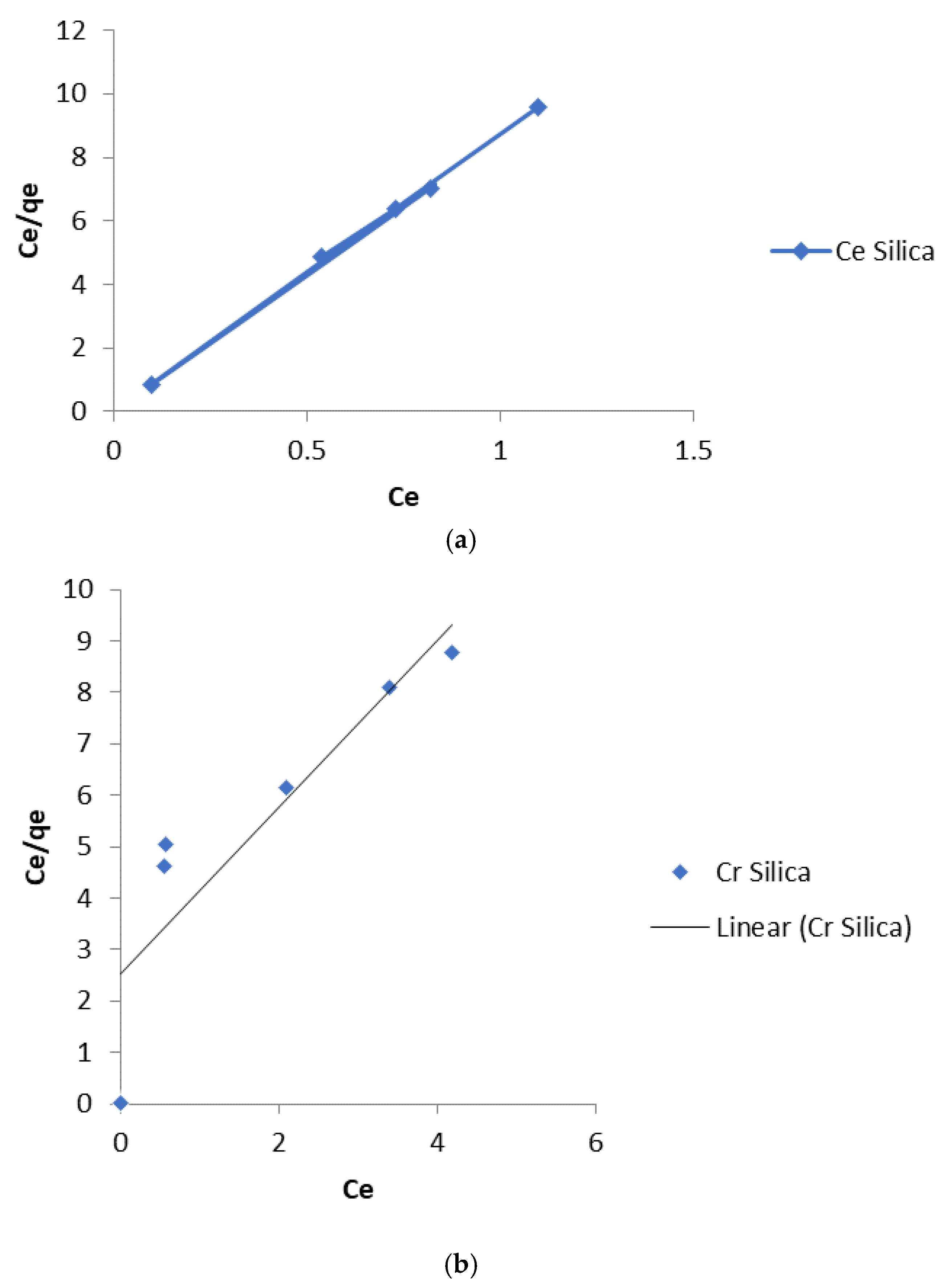

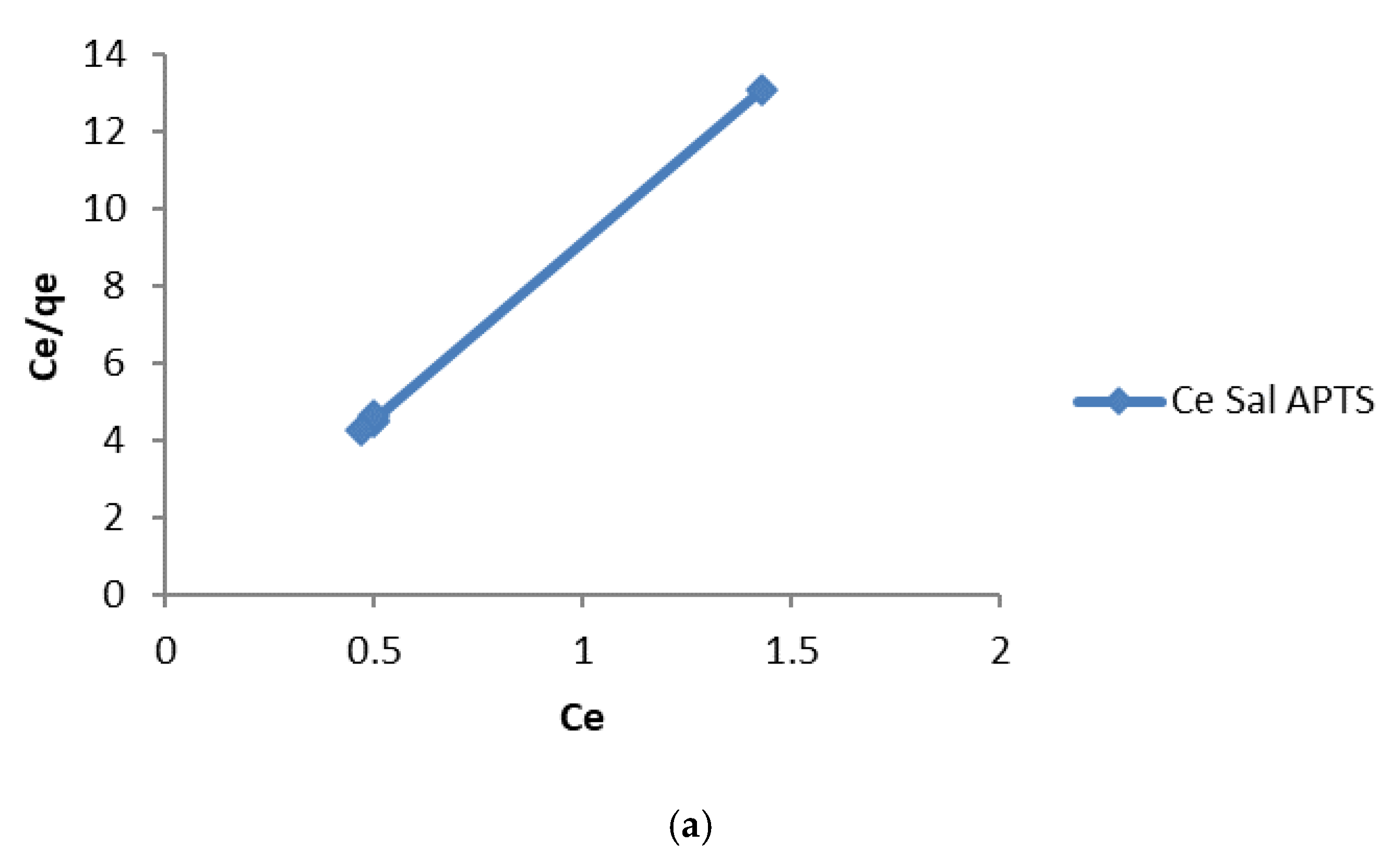

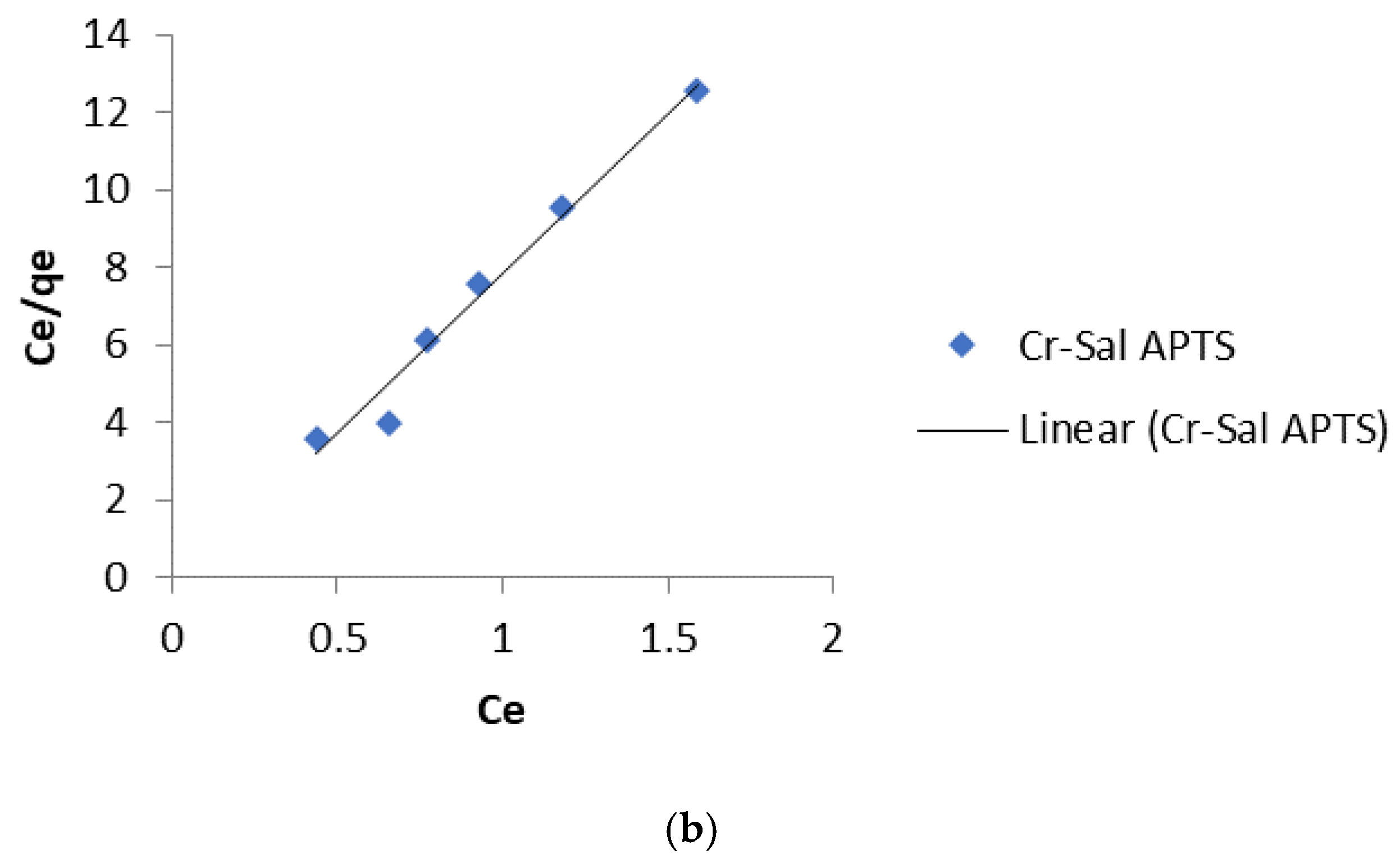

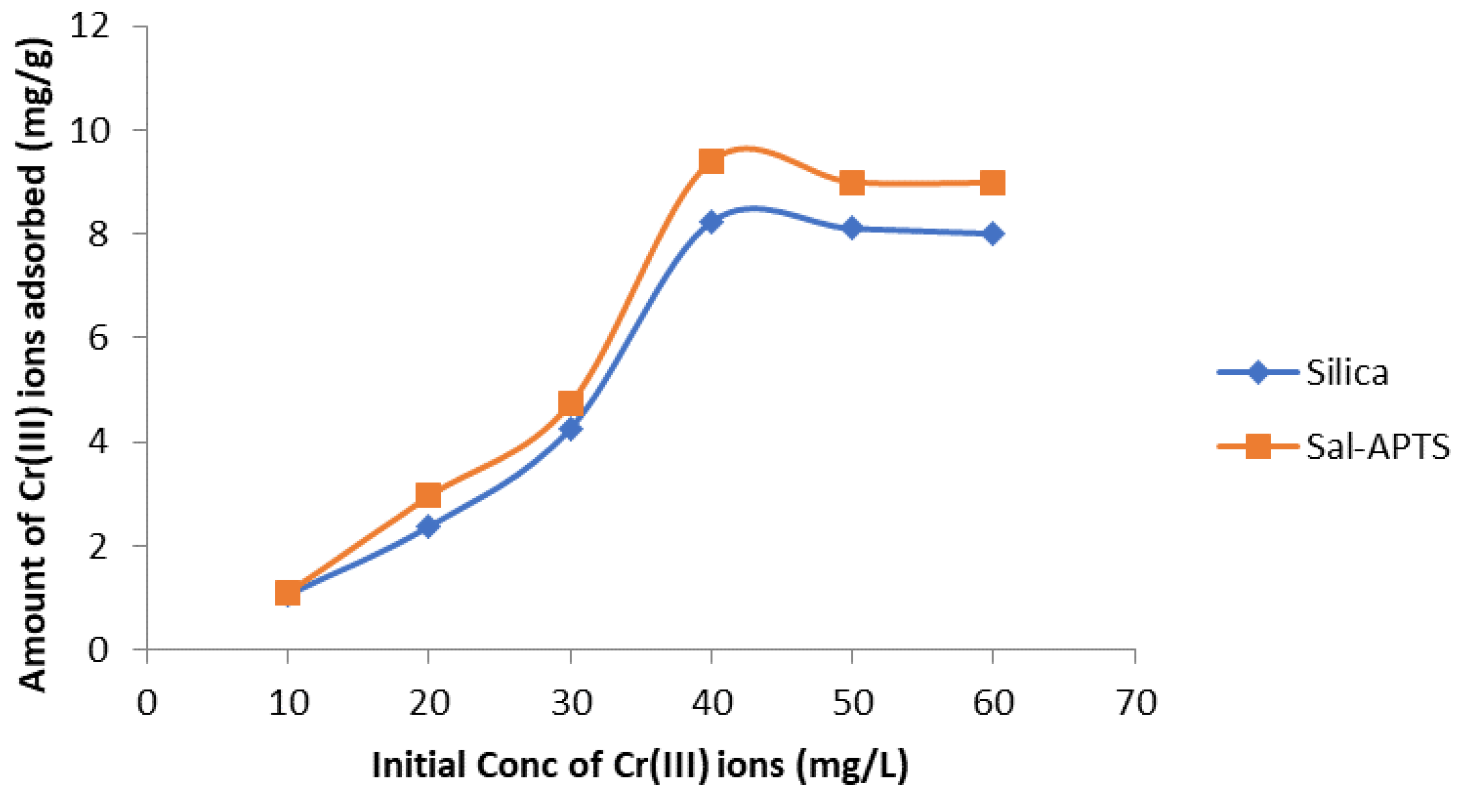

3.2. Adsorption Isotherms

The initial cadmium (II) and chromium (III) ion concentrations (10-60 mg/L) were used for the investigation of the adsorption isotherm. The equilibrium concentrations were obtained after 40 minutes of contact time. The amount of Cd (II) ions adsorbed on pure and functionalized silica were found to increase as the initial metal ions concentration increased and continued up to 40 mg/L and level off or decreased thereafter (

Figure 6 and

Figure 7) but Cr III) ions adsorption continued up to 60 mg/L.

Three models Dubinin-Radushkevich (D-R), Freundlich and Langmuir were applied to analyse the data. Both D-R and Freundlich gave extremely low correlation coefficient values, so these models were not reported for adsorption isotherm studies. The Langmuir isotherm and model is based on the equation:

Where Ce (mg/L) is the equilibrium concentration, qe (mg/g) is the amount of metal ions adsorbed at equilibrium, qmax (mg/g) is the maximum adsorption capacity and KL (dm3g-1) is a constant related to adsorption/desorption energy.

The linear plot of Ce/q

e vs Ce should yield a straight line if the Langmuir equation is obeyed by the adsorption equilibrium. The constants K

L and q

max are obtained from the intercept and slope of the linear plots (

Figure 8 and

Figure 9).

3.3. The Langmuir Isotherm Parameters

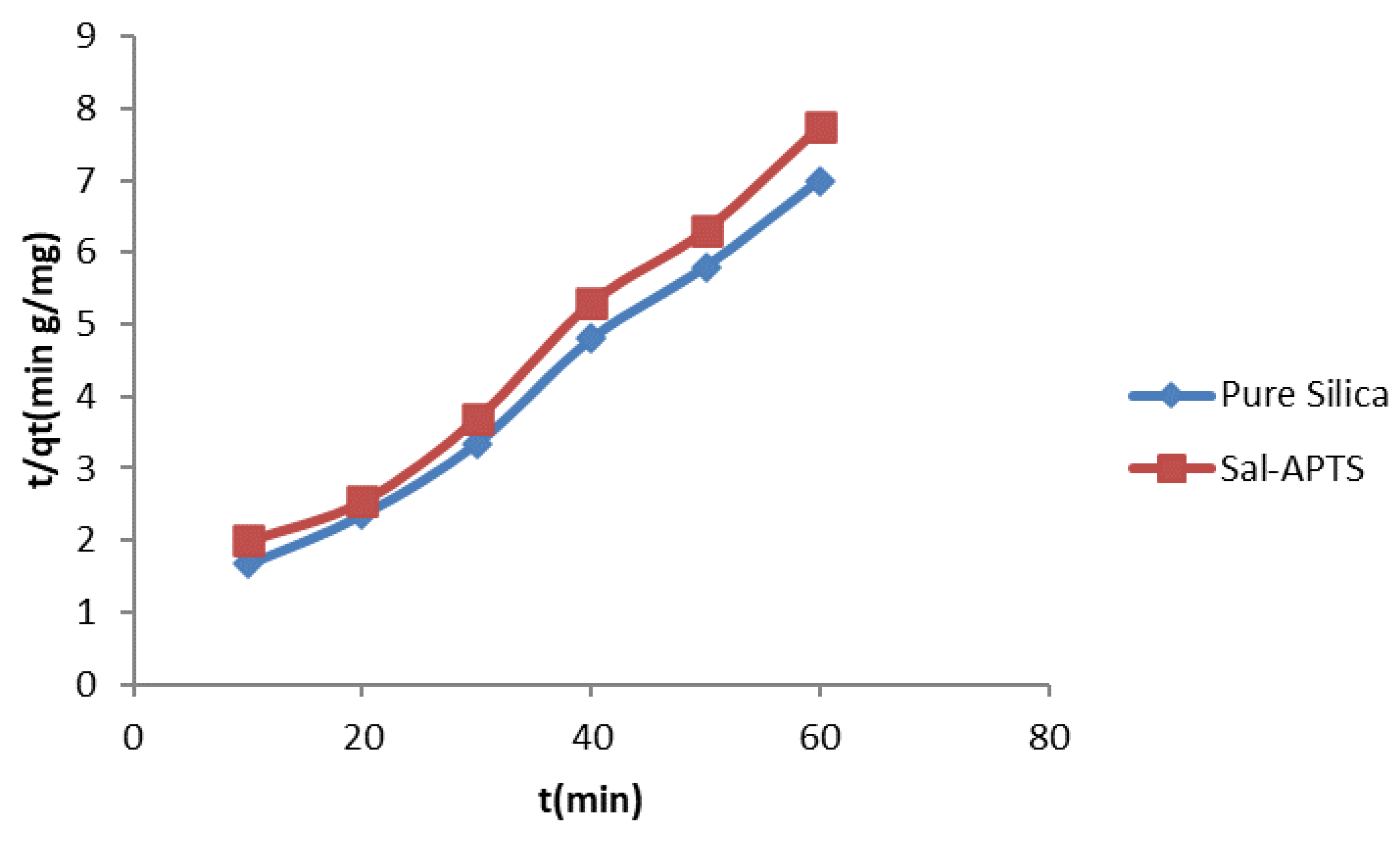

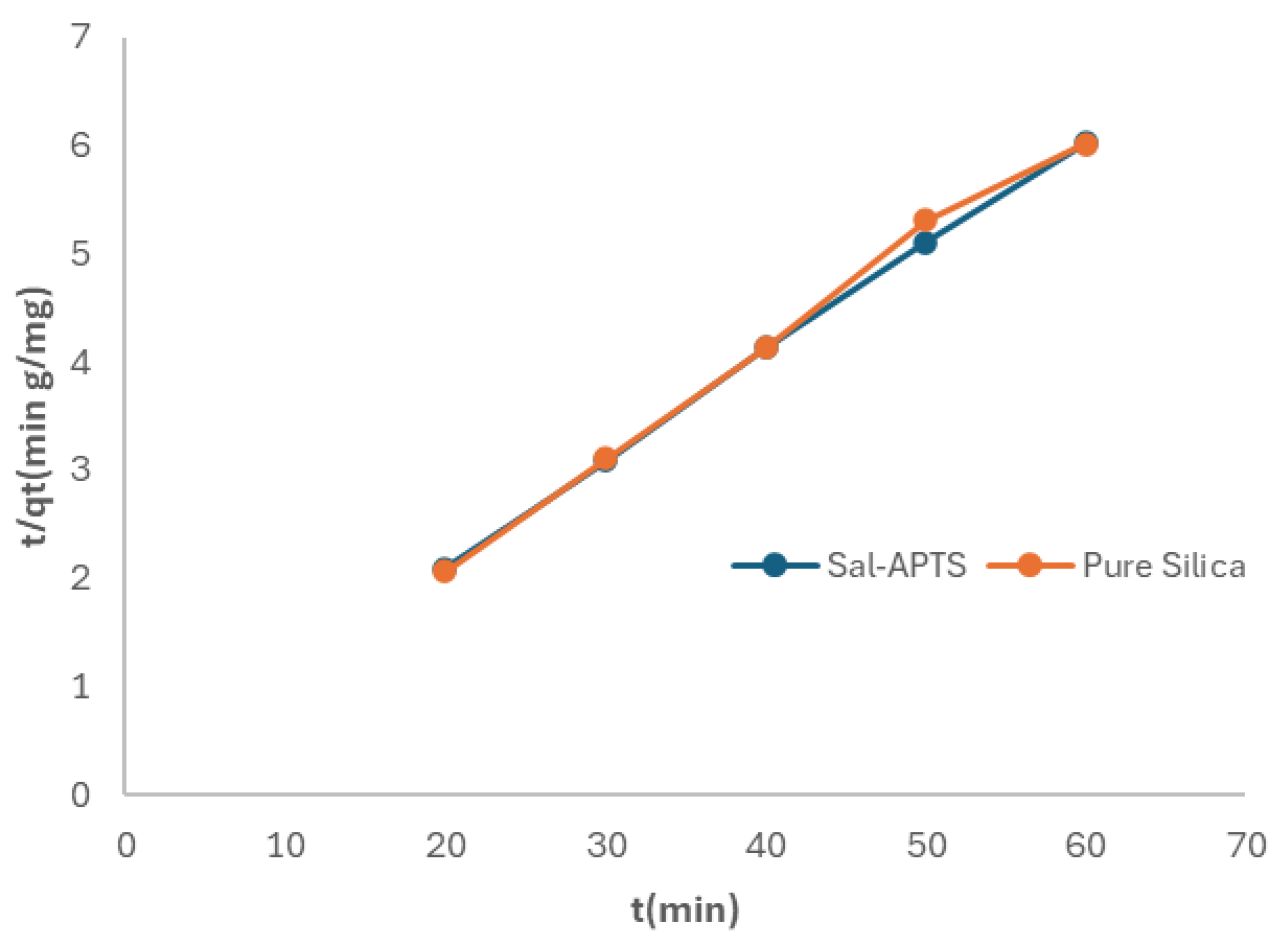

3.4. Adsorption Kinetics

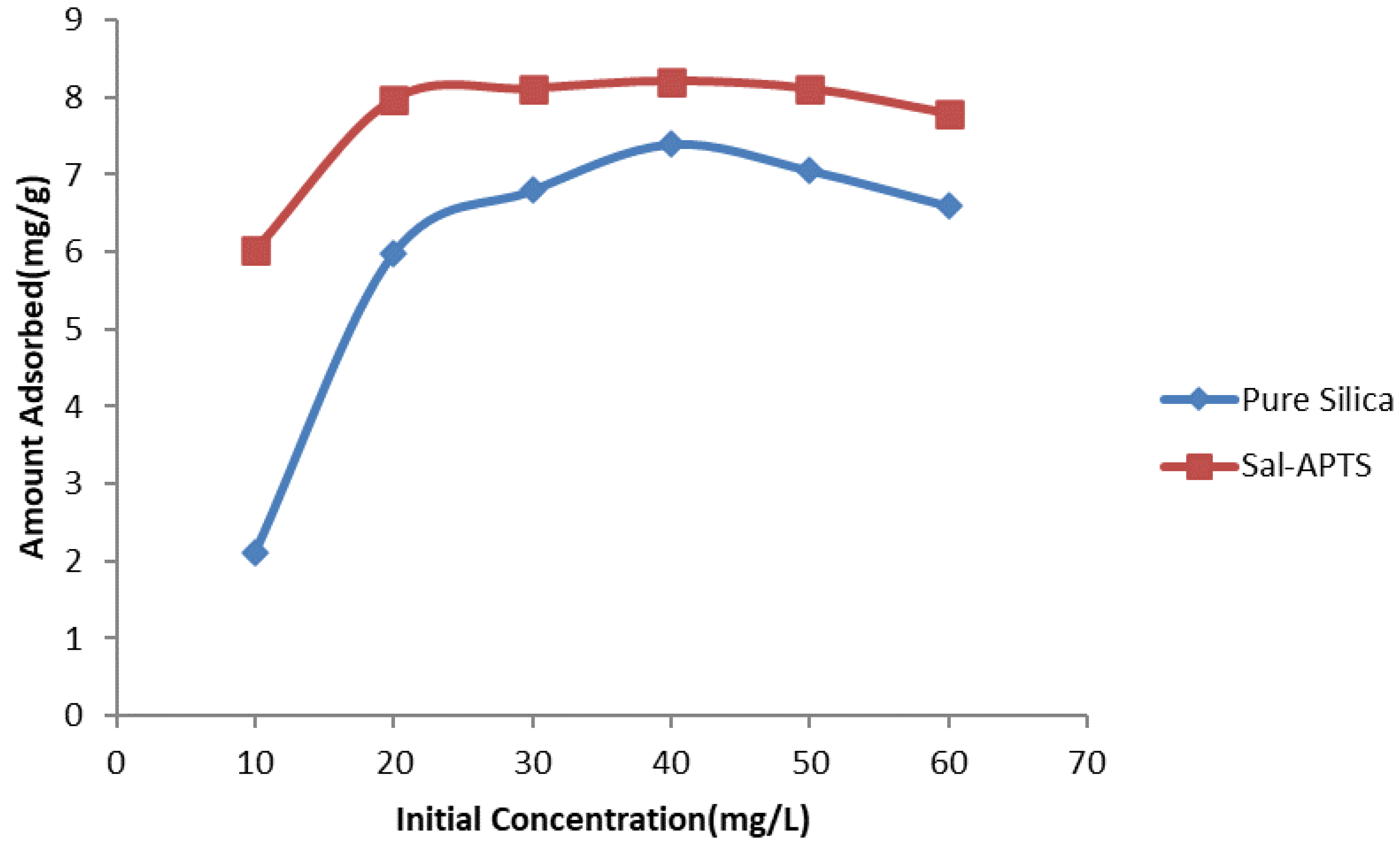

The kinetic property of the metal ions adsorbed onto the pure and functionalized silica were assessed (

Figure 10 and

Figure 11). The adsorption rates were found at pHs of 7 and 6 for pure silica and salicylaldehyde APTS respectively in the range of metal ions concentrations of 10-60 mg/L in aqueous media. Generally, the adsorption increased with increased concentration of the metal ions. At any given concentration, the metal ion adsorption quickly rose and then reached the plateau, which is the equilibrium capacity. In the two cases, the adsorption reached equilibrium capacity in 40 minutes.

Three kinetic models: Elovich, Pseudo first-order and Pseudo second order were applied in the analyses. In these cases, Elovich and pseudo first-order gave low correlation coefficient values. The pseudo second order which gave a high correlation coefficient was reported for the adsorption kinetic studies. The pseudo second-order reaction is guided by the expression:

where qe is the amount of metal ions adsorbed at equilibrium, qt is the amount of metal ions on the surface of the adsorbent at time t and k

2 is the rate constant of the pseudo second-order adsorption kinetics. A plot of (t/qt) against t yields a straight line if the pseudo second-order kinetics applied. The constants q

e and k

2 were determined from the slope and intercept of the plots respectively. The plots are shown in

Figure 12 and

Figure 13.

The kinetic data for the second-order assessment are listed in

Table 3 and

Table 4.

4. Discussion

The values of the linear regression coefficient, R

2, obtained from the Langmuir Isotherm parameters (

Table 1 and 2) showed that the isotherm gave the best fit for the experimental data. The moderate values of K

L obtained indicate a favorable adsorption process. The R

L values indicate the shape of the isotherm as expressed in equation 4:

R

L values between 0 and 1 indicate a favorable adsorption process [

18]. The values obtained in this study for Cd (II) and Cr (III) ions lie between 0 and 1. This low value that tends towards zero indicated that the adsorption process is almost irreversible [

19].

The pseudo-second-order kinetics also gave a high R

2 (

Table 3 and

Table 4). The high R

2 values signify a perfect description of the adsorbate-adsorbent interaction at the interface. It therefore suggests a possible exchange of valencies or sharing of electrons between the metal ions and the adsorbents surface leading to a chemical reaction. Removal efficiencies of the adsorbents followed the trend: Salicylaldehyde-APTS modified > Pure silica. This is because there are more functional groups in Salicylaldehyde modified silica than pure silica (

Scheme 1). The trend of adsorption of the two metal ions by the adsorbents showed that Cr (III) ions adsorbed more than Cd (II) ions. This could be because of the relatively smaller ionic radius of Chromium (0.62Å) compared to Cadmium (0.95Å) [

20]. The higher charge density of Cr (III) compared to Cd (II) means that Cr (III) can create stronger electrostatic attractions with negatively charged sites on the adsorbent. This could lead to more significant adsorption for Cr (III). In addition, higher charge density also means that Cr (III) can form more stable complexes with functional groups on the adsorbent surface, enhancing its adsorption.

5. Conclusion

The present study has established that pure and functionalized silica can adsorb metal ions from aqueous solutions. These silica-based adsorbents are good substrates for sequestering Cd (II) and Cr (III) ions from aqueous solutions and may be applied in the treatment of industrial waste waters and may be useful in detoxifying our already polluted environments.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization- Amanze, K.O.; Methodology- Ngozi-Olehi, L.C. and Uchegbu R.I.; Investigation, Ehirim A.I; Writing:original draft preparation- Okeke, P.; writing review and editing- Okore, G; Data curation- Enyoh, C.E. Supervision- Amanze, J.O. All authors have read and agreed to publish the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

In this section, you can acknowledge any support given which is not covered by the author contribution or funding sections. This may include administrative and technical support, or donations in kind (e.g., materials used for experiments).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Sodhi, K. K; Mishra, L. C; Chandra Kant Singh, C. K; Kumar, M. (2022). Perspective on the heavy metal pollution and recent, remediation strategies, Current Research in Microbial Sciences 3. [CrossRef]

- Osae, R; Nukpezah, D; Darko, D.A; Koranteng, S.S; Mensah, A (2023). Accumulation of heavy metals and human health risk assessment of vegetable consumption from a farm within the Korle lagoon catchment, Heliyon 9:1-16. [CrossRef]

- Mitra, S; Chakraborty, A. J; Tareq, A. M; Emran, T. B; Nainu, F; Khusro, A; Idris, A. M; Khandaker, M. U; Osman, H; Alhumaydhi, F. A & Simal-Gandara, J, (2022). Impact of heavy metals on the environment and human health: Novel therapeutic insights to counter the toxicity, Journal of King Saud University–Science, 34; -21. [CrossRef]

- Zaimee, M.Z.A.; Sarjadi, M.S.; Rahman, M.L. (2021). Heavy Metals Removal from Water by Efficient Adsorbents. Water, 2021, 13:1-21. [CrossRef]

- Srobodanka, S. , Katarina V.P., Milan P.N., Vladimir V.S and Marina S. (2022). Cerevisiae and Leuconostoc Mesenteroids immobilized in silica materials by two processing methods, Material Research, 25:1-15.

- Nnaji, N.D. , Onyeaka H., Miri T. and Ugwa C. (2023). Bioaccumulation for heavy metal removal: a review, S N Applied Sciences, 5:125. [CrossRef]

- Nazaripour, M. , Reshadi M.M., Mirbagheri S.A, Nazaripour M. and Bazargan A. (2021). Research trends of heavy metal removal from aqueous environments, Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 28:18, 22867-22884. [CrossRef]

- Rao, P.S. and Peddy M.V (2010). Different techniques for cadmium ion remediation. International Journal of Engineering Science and Technology, 2(7), 81–103.

- Al-Shahrani, S.O. , and Alshahrani A.M. (2021). Removal of chromium (II) and cadmium (II) heavy metal ions from aqueous solutions using treated date seeds: An eco-friendly method, Molecules 26 (12), 3718.

- Gupta, V.K. & Ali I. (2004). Removal of toxic metals from wastewater by adsorption on low-cost materials: A review. Journal of Hazardous Materials, B112 (1-2), 169-178.

- Mohan, D. & Singh K.P. (2002). Single-binary-, and multi-component adsorption of cadmium and Zinc using activated carbon derived from biogases-an agricultural waste material, Industrial and Engineering Chemistry Research, 4 (16), 3929-3938. [CrossRef]

- Ho, Y. S & McKay G. (1999). Pseudo-second order model for sorption processes. Process Biochemistry 34:451- 465. [CrossRef]

- Natalia, G. , Kobylinska, Vadim G., Kessler, Gulaim Seisenbaeva & Oksana A.D. (2022). In situ functionalized mesoporous silicas for sustainable remediation strategies in removal of inorganic pollutants from contaminated environmental water, American Chemical Society Omega, 7, 23576-23590. [CrossRef]

- Nishino, A. , Taki A., Asamotto H., Minamisawa, H. & Yamada K. (2022). Kinetic isotherm and equilibrium investigation of Cr (VI) ion adsorption in amine-functionalized porous silica beads, Polymers,14:2104. [CrossRef]

- Surucic, L. , Janjic G., Markovic B., Tadic T., Vukovic Z., Nastasovic A. & Onjia A. (2023). Speciation of hexavalent chromium in aqueous solutions using a magnetic silica-crated amino-modifiedglycidyl methacrylate Polymer Nanocomposite material, 16:2232. [CrossRef]

- Guevara-Lora, I. , Wronski N., Bialas A., Osip H. & Czosnek C. (2022). Efficient adsorption of chromium ions from aqueous solutions by plant-derived silica. Molecules 27:4171. [CrossRef]

- Mortazavi, K. , Ghaedi, M., Roosta, M. and Montazerozohori, M. (2012). Chemical functionalization of silica gel with 2-((3-silypropylimino) methyl) phenol (SPIMP) and its application for solid phase extraction and preconcentration of Fe (III), Pb(II), Cu(II), Ni(II), Co(II) and Zn(II) ions. Indian Journal of Science and Technology 5(1):1893-1900.

- Ajenifuja, E, Ajao, J.A., and Ajayi, E.O.B (2017). Adsorption Isotherm Studies of Cu(ii) and Co(ii) in High Concentration Aqueous Solutions on Photocatalytically Modified Diatomacceous Ceremic Adsorbents. Applied Water Science. [CrossRef]

- Emam, A.A. , Ismail, LF.M., Abdelkhalek, M.A. and Rehan, A. (2016). Adsorption Study of Some Heavy Metal Ions on Modified Kaolinite Clay. International Journal of Advancement in Engineering Technology, Management and Applied Science.

- Baig, T.H. , Garcia, A.E., Tiemann, K.J. and Gardea-Torresdey, J.L. (1999). Adsorption of heavy metal ions by the biomass of solanum elaeagnifolium (Silverleaf Night-Shade) roceedings of the 1999 Conference on Hazardous Waste Research, USA, 131-142. [Google Scholar]

Picture 1.

Preparation of Schiff-based immobilized silica.

Picture 1.

Preparation of Schiff-based immobilized silica.

Figure 1.

FTIR Analysis of Pure Silica.

Figure 1.

FTIR Analysis of Pure Silica.

Figure 2.

FTIR Analysis of Cadmium(II) ions bonded onto pure silica.

Figure 2.

FTIR Analysis of Cadmium(II) ions bonded onto pure silica.

Figure 3.

FTIR Analysis of Cadmium(II) ions bonded onto salicylaldehyde APTS.

Figure 3.

FTIR Analysis of Cadmium(II) ions bonded onto salicylaldehyde APTS.

Figure 4.

FTIR Analysis of Chromium(lll) ions bonded onto pure silica.

Figure 4.

FTIR Analysis of Chromium(lll) ions bonded onto pure silica.

Figure 5.

FTIR Analysis of Chromium(III) ions bonded onto salicylaldehyde APTS.

Figure 5.

FTIR Analysis of Chromium(III) ions bonded onto salicylaldehyde APTS.

Figure 6.

Cadmium (II) ions removal by pure and modified silica.

Figure 6.

Cadmium (II) ions removal by pure and modified silica.

Figure 7.

Chromium (II) ions removal by pure and modified silica.

Figure 7.

Chromium (II) ions removal by pure and modified silica.

Figure 8.

(a) Langmuir isotherm for the adsorption of Cd (II) ions onto pure silica. (b) Langmuir isotherm for the adsorption of Cr (III) ions onto pure silica.

Figure 8.

(a) Langmuir isotherm for the adsorption of Cd (II) ions onto pure silica. (b) Langmuir isotherm for the adsorption of Cr (III) ions onto pure silica.

Figure 9.

(a) Langmuir isotherm for the adsorption of Cd (II) ions onto Salicylaldehyde-APTS modified silica. (b) Langmuir isotherm for the adsorption of Cr (III) ions onto Salicylaldehyde APTS modified silica.

Figure 9.

(a) Langmuir isotherm for the adsorption of Cd (II) ions onto Salicylaldehyde-APTS modified silica. (b) Langmuir isotherm for the adsorption of Cr (III) ions onto Salicylaldehyde APTS modified silica.

Figure 10.

Variation of amount of Cd (II) ions adsorbed with initial concentration for adsorption onto pure and Salicylaldehyde-APTS modified silica.

Figure 10.

Variation of amount of Cd (II) ions adsorbed with initial concentration for adsorption onto pure and Salicylaldehyde-APTS modified silica.

Figure 11.

Variation of amount of Cr (III) ions adsorbed with initial concentration for adsorption onto pure and Salicylaldehyde- APTS modified silica.

Figure 11.

Variation of amount of Cr (III) ions adsorbed with initial concentration for adsorption onto pure and Salicylaldehyde- APTS modified silica.

Figure 12.

Pseudo second-order kinetics of adsorption of Cd (II) ions onto pure and modified silica.

Figure 12.

Pseudo second-order kinetics of adsorption of Cd (II) ions onto pure and modified silica.

Figure 13.

Pseudo second-order kinetics of adsorption of Cr (III) ions onto pure and modified silica.

Figure 13.

Pseudo second-order kinetics of adsorption of Cr (III) ions onto pure and modified silica.

Table 1.

Langmuir Isotherm parameters of Cd (II) and Cr (III) ions on pure silica.

Table 1.

Langmuir Isotherm parameters of Cd (II) and Cr (III) ions on pure silica.

| |

qm (mg/g)

|

KL

|

R2

|

RL

|

| Cadmium (II) |

0.1266 |

-0.1461 |

0.9993 |

0.121 |

| Chromium (III) |

0.1582 |

-0.0626 |

0.9350 |

0.242 |

Table 2.

Langmuir Isotherm parameters of Cd (II) ions on Salicylaldehyde-APTS modified silica.

Table 2.

Langmuir Isotherm parameters of Cd (II) ions on Salicylaldehyde-APTS modified silica.

| |

qm (mg/g)

|

KL

|

R2

|

RL

|

| Cadmium (II) |

0.1498 |

0.6860 |

0.9602 |

0.030 |

| Chromium (III) |

0.3278 |

0.7572 |

0.9770 |

0.026 |

Table 3.

Pseudo second-order kinetic data of pure silica.

Table 3.

Pseudo second-order kinetic data of pure silica.

| |

k2[g/ (min mg)] |

qe(mg/g) |

R2 |

| Cadmium (II) |

0.7233 |

0.1024 |

0.9923 |

| Chromium (III) |

0.2787 |

0.0957 |

0.9986 |

Table 4.

Pseudo second-order kinetic data of Salicylaldehyde-APTS modified.

Table 4.

Pseudo second-order kinetic data of Salicylaldehyde-APTS modified.

| |

k2[g/ (min mg)] |

qe(mg/g) |

R2 |

| Cadmium (II) |

0.0400 |

0.1261 |

0.9835 |

| Chromium (III) |

0.2607 |

0.0973 |

0.9959 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).