1. Introduction

Fixational eye movements refer to a series of spontaneous, controlled, and autonomous eyeball movements that are important for holding the central visual field on a target for a certain period. Fixation disparity is an important measure in the study of fixational eye movements and binocular vision. It refers to the small misalignment of the eyes when trying to fixate on a single point. This misalignment is usually too small to cause double vision but can be an indicator of how well the eyes work together to maintain focus[

1,

2].

Research has shown that fixation disparity is closely related to the dynamics of vergence eye movements, which are responsible for aligning the eyes in response to differences in the position of objects[

3,

4]. For instance, fixation disparity has been described as a steady-state error of vergence, meaning it reflects a residual error after the eyes have attempted to correct for disparity[

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11].

Strabismus during developmental phases can result in abnormal visual experiences in both eyes, disrupting normal binocular visual function[

12,

13]. Previous studies have reported abnormal fixational eye movements in patients with strabismus[

14,

15]. While laboratory eye-tracking equipment for measuring fixational eye movements provides high temporal and spatial resolution along with a variety of metric data, these systems are often prohibitively expensive and complex, rendering them impractical for everyday clinical use[

16].

Therefore, we proposed a low-cost and easy-to -use method to assess fixational disparities as an indicator of fixational eye movements by a binocular eye-tracking technique in children with strabismus and normal children, as well as in children with strabismus before and after correction surgery.

2. Materials and Methods

Participants

This study included pediatric participants, aged 4 to 18 years, who presented to the Department of Ophthalmology at West China Hospital of Sichuan University be-tween June 1, 2020, and December 31, 2022. The participants were divided into two groups: the strabismus group and control groups. All participants were Chinese. The children were provided with age-appropriate information about the study. The assent was obtained either through verbal or written assent (if applicable). Written informed consent was obtained from the guardians/parents prior to the children's participation in the study. The study complied with the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Institutional Review Board of West China Hospital of Sichuan University.

Design

All participants underwent a comprehensive eye examination, including visual acuity with the Standard Logarithm Visual Acuity Chart (arithmetic scaled high con-trast E optotype; the only type of chart available to us at the clinic), refractive errors with a cycloplegic refraction (1% atropine for esotropia, 0.5% tropicamide for exo-tropia and normal children), ocular alignment with a prism plus alternate cover test, anterior segment examination with the slit lamp, stereopsis with the Titmus Stereo Test (Stereo Optical Co, Inc), fundus examination, and eye movement functions (be-fore cycloplegia) with the binocular paradigm proposed in this study.

In strabismus group, stereoacuity was measured before and after surgery. The participants were included in the study only if they had no history of ocular trauma or ocular patholo-gy (e.g., nystagmus, cataract, ptosis), no systemic diseases (self-reported), no atten-tional dysfunctions such as attention deficit disorder (ADD) or other neurological dysfunctions (e.g., concussion, learning disabilities) , no history of intraocular sur-gery, and no amblyopia (according to the Amblyopia “PPP” guideline, 2022 (Hutchinson et al. 2023)) and demonstrated sufficient cooperation with the examina-tions.

Inclusion criteria

Strabismus group: 1) Participants who were diagnosed with concomitant strabis-mus, including concomitant esotropia and concomitant exotropia. 2) Participants who had a good post-surgery ocular alignment (disparity degree ≤ ±8△ at 6 m and 33 cm fixation). 3) Participants who completed at least one postoperative follow-up. Control group: Participants who had a normal ocular position (disparity degree ≤ ±5△ at 6 m and 33 cm fixation) and normal binocular eye movement function.

Materials

A Tobii Eye Tracker 5 (Tobii, Stockholm, Sweden) was employed for detecting fixational disparities. The experiment took place in a quiet and private room with a natural and constant luminance. A 32-inch 3-dimension (3D) monitor (resolution 1920×1080 pixels at a refresh frequency of 120 Hz and a spatial resolution of 0.3 degrees (minimum 0.1 degrees); LG Electronics, Seoul, Korea) was used to present stimuli at a viewing distance of 80 cm. Subjects were asked to wear 3D polarized glasses with spectacle correction (if any) and seated on a non-wheeled but height-adjustable chair with the eyes at the same level as the screen center. Gaze positions were recorded with a 120 Hz remote eye tracker.

Inspection Procedure

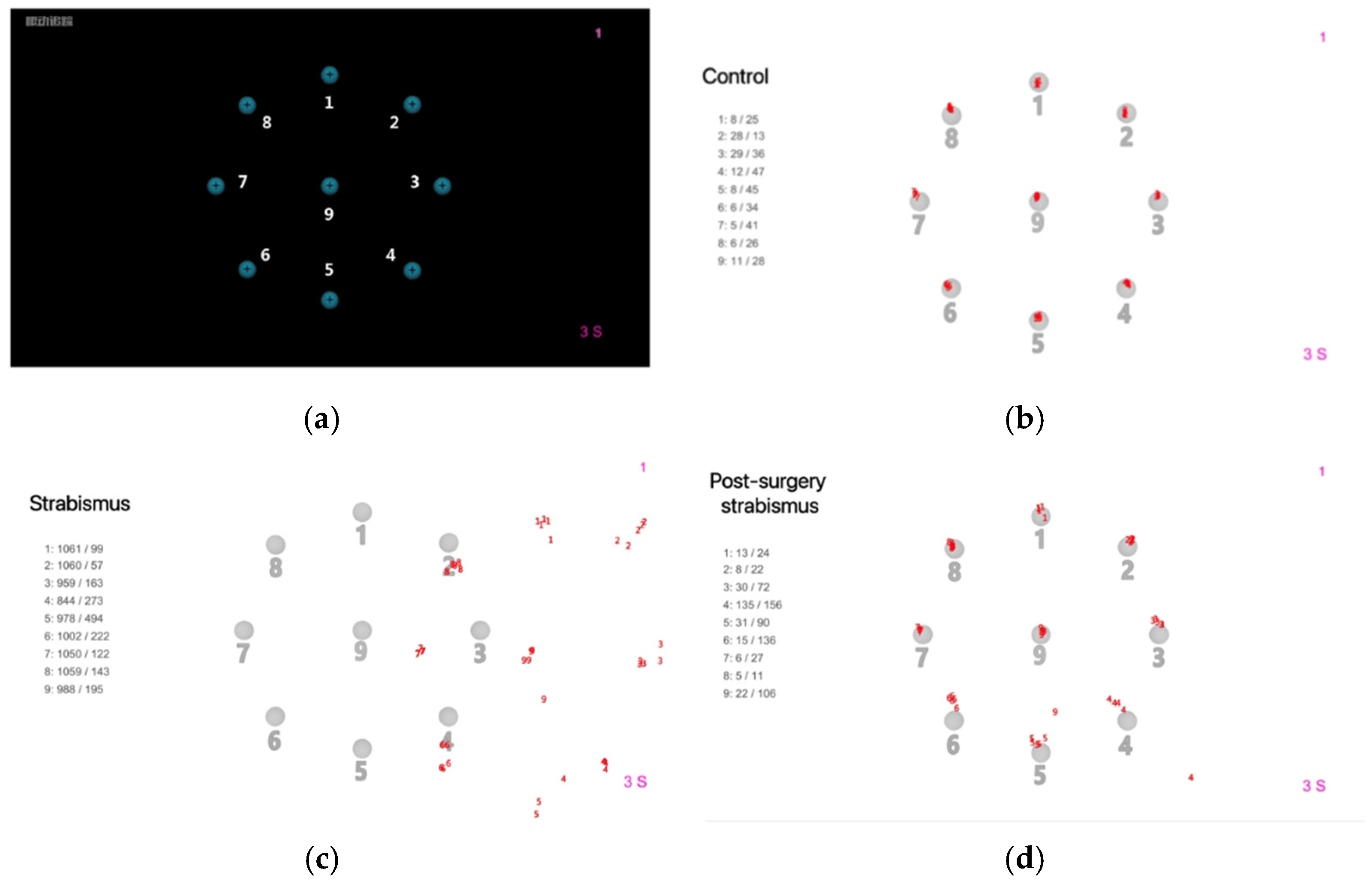

The fixational disparities were measured under static binocular-viewing condition. The subjects were instructed to fixate their gaze on a target on a black background, which was a bright blue dot (1.4° diameter) with a black cross-shaped center. The target appeared in a fixed order at 9 locations, 8 locations on a peripherical circle (8.3° radius) and 1 location in the center. It remained for 3 s on each location and automatically switched to the next location; however, data recording at each location was manually started by the experimenter once ensuring that the subject’s fixation had changed and sustained on the target. At each target location, the eye tracker cu-mulatively extracted 10 samples from all gaze positions it grabbed. The mean hori-zontal and vertical disparities of these 10 gaze positions relative to the target location were calculated for each eye individually and recorded as the binocular mean values (

Figure 1a-b).

In strabismus group, the fixational disparities were detected before surgery and done again one month later after surgery. The mean horizontal/vertical deviations (pixels) from both eyes were calculated respectively for 9 locations. The red numbers around the center of each location were the gaze positions extracted during the test. The strabismus participant showed significant fixational disparities, while the participant after strabismus surgery showed similar results with the control (

Figure 1c-d).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed by using SPSS (version 26.0, IBM Corp., Ar-monk, NY, USA). The number of shifted pixels in fixational disparities was treated as n-dimensional data and expressed as the mean [standard disparity]. For data that did not follow a normal distribution, the Mann–Whitney U test was employed for statistical analysis. Paired sample tests were used to compare internal data differ-ences within the same group. Differences were considered statistically significant at P<0.05.

3. Results

This study recruited 117 participants. The control group is comprised of 60 participants with an average age of 7.37 [0.20] years, including 26 males (43.3%) and 34 females (56.7%). The strabismus group consisted of 57 individuals with an average age of 7.76 [3.59] years, including 36 males (62.1%) and 21 females (37.9%). There were no statistically significant differences in age (P=0.82) and sex (P=0.78) between the two groups (

Table 1).

The results of the Titmus stereo test showed that the average score of stereoacuity for the strabismus group before surgery was 243.38″ [40.44], compared with 50.33″ [4.83] for the control group. The score of the strabismus group was significantly higher than that of the control group (P=0.02). In the strabismus group, the preoperative score was higher than the postoperative score (221.29 ″ [40.19]), and the difference was statistically significant (P<0.001) (

Table 2).

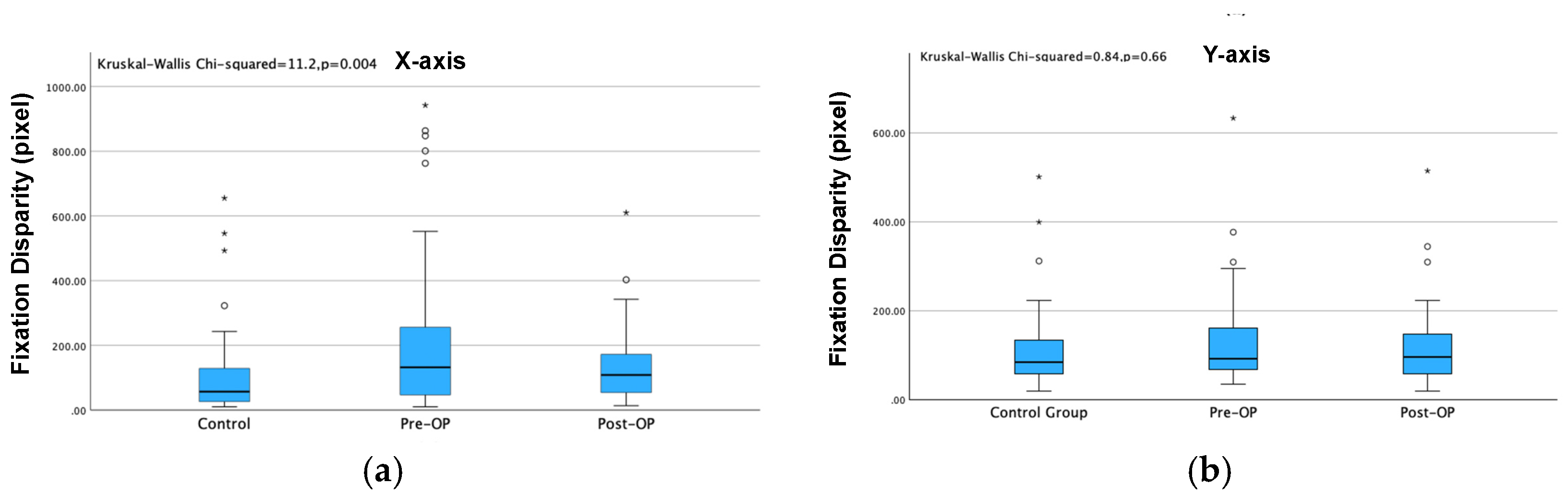

Kruskal–Walli’s test was used for comparison among the three groups, in which P values < 0.001 (represented by ***) and P values < 0.01 (represented by **) indicated significant differences in pairwise comparison, and P value > 0.05 indicated no significant differences. The average disparity for both the X-axis and Y-axis of the strabismus group was significantly larger than that of the control group before surgery (P<0.001). The X-axis disparity showed significant difference after the surgery while Y-axis disparity showed no significant difference after strabismus surgery. (

Figure 3)

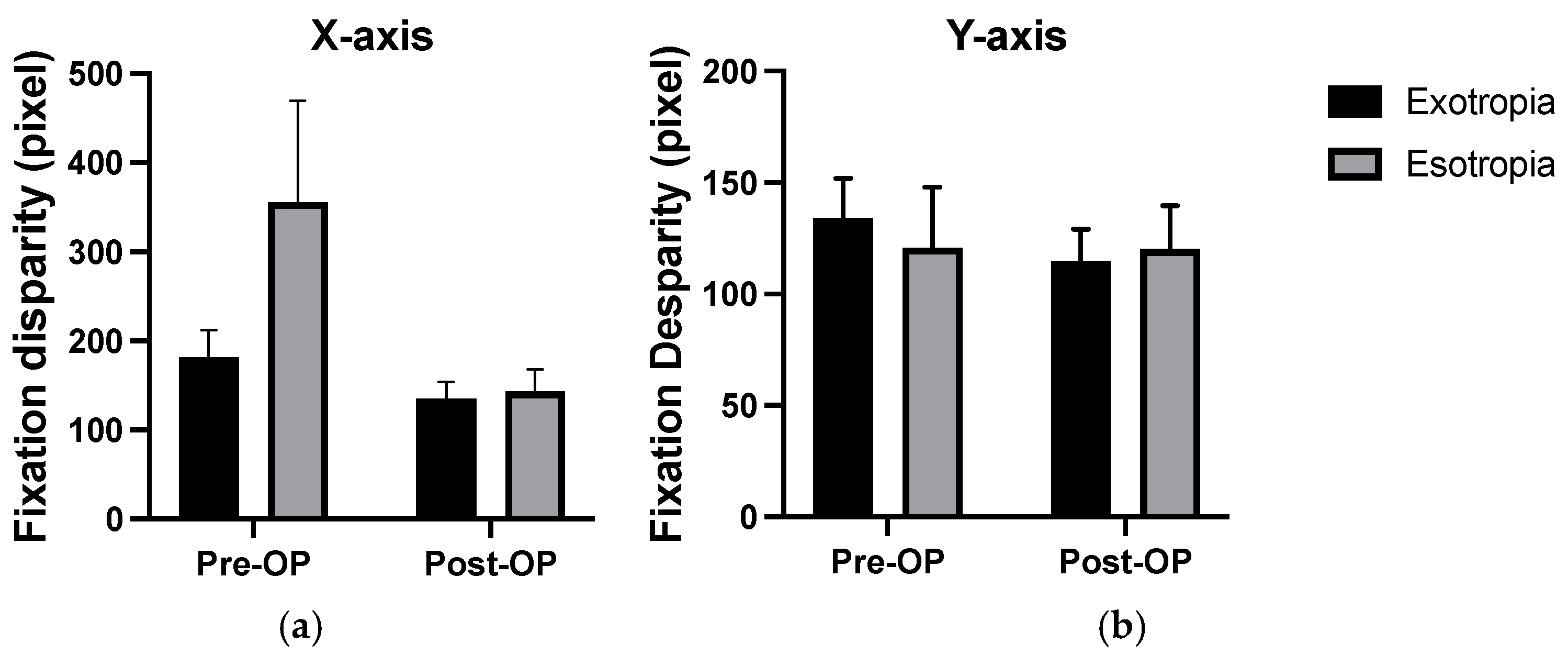

In strabismus group, the average disparity on the X-axis of patients with exotropia was significantly smaller than that of patients with esotropia before surgery (P=0.004), while no significant difference was observed after surgery (P=0.84) (

Table 3).

Comparison of the main outcome measures across groups. X-axis/ Y-axis: pixel along horizontal/vertical axis in the fixational disparity test (error bars means standard deviation). In horizontal (X-axis) fixation, the average score of patients with exotropia was significantly smaller than that of patients with esotropia before surgery, although no significant difference was observed post-surgery. In vertical(Y-axis) fixation, no significant differences were found between patients with exotropia and patients with esotropia both pre- and post-surgery (

Figure 4).

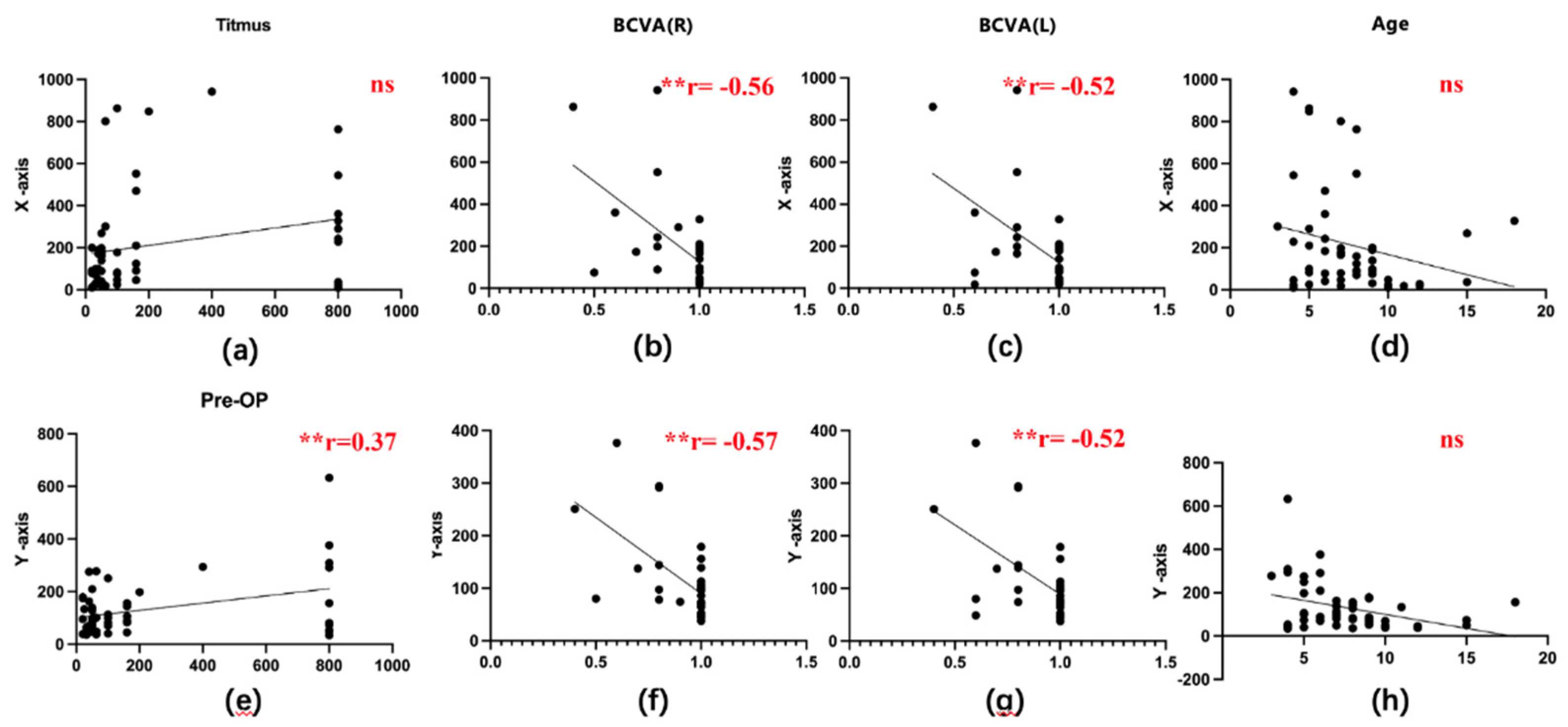

Pearson correlation analysis was performed between fixational disparities and various clinical characteristics, including age, best corrected vision acuity (BCVA), and stereoacuity. The distribution plots of each variable are shown on the diagonal. Significant correlations were denoted as ***, **, and * for P values < 0.001, < 0.01, and < 0.05, respectively. A significant negative correlation was observed between binocular BCVA and fixational disparities (

Figure 5b–c, g–h). However, no significant correlations were revealed between other clinical characteristics (including age and stereoacuity) and fixational disparities (

Figure 5a, d, e, and i).

4. Discussion

Authors should discuss the results and how they can be interpreted from the perspective of previous studies and of the working hypotheses. The findings and their implications should be discussed in the broadest context possible. Future research directions may also be highlighted.

Fixational eye movements entail slow oscillations of the eyes controlled by subcortical and cortical brain areas [

17]. Precise oculomotor control ensures the central placement of the visual target on the fovea, crucial for optimal visual acuity[

18]. Fixational eye movements, which include micro saccades, drifts, and tremors, play a role in fine-tuning this alignment. Studies have found that these tiny eye movements are generally conjugate, meaning they move together in both eyes, and they help in reducing fixation disparity by correcting for small misalignments[

19,

20,

21,

22].

Strabismus patients often experience reduced visual acuity, which is linked to impaired eye movement control[

23,

24]. Some studies have found that strabismus patients may develop specific neural adaptation mechanisms over time to cope with abnormal eye movement patterns[

25,

26]. In severe cases of strabismus, patients may lose normal binocular vision, leading to significant abnormalities in their eye movement patterns[

27,

28,

29].

Zhou et al. utilized the binocular eye-tracking technique to investigate eye movement functions in children with amblyopia and recovering amblyopia successfully[

30]. In our study, we applied the same binocular eye tracking technique to quantitatively evaluate fixational disparities in children with strabismus and normal children, as well as in those with strabismus before and after correction surgery. Disparities of sustained relative to the target were measured as the mean from both eyes. We found significantly increased fixational disparities in children with strabismus compared with that in the normal group, aligning with other studies on fixational eye movements in strabismus[

31,

32,

33].

Comparing esotropia and exotropia in the strabismus group, we found less fixational disparities in children with exotropia, which may be due to that there were more patients with intermittent exotropia in exotropia, who had better binocular vision function and better fixation[

34]. In addition, our study also evaluated fixational disparities in strabismic children after strabismus surgery to explore whether fixational eye movement deficits would be restored by strabismus surgery in childhood[

13,

35,

36,

37]. In the present study, we found that fixational disparities were significantly diminished in the horizontal direction after strabismus surgery. This finding robustly confirms the notion that strabismus surgery improves binocular coordination in patients and that the significant improvement in horizontal direction might be attributed to the predominance of horizontal strabismus cases in this study[

38].

Prior research has indicated that strabismus can impact stereopsis, and strabismus surgery can restore binocular balance then improve stereopsis[

39]. In the present study, we found that both fixational disparities and stereopsis of strabismus group were markedly worse than those of control group. Moreover, we also found a notable improvement in both fixational disparities and stereopsis after strabismus surgery in patients with strabismus, which was consistent with previous study. Although the stereoacuity of the strabismus was significantly improved after surgery, it was still worse than that of the normal, which might be due to some psychological factors and other factors including suppression of one eye, limiting binocular input even after alignment, residual eye misalignment and adaptation difficulty [

40,

41,

42,

43,

44]. Additionally, we found no significant correlation between fixational disparities and stereopsis in the strabismus group, which indicated the need for further investigation in larger and more diverse patient groups.

Furthermore, a significant negative correlation was observed between BCVA and fixational disparities in this study. Most studies report a positive interaction between BCVA and fixational eye movements in patients with amblyopia[

30,

45]. To our knowledge, it is the first to identify this correlation in strabismic children, and this result suggests that strabismic children with better BCVA may exhibit less fixational disparities. Additionally, there was no significant interaction between age and fixational disparities, which may be due to the complex interplay among strabismus, visual development, and the variable intervals from abnormal visual experiences to the initiation of treatment.

This study surely has some limitations. Firstly, the sample size is limited, but the aim of this preliminary research is to identify trends that warrant further investigation in future clinical trials or large-scale prospective observational studies. Secondly, compared to the EyeLink, a high-resolution eye tracker with a sampling rate of 500–2000Hz, the Tobii eye tracker 5 with lower sampling rate is unsuitable for tasks requiring precise temporal measurements like saccadic kinematics or other temporal measurements, but is suitable for pupil measurement and spatial outcome measures like fixational disparities[

31,

46]. For future research, a direct comparison between Tobii eye tracker 5 and EyeLink in various visual tasks could offer stronger evidence.

To our knowledge, this study is the first to use an eye-tracking device to track preoperative and postoperative fixational disparities among patients with strabismus. We successfully utilized the low-cost eye-tracking device to identify abnormal fixational eye movement patterns in these patients and found that fixational functions can be significantly improved in the horizontal direction through surgical intervention.

5. Conclusions

In this study, we quantitatively analyzed the impact of strabismus and strabismus surgery on fixational disparities by the binocular eye-tracking technique. The results of our study showed that children with strabismus exhibited more significant fixational disparities than the normal group. Moreover, fixational disparities were significantly diminished after strabismus surgery. The present results highlight the value of binocular assessment of fixational disparities in strabismus management.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.Y.H. and Y.C.L.; methodology, X.Y.H.; software, B.J.C.; validation, B.J.C. and X.B.Y.; formal analysis, X.Y.H.; investigation, X.B.Y.; resources, Y.C.L.; data curation, B.J.C. and X.B.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, X.Y.H.; writing—review and editing, X.B.Y.; funding acquisition, Y.C.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by NATURAL SCIENCE FOUNDATION OF SICHUAN PROVINCE, grant number 23NSFSC0856 and 2024NSFSC1553. This study was also partly supported by the China Scholarship Council (grant no. 202306240077).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of West China Hospital of Sichuan University.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient(s) to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| SD |

Standard deviation |

| Sig. |

Significant |

| Pre-OP |

Preoperative |

| Post-OP |

Postoperative |

| BCVA |

Best corrected vision acuity |

| L |

Left |

| R |

Right |

References

- Duchesne, J.; Coubard, O.A. Measuring vergence and fixation disparity in 3D space. Eur J Neurosci 2021, 53, 1473–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rigas, I.; Friedman, L.; Komogortsev, O. Study of an Extensive Set of Eye Movement Features: Extraction Methods and Statistical Analysis. J Eye Mov Res 2018, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Traxler, M.J.; Long, D.L.; Tooley, K.M.; Johns, C.L.; Zirnstein, M.; Jonathan, E. Individual Differences in Eye-Movements During Reading: Working Memory and Speed-of-Processing Effects. J Eye Mov Res 2012, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poffa, R.; Joos, R. The influence of vergence facility on binocular eye movements during reading. J Eye Mov Res 2019, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Wu, X.; Zheng, C.; Zhao, Y.; Gao, J.; Deng, Z.; Zhang, X.; Chen, J. Effects of Vergence Eye Movement Planning on Size Perception and Early Visual Processing. J Cogn Neurosci 2024, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaschinski, W. Individual Objective and Subjective Fixation Disparity in Near Vision. PLoS One 2017, 12, e0170190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alvarez, T.L.; Kim, E.H.; Yaramothu, C.; Granger-Donetti, B. The influence of age on adaptation of disparity vergence and phoria. Vision Res 2017, 133, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canessa, A.; Gibaldi, A.; Chessa, M.; Fato, M.; Solari, F.; Sabatini, S.P. A dataset of stereoscopic images and ground-truth disparity mimicking human fixations in peripersonal space. Sci Data 2017, 4, 170034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aizenman, A.M.; Koulieris, G.A.; Gibaldi, A.; Sehgal, V.; Levi, D.M.; Banks, M.S. The Statistics of Eye Movements and Binocular Disparities during VR Gaming: Implications for Headset Design. ACM Trans Graph 2023, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balaban, C.D.; Nayak, N.S.; Williams, E.C.; Kiderman, A.; Hoffer, M.E. Frequency dependence of coordinated pupil and eye movements for binocular disparity tracking. Front Neurol 2023, 14, 1081084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schroth, V.; Joos, R.; Alshuth, E.; Jaschinski, W. Effects of aligning prisms on the objective and subjective fixation disparity in far distance. J Eye Mov Res 2019, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Haddad, C.; Hoyeck, S.; Torbey, J.; Houry, R.; Boustany, R.M.N. Eye Tracking Abnormalities in School-Aged Children With Strabismus and With and Without Amblyopia. J Pediat Ophth Strab 2019, 56, 297–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihara, M.; Hayashi, A.; Kakeue, K.; Tamura, R. Changes in saccadic eye movement and smooth pursuit gain in patients with acquired comitant esotropia after strabismus surgery. J Eye Mov Res 2023, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Economides, J.R.; Adams, D.L.; Horton, J.C. Variability of Ocular Deviation in Strabismus. JAMA Ophthalmol 2016, 134, 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.H.; Fu, H.; Lo, W.L.; Chi, Z.; Xu, B. Eye-tracking-aided digital system for strabismus diagnosis. Healthc Technol Lett 2018, 5, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iwata, Y.; Handa, T.; Ishikawa, H. Objective measurement of nine gaze-directions using an eye-tracking device. J Eye Mov Res 2020, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kowler, E. Eye movements: the past 25 years. Vision Res 2011, 51, 1457–1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Putnam, N.M.; Hofer, H.J.; Doble, N.; Chen, L.; Carroll, J.; Williams, D.R. The locus of fixation and the foveal cone mosaic. J Vis 2005, 5, 632–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jainta, S.; Hoormann, J.; Kloke, W.B.; Jaschinski, W. Binocularity during reading fixations: Properties of the minimum fixation disparity. Vision Res 2010, 50, 1775–1785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jainta, S.; Jaschinski, W.; Wilkins, A.J. Periodic letter strokes within a word affect fixation disparity during reading. J Vis 2010, 10, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svede, A.; Hoormann, J.; Jainta, S.; Jaschinski, W. Subjective fixation disparity affected by dynamic asymmetry, resting vergence, and nonius bias. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2011, 52, 4356–4361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otero-Millan, J.; Macknik, S.L.; Martinez-Conde, S. Fixational eye movements and binocular vision. Front Integr Neurosci 2014, 8, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walton, M.M.; Ono, S.; Mustari, M. Vertical and oblique saccade disconjugacy in strabismus. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2014, 55, 275–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weiss, A.H.; Kelly, J.P.; Hopper, R.A.; Phillips, J.O. Crouzon Syndrome: Relationship of Eye Movements to Pattern Strabismus. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2015, 56, 4394–4402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moon, Y.; Lee, W.J.; Shin, S.H.; Lee, J.Y.; Lee, S.J.; Ko, B.W.; Lim, H.W. Quantitative Analysis of Translatory Movements in Patients With Horizontal Strabismus. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2021, 62, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeh, P.H.; Liu, C.H.; Sun, M.H.; Chi, S.C.; Hwang, Y.S. To measure the amount of ocular deviation in strabismus patients with an eye-tracking virtual reality headset. BMC Ophthalmol 2021, 21, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zipori, A.B.; Colpa, L.; Wong, A.M.F.; Cushing, S.L.; Gordon, K.A. Postural stability and visual impairment: Assessing balance in children with strabismus and amblyopia. PLoS One 2018, 13, e0205857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denniss, J.; Scholes, C.; McGraw, P.V.; Nam, S.H.; Roach, N.W. Estimation of Contrast Sensitivity From Fixational Eye Movements. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2018, 59, 5408–5416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Haddad, C.; Hoyeck, S.; Torbey, J.; Houry, R.; Boustany, R.N. Eye Tracking Abnormalities in School-Aged Children With Strabismus and With and Without Amblyopia. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus 2019, 56, 297–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.; Bian, H.; Yu, X.; Wen, W.; Zhao, C. Quantitative assessment of eye movements using a binocular paradigm: comparison among amblyopic, recovered amblyopic and normal children. BMC Ophthalmol 2022, 22, 365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ivanchenko, D.; Rifai, K.; Hafed, Z.M.; Schaeffel, F. A low-cost, high-performance video-based binocular eye tracker for psychophysical research. J Eye Mov Res 2021, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xin, L.; Bin, Z.; Xiaoqin, D.; Wenjing, H.; Yuandong, L.; Jinyu, Z.; Chen, Z.; Lin, W. Detecting Task Difficulty of Learners in Colonoscopy: Evidence from Eye-Tracking. J Eye Mov Res 2021, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leube, A.; Rifai, K.; Rifai, K. Sampling rate influences saccade detection in mobile eye tracking of a reading task. J Eye Mov Res 2017, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.W.; Lin, S.A.; Lin, P.W.; Huang, H.M. The difference of surgical outcomes between manifest exotropia and esotropia. Int Ophthalmol 2019, 39, 1427–1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodsky, M.C.; Fray, K.J. Dissociated horizontal deviation after surgery for infantile esotropia: clinical characteristics and proposed pathophysiologic mechanisms. Arch Ophthalmol 2007, 125, 1683–1692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellis, G.S., Jr.; Pritchard, C.H.; Baham, L.; Babiuch, A. Medial rectus surgery for convergence excess esotropia with an accommodative component: a comparison of augmented recession, slanted recession, and recession with posterior fixation. Am Orthopt J 2012, 62, 50–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pullela, M.; Degler, B.A.; Coats, D.K.; Das, V.E. Longitudinal Evaluation of Eye Misalignment and Eye Movements Following Surgical Correction of Strabismus in Monkeys. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2016, 57, 6040–6047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maneschg, O.A.; Barboni, M.T.S.; Nagy, Z.Z.; Nemeth, J. Fixation stability after surgical treatment of strabismus and biofeedback fixation training in amblyopic eyes. Bmc Ophthalmol 2021, 21, 264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, J.; Levi, D.M. Recovery of stereopsis through perceptual learning in human adults with abnormal binocular vision. P Natl Acad Sci USA 2011, 108, E733–E741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Xu, M.; Zhang, J.; Zhou, J.; Wan, M.; Dai, Z.; Peng, T.; Min, S.H.; Hou, F.; Zhou, J.; et al. Can Clinical Measures of Postoperative Binocular Function Predict the Long-Term Stability of Postoperative Alignment in Intermittent Exotropia? J Ophthalmol 2020, 2020, 7392165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, Y.J.; Park, Y.Y.; Chung, Y.W.; Park, S.H.; Shin, S.Y. Surgical and sensory outcomes in patients with intermittent exotropia according to preoperative refractive error. Eye (Lond) 2019, 33, 1314–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurup, S.P.; Barto, H.W.; Myung, G.; Mets, M.B. Stereoacuity outcomes following surgical correction of the nonaccommodative component in partially accommodative esotropia. J AAPOS 2018, 22, 92–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leffler, C.T.; Vaziri, K.; Schwartz, S.G.; Cavuoto, K.M.; McKeown, C.A.; Kishor, K.S.; Janot, A.C. Rates of Reoperation and Abnormal Binocularity Following Strabismus Surgery in Children. Am J Ophthalmol 2016, 162, 159–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.; Fan, Y.; Chu, H.; Yan, L.; Wiederhold, B.K.; Wiederhold, M.; Liao, Y. Preliminary Study of Short-Term Visual Perceptual Training Based on Virtual Reality and Augmented Reality in Postoperative Strabismic Patients. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw 2022, 25, 465–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, S.L.; Beylergil, S.B.; Otero-Millan, J.; Shaikh, A.G.; Ghasia, F.F. Fixational Eye Movement Waveforms in Amblyopia: Characteristics of Fast and Slow Eye Movements. J Eye Mov Res 2019, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raju, M.H.; Friedman, L.; Bouman, T.M.; Komogortsev, O.V. Filtering Eye-Tracking Data From an EyeLink 1000: Comparing Heuristic, Savitzky-Golay, IIR and FIR Digital Filters. J Eye Mov Res 2021, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).