Introduction

Traditionally regarded as a passive solvent, water’s role extends beyond merely providing a medium for biochemical reactions since its structural and dynamic properties enable active participation in biological phenomena (Dargaville and Hutmacher, 2022). The structural heterogeneity of liquid water arises from the continuous assembly and disassembly of hydrogen bonds, forming diverse geometric configurations that reflect water’s branched polymeric nature (Shiotari and Sugimoto, 2017). These configurations, termed water micro assemblies (WMA), have been extensively studied under extreme conditions, such as supercritical water (Skarmoutsos and Samios, 2016), high-pressure crystals in supercooled water (Kim et al., 2009; Lin et al., 2018), frozen water confined within nanometric slit pores (Koga et al., 2020) or nanochannels formed by cubic crystalline phases (Das et al., 2019). However, relatively little attention has been given to the microstructure of liquid water at ambient temperature and pressure. Under standard conditions, each water molecule forms up to four hydrogen bonds, creating a tetrahedral structure (Fanetti et al., 2014; Liu et al., 2017; Milovanović et al., 2020). Fluctuations in hydrogen bond numbers, ranging from 2 to 6, result in molecules being either “loosely” or “tightly” bound (Thaomola et al., 2017). Liquid water has been described as a dynamic mixture of pentagonal and hexagonal rings (Shiotari and Sugimoto, 2017; Formanek and Martelli, 2020), of tetrahedral structures and of ring-and-chain-like assemblies (Liu et al., 2017). These configurations form densely connected spherical cores of approximately 140 water molecules, surrounded by fuzzy zones of ~1800 loosely connected molecules (Liu et al., 2017). Strong hydrogen bonds create multibranched polymers of about 150 molecules per chain (Naserifar et al., 2019), while density fluctuations form empty spaces resembling spherical or fractal-like voids (Ansari et al., 2018). Other WMA descriptions include a giant cluster percolating the system (dos Santos et al., 2002) and a linear, chain-like structure dominating the tree-like arrangement of the largest cluster (Jedlovszky et al., 2007).

The two-liquids scenario argues that liquid water comprises two competing molecular structures: low-density water (LDW) and high-density water (HDW) (

Table 1). Although frequently observed under extreme conditions, these structures are also found under ambient conditions (Cheng et al., 2019). LDW features ordered gaps between molecular shells (de Oca et al., 2019), while HDW is associated with high-entropy, unstructured states. LDW consists of fused dodecahedra acting as templates for tetrahedral fluctuations, while HDW forms chain-like structures (Camisasca et al., 2019). LDW patches exhibit greater tetrahedrality and connectivity than HDW patches (Ansari et al., 2018; Faccio et al., 2022).

We describe how LDW and HDW may significantly influence biological processes by creating localized environments with specific physical and chemical properties. LDW regions, characterized by ordered hydrogen bonding networks, lower density and reduced entropy, may stabilize structural integrity near hydrophobic interfaces. Conversely, HDW regions, with higher density and entropy and weaker hydrogen bonds, may facilitate conformational transitions, enhance molecular mobility and disrupt ordered structures. This interplay likely impacts processes such as protein folding, enzyme catalysis and DNA and RNA dynamics. Their physical dimensions make WMA compatible with interacting with biological processes and capable of influencing the behaviour of biological macromolecules. Water molecules (~2 Å) form LDW and HDW patches ranging from 0.3–2 nm (Ansari et al., 2018). Near ambient conditions, LDW has a density of 0.78 g/cm³, while HDW reaches 1.08 g/cm³ (Nomura et al., 2017). Although noncovalent bonds in liquid water at room temperature last under 200 femtoseconds (Lodish et al., 2000; Bakó et al., 2013; Naserifar et al., 2019), LDW persists for nearly half a second at 160 K (Lin et al., 2018). Despite their brief lifetimes (Camisasca et al., 2019), LDW and HDW create localized density changes that may affect environmental dynamics and drive macroscopic chemical and biophysical processes (Fanetti et al., 2014; Skarmoutsos and Samios, 2016; Faccio et al., 2022). Also, we argue that percolation theory may play a pivotal role in influencing biochemical processes driven by WMA. In the context of water percolation, LDW may contribute to long-range connectivity within hydration layers, while HDW may provide localized flexibility.

This study explores the influence of WMA on biological phenomena by integrating experimental observations with theoretical insights. By focusing on key processes such as protein folding, enzyme catalysis and membrane dynamics, we aim to establish a framework that underscores water’s active role in shaping the behavior of biological macromolecules. Examining the formation, dynamics and interplay of LDW and HDW, the study provides detailed analyses of their impacts, supported by molecular dynamics simulations and theoretical models.

Theoretical Effects of Water Micro Assemblies on Biological Phenomena

The concept of water micro assemblies (WMA), as discussed in the previous chapter, provides a compelling theoretical framework for understanding physical and dynamic processes (Laage et al., 2017). Below are some potential applications and behaviors explained by WMA:

- 1)

Protein folding and stability. The dynamic interplay between HDW and LDW regions may influence protein folding pathways. Localized density variations may create microenvironments that stabilize or destabilize intermediate folding states.

- 2)

Enzyme catalysis. WMA may modulate catalytic efficiency by restructuring local density and hydrogen-bonding networks near enzyme active sites, enhancing reaction kinetics.

- 3)

Membrane dynamics. Water micro assemblies may impact the stability and interactions of lipid bilayers, offering insights into phenomena such as lipid rafts and transient membrane pore formation.

1) Biological folding and protein stability. Proteins rely on their interactions with water to achieve and maintain their functional structures (Sen and Voorheis, 2014; Schiebel et al., 2018). The interplay of various forces during folding, such as hydrophobic interactions, hydrogen bonding, electrostatic interactions, van der Waals forces and steric constraints highlights the central role of water in these processes (Bellissent-Funel et al., 2016; Phan-Xuan et al., 2020).

Hydrophobic interactions are a key driving force in macromolecular folding, as nonpolar residues cluster internally to avoid water (Fogarty and Laage, 2014; Ye et al., 2024). LDW regions, with their reduced density and structured hydrogen bonding network, may facilitate this process by forming ordered exclusion zones around hydrophobic groups, stabilizing the burial of nonpolar residues. Meanwhile, HDW regions, less structured and more dynamic, may support the transient exposure of hydrophobic residues during early folding stages. Hydrogen bonding is another critical force which stabilizes secondary structures such as α-helices and β-sheets. HDW, due to its higher entropy and looser hydrogen bonds, may disrupt weaker hydrogen bonds in unfolding scenarios, whereas LDW may enhance hydrogen bond stability during folding.

Electrostatic interactions, such as salt bridges and charged residue pairings, are crucial for directing protein folding pathways and stabilizing the final folded structure. The local density variations between LDW and HDW may influence the dielectric constant of water, modulating electrostatic interaction strength. LDW, by reducing shielding effects, may enhance charge-charge attractions in localized regions, promoting stability. Van der Waals forces, though weaker and distance-dependent, are crucial for stabilizing tightly packed molecular cores (Li et al., 2018). The structured nature of LDW may enhance these forces by increasing the local organization of interacting molecules within protein interiors. Steric constraints further limit the conformational space accessible to macromolecules, as backbone torsions and side-chain interactions impose structural restrictions. LDW’s ordered environment may help resolve steric clashes, guiding molecules toward favorable conformations, while HDW may provide flexibility for conformational sampling in partially unfolded states.

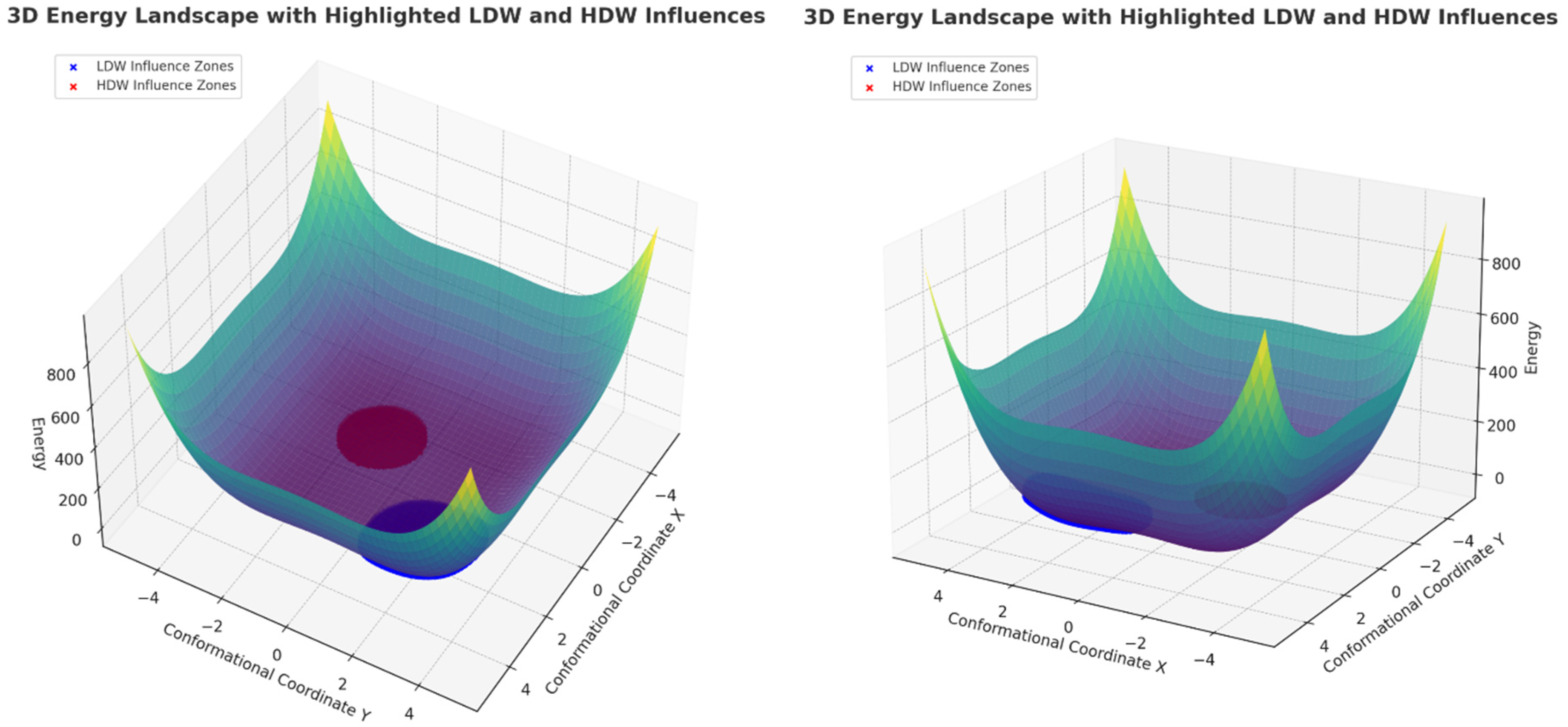

The involvement of WMA in biological folding becomes plausible when considering their energy, timescale and spatial dimensions. The energy scales of folding forces align with the contributions of LDW and HDW transitions (

Table 2), suggesting that WMA may significantly influence folding energetics. The interplay between LDW and HDW may fine-tune the folding energy landscape, balancing stability and flexibility across the conformational space to optimize transitions (

Figure 1). The timescales of WMA also align well with the dynamic requirements of folding processes. Protein folding occurs over milliseconds to seconds for small, single-domain proteins, while LDW and HDW regions exhibit lifetimes ranging from ~200 femtoseconds to 0.5 seconds. This temporal overlap allows micro assemblies to influence both the rapid early stages of folding and the slower stabilization of intermediate or final structures. Spatially, the sizes of micro assemblies, ranging from ~0.3 to 2 nm, are sufficient to interact with folding nuclei (typically ~5 to 10 Å) and influence tertiary and quaternary structural organization.

Experimental and theoretical studies provide evidence for the role of WMA in biological folding and stability. Hydration dynamics reveal how LDW and HDW influence solvation shell behavior (Camisasca et al., 2023). These studies highlight the ability of LDW to form structured, ice-like networks around biomolecules, stabilizing their conformations, while HDW introduces dynamism required for conformational transitions. Evidence from folding pathways, particularly in cold denaturation studies, further supports the relevance of structured water (Taricska et al., 2019). Cold denaturation, where proteins unfold at low temperatures, has been linked to the stabilization of unfolded states by structured hydration layers, consistent with the properties of LDW-HDW transitions (Espinosa et al., 2019)

In sum, WMA may represent a feasible and energetically relevant mechanism for modulating biological folding and stability. Their ability to dynamically adjust local density, hydrogen bonding and dielectric properties makes them a critical, yet underexplored, factor in biophysical processes. LDW stabilizes hydrophobic interactions and secondary structures, while HDW enables dynamic transitions and flexibility. These complementary roles, supported by energy and timescale compatibility, suggest that WMA are integral to the folding process and its regulation.

2) Enzyme catalysis. Enzymatic reactions are governed by various physical forces, all of which align with the unique properties of WMA (Adamczyk et al., 2014; Fogarty and Laage, 2014. Zsidó and Hetényi, 2021). Electrostatic effects are critical in enzyme catalysis, as charged residues and substrates interact to stabilize the transition state and orient substrates within the active site. LDW, with its lower dielectric constant, may enhance these interactions by reducing charge screening, thereby increasing the strength of electrostatic interactions. HDW, due to its flexible hydrogen bonding and higher local entropy, may assist in charge redistribution during catalytic transitions, helping enzymes overcome energy barriers associated with electron transfer or polarization. This dual role enables WMA to modulate the precise electrostatic environment required for catalysis.

Hydrophobic interactions contribute to substrate stabilization by forming nonpolar pockets within enzyme active sites (Kurkal et al., 2005). These hydrophobic pockets exclude bulk water, providing a favorable microenvironment for substrate binding. LDW regions may amplify this effect by creating structured exclusion zones around nonpolar residues, reinforcing the hydrophobic pocket’s integrity. On the other hand, HDW, with its dynamic nature and reduced local density, may transiently disrupt these zones, allowing substrate access to the active site. This balance may ensure that the enzyme maintains a stable yet flexible environment, optimizing both substrate accommodation and turnover. Hydrogen bonding is another cornerstone of enzyme catalysis, stabilizing intermediates and transition states while maintaining precise catalytic geometry. LDW regions, with their stable and extended hydrogen bonding networks, may strengthen these interactions, particularly with polar substrates or intermediates. Conversely, HDW, characterized by dynamic and flexible hydrogen bonding, may facilitate transitions between intermediates and supports efficient product release.

Van der Waals forces play a significant role in substrate alignment and transient state stabilization within enzyme active sites. LDW regions, with their structured local environments, may enhance molecular alignment and optimize these weak interactions. HDW, on the other hand, may introduce the required dynamics to ensure that transient interactions remain flexible, allowing enzymes to adapt their active site to different catalytic steps. Dynamic solvation effects, wherein fluctuations in the solvent modulate energy barriers and facilitate substrate-product exchange, are intrinsically linked to LDW-HDW transitions. These transitions may enable WMA to fine-tune solvation dynamics at each step of the catalytic cycle. LDW regions stabilize specific steps, such as substrate binding or transition state stabilization, while HDW regions introduce dynamic flexibility to promote intermediate transitions and product release. This adaptability may be crucial for the efficiency of enzymatic reactions.

The alignment of WMA energetics with enzymatic processes further supports their potential to influence enzyme catalysis (

Table 3). The timescales of enzymatic processes, which typically range from microseconds to milliseconds, align well with the lifetimes of LDW and HDW regions, which span from 200 femtoseconds to 0.5 seconds. For instance, LDW regions may stabilize critical transition states over microsecond timescales, while HDW regions provide the rapid flexibility needed for intermediate transitions on sub-nanosecond timescales. Spatially, enzyme active sites are typically 1–10 nanometers in size, a scale well-suited for interactions with micro assemblies, which range from 0.3 to 2 nanometers. This spatial compatibility may allow LDW and HDW regions to directly influence active site dynamics, stabilizing critical regions and facilitating the movement of substrates and products. LDW may form around hydrophobic residues in the active site, enhancing substrate stability, while HDW may transiently occupy solvent-accessible areas.

Experimental and theoretical evidence supports the role of WMA in enzyme catalysis. Structured water layers, as observed through solvent isotope effects and hydration studies, correlate with enhanced catalytic rates, aligning with the behavior of LDW (Kurkal-Siebert et at., 2006). Cryo-EM and X-ray crystallography further reinforce this perspective by revealing ordered water clusters near enzyme active sites (Brogan et al., 2014). These clusters, consistent with LDW properties, may play a crucial role in stabilizing catalytic residues. Theoretical studies add depth to this understanding. Molecular dynamics simulations demonstrate that water clusters near active sites exhibit high sensitivity to changes in hydrogen bonding, mirroring the dynamic interplay between LDW and HDW. These transitions highlight the adaptability of WMA in responding to the demands of enzymatic processes, such as stabilizing intermediates or facilitating substrate-product transitions.

The case of chymotrypsin illustrates how WMA may influence enzymatic function. Chymotrypsin, a serine protease, relies on a catalytic triad comprising serine, histidine and aspartate residues for its nucleophilic attack mechanism (Jing et al., 2002). This process is supported by a structured hydration layer, a hallmark of LDW behavior (Kozlova et al., 1999; Eckstein et al., 2002). LDW may stabilize the catalytic triad by strengthening hydrogen bonding, ensuring the alignment and reactivity of these residues. Conversely, HDW may facilitate rapid proton transfer and substrate turnover by modulating local water density, providing the necessary flexibility for catalytic efficiency.

In sum, WMA provide a viable and energetically significant mechanism for influencing enzyme catalysis. Their ability to dynamically adjust hydrogen bonding, hydrophobic interactions, local density and solvation properties makes them possible contributors to catalytic processes.

3) Membrane dynamics. Biological membranes rely heavily on interactions with surrounding water for their structural integrity, fluidity and functionality (Higgins et al., 2006; Wood et al., 2007; Chattopadhyay et al., 2021). The interplay between LDW and HDW regions in the aqueous environment may provide insights into how water influences processes such as lipid organization, protein-membrane interactions and membrane dynamics. Electrostatic interactions are essential for membrane dynamics in stabilizing the polar headgroups of lipids and mediating interactions with charged proteins. LDW regions, with their lower dielectric constant and ordered hydrogen bonding, may enhance membrane electrostatic stabilization by reducing charge screening and strengthening headgroup interactions. HDW regions, on the other hand, may facilitate rapid ion exchange and dynamic interactions between polar lipids and surrounding ions or proteins. This dual behavior ensures that membranes maintain stability while allowing flexibility for dynamic processes.

Hydrophobic interactions are another crucial component of membrane dynamics, driving the self-assembly of lipid bilayers and maintaining their structural integrity (Cheng et al., 2013; Fisette et al., 2016). Nonpolar lipid tails cluster together to minimize water exposure, a process which may be amplified by LDW regions forming structured exclusion zones around hydrophobic regions. Conversely, HDW regions may transiently disrupt these zones, allowing for the lateral mobility of lipids and enabling dynamic rearrangements critical for processes like fusion, fission and protein insertion. Still, hydrogen bonding plays a significant role in maintaining the hydration shells of lipid headgroups and facilitating interactions between the membrane and water-soluble molecules. LDW regions, with their stable hydrogen bonding networks, may provide consistent hydration to polar headgroups, enhancing membrane stability. In contrast, HDW regions, with their dynamic hydrogen bonding, may support processes requiring flexibility, such as lipid flip-flop, membrane deformation or protein-membrane interactions. Van der Waals forces are crucial for lipid packing and membrane stability. LDW regions, by organizing water molecules near the lipid interface, may enhance molecular packing and stabilize membrane structure. Meanwhile, HDW regions may contribute to the dynamic rearrangement of lipids, ensuring the bilayer remains fluid and adaptable under varying conditions.

The transition between different membrane phases, such as the liquid-ordered and liquid-disordered states, provides a case study in microassembly influence. LDW regions may stabilize the liquid-ordered phase by enhancing hydrogen bonding and hydrophobic stabilization, while HDW regions may support the flexibility needed for transitions to the liquid-disordered phase, facilitating processes such as membrane protein activation or lipid raft formation. Dynamic solvation effects, where water molecules in the hydration shell modulate energy barriers and lipid dynamics, may be influenced by LDW-HDW transitions. LDW regions may stabilize bilayer formation by providing structured hydration to lipid headgroups, while HDW regions may allow rapid water exchange and flexibility, supporting membrane-associated processes such as vesicle formation and membrane protein function.

The ability of WMA to influence membrane dynamics is reinforced by their energetic compatibility (

Table 4), suggesting that WMA can meaningfully modulate the forces driving membrane behavior. The timescales of membrane dynamics, ranging from nanoseconds for lipid diffusion to milliseconds for processes like vesicle budding, align well with LDW and HDW lifetimes. This temporal compatibility may allow WMA to influence both rapid lipid rearrangements and slower membrane remodeling events. Spatially, the thickness of the lipid bilayer (~4–6 nm) and the hydration shell (~0.3–1 nm) are well-matched to the size of LDW and HDW regions, ensuring that WMA may interact with membrane components and their surrounding environment.

Experimental evidence supports the involvement of WMA in membrane dynamics. Neutron scattering and cryo-EM studies have revealed ordered water layers around lipid headgroups, consistent with LDW properties (Frölich et al., 2009). Ultrafast spectroscopy and NMR studies further demonstrate the dynamic nature of hydration layers, aligning with the behavior of HDW (Zigmantas et al., 2022; Lorenz-Ochoa et al., 2023). Molecular dynamics simulations provide additional theoretical support, showing structured and dynamic water regions interacting with lipid bilayers and modulating membrane properties.

In sum WMA provides a plausible mechanism for influencing membrane dynamics. Their ability to modulate hydrogen bonding, electrostatic interactions and solvation dynamics positions them as critical contributors to the stability and functionality of biological membranes.

Percolation of Water Microassemblies and Its Role in Biological Systems

Short-lived WMA can form extensive networks that significantly influence average flow properties. The emergence of large-scale connectivity within high-density water assemblies may facilitate percolation through three-dimensional hydrogen-bonded water lattices (Timonin, 2018). Evidence supports the occurrence of percolation in water (Bernabei & Ricci, 2008; Strong et al., 2018). For instance, percolation transitions in hydrogen bond networks have been observed in supercritical water, especially at high molecular densities (Jedlovszky et al., 2007). These transitions follow a universal power law, with percolation occurring when the fractal dimension of the largest cluster approaches 2.53 (Galam & Mauger, 1996; Jedlovszky et al., 2007). A percolating network requires approximately 40% of possible hydrogen bonds to be intact. Simulations reveal that initially disconnected clusters coalesce at critical cut-off values, forming large, space-filling networks with minimal disconnected fragments (Geiger, 1978). Given that 18.01528 grams of water contain 6,02214076×1023 water molecules, the number of percolating molecules is immense, with a system-spanning cluster emerging at a probability of 0.65 in liquid water (Oleinikova et al., 2002).

Percolation significantly influences flow dynamics by creating transient obstacles. Hydrogen bond energies (1–5 kcal/mol) are much lower than those needed to break covalent bonds (~110 kcal/mol) (Lodish et al., 2000). This means that the average molecular kinetic energy at room temperature (~0.6 kcal/mol) is sufficient to disrupt noncovalent bonds, allowing hydrogen bond-induced barriers to influence liquid water flow (Lodish et al., 2000).

Percolation theory offers insights into how WMA influence hydrogen bond networks, phase transitions and transport phenomena. We propose the following theoretical framework:

- 1)

LDW and Percolation Clusters. LDW forms well-ordered hydrogen bond structures, facilitating connectivity and the formation of percolation clusters. Conversely, HDW, with its disrupted hydrogen bonding, acts as a barrier to connectivity.

- 2)

Phase Transition Dynamics. At lower temperatures, LDW regions expand, forming nuclei essential for freezing, while HDW fragments connectivity in supercooled water. In supercritical water, HDW dominates, leading to high diffusivity and low connectivity. As the system transitions back to the liquid phase, LDW re-establishes percolation, restoring cohesion and reducing diffusivity.

- 3)

Diffusion and Transport. Diffusion in liquid water depends on cooperative molecular movement within hydrogen bond networks. LDW forms stable pathways for molecular and ion transport, while HDW introduces transient disruptions. At the percolation threshold, LDW clusters span the system, enabling continuous transport pathways. Proton transport, for instance, relies on rapid hydrogen bond reorganization. LDW maintains stable pathways for proton hopping, whereas HDW slows the process due to structural disorder.

- 4)

Dynamic Percolation and Temperature Effects. Dynamic percolation in water is characterized by the continuous breaking and reforming of hydrogen bonds. At lower temperatures, LDW dominates, forming long-lived percolation clusters, whereas at higher temperatures, HDW fragments the networks, increasing molecular mobility.

- 5)

Constrained Percolation in Confined Environments. In confined environments, such as nanoporous materials or near biomolecular surfaces, water may exhibit constrained percolation. LDW forms ordered layers near hydrophilic interfaces, providing stability, while HDW dominates bulk regions or hydrophobic zones, introducing flexibility and disorder.

In sum, the WMA theoretical framework highlights the fundamental role of percolation in biological systems and provides a basis for further exploration of LDW and HDW’s influence on molecular and macroscopic phenomena. Future integration of percolation models with experimental and computational approaches will help unravel the complexity of these dynamic water networks.

Conclusions

Liquid water exhibits intrinsic chemical inhomogeneity, manifesting as a dynamic three-dimensional network characterized by microscopic density fluctuations and structural variations. Water, far beyond being a passive solvent, plays an active and multifaceted role in driving and modulating biological phenomena. This study explored the concept of WMA, characterized by LDW and HDW regions, as dynamic contributors to various molecular and cellular processes. Through their distinct physical and chemical properties, WMA offer a framework to better understand the behavior of water at the nanoscale and its influence on key biological processes. LDW, defined by structured hydrogen bond networks, lower density and high coherence, may stabilize hydrophobic interactions, hydrogen bonding and molecular order. Conversely, HDW, with its dynamic, higher-density and entropy-driven properties, may facilitate flexibility, conformational sampling and rapid transitions. These dual roles enable WMA to act as adaptable mediators across a wide range of biological phenomena, optimizing stability and functionality under varying conditions. Across protein folding, enzyme catalysis and membrane dynamics, the energy contributions, timescales and spatial scales of WMA align with the forces and dynamics involved, underscoring the critical role of LDW and HDW transitions in modulating dynamical interactions in the cellular milieu.

While the concept of WMA is still emerging, their influence may extend beyond understanding fundamental biological processes. WMA may have significant implications across experimental, technological and pathological contexts, spanning multiple disciplines, including molecular biology, fluid dynamics and materials science.

In microfluidics and nanofluidics, understanding the dynamic behavior of these micro assemblies can lead to enhanced control of water within confined geometries, a critical factor for designing lab-on-chip devices that require precise manipulation of fluid dynamics at the microscale. The ability to induce or manipulate LDW and HDW regions artificially opens the door to creating targeted micro-vortices or density variations. Such capabilities may pave the way for novel sensor technologies where the localized structuring of water affects sensitivity and detection thresholds or for advanced turbulence control mechanisms in engineering systems. Also, artificial catalysts may benefit from mimicking LDW-HDW transitions, improving efficiency by incorporating water-like dynamics into synthetic systems.

In biomedical and pharmaceutical contexts, understanding WMA can inform the design of drugs and therapeutics that leverage hydration dynamics. Mimicking the properties of WMA may inspire the development of biomimetic systems such as responsive hydrogels or biomimetic membranes with tailored properties for drug delivery. In drug design, targeting water dynamics within active sites may optimize the specificity and efficacy of ligand binding and enzyme inhibitors, enhancing drug efficacy. Our study also highlights the importance of exploring the role of WMA in complex and confined environments, such as within cells or in biomolecular assemblies. In these scenarios, water’s behavior deviates significantly from that of bulk water, with hydration layers and confined spaces amplifying the influence of micro assemblies. Understanding these effects may reveal new principles underlying cellular organization, molecular recognition and signal transduction.

Additionally, understanding water’s role in pathological conditions, such as protein misfolding diseases, cancer or neurodegeneration, may open new avenues for therapeutic intervention. Abnormal interactions between LDW and HDW may contribute to the pathological protein aggregation observed in lipid storage disorders and neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s or Parkinson’s disease (Polychronidou et al., 2020; Padilla-Godínez et al., 2021). Similarly, variations in water density may explain some of the unique physical and biochemical properties of tumor microenvironments (He et al., 2022). In cancer, localized turbulence or non-uniform water structuring in the interstitial fluid may influence nutrient transport, cellular communication and drug delivery effectiveness.

Despite significant advances, challenges persist in fully understanding the role of WMA in biological phenomena. The transient and highly dynamic nature of LDW and HDW makes their phase spaces difficult to explore, leading to the upsetting concept of “water’s no-man’s land” (Lin et al., 2018). Despite liquid water can be tackled in terms of an evolving, fluctuating and branched polymer (Naserifar et al., 2019), a full understanding of its dynamical and structural properties is still lacking (Fanetti et al., 2014) due to technical difficulties in gaining experimental information on ultrafast interplay (Tamtögl et al., 2020). The heterogeneity of water is usually approached through simulation of molecular dynamics, such as, e.g., conventional QM/MM scheme and ONIOM-XS methods (Thaomola et al., 2017), second-order Møller–Plesset perturbation theory (Liu et al. 2017), quantum Monte Carlo, non-canonical coupled cluster theory (Al-Hamdani and Tkatchenko, 2019), modified Louvain algorithm of graph community (Gao et al., 2021), topological local (clustering coefficient, path length and degree distribution) and global (spectral analysis) properties (dos Santos et al., 2002; Carreras et al., 2008; Steinberg et al., 2019), persistent homology methods (Wu 2020). These methods operate at different temporal and spatial resolutions, necessitating further integration for a more comprehensive understanding. Weak, non-covalent interactions have been experimentally studied just in small molecular complexes, falling short of the macroscopic structural properties that are typical of complex soft materials such as, e.g., supramolecular aggregates (Al-Hamdani and Tkatchenko, 2019). To make things more complicated, totally different networks topologies and physical interpretations have been provided, depending on how rings have been counted (Das et al., 2019; Formanek and Martelli, 2020).

It remains uncertain whether liquid water exhibits randomness or long-range interactions. Dos Santos et al. (2002) proposed that the water network at room temperature resembles a Poisson distribution, indicative of randomness. However, other studies present evidence of medium- to long-range order (Faccio et al., 2022). Tamtögl et al. (2020) observed correlated motion at the surface of a topological insulator, contrasting with Brownian motion, while Ansari et al. (2018) and Gao et al. (2021) reported collective translational fluctuations in hydrogen-bonded water clusters. Percolation models face challenges, such as the inability to determine the percolation threshold based solely on cluster size distribution (Jedlovszky et al., 2007). Moreover, environmental factors, including temperature, pressure and solute concentration may influence the balance between LDW and HDW. For example, lower temperatures correspond to stronger hydrogen bond interactions. Upon melting, increases in temperature result in a rapid decrease in the average number of assemblies (Gao et al., 2021) and a broader ring size distribution (Bakó et al., 2013; Naserifar et al., 2019). Consequently, microscopic assemblies in water become difficult to distinguish beyond the isochore endpoint of 292 K (Nomura et al., 2017).

Future research should focus on developing more refined experimental and computational methods to study WMA and their interactions with biomolecules. Experimentally, combining time-resolved methods with spatially resolved imaging techniques may bridge the gap between molecular dynamics and observable biological outcomes.

In conclusion, WMA may represent a transformative perspective on the active role of water in biological phenomena. By bridging the gap between molecular-scale dynamics and macroscopic behavior, WMA may provide a unifying framework for understanding how water shapes biomolecular processes. LDW and HDW, through their complementary properties, may influence stability, flexibility and functionality across diverse biological systems. As research in this field advances, the potential applications in health, technology and materials science are vast, underscoring the importance of continued exploration into the dynamic world of WMA.

Author Contributions

The Author performed: study concept and design, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting of the manuscript, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content, statistical analysis, obtained funding, administrative, technical and material support, study supervision.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This research does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by the Author.

Consent for publication

The Author transfers all copyright ownership, in the event the work is published. The undersigned author warrants that the article is original, does not infringe on any copyright or other proprietary right of any third part, is not under consideration by another journal and has not been previously published.

Availability of data and materials

All data and materials generated or analyzed during this study are included in the manuscript. The Author had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Competing interests

The Author does not have any known or potential conflict of interest including any financial, personal or other relationships with other people or organizations within three years of beginning the submitted work that may inappropriately influence, or be perceived to influence, their work.

Declaration of generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing process

During the preparation of this work, the author used ChatGPT to assist with data analysis and manuscript drafting. After using this tool, the author reviewed and edited the content as needed and takes full responsibility for the content of the publication.

References

- Adamczyk, K.; Simpson, N.; Greetham, G.M.; Gumiero, A.; Walsh, M.A.; Towrie, M.; Parker, A.W.; Hunt, N.T. Ultrafast infrared spectroscopy reveals water-mediated coherent dynamics in an enzyme active site. Chem. Sci. 2014, 6, 505–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ansari, N.; Dandekar, R.; Caravati, S.; Sosso, G.; Hassanali, A. High and low density patches in simulated liquid water. J. Chem. Phys. 2018, 149, 204507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barber, R. W. and D. R. Emerson. “The Influence of Knudsen Number on the Hydrodynamic Development Length Within Parallel Plate Micro-channels.” WIT Transactions on Engineering Sciences 36 (2002): 191–202.

- Bellissent-Funel, M.-C.; Hassanali, A.; Havenith, M.; Henchman, R.; Pohl, P.; Sterpone, F.; van der Spoel, D.; Xu, Y.; E Garcia, A. Water Determines the Structure and Dynamics of Proteins. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 7673–7697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernabei, M.; A Ricci, M. Percolation and clustering in supercritical aqueous fluids. J. Physics: Condens. Matter 2008, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brogan, A.P.S.; Sharma, K.P.; Perriman, A.W.; Mann, S. Enzyme activity in liquid lipase melts as a step towards solvent-free biology at 150 °C. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 5058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camisasca, G.; Schlesinger, D.; Zhovtobriukh, I.; Pitsevich, G.; Pettersson, L.G.M. A proposal for the structure of high- and low-density fluctuations in liquid water. J. Chem. Phys. 2019, 151, 034508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camisasca, G.; Tenuzzo, L.; Gallo, P. Protein hydration water: Focus on low density and high density local structures upon cooling. J. Mol. Liq. 2022, 370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chattopadhyay, M.; Krok, E.; Orlikowska, H.; Schwille, P.; Franquelim, H.G.; Piatkowski, L. Hydration Layer of Only a Few Molecules Controls Lipid Mobility in Biomimetic Membranes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 14551–14562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.-Y.; Varkey, J.; Ambroso, M.R.; Langen, R.; Han, S. Hydration dynamics as an intrinsic ruler for refining protein structure at lipid membrane interfaces. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2013, 110, 16838–16843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S., X. Wang, Z. Zhang and S. Li. “Ultra-High-Density Local Structure in Liquid Water.” Chinese Physics B 28, no. 11 (2019): 116104.

- Dargaville, B.L.; Hutmacher, D.W. Water as the often neglected medium at the interface between materials and biology. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, K.; Roy, B.; Satpathi, S.; Hazra, P. Impact of Topology on the Characteristics of Water inside Cubic Lyotropic Liquid Crystalline Systems. J. Phys. Chem. B 2019, 123, 4118–4128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Oca, J.M.M.; Accordino, S.R.; Verde, A.R.; Alarcón, L.M.; Appignanesi, G.A. Structural features of high-local-density water molecules: Insights from structure indicators based on the translational order between the first two molecular shells. Phys. Rev. E 2019, 99, 062601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- dos Santos, V.M.L.; Moreira, F.B.; Longo, R.L. Topology of the hydrogen bond networks in liquid water at room and supercritical conditions: a small-world structure. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2004, 390, 157–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckstein, M.; Sesing, M.; Kragl, U.; Adlercreutz, P. At low water activity α-chymotrypsin is more active in an ionic liquid than in non-ionic organic solvents. Biotechnol. Lett. 2002, 24, 867–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinosa, Y.R.; Caffarena, E.R.; Grigera, J.R. The role of hydrophobicity in the cold denaturation of proteins under high pressure: A study on apomyoglobin. J. Chem. Phys. 2019, 150, 075102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faccio, C.; Benzi, M.; Zanetti-Polzi, L.; Daidone, I. Low- and high-density forms of liquid water revealed by a new medium-range order descriptor. J. Mol. Liq. 2022, 355, 118922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanetti, S.; Lapini, A.; Pagliai, M.; Citroni, M.; Di Donato, M.; Scandolo, S.; Righini, R.; Bini, R. Structure and Dynamics of Low-Density and High-Density Liquid Water at High Pressure. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2013, 5, 235–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisette, O.; Päslack, C.; Barnes, R.; Isas, J.M.; Langen, R.; Heyden, M.; Han, S.; Schäfer, L.V. Hydration Dynamics of a Peripheral Membrane Protein. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 11526–11535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fogarty, A.C.; Laage, D. Water Dynamics in Protein Hydration Shells: The Molecular Origins of the Dynamical Perturbation. J. Phys. Chem. B 2014, 118, 7715–7729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Formanek, M.; Martelli, F. Probing the network topology in network-forming materials: The case of water. AIP Adv. 2020, 10, 055205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frölich, A.; Gabel, F.; Jasnin, M.; Lehnert, U.; Oesterhelt, D.; Stadler, A.M.; Tehei, M.; Weik, M.; Wood, K.; Zaccai, G. From shell to cell: neutron scattering studies of biological water dynamics and coupling to activity. Faraday Discuss. 2008, 141, 117–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galam, S.; Mauger, A. Universal formulas for percolation thresholds. Phys. Rev. E 1996, 53, 2177–2181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Y.; Fang, H.; Ni, K. A hierarchical clustering method of hydrogen bond networks in liquid water undergoing shear flow. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geiger, A.; Stillinger, F.H.; Rahman, A. Aspects of the percolation process for hydrogen-bond networks in water. J. Chem. Phys. 1979, 70, 4185–4193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Yang, Y.; Han, Y.; Cao, C.; Zhang, Z.; Li, L.; Xiao, C.; Guo, H.; Wang, L.; Han, L.; et al. Extracellular matrix physical properties govern the diffusion of nanoparticles in tumor microenvironment. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2022, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, M.J.; Polcik, M.; Fukuma, T.; Sader, J.E.; Nakayama, Y.; Jarvis, S.P. Structured Water Layers Adjacent to Biological Membranes. Biophys. J. 2006, 91, 2532–2542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pártay, L.B.; Jedlovszky, P.; Brovchenko, I.; Oleinikova, A. Percolation Transition in Supercritical Water: A Monte Carlo Simulation Study. J. Phys. Chem. B 2007, 111, 7603–7609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, H.; Xu, Y.; Carson, M.; Moore, D.; Macon, K.J.; Volanakis, J.E.; Narayana, S.V. New structural motifs on the chymotrypsin fold and their potential roles in complement factor B. EMBO J. 2000, 19, 164–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.U.; Barstow, B.; Tate, M.W.; Gruner, S.M. Evidence for liquid water during the high-density to low-density amorphous ice transition. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2009, 106, 4596–4600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozlova, N.; Bruskovskaya, I.; Melik-Nubarov, N.; Yaroslavov, A.; Kabanov, V. Catalytic properties and conformation of hydrophobized α-chymotrypsin incorporated into a bilayer lipid membrane. FEBS Lett. 1999, 461, 141–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurkal, V.; Daniel, R.; Finney, J.L.; Tehei, M.; Dunn, R.; Smith, J.C. Enzyme Activity and Flexibility at Very Low Hydration. Biophys. J. 2005, 89, 1282–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bercu, V.; Martinelli, M.; Massa, C.; Pardi, L.; Leporini, D. Signatures of the fast dynamics in glassy polystyrene by multi-frequency, high-field electron paramagnetic resonance of molecular guests. J. Non-Crystalline Solids 2006, 352, 5029–5034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laage, D.; Elsaesser, T.; Hynes, J.T. Water Dynamics in the Hydration Shells of Biomolecules. Chem. Rev. 2017, 117, 10694–10725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arisaka, A.; Mogaki, R.; Okuro, K.; Aida, T. Caged Molecular Glues as Photoactivatable Tags for Nuclear Translocation of Guests in Living Cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 2687–2692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.; Smith, J.S.; Sinogeikin, S.V.; Shen, G. Experimental evidence of low-density liquid water upon rapid decompression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2018, 115, 2010–2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; He, X.; Zhang, J.Z.H. Structure of liquid water – a dynamical mixture of tetrahedral and ‘ring-and-chain’ like structures. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2017, 19, 11931–11936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lodish, H., A. Berk and S. L. Zipursky. Molecular Cell Biology. 4th ed. New York: W. H. Freeman, 2000.

- Lorenz-Ochoa, K.A.; Baiz, C.R. Ultrafast Spectroscopy Reveals Slow Water Dynamics in Biocondensates. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2023, 145, 27800–27809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naserifar, S.; Goddard, W.A. Liquid water is a dynamic polydisperse branched polymer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2019, 116, 1998–2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oleinikova, A.; Brovchenko, I.; Geiger, A.; Guillot, B. Percolation of water in aqueous solution and liquid–liquid immiscibility. J. Chem. Phys. 2002, 117, 3296–3304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padilla-Godínez, F.J.; Ramos-Acevedo, R.; Martínez-Becerril, H.A.; Bernal-Conde, L.D.; Garrido-Figueroa, J.F.; Hiriart, M.; Hernández-López, A.; Argüero-Sánchez, R.; Callea, F.; Guerra-Crespo, M. Protein Misfolding and Aggregation: The Relatedness between Parkinson’s Disease and Hepatic Endoplasmic Reticulum Storage Disorders. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 12467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phan-Xuan, T.; Bogdanova, E.; Fureby, A.M.; Fransson, J.; Terry, A.E.; Kocherbitov, V. Hydration-Induced Structural Changes in the Solid State of Protein: A SAXS/WAXS Study on Lysozyme. Mol. Pharm. 2020, 17, 3246–3258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polychronidou, Eleftheria, Antigoni Avramouli, and Panayiotis Vlamos. “Alzheimer’s Disease: The Role of Mutations in Protein Folding.” Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology 1195 (2020): 227–236. [CrossRef]

- Schiebel, J.; Gaspari, R.; Wulsdorf, T.; Ngo, K.; Sohn, C.; Schrader, T.E.; Cavalli, A.; Ostermann, A.; Heine, A.; Klebe, G. Intriguing role of water in protein-ligand binding studied by neutron crystallography on trypsin complexes. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sen, S.; Voorheis, H.P. Protein folding: Understanding the role of water and the low Reynolds number environment as the peptide chain emerges from the ribosome and folds. J. Theor. Biol. 2014, 363, 169–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shiotari, A.; Sugimoto, Y. Ultrahigh-resolution imaging of water networks by atomic force microscopy. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 14313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strong, S.E.; Shi, L.; Skinner, J.L. Percolation in supercritical water: Do the Widom and percolation lines coincide? J. Chem. Phys. 2018, 149, 084504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamtögl, A.; Sacchi, M.; Avidor, N.; Calvo-Almazán, I.; Townsend, P.S.M.; Bremholm, M.; Hofmann, P.; Ellis, J.; Allison, W. Nanoscopic diffusion of water on a topological insulator. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- aricska, Nóra, Mónika Bokor, Dóra K. Menyhárd, Kálmán Tompa, and András Perczel. “Hydration Shell Differentiates Folded and Disordered States of a Trp-Cage Miniprotein, Allowing Characterization of Structural Heterogeneity by Wide-Line NMR Measurements.” Scientific Reports 9, Article 2947 (February 27, 2019): 1–12.

- Timonin, P.N. Statistical mechanics of high-density bond percolation. Phys. Rev. E 2018, 97, 052119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, K.; Plazanet, M.; Gabel, F.; Kessler, B.; Oesterhelt, D.; Tobias, D.J.; Zaccai, G.; Weik, M. Coupling of protein and hydration-water dynamics in biological membranes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2007, 104, 18049–18054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H. “The Topological Features of a Fully Developed Turbulent Wake Flow.” APS Division of Fluid Dynamics (Fall), abstract id.S09.007, 2020.

- Ye, Y.; Chen, X.; Huang, J.; Zheng, L.; Tang, Q.; Long, L.; Yamada, T.; Tyagi, M.; Sakai, V.G.; O’neill, H.; et al. Dynamic entity formed by protein and its hydration water. Phys. Rev. Res. 2024, 6, 033316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zigmantas, D.; Polívka, T.; Persson, P.; Sundström, V. Ultrafast laser spectroscopy uncovers mechanisms of light energy conversion in photosynthesis and sustainable energy materials. Chem. Phys. Rev. 2022, 3, 041303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zsidó, B.Z.; Hetényi, C. The role of water in ligand binding. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2020, 67, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).