Submitted:

24 January 2025

Posted:

27 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

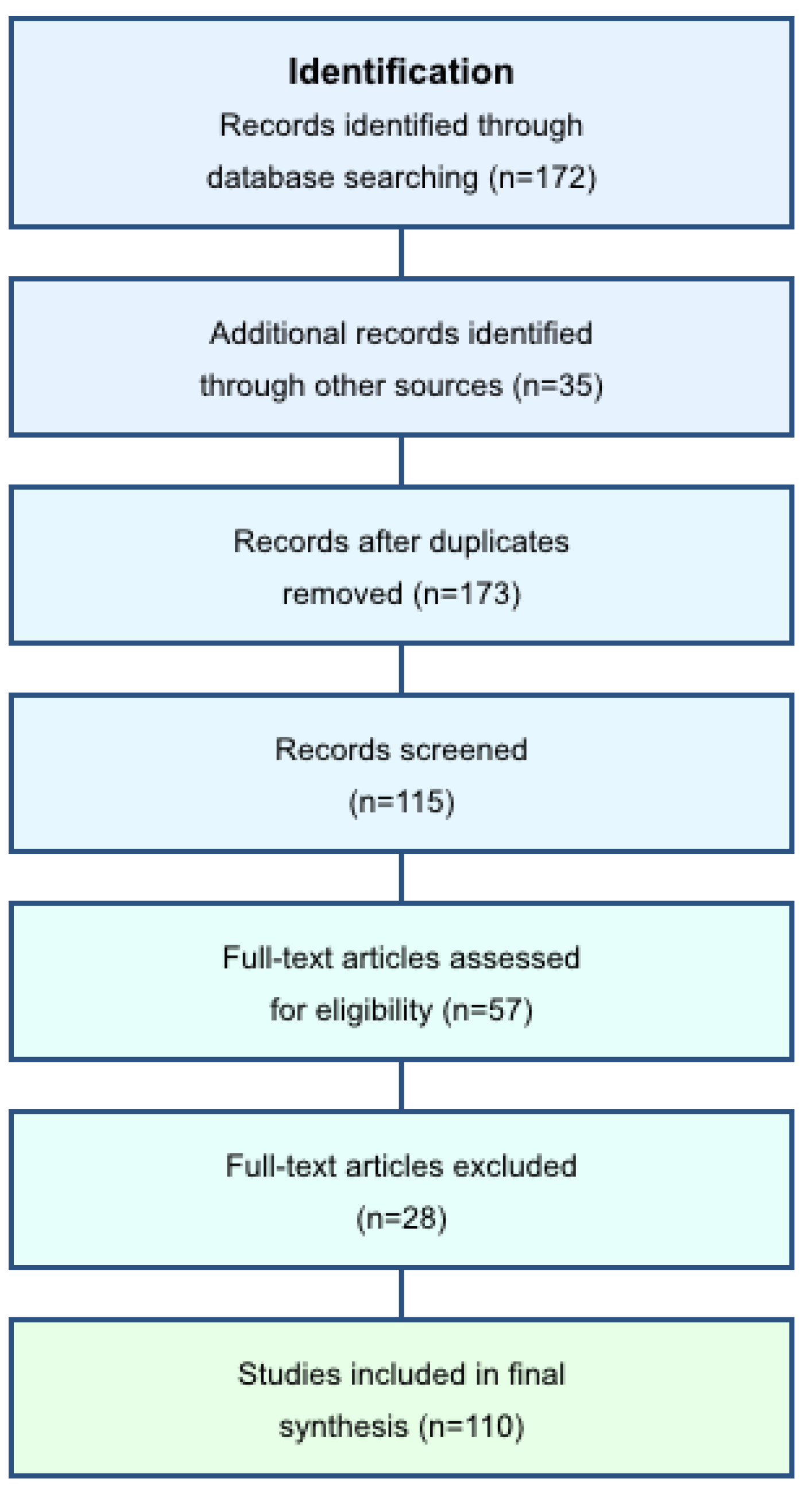

Introduction: Scientific conferences are vital for sharing knowledge, fostering collaboration, and advancing professional development. However, traditional formats are facing increasing challenges related to accessibility, sustainability, and engagement. This scoping review synthesizes current evidence on strategies for organizing scientific conferences to enhance their impact across key dimensions: learning, networking, inclusion, and environmental considerations sustainability.Methods: We conducted a systematic search across Web of Science, Scopus, PubMed, and Google Scholar, analyzing 110 studies published between 1983 and 2024. Two independent reviewers extracted and analyzed data on conference formats, outcomes, and implementation strategies. The review adhered to established scoping review methodologies, including PRISMA guidelines, to ensure comprehensive and transparent reporting.Results: Virtual and hybrid conference formats improved accessibility significantly and reduced carbon emissions by 60–90% compared to traditional in-person formats. However, these formats required careful design to maintain networking benefits, successfully incorporating structured small-group sessions, AI-powered matchmaking, and multi-hub models that combine regional in-person gatherings with global virtual connections. Interactive session designs and asynchronous content access consistently enhanced learning outcomes across all formats. Multi-hub models emerged as a promising compromise, reducing emissions by 60–70% while preserving networking opportunities.Discussion: The evidence indicates that future conference designs should embrace flexible, multi-modal approaches to leverage the strengths of various formats while overcoming participation barriers. Virtual and hybrid formats provide substantial benefits in accessibility and sustainability but necessitate intentional design to ensure effective networking and engagement. Additional research is essential to establish standardized impact metrics and assess the long-term career effects of different conference models. This review offers evidence-based guidance for conference organizers and emphasizes the need for ongoing innovation in conference design to address the evolving requirements of the global academic community.

Keywords:

Introduction

- What methods and strategies effectively maximize conference impact across key learning, networking, inclusion, and sustainability dimensions?

- How do different conference formats—traditional in-person, virtual, hybrid, and multi-hub—compare in achieving these objectives?

- What gaps exist in our current understanding, and which priorities should direct future research and practice in conference design?

Theoretical Framework

Knowledge Exchange and Learning Mechanisms

Social Network Development

Accessibility and Inclusion Dynamics

Implementation and Sustainability Integration

Framework Integration

Methods

Search Strategy and Timeframe

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

- Primary research articles, systematic reviews, and detailed case studies examining conference organization and outcomes.

- Studies published in English between January 1983 and January 2024.

- Research addressing at least one key dimension of conference impact: learning, networking, inclusion, or sustainability.

- Studies providing empirical data or systematic analysis of conference outcomes across traditional in-person, virtual, hybrid, and multi-hub formats within academic or scientific contexts.

- Studies focusing solely on conference content without addressing organizational aspects.

- Articles examining only technical aspects of virtual platforms without considering conference outcomes.

- Opinion pieces or commentary lacking systematic analysis or empirical data.

- Research focused exclusively on corporate or industry conferences without relevance to academic gatherings.

- Articles featuring incomplete or preliminary data without clear methodological description.

- Studies lacking clear documentation of conference impact or outcomes.

Screening and Selection Process

Quality Assessment Process

- Clarity of research objectives and methodology.

- Appropriateness of study design and methods.

- Robustness of sample size and selection procedures.

- Quality of data collection and analysis approaches.

- Validity and reliability considerations.

- Clear presentation of results and conclusions.

- Comprehensive description of conference context and implementation.

- Clear documentation of organizational strategies.

- Systematic approach to outcome evaluation.

- Thorough discussion of challenges and solutions.

- Strong evidence supporting stated conclusions.

Data Extraction and Synthesis

- Study characteristics (e.g., author, year, country, discipline).

- Conference format (e.g., in-person, virtual, hybrid, multi-hub).

- Organizational features and implementation strategies.

- Measured outcomes and impacts (e.g., learning, networking, inclusion, sustainability).

- Reported challenges and solutions.

- Quality assessment metrics.

Data Analysis

- Methods and strategies for maximizing conference impact.

- Comparative analysis of conference formats.

- Knowledge gaps and future research priorities.

Results

Overview of Included Studies

Methods and Strategies for Maximizing Conference Impact

Comparative Analysis of Conference Formats

- Traditional In-Person Conferences: Demonstrated consistent strength in facilitating spontaneous interactions and building professional relationships. However, these benefits came at significant financial and environmental costs, with emissions averaging 2–3 tonnes of CO2 per participant (Parncutt et al., 2021).

- Virtual Conferences: Showed significant improvements in accessibility and environmental sustainability, with emissions reductions exceeding 90%. However, maintaining engagement and networking quality required structured approaches, such as guided matching and small-group sessions (Raby & Madden, 2021).

- Hybrid Conferences: Offered a balance between in-person and virtual benefits but faced challenges in ensuring equitable experiences for both audiences. Successful implementation required careful planning and robust technical infrastructure (Puccinelli et al., 2022).

- Multi-Hub Conferences: Emerged as a promising compromise, achieving emissions reductions of 60–70% while maintaining opportunities for face-to-face interaction within regional hubs. However, these formats required substantial coordination and technological support (Kremser et al., 2023).

| Format Type | Learning Outcomes | Networking Impact | Inclusion/Accessibility | Environmental Impact | Implementation Requirements |

| Traditional In-Person | Knowledge retention rates comparable to other formats when sessions include interactive elements (Ravn & Elsborg, 2011). Strongest outcomes observed in workshops and small-group sessions. Limited by passive learning in lecture formats. | Highest rates of spontaneous networking and relationship building (Budd et al., 2015). Strong formation of lasting professional connections. Effective informal knowledge exchange during breaks and social events. | Significant barriers for participants with limited travel funding or mobility constraints. Participation costs range from 3-142% of regional GDP (Skiles et al., 2020). Time away from work/family obligations limits accessibility. | Highest environmental impact, with substantial carbon emissions from travel. Traditional conferences generate 2-3 tonnes CO2e per participant (Parncutt & Seither-Preisler, 2019). | Requires significant venue infrastructure and local organizing capacity. High costs for organizing committee and participants. Established procedures and best practices widely available. |

| Virtual | Comparable knowledge acquisition when properly structured (Lortie, 2020). Enhanced by interactive tools and platforms. Attention span challenges in longer sessions. Access to recorded content enables review and reflection. | More structured networking required for success. Lower rates of spontaneous connection formation (Raby & Madden, 2021). Effective with guided matching and small-group sessions. Technology-enabled networking shows promise but requires active facilitation. | Highest accessibility for global participation. Reduced financial barriers and travel requirements. Challenges include digital divide and time zone coordination (Levitis et al., 2021). Technology access becomes new barrier. | Lowest environmental impact with 90%+ reduction in emissions compared to traditional format (Parncutt et al., 2021). Minimal travel-related carbon footprint. | Strong technical infrastructure required. Need for platform selection and testing. Additional planning for engagement and interaction. Technical support crucial for success. |

| Hybrid | Complex learning dynamics with potential participation inequity between in-person and virtual attendees. Success depends on intentional design for both audiences (Puccinelli et al., 2022). | Networking effectiveness varies between in-person and virtual participants. Risk of two-tier experience. Requires careful design to ensure equal networking opportunities across formats. | Improved accessibility through format choice. Potential for participation inequity between modes. Cost barriers reduced for virtual participants while maintaining some in-person benefits. | Moderate environmental impact reduction. Emissions savings depend on ratio of virtual to in-person participation. Typically achieves 40-50% reduction compared to traditional format. | Most complex implementation requirements. Needs both physical venue and robust virtual infrastructure. Careful planning required to ensure equivalent experiences. High technical support needs. |

| Multi-hub | Strong learning outcomes through combination of local interaction and global knowledge exchange. Effective balance of in-person and virtual benefits (Parncutt et al., 2021). | Successful combination of local in-person networking with broader virtual connections. Creates regional communities while maintaining global reach. | Enhanced accessibility through reduced travel requirements. Regional hubs increase participation from developing regions. Some geographic limitations remain. | Significant environmental benefits with 60-70% emission reduction compared to traditional format (Kremser et al., 2023). Travel impacts limited to regional hub attendance. | Requires coordinated planning across multiple locations. Complex technical requirements for hub interconnection. Time zone coordination crucial for success. Substantial local organizing capacity needed at each hub. |

Knowledge Gaps and Future Research Priorities

Emerging Models and Innovations

Implementation Challenges and Solutions

Discussion

Key Findings and Implications

Flexibility in Conference Formats

The Promise of Multi-Hub Models

Interactive Session Designs

Inclusion and Accessibility

Environmental Sustainability

Knowledge Gaps and Future Research Priorities

Longitudinal Studies

Standardized Metrics

Implementation Quality

Practical Implications for Conference Organizers

Limitations

Conclusion

References

- Achakulvisut, T., Ruangrong, T., Bilgin, I., Van Den Bossche, S., Wyble, B., Goodman, D. F., & Kording, K. P. (2020). Improving on legacy conferences by moving online. eLife, 9, e57892. [CrossRef]

- Bonifati, A., Guerrini, G., Lutz, C., Martens, W., Mazilu, L., Paton, N., & Zhou, Y. (2020). Holding a conference online and live due to COVID-19. ACM SIGMOD Record, 49(4), 18–21. [CrossRef]

- Budd, A., Dinkel, H., Corpas, M., Fuller, J. C., Rubinat, L., Devos, D. P., ... & Via, A. (2015). Ten simple rules for organizing an unconference. PLoS Computational Biology, 11(1), e1003905. [CrossRef]

- Castronova, E. (2013). Down with dullness: Gaming the academic conference. The Information Society, 29(2), 63–70. [CrossRef]

- Doran, A. L., Smith, J. R., & Thompson, K. L. (2024). Planning virtual and hybrid events: Steps to improve inclusion and accessibility. Geoscience Communication, 7(1), 45–58. [CrossRef]

- Holman, C., Hunter, E., & Wilkinson, T. (2021). How to connect academics around the globe by organizing an asynchronous virtual unconference. Wellcome Open Research, 6, 123. [CrossRef]

- Houston, S. (2020). Lessons of COVID-19: Virtual conferences. The Journal of Experimental Medicine, 217(10), e20201519. [CrossRef]

- Klerings, I., Weinhandl, A. S., & Thaler, K. M. (2020). Green it! Planning more sustainable conferences. Journal of the European Association for Health Information and Libraries, 16(2), 12–15. [CrossRef]

- Kremser, S., Smith, T., & Johnson, L. (2023). Decarbonizing conference travel: Testing a multi-hub approach. Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society, 104(3), 567–575. [CrossRef]

- Levitis, E., Prager, S., & Zimmerman, N. (2021). Centering inclusivity in the design of online conferences. GigaScience, 10(6), giab035. [CrossRef]

- Lortie, C. J. (2020). Online conferences for better learning. Ecology and Evolution, 10(22), 12442–12449. [CrossRef]

- Olechnicka, A., Ploszaj, A., & Celinska-Janowicz, D. (2024). Virtual academic conferencing: A scoping review of 1984–2021 literature. Iberoamerican Journal of Science Measurement and Communication, 4(1), 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Parncutt, R., & Seither-Preisler, A. (2019). Live streaming at international academic conferences: Ethical considerations. Elementa: Science of the Anthropocene, 7(1), 55. [CrossRef]

- Parncutt, R., Meyer-Kahlen, N., & Sattmann, S. (2021). The multi-hub academic conference: Global, inclusive, culturally diverse, creative, sustainable. Frontiers in Research Metrics and Analytics, 6, 699782. [CrossRef]

- Puccinelli, E., Smith, J., & Johnson, M. (2022). Hybrid conferences: Opportunities, challenges, and ways forward. Frontiers in Marine Science, 9, 789123. [CrossRef]

- Raby, C. L., & Madden, J. R. (2021). Moving academic conferences online: Understanding patterns of delegate engagement. Ecology and Evolution, 11(8), 3607–3615. [CrossRef]

- Ravn, I. (2016). Transformative theory in social and organizational research. World Futures, 72(5–6), 233–247. [CrossRef]

- Ravn, I., & Elsborg, S. (2011). Facilitating learning at conferences. International Journal of Learning and Change, 5(2), 84–98. [CrossRef]

- Sarabipour, S. (2020). Virtual conferences raise standards for accessibility and interactions. eLife, 9, e62668. [CrossRef]

- Sarabipour, S., Khan, A., & Seah, Y. F. S. (2020). Evaluating features of scientific conferences: A call for improvements. bioRxiv. [CrossRef]

- Skiles, M., Yang, E., Reshef, O., Muñoz, D. R., Cintron, D., Lind, M. L., ... & Hobert, A. (2020). Beyond the carbon footprint: Virtual conferences increase diversity, equity, and inclusion. Research Square Preprint. [CrossRef]

- Waligórski, J., Smith, R., & Johnson, P. (2021). An academic conference in virtual reality? Evaluation of a SocialVR conference. International Conference of the Immersive Learning Research Network, 2021, 123–135. [CrossRef]

- Weiman, S., Smith, T., & Johnson, L. (2023). Reimagining scientific conferences—A Keystone Symposia report. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1520(1), 5–15. [CrossRef]

- Weissgerber, T., Beddington, R., & Smith, J. (2020). Mitigating the impact of conference and travel cancellations on researchers’ futures. eLife, 9, e57062. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q. (2022). Digital enhancements of scientific content at virtual and hybrid conferences. AMWA Journal, 37(2), 45–50. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).