Submitted:

26 January 2025

Posted:

26 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

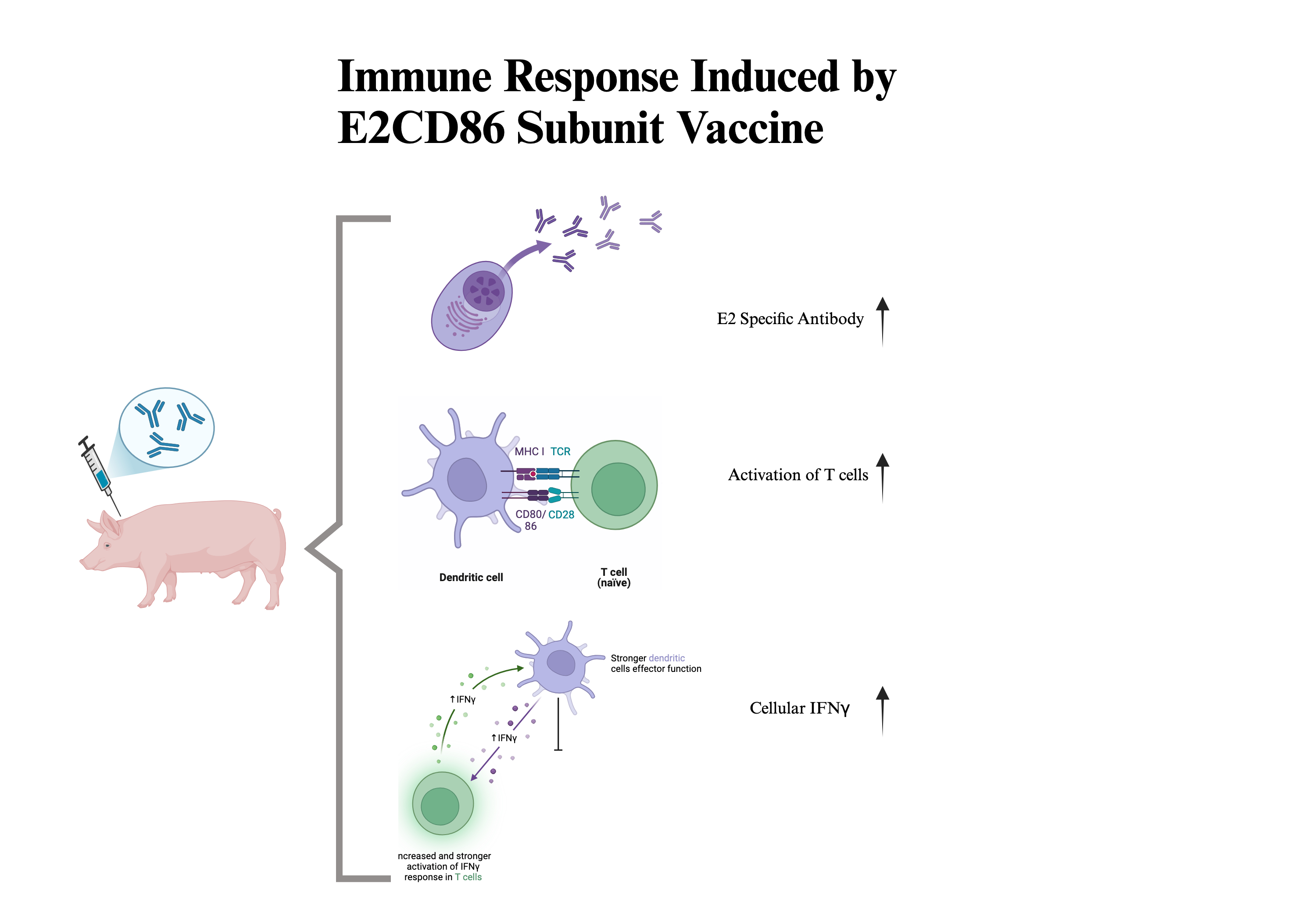

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. E2CD86 Vaccine Candidates

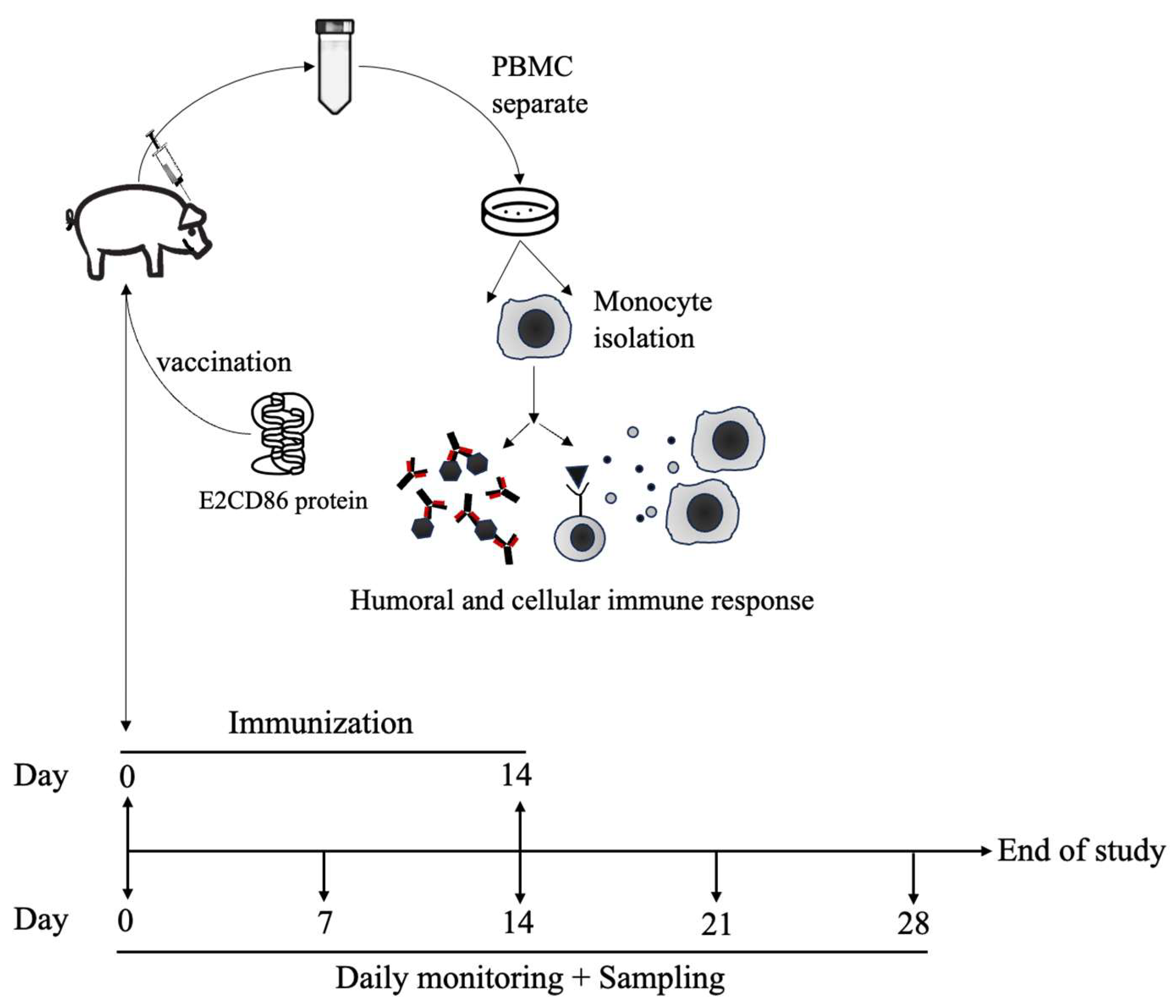

2.2. Experimental Animals and Immunization Schedules

2.3. Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cell (PBMC) Isolation

2.4. CSFV Neutralizing Antibody Detection

2.5. Flow Cytometry Analysis

2.6. IFN-γ Enzyme-Linked Immunospot (ELISpot) Assay

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

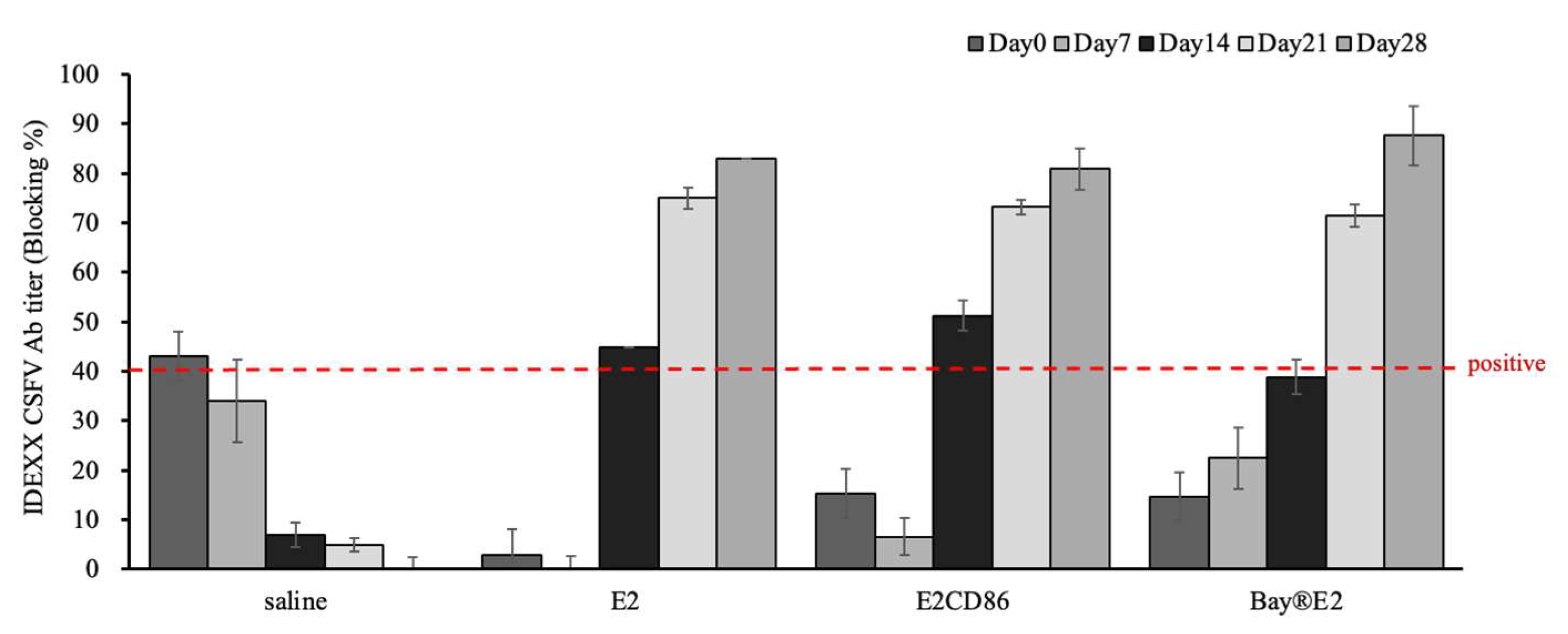

3.1. The E2CD86 Vaccine Provides Enhanced Protection in Piglets

3.2. The E2CD86 Vaccine Provides Enhanced Protection in Piglets

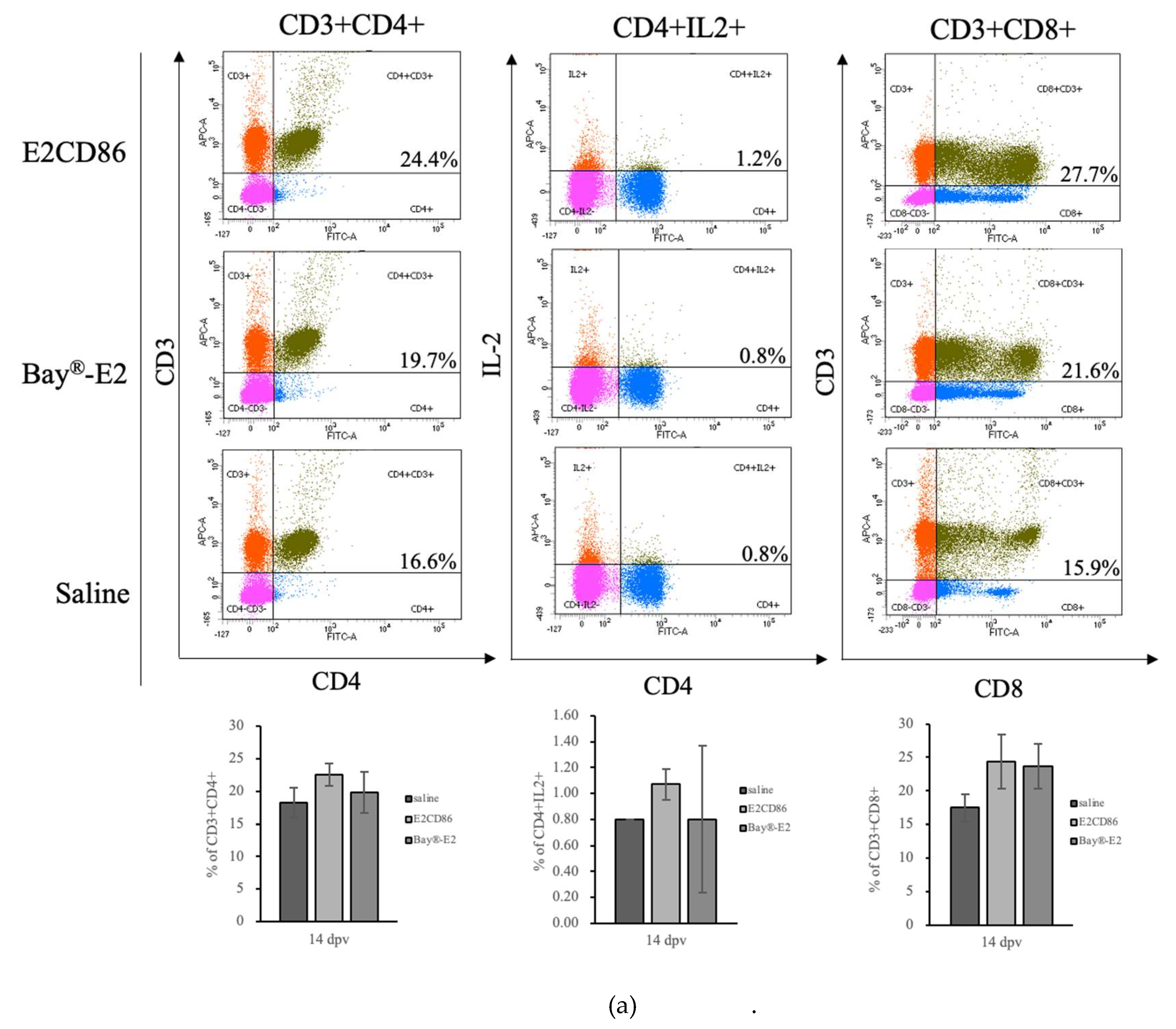

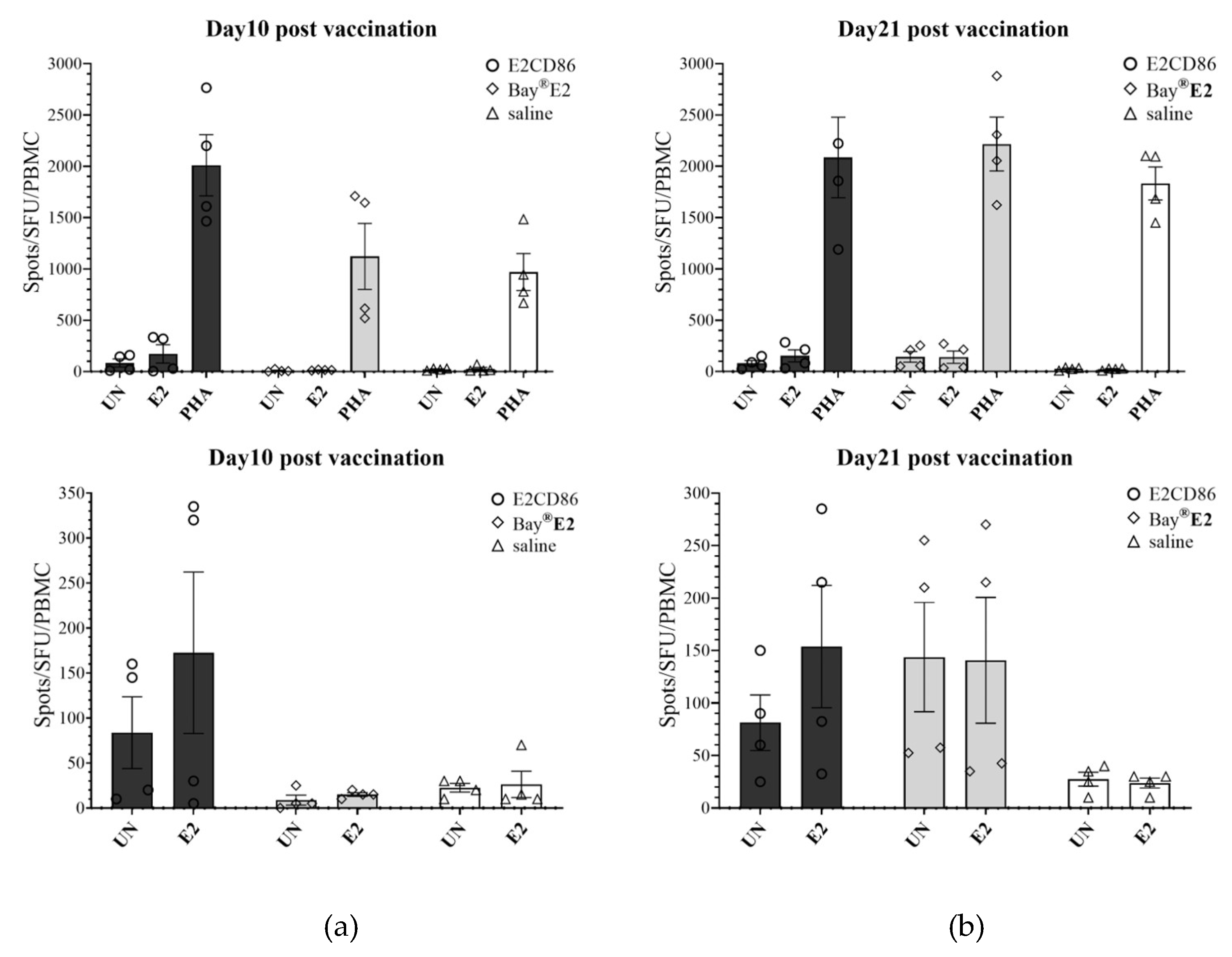

3.2.1. Immunogenicity of E2CD86 in Piglets with High Activation of T Cells

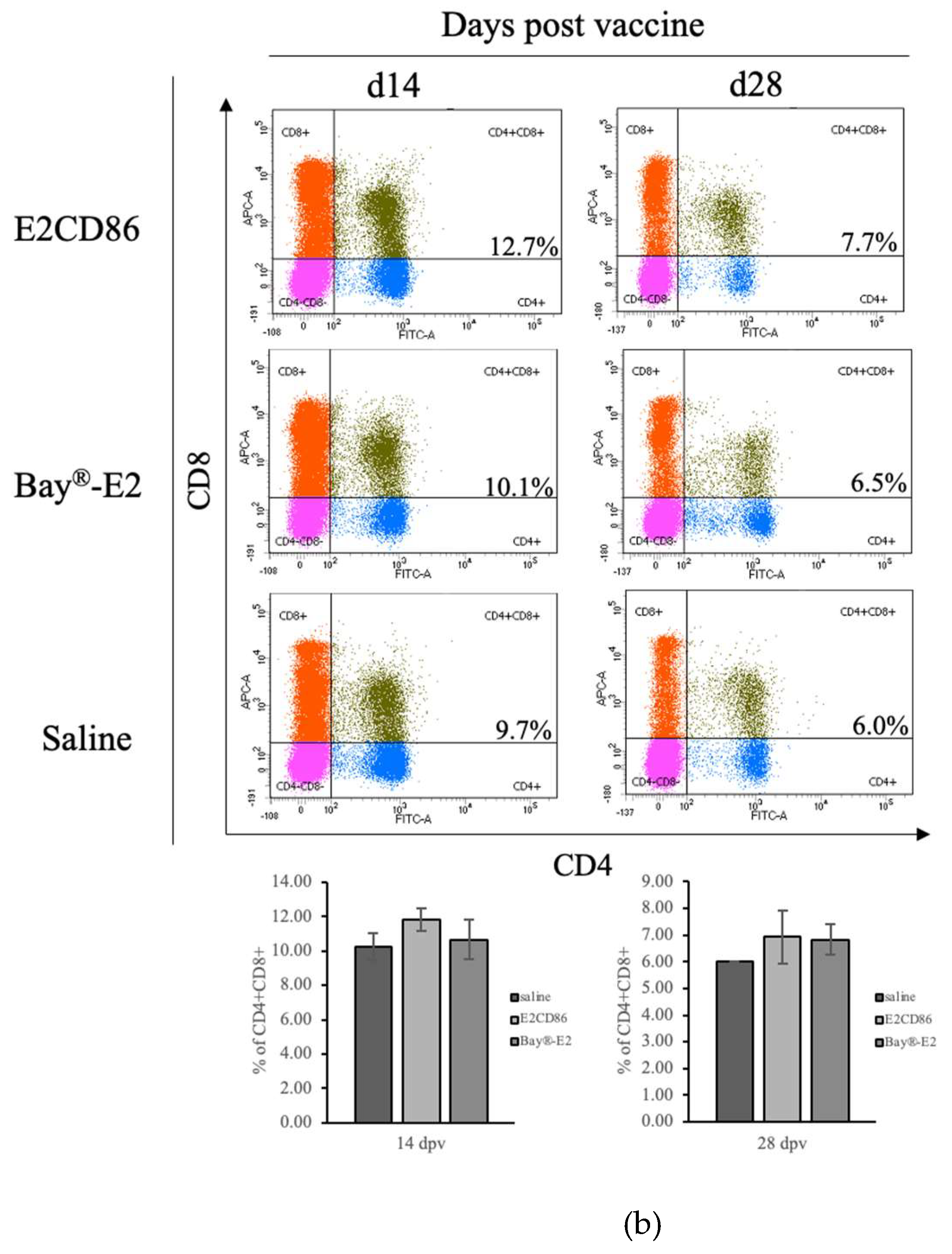

3.2.2. Increased Number of CD4+CD8+ Double-Positive cells After the E2CD86 Vaccine

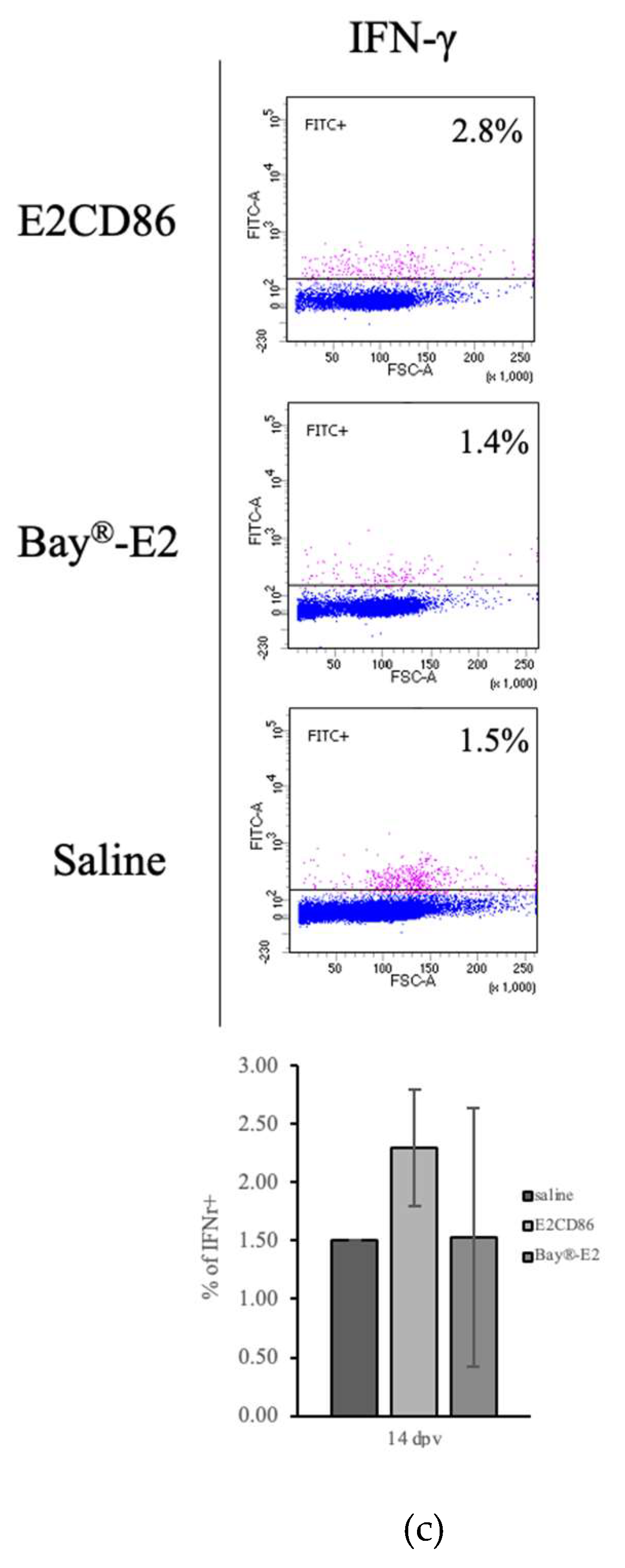

3.3. Immunogenicity of E2CD86 in Piglets with High Cellular IFNγ Expression

3.2. Figures, Tables and Schemes

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ganges, L.; Crooke, H.R.; Bohórquez, J.A.; Postel, A.; Sakoda, Y.; Becher, P.; Ruggli, N. Classical swine fever virus: The past, present and future. Virus Res. 2020, 289, 198151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Postel, A.; Smith, D.B.; Becher, P. Proposed Update to the Taxonomy of Pestiviruses: Eight Additional Species within the Genus Pestivirus, Family Flaviviridae. Viruses. 2021, 13, 1542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Blome, S.; Staubach, C.; Henke, J.; Carlson, J.; Beer, M. Classical Swine Fever-An Updated Review. Viruses. 2017, 9, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Blome, S.; Meindl-Böhmer, A.; Nowak, G.; Moennig, V. Disseminated intravascular coagulation does not play a major role in the pathogenesis of classical swine fever. Vet Microbiol. 2013, 162, 360–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beer, M.; Reimann, I.; Hoffmann, B.; Depner, K. Novel marker vaccines against classical swine fever. Vaccine. 2007, 25, 5665–5670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouma, A.; de Smit, A.J.; de Kluijver, E.P.; Terpstra, C.; Moormann, R.J. Efficacy and stability of a subunit vaccine based on glycoprotein E2 of classical swine fever virus. Vet Microbiol. 1999, 66, 101–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jasna, P.R.; Radoslav, D.; Vladimir, P.; Tamaš; P; Igor, S.; Radomir, R.; Miroslav, V. Classical Swine Fever: Active Immunisation of Piglets with Subunit (E2) Vaccine in the Presence of Different Levels of Colostral Immunity (China Strain). Acta Veterinaria, 2014, Sciendo, vol. 64 no. 4, pp. 493–509. [CrossRef]

- Madera, R.; Gong, W.; Wang, L.; Burakova, Y.; Lleellish, K.; Galliher-Beckley, A.; Nietfeld, J.; Henningson, J.; Jia, K.; Li, P.; Bai, J.; Schlup, J.; McVey, S.; Tu, C.; Shi, J. Pigs immunized with a novel E2 subunit vaccine are protected from subgenotype heterologous classical swine fever virus challenge. BMC Vet Res. 2016, 12, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Moormann, R.J.; Bouma, A.; Kramps, J.A.; Terpstra, C.; De Smit, H.J. Development of a classical swine fever subunit marker vaccine and companion diagnostic test. Vet Microbiol. 2000, 73, 209–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sordo-Puga, Y.; Suárez-Pedroso, M.; Naranjo-Valdéz, P.; Pérez-Pérez, D.; Santana-Rodríguez, E.; Sardinas-Gonzalez, T.; Mendez-Orta, M.K.; Duarte-Cano, C.A.; Estrada-Garcia, M.P.; Rodríguez-Moltó, M.P. Porvac® Subunit Vaccine E2-CD154 Induces Remarkable Rapid Protection against Classical Swine Fever Virus. Vaccines (Basel). 2021, 9, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Madera, R.; Gong, W.; Wang, L.; Burakova, Y.; Lleellish, K.; Galliher-Beckley, A.; Nietfeld, J.; Henningson, J.; Jia, K.; Li, P.; Bai, J.; Schlup, J.; McVey, S.; Tu, C.; Shi, J. Pigs immunized with a novel E2 subunit vaccine are protected from subgenotype heterologous classical swine fever virus challenge. BMC Vet Res. 2016, 12, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- van Aarle, P. Suitability of an E2 subunit vaccine of classical swine fever in combination with the E(rns)-marker-test for eradication through vaccination. Dev Biol (Basel) 2003, 114, 193–200. [Google Scholar]

- Suárez, M.; Sordo, Y.; Prieto, Y.; Rodríguez, M.P.; Méndez, L.; Rodríguez, E.M.; Rodríguez-Mallon, A.; Lorenzo, E.; Santana, E.; González, N.; Naranjo, P.; Frías, M.T.; Carpio, Y.; Estrada, M.P. A single dose of the novel chimeric subunit vaccine E2-CD154 confers early full protection against classical swine fever virus. Vaccine. 2017, 35, 4437–4443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armengol, E.; Wiesmüller, K.H.; Wienhold, D.; Büttner, M.; Pfaff, E.; Jung, G.; Saalmüller, A. Identification of T-cell epitopes in the structural and non-structural proteins of classical swine fever virus. J Gen Virol. 2002, 83(Pt 3):551-560. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ceppi, M.; de Bruin, M.G.M.; Seuberlich, T.; Balmelli, C.; Pascolo, S.; Ruggli, N.; Wienhold, D.; Tratschin, J.D.; McCullough, K.C.; Summerfield, A. Identification of classical swine fever virus protein E2 as a target for cytotoxic T cells by using mRNA-transfected antigen-presenting cells. J Gen Virol. 2005, 86(Pt 9):2525-2534. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rau, H.; Revets, H.; Balmelli, C.; McCullough, K.C.; Summerfield, A. Immunological properties of recombinant classical swine fever virus NS3 protein in vitro and in vivo. Vet Res. 2006, 37, 155–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toledo, J.R.; Barrera, M.; Farnós, O.; Gómez, S.; Rodríguez, M.P.; Aguero, F.; Ormazabal, V.; Parra, N.C.; Suárez, L.; Sánchez, O. Human αIFN co-formulated with milk derived E2-CSFV protein induce early full protection in vaccinated pigs. Vaccine. 2010, 28, 7907–7914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lanier, L.L.; O'Fallon, S.; Somoza, C.; Phillips, J.H.; Linsley, P.S.; Okumura, K.; Ito, D.; Azuma MCD80, (.B.7.).; CD86 (B70) provide similar costimulatory signals for T cell proliferation cytokine production generation of, C.T.L. J Immunol. 1995, 154, 97–105. [PubMed]

- Linsley, P.S.; Clark, E.A.; Ledbetter, J.A. T-cell antigen CD28 mediates adhesion with B cells by interacting with activation antigen B7/BB-1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990, 87, 5031–5035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Chen, C.; Nabavi, N. In vitro induction of T cell anergy by blocking B7 and early T cell costimulatory molecule ETC-1/B7-2. Immunity 1994, 1, 147–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenschow DJ, Ho SC, Sattar H, Rhee L, Gray G, Nabavi N; et al. Differential effects of anti-B7-1 and anti-B7-2 monoclonal antibody treatment on the development of diabetes in the nonobese diabetic mouse. J Exp Med 1995, 181, 1145–1155. [CrossRef]

- Bour-Jordan, H.; Blueston, J.A. CD28 function: A balance of costimulatory and regulatory signals. J Clin Immunol. 2002, 22, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beyersdorf, N.; Kerkau, T.; Hünig, T. CD28 co-stimulation in T-cell homeostasis: A recent perspective. Immunotargets Ther. 2015, 4, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Carosella, E.D.; Ploussard, G.; LeMaoult, J.; Desgrandchamps, F. A Systematic Review of Immunotherapy in Urologic Cancer: Evolving Roles for Targeting of CTLA-4, PD-1/PD-L1, and HLA-G. Eur Urol. 2015, 68, 267–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, P.; Gao, J.F.; D'Souza, C.A.; Kowalczyk, A.; Chou, K.Y.; Zhang, L. Trogocytosis of CD80 and CD86 by induced regulatory T cells. Cell Mol Immunol. 2012, 9, 136–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Miller, J.; Baker, C.; Cook, K.; Graf, B.; Sanchez-Lockhart, M.; Sharp, K.; Wang, X.; Yang, B.; Yoshida, T. Two pathways of costimulation through CD28. Immunol Res. 2009, 45, 159–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Freeman, G.J.; Freedman, A.S.; Segil, J.M.; Lee, G.; Whitman, J.F.; Nadler, L.M. B7, a new member of the Ig superfamily with unique expression on activated and neoplastic B cells. J Immunol. 1989, 143, 2714–2722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azuma, M.; Ito, D.; Yagita, H.; Okumura, K.; Phillips, J.H.; Lanier, L.L.; Somoza, C. B70 antigen is a second ligand for CTLA-4 and CD28. Nature. 1993, 366, 76–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freedman, A.S.; Freeman, G.J.; Rhynhart, K.; Nadler, L.M. Selective induction of B7/BB-1 on interferon-gamma stimulated monocytes: A potential mechanism for amplification of T cell activation through the CD28 pathway. Cell Immunol 1991, 137, 429–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hathcock, K.S.; Laszlo, G.; Pucillo, C.; Linsley, P.; Hodes, R.J. Comparative analysis of B7-1 and B7-2 costimulatory ligands: Expression and function. J Exp Med 1994, 180, 631–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stack, R.M.; Lenschow, D.J.; Gray, G.S.; Bluestone, J.A.; Fitch, F.W. IL-4 treatment of small splenic B cells induces costimulatory molecules B7-1 and B7-2. J Immunol 1994, 152, 5723–5733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.J.; Bagarazzi, M.L.; Trivedi, N.; Hu, Y.; Kazahaya, K.; Wilson, D.M.; Ciccarelli, R.; Chattergoon, M.A.; Dang, K.; Mahalingam, S.; Chalian, A.A.; Agadjanyan, M.G.; Boyer, J.D.; Wang, B.; Weiner, D.B. Engineering of in vivo immune responses to DNA immunization via codelivery of costimulatory molecule genes. Nat Biotechnol. 1997, 15, 641–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yüksel, S.; Pekcan, M.; Puralı, N.; Esendağlı, G.; Tavukçuoğlu, E.; Rivero-Arredondo, V.; Ontiveros-Padilla, L.; López-Macías, C.; Şenel, S. Development and in vitro evaluation of a new adjuvant system containing Salmonella Typhi porins and chitosan. Int J Pharm. 2020, 578, 119129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, C.H.; Jong, M.H.; Huang, T.S.; Liu, H.F.; Lin, S.Y.; Lai, S.S. Phylogenetic analysis of classical swine fever virus in Taiwan. Arch Virol. 2005, 150, 1101–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Cheng & Huang, Qiong-Yi & Wang, Pei-Chi & Tsai, Ming-An & Chen, shih-chu. Transcriptome and pathophysiological analysis during Bacillus cereus group infection in Pelodiscus sinensis uncovered the importance of iron and toll like receptor pathway. Aquaculture. 2024, 594, 741424. [CrossRef]

- Yanjuan Jia, Hui Xu, Yonghong Li, Chaojun Wei, Rui Guo, Fang Wang, Yu Wu, Jing Liu, Jing Jia, Junwen Yan, Xiaoming Qi, Yuanting Li, Xiaoling Gao. A Modified Ficoll-Paque Gradient Method for Isolating Mononuclear Cells from the Peripheral and Umbilical Cord Blood of Humans for Biobanks and Clinical Laboratories. Biopreserv Biobank. 2018, 16, 82–91. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tai, Y.; Wang, Q.; Korner, H.; Zhang, L.; Wei, W. Molecular Mechanisms of T Cells Activation by Dendritic Cells in Autoimmune Diseases. Front Pharmacol. 2018, 9, 642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Laidlaw, B.J.; Craft, J.E.; Kaech, S.M. The multifaceted role of CD4(+) T cells in CD8(+) T cell memory. Nat Rev Immunol. 2016, 16, 102–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Overgaard, N.H.; Jung, J.W.; Steptoe, R.J.; Wells, J.W. CD4+/CD8+ double-positive T cells: More than just a developmental stage? J Leukoc Biol. 2015, 97, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, S.M.; Park, H.J.; Choi, E.A.; Jung, K.C.; Lee, J.I. Cellular heterogeneity of circulating CD4+CD8+ double-positive T cells characterized by single-cell RNA sequencing. Sci Rep. 2021, 11, 23607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Van Kaer, L.; Rabacal, W.A.; Scott Algood, H.M.; Parekh, V.V.; Olivares-Villagómez, D. In vitro induction of regulatory CD4+CD8α+ T cells by TGF-β, IL-7 and IFN-γ. PLoS ONE. 2013, 8, e67821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Saatkamp, H.W.; Berentsen, P.B.; Horst, H.S. Economic aspects of the control of classical swine fever outbreaks in the European Union. Vet Microbiol. 2000, 73, 221–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dahle, J.; Liess, B. Assessment of safety and protective value of a cell culture modified strain "C" vaccine of hog cholera/classical swine fever virus. Berl Munch Tierarztl Wochenschr. 1995, 108, 20–25. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gong, W.; Li, J.; Wang, Z.; Sun, J.; Mi, S.; Xu, J.; Cao, J.; Hou, Y.; Wang, D.; Huo, X.; Sun, Y.; Wang, P.; Yuan, K.; Gao, Y.; Zhou, X.; He, S.; Tu, C. Commercial E2 subunit vaccine provides full protection to pigs against lethal challenge with 4 strains of classical swine fever virus genotype 2. Vet Microbiol. 2019, 237, 108403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perrie, Y.; Mohammed, A.R.; Kirby, D.J.; McNeil, S.E.; Bramwell, V.W. Vaccine adjuvant systems: Enhancing the efficacy of sub-unit protein antigens. Int J Pharm. 2008, 364, 272–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Genmei, L.; Manlin, L.; Ruiai, C.; Hongliang, H.; Dangshuai, P. Construction and immunogenicity of recombinant adenovirus expressing ORF2 of PCV2 and porcine IFN gamma. Vaccine. 2011, 29, 8677–8682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suárez-Pedroso, M.; Sordo-Puga, Y.; Sosa-Teste, I.; Rodriguez-Molto, M.P.; Naranjo-Valdés, P.; Sardina-González, T.; Santana-Rodríguez, E.; Montero-Espinosa, C.; Frías-Laporeaux, M.T.; Fuentes-Rodríguez, Y.; Pérez-Pérez, D.; Oliva-Cárdenas, A.; Pereda, C.L.; González-Fernández, N.; Bover-Fuentes, E.; Vargas-Hernández, M.; Duarte, C.A.; Estrada-García, M.P. Novel chimeric E2CD154 subunit vaccine is safe and confers long lasting protection against classical swine fever virus. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 2021, 234, 110222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lenschow, D.J.; Su, G.H.; Zuckerman, L.A.; Nabavi, N.; Jellis, C.L.; Gray, G.S.; Miller, J.; Bluestone, J.A. Expression and functional significance of an additional ligand for CTLA-4. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993, 90, 11054–11058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Said, E.A.; Al-Reesi, I.; Al-Riyami, M.; Al-Naamani, K.; Al-Sinawi, S.; Al-Balushi, M.S.; Koh, C.Y.; Al-Busaidi, J.Z.; Idris, M.A.; Al-Jabri, A.A. Increased CD86 but Not CD80 and PD-L1 Expression on Liver CD68+ Cells during Chronic HBV Infection. PLoS ONE. 2016, 11, e0158265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sun, R.; Yang, Y.; Gu, Z.; Tang, X.; Zhang, C.; Kou, W.; Wei, P. Silencing of CD86 in dendritic cells by small interfering RNA regulates cytokine production in T cells from patients with allergic rhinitis in vitro. Mol Med Rep. 2019, 20, 3893–3900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Köchli, C.; Wendland, T.; Frutig, K.; Grunow, R.; Merlin, S.; Pichler, W.J. CD80 and CD86 costimulatory molecules on circulating T cells of HIV infected individuals. Immunol Lett. 1999, 65, 197–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niederlova, V.; Tsyklauri, O.; Kovar, M.; Stepanek, O. IL-2-driven CD8+ T cell phenotypes: Implications for immunotherapy. Trends Immunol. 2023, 44, 890–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Spolski, R.; Li, P.; Leonard, W.J. Biology and regulation of IL-2: From molecular mechanisms to human therapy. Nat Rev Immunol. 2018, 18, 648–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Epstein, S.L.; Lo, C.Y.; Misplon, J.A.; Bennink, J.R. Mechanism of protective immunity against influenza virus infection in mice without antibodies. J Immunol. 1998, 160, 322–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yap, K.L.; Ada, G.L.; McKenzie, I.F. Transfer of specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes protects mice inoculated with influenza virus. Nature. 1978, 273, 238–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franzoni, G.; Kurkure, N.V.; Essler, S.E.; Pedrera, M.; Everett, H.E.; Bodman-Smith, K.B.; Crooke, H.R.; Graham, S.P. Proteome-wide screening reveals immunodominance in the CD8 T cell response against classical swine fever virus with antigen-specificity dependent on MHC class I haplotype expression. PLoS ONE. 2013, 8, e84246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Moraes, M.P.; de Los Santos, T.; Koster, M.; Turecek, T.; Wang, H.; Andreyev, V.G.; Grubman, M.J. Enhanced antiviral activity against foot-and-mouth disease virus by a combination of type I and II porcine interferons. J Virol. 2007, 81, 7124–7135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wang, Y.P.; Liu, D.; Guo, L.J.; Tang, Q.H.; Wei, Y.W.; Wu, H.L.; Liu, J.B.; Li, S.B.; Huang, L.P.; Liu, C.M. Enhanced protective immune response to PCV2 subunit vaccine by co-administration of recombinant porcine IFN-γ in mice. Vaccine. 2013, 31, 833–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eichinger, K.M.; Resetar, E.; Orend, J.; Anderson, K.; Empey, K.M. Age predicts cytokine kinetics and innate immune cell activation following intranasal delivery of IFNγ and GM-CSF in a mouse model of RSV infection. Cytokine. 2017, 97, 25–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Whitmire, J.K.; Tan, J.T.; Whitton, J.L. Interferon-gamma acts directly on CD8+ T cells to increase their abundance during virus infection. J Exp Med. 2005, 201, 1053–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Desfrançois, J.; Moreau-Aubry, A.; Vignard, V.; Godet, Y.; Khammari, A.; Dréno, B.; Jotereau, F.; Gervois, N. Double positive CD4CD8 alphabeta T cells: A new tumor-reactive population in human melanomas. PLoS ONE. 2010, 5, e8437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Parel, Y.; Chizzolini, C. CD4+ CD8+ double positive (DP) T cells in health and disease. Autoimmun Rev. 2004, 3, 215–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, Y.J.; Park, H.J.; Park, H.J.; Jung, K.C.; Lee, J.I. CD4hiCD8low Double-Positive T Cells Are Associated with Graft Rejection in a Nonhuman Primate Model of Islet Transplantation. J Immunol Res. 2018, 2018, 3861079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Nascimbeni, M.; Pol, S.; Saunier, B. Distinct CD4+ CD8+ double-positive T cells in the blood and liver of patients during chronic hepatitis B and C. PLoS ONE. 2011, 6, e20145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Nascimbeni, M.; Shin, E.C.; Chiriboga, L.; Kleiner, D.E.; Rehermann, B. Peripheral CD4(+)CD8(+) T cells are differentiated effector memory cells with antiviral functions. Blood. 2004, 104, 478–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ribrag, V.; Salmon, D.; Picard, F.; Guesnu, M.; Sicard, D.; Dreyfus, F. Increase in double-positive CD4+CD8+ peripheral T-cell subsets in an HIV-infected patient. AIDS. 1993, 7, 1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zahran, A.M.; Zahran, Z.A.M.; Mady, Y.H.; Mahran, E.E.M.O.; Rashad, A.; Makboul, A.; Nasif, K.A.; Abdelmaksoud, A.A.; El-Badawy, O. Differential alterations in peripheral lymphocyte subsets in COVID-19 patients: Upregulation of double-positive and double-negative T cells. Multidiscip Respir Med. 2021, 16, 758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zou, S.; Tan, Y.; Xiang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhu, Q.; Wu, S.; Guo, W.; Luo, M.; Shen, L.; Liang, K. The Role of CD4+CD8+ T Cells in HIV Infection With Tuberculosis. Front Public Health. 2022, 10, 895179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Akari, H.; Terao, K.; Murayama, Y.; Nam, K.H.; Yoshikawa, Y. Peripheral blood CD4+CD8+ lymphocytes in cynomolgus monkeys are of resting memory T lineage. Int Immunol. 1997, 9, 591–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Kaer, L.; Rabacal, W.A.; Scott Algood, H.M.; Parekh, V.V.; Olivares-Villagómez, D. In vitro induction of regulatory CD4+CD8α+ T cells by TGF-β, IL-7 and IFN-γ. PLoS ONE. 2013, 8, e67821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Quandt, D.; Rothe, K.; Scholz, R.; Baerwald, C.W.; Wagner, U. Peripheral CD4CD8 double positive T cells with a distinct helper cytokine profile are increased in rheumatoid arthritis. PLoS ONE. 2014, 9, e93293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kerstein, A.; Müller, A.; Pitann, S.; Riemekasten, G.; Lamprecht, P. Circulating CD4+CD8+ double-positive T-cells display features of innate and adaptive immune function in granulomatosis with polyangiitis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2018, 36 (Suppl. S111), 93–98. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Waschbisch, A.; Sammet, L.; Schröder, S.; Lee, D.H.; Barrantes-Freer, A.; Stadelmann, C.; Linker, R.A. Analysis of CD4+ CD8+ double-positive T cells in blood, cerebrospinal fluid and multiple sclerosis lesions. Clin Exp Immunol. 2014, 177, 404–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Chauhan, N.K.; Vajpayee, M.; Mojumdar, K.; Singh, R.; Singh, A. Study of CD4+CD8+ double positive T-lymphocyte phenotype and function in Indian patients infected with HIV-1. J Med Virol. 2012, 84, 845–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, B.; Hu, S.; Fu, X.; Li, L. CD4+ Cytotoxic T Lymphocytes in Cancer Immunity and Immunotherapy. Adv Biol (Weinh). 2023, 7, e2200169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murayama, K.; Ikegami, I.; Kamekura, R.; Sakamoto, H.; Yanagi, M.; Kamiya, S.; Sato, T.; Sato, A.; Shigehara, K.; Yamamoto, M.; Takahashi, H.; Takano, K.I.; Ichimiya, S. CD4+CD8+ T follicular helper cells regulate humoral immunity in chronic inflammatory lesions. Front Immunol. 2022, 13, 941385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Graham, S.P.; Haines, F.J.; Johns, H.L.; Sosan, O.; La Rocca, S.A.; Lamp, B.; Rümenapf, T.; Everett, H.E.; Crooke, H.R. Characterisation of vaccine-induced, broadly cross-reactive IFN-γ secreting T cell responses that correlate with rapid protection against classical swine fever virus. Vaccine. 2012, 30, 2742–2748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franzoni, G.; Kurkure, N.V.; Edgar, D.S.; Everett, H.E.; Gerner, W.; Bodman-Smith, K.B.; Crooke, H.R.; Graham, S.P. Assessment of the phenotype and functionality of porcine CD8 T cell responses following vaccination with live attenuated classical swine fever virus (CSFV) and virulent CSFV challenge. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2013, 20, 1604–1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Franzoni, G.; Edwards, J.C.; Kurkure, N.V.; Edgar, D.S.; Sanchez-Cordon, P.J.; Haines, F.J.; Salguero, F.J.; Everett, H.E.; Bodman-Smith, K.B.; Crooke, H.R.; Graham, S.P. Partial Activation of natural killer and γδ T cells by classical swine fever viruses is associated with type I interferon elicited from plasmacytoid dendritic cells. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2014, 21, 1410–1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Perrie, Y.; Mohammed, A.R.; Kirby, D.J.; McNeil, S.E.; Bramwell, V.W. Vaccine adjuvant systems: Enhancing the efficacy of sub-unit protein antigens. Int J Pharm. 2008, 364, 272–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).