1. Introduction

Electricity theft, a longstanding challenge for utility companies, has evolved with the advent of smart grids. In addition to traditional physical attacks (such as meter bypassing), modern cyberattacks (like spoofing and man-in-the-middle attacks) now target electronic meters, often leveraging low-cost, easily accessible tools. This shift towards cyberattacks is particularly prominent in advanced power systems. The economic impact is severe, with global losses reaching

$96 billion in 2017 [

1], especially in developing countries such as India. Electricity theft not only results in financial losses but also leads to inaccurate power demand forecasts, contributing to poor power quality and infrastructure damage. Furthermore, it hampers investments in advanced technologies and safety measures. Despite strict regulations in various countries, the strong economic incentives continue to fuel electricity theft.

Recently, based on the massive amount of data provided by the advanced metering infrastructure (AMI), deep neural network (DNN)-based electricity theft detection (ETD) schemes have been widely developed [

2,

3], since DNNs can automatically extract features and have powerful functional approximation ability. Generally, from the perspective of learning paradigm, the existing schemes can be classified into two categories: supervised learning-based and unsupervised learning-based. (1) Supervised DNNs are trained using both normal and abnormal samples, typically requiring a large number of labeled samples while ensuring that the quantities of normal and abnormal samples are balanced. However, in smart grids, it is impractical to obtain a large number of electricity theft samples, leading to a data imbalance between abnormal and normal samples. Under such circumstances, supervised models struggle to learn the general features of abnormal samples, resulting in poor detection performance when faced with new electricity theft methods. Many supervised learning-based studies have leveraged the periodicity in electricity consumption data to distinguish between electricity theft and normal usage. For example, several studies have transformed one-dimensional electricity consumption data into two-dimensional matrices and employed various DNNs to capture the underlying periodicity. ETD-ConvLSTM (Electricity Theft Detector based upon Convolutional Long Short Term Memory neural networks) [

4] uses a ConvLSTM network to capture the periodic patterns in users’ consumption. HORLN ( Hybrid-order Representation Learning Network) [

5] uses the autocorrelation function to determine whether there is periodicity in different electricity consumption data. Additionally, some studies (e.g., Reference [

6]) convert the electricity data into graphs and leverage Graph Convolutional Networks (GCNs) to capture the periodicity within the graph structure. However, the aforementioned DNNs do not inherently capture temporal dependencies and fail to fully exploit the periodic features. Although HORLN uses autocorrelation to highlight the capture of periodic characteristics, it only incorporates it as a second-order feature, merging it with first-order feature information. (2) Unsupervised DNNs focus on capturing the characteristics of normal electricity consumption data, offering an effective solution to the data imbalance problem commonly faced by supervised DNNs. Reference [

7] proposes a deep learning-based electricity theft cyberattack detection method for AMIs, combining stacked autoencoders with an LSTM (Long Short Term Memory neural networks)-based sequence-to-sequence (seq2seq) structure to capture sophisticated patterns and temporal correlations in electricity consumption data. Reference [

8] proposes a novel unsupervised two-stage approach for electricity theft detection, combining a Gaussian mixture model to cluster consumption patterns and an attention-based bidirectional LSTM encoder-decoder to enhance robustness against non-malicious changes. A novel anomaly score is proposed, which comprehensively considers the similarity of consumption patterns and reconstruction errors. Reference [

9] proposes a stacked sparse denoising autoencoder for electricity theft detection, leveraging the reconstruction error of anomalous behaviors to identify theft users. However, existing unsupervised DNNs also have not fully exploited the periodic features in electricity consumption data.

Based on the above considerations, we propose a periodicity-enhanced deep one-class classification framework (PE-DOCC) based on periodicty-enhanced transformer encoder, named Periodicformer encoder. The main contributions of this paper can be summarized as follows.

We propose a novel PE-DOCC framework for detecting electricity theft, which incorporates unsupervised representation learning (i.e., pre-train Periodicformer encoder by recovering partially masked input sequences) and one-class classification (anomaly detection based on local outlier factor);

To extract richer periodic features, within encoder a novel Criss-Cross Periodic Attention (CCPA) is proposed, which comprehensively considers both the horizontal and vertical periodic features;

Extensive experiments of ETD using the Irish data set are conducted to compare the performance with various state-of-the-art methods. Appropriate metrics are selected for evaluation and the effectiveness of the proposed ETD scheme is verified.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. In Section II, typical one-class (OC) classification (including traditional machine learning-based and recent deep learning-based) ETD schemes are summarized. Section III presents the proposed ETD framework PE-DOCC and describes its main module in detail. Section IV provides the comprehensive performance comparison between the proposed framework and state-of-the-art ETD methods. Finally, we briefly conclude this paper.

2. Related Work

Unsupervised anomaly detection for electricity theft (and similar issues) is a highly challenging task, and over the past few years, various methods have been proposed to address it.

One traditional type is classifcation-based methods. Reference [

10] proposes a feature selection algorithm for mixed load data with statistical features based on random forest (FS-MLDRF) to reduce the dimension of user data, and then use the hybrid random forest and weighted support vector data description (HFR-WSVDD) to address the data imbalance issue. Reference [

11] proposes a privacy-preserving anomaly detection approach for LoRa-based IoT networks using Federated Learning. SVOC [

12], a data-driven approach to detect gas-theft suspects among boiler room users, combines scenario-based data quality detection, deformation-based normality detection, and an OCSVM (One-class Support Vector Machine)-based anomaly detection algorithm. Another common method is ensemble-based methods. TiWS-iForest [

13] incorporates weak supervision to reduce complexity and enhance anomaly detection performance. The approach addresses the limitations of standard iForest (Isolation Forest) in terms of memory, latency, and efficiency, particularly in low-resource environments like TinyML implementations on ultra-constrained microprocessors. Additionally, density-based methods e.g. ELOF [

14] (Ensemble Local Outlier Factor) integrates multiple LOF models with optimized hyperparameters and distance metrics.

Besides traditional methods, deep learning-based unsupervised anomaly detection algorithms have gained a lot attention recently. Tab-iForest [

15] combines the TabNet deep learning model with the Isolation Forest algorithm, where TabNet selects relevant features through pre-training and inputs them into Isolation Forest for anomaly detection. Reference [

16] combines autoencoding and one-class classification, designed to benefit from strong abstraction by neural networks (using an autoencoder) and the removal of the complex threshold selection (using an OC classifier). A new model selection method that discovers well-optimized models from a variety of combinations is also proposed. Reference [

17] proposes a two-step electricity theft detection strategy to enhance economic returns for power companies. It uses a convolutional autoencoder (CAE) to identify electricity theft and the Tr-XGBoost regression algorithm which combines XGBoost (Extreme Gradient Boosting) with TrAdaBoost (Transfer Adaptive Boosting) strategy, to predict potentially stolen electricity (PSE).

To sum up, deep learning-based unsupervised anomaly detection methods typically begin by using deep neural networks (e.g., autoencoders) to extract temporal dependencies and periodic features present in electricity data. The features output by the DNN are often low-dimensional, addressing the curse of dimensionality that traditional machine learning struggles with. These extracted features are then analyzed through one-class classification, effectively tackling the data imbalance issue between normal and anomalous data.

3. Proposed Framework: PE-DOCC

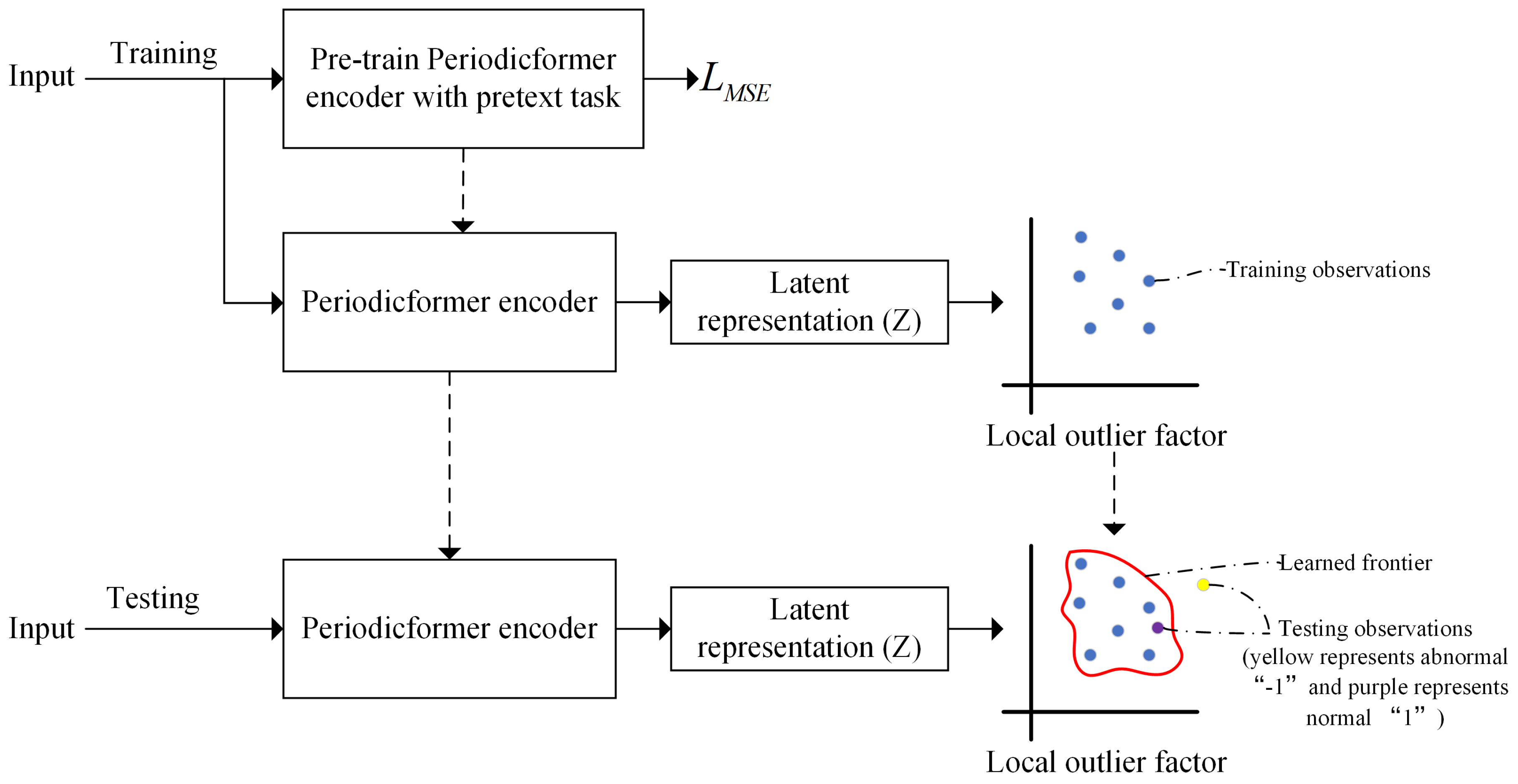

Figure 1 presents the proposed ETD framework, which explicitly consists of two main phases: model training and model testing. The training phase consists of two steps: Step 1: Pretrain the Periodicformer encoder by recovering partially masked input sequences (i.e., unsupervised representation learning). Step 2: Feed the latent representations output by the encoder into local outlier factor (LOF) to learn the anomaly detection boundary. In the testing phase, the input data is fed through the trained Periodicformer encoder and classifier to determine whether testing latent representation is within the trained boundary (1) or not (-1).

3.1. Periodicformer Encoder for Unsupervised Representation Learning

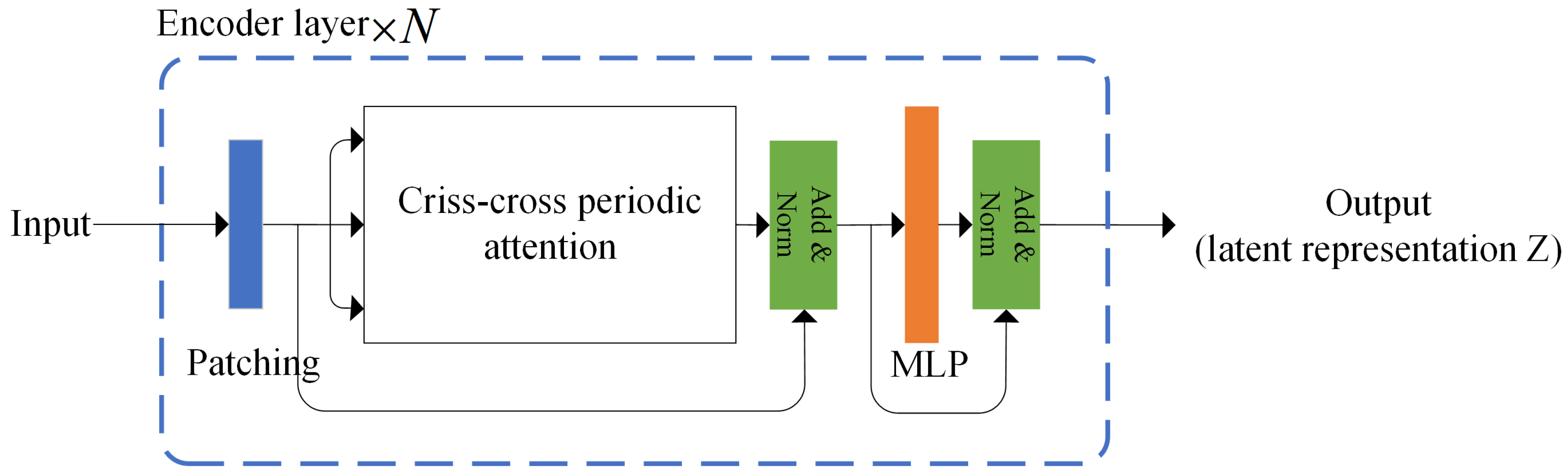

Figure 2 illustrates the overall architecture of the proposed Periodicformer encoder, which is composed of three modules: patching module, the proposed Criss-cross periodic attention module and the multilayer perceptron (MLP) module (consisting of two linear layers with a gelu activation).

In the layer i, we denote the patch size as , the length of input feature as , and the embedding dimension as d.

3.1.1. Patching Operation

The input feature for layer i is first divided into multiple patches ( is the number of the patches, each patch ), then flatten these patches and embeds them into a new feature map .

It is worth noting that we do not use positional encoding here, as our experimental results show that adding positional encoding actually reduces detection performance, which is consistent with the findings in Reference [

18].

3.1.2. Criss-Cross Periodic Attention

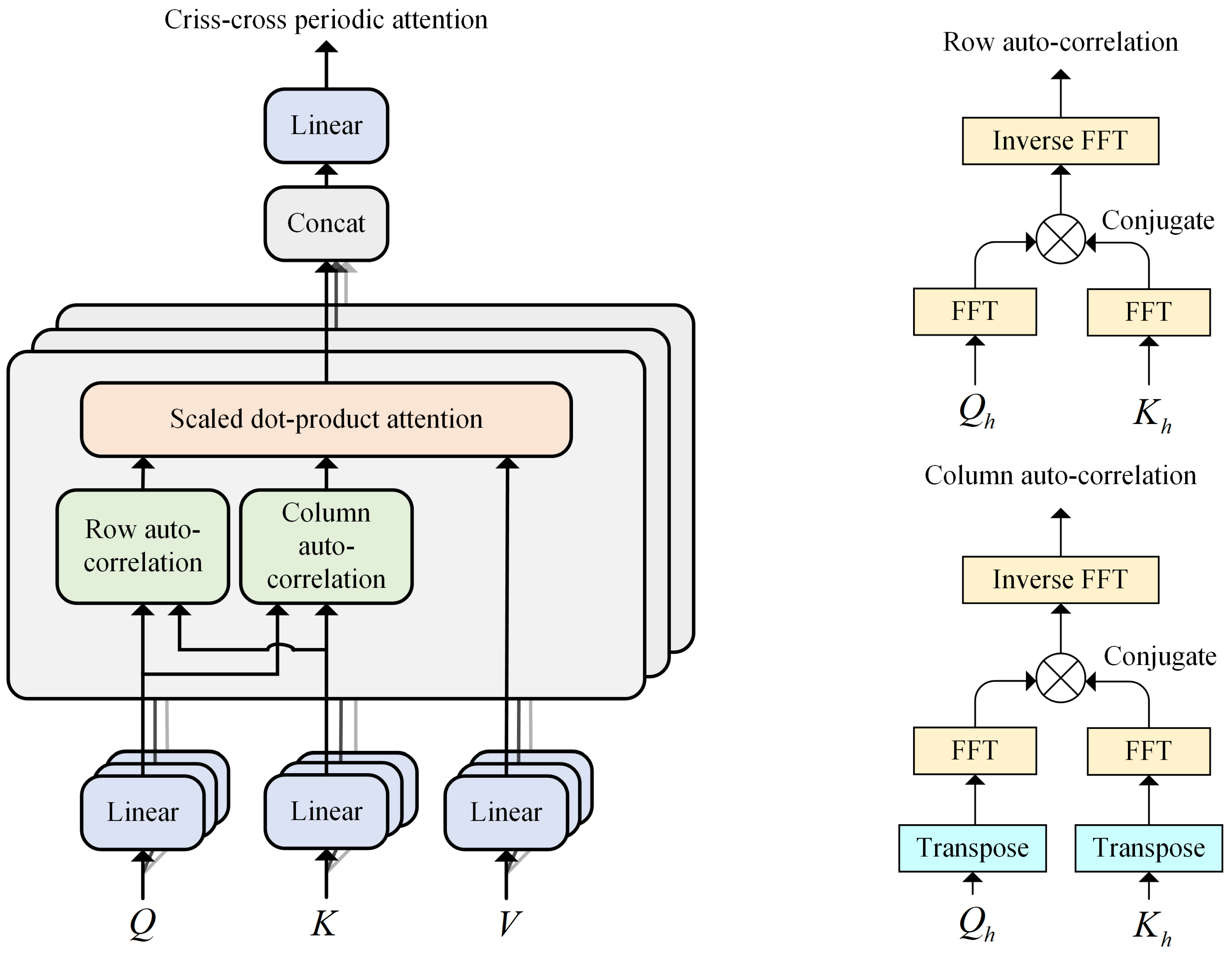

As shown in

Figure 3, we propose the criss-cross periodic attention mechanism to mine richer periodic scale characteristics. Row autocorrelation and column autocorrelation explore periodic dependencies by calculating autocorrelation.

-

Period-based dependencies: Inspired by Auto-Correlation mechanism [

19], for an input sequence

with length

L, we can obtain the autocorrelation

by the following Equation

1.

reflects the time-delay similarity between

and its

lag series

. Taking the Row auto-correlation in

Figure 3 as an example, for single head

h and input sequence

where

, after the linear projector, we get query

, key

and value

. At this point, we consider

as sequences along the row direction, i.e.,

where

is the embedding dimension of

, with

treated in the same manner. Then we can obtain the Row auto-correlation

by the following Equation

2.

where

is the autocorrelation between

and

. The calculation of column auto-correlation is similar to that of Row auto-correlation, with the only difference being that

and

are treated as sequences along the column direction. The formula for calculating Column auto-correlation is provided in Equation

3.

where

is the autocorrelation between the transpose of

and the transpose of

;

-

Criss-cross periodic attention: To comprehensively capture the different periodic features extracted by row and column auto-correlation, we use the scaled dot product attention, with the product of row and column auto-correlation serving as the new attention weights. For single head

h, the Criss-cross periodic attention (CCPA) mechanism is as the following Equation

4.

For the multi-head version, with

H heads, the process is as Equation

5;

Efficient computation: For the autocorrelation computation (Equation

1), given input sequence

,

can be calculated by the Fast Fourier Transforms (FFT) as Equation

6:

where

,

denotes FFT and

is its inverse transformation. * denotes the conjugate operation and

is in the frequency domain.

3.1.3. Unsupervised Representation Learning

Electricity consumption data is treated as a univariate time series of length

T, expressed as

. To determine whether the data point

at time

t is an anomaly, we analyze a contextual window of length

L, defined as

, instead of focusing solely on a single point. For simplicity, windows

are omitted when

[

20].

Unsupervised representation learning involves two steps: creating a Boolean mask M and calculating the mean squared error (MSE) loss. The mask M is generated with alternating segments of 0s and 1s, where the lengths of the 0s and 1s follow geometric distributions with means and , respectively. The proportion r determines the ratio of 0s in the mask, and the length is computed as . The masked detection window is then passed through the encoder, producing feature representation Z. The output Z is flattened and passed through a linear layer to forecast the masked values, yielding . The MSE loss is computed by comparing the predicted values to the actual masked values at the indices in , which are the positions where . The overall process of unsupervised representation learning is described in detail in Algorithm 1.

Note that, the objective of the unsupervised representation learning is to learn latent representations Z for subsequent one-class classification-based anomaly detection. In the subsequent anomaly detection process, the linear layer originally used for outputting the masked time-series is discarded.

3.2. One-Class Classifier for Anomaly Detection

Once the unsupervised training is completed, the training data is rejected into the trained Periodicformer encoder and the latent representation () is fed to the local outlier factor (LOF) as input where is the number of training data.

LOF is a density-based outlier detection algorithm. The determination of the outlier is judged based on the density between each data point and its neighbor points. The lower the density of the point, the more likely it is to be identified as the outlier. The key definitions for the LOF are as follows:

-

Defination 1:

-

k-distance of data point . For a given dataset D and any positive integer k, the k-distance of denoted as , is defined as the distance between data point and data point in the following conditions:

for at least k data points it holds that ;

for at most objects it holds that .

-

Defination 2:

k-distance neighborhood of data point

. Given the k-distance of

, the k-distance neighborhood of

contains every data point

whose distance from

is not greater than the k-distance, as described in Equation

7.

-

Definition 3:

reachability distance of data point

with respect to data point

. Let

k be a natural number. The reachability distance of

with respect to

is defined as Equation

8.

-

Definition 4:

local reachability density of data point

. The local reachability density of

is defined as Equation

9.

where

is the k-distance neighborhood of data point

.

-

Definition 5:

local outlier factor of data point

. The local outlier factor of

is defined as Equation

10.

The contamination rate hyper-parameter determines the threshold based on the LOF of the training samples. During testing, data points with LOF values greater than the threshold are considered outliers.

4. Results

The entire setup was implemented using Python 3.8.17. The Periodicformer Encoder and the unsupervised representation learning process were developed with PyTorch 2.0.1 and PyTorch-Ignite 0.3.0, utilizing the Adam optimizer with a learning rate of 0.001 during back-propagation. The one-class classifier and its training process were implemented using scikit-learn. Experiments were conducted three times on a system equipped with an Intel i3-12100F CPU and an NVIDIA GeForce RTX 2060 12G GPU, and the average results are reported.

4.1. Dataset

The dataset utilized in this study for experimental evaluation is the publicly available electricity consumption dataset from the Irish CER Smart Metering Project [

21]. It includes daily electricity consumption records for approximately 5,000 residential and commercial users. Details of Irish dataset is shown in

Table 1.

For the experiments, we use data collected over a 365-day period. We exclude users with missing values (NaN), correct erroneous data, and apply min-max normalization to preprocess the dataset [

22]. To enhance detection performance, the detection window is set to cover 7 days (

) instead of a single day. The electricity consumption data from 5,000 residential users is split into training, validation, and test sets in a ratio of 8:1:1. The training set is treated as clean, normal data for model training. In the validation and test sets, 10% of the data is randomly selected and tempered using the attack models described in

Section 4.2. The validation set is utilized for hyper-parameter tuning, while the test set is reserved for evaluating the model’s anomaly detection performance.

4.2. Attack Model

False data injection is a type of cyber attack in which manipulated or false information is deliberately introduced into a system to mislead its operations or decision-making processes. It is commonly employed to compromise the integrity of data in power systems, sensor networks, and other critical infrastructures.

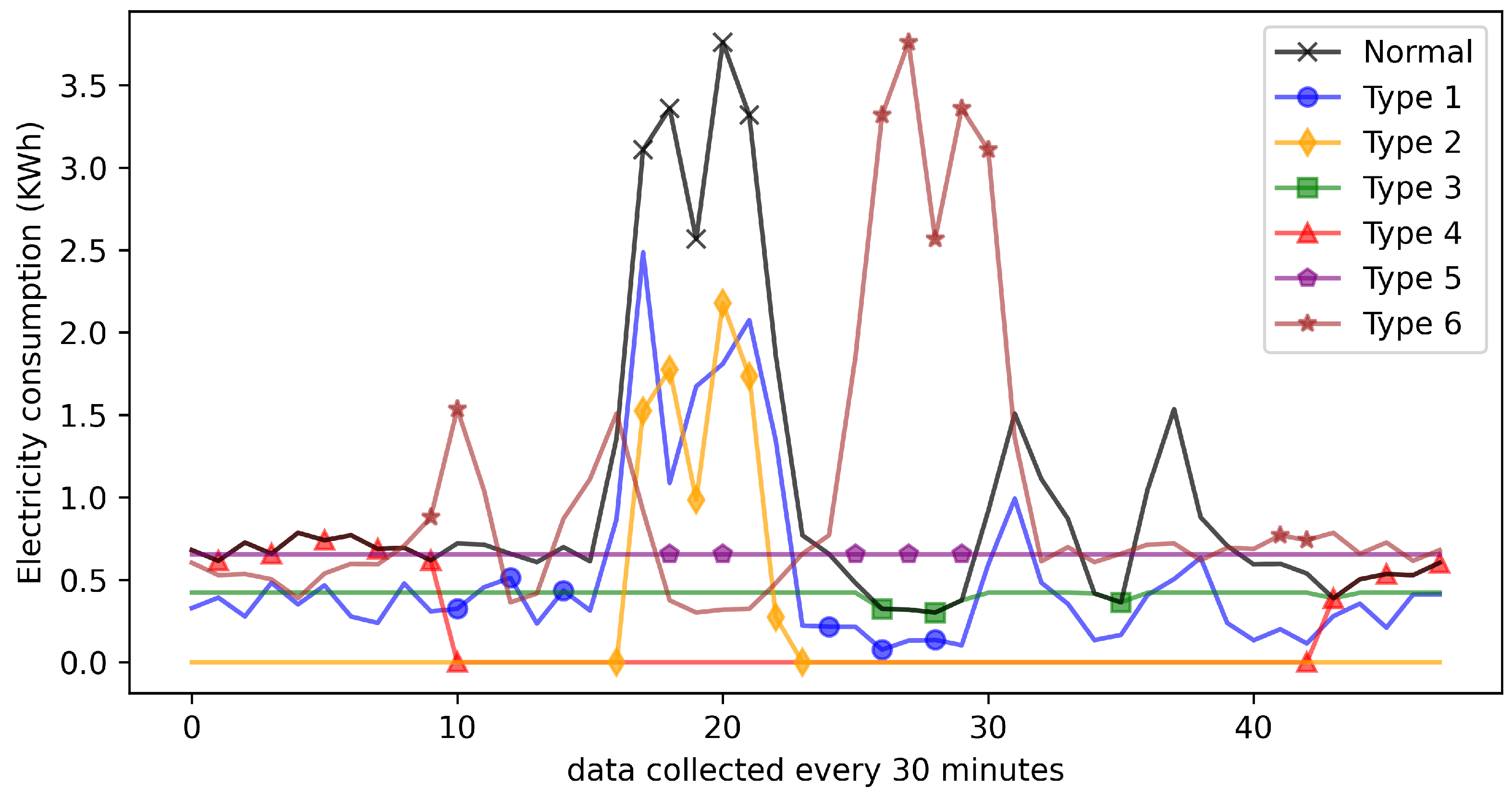

In this study, to simulate various electricity theft patterns, six different false data injection attacks are implemented, as shown in

Table 2. These attacks are broadly categorized into two types: reduced consumption attacks and load profile shifting attacks [

1]. Types 1–4 primarily reduce the electricity consumption recorded by the meter, while Types 5 and 6 shift electricity usage from high-price periods to low-price periods.

The physical interpretations of these six attacks are as follows: FDI1: Electricity consumption recorded at each time point is scaled down by a randomly selected proportion. FDI2: A constant value is subtracted from the electricity consumption data. FDI3: Electricity consumption values exceeding a preset threshold are capped at the threshold value. FDI4: Consumption data within a randomly selected time interval during the day is replaced with zeros. FDI5: The total daily electricity consumption is evenly distributed across all recording points and reduced by a fixed proportion. FDI6: The entire daily electricity consumption profile is inverted. Additionally,

Figure 4 illustrates examples of both normal electricity consumption data and data affected by each of these six attack types.

4.3. Evaluation Metrics

The confusion matrix quantifies all classification outcomes of a model, providing an intuitive representation of classification accuracy. In this paper, electricity theft samples are considered as the positive class, while normal electricity usage samples are treated as the negative class. The definitions of true positive (TP), false positive (FP), false negative (FN), and true negative (TN) are summarized in

Table 3.

Based on the above confusion matrix, we use the F1 score (F1), the area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve (AUC), Recall, and false positive rate (FPR) to evaluate the performance of the proposed electricity theft detection framework.

Recall, also known as true positive rate (TPR), evaluates a model’s effectiveness in identifying all actual positive instances within a dataset, highlighting its sensitivity to true positives. It is calculated as follows.

FPR quantifies the rate at which negative samples are misclassified as positive, reflecting the model’s tendency for false alarms. It is computed as follows.

In anomaly detection, we generally aim for a model that has a low FPR while maintaining a high TPR.

Precision quantifies the accuracy of positive predictions, calculated as follows.

F1 captures the trade-off between Precision and Recall, offering a single metric to evaluate performance, particularly in scenarios with imbalanced data. It is calculated as follows.

AUC evaluates a model’s capability to differentiate between classes over varying decision thresholds, with larger values reflecting stronger discriminative power.

4.4. Analysis of Model Hyper-Parameters

We applied grid search on the validation set to identify the optimal hyper-parameters. The selection ranges for each parameter and the corresponding best results are presented in

Table 4.

For the Periodicformer encoder, the hyper-parameters primarily consist of three components: the number of heads

H, the encoder embedding dimension

d and the number of layers

N. The best result

H,

d and

N in this paper is consistent with that in Reference [

23]. As for the patch size for each layer

, this paper empirically concludes that the patch size should initially be larger and then gradually decrease. For LOF, we explore three values of number of neighbors

k, and test three different values for the contamination rate parameters to control the expected proportion or number of anomaly points. Additionally, we experiment two different distance metrics. The best combination of parameters was selected based on performance.

4.5. Comparison with Other Methods

In this part, we compare the the proposed method with six one-class classification-based ETD methods. We implement all these methods on the preprocessed data for fair comparison.

OCSVM [

24]: OCSVM is a support vector machine-based algorithm designed for anomaly detection. It distinguishes normal samples from anomalies by maximizing the margin between the data and the origin in the feature space. We set the kernel function,

parameters as ’linear’ and 0.2 respectively;

iForest [

25]: iForest is an efficient unsupervised anomaly detection method leveraging random forests. It isolates anomalies by exploiting their tendency to be easier to separate from the majority of the data through random partitioning. We set the contamination, maxFeatures and nEstim parameters as 0.1, 0.6 and 300 respectively;

LOF [

26]: LOF is a density-based anomaly detection algorithm. It detects outliers by comparing the local density of a sample with the densities of its neighbors, identifying anomalies as points with significantly lower densities. We set the contamination rate as 0.1 while keeping other parameters as default;

Autoencoder with one-class (OC) classifier [

27]: Reference [

27] incorporates the concept of autoencoding and OC classification. We implement this method using CNN-AE(1D) as the autoencoder along with three OC classifiers.

Table 5 presents the comparison results between our proposed method and six baseline methods, and following findings can be observed.

Overall, the combination of the Periodicformer encoder and LOF achieved the best performance, with F1, AUC, Recall, and FPR scores of 0.833, 0.973, 0.877, and 0.025, respectively. Compared to the second-best approach, the combination of Autoencoder and LOF (F1, AUC, Recall, and FPR scores of 0.814, 0.952, 0.856, and 0.027, respectively), it achieved improvements of 2.3%, 1.7%, 2.4%, and 8% in F1, AUC, Recall, and FPR, respectively;

The three approaches that rely solely on the OC classifier exhibit relatively poor anomaly detection performance, with some even failing (defined as AUC or Recall values below 0.5). This observation aligns with the findings reported in Reference [

27]. This suggests that the one-class classifier fails to effectively capture the distribution of normal samples in the training dataset, making it difficult to distinguish between normal and anomalous samples in the test set. This underscores the importance of designing a robust unsupervised representation learning method to extract meaningful features, aiding the one-class classifier in better modeling the distribution of normal samples and improving anomaly detection performance;

Comparing the proposed combination of the Periodicformer encoder and OC classifier with the combination of Autoencoder and OC classifier, specifically the combination of Periodicformer encoder and LOF versus Autoencoder and LOF, the Periodicformer encoder demonstrates superior suitability for modeling time series data. Additionally, our proposed criss-cross periodic attention further enhances the model’s ability to capture richer periodic features, which helps distinguish normal data from anomalous data. In contrast, the Autoencoder relies solely on CNN to capture local features without considering the periodicity of time series data, resulting in poorer performance;

In the three combinations of the Periodicformer encoder with different OC classifiers, the scheme combined with iForest yields the poorest performance. According to Reference [

28], iForest is sensitive only to global outliers and struggles with detecting local outliers. The distribution of power theft behavior data is particularly unfavorable for iForest detection. For instance, when considering an entire year (365 days), power theft typically occurs on specific days or weeks. These anomalies may not be noticeable when viewed in the context of the whole year. However, when compared to adjacent days or weeks, these outliers may become more apparent. This is precisely where iForest’s limitations lie. Regarding the combination with OCSVM, Reference [

29] states that OCSVM is sensitive to noise and prone to false positives, which aligns with our experimental findings. Although it achieves a high recall, it also results in a relatively high false positive rate.

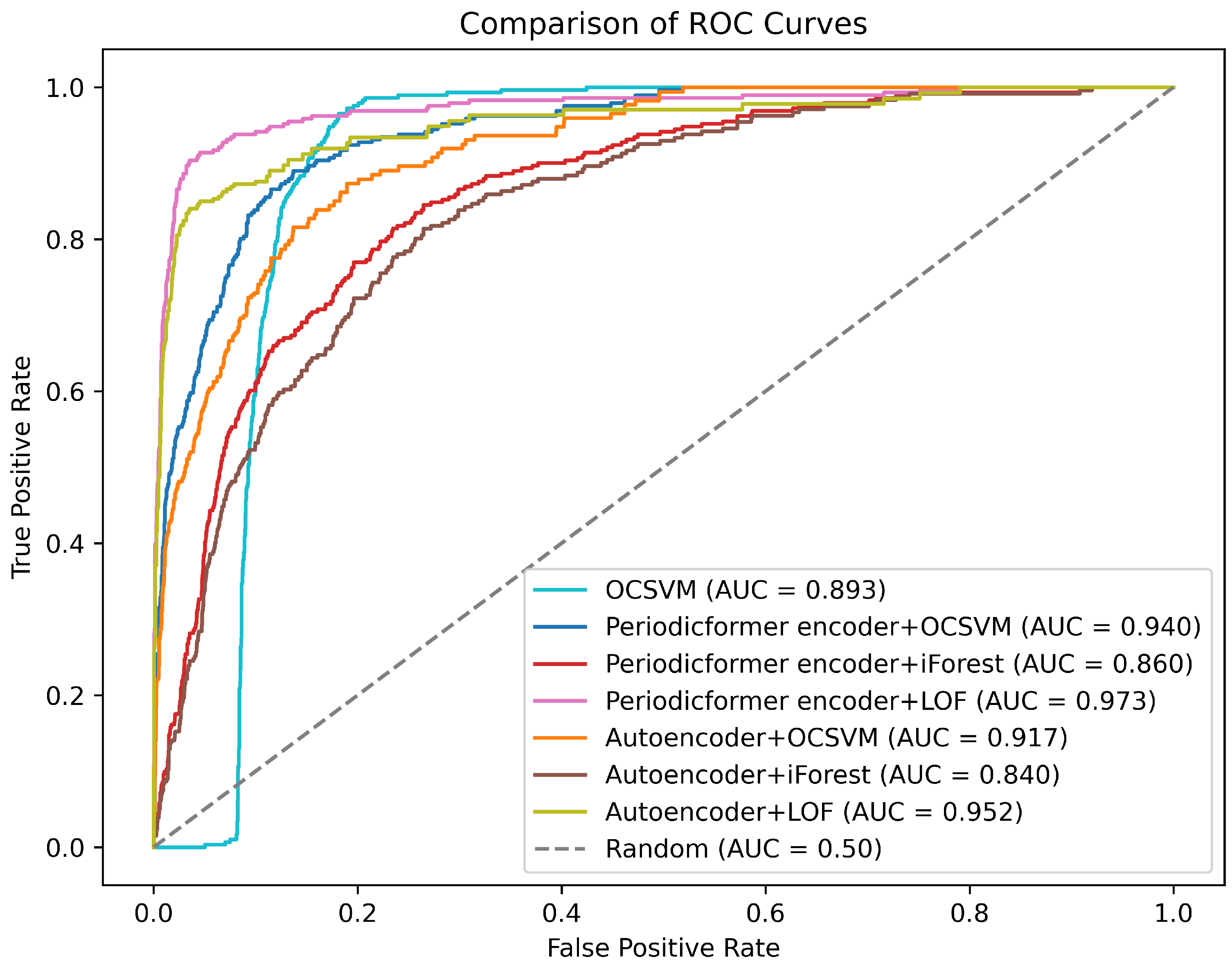

For anomaly detection tasks, our goal is to develop a model that achieves a low false positive rate (FPR) while maintaining a high true positive rate (TPR). To showcase the performance of all the methods in this regard, we have plotted the ROC curve, as shown in

Figure 5. The proposed combination of the Periodicformer encoder and LOF achieves the highest TPR at the lowest FPR, and the combination of Autoencoder and iForest yields the poorest performance.

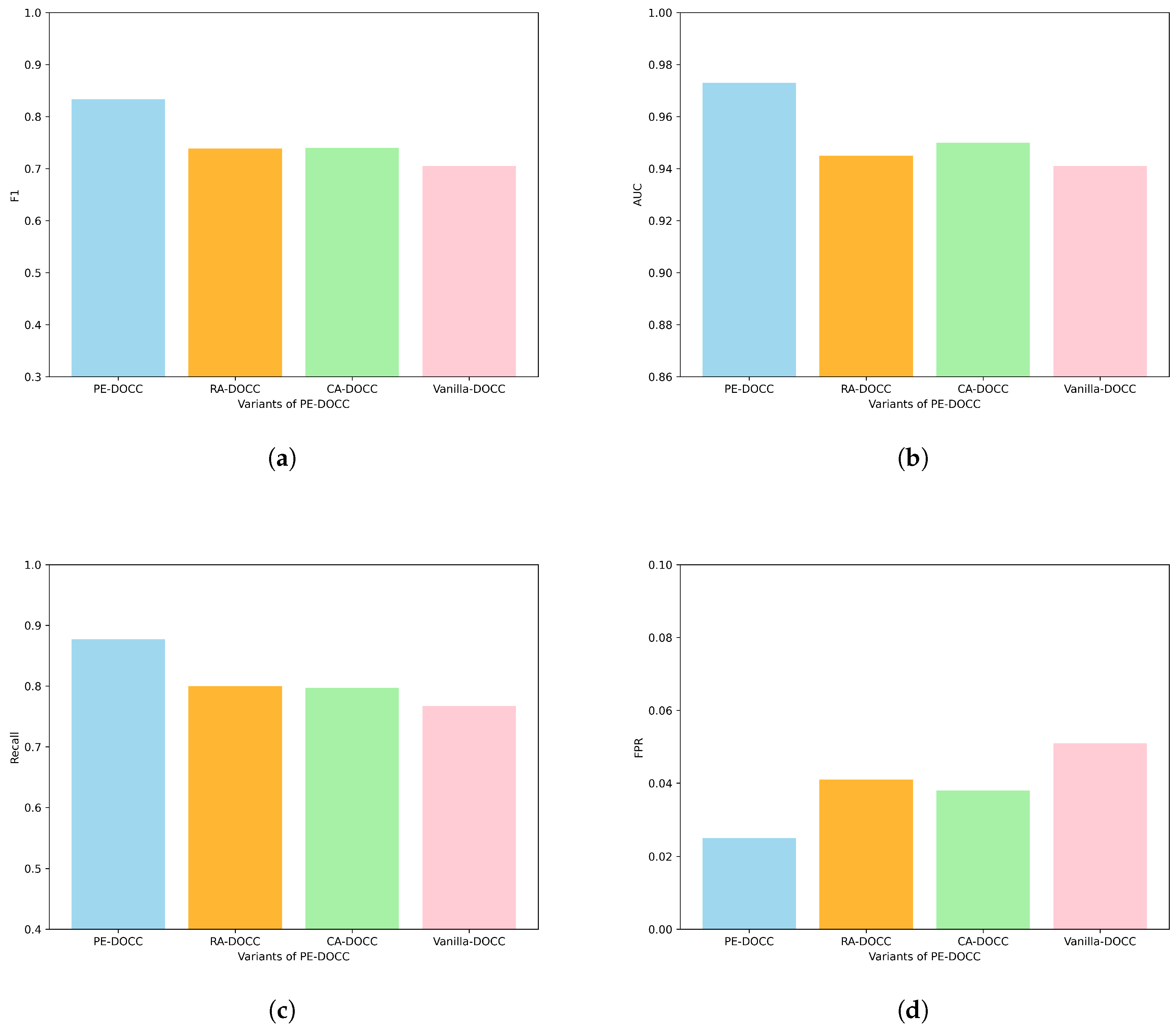

4.6. Ablation Analysis

An ablation study is conducted to demonstrate the impact of the main components in the proposed framework on the ETD performance. Specifically, three variants of our proposed method are implemented.

RA-DOCC: This method uses a combination of a Periodicformer encoder with only row auto-correlation and LOF;

CA-DOCC: This method uses a combination of a Periodicformer encoder with only column auto-correlation and LOF;

Vanilla-DOCC: This method uses a combination of a vanilla Transfomer encoder [

30] and LOF.

Figure 6 shows the results of the ablation experiments, from which the following findings can be drawn:

RA-DOCC and CA-DOCC produce comparable experimental results, but show notable improvements over Vanilla-DOCC. Specifically, F1, AUC, Recall, and FPR improve by approximately 5%, 1%, 4%, and 34%, respectively. This suggests that row auto-correlation and column auto-correlation are all effective in capturing periodic features, which help the model distinguish anomalous samples;

Our proposed Criss-cross periodic attention effectively integrates multiple periodic features. Compared to the vanilla Transformer encoder, F1, AUC, Recall, and FPR have improved by 15.3%, 3.2%, 12.5%, and 104%, respectively.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

This paper proposes a novel periodicity-enhanced deep one-class classification framework for electricity theft detection, named PE-DOCC. Overall, the training samples first undergo unsupervised representation learning (i.e., pre-train the Periodicformer encoder). Then, the training samples are passed through the pretrained encoder to obtain latent representations, which are finally fed into a one-class classifier. During testing, the trained Periodicformer encoder and classifier are used to determine whether the testing latent representation falls within the trained boundary. To enhance the model’s ability to capture periodic features and improve its capacity to distinguish anomalous samples from normal ones, the paper introduces a criss-cross periodic attention mechanism that comprehensively considers both horizontal and vertical periodic features. Experiments are conducted on a real-world electricity consumption dataset, and the results show that the proposed ETD framework can effectively detect anomalous electricity behaviors and outperforms state-of-the-art ETD methods. In future work, we will explore how to use Graph Neural Networks (GNN) to uncover the relationships between different variables in multivariate datasets to further improve model performance.

References

- Xia, X.; Xiao, Y.; Liang, W.; Cui, J. Detection Methods in Smart Meters for Electricity Thefts: A Survey. Proceedings of the IEEE 2022, 110, 273–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Z.; Wen, H. Performance Analysis of Electricity Theft Detection for the Smart Grid: An Overview. IEEE Transactions on Instrumentation and Measurement 2022, 71, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stracqualursi, E.; Rosato, A.; Di Lorenzo, G.; Panella, M.; Araneo, R. Systematic review of energy theft practices and autonomous detection through artificial intelligence methods. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2023, 184, 113544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, X.; Lin, J.; Jia, Q.; Wang, X.; Ma, C.; Cui, J.; Liang, W. ETD-ConvLSTM: A Deep Learning Approach for Electricity Theft Detection in Smart Grids. IEEE Transactions on Information Forensics and Security 2023, 18, 2553–2568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, L.; Liu, Y.; Li, G.; Mao, M.; Lin, L. Hybrid-Order Representation Learning for Electricity Theft Detection. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Informatics 2023, 19, 1248–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, W.; Yang, Z.; Liu, K.; Zhang, B.; Chen, X.; Song, R. Electricity Theft Detection Using Euclidean and Graph Convolutional Neural Networks. IEEE Transactions on Power Systems 2023, 38, 3514–3527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takiddin, A.; Ismail, M.; Zafar, U.; Serpedin, E. Deep Autoencoder-Based Anomaly Detection of Electricity Theft Cyberattacks in Smart Grids. IEEE Systems Journal 2022, 16, 4106–4117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Q.; Zhao, S.; Zhang, J.; Deng, H. Unsupervised BLSTM-Based Electricity Theft Detection with Training Data Contaminated. ACM Trans. Cyber-Phys. Syst. 2024, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Xu, Q. Electricity theft detection based on stacked sparse denoising autoencoder. International Journal of Electrical Power & Energy Systems 2021, 125, 106448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Q.; Li, P.; Wang, R. Electricity theft detection based on hybrid random forest and weighted support vector data description. International Journal of Electrical Power & Energy Systems 2023, 153, 109283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senol, N.S.; Baza, M.; Rasheed, A.; Alsabaan, M. Privacy-Preserving Detection of Tampered Radio-Frequency Transmissions Utilizing Federated Learning in LoRa Networks. Sensors 2024, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yi, X.; Yang, X.; Huang, Y.; Ke, S.; Zhang, J.; Li, T.; Zheng, Y. Gas-Theft Suspect Detection Among Boiler Room Users: A Data-Driven Approach. IEEE Transactions on Knowledge and Data Engineering 2022, 34, 5796–5808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbariol, T.; Susto, G.A. TiWS-iForest: Isolation forest in weakly supervised and tiny ML scenarios. Information Sciences 2022, 610, 126–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tirulo, A.; Chauhan, S.; Issac, B. Ensemble LOF-based detection of false data injection in smart grid demand response system. Computers and Electrical Engineering 2024, 116, 109188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, D.; Wang, J.; Gao, X.; Wang, J.; Zhao, X.; Wang, L. Self-supervised Pretraining Isolated Forest for Outlier Detection. In Proceedings of the 2022 International Conference on Big Data, Information and Computer Network (BDICN); 2022; pp. 306–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.; Chang, S.Y.; Kim, J.; Lee, D.; Kim, J. Automated, Reliable Zero-Day Malware Detection Based on Autoencoding Architecture. IEEE Transactions on Network and Service Management 2023, 20, 3900–3914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, X.; Liu, S.; Lin, Z.; Ma, J.; Wen, F.; Ding, Y.; Yang, L.; Guo, W.; Feng, X. Two-Step Electricity Theft Detection Strategy Considering Economic Return Based on Convolutional Autoencoder and Improved Regression Algorithm. IEEE Transactions on Power Systems 2022, 37, 2346–2359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, A.; Chen, M.; Zhang, L.; Xu, Q. Are transformers effective for time series forecasting? In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the AAAI conference on artificial intelligence, 2023, Vol. 37, pp. 11121–11128.

- Wu, H.; Xu, J.; Wang, J.; Long, M. Autoformer: Decomposition Transformers with Auto-Correlation for Long-Term Series Forecasting. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; Ranzato, M.; Beygelzimer, A.; Dauphin, Y.; Liang, P.; Vaughan, J.W., Eds. Curran Associates, Inc., 2021, Vol. 34, pp. 22419–22430.

- Tuli, S.; Casale, G.; Jennings, N.R. TranAD: deep transformer networks for anomaly detection in multivariate time series data. Proc. VLDB Endow. 2022, 15, 1201–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- for Energy Regulation (CER), C. CER smart metering project-electricity customer behaviour trial, 2009-2010, 2012.

- Qi, R.; Zheng, J.; Luo, Z.; Li, Q. A Novel Unsupervised Data-Driven Method for Electricity Theft Detection in AMI Using Observer Meters. IEEE Transactions on Instrumentation and Measurement 2022, 71, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zerveas, G.; Jayaraman, S.; Patel, D.; Bhamidipaty, A.; Eickhoff, C. A Transformer-based Framework for Multivariate Time Series Representation Learning. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 27th ACM SIGKDD Conference on Knowledge Discovery & Data Mining, New York, NY, USA, 2021; KDD ’21, p. 2114–2124. [CrossRef]

- Schölkopf, B.; Platt, J.C.; Shawe-Taylor, J.; Smola, A.J.; Williamson, R.C. Estimating the support of a high-dimensional distribution. Neural computation 2001, 13, 1443–1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.T.; Ting, K.M.; Zhou, Z.H. Isolation Forest. In Proceedings of the 2008 Eighth IEEE International Conference on Data Mining, 2008, pp. 413–422. [CrossRef]

- Breunig, M.M.; Kriegel, H.P.; Ng, R.T.; Sander, J. LOF: identifying density-based local outliers. SIGMOD Rec. 2000, 29, 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.; Chang, S.Y.; Kim, J.; Lee, D.; Kim, J. Automated, Reliable Zero-Day Malware Detection Based on Autoencoding Architecture. IEEE Transactions on Network and Service Management 2023, 20, 3900–3914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Z.; Zou, C.; Dong, J. Outlier detection using isolation forest and local outlier factor. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the Conference on Research in Adaptive and Convergent Systems, New York, NY, USA, 2019; RACS ’19, p. 161–168. [CrossRef]

- Lu, T.; Wang, L.; Zhao, X. Review of Anomaly Detection Algorithms for Data Streams. Applied Sciences 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, L.u.; Polosukhin, I. Attention is All you Need. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; Guyon, I.; Luxburg, U.V.; Bengio, S.; Wallach, H.; Fergus, R.; Vishwanathan, S.; Garnett, R., Eds. Curran Associates, Inc., 2017, Vol. 30.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).