Submitted:

26 January 2025

Posted:

26 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Adjusting freezing patterns is a critical technology in artificial ground freezing (AGF) projects to mitigate frost heave. The distribution of ice lenses formed under varying freezing patterns not only influences frost heave but also modifies the structure of thawed soil, thereby affecting the thaw settlement process. However, most existing research on freezing patterns has primarily focused on their impact on frost heave, with limited attention paid to thaw settlement. This study investigates the cooling rates at the cold side of open frozen systems, which are the key variables defining different freezing patterns, and examines their effect on the permeability coefficient of thawed soil. Experimental results demonstrate that the cooling rate significantly influences the soil permeability coefficient. Specifically, an increase in the cooling rate leads to a reduction in the permeability coefficient, particularly under high frozen temperature conditions. Utilizing the Kozeny-Carman permeability coefficient equation, a predictive model for the permeability coefficient of thawed soil was developed. In practical AGF projects, any freezing pattern can be represented as a combination of different cooling rates. By applying this predictive model, the permeability coefficient of thawed soil under any freezing pattern can be simulated using the corresponding combination of cooling rates. This study provides a valuable reference for predicting thaw settlement following artificial freezing construction.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Test Apparatus

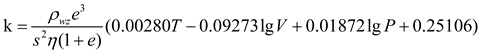

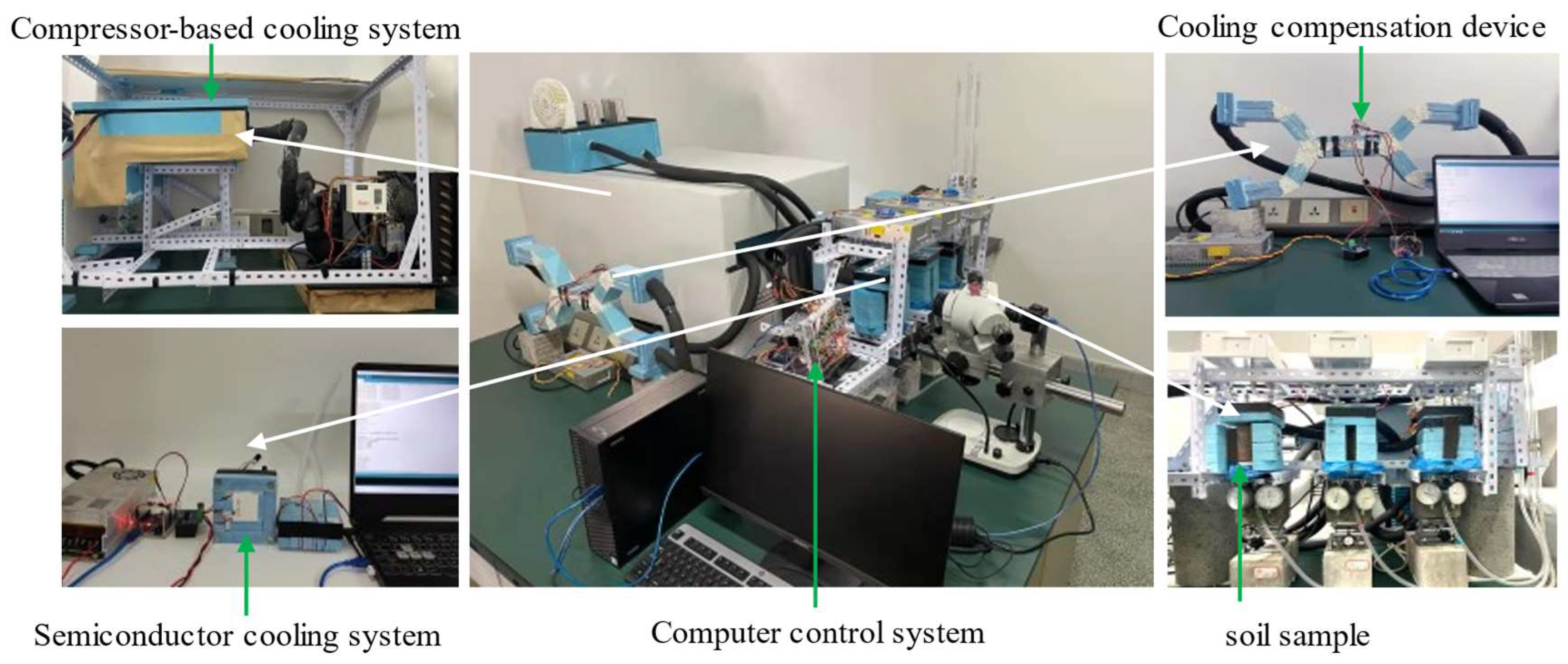

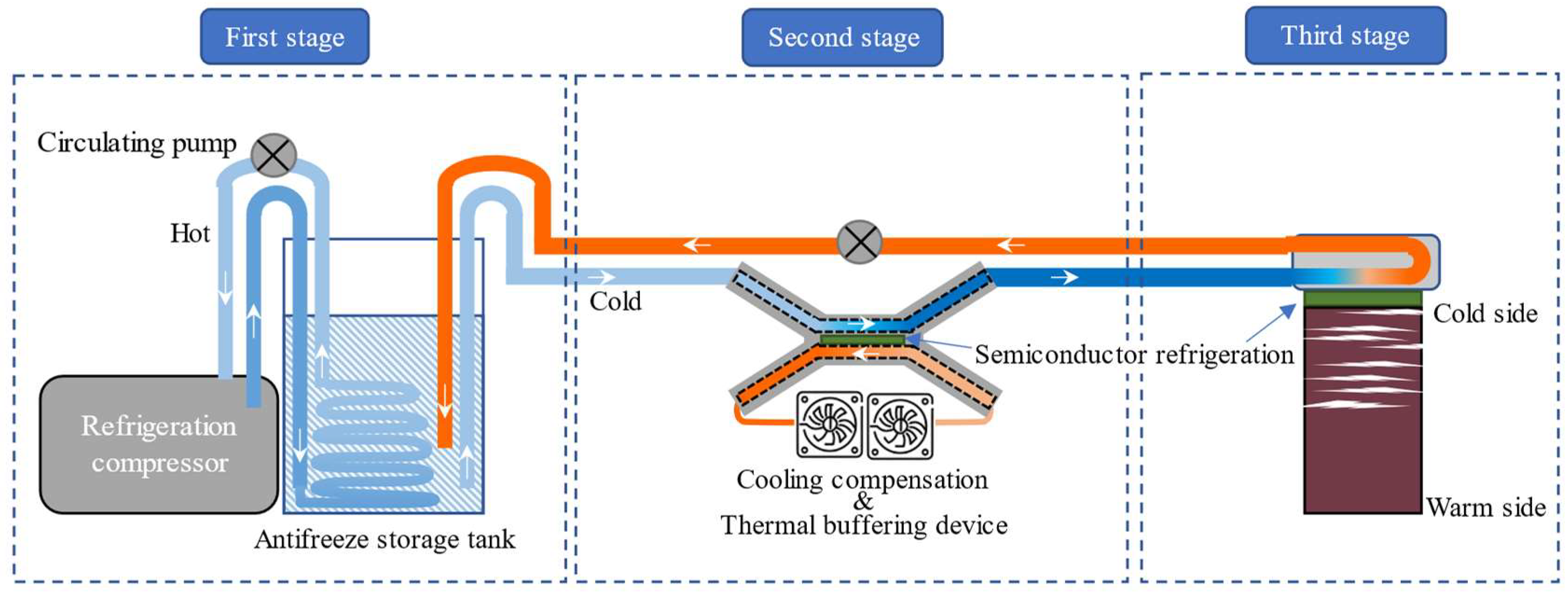

2.1. The Semiconductor-Based Open Frozen System (SOF)

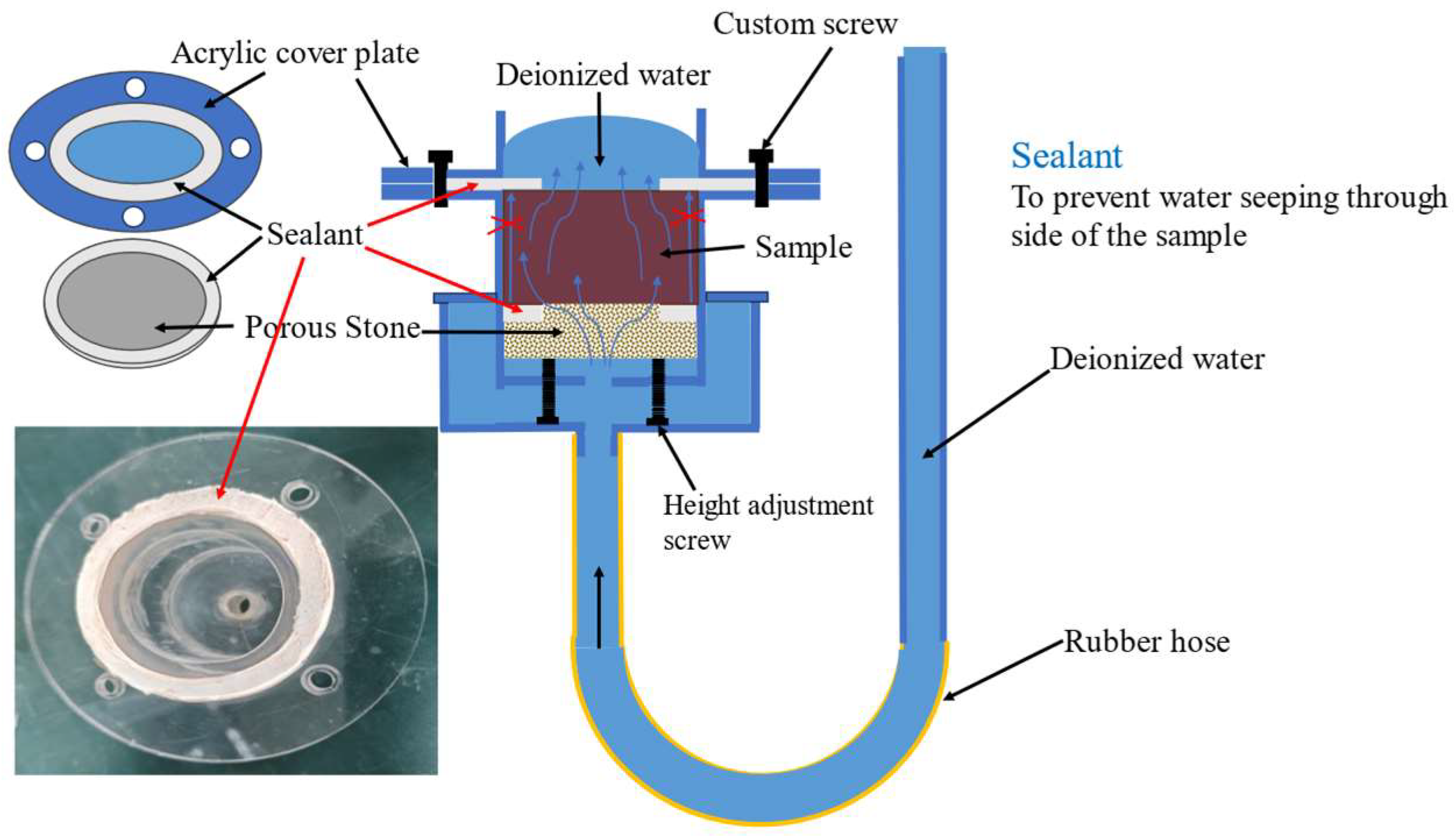

2.2. Independently Developed Variable-Head Permeameter

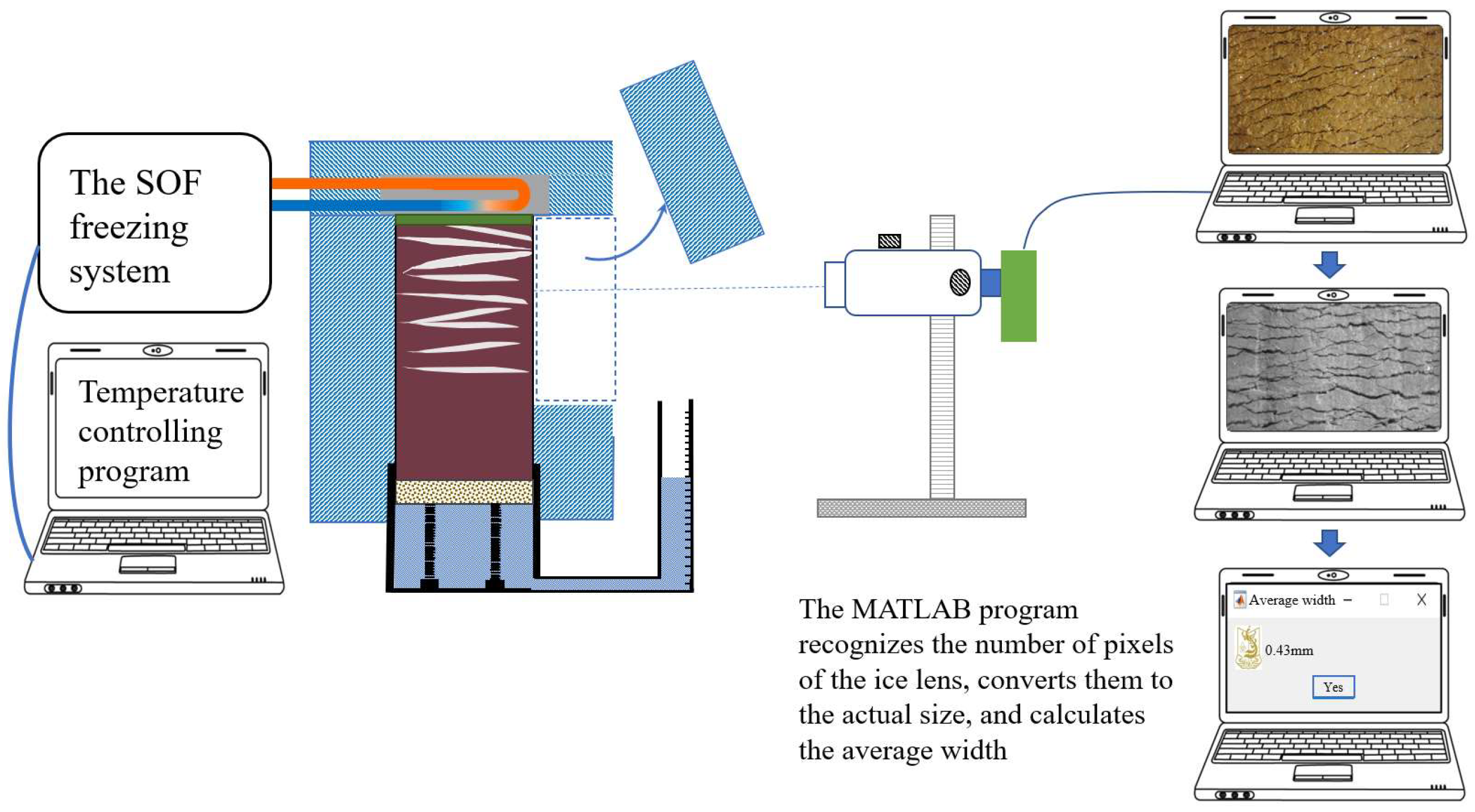

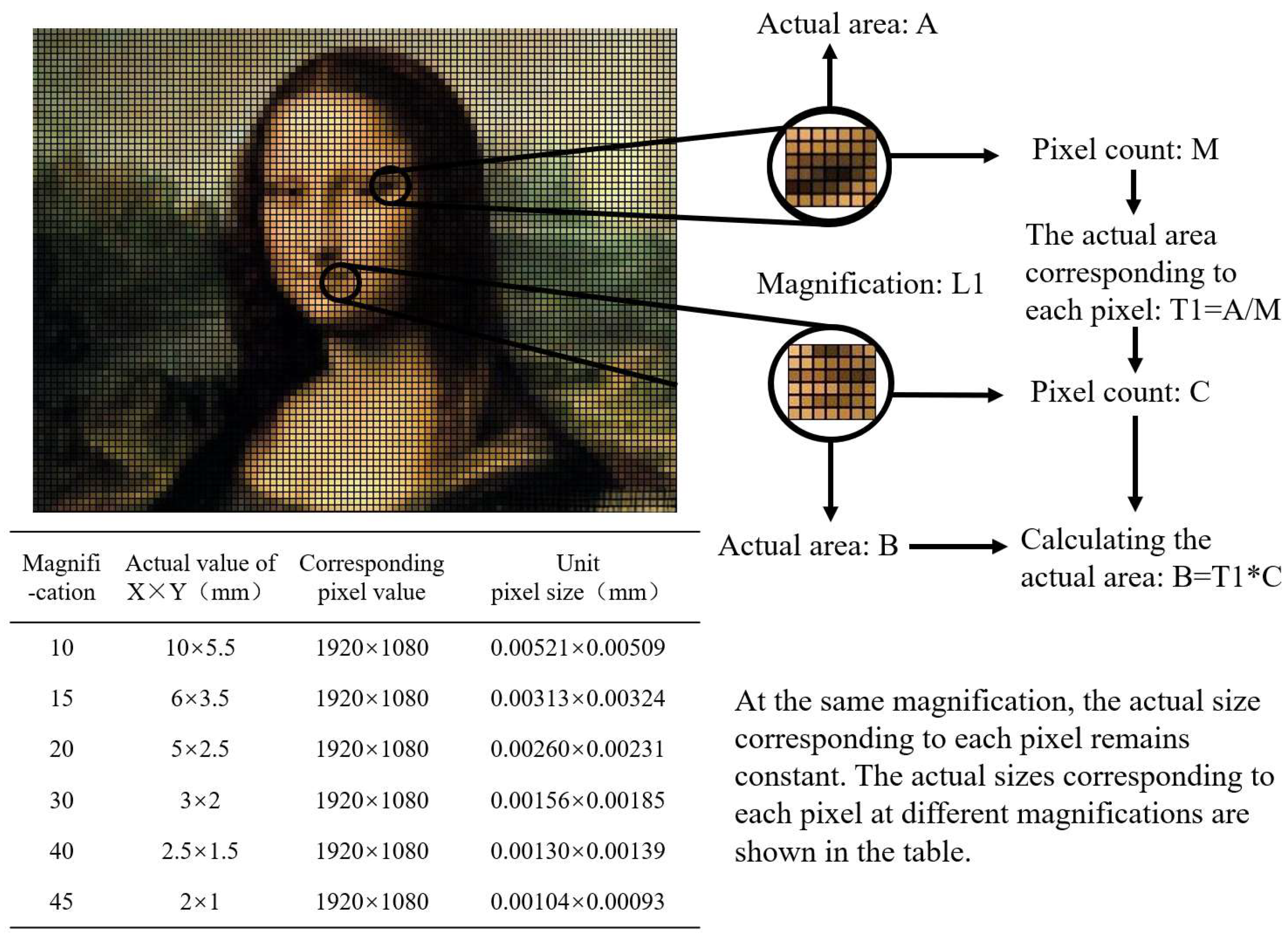

2.3. Microscopy-Based Ice Lens Measure System (MIL)

3. Experimental Scheme

3.1. Experimental Design

3.2. Experimental Procedure

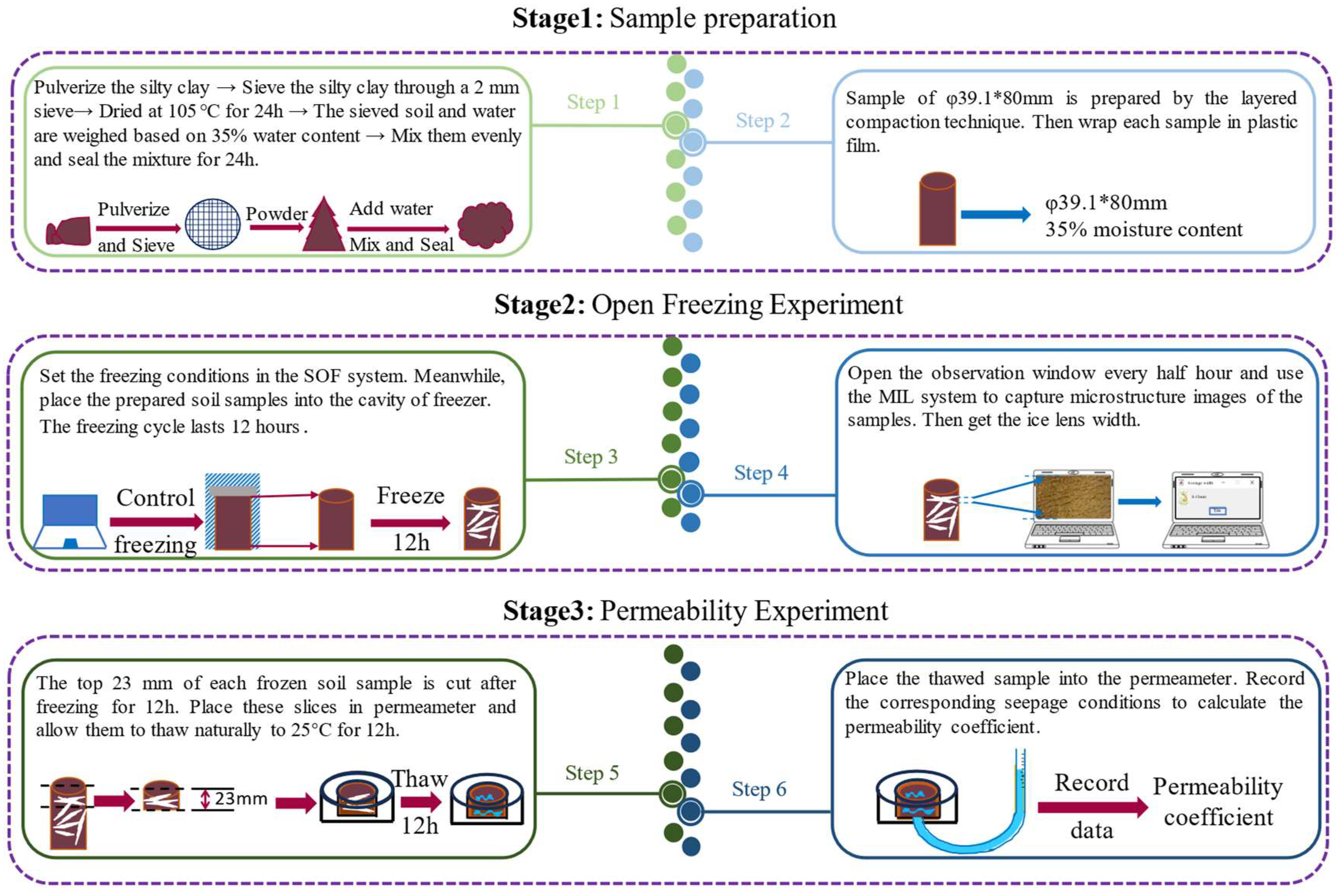

3.2.1. Sample Preparation

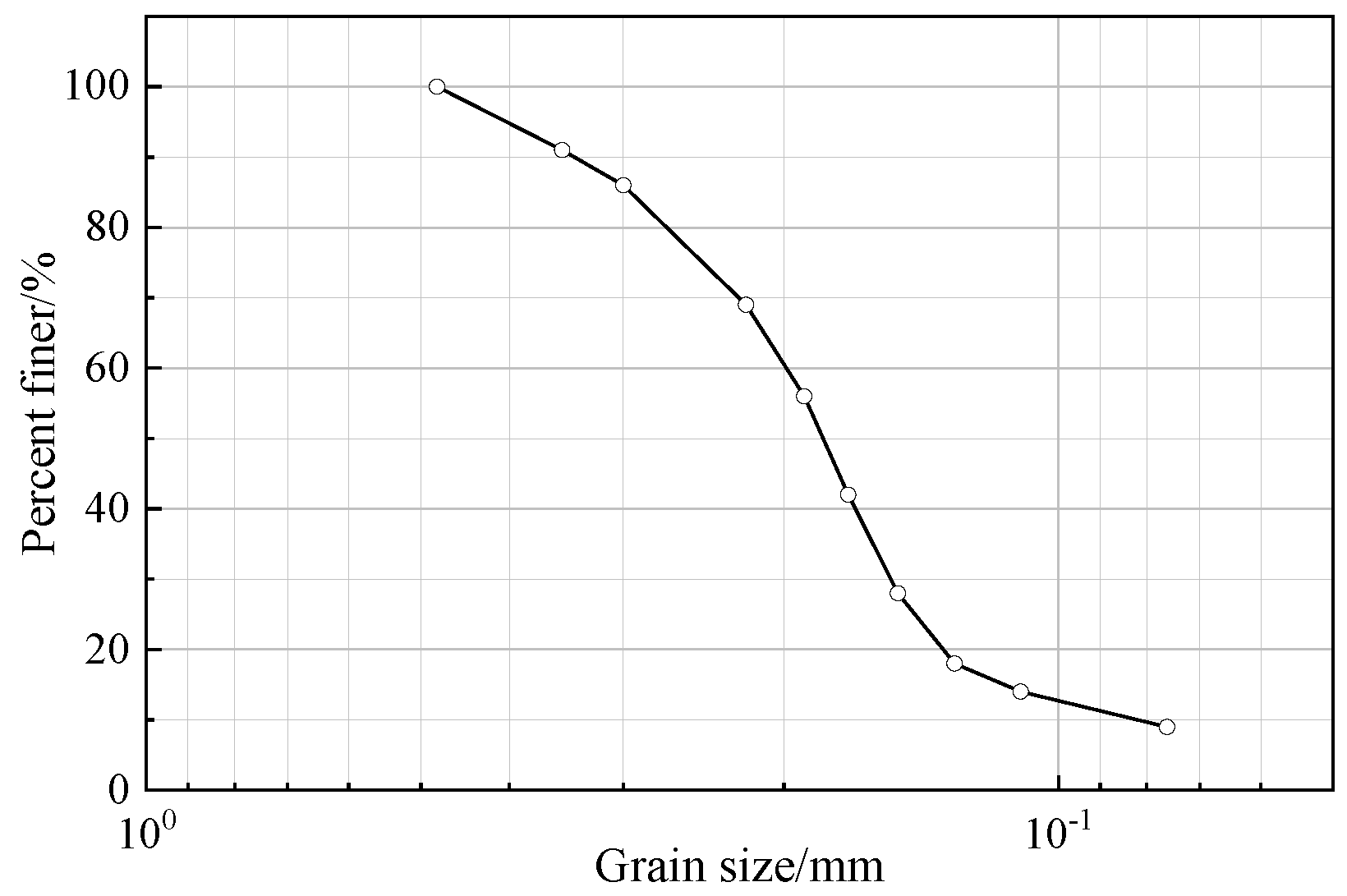

- Soil Preparation: The soil is initially crushed to break down large clumps, then sieved through a 2mm screen to remove larger particles and debris. The sieved soil is subsequently dried in an oven at 105°C for 24 hours to eliminate excess moisture, ensuring a consistent starting condition for the experiment.

- Water Content Adjustment and Homogenization: To achieve uniform water content across all samples, a specific amount of water is added to the dried soil to reach a target water content of 35%. The mixture is then thoroughly mixed using a mechanical mixer to ensure homogeneity. Afterward, the mixed soil sample is sealed in airtight containers and stored for 24 hours to allow the water to evenly distribute throughout the soil matrix.

- Sample Preparation: The layered compaction technique is used to prepare cylindrical specimens with a diameter of 39.1 mm and a height of 80 mm. Each specimen is immediately wrapped in plastic film to protect it from environmental factors during handling.

3.2.2. Open Freezing Experiment

- Equipment Setup: Set the required frozen temperature and cooling rate in the SOF system.

- Sample Placement and Experiment Start: Carefully place the prepared soil samples into the freezer cavity and set the appropriate water replenishment pressure. Initiate the freezing process.

- Monitoring and Recording: Throughout the experiment, the observation window of the cavity is briefly opened every half hour for approximately 5 seconds. During this time, the MIL system is used to capture microstructural images of the samples, enabling real-time monitoring of changes within the soil’s microstructure. The entire freezing cycle lasts 12 hours, generating a comprehensive dataset for analysis.

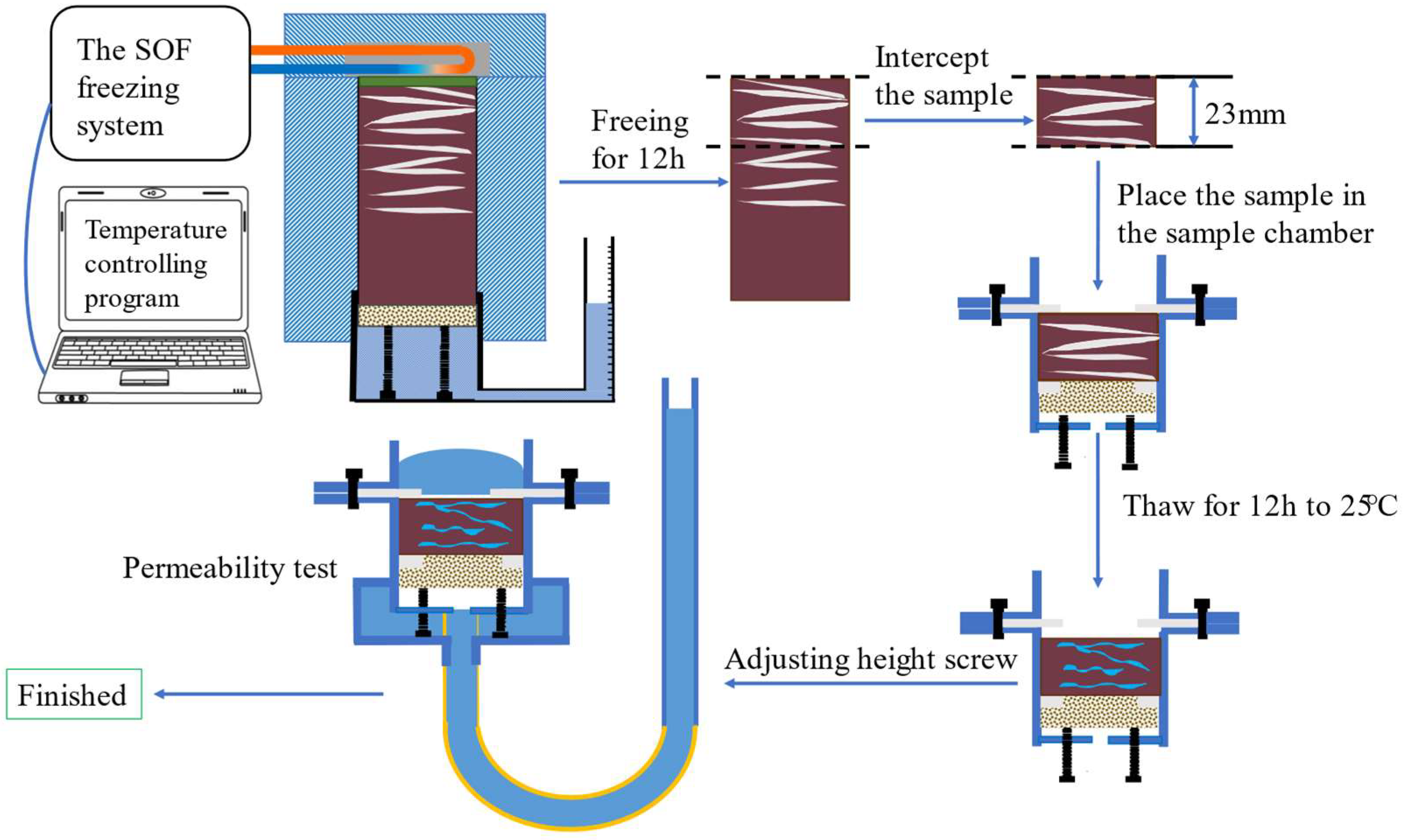

3.2.3. Permeability Experiment

- Preparation: After the freezing stage, the top 23 mm of each frozen soil sample is precisely cut using a wire saw to obtain test samples.

- Instrument Setup: Place these slices into the variable-head permeameter and allow them to thaw naturally at room temperature (25°C). It should be noted that volume changes during the melting process may occur, potentially separating the sample from the top sealant.

- Adjustment and Measurement: Adjust the height adjustment screws to ensure that the thawed soil is in close contact with the top sealant ring. Vary the water pressure and record the corresponding seepage conditions to calculate the permeability coefficient.

4. Results and Discussions

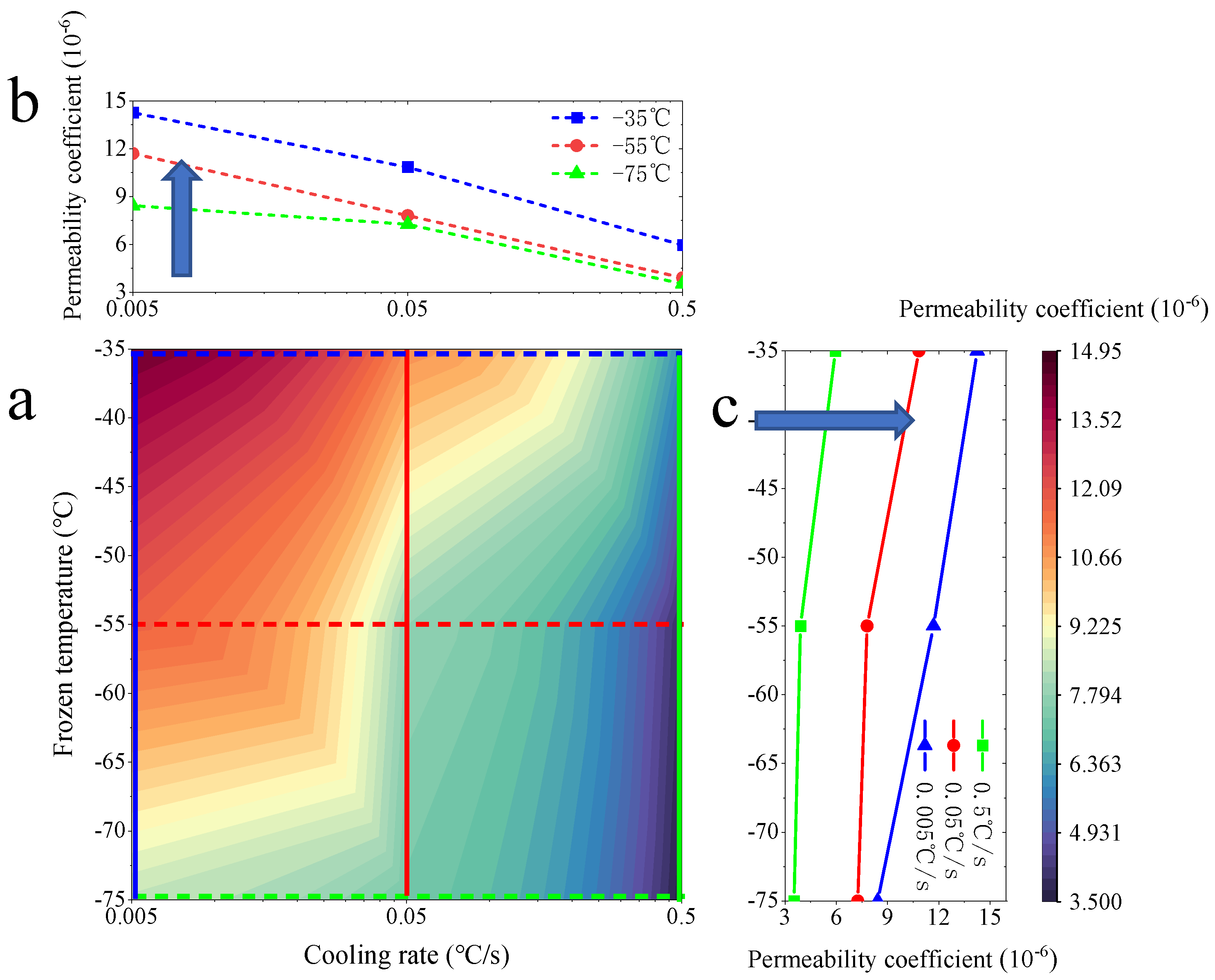

4.1. Experimental Results of Permeability Coefficient

4.2. The Influence of Cooling Rate and Temperature Gradient on the Permeability

5. Micro-Mechanism of the Evolution of Permeability Coefficient

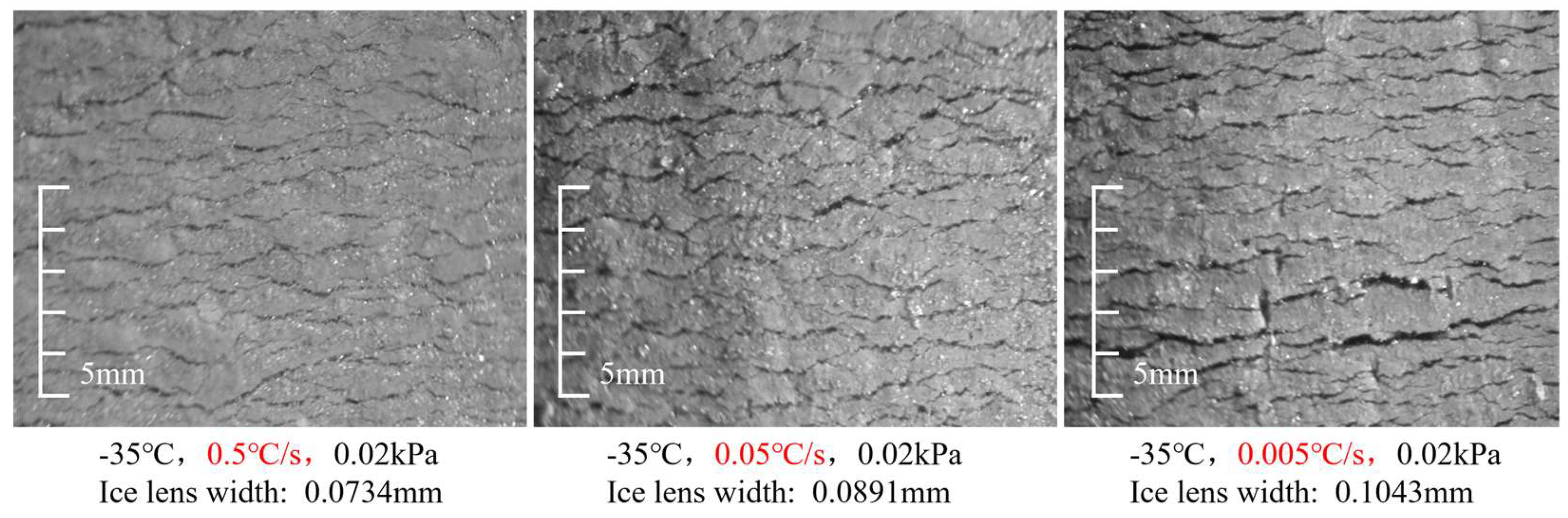

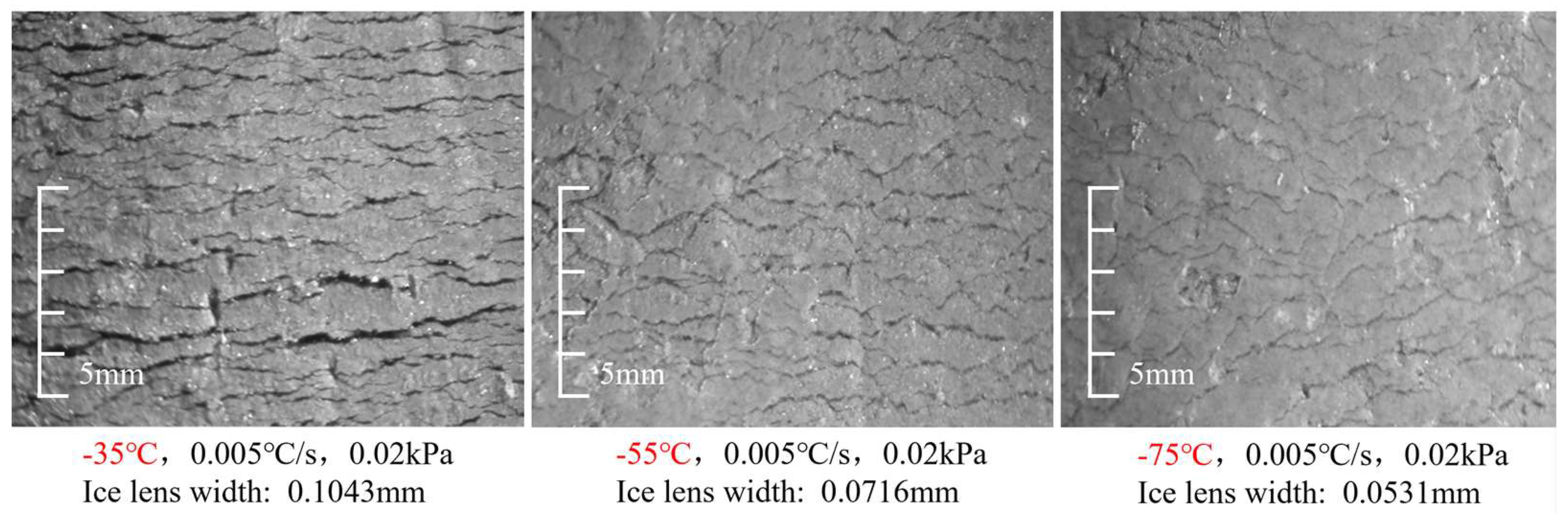

5.1. The Effect of Cooling Rate

5.2. The Effect of Temperature Gradient

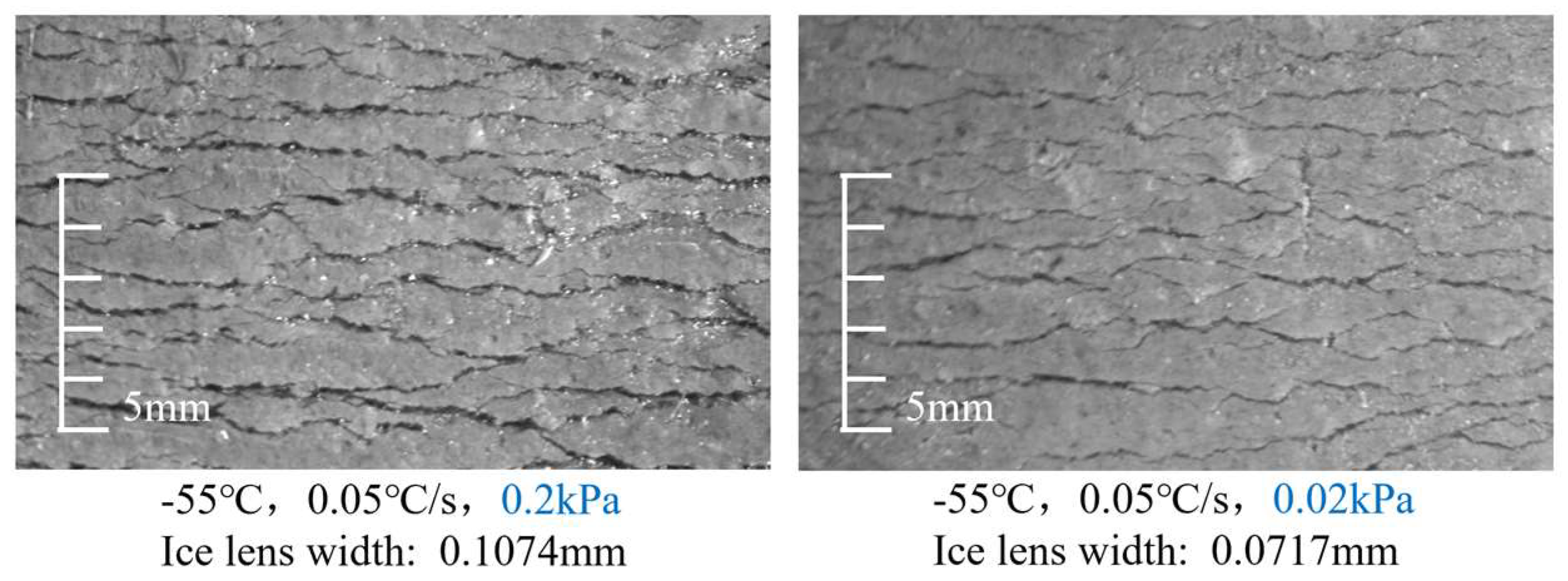

5.3. The Effect of Water Replenishment Pressure

6. Permeability Coefficient Prediction Model

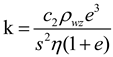

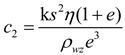

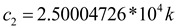

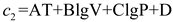

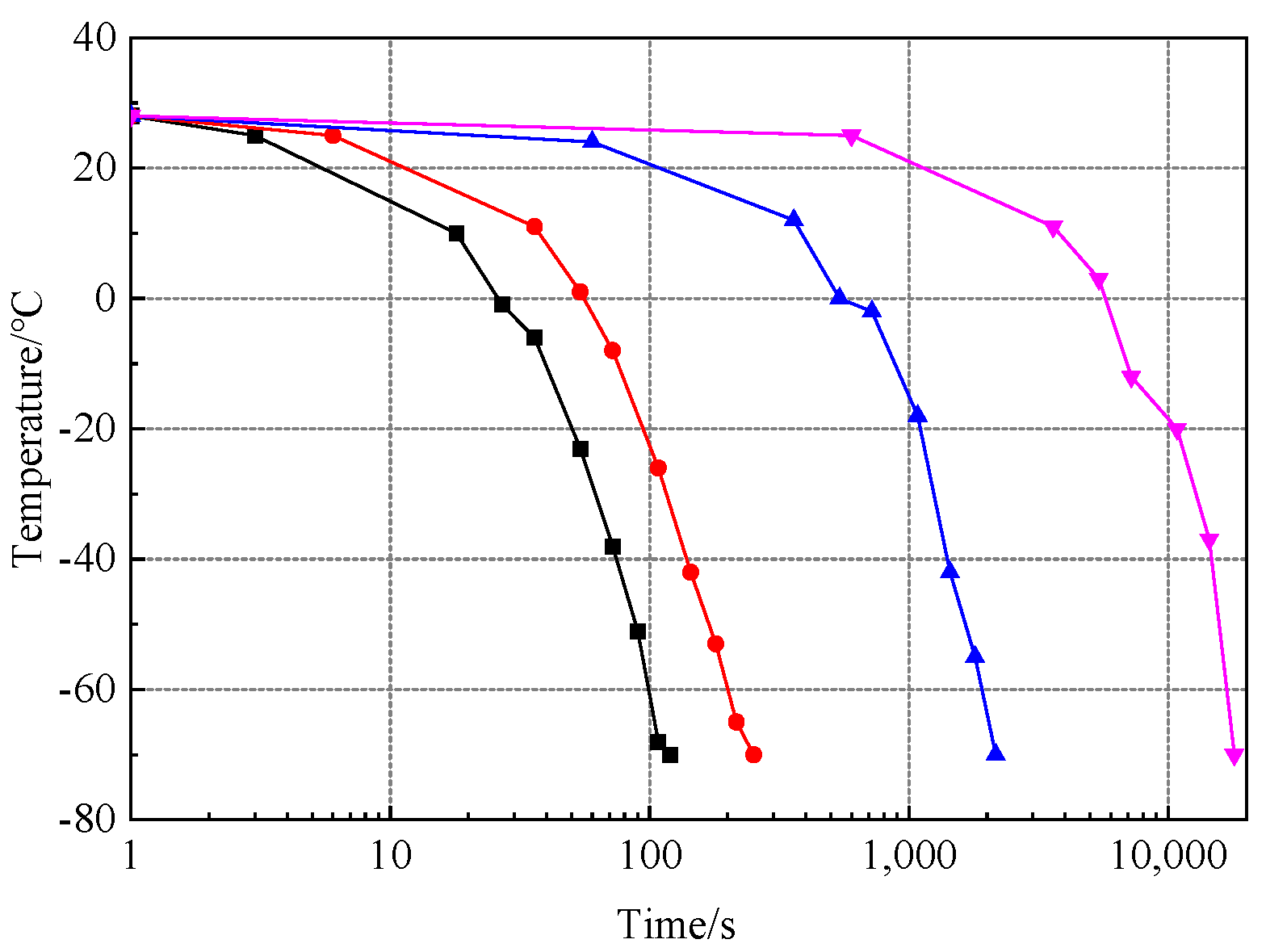

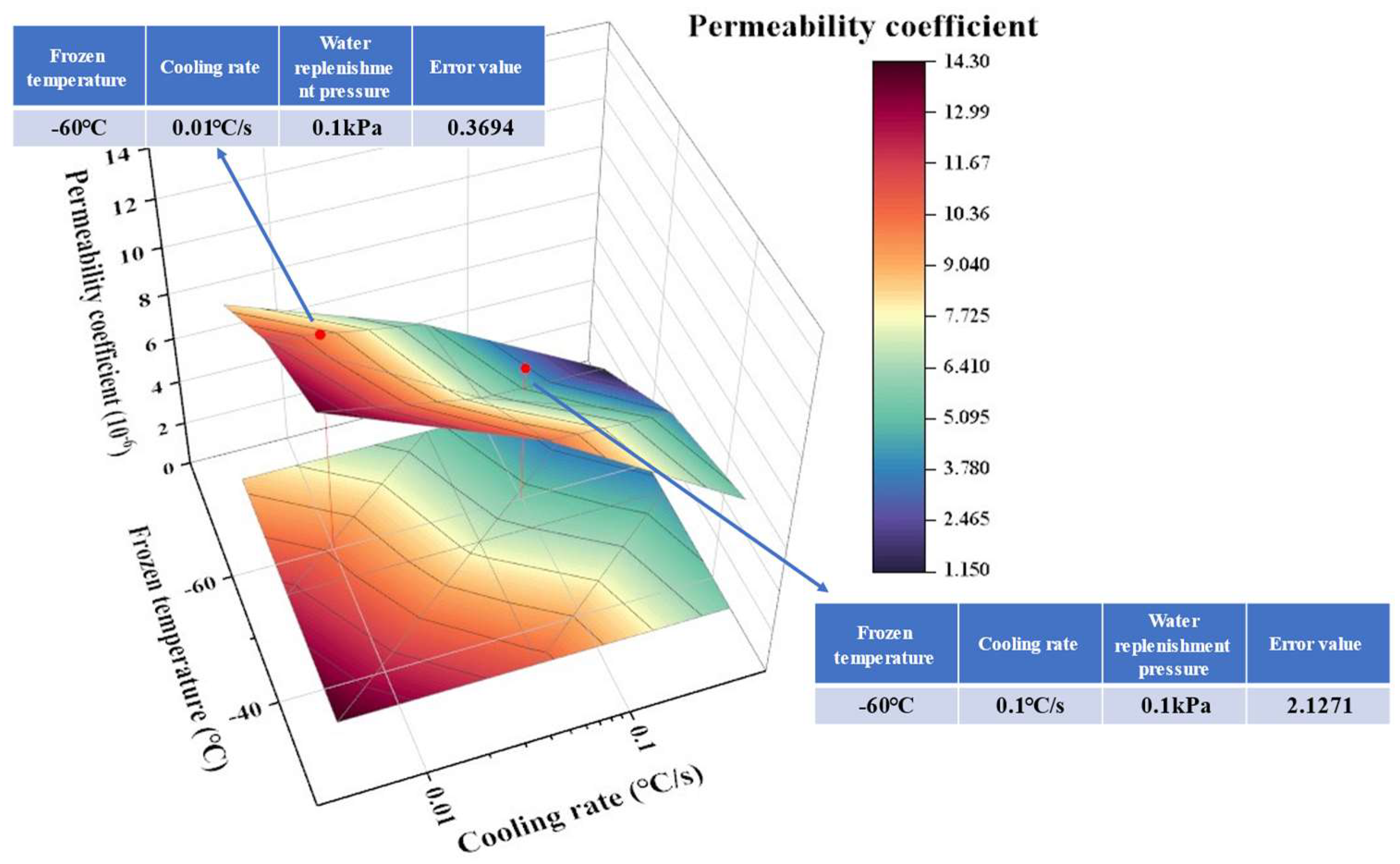

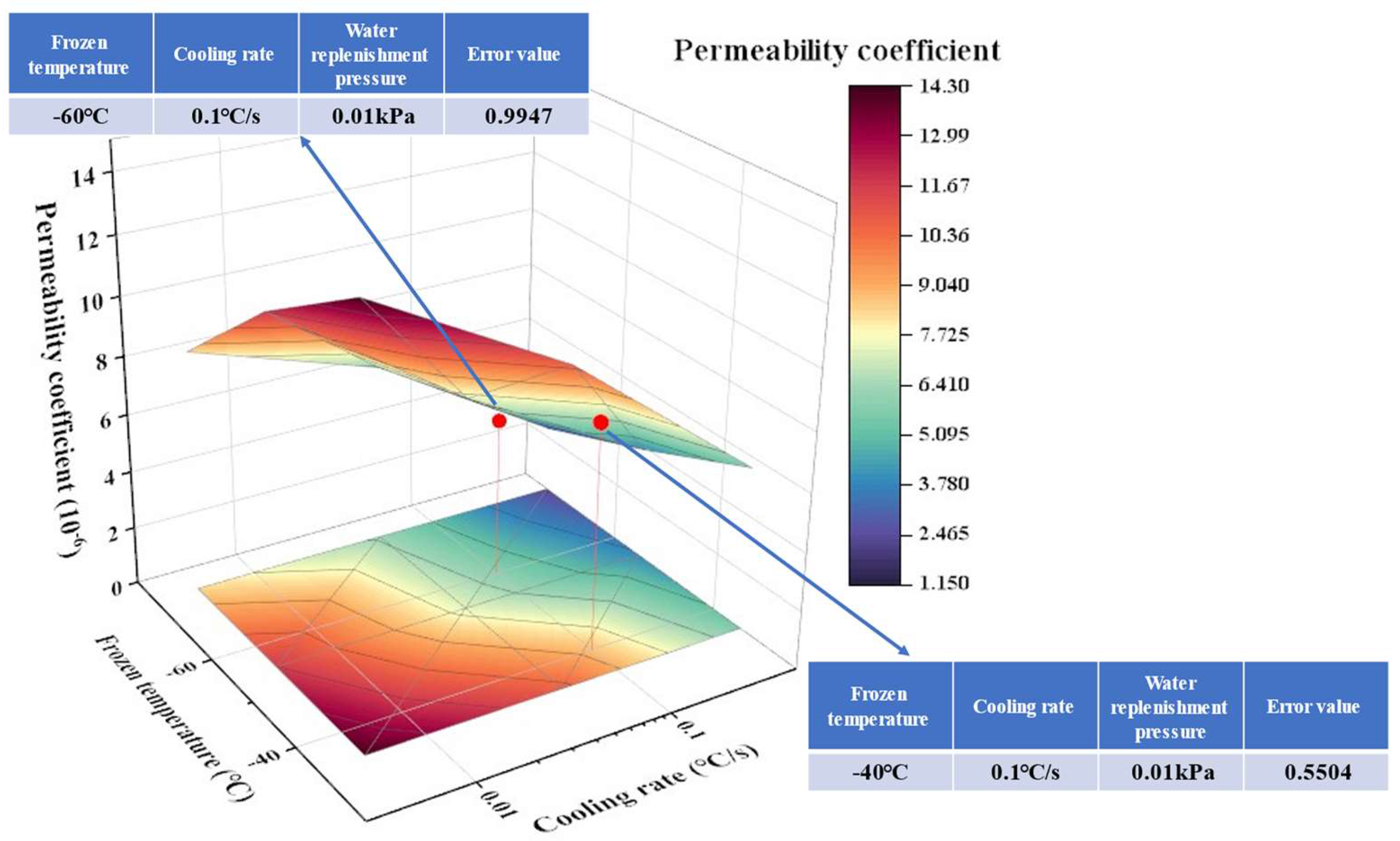

6.1. The Permeability Coefficient Prediction Model Based on the Kozeny-Carman Equation

6.2. Model validation

7. Conclusions

- Effect of Cooling Rate on Permeability: The cooling rate plays a crucial role in determining the soil permeability coefficient. Specifically, as the cooling rate increases, the permeability coefficient of thawed soil decreases. This relationship underscores the importance of controlling the cooling rate in managing soil permeability in AGF projects. Understanding and manipulating this parameter can significantly impact soil thaw settlement following artificial freezing construction.

- Coupling Effect of Temperature Gradient and Cooling Rate on Permeability: While an increase in cooling rate consistently leads to a reduction in soil permeability, the magnitude of this reduction is influenced by the temperature gradient. Specifically, the smaller the temperature gradient, the more pronounced the decrease in permeability for a given increase in the cooling rate. This coupled effect underscores the complexity of soil behavior under freezing conditions and highlights the need for an integrated approach when considering both temperature gradient and cooling rate in practice AGF projects.

- Development of a Predictive Model: A predictive model for soil permeability has been developed based on a modified Kozeny-Carman equation, which incorporates the effects of cooling rate, temperature gradient, and water replenishment pressure. This model offers a robust and adaptable tool for predicting soil permeability across a range of environmental conditions. By accounting for multiple freezing boundary conditions, it provides deeper insights into the behavior of soils after open frozen.

Acknowledgements

References

- An, R., Kong, L., & Li, C. (2020). Pore Distribution Characteristics of Thawed Residual Soils in Artificial Frozen-Wall Using NMRI and MIP Measurements. Applied Sciences, 10(2), 544. Retrieved from https://www.mdpi.com/2076-3417/10/2/544. [CrossRef]

- Bao, J., Xue, S., Zhang, P., Dai, Z., & Cui, Y. (2020). Coupled effects of sustained compressive loading and freeze–thaw cycles on water penetration into concrete. Structural Concrete, 22(S1), 11. [CrossRef]

- Chamberlain, E. (1990). Effect of freeze-thaw cycles on the permeability and macrostructure of soils. Cold Region Research and Engineering Laboratory, 90(1), 11.

- Chen, C., Zhang, C., Liu, X., Pan, X., Pan, Y., & Jia, P. (2023). Effects of freeze-thaw cycles on permeability behavior and desiccation cracking of dalian red clay in china considering saline intrusion. Sustainability, 15(4), 20. [CrossRef]

- Chen, J., Tong, H., Yuan, J., Fang, Y., & Gu, R. (2022). Permeability prediction model modified on kozeny-carman for building foundation of clay soil. Buildings, 12(11), 1798. [CrossRef]

- Hirose, G., & Ito, Y. (2017). Experimental estimation of permeability of freeze-thawed soils in artificial ground freezing. Procedia engineering, 189, 332-337. [CrossRef]

- Hui, B., & Ping, H. (2009). Frost heave and dry density changes during cyclic freeze-thaw of a silty clay. Permafrost and periglacial Processes, 20(1), 65-70. [CrossRef]

- Joudieh, Z., Cuisinier, O., Abdallah, A., & Masrouri, F. (2024). Artificial Ground Freezing—On the Soil Deformations during Freeze–Thaw Cycles. Geotechnics, 4(3), 718-741. Retrieved from https://www.mdpi.com/2673-7094/4/3/38.

- Leonhardt, F. (1997). The committee to save the tower of Pisa: a personal report. Structural engineering international, 7(3), 201-212. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y., Yang, G., Ye, W., Li, J., Wang, G., & Wang, J. (2023). Deterioration law and microscopic mechanism of hydraulic characteristics of undisturbed loess in Ili under freeze-thaw action. Journal of Engineering Geology, 31(4), 8.

- Lv, Q., Zhang, Z., Zhang, T., Hao, R., Guo, Z., Huang, X., . . . Liu, T. (2021). The Trend of Permeability of Loess in Yili, China, under Freeze–Thaw Cycles and Its Microscopic Mechanism. Water, 13(22), 19. [CrossRef]

- Ren, H., Hu, X.-d., Hong, Z.-q., & Zhang, J. (2019). Experimental study on active freezing scheme of freeze-sealing pipe roof used in ultra-shallow buried tunnels. Chinese Journal of Geotechnical Engineering, 41(2), 9.

- Ren, X., Zhao, Y., Deng, Q., Kang, J., Li, D., & Wang, D. (2016). A relation of hydraulic conductivity—void ratio for soils based on Kozeny-Carman equation. Engineering geology, 213, 89-97. [CrossRef]

- Sun, C., Wang, P., Guo, H., Song, T., & Wang, H. (2024). Study on the influence of different temperature modes on the freezing characteristics of silty clay in seasonally frozen area under unidirectional freezing. Journal of glaciology and geocryology, 46(06), 1839-1848.

- Viklander, P. (1998). Permeability and volume changes in till due to cyclic freeze-thaw. Canadian Geotechnical Journal, 35(3), 7.

- Wang, X. (2009). Study on the property and the influence to surrounding environment of artificial freezing soil’s thaw-settlement.

- Wu, T. (2021). Experimental study on frost heave characteristics of soil under different freezing modes. Journal of Zhongyuan University of Technology, 32(02), 42-47.

- Xu, J., Wang, Z., Ren, J., & Yuan, J. (2016). Experimental research on permeability of undisturbed loess during the freeze-thaw process Process. Journal of Hydraulic Engineering, 47(9), 10.

- Yang, P., & Zhang, T. (2002). The Physical and the Mechanical Properties of Original and Frozen-Thawed Soil. Journal of glaciology and geocryology, 24(5), 3.

- Zhang, H., Zhang, J.-m., Zhang, Z.-l., & Chai, M.-t. (2016). Measurement of hydraulic conductivity of Qinghai-Tibet Plateau silty clay under subfreezing temperatures. Chinese Journal of Geotechnical Engineering, 38(6), 6.

- Zhang, L. (2022). Experimental study on effect of freeze-thaw cycle on strength of clay. Qinghai Transportation Science and Technology, 34(03), 5.

- Zhang, L., Liao, Y., & Wang, D. (2023). Study on the Influence of Dry-wet and Freeze-thaw Cycles on Soil Permeability Coefficients. Construction technology, 52(9), 6.

- Zhou, J., & Tang, Y. (2015). Artificial ground freezing of fully saturated mucky clay: Thawing problem by centrifuge modeling. Cold Regions Science and Technology, 117, 1-11. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y., & Zhou, G. (2012). Intermittent freezing mode to reduce frost heave in freezing soils—experiments and mechanism analysis. Canadian Geotechnical Journal, 49(6), 686-693. [CrossRef]

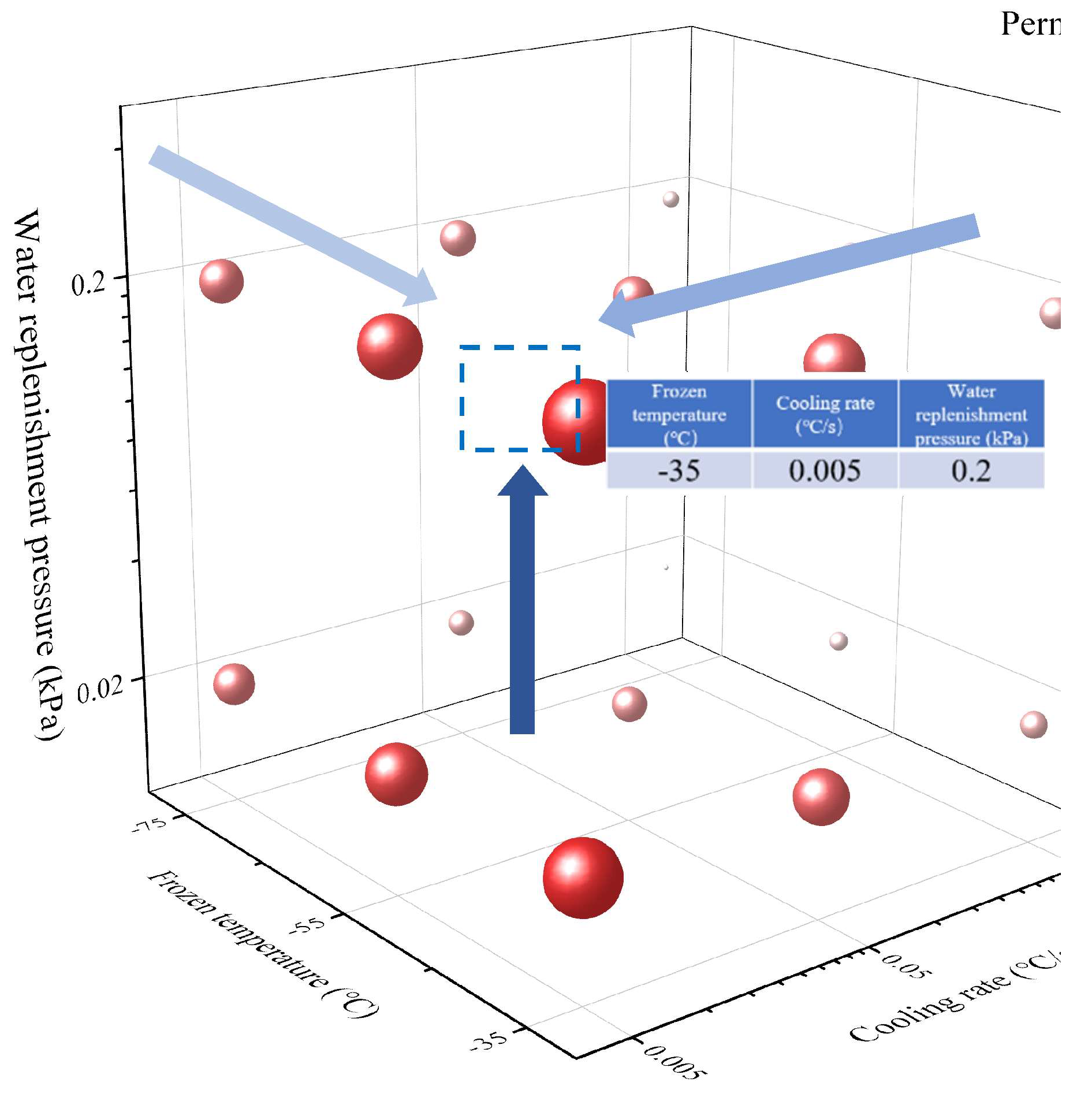

| Frozen temperature (℃) | Cooling rate (℃/s) | Water replenishment pressure (kPa) |

|---|---|---|

| -35 | 0.5 | 0.2 0.02 |

| -55 | 0.05 | |

| -75 | 0.005 |

| Group number |

Frozen temperature (℃) |

Cooling rate (℃/s) |

Water replenishment pressure (kPa) | Permeability coefficient (10^-6) |

| 1 | -35 | 0.5 | 0.02 | 5.343 |

| 2 | -35 | 0.05 | 0.02 | 10.430 |

| 3 | -35 | 0.005 | 0.02 | 13.950 |

| 4 | -35 | 0.5 | 0.2 | 5.9431 |

| 5 | -35 | 0.05 | 0.2 | 10.8363 |

| 6 | -35 | 0.005 | 0.2 | 14.2531 |

| 7 | -55 | 0.5 | 0.02 | 3.890 |

| 8 | -55 | 0.05 | 0.02 | 6.930 |

| 9 | -55 | 0.005 | 0.02 | 11.690 |

| 10 | -55 | 0.5 | 0.2 | 3.8984 |

| 11 | -55 | 0.05 | 0.2 | 7.8010 |

| 12 | -55 | 0.005 | 0.2 | 11.6972 |

| 13 | -75 | 0.5 | 0.02 | 1.170 |

| 14 | -75 | 0.05 | 0.02 | 5.230 |

| 15 | -75 | 0.005 | 0.02 | 8.260 |

| 16 | -75 | 0.5 | 0.2 | 3.5238 |

| 17 | -75 | 0.05 | 0.2 | 7.2531 |

| 18 | -75 | 0.005 | 0.2 | 8.4256 |

| Group number | Frozen temperature (℃) |

Cooling rate (℃/s) |

Water replenishment pressure (kPa) |

| 1 | -40 | 0.1 | 0.01 |

| 2 | -60 | 0.1 | 0.01 |

| 3 | -60 | 0.01 | 0.1 |

| 4 | -60 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).