Submitted:

24 January 2025

Posted:

27 January 2025

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Background

2. Evidence for Bispecific Antibodies

2.1. Glofitamab

2.2. Epcoritamab

3. Case-Based Discussions

|

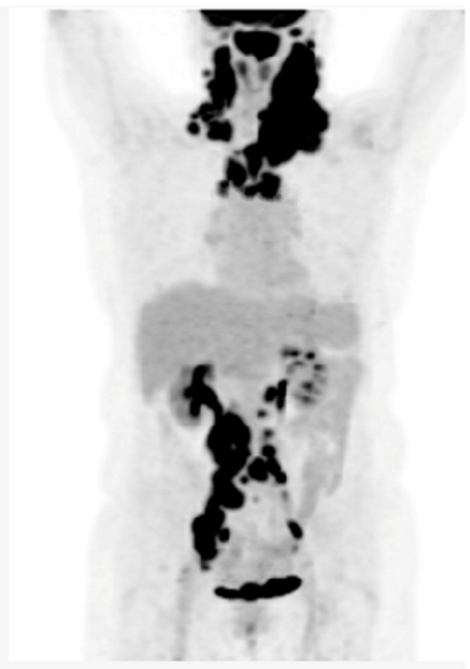

Box 1: Illustrative Case 1 | |

|

Key clinical features • 75-year-old female • Comorbidities include hypertension, type 2 diabetes and osteoarthritis • Presented with fatigue, night sweats and bilateral neck fullness • ECOG PS 2 • Labs: mild anemia 9.4 g/dL, LDH 420 U/L (ULN 240) • PET/CT: lymphadenopathy above and below diaphragm, (maximum 14 cm) Diagnosis • Biopsy of cervical lymph node suggests DLBCL, ABC subtype Initial Treatment • Treated with 6 cycles of dose-reduced R-CHOP (with 1 delay due to infection) • Complete response on post-treatment PET/CT • 20 months later, developed enlarged cervical nodes • PET/CT and biopsy confirmed recurrent DLBCL Second-line Treatment • Not considered to be a transplant/CAR-T cell candidate • Treated with Polatuzumab-BR for 6 cycles, achieved a CR and remained in remission for 18 months Third-line Treatment • She now requires further therapy • She is now frailer with an ECOG PS 3, and is being considered for a BsAb |

|

| BsAB, bispecific antibody; BR, bendamustine-rituximab; CT, computerized tomography; CR, complete response; DLBCL, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; PET, positron emission tomography; PS, performance status; ULN, upper limit of normal | |

- Guidelines for CAR-T cell therapy eligibility may vary somewhat between centres, but patients must meet a minimal level of fitness to be considered.

- Eligibility for CAR-T cell therapy is based on key clinical factors, including adequate cardiac function and a minimum renal function (CrCl greater than 30-45 ml/min). Age and traditional eligibility criteria for HDT-ASCT are less emphasized in favor of general performance status and comorbidities (target ECOG performance score 0-2).

- Given the manufacturing time for CAR-T cells, a moderate tumor burden and moderate progression kinetics are necessary to ensure a safe waiting period and treatment trajectory. Rapid disease progression and high tumor burden can compromise general performance status and CAR-T cell efficacy, due to the unpredictable effectiveness of bridging therapies. [19]

- Many patients will need to travel within their province or to another province to receive CAR T-cell therapy, which requires a suitable performance status. For individuals with comorbidities or symptoms due to lymphoma progression that limit their ability to travel, BsAbs may be a more practical and accessible treatment alternative.

- Additionally, the need for a caregiver can also be a limiting factor, either due to the caregiver's unavailability or the patient’s feeling of being a burden.

- Given that BsAbs and CAR-T cell therapy currently target distinct antigens, CD20 and CD19 respectively, a referral for CAR-T cell therapy could be subsequently considered if the patient’s overall condition improves with BsAbs. However, considering this patient’s age of 75 years and the history of multiple comorbidities, the CAR-T cell process may not be feasible and BsAbs may be the preferrable alternative option.

|

Box 2: Illustrative Case 2 |

|

Key Clinical Features • 23-year-old male • Presents with drenching night sweats, fever, anasarca and widespread lymphadenopathy • LDH 1200 U/L (ULN 250) • ECOG PS 2, IPI 4 Diagnosis • Groin node biopsy: T-cell histiocyte-rich large B-cell lymphoma • Stage IVB, bone marrow and liver involved Initial Treatment • Given RCHOP x 5 cycles • Primary refractory, with recurrent fevers, and increasing LDH Second-line Treatment • R-GDP: cycle 1 received • Initial improvement, but recurrent fevers and increasing LDH prior to cycle 2 • PET confirmed progression Third-line Treatment • Plan for CAR-T cell therapy • Time from CAR-T cell therapy consultation to leukapheresis was 4 days • No holding therapy administered, but bridging therapy with Pola-R considered • Unfortunately, T-cell collection was insufficient to enable an adequate CAR-T cell product • Potential candidate for BsAbs |

- Predictive factors for CAR-T manufacturing failure include a low CD3+ T-cell count (<150-300/µL), low proportions of naïve (CD45RA+) and central memory (CCR7+) T cells, high monocyte contamination (>40% CD14+ cells), and a suboptimal CD4/CD8 ratio (<1:3). Extensive chemotherapy, particularly with agents like bendamustine, reduces T-cell functionality and availability, while cumulative treatments and disease-related T-cell exhaustion further impair success. A high tumor burden (bulk disease) is also associated with reduced CAR-T manufacturing efficiency and outcomes. [20,21] T-cell fitness is an important component for optimization of immunotherapeutic approaches, including CAR T-cell therapy and BsAbs. [22] Unlike CAR-T cell therapy, BsAbs involve repeated dosing with intervals between treatments, which may allow for newly regenerated T-cells to contribute to the therapeutic process. [23] Moreover, unlike with CAR-T cell therapy, bendamustine-containing regimens prior to BsAbs do not appear to impact outcomes, although more data is required to support this. [24]

- Patients with rapidly progressing refractory lymphoma are often excluded from clinical trials, as their disease progression does not allow for the screening period required for enrollment. Although bridging therapies can be attempted, they are often ineffective, prohibiting patients from proceeding to CAR T-cell therapy.

- Even though BsAbs have a delayed onset of action due to the ramp-up phase to mitigate the risk of CRS, the timeline associated with a CAR-T cell therapy trajectory remains longer. This is especially important here, where the disease is aggressive.

- If rapid disease progression does not allow for CAR T-cell therapy, initiating a BsAb may be a consideration. However, real-world evidence on the efficacy of BsAbs in this setting is awaited, as well as data on the use of BsAbs as a possible bridging therapy.

- Importantly, data suggest CAR T-cell therapy remains effective in R/R LBCL patients after prior exposure to BsAbs, suggesting administration of a BsAb does not preclude patients from receiving future CAR-T cell therapy. [25]

|

Box 3: Illustrative Case 3 | |

|

Key Clinical Features • 46-year-old indigenous male from a remote area of northern Canada • Comorbidities: HTN, CAD, osteoarthritis • Presented with a large neck mass • Stage IV, IPI 4/5, ECOG PS 2 Diagnosis • Sent to a treatment center 2,000 km away for cervical node core biopsy, non-diagnostic • Sent back again for excisional biopsy, interval between biopsies was 2 months • DLBCL, non-GCB, double expressor, no MYC rearrangement Initial Treatment • Plan for R-CHOP x 6 but patient did not show for 1st cycle • Treatment start was delayed 6-weeks and patient elected to return home between cycles • PET scan after 3 cycles demonstrates mixed response Second-line Treatment • Plan for ASCT and discussed salvage with R-ICE versus R-GDP • Chose R-ICE to get longer time at home between treatment • Progression after 2 cycles Third-line Treatment • Discussion of CAR-T cell therapy versus BsAb therapy, patient elected to proceed with BsAb therapy |

|

| ASCT, autologous stem cell therapy; BMT, bone marrow transplant; BR, bendamustine-rituximab; CAD, coronary artery disease; CR, complete response; DLBCL, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; HDT, high dose therapy; HTN, hypertension; IPI, international prognostic index; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; MI, myocardial infarction; PET, positron emission tomography; PR, partial response; PS, performance status; R-CHOP, rituximab- cyclophosphamide- doxorubicin-vincristine-prednisone; R-GDP, rituximab-gemcitabine-cisplatin-dexamethasone; ULN, upper limit of normal | |

- CAR-T cell therapy requires a coordinated process involving significant contributions by the patient and healthcare team. [10,12] CAR T-cell therapy requires at minimum: an initial consultation; leukapheresis; a lymphodepleting therapy and the infusion with the need to stay in proximity of the CAR T-cell center to complete a total of one month after infusion. The vast majority of the patients are hospitalized during the initial 2 weeks after CAR-T infusion. It is also recommended that patients have a caregiver accompany them during the CAR T-cell therapy process.

- The administration of BsAbs involves frequent visits for therapy, which contrasts with the one-time administration of the CAR-T cell product. Individual preferences will likely influence patient decision making.

- Length of time away from home was the driving factor in this patient’s preference for BsAbs. Despite the frequency of administration of BsAb therapy, he preferred to travel back and forth for the shorter visits.

- For many patients, the need for travel and an extended stay near the CAR T-cell center is a meaningful barrier. The requirement to travel for treatment involves personal, familial, financial, and professional considerations. Patients' geographic distance to treatment centers is a major limitation for many patients, with those residing 2–4 hours away being 40% less likely to access CAR-T cell therapy. [26] A mapping of CAR-T cell therapy administered in the province of Quebec illustrated this unfortunate reality. [27]

- Some remote centers may initiate ramp-up of BsAbs in a regional hospital or cancer center, with later cycles administered closer to home in an infusion clinic.

- The incidence of CRS occurrence from cycle 2 onwards is very low (less than 5%), and its severity is mild (typically grade 1 or 2). [1,3] Moreover, the occurrence of CRS from cycle 2 onwards is often observed in patients who experience more severe or prolonged CRS during cycle 1, making it more predictable. The incidence and severity of neurotoxicity with BsAbs is also low, further supporting the feasibility of administration at local centers with regional oversight.

- Having a caregiver present during the ramp-up of BsAbs is recommended but not absolutely necessary, as long as patients are reliable and compliant. If there are particular concerns about a patient's condition and reliability, their monitoring period in the hospital could be extended.

- ∙ For patients who do not want to or cannot travel for CAR-T cell therapy, BsAbs may represent a valuable treatment option. However, the duration of follow-up from BsAb clinical trials remains insufficient to assess the curative potential of this approach.

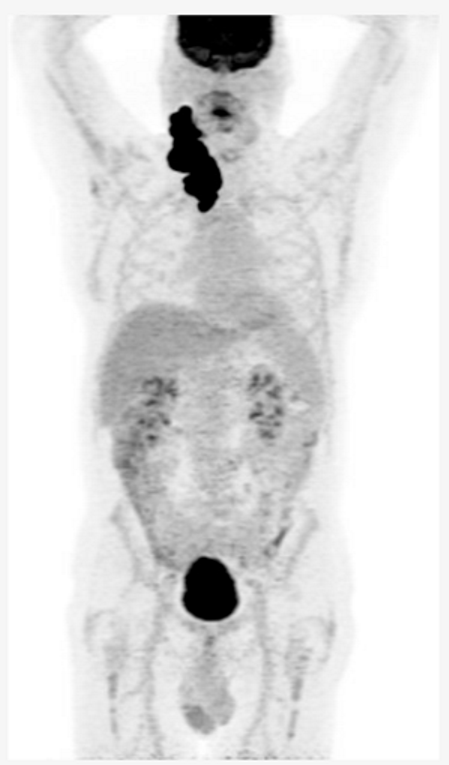

| Box 4: Illustrative Case 4 | |

|

Key clinical features • 58 -year-old male • No comorbidities • Presented with abdominal discomfort • ECOG PS 1 • Labs: LDH 350 U/L (ULN 240) • PET/CT: paravertebral soft tissue mass at T7 with extension into right lower lobe, right pelvic sidewall mass (maximum 6 cm) Diagnosis • Core biopsy of abdominal mass: DLBCL, GCB subtype, no MYC rearrangement Initial Treatment • Treated with 6 cycles of R-CHOP • CR on post-treatment PET/CT • 14 months later, developed recurrent abdominal pain, PET/CT and biopsy confirmed recurrent DLBCL Second-line Treatment • Planned for salvage and ASCT, but had progression after 2 cycles R-GDP Third-line Treatment • Referred for CAR-T-cell therapy • Received 1 cycle Pola-R bridging followed axicabtagene ciloleucel • CR on PET/CT at 3 months • Progression on PET/CT at 6 months post CAR-T-cell therapy Fourth-Line Treatment • He has been recently given epcoritamab |

|

| ASCT, autologous stem cell transplant; BsAB, bispecific antibody; CT, computerized tomography; CR, complete response; DLBCL, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; PET, positron emission tomography; PS, performance status; R-CHOP, rituximab- cyclophosphamide- doxorubicin-vincristine-prednisone; R-GDP, rituximab-gemcitabine-dexamethasone; ULN, upper limit of normal | |

- Unfortunately, this otherwise healthy man, exhibits chemo-refractory disease after initial benefit from R-CHOP and did not sustain durable benefit from CAR-T cell therapy.

- BsAbs have demonstrated efficacy for patients with R/R DLBCL regardless of prior exposure to CAR-T cell therapy. [1,3] This case illustrates the potential use of BsAbs following CAR T-cell therapy failure, with CAR T-cell therapy initially prioritized due to its longer available follow-up and known curative potential.

4. Canadian Perspective

4.1. BsAbs in CAR-T Cell Therapy Ineligible Patients

4.2. BsAbs as an Alternative to CAR-T Cell Therapy Based on Patient Preference

4.3. BsAbs for Bridging to CAR-T Cell Therapy

4.4. BsAbs Following CAR-T Cell Therapy

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Thieblemont C, Karimi YH, Ghesquieres H, et al. Epcoritamab in relapsed/refractory large B-cell lymphoma: 2-year follow-up from the pivotal EPCORE NHL-1 trial. Leukemia. Sep 25 2024. [CrossRef]

- Canadian Evidence-Based Guideline for the Treatment of Relapsed/Refractory: Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma.

- Dickinson MJ, Carlo-Stella C, Morschhauser F, et al. Glofitamab for Relapsed or Refractory Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma. N Engl J Med. Dec 15 2022;387(24):2220-2231. [CrossRef]

- Davison K, Chen BE, Kukreti V, et al. Treatment outcomes for older patients with relapsed/refractory aggressive lymphoma receiving salvage chemotherapy and autologous stem cell transplantation are similar to younger patients: a subgroup analysis from the phase III CCTG LY.12 trial. Ann Oncol. Mar 01 2017;28(3):622-627. [CrossRef]

- Gisselbrecht C, Glass B, Mounier N, et al. Salvage regimens with autologous transplantation for relapsed large B-cell lymphoma in the rituximab era. J Clin Oncol. Sep 20 2010;28(27):4184-90. [CrossRef]

- Westin JR, Oluwole OO, Kersten MJ, et al. Survival with Axicabtagene Ciloleucel in Large B-Cell Lymphoma. N Engl J Med. Jul 13 2023;389(2):148-157. [CrossRef]

- CADTH. Provisional Funding Algorithm: Indication Large B-cell Lymphoma. 2023.

- Neelapu SS, Tummala S, Kebriaei P, et al. Chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy - assessment and management of toxicities. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. Jan 2018;15(1):47-62. [CrossRef]

- Jain T, Olson TS, Locke FL. How I treat cytopenias after CAR T-cell therapy. Blood. May 18 2023;141(20):2460-2469. [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann MS, Hunter BD, Cobb PW, Varela JC, Munoz J. Overcoming Barriers to Referral for Chimeric Antigen Receptor T Cell Therapy in Patients with Relapsed/Refractory Diffuse Large B Cell Lymphoma. Transplant Cell Ther. Jul 2023;29(7):440-448. [CrossRef]

- Battiwalla M, Tees M, Flinn IW. Access barriers for anti-CD19+ chimeric antigen receptor T (CAR-T) cell therapy for non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) across a large community transplant and cellular therapy network, tandem meetings. Abstract presented at: Transplantation & Cellular Therapy Meetings of ASTCT and CIBMTR, 2023.

- Schuster SJ, Svoboda J, Chong EA, et al. Chimeric Antigen Receptor T Cells in Refractory B-Cell Lymphomas. N Engl J Med. Dec 28 2017;377(26):2545-2554. [CrossRef]

- Alarcon Tomas A, Fein JA, Fried S, et al. Outcomes of first therapy after CD19-CAR-T treatment failure in large B-cell lymphoma. Leukemia. Jan 2023;37(1):154-163. [CrossRef]

- Product Monograph: PrEPKINLYTM ( April 23, 2024 ).

- Limited H-LR. Product Monograph: PrCOLUMVI® MAR 24, 2023.

- Dickinson M, Carlo-Stella C, Morschhauser F, Bachy E. Fixed-Duration Glofitamab Monotherapy Continues to Demonstrate Durable Responses in Patients with Relapsed or Refractory Large B-Cell Lymphoma: 3-Year Follow-up from a Pivotal Phase II Study. American Society of Hematology; 2024. p. Abstract 865.

- Thieblemont C, Phillips T, Ghesquieres H, et al. Epcoritamab, a Novel, Subcutaneous CD3xCD20 Bispecific T-Cell-Engaging Antibody, in Relapsed or Refractory Large B-Cell Lymphoma: Dose Expansion in a Phase I/II Trial. J Clin Oncol. Apr 20 2023;41(12):2238-2247. [CrossRef]

- Vose J, Cheah C, Clausen M, Cunningham D. 3-Year Update from the Epcore NHL-1 Trial: Epcoritamab Leads to Deep and Durable Responses in Relapsed or Refractory Large B-Cell Lymphoma. American Society of Hematology Meeting; 2024. p. Abstract 4480.

- Zelenetz AD, Gordon LI, Abramson JS, et al. NCCN Guidelines® Insights: B-Cell Lymphomas, Version 6.2023. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. Nov 2023;21(11):1118-1131. [CrossRef]

- Clémentine Baguet , Jérôme Larghero , Mebarki M. Early predictive factors of failure in autologous CAR T-cell manufacturing and/or efficacy in hematologic malignancies. Blood Adv 2024. p. 337–342. [CrossRef]

- Locke FL, Rossi JM, Neelapu SS, et al. Tumor burden, inflammation, and product attributes determine outcomes of axicabtagene ciloleucel in large B-cell lymphoma. Blood Adv. Oct 13 2020;4(19):4898-4911. [CrossRef]

- Dubnikov Sharon T, Assayag M, Avni B, et al. Early lymphocyte collection for anti-CD19 CART production improves T-cell fitness in patients with relapsed/refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Br J Haematol. Jul 2023;202(1):74-85. [CrossRef]

- Philipp N, Kazerani M, Nicholls A, et al. T-cell exhaustion induced by continuous bispecific molecule exposure is ameliorated by treatment-free intervals. Blood. Sep 08 2022;140(10):1104-1118. [CrossRef]

- Iacoboni G, Serna A, Navarrow V, Ubieto SJ. Impact of Prior Bendamustine Exposure on Bispecific Antibody Treatment Outcomes for Patients with B-Cell Lymphoma. Blood; 2023. p. 310. [CrossRef]

- Crochet G, Iacoboni G, Couturier A, et al. Efficacy of CAR T-cell therapy is not impaired by previous bispecific antibody treatment in large B-cell lymphoma. Blood. Jul 18 2024;144(3):334-338. [CrossRef]

- Flinn R. Miles Matter: The Geographic Disparity That Impacts Access to CAR-T Therapy. AJMC; 2024. p. SP810.

- Maria Murphy MF, Julie Campeau , Michael Sebag , Félix Couture , Jean-François Larouche , Christopher Lemieux , Silvy Lachance , Sandra Cohen , Luigina Mollica , Olivier Veilleux , Isabelle Fleury. Geographical CAR-T Unmet Needs for Patients with Large B-Cell Lymphoma in the Province of Quebec Blood; 2022. p. 13228–13229. [CrossRef]

| Patient Type | Patient Description | Benefits of Bispecifics |

|---|---|---|

|

CAR-T cell therapy Ineligible |

• Inadequate performance status • Organ dysfunction |

• Provides an effective therapy with durable benefit and a favorable toxicity profile • Incidence and severity of toxicities lower than CAR-T cell therapy |

|

CAR-T cell therapy eligible |

• Rapidly progressing disease • Borderline PS for CAR-T cell therapy • Unable/unwilling to travel for CAR-T cell therapy • Concern about CAR-T cell therapy toxicity profile |

• Timely available therapy (although ramp-up may be associated with delayed response) • Provides a more flexible option offered in more centers than CAR-T cell therapy requiring less travel • Does not preclude future CAR-T cell therapy |

|

Post CAR-T cell therapy |

All fit patients | • Preferred option in terms of efficacy and safety, compared to available alternatives • Post ramp-up ease of administration • Clinical trials should also be considered, but availability often limited |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).