1. Introduction

In 1900, Planck put forward the well-known formula for black-body radiation after studying the energy distribution law of the black-body radiation spectrum:

[

1]. Shortly thereafter, he gave the statistical physical derivation for the formula [

2], surprisingly finding that energy is a discrete quantity composed of an integral number of finite equal parts, and thereby reluctantly defining the energy elements as ‘quanta’. Five years later, Einstein successfully explained the photoelectric effect by introducing the hypothesis of light quanta (known as photons later) [

3]. In the following two decades, along with the proposal of Bohr’s atomic model, the observation of Franck-Hertz experiment, the discovery of Compton effect, etc., the quantum theory was gradually recognized and accepted, which brought about drastic changes in physics. However, for the same object, say light, two sets of completely different theories are needed to describe its different phenomena, and both the theories are valid to a certain extent, making the divergence between quantum theory and classical physics increasingly large. Compared with the mature classical physics, the quantum theory at that time was still fragmented, lacking a solid foundation and rigorous logical structure. From 1925 to 1926, Heisenberg, Born and Jordan established the matrix mechanics [

4,

5,

6], and Schrödinger established the wave mechanics [

7,

8,

9,

10], and therefore the mathematical formalism of quantum mechanics was established. Since the birth of quantum mechanics, it has shown amazing ability in the qualitative explanation of general problems and the quantitative calculation of specific problems.

Unlike classical physics, which is established through the generalization and summarization of experimental phenomena and experience (a typical positivistic approach), the mathematical formalism of quantum mechanics was fulfilled prior to its interpretation. At the beginning of the establishment of quantum mechanics, some non-logical terminologies, such as wave-function and operator, were introduced. These non-logical terminologies have no empirical meaning except that they imply physical content in the formalism. To endow this formalism with physical meaning by transforming it into a hypothetical deductive system which is empirically stated, it is necessary to associate some non-logical terminologies or some formulas containing non-logical terminologies with the observable phenomena and empirical operations, i.e., setting up the correspondence rule between them. Physicists at that time paid painstaking efforts to explore the correspondence rules, aiming at setting up a model or explanatory principle to interpret quantum mechanics. The Copenhagen interpretation eventually came to be regarded as the orthodox interpretation of quantum mechanics. However, quantum mechanics is so weird and counterintuitive, and it has raised a long debate. Even the Copenhagen interpretation failed to reach an agreement on some fundamental issues of quantum mechanics. For example, Heisenberg insisted that the uncertainty principle was an independent principle, while Bohr attempted to incorporate it into his complementarity principle. Although most of the principles of Copenhagen interpretation are accepted by the mainstream scientists, the probabilistic interpretation of the wave-function [

11] is the most controversial. Probabilistic interpretation implies the abandonment of causality and determinism, which was unacceptable to Einstein. Einstein refused to accept quantum theory as a complete description of physical reality [

12], leading to decades of controversies regarding the interpretation of quantum theory between him and Bohr. Finally, in 1935, he proposed a paradox with Podolsky and Rosen (known as EPR paradox), questioning the completeness of quantum mechanics [

13]. From then on physicists largely adhered to the Copenhagen interpretation, the controversies were considered as a strictly philosophical quarrel by most physicists. Nearly thirty years later, Bell proposed an inequality to test the locality of quantum mechanics [

14], transforming question about the completeness of quantum mechanics by the EPR paradox into that about non-locality. Bell’s inequality translates the immaterial philosophical ideas involved in the EPR paradox into concrete quantitative mathematical descriptions, and provides access to experimental test. Bell’s inequality does not judge the completeness of quantum mechanics, but only to illustrate whether quantum mechanics or local hidden variable theory should be chosen. Subsequent experiments on the test of Bell’s inequalities and its improved forms have shown that these inequalities are violated [

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23], indicating that any local hidden variable theory cannot reproduce all the statistical predictions of quantum mechanics. The new techniques, thoughts, tools developed to test the Bell’s inequality are helpful to explore the laws of the physical world.

There is still no consensus regarding the interpretation of quantum theory, and the controversy about it is a story without an ending. By reviewing the thoughts, discussions, and debates during the establishment and development of quantum mechanics, we attempt to find out the root that accounts for difference between quantum mechanics and classical physics. Inspired by the work concerning hidden variable theories by von Neumann, de Broglie, Bohm, et al. [

24,

25,

26,

27], we seem to have found the answer: the existence of a precision limit for observation makes microscopic objects indistinguishable and prevents the deterministic description of the microscopic objects’ states. In this paper, we will deduce logically how to relate the identity principle with the probabilistic interpretation, uncertainty principle, quantization in quantum mechanics, and discuss the possibility of restoring determinism and causality in quantum mechanics. We do not focus on the origin of identical particles, and consequently only the low energy case is discussed, in which quantum mechanics is incredibly accurate. In the high energy cases, relativistic effects must be considered, and therefore new methods should be developed. Consequently, quantum field theory, including quantum electrodynamics and quantum chromodynamics, is beyond our discussion.

2. What Is the Identity?

In classical physics, there is no two identical objects, for example, when we discuss the collision between two particles, we never discuss how to distinguish them, but just label them as 1 and 2, for there is always a way to distinguish them, such as size, shape, color, and so on. In quantum mechanics, it is assumed that there exists some class of particles with the identical intrinsic physical properties, such as rest mass, charge, spin, etc., and these particles are indistinguishable, thereby being called identical particles. For the identical particles, as long as their quantum numbers are the same, they cannot be distinguished by any measurement means, and naturally cannot be labelled as 1 and 2, and this is the unique identity of quantum mechanics. The identity can therefore be equivalent to the indistinguishability. In this paper, we mainly attempt to sort out some logic for quantum theory, and therefore do not present the mathematical expressions regarding the identity as well as quantum indistinguishability, which can be found in the textbooks of quantum mechanics.

In quantum mechanics, the states of microscopic objects are described by wave-functions , and the systems which can be described by the same wave-function are called the identical systems. The state of the microscopic system remains unchanged when exchanging the states of any two particles (exchanging the states of any two particles only makes the wave-function symmetric and anti-symmetric). The same wave-function means that the same degree of freedom is adopted. In early quantum theory, the state of a microscopic system could be described by using a wave-function containing three quantum numbers, i.e., the principal quantum number n, the angular quantum number l, and the magnetic quantum number ml. However, it was faced with great difficulties when dealing with some phenomena, such as the double lines in the emission spectra of alkali-metal atoms in magnetic fields, anomalous Zeeman effect, Stern-Gerlach experiment, etc. The experimental outcomes of these phenomena cannot be predicted by using the wave-function containing the three quantum numbers (n, l, and ml), suggesting that the wave-function fails to provide a complete description of these phenomena. Later, by the introduction of a fourth quantum number, i.e., the magnetic spin quantum number, ms, these phenomena were completely explained. When dealing with most problems, microscopic objects described by wave-function with four identical quantum numbers are treated as identical particles. Numerous studies have shown that most problems can be fully described by the wave-functions considering these four quantum numbers.

3. What Causes the Identity?—Existence of a Precision Limit for Observation

Quantum mechanics describes the interaction between microscopic objects, that is, the measurement process. For this reason, measurement theory influences quantum theory from the underlying logic, whereas, it is the most problematic and controversial part of quantum theory. The establishment of quantum mechanics, especially matrix mechanics, depends on observable quantities, which are obtained by the measuring apparatus. In the process of measurement, the interacting objects exchange energy quanta, thereby changing both the states of the measured object and the measuring apparatus, and thus information of the measured object is obtained through the change of the states.

Even the most sophisticated measuring apparatus requires the use of media like photoelectricity to fulfill measurement. For macroscopic objects, the energy and momentum of photons are too small to cause a distinguishable change in the states of the macroscopic objects; while for microscopic objects, taking electron as example, the momentum and energy of the photons are close to that of the electrons, and the measurement process inevitably causes the non-ignorable change of their states. To obtain the determinate location and momentum of the electrons, particles with size and momentum much smaller than the electron should be adopted in the measurement, and only by this means, the measurement conducted by this kind of particles does not change the states of the electrons. However, the cost is , resulting in (where is reduced Planck constant). As a consequence, the uncertainty principle breaks down and quantum mechanics no longer works. In other words, a deterministic description of a microscopic object can be made only if the relation is not valid. Obviously, such particles do not exist. If they did exist, a sub-quantum mechanics theory would need to be developed. Therefore, it is the precision limit for observation that prevents the deterministic description of microscopic objects. This precision limit is determined not by the measuring apparatus, but by the action quantum h behand the objective physical law. The higher the resolution of the measuring apparatus, the higher the measurement precision is. Unfortunately, the upper limit of the resolution of most measuring apparatus cannot reach the precision limit. Strictly speaking, no measuring apparatus can overstep the precision limit.

The microscopic objects cannot be distinguished by any means when the difference between them is lower than the precision limit, and thus they become identical particles. The existence of a precision limit makes it impossible to describe microscopic objects deterministically. We have to consider all possible cases and assign probability to each case, describing its state in terms of wave-function. By this means, complete description can be provided for physical phenomena as far as possible. For example, it is impossible to predict the specific time at which a single radioactive atom decays, and its half-life period can be obtained only by recording and counting the decay processes of a large number of radioactive atoms. As a matter of fact, the use of statistical methods for microscopic objects is a compromise solution for not knowing all the details. There is fluctuation (also known as error or uncertainty) in this statistic, naturally leading to the uncertainty principle. It has an explicit mathematical proof, i.e., the Fourier bandwidth theorem [

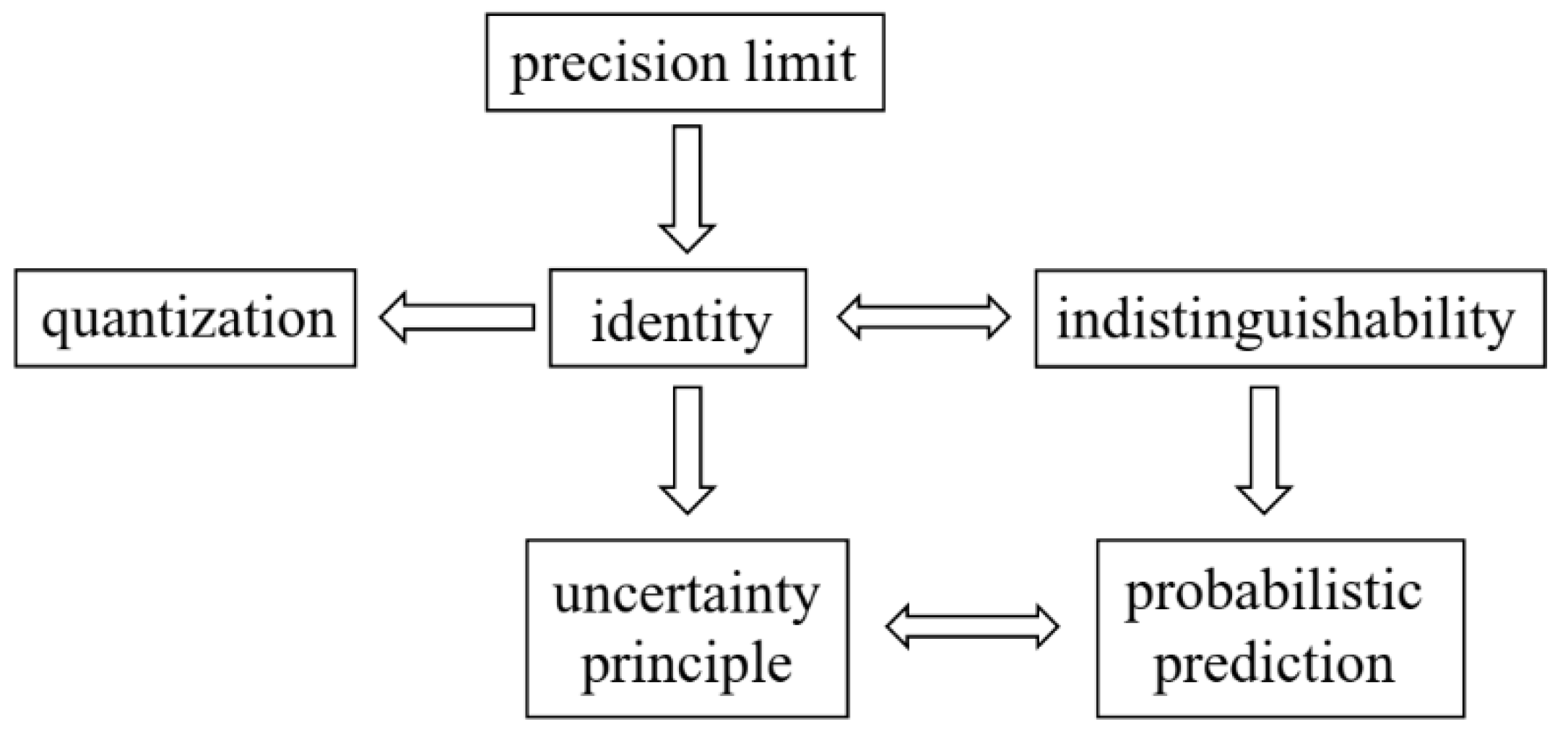

28]. Therefore, uncertainty is inherent with the existence of a precision limit. Obviously, all the problems of quantum mechanics stem from the indistinguishable properties of microscopic objects caused by the existence of a precision limit, that is, identity, but it cannot be solved and can only be considered as a fundamental principle. An overview of all the logical implications is given in

Figure 1, and the physical and philosophical arguments in this paper are based on the sketch.

4. How to Deal with Identity?

Identity limits the description of the state of microscopic object, leading to the fact that two states are either exactly same or completely different, and thus there is no continuous transition, resulting in the quantization of the state of microscopic objects. For this reason, identity and quantization are essentially related to each other. Although the measuring apparatus cannot distinguish the identical particles, it can accurately identify the number of identical particles, thus providing the statistical distribution. The conclusion that the states of microscopic objects are quantized can be reached just by the statistical physical derivation of mathematical expressions of Bose-Einstein statistics or Fermi-Dirac statistics. Planck concluded that energy is quantized through statistical physical derivation of his formula for the energy distribution law of the black-body radiation spectrum which follows the Bose-Einstein statistics [

2].

Obviously, quantization is related to two or more microscopic states with distinguishable differences. The difference between the two quantum states may cause observable changes (the process is limited by the transition selection rules), which are known as observable quantities. In matrix mechanics, the transition matrix elements are given directly, corresponding to the observable quantities. Although the wave-function in wave mechanics is not observable quantity, the difference between the initial state and the final state is observable quantity. Quantum precision measurement is based on this principle: When the microscopic systems such as electrons, photons, phonons, atoms and molecules are coupled with the external factors such as electromagnetic field, temperature and pressure, their states will be changed, and the relevant information about the magnetic field, electric field, force, temperature, etc. can be obtained by detecting the states of the microscopic systems before and after changes.

Each observable quantity is related to two stationary states. When the transition occurs between these two stationary states, the transition probability and transition frequency correspond to the relative intensity and frequency of the observable radiation, respectively. The physical properties of the microscopic objects are quantized, and the energy, momentum and angular momentum etc. are integer/half-integer multiples of the basic quantum, and consequently the measurement results are necessarily discrete. For example, for hydrogen atoms, their energy levels are discrete due to the quantization of orbital angular momentum; For a one-dimensional square potential well with infinite depth, two perfect walls form a resonant cavity, and only the electromagnetic waves forming a stable standing wave can exist stably, which has been confirmed by the Casimir effect in vacuum [

29,

30].

Here, we get back to the measurement in quantum mechanics. During the measurement, the measured object interacts with the measuring apparatus, exchanging energy quanta, thereby changing the states (energies) of the microscopic objects. It is quite clear that measurement is a process of changing the microscopic objects’ states from indistinguishable to distinguishable, and it is a process of destroying the identity. For example, if we start with two cats which are exactly same (indistinguishable), and one of them dies through the coupling of a radioactive atom, then the two cats’ states become distinguishable, so that they can be named. This example easily reminds us of the Schrödinger’s cat thought experiment [

31].

5. Probabilistic Determinism and Indeterminacy of Initial State

The evolution of the state of the microscopic system with time satisfies the Schrödinger equation:

For any given wave-function

, providing that there is a definite Hamiltonian, the time-evolution of wave-function can be obtained by Schrödinger equation. It is somewhat similar to determinism in classical physics, where the evolution of an object’ state depends on the initial state and interaction process. There exist some differences: in general, classical physics predicts a definite value for some point, while quantum mechanics predicts the probability within a certain interval, but the probability is definite. Schrödinger equation can accurately describe the time-evolution of the quantum system’ state, which is actually a kind of determinism. However, this kind of determinism is probabilistic and we can call it ‘probabilistic determinism’.

The wave-function has considered all possible cases of the system’s state, and it also give the initial value of the microscopic object’s state. Since the Schrödinger equation is linear, the evolution of the wave-function satisfying the equation is unitary, and the resulting wave-function of the final state still follows the statistical law, and therefore the statistical fluctuations are naturally preserved. Though the Hamiltonian describing the interaction is definite, due to the uncertainty of the initial value, the subsequent state is still indeterminate and can only be described in terms of probabilities. It seems that the uncertainty of the final state is endowed not by the interaction but by the initial state.

Here, we get back to the measurement theory in quantum mechanics once again. During the measurement, energy quanta are exchanged between the interacting objects and energy conservation is satisfied. A successful example is the Jaynes-Cummings model [

32]. For this reason, it seems reasonable to provide a clear physical picture of the interaction process depending on whether the energy quanta are exchanged and the number of the energy quanta exchanged

n. We had tried to do that, but just to make the problem more complicated, because the initial states of the interacting objects are indeterminate, leading to the uncertainty in the number of energy quanta exchanged during the interaction. If we could restore the determinacy of the initial state, the measurement problem would be solved.

The identical system is described by the same wave-function, which is a compromise solution to the indeterminacy of the initial value. The initial value often corresponds to the spatial-time information, i.e., the initial location of the particle in space and time domain, which is related to the phase information

in the wave-function

. However, phase cannot be extracted by any means, and consequently the indistinguishability of the phase corresponds to the identity, which can be traced back to the existence of a precision limit for observation. Since the distribution of the probability density in space and time

equals to square of the wave-function module

, i.e.,

, phases do not affect the statistical distribution of particles, which are thereby generally considered physically meaningless. Only when two states are different in phase and the phase difference is constant, can observable effects be triggered, which is the most common way to implement the precision measurement [

33,

34].

6. Nonlocal Hidden Variable Theories—Hope to Restore Determinism?

If the determinacy of the initial value can be restored, that is, all the details of the microscopic objects at a certain moment is known, then their future development can be deterministically described. Although the existence of a precision limit makes the microscopic objects indistinguishable, the difference below the precision limit will lead to the fact that the identical objects may be not truly identical in a real sense, and there may be yet-to-be-discovered underlying physics. The non-local hidden variable theories, especially Bohmian mechanics, is based on this consideration. Bohmian mechanics is a causal interpretation of quantum mechanics and is also called de Broglie-Bohm interpretation [

26,

27]. In Bohmian mechanics, the initial location distribution of Bohmian particles is constructed by the wave-function, which distinguishes the identical particles and restores the determinacy of the initial value. By this means, the wave-function is replaced by the ensemble of Bohmian particles. Then, by solving the Newton-Bohm equation and thus describing the evolution of each Bohmian particle by corresponding Bohmian trajectory, the deterministic description of Bohmian particle is realized, which seems to bring hope to restore determinism and causality [

35]. However, the description of microscopic objects can only be given through the statistics of Bohmian particles. And therefore, the measurement of particle’s location or momentum must still adhere to the uncertainty principle. It has shown that Bohmian mechanics can fully reproduce the predictions of quantum mechanics. We have applied Bohmian mechanics to study the ionization, excitation, radiation and other processes of atoms in the light field [

36,

37,

38], and found that the results are completely consistent with the quantum mechanical predictions, and besides, clear physical pictures of these processes are given.

Unfortunately, limited by the precision limit, it is impossible to accurately measure all the details about the microscopic objects at the same time. The initial value of the microscopic system can only be described by wave-function, and the description of the system’s future evolution is also not deterministic, though the evolution of the quantum state follows the Schrödinger equation, i.e., probabilistic determinism. Since it is impossible to know all the details about the microscopic objects at the same time, the cause of each event cannot be determined, bringing about the causal anomalies. Einstein once tried to establish the causal connection between the wave and particle properties for microscopic objects, and to incorporate quantum theory into a field theory based on the causality and continuity principle, but he failed [

39]. Therefore, the existence of a precision limit prevents the deterministic description of the states of microscopic objects, and it is impossible to restore causality and determinism in quantum mechanics.

Let’s get back to Bohmian mechanics, Bohmian particles are virtual particles constructed through the mathematical treatment of wave-functions, which cannot be verified experimentally. As mentioned previously, the description of microscopic objects can only be given by statistics of Bohmian particles, which is in effect to reconstruct the wave-functions. In addition, Bohmian mechanics suffered from epistemological dilemmas. The quantum potentials in Bohmian mechanics is also constructed by mathematical treatment of wave-functions, thus preserving non-locality. However, it is problematic when dealing with multi-body systems: In quantum mechanics, for example, a two-body system is described by a wave-function, and when one object is measured, the description of it changes, and that of the other object changes accordingly. However, according to the setting of Bohmian mechanics, changing the state of an object will affect the state of the other object sharing correlation with it, leading to the ‘spooky action at a distance’, which is the most controversial aspect of Bohmian mechanics.

Although the local hidden variable theories have been denied by Bell’s theorem and numerous related experiments [

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23], the non-local hidden variable theories have not been falsified. Leggett proposed a class of non-local reality models and gave a new inequality [

40], and pointed out that quantum mechanics can violate this inequality, determining that such non-local reality models cannot fully describe quantum mechanics. Whether Leggett inequality is violated and whether it can judge the correctness of quantum mechanics and non-local hidden variable theories are also widely debated [

41,

42,

43,

44,

45].

The uncertainty principle cannot be completely described by using the terminologies of classical physics, i.e., there is no counterpart of it in classical physics. Hidden variables are some unknown physical quantities introduced to ensure the objectivity of the reality, aiming at restoring the complete description of physical reality. It is inherently contradictory to the uncertainty principle. Therefore, any hidden variable model constructed by only using the terminologies of classical physics cannot reproduce the quantum mechanical predictions. In other words, there is no hidden variable model that can be experimentally verified, though I have no rigorous proof at present.

7. Boundary Between the Classical and Quantum Worlds

It is impossible to reconstruct causality and determinism in quantum mechanics, as opposed to classical physics. It naturally raises the question: where is the boundary between the so-called classical and quantum worlds? Before answering this question, we need to clarify what is quantum?

For quantum concept, only quantum properties are meaningful, and they are obtained after dividing the physical phenomena by the specific rules made by mankind according to their own cognition. Therefore, quantum mechanics is a mathematical description that only makes sense when dealing with interaction between the microscopic objects. Photon, for example, its wave and particle properties are just the sides shown in a certain way, and it is neither a wave nor a particle before observation, i.e., it has no properties for it doesn’t make sense. Of course, there are also observation-free sides (such as the spin, the rest mass, charge) that endow the microscopic objects with reality.

It is not appropriate to describe the world in terms of ‘quantum’ and ‘classical’. Tentatively, we name the worlds described in terms of quantum mechanics and classical physics as the quantum world and classical world, respectively. Although they follow two entirely different sets of laws, the underlying logic is the same: physical laws are derived from observations, and both classical physics and quantum mechanics are established based on measurements. For example, observation requires the scattering of photons, but what is different is that the influence of photons on macroscopic objects is not significant, so the classical world can be considered unaffected by the measurement process; while the photons have a great influence on the microscopic objects, which changes the state of system to be measured, so that the definition of the state of system to be measured depends on the interaction. We can see that the ‘quantity’ accounts for this problem. It is the quantitative change that causes the qualitative change of the state of the measured system, which makes the research subjects different in the two cases: In classical physics, usually attention only need to be paid to the measured objects; while in quantum mechanics, the entirety composed of the measured object and the measuring apparatus must be considered. The observation processes bring about uncontrollable influence on the microscopic objects, showing randomness, and the stochastic phenomenon can only be described by statistical laws.

In classical physics, it seems that once the initial conditions are determined, by solving the classical dynamics equation, the location and velocity of the objects at any moment can be predicted deterministically. Does this mean that the classical world must be deterministic? Obviously, it is only theoretically true. As it comes to the experiments, the errors in the measurement outcomes for the macroscopic objects can be ignored when the time scale is small, but they become visible to eyes when the time scales in question are large enough. Taking a meteorite with a diameter of 1m flying in space as an example, its velocity is measured to be . Even if the measurement error in the velocity is only , the deviation in its travel distance can reach after one year of flight, and the prediction of its position must take this deviation into account. If the measurement error in its motion direction is considered, the deviation in position will be much larger, and the deterministic description of its position is out of the question. Therefore, there is no absolute boundary between the so-called classical and quantum worlds. The ‘classical’ and ‘quantum’ are merely attributes imposed on the observed world, depending on the problem discussed. In the example of flying meteorite above, even the classical world, deterministic predictions cannot be given when it is discussed on a time scale large enough.

Quantum mechanics is weird, counterintuitive and hard to understand, and there is still no consensus regarding its interpretation of quantum. In most cases, the laws of the physical world that we witness every day are usually understood based on classical physics which are idealizations of our observations, and it provides a description of the physical reality consistent with our common sense. There is no need to consider the uncertainty principle to discuss the observed phenomena. As it comes to the microscopic objects, due to the existence of a precision limit for observation, only probabilistic predictions for the measurement outcomes can be provided by the quantum mechanics. In effect, quantum mechanics and classical physics are essentially unified, apart from the fact that a higher precision is involved in quantum mechanics, for quantum mechanics is the theory dealing with the precision limit for observation.

8. Conclusions

Due to the existence of a precision limit for observation, the state of the microscopic objects cannot be distinguished and can only be described statistically. This statistical description leads to the probabilistic determinism and the indeterminacy of initial state in quantum mechanics. The indeterminacy of initial state of microscopic objects results in that of the interaction between microscopic objects. It is the identity that leads to the probabilistic interpretation, uncertainty principle, quantization, which is the root that accounts for difference between quantum mechanics and classical physics. It seems that once the initial value can be described deterministically, subsequent evolution is deterministic and the physical picture of the measurement process becomes clear. Non-local hidden variable theory, especially Bohmian mechanics, by distinguishing identical particles, equivalent to restoring the determinacy of the initial value, is expected to restore determinism and causality. However, any hidden variable theory constructed by only using the terminologies of classical physics cannot reproduce the quantum mechanical predictions. In addition, since quantum mechanics has high precision in quantitative calculation and high efficiency in explaining interactions between microscopic objects, there is no urgent necessity to restore determinism and causality at present. After all, the most effective and persuasive approach to examine the correctness of a theory is experimental test, rather than the philosophical discussions and logical deductions. The scope of the discussions determines whether to adopt classical physics or quantum mechanics when dealing with problems, and even no deterministic predictions can be made for the classical world when the time scale discussed is large enough. Therefore, there is no absolute boundary between the so-called classical and quantum worlds.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.L. and C.L.; writing—original draft, S.L.; writing—review and editing, S.L., C.L. and M.J.; funding acquisition, M.J.; supervision, S.L. and M.J.; project administration, S.L. and M.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research was partially supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (Grant No. 2019YFA0307701), and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 11974138).

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Planck, M. On an improvement of Wien’s equation for the spectrum. Ann. Physik 1900, 1, 719–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Planck, M. On the law of distribution of energy in the normal spectrum. Ann. Physik 1901, 4, 553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Einstein, A. On a heuristic point of view concerning the production and transformation of light. Ann. Physik 1905, 17, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Heisenberg, W. Über quantentheoretische umdeutung kinematischer und mechanischer beziehungen. Z. Physik 1925, 33, 879–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Born, M.; Jordan, P. Zur Quantenmechanik. Z. Physik 1925, 34, 858–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Born, M.; Heisenberg, W.; Jordan, P. Zur Quantenmechanik II. Z. Physik 1925, 35, 557–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrödinger, E. Quantisierung als Eigenwertproblem. Ann. Physik 1926, 79, 361–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrödinger, E. Quantisierung als Eigenwertproblem. Ann. Physik 1926, 79, 489–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrödinger, E. Quantisierung als Eigenwertproblem. Ann. Physik 1926, 80, 437–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrödinger, E. Quantisierung als Eigenwertproblem. Ann. Physik 1926, 81, 109–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Born, M. Zur Quantenmechanik der Stoßvorgänge. Z. Physik 1926, 38, 803–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Einstein, A. Physics and reality. J. Franklin Inst. 1936, 221, 349–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Einstein, A.; Podolsky, B.; Rosen, N. Can quantum-mechanical description of physical reality be considered complete? Phys. Rev. 1935, 47, 777–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, J.S. On the Einstein Podolsky Rosen paradox. Phys. 1964, 1, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clauser, J.F.; Horne, M.A.; Shimony, A.; Holt, R.A. Proposed experiment to test local hidden-variable theories. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1969, 23, 880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freedman, S.J.; Clauser, J.F. Experimental test of local hidden-variable theories. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1972, 28, 938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aspect, A.; Grangier, P.; Roger, G. Experimental tests of realistic local theories via Bell’s theorem. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1981, 47, 460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aspect, A.; Grangier, P.; Roger, G. Experimental test of Bell’s inequalities using time-varying analyzers. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1982, 49, 1804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aspect, A.; Grangier, P.; Roger, G. Experimental realization of Einstein-Podolsky-Rosen-Bohm Gedankenexperiment: a new violation of Bell’s inequalities. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1982, 49, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunner, N.; Cavalcanti, D.; Pironio, S.; Scarani, V.; Wehner, S. Bell nonlocality. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2014, 86, 419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hensen, B.; Bernien, H.; Dréau, A.E.; Reiserer, A.; Kalb, N.; Blok, M.S.; Ruitenberg, J.; Vermeulen, R.F.L.; Schouten, R.N.; Abellán, C.; Amaya, W.; Pruneri, V.; et al. Loophole-free Bell inequality violation using electron spins separated by 1.3 kilometres. Nature 2015, 526, 682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abellán, C.; Amaya, W.; Mitrani, D.; Pruneri, V.; Mitchell, M.W. Generation of fresh and pure random numbers for loophole-free Bell tests. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2015, 115, 250403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The BIG Bell Test Collaboration. Challenging local realism with human choices. Nature 2018, 557, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Neumann, J. Mathematical foundations of quantum mechanics; Princeton University Press: Princeton, New Jersey, 1955. [Google Scholar]

- de Broglie, L. La mécanique ondulatoire et la structure de la matière et du rayonnement. J. Phys. Radium. 1927, 8, 225–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohm, D. A suggested interpretation of the quantum theory in terms of ‘hidden’ variable. I. Phys. Rev. 1952, 85, 166–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohm, D. A suggested interpretation of the quantum theory in terms of ‘hidden’ variable. II. Phys. Rev. 1952, 85, 180–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsao, Y.H. Uncertainty principle in frequency–time methods. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 1984, 75, 1532–1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plunien, G.; Müller, B.; Greiner, W. The casimir effect. Phys. Rep. 1986, 134, 87–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bordag, M.; Mohideen, U.; Mostepanenko, V.M. New developments in the Casimir effect. Phys. Rep. 2001, 353, 1–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrödinger, E. Die gegenwärtige Situation in der Quantenmechanik. Naturwissenschaften 1935, 23, 844–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaynes, E.T.; Cummings, F.W. Comparison of quantum and semiclassical radiation theories with application to the beam maser. Proc. IEEE 1963, 51, 89–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braunstein, S.L. Quantum limits on precision measurements of phase. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1992, 69, 3598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baso, D.N.; Averitt, R.D.; Hsieh, D. Towards properties on demand in quantum materials. Nat. Mater. 2017, 16, 1077–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bohm, D. Proof that probability density approaches |2 in causal interpretation of the quantum theory. Phys. Rev. 1953, 89, 458–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Guo, F.M.; Li, S.Y.; Chen, J.G.; Zeng, S.L.; Yang, Y.J. Investigation of the generation of high-order harmonics through Bohmian trajectories. Phys. Rev. A 2012, 86, 033424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Li, S.Y.; Liu, X.S.; Guo, F.M.; Yang, Y.J. Investigation of atomic radiative recombination process by Bohmian mechanics method. Phys. Rev. A 2013, 88, 053419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Yang, Y.; Guo, F.; Li, S. Revisiting the time-dependent ionization process through the Bohmian-mechanics method. J. Phys. B 2017, 50, 095003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Einstein, A. Bietet die feldtheorie Möglichkeiten für die Lösung des Quantenproblems? Sitzungsberichte der Preussischen Akademie der Wissenschaften 1923, 359–364. [Google Scholar]

- Leggett, A.J. Nonlocal hidden-variable theories and quantum mechanics: an incompatibility theorem. Found. Phys. 2003, 33, 1469–1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egg, M. The foundational significance of Leggett’s non-local hidden-variable theories. Found. Phys. 2013, 43, 872–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branciard, C. Bell’s local causality, Leggett’s crypto-nonlocality, and quantum separability are genuinely different concepts. Phys. Rev. A 2013, 88, 042113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laudisa, F. On Leggett theories: a reply. Found. Phys. 2014, 44, 296–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branciard, C.; Brunner, N.; Gisin, N.; Lamas-Linares, A.; Ling, A.; Kurtsiefer, C.; Scarani, V. Testing quantum correlations versus single-particle properties within Leggett’s model and beyond. Nat. Phys. 2008, 4, 681–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gröblacher, S.; Paterek, T.; Kaltenbaek, R.; Brukner, Č.; Żukowski, M.; Aspelmeyer, M.; Zeilinger, A. An experimental test of non-local realism. Nature 2007, 446, 871–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).