1. Introduction

Along with Madagascar and Tanzania, Indonesia is listed as one of the countries that produce the most clove (

Syzygium aromaticum (L.) Merr. & Perry) in the world [

1,

2,

3]. According to Siringoringo et al. [

1], although its production is low, it has the largest harvest area. Then Kabote [

4] and Kusuma et al. [

5] said that clove is one of the spices that has a high value. Additionally, according to Cahyani et al. [

6] and Lestari et al. [

7], clove is one of Indonesia's most important non-oil and gas commodities. This crop contributes to a rise in the total amount of money available to the government [

8,

9]. Clove is a significant crop in Indonesia, as stated by Mahulette et al. [

10] and Riptanti et al. [

11]. This is primarily because they contribute to the country's income and foreign exchange through the excise tax levied on cigarettes. Cloves are also very important to Indonesian farmers because most cloves (98%) are cultivated by smallholders [

3,

12]. The main yield of clove plants is flowers harvested while still in bud [

3,

13]. In addition, cloves also have considerable health benefits, and they are used by the pharmaceutical industry, cosmetics, and others [

1]. In fact, in Indonesia, cloves have been used for generations as traditional medicine [

14]. Cloves also contain an important chemical compound called eugenol. The content of eugenol in clove oil is 75-90% [

2,

15]. In addition to its prospective applications as an analgesic, local anesthetic, and antimicrobial agent, this chemical is exploited as an antibacterial, antifungal, insecticide, and antioxidant [

14]. Additionally, it is used to treat pain. Moreover, it is acknowledged as a material that can be used as a starting point for the creation of synthetic vanillin [

2].

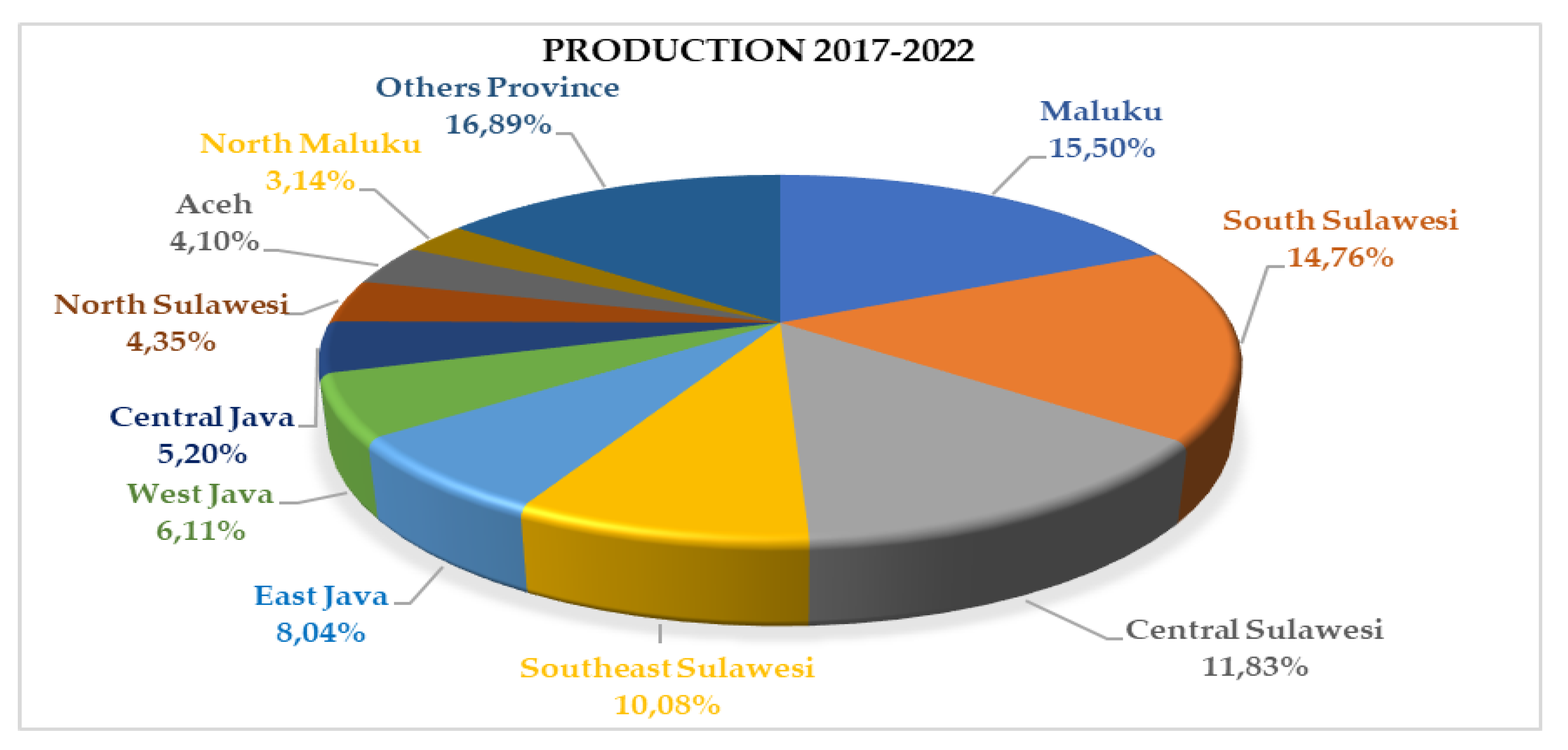

Clove cultivation is now widespread throughout Indonesia. However, based on currently available statistical data, it is known that ten provinces in Indonesia are the largest centers of clove production. This information can be seen in

Figure 1, based on average clove production data for 2017-2021. The clove center provinces are Maluku, South Sulawesi, Central Sulawesi, Southeast Sulawesi, East Java, West Java, Central Java, North Sulawesi, Aceh, and North Maluku. The ten provinces contributed a cumulative 83.11% to Indonesia. The main center of cloves is Maluku province, which has an average production of 20.73 thousand tons or contributes 15.50% annually to Indonesia. The second rank is occupied by South Sulawesi, which has an average production of 19.73 thousand tons or contributes 14.76% per year. The average production of cloves in Central Sulawesi, Southeast Sulawesi, and East Java was 15.82 thousand tons, 13.48 thousand tons, and 10.76 thousand tons, respectively. Meanwhile, the next five provinces have an average production below 10 thousand tons. The provinces of clove production centers in Indonesia are presented in detail in

Figure 1 [

16].

Based on

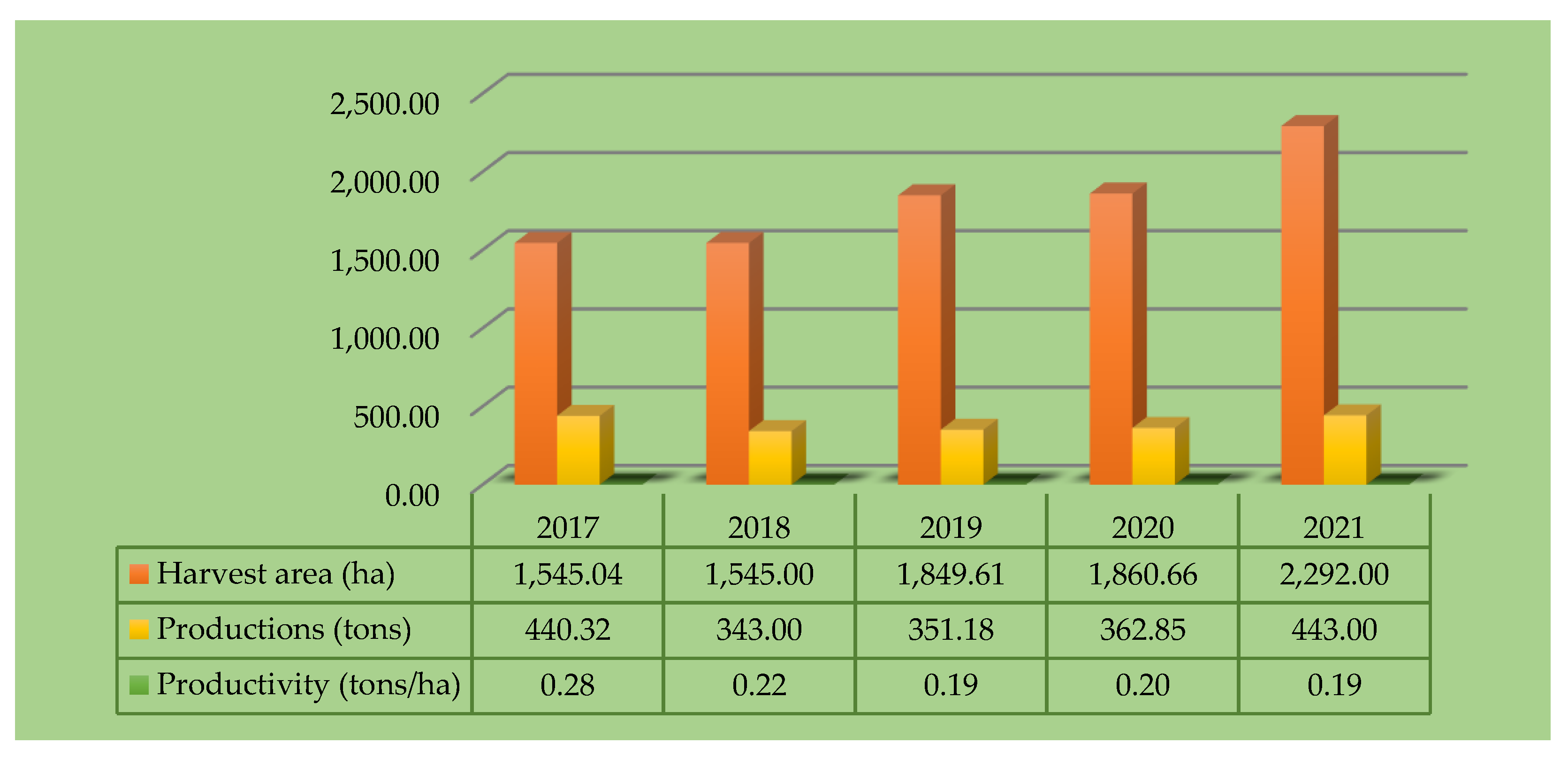

Figure 1 above, South Sulawesi Province is the second largest producer of cloves after Maluku. Even though it is in second place, this empirical fact is an important indicator that the clove commodity in South Sulawesi Province has considerable potential to support the plantation subsector development program. Based on data on the area of clove plantations in 2021, South Sulawesi Province has a land area of 67,337.00 hectares with a production of 21,431.00 tons [

17]. Furthermore, the Sidrap Regency, located in the South Sulawesi Province, is listed as one of the locations that cultivates cloves. Fig. 2 illustrates the harvest area, production, and productivity of cloves in the Sidrap Regency for 2017-2021. As shown in

Figure 2, the harvest area of clove farming continuously increased from 2018 until 2021. This is based on the data that was supplied. After reaching 1,545 hectares in 2018, the harvest area in Sidrap Regency was constantly expanded to 1,849.61 ha in 2019, 1,860.66 ha in 2020, and 2,202.00 ha in 2021. Meanwhile, from 2017 until 2021, there have been different fluctuation levels in this commodity's production. These situations, the rise in harvest area, and the fluctuation in productivity of this commodity were interesting facts to explore further.

Theoretically, the achievement of increased clove production in Sidrap Regency cannot be separated from the role of agricultural extension workers, who are the source of information for farmers in extension activities, starting from maintenance, fertilization, and harvesting materials [

18,

19,

20]. Extension agents are responsible for providing farmers with the information and education services they demand [

21,

22]. Extension agents are responsible for agricultural extension in a technical and administrative sense [

23,

24,

25,

26,

27]. The ultimate objective of agricultural extension is to enhance companies' productivity, efficiency, and effectiveness and enhance their income and welfare. Agricultural extension is also carried out as a response to the issues that farmers have in farming that are adapted to the advancement of science and technology [

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34]. This is done to address the challenges that farmers face. Addressing the problems that farmers face is done to provide solutions. Moreover, agricultural extension workers are required, according to Khairunnisa et al. [

35], Darmawan [

36], and Suratini et al. [

37], to develop their capacity to make use of high-tech agricultural equipment to increase their production yields to assist farmers in their farming. Extension workers need to have their capabilities and quality increased in many areas of education and training to increase the level of competence and motivation of extension workers' performance [

38,

39,

40]. Extension workers must also adopt extension strategies adapted to meet farmers' needs [

41,

42,

43]. Extension workers put in greater effort to develop methods, media, and materials, as well as to increase their knowledge and abilities in diverse sectors [

27,

44,

45,

46,

47,

48] to demonstrate that the extension program is effective and for an increase in knowledge, an increase in skills, and a change in attitude in the proper management of their farms [

25,

44,

49,

50,

51]. Therefore, it is expected that an agricultural extension worker will be able to create a strong work plan and provide counseling to farmers depending on the requirements of their targets [

52]. As a result, there must be genuine cooperation and common goals between farmers and the government to overcome all the challenges that farmers face[

53]. To accomplish the goals of the extension program, it is necessary to have a high level of extension potential and efficacy[

23,

54,

55].

The prior explanation and description gave a belief and impression that agricultural extension significantly enhances agricultural production and productivity. As a result, this research aimed to examine the factors influencing the effectiveness of agricultural extension in clove farming in Sidrap Regency, Indonesia. It was expected that the findings of this study would serve as an essential policy foundation for the efforts being made to increase the production and productivity of clove farming.

2. Literature Review

Agricultural extension is a key instrument in the development of agriculture. The Indonesian government has implemented various strategies, including individual, group, and mass, to improve the effectiveness of agricultural extension. The same is true for the information sources used as extension media. Farmers no longer rely solely on print media for information in the digital age. However, social media and the internet have grown in prominence, and they are now the principal extension media used by farmers. The literature study revealed four key aspects hypothesized to influence the effectiveness of agricultural extension: farmer characteristics, agricultural extension approaches, farmer information sources, farm characteristics, and capital. We then further elaborated on each of these aspects.

2.1. Farmer Characteristics

2.1.1. Effect of Farmer Age, Educational Attainment, and Family Size on Agricultural Extension

The success of agricultural extension in improving the productivity and welfare of farmers cannot be separated from the various characteristics they have. Generally, a person is most productive when aged between 15 and 64. A farmer is most optimal in carrying out his agricultural tasks at that age in maximizing his work productivity [

56]. Sumekar et al. [

57] and Ullah et al. [

58] added that people have the ability, understanding, and concentration to absorb information none other than productive age. Farmers of productive age are faster at accepting and understanding training material than farmers of unproductive age. In addition, a farmer's formal education also affects learning activities to increase knowledge skills and change one's attitude [

59]. In addition, elderly farmers may be more open to implementing sustainable agricultural methods since they have amassed more expertise and knowledge over time [

60]. Furthermore, education can change a person's thinking mindset to reason about knowledge, thus influencing decision-making, problem-solving, and taking action [

51,

61], absorbing, interpreting, and applying new information, and adopting better farming techniques [

62]. Next, the findings of a study by Windani et al. [

63] and Mizab [

61] demonstrated that individuals who have completed higher levels of education are more open to receiving knowledge, information, and ideas from others. The conclusions of the research led to the discovery of this piece of information. Previous studies have shown that the degree of education farmers have is crucial in deciding the implementation of a new invention. This is the conclusion that can be drawn from the findings of these studies. A study by Azizah and Sugiarti [

64] discovered that farmers who had completed higher levels of education had a more comprehensive understanding, which made it simpler for them to embrace new technology. Education has a significant impact, both directly and indirectly, on the effectiveness of agricultural extension workers, as stated by Arifianto et al. [

65]. Education is another factor that plays a significant role in determining the effectiveness of agricultural extension workers. Furthermore, it not only stimulates the engagement of participants in training activities but also plays a vital role in determining the level of success that a training program achieves in knowledge transfer [

66].

Moreover, the number of family dependents in a household is highly tied to the amount of needs a family has, both in terms of their bodily and spiritual wants. According to Jamil et al. [

59], Aniagyei et al. [

51], and Ullah et al. [

58], a person who has high family needs may also be motivated to use all of his knowledge and talents to perform work outside of his normal employment with the hopeful expectation of being rewarded with additional financial compensation. Then, Salukh et al. [

67] said that one of the primary reasons for household members to assist the head of the household in working for revenue is the number of family members who rely on the head of the household. This is one of the reasons why the head of the household is supported in working. Salukh et al. [

66] also noted this. It has been found that the bigger the number of family members that are reliant on a home, the greater the incentive to work more, which in turn helps them to work more efficiently [

58]. In addition, Atube et al. [

68] and Ndamani [

69] stated that it is reasonable to anticipate that increasing the number of family members dependent on the family's income will assist in better appreciating the acceptance of extension innovations. This is a belief that is grounded on possibility. Then, Nabila et al. [

70] said that farmers are driven to spend moron their day-to-day expenses, and many family members are reliant on them. This is because farmers are responsible for providing for their families. Agricultural workers are accountable for providing for their families, which is the reason for this. The family size variable has a significant and unfavorable impact on the degree to which people are willing to adopt innovations that extend their reach, according to researchers Berhanu et al. [

71].

2.1.2. Effect of Farming Experience and Farmer Cosmopolitan on Agricultural Extension

According to Oktafiani et al. [

72], farmers who have been working in farming for a long time tend to be more skillful at making decisions that follow their specialized knowledge and capabilities. This is a result of the fact that they have more relevant experience. Moreover, Malila et al. [

73] observed that the length of time that farmers have spent working in the agricultural industry is directly proportionate to the level of competence and skills they possess in terms of using their knowledge and talents in every farming activity. This statement is consistent with the findings of Kotur [

74] and Darmawan [

36], who explained in their research that the amount of work experience an individual has substantially influenced their performance.

Farmers' cosmopolitan ability is the ability to orientate outside the area of a farmer to establish broad interpersonal relationships [

75]. Farmers' activities outside the village measure cosmopolitan interactions with people outside the village [

76,

77]. In addition, cosmopolitan is also measured by a farmer's activities outside the village or to related institutions, such as the extension center, the agriculture office, the Agricultural Technology Assessment Center (BPTP), and universities to seek information about supporting facilities for their farms [

76]. The results showed that the cosmopolitanity of farmers was in the low category because farmers rarely sought information outside their village [

78]. The distance between the village and the information center and the difficulty in accessing public transportation make farmers reluctant to seek information on their own [

76]. Farmers prefer to utilize their time for gardening and wait for extension workers who come to visit their village to receive information related to their farm [

76]

2.2. Agricultural Extension Approaches: Effects of Individual, Group, and Mass Communication Approaches on Agricultural Extension

This individual communication approach is intended for farmers who receive special attention from field extension workers. The individual approach extension method is implemented to inform farmers by conducting individual communication [

79]. Additionally, individual communication comprehensively addresses an issue with farmers and provides them with answers[

80]. This communication is done per the level of trust developed with the farmers so that they can discuss the issue, according to the findings of the study, which concluded that these data reveal that individual approaches, such as extension methods with home visits, land visits, informal connections, and inquiry techniques, have various effects on farming operations. However, some research findings suggested that different approaches can affect farming operations. According to Ramadhana [

79] and Fangohoi et al. [

45], the group approach method is also utilized to target farmer groups in the context of agricultural practices. This is in addition to approaching things individually, which is typically observed. Group counseling is carried out routinely and scheduled following the program by extension workers and the agricultural office [

81]. Then, Saputra [

81] and Tumurang et al. [

79] added that the group method (lecture) is the most economical method to convey information and knowledge verbally about the benefits and importance of innovation in farming. The research results show that the group method approach has a significant impact because farmers can apply an innovation and development program to support their farming activities [

82]. The general populace, often known as the public, is the target audience for the aforementioned transmission of information. Under Ramadhana [

79], agricultural extension workers can convey information to farmers frequently situated in rural towns and communities.

Furthermore, the findings of Tumurang et al. [

80], Imran et al. [

83], and Azumah et al. [

84], mass communication is one of the tactics that can be utilized to effectively transmit information to a large number of targets in a short time. Extension workers can accomplish this. Furthermore, this is consistent with what was mentioned in the statement before this one. Tambo et al. [

85], as a preliminary attempt to manage fall armyworm, the data indicated that there was a substantial association between exposure to campaign channels (either independently or in combination) and better knowledge. This was the case regardless of whether the campaign channels were used individually or in combination.

2.3. Farmer Information Sources

2.3.1. Effects of Print, Electronic, and Social Media on Agricultural Extension

Print media is a means of mass media that is printed and published periodically, such as books, brochures, and leaflets used by extension workers in conveying information to farmers who need it so that farmers can read books, pamphlets, and leaflets repeatedly so that they can be well understood [

86,

87]. The results showed that extension workers used print media to support consecutive extension activities, namely books/literature, brochures, leaflets, tabloids, and technical instructions [

88,

89]. In contrast to the findings of Jaya [

90] and Munthali et al. [, the multimedia website portal is one of the effective platforms for delivering information to the public, farmers, and other related parties. The results of this study show that the agricultural extension website portal provides significant benefits to the community and farmers so that people can easily access the latest information on agricultural techniques, crop management, fertilization, pest and disease control, and sustainable agricultural practices [

92]. In addition, audio-visual media is also a series of electronic images equipped with audio sound elements and images expressed through video tapes. In agricultural extension materials, electronic media, such as radio, LCD, slides, VCD, and television, is used by farmers to receive information [

27,

44,

48,

77]. Then, the material presented in the media contains materials that farmers need to support better farming [

77,

93]. The results of this study also show that farmers' attitudes toward the extension media are in the acceptance category. According to farmers, the media (audio-visual) delivered by extension workers has used the right media. In line with this opinion, Cummins et al. [

94] stated that the videos used were designed to engage agricultural workers and raise farmers' awareness of extension activities [

95,

96].

Furthermore, the utilization of social media in agricultural extension activities demonstrates that the utilization of social media in extension activities has been frequently carried out. It can favorably impact the extension's precision, efficiency, and effectiveness to increase agricultural productivity [

91,

97]. This is demonstrated by the utilization of social media in extension activities. This is illustrated by the fact that extension efforts have been carried out using social media. This is a demonstration of this. According to the views expressed by Safitri et al. [

98], it is of the utmost importance for extension operations to utilize social media to disseminate extension materials, training, and various forms of socialization. This is deemed significant to the extent that it may be used to locate and provide information related to agriculture. According to a study that was carried out by Humaidi et al. [

99] and Suratini et al. [

37], it has been established that the use of social media platforms like WhatsApp, Facebook, Instagram, and YouTube has an impact on the knowledge and behavior of farmers who are employed in agricultural extension. The scientific literature assembled has these findings, which are documented there. Following the results of a research project that was carried out by Humaidi et al. [

99], it is feasible to utilize social media as a learning medium and a source of information concerning agriculture. This is because agricultural extension uses a wide variety of social media platforms. However, while social media can help agricultural extension, several obstacles prevent agricultural extensionists from using it as a tool. These include the age of farmers, inadequate internet networks, farmers unfamiliar with technology, and some farmers who do not yet own an Android [

100].

2.3.2. Effect of Clove Cultivation Material on Agricultural Extension

Extension materials are a collection of information and knowledge developed to assist farmers in improving their yields and farming efficiency [

101,

102]. It delivers information, training, and education to farmers on best practices in crop cultivation, pest and disease control, natural resource management, and agricultural technology innovation [

22,

34,

103,

104]. Agricultural extension materials aim to educate farmers to adopt modern sustainable farming techniques, increase their productivity and income, and promote economically, socially, and environmentally sustainable agricultural development.

Clove cultivation is a series of human activities in managing plants, starting from land management, planting, maintenance, and harvesting [

34,

105,

106]. Clove is a refreshing plant cultivated in several patterns, including monoculture and polyculture. According to Le et al. [

107], monoculture farming is simpler and yields a single plant species as large as possible. This is accomplished without considering the possibility of crop failure due to attacks from pests and disorders. According to Lele et al. [

107], polyculture leads to increased profits from a wider variety of crops, and even if one crop commodity is discounted, other commodities are still available. According to Nuthall [

108], this is an essential requirement for the membership of the farming community inside the agricultural system. A crucial necessity is the need for highly quality, relevant, and practical agriculture information. Information about agriculture plays a key role in educating them, increasing their level of knowledge, and ultimately supporting them in decision-making that involves activities related to agriculture.

Farmers stated that extension services helped them overcome frequent challenges that they had in farming, which is relevant to the topic at hand. According to Danjumah et al. [

109], Sujianto et al. [

34], and Gebremariam et al. [

39], this statement indicates that extension services can respond to the practical issues that farmers experience and offer them answers that would help them improve their farming methods. The findings of Adamu et al. [

110] and Baah [

111] study, which suggested positive perceptions as it increases information credibility, indicate that extension services efficiently serve the information demands of farmers by ensuring factual accuracy, expert validation, and alignment with existing knowledge. This is because the study shows that extension services promote information credibility. This was evidenced by the fact that the evaluation revealed favorable perceptions exhibited by the participants. This is true repeatedly. This statement is consistent with the study's findings, which suggests that it is accurate. The data demonstrated that farmers had favorable attitudes toward extension services, indicating this statement is correct. This assertion agrees with the findings of the research that was carried out. As stated by Nuthall [

109], extension services are an essential resource for farmers since they enable them to contribute to developing their capabilities and assist in applying sustainable agricultural methods. The total beneficial impact of extension services exemplifies the success of extension services as a valued resource for farmers.

2.3.3. Farm Characteristics and Capital: Effect of Land Area and Capital on Agricultural Extension

The term "land used for crop cultivation" refers to a location utilized for agricultural crop production. The amount of cultivated land that farmers manage influences the amount of output and income that farmers obtain from the farms and farms that they operate, as stated by Akbar et al. [

112], Marding et al. [

113], and Sujianto et al. [

34]. This is the conclusion that can be drawn from the research conducted by many researchers. This is the case because farmers are directly involved in land management. The conclusion can be drawn from the data of both of these investigations because the outcomes of both of these investigations allow for it. The findings of several previous research [

35,

53,

61,

114] have proven that the variable of land area has been shown to impact the total amount of agricultural production significantly. Furthermore, this impact has been proven to be favorable. The researchers who carried out the research made this fascinating discovery. Thus, the increase in land area will be followed by increased clove production [

113]. Furthermore, Alberth [

49] and Sujianto et al. [

34] argue that the variable characteristic of respondents with a significant relationship with extension participation is the farm size with a strong correlation. In contrast to this, Habun et al. [

115] stated that partially, the land area variable did not significantly affect clove production. This finding is due to, among others, the fact that the land used by farmers is intercropped, so the land area has no significant effect on clove production [

116].

Another factor that plays a role in producing more complicated farming methods is the availability of financial financing. The terms "fixed capital" and "current capital" are used collectively to refer to these two categories of capital. Capital that can be replenished in the short term is called current capital [

117]. Examples of current capital include seeds, fertilizers, pharmaceuticals, labor, and other commodities. In contrast to current capital, which may be replenished immediately, fixed capital is secured by land, agricultural equipment, buildings, and other assets. Agricultural capital, which includes land area, labor, the application of fertilizers and pesticides, and farming instruments and machinery, is said to affect the effectiveness of agricultural extension, as stated by Jamil et al. (2023). According to Jamil et al. [

24] and Sujianto et al. [

33], the quantity of money a farmer has is directly proportionate to the amount of human resources.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Construction of Conceptual Framework

Research variables, including independent and dependent variables, are defined in behavioral studies to help conceptualize and organize research methods. These are the goals behind the creation of research variables. In the context of a specific research activity, a "variable" is anything, event, entity, or characteristic that changes in value and is intended to be researched, measured, reported, and assessed [

118]. We refer to them as variables because the word suggests that they are. Kerlinger [

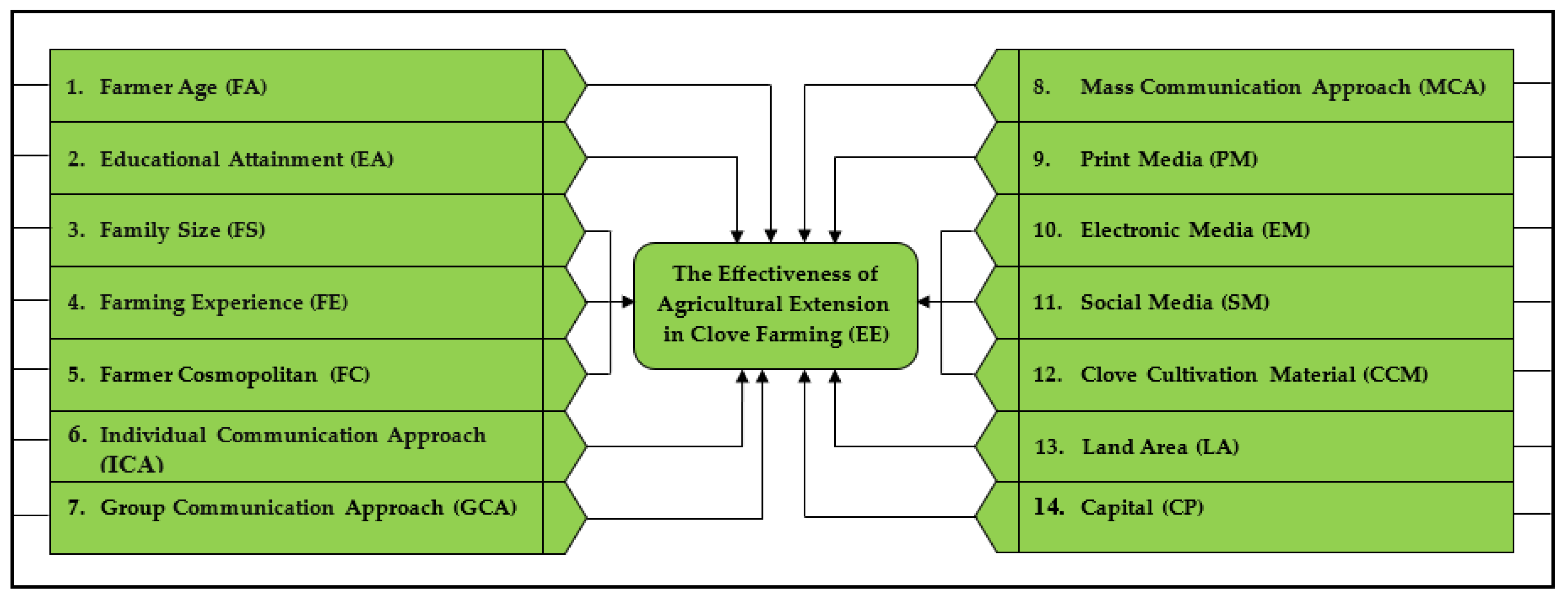

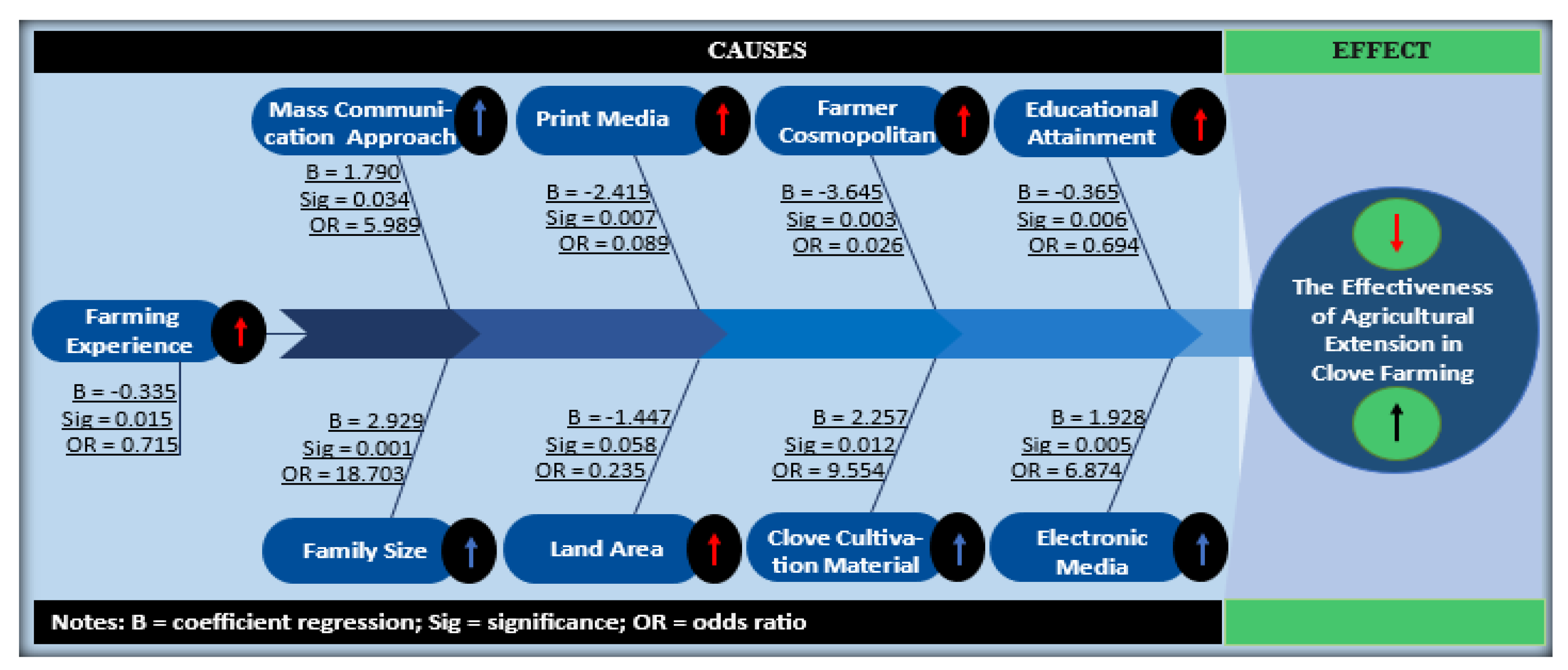

119] defines variables as entities that can take on many values. It is equally important to note this definition. We utilize dependent variables to measure attribute behavior in response to changes to one or more independent factors. To acquire a full grasp of the variables used and discussed in this study, we divide them into two categories: dependent variables and independent variables. How the data in the independent variables affect the dependent variable's behavior is interdependent. We selected to analyze the characteristics that reflect this study's independent variables to understand better their link with the dependent variable, extension efficacy. This conclusion was taken based on the previous literature study, which we refer to as the conceptual framework shown in

Figure 3. We predicted the 14 independent variables shown in

Figure 3 to be the most important predictors of the effectiveness of agricultural extension in clove farming.

3.2. Research Site, Data Collection Method, and Research Sample

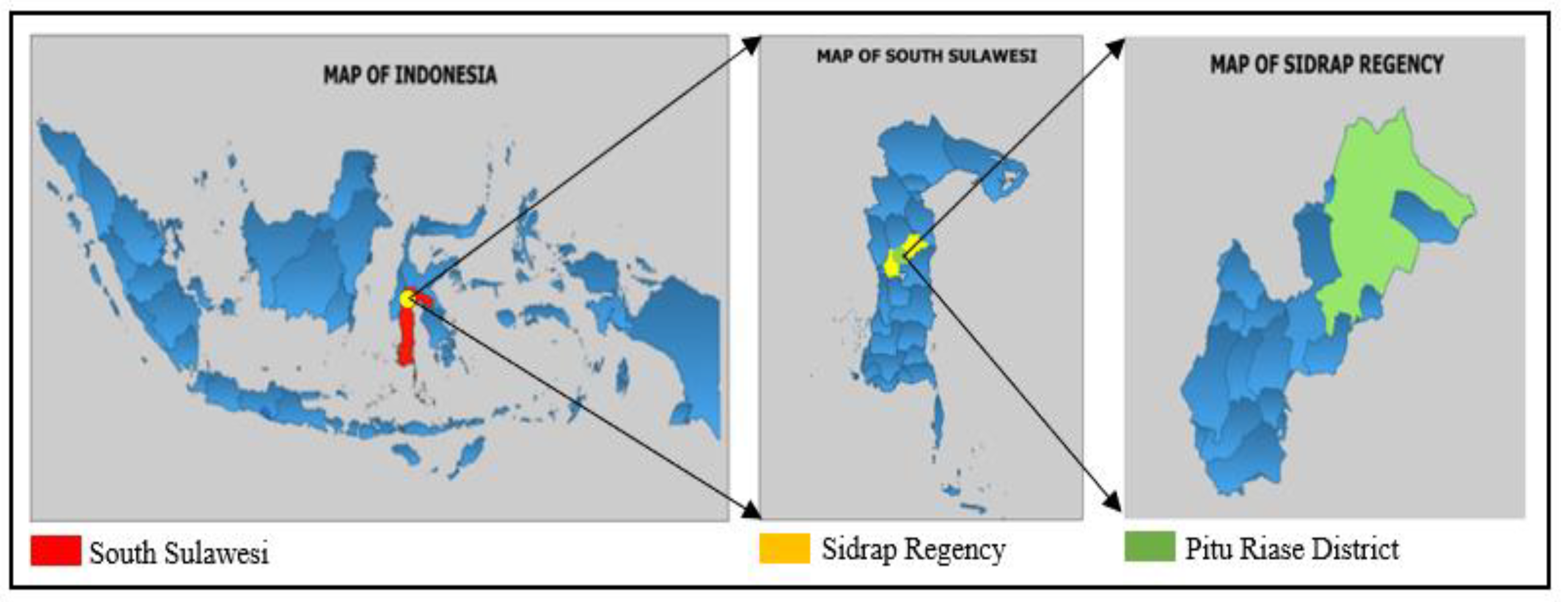

This study was conducted in the Pitu Riase District, Sidrap Regency, in the South Sulawesi Province of Indonesia (

Figure 4). In 2020, the Bureau of Statistics (BPS) estimated that 23,350 farmers in the Pitu Riase District were cultivating clove crops. Compong Village, Leppangeng Village, Dengeng-dengeng Village, Buntu Buangin Village, and Belawae Village were the five villages in the Pitu Riase District from which we collected primary data. Because they were the most critical clove-producing communities in the district, we decided to focus on these five villages, with the primary selection criteria comprised of farmers who had grown clove crops during the year 2023. One hundred forty clove farmers were selected randomly and interviewed directly for this study. The number of samples collected during the research was adequate to accurately depict the population of clove growers in the Sidrap Regency. We employed a pre-developed questionnaire to gather primary data and performed structured interviews. Before conducting the interview, each respondent who participated in the research provided informed consent about the research objectives, methods, benefits, and publication purposes. Then, this study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Institutional Review Board (Local Government) of Pitu Riase District of the Sidenreng Rappang Regency Government via Permit Letter No. 800/136/Kec.Pitu Riase.

3.3. Binary Logistic Regression Analysis

3.3.1. General Model of Binary Logistic Regression

A regression model is a statistical method applied to determine independent variables' influence on what is considered a dependent variable, as stated by Tampil et al. [

120] and Getu [

121]. This method is utilized to determine the relationship between the two variables. Through the utilization of the regression model, it is possible to succeed in accomplishing this purpose. There are several various kinds of regression models. However, the linear regression model, which is represented by Equation (1), is the one that is considered to be the most fundamental of all of them.

where:

Y = dependent variable; X1-n = independent variables; β0 = constant; β1-n = regression coefficient.

According to Tampil et al. [

120], the binary logistic regression model analyzes the interaction between a single response variable and several predictor variables. This is the objective of the model. This examines the possible connection between the variables. The response variable is provided as dichotomous qualitative data, where 1 indicates the presence of a characteristic, and 0 indicates the absence of a personality trait. In other words, a value can be either positive or negative. That is to say, the response variable can either be there, or it can be gone. Furthermore, Tampil et al. [

120] said that the binary logistic regression model is typically utilized when the response variable creates two categories with values of 0 and 1. This is the situation at any time when the response variable produces data. Equation (2), a representation of the Bernoulli distribution, is adhered to by this model throughout its entirety when used.

where:

πi = probability of the i-th event;

yi = i-th random variable consisting of 0 and 1.

Then, a logistic regression model with one predictor variable is used, as in Equation (3) [

120,

121,

122].

To facilitate the interpretation of regression parameters,

π(

x) in Equation (3) is transformed, resulting in the logit form of logistic regression [

120], as presented in Equation (4).

3.3.2. Empirical Model

The empirical model was created concerning Equations (3) and (4) to examine the influence of 14 independent variables and their relationship to the dependent variable, Extension Effectiveness (EE), as demonstrated in Equation (5).

where:

g(EE) = Effectiveness of agricultural extension on clove farming (1 = effective, 0 = otherwise); β0 = Constant; FA= Farmer Age (year); EA= Educational Attainment (years); FS = Family Size (people); FE = Farming Experience (year); FC = Farmer Cosmopolitan (5Points-Likert Scale); ICA = Individual Communication Approach (5Points-Likert Scale); GCA = Group Communication Approach (5Points-Likert Scale); MCA= Mass Communication Approach (5Points-Likert Scale); PM = Print Media (5Points-Likert Scale); EM = Electronic Media (5Points-Likert Scale); SM = Social Media (5Points-Likert Scale); CCM = Clove Cultivation Material (5Points-Likert Scale); LA = Land Area (ha); CP = Capital (IDR); and = Error terms.

A variable is a property, attribute, or characteristic of a person, item, or scenario that exhibits the ability to vary or change, as stated by Marudhar [

123]. Variables can be found in a variety of contexts. There are many different settings in which variables can be found. Variables can be found in a person, an object, or a circumstance. A character, trait, or attribute can be defined as a variable depending on the context. The primary purpose of a study conducted in social science is frequently to understand the causal relationships between distinct social situations. This is the case when the research is being undertaken. This is the case in a significant number of instances. Investigating the influence that one or more independent factors have on the variable that is the subject of the investigation is one of the actions that must be completed in this process. When discussing a cause-and-effect relationship, referring to the theorized result as the dependent variable is standard practice.

On the other hand, the independent variable is often referred to as the postulated cause throughout the context of this relationship. It is essential to understand that a variable does not always have the status of either an independent or a dependent variable. This is something that must be in place. Given this, it is not out of the question for a variable regarded as independent in one investigation to be utilized as the dependent variable in another investigation. Salam et al. [

124] considered including variables in the study hypotheses. They stated that three main techniques may be applied to deal with the phenomenon. These ways are described in the following sentence. A variety of approaches are available to deal with the circumstances. The first thing that must be done to assess the impact of the independent variables on the dependent variable is to draw comparisons across groups based on the independent variables. This is the first step in the process. In the second step of the process, one or more independent variables are linked to one or more dependent variables to establish a connection. Describe the responses to the independent variables, the variables that act as mediators, or the dependent variables. The third step is performing this step in the process of data analysis.

As provided in

Table 1, this study investigated the relationship between 14 independent variables and a dependent variable. Following that, we ensure that each variable has a measurement unit. We have also effectively identified and classified the variables into two unique groups: continuous and categorical data types.

A temporary solution to a problem is one definition of a hypothesis in the field of research [

125]. These are only a few of the definitions. The formulations used to express hypotheses might be either easy or particularly sophisticated. Most researchers engage in quantitative research activities to confirm the first hypothesis rather than attempt to find a solution to the problem. It is, therefore, vital for a researcher to have a firm knowledge of the significance and nature of the hypothesis that was established at the beginning of a research activity. This is because the hypothesis was developed at the start of the research endeavor. One of the goals of establishing a research hypothesis is to either draw and analyze the logical inferences of causal linkages or to foresee causal correlations between variables that have been observed [

126]. Both of these objectives are important in the research process.

Following a similar pattern to what we did in the previous session, we conducted a literature review to generate predicted hypotheses, hypothesis statements, and significant outcomes for each independent variable in the study. The study's findings are presented for your perusal, which can be found in

Table 2. The statistics shown in

Table 2 make it abundantly clear that the independent variables anticipated to be significant in this inquiry are, in fact, significant findings. The number of family members, the mass approach, electronic media, clove cultivation supplies, and capital are some aspects that might be considered. Education, time spent working in agriculture, cosmopolitan farmers, print media, and the size of the land are some of the factors that negatively influence the outcome. As a result, it is possible to conclude that the elements of farmer age, individual approach, group approach, and social media do not significantly impact the effectiveness of agricultural extension concerning clove cultivation.

3.3.3. Parameter Estimations

The Maximum Likelihood Estimation (MLE) approach is a potential solution that could be applied when estimating unknown parameters. The most fundamental form of this strategy provides the anticipated value of β intending to maximize the likelihood function. Equation (6) is where one may find the likelihood function for the binary logistic regression model [

120,

121,

122,

124,

127]. For more information, see the references listed below. An organized approach can be used to demonstrate this.

where: y

i = observation on the i-th variable;

= odds for the i-th predictor variable.

To facilitate the calculation, a log-likelihood approach is taken as in Equation (7) [

121], [

122], [

123], [

125], [

128].

To get the value of the interpretation of the logistic regression coefficient (β̂) is done by making the first derivative of L(β) against β and equating it to 0.

3.3.4. Logistic Regression Model Test

The Likelihood Ratio Test is useful for determining whether each predictor influences a particular model. This evaluation may be carried out with the assistance of the test. The accomplishment of this goal is not only possible but also attainable. There is a potential that could be utilized in this situation. This analysis can be used to satisfy the requirements associated with the analysis. The Likelihood Ratio Test is a statistical method that analyzes the ratio between the probability of observing data assuming a particular parameter is zero (L

0) and the probability of obtaining data when the parameter is evaluated at its MLE (L

1). This ratio is referred to as the likelihood ratio. This particular ratio is known as the likelihood ratio ratio. Research conducted by Tampil et al. [

120] and Park [

122] all came to the same conclusion. This particular ratio is known as the likelihood ratio ratio. To ascertain this ratio, it is necessary to initially assess the probability of detecting data while operating under the assumption that the parameter is negative. Equation (8), found in other places, contains a mathematical explanation of the G-Likehood Ratio Test. This explanation can be found in the Equation. Research conducted by Salam et al. [

124], Yuniarsih et al. [

127], Rusliyadi et al. [

128], and Getu [

121] indicate that.

where:

n1 = number of observations in category 1;

n0 = number of observations with category 0.

A chi-square distribution is utilized to determine the test statistic G. The value of the χ2 table is compared to the degree of freedom (db) = k-1, where k is the number of predictor variables. This comparison is carried out to determine the degree of freedom. This enables the decision to be made when necessary. The null hypothesis (H0) is rejected whenever the value of G is more significant than χ2 (db, α) or the p-value is lower than α.

3.3.5. Partial Hypothesis Test

Based on the model that has been obtained, partial testing is utilized to investigate the impact of each αi individually. There is a possibility that a predictor variable could be added to the model, and the results of a partial test will show whether or not this is doable. Concerning each variable, the following is the hypothesis that was utilized:

H0 : i = 0

H1 : i = 0

The Wald test statistic (WST) can be seen in Equation (9). Then, Equation (10) is a way to obtain the standard error estimator value of βi [

120,

122,

124,

127,

128].

and

where:

SE () = estimated standard error for coefficient

= expected value for a parameter

Because the ratio generated by the Wald statistic agrees with the standard normal distribution, comparing it with the standard normal distribution (Z) is essential to arrive at a specific recommendation. If the W value exceeds Z α/2 or the p-value is lower than α, the null hypothesis (H0) is rejected.

3.3.6. Interpretation of Binary Variable Coefficients

An odds ratio is a set of odds divided by other odds. The odds ratio coefficient shows a person's tendency to do or not do an activity. The odds ratio equation (ψ) is presented in Equation (11) [

30,

121,

124,

127,

128,

130].

Under the assumption that the value of ψ is equal to 1, it is possible to conclude that there is no relationship between the two variables. If the value of ψ is less than 1, it signifies a negative link between the two variables and the category change of the value of x. In contrast, if the value of ψ is greater than 1, there is no association of this kind.

4. Results and Discussions

4.1. Results of Binary Logistic Regression Analysis

4.1.1. Cox & Snell R-Square and Nagelkerke R-Square Tests

This study employed the Cox & Snell R-Square and Nagelkerke R-Square tests to assess the impact of independent variables, including farmer age, years of education, family size, years of farming experience, cosmopolitanism, individual approach, group approach, mass approach, print media, electronic media, social media, clove cultivation resources, land area, and capital, on the dependent variable of extension effectiveness.

Table 3 presents the outcome of the Nagelkerke R-Square statistic, which was found to be 0.760. As demonstrated in this figure, the independent variables in the study provided 76.0 percent of an explanation for the dependent variable of extension effectivity in clove farming. The remaining 24.0 percent of the explanation is derived from other independent variables that were not incorporated into the model that was examined.

4.1.2. Likelihood Ratio Test (LRT)

The LRT test is utilized to determine whether or not the model is appropriate for that particular circumstance. The omnibus test table can also be referred to in another way: by comparing the estimated Chi-square value with the Chi-square table and the significant value with a critical threshold of 5%. The estimated Chi-square value of 83.376, as presented in

Table 4, is concurrently more than the Chi-square table value of 23.685. Then, since the significance value in the table is 0.000, which is less than the threshold of 0.05, the null hypothesis (H

0) is rejected. Because of this, we can say that the null hypothesis was rejected. This rejection was carried out according to the decision rule that says H

0 is rejected at a significant level α if G is more than the Chi-Square (χ2 (α, v)) value and the significance value in the test statistic is less than α. This finding establishes a causal relationship between the dependent variable and one or more independent factors.

4.1.3. Partial Test (Wald Test)

The Wald test is just one example of the many different forms of significance tests available. There are many other kinds of significance tests. One way that may be applied to finish the estimation of the parameter β is to square the quotient of the parameter estimate with the standard error by using this method. In light of this, the conclusion that can be drawn from the estimation is as follows. Consequently, the Wald test is a type of significance test that can be carried out. Whenever a variable is incorporated into the model, this test is carried out before the beginning of the model. The decision-making criteria are applied in this test, and a significant threshold of α = 0.05 is utilized. If the significance value is found to be less than α or if the value of

W is found to be greater than χ2 (α, df), then the null hypothesis (H

0) is rejected at a level of significance α, as seen in

Table 5.

The significance threshold is 0.05, and the degree of freedom is 1; the chi-square table exhibits a value of 3.481. This number serves as evidence that the findings are statistically significant. The degree of freedom is set to 1, which leads to the value one obtained as a consequence. Furthermore, based on the Wald test results presented in

Table 5, it is known that the variables of educational attainment (EA), family size (FS), farming experience (FE), farmer cosmopolitan (FC), mass communication approach (MCA), print media (PM), electronic media (EM), clove cultivation materials (CCM), and land area (LA) had a statistically significant effect on the effectiveness of extension in clove farming (EE). Based on these findings, it was discovered that the projected test values for these variables were more than the critical value of 3.481 that was generated from the Chi-square table. By presenting evidence, the findings of the Wald test can be utilized to support the conclusion that was initially stated. As a result, it is feasible to conclude that the variables are statistically significant at a level lower than 0.05 by using this information. The conclusion reached was that both H

0 and H

1 were rejected, with H

1 being accepted. While the other independent variables, such as the farmer age (FA), the individual communication approach (ICA), the group communication approach (GCA), social media (SM), and Capital (CP) did not have a significant impact on the efficiency of agricultural extension in clove farming (EE).

Equation (12) is the binary logistic regression model equation formed in this research. The equation derived from

Table 5 contains the results of the Wald test, which were significant variables in the model tested.

4.1.4. Model Fit Test

The Hosmer and Lemeshow Test is a method that can be applied within the framework of binary logistic regression to evaluate the degree to which the data corresponds to the model. The Chi-square value also can be utilized in this test. This evaluates the degree to which the data is consistent with the model. This makes it possible to determine the degree to which the model and the facts are compatible with one another or not compatible with one another. The findings of the comparison of the model to the data are presented in

Table 6, which is one of the conclusions that arose from this inquiry.

A value of 1.944 was obtained for the Chi-square statistic, and 0.983 was obtained for the significance evaluation. Both of these values were obtained. In a separate investigation, both of these values were discovered. This conclusion was arrived at considering the model fit test outcomes shown in

Table 6. A computation was performed using the Chi-square table; the result is the number 15.507, which is the result of the computation. For the sake of this computation, the significance level was established at 0.05, and the degree of freedom was established at 8. Even though the significance value (0.983) is greater than the alpha level that was computed earlier (0.05), the estimated Chi-square value (1.944) is lower than the crucial Chi-square value (15.507). This is because the alpha level was calculated earlier. This is because the value of the crucial Chi-square is much higher than the value of the significance threshold. It is possible to conclude that there is no statistically significant difference between the observed and those predicted in light of these modifications.

4.2. Interpretation of the Odds Ratio

A quantitative depiction of the connection between a causative component and the associated effect can be accomplished by the computation of the odds ratio, denoted by the expression OR/Exp(B). Chen et al. [

131] and Ospina et al. [

130] concluded that it allows researchers to explore whether the likelihood of an occurrence is the same or different between two distinct groups of people from various backgrounds. According to Chen et al. [

131] and Ospina et al. [

130], the value of the ratio might be anywhere from zero to infinity. Then, the graphical summary of variables that significantly affected the effectiveness of agricultural extension in clove farming is presented in

Figure 5. The regressed results of this research will then be interpreted using

Figure 5, shown in the following section.

4.2.1. Farmer Characteristics

In this study, the independent variable of educational attainment (EA) will be examined for its effect on the effectiveness of agricultural extension in clove farming (EE). As presented in

Figure 5, this variable was significant in the model tested. Its significance value of 0.006 was less than the alpha value of 0.05. Meanwhile, the odds ratio value for the EA variable was 0.694, with an estimated value (B) of -0.365. This figure indicated a negative influence of the EA variable on the effectiveness of agricultural extension in clove farming (EE). Based on this value, it was reasonable to believe that the time a farmer has spent obtaining an education could diminish the effectiveness of agricultural extension in clove farming. This conclusion was not at all difficult to come to. We argued that the farmers who devote more time to formal schooling have lower levels of motivation and interaction in the agricultural sector. As a result, they experience less success in managing their farms. This finding is in line with the research of Tham-Agyekum et al. [

132], who found that this perception would decrease, comparable to the results of previous studies. There is no significant difference between the results of this examination and those of that study. Both the findings of this inquiry and the conclusions of the other study that was carried out agree with one another. On the other hand, the findings of Azizah [

64] show that the level of education that farmers possess would impact the decisions they make regarding implementing a new invention they are considering. The findings presented here are in direct opposition to those presented earlier. Higher education provides a more comprehensive understanding, which makes it simpler for farmers to accept innovations. Moreover, Arifianto et al. [

65] indicated that the level of education possessed by extension workers substantially impacts their overall performance capabilities. There is still a lack of clarity regarding the reason for this inverse link, which may call for additional research.

Moreover, the study looked at the family size (FS) variable to see how much it affects the effectiveness of agricultural extension in clove farming (EE). This variable significantly affected the EE variable, whose significance value was 0.001

(Figure 5). This figure was less than the 99% significance level (α = 0.01). Then, the estimated value (B) for the family size (FS) variable was 2.929, and the odds ratio (OR) value for the variable was 18.703. These specific figures concluded that the FS variable positively impacted the EE variable. These figures also indicated that there was a possibility that an increase in family size (FS) could have increased the efficiency of agricultural extension in clove farming. In other words, the likelihood of agricultural extension being successful is increased when there is a greater number of family members who are dependent on the farm. This finding is in line with the research of Suvedi et al. [

133] and Aniagyei et al. [

51], which stated that one of the factors affecting farmers' participation in agricultural extension is family resources, which relate to the division of tasks in the household. Therefore, farmers who have many family resources will help implement extension programs. The findings of Khalid [

134] asserted that extension activities aim to improve the efficiency of farming families, raise productivity, and generally improve the living conditions of farming families. This suggests that increasing the dependent family's size will help better understand the acceptance of extension innovations [

68,

69]. Moreover, Nabila et al. [

70] argue that farmers are compelled to spend moron their day-to-day expenses if more family members depend on them. This is because farmers are responsible for providing for their families. On the other hand, compared to the findings of Berhanu et al. [

71], which suggests that the family size variable significantly and negatively influences the acceptability of extension innovations. The findings of this study indicate that the opposite is true.

This study also investigated the effect of the farming experience (FE) variable on the effectiveness of agricultural extension in clove farming (EE). In

Figure 5, we found that the significance value of this variable was 0.015. This variable significantly affected the EE variable because the value was less than the alpha value of the significance level of 95% (α=0.05). Meanwhile, the odds ratio of the FE variable was 0.715, with an estimated value (B) of -0.335. This value indicated a negative effect of the FE variable and the agricultural extension's effectiveness on clove farming. Based on this value, we can conclude that the farming experience variable had a negative impact on the effectiveness of agricultural extension in clove farming. There is a possibility that the effectiveness of agricultural extension could decline as farming time grows. Another thing is that experienced farmers find agricultural extension less effective. In reality, we can explain this phenomenon. A farmer with more experience managing his clove farm would no longer be interested in agricultural extension. Consequently, he would experience a significant reduction in the influence of agricultural extension activities. The findings obtained in this study were consistent with the conclusions obtained in previous studies. Hassan et al. [

135] stated that the amount of time spent on farming was a significant factor that became a barrier in the agricultural extension process. The evidence for this is that some farmers have been in the farming business for a considerable time, and it may be difficult to convince them to abandon their traditional farming practices in favor of more contemporary farming methods. This is one of the basic explanations for the phenomenon. On the other hand, contrary to the findings of [

35], [

71], and [

73], it has been found that farmers who have a long history of farming experience have a considerable beneficial impact on the effectiveness of extension.

Moreover, the independent variable of farmer cosmopolitan (FC) was examined to see how much it affected the effectiveness of agricultural extension in clove farming (EE). This variable was a significant one that influenced the EE variable. Its significance value (0.003) was less than the alpha value of 0.01 or the 99% significance level. At the same time, the FC variable had an odds ratio (OR) of 0.026 with an estimated value (B) of -3.645. This figure indicated that the farmer's cosmopolitan variable had a negative effect on the EE variable. We can conclude that as the number of cosmopolitan farmers increases, the effectiveness of agricultural extension in clove farming may diminish. The result of this study was in line with the research of Yusliana et al. [

78] and Utami [

76], who explained that cosmopolitan farmers were included in the low category because farmers rarely seek information outside their village. Furthermore, added by Setiyowati et al. [

76] and Utami [

77], the distance between the village and the information center and the difficulty in accessing public transportation causes farmers to be reluctant to seek information on their own, farmers spend more time gardening and waiting for extension workers or guests who come to visit their village to receive information related to their farm.

4.2.2. Agricultural Extension Approaches: Effects of Mass Communication Approaches (MCA) on the Effectiveness of Agricultural Extension in Clove Farming (EE)

Regarding the effectiveness of agricultural extension in clove farming (EE), we also explored how the independent variable of the mass communication approach (MCA) impacts clove farming's effectiveness. A significant value of 0.034, less than the alpha value of 0.05, was reported for the MCA variable concerning its effect on the EE variable in the data shown in

Figure 5. At the same time, it was discovered that the odds ratio (OR) for the MCA variable was 5.989, while the estimated value (B) was determined to be 1.790. This depiction of the data demonstrates that the MCA variable had a large and positive influence on the EE variable. Considering the observed facts, predicting that any new mass communication approach (MCA) in extension might make agricultural extension work more effectively for clove growing is feasible. It has been determined from the study's findings that increasing the adoption of mass communication methods has the potential to improve the effectiveness of agricultural extension. This is one of the techniques that is used to transmit information extensively from extension workers to a large number of targets in a short length of time, as stated by Tumurang et al. [

80], Imran et al. [

83], and Azumah et al. [

84]. Mass extension is one of the strategies that is employed. Utilizing mass extension is how this objective is attained. Representatives from both research groups announced their findings to the public. A considerable degree of congruence was discovered between the outcomes of this study and the conclusions of the research that Ramadhana [

79] carried out. Both sets of findings were shown to be associated with one another. The results of the study conducted by Tambo et al. [

85] indicate that exposure to campaign and mass channels, either on their own or in combination, has a large and beneficial influence on the effectiveness of agricultural extension. This was discovered through the findings of the research that was carried out. This conclusion may be reached based on the findings of the group's inquiry.

4.2.3. Farmer Information Sources

The electronic media (EM) variable was also investigated in this study to determine its influence on the effectiveness of agricultural extension in clove farming. This variable was one of the independent variables that substantially affected its dependent variable (EE), as seen in

Figure 5. This may be noticed by looking at the graph. The magnitude of the significance value, which was 0.005, was lower than the alpha value, which was 0.05. The electronic media variable's odds ratio (OR) value was 6.874, while the estimated value (B) was 1.928. This value indicates a positive effect of the electronic media (EM) variable on the variable of EE. This figure showed that any increase in the use of electronic media as a source of information could increase the effectiveness of agricultural extension in clove farming. It can be concluded that the electronic media variable had a considerable and beneficial influence on the effectiveness of agricultural extension in clove farming if this value was considered. When this statistic is considered, it is reasonable to assert that the growing exploitation of electronic media could increase the efficiency of agricultural extension to a greater extent. The findings of this study were consistent with the findings of other studies, such as [

27,

44,

48,

77,

93], which asserted that the content presented in the media contained materials that farmers specifically required to encourage improved farming. In addition, as a result of the findings, which demonstrated a beneficial influence of media factors (audio-visual) on extension, farmers believed that disseminating information through electronic media was suitable [

94,

95,

96].

Furthermore, the print media (PM) variable was examined to see how much it affected the effectiveness of agricultural extension in clove farming (EE). In

Figure 5, the PM variable significantly affected the variable EE. Its significance value of 0.007 was less than the alpha value of 0.05 for the significant level of 95%. Meanwhile, the print media (PM) variable had an odds ratio (OR) of 0.089 and an estimated value (B) of -2.415. This figure showed a negative effect of the PM variable on the effectiveness of agricultural extension in clove farming. This value can be assumed to mean that any increase in the use of print media as a source of information can hamper the effectiveness of agricultural extension in clove farming. This is a conclusion that is possible to draw. Since some farmer respondents were literate while others were illiterate, printed media such as books, brochures, and leaflets that extension workers utilize as information media are less successful. Al-Zahrani et al. [

50] and Anyanwu [

88], who stated that research findings confirm this finding, indicated that the findings verify this finding since it was the case. According to the conclusions of the research, this finding is supported by the evidence. Evidence suggests that farmers in the region under investigation do not have access to formal education, which ultimately makes it more difficult to employ more efficient agricultural practices.

This research also examined the effect of clove cultivation material (CCM) on the agricultural extension effectiveness variable in clove farming (EE). The CCM variable was significant in the model tested, as presented in

Figure 5. The significance value was 0.012, less than the alpha value of 0.05. In the meantime, the CCM variable had an odds ratio (OR) of 9.554 and an estimated value (B) of 2.257. This figure demonstrated a positive and significant influence of the clove cultivation material (CCM) variable on the effectiveness of agricultural extension in clove farming. The interpretation of these figures is that increasing clove farming material could potentially improve the effectiveness of agricultural extension. The basis for this conclusion was that farmers who learned more about clove production practices would be more successful in managing their clove farming. This finding was corroborated by a study conducted by Nuthall [

108], which demonstrated that agricultural information needs have a significant part in illuminating individuals, raising their level of knowledge, and eventually assisting individuals in decision-making about agricultural operations. The fact that this is the case implies that extension services address the practical difficulties that farmers experience and provide them with options to improve their farming methods [

39,

109]. Extension services can effectively satisfy the information needs of farmers, as stated by Baah [

111], Sujianto et al. [

34], and Mariel et al. [

106]. This is accomplished by ensuring that the material is factually accurate, vetted by experts, and linked with the already available knowledge. When the credibility of the content is improved, the research findings indicate that favorable attitudes are displayed as a consequence of the development of the credibility of the information. According to Nuthall [

108], extension services are an essential resource for farmers since they enable them to contribute to developing their capabilities and assist in implementing sustainable agricultural methods. Extension services are extremely valuable as a resource for farmers, and their total influence highlights their importance.

4.2.4. Farm Characteristics: Effect of Land Area (LA) on the Effectiveness of Agricultural Extension in Clove Farming (EE)

The land area (LA) variable was one of the significant variables in the model tested in this research. The significance value of this variable was 0.058, which is less than the significant level value of 90% (α=0.10). Meanwhile, the odds ratio (OR) for the LA variable was 0.235, with an estimated value (B) of -1.447. Since this value was negative, it was clear that the land area variable had a negative impact on the effectiveness of agricultural extension in clove farming (EE). Given these data, it was reasonable to assume that the effectivity of agricultural extension will decrease in proportion to the increase in land area. This was a realistic assumption to make. The findings of this study were consistent with the findings of prior research. According to Tham-Agyekum et al. [

132], those with smaller land sizes tend to favor extension services more favorably. There could be various reasons for this finding, including that farmers with smaller or bigger land holdings have different requirements or may see the services as more customized to their particular circumstances [

136]. However, in contrast to this study, it states that land size has a positive and significant correlation with extension effectiveness, as seen from the increase in knowledge, skills, and changes in farmers' attitudes to increase their farm production [

35,

53,

112,

113,

114]. Furthermore, Alberth [

49] argued that land area characteristics are closely related to agricultural extension participation.

5. Conclusions and Recommendations

This research objective was to examine the factors influencing the effectiveness of agricultural extension in clove farming in Sidrap Regency, South Sulawesi Province, Indonesia. This study used primary data from structured interviews with 140 clove farmers as sample respondents. These sample farmers were selected using a simple random method. Then, the data collected were analyzed using binary logistic regression (BLR) to test the influence of fourteen independent variables on the effectiveness of extension in clove farming as the dependent variable. The fourteen independent variables tested in this study were farmer age (FA), education attainment (EA), family size (FS), farming experience (FE), farmer cosmopolitan (FC), individual communication approach (ICA), group communication approach (GCA), mass communication approach (MCA), print media (PM), electronic media (EM), social media (SM), clove cultivation materials (CCM), land area (LA), and capital (CP). Furthermore, based on the BLR regression results, it was found that simultaneously, the fourteen independent variables significantly affected the effectiveness of agricultural extension in clove farming. Then, from the partial test results, it was found that the variables of family size (FS), mass communication approach (MCA), electronic media (EM), and clove cultivation materials (CCM) had a positive-significant effect on the effectiveness of extension in clove farming (EE). While the independent variables of education attainment (EA), farming experience (FE), farmer cosmopolitan (FC), and print media (PM) had a negative-significant effect on the EE variable. The results of this study, especially the variables that have a positive-significant effect, are important indicators and valuable findings in spurring and encouraging the effectiveness of extension in clove farming. The positively-significant variables can be used to determine the implications of the conceptual framework of clove farming managerial in the short and long term. Similarly, the five variables that have a negative-significant effect.

Based on the findings presented above, the conclusion of the research emphasizes the significant role that family characteristics, approaches in agricultural extension services, and methods of communication play in the dissemination of technology and enhancing the effectiveness of agricultural extension when it comes to the delivery of extension material and programs to farmers. The findings from the preceding sections suggest that policymakers should prioritize increasing the amount of information they teach on how to cultivate cloves, increasing the frequency with which they use mass extension methods, and increasing the amount of electronic media they use in extension activities in the research locations. It is because of this that extension services will become increasingly helpful. In addition, the provision of extension services is significantly impacted by the provision of resource support from the national government. It is crucial to provide farmers and other stakeholders in rural regions with the appropriate information and services to enhance their lives and promote sustainable agriculture. Agricultural extension and consulting services are essential in this regard. We anticipate that the effectiveness of agricultural extension in clove production will be improved due to these measures.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H., M.S., and M.H.J.; Software, H.; methodology, H., M.S., and M.H.J.; formal analysis, H., M.S., and M.H.J.; validation., H., M.S., and M.H.J.; investigation, H., M.S., and M.H.J.; resources, H., M.S., and M.H.J.; data curation, H., M.S., and M.H.J.; writing-original draft preparation, H., M.S., and M.H.J.; writing-review and editing, H., M.S., A.A.S., M.H.J., H.I., P.D., A.A., A.N.T., A., A.I.M.; visualization, H., M.S., and M.H.J.; project administration, H. and M.S.; funding acquisition, H., A.A.S., A.N.T., A., P.D., and A.I.M.; supervision, M.S., M.H.J., H.I., P.D., A.A., A.N.T., and A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research did not receive any funding from outside sources.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all participants involved in the study, and all primary data from the participants and the secondary data used in this study were approved by the local administration of Sidrap Regency and the Pitu Riase District Head. The study was carried out per the protocol approved by the Institutional Review Board (Local Government) of Pitu Riase District of the Sidenreng Rappang Regency Government via Permit Letter No. 800/136/Kec.Pitu Riase, dated October 17, 2023. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Data Availability Statement

The research data will be made available upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Siringoringo, V.V.M.; Bakce, D.; Dewi, N. Analyzing supply and demand response of Indonesian cloves in International market. Indonesia Journal Of Multydiciplinary Science 2023, 2, 2609–2625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triana, D.; Tafdilla, M.A.; Antika, L.D.; Ernawati, T. Conversion eugenol to vanillin: Evaluation of antimicrobial activity. ISETH 2019, 594–602. [Google Scholar]

- Suprihanti, A. Analysis of clove agroindustry in Indonesia as an alternative green industry; 2020; Vol. 4;

- Kabote, S.J.; Tunguhole, J. Determinants of clove exports in zanzibar: Implications for policy. International Journal of Business and Economic Studies 2022, 4, 127–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusuma, H.S.; Lantip, G.I. Al; Mutiara, X.; Iqbal, M. Evaluation of mini bibliometric analysis, moisture ratio, drying kinetics, and effective moisture diffusivity in the drying process of clove leaves using microwave-assisted drying. Applied Food Research 2023, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cahyani, A.D.; Dewatama, D.; Kamajaya, L. Implementasi fuzzy logic control pada alat pengering cengkeh otomatis. 2023.

- Lestari, N.A.P.; Bahari, B.; Abdullah, W.G.; Saediman, H. Institutions and partnership in clove farming development: A case of puulemo Village in Kolaka District of Southeast Sulawesi. International Journal of Research in Engineering, Science and Management (IJRESM). Vol. 6(12), 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Kembauw, E.; Mahulette, A.S.; Kakisina, A.P.; Tuhumury, M.T.F.; Umanailo, M.C.B.; Kembauw, M.G.I. Clove processing as a source of increasing business income in Ambon City. In proceedings of the Iop conference series: Earth and environmental science; Iop Publishing Ltd, October 29 2021; Vol. 883.

- Matital, G.; Roessali, W.; Dwi Yunianto, V. The influence of internal and external factors on entrepreneurship behavior. Agrisocionomics 2022, 6, 313. [Google Scholar]

- Mahulette, A.S.; Hariyadi; Yahya, S. ; Wachjar, A.; Marzuki, I. Morpho-Agronomical diversity of forest clove in moluccas, Indonesia. Hayati 2019, 26, 156–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riptanti, E.W.; Qonita, A.; Uchyani, R. Revitalization of cloves cultivation in central java, Indonesia. In proceedings of the Iop conference series: Earth and environmental science; institute of physics publishing, August 12 2019; vol. 314.

- Pratama, A.P.; Darwanto, D.H. ; Masyhuri economics development analysis journal Indonesian clove competitiveness and competitor countries in international market article information. Economics Development Analysis Journal 2020, 9, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasud, Y. Induksi kalus secara in vitro dari daun cengkeh (syizigium aromaticum l.) dalam media dengan berbagai konsentrasi auksin (in vitro callus induction from clove (syzigium aromaticum L.) leaves on medium containing various auxin concentrations). Jurnal Ilmu Pertanian Indonesia (jipi), Januari 2020, 25, 67–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradana, A.; santosa, d.; sulaiman, t.n.s. Potensi cengkeh (syzygium aromaticum (l.) Merr. & perry) di Indonesia sebagai sumber daya alam dan bahan baku obat antibakteri dan antijamur. Majalah Farmaseutik 2024, 20, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Ma, Y.; Liu, L.; Liu, Y.; Niu, X. Incorporation of clove essential oil nanoemulsion in chitosan coating to control burkholderia gladioli and improve postharvest quality of fresh tremella fuciformis. Lwt 2022, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siagian, V.J. Outlook komoditas cengkeh: Pusat data dan sistem informasi pertanian jenderal - kementerian pertanian cengkeh, 2022.

- Wahidin, A.; Helmy, A.; Sari, I.D.P. Provinsi Sulawesi Selatan dalam angka: Badan Pusat Statistik Provinsi Sulawesi Selatan, 2022.

- Rehatta, H.; Marasabessy, D.A.; Sopalauw, S.H. Produktivitas cengkih hutan (syzygium obtusifolium l.) Di Kecamatan Leihitu Kabupaten Maluku Tengah. Jurnal Budidaya Pertanian 2019, 15, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roswandy, N. Sosialisasi penanganan organisme pengganggu tanaman yang ramah lingkungan pada malam hari. Pattimura mengabdi : Jurnal Pengabdian Kepada Masyarakat 2023, 1, 55–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Septian, R.D.; Afifah, L.; Surjana, T.; Saputro, N.W.; Enri, U. Identifikasi Dan Efektivitas Berbagai Teknik Pengendalian Hama Baru Ulat Grayak Spodoptera Frugiperda J. E. Smith Pada Tanaman Jagung Berbasis Pht- Biointensif. Jurnal Ilmu Pertanian Indonesia 2021, 26, 521–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, B.; Mallick, B.; Roy, A.; Sultana, Z. Impact of agriculture extension services on technical efficiency of rural paddy farmers in Southwest Bangladesh. Environmental Challenges 2021, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danso-Abbeam, G.; Ehiakpor, D.S.; Aidoo, R. Agricultural extension and its effects on farm productivity and income: insight from Northern Ghana. Agric Food Secur 2018, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agustina, F.; Zahri, I.; Yazid, M.; Yunita. Determinant factors of agricultural extension competence in the implementation of good agricultural practices in Bangka, Belitung Province. Russ J. Agric Socioecon Sci 2017, 69, 231–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harper, A.; Mustafee, N.; Yearworth, M. Facets of trust in simulation studies. Eur J. Oper Res 2021, 289, 197–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamil, M.H.; Tika, N.; Fudjaja, L.; Tenriawaru, A.N.; Salam, M.; Ridwan, M.; Muslim, A.I.; Chand, N.V. Effectiveness of agricultural extension on paddy rice farmer’s Baubau City, Southeast Sulawesi, Indonesia. Sustainability (Switzerland) 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pongrácz, E.; Polonyová, S.; Poláčková, H. Development of educational activities and counseling in social agriculture in Slovakia: Initial experience and future prospects. European Countryside 2023, 15, 186–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putri, M.A.; Veronice; Ananda, G. Persepsi petani terhadap kompetensi penyuluh pertanian di Kecamatan Payakumbuh, Kabupaten Lima Puluh Kota. Jurnal Penyuluhan 2022, 18, 59–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahua, M.I. Efektivitas dan persepsi pelaksanaan penyuluhan pertanian pada masa pandemi Covid 19. Agrimor 2021, 6, 138–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]