Submitted:

23 January 2025

Posted:

24 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

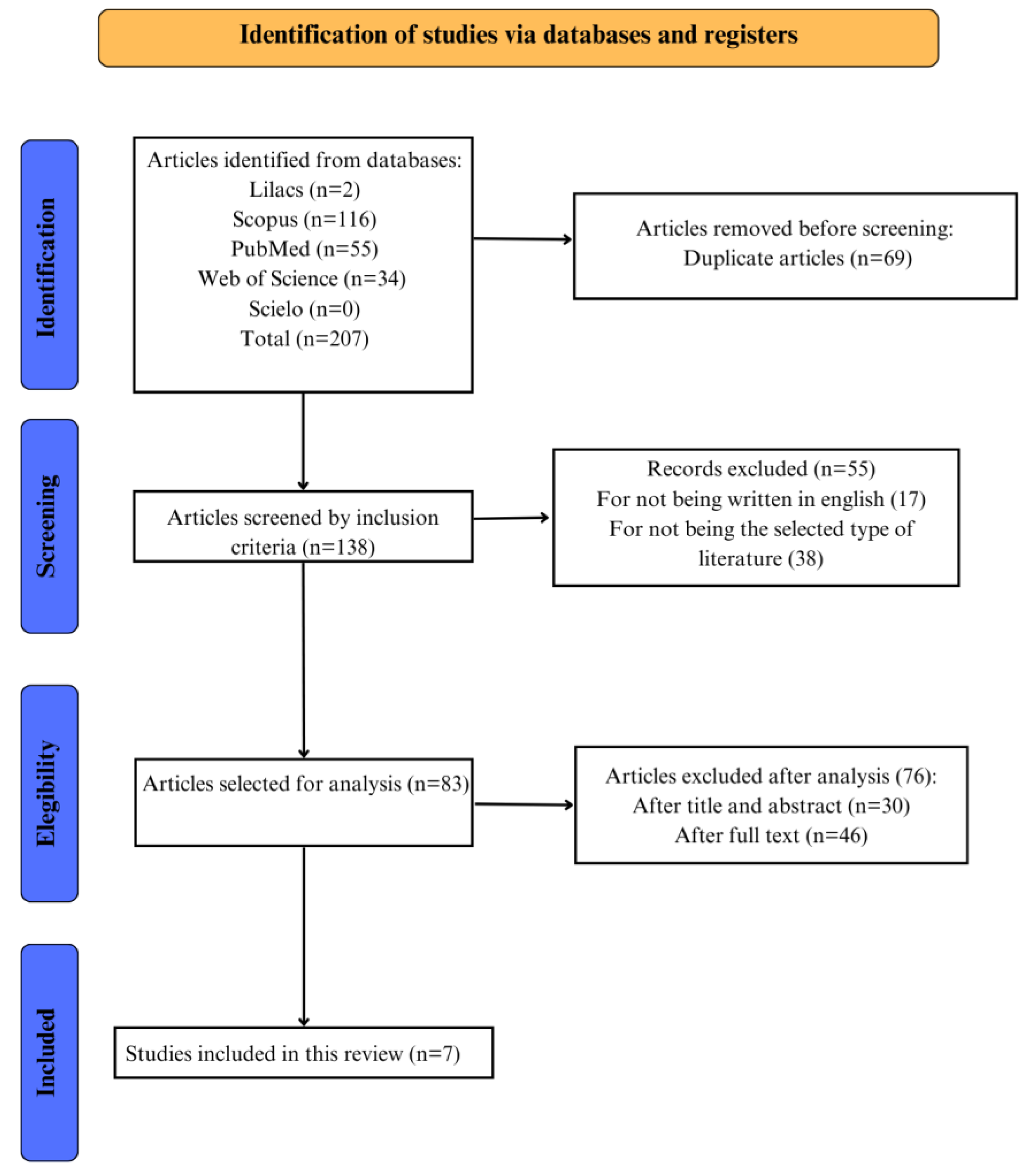

This study aims to review the literature and to investigate how prenatal and postnatal counseling interfere in subjects with Disorders of Sex Development (DSD). The articles were obtained through search on bibliographic databases: Web of Science, Scopus, Scielo, MEDLINE, and LILACS and selected using the guideline following the Joanna Briggs Institute scoping review protocol and answering. The search identified 181 articles. After the methodological screening, 7 studies were eligible for this narrative review. 16 cases of different types of DSD were evaluated in the studies. In this case, different types of prenatal and postnatal counseling were carried out to address the diagnosis. In most cases, prenatal counseling was based on a genetic point of view and postnatal was based on psychological and educational follow-up of the family. There are different manners to conduct prenatal and postnatal counseling in cases of DSD. However, the data shows that there is a lack of specific protocols for adequate counseling of patients and families in the context of DSD. In addition, previous studies have only described this aspect in superficial forms. Therefore, further investigations are necessary to establish a scientific protocol for this matter.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Funding

Data availability statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Z. Makiyan, “Studies of gonadal sex differentiation,” Organogenesis 12, no. 1 (January 2016):42-51. [CrossRef]

- K.T. Mehmood and R.M. Rentea, “Ambiguous Genitalia and Disorders of Sexual Differentiation,” In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing 1, no 28 (August 2024). PMID: 32491367.

- U. Lampalzer, P. Briken, and K. Schweizer, “Psychosocial care and support in the field of intersex/diverse sex development (dsd): counselling experiences, localisation and needed improvements,” International Journal of Impotence Research 33, no. 2 (March 2021):228–242. [CrossRef]

- E.Bennecke, K. Werner-Rosen, U. Thyen, et al., “Subjective need for psychological support (PsySupp) in parents of children and adolescents with disorders of sex development (dsd),” European Journal of Pediatrics 174, no. 10 (October 2015):1287–1297. [CrossRef]

- L.M. Carlson and N.L. Vora, “Prenatal Diagnosis: Screening and Diagnostic Tools,” Obstetrics and Gynecology Clinics of North America 44, no. 2 (June 2017):245-256. [CrossRef]

- L. Carbone, F. Cariati, L. Sarno, et al., “Non-Invasive Prenatal Testing: Current Perspectives and Future Challenges,” Genes (Basel) 12, no. 1 (December 2020):15. [CrossRef]

- S. Manzanares, A. Benítez, M. Naveiro-Fuentes, M.S. López-Criado, and M. Sánchez-Gila, “Accuracy of fetal sex determination on ultrasound examination in the first trimester of pregnancy,” Journal of Clinical Ultrasound 44, no. 5 (December 2015):272–277. [CrossRef]

- M. Kearin, K. Pollard, and I. Garbett, “Accuracy of sonographic fetal gender determination: predictions made by sonographers during routine obstetric ultrasound scans,” Australasian Journal of Ultrasound in Medicine 17, no. 3 (August 2014):125–130. [CrossRef]

- F. Mackie, K. Hemming, S. Allen, R. Morris, and M. Kilby, “The accuracy of cell-free fetal DNA-based non-invasive prenatal testing in singleton pregnancies: a systematic review and bivariate meta-analysis,” British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 124, no. 1 (May 2016):32–46. [CrossRef]

- J.F. Desforges, M.E. D’Alton, and A.H. DeCherney, “Prenatal Diagnosis,” New England Journal of Medicine 328, no. 2 (January 1993):114–120. [CrossRef]

- S.H. Garmel and M.E. D’Alton, “Diagnostic ultrasound in pregnancy: an overview,” Seminars in Perinatology 18, no. 3 (June 1994):117–132, PMID: 7973782.

- T.M. Crombleholme, M. D’Alton, M. Cendron, et al.,“Prenatal diagnosis and the pediatric surgeon: The impact of prenatal consultation on perinatal management,” Journal of Pediatric Surgery 31, no. 1 (January 1996):156–163. [CrossRef]

- M. Alimussina, L.A. Dive, R. McGowan, and S.F. Ahmed, “Genetic testing of XY newborns with a suspected disorder of sex development,” Current Opinion in Pediatrics 30, no. 4 (August 2018):548–557. [CrossRef]

- J.M. Heeley, A.S. Hollander, P.F. Austin, D.F. Merritt, V.G. Wesevich, and I.E. Amarillo, “Risk association of congenital anomalies in patients with ambiguous genitalia: A 22-year single-center experience,” Journal of Pediatric Urology 14, no. 2 (April 2018):153.e1–7. [CrossRef]

- Y. van Bever, I.A.L. Groenenberg, M.F.C.M. Knapen, et al., “Prenatal ultrasound finding of atypical genitalia: Counseling, genetic testing and outcomes. Prenatal Diagnosis 43, no. 2 (February 2023):162-182. [CrossRef]

- L.A. Lee, C.P. Houk, S.F. Ahmed, I.A. Hughes, “International Consensus Conference on Intersex organized by the Lawson Wilkins Pediatric Endocrine Society and the European Society for Paediatric Endocrinology. Consensus statement on management of intersex disorders. International Consensus Conference on Intersex,” Pediatrics 118, no. 2 (August 2006):e488-500. [CrossRef]

- M.D. Peters, C. Marnie, A.C. Tricco, et al., “Updated methodological guidance for the conduct of scoping reviews. JBI Evid Implement 19, no. 1 (March 2021):3-10. PMID: 33570328. [CrossRef]

- A.C. Tricco, E. Lillie, W. Zarin, et al., “PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation,” Annals of Internal Medicine 169, no. 7 (October 2018):467-473. [CrossRef]

- J.A. Indyk, “Disorders/differences of sex development (DSDs) for primary care: the approach to the infant with ambiguous genitalia,” Translational Pediatrics 6, no. 4 (October 2017):323–334. [CrossRef]

- H.R. Davles, L.A. Hughes, and M.N. Patterson, “Genetic counselling in complete androgen insensitivity syndrome: trinucleotide repeat polymorphisms, single-strand conformation polymorphism and direct detection of two novel mutations in the androgen receptor gene,” Clinical Endocrinology 43, no. 1 (July 1995):69–77. [CrossRef]

- P. Switalski, M. Cozzo, and C. Hartfield, “Gender Abnormality: A Prenatal Ultrasound Diagnosis,” Journal of Diagnostic Medical Sonography 19, no. 3 (May 2003):188–191. [CrossRef]

- G. Russo, A. di Lascio, M. Ferrario, S. Meroni, O. Hiort, and G. Chiumello, “46,XY karyotype in a female phenotype fetus: a challenging diagnosis,” Journal of Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology 25, no. 3 (June 2012):e77-9. [CrossRef]

- A.C. Radtke, C. Sauder, J.L. Rehm, and P.H. McKenna, “Complexity in the diagnosis and management of 45,X Turner Syndrome mosaicism,” Urology 84, no. 4 (October 2014):919-921. [CrossRef]

- C.Y. Chou, Y.C. Tseng, and T.H. Lai, “Prenatal Diagnosis of Cloacal Exstrophy: A Case Report and Differential Diagnosis with a Simple Omphalocele,” Journal of Medical Ultrasound 23, no. 1 (March 2015):52–55. [CrossRef]

- E.J. Richardson, F.P. Scott, and A.C. McLennan, “Sex discordance identification following non-invasive prenatal testing,” Prenatal Diagnosis 37, no. 13 (December 2017):1298-1304. [CrossRef]

- L. Mohnach, S. Mazzola, D. Shumer, and D. Berman, “Prenatal diagnosis of 17-hydroxylase/17,20-lyase deficiency (17OHD) in a case of 46,XY sex discordance and low maternal serum estriol,” Case Reports in Perinatal Medicine 8, no.1 (2019):20180009. [CrossRef]

| Databases and search descriptors selected according to PCC strategy | |

| Database | Search strategies |

| MEDLINE | (“Ambiguous Genitalia” OR “Disorders of Sex Development” OR “Sex Development Disorders”) AND (“counseling”) AND (“Prenatal Diagnosis” OR “Fetal Screening” OR “Prenatal Screening” OR “Postnatal diagnosis”) |

| WEB OF SCIENCE | (“Ambiguous Genitalia” OR “Disorders of Sex Development” OR “Sex Development Disorders”) AND (“counseling”) AND (“Prenatal Diagnosis” OR “Fetal Screening” OR “Prenatal Screening” OR “Postnatal diagnosis”) |

| LILACS AND SciELO | (“Ambiguous Genitalia” OR “Disorders of Sex Development” OR “Sex Development Disorders”) AND (“counseling”) AND (“Prenatal Diagnosis” OR “Fetal Screening” OR “Prenatal Screening” OR “Postnatal diagnosis”) |

| SCOPUS | TITLE-ABS-KEY ( ( "Ambiguous Genitalia" OR "Disorders of Sex Development" OR "Sex Development Disorders" ) AND ( "counseling" ) AND ( "Prenatal Diagnosis" OR "Fetal Screening" OR "Prenatal Screening" OR "Postnatal diagnosis" ) ) |

| Publication | Year | Country | Study Design | Participants | Objectives | Prenatal Conduct | Postnatal Conduct |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Davles et al. [20] | 1995 | UK | Retrospective | Three cases of CAIS in the same family | To evaluate the use of the polyglutamine and polyglyclne trlnucleotlde repeat polymorphlsms in the first exon of the androgen receptor gene for carrier status determination | A comprehensive screening strategy of the entire androgen receptor gene must be used to find the mutation in a new case of CAIS. | Once a CAIS diagnosis has been made the gonads were removed, if possible before puberty, because of the risk of malignancy |

| Switalski et al.[21] | 2003 | USA | Case Report | One case of a true hermaphrodite | To report a case of true hermaphrodite | Sonographic examinations were performed, and it was suspected that the fetus had ambiguous genitalia and clubfeet. | A) Laboratory tests ordered were 17-hydroxyprogesterone, testosterone, and karyotype; B) An abdomen and pelvic sonogram showed a well-formed uterus with no visualization of the ovaries; C) A cystourethrogram demonstrated a urethra elongated for a female with a vagina; D) The baby was also scheduled to have exploratory surgery for further evaluation, with the parents’ consent; E) A follow-up with a child psychologist and geneticist was scheduled |

| Russo et al.[22] | 2012 | Italy | Case Report | One case of 17BHSD3 deficiency (46, XY female) | To report a patient of 46, XY female pointing that although the principal hypothesis of diagnosis is CAIS other etiologies should be evaluated | A) The couple performed 5a-reductase (SRD5A2) and androgen receptor (AR) gene analysis on chorionic villi after genetic counseling; B) The analysis revealed no relevant mutation in these genes, and the couple decided to carry the pregnancy to term. | A) The parents were informed about the clinical situation, the natural history of the disease and the therapeutic options; B) According to the parent's consent, the child underwent bilateral gonadectomy to prevent virilization of the external genitalia at puberty. |

| Radtke et al.[23] | 2014 | USA | Case Series | Two Turner Syndrome patients who have 45, X mosaicism | To review 2 patients that illustrate the complexity of antenatal and postnatal management in Mixed gonadal dysgenesis Patient 1 presents a 45,X/46,X,i(Yp) karyotype and patient 2 a 45,X/46,X,idic(Yq) karyotype |

A) Patient 1 presented antenatally evidence of nuchal thickening on screening prenatal ultrasonography. Because of the mother’s history of 2 prior miscarriages, chorionic villus sampling was performed and revealed a anormal karyotype. Before, the parents received extensive counseling regarding the implications and management of a child with mixed gonodal dysgenesis; B) Patient 2 was the result of a term pregnancy that was induced at 39 weeks, without antenatally risk of genetic abnormality. | A) Based on the genetic analysis and physical findings, the patient 1 underwent diagnostic laparoscopy with left gonadectomy and right gonadal biopsy; B) The patient 2 underwent hypospadia repair and release of chordae at 9 months and subsequent second stage hypospadias repair and right laparoscopic gonadectomy at 15 months. Before, a left gonad biopsy was done; C) Close follow-up as the child grows will be imperative as the multidisciplinary team works with the family to determine genital reconstruction, management of the remaining ovary, and sex of rearing; D) It is critical that accurate and universally accessible counseling materials are available to providers and families in the antenatal period when diagnosis and management decision making is first discussed. |

| Chou et al.[24] | 2015 | Taiwan | Case Report | Fetus with anomalies including a protruding mass from umbilicus, absence of bladder, ambiguous genitalia, and bilateral renal hydronephrosis | To report a patient of cloacal exstrophy that mimics a simple omphalocele in the initial midtrimester ultrasound examination | A) Amniocentesis was performed, and the karyotype showed 46, XX. After comprehensive prenatal counseling, the parents decided to continue the pregnancy;B) No visualization of the bladder is one of the main findings in cases with cloacal exstrophy, special attention should be given to fetal lower abdominal cystic structures in order to differentiate them from a normally positioned fetal bladder; C) An experienced sonographer should be aware of the diagnosis of cloacal exstrophy if the prenatal ultrasound showed an abdominal protruding mass, absence of the bladder, and ambiguous genitalia; D) Fetal MRI led to early and complete identification of the spectrum of anomalies, and facilitated verification of these findings by subsequent sonography. | A) After delivery, the newborn with cloacal exstrophy requires a surgery of the bladder and associated structural repair, which one of the primary goals of repair is to maintain urine continence; B) A cosmetically acceptable and functional phallus can be achieved in 85% of patients; C) The affected newborns can also avail of more advanced neonatal care if they can be transferred early to or delivered in a tertiary medical center. |

| Richardson et al.[25] | 2017 | Australia | Case Series | Seven patients were derived from a cohort of pregnant women who attended a multi-site specialist prenatal screening and ultrasound service for non invasive prenatal testing by cell-free DNA analysis and mid-trimester fetal morphology assessment. | To characterize genotype-phenotype discordance identified in the routine clinical setting, and explore the associated diagnostic and counseling challenges | Patients could elect to terminate the pregnancy or not before counseling; B) Many patients may be overwhelmed by the volume and detail of complex genetic information they are receiving prior to the test being ordered which raises consideration around whether patient should opt-in or opt-out of sex chromosome analysis | There are significant benefits of early neonatal or childhood intervention in many of cases including surgical interventions, such as removal of potentially carcinogenic streak gonads, time-critical hormonal interventions and biochemical investigations that can help clarify diagnosis and management postnatally |

| Monach et al.[26] | 2019 | USA | Case Report | A fetus with Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome (SLOS) based on a significantly low estriol level on maternal serum screen (MSS). | To describe a diagnosis of 17-hydroxylase/17,20-lyase deficiency (17OHD), which was suspected based on low maternal serum estriol in the setting of 46, XY genitalia discordance. | A) The patient's image revealed female fetal anatomy and external genitalia, but the amniocentesis revealed a regular 46, XY karyotype with positive SRY FISH studies. MRI did not identify any male anatomical findings; B) The couple had appointments with Pediatric Urology, Pediatric Endocrinology, Psychology DSD team members, and the genetic counselor, who also serves as the coordinator of the DSD clinic; C) Due to uncertain prenatal sex assignment, a clearly outlined management plan was established, including avoiding pronouns at all points of care until the parents decided on sex assignment after birth. | A) After all prenatal counseling and the postnatal examination indicating that the baby had female anatomical genitalia, the family chose to crate the baby as a female gender; B) After this decision, long-term follow-up was recommended with Genetics, Endocrinology, Gynecology, and Psychology in the DSD clinic. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).