Introduction

Large language models (LLMs) are artificial intelligence (AI) systems trained on extensive textual data, allowing them to comprehend and interact with humans using natural language. Among these, the ChatGPT model GPT-4o was launched by OpenAI on May 13, 2024. As an optimized version of GPT-4, GPT-4o can process and generate text more quickly, and it has superior performance and accuracy in specific fields, such as law, medicine, and particular languages. It also has a better grasp of context, thus providing more accurate and relevant responses in complex dialogues.

ChatGPT has diverse applications in the medical field. AI can help doctors make more accurate diagnoses and provide personalized patient treatment plans via algorithms and machine learning techniques. It can be used in various contexts, including medical education, medical diagnosis, academic research, public health, precision medicine, and personalized healthcare [

1,

2,

3]. In medical education, ChatGPT can assist in identifying potential research topics and help scientists improve the efficiency and quality of review articles [

4]. In addition, it can help medical professionals stay informed about the latest trends and developments in their respective fields [

5].

Ensuring the equality of AI technology in medical education across different countries is crucial. Thus, bridging the digital and technological gaps between nations is necessary to avoid exacerbating social, economic, and educational inequalities, which can lead to disparities in opportunities, resources, and overall quality of life [

6]. In addition, language and cultural gaps are critical to address, especially in resource-limited areas. Language bias is a key challenge; for example, ChatGPT shows higher accuracy and response quality when answering medical questions in English than in Chinese [

7]. Traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) has a history spanning thousands of years. As a form of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM), TCM is a comprehensive medical system widely used in clinical practice. Many scientists have researched ChatGPT’s performance on national medical exams, but limited research exists on GPT-4o’s performance, specifically on TCM exam questions.

The aim of our research was to evaluate the differences in the abilities of ChatGPT’s various language model versions to effectively understand and answer questions regarding TCM knowledge. Additionally, we investigated whether AI’s comprehension of TCM knowledge exhibits language bias, potentially leading to disparities in medical education across languages. Through this study, we gain deeper insights into the potential and challenges of ChatGPT in the medical field, providing a reference for future research and development of AI applications in TCM.

Methodology

Research Instrument

Generative pre-trained transformers (GPTs) are a series of dialogue-based language models developed by OpenAI, a company specializing in AI research and implementation. We conducted tests using GPT-3.5, GPT-4, and GPT-4o in this experiment to compare the differences in understanding and answering questions related to TCM across these ChatGPT versions.

Data Sources

To become a licensed Chinese medicine practitioner in Taiwan, one must pass a two-stage national examination known as the Professional and Technical Senior Examination for Doctors of Chinese Medicine. Since July 2012, this exam has been divided into two parts: The first part tests basic medical knowledge of TCM, and the second part assesses clinical knowledge of TCM. Students in undergraduate and post-baccalaureate TCM programs are eligible to take the first exam upon completing and passing basic medical courses. After completing their internships, they can take the second exam. The national exams are held twice a year, in February and July.

The first stage of the exam primarily tests the examinees’ knowledge of basic medical principles and TCM theories, ensuring they possess the foundational knowledge required to become TCM practitioners. Therefore, we chose the first-stage exam as the benchmark for our experiment. This stage is divided into two subjects, Basic Chinese Medicine I (BCM I) and Basic Chinese Medicine II (BCM II), each consisting of 80 multiple-choice questions, all in traditional Chinese, totaling 160 questions. Each question includes a description and four options, with only one correct answer. In 2023, the subject “Chinese (composition and translation)” was removed from the first-stage exam. The total score is calculated as the average of the scores for each subject, and 60 or above is considered a pass.

BCM I includes questions on the history of Chinese medicine, the basic theories of TCM, the Huangdi Neijing (Inner Canon of the Yellow Emperor), and the Nanjing (The Classic of Difficult Issues). The Huangdi Neijing is the earliest existing traditional Chinese medical text, and the Nanjing is the first book to elucidate the complexities and essential points of the Huangdi Neijing, covering pulse diagnosis, meridians, organs, diseases, acupoints, and acupuncture techniques.

BCM II includes questions on Chinese materia medica, the formulas of TCM, and the processing of Chinese materia medica. Chinese materia medica is the study of TCM, focusing on basic theories and the sources, collection, properties, effects, and clinical applications of various medicinal materials. TCM formulas involve appropriate dosages, forms, and routes of administration. Finally, the processing of Chinese materia medica refers to the traditional pharmaceutical techniques used to process raw medicinal materials.

Study Design

We aimed to study the accuracy of different GPT models in the first stage of the national examination for TCM practitioners in Taiwan. Therefore, we sampled exam questions from six recent tests (examination period from July 2021 to February 2024), which were retrieved along with their answers from Taiwan’s Ministry of Examination query platform.

We collected 480 multiple-choice questions each from BCM I and BCM II (totaling 960 questions). These questions were input into the GPT-3.5, GPT-4, and GPT-4o models, resulting in a total of 2,880 test responses. Specifically, each question was input manually into the models (without any modifications) using a separate dialogue box to prevent context learning from affecting the interpretation of the questions (

Figure 1).

The answers generated by the models were recorded in Microsoft Excel and compared with the correct answers published by the examination authority to calculate the accuracy rates of each model. If a model generated more than one answer, we instructed it to select the most appropriate answer for recording. These answers were collected by July 8, 2024.

Statistical Analysis

We used Python (version 3.12.4, Python Software Foundation) within the Jupyter Notebook for data processing. We conducted a one-way ANOVA test to compare the means of the three models (GPT-3.5, GPT-4, and GPT-4o) and to determine whether statistically significant differences existed among their performances. In addition, Tukey’s honestly significant difference (HSD) test was conducted to identify their differences in accuracy.

Results

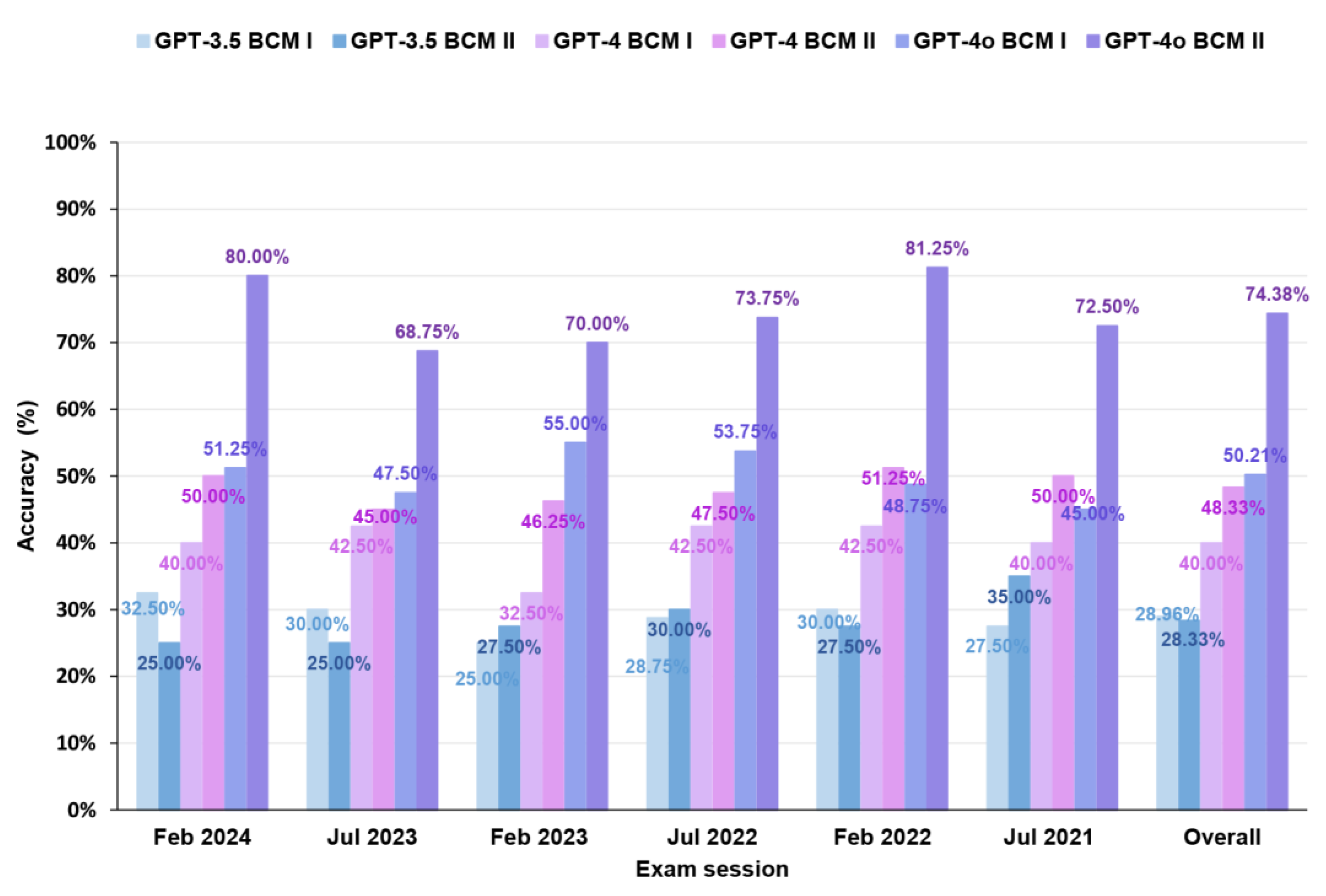

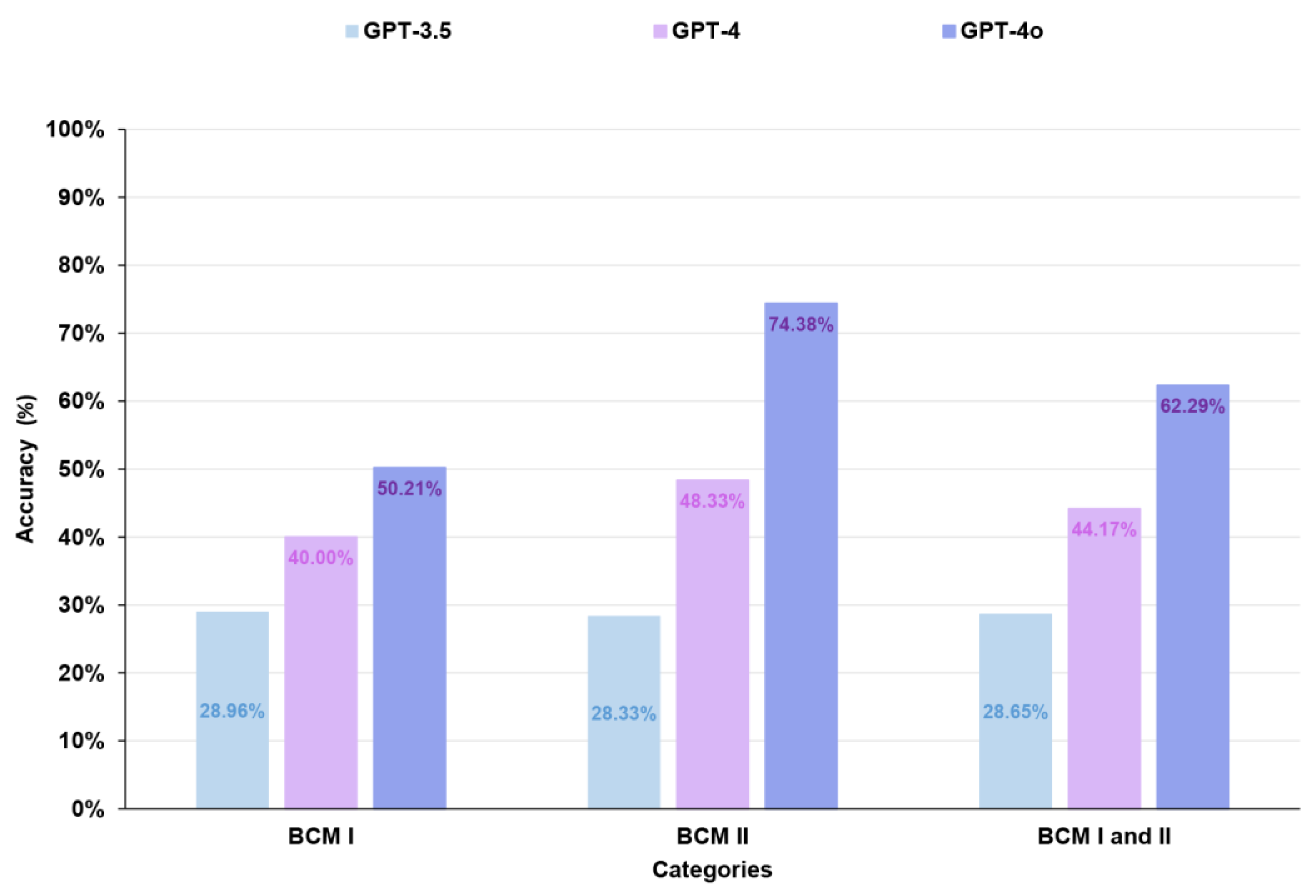

GPT-4o Was the Only Model to Surpass the Passing Threshold

Figure 3 presents the overall accuracies of GPT-3.5, GPT-4, and GPT-4o across three categories: BCM I, BCM II, and BCM I and II combined. In BCM I, the accuracies of GPT-3.5, GPT-4, and GPT-4o were 28.96%, 40.00%, and 50.21%, respectively, but none reached the passing threshold (60%). In BCM II, the accuracies of GPT-3.5, GPT-4, and GPT-4o were 28.33%, 48.33%, and 74.38%, respectively, with only GPT-4o reaching the passing threshold (60%). In the combined BCM I and II, the accuracies of GPT-3.5, GPT-4, and GPT-4o were 28.65%, 44.17%, and 62.29%, respectively, with only GPT-4o exceeding the passing threshold (60%).

Discussion

This is the first study to test the accuracies of GPT-3.5, GPT-4, and GPT-4o in answering questions from the first stage of the Professional and Technical Senior Examination for Doctors of Chinese Medicine in Taiwan. Specifically, we assessed the performance in BCM I and BCM II. We observed that both BCM I and BCM II accuracies increased as the GPT versions advanced. For the overall accuracies in BCM I and II, GPT-3.5 achieved 28.65%, GPT-4 achieved 44.17%, and only GPT-4o exceeded the passing threshold, at 62.29%.

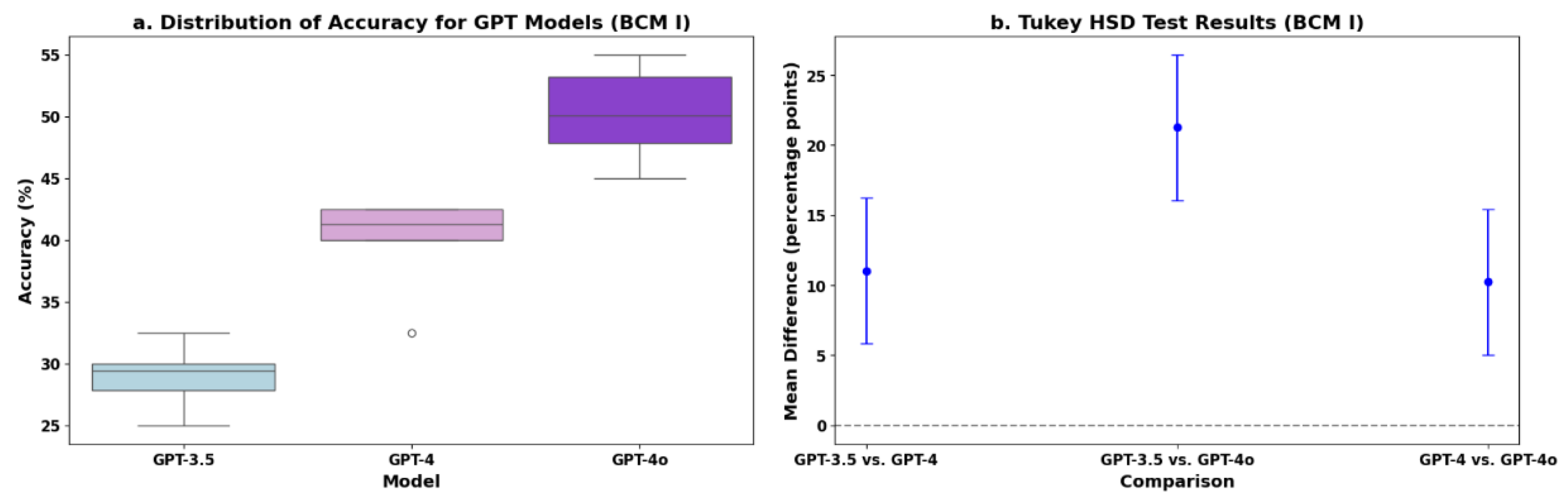

In BCM I, the overall accuracies were 28.96% for GPT-3.5, 40.00% for GPT-4, and 50.21% for GPT-4o, but none reached the passing threshold of 60%. The mean difference between GPT-3.5 and GPT-4 was 11.04 percentage points (p = 0.0033), and that between GPT-4 and GPT-4o was 10.21 percentage points (p = 0.0047), indicating a nearly arithmetic growth trend of about 10 percentage points in accuracy with each version update.

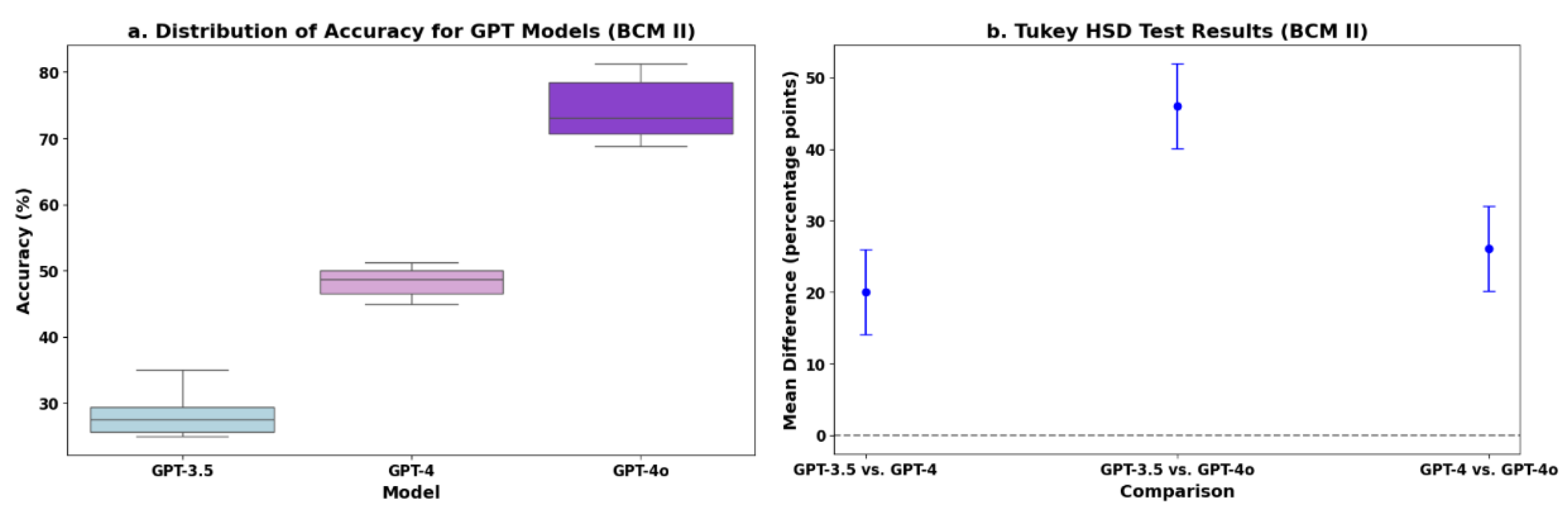

In BCM II, the overall accuracies were 28.33% for GPT-3.5, 48.33% for GPT-4, and 74.38% for GPT-4o, with only GPT-4o reaching the passing threshold (60%). The mean difference between GPT-3.5 and GPT-4 was 20.00 percentage points (p < 0.001), and that between GPT-4 and GPT-4o was 26.05 percentage points (p < 0.001). The data reveal that GPT’s improvement in BCM II exceeds 20 percentage points with each version update. We also noticed that the improvement between the versions in BCM II was greater than that in BCM I.

Comparing the overall performance of each model version in BCM II versus BCM I, we observed that GPT-4o had a higher overall performance in BCM II (74.38%) than in BCM I (50.21%), with a difference of 24.17 percentage points, which was the largest difference among all the model versions, with GPT-3.5 and GPT-4 showing differences of −0.63 and 8.33 points, respectively. Therefore, we conclude that GPT models demonstrate a stronger grasp of knowledge related to Chinese herbal formulas and Chinese materia medica in BCM II compared to their understanding of the history, basic theories, Neijing, and Nanjing in BCM I, which involves more abstract concepts of classical Chinese medicine.

Previous systematic review studies evaluated 45 papers that investigated the performance of ChatGPT in Western medical licensing exams, finding that GPT-4 had an overall accuracy rate of 81% [

8]. Additionally, GPT-4’s average accuracy in Stage 1 of the Senior Professional and Technical Examinations for Medical Doctors in Taiwan was 87.5% [

9], and its accuracy in the Taiwan Advanced Medical Licensing Examination ranged from 63.75% to 93.75% [

10]. These results differ significantly from those in our study, in which GPT-4 achieved an overall average accuracy of 44.17% in BCM I and II.

When Chinese input is used for GPT question answering, the accuracy in TCM is lower compared to that in Western medical knowledge. This is likely because most TCM textbooks are written in classical Chinese, while ChatGPT’s TCM-related knowledge is trained using English datasets, leading to language bias. The differences between the Eastern and Western models are also a factor. One study [

11] observed the performance of eight LLMs with TCM-related questions and found that most China-trained LLMs outperformed Western-trained LLMs. Specifically, all Chinese models passed the exam with accuracies exceeding 60%, while all Western models failed. This performance disparity might stem from the LLMs being primarily trained on English datasets and lacking deep familiarity with Chinese culture, linguistic nuances, and TCM concepts. However, other experimenters have found that ChatGPT demonstrates culturally appropriate humanistic care during simulated consultations and can adjust its responses based on different patient characteristics [

12].

Significant progress has been made in the integration of TCM with AI and its applications in the medical field. Recently, many Chinese medical question-answering models and large language databases have been developed to enhance the TCM language system (TCMLS). Efforts to organize the TCM literature and classify various herbs and prescriptions in detail have been carried out to standardize TCM terminology and improve information retrieval [

13,

14,

15]. Methods include enhancing the model’s ability to engage in complex dialogues and proactive inquiry [

16], as well as optimizing it for specific TCM fields, such as combining LLMs with graph neural network (GNN) technology for TCM prescription recommendation models [

17] and TCM applications in epidemiology [

18]. Additionally, various tools for evaluating the performance of TCM LLMs have emerged, all aimed at advancing AI in Chinese-language question answering for TCM.

However, TCM faces challenges in AI [

19]. First, TCM knowledge is often based on the personal experiences of clinicians, which involve subjective judgments and personalized diagnosis and treatment, thus making the data difficult to quantify and systematize. Second, TCM theories and practices vary across regions and cultural backgrounds. Moreover, the integration of TCM into machine learning may encounter difficulties because TCM diagnosis and treatment experience is based on extensive clinical practice and observation, while machine learning models are trained on large datasets, which may increase the difficulty of collecting training data. Developing interpretable algorithms and models is essential to ensure that both doctors and patients understand and accept the decisions made by the models.

There are some limitations to our study. First, the grading standard for Taiwan’s TCM National Examination relies on selecting the correct or most appropriate answer. When no option is entirely correct, ChatGPT may conclude that no correct answer exists. Furthermore, unlike Western medical licensure examinations, which have been more thoroughly investigated in previous research, there remains a dearth of studies on ChatGPT’s performance in TCM examination questions. Consequently, comparing our findings with other TCM National Examination performance studies for further validation is challenging. Lastly, whether translating the Chinese questions into English might enhance the answer rate remains unknown, necessitating further exploration in future research.

Conclusion

In summary, we found that as GPT models advance, a noticeable increase in accuracy is evident when answering questions related to TCM national exams. However, because of language bias, accuracy still lags behind that of Western medicine. Using ChatGPT in TCM education offers both opportunities and challenges. More training is required using Chinese data, particularly in TCM history, basic theories, Neijing (The Inner Canon of the Yellow Emperors), and Nanjing (The Classic of Difficult Issues), with a focus on improving the interpretation of classical Chinese. Future research should focus on further optimizing the model’s performance in multilingual environments to enhance the application of AI in medical education.

References

- Sahni, N.R.; Carrus, B. Artificial Intelligence in U.S. Health Care Delivery. New England Journal of Medicine 2023, 389, 348–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sallam, M. ChatGPT Utility in Healthcare Education, Research, and Practice: Systematic Review on the Promising Perspectives and Valid Concerns. Healthcare 2023, 11, 887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Dada, A.; Puladi, B.; Kleesiek, J.; Egger, J. ChatGPT in healthcare: A taxonomy and systematic review. Computer Methods and Programs in Biomedicine 2024, 245, 108013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, J.; Tan, M. The role of ChatGPT in scientific communication: writing better scientific review articles. Am J Cancer Res 2023, 13, 1148–1154. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Dave, T.; Athaluri, S.A.; Singh, S. ChatGPT in medicine: an overview of its applications, advantages, limitations, future prospects, and ethical considerations. Front Artif Intell 2023, 6, 1169595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ray, P.P. ChatGPT: A comprehensive review on background, applications, key challenges, bias, ethics, limitations and future scope. Internet of Things and Cyber-Physical Systems 2023, 3, 121–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, W.; Guan, Y.; Chen, J.; Huang, X.; Zhong, Y.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, H. Artificial intelligence in global health equity: an evaluation and discussion on the application of ChatGPT, in the Chinese National Medical Licensing Examination. Front Med (Lausanne) 2023, 10, 1237432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Okuhara, T.; Chang, X.; Shirabe, R.; Nishiie, Y.; Okada, H.; Kiuchi, T. Performance of ChatGPT Across Different Versions in Medical Licensing Examinations Worldwide: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Med Internet Res 2024, 26, e60807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, C.H.; Hsiao, H.J.; Yeh, P.C.; Wu, K.C.; Kao, C.H. Performance of ChatGPT on Stage 1 of the Taiwanese medical licensing exam. Digit Health 2024, 10, 20552076241233144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.Y.; Chan, P.K.; Hsu, W.H.; Kao, C.H. Exploring the proficiency of ChatGPT-4: An evaluation of its performance in the Taiwan advanced medical licensing examination. Digit Health 2024, 10, 20552076241237678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, L.; Mou, W.; Lai, Y.; Lin, J.; Luo, P. Language and cultural bias in AI: comparing the performance of large language models developed in different countries on Traditional Chinese Medicine highlights the need for localized models. Journal of Translational Medicine 2024, 22, 319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KONG, Q.; CHEN, L.; YAO, J.; DING, C.; YIN, P. Feasibility and Challenges of Interactive AI for Traditional Chinese Medicine: An Example of ChatGPT. Chinese Medicine and Culture 2024, 7, 174–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Wang, Y.; Wang, X.; Yang, Y.; Ye, Y. Constructing fine-grained entity recognition corpora based on clinical records of traditional Chinese medicine. BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making 2020, 20, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Li, M.; Pan, F.; Duan, H.; Huang, Z.; Deng, H.; Yu, Z.; Yang, C.; Shen, G.; Qi, P.; Yue, C.; Liu, Y.; Hong, L.; Yu, H.; Fan, G.; Tang, Y. MedChatZH: A tuning LLM for traditional Chinese medicine consultations. Computers in Biology and Medicine 2024, 172, 108290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, G.; Liu, X.; Shi, J.; Wang, Z.; Wang, G. TCM-GPT: Efficient pre-training of large language models for domain adaptation in Traditional Chinese Medicine. Computer Methods and Programs in Biomedicine Update 2024, 6, 100158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Zhao, H.; Zhu, S.; Zhou, G.; Xu, H.; Jia, Y.; Zan, H. Zhongjing: Enhancing the Chinese Medical Capabilities of Large Language Model through Expert Feedback and Real-World Multi-Turn Dialogue. Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence 2024, 38, 19368–19376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, J.; Wang, X.; Yang, T. In Traditional Chinese Medicine Prescription Recommendation Model Based on Large Language Models and Graph Neural Networks, 2023 IEEE International Conference on Bioinformatics and Biomedicine (BIBM), 5-8 Dec. 2023, 2023; 2023; pp 4623-4627.

- Zhou, Z.; Yang, T.; Hu, K. In Traditional Chinese Medicine Epidemic Prevention and Treatment Question-Answering Model Based on LLMs, 2023 IEEE International Conference on Bioinformatics and Biomedicine (BIBM), 5-8 Dec. 2023, 2023; 2023; pp 4755-4760.

- Li, W.; Ge, X.; Liu, S.; Xu, L.; Zhai, X.; Yu, L. Opportunities and challenges of traditional Chinese medicine doctors in the era of artificial intelligence. Front Med (Lausanne) 2023, 10, 1336175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).