Submitted:

22 January 2025

Posted:

23 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Cyclic Elasto-Plasticity for Steels

2.1. Elasto-Plasticity Modelling

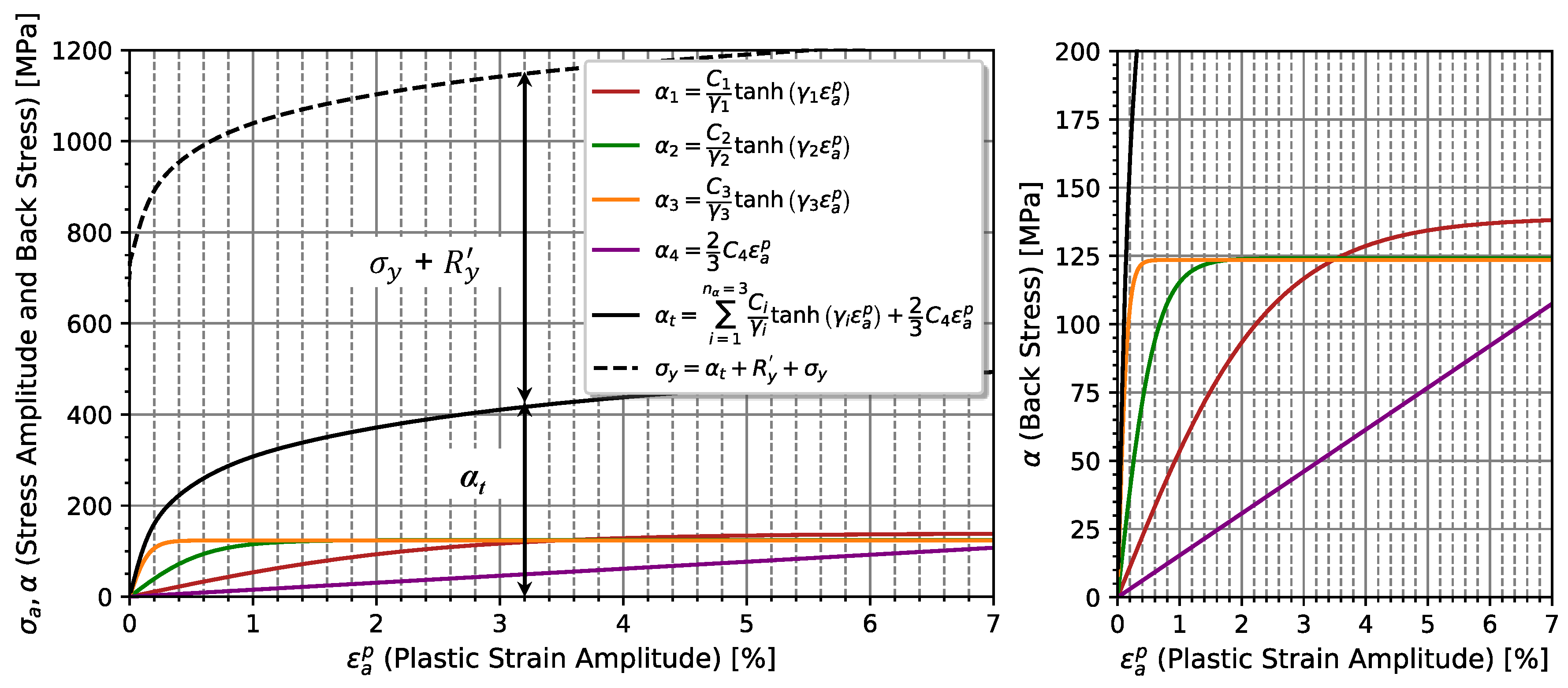

2.2. Kinematic Hardening Model

2.3. Isotropic Hardening Model

2.4. Empirical Estimation of Hardening Variables

3. Material and Analysis Procedure

| Material | C | Si | Mn | Cr | V | S | Pb | Fe |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DIN 51CrV4 (1.815) | 0.47-0.55 | ≤0.40 | 0.70-1.10 | 0.90-1.20 | ≤0.10-0.25 | ≤0.025 | ≤0.025 | 96.45-97.38 |

3.1. Chemical Composition and Microstructure

3.2. Experimental Procedure and Statistical Techniques

3.3. Computational Approach

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Cyclic Behaviour

4.2. Determination of the Kinematic Hardening Properties

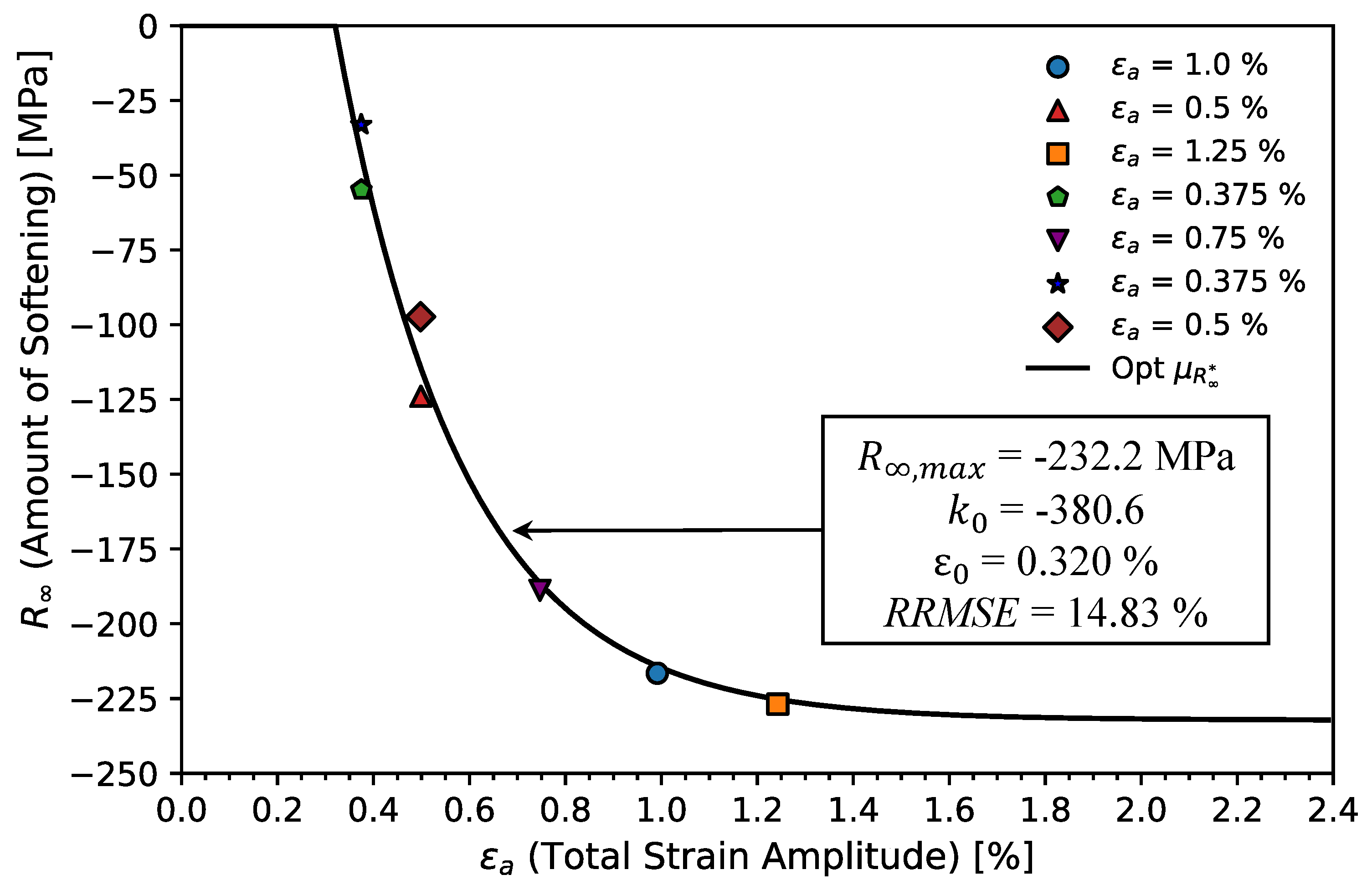

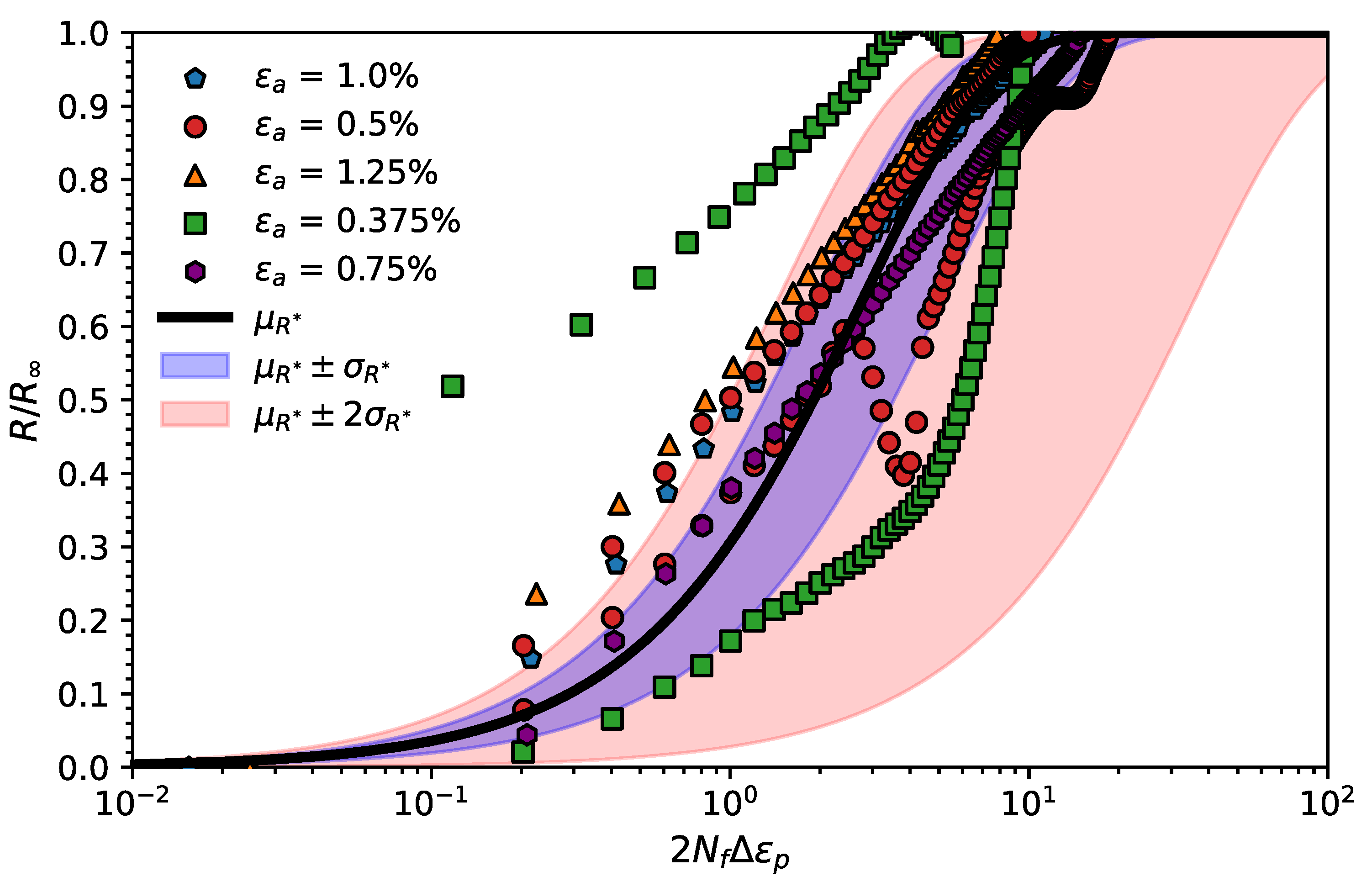

4.3. Determination of the Isotropic Hardening Properties

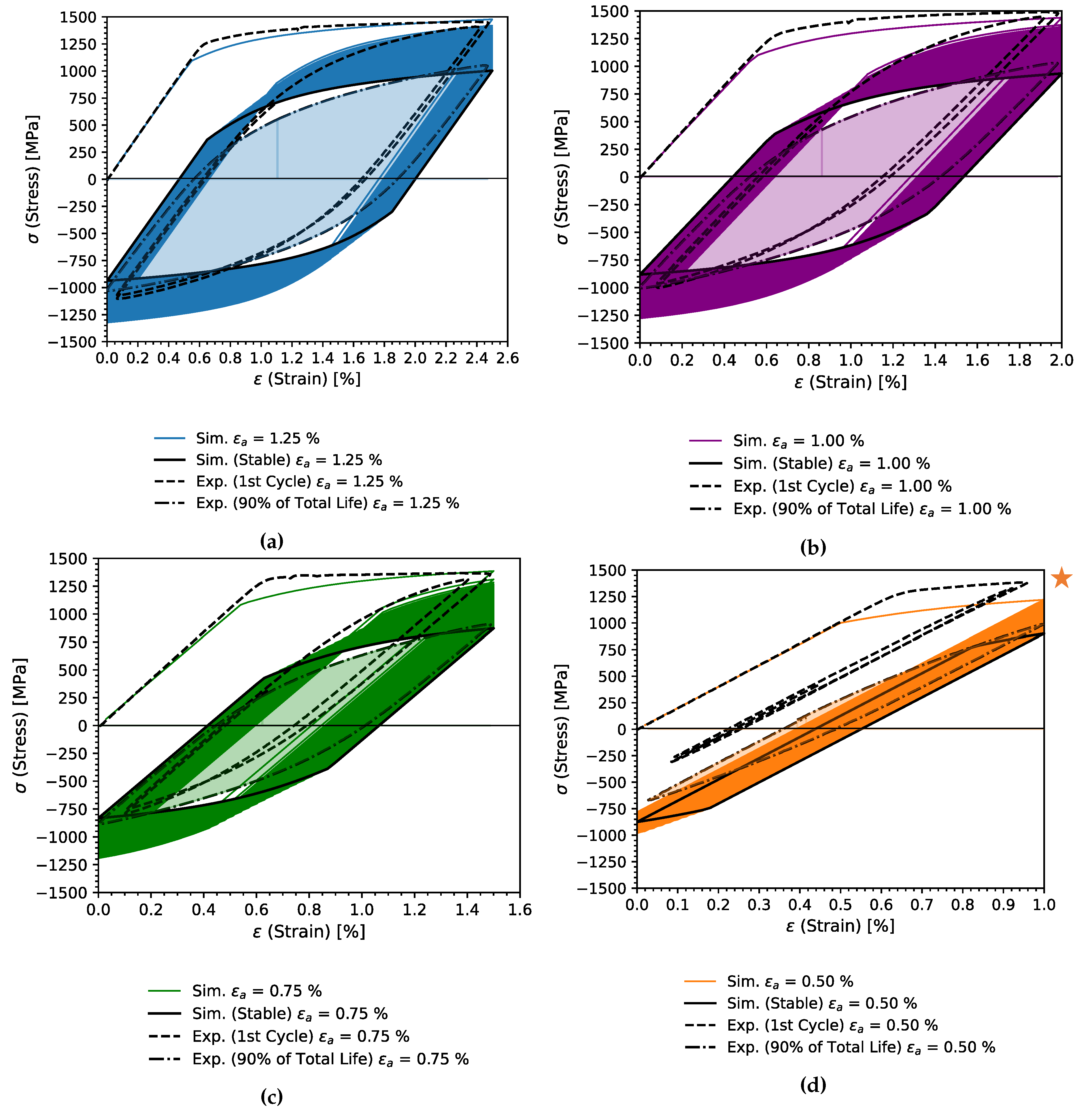

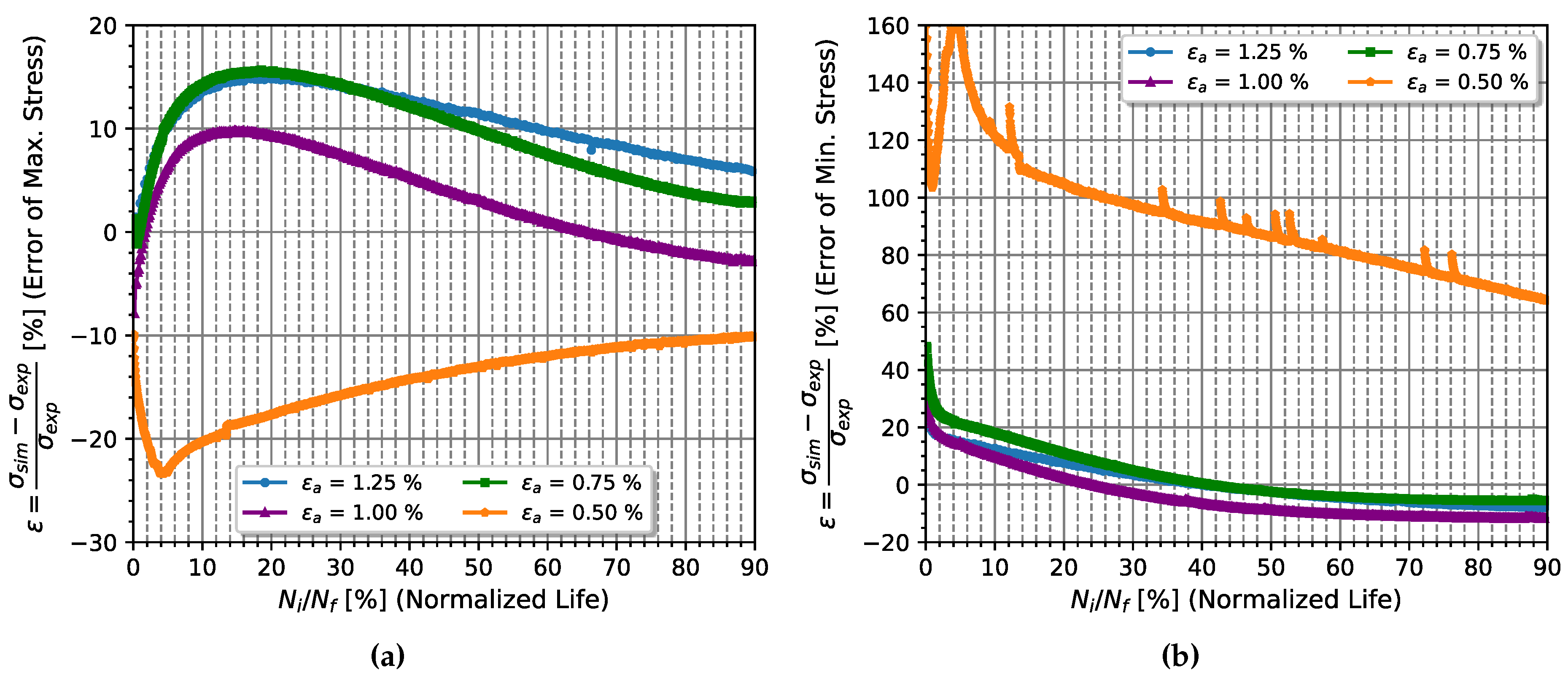

4.4. Cyclic Elasto-Plastic Response Using a Computational Approach

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kam, T.Y.; Arora, V.K.; Bhushan, G.; Aggarwal, M.L. Fatigue Life Assessment of 65Si7 Leaf Springs: A Comparative Study. The Scientific World Journal, Hindawi Publishing Corporation 2014, pp. 365–370. [CrossRef]

- Kong, Y.; Omar, M.; Chua, L.; Abdullah, S. Explicit nonlinear finite element geometric analysis of parabolic leaf springs under various loads. The Scientific World Journal 2013, 2013. [CrossRef]

- Krason, W.; Hryciow, Z.; Wysocki, J. Numerical studies on influence of friction coefficient in multi-leaf spring on suspension basic characteristics. In Proceedings of the AIP Conference Proceedings. AIP Publishing LLC, 2019, Vol. 2078, p. 020049.

- Krason, W.; Wysocki, J.; Hryciow, Z. Dynamics stand tests and numerical research of multi-leaf springs with regard to clearances and friction. Advances in Mechanical Engineering 2019, 11, 1687814019853353. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.Y.; Wei, L.; Wang, J.F.; Wang, J.; Gu, X.S.; Song, C. Study on the modeling method of leaf spring based on assembly pre-stress. Advanced Materials Research 2013, 663, 545–551. [CrossRef]

- Husaini.; Ali, N.; Riantoni, R.; Putra, T.E.; Husin, H. Study of leaf spring fracture behavior used in the suspension systems in the diesel truck vehicles. IOP Conf. Series: Materials Science and Engineering 541 2019. [CrossRef]

- Husaini.; Anshari, R.; Ali, N.; Yunus, J. The analysis of the failure of leaf spring used as the rear suspension system in 110 PS diesel trucks. 2023, p. 012046. [CrossRef]

- Fuentes, J.; Aguilar, H.; Rodríguez, J.; Herrera, E. Premature fracture in automobile leaf springs. Engineering Failure Analysis 2009, 16, 648–655. https://doi.org/Paperspresentedatthe24thmeetingoftheSpanishFractureGroup(Burgos,Spain,March2007.

- Husaini, H.; Farhan, M.; Ali, N.; Putra, T.E.; Anshari, R.; Suherman, K. Analysis of the Leaf Spring Failure in Light Duty Dump Truck. Key Engineering Materials 2022, 930, 43–52. [CrossRef]

- Deulgaonkar, V.R., R.M.K.S.; Mandge, A.; Patil, A.; Makode, A. Failure Analysis of Leaf Spring Used in Transport Utility Vehicles. J Fail. Anal. and Preven 2022, 22, 1844–1852. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.H.; Chen, G.C.; Wu, C.T.; Lee, C.L.; Chen, Y.R.; Huang, J.F.; Hsiao, K.H.; Lin, J.I. Object investigation of industrial heritage: The forging and metallurgy shop in Taipei railway workshop. Applied Sciences 2020, 10, 2408. [CrossRef]

- Matej, J.; Seńko, J.; Awrejcewicz, J. Dynamic Properties of Two-Axle Freight Wagon with UIC Double-Link Suspension as a Non-smooth System with Dry Friction. Applied Non-Linear Dynamical Systems 2014, pp. 255–268. [CrossRef]

- Piotrowski, J. Model of the UIC link suspension for freight wagons. Archive of Applied Mechanics 2003, 73, 517–532. [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, M.; True, H. Dynamics of two-axle railway freight wagons with UIC standard suspension. Vehicle System Dynamics 2006, 44, 139–146. [CrossRef]

- Iwnicki, S.D.; Stichel, S.; Orlova, A.; Hecht, M. Dynamics of railway freight vehicles. Vehicle system dynamics 2015, 53, 995–1033. [CrossRef]

- UIC517. Wagons – Suspension gear – Standardisation. International Union of Railways, UIC 2007.

- of Automotive Engineers. Spring Committee, S. Spring Design Manual. Technical report, 1996.

- Petrović, D.; Bižić.; Gašić, M.; Savković, M. Increasing the Efficiency of Railway Transport by Improvement of Suspension of Freight Wagons. Promet-Traffic and Transportation 2012, 24, 487–493. [CrossRef]

- Yamada, Y. Materials for Springs.; Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg, 2007. [CrossRef]

- Smith, W.F. Principles of Materials Science and Engineering .; 1999.

- Lin, Z.; Gong, D.; Li.; Wang, X.; Ren, X.; Wang, E. Effect of tempering temperature on microstructure and mechanical properties of AISI 6150 steel. Journal of Central South University 2013, 8, 866–870. [CrossRef]

- ISO683-14. Heat-treatable steels, alloy steels and, free-cutting steels Part 14: Hot-rolled steels for quenched and tempered springs. 2004.

- Malikoutsakis, M.; Gakias, C.; Makris, I.; Kinzel, P.; Müller, E.; Pappa, M.; Michailidis, N.; Savaidis, G. On the effects of heat and surface treatment on the fatigue performance of high-strength leaf springs. In Proceedings of the MATEC Web of Conferences. EDP Sciences, 2021, Vol. 349, p. 04007. [CrossRef]

- Gomes, V.M.; Souto, C.D.; Correia, J.A.; de Jesus, A.M. Monotonic and Fatigue Behaviour of the 51CrV4 Steel with Application in Leaf Springs of Railway Rolling Stock. Metals 2024, 14, 266. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Lin, D.G.Y.L.X.W.X.R.; Wang., E. Effect of tempering temperature on microstructure and mechanical properties of AISI 6150 steel. Journal of Central South University 2013, 8, 866–870. [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Zhang, Z.; Hou, J.; Thrush, S.J.; Barber, G.C.; Zou, Q.; Yang, H.; Qiu, F. Tribological behavior of heat treated AISI 6150 steel. Journal of Materials Research and Technology 2020, 9, 12293–12307. [CrossRef]

- Akiniwa, Y.; Stanzl-Tschegg, S.; Mayer, H.; Wakita, M.; Tanaka, K. Fatigue strength of spring steel under axial and torsional loading in the very high cycle regime. International Journal of Fatigue 2008, 30, 2057–2063. [CrossRef]

- Jaramillo, H.E.S.; de Sánchez, N.A.; Avila, J.A.D. Effect of the shot peening process on the fatigue strength of SAE 5160 steel. Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, Part C: Journal of Mechanical Engineering Science 2019, 233, 4328–4335. [CrossRef]

- Gomes, V.M.G.; De Jesus, A.M.P.; Figueiredo, M.; Correia, J.A.F.O.; Calcada, R. Fatigue Failure of 51CrV4 Steel Under Rotating Bending and Tensile 2022. pp. 307–313. [CrossRef]

- Ceyhanli, U.T.; Bozca, M. Experimental and numerical analysis of the static strength and fatigue life reliability of parabolic leaf springs in heavy commercial trucks. Advances in Mechanical Engineering 2020, 12. [CrossRef]

- Infante, V.; Freitas, M.; Baptista, R. Failure analysis of a parabolic spring belonging to a railway wagon. Engineering Failure Analysis 2022, 140, 106526. [CrossRef]

- Gomes, V.; Correia, J.; Calçada, R.; Barbosa, R.; de Jesus, A. Fatigue in Trapezoidal Leaf Springs of Suspensions in Two-Axle Wagons—An Overview and Simulation. In Proceedings of the Virtual Conference on Mechanical Fatigue. Springer, 2020, pp. 97–114. [CrossRef]

- Clarke, C.; Borowski, G. Evaluation of a leaf spring failure. Journal of failure Analysis and Prevention 2005, 5, 54–63. [CrossRef]

- Soady, K.A. Life assessment methodologies incoroporating shot peening process effects: mechanistic consideration of residual stresses and strain hardening: Part 1 – effect of shot peening on fatigue resistance. Materials Science and Technology 2013, 29, 637–651. [CrossRef]

- Llaneza, V.; Belzunce, F. Study of the effects produced by shot peening on the surface of quenched and tempered steels: roughness, residual stresses and work hardening. Applied Surface Science 2015, 356, 475–485. [CrossRef]

- Prager, W. Recent developments in the mathematical theory of plasticity. International Journal of Plasticity 1949, 20, 235–241. [CrossRef]

- Mroz, Z. On the description of anisotropic workhardening. Journal of the Mechanics and Physics of Solids 1967, 15, 163–175. [CrossRef]

- Dafalias, Y.; Popov, E. A model of nonlinearly hardening materials for complex loading. Acta mechanica 1975, 21, 173–192. https://doi.org/http://sokocalo.engr.ucdavis.edu/~jeremic/PAPERSlocalREPO/CM2133.pdf.

- Krieg, R. A practical two surface plasticity theory. J. Appl. Mech 1975, 42, 641–646. [CrossRef]

- Malinin, N.; Khadjinsky, G. Theory of creep with anisotropic hardening. International Journal of Mechanical Sciences 1972, 14, 235–246. [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, P.J.; Frederick, C.O. A mathematical representation of the multiaxial Bauschinger effect. Report, CEGB, Central Electricity Generating Board, Berkeley, UK, 1966. [CrossRef]

- Chaboche, J.L. A review of some plasticity and viscoplasticity constitutive theories. International Journal of Plasticity 2008, 24, 1642–1693. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y. Cyclic plasticity with an emphasis on ratchetting. PhD thesis, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 1993. https://doi.org/https://www.proquest.com/openview/a233be354ea54bea768e6987de8e4f77/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=18750&diss=y.

- Hu, W.; Wang, C.H.; Barter, S. Analysis of Cyclic Mean Stress Relaxation and Strain Ratchetting Behaviour of Aluminium 7050. Technical report, Aeronautical and Maritime Research Lab Melbourne (Australia), 1999.

- Kubaschinski, P.; Gottwalt, A.; Tetzlaff, U.; Altenbach, H.; Waltz, M. Calibration of a combined isotropic-kinematic hardening material model for the simulation of thin electrical steel sheets subjected to cyclic loading. Materialwissenschaft und Werkstofftechnik 2022, 53, 422–439. [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.H.; Van Do, V.N.; Chang, K.H. Analysis of uniaxial ratcheting behavior and cyclic mean stress relaxation of a duplex stainless steel. International Journal of Plasticity 2014, 62, 17–33. [CrossRef]

- Hassan, T.; Kyriakides, S. Ratcheting in cyclic plasticity, Part I: uniaxial behavior. International Journal of Plasticity 1992, 8, 91–116. [CrossRef]

- Agius, D.; Wallbrink, C.; Kourousis, K.I. Cyclic elastoplastic performance of aluminum 7075-T6 under strain-and stress-controlled loading. Journal of Materials Engineering and Performance 2017, 26, 5769–5780. [CrossRef]

- Badnava, H.; Pezeshki, S.; Fallah Nejad, K.; Farhoudi, H. Determination of combined hardening material parameters under strain controlled cyclic loading by using the genetic algorithm method. Journal of mechanical science and technology 2012, 26, 3067–3072. [CrossRef]

- Mróz, Z.; Maciejewski, J. Constitutive modeling of cyclic deformation of metals under strain controlled axial extension and cyclic torsion. Acta Mechanica 2018, 229, 475–496. [CrossRef]

- De Rosa, S.; Franco, F.; Capasso, D.; Costagliola, S.; Ferrante, E. Elasto-visco-plasticity for the metallic materials: a review of the models. Aerotecnica Missili & Spazio 2013, 92, 27–40. [CrossRef]

- Agius, D.; Kajtaz, M.; Kourousis, K.I.; Wallbrink, C.; Wang, C.H.; Hu, W.; Silva, J. Sensitivity and optimisation of the Chaboche plasticity model parameters in strain-life fatigue predictions. Materials & Design 2017, 118, 107–121. [CrossRef]

- Rokhgireh, H.; Nayebi, A. Cyclic uniaxial and multiaxial loading with yield surface distortion consideration on prediction of ratcheting. Mechanics of Materials 2012, 47, 61–74. [CrossRef]

- Mal, S.; Bhattacharjee, S.; Jana, M.; Das, P.; Acharyya, S.K. Optimization of Chaboche kinematic hardening parameters for 20MnMoNi55 reactor pressure vessel steel by sequenced genetic algorithms maintaining the hierarchy of dependence. Engineering Optimization 2021, 53, 335–347. [CrossRef]

- Rezaiee-Pajand, M.; Sinaie, S. On the calibration of the Chaboche hardening model and a modified hardening rule for uniaxial ratcheting prediction. International Journal of Solids and Structures 2009, 46, 3009–3017. [CrossRef]

- Sajjad, H.M.; Hanke, S.; Güler, S.; ul Hassan, H.; Fischer, A.; Hartmaier, A. Modelling Cyclic Behaviour of Martensitic Steel with J2 Plasticity and Crystal Plasticity. Materials 2019, 12. [CrossRef]

- Kalnins, A.; Rudolph, J.; Willuweit, A. Using the nonlinear kinematic hardening material model of Chaboche for elastic–plastic ratcheting analysis. Journal of Pressure Vessel Technology 2015, 137. [CrossRef]

- Qvale, P.; Zarandi, E.P.; Arredondo, A.; Ås, S.K.; Skallerud, B.H. Effect of cyclic softening and mean stress relaxation on fatigue crack initiation in a hemispherical notch. Fatigue & Fracture of Engineering Materials & Structures 2022, 45, 3592–3608. [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Liang, G.; Yang, Y. A strategy to fast determine Chaboche elasto-plastic model parameters by considering ratcheting. International Journal of Pressure Vessels and Piping 2019, 172, 251–260. [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.C.; Goyal, S.; Sandhya, R.; Ray, S. Low cycle fatigue life prediction of 316 L(N) stainless steel based on cyclic elasto-plastic response. Nuclear Engineering and Design 2012, 253, 219–225. [CrossRef]

- Shao, X.; Du, J.; Fu, X.; Xiong, F.; Li, H.; Tian, J.; Lu, X.; Xie, H. Simplified Elastoplastic Fatigue Correction Factor Analysis Approach Based on Minimum Conservative Margin. Metals 2022, 12. [CrossRef]

- Veerababu, J.; Goyal, S.; Sandhya, R.; Laha, K. Low cycle fatigue properties and cyclic elasto-plastic response of modified 9Cr-1Mo steel. Transactions of the Indian Institute of Metals 2016, 69, 501–505. [CrossRef]

- Song, W.; Liu, X.; Xu, J.; Fan, Y.; Shi, D.; Khosravani, M.R.; Berto, F. Multiaxial low cycle fatigue of notched 10CrNi3MoV steel and its undermatched welds. International Journal of Fatigue 2021, 150, 106309. [CrossRef]

- Natkowski, E.; Sonnweber-Ribic, P.; Münstermann, S. Surface roughness influence in micromechanical fatigue lifetime prediction with crystal plasticity models for steel. International Journal of Fatigue 2022, 159, 106792. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Liu, H.; Bai, H.; Zhu, C.; Wu, W. Ratchetting-multiaxial fatigue damage analysis in gear rolling contact considering tooth surface roughness. Wear 2019, 428, 137–146. [CrossRef]

- Hasunuma, S.; Ogawa, T. Crystal plasticity FEM analysis for variation of surface morphology under low cycle fatigue condition of austenitic stainless steel. International Journal of Fatigue 2019, 127, 488–499. [CrossRef]

- Radaj, D.; Vormwald, M.; Vormwald, M. Elastic-plastic fatigue crack growth. Advanced methods of fatigue assessment 2013, pp. 391–481. [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, R.; Seifi, R. Fatigue crack growth determination based on cyclic plastic zone and cyclic J-integral in kinematic–isotropic hardening materials with considering Chaboche model. Fatigue & Fracture of Engineering Materials & Structures 2020, 43, 2668–2682. [CrossRef]

- Antunes, F.; Branco, R.; Prates, P.; Borrego, L. Fatigue crack growth modelling based on CTOD for the 7050-T6 alloy. Fatigue & Fracture of Engineering Materials & Structures 2017, 40, 1309–1320. [CrossRef]

- Dong, Q.; Yang, P.; Xu, G.; Deng, J. Mechanisms and modeling of low cycle fatigue crack propagation in a pressure vessel steel Q345. International Journal of Fatigue 2016, 89, 2–10. [CrossRef]

- Broggiato, G.B.; Campana, F.; Cortese, L. The Chaboche nonlinear kinematic hardening model: calibration methodology and validation. Meccanica 2008, 43, 115–124. [CrossRef]

- Koo, S.; Han, J.; Marimuthu, K.P.; Lee, H. Determination of Chaboche combined hardening parameters with dual backstress for ratcheting evaluation of AISI 52100 bearing steel. International Journal of Fatigue 2019, 122, 152–163. [CrossRef]

- Mohammadpour, A.; Chakherlou, T. Numerical and experimental study of an interference fitted joint using a large deformation Chaboche type combined isotropic–kinematic hardening law and mortar contact method. International Journal of Mechanical Sciences 2016, 106, 297–318. [CrossRef]

- Gomes, V.M.; Eck, S.; De Jesus, A.M. Cyclic hardening and fatigue damage features of 51CrV4 steel for the crossing nose design. Applied Sciences 2023, 13, 8308. [CrossRef]

- Niu, X.P.; Wang, R.Z.; Liao, D.; Zhu, S.P.; Zhang, X.C.; Keshtegar, B. Probabilistic modeling of uncertainties in fatigue reliability analysis of turbine bladed disks. International Journal of Fatigue 2021, 142, 105912. [CrossRef]

- Hu, F.; Shi, G. Constitutive model for full-range cyclic behavior of high strength steels without yield plateau. Construction and Building Materials 2018, 162, 596–607. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.B.; Li, G.Q.; Cui, W.; Chen, S.W.; Sun, F.F. Experimental investigation and modeling of cyclic behavior of high strength steel. Journal of Constructional Steel Research 2015, 104, 37–48. [CrossRef]

- Jia, C.; Shao, Y.; Guo, L.; Liu, H. Cyclic behavior and constitutive model of high strength low alloy steel plate. Engineering Structures 2020, 217, 110798. [CrossRef]

- Bouchenot, T.; Felemban, B.; Mejia, C.; Gordon, A.P. Application of Ramberg-Osgood plasticity to determine cyclic hardening parameters. In Proceedings of the ASME Power Conference. American Society of Mechanical Engineers, 2016, Vol. 50213, p. V001T02A003. [CrossRef]

- Xue, L.; Shang, D.G.; Li, D.H.; Xia, Y. Unified Elastic–Plastic Analytical Method for Estimating Notch Local Strains in Real Time under Multiaxial Irregular Loading. Journal of Materials Engineering and Performance 2021, 30, 9302–9314. [CrossRef]

- Ramberg, W.; Osgood, W.R. Description of Stress-Strain Curves by Three Parameters. Technical Report 902, 1943. https://doi.org/https://ntrs.nasa.gov/archive/nasa/casi.ntrs.nasa.gov/19930081614.pdf.

- Nejad, R.M.; Berto, F. Fatigue fracture and fatigue life assessment of railway wheel using non-linear model for fatigue crack growth. International Journal of Fatigue 2021, 153, 106516. [CrossRef]

- Correia, J.A.; da Silva, A.L.; Xin, H.; Lesiuk, G.; Zhu, S.P.; de Jesus, A.M.; Fernandes, A.A. Fatigue performance prediction of S235 base steel plates in the riveted connections. In Proceedings of the Structures. Elsevier, 2021, Vol. 30, pp. 745–755. [CrossRef]

- Qiang, B.; Liu, X.; Liu, Y.; Yao, C.; Li, Y. Experimental study and parameter determination of cyclic constitutive model for bridge steels. Journal of Constructional Steel Research 2021, 183, 106738. [CrossRef]

- Nejad, R.M.; Berto, F. Fatigue crack growth of a railway wheel steel and fatigue life prediction under spectrum loading conditions. International Journal of Fatigue 2022, 157, 106722. [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Shi, J.; Cao, X.; Zhi, J. Low cycle fatigue life assessment based on the accumulated plastic strain energy density. Materials 2021, 14, 2372. [CrossRef]

- Souto, C.D.; Gomes, V.M.; Da Silva, L.F.; Figueiredo, M.V.; Correia, J.A.; Lesiuk, G.; Fernandes, A.A.; De Jesus, A.M. Global-local fatigue approaches for snug-tight and preloaded hot-dip galvanized steel bolted joints. International Journal of Fatigue 2021, 153, 106486. [CrossRef]

- Kreithner, M.; Niederwanger, A.; Lang, R. Influence of the Ductility Exponent on the Fatigue of Structural Steels. Metals 2023, 13, 759. [CrossRef]

- Möller, B.; Tomasella, A.; Wagener, R.; Melz, T. Cyclic Material Behavior of High-Strength Steels Used in the Fatigue Assessment of Welded Crane Structures with a Special Focus on Transient Material Effects. SAE International Journal of Engines 2017, 10, 331–339. https://doi.org/https://www.jstor.org/stable/26285046.

- Basan, R.; Franulović, M.; Prebil, I.; Kunc, R. Study on Ramberg-Osgood and Chaboche models for 42CrMo4 steel and some approximations. Journal of Constructional Steel Research 2017, 136, 65–74. [CrossRef]

- Chaboche, J.L. A review of some plasticity and viscoplasticity constitutive theories. International journal of plasticity 2008, 24, 1642–1693. [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.; Lee, K.; Li, D.; Yoo, S.; Nam, W. Microstructural influence on fatigue properties of a high-strength spring steel. Materials Science and Engineering: A 1998, 241, 30–37. [CrossRef]

- ISO6892-1. Metallic materials-tensile testing-Part 1: Method of test at ambient temperature 2009.

- ASTME606. Standard Test Method for Strain-Controlled Fatigue Testing. Annual Book of ASTM Standards 1998, pp. 1–15.

- Montgomery, D.C.; Runger, G.C. Applied Statistics and Probability for Engineers, 6ª ed.; John Wiley and Sons, Inc: Arizona State University, 2001.

- Martins, J.R.; Ning, A. Engineering design optimization; Cambridge University Press, 2021.

- Hager, W.W.; Zhang, H. Algorithm 851: CG_DESCENT, a conjugate gradient method with guaranteed descent. ACM Transactions on Mathematical Software (TOMS) 2006, 32, 113–137. [CrossRef]

- Revels, J.; Lubin, M.; Papamarkou, T. Forward-mode automatic differentiation in Julia. arXiv preprint arXiv:1607.07892 2016. [CrossRef]

- Bednarcyk, B.A.; Aboudi, J.; Arnold, S.M. The equivalence of the radial return and Mendelson methods for integrating the classical plasticity equations. Computational Mechanics 2008, 41, 733–737. [CrossRef]

- Krieg, R.D.; Krieg, D. Accuracies of numerical solution methods for the elastic-perfectly plastic model. J. Pressure Vessel Technol. 1977, 99, 510–515. [CrossRef]

- Matsumoto, M.; Nishimura, T. Mersenne twister: a 623-dimensionally equidistributed uniform pseudorandom number generator. ACM Transactions on Modeling and Computer Simulation 1998, 8, 3–30. [CrossRef]

- Matsumoto, M.; Kurita, Y. Twisted GFSR generators. ACM Transactions on Modeling and Computer Simulation 1992, 2, 179–194. [CrossRef]

- Muralidharan, U.; Manson, S.S. A Modified Universal Slopes Equation for Estimation of Fatigue Characteristics of Metals. Journal of Engineering Materials and Technology 1988, 110, 55–58. [CrossRef]

- Srnec Novak, J.; De Bona, F.; Benasciutti, D. An isotropic model for cyclic plasticity calibrated on the whole shape of hardening/softening evolution curve. Metals 2019, 9, 950. [CrossRef]

- Pelegatti, M.; Lanzutti, A.; Salvati, E.; Srnec Novak, J.; De Bona, F.; Benasciutti, D. Cyclic plasticity and low cycle fatigue of an AISI 316L stainless steel: Experimental evaluation of material parameters for durability design. Materials 2021, 14, 3588. [CrossRef]

| E | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [GPa] | [MPa] | [MPa] | [%] | [%] | |

| Average | 7.53 | 34.69 | |||

| Std. Dev. [24] | |||||

| DIN 51CrV4 (1.8159) | 200 | 1200 | 1350-1650 | 6 | 30 |

| L | W | R | d/dt | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [mm] | [mm] | [mm] | [mm] | [mm] | [mm] | [%/s] | ||

| 15 | 135 | 20 | 12 | 0.0 | 0.8 | |||

| RRMSE * | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [MPa] | [ MPa] | [ MPa] | [MPa] | [MPa] | [MPa] | [MPa] | % | |||||

| 50% | 731.5 | -357.7 | 1514.3 | 0.0790 | 80097.1 | 648.4 | 20486.2 | 164.9 | 5650.1 | 40.64 | 2302.7 | 0.2594 |

| 90% | 676.7 | -412.5 | 1576.5 | 0.0918 | 81701.2 | 610.2 | 22035.4 | 159.1 | 6332.2 | 39.93 | 2673.4 | 0.2853 |

| Diff. | 7.49 | 15.32 | 4.09 | 16.20 | 2.00 | 5.89 | 7.56 | 3.49 | 12.07 | 1.75 | 13.87 | 9.98 |

| E | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [GPa] | [MPa] | [MPa] | [MPa] | [MPa] | [MPa] | [MPa] | [MPa] | |||||

| 202.5 | 0.29 | 1089.2 | -232.2 | 0.3705 | 676.7 | 80097.1 | 648.4 | 20486.2 | 164.9 | 5650.1 | 40.64 | 2302.7 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).