1. Introduction

Rett syndrome is a rare and severe neurodevelopmental disorder primarily caused by mutations in the

MECP2 gene, located on the X chromosome [

1]. This condition predominantly affects females due to its X-linked inheritance pattern and is characterized by a distinct clinical trajectory. After an initial period of normal development, typically lasting 6 to 18 months, affected individuals experience progressive developmental regression, marked by the loss of acquired motor and cognitive skills, the emergence of stereotypic hand movements, and seizures. Microcephaly, resulting from decelerated head growth during infancy, is considered a hallmark feature of Rett syndrome and is included in its diagnostic criteria [

1,

2].

Despite its well-defined clinical features, Rett syndrome exhibits considerable phenotypic variability. Some patients display atypical presentations, such as preserved speech, late-onset regression, or mild cognitive impairments, while others demonstrate rare manifestations like macrocephaly and hyperostosis frontalis interna (HFI) [

3,

4]. HFI, defined as abnormal thickening of the frontal bone, is particularly uncommon in pediatric populations and is more typically associated with metabolic disturbances, hormonal imbalances, or the prolonged use of antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) [

5]. These atypical presentations, though rare, can complicate the diagnostic process and blur the distinction between Rett syndrome and other neurodevelopmental disorders with overlapping clinical features.

Differential diagnoses to consider when atypical features such as macrocephaly or HFI are present include MECP2 duplication syndrome, PTEN hamartoma tumor syndrome (PHTS), and Sotos syndrome, all of which share overlapping symptoms, such as developmental delay and cranial anomalies, but have distinct genetic and clinical profiles. This underscores the critical need for detailed phenotypic evaluation and genetic testing to confirm the diagnosis in atypical cases. Additionally, understanding the broader systemic effects of MECP2 dysfunction, including its impact on skeletal and metabolic systems, remains an area of active investigation.

In this report, we present a rare case of Rett syndrome featuring macrocephaly and HFI, highlighting the expanding phenotypic spectrum of this condition. This case demonstrates the importance of a comprehensive diagnostic approach and the need for multidisciplinary management strategies to address the complex interplay of genetic, hormonal, and environmental factors in Rett syndrome. Further research into these rare manifestations may provide new insights into the molecular and systemic effects of MECP2 mutations and pave the way for personalized therapeutic approaches.

2. Case Presentation

A 16-year-old girl with a history of autism and early-onset seizures was referred for neurological evaluation. Her early development was reportedly normal until 18 months of age, when she experienced developmental regression. This regression included the loss of acquired speech, impaired social interactions, and the emergence of stereotypic hand movements. Brain MRI was performed at the age of 2 years with no abnormal findings. Based on these clinical features, Rett syndrome and various other differential diagnoses were suspected, and further genetic analysis was performed.

Comprehensive genetic testing was performed on the patient’s blood DNA, targeting the MECP2 gene. The coding regions of exons 1 to 4 were amplified using PCR, followed by sequence analysis. Exons 1b and 2 were examined using Sanger sequencing, while exons 3 and 4 were analyzed with denaturing high-performance liquid chromatography (DHPLC). A cytosine-to-thymine substitution at nucleotide position 882 (c.882C>T) in exon 4 was identified on one of the X chromosomes. This mutation resulted in a premature stop codon at codon 270 (Arg270Stop), where arginine (CGA) was replaced by a termination codon (TGA). Consequently, translation was prematurely terminated, producing an abnormally truncated MECP2 protein. This genetic finding provided definitive confirmation of Rett syndrome and explained the disruption of normal protein function underlying the patient’s clinical phenotype.

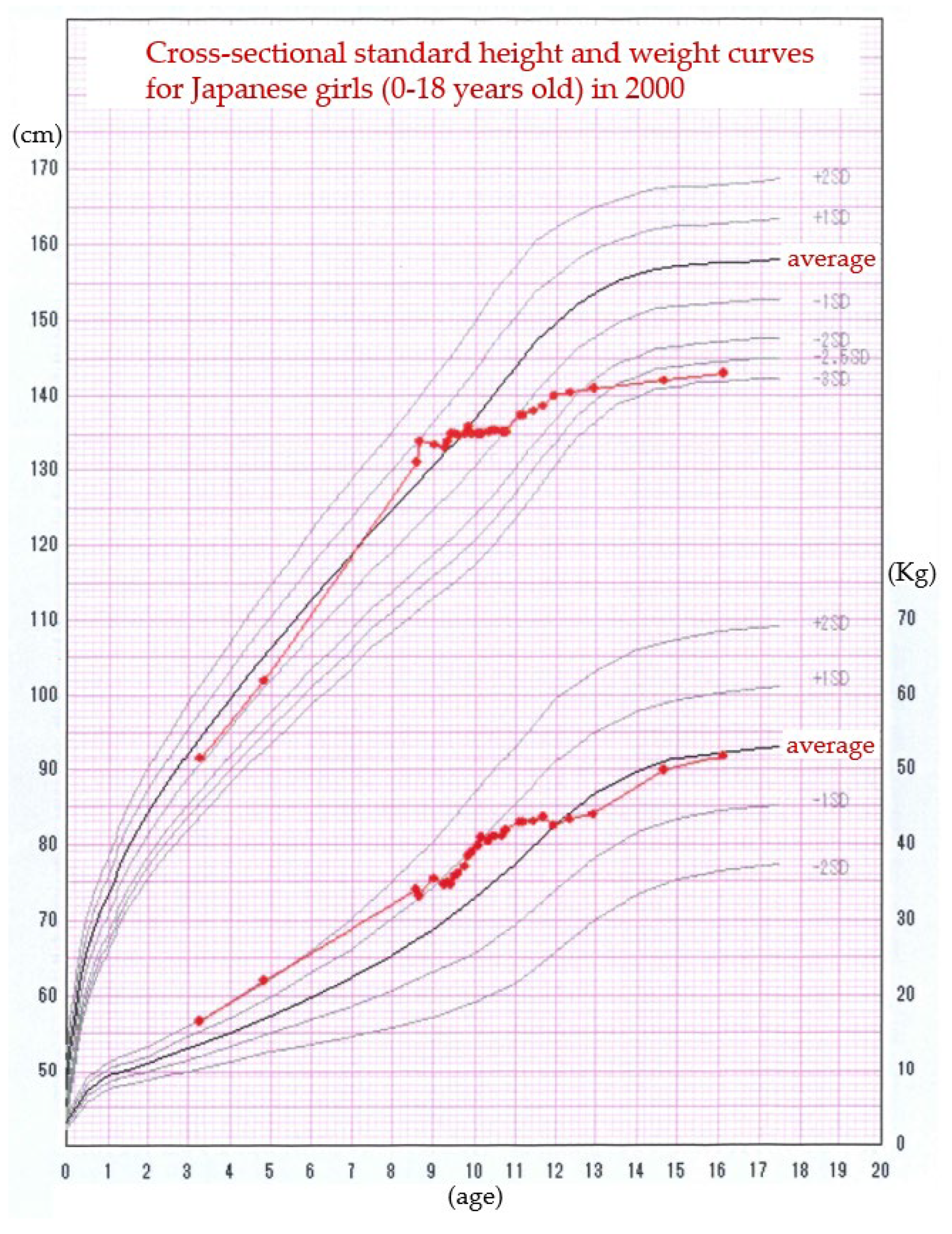

The patient’s medical history was notable for other complications: at age 8, she was approximately average height, but had premature breasts and menarche. She was subsequently diagnosed with central precocious puberty at age 9 and was managed for 3 years with monthly injections of leuprorelin acetate. During the period of leuprorelin acetate injections, menstruation was absent and growth in height had ceased. After the leuprorelin acetate was completed, the patient grew slightly in height and menstruation was observed on monthly basis (

Figure 1).

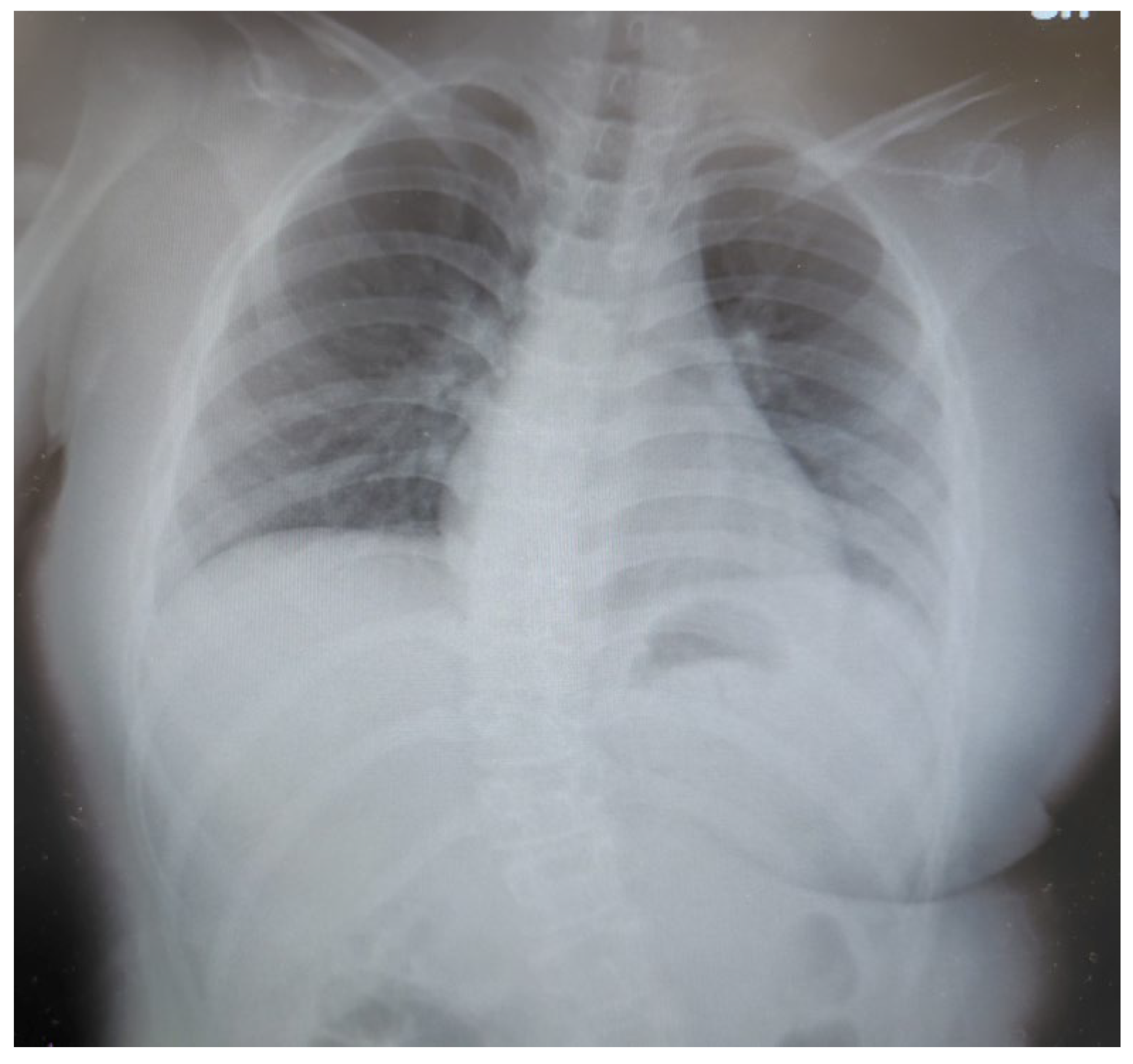

After the age of 10 years, when she grew taller, she frequently bent her trunk to the left. At first, we thought it was involuntary movements or epileptic seizures and observed her, but gradually she began to have difficulty walking alone. When physiotherapy was started for rehabilitation, scoliosis was suspected and radiographs were performed. Radiographs performed at the age of 11 years showed scoliosis of the spine (

Figure 2).

The patient presented with a history of epileptic seizures that had first manifested at the age of three. These seizures were managed over the years through a long-term anti-seizure medicine (ASM) regimen. By the age of 16, her treatment included a combination of valproate (600 mg, once daily), zonisamide (300 mg, divided into two doses), clobazam (20 mg, divided into two doses), lamotrigine (100 mg, divided into two doses), and perampanel (10 mg, once daily). Despite the extensive and carefully monitored pharmacological management, the patient continued to experience persistent motor abnormalities, which significantly impaired her daily activities and overall quality of life. Some of these motor symptoms were initially misinterpreted as being directly related to her underlying epileptic condition, further complicating the diagnostic process and therapeutic approach.

During a detailed neurological assessment, dystonia and transient episodes of hypoventilation and hypoventilation and/or hyperventilation were identified. These findings prompted a thorough reassessment of her AED regimen, leading to reductions in the dosages of her prescribed medications. This adjustment resulted in notable improvements in her dystonic motor symptoms, strongly suggesting that overmedication had played a role in exacerbating these abnormalities. However, this reduction in AED dosages was followed by the recurrence of generalized tonic-clonic seizures, occurring several times per week, with each episode lasting less than five minutes. After a comprehensive discussion with the patient and her family, informed consent was obtained to reinstate the original AED dosages an effort to better control her seizure activity. Electroencephalography (EEG) performed during this period did not detect epileptic discharges, further supporting the hypothesis that her motor abnormalities were not primarily seizure-related but instead linked to other factors.

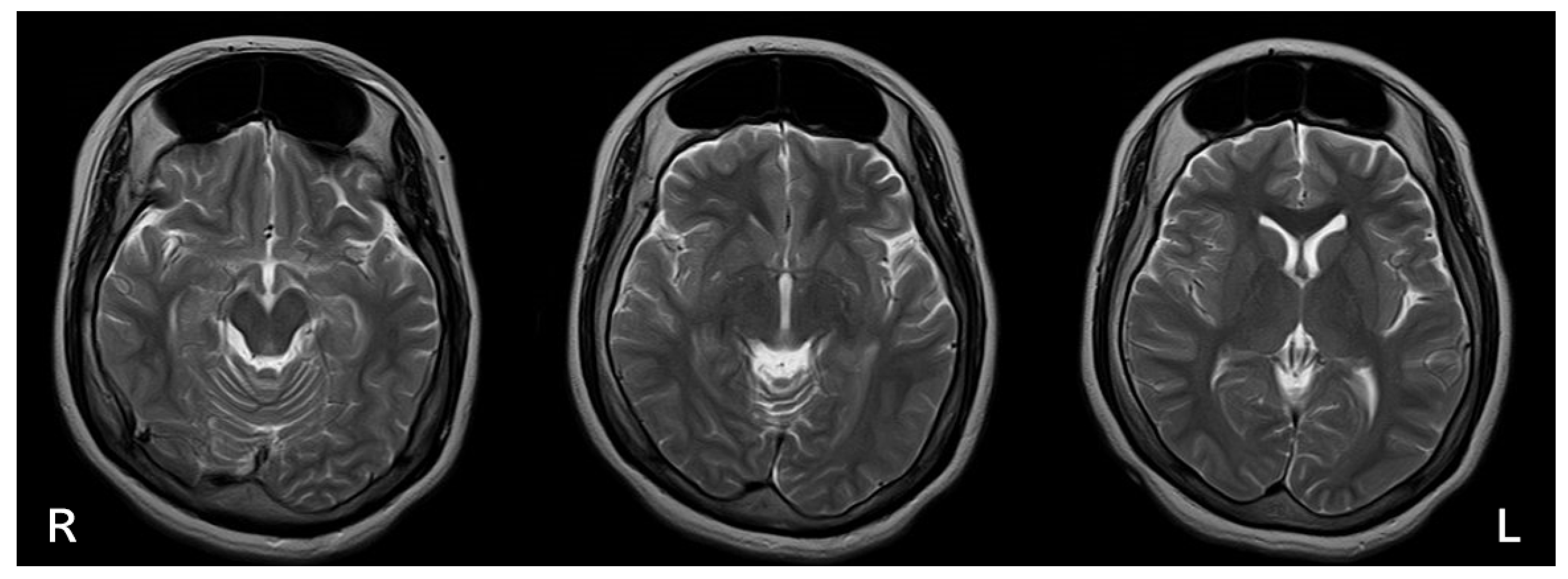

On physical examination at 16 years of age, her height was 143 cm (-2.6 SDs), her weight was 51.8 kg (+0.1 SDs), and her head circumference measured 57.5 cm (+2.5 SDs), indicative of macrocephaly. This finding was atypical for Rett syndrome, adding another layer of diagnostic complexity. Brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed marked thickening of the frontal bone along with bilateral enlargement of the frontal sinuses, findings consistent with hyperostosis frontalis interna (HFI) (

Figure 3).

Further systemic evaluation uncovered additional abnormalities, including mild osteopenia and altered hormonal profiles suggestive of underlying metabolic influences. These findings highlighted the multifactorial and systemic nature of her condition, emphasizing the need for a multidisciplinary approach to her management. This case illustrates the importance of recognizing and addressing atypical clinical features, such as macrocephaly and HFI, which can obscure the diagnosis and complicate the overall treatment strategy. The case also underscores the value of a thorough, individualized, and holistic evaluation in patients with complex presentations, especially when standard diagnostic criteria may not fully explain their clinical features.

3. Discussion

This case illustrates an atypical presentation of Rett syndrome, characterized by macrocephaly and hyperostosis frontalis interna (HFI), both of which deviate significantly from the classical phenotype of the condition. Microcephaly is a hallmark feature of Rett syndrome, typically resulting from impaired neuronal growth and reduced brain size due to

MECP2 dysfunction [

1]. The occurrence of macrocephaly, as observed in this patient, challenges the conventional understanding of cranial development in Rett syndrome and suggests that certain

MECP2 mutations may exert unanticipated effects on cranial growth and development. This variability underscores the importance of expanding our understanding of the phenotypic spectrum of Rett syndrome, particularly regarding its extracranial manifestations, and the broader implications of

MECP2 dysfunction on systemic development.

The presence of HFI in this patient adds a unique and complex dimension to the clinical presentation. HFI, defined as abnormal thickening of the frontal bone, is an uncommon finding in young individuals and is rarely described in pediatric populations. It is more frequently observed in postmenopausal women or associated with conditions such as metabolic or hormonal abnormalities and prolonged use of antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) [

4]. In the context of Rett syndrome, the presence of HFI raises intriguing questions about the broader systemic effects of

MECP2 mutations, suggesting they may influence not only neuronal growth but also bone metabolism and remodeling.

MECP2 has been implicated in the regulation of osteoblast and osteoclast activity, and its dysfunction could plausibly result in abnormal bone remodeling and cranial hyperostosis [

6,

7]. The thickening of the frontal bone, as observed in this case, may therefore represent a previously underrecognized manifestation of the systemic effects of

MECP2 mutations. Further research is warranted to elucidate the molecular mechanisms linking

MECP2 dysfunction to bone remodeling, cranial anomalies, and potential systemic sequelae in Rett syndrome.

Macrocephaly and HFI in this patient may also reflect the combined influence of hormonal factors and medication use. While Rett syndrome is occasionally associated with central precocious puberty, this phenomenon has been rarely documented in the literature [

8]. The hormonal dysregulation inherent to precocious puberty, as well as its treatment with leuprorelin acetate, may have contributed to the observed anomalies in cranial development and bone remodeling [

9]. Furthermore, the long-term administration of valproate, an ASM known to affect bone metabolism and contribute to conditions such as osteopenia, could have exacerbated these findings [

10]. This interplay between genetic mutations, hormonal influences, and the effects of chronic medication highlights the multifactorial nature of phenotypic variability in Rett syndrome and underscores the need for a holistic and multidisciplinary approach to patient evaluation. It is known that epileptic seizures associated with Rett syndrome are often poorly controlled and present as intractable epilepsy, even with three or more multiple-drug ASM regimens [

11]. Recently, however, there have been promising reports of controlled epileptic seizures in Rett syndrome with the use of newer therapies, including perampanel [

12] and cannabinoid-based treatments [

13,

14]. In addition, there are reports of deep brain stimulation therapy being effective in maintaining epilepsy and intellectual performance in Rett syndrome [

15]. Hyperventilation with Tachypnea and Hypoventilation with apnea, which must be differentiated from epileptic seizures, have been reported in Rett syndrome as well as in central apnea such as Prader-Willi syndrome [

16].

When confronted with atypical features such as macrocephaly, clinicians must consider differential diagnoses to rule out other conditions that may mimic or overlap with Rett syndrome.

MECP2 duplication syndrome, primarily affecting males, can present with macrocephaly, hypotonia, and developmental delay, resembling some aspects of Rett syndrome [

17]. Similarly,

PTEN hamartoma tumor syndrome (PHTS) is characterized by macrocephaly, autism spectrum disorder, and an increased risk of malignancies, distinguishing it from Rett syndrome [

18]. Another differential diagnosis is Sotos syndrome, a condition marked by macrocephaly, overgrowth, and developmental delay, which notably lacks the stereotypic hand movements that are pathognomonic of Rett syndrome [

10]. These differential considerations emphasize the necessity of detailed phenotypic evaluations, genetic testing, and interdisciplinary collaboration to arrive at an accurate diagnosis and implement optimal care.

The co-occurrence of macrocephaly, HFI, and central precocious puberty in this case is exceedingly rare and, to the best of our knowledge, remains sparsely reported in the literature. Such cases contribute valuable insights into the phenotypic heterogeneity of Rett syndrome and its interactions with systemic factors, particularly regarding hormonal and skeletal systems. Further investigation into these atypical presentations is crucial for advancing our understanding of Rett syndrome’s pathophysiology and for optimizing individualized care strategies for patients with rare and complex presentations.

4. Conclusions

This case expands the phenotypic spectrum of Rett syndrome by documenting macrocephaly and HFI, features rarely associated with this condition. These findings emphasize the need for further research into the systemic effects of MECP2 mutations, particularly their roles in cranial growth and bone metabolism. Understanding these atypical manifestations will enhance diagnostic precision and support the development of personalized treatment strategies. Additionally, recognizing differential diagnoses in patients with overlapping features like macrocephaly is essential for ensuring accurate diagnosis and effective management.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.I.; original draft preparation, G.I.; visualization, G.I. and S.K.; supervision, H.S.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from parents of the patient in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Neul, J.L.; Kaufmann, W.E.; Glaze, D.G.; Christodoulou, J.; Clarke, A.J.; Bahi-Buisson, N.; Leonard, H.; Bailey, M.E.S.; Schanen, N.C.; Zappella, M.; et al. Revised diagnostic criteria for Rett syndrome. Ann Neurol. 2010, 68, 944–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amir, R.E.; et al. Rett syndrome is caused by mutations in X-linked MECP2, encoding methyl-CpG-binding protein 2. Nat Genet. 1999, 23, 185–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hagberg, B.; et al. Rett syndrome: Clinical and biological aspects. Acta Paediatr Scand. 1985, 74, 753–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chahrour, M.; Zoghbi, H.Y. The story of Rett syndrome: from clinic to neurobiology. Neuron. 2007, 56, 422–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- She, R.; Szakacs, J. Hyperostosis frontalis interna: case report and review of literature. Ann Clin Lab Sci. 2004, 34, 206–208. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Valentina Conti, Anna Gandaglia, Francesco Galli, Mario Tirone, Elisa Bellini, Lara Campana, Charlotte Kilstrup-Nielsen, Patrizia Rovere-Querini, Silvia Brunelli, Nicoletta Landsberger. MeCP2 Affects Skeletal Muscle Growth and Morphology through Non Cell-Autonomous Mechanisms. PLoS One 2015, 10, e0130183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carla Caffarelli, Stefano Gonnelli, Maria Dea Tomai Pitinca, Silvia Camarri, Antonella Al Refaie, Joussef Hayek, Ranuccio Nuti. Methyl-CpG-binding protein 2 (MECP2) mutation type is associated with bone disease severity in Rett syndrome. BMC Med Genet 2020, 21, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulrike Bernstein, Stephanie Demuth, Oliver Puk, Birgit Eichhorn, Solveig Schulz. Novel MECP2 Mutation c.1162_1172del; p.Pro388* in Two Patients with Symptoms of Atypical Rett Syndrome. Mol Syndromol. 2019, 10, 223–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Esch, H. MECP2 duplication syndrome. Mol Syndromol. 2012, 2, 128–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatton-Brown, K.; et al. Sotos syndrome. Eur J Hum Genet. 2007, 15, 264–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulina Kyriakopoulos, Vanda McNiven, Melissa T Carter, Peter Humphreys, David Dyment, Tadeu A Fantaneanu. Atypical Rett Syndrome and Intractable Epilepsy with Novel GRIN2B Mutation. Child Neurol Open. 2018, 5, 2329048X18787946. [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, S.; Amamoto, M.; Takahashi, T.; Tomita, I.; Yuge, K.; Hara, M.; Iwama, K.; Matsumoto, N.; Matsuishi, T. Perampanel markedly improved clinical seizures in a patient with a Rett-like phenotype and 960-kb deletion on chromosome 9q34.11 including the STXBP1. Clin Case Rep. 2022, 10, e05811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hurley, E.N.; Ellaway, C.J.; Johnson, A.M.; Truong, L.; Gordon, R.; Galettis, P.; Martin, J.H.; Lawson, J.A. Efficacy and safety of cannabidivarin treatment of epilepsy in girls with Rett syndrome: A phase 1 clinical trial. Epilepsia 2022, 63, 1736–1747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desnous, B.; Beretti, T.; Muller, N.; Neveu, J.; Villeneuve, N.; Lépine, A.; Daquin, G.; Milh, M. Efficacy and tolerance of cannabidiol in the treatment of epilepsy in patients with Rett syndrome. Epilepsia Open 2024, 9, 397–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, J.F.; Sheth, S.A.; McKhann, G.M. , 2nd. Using Deep Brain Stimulation to Rescue Memory in Rett Syndrome. Neurosurgery. 2016, 78, N16–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallego, J. Genetic diseases: congenital central hypoventilation, Rett, and Prader-Willi syndromes. Compr Physiol. 2012, 2, 2255–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, J.; et al. Partial NSD1 deletions cause 5% of Sotos syndrome and are readily identifiable by multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification. J Med Genet. 2005, 42, e56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaymakcalan, H.; Kaya, İ.; Cevher Binici, N.; Nikerel, E.; Özbaran, B.; Görkem Aksoy, M.; Erbilgin, S.; Özyurt, G.; Jahan, N.; Çelik, D.; et al. Ercan-Sencicek AG. Mol Genet Genomic Med. 2021, 9, e1739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).