Submitted:

22 January 2025

Posted:

22 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- By combining the zero-order optimization and adaptive gradient method, we have proposed a novel faster zero-order adaptive federated learning algorithm, called FAFedZO, it can eliminate the reliance on gradient information and accelerate convergence at the same time.

- We conducted a theoretical analysis of the proposed zeroth-order adaptive algorithm and provided a convergence analysis framework under some mild assumptions, demonstrating its convergence. Additionally, we have analyzed the computational complexity and convergence rate of the algorithm.

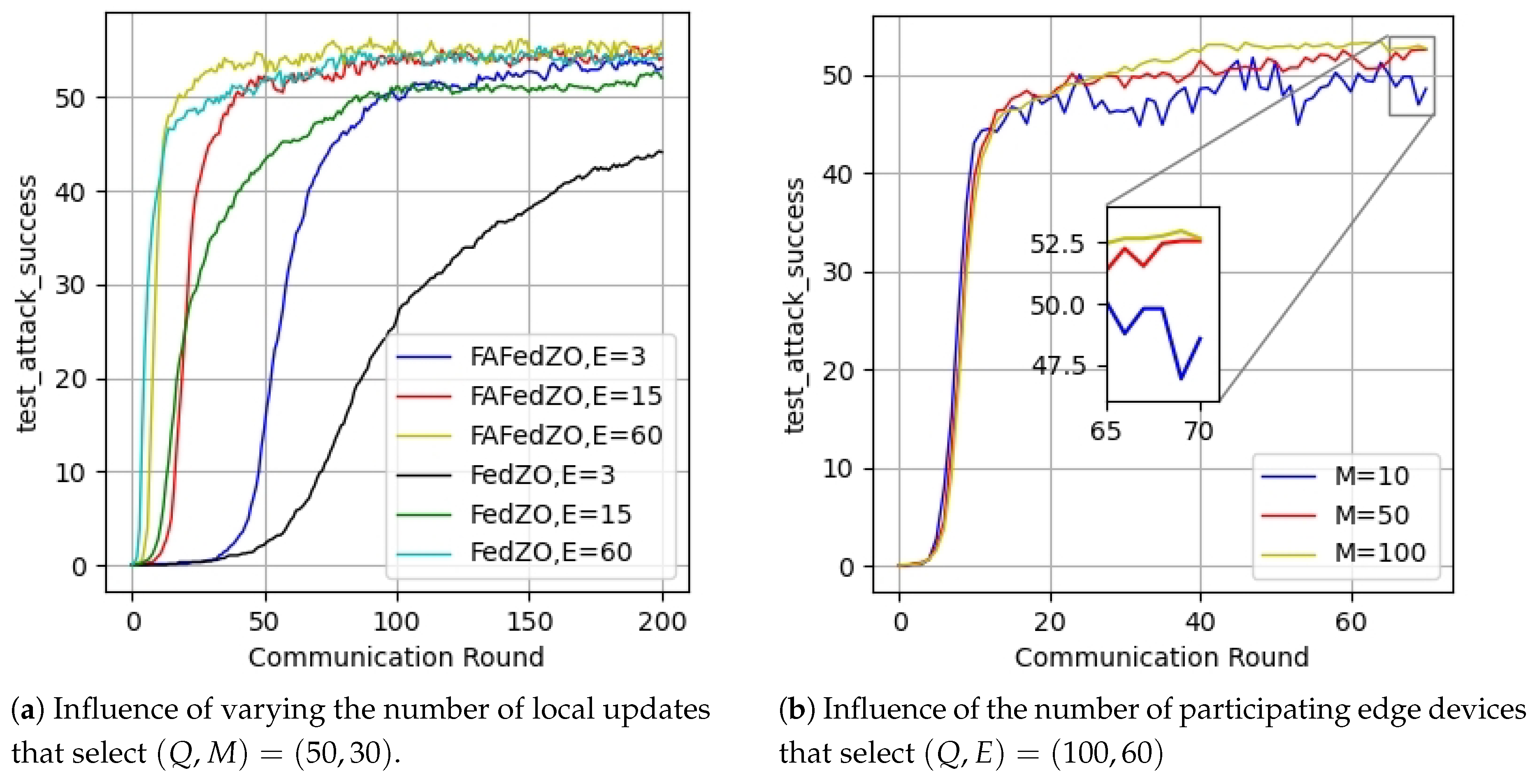

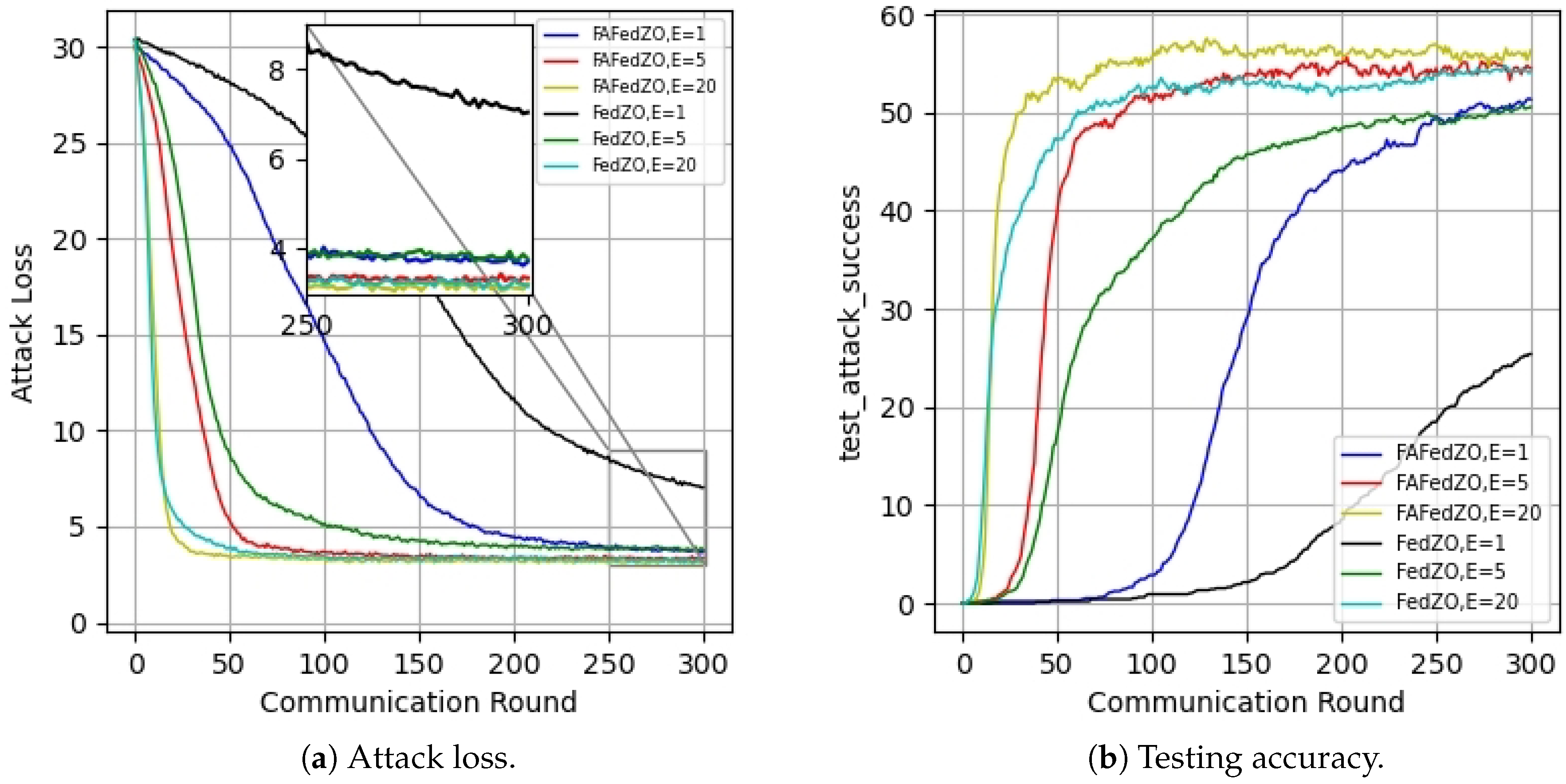

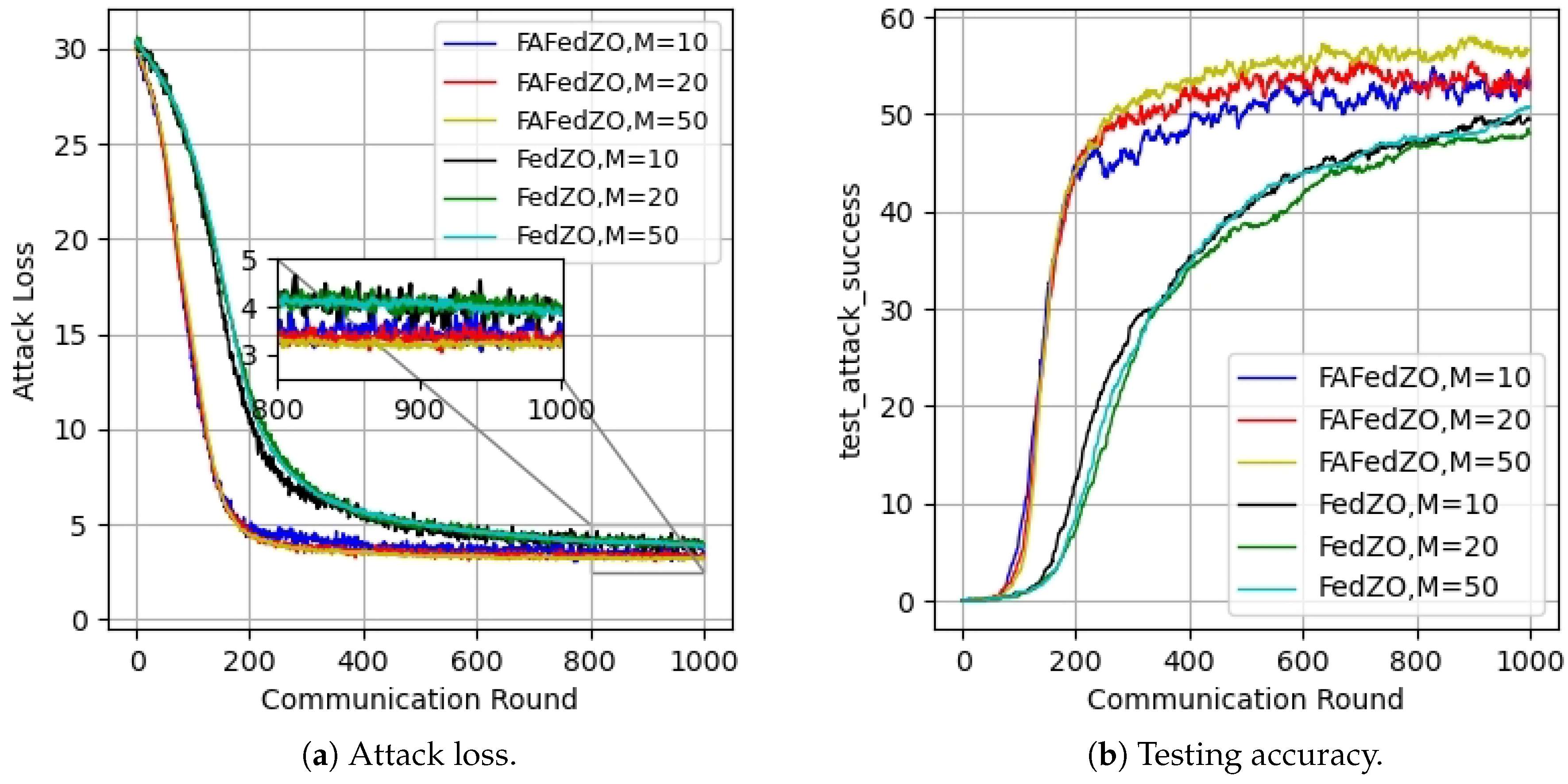

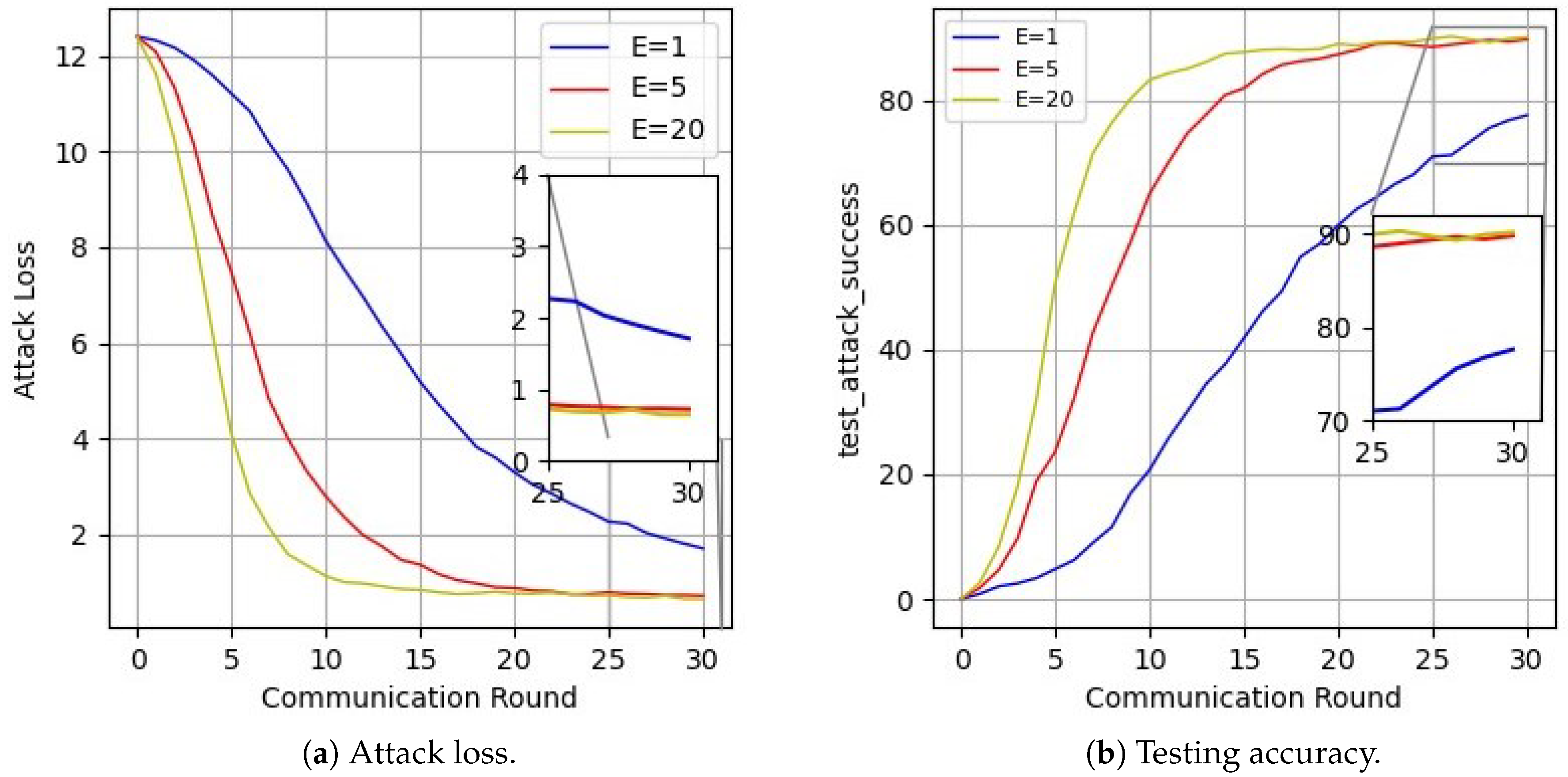

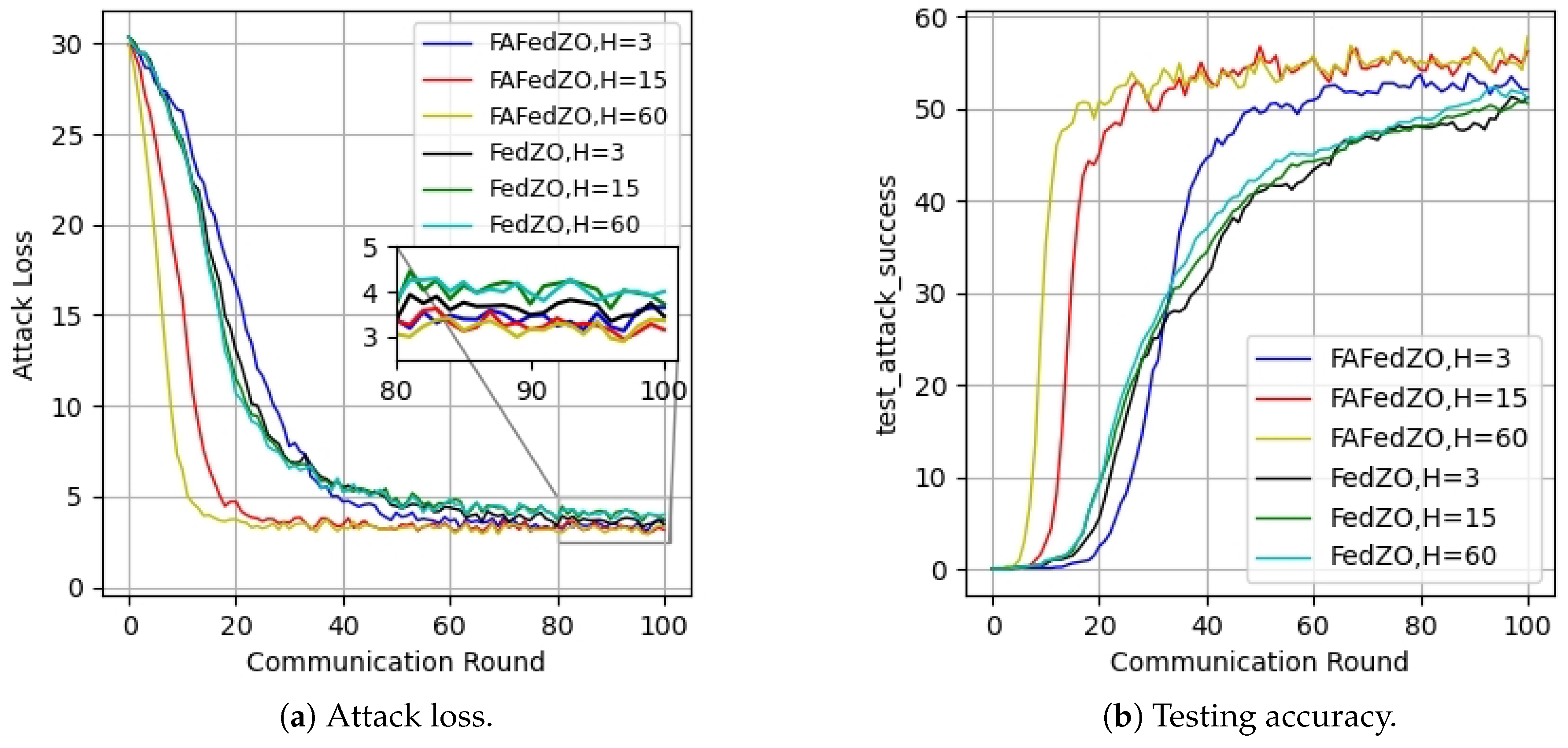

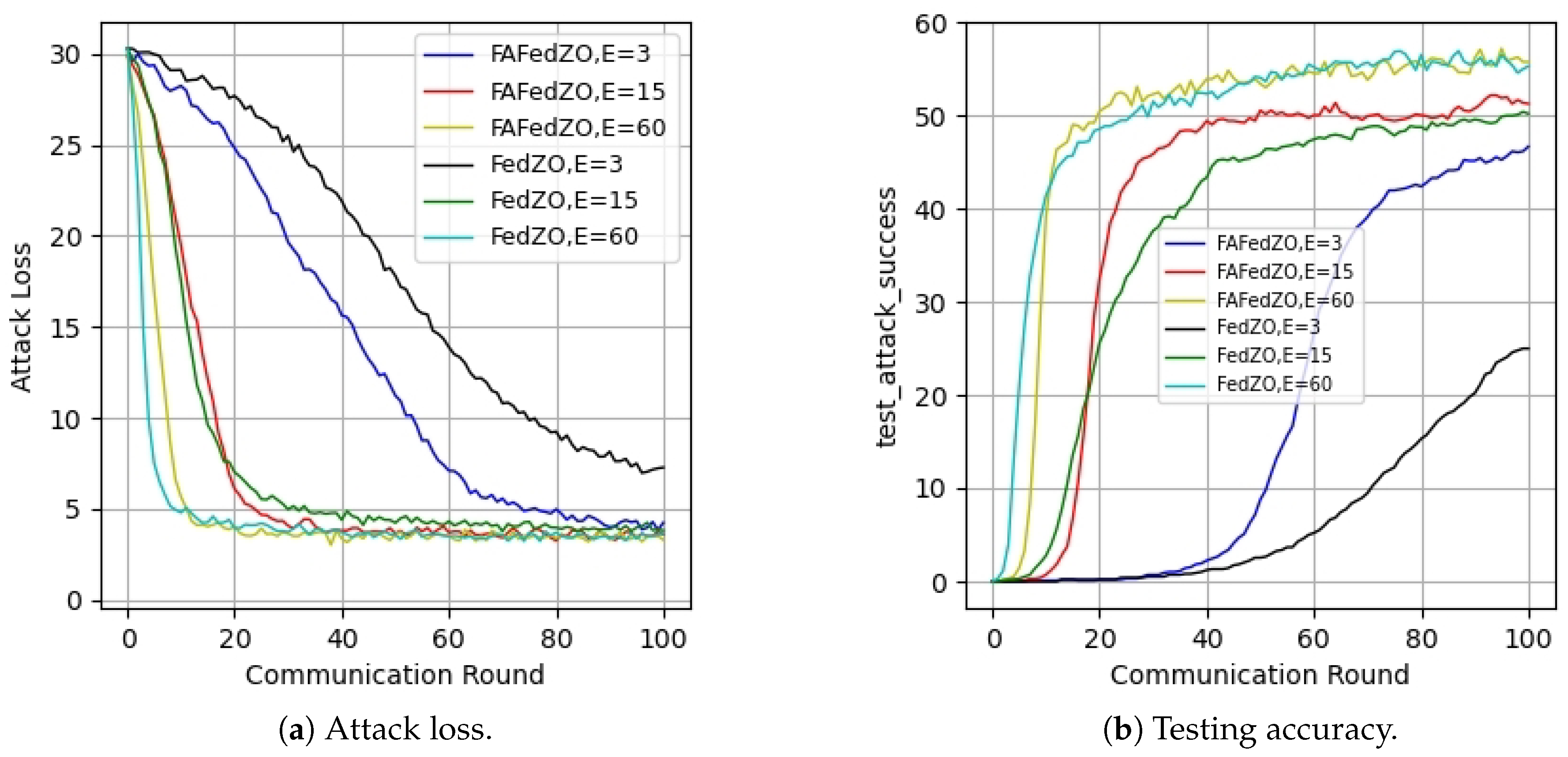

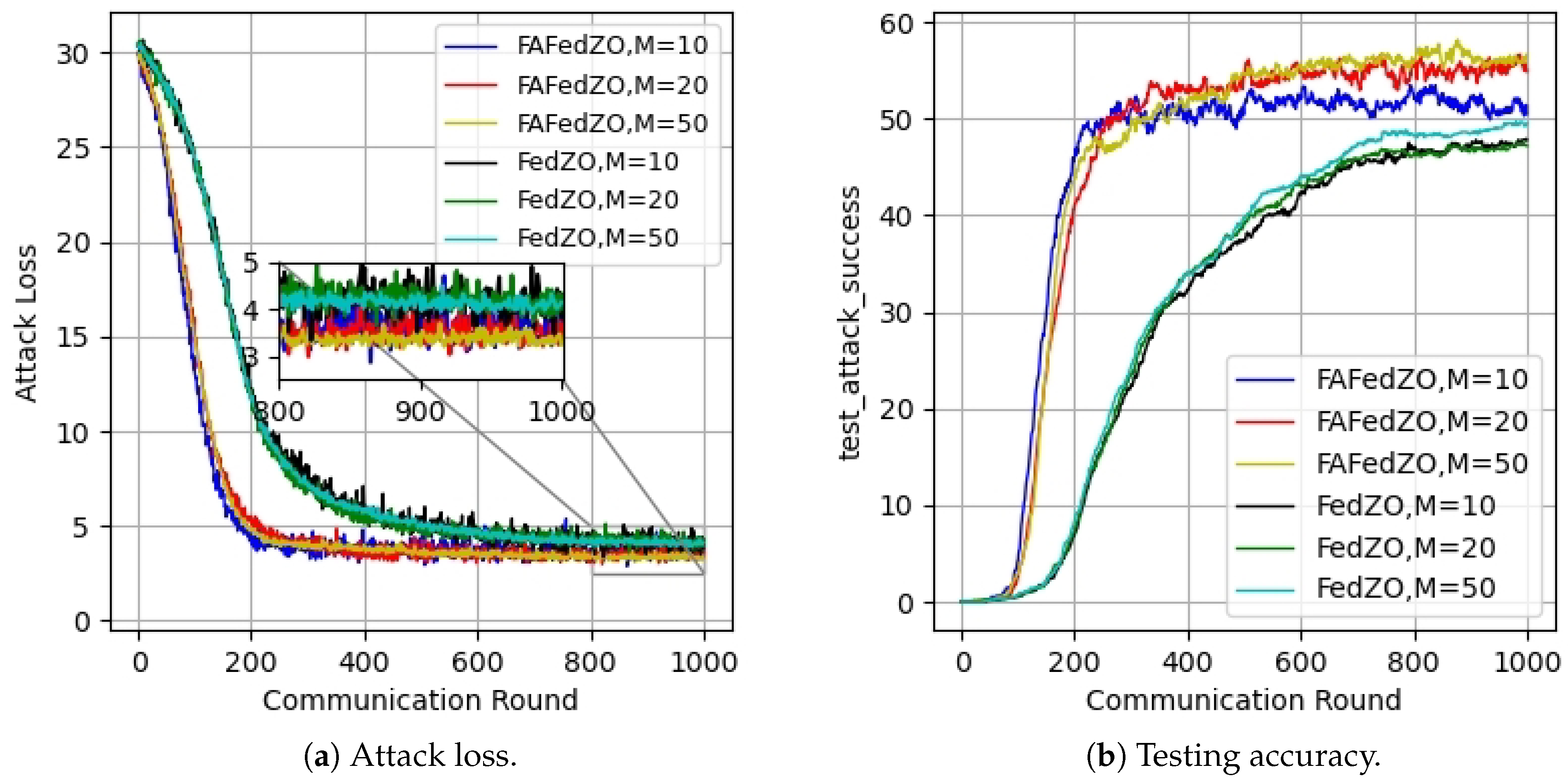

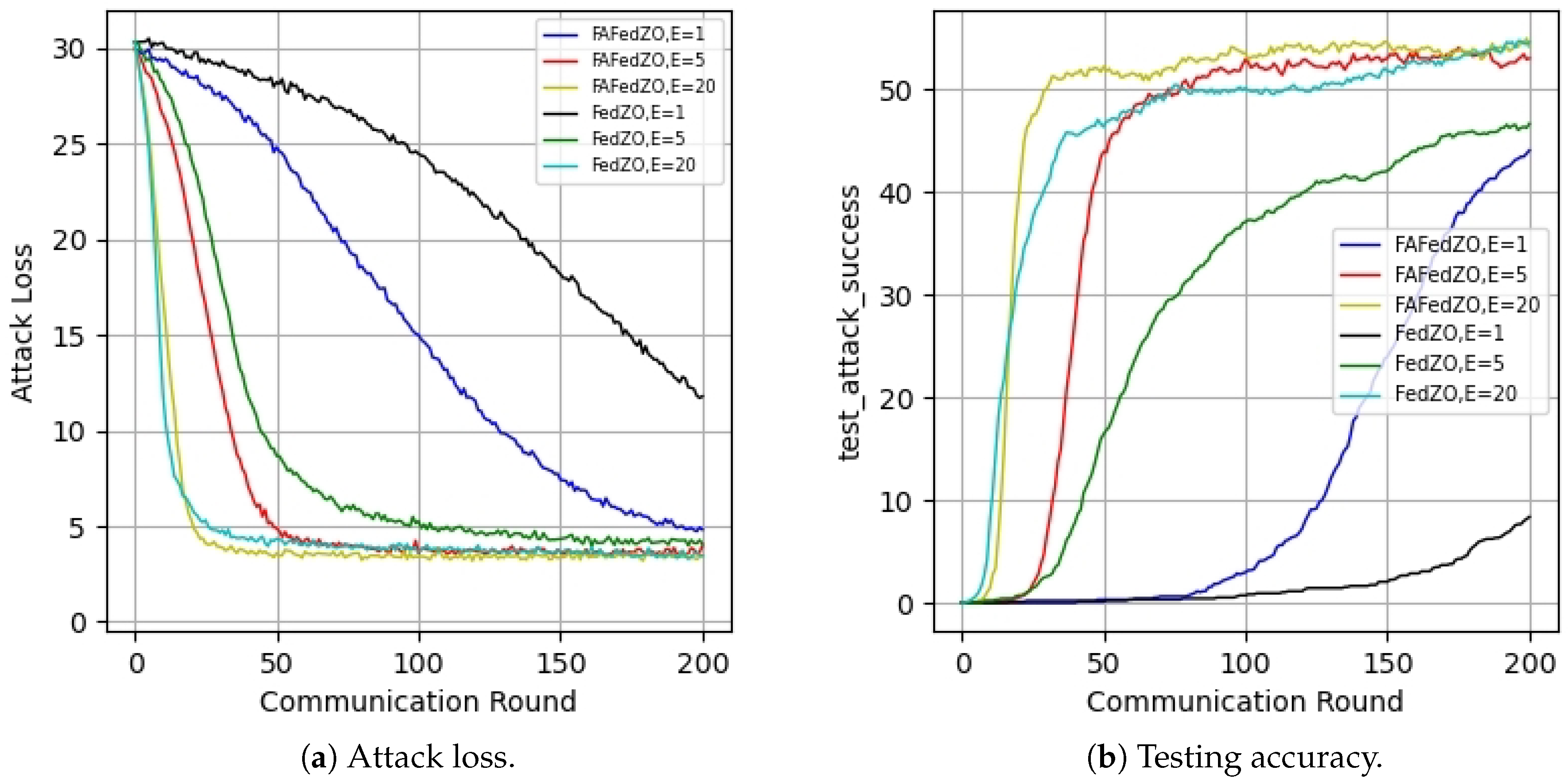

- Extensive comparative experimental results under both IID and non-IID settings have confirmed the efficacy of our proposed FAFedZO algorithm on the MNIST and CIFAR-10 datasets. when gradient information is not available, it can achieve faster convergence speed.

2. Related Work

3. Problem Formulation and Algorithm Design

3.1. Federated Optimization Problem Formulation

3.2. Algorithm Design of FAFedZO

4. Convergence Analysis of FAFedZO Method

5. Experimental Results

6. Discussion

7. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- McMahan, B.; Moore, E.; Ramage, D.; Hampson, S.; y Arcas, B.A. Communication-efficient learning of deep networks from decentralized data. In Proceedings of the Artificial intelligence and statistics; 2017; pp. 1273–1282. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, Y.; Yang, K.; Yang, Z.; Zhou, Y. Mobile edge artificial intelligence: Opportunities and challenges 2021.

- Yang, L.; Tan, B.; Zheng, V.W.; Chen, K.; Yang, Q. Federated recommendation systems. Federated Learning: Privacy and Incentive, 2020, pp. 225–239.

- Yang, K.; Shi, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Yang, Z.; Fu, L.; Chen, W. Federated machine learning for intelligent IoT via reconfigurable intelligent surface. IEEE network 2020, 34, 16–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, J.; Smith, J.S.; Kira, Z. Fedfor: Stateless heterogeneous federated learning with first-order regularization. arXiv.2209.10537 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, M.; Sapra, K.; Fidler, S.; Yeung, S.; Alvarez, J.M. Personalized federated learning with first order model optimization 2021.

- Elbakary, A.; Issaid, C.B.; Shehab, M.; Seddik, K.G.; ElBatt, T.A.; Bennis, M. Fed-Sophia: A Communication-Efficient Second-Order Federated Learning Algorithm. arXiv.2406.06655 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, Z.; Low, B.K.H.; Jaillet, P. Federated Bayesian optimization via Thompson sampling. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2020, 33, 9687–9699. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, W.; Yu, Z.; Jiang, Y.; Shi, Y.; Jones, C.N.; Zhou, Y. Communication-efficient stochastic zeroth-order optimization for federated learning. IEEE Transactions on Signal Processing 2022, 70, 5058–5073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Ying, B.; Liu, Z.; Yang, H. Achieving Dimension-Free Communication in Federated Learning via Zeroth-Order Optimization. arXiv.2405.15861 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Maritan, A.; Dey, S.; Schenato, L. FedZeN: Quadratic convergence in zeroth-order federated learning via incremental Hessian estimation. In Proceedings of the 2024 European Control Conference; 2024; pp. 2320–2327. [Google Scholar]

- Staib, M.; Reddi, S.; Kale, S.; Kumar, S.; Sra, S. Escaping saddle points with adaptive gradient methods. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning; 2019; pp. 5956–5965. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; Li, X.; Li, P. Toward communication efficient adaptive gradient method. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2020 ACM-IMS on Foundations of Data Science Conference, 2020, pp. 119–128.

- Reddi, S.; Charles, Z.; Zaheer, M.; Garrett, Z.; Rush, K.; Konečnỳ, J.; Kumar, S.; McMahan, H.B. Adaptive federated optimization. arXiv:2003.00295, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Lin, L.; Chen, J. Communication-efficient adaptive federated learning. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning; 2022; pp. 22802–22838. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Liu, Q.; Liang, H.; Joshi, G.; Poor, H.V. A novel framework for the analysis and design of heterogeneous federated learning. IEEE Transactions on Signal Processing 2021, 69, 5234–5249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Sahu, A.K.; Zaheer, M.; Sanjabi, M.; Talwalkar, A.; Smith, V. Federated optimization in heterogeneous networks. Proceedings of Machine learning and systems 2020, 2, 429–450. [Google Scholar]

- Karimireddy, S.P.; Kale, S.; Mohri, M.; Reddi, S.; Stich, S.; Suresh, A.T. Scaffold: Stochastic controlled averaging for federated learning. In Proceedings of the International conference on machine learning; 2020; pp. 5132–5143. [Google Scholar]

- Pathak, R.; Wainwright, M.J. FedSplit: An algorithmic framework for fast federated optimization. Advances in neural information processing systems 2020, 33, 7057–7066. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Hong, M.; Dhople, S.; Yin, W.; Liu, Y. Fedpd: A federated learning framework with adaptivity to non-iid data. IEEE Transactions on Signal Processing 2021, 69, 6055–6070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Roosta, F.; Xu, P.; Mahoney, M.W. Giant: Globally improved approximate newton method for distributed optimization. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2018, 31. [Google Scholar]

- Li, T.; Sahu, A.K.; Zaheer, M.; Sanjabi, M.; Talwalkar, A.; Smithy, V. Feddane: A federated newton-type method. In Proceedings of the 2019 53rd Asilomar Conference on Signals, Systems, and Computers; 2019; pp. 1227–1231. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, A.; Huang, H. Coordinating momenta for cross-silo federated learning. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, 2022, Vol. 36, pp. 8735–8743.

- Das, R.; Acharya, A.; Hashemi, A.; Sanghavi, S.; Dhillon, I.S.; Topcu, U. Faster non-convex federated learning via global and local momentum. In Proceedings of the Uncertainty in Artificial Intelligence; 2022; pp. 496–506. [Google Scholar]

- Khanduri, P.; Sharma, P.; Yang, H.; Hong, M.; Liu, J.; Rajawat, K.; Varshney, P. Stem: A stochastic two-sided momentum algorithm achieving near-optimal sample and communication complexities for federated learning. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2021, 34, 6050–6061. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, W.; Han, H.; Zhang, Y.; Mu, J. Federated split learning for sequential data in satellite-terrestrial integrated networks. Information Fusion 2024, 103, 102141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Han, H.; Zhang, Y.; Mu, J.; Shankar, A. Intrusion Detection with Federated Learning and Conditional Generative Adversarial Network in Satellite-Terrestrial Integrated Networks. Mobile Networks and Applications, 2024, pp. 1–14.

- Tang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Li, N. Distributed zero-order algorithms for nonconvex multiagent optimization. IEEE Transactions on Control of Network Systems 2020, 8, 269–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolakakis, K.; Haddadpour, F.; Kalogerias, D.; Karbasi, A. Black-box generalization: Stability of zeroth-order learning. Advances in neural information processing systems 2022, 35, 31525–31541. [Google Scholar]

- Balasubramanian, K.; Ghadimi, S. Zeroth-order (non)-convex stochastic optimization via conditional gradient and gradient updates. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2018, 31. [Google Scholar]

- Mhanna, E.; Assaad, M. Rendering Wireless Environments Useful for Gradient Estimators: A Zero-Order Stochastic Federated Learning Method. arXiv.2401.17460 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Diederik, P.K. Adam: A method for stochastic optimization 2014.

- Duchi, J.; Hazan, E.; Singer, Y. Adaptive subgradient methods for online learning and stochastic optimization. Journal of machine learning research 2011, 12. [Google Scholar]

- Ling, X.; Fu, J.; Wang, K.; Liu, H.; Chen, Z. Ali-dpfl: Differentially private federated learning with adaptive local iterations. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 25th International Symposium on a World of Wireless, Mobile and Multimedia Networks; 2024; pp. 349–358. [Google Scholar]

- Cong, Y.; Qiu, J.; Zhang, K.; Fang, Z.; Gao, C.; Su, S.; Tian, Z. Ada-FFL: Adaptive computing fairness federated learning. CAAI Transactions on Intelligence Technology 2024, 9, 573–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Zhu, S.; Chen, W.; Huang, Z. FedAFR: Enhancing Federated Learning with adaptive feature reconstruction. Computer Communications 2024, 214, 215–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; He, Z.; Gu, X.; Xu, H.; Ren, S. AFedAvg: Communication-efficient federated learning aggregation with adaptive communication frequency and gradient sparse. Journal of Experimental & Theoretical Artificial Intelligence 2024, 36, 47–69. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, X.; Jiang, B.; Zhang, S. On the information-adaptive variants of the ADMM: an iteration complexity perspective. Journal of Scientific Computing 2018, 76, 327–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Huang, F.; Hu, Z.; Huang, H. Faster adaptive federated learning. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the AAAI conference on artificial intelligence, 2023, Vol. 37, pp. 10379–10387.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).