Submitted:

21 January 2025

Posted:

22 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

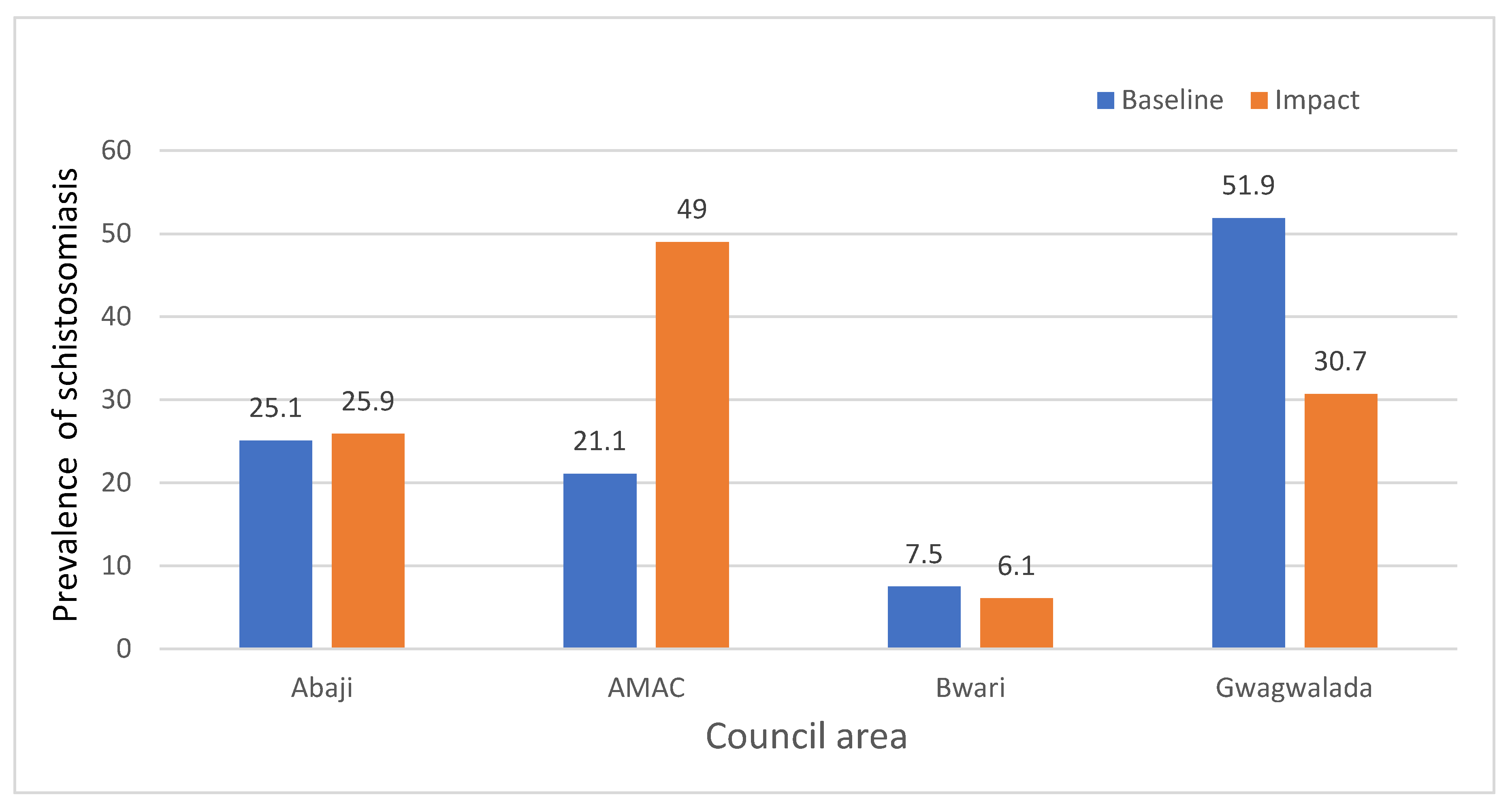

Introduction: One of the global strategies for elimination of schistosomiasis is by mass treatment of school-aged children with a single oral dose of praziquantel (40mg/kg) without a prior individual diagnosis, with a target of >75% treatment coverage. This study was conducted to determine the endemicity of schistosomiasis among school-aged children and adults in Abuja, Nigeria. Methods: A total of 1,370 participants were recruited which consisted of 667 (48.67%) males and 703 (51.31%) females. Urine and stool specimens were collected from each participant and analyzed using standard procedures. Results: The overall prevalence of schistosomiasis was 27.5% in this study with Abuja Municipal having the highest prevalence of 49% while the least (6.1%) was reported in Bwari LCA. The prevalence of schistosomiasis significantly differs (P<0.05) between the area councils. The location of communities significantly affected the prevalence of schistosomiasis in Abaji, AMAC, and Gwagwalada LCAs (P<0.005). The Schistosoma recovered in this study were S. haematobium and S. mansoni. The prevalence of schistosomiasis increased from the baseline of 21.1% to 49% in Gwagwalada LCA. Gender significantly affected the prevalence of schistosomiasis as more males were infected (33.1%) than their female counterparts (22.2%) (P<0.05). The prevalence of schistosomiasis was 31% and 23.9% among SAC and adults, respectively. The participants’ activities in the river significantly affected the prevalence of schistosomiasis in this study (P< 0.05). Conclusions: The clamour for urgent government and non-government intervention through alternate sources of water like boreholes or pipe-borne water, as well as implementing a behavioural change campaign across the communities to prevent the recurrence, are advocated.

Keywords:

Introduction

Materials and Methods

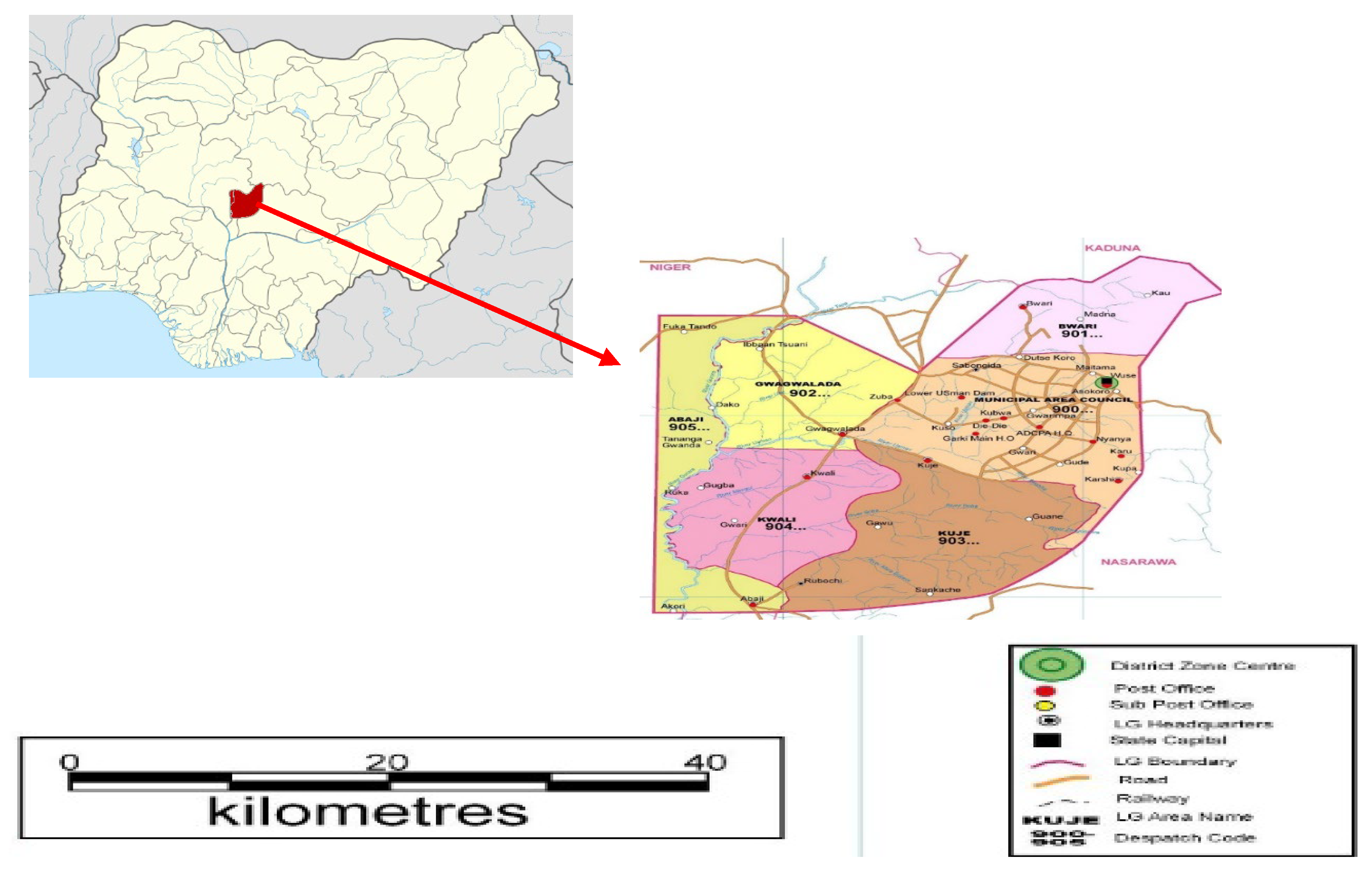

Study Area

Study Population

Specimen Collection

Urine Filtration Technique

Kato-Katz Technique for Stool Examination

Statistical Analysis

Ethical Consideration and Consent

Results

Prevalence and Intensity by Schistosoma Species

| Schistosoma | haematobium |

| LCA No. tested No. Positive Light Heavy Egg count/ (%) infection infection Mean intensity/ (<50 eggs/10 ml) 10 ml urine (%) |

|

| Abaji 247 33(13.4%) 30(30.9) 3(1.2) 621/19 (LI) AMAC 306 138(45.1) 92(66.7) 46(33.3) 14,838/108 (HI) Bwari 358 11(3.1) 10(90.9) 1(9.1) 212/19 (LI) Gwagwalada 459 103(22.4) 85(82.5) 18(17.5) 3,237/31 (LI) |

| Schistosoma | mansoni |

| LCA No. tested No. Light Moderate Heavy Egg count/ Positive infection infection infection mean intensity/g (1-99epg) (100-399 epg) (> 400epg) of stool (%) |

|

| Abaji 247 36(14.6) 22(61.1) 11(30.6) 3(8.3) 6,024/167 (MI) AMAC 306 33(10.8) 6(18.2) 20(60.6) 7(21.2) 8,736/265 (MI) Bwari 358 12(3.4) 6(50) 5(41.7) 1(8.3) 2,304/192 (MI) Gwagwalada 459 53(11.5) 12(22.6) 30(56.6) 11(20.8) 13,104/247 (MI) |

| LGA | Total Sampled | Male | Female | ||

| Sampled | Number positive (Prevalence) | Sampled | Number positive (Prevalence) | ||

| Abaji | 247 | 121 | 37 (30.6%) | 126 | 27 (21.4%) |

| AMAC | 306 | 158 | 82 (51.9%) | 148 | 68 (45.9%) |

| Bwari | 358 | 148 | 12 (8.1%) | 210 | 10 (4.8%) |

| Gwagwalada | 459 | 240 | 90 (37.5%) | 219 | 51 (23.3%) |

| Grand Total | 1370 | 667 | 221 (33.1%) | 703 | 156 (22.2%) |

Discussion

Limitations of the Study

Recommendation

Conclusion

Acknowledgments

Conflict of Interests

References

- McManus DP, Dunne DW, Sacko M, et al. Schistosomiasis. Nature Rev Dis Primers. 2018; 4(1). [CrossRef]

- Hotez PJ, Alvarado M, Basáñez M-G, et al. The Global Burden of Disease Study 2010: Interpretation and Implications for the Neglected Tropical Diseases. PLoS Neglect Trop Dis. 2014; 8(7): e2865.

- World Health Organization. Schistosomiasis: fact sheet. 2020; Available: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/schistosomiasis.

- Verjee MA. Schistosomiasis: Still a Cause of Significant Morbidity and Mortality. Res Rep Trop Med. 2019; 10: 153-163.

- LoVerde PT. Schistosomiasis. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2019; 1154: 45-70.

- Ezeamama AE, Bustinduy AL, Nkwata AK. et al. Cognitive deficits and educational loss in children with schistosome infection-A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Neglect Trop Dis. 2018; 12(1). [CrossRef]

- Olliaro PL, Coulibaly JT, Garba A, et al. Efficacy and safety of single-dose 40 mg/kg oral praziquantel in the treatment of schistosomiasis in preschool-age versus school-age children: An individual participant data meta-analysis. PLoS Neglect Trop Dis. 2020; 14(6). [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Fifty-fourth World Health Assembly, Geneva, 14-22 May 2001: resolutions and decisions. 2001; https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/260183.

- World Health Organization. GUIDELINE on control and elimination of human schistosomiasis 2022; ISBN 978-92-4-004160-8 (electronic version).

- Oluwole AS, Ekpo UF, Nebe OJ, et al. The new WHO guideline for control and elimination of human Schistosomiasis: Implication for the Schistosomiasis elimination programme in Nigeria. Infect Dis Poverty, 2022. [CrossRef]

- FMOH. Report on Epidemiological Mapping of Schistosomiasis and Soil Transmitted Helminthiasis in 19 States and the FCT, Federal Ministry of Health, Nigeria. 2015; 76.

- Nduka F, Nebe OJ, Njepuome N, et al. Epidemiological mapping of schistosomiasis and soil-transmitted helminthiasis for intervention strategies in Nigeria. Nig J Parasitol. 2019; 40(2): 124-131.

- National Population Commission. Nigerian Population Census Report. National Population Commission, Abuja. 2006; 21-27.

- Bartlett JE, Kotrlik JW, Higgins CC. Organizational Research: Determining Appropriate Sample Size in Survey Research. Inform Technol, Learn, Perform J. 2001; 19: 43-50.

- World Health Organization. Report of a Meeting to Review the Results of Studies on the Treatment of Schistosomiasis in Preschool-age Children, WHO. 2010.

- Krauth SJ, Greter H, Stete K, et al. All that is blood is not schistosomiasis: experiences with reagent strip testing for urogenital schistosomiasis with special consideration to very-low prevalence settings. Parasite Vectors. 2015; 8: 584.

- Lengeler C, Mshinda H, Morona D, et al. Urinary schistosomiasis : testing with urine filtration and reagent sticks for haematuria provides a comparable prevalence estimate. Acta Trop. 1993; 53(1): 39-50.

- World Health Organization. Bench Aids for the diagnosis of intestinal parasites (Original version 1994, corrected in 2012). 2012.

- Harris-Roxas B, Viliani F, Bond A, et al. Health impact assessment: the state of the art. Impact Assessment and Project Appraisal. 2012; 30(1): 43-52.

- Mushi V, Zacharia A, Shao M, et al. Persistence of Schistosoma haematobium transmission among school children and its implication for the control of urogenital schistosomiasis in Lindi, Tanzania. PloS One. 2022; 17(2): e0263929.

- Malibiche D, Mushi V, Justine NC, et al. Prevalence and factors associated with ongoing transmission of Schistosoma haematobium after 12 rounds of Praziquantel Mass Drug Administration among school-aged children in Southern Tanzania. Parasite Epidemiol Control. 2023; 23: e00323.

- Oluwole AS, Adeniran AA, Mogaji HO, et al. Prevalence, intensity and spatial co-distribution of schistosomiasis and soil transmitted helminths infections in Ogun state, Nigeria. Parasitol Open 2018; 4(8): 1–9.

- Alabi P, Oladejo SO, Odaibo AB. Prevalence and intensity of urinary schistosomiasis in Ogun state, Southwest, Nigeria. J Public Health Epidemiol. 2018; 10(11): 413-417.

- Oyeyemi OT, Jeremias WJ, Grenfell RFQ. Schistosomiasis in Nigeria: Gleaning from the past to improve current efforts towards control. One Health. 2020; 14(11). [CrossRef]

- Dawaki S, Al-Mekhlafi HM, Ithoi I, et al. The Menace of Schistosomiasis in Nigeria: Knowledge, Attitude, and Practices Regarding Schistosomiasis among Rural Communities in Kano State. PLoS ONE. 2015; 10(11), e0143667. [CrossRef]

- Ajakaye OG, Olusi TA, Oniya MO. Environmental factors and the risk of urinary schistosomiasis in Ile Oluji/Oke Igbo local government area of Ondo State. Parasite Epidemiol Control. 2016; 1(2): 98-104.

- Schafer TW, Hale BR. Gastrointestinal Complications of Schistosomiasis. Current Gastroenterology Reports. 2001; 3: 293–303.

- Faust CL, Osakunor DNM, Downs JA et al. Schistosomiasis Control: Leave No Age Group Behind. Trends Parasitol. 2020; 36(7): 582-592.

- Woldeyohannes D, Sahiledengle B, Tekalegnb Y, et al. Prevalence of Schistosomiasis (S. mansoni and S. haematobium) and its association with gender of school age children in Ethiopia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Parasite Epidemiol Control. 2021; 13. [CrossRef]

- Balogun JB, Adewale B, Balogun SU, et al. Prevalence and Associated Risk Factors of Urinary Schistosomiasis among Primary School Pupils in the Jidawa and Zobiya Communities of Jigawa State, Nigeria. Ann Global Health. 2022; 88(1): 1–14.

- Oluwole AS, Bettee AK, Nganda MM, et al. A quality improvement approach in co-developing a primary healthcare package for raising awareness and managing female genital schistosomiasis in Nigeria and Liberia. Intern Health. 2023; 15(1): 30-42.

- Masong M, Ozano K, Tagne MS, et al. Achieving equity in UHC interventions: who is left behind by neglected tropical disease programs in Cameroon?. Glob Health Action. 2021; 14(1): 1886457.

- Phillips AE, Ower AK, Mekete K, et al. Association between water, sanitation, and hygiene access and the prevalence of soil-transmitted helminth and schistosome infections in Wolayita, Ethiopia. Parasites Vectors, 2022; 15(1): 410.

- Evan SW. Water-based interventions for schistosomiasis control. Path Global Health. 2014; 108(5): 246-254.

- Grimes JE, Croll D, Harrison WE, et al. The relationship between water, sanitation and schistosomiasis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Neglect Trop Dis. 2014; 8(12): e3296.

- Campbell SJ, Biritwum NK, Woods G. et al. Tailoring water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) targets for soil-transmitted helminthiasis and schistosomiasis control. Trends Parasitol. 2018; 34(1): 53-63.

- Grimes JE, Croll D, Harrison WE, et al. The roles of water, sanitation and hygiene in reducing schistosomiasis: a review. Parasites Vectors. 2015; 8: 1-16.

- Kosinski KC, Kulinkina AV, Abrah AFA, et al. (2016). A mixed-methods approach to understanding water use and water infrastructure in a schistosomiasis-endemic community: case study of Asamama, Ghana. BMC Public Health. 2016; 16:1-10.

| LAC No. tested No. positive (%) P-value WHO Prevalence Category |

| Abaji 247 64 (25.9) <0.0001 Moderate AMAC 306 150 (49) Moderate Bwari 358 22 (6.1) Low Gwagwalada 459 141 (30.7) Moderate |

| Community | No. tested | No. positive | prevalence of schistosomiasis (%) | P-value | Prevalence level |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Abaji LCA Abaji Central |

48 |

24 |

50.0 |

High |

|

| Dogon Ruwa | 51 | 22 | 43.1 | Moderate | |

| Gawu | 50 | 4 | 8.0 | Low | |

| Rimba gwari | 48 | 2 | 4.2 | Low | |

| Yaba | 50 | 12 | 24.0 | Moderate | |

| Total | 247 | 64 | 25.9 | <0.0001* | Moderate |

| AMAC LCA | |||||

| Bassan Jiwa | 50 | 35 | 70.0 | High | |

| Gwagwa | 50 | 44 | 88.0 | High | |

| Karmo | 49 | 17 | 34.7 | Moderate | |

| Kpaipai | 55 | 15 | 27.3 | Moderate | |

| Rugan Fulani Dunamis | 50 | 23 | 46.0 | Moderate | |

| Toge Sabo | 52 | 16 | 30.8 | Moderate | |

| Total | 306 | 150 | 49.0 | <0.0001* | Moderate |

| BWARI LCA | |||||

| Byazhin | 51 | 7 | 13.7 | Moderate | |

| Dutse Alhaji | 50 | 4 | 8.0 | Low | |

| Jigo | 54 | 3 | 5.6 | Low | |

| Katampe | 52 | 5 | 9.6 | Low | |

| Kogo | 50 | 0 | 0.0 | Low | |

| Shere | 49 | 1 | 2.0 | Low | |

| War college Camp, Ushafa | 52 | 2 | 3.8 | Low | |

| Total | 358 | 22 | 6.1 | 0.0549 | Moderate |

| GWAGWALADA LCA | |||||

| Angwan Bassa | 50 | 36 | 72.0 | High | |

| Angwan Dodo | 50 | 14 | 28.0 | Moderate | |

| Dagiri | 54 | 22 | 40.7 | Moderate | |

| Dobi | 50 | 16 | 32.0 | Moderate | |

| Dukpa | 50 | 4 | 8.0 | Low |

|

| Ibwa | 50 | 7 | 14.0 | Moderate | |

| Kpakuru | 51 | 14 | 27.5 | Moderate | |

| Kpakuru Sarki | 50 | 6 | 12.0 | Moderate | |

| Paiko | 54 | 22 | 40.7 | Moderate | |

| Total | 459 | 141 |

30.7 |

0.00053* | Moderate |

| LAC | No. Examined | School-aged children | Adult | ||

| No. tested | Number positive (Prevalence) | No. tested | Number positive (Prevalence) | ||

| Abaji | 247 | 123 | 38 (30.9%) | 124 | 26 (21%) |

| AMAC | 306 | 149 | 87 (58.4%) | 157 | 63 (40.1%) |

| Bwari | 358 | 180 | 12 (6.7%) | 178 | 10 (5.6%) |

| Gwagwalada | 459 | 245 | 79 (32.2%) | 214 | 62 (29%) |

| Grand Total | 1370 | 697 | 216 (31.0%) | 673 | 161 (23.9%) |

| P<0.05 | |||||

| LAC | No. examined | School-aged children | Adult | ||||

| No. positive | Light infection (< 50 eggs per ml) | Heavy infection (> 50 eggs per ml) | No. positive | Light infection (< 50 eggs per ml) | Heavy infection (> 50 eggs per ml) | ||

| Abaji | 247 | 123 | 121 (98.4) | 2 (1.6) | 124 | 123 (99.2) | 1 (0.8) |

| AMAC | 306 | 149 | 244 (98.8) | 3 (1.2) | 157 | 133 (84.70 | 24 (15.3) |

| Bwari | 358 | 180 | 179 (99.4) | 1 (0.6) | 178 | 178 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Gwagwalada | 459 | 245 | 234 (95.5) | 11 (4.5) | 214 | 207 (96.7) | 7 (3.3) |

| Grand Total | 1370 | 697 | 661 (94.8) | 36 (5.2) | 673 | 641 (95.2) | 32 (4.8) |

| LAC | No. examined | School-aged children | Adult | ||||||

| No. positive | Light infection (1-99 epg) |

Moderate Infection (100-399 epg) | Heavy infection (>=400 epg) |

No. positive | Light infection (1-99 epg) |

Moderate Infection (100-399 epg) | Heavy infection (>=400 epg) |

||

| Abaji | 247 | 21 | 14 (66.7%) | 4(19.0%) | 3(14.3%) | 15 | 8(53.3%) | 7(46.7%) | 0(0%) |

| AMAC | 306 | 20 | 3(15.0%) | 13 (65.0%) | 4(20.0%) | 13 | 3(23.1%) | 7 (53.8%) | 3(23.1%) |

| Bwari | 358 | 7 | 3(42.9%) | 4(57.1%) | 0(%) | 5 | 3(60.0%) | 1(20.0%) | 1(20.0%) |

| Gwagwalada | 459 | 30 | 6 (20.0%) | 16(53.3%) | 8(26.7%) | 33 | 6(26.1%) | 14(60.9%) | 3(13.0%) |

| Grand Total | 1370 | 78 | 26 (33.3%) | 37 (47.4%) | 15(19.2%) | 66 | 20(30.3%) | 29 (43.9) | 7 (10.6) |

| P > 0.05 | |||||||||

| Source of water | No. examined | No. positive (%) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Well/Rain | 287 | 0 (0%) | <0.0001 |

| Borehole | 300 | 0 (0%) | |

| Tap water | 238 | 0 (0%) | |

| River | 324 | 203 (62.7%) | |

| Well/Rain/River | 93 | 66 (71%) | |

| Well/Rain/borehole/Rivers | 78 | 63 (80.8%) | |

| Borehole and Rivers | 50 | 45(90%) | |

| Total | 1370 | 377 (27.5%) |

| Activities in the river | Total number examined | No. infected (%) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fetching | 46 | 31 (67.4%) | <0.0001 |

| Swimming | 159 | 132 (83%) | |

| Bathing | 94 | 58(61.7%) | |

| Washing | 141 | 90 (63.8%) | |

| Crossing water | 83 | 46 (55.4%) | |

| Fishing | 22 | 20(90.9%) | |

| Total | 545 | 377(69.2%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).