Submitted:

22 January 2025

Posted:

22 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sistanizad, M.; Kouchek, M.; Miri, M.; Salarian, S.; Shojaei, S.; Moeini Vasegh, F.; Seifi Kafshgari, H.; Qobadighadikolaei, R. High Dose Vitamin D Improves Total Serum Antioxidant Capacity and ICU Outcome in Critically Ill Patients - A Randomized, Double-Blind Clinical Trial. Eur. J. Integr. Med. 2021, 42, 101271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Institute of Medicine; Food and Nutrition Board; Committee to Review Dietary Reference Intakes for Vitamin D and Calcium Dietary Reference Intakes for Calcium and Vitamin D. Del Valle, H.B., Yaktine, A.L., Taylor, C.L., Ross, A.C., Eds.; National Academies Press: Washington, D.C., DC, 2011; ISBN 9780309163941.

- Sistanizad, M.; Salarian, S.; Kouchek, M.; Shojaei, S.; Miri, M.; Masbough, F. Effect of Calcitriol Supplementation on Infectious Biomarkers in Patients with Positive Systemic Inflammatory Response: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Ann. Med. Surg. (Lond.) 2024, 86, 875–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhattacharyya, A.; Subramaniam, R.; Baidya, D.K.; Aggarwal, P.; Wig, N. Effect of Early Administration of Vitamin D on Clinical Outcome in Critically Ill Sepsis Patients: A Randomized Placebo-Controlled Trial. Indian J. Crit. Care Med. 2021, 25, 1147–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bychinin, M.V.; Klypa, T.V.; Mandel, I.A.; Yusubalieva, G.M.; Baklaushev, V.P.; Kolyshkina, N.A.; Troitsky, A.V. Effect of Vitamin D3 Supplementation on Cellular Immunity and Inflammatory Markers in COVID-19 Patients Admitted to the ICU. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 18604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thampi, S.J.; Basheer, A.; Thomas, K. Calcitriol in Sepsis-A Single-Centre Randomised Control Trial. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 3823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Kumar, A.; Choudhary, A.; Sharma, S.; Khurana, L.; Sharma, N.; Kumar, V.; Bisht, A. Neuroprotective Role of Oral Vitamin D Supplementation on Consciousness and Inflammatory Biomarkers in Determining Severity Outcome in Acute Traumatic Brain Injury Patients: A Double-Blind Randomized Clinical Trial. Clin. Drug Investig. 2020, 40, 327–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute PETAL Clinical Trials Network; Ginde, A. A.; Brower, R.G.; Caterino, J.M.; Finck, L.; Banner-Goodspeed, V.M.; Grissom, C.K.; Hayden, D.; Hough, C.L.; Hyzy, R.C.; et al. Early High-Dose Vitamin D3 for Critically Ill, Vitamin D-Deficient Patients. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 381, 2529–2540. [CrossRef]

- Moromizato, T.; Litonjua, A.A.; Braun, A.B.; Gibbons, F.K.; Giovannucci, E.; Christopher, K.B. Association of Low Serum 25-Hydroxyvitamin D Levels and Sepsis in the Critically Ill. Crit. Care Med. 2014, 42, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashoor, T.M.; Abd Elazim, A.E.H.; Mustafa, Z.A.E.; Anwar, M.A.; Gad, I.A.; Mamdouh Esmat, I. Outcomes of High-Dose versus Low-Dose Vitamin D on Prognosis of Sepsis Requiring Mechanical Ventilation: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Intensive Care Med. 2024, 39, 1012–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

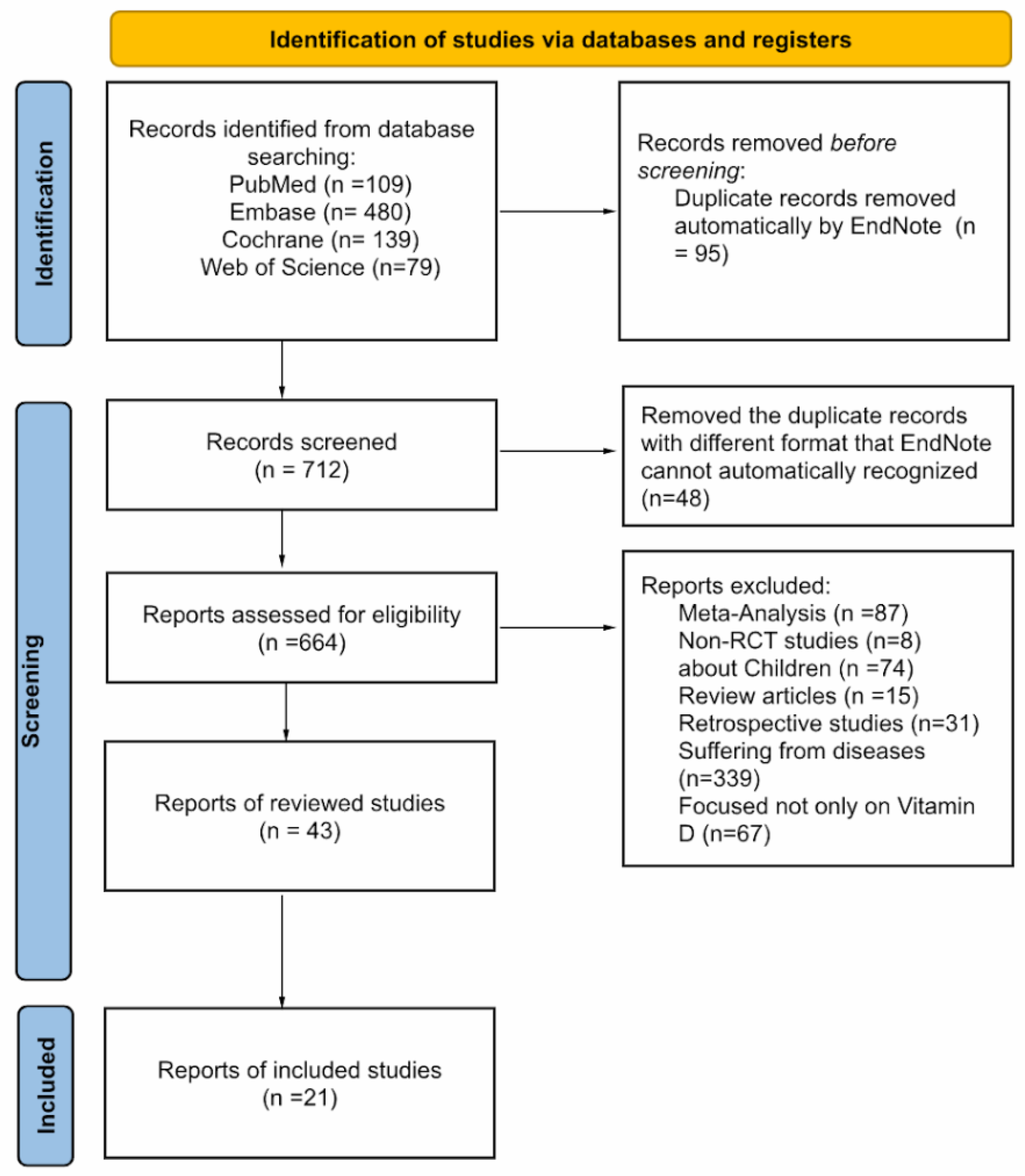

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Rastogi, A.; Puri, G.D.; Ganesh, V.; Naik, N.B.; Kajal, K.; Kahlon, S.; Soni, S.L.; Kaloria, N.; Saini, K.; et al. Therapeutic High-Dose Vitamin D for Vitamin D-Deficient Severe COVID-19 Disease: Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Study (SHADE-S). J. Public Health (Oxf.) 2024, 46, 256–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masbough, F.; Kouchek, M.; Koosha, M.; Salarian, S.; Miri, M.; Raoufi, M.; Taherpour, N.; Amniati, S.; Sistanizad, M. Investigating the Effect of High-Dose Vitamin D3 Administration on Inflammatory Biomarkers in Patients with Moderate to Severe Traumatic Brain Injury: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Iran. J. Med. Sci. 2024, 49, 643–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamanian, M.; Javadfar, Z.; Salimi, Y.; Rahimi, M.A.; Rabieenia, E.; Rahimi, A. Effect of High-Dose Vitamin D on Mortality and Hospital Length of Stay in ICU Patients with COVID-19: A Randomized Clinical Trial. J. Kermanshah Univ. Med. Sci. 2024, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, A.-Y.; Yeh, Y.-C.; Cheng, K.-H.; Han, Y.-Y.; Chiu, C.-T.; Chang, C.-C.; Wang, I.-T.; Chao, A. Efficacy and Safety of Enteral Supplementation with High-Dose Vitamin D in Critically Ill Patients with Vitamin D Deficiency. J. Formos. Med. Assoc. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Domazet Bugarin, J.; Dosenovic, S.; Ilic, D.; Delic, N.; Saric, I.; Ugrina, I.; Stojanovic Stipic, S.; Duplancic, B.; Saric, L. Vitamin D Supplementation and Clinical Outcomes in Severe COVID-19 Patients-Randomized Controlled Trial. Nutrients 2023, 15, 1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, J.H.; Ginde, A.A.; Brown, S.M.; Baughman, A.; Collar, E.M.; Ely, E.W.; Gong, M.N.; Hope, A.A.; Hou, P.C.; Hough, C.L.; et al. Effect of Early High-Dose Vitamin D3 Repletion on Cognitive Outcomes in Critically Ill Adults. Chest 2021, 160, 909–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naguib, S.N.; Sabry, N.A.; Farid, S.F.; Alansary, A.M. Short-Term Effects of Alfacalcidol on Hospital Length of Stay in Patients Undergoing Valve Replacement Surgery: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Clin. Ther. 2021, 43, e1–e18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hajimohammadebrahim-Ketabforoush, M.; Shahmohammadi, M.; Keikhaee, M.; Eslamian, G.; Vahdat Shariatpanahi, Z. Single High-Dose Vitamin D3 Injection and Clinical Outcomes in Brain Tumor Resection: A Randomized, Controlled Clinical Trial. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN 2021, 41, 153–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingels, C.; Vanhorebeek, I.; Van Cromphaut, S.; Wouters, P.J.; Derese, I.; Dehouwer, A.; Møller, H.J.; Hansen, T.K.; Billen, J.; Mathieu, C.; et al. Effect of Intravenous 25OHD Supplementation on Bone Turnover and Inflammation in Prolonged Critically Ill Patients. Horm. Metab. Res. 2020, 52, 168–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Padhy, S.S.; Malviya, D.; Harjai, M.; Tripathi, M.; Das, P.K.; Rastogi, S. A Study of Vitamin D Level in Critically Ill Patients and Effect of Supplementation on Clinical Outcome. Anesth. Essays Res. 2020, 14, 474–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasanloei, M.A.V.; Rahimlou, M.; Eivazloo, A.; Sane, S.; Ayremlou, P.; Hashemi, R. Effect of Oral versus Intramuscular Vitamin D Replacement on Oxidative Stress and Outcomes in Traumatic Mechanical Ventilated Patients Admitted to Intensive Care Unit. Nutr. Clin. Pract. 2020, 35, 548–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karsy, M.; Guan, J.; Eli, I.; Brock, A.A.; Menacho, S.T.; Park, M.S. The Effect of Supplementation of Vitamin D in Neurocritical Care Patients: RandomizEd Clinical TrIal oF hYpovitaminosis D (RECTIFY). J. Neurosurg. 2020, 133, 1103–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miri, M.; Kouchek, M.; Rahat Dahmardeh, A.; Sistanizad, M. Effect of High-Dose Vitamin D on Duration of Mechanical Ventilation in ICU Patients. Iran. J. Pharm. Res. 2019, 18, 1067–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Randolph, C.; Tierney, M.C.; Mohr, E.; Chase, T.N. The Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status (RBANS): Preliminary Clinical Validity. J. Clin. Exp. Neuropsychol. 1998, 20, 310–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shunk, A.W.; Davis, A.S.; Dean, R.S. TEST REVIEW: Dean C. Delis, Edith Kaplan & Joel H. Kramer, Delis Kaplan Executive Function System (D-KEFS), the Psychological Corporation, San Antonio, TX, 2001. $415.00 (complete Kit). Appl. Neuropsychol. 2006, 13, 275–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbas, E.M.; Gungor, A.; Ozcicek, A.; Akbas, N.; Askin, S.; Polat, M. Vitamin D and Inflammation: Evaluation with Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio and Platelet-to-Lymphocyte Ratio. Arch. Med. Sci. 2016, 12, 721–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martucci, G.; McNally, D.; Parekh, D.; Zajic, P.; Tuzzolino, F.; Arcadipane, A.; Christopher, K.B.; Dobnig, H.; Amrein, K. Trying to Identify Who May Benefit Most from Future Vitamin D Intervention Trials: A Post Hoc Analysis from the VITDAL-ICU Study Excluding the Early Deaths. Crit. Care 2019, 23, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amrein, K. The VITDALIZE Study: Effect of High-Dose Vitamin D3 on 28-Day Mortality in Adult Critically Ill Patients (VITDALIZE) Available online:. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT03188796 (accessed on 19 January 2025).

- Joshi, D. ; Jacqueline R Center; Eisman, J. A. Vitamin D Deficiency in Adults. Aust. Prescr. 2010, 33, 103–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lung, B.E.; Mowery, M.L.; Komatsu, D.E.E. Calcitriol. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island (FL), 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Iglar, P.J.; Hogan, K.J. Vitamin D Status and Surgical Outcomes: A Systematic Review. Patient Saf. Surg. 2015, 9, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amrein, K.; Papinutti, A.; Mathew, E.; Vila, G.; Parekh, D. Vitamin D and Critical Illness: What Endocrinology Can Learn from Intensive Care and Vice Versa. Endocr. Connect. 2018, 7, R304–R315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomes, T.L.; Fernandes, R.C.; Vieira, L.L.; Schincaglia, R.M.; Mota, J.F.; Nóbrega, M.S.; Pichard, C.; Pimentel, G.D. Low Vitamin D at ICU Admission Is Associated with Cancer, Infections, Acute Respiratory Insufficiency, and Liver Failure. Nutrition 2019, 60, 235–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quraishi, S.A.; Camargo, C.A. , Jr Vitamin D in Acute Stress and Critical Illness. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care 2012, 15, 625–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krishnan, A.; Ochola, J.; Mundy, J.; Jones, M.; Kruger, P.; Duncan, E.; Venkatesh, B. Acute Fluid Shifts Influence the Assessment of Serum Vitamin D Status in Critically Ill Patients. Crit. Care 2010, 14, R216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramasamy, I. Vitamin D Metabolism and Guidelines for Vitamin D Supplementation. Clin. Biochem. Rev. 2020, 41, 103–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Argano, C.; Mallaci Bocchio, R.; Natoli, G.; Scibetta, S.; Lo Monaco, M.; Corrao, S. Protective Effect of Vitamin D Supplementation on COVID-19-Related Intensive Care Hospitalization and Mortality: Definitive Evidence from Meta-Analysis and Trial Sequential Analysis. Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 2023, 16, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study | Year | Baseline vit D level (ng/mL) | Sample Size | Patient population | Vit D Replacement Dose | Duration | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ashoor et al [10] | 2024 | <20 | 80 | Sepsis on mechanical ventilation | HD: enteral 50,000IU/d vs LD: enteral 5,000IU/d | 5 days | Significant difference in procalcitonin, LL-37 reduction, improved SOFA and hospital LOS |

| Singh et al [12] | 2024 | 12 vs 13 | 90 | Covid-19 | Enteral 600,000IU | Once | Significantly improved SOFA score at Day 7 and 28 day mortality |

| Masbough et al [13] | 2024 | 15.95 vs 17.84 | 35 | Traumatic brain injury | IM 300,000IU | Once | Statistically significant increase in GCS scores, reduction in inflammatory markers; improvement in the GOS-E score; no difference in 28 day mortality, ICU LOS, MV needs |

| Thampi et al [6] | 2024 | Not reported | 152 | Sepsis | Calcitriol IM 300,000IU | Once | No significant difference in APACHE II scores, 28-day mortality, MV days, ICU LOS and hospital-acquired infections |

| Sistanizad et al [3] | 2024 | 11.37 vs 13.96 | 28 | Sepsis | Calcitriol IV 1 mcg/day | 3 days | No significant different in procalcitonin level, ICU LOS and 28-day mortality |

| Zamanian et al [14] | 2024 | 23.06 vs 25.68 | 61 | COVID-19 | IM 300,000IU | Once | No significant difference in mortality or hospital LOS |

| Wang et al [15] | 2024 | <20 | 61 | Vitamin D-deficient | Enteral 569,600IU | Once divided by 8 bottles | Less than half of the treatment group who achieved vit D level>30 ng/ml. They had significantly lower 30-day mortality than those who did not |

| Domazet Bugarin et al [16] | 2023 | 25.3 vs 27.3 | 155 | Covid-19 | Enteral 10,000IU vs placebo | Once | No statistically significant in MV days, secondary outcomes |

| Bychinin et al [5] | 2022 | 9.6 vs 11 | 110 | COVID-19 | PO 60,000IU weekly then 5,000IU/daily | During hospital stay | Significantly increased NK and NK T cell counts. No difference in mortality; need for MV or incidence of nosocomial infection |

| Sistanizad et al [1] | 2021 | <20 | 36 | ICU ventilated | IM 300,000IU vs placebo | Once | No statistically significant results identified due to small sample size |

| Bhattacharyya et al [4] | 2021 | 12.05 vs 15.47 | 126 | Sepsis | Enteral 540,000IU vs placebo | Once | No statistically difference in ICU LOS, hospital LOS, MV duration/requirements, or 90-day mortality |

| Han et al [17] | 2021 | 15.2 vs 13.1 | 95 | Vitamin D-deficient | Enteral 540,000IU | Once | No significant difference in long-term global cognition or executive function |

| Naguib et al [18] | 2021 | 21 vs. 19.1 | 86 | Elective mechanical valve replacement | Alfacalcidol 2 μg/day PO | Starting 2 days before surgery until the end of hospital stay | Statistically significant reduction in ICU LOS, postoperative infection rate. No significantly difference in hospital mortality |

| Sharma et al [7] | 2020 | 18.30 vs 15.15 | 35 | Traumatic brain injury | Enteral 120,000IU vs placebo | Once | Significant improvement in GCS score, MV duration and IL-6, TNF-ɑ |

| Hajimohammadebrahim-Ketabforoush et al [19] | 2020 | <20 | 60 | Craniotomy for brain tumor resection | IM 300,000IU | Once | Significantly reduction in ICU LOS and hospital LOS |

| Ingels et al [20] | 2020 | 6.8 vs. 9.2 | 24 | Prolonged ICU stay(>10 days) | 200μg loading dose once then 15μg/day | Loading dose then 10 days | No difference in SOFA score or MV duration |

| Padhy et al [21] | 2020 | ≤20 | 60 | Vitamin D-deficient, sepsis | G1: enteral 60,000IU once/wk; G2: 60,000IU twice/wk | During hospital stay | No difference was found in ICU LOS, duration of MV, and 28 day ICU mortality. Patients in group 2 required less inotropic support p=0.037 |

| Hasanloei et al [22] | 2020 | 10 - 30 | 72 | Ventilated, traumatic injury | G1: PO 50,000IU /day; G2: IM 300,000IU vs placebo | G1: 6 days; G2: once | Significant improvement in IL6, ESR, CRP, SOFA score, duration of MV, ICU LOS |

| Karsy et al [23] | 2020 | 14.6 vs 13.9 | 267 | Neurocritical care, vitamin D-deficient | PO 540,000IU vs placebo | Once | No statistically difference in hospital LOS or ICU LOS |

| Miri et al [24] | 2019 | 8.43 vs. 11.35 | 40 | ICU ventilated | IM 300,000IU vs placebo | Once | Significant reduction in 28-day mortality |

| PETAL group [8] | 2019 | 11.2 vs 11.0 | 1078 | Vitamin D- deficient | Enteral 540,000IU vs placebo | Once | No statistically difference in 90-day mortality and other clinical outcomes |

| Year | Author | Clinical results | Biomarkers | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICU LOS | Hospital LOS | SOFA score | MV duration | MV needs | 90-day mortality | 28-day mortality | 30-day mortality | GCS | Less inotropic support | |||

| 2024 | Ashoor et al [10] | HD | HD | HD: pct, IL-37 | ||||||||

| 2024 | Singh et al [12] | |||||||||||

| 2024 | Masbough et al [13] | IL-1b, IL-6 | ||||||||||

| 2024 | Thampi et al [6] | |||||||||||

| 2024 | Sistanizad et al [3] | pct | ||||||||||

| 2024 | Zamanian et al [14] | |||||||||||

| 2023 | Domazet Bugarin et al [16] | |||||||||||

| 2022 | Bychinin et al [5] | All-cause | NK, NKT, CRP, pct | |||||||||

| 2021 | Sistanizad et al [1] | |||||||||||

| 2021 | Bhattacharyya et al [4] | |||||||||||

| 2021 | Han et al [17] | BRANS score | ||||||||||

| 2021 | Naguib et al [18] | |||||||||||

| 2020 | Sharma et al [7] | IL-6, TNF-α | ||||||||||

| 2020 | Hajimohammadebrahim-Ketabforoush et al [19] | |||||||||||

| 2020 | Ingels et al [20] | CRP, WBC, IL-37, sCD163 | ||||||||||

| 2020 | Wang et al [15] | |||||||||||

| 2020 | Padhy et al [21] | |||||||||||

| 2020 | Hasanloei et al [22] | IL-6, ESR, CRP | ||||||||||

| 2020 | Karsy et al [23] | |||||||||||

| 2019 | Miri et al [24] | |||||||||||

| 2019 | PETAL group [8] | |||||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).