Submitted:

20 January 2025

Posted:

22 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. MPOWER Scores

2.2. Lip and Oral Cavity Cancer Rates

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

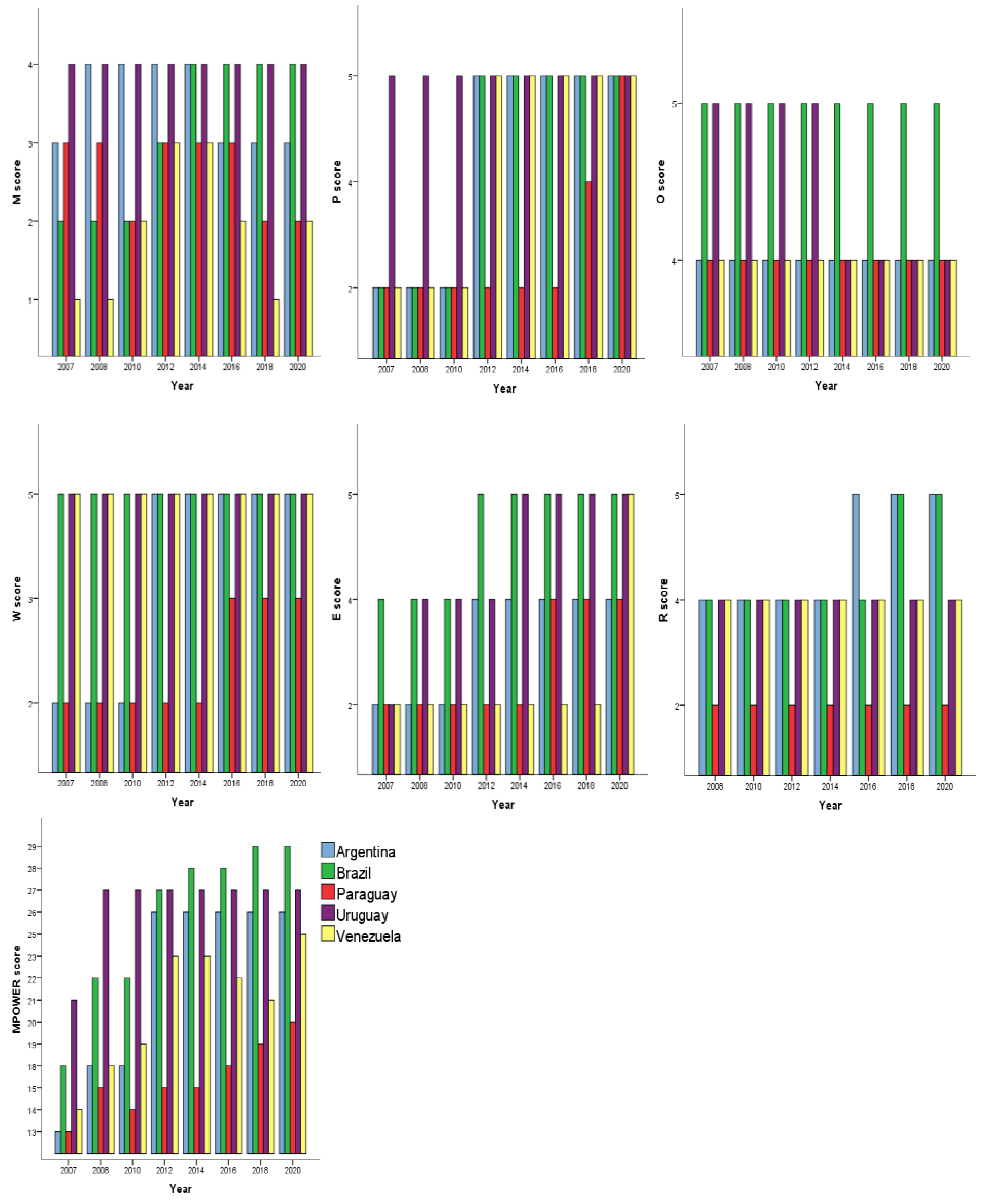

3.1. MPOWER Scores

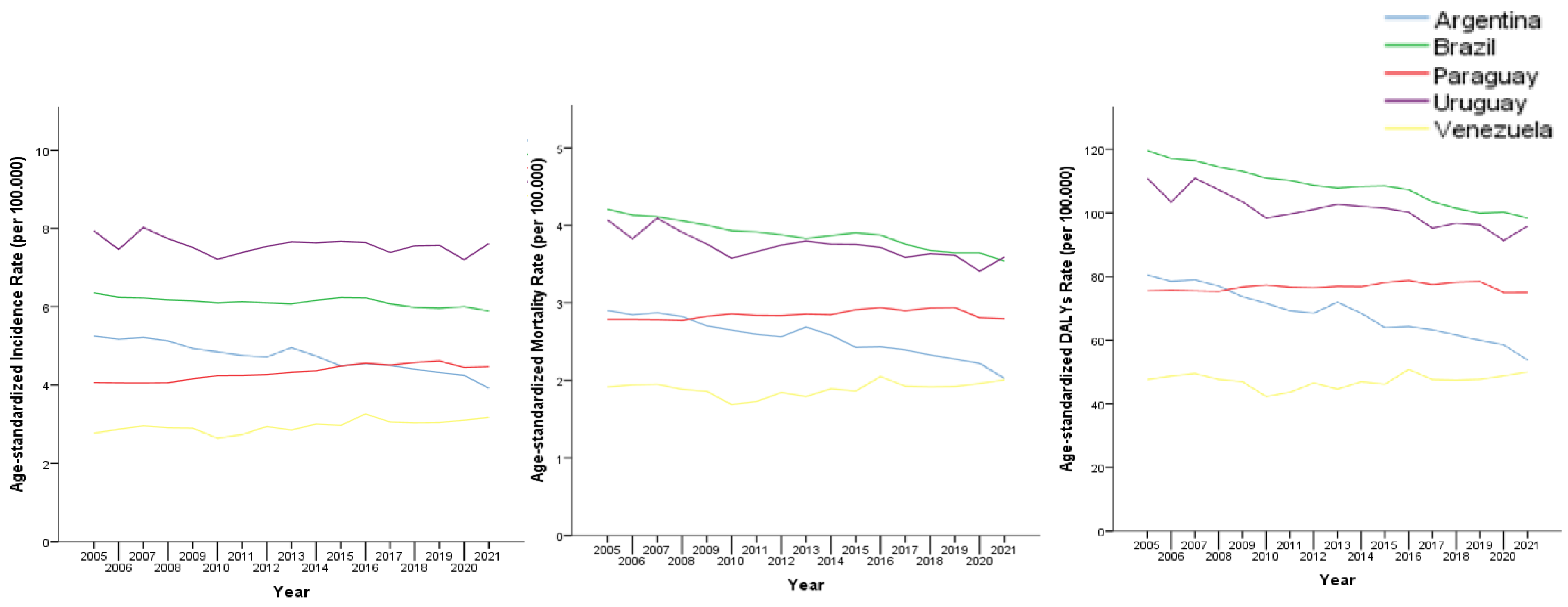

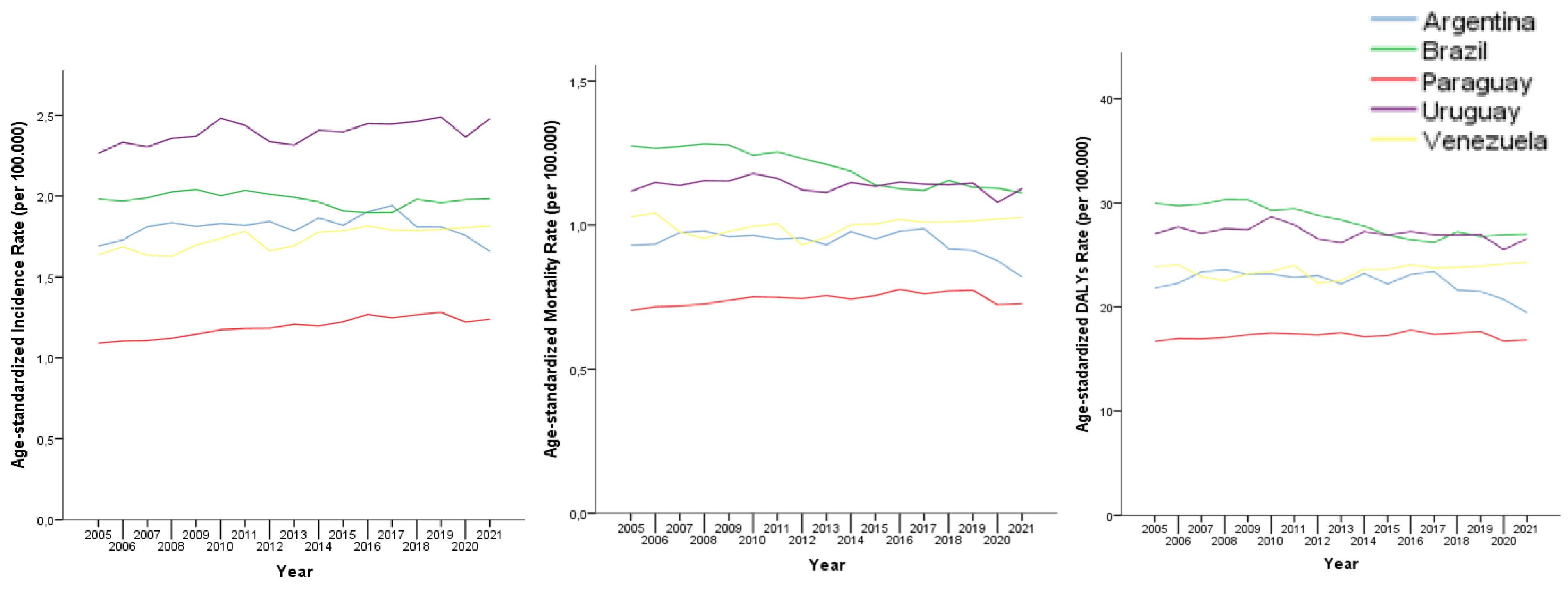

3.2. LOC Trends

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- GBD 2019 Lip, Oral, and Pharyngeal Cancer Collaborators. The Global, Regional, and National Burden of Adult Lip, Oral, and Pharyngeal Cancer in 204 Countries and Territories: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. JAMA Oncol. 2023, 9, 1401–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GBD 2019 Cancer Collaboration. Cancer Incidence, Mortality, Years of Life Lost, Years Lived With Disability, and Disability-Adjusted Life Years for 29 Cancer Groups From 2010 to 2019 A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. JAMA Oncol. 2022, 8, 420–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mello, F.W.; Melo, G.; Pasetto, J.J.; Silva, C.A.B.; Warnakulasuriya, S.; Rivero, E.R.C. The synergistic effect of tobacco and alcohol consumption on oral squamous cell carcinoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Oral. Invest. 2019, 23, 2849–2859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warnakulasuriya, S. Global epidemiology of oral and oropharyngeal cancer. Oral oncol. 2009, 45, 309–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jethwa, A.R.; Khariwala, S.S. Tobacco-related carcinogenesis in head and neck cancer. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2017, 36, 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2003. Available online: https://fctc.who.int/resources/publications (accessed on 14 December 2024).

- WHO report on the global tobacco epidemic, 2023: protect people from tobacco smoke. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240077164 (accessed on 14 December 2024).

- GBD 2019 Cancer Risk Factors Collaborators. The global burden of cancer attributable to risk factors, 2010–2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet 2022, 400, 563–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nocini, R.; Lippi, G.; Mattiuzzi, C. The worldwide burden of smoking-related oral cancer deaths. Clin Exp Dent Res. 2020, 6, 161–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto Nacional de Câncer (INCA). Relatório Evolutivo da Comissão Intergovernamental para o Controle do Tabaco. Brasil: INCA, 2012. Available online: https://ninho.inca.gov.br/jspui/ (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- Herrera-Serna, B.Y.; Lara-Carrillo, E.; Toral-Rizo, V.H.; Amaral, R.C. Efecto de las Políticas de Control de Factores de Riesgo Sobre la Mortalidad por Cáncer Oral en América Latina. Rev Esp Salud Pública. 2019, 93, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Herrera-Serna, B.Y.; Lara-Carrillo, E.; Toral-Rizo, V.H.; Amaral, R.C.; Aguilera-Eguía, R.A. Relationship between the Human Development Index and its Components with Oral Cancer in Latin America. J Epidemiol Glob Hea. 2019, 9, 223–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. The Global Health Observatory. Available online: https://www.who.int/data/gho (accessed on 31 November 2024).

- IHME. GHDx: GBD Results Tool. Available online: http://ghdx.healthdata.org/gbd-results-tool (accessed on 31 November 2024).

- Antunes, J.L.; Waldman, E.A. Trends and spatial distribution of deaths of children aged 12- 60 months in São Paulo, Brazil, 1980–1998. Bull World Health Organ. 2002, 80, 391–398. [Google Scholar]

- Flor, L.S.; Reitsma, M.B.; Gupta, V.; Ng, M.; Gakidou, E. The effects of tobacco control policies on global smoking prevalence. Nat Med. 2021, 27, 239–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conway, D.I.; Petticrew, M.; Marlborough, H.; Berthiller, J.; Hashibe, M.; Macpherson, L.M.D. Socioeconomic inequalities and oral cancer risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis of case-control studies. Int J Cancer. 2008, 122, 2811–2819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, S.L.; Togawa, K.; Gilmour, S.; Leon, M.E.; Soerjomataram, I.; Katanoda, K. Projecting the impact of implementation of WHO MPOWER measures on smoking prevalence and mortality in Japan. Tob Control. 2022, 33, 295–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramadan, M.; Alhusseini, N.; Samhan, L.; Samhan, S.; Abbad, T. Tobacco control policies implementation and future lung cancer incidence in Saudi Arabia. A population-based study. Prev. Med. Rep. 2023, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera-Serna, B.Y.; Betancourt, J.A.O.; Soto, O.P.L.; Amaral, R.C.; Correa, M.P.C. Trends of incidence, mortality, and disability-adjusted life years of oral cancer in Latin America. Rev Bras Epidemiol. 2022, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sóñora, G.; Reynales-Shigematsu, L.M.; Barnoya, J.; Llorente, B.; Szklo, A.S.; Thrasher, J.F. Achievements, Challenges, Priorities and Needs to Address the Current Tobacco Epidemic in Latin-america. Tob Control. 2022, 31, 138–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GBD Study 2019 Collaborators. Spatial, temporal, and demographic patterns in prevalence of smoking tobacco use and attributable disease burden in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet. 2021, 397, 2337–2360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tam, J.; Jaffri, M.A.; Mok, Y.; Jeon, J.; Szklo, A.S.; Souza, M.C.; Holford, T.R.; Levy, D.T.; Cao, P.; Sánchez-Romero, L.M.; Meza, R. Patterns of Birth Cohort‒Specific Smoking Histories in Brazil. Am J Prev Med. 2023, 64, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freire, A.R.; Freire, D.E.W.G.; Araújo, E.C.F.d.; de Lucena, E.H.G.; Cavalcanti, Y.W. Influence of Public Oral Health Services and Socioeconomic Indicators on the Frequency of Hospitalization and Deaths due to Oral Cancer in Brazil, between 2002–2017. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2021, 18, 238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freire, A.R.; Freire, D.E.W.G.; Araújo, E.C.F.; Carrer, F.C.A.; Pucca Júnior, G.A.; Sousa, S.A.; Lucena, E.H.G.; Cavalcanti, Y.W. Socioeconomic indicators and economic investments influence oral cancer mortality in Latin America. BMC Public Health. 2021, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abascal, W.; Esteves, E.; Goja, B.; Mora, F.G.; Lorenzo, A.; Sica, A.; Triunfo, P.; Harris, J.E. Tobacco control campaign in Uruguay: a population-based trend analysis. Lancet. 2012, 380, 1575–1582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salgado, M.V.; Mok, Y.; Jeon, J.; Jaffri, M.; Tam, J.; Holford, T.R.; Sánchez-Romero, L.M.; Meza, R.; Mejia, R. Smoking patterns by birth cohort in Argentina: an age-period cohort population-based modeling study. Lancet Reg Health Am. 2024, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. Protocol to Eliminate Illicit Trade in Tobacco Products. Available online: https://fctc.who.int/news-and-resources/publications (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- Ramos, A. Illegal trade in tobacco in MERCOSUR countries. Trends Organ Crim. 2009, 12, 267–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masi, F.; Rodriguez-Iglesias, G.; Drope, J. Regional implications of the tobacco value chain in Paraguay. Tob Control. 2022, 31, 140–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GBD Study 2021 Collaborators. Global incidence, prevalence, years lived with disability (YLDs), disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs), and healthy life expectancy (HALE) for 371 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories and 811 subnational locations, 1990–2021: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet. 2023, 403, 2133–2161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conway, D.I.; Purkayastha, M.; Chestnutt, I.G. The changing epidemiology of oral cancer: definitions, trends, and risk factors. Br Dent J. 2018, 225, 867–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Countries | M | P | O | W | E | R | MPOWER |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Argentina | 3.50 [3;4] | 5.0 [2;5] | 4.0 [4;4] | 5.0 [2;5] | 4.0 [2;4] | 4.5 [4;5] | 26.0 [18;26] |

| Brazil | 3.50 [2;4] | 5.0 [2;5] | 5.0 [5;5] | 5.0 [5;5] | 5.0 [4;5] | 4.0 [4;5] | 27.5 [22;28.3] |

| Paraguay | 3.0 [2;3] | 2 [2;2.5] | 4.0 [4;4] | 2.0 [2;3] | 2 [2;5] | 2.0 [2;2] | 15.0 [14.8;19;3] |

| Uruguay | 4.0 [4;4] | 5.0 [5;5] | 4.5 [4;5] | 5.0 [5;5] | 4.5 [4;5] | 4.0 [4;4] | 27.0 [27;27] |

| Venezuela | 2.0 [1;2.25] | 5.0 [2;5] | 4.0 [4;4] | 5.0 [5;5] | 2 [2;2] | 4.0 [4;4] | 21.5 [8.8;23] |

| Country | Sex | Incidence trend (APC [95%CI]) |

Mortality trend (APC [95% CI]) |

DALYs trend (APC [95%CI]) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Argentina | Male | Decreasing (-1.55[1.87;-1.24]) | Decreasing (-1.98[-2.39;-1.56]) | Decreasing (-2.24[-2.56;-1.92]) |

| Female | Stationary (-0.02[-0.76;0.74]) | Stationary (-0.65[-1.50;0.21]) | Stationary (-0.63[-1.40;0.14] | |

| Brazil | Male | Decreasing (-0.37[-0.59;-0.15]) | Decreasing (-0.98[-1.20;-0.76]) | Decreasing (-1.16[-1.34;-0.98]) |

| Female | Stationary (-0.10[-0.46;0.27]) | Decreasing (-0.95[-1.27;-0.63]) | Decreasing (-0.79[-1.22;-0.36]) | |

| Paraguay | Male | Increasing (0.74[0.39;1.09]) | Stationary (0.14[-0.18;0.46]) | Stationary (0.05[-0.22;0.33]) |

| Female | Increasing (0.91[0.58;1.24]) | Stationary (0.27[-0.16;0.71]) | Stationary (0.08[-0.18;0.34]) | |

| Uruguay | Male | Stationary (-0.21[-0.50;0.07]) | Decreasing (-0.72[-1.06;-0.38]) | Decreasing -0.89[-1.18;-0.59]) |

| Female | Increasing (0.40[0.14;0.66]) | Stationary (-0.13[-0.34;0.09]) | Decreasing (-0.27[-0.53;-0.02]) | |

| Venezuela | Male | Increasing (0.77[0.26;1.27]) | Stationary (0.31[-0.43;1.07]) | Stationary (0.24[-0.47;0.96]) |

| Female | Increasing (0.67[0.42;0.93]) | Stationary (0.12[-0.32;0.56]) | Stationary (0.21[-0.12;0.54]) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).