Submitted:

20 January 2025

Posted:

21 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

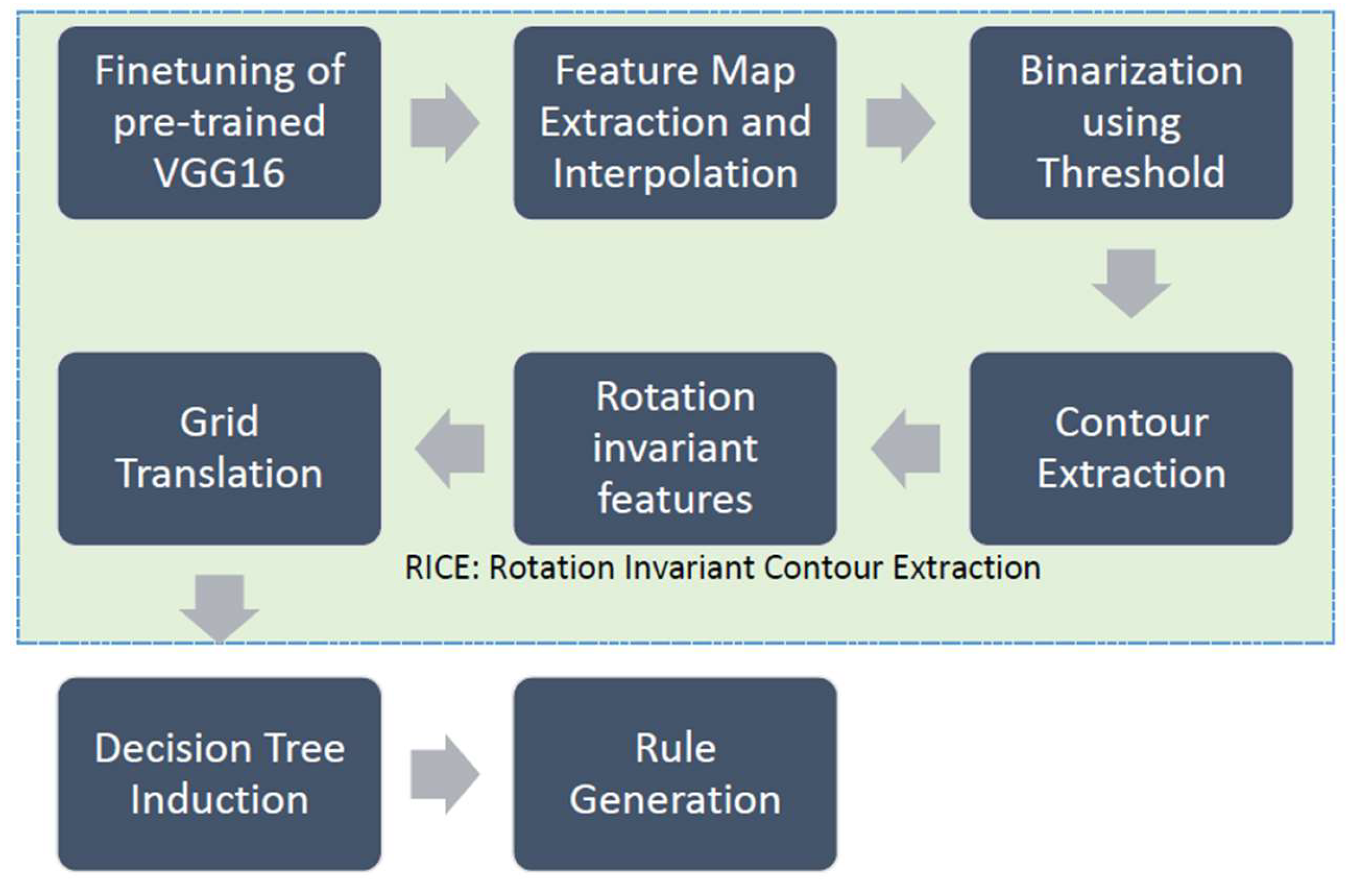

2.1. Overview of methodology

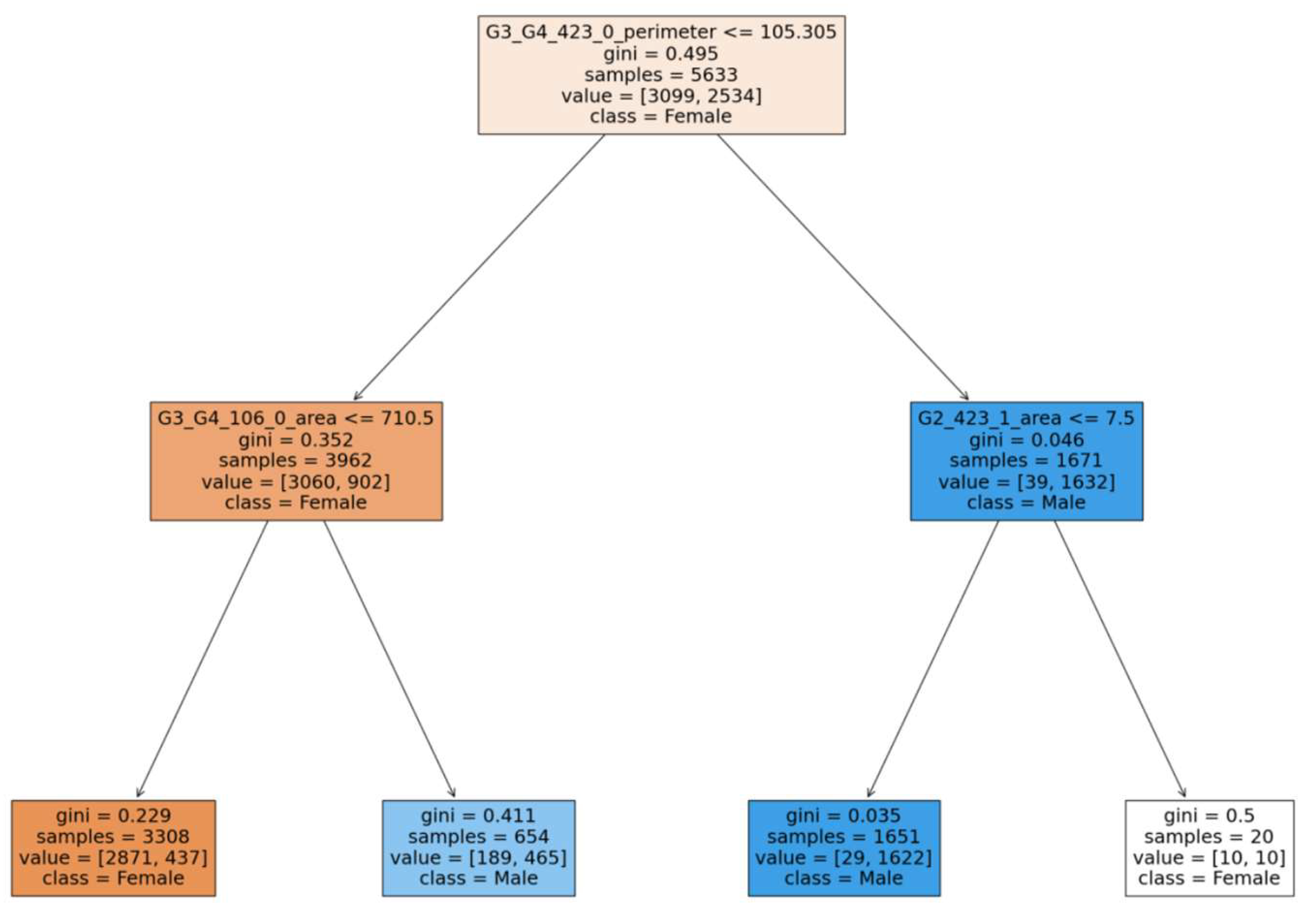

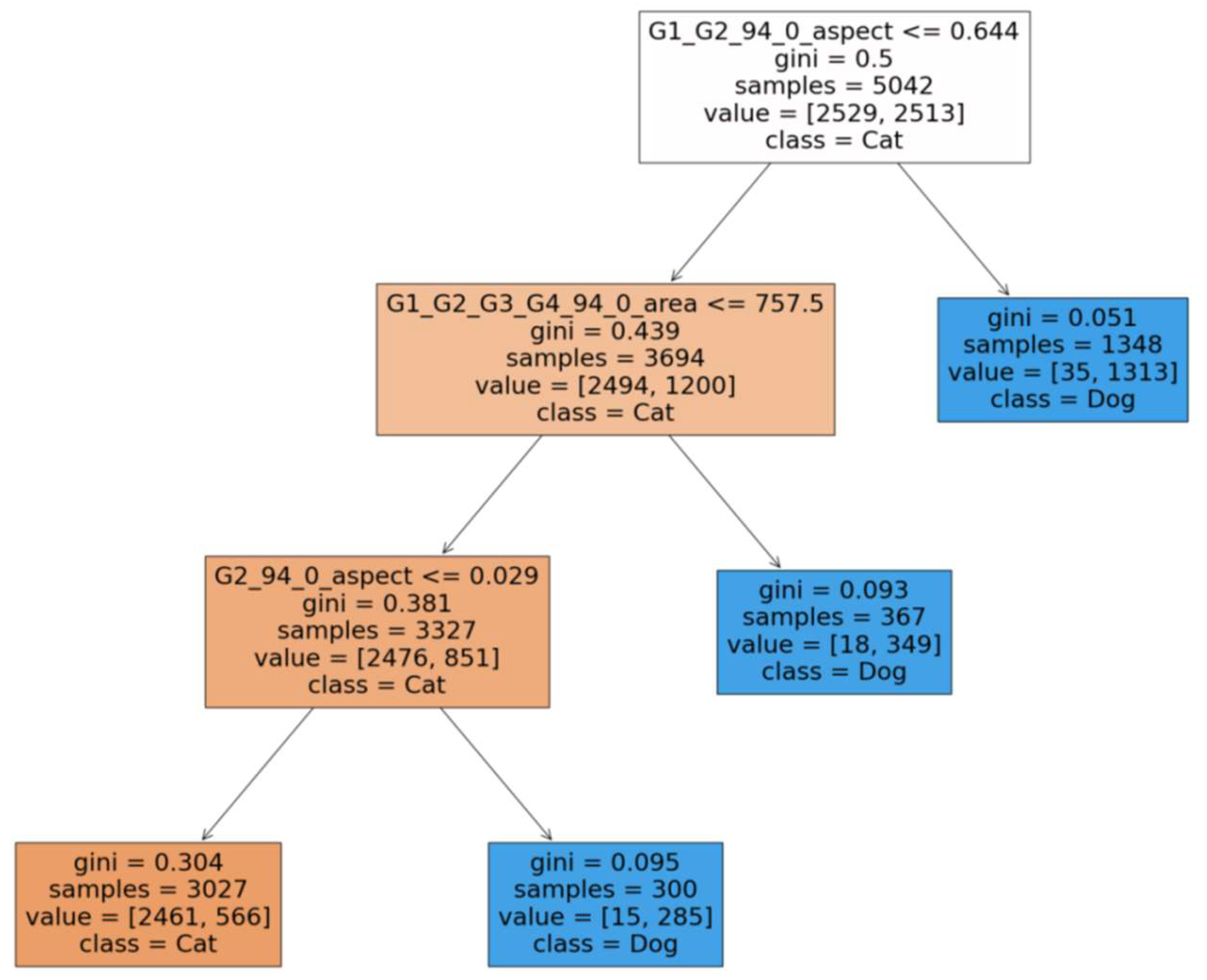

2.2. Feature extraction and rule generation

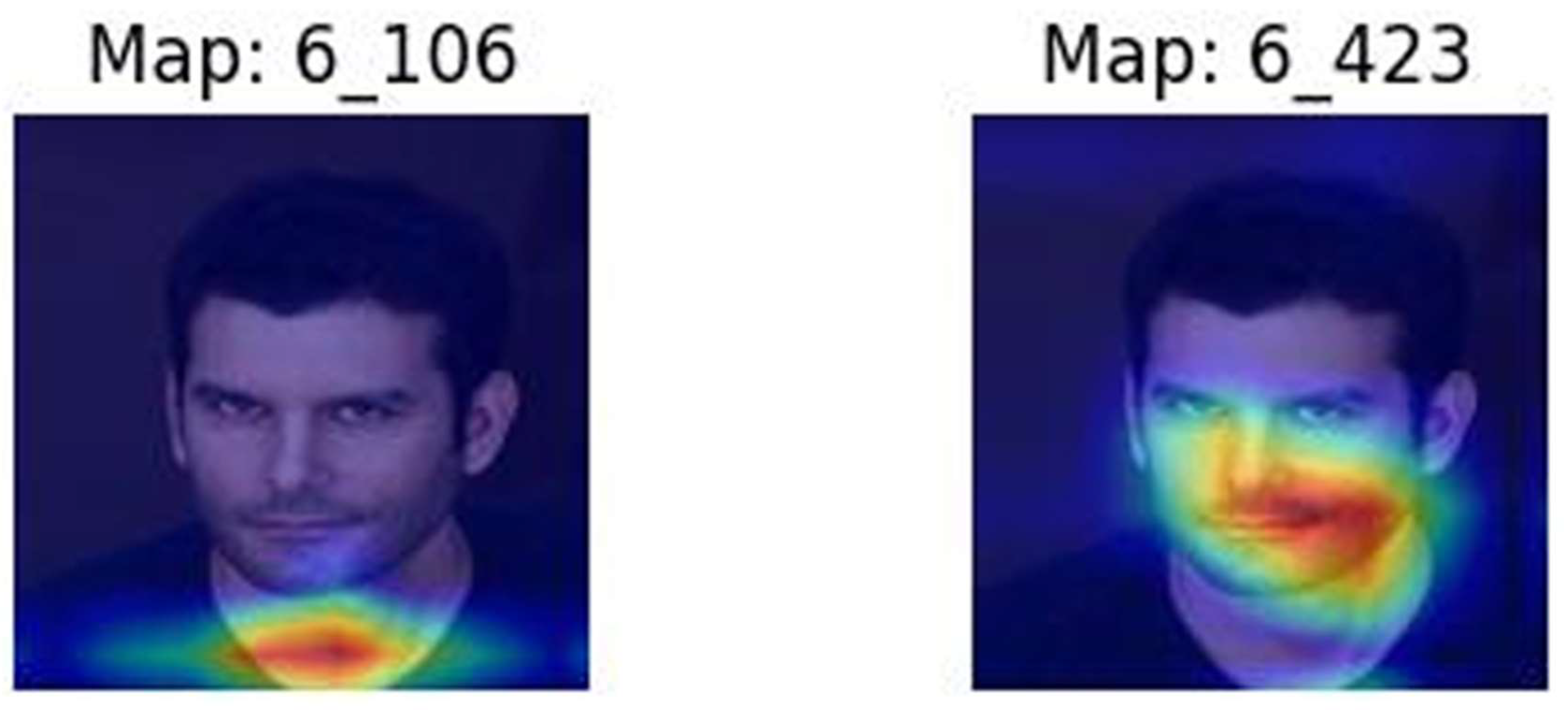

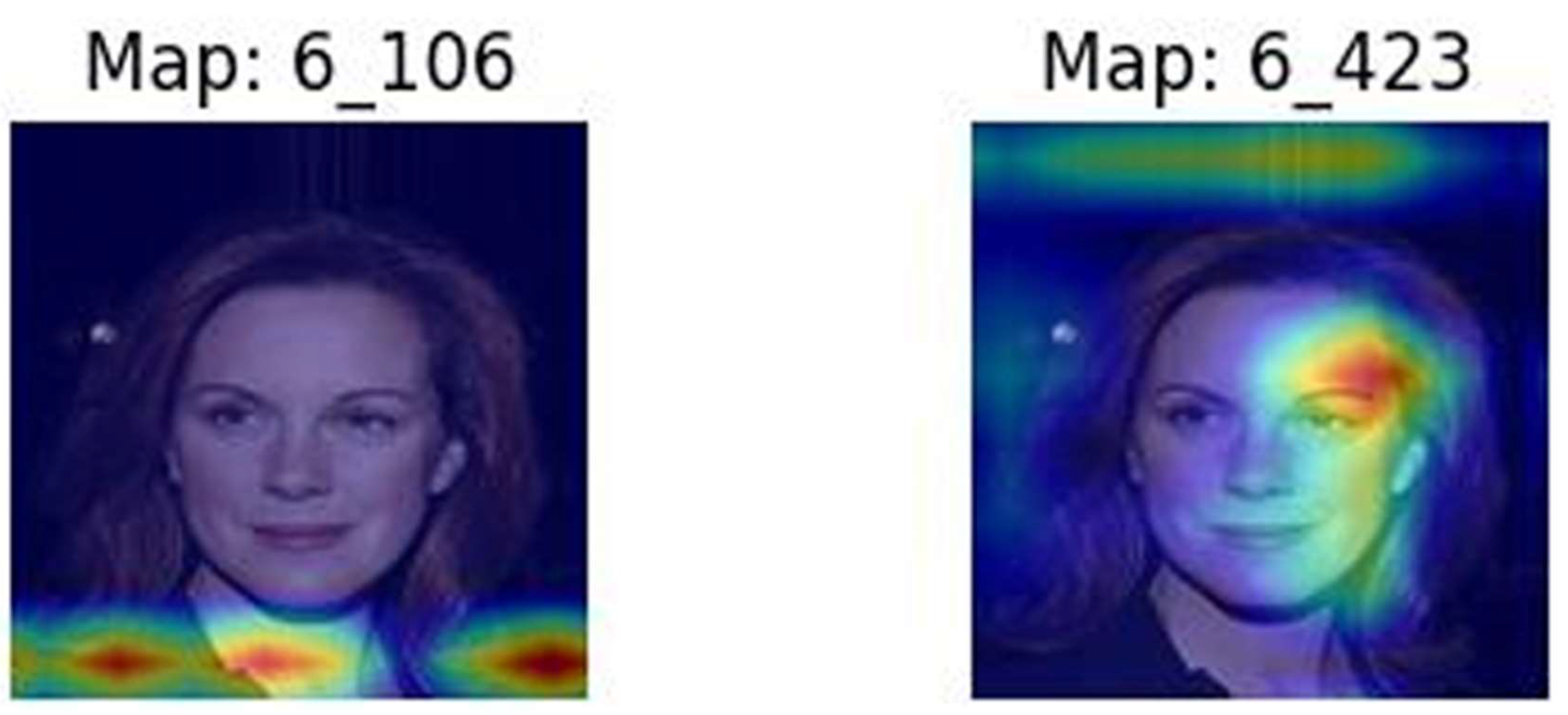

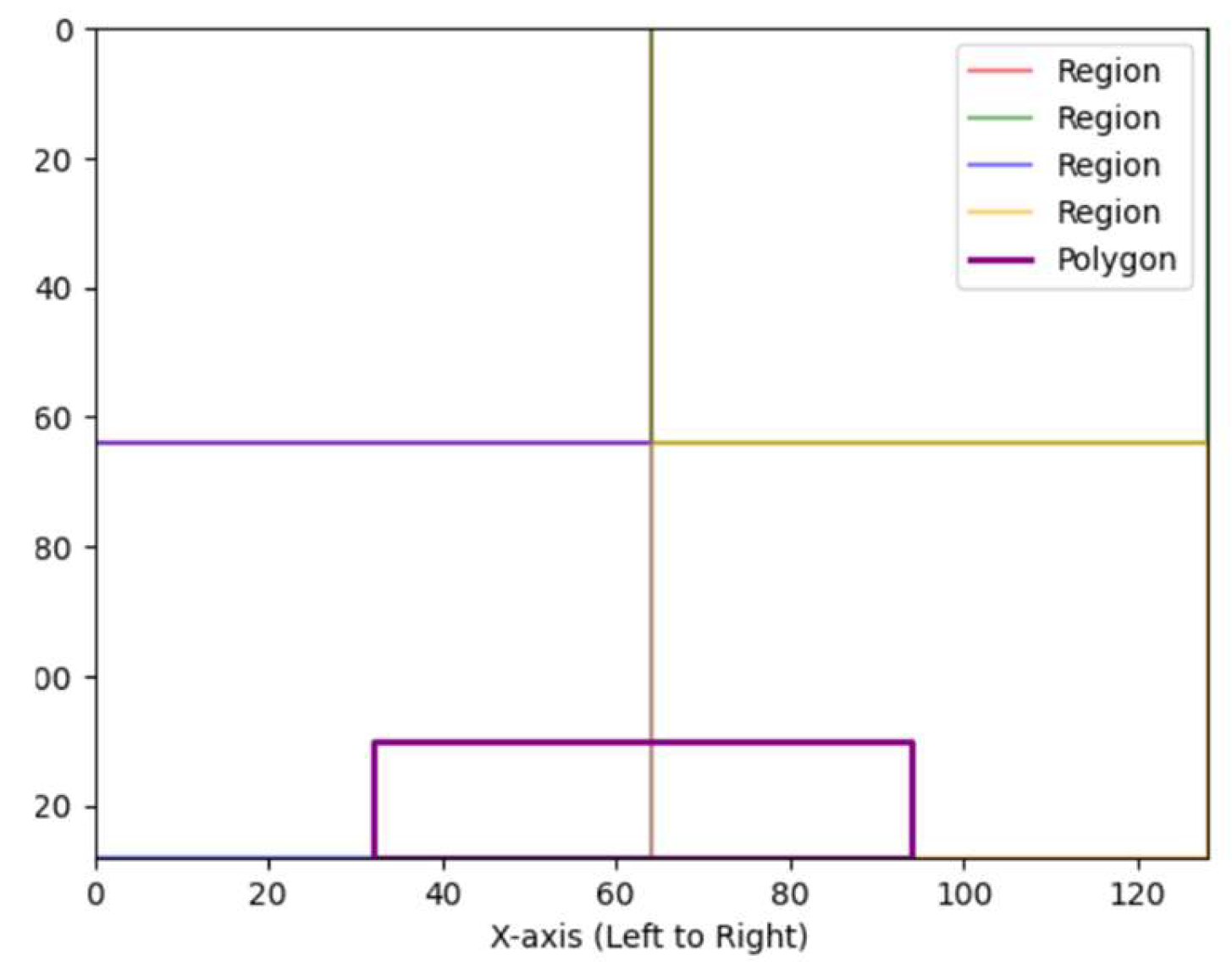

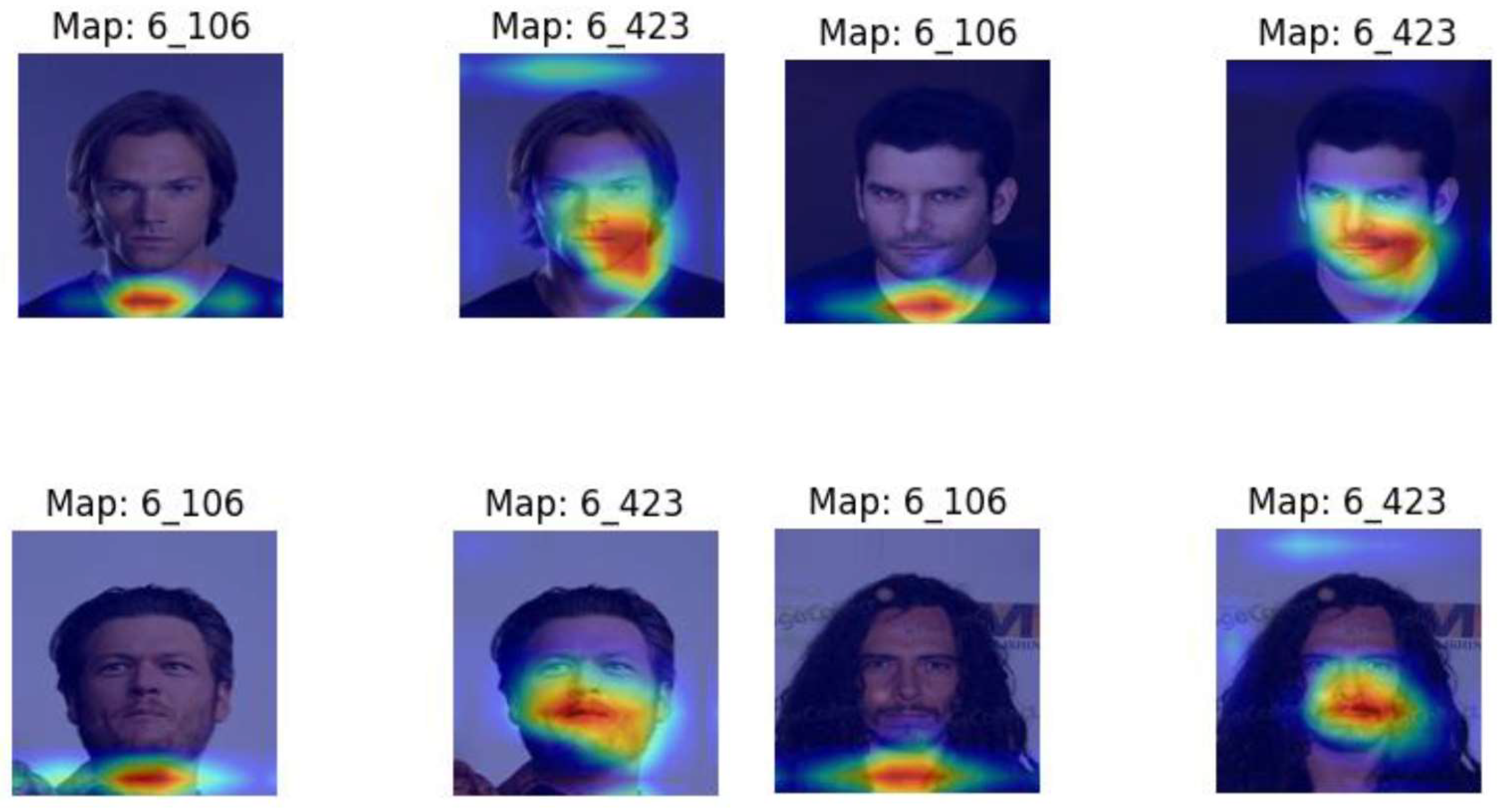

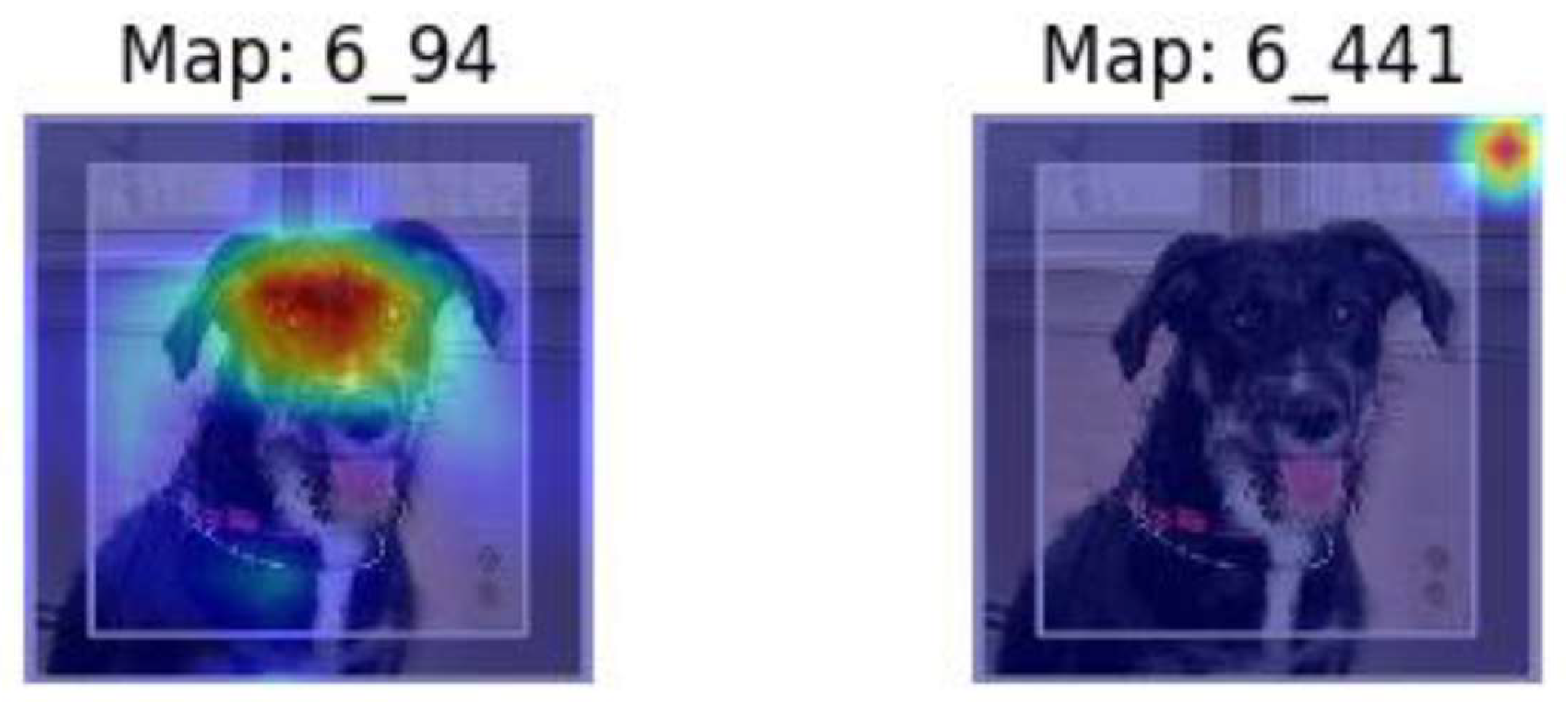

2.2.1. Feature extraction from feature maps

3. Results

3.1. System Configuration

3.2. Architecture Exploration

3.3. Experimental Study

3.3.1. Finetuning, Feature Selection and Image Superposition

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Russell, S. , and P. Norvig, P., 2020. Artificial Intelligence: A Modern Approach, 4th Ed, Prentice Hall.

- Simonyan, K. and Zisserman, A., 2014. Very deep convolutional networks for large-scale image recognition. arXiv preprint. arXiv:1409.1556.

- He, K. , Zhang, X. , Ren, S. and Sun, J., 2016. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition (pp. 770-778). [Google Scholar]

- Deng, J. , Dong, W., Socher, R., Li, L.J., Li, K. and Fei-Fei, L., 2009, June. Imagenet: A large-scale hierarchical image database. In 2009 IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition (pp. 248-255). Ieee.

- Krizhevsky, A. and Hinton, G., 2009. Learning multiple layers of features from tiny images.

- Szegedy, C. , Liu, W. , Jia, Y., Sermanet, P., Reed, S., Anguelov, D., Erhan, D., Vanhoucke, V. and Rabinovich, A., 2015. Going deeper with convolutions. In Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition (pp. 1-9). [Google Scholar]

- Tan, M. and Le, Q., 2019, May. Efficientnet: Rethinking model scaling for convolutional neural networks. In International conference on machine learning (pp. 6105-6114). PMLR.

- Sandler, M. , Howard, A. , Zhu, M., Zhmoginov, A. and Chen, L.C., 2018. Mobilenetv2: Inverted residuals and linear bottlenecks. In Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition (pp. 4510-4520). became opaque and the challenges of interpretation or explainability started raising concerns. [Google Scholar]

- Castelvecchi, D. , 2016. Can we open the black box of AI?. Nature News, 538(7623), p.20.

- Das, A. and Rad, P., 2020. Opportunities and challenges in explainable artificial intelligence (xai): A survey. arXiv preprint. arXiv:2006.11371.

- Ribeiro, M.T. , Singh, S. and Guestrin, C., August. " Why should I trust you?" Explaining the predictions of any classifier. In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD international conference on knowledge discovery and data mining (pp. 1135-1144). 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman, B. and Flaxman, S., 2017. European Union regulations on algorithmic decision-making and a “right to explanation”. AI magazine, 38(3), pp.50-57.

- Craven, M. and Shavlik, J., 1995. Extracting tree-structured representations of trained networks. Advances in neural information processing systems, 8.

- Zeiler, M.D. and Fergus, R., 2014. Visualizing and understanding convolutional networks. In Computer Vision–ECCV 2014: 13th European Conference, Zurich, Switzerland, September 6-12, 2014, Proceedings, Part I 13 (pp. 818-833). Springer International Publishing.

- Selvaraju, R.R. , Cogswell, M. , Das, A., Vedantam, R., Parikh, D. and Batra, D., 2017. Grad-cam: Visual explanations from deep networks via gradient-based localization. In Proceedings of the IEEE international conference on computer vision (pp. 618-626). [Google Scholar]

- Oh, S.J. , Schiele, B. and Fritz, M., 2019. Towards reverse-engineering black-box neural networks. Explainable AI: interpreting, explaining and visualizing deep learning, pp.121-144.

- Bach, S. , Binder, A., Montavon, G., Klauschen, F., Müller, K.R. and Samek, W., 2015. On pixel-wise explanations for non-linear classifier decisions by layer-wise relevance propagation. PloS one, 10(7).

- Achtibat, R., Dreyer, M., Eisenbraun, I., Bosse, S., Wiegand, T., Samek, W. and Lapuschkin, S., 2022. From" where" to" what": Towards human-understandable explanations through concept relevance propagation. arXiv preprint. arXiv:2206.03208.

- [Imagenet dataset, Available from: ImageNet.

- Simonyan, K. , and Zisserman, A., 2015. Very Deep Convolutional Networks For Large-Scale Image Recognition, ICLR 2015.

- Sharma, A. K. Human Interpretable Rule Generation from Convolutional Neural Networks using RICE: Rotation Invariant Contour Extraction, MS thesis, University of North Texas, Denton Texas, July 2024.

- Large-scale CelebFaces Attributes (CelebA) Dataset. Available online: https://mmlab.ie.cuhk.edu.hk/projects/CelebA.html (accessed on 15 January 2024.

- Kaggle Cats and Dogs Dataset. Available: https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/download/details.aspx?id=54765&msockid=3d36009b0d73606d12a7146f0c7b6140 (accessed on 02 February 2024).

| Parameter | Description and value |

| VGG-16 trainable layers | Last 2 convolutional layers from Block 5 |

| Number of dense layers used | 2 dense layers, 1024 units in layer 1 and 512 in layer 2 |

| Learning rate | .0017 |

| Epochs | 50 |

| Batch size | 512 |

| Early stopping | Yes, with patience value of 6 |

| Optimizer | Adam |

| Input image shape | (128,128,3) |

| Train test validation split | Training and validation partitions used as provided in source for both CelebA and Cats vs& Dogs datasets |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).