Submitted:

20 January 2025

Posted:

22 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

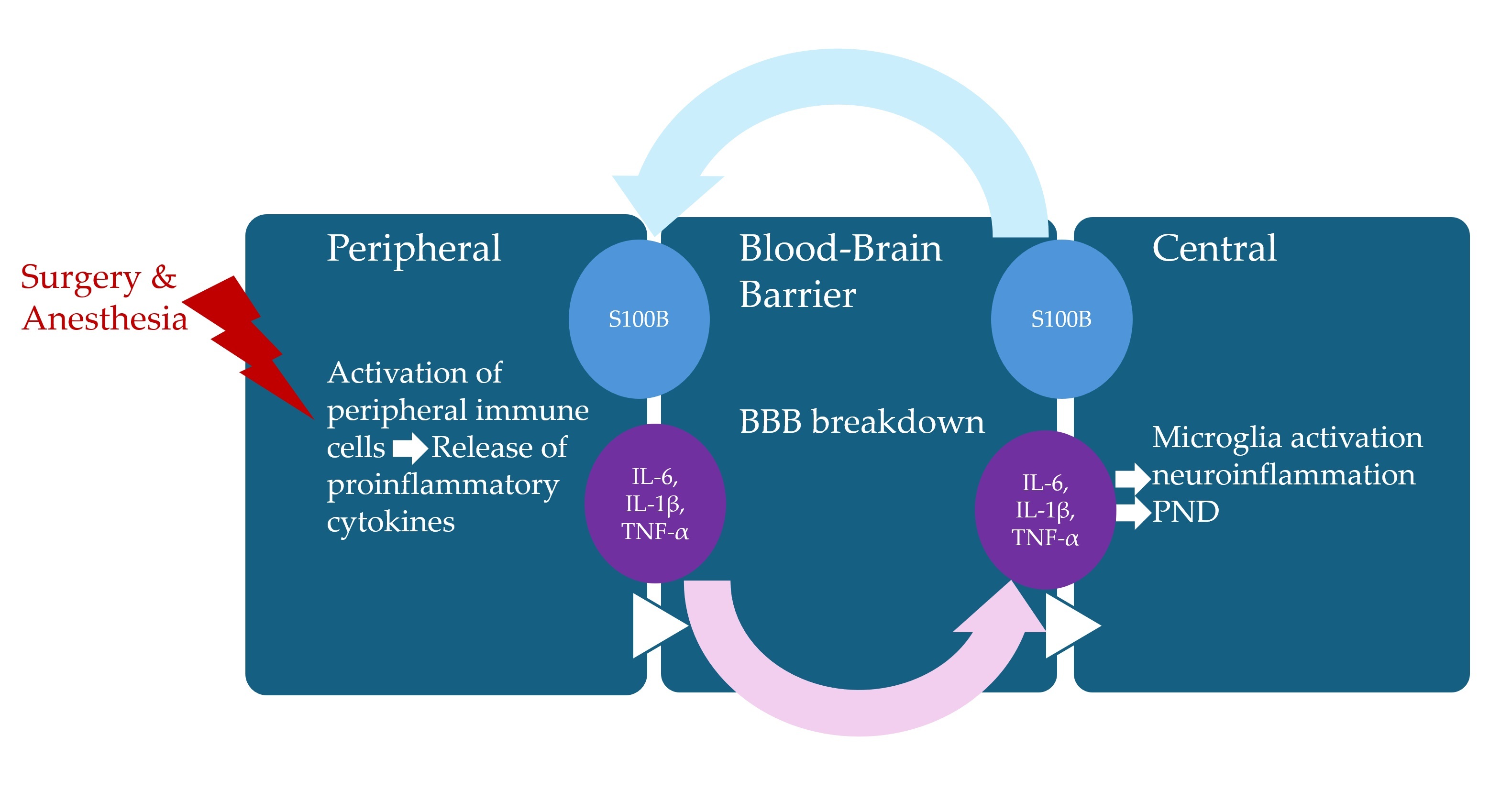

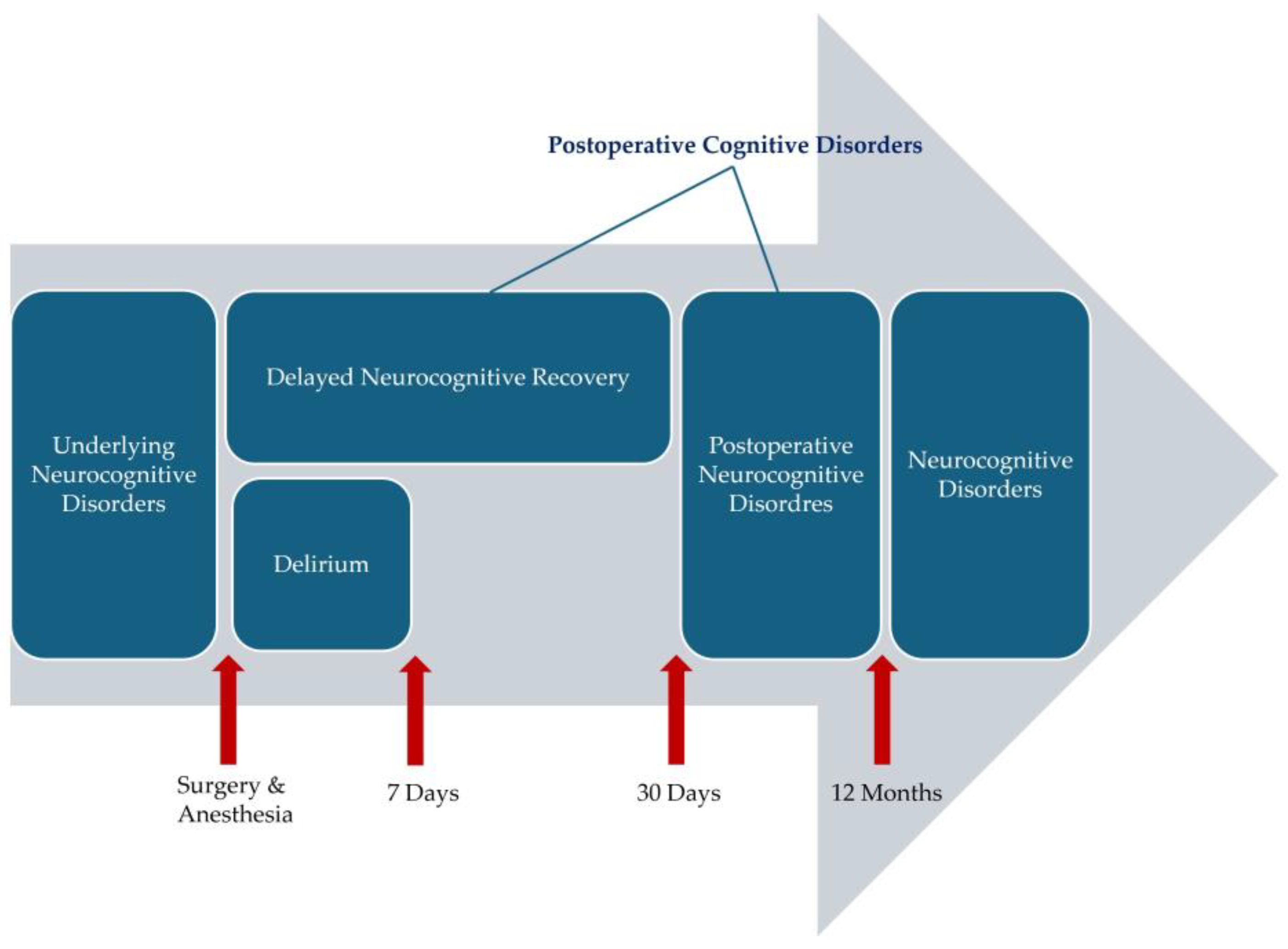

Perioperative neurocognitive disorders (PNDs), including postoperative delirium, delayed neurocognitive recovery, and long-term postoperative neurocognitive disorders, present significant challenges for older patients undergoing surgery. Inflammation is a protective mechanism triggered in response to external pathogens or cellular damage. Historically, the central nervous system (CNS) was considered immunoprivileged due to the presence of the blood–brain barrier (BBB), which serves as a physical barrier preventing systemic inflammatory changes from influencing the CNS. However, aseptic surgical trauma is now recognized to induce localized inflammation at the surgical site, further exacerbated by the release of peripheral pro-inflammatory cytokines, which can compromise BBB integrity. This breakdown of the BBB facilitates the activation of microglia, initiating a cascade of neuroinflammatory responses that may contribute to the onset of PNDs. This review explores the mechanisms underlying neuroinflammation, with a particular focus on the pivotal role of cytokines in the pathogenesis of PND.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. What Is PND?

2.1. Definition

2.2. Incidence

3. PND Pathogenesis

3.1. Neuroinflammation

3.2. Cytokines

3.3. Clinical Studies Investigating PNDs from the Perspective of Neuroinflammation and Cytokines

| Study | Sample size (n) | Cohort | Study type | Surgical procedure | CSF | Plasma |

| . | 114 | > 18 | prospective, observational cohort study | open heart surgery | POST: IL-6 higher in POD | |

| Hudetz JA et al. [82] | 114 | ≥ 55 | prospective, observational cohort study | open heart surgery | PRE-POST change: IL-6 higher in cognitive impairment | |

| Li YC et al. [83] | 37 | > 60 | prospective, observational cohort study | hip surgery | PRE-POST change: IL-6, S100B higher in POCD; IL-1b, TNF-a (no significance) | |

| Ji MH et al. [84] | 61 | 65 - 85 | prospective, observational cohort study | hip surgery | PRE: IL-1β higher in POCD; IL-6 (no significance) | PRE-POST change: IL-1β, IL-6 (no significance) |

| Liu P et al. [85] | 338 | ≥ 60 | prospective, observational cohort study | major noncardiac surgery | PRE-POST change: IL-6 higher in POD | |

| Reinsfelt B et al. [86] | 10 | 73 ± 6 yrs | prospective, observational cohort study | open heart surgery | PRE-POST change: IL-6, IL-8, TNF-a increased accompanied by increased AD-associated Aβ1–42 | |

| Westhoff D et al. [87] | 61 | ≥ 75 | RCT | hip surgery | PRE: IL-1RA, IL-6 higher in POD; IP-10 higher in POD (no significance); IL-15 lower in POD (no significance) | |

| Cape E et al. [43] | 43 | > 60 | prospective, observational cohort study | hip surgery | PRE: IL-1β, IL-1RA higher in POD; IFN-γ, IGF-1 (undetected) | |

| Capri M et al. [44] | 74 | > 65 | case-control study | any kind of surgery | PRE: IL-6 higher in POD; IL-2 lower in POD (no significance); IL-8, IL-10 (no difference) | |

| Kazmierski J et al. [45] | 113 | prospective, observational cohort study | open heart surgery | POST: IL-2, TNF-α increased | ||

| Lin GX et al. [46] | 50 | ≥ 60 | prospective, observational cohort study | major gastrointestinal surgery. | PRE-POST change: IL-6, HMGB1 higher in POCD | |

| Vasunilashorn SM et al. [47] | 566 | ≥70 | prospective, observational cohort study | major noncardiac surgery | PRE-POST change: IL-2, IL-6 higher in POD | |

| Skrede K et al. [48] | 19 | ≥ 65 | prospective, observational cohort study | hip surgery | PRE-POST change: MCP-1 higher in POD | |

| Zhang YH et al. [49] | 63 | ≥ 65 | prospective, observational cohort study | lumbar discectomy | PRE-POST change: IL-6, IL-10 higher in POCD | |

| Neerland ET et al. [50] | 149 | ≥ 60 | RCT | hip surgery | PRE: sIL-6R higher in POD (no significance) | PRE: IL-6, sIL-6R (no significance) |

| Shen H et al. [51] | 140 | ≥ 65 | prospective, observational cohort study | open abdominal surgery | PRE: IGF-1 lower in POD; IL-6 increased (no significance) | |

| Hirsch J et al. [26] | 10 | ≥ 55 | prospective, observational cohort study | major knee surgery | PRE: IFN-α2 higher in POD and IFN-α2, IL-10 lower in POD; PRE-POST change: IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, MCP-1 higher in POD and IL-10 higher in POCD | Delirium: PRE: MIP-1α, MIP-1β, IL-6 higher in POD increased and IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, IL-12, IFN-α2, IFN-γ lower in POCD; PRE-POST change: IFN-α2, IFN-γ, IL-4, IL-5, IL-12 lower in POD and IFN-α2, IL-12, and IL-4 lower in POCD |

| Kline R et al. [52] | 30 | ≥ 65 | prospective, observational cohort study | major noncardiac surgery | PRE-POST change: IL-6, IL-8, TNF-α higher in cognitive decline; IL-10 (no significance) | |

| Sun L et al. [53] | 112 | 65-85 | prospective, observational cohort study | oral cancer free flap surgery | PRE-POST change: IL-6 higher in POD | |

| Jiang J et al. [54] | 44 | ≥60 | prospective, observational cohort study | head and neck cancer | PRE: IGF-1 lower in POCD; PRE-POST change: TNF-α higher, IGF-1 lower in POCD | |

| Yu H et al. [55] | 51 | 18-65 | prospective, observational cohort study | cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy | PRE-POST change: IL-6, HMGB1,S100B higher in POCD; TNF-α (no significance) | |

| Guo HY [56] | 51 | 60-82 | prospective, observational cohort study | open heart surgery | POST: IL-1β, IL-6, MMP-3, MMP-9 higher in POCD | |

| Sajjad MU et al. [57] | 331 | ≥ 65 | prospective, observational cohort study | hip surgery | PRE: IL-8 higher in POCD; TNF-α, IL-1β (undetected) | |

| Chen Y et al. [58] | 266 | ≥ 18 | prospective, observational cohort study | open heart surgery | PRE-POST change: IL-6 higher in POD | |

| Lin X et al. [59] | 447 | ≥ 65 | prospective, observational cohort study | hip/knee surgery | PRE: IL-6, TNF-α higher in POD | PRE-POST change: IL-6, TNF-α higher in POD |

| Yuan Y et al. [60] | 34 | ≥ 65 | prospective observational case-control preliminary study | hip surgery | PRE-POST change: IL-6 higher in POD; IL-1β, TNF-α (no significance) | |

| Danielson M et al. [61] | 27 | 65-76 | prospective, observational cohort study | hip/knee surgery | PRE-POST change: IL-6, IL-8 higher in POCD (transiently increased CSF/serum albumin ratio & CSF, serumS100B) | |

| Casey CP et al. [62] | 114 | prospective, observational cohort study | major noncardiac surgery | PRE-POST change: IL-8 higher in POD (in relation with severity); IL-1β, IL-1RA, IL-2, IL-4, IL-6, IL-10, IL-12p70, MCP-1, TNF-α (no significance) | ||

| Kavrut Ozturk N et al. [63] | 82 | > 50 | prospective, observational cohort study | Robotic-Assisted Laparoscopic Radical Prostatectomy | PRE-POST change: S100B higher in POCD | |

| Ballweg T et al. [64] | 110 | prospective, observational cohort study | open thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysm /TEVAR | PRE-POST change: IL-8, IL-10 higher in POD; IL-1β, IL-1RA, IL-2 (no significance) | ||

| CheheiliSobbi S et al. [65] | 89 | ≥ 50 | prospective, observational cohort study | open heart surgery | PRE-POST change (ex vivo-stimulated production): TNF-α, IL-6, IL-10 higher in POD (no significance) | |

| Lv XC et al. [66] | 221 | > 18 | retrospective study | open heart surgery | PRE-POST change: IL-6 higher in POD | |

| Zhang S et al. [67] | 390 | > 18 | prospective, observational cohort study | open heart surgery | PRE-POST change: IL-6 higher in POD | |

| Taylor J et al. [68] | 72 | ≥ 65 yrs | prospective, observational cohort study | non-intracranial surgery | IL-6 correlates with S100B | PRE-POST change: S100B higher in POD |

| Wu JG et al. [69] | 64 | ≥ 21 yrs | prospective, observational cohort study | non-intracranial surgery | PRE-POST change: IL-18 (no significance) | PRE-POST change: IL-18 (no significance) |

| Khan SH et al. [70] | 71 | ≥ 18 yrs | secondary analysis of blood samples from a RCT | esophagectomy | PRE-POST change: IL-8, IL-10 higher in POD; S100B increase and IGF-1 (correlated with greater POD severity) | |

| Oren RL et al. [71] | 76 | 45–60 or ≥ 70 yrs | prospective observational study | spine surgery | PRE-POST change: IL-8, IL-6 higher in POD | |

| Zhang Y et al. [72] | 126 | ≥60 yrs | prospective, observational cohort study | hip/knee surgery | PRE-POST change: IL-6, sIL-6R higher in POD; IL-1β, IL-2, IL-4, IL-10, TNF-α (no significance) | |

| Su LJ et al. [73] | 318 | ≥ 18 yrs | prospective, observational cohort study | open heart surgery | Post: IL-6, TNF-α, sTNFR-1, sTNFR-2 higher in POD; IL-1β (no significance) | |

| Imai T et al. [74] | 221 | 24–88 yrs | retrospective study | head and neck cancer | POST: IL-6 higher in POD | |

| Taylor J et al. [75] | 170 | ≥ 65 yrs | prospective, observational cohort study | non-intracranial surgery | POST: IL-6 higher in cognitive decline | |

| Ruhnau J et al. [76] | 44 | ≥60 yrs | prospective, observational cohort study | spine surgery | PRE-POST change: S100B, IL-6, IL-1β increased in POD | |

| Lozano-Vicario L et al. [77] | 60 | ≥ 75 yrs | prospective, observational cohort study | hip surgery | PRE: CXCL9 lower in POD | PRE: CXCL9 lower in POD |

| Zhang S et al. [78] | 212 | ≥ 18 yrs | prospective, observational cohort study | open heart surgery | POST: IL-6 higher in POCD | |

| Ko H et al. [79] | 43 | > 30 yrs | prospective, observational cohort study | open heart surgery | PRE: TNF-α lower in POD; IL-6 higher (No significance), IL-1β (no difference) |

4. Influence of Anesthesia on PND

4.1. Impact of Anesthetic Method on PND from the Perspective of Neuroinflammation and Cytokines

| Study | Sample size (n) | Cohort (yrs) | Study type | Surgical procedure | Anesthetic exposure | Key findings |

| Lili X et al. [97] | 40 | > 65 | RCT | elective abdominal surgery | UTI vs control | lower incidence of POCD in the UTI group; S100B, IL-6 decreased in the UTI group |

| Jildenstål PK et al. [98] | 450 | RCT | elective eye surgery | AAI vs control | IL-6 lower in the AAI group; IL-6 higher in patients with a MMSE < 25 | |

| Li Y et al. [99] | 120 | > 60 | RCT | laparoscopic cholecystectomy | DEX vs control | IL-1β, IL-6 lower in the DEX group; IL-1β, IL-6 higher in patients who developed POCD on day 1 following surgery |

| Jia Y et al. [100] | 240 | ≥70 | RCT | open colorectal surgery | fast-track surgery vs traditional | POD occurrence lower in the fast-track surgery group; IL-6 decreased in fast-track surgery group |

| Chen K et al. [101] | 87 | > 65 | RCT | spine surgery | lidocaine vs control | MMSE scores markedly higher in the lidocaine group; S100B, IL-6 decreased in the lidocaine group |

| Qiao Y et al. [102] | 90 | 65-75 | RCT | resection of an esophageal carcinoma | Sevo vs Sevo-PRE methylprednisolone vs IV propofol | MMSE, MoCA scores lower in the Sevo group; TNF-α, IL-6, S100B higher in the Sevo group > IV propofol group > Sevo + PRE methylprednisolone |

| Chen W et al. [103] | 148 | 61-89 | retrospective study, | DEX vs control | incidence of POCD lower in the Dex group; IL-6, TNF-α lower in the Dex group | |

| Wang KY et al. [104] | 80 | ≥ 60 | RCT | radical resection foresophageal cancer under one lung ventilation | UTI vs control | incidence of POCD lower in the UTI group; S100B, IL-6 lower, IL-10 higher in the UTI group |

| Xin X et al. [105] | 120 | > 65 | RCT | hip arthroplasty | PRE hypertonic saline vs normal saline | lower risk of POD in the PRE hypertonic group; higher TNF-α associated with POD, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-10, S100B not significantly related to POD |

| He Z et al. [106] | 90 | 65-75 | RCT | laparotomy colon carcinoma surgery | ischemic preconditioning vs control | MoCA scores higher in theischemic preconditioning group; IL-1β, TNF-α, S100B lower in the remote ischemic preconditioning group |

| Lu XY et al. [107] | 70 | RCT | radical surgery for cervical cancer | remifentanil vs fentanyl | POCD occurrence lower in the remifentanil group; IL-6, TNF-α lower in the remifentanil group | |

| Zhang H et al. [108] | 120 | 65-75 | RCT | esophageal carcinoma resection | midazolam + propofol vs midazolam + Sevo vs DEX + propofol vs DEX+ Sevo | MMSE and MoCA scores lower in the midazolam + Sevo (vs midazolam + propofol), MMSE and MoCA scores higher in the DEX + Sevo (vs midazolam); IL-6, TNF-α, S100B higher in the midazolam + Sevo (vs midazolam + propofol), IL-6, TNF-α, S100B lower in the DEX + Sevo (vs midazolam); POCD incidence higher in Sevo anesthesia and DEXvcould alleviate POCD |

| Lee C et al. [109] | 354 | > 65 | RCT | laparoscopic major non-cardiac surgery | intraoperative DEX infusion vs intraoperative DEX bolus vs control | POCD incidence and duration lower in DEX infusion, POCD duration lower in DEX bolus (vs control); IL-6 lower in DEX groups |

| Quan C et al. [110] | 120 | ≥ 60 | RCT | abdominal surgery | Deep (BIS target 30–45) vs Light (BIS target 45-60) | POCD incidence lower in the Deep group (at 7 days after surgery); IL-1β lower in the Deep group, IL-10, S100B no significance |

| Kim JA et al. [111] | 143 | 18-75 | RCT | thoracoscopic lung resection | DEX-Sevo vs Sevo | emergence agitation lower in Dex-Sevo group, POD no difference; IL-8, IL-10 lower & IL6/IL10 ratio, IL8/IL10 ratio in Dex-Sevo group, IL-6 no significance |

| Wang Y et al. [112] | 100 | 20–60 | RCT | thoracotomy for esophageal cancer | intercostal nerve block vs control | MMSE score higher in the intercostal nerve block group; IL-6, TNF-α lower, IL-10 higher in the intercostal nerve block group |

| Hassan WF et al. [113] | 80 | RCT | laparoscopic cholecystectomy | magnesium sulphate vs control | POST S100B higher in the control group (vs PRE), no difference in the magnesium sulphate group | |

| Xin X et al. [114] | 60 | > 65 | RCT | laparoscopic cholecystectomy | DEX vs control | POD incidence lower in DEX group; TNF-α lower, IL-10 higher in Dex group |

| Mei B et al. [115] | 366 | ≥ 65 | RCT | total knee arthroplasty | spinal anesthesia supplemented with propofol vs Dex | POD incidence lower in DEX group; S100B higher in the propofol group, TNF-α lower, IL-6 no difference |

| Uysal Aİ et al. [116] | 114 | > 65 | RCT | trochanteric femur fracture surgery | spinal anesthesia supplemented with paracetamol vs femoral nerve block | POD incidence lower in the femoral nerve block group; IL-8 lower in the femoral nerve block group, IL-6 no significance |

| Wang J et al. [117] | 71 | ≥ 65 | RCT | Prone Spinal Surgery | lung-protective ventilation vs conventional mechanical ventilation | POD incidence lower in the lung protective ventilation group; IL-6 lower, IL-10 higher in the lung protective ventilation group |

| Hu J et al. [118] | 177 | 60-80 | RCT | transthoracic oesophagectomy | TIVA vs TIVA-DEX | POD incidence, emergence agitation lower in TIVA-DEX group; IL-6 lower TIVA-DEX group |

| Oh CS et al. [119] | 82 | > 50 | RCT | total hip replacement | moderate vs deep NMB | POD no difference; IL-6 lower in the deep NMB group |

| Jiang P et al. [120] | 142 | 18-80 | RCT | esophagectomy | general anesthesia vs general anesthesia combined with epidural anesthesia | MoCA score higher in the general anesthesia combined with epidural anesthesia group; IL-6, IL-8, TNF-α lower in the general anesthesia combined with epidural anesthesia group |

| Li Y et al. [121] | 544 | ≥60 | RCT | laparoscopic abdominal surgery | Sevo vs propofol | POCD no difference; associated with an increased likelihood of delayed neurocognitive recovery; IL-6 higher in POCD |

| Zhang Z et al. [122] | 174 | 18–79 | RCT | DEX vs control | POCD incidence lower in DEX group; TNF-α, IL-6 lower in Dex group | |

| Huang Q et al. [123] | 90 | ≥ 60 | RCT | laparoscopic radical gastrointestinal tumor resections | insulin (20 U/0.5 mL insulin administered intranasally) vs control | POD incidence lower in the insulin group; TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β lower in the insulin group |

| Feng T et al. [124] | 60 | 18–80 | RCT | total hip arthroplasty | inside approach of the fascia iliaca compartment block (FICB) vs outside approach of the FICB | POCD incidence lower in the inside approach group; IL-1b, IL-6 lower in the inside approach group |

| Chen S et al. [125] | 103 | > 65 | RCT | cardiac surgery | transversus thoracis muscle plane (TTMP) block vs control | POCD lower in TTMP block group; IL-6,TNF-α,S-100β lower in TTMP block group |

| Wang W et al. [126] | 100 | 60-85 | RCT | DEX vs control | MMSE and MoCA scores higher in Dex group; IL-6,TNF-α,S-100B lower in Dex group | |

| Wang JY et al. [127] | 159 | 65-85 | RCT | thoracoscopic lobectomy | goal-directed therapy vs conventional | POD incidence lower in the goal-directed therapy group; IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, S-100B lower in the goal-directed therapy group |

| Tang Y et al. [128] | 120 | 60-80 | RCT | hepatic lobectomy | 0.3 μg, 0.6 μg/kg/hr DEX vs control | POD & POCD incidence lower in 0.3 μg, 0.6 μg/kg/hr DEX group; TNF-α, IL-1β lower, IL-10 higher in 0.3 μg, 0.6 μg/kg/hr Dex group |

| Xiang XB et al. [129] | 168 | 65-80 | RCT | laparoscopic gastrointestinal surgery | methylprednisolone vs control | POD incidence lower in the methylprednisolone group; TNF-α loer in the methylprednisolone group; methylprednisolone does not reduce the severity of POD |

| Kurup MT et al. [130] | 64 | 60-80 | RCT | open abdominal surgery | DEX vs lidocaine | TNF-α, IL-6, S100B levels (no significance), IL-1 decreased in Dex (vs lidocaine), POCD no significance |

| Lai Y et al. [131] | 90 | > 65 | RCT | thoracoscopic lobectomy or segmentectomy | DEX vs lidocaine vs control | POD incidence no significance; IL-6, TNF-α lower in Dex and lidocaine |

| Xu F et al. [132] | 84 | ≥ 60 | RCT | shoulder arthroscopy | PRE hypertonic saline vs normal saline | POD lower in the PRE hypertonic saline group; IL-6, TNF-α lower in the PRE hypertonic saline group |

| Han C et al. [133] | 84 | ≥ 60 | RCT | gastrointestinal surgery | esketamine vs control | incidence of delayed neurocognitive recovery lower in the esketamine group, no difference in POCD at 3 months after surgery; IL-6 and S100B lower in the esketamine group |

| Zhu M et al. [134] | 60 | > 65 | RCT | hip surgery | quadratus lumborum block vs control | POCD incidence lower in the quadratus lumborum block group; HMGB1, IL-6 lower in the quadratus lumborum block group |

| Zhi Y et al. [135] | 140 | 60-85 | RCT | TIVA vs TIVA-etomidate | MMSE, MoCA scores higher in TIVA-etomidate group; IL-6, S100B lower, IL-10 higher in TIVA-etomidate group | |

| Mi Y et al. [136] | 116 | ≥ 60 | RCT | noncardiac surgery | insulin (40 U/1 mL administered intranasally) vs control | POCD incidence lower in the insulin group; TNF-α lower in the insulin group |

| Sun M et al. [137] | 140 | RCT | orthopaedic surgery or pancreatic surgery | insulin (40 IU/400 μL administered intranasally) vs control | MMSE and MoCA-B scores higher, POD incidence lower in the insulin group; IL-6, S100B lower in the insulin group | |

| Fu W et al. [138] | 132 | 60-80 | RCT | ureteroscopic holmium laser lithotripsy | etomidate-remifentanil-DEX vs control | MMSE scores higher in the etomidate-remifentanil-DEX group; S100B lower in the etomidate-remifentanil-Dex group |

| Luo T et al. [139] | 129 | RCT | non-cardiac thoracic surgery | 0.2, 0.5 mg/kg esketamine vs control | MMSE scores no difference; IL-6, S100B lower in the esketamine groups | |

| Hsiung PY et al. [140] | 110 | > 20 | RCT | thoracoscopic tumor resection | nonintubated vs intubated | Qmci-TW higher in the nonintubated group; IL-6 lower in the nonintubated group |

| Yin WY et al. [141] | 94 | 60-85 | retrospective study, | orthopedic surgery | paracoxib vs control | MoCA score higher in the paracoxib group; TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β lower, IL-10, MCP-1 higher in the paracoxib group |

| Huo QF et al. [142] | 397 | 65-80 | RCT | Total hip arthroplasty | DEX vs UTI vs DEX-UTI | POCD incidence lower in DEX-UTI group; IL-6 lower in Dex-UTI group |

| Hindman BJ et al. [143] | 76 | > 65 | RCT | posterior lumbar fusion | tranexamic acid vs control | POD incidence no difference; TNF-α lower in the tranexamic acid group, IL-10, IL-6, S100B no significance |

| Ye C et al. [144] | 218 | 65-90 | RCT | thoracolumbar compression fracture surgery | DEX vs control | POD incidence lower in DEX group; IL-6, TNF-α lower in DEX group, IL-1 no significance |

| Ma X et al. [145] | 108 | 18–70 | RCT | resection of gastrointestinal tumor resection | narcotrend vs physician experience | POCD incidence lower in the narcotrend group; IL-1β, TNF-α lower in the narcotrend group |

4.2. Impact of Dexmedetomidine on PND from the Perspective of Neuroinflammation and Cytokines

4.3. Potential Therapeutic Approaches Targeting Cytokines

5. Future Directions

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fowler, A.J.; Abbott, T.E.F.; Prowle, J.; Pearse, R.M. Age of patients undergoing surgery. Br. J. Surg. 2019, 106, 1012–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, H.; Xu, L.M.; DX, D.X. Perioperative neurocognitive disorders: A narrative review focusing on diagnosis, prevention, and treatment. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 2022, 28, 1147–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, T.; Velagapudi, R.; Terrando, N. Neuroinflammation after surgery: from mechanisms to therapeutic targets. Nat. Immunol. 2020, 21, 1319–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safavynia, S.A.; Goldstein, P.A. The Role of Neuroinflammation in Postoperative Cognitive Dysfunction: Moving From Hypothesis to Treatment. Front. Psychiatry 2019, 9, 752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evered, L.; Silbert, B.; Knopman, D.S.; Scott, D.A.; DeKosky, S.T.; Rasmussen, L.S.; Oh, E.S.; Crosby, G.; Berger, M.; Eckenhoff, R.G. Recommendations for the nomenclature of cognitive change associated with anaesthesia and surgery-2018. Br. J. Anaesth. 2018, 121, 1005–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berian, J.R.; Zhou, L.; Russell, M.M.; Hornor, M.A.; Cohen, M.E.; Finlayson, E.; Ko, C.Y.; Rosenthal, R.A.; Robinson, T.N. Postoperative Delirium as a Target for Surgical Quality Improvement. Ann. Surg. 2018, 268, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, A.R.; Regueira, P.; Albuquerque, E.; Baldeiras, I.; Cardoso, A.L.; Santana, I.; Cerejeira, J. Estimates of Geriatric Delirium Frequency in Noncardiac Surgeries and Its Evaluation Across the Years: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2021, 22, 613–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oldroyd, C.; Scholz, A.F.M.; Hinchliffe, R.J.; McCarthy, K.; Hewitt, J.; Quinn, T.J. A systematic review and meta-analysis of factors for delirium in vascular surgical patients. J. Vasc. Surg. 2017, 66, 1269–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aitken, S.J.; Blyth, F.M.; Naganathan, V. Incidence, prognostic factors and impact of postoperative delirium after major vascular surgery: A meta-analysis and systematic review. Vasc. Med. 2017, 22, 387–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Yin, Y.; Jin, M.; Li, B. The risk factors for postoperative delirium in adult patients after hip fracture surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2021, 36, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saljuqi, A.T.; Hanna, K.; Asmar, S.; Tang, A.; Zeeshan, M.; Gries, L.; Ditillo, M.; Kulvatunyou, N.; Castanon, L.; Joseph, B. Prospective Evaluation of Delirium in Geriatric Patients Undergoing Emergency General Surgery. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2020, 230, 758–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaiwat, O.; Chanidnuan, M.; Pancharoen, W.; Vijitmala, K.; Danpornprasert, P.; Toadithep, P.; Thanakiattiwibun, C. Postoperative delirium in critically ill surgical patients: incidence, risk factors, and predictive scores. BMC Anesthesiol. 2019, 19, 39. [Google Scholar]

- Moller, J.T.; Cluitmans, P.; Rasmussen, L.S.; Houx, P.; Rasmussen, H.; Canet, J.; Rabbitt, P.; Jolles, J.; Larsen, K.; Hanning, C.D.; et al. Long-term postoperative cognitive dysfunction in the elderly ISPOCD1 study. ISPOCD investigators. International Study of Post-Operative Cognitive Dysfunction. Lancet 1998, 351, 857–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brodier, E.A.; Cibelli, M. Postoperative cognitive dysfunction in clinical practice. BJA Educ. 2021, 21, 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paredes, S.; Cortínez, L.; Contreras, V.; Silbert, B. Post-operative cognitive dysfunction at 3 months in adults after non-cardiac surgery: a qualitative systematic review. Acta Anaesthesiol. Scand. 2016, 60, 1043–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swarbrick, C.J.; Partridge, J.S.L. Evidence-based strategies to reduce the incidence of postoperative delirium: a narrative review. Anaesthesia 2022, 77 Suppl 1, 92–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, W.; Lu, W.; Jiang, X.; Xiong, C.; Chai, H.; Cai, L.; Lan, Z. Current Progress on Neuroinflammation-mediated Postoperative Cognitive Dysfunction: An Update. Curr. Mol. Med. 2023, 23, 1077–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louveau, A.; Harris, T.H.; Kipnis, J. Revisiting the Mechanisms of CNS Immune Privilege. Trends Immunol. 2015, 36, 569–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauf, A.; Badoni, H.; Abu-Izneid, T.; Olatunde, A.; Rahman, M.M.; Painuli, S.; Semwal, P.; Wilairatana, P.; Mubarak, M.S. Neuroinflammatory Markers: Key Indicators in the Pathology of Neurodegenerative Diseases. Molecules 2022, 27, 3194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margraf, A.; Ludwig, N.; Zarbock, A.; Rossaint, J. Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome After Surgery: Mechanisms and Protection. Anesth. Analg. 2020, 131, 1693–1707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, S.; Yang, H.; Huang, F.; Fan, W. Systemic inflammation, neuroinflammation and perioperative neurocognitive disorders. Inflamm. Res. 2023, 72, 1895–1907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kadry, H.; Noorani, B.; Cucullo, L. A blood-brain barrier overview on structure, function, impairment, and biomarkers of integrity. Fluids Barriers CNS. 2020, 17, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, X.; Hussain, B.; Chang, J. Peripheral inflammation and blood-brain barrier disruption: effects and mechanisms. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 2021, 27, 36–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishibori, M.; Wang, D.; Ousaka, D.; Wake, H. High Mobility Group Box-1 and Blood-Brain Barrier Disruption. Cells 2020, 9, 2650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engblom, D.; Ek, M.; Saha, S.; Ericsson-Dahlstrand, A.; Jakobsson, P.J.; Blomqvist, A. Prostaglandins as inflammatory messengers across the blood-brain barrier. J. Mol. Med. (Berl). 2002, 80, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirsch, J.; Vacas, S.; Terrando, N.; Yuan, M.; Sands, L.P.; Kramer, J.; Bozic, K.; Maze, M.M.; Leung, J.M. Perioperative cerebrospinal fluid and plasma inflammatory markers after orthopedic surgery. J Neuroinflammation 2016, 13, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinsfelt, B.; Ricksten, S.E.; Zetterberg, H.; Blennow, K.; Fredén-Lindqvist, J.; Westerlind, A. Cerebrospinal fluid markers of brain injury, inflammation, and blood-brain barrier dysfunction in cardiac surgery. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2012, 94, 549–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Dong, Y.; Wang, H.; Culley, D.J.; Marcantonio, E.R.; Crosby, G.; Tanzi, R.E.; Zhang, Y.; Xie, Z. Peripheral surgical wounding and age-dependent neuroinflammation in mice. PloS One 2014, 9, e96752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terrando, N.; Eriksson, L.I.; Ryu, J.K.; Yang, T.; Monaco, C.; Feldmann, M.; Jonsson Fagerlund, M.; Charo, I.F.; Akassoglou, K.; Maze, M. Resolving postoperative neuroinflammation and cognitive decline. Ann. Neurol. 2011, 70, 986–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodburn, S.C.; Bollinger, J.L.; Wohleb, E.S. The semantics of microglia activation: neuroinflammation, homeostasis, and stress. J. Neuroinflammation 2021, 18, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxena, S.; Kruys, V.; Vamecq, J.; Maze, M. The Role of Microglia in Perioperative Neuroinflammation and Neurocognitive Disorders. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2021, 13, 671499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, Y.; Liu, J.; Wang, B.; Sun, M.; Yang, H. Microglia in the Neuroinflammatory Pathogenesis of Alzheimer's Disease and Related Therapeutic Targets. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 856376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isik, S.; Yeman Kiyak, B.; Akbayir, R.; Seyhali, R.; Arpaci, T. Microglia Mediated Neuroinflammation in Parkinson's Disease. Cells 2023, 12, 1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, T.W.; Chen, C.M.; Chang, K.H. Biomarker of Neuroinflammation in Parkinson's Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 4148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thakur, S.; Dhapola, R.; Sarma, P.; Medhi, B.; Reddy, D.H. Neuroinflammation in Alzheimer's Disease: Current Progress in Molecular Signaling and Therapeutics. Inflammation 2023, 46, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opal, S.M.; DePalo, V.A. Anti-inflammatory cytokines. Chest 2000, 117, 1162–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinarello, C.A. Proinflammatory cytokines. Chest 2000, 118, 503–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zbóril, S.; Schmidt, A.P.; Oses, J.P.; Wiener, C.D.; Portela, L.V.; Souza, D.O.; Auler, J.O.C.; Carmona, M.J.C.; Fugita, M.S.; Flor, P.B.; et al. S100B protein and neuron-specific enolase as predictors of postoperative cognitive dysfunction in aged dogs: a case-control study. Vet. Anaesth. Analg. 2020, 47, 740–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terrando, N.; Monaco, C.; Ma, D.; Foxwell, B.M.; Feldmann, M.; Maze, M. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha triggers a cytokine cascade yielding postoperative cognitive decline. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 20518–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kono, M.; Yoshida, N.; Tsokos, G.C. . Metabolic control of T cells in autoimmunity. Curr. Opin. Rheumatol. 2020, 32, 192–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, C.; Feng, X.; He, S.; Zhang, Y.; Maze, M. Interleukin-6 trans-signalling in hippocampal CA1 neurones mediates perioperative neurocognitive disorders in mice. Br. J. Anaesth. 2022, 129, 923–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, C.; Xie, T.; Pan, K.; Deng, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Li, N.; Bian, J.; Deng, X.; Zha, Y. Acetate attenuates perioperative neurocognitive disorders in aged mice. Aging (Albany NY) 2020, 12, 3862–3879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cape, E.; Hall, R.J.; van Munster, B.C.; de Vries, A.; Howie, S.E.; Pearson, A.; Middleton, S.D.; Gillies, F.; Armstrong, I.R.; White, T.O.; et al. Cerebrospinal fluid markers of neuroinflammation in delirium: a role for interleukin-1β in delirium after hip fracture. J. Psychosom. Res. 2014, 77, 219–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Capri, M.; Yani, S.L.; Chattat, R.; Fortuna, D.; Bucci, L.; Lanzarini, C.; Morsiani, C.; Catena, F.; Ansaloni, L.; Adversi, M.; et al. Pre-Operative, High-IL-6 Blood Level is a Risk Factor of Post-Operative Delirium Onset in Old Patients. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne). 2014, 5, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazmierski, J.; Banys, A.; Latek, J.; Bourke, J.; Jaszewski, R. Raised IL-2 and TNF-α concentrations are associated with postoperative delirium in patients undergoing coronary-artery bypass graft surgery. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2014, 26, 845–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, G.X.; Wang, T.; Chen, M.H.; Hu, Z.H.; Ouyang, W. Serum high-mobility group box 1 protein correlates with cognitive decline after gastrointestinal surgery. Acta Anaesthesiol. Scand. 2014, 58, 668–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasunilashorn, S.M.; Ngo, L.; Inouye, S.K.; Libermann, T.A.; Jones, R.N.; Alsop, D.C.; Guess, J.; Jastrzebski, S.; McElhaney, J.E.; Kuchel, G.A.; et al. Cytokines and Postoperative Delirium in Older Patients Undergoing Major Elective Surgery. J. Gerontol. A. Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2015, 70, 1289–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skrede, K.; Wyller, T.B.; Watne, L.O.; Seljeflot, I.; Juliebø, V. Is there a role for monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 in delirium? Novel observations in elderly hip fracture patients. BMC Res. Notes 2015, 8, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.H.; Guo, X.H.; Zhang, Q.M.; Yan, G.T.; Wang, T.L. Serum CRP and urinary trypsin inhibitor implicate postoperative cognitive dysfunction especially in elderly patients. Int. J. Neurosci. 2015, 125, 501–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neerland, B.E.; Hall, R.J.; Seljeflot, I.; Frihagen, F.; MacLullich, A.M.; Raeder, J.; Wyller, T.B.; Watne, L.O. Associations Between Delirium and Preoperative Cerebrospinal Fluid C-Reactive Protein, Interleukin-6, and Interleukin-6 Receptor in Individuals with Acute Hip Fracture. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2016, 64, 1456–1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, H.; Shao, Y.; Chen, J.; Guo, J. Insulin-Like Growth Factor-1, a Potential Predicative Biomarker for Postoperative Delirium Among Elderly Patients with Open Abdominal Surgery. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2016, 22, 5879–5883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kline, R.; Wong, E.; Haile, M.; Didehvar, S.; Farber, S.; Sacks, A.; Pirraglia, E.; de Leon, M.J.; Bekker, A. Peri-Operative Inflammatory Cytokines in Plasma of the Elderly Correlate in Prospective Study with Postoperative Changes in Cognitive Test Scores. Int. J. Anesthesiol. Res. 2016, 4, 313–321. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sun, L.; Jia, P.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Jiang, H.; Jiang, W.; Guo, Y. Production of inflammatory cytokines, cortisol, and Aβ1-40 in elderly oral cancer patients with postoperative delirium. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2016, 12, 2789–2795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, J.; Lv, X.; Liang, B.; Jiang, H. Circulating TNF-α levels increased and correlated negatively with IGF-I in postoperative cognitive dysfunction. Neurol. Sci. 2017, 38, 1391–1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Dong, R.; Lu, Y.; Yang, X.; Chen, C.; Zhang, Z.; Peng, M. Short-Term Postoperative Cognitive Dysfunction and Inflammatory Response in Patients Undergoing Cytoreductive Surgery and Hyperthermic Intraperitoneal Chemotherapy: A Pilot Study. Mediators Inflamm. 2017, 2017, 3605350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.Y. Significance of interleukin and matrix metalloproteinase in patients with cognitive dysfunction after single valve replacement. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2017, 21, 3129–3133. [Google Scholar]

- Sajjad, M.U.; Blennow, V.K.; Knapskog, A.B.; Idland, A.V.; Chaudhry, F.A.; Wyller, T.B.; Zetterberg, H.; Watne, L.O. Cerebrospinal Fluid Levels of Interleukin-8 in Delirium, Dementia, and Cognitively Healthy Patients. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2020, 73, 1363–1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Lu, S.; Wu, Y.; Shen, Y.; Zhao, H.; Ding, S.; Feng, X.; Sun, L.; Tao, X.; Li, J.; et al. Change in Serum Level of Interleukin 6 and Delirium After Coronary Artery Bypass Graft. Am. J. Crit. Care 2019, 28, 462–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Tang, J.; Liu, C.; Li, X.; Cao, W.; Wang, B.; Dong, R.; Xu, W.; Yu, X.; Wang, M.; et al. Cerebrospinal fluid cholinergic biomarkers are associated with postoperative delirium in elderly patients undergoing Total hip/knee replacement: a prospective cohort study. BMC Anesthesiol. 2020, 20, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Li, Z.; Yang, N.; Han, Y.; Ji, X.; Han, D.; Wang, X.; Li, Y.; Liu, T.; Yuan, F.; et al. Exosome α-Synuclein Release in Plasma May be Associated With Postoperative Delirium in Hip Fracture Patients. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2020, 12, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danielson, M.; Wiklund, A.; Granath, F.; Blennow, K.; Mkrtchian, S.; Nellgård, B.; Oras, J.; Jonsson Fagerlund, M.; Granström, A.; Schening, A.; et al. Neuroinflammatory markers associate with cognitive decline after major surgery: Findings of an explorative study. Ann. Neurol. 202; 87, 370–382. [Google Scholar]

- Casey, C.P.; Lindroth, H.; Mohanty, R.; Farahbakhsh, Z.; Ballweg, T.; Twadell, S.; Miller, S.; Krause, B.; Prabhakaran, V.; Blennow, K.; et al. Postoperative delirium is associated with increased plasma neurofilament light. Brain 2020, 143, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavrut Ozturk, N.; Kavakli, A.S.; Arslan, U.; Aykal, G.; Savas, M. [S100B level and cognitive dysfunction after robotic-assisted laparoscopic radical prostatectomy procedures: a prospective observational study]. Braz. J. Anesthesiol. 2020, 70, 573–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ballweg, T.; White, M.; Parker, M.; Casey, C.; Bo, A.; Farahbakhsh, Z.; Kayser, A.; Blair, A.; Lindroth, H.; Pearce, R.A.; et al. Association between plasma tau and postoperative delirium incidence and severity: a prospective observational study. Br. J. Anaesth. 2021, 126, 458–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CheheiliSobbi, S.; Peters van Ton, A.M.; Wesselink, E.M.; Looije, M.F.; Gerretsen, J.; Morshuis, W.J.; Slooter, A.J.C.; Abdo, W.F.; Pickkers, P.; van den Boogaard, M. Case-control study on the interplay between immunoparalysis and delirium after cardiac surger. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2021, 16, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lv, X.C.; Lin, Y.; Wu, Q.S.; Wang, L.; Hou, Y.T.; Dong, Y.; Chen, L.W. Plasma interleukin-6 is a potential predictive biomarker for postoperative delirium among acute type a aortic dissection patients treated with open surgical repair. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2021, 16, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Ji, M.H.; Ding, S.; Wu, Y.; Feng, X.W.; Tao, X.J.; Liu, W.W.; Ma, R.Y.; Wu, F.Q.; Chen, Y.L. Inclusion of interleukin-6 improved performance of postoperative delirium prediction for patients undergoing coronary artery bypass graft (POD-CABG): A derivation and validation study. J. Cardiol. 2022, 79, 634–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, J.; Parker, M.; Casey, C. .P.; Tanabe, S.; Kunkel, D.; Rivera, C.; Zetterberg, H.; Blennow, K.; Pearce, R.A.; Lennertz, R.C.; et al. Postoperative delirium and changes in the blood-brain barrier, neuroinflammation, and cerebrospinal fluid lactate: a prospective cohort study. Br. J. Anaesth. 2022, 129, 219–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.G.; Taylor, J.; Parker, M.; Kunkel, D.; Rivera, C.; Pearce, R.A.; Lennertz, R.; Sanders, R.D. Role of interleukin-18 in postoperative delirium: an exploratory analysis. Br. J. Anaesth. 2022, 128, e229–e231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.H.; Lindroth, H.; Jawed, Y.; Wang, S.; Nasser, J.; Seyffert, S.; Naqvi, K.; Perkins, A.J.; Gao, S.; Kesler, K.; et al. Serum Biomarkers in Postoperative Delirium After Esophagectomy. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2022, 113, 1000–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oren, R.L.; Kim, E.J.; Leonard, A.K.; Rosner, B.; Chibnik, L.B.; Das, S.; Grodstein, F.; Crosby, G.; Culley, D.J. Age-dependent differences and similarities in the plasma proteomic signature of postoperative delirium. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 7431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Hu, J.; Zuo, W.; He, P.; Xue, Q.; Feng, X.; Zhang, Y.; Maze, M. Longitudinal Profiling of Plasma Cytokines and Its Association With Postoperative Delirium in Elderly Patients Undergoing Major Lower Limb Surgery: A Prospective Observational Study. Anesth. Analg. 2023, 136, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, L.J.; Chen, M.J.; Yang, R.; Zou, H.; Chen, T.T.; Li, S.L.; Guo, Y.; Hu, R.F. Plasma biomarkers and delirium in critically ill patients after cardiac surgery: A prospective observational cohort study. Heart Lung 2023, 59, 139–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imai, T.; Morita, S.; Hasegawa, K.; Goto, T.; Katori, Y.; Asada, Y. Postoperative serum interleukin-6 level as a risk factor for development of hyperactive delirium with agitation after head and neck surgery with free tissue transfer reconstruction. Auris Nasus Larynx 2023, 50, 777–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, J.; Wu, J.G.; Kunkel, D.; Parker, M.; Rivera, C.; Casey, C.; Naismith, S.; Teixeira-Pinto, A.; Maze, M.; Pearce, R.A.; et al. Resolution of elevated interleukin-6 after surgery is associated with return of normal cognitive function. Br. J. Anaesth. 2023, 131, 694–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruhnau, J.; Müller, J.; Nowak, S.; Strack, S.; Sperlich, D.; Pohl, A.; Dilz, J.; Saar, A.; Veser, Y.; Behr, F.; et al. Serum Biomarkers of a Pro-Neuroinflammatory State May Define the Pre-Operative Risk for Postoperative Delirium in Spine Surgery. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 10335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lozano-Vicario, L.; Muñoz-Vázquez, Á.J.; Ramírez-Vélez, R.; Galbete-Jiménez, A.; Fernández-Irigoyen, J.; Santamaría, E.; Cedeno-Veloz, B.A.; Zambom-Ferraresi, F.; Van Munster, B.C.; Ortiz-Gómez, J.R.; et al. Association of postoperative delirium with serum and cerebrospinal fluid proteomic profiles: a prospective cohort study in older hip fracture patients. Geroscience 2024, 46, 3235–3247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Tao, X.J.; Ding, S.; Feng, X.M.; Wu, F.Q.; Wu, Y. Associations between postoperative cognitive dysfunction, serum interleukin-6 and postoperative delirium among patients after coronary artery bypass grafting: A mediation analysis. Nurs. Crit. Care 2024, 29, 1245–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, H.; Kayumov, M.; Lee, K.S.; Oh, S.G.; Na, K.J.; Jeong, J.S. Immunological Analysis of Postoperative Delirium after Thoracic Aortic Surgery. J. Chest Surg. 2024, 57, 263–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, C.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, C. The Role of IL-6 in Neurodegenerative Disorders. Neurochem. Res. 2024, 49, 834–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plaschke, K.; Fichtenkamm, P.; Schramm, C.; Hauth, S.; Martin, E.; Verch, M.; Karck, M.; Kopitz, J. Early postoperative delirium after open-heart cardiac surgery is associated with decreased bispectral EEG and increased cortisol and interleukin-6. Intensive Care Med. 2010, 36, 2081–2089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudetz, J.A.; Gandhi, S.D.; Iqbal, Z.; Patterson, K.M.; Pagel, P.S. Elevated postoperative inflammatory biomarkers are associated with short- and medium-term cognitive dysfunction after coronary artery surgery. J. Anesth. 2011, 25, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.C.; Xi, C.H.; An, Y.F.; Dong, W.H.; Zhou, M. Perioperative inflammatory response and protein S-100β concentrations - relationship with post-operative cognitive dysfunction in elderly patients. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2012, 56, 595–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, M.H.; Yuan, H.M.; Zhang, G.F.; Li, X.M.; Dong, L.; Li, W.Y.; Zhou, Z.Q.; Yang, J.J. Changes in plasma and cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers in aged patients with early postoperative cognitive dysfunction following total hip-replacement surgery. J. Anesth. 2013, 27, 236–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, P.; Li, Y.W.; Wang, X.S.; Zou, X.; Zhang, D.Z.; Wang, D.X.; Li, S.Z. High serum interleukin-6 level is associated with increased risk of delirium in elderly patients after noncardiac surgery: a prospective cohort study. Chin. Med. J. 2013, 126, 3621–3627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinsfelt, B.; Westerlind, A.; Blennow, K.; Zetterberg, H.; Ricksten, S.E. Open-heart surgery increases cerebrospinal fluid levels of Alzheimer-associated amyloid β. Acta Anaesthesiol. Scand. 2013, 57, 82–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westhoff, D.; Witlox, J.; Koenderman, L.; Kalisvaart, K.J.; de Jonghe, J.F.; van Stijn, M.F.; Houdijk, A.P.; Hoogland, I.C.; Maclullich, A.M.; van Westerloo, D.J.; et al. Preoperative cerebrospinal fluid cytokine levels and the risk of postoperative delirium in elderly hip fracture patients. J Neuroinflammation 2013, 10, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mrak, R.E.; Griffin, W.S. Interleukin-1, neuroinflammation, and Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol. Aging, 200; 22, 903–908. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez Caldito, N. Role of tumor necrosis factor-alpha in the central nervous system: a focus on autoimmune disorders. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1213448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paudel, Y.N.; Shaikh, M.F.; Chakraborti, A.; Kumari, Y.; Aledo-Serrano, Á.; Aleksovska, K.; Alvim, M.K.M.; Othman, I. HMGB1: A Common Biomarker and Potential Target for TBI, Neuroinflammation, Epilepsy, and Cognitive Dysfunction. Front. Neurosci. 2018, 12, 628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yang, W.; Xue, J.; Chen, J.; Liu, S.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, X.; Gu, X.; Dong, Y.; Qiu, P. Neuroinflammation: The central enabler of postoperative cognitive dysfunction. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023, 167, 115582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirsch, J.; Vacas, S.; Terrando, N.; Yuan, M.; Sands, L.P.; Kramer, J.; Bozic, K.; Maze, M.M.; Leung, J.M. Perioperative cerebrospinal fluid and plasma inflammatory markers after orthopedic surgery. J. Neuroinflammation 2016, 13, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westhoff, D.; Witlox, J.; Koenderman, L.; Kalisvaart, K.J.; de Jonghe, J.F.; van Stijn, M.F.; Houdijk, A.P.; Hoogland, I.C.; Maclullich, A.M.; van Westerloo, D.J.; et al. Preoperative cerebrospinal fluid cytokine levels and the risk of postoperative delirium in elderly hip fracture patients. J Neuroinflammation 2013, 10, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gayger-Dias, V.; Vizuete, A.F.; Rodrigues, L.; Wartchow, K.M.; Bobermin, L.; Leite, M.C.; Quincozes-Santos, A.; Kleindienst, A.; Gonçalves, C.A. How S100B crosses brain barriers and why it is considered a peripheral marker of brain injury. Exp. Biol. Med. (Maywood), 202; 248, 2109–2119. [Google Scholar]

- Dominguini, D.; Steckert, A.V.; Michels, M.; Spies, M.B.; Ritter, C.; Barichello, T.; Thompson, J.; Dal-Pizzol, F. The effects of anaesthetics and sedatives on brain inflammation. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2021, 127, 504–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rump, K.; Adamzik, M. Epigenetic Mechanisms of Postoperative Cognitive Impairment Induced by Anesthesia and Neuroinflammation. Cells 2022, 11, 2954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lili, X.; Zhiyong, H.; Jianjun, S. A preliminary study of the effects of ulinastatin on early postoperative cognition function in patients undergoing abdominal surgery. Neurosci. Lett. 2013, 541, 15–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jildenstål, P.K.; Hallén, J.L.; Rawal, N.; Berggren, L.; Jakobsson, J.G. AAI-guided anaesthesia is associated with lower incidence of 24-h MMSE < 25 and may impact the IL-6 response. Int. J. Surg. 2014, 12, 290–295. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; He, R.; Chen, S.; Qu, Y. Effect of dexmedetomidine on early postoperative cognitive dysfunction and peri-operative inflammation in elderly patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Exp. Ther. Med. 2015, 10, 1635–1642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Y.; Jin, G.; Guo, S.; Gu, B.; Jin, Z.; Gao, X.; Li, Z. Fast-track surgery decreases the incidence of postoperative delirium and other complications in elderly patients with colorectal carcinoma. Langenbecks. Arch. Surg. 2014, 399, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Wei, P.; Zheng, Q.; Zhou, J.; Li, J. Neuroprotective effects of intravenous lidocaine on early postoperative cognitive dysfunction in elderly patients following spine surgery. Med. Sci. Monit. 2015, 21, 1402–1407. [Google Scholar]

- Qiao, Y.; Feng, H.; Zhao, T.; Yan, H.; Zhang, H.; Zhao, X. Postoperative cognitive dysfunction after inhalational anesthesia in elderly patients undergoing major surgery: the influence of anesthetic technique, cerebral injury and systemic inflammation. BMC Anesthesiol. 2015, 15, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Liu, B.; Zhang, F.; Xue, P.; Cui, R.; Lei, W. The effects of dexmedetomidine on post-operative cognitive dysfunction and inflammatory factors in senile patients. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Med. 2015, 8, 4601–4605. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, K.Y.; Yang, Q.Y.; Tang, P.; Li, H.X.; Zhao, H.W.; Ren, X.B. Effects of ulinastatin on early postoperative cognitive function after one-lung ventilation surgery in elderly patients receiving neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Metab. Brain Dis. 2017, 32, 427–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xin, X.; Xin, F.; Chen, X.; Zhang, Q.; Li, Y.; Huo, S.; Chang, C.; Wang, Q. Hypertonic saline for prevention of delirium in geriatric patients who underwent hip surgery. J. Neuroinflammation 2017, 14, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, Z.; Xu, N.; Qi, S. Remote ischemic preconditioning improves the cognitive function of elderly patients following colon surgery: A randomized clinical trial. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017, 96, e6719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, X.Y.; Chen, M.; Chen, D.H.; Li, Y.; Liu, P.T.; Liu, Y. Remifentanil on T lymphocytes, cognitive function and inflammatory cytokines of patients undergoing radical surgery for cervical cancer. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2018, 22, 2854–2859. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Wu, Z.; Zhao, X.; Qiao, Y. Role of dexmedetomidine in reducing the incidence of postoperative cognitive dysfunction caused by sevoflurane inhalation anesthesia in elderly patients with esophageal carcinoma. J. Cancer Res. Ther. 2018, 14, 1497–1502. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, C.; Lee, C.H.; Lee, G.; Lee, M.; Hwang, J. The effect of the timing and dose of dexmedetomidine on postoperative delirium in elderly patients after laparoscopic major non-cardiac surgery: A double blind randomized controlled study. J. Clin. Anesth. 2018, 47, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, C.; Chen, J.; Luo, Y.; Zhou, L.; He, X.; Liao, Y.; Chou, J.; Guo, Q.; Chen, A.F.; Wen, O. BIS-guided deep anesthesia decreases short-term postoperative cognitive dysfunction and peripheral inflammation in elderly patients undergoing abdominal surgery. Brain Behav. 2019, 9, e01238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.A.; Ahn, H.J.; Yang, M.; Lee, S.H.; Jeong, H.; Seong, B.G. Intraoperative use of dexmedetomidine for the prevention of emergence agitation and postoperative delirium in thoracic surgery: a randomized-controlled trial. Can. J. Anaesth. 2019, 66, 371–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Cheng, J.; Yang, L.; Wang, J.; Liu, H.; Lv, Z. Ropivacaine for Intercostal Nerve Block Improves Early Postoperative Cognitive Dysfunction in Patients Following Thoracotomy for Esophageal Cancer. Med. Sci. Monit. 2019, 25, 460–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, W.F.; Tawfik, M.H.; Nabil, T.M.; Abd Elkareem, R.M. Could intraoperative magnesium sulphate protect against postoperative cognitive dysfunction? Minerva Anestesiol. 2020, 86, 808–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, X.; Chen, J.; Hua, W.; Wang, H. Intraoperative dexmedetomidine for prevention of postoperative delirium in elderly patients with mild cognitive impairment. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2021, 36, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mei, B.; Xu, G.; Han, W.; Lu, X.; Liu, R.; Cheng, X.; Chen, S.; Gu, E.; Liu, X.; Zhang, Y. The Benefit of Dexmedetomidine on Postoperative Cognitive Function Is Unrelated to the Modulation on Peripheral Inflammation: A Single-center, Prospective, Randomized Study. Clin. J. Pain 2020, 36, 88–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uysal, A.İ.; Altıparmak, B.; Yaşar, E.; Turan, M.; Canbek, U.; Yılmaz, N.; Gümüş Demirbilek, S. The effects of early femoral nerve block intervention on preoperative pain management and incidence of postoperative delirium geriatric patients undergoing trochanteric femur fracture surgery: A randomized controlled trial. Ulus. Travma. Acil. Cerrahi. Derg 2020, 26, 109–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Zhu, L.; Li, Y.; Yin, C.; Hou, Z.; Wang, Q. The Potential Role of Lung-Protective Ventilation in Preventing Postoperative Delirium in Elderly Patients Undergoing Prone Spinal Surgery: A Preliminary Study. Med. Sci. Monit. 2020, 26, e926526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Zhu, M.; Gao, Z.; Zhao, S.; Feng, X.; Chen, J.; Zhang, Y.; Maze, M. Dexmedetomidine for prevention of postoperative delirium in older adults undergoing oesophagectomy with total intravenous anaesthesia: A double-blind, randomised clinical trial. Eur. J. Anaesthesiol. 2021, 38, 296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, C.S.; Lim, H.Y.; Jeon, H.J.; Kim, T.H.; Park, H.J.; Piao, L.; Kim, S.H. Effect of deep neuromuscular blockade on serum cytokines and postoperative delirium in elderly patients undergoing total hip replacement: A prospective single-blind randomised controlled trial. Eur. J. Anaesthesiol. 2021, 38, S58–S66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, P.; Li, M.J.; Mao, A.Q.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, Y. Effects of General Anesthesia Combined with Epidural Anesthesia on Cognitive Dysfunction and Inflammatory Markers of Patients after Surgery for Esophageal Cancer: A Randomised Controlled Trial. J. Coll. Physicians Surg. Pak. 2021, 31, 885–890. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Chen, D.; Wang, H.; Wang, Z.; Song, F.; Li, H.; Ling, L.; Shen, Z.; Hu, C.; Peng, J.; et al. Intravenous versus Volatile Anesthetic Effects on Postoperative Cognition in Elderly Patients Undergoing Laparoscopic Abdominal Surgery. Anesthesiology 2021, 134, 381–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Li, W.; Jia, H. Postoperative Effects of Dexmedetomidine on Serum Inflammatory Factors and Cognitive Malfunctioning in Patients with General Anesthesia. J. Healthc Eng. 2021, 2021, 7161901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.; Li, Q.; Qin, F.; Yuan, L.; Lu, Z.; Nie, H.; Gong, G. Repeated Preoperative Intranasal Administration of Insulin Decreases the Incidence of Postoperative Delirium in Elderly Patients Undergoing Laparoscopic Radical Gastrointestinal Surgery: A Randomized, Placebo-Controlled, Double-Blinded Clinical Study. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2021, 29, 1202–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, T.; Zhao, J.; Wang, J.; Sun, X.; Jia, T.; Li, F. Anesthetic Effect of the Fascia Iliaca Compartment Block with Different Approaches on Total Hip Arthroplasty and Its Effect on Postoperative Cognitive Dysfunction and Inflammation. Front. Surg. 2022, 9, 898243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, Y. Effect of transverse thoracic muscle plane block on postoperative cognitive dysfunction after open cardiac surgery: A randomized clinical trial. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2023, 27, 976–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.; Ma, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wang, P.; Liu, Y. Effects of Dexmedetomidine Anesthesia on Early Postoperative Cognitive Dysfunction in Elderly Patients. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2022, 13, 2309–2314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.Y.; Li, M.; Wang, P.; Fang, P. Goal-directed therapy based on rScO2 monitoring in elderly patients with one-lung ventilation: a randomized trial on perioperative inflammation and postoperative delirium. Trials 2022, 23, 687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Kong, G.; Zhao, Y.; Wei, L.; Liu, J. Prevention of dexmedetomidine on postoperative delirium and early postoperative cognitive dysfunction in elderly patients undergoing hepatic lobectomy. Zhong Nan Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban 2022, 47, 219–225. [Google Scholar]

- Xiang, X.B.; Chen, H.; Wu, Y.L.; Wang, K.N.; Yue, X.; Cheng, X.Q. The Effect of Preoperative Methylprednisolone on Postoperative Delirium in Older Patients Undergoing Gastrointestinal Surgery: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial. J. Gerontol. A. Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2022, 77, 517–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurup, M.T.; Sarkar, S.; Verma, R.; Bhatia, R.; Khanna, P.; Maitra, S.; Anand, R.; Ray, B.R.; Singh, A.K.; Deepak, K.K. Comparative evaluation of intraoperative dexmedetomidine versus lidocaine for reducing postoperative cognitive decline in the elderly: a prospective randomized controlled trial. Anaesthesiol. Intensive Ther. 2023, 55, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, Y.; Chen, Q.; Xiang, C.; Li, G.; Wei, K. Comparison of the Effects of Dexmedetomidine and Lidocaine on Stress Response and Postoperative Delirium of Older Patients Undergoing Thoracoscopic Surgery: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Clin. Interv. Aging 2023, 18, 1275–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, F.; Li, Y.; Wang, X.; Sun, R.; Zheng, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Gao, M.; Tao, W.; Zhao, J.; Wang, Q. Effect of pre-infusion of hypertonic saline on postoperative delirium in geriatric patients undergoing shoulder arthroscopy: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Anesthesiol. 2023, 23, 405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, C.; Ji, H.; Guo, Y.; Fei, Y.; Wang, C.; Yuan, Y.; Ruan, Z.; Ma, T. Effect of Subanesthetic Dose of Esketamine on Perioperative Neurocognitive Disorders in Elderly Undergoing Gastrointestinal Surgery: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Drug Des. Devel. Ther. 2023, 17, 863–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M.; Mei, Y.; Zhou, R.; Wang, L.; Zhang, X. Effects of anterior approach to quadratus lumborum block on postoperative cognitive function following hip surgery in older people: a randomized controlled clinical trial. BMC Geriatr. 2023, 23, 835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhi, Y.; Li, W. Effects of total intravenous anesthesia with etomidate and propofol on postoperative cognitive dysfunction. Physiol. Res. 2023, 72, 251–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mi, Y.; Wen, O.; Ge, L.; Xing, L.; Jianbin, T.; Yongzhong, T.; Xi, H. Protective effect of intranasal insulin on postoperative cognitive dysfunction in elderly patients with metabolic syndrome undergoing noncardiac surgery: a randomized clinical trial. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2023, 35, 3167–3178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, M.; Ruan, X.; Zhou, Z.; Huo, Y.; Liu, M.; Liu, S.; Cao, J.; Liu, Y.H.; Zhang, X.; Ma, Y.L.; et al. Effect of intranasal insulin on perioperative cognitive function in older adults: a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind clinical trial. Age Ageing 2024, 53, afae188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, W.; Xu, H.; Zhao, T.; Xu, J.; Wang, F. Effects of dexmedetomidine combined with etomidate on postoperative cognitive function in older patients undergoing total intravenous anaesthesia: a randomized, double-blind, controlled trial. BMC Geriatr. 2024, 24, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, T.; Deng, Z.; Ren, Q.; Mu, F.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, H. Effects of esketamine on postoperative negative emotions and early cognitive disorders in patients undergoing non-cardiac thoracic surgery: A randomized controlled trial. J. Clin. Anesth. 2024, 95, 111447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsiung, P.Y.; Shih, P.Y.; Wu, Y.L.; Chen, H.T.; Hsu, H.H.; Lin, M.W.; Cheng, Y.J.; Wu, C.Y. Effects of nonintubated thoracoscopic surgery on postoperative neurocognitive function: a randomized controlled trial. Eur. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2024, 65, ezad434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, W.Y.; Peng, T.; Guo, B.C.; Fan, C.C.; Xu, J.; Liu, X.M.; Li, X. Effects of parecoxib on postoperative cognitive dysfunction and serum levels of NSE and S100β in elderly patients undergoing surgery. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol Sci. 2024, 28, 278–287. [Google Scholar]

- Huo, Q.F.; Zhu, L.J.; Guo, J.W.; Jiang, Y.A.; Zhao, J. Effects of ulinastatin combined with dexmedetomidine on cognitive dysfunction and emergence agitation in elderly patients who underwent total hip arthroplasty. World, J. Psychiatry 02024, 14, 26–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hindman, B.J.; Olinger, C.R.; Woodroffe, R.W.; Zanaty, M.; Streese, C.; Zacharias, Z.R.; Houtman, J.C.D.; Wendt, L.H.; Eyck, P.P.T.; O'Connell-Moore, D.J.; et al. Exploratory Randomised Trial of Tranexamic Acid to Decrease Postoperative Delirium in Adults Undergoing Lumbar Fusion: A trial stopped early. medRxiv. 2024, 2024, 24315638. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, C.; Shen, J.; Zhang, C.; Hu, C. Impact of intraoperative dexmedetomidine on postoperative delirium and pro-inflammatory cytokine levels in elderly patients undergoing thoracolumbar compression fracture surgery: A prospective, randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Medicine (Baltimore) 02024, 103, e37931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, X.; Zhao, X.; Guo, R.; Hu, Z.; Liu, J.; Nie, H. Value of narcotrend anesthesia depth monitoring in predicting POCD in gastrointestinal tumor anesthesia block patients. BMC Anesthesiol. 2024, 24, 371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grosu, I.; Lavand'homme, P. Continuous regional anesthesia and inflammation: a new target. Minerva Anestesiol. 2015, 81, 1001–1009. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Liaquat, Z.; Xu, X.; Zilundu, P.L.M.; Fu, R.; Zhou, L. The Current Role of Dexmedetomidine as Neuroprotective Agent: An Updated Review. Brain Sci. 2021, 11, 846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, A.; Hana, Z.; Jin, Z.; Suen, K.C.; Ma, D. Surgery, neuroinflammation and cognitive impairment. EBioMedicine 2018, 37, 547–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).