1. Introduction

Climate change, urbanization, fossil fuel energy consumption, and other factors, have exacerbated air pollution and related public health issues [

1]. Effective Air Quality (AQ) monitoring is vital for safeguarding public health, especially in densely populated urban areas where pollution levels are often higher. Traditional high-cost, high-maintenance AQ monitoring systems, while accurate, are often limited in geographic coverage and flexibility, making comprehensive AQ monitoring and surveillance challenging. Recent advancements in sensor technology and manufacturing have seen the rise of low-cost sensors (LCS) which offer broader geographic coverage.

The advent of LCS presents a transformative challenge and opportunity to enhance AQ monitoring. Purple Air (PA) sensors, one type of low-cost sensors, have gained prominence due to their affordability, ease of deployment, and timely readings [

2]. However, the practical utilization of these sensors is significantly compromised by their low accuracy and reliability under different environmental and manmade conditions [

3] and they often require calibration to match the accuracy of traditional systems [

4].

PA sensors measure particulate matter (PM) in three size ranges: PM

1.0 (particles with a diameter of less than 1.0 micrometers), PM

2.5 (less than 2.5 micrometers) and PM

10 (less than 10 micrometers). They also record environmental variables such as temperature, humidity, and pressure. For this study, we focus on PM

2.5, particulate matter with a diameter of less than 2.5 micrometers, which can penetrate deep into the respiratory tract and enter the bloodstream causing health risks, including respiratory, cardiovascular, and neurological diseases [

5]. However, the AI/ML approach will not be applicable in instances where particle sizes are smaller than 300nm, as this is a physical limitation of existing sensor technologies. Monitoring PM

2.5 is necessary for assessing exposure and implementing strategies to mitigate public health impacts. Large amounts of PA data are available, and previous studies have proved the potential of machine learning (ML) approaches to improve accuracy [

6]. Calibration is one of the first been investigated by using AI/ML to correct inherent sensor biases and ensure the comparability of data across different sensors and environments. However, the challenge with PM

2.5 calibration lies in its sensitivity to ambient environmental changes, such as relative humidity and temperature, which can negatively impact sensor performance and accuracy [

7]. Although previous studies such as [

8] have explored ML models for sensor calibration, none have yet provided a comprehensive comparison across as many models and environment variables as this study proposes, nor have they covered entire sensor networks over a large geographic area.

In this study, finetuning refers to the process of making adjustments to ensure correct readings from the devices, while calibration is defined as the preliminary step of establishing the relationship between the measured value and the device's indicated value. Calibration is a preliminary step before tuning. Although we focus on the finetuning to achieve accurate PM2.5 measurements, we refer to this process as calibration in alignment with the existing literature.

In general, this study seeks to bridge the gap between the affordability of LCS and the precision required for scientific and regulatory purposes. Our objective is to systematically evaluate AI/ML models and software packages to identify the most effective model and software package for improving the accuracy of low-cost sensor (LCS) measurements. Each of the AI/ML models is tested to identify the optimal model and package. 64 pairs of Purple Air (LCS) and EPA sensors are used in this study with the well validated EPA measurements as ground truth. Elevenregression models were systematically considered across four Python-based software packages: XGBoost, Scikit-learn, TensorFlow, and PyTorch, as well as a fifth R based IDE, RStudio. The models in this study include Decision Tree Regressor (DTR), Random Forest (RF), K-Nearest Neighbors, XGBRegressor, Support Vector Regression (SVR), Simple Neural Network (SNN), Deep Neural Network (DNN), Long Short-Term Memory neural network (LSTM), Recurrent Neural Networks (RNN), Ordinary Least Square Regression (OLS), and Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator (Lasso) regression [

48,

49,

50,

51,

52,

53,

54,

55,

56,

57,

58,

59,

60,

61,

62,

63]. The details are provided in the following 5 sections:

Section 2 reviews existing calibration methods conducted in both traditional calibration techniques (field and laboratory methods) and recent advancements involving empirical and geophysical ML models.

Section 3 introduces study area, data, and pre-processing for PA sensors.

Section 4 reports experimental results.

Section 5 presented the results and

Section 6 discusses the reason for model performance difference, comparison to existing studies, limitation and future research.

2. Literature Review

2.1. AQ Calibration

AQ calibration has advanced in recent years to address inherent biases and uncertainties from electronics, installation and configurations, which serves as a crucial process to align readings with established reference standards and uphold data validity [

9]. Several calibration methods stand out for their efficacy and application diversity: Field calibration, which involves the direct comparison of sensor data with reference-grade instruments in the environment, is used to ensure in-situ sensor accuracy [

10]. Additionally, laboratory calibration techniques, which subject sensors to controlled conditions and known concentrations of pollutants, allow the meticulous adjustment of sensor responses before their deployment in the field [

11], [

12]. Calibration techniques also vary by pollutants and sensors. Metal Oxide Semiconductor (MOS) sensors, used for detecting NO₂ (nitrogen dioxide), O₃ (ozone), SO₂ (sulfur dioxide), CO (carbon monoxide), and CO₂ (carbon dioxide), undergo calibration to correlate electrical conductivity changes with specific target gas concentrations, ensuring accurate readings [

13]. Electrochemical (EC) sensors for CO, NO

2, and SO

2 monitoring undergo calibration via controlled oxidation-reduction reactions, linking measured currents to gas concentrations for accurate field readings [

14]. Non-Dispersive Infrared (NDIR) sensors for CO

2 measurement require calibration that accounts for spectral variations. This involves exposing the sensor to a range of CO

2 concentrations and analyzing infrared light absorption patterns to ensure accurate CO

2 detection [

15]. Satellite sensors were introduced to extend AQ observations to a regional and global scale and relevant calibration methods were developed for such as post-launch atmospheric effects calibration [

16,

17,

18].

Calibrating AQ sensors is essential to maintaining data integrity, particularly when reconciling the lower precision of emerging LCS with the established accuracy of reference-grade instruments. While field calibration directly aligns sensors to real-world conditions, laboratory techniques refine sensor accuracy under controlled parameters. Despite these advances, the challenge remains to develop calibration methodologies that can navigate the complex interplay of sensor responses with dynamic environmental factors—a focus area that warrants a systematic investigation to enhance AQ monitoring frameworks.

2.2. Calibration of LCSs for PM Measurement

LCS are revolutionizing AQ monitoring by making it more accessible and participatory [

19] especially for under-served communities to collect vital PM data [

20]. This grassroots approach offers a richer, more localized view of AQ than is possible with sparser, traditional monitoring networks [

21]. However, the accuracy of LCSs is low due to various factors, including environmental influences [

22], [

23] and inherent limitations of the sensors themselves [

24].

Most LCS uses light scattering to count particle numbers [

25] which is sensitive to fluctuations in temperature, pressure, and humidity [

26,

27]. Although many LCSs come with built-in mechanisms to track environmental factors and are encased in protective shells to lessen weather impacts, data accuracy are still significantly compromised under extreme weather conditions [

28]. Moreover, different LCS types and their corresponding data interpretation models introduce biases related to the sensor's location, varying humidity levels, and the hygroscopic growth of aerosol particles [

29]. For example, at relative humidity (RH) levels below 100%, hygroscopic PM

2.5 particles, such as sodium chloride (NaCl), can absorb moisture from the air, leading to an increase in particle size and a change in their optical properties. These alterations can significantly affect the light scattering process, which is central to the operation of LCS [

29,

30,

31].

These investigations emphasize the rigorous calibration and correction methods to counteract the influence of environmental and other factors, thereby enhancing data reliability in diverse environmental conditions [

12,

26,

32]. While field calibration is essential for aligning LCS readings with standard measurements—requiring placement alongside reference monitors for measurement refinement [

19], [

31] —the development and application of robust and well performed calibration models are paramount. Such models, when implemented across the sensor network, significantly enhance data consistency and reliability, thereby augmenting the overall efficacy of AQ monitoring efforts.

2.3. Models to Calibrate LCS

There are two types of models for calibrating LCS data to enhance accuracy in AQ monitoring—physics-based models and empirical models. The physics-based model employs fundamental physical principles, such as the κ-Köhler theory and Mie theory, to accurately correlate the sensor's light scattering measurements [

33]. For example, [

34] applies κ-Köhler and Mie theories to a low-cost PM sensor, significantly enhancing the accuracy with coefficient of determination (R²) values up to 0.91, and exhibited lower Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) and Mean Absolute Error (MAE) values. [

35] showcased a physics-based calibration approach for PA sensors, which, when aligned with Beta Attenuation Monitor (BAM) standards, exhibit high consistency with correlation above 0.9, alongside a MAE of 3–4 µg/m³.

Empirical models leverage the availability of large amount observed data to establish a statistical relationship between sensor readings and reference measurements, often incorporating environmental variables to enhance the accuracy and reliability of LCS [

36], [

19]. The empirical calibration models commonly assume a correlation between the data from LCS and high-quality reference-grade measurements. For example, [

24] reported a linear calibration model for PM

2.5, evidencing an enhanced fit with an R

2 of 0.86 under dry conditions and 0.75 under humid conditions when compared to reference measurements. Research [

37], [

38], and [

9] emphasize the importance of including environmental variables, notably relative humidity, which affects particle count and sensor outputs. To address these challenges, non-linear and ML models have been utilized for better alignment with high-quality reference instruments [

39,

40].

Given the critical role of environmental variables, it is important to consider the strong correlation between RH and temperature, which can significantly influence the development of calibration models by introducing multicollinearity, potentially leading to biased predictions [

23]. In linear models, for instance, collinearity can distort regression coefficients, making it difficult to assess the true impact of each variable [

68]. Modern machine learning (ML) models, such as random forests, address this by incorporating the interrelationships between these variables into their algorithms, allowing them to account for correlations when determining variable importance [

69].

Current literature presents a wealth of individual cases examining the calibration of LCS with quite limited settings, e.g., limited # of sensors and input values. It is also found that there is no collective, comparative, and systematic study that encompasses diverse calibration models and software packages. This gap is critical because PM2.5 measurements from LCSs can vary significantly due to inherent differences in sensing technology, geographical regions, and environmental conditions. Without a systematic approach considering these factors, calibrations may not effectively address these variations, leading to inaccurate data and hindering our ability to fully understand AQ variations. Therefore, our objective is to conduct an in-depth systematic study of AI/ML models and packages for identifying the most accurate combinations as to help us improve the accuracy of LCS measurements using AI/ML approaches. We utilized the 5 popular software packages and 11 ML models, mentioned at the end of section 1, to conduct an in-depth, systematic analysis for a more detailed and nuanced understanding of LCSs behaviors and their alignment with standard observations.

3. Data and Methodology

3.1. Training Data Preparation

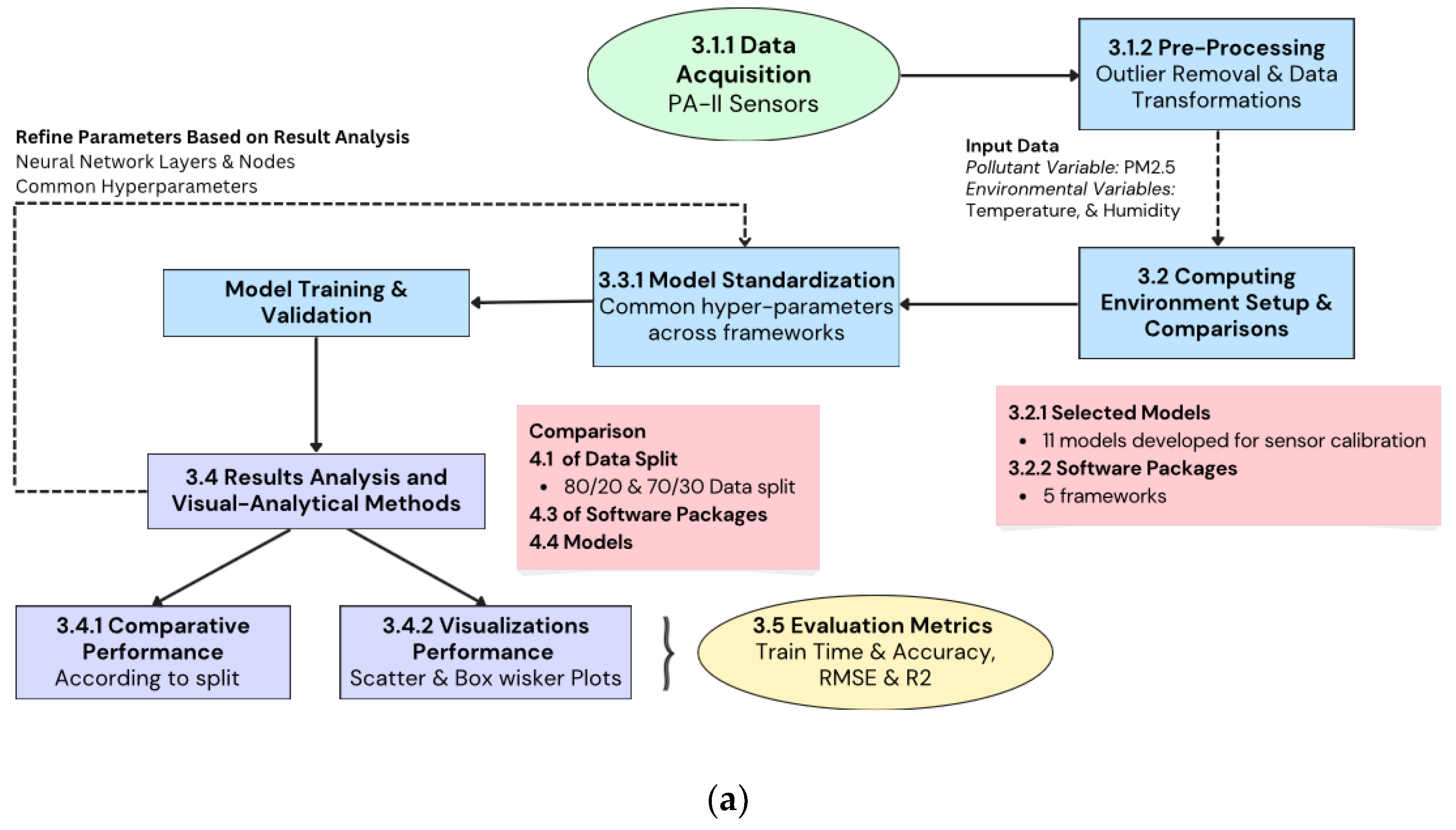

Figure 1 illustrates the detailed workflow of our study, starting from data acquisition and pre-processing, through model standardization and training, to results analysis and visualization. After step 3.4, where metrics are produced by the different software packages across computing environments, visualizations are produced using RStudio’s ggplot2 library. These visualizations enable a thorough comparative performance analysis according to different splits, software packages, and models.

3.1.1. Data Acquisition

We downloaded the PA-II sensor data (PMS-5003) and relevant pressure, temperature, and humidity (AQMD, 2016). Data is kept on two database tables: a sensor table and a reading table. We also utilized data from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) as a benchmark to ensure the accuracy and reliability of our study [

70]. EPA sensors utilize Federal Reference Methods (FRMs) and Federal Equivalent Methods (FEMs) [

70] to ensure accurate and reliable measurements of PM. These methods involve stringent quality assurance and control (QA/QC) protocols, gravimetric analysis, regular calibration, and strict adherence to regulatory standards. The EPA’s monitoring stations continuously collect data which undergoes rigorous validation before being used to determine compliance with National Ambient Air Quality Standards (NAAQS) [

71]. Given these processes, EPA data is often considered the gold standard, making it an essential reference for comparing non-regulated sensors.

Data is kept on two database tables: a sensor table and a reading table. The sensor table includes metadata including hardware component information, unique sensor ID, geographic location, and indoor/outdoor placement. The reading table stores continuous time series data for each sensor, with sensor ID as primary keys to link the records in both tables. The date attribute is set in UTC for all measurements including pollutant and environmental variables. The table includes two types of PM variables, ATM (where Calibration Factor = Atmosphere) and CF_1 (where Calibration Factor = 1), for three target pollutants: PM

1.0, PM

2.5, and PM

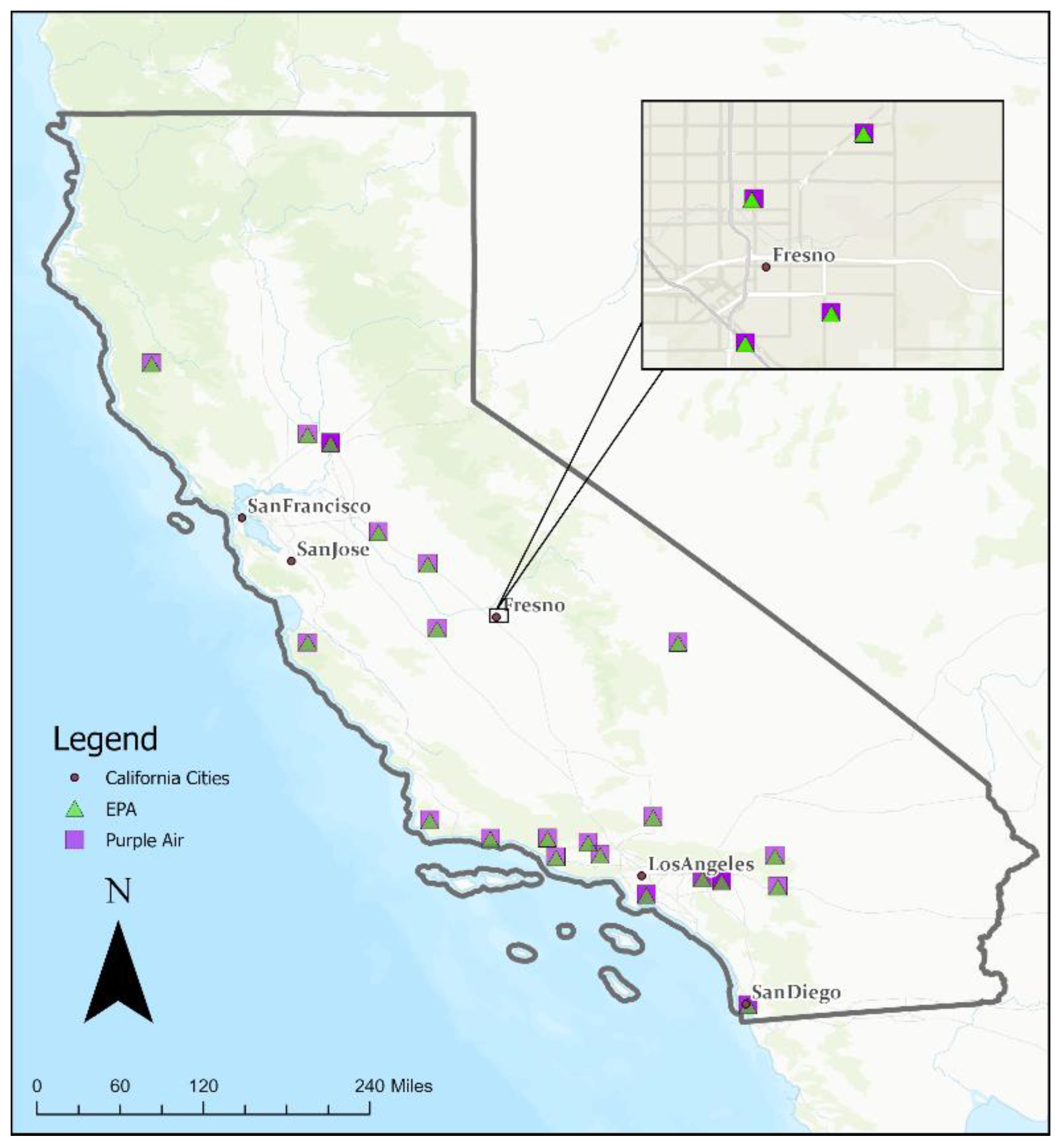

10. CF_1 uses the “average particle density” for indoor PM and CF_ATM uses the “average particle density” for outdoor PM. The PA sensors utilized in this study were outdoor sensors. We identified 64 sensor pairs across California for a total of 876,831 data entries from July 10th, 2017, to September 1st, 2022 (

Figure 2). These 64 sensor pairs consisted of 64 unique PA sensors and 25 unique EPA sensors; these sensors are paired based off their proximity to one another. Each pair of these sensors are mostly within 10 meters of one another, and the furthest distance is below 100 meters.

3.1.2. Pre-Processing

The data preprocessing utilizes a threshold of >0.7 Pearson correlation coefficient between “epa_pm25” and “pm25_cf_1” to ensure a strong linear relationship. Next, data is aggregated from two-minute temporal resolution into an hourly resolution and adjusted for local time zones. Sensor malfunctions such as readings exceeding 500 are removed, as are data records with missing information from either the “pm25_cf_1_a” or “pm25_cf_1_b” columns. Additionally, readings with a zero 5-hour moving standard deviation in either channel were removed as this could mean potential sensor issues. Finally, we applied a dual-channel agreement criterion grouped by year and month. The data is then reduced to the following columns: “datetime”, “pm25_cf_1”, “humidity”, and “temperature”, which compose the training data.

For the LSTM and RNN models, we created sequences using the previous 23 hours of data for each sensor. For all models we then split the data into training and testing and scaled using a standard scaler in random fashion.

3.2. Computing Environmental Setup and Comparisons

For this study, we tested 11 ML models across 5 different packages, Scikit (1.3.2), XGBoost (2.0.2), Pytorch (1.13.1), TensorFlow (2.13), and RStudio (2023.09.1 running R4.3.2). These packages were chosen for their respective strengths and popularity in the academic community. We utilized the same training data, models across each package and model, all on a consistent machine configuration featuring Microsoft Windows 11 Enterprise OS, a 13th gen Intel(R) Core(TM) i7-13700 at 2100 MHz, 16 cores, 24 logical processors, and 32 GB of RAM. After a thorough analysis and literature review of models supported by each package, we selected 11 AI/ML models suitable for the calibration task (

Table 1).

3.2.1. Selected Models

The 11 regression and ML models that support calibration requires two types of independent and target variables represented by X and Y respectively with the goal to map a function such that y=f(x_n )+ε, where ε is degree of error, and x_n encapsulates more than one independent variable (e.g., temperature and relative humidity). The strong correlation between temperature and relative humidity can introduce multicollinearity into the model, which may complicate the estimation of the individual effects of these variables on the target outcome. In traditional regression models, this multicollinearity can lead to inflated variance of the coefficient estimates, potentially resulting in less reliable predictions. However, in the context of the 11 ML models, they are designed to handle such correlations more robustly, either by regularization techniques, e.g., Lasso regression, or by leveraging the complex interrelationships among the variables, e.g., RF, XGBoost, thus minimizing the adverse effects of multicollinearity on the calibration process. We apply regression algorithms to develop similar functions that describe the impact of the input variables (measurements) from in-situ PA Sensors against the measurements aligning with EPA readings as described below.

Decision Tree Regressor (DTR) predicts the target value by learning simple decision rules inferred from the training data [

48]. It splits the training data into increasingly specific subsets based on feature thresholds, with each leaf node in the tree providing a prediction that represents the mean of the values in that segment.

Random Forest (RF) is an ensemble learning model that builds multiple decision trees during training and outputs the average prediction of the individual trees [

49]. It improves model accuracy and overcomes the overfitting problem of single trees by averaging outputs from multiple deep decision trees, each trained on a random subset of features and samples.

K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN) is a non-parametric model used for regression and classification problems [

50]. The output is calculated as the average of the values of its k nearest neighbors. KNN works by finding the k closest training examples in the feature space and averaging their values for prediction.

XGBRegressor is part of the XGBoost package with a highly efficient and scalable implementation of a gradient boosting framework [

51]. This model uses a series of decision trees, where each tree corrects errors made by the previous ones, and it includes regularization terms to prevent overfitting.

Support Vector Regression (SVR) is an extension of the Support Vector Machine (SVM) [

52]. SVR tries to fit the error within a certain threshold and is robust against outliers. It uses kernel functions to handle non-linear relationships.

Where w is the weight vector, φ(a) is the feature function representing the input variables, and (w* φ(a)) is the dot product targeting the prediction results.

Simple Neural Network (SNN) is often a single-layer network with direct connections between inputs and outputs [

53]. It can model relationships in data by adjusting the weights of these connections, typically using methods like backpropagation.

Deep Neural Network (DNN) composes multiple layers between the input and output layers (known here as hidden layers), which enable the modeling of complex patterns with large datasets [

54]. Each layer transforms its input data into a slightly more abstract and composite representation. Further experimentation is needed to identify the balanced layer number and overfitting for the specific use case of sensor calibration.

-

Recurrent Neural Network (RNN) is a class of neural networks where the node connections form a directed graph along a temporal sequence to exhibit dynamic temporal behavior and process sequences of inputs, making it suitable for tasks like time series forecasting [

55].

One setup equation for RNN is:

Where

is the input data point (scalar/real valued vector) at time step t for the i(th) training/test example,

is the target (scalar/real valued vector) at time step t for the i(th) training/test sample,

is the predicted output (scalar/real valued vector) at time step t for the i(th) training/test example,

is the hidden state (real valued vector) at time step t for the i(th) training/test example, and

are the weight matrices associated with the input, output, and hidden states respectively. In this study,

pertains to the input PM

2.5, relative humidity, and temperature data points at a certain time t.

-

Long Short-Term Memory Neural Network (LSTM) is a type of RNN that consists of three gates in its memory cell: the forget gate, the input gate (the PM

2.5, temperature, and relative humidity), and the output gate (the calibrated values) [

56].

This is later used to build a LSTM structure,

Where f(t) = forget gate, o = sigmoid, Wf = weight, h(t-1) = output of previous block, Xt = input vector, b(f) = bias. The multiplication is done elementwise, C(t) = cell state, h(t) = hidden state, and O(t) = output gate. The input sequence comprises of the PM2.5, relative humidity, and temperature values at a given time t.

Ordinary Least Square Regression (OLS) is a method for estimating the unknown parameters [

57]. OLS chooses the parameters that minimize the sum of the squared differences between the observed dependent variable and those predicted by the linear function.

Lasso (Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator) Regression is a type of linear regression that uses shrinkage (minimizing coefficients) [

58]. It adds a regularization term to the cost function, which involves the L1 norm of the weights, promoting a sparse model where few weights are non-zero.

3.3. Software Packages

The five packages include:

XGBoost, standing for eXtreme Gradient Boosting, is a highly efficient implementation of gradient boosted decision trees designed for speed and performance [

59]. This standalone library excels in handling various types of predictive modeling tasks including regression, classification, and ranking. XGBoost can be used with several data science environments and programming languages including Python, R, and Julia, among others. XGBoost works well to build hybrid models as it integrates smoothly with both Scikit-Learn and TensorFlow via wrappers that allow its algorithms to be tuned and cross-validated in a consistent matter. It also functions well as a standalone model, using functions like XGBRegressor.

Scikit-Learn is a comprehensive library used extensively for data preparation, model training, and evaluation across a spectrum of ML tasks such as classification, regression, and clustering [

60]. It supports many algorithms included in this study and other advanced regression and AI/ML algorithms. This package excels due to its ease of use, efficiency, and broad applicability in tackling both simple and complex ML problems.

TensorFlow, coupled with its high-level API Keras, provides a robust environment for designing a diverse array of ML models [

61]. It is particularly effective for developing neural network models such as the ones employed in this study. TensorFlow uses 'tf.keras’ to implement regression models. RF and Lasso are built with extensions like TensorFlow Decision Forests (TF-DF) demonstrating its versatility across both deep learning and traditional ML domains.

PyTorch, known for its flexibility and powerful GPU acceleration, is used in the development of DL models [

62]. While it is not traditionally used for simple regression models, it is ideal for constructing complex neural network models. For some Regression modelling, external packages or custom implementations are necessary to bridge its capabilities to traditional statistical modeling tasks.

RStudio facilitates ML through its integration with R and Python, offering access to various packages and frameworks [

63]. It utilizes the Caret package for training conventional ML models such as RF and XGBoost. For regression models like OLS and Lasso, RStudio leverages native R packages and Python integrations through Reticulate. Advanced DL models including LSTM and RNN are also supported using TensorFlow and Keras, providing a flexible and powerful toolset for both classical and modern ML approaches.

Each of the five packages offers unique strengths and limitations, and each available model in the five packages to identify the best suited model, and package, for PM2.5 calibration. For our systematic study, the packages, the models, and the training data split are tested to obtain comprehensive analyses. The training process was repeated 10 times for each experiment, and we calculated an average value for the performance metrics (R2 and RMSE).

Note: How PyTorch and TensorFlow implement the OLS Model

PyTorch and TensorFlow employ a SNN to define the OLS regression model. Neural networks process simple sequences of feed-forward layers [

64]. However, these two packages differ in how they define the model and add layers. TensorFlow utilizes a sequential API for model definition, while PyTorch uses a class-based approach [

65]. Moreover, in TensorFlow, the computational graph is a static computation graph while PyTorch uses a dynamic computation graph. The performance gap between the two packages may stem from differences in these computation graph implementations. Nodes represent the neutral network layers, while edges carry the data as tensors [

66].

3.3.1. Model Configuration Standardization across packages

For comparability across packages and models, we standardize model configuration and hyperparameters for each model. For neural network architectures, we standardized the number and type of layers and the number of nodes of each layer across packages compatible with each model. For several models, such as XGBoost and DTRs, it was not possible to completely standardize models across packages because each software and associated package utilized different hyperparameters. In these cases, we used default hyperparameters unique to each package and ensured that common hyperparameters values across packagores were the same. Each model can have dozens of hyper-parameters, we only include those hyper-parameters which were common across packages (

Table 2).

The model configuration standardization used the hyperparameters displayed in

Table 2 and including the following four aspects:

Model Configuration: Each model was configured with a consistent set of hyperparameters across all packages. For neural network models, the number and type of layers, the number of nodes per layer, activation functions, and optimization methods were standardized. For tree-based models and regressions, parameters like tree depth, learning rates, and regularization terms were kept consistent.

Data Preparation: Data input into each model was prepared using a standard preprocessing pipeline. This involved scaling features, handling missing data, and transforming temporal data into sequences for time series models like LSTM.

Training and Test Splits: The data was split into training and test splits using both 80/20 and 70/30 splits to ensure consistency across all experiments.

Computation Environment: All models were trained on a consistent hardware setup to eliminate variations in computing resources.

3.4. Results and Visual-Analytical Methods

3.4.1. Comparative Performance Across Models and Packages

We evaluated each model and package based on two key criteria: time to train and accuracy (RMSE and R2). Averaging the performance metrics (R2 and RMSE) from 10 runs of each model provided insight into which packages delivered higher accuracy and reliability. This allowed us to consider both the ability of a particular configuration to both accurately calibrate LCS and their suitability for various applications. We identified which models offered the best trade-off between training time and predictive accuracy.

We also considered the influence of the packages (e.g., RStudio) and model (e.g., LSTM) on results. These factors are highly intertwined, and the performance of a particular set up depends on both the packages and ML models. As such, we took a two-pronged approach to analyze. First, we assessed the average performance of a model across all packages or a package across all models. Then we assessed the effect that package choice had by comparing each model’s relative performance across all packages. By both considering each model individually and comparing the difference in results when training in one package or another, we can better analyze the influence of package and model choice.

3.4.2. Visual-Analytical Methods

To succinctly convey our findings, we employed several visual-analytical methods using the “ggplot2” package in the RStudio:

line and bar graphs were used to plot the performance metrics for the 70/30 and 80/20 splits across all models and packages, illustrating the differences and their consistency.

A series of box and whisker plots were used to depict the range and distribution of performance scores within each package. This visualization highlighted the internal variability and helped identify packages that generally over- or underperformed.

Model-specific performance was displayed using both box and whisker plots and point charts. The box plots provided a clear view of variability within each model category, while the point charts detailed how model performance correlated with package choice, effectively illustrating package compatibility and model robustness.

These visual analytics together support model evaluations to refine the selection process for future modeling efforts and ensure the most effective model/package can be chosen for AQ calibration tasks.

3.5. Evaluation Metrics:

This study utilizes evaluation metrics Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) and Coefficient of Determination (R2) to evaluate the fit of the PM2.5 calibration model against the EPA data used as benchmark.

The RMSE is calculated using the formula:

Where y

i represents the actual PM

2.5 values from the EPA data, ŷ

i denotes the predicted calibrated PM2.5 values from the model, and n is the number of spatiotemporal data points. This metric measures the average magnitude of the errors between the model’s predictions and the actual benchmark EPA data. A lower RMSE value indicates a model with higher accuracy, reflecting a closer fit to the benchmark.

The Coefficient of Determination, denoted as R

2, is given by:

In this formula, RSS is the sum of the squares of residuals—the difference between actual and predicted values—and TSS is the total sum of squares—the difference between actual values and their mean value. R2 represents the proportion of variance in the observed EPA PM2.5 levels that is predictable from the models. An R2 value close to 1 would suggest that the model has a high degree of explanatory power, aligning well with the variability observed in the EPA dataset.

For a comprehensive understanding of the model’s performance, RMSE and R2 are obtained. RMSE provides a direct measure of prediction accuracy, while R2 offers insight into how well the model captures the overall variance in the EPA dataset. Together, these metrics are crucial for validating the effectiveness of the calibrated PM2.5 model in replicating the benchmark data. RMSE is more resistant to systematic adjustment errors than R2 and as such is used here as the primary metric.

Furthermore, we investigated the training time for different models to identify "sweet spots”—models that were exceptionally accurate compared to their training time. This analysis was crucial for optimizing model selection in practical scenarios where both time and accuracy are critical constraints.

4. Experiments & Results

To obtain a comprehensive result, we implemented a series of experiments to compare the impacts of training/testing split, package, and ML models on accuracy and computing time.

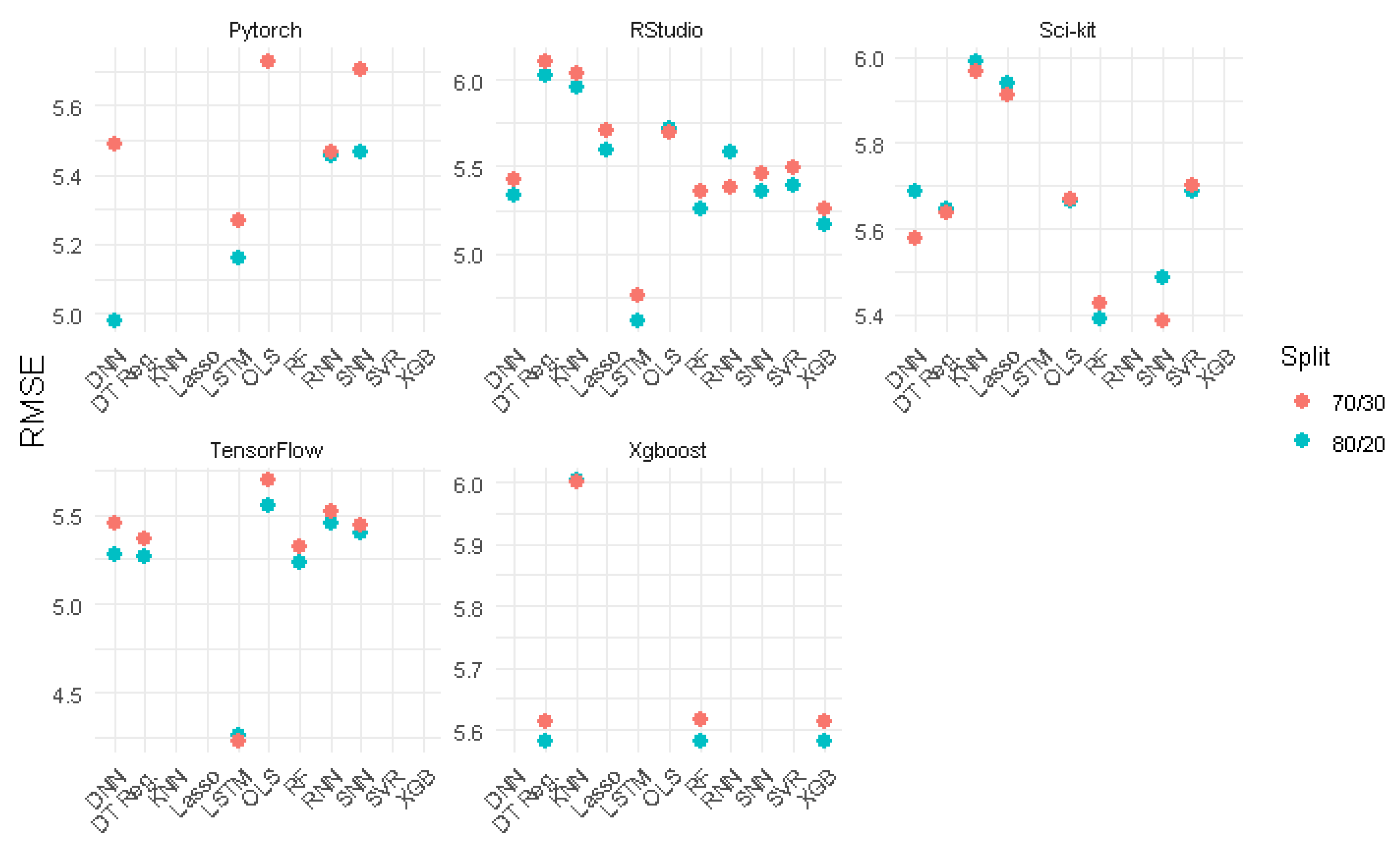

4.1. Train and Test Split

The popular training data splits of 80/20 and 70/30 were examined. The choice of 80/20 vs 70/30 split was found to have minimal impact across models and packages where splits were random, while there was a 2.2% difference of R

2 performance and a 3% difference in RMSE performance in the 80/20 vs 70/30 LSTM model when splits were sequential. The mean difference between the two splits in RMSE across all models and packages was 0.051 µg/m

3 and the mean difference in R

2 was 0.00381, or a mean percent difference of 1.55% for RMSE and a mean percent difference of 0.745% for R

2 across all packages and models (

Figure 3).

The largest difference between 70/30 and 80/20 in terms of RMSE was for DNNs in PyTorch with an absolute difference of 0.51 µg/m

3, the largest difference in terms of R

2 was 0.020 for SNN in PyTorch. This translates to a percent difference of 9.75% and 2.83% respectively. Of the 35 model/package combinations tested, 29 had a difference below 2% for RMSE, and 33 had a percent difference below 2% for R

2 (

Figure 3).

While the differences between splits were minimal (

Figure 3), the 80/20 split (mean R

2 = 0.750, mean RMSE = 5.46 µg/m3) slightly outperformed the 70/30 split (mean R

2 = 0.746, mean RMSE = 5.51 µg/m3) on average. Therefore we use the 80/20 split to compare the packages and models.

4.2. Software Package Comparison

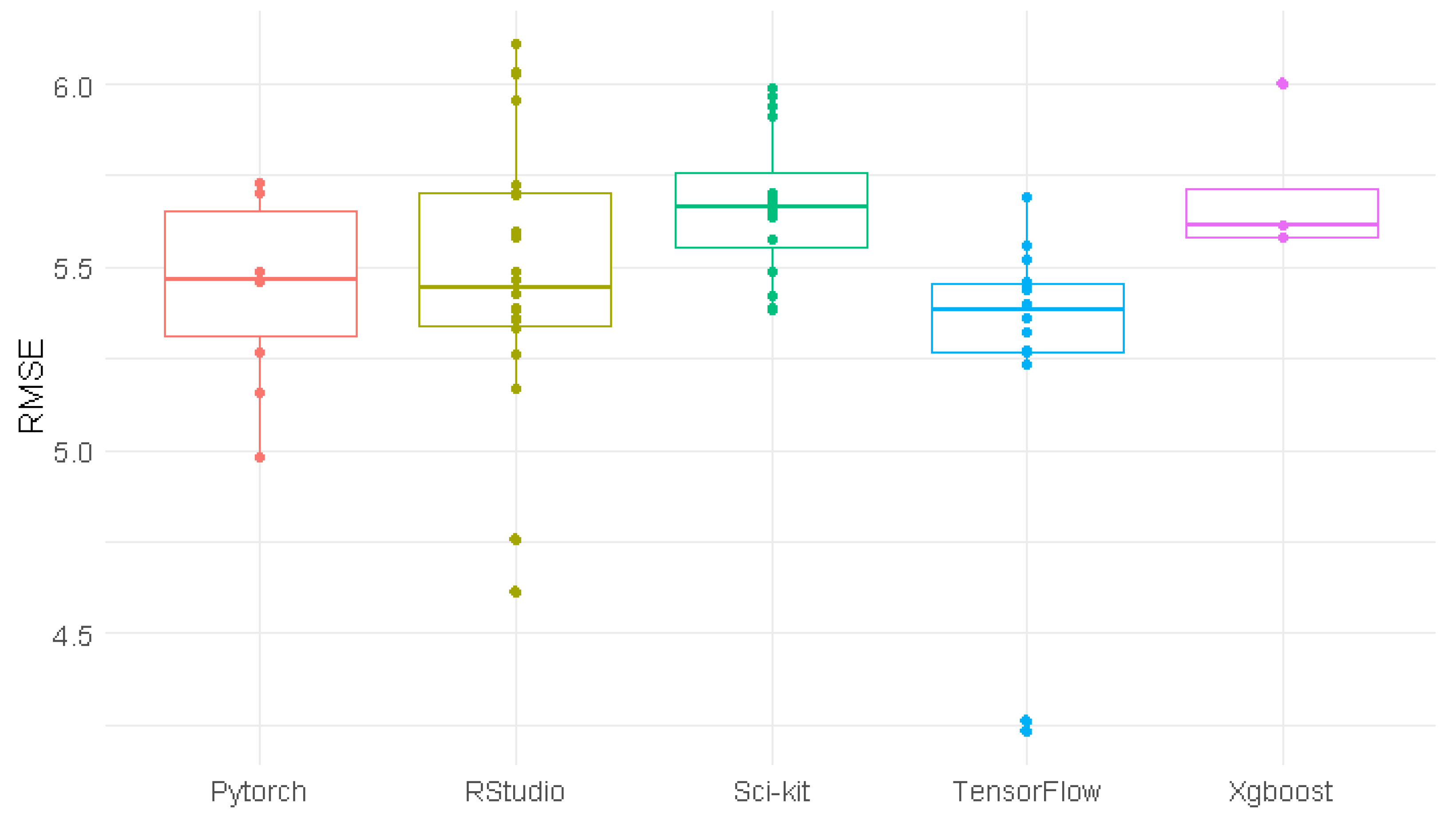

When considering the performance of all models (

Figure 4), TensorFlow (mean R

2 = 0.773) and RStudio (mean R

2 = 0.756) outperformed the other packages, none of which had an average R

2 of above 0.736. This success is driven in part by the strong performance of LSTM on these packages. Apart from RNN, all the top preforming packages across models in terms of maximum R

2 were either RStudio or TensorFlow. PyTorch produced the best model for RNN (R

2 = 0.7658), slightly edging out TensorFlow (R

2 = 0.7657). Conversely, XGBoost and Scikit-Learn did not produce the best results for any of the models tested. TensorFlow emerges as a package particularly well suited to the calibration task because every model that TensorFlow supports, it produced either the best or second best R

2 (

Figure 3).

However, it is important to note that in cases where a model is compatible with several different packages, the difference in performance between the best and second-best packages is negligible. When considering only models that were compatible with 3 or more packages, the average percent difference in R2 between the top performing package and the worst performing package across all models was 6.09%. However, the percentage difference between the top performing packages and the second-best packages was only 0.96%.

This suggests that while packages do have a significant effect on performance, for each model multiple potential packages may be able to produce effective results.

Because not every model is available for every package, comparing overall performance does not fully capture the variation between packages. By considering the relative performance of individual models between packages, we can better elucidate which model and package combination is the best suited for the calibration task. While many of the models were consistent across packages, there are some notable outliers. OLS regression displayed the largest difference in performance across packages in terms of R

2, with a percentage difference of 10.06% between the best performing package (TensorFlow) and the worst performing package (PyTorch). This difference can be attributed to the different methods that these packages calculate linear regression, as discussed in section 3.2. DTRs, LSTM, and SNN all saw a percentage absolute difference of 9% to 10% for R

2 between the best performing and worst performing models. Other models had a percentage absolute difference between 1% and 5% across packages (

Table 3).

The effect of package choice is even more pronounced when considering RMSE. For example, the absolute percent difference between LSTM when training in the worst performing package, PyTorch, and when training in the best performing package, TensorFlow, was 19.3% (

Table 4). In certain cases, like LSTM, the selection of packages can have a significant effect on performance even when the same model is selected.

While LSTM produces the best results in all packages that support the model, it is significantly more accurate when trained in RStudio and TensorFlow than in PyTorch (

Table 3 and

Table 4). However, it takes approximately 18-19 times longer to train on RStudio compared to PyTorch (Table 8). It is unsurprising that RStudio and TensorFlow exhibit notably similar performances because LSTM in RStudio is powered by TensorFlow.

The time and performance differences between PyTorch and TensorFlow may be the result of the different ways that the two packages implement models. TensorFlow incorporates parameters within the model compilation process through Keras. In contrast, in PyTorch parameters are instantiated as variables and incorporated into custom training loops, as opposed to the more streamlined .fit() method utilized in TensorFlow [

67]. Furthermore, PyTorch employs a dynamic computation graph for seamless tracking of operations, while TensorFlow static computational graph requires explicit directives [

65]. PyTorch leverages an automatic differentiation engine to compute derivatives and gradients of computations. Moreover, PyTorch's DataLoader class offers a way to load and preprocess data, thus reducing the time required for data loading.

4.3. Model Comparison

Each model's performance is determined by the model itself and the supporting package. However, the model chosen had a greater overall effect on accuracy than which package was selected. Certain models generally outperformed or underperformed regardless of package.

The top performing model by average R

2 and RMSE across software packages was LSTM, which outperformed all other models by a large margin (R

2 = 0.832, RMSE = 4.55 µg/m

3) (

Table 3 and

Table 4). LSTM and RNN are a type of neural network specifically designed for time series modeling and incorporate past data to support predictions on future sensor values [

46].

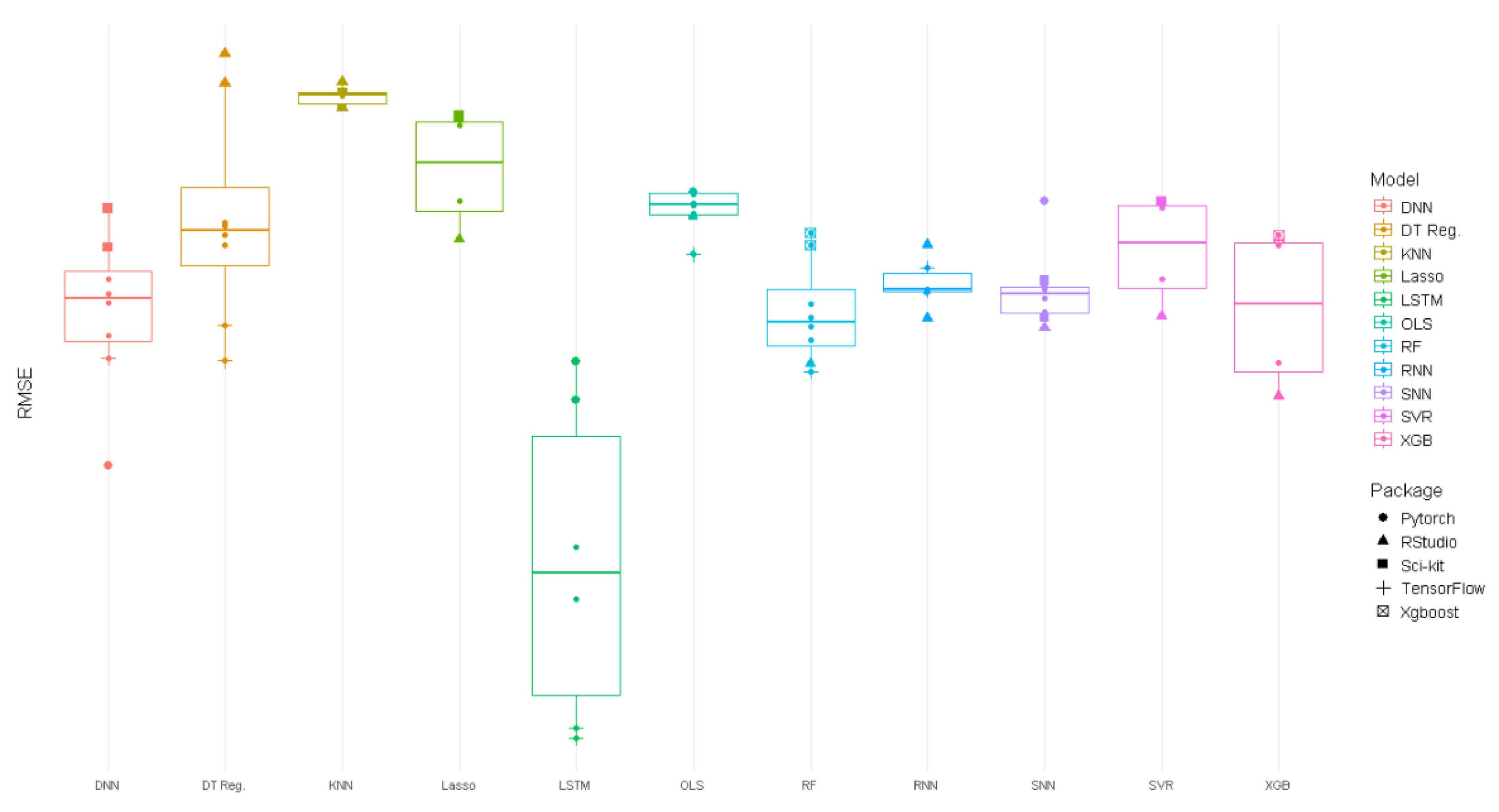

Compared to LSTM, all other models significantly underperformed. Variation in performance among the remaining models was relatively minor (

Figure 5). In fact, the gap in mean R

2 (0.07) from LSTM to the second-best model, RF, was larger than the gap from RF to the worst performing model, KNN (0.06) (

Table 3). The same pattern holds true for RMSE. The gap from LSTM to the second- best model in terms of mean RMSE, DNN was 0.76 µg/m

3. The difference between DNN and KNN was 0.66 µg/m

3.

Table 4 and

Table 5 summarize the percentage difference in R

2and RMSE between models, when considering the best performing packages for each model. The percentage difference between each model’s best performer as compared to the median performer, SNN and the worst performer, KNN is included. While LSTM outperformed the median by 11.48% in terms of R

2, none of the other models were more than 7% different from the median. In fact, 8 of the 11 models had an R

2 within 3% of the median performance. When comparing models to the worst performer, the same trend is evident. While LSTM had an R

2 18.46% higher than the worst performer, no other model outperformed the minimum by more than 9.1%. The same pattern holds true for RMSE, although there is slightly more variance between models. LSTM again is far the best performer, with a 23% lower RMSE value than the median model (DNN by this metric). All other models were within 10.6% of the median, and 8 of the 11 models were within 5% of the median value (

Table 6).

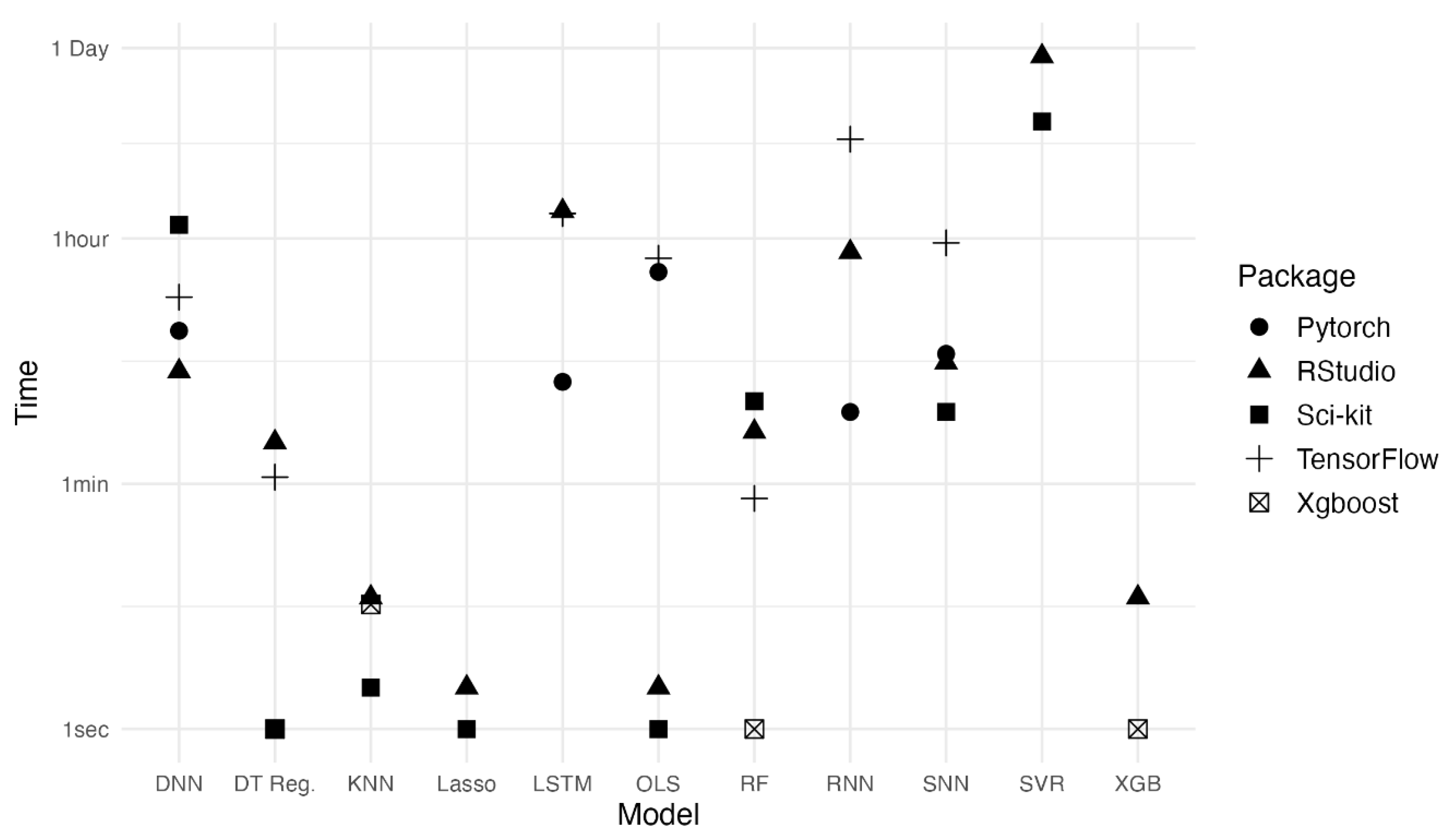

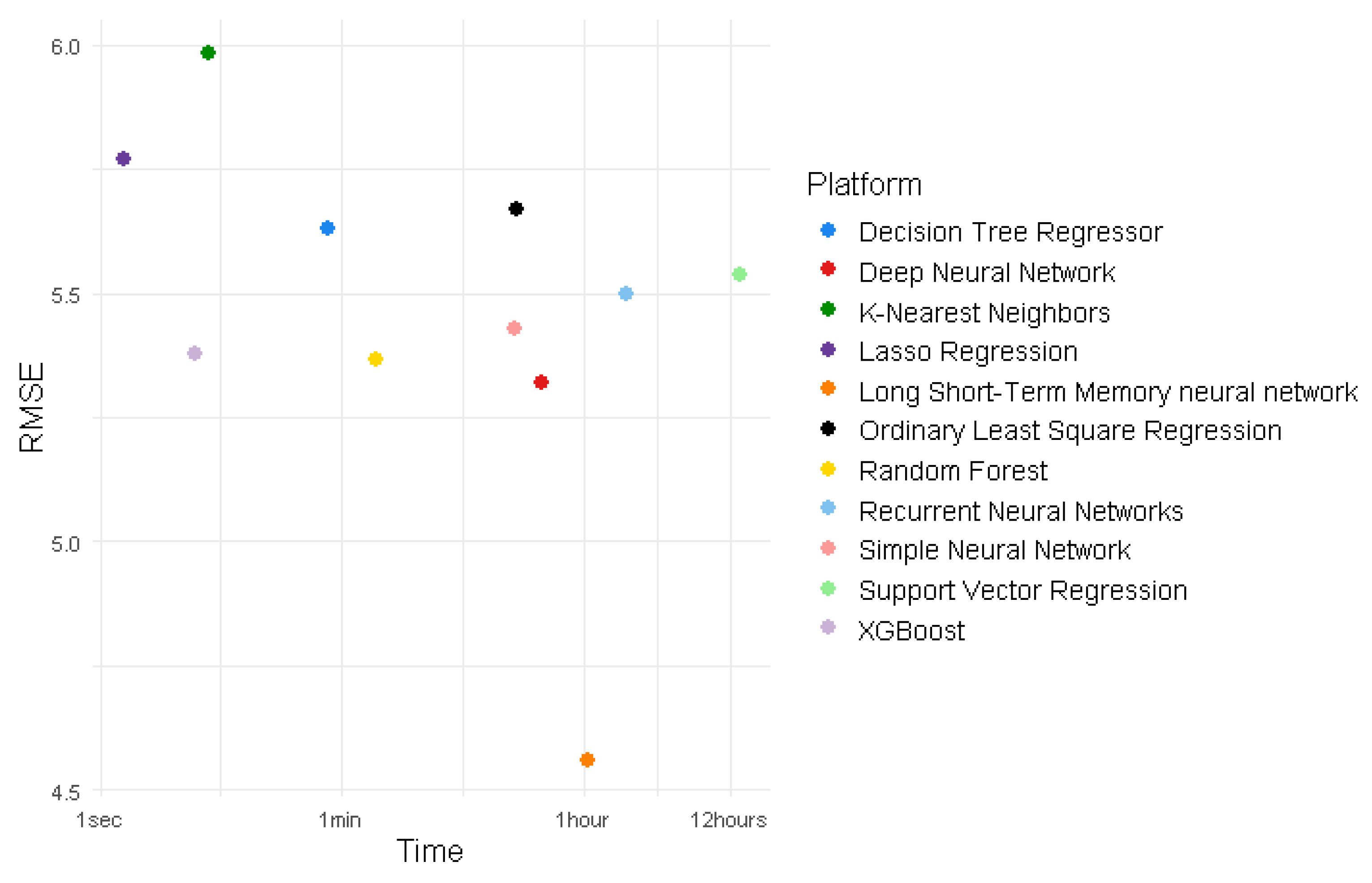

While these models displayed a relatively minor difference in performance in terms of R

2 and RMSE, their train time was vastly different. For example, XGBoost took only 5 seconds to train on average while SVR took 13 hours, 45 minutes and 17 seconds to train (

Table 7).

Figure 6.

Time to train by model and package. Note the y-axis specifies time non-linearly.

Figure 6.

Time to train by model and package. Note the y-axis specifies time non-linearly.

While LSTM produces a high R

2 value, it takes significantly longer to train than most other models. The fastest models to train are DTR, XGBoost, RF, KNN, and Lasso, all of which took less than two minutes to train. Among these models, XGBoost (0.7612, 5.377 µg/m

3) and RF (0.7632, 5.366 µg/m

3) performed the best in terms of R

2 and RMSE (

Figure 7).

These results indicate that the LSTM model in TensorFlow and RStudio provides the highest accuracy, making it suitable for real-time AQ monitoring applications where high precision is crucial.

5. Conclusions

This paper reported a systematic investigation of 5 popular software packages and 11 ML models suitability for LCS AQ data calibration. Our investigation revealed that the choice of training/testing split—80/20 vs 70/30—had minimal impact on the performance across various models and packages. The percentage difference between the model split performance (R2) averaged 0.745% and therefore we focused on the 80/20 split for a detailed comparison in subsequent analyses.

In package comparison, RStudio and TensorFlow are the top performers, particularly excelling with LSTM models. Their performance shows R2 scores of 0.8578 and 0.857 and low RMSEs of 4.2518 µg/m3 and 4.26 µg/m3 respectively. Their strong ability to process high-volume data and capture complex relationships with neural network models such as LSTM is indictive. However, while RStudio outperforms TensorFlow by 0.09% in LSTM, TensorFlow typically outperforms RStudio in every other model by 1.7%, averaging a R2 of 0.773 in TensorFlow and 0.756 in RStudio.

The choice of packages affects the outcomes when the same models are implemented across different packages. For example, the performance discrepancies in OLS regression across packages underscored the influence of software-specific implementations on model efficacy. When averaging across all models, R2 scores varied by 6.09% between the most and least accurate packages.

The study also highlights the importance of selecting the appropriate combination of model and package based on the specific requirements of the tasks. While some packages showed a broad range in performance, packages like Scikit-Learn showed less variability, indicating a more consistent handling of the models. While the choice of model generally has a greater impact on performance than the package, the nuances in how each package processes and trains models can lead to significant variations in both accuracy and efficiency. For example, while LSTMs generally performed well, their implementation in TensorFlow consistently outperformed that in PyTorch. This highlights the differences in how these packages manage computation graphs.

In conclusion, the detailed insights gained from this research advocate for a context-driven approach in the selection of ML packages and models, ensuring that both model and package choices are optimally aligned to the specific needs and constraints of the predictive task. Across all experiments, two optimal approaches emerge. The overall best performing model in terms of RMSE and R2 was clearly LSTM. However, LSTM algorithms are particularly time intensive to train, each taking over one hour and thirty minutes to train a single model. In addition, preparing sequential training data is a somewhat computationally expensive process. LSTM’s computational demands may make it too slow or expensive to train for certain applications, such as large study areas or applications which require model training on the fly. The high computational load of LSTM models is particularly important to consider for in-depth explorations, such as hyper-parameter tuning. Hyper-parameter tuning these models can require hundreds of training runs, leading to long calculation times. The results also suggest a second potential approach, indicated by the relatively high performance of tree-boosted models in comparison to training time. XGBoost in RStudio and RF in TensorFlow both exhibited R2 values above 0.77, RMSE values below 5.3 µg/m3, and time to train below one minute. In cases where computational resources are low, or models need to be trained quickly on the fly, models such as RF and XGBRegressor may be more applicable than the top performing time series models.

6. Discussion

This section elaborates why the 11 models perform differently, how our results compare to latest relevant research, applicability of our research to other sensors, and the limitations of this study.

6.1. Model Performance and Their Structures

Purple Air and the EPA's PM2.5 datasets are inherently point-based hourly time-series that require models to account for time series handling. These PM2.5 readings are influenced by complex and dynamic relationships with meteorological factors like temperature and relative humidity, so these need to be considered as variables in addition to raw PM2.5 when building a model. As evidenced in

Table 8, models like RF, DT, and XGB, while they are effective for multivariable inputs and feature interaction, treat data points independently. This makes them less suitable for time-series tasks without significant feature engineering [

88]. Meanwhile, models such as KNN and SVR lack the capability of capturing time series patterns, limiting their effectiveness for time-series-based calibration [

89]. However, LSTMs excel in handling time series data by using hidden and cell states to learn temporal patterns across time steps [

90] and captures these nonlinear and interdependent relationships between the input variables and the output with their combined influences through its ability to utilize time series data. Forget and memory gates enable LSTM to smooth irregular patterns in PM2.5 data, reducing the impact of noise and sensor errors commonly found in environmental datasets [

91]. Unlike traditional RNNs, which suffer from the vanishing/exploding gradient problem, LSTM's architecture is better suited [

91,

92]. This design allows LSTMs to retain long-term dependencies, which are essential in understanding the temporal patterns in PM2.5 data [

93]. In conclusion, LSTM’s dual hidden state allows it to maintain short- and long-term dependencies across time-series data; captures nonlinear influences between PM2.5 and meteorological variables without manual feature engineering; and smooths irregular patterns in data through memory gates.

6.2. Comparison to Existing Studies

We compared our study with all PM

2.5 calibration using AI/ML techniques (

Table 9) in a number of factors: sensor count, sensor quality and performance, comprehensive model evaluation, and sensor type and calibration. A key factor influencing model performance is the number of sensors used. This study utilizes 64 PurpleAir sensors, a significantly larger dataset compared to previous works, which often relied on fewer sensors (e.g., 1-9). The use of a larger sensor network introduces greater data variability, enhancing the model’s ability to capture diverse environmental conditions. The studies by [

41,

43] demonstrated that calibrating single LCS using models yielded high R² values. However, their limited sensor count may reduce generalizability across different environmental conditions, as fewer sensors may not fully capture the natural variability present in PM2.5 measurements.

Another key factor in this comparison is comprehensive model evaluation. This study systematically evaluates 11 machine learning models across five software packages, including TensorFlow and PyTorch. By incorporating a diverse range of models, from simple linear methods to complex architectures like DNN and LSTM, it offers a more extensive performance assessment than previous studies, which often focused on fewer models within a single framework. While this study evaluates 11 models, [

44] used a maximum of three models (ANN, GBDT, RF) in their calibration efforts, demonstrating a more limited exploration of model diversity. This multi-model, multi-package approach helps identify the best-performing models for the given data while minimizing bias and improving the reliability of PM2.5 calibration results.

The third key factor for comparison is sensor type and quality. The high accuracy reported by [

44] was attributed to comprehensive field calibration against industry-grade instruments, ensuring robust validation. Similarly, [

45] achieved high accuracy due to the initial high agreement among sensors (R² of 0.89), indicating strong baseline data quality prior to extensive calibration. In contrast, this study utilized 64 PurpleAir PMS5003 sensors without direct field calibration but instead applied a much flexible agreement threshold of R² ≥ 0.70 to ensure data quality while capturing diverse environmental conditions. Additionally, sensor type can influence calibration outcomes, as seen in [

46], where the SPS30 sensor paired with a HybridLSTM calibration model yielded a high R² of 0.93. Despite being a low-cost sensor (LCS), the SPS30 often outperforms other sensors like the PMS5003, likely due to its higher sensitivity and improved particle size differentiation [

47].

6.3. Applicability of the Results to Other Air Quality Sensors

Table 10 explores the applicability of this methodology to other air quality sensor technologies. This workflow could be applicable to any sensor testing for PM

2.5, however the approach may vary depending on each specific sensor’s needs and the technologies that they utilize. This general workflow could be applied to other pollutants and aerosols; however, the results may differ due to the differences in dispersion behavior that occur from pollutant to pollutant.

6.4. Limitations

This study presents a systematic calibration study for PM2.5 sensors with promising results. There are some limitations for its findings and guiding future research. These limitations span the geographic and technological scope of sensor deployment, the pollutant species, computational constraints, and the limited available meteorological variables.

Sensor Pair Distribution – The current study utilized 64 sensor pairs from California, incorporating data from 25 unique EPA sensors. This limited geographic and technological scope may limit the broader applicability of the model, particularly for nationwide or larger-scale contexts. Further research could be added to determine the optimal scope and effectiveness of the trained model across diverse regions.

Pollutant Species – The calibration study was exclusively focused on PM2.5 and did not extend its methodology to other pollutants. The generalizability of the approach to additional pollutants, such as ozone or nitrogen dioxide, could be investigated through similar calibration efforts.

Sensor Technology – The study was confined to data collected from EPA and Purple Air sensors. While these sensors are widely used, the approach should be repeated when translating to other types of PM2.5 sensors or to sensors measuring different pollutants. Future studies should explore the calibration and performance of alternative sensor technologies to enhance the study’s applicability.

Computational Constraints – The calibration process was conducted using CPU-based processing, which required approximately one month of continuous runtime. This computational limitation suggests that further studies could benefit significantly from leveraging GPU-based processing to reduce runtime [

68]. Additionally, adopting containerization technologies such as Docker could streamline setup and configuration, thereby improving efficiency and reproducibility.

Meteorological Constraints – While this study accounted for the impact of temperature and humidity on sensor calibration, it did not consider other potentially influential meteorological factors, such as wind speed, wind direction, and atmospheric pressure. These features were either found to have marginal impacts in the case of pressure or were unavailable inside the dataset such as in the case of wind speed and direction. Further studies with sensors that measure these variables could potentially further improve model accuracy.

6.5. Future Work

Though this study is extensive and systematic, four aspects need further investigation to best leverage AI/ML for air quality studies on various pollutants, data analytical components, and further improvements of accuracy for the calibration:

Hyperparameter tuning should be able to further improve accuracy and reduce uncertainty but will require significant computing power and many times of model training to investigate different combinations. LSTM emerged as the best performing model in this study. We plan to further explore the application of this model, including detailed hyper-parameter tuning/model optimization.

Different species of air pollutants may have different patterns so a systematic study on each of them might be needed for, e.g., NO2 and Ozone or Methane. In-situ sensors offer comprehensive temporal coverage but lack continuous geographic coverage introducing satellite retrieval of pollutants could complement air pollution detection.

Further exploration of other analytics such as data downscaling, upscaling, interoperation, and fusion to best replicate air pollution status is needed for overall air pollutants data integration.

To better facilitate the systematic study and extensive AI/ML model runs, an adaptable ML toolkit and potential Python package can be developed and packaged to speed up the AQ research and forecasting research.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.Y., A.S., S.S., D.D.; methodology, T.T.,S.S., C.Y., A.S.; Validation, T.T., S.S,, S.L., G.J.; writing—original draft preparation, S.S., T.T., A. M., C.Y., S.L.; writing—review and editing, C.Y., T.T., S.S.; Data, J.L., A.S., S.S.; software, S.S., A.S., S.L., J.L., X.J., Z.W., J.C., T.H., M.P., G.L., W.P., S.H., J.R., K.M.; experiments, S.S., A.S., S.L., J.L., X.J., Z.W., J.C., T.H., M.P., G.L., W.P., S.H., J.R., K.M.; funding C.Y. and D. D.; management and coordination, C.Y., S.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

References

- Masood, A.; Ahmad, K. A review on emerging artificial intelligence (AI) techniques for air pollution forecasting: Fundamentals, application and performance. Journal of Cleaner Production 2021, 322, 129072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barkjohn, K. K.; Norris, C.; Cui, X.; Fang, L.; Zheng, T.; Schauer, J. J.; Bergin, M. H. Real-time measurements of PM2. 5 and ozone to assess the effectiveness of residential indoor air filtration in Shanghai homes. Indoor Air 2021, 31(1), 74–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NIH; National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences. Air pollution and your health. 2024. Available online: https://www.niehs.nih.gov/health/topics/agents/air-pollution.

- Chojer, H.; Branco, P. T. B. S.; Martins, F. G.; Alvim-Ferraz, M. C. M.; Sousa, S. I. V. Development of low-cost indoor air quality monitoring devices: Recent advancements. Science of The Total Environment 2020, 727, 138385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bu, X.; Xie, Z.; Liu, J.; Wei, L.; Wang, X.; Chen, M.; Ren, H. Global PM2. 5-attributable health burden from 1990 to 2017: Estimates from the Global Burden of disease study 2017. Environmental Research 2021, 197, 111123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, K; Dhammapala, R; Harrington, K; Lamb, B; Lee, Y. Machine learning-based ozone and PM2.5 forecasting: Application to multiple AQS sites in the Pacific Northwest. Front Big Data 2023, 6, 1124148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tai, A. P.; Mickley, L. J.; Jacob, D. J. Correlations between fine particulate matter (PM2. 5) and meteorological variables in the United States: Implications for the sensitivity of PM2. 5 to climate change. Atmospheric environment 2010, 44(32), 3976–3984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N.; Park, R. J.; Jeong, J. I.; Woo, J. H.; Kim, Y.; Johnson, J.; Knipping, E. Contributions of international sources to PM2. 5 in South Korea. Atmospheric Environment 2021, 261, 118542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, H.-J.; Ali, M. Z.; He, Y.-C. Spatial calibration and PM2.5 mapping of low-cost air quality sensors. Scientific Reports 2020, 10(1), 22079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.; Shusterman, A. A.; Lieschke, K. J.; Newman, C.; Cohen, R. C. The Berkeley atmospheric CO 2 observation network: Field calibration and evaluation of low-cost air quality sensors. Atmospheric Measurement Techniques 2018, 11(4), 1937–1946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polidori, A.; Papapostolou, V.; Zhang, H. Laboratory evaluation of low-cost air quality sensors; South Coast Air Quality Management District; Diamondbar, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Li, J.; Jing, H.; Zhang, Q.; Jiang, J.; Biswas, P. Laboratory Evaluation and Calibration of Three Low-Cost Particle Sensors for Particulate Matter Measurement. Aerosol Science and Technology 2015, 49(11), 1063–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M. G.; Choi, J. S.; Park, W. T. MEMS PZT oscillating platform for fine dust particle removal at resonance. International Journal of Precision Engineering and Manufacturing 2018, 19, 1851–1859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mead, M. I.; Popoola, O. A. M.; Stewart, G. B.; Landshoff, P.; Calleja, M.; Hayes, M.; Baldovi, J. J.; McLeod, M. W.; Hodgson, T. F.; Dicks, J.; Lewis, A.; Cohen, J.; Baron, R.; Saffell, J. R.; Jones, R. L. The use of electrochemical sensors for monitoring urban air quality in low-cost, high-density networks. Atmospheric Environment 2013, 70, 186–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spinelle, L.; Gerboles, M.; Villani, M. G.; Aleixandre, M.; Bonavitacola, F. Field calibration of a cluster of low-cost commercially available sensors for air quality monitoring. Part B: NO, CO and CO2. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical 2017, 238, 706–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyapustin, A.; Wang, Y.; Xiong, X.; Meister, G.; Platnick, S.; Levy, R.; Franz, B.; Korkin, S.; Hilker, T.; Tucker, J. Scientific impact of MODIS C5 calibration degradation and C6+ improvements. Atmospheric Measurement Techniques 2014, 7(12), 4353–4365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Liu, Q.; Ying, N.; Wang, X.; Ma, J. Air quality evaluation on an urban scale based on MODIS satellite images. Atmospheric research 2013, 132, 22–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, Z.; Bai, K.; Wei, Y.; Xie, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Ou, Y.; Cohen, J.; Zhang, Y.; Peng, Z.; Zhang, X.; Chen, C.; Hong, J.; Xu, H.; Guang, J.; Lv, Y.; Li, K.; Li, D. Satellite remote sensing of atmospheric particulate matter mass concentration: Advances, challenges, and perspectives. Fundamental Research 2021, 1(3), 240–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- deSouza, P.; Kahn, R.; Stockman, T.; Obermann, W.; Crawford, B.; Wang, A.; Crooks, J.; Li, J.; Kinney, P. Calibrating networks of low-cost air quality sensors. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 2022, 15(21), 6309–6328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, T.; Liu, Y.; Garcia, A.; Wang, M.; Li, Y.; Bravo-villasenor, G.; Campos, K.; Xu, J.; Han, B. Leveraging Citizen Science and Low-Cost Sensors to Characterize Air Pollution Exposure of Disadvantaged Communities in Southern California. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2022, 19(14). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caseiro, A.; Schmitz, S.; Villena, G.; Jagatha, J. V.; von Schneidemesser, E. Ambient characterisation of PurpleAir particulate matter monitors for measurements to be considered as indicative. Environmental Science: Atmospheres 2022, 2(6), 1400–1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giordano, M. R.; Malings, C.; Pandis, S. N.; Presto, A. A.; McNeill, V. F.; Westervelt, D. M.; Beekmann, M.; Subramanian, R. From low-cost sensors to high-quality data: A summary of challenges and best practices for effectively calibrating low-cost particulate matter mass sensors. Journal of Aerosol Science 2021, 158, 105833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.-H.; Wang, Y.-B.; Yu, H.-L. An efficient spatiotemporal data calibration approach for the low-cost PM2. 5 sensing network: A case study in Taiwan. Environment international 2019, 130, 104838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, J.; Zhang, Y.; de Foy, B.; Mei, X.; Shang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Sulaymon, I. D.; Zhou, D. Improved PM2.5 concentration estimates from low-cost sensors using calibration models categorized by relative humidity. Aerosol Science and Technology 2021, 55(5), 600–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raysoni, A. U.; Pinakana, S. D.; Mendez, E.; Wladyka, D.; Sepielak, K.; Temby, O. A Review of Literature on the Usage of Low-Cost Sensors to Measure Particulate Matter. Earth 2023, 4(1), 168–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, K. K.; Bergin, M. H.; Russell, A. G.; Hagler, G. S. W. Field Test of Several Low-Cost Particulate Matter Sensors in High and Low Concentration Urban Environments. Aerosol Air Qual Res 2018, 18(3), 565–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khreis, H.; Johnson, J.; Jack, K.; Dadashova, B.; Park, E. S. Evaluating the Performance of Low-Cost Air Quality Monitors in Dallas, Texas. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2022, 19(3). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mykhaylova, N. Low-cost Sensor Array Devices as a Method for Reliable Assessment of Exposure to Traffic-related Air Pollution (Publication Number 10973729). Ph.D., University of Toronto, Canada, 2018. ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global; SciTech Premium Collection. Canada -- Ontario, CA. Available online: http://mutex.gmu.edu/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/low-cost-sensor-array-devices-as-method-reliable/docview/2149673888/se-2?accountid=14541.

- Jayaratne, R.; Liu, X.; Thai, P.; Dunbabin, M.; Morawska, L. The influence of humidity on the performance of a low-cost air particle mass sensor and the effect of atmospheric fog. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 2018, 11(8), 4883–4890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Antonio, A.; Popoola, O. A. M.; Ouyang, B.; Saffell, J.; Jones, R. L. Developing a Relative Humidity Correction for Low-Cost Sensors Measuring Ambient Particulate Matter. Sensors (Basel) 2018, 18(9). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holstius, D. M.; Pillarisetti, A.; Smith, K. R.; Seto, E. Field calibrations of a low-cost aerosol sensor at a regulatory monitoring site in California. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 2014, 7(4), 1121–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Shin, D.; Hwang, J. Calibration of Low-cost Sensors for Measurement of Indoor Particulate Matter Concentrations via Laboratory/Field Evaluation. Aerosol and Air Quality Research 2023, 23(8), 230097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagan, D. H.; Kroll, J. H. Assessing the accuracy of low-cost optical particle sensors using a physics-based approach. (1867-1381 (Print)).

- Prajapati, B.; Dharaiya, V.; Sahu, M.; Venkatraman, C.; Biswas, P.; Yadav, K.; Pullokaran, D.; Raman, R. S.; Bhat, R.; Najar, T. A.; Jehangir, A. Development of a physics-based method for calibration of low-cost particulate matter sensors and comparison with machine learning models. Journal of Aerosol Science 2024, 175, 106284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malings, C.; Tanzer, R.; Hauryliuk, A.; Saha, P. K.; Robinson, A. L.; Presto, A. A.; Subramanian, R. Fine particle mass monitoring with low-cost sensors: Corrections and long-term performance evaluation. Aerosol Science and Technology 2020, 54(2), 160–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulot, F. M. J.; Ossont, S. J.; Morris, A. K. R.; Basford, P. J.; Easton, N. H. C.; Mitchell, H. L.; Foster, G. L.; Cox, S. J.; Loxham, M. Characterisation and calibration of low-cost PM sensors at high temporal resolution to reference-grade performance. Heliyon 2023, 9(5), e15943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jovašević-Stojanović, M.; Bartonova, A.; Topalović, D.; Lazović, I.; Pokrić, B.; Ristovski, Z. On the use of small and cheaper sensors and devices for indicative citizen-based monitoring of respirable particulate matter. Environmental Pollution 2015, 206, 696–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakayama, T.; Matsumi, Y.; Kawahito, K.; Watabe, Y. Development and evaluation of a palm-sized optical PM2.5 sensor. Aerosol Science and Technology 2018, 52(1), 2–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topalović, D. B.; Davidović, M. D.; Jovanović, M.; Bartonova, A.; Ristovski, Z.; Jovašević-Stojanović, M. In search of an optimal in-field calibration method of low-cost gas sensors for ambient air pollutants: Comparison of linear, multilinear and artificial neural network approaches. Atmospheric Environment 2019, 213, 640–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Du, Y.; Wang, J.; Li, T. Calibration of a low-cost PM2.5 monitor using a random forest model. Environment international 2019, 133, 105161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zhu, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, T.; Jiang, Y.; Shan, Y.; Liu, Y.; Mu, J.; Yin, X.; Wu, D.; Zhang, C.; Si, S.; Wang, X.; Wang, W.; Xue, L. Evaluation of the Performance of Low-Cost Air Quality Sensors at a High Mountain Station with Complex Meteorological Conditions. Atmosphere 2020, 11(2). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Commodore, S.; Metcalf, A.; Post, C.; Watts, K.; Reynolds, S.; Pearce, J. A Statistical Calibration Framework for Improving Non-Reference Method Particulate Matter Reporting: A Focus on Community Air Monitoring Settings. Atmosphere 2020, 11(8). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, M.; Xiong, Y.; Du, S.; Du, K. Evaluation and calibration of a low-cost particle sensor in ambient conditions using machine-learning methods. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 2020, 13(4), 1693–1707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahajan, S.; Kumar, P. Evaluation of low-cost sensors for quantitative personal exposure monitoring. Sustainable Cities and Society 2020, 57, 102076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, X.; Hou, L.; Gao, J.; Si, S. The evaluation and optimization of calibration methods for low-cost particulate matter sensors: Inter-comparison between fixed and mobile methods. Science of The Total Environment 2020, 715, 136791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, D.; Yoo, G.-W.; Park, S.-H.; Lee, J.-H. Assessment and Calibration of a Low-Cost PM2.5 Sensor Using Machine Learning (HybridLSTM Neural Network): Feasibility Study to Build an Air Quality Monitoring System. Atmosphere 2021, 12(10). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulot, F. M.; Russell, H. S.; Rezaei, M.; Johnson, M. S.; Ossont, S. J.; Morris, A. K.; Basford, P. J.; Easton, N. H.; Mitchell, H. L.; Foster, G. L.; Loxham, M.; Cox, S. J. Laboratory Comparison of Low-Cost Particulate Matter Sensors to Measure Transient Events of Pollution—Part B—Particle Number Concentrations. Sensors 2023, 23(17). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

Decisiontreeregressor. scikit-learn. 2024. Available online: https://scikit-learn.org/stable/modules/generated/sklearn.tree.DecisionTreeRegressor.html.

- What is Random Forest?. IBM. 20 October 2021a. Available online: https://www.ibm.com/topics/random-forest#:~:text=Random%20forest%20is%20a%20commonly,both%20classification%20and%20regression%20problems.

- K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN). 20 October 2021b. Available online: https://www.ibm.com/docs/en/db2oc?topic=procedures-k-nearest-neighbors-knn.

- XGBoost. 2022. Available online: https://xgboost.readthedocs.io/en/stable/.

- SVR. scikit. 2024. Available online: https://scikit-learn.org/stable/modules/generated/sklearn.svm.SVR.html.

- Mohammadi, M.; Das, S. SNN: stacked neural networks. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1605.08512. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidhuber, J. Deep learning in neural networks: An overview. Neural networks 2015, 61, 85–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- What are recurrent neural networks?. IBM. 6 October 2021c. Available online: https://www.ibm.com/topics/recurrent-neural-networks.

- Staudemeyer, R. C.; Morris, E. R. Understanding LSTM--a tutorial into long short-term memory recurrent neural networks. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1909.09586. [Google Scholar]

-

How OLS regression works. How OLS regression works-ArcGIS Pro Documentation. 2024. Available online: https://pro.arcgis.com/en/pro-app/latest/tool-reference/spatial-statistics/how-ols-regression-works.htm#:~:text=Ordinary%20Least%20Squares%20(OLS)%20is,equation%20to%20represent%20that%20process.

- What is lasso regression?. IBM. 16 January 2024. Available online: https://www.ibm.com/topics/lasso-regression#:~:text=Lasso%20regression%E2%80%94also%20known%20as,W%20)%20%2B%20%7C%7Cw%7C%7C1.

- Chen, T.; Guestrin, C. Xgboost: A scalable tree boosting system. In Proceedings of the 22nd acm sigkdd international conference on knowledge discovery and data mining; August 2016; pp. 785–794. [Google Scholar]

- Kramer, O.; Kramer, O. Scikit-learn. Machine learning for evolution strategies 2016, 45–53. [Google Scholar]

- Abadi, M. TensorFlow: learning functions at scale. In Proceedings of the 21st ACM SIGPLAN international conference on functional programming; September 2016; pp. 1–1. [Google Scholar]

- Imambi, S.; Prakash, K. B.; Kanagachidambaresan, G. R. PyTorch. Programming with TensorFlow: solution for edge computing applications 2021, 87–104. [Google Scholar]

- Kronthaler, F.; Zöllner, S. Data analysis with RStudio. Data Analysis with RStudio. 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Paszke; Adam; et al. "Pytorch: An imperative style, high-performance deep learning library. "Advances in neural information processing systems 2019, 32. [Google Scholar]

- Kurama, V. PyTorch vs. TensorFlow: Key Differences to Know for Deep Learning. Built In. 7 March 2024. Available online: https://builtin.com/data-science/pytorch-vs-tensorflow.

- Team; The Educative. “Pytorch vs. Tensorflow: The Key Differences That You Should Know.” Medium, Dev Learning Daily. 1 Mar 2024. learningdaily.dev/pytorch-vs-tensorflow-the-key-differences-that-you-should-know-534184a22f90.

- Ml, S. PyTorch vs TensorFlow: Model Training - Splitwire ML - Medium. Medium. 8 September 2023. Available online: https://medium.com/@splitwireML/pytorch-vs-tensorflow-model-training-7518b7aa7a5e.

- Wang, Z.; Li, Y.; Wang, K.; Cain, J.; Salami, M.; Duffy, D. Q.; Yang, C. Adopting GPU computing to support DL-based Earth science applications. International Journal of Digital Earth 2023, 16(1), 2660–2680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Jiang, S.; Land, K. C. Multicollinearity in hierarchical linear models. Soc Sci Res 2015, 53, 118–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomaschek, F.; Hendrix, P.; Baayen, R. H. Strategies for addressing collinearity in multivariate linguistic data; J Phon, Nov 2018; vol. 71, pp. 249–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, J. G.; Chow, J. C.; DuBois, D.; Green, M.; Frank, N. Guidance for the network design and optimum site exposure for PM2. 5 and PM10. 1997. Available online: https://www3.epa.gov/ttnamti1/files/ambient/pm25/network/r-99-022.pdf.

- Gilliam, J.; Hall, E. Reference and equivalent methods used to measure national ambient air quality standards (naaqs) criteria air pollutants-Volume I. Environmental Protection Agency: Washington, DC, USA. 2016. Available online: https://nepis.epa.gov/Exe/ZyPDF.cgi/P100RTU1.PDF?Dockey=P100RTU1.PDF.

- Zarzycki, K.; Ławryńczuk, M. LSTM for Modelling and Predictive Control of Multivariable Processes. In International Conference on Innovative Techniques and Applications of Artificial Intelligence; Springer Nature Switzerland; Cham, November 2024; pp. 74–87. [Google Scholar]

- Krause, B.; Lu, L.; Murray, I.; Renals, S. Multiplicative LSTM for sequence modelling. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1609.07959. [Google Scholar]

- Tam, Y. C.; Shi, Y.; Chen, H.; Hwang, M. Y. RNN-based labeled data generation for spoken language understanding. In INTERSPEECH; September 2015; pp. 125–129. [Google Scholar]

- Keren, G.; Schuller, B. Convolutional RNN: an enhanced model for extracting features from sequential data. In 2016 International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN); IEEE, July 2016; pp. 3412–3419. [Google Scholar]

- El Fouki, M.; Aknin, N.; El Kadiri, K. Multidimensional Approach Based on Deep Learning to Improve the Prediction Performance of DNN Models. International Journal of Emerging Technologies in Learning 2019, 14(2). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zheng, Y.; Qi, D.; Li, R.; Yi, X. DNN-based prediction model for spatio-temporal data. In Proceedings of the 24th ACM SIGSPATIAL international conference on advances in geographic information systems; October 2016; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Caselli, M.; Trizio, L.; De Gennaro, G.; Ielpo, P. A simple feedforward neural network for the PM 10 forecasting: Comparison with a radial basis function network and a multivariate linear regression model. Water, Air, and Soil Pollution 2009, 201, 365–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Wu, Z.; Xu, G.; Liu, Y.; Zou, Q. Decision tree for sequences. IEEE transactions on Knowledge and Data Engineering 2021, 35(1), 251–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siciliano, R.; Mola, F. Multivariate data analysis and modeling through classification and regression trees. Computational Statistics & Data Analysis 2000, 32(3-4), 285–301. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, G. F.; Zhang, L. Z.; Yu, M.; Hong, W. C.; Dong, S. Q. Applications of random forest in multivariable response surface for short-term load forecasting. International Journal of Electrical Power & Energy Systems 2022, 139, 108073. [Google Scholar]

- Goehry, B.; Yan, H.; Goude, Y.; Massart, P.; Poggi, J. M. Random forests for time series. REVSTAT-Statistical Journal 2023, 21(2), 283–302. [Google Scholar]

- Tajmouati, S.; Wahbi, B. E.; Bedoui, A.; Abarda, A.; Dakkon, M. Applying k-nearest neighbors to time series forecasting: Two new approaches. Journal of Forecasting 2024, 43(5), 1559–1574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, N.; Yao, P.; Zhou, X. Multivariate time series forecast in industrial process based on XGBoost and GRU. In 2020 IEEE 9th Joint International Information Technology and Artificial Intelligence Conference (ITAIC); IEEE, December 2020; Vol. 9, pp. 1397–1400. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, K.; Lin, Q.; Zhou, C.; Yao, J. Time series prediction based on linear regression and SVR. In Third International Conference on Natural Computation (ICNC 2007); IEEE, August 2007; Vol. 1, pp. 688–691. [Google Scholar]

- Bennis, S.; Berrada, F.; Kang, N. Improving single-variable and multivariable techniques for estimating missing hydrological data. Journal of Hydrology 1997, 191(1-4), 87–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullmann, T.; Heinze, G.; Hafermann, L.; Schilhart-Wallisch, C.; Dunkler, D. TG2 of the STRATOS initiative Evaluating variable selection methods for multivariable regression models: A simulation study protocol. Plos one 2024, 19(8), e0308543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semmelmann, L.; Henni, S.; Weinhardt, C. Load forecasting for energy communities: A novel LSTM-XGBoost hybrid model based on smart meter data. Energy Informatics 2022, 5 Suppl 1, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shwartz-Ziv, R.; Armon, A. Tabular data: Deep learning is not all you need. Information Fusion 2022, 81, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochreiter, S. Long Short-term Memory; Neural Computation MIT-Press, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Graves, A.; Schmidhuber, J. Framewise phoneme classification with bidirectional LSTM and other neural network architectures. Neural networks 2005, 18(5-6), 602–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]