1. Introduction

It is well known that hydrogen bonds are the simplest yet most important type of noncovalent bonds in nature. In recent years, in addition to hydrogen bonds, numerous studies have shown that other types of noncovalent bonds, such as halogen bonds and chalcogen bonds, also play a very important role in many scientific fields [

1,

2,

3,

4]. Similar to hydrogen bond, International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) has also recommended definitions for halogen bond and chalcogen bond [

2,

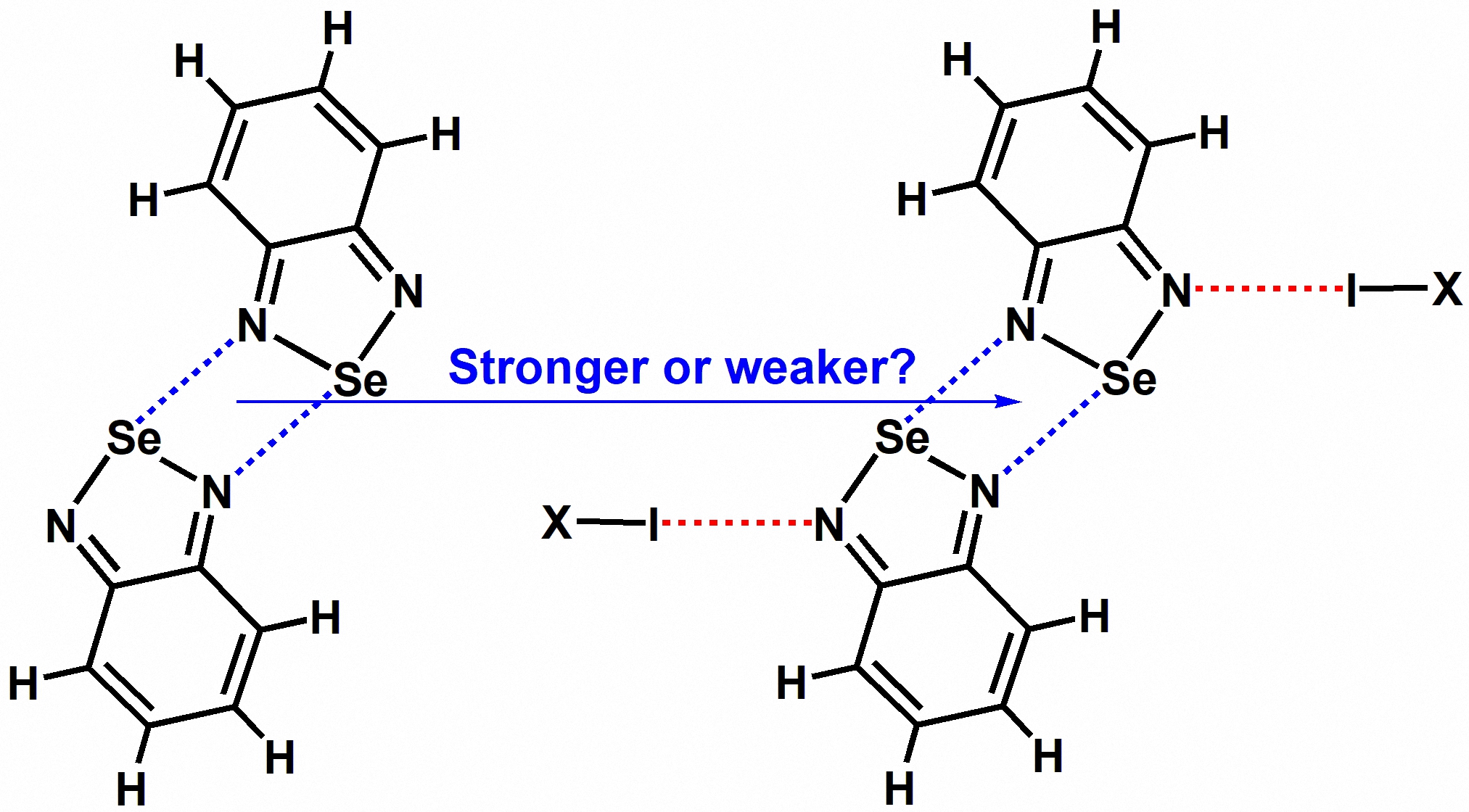

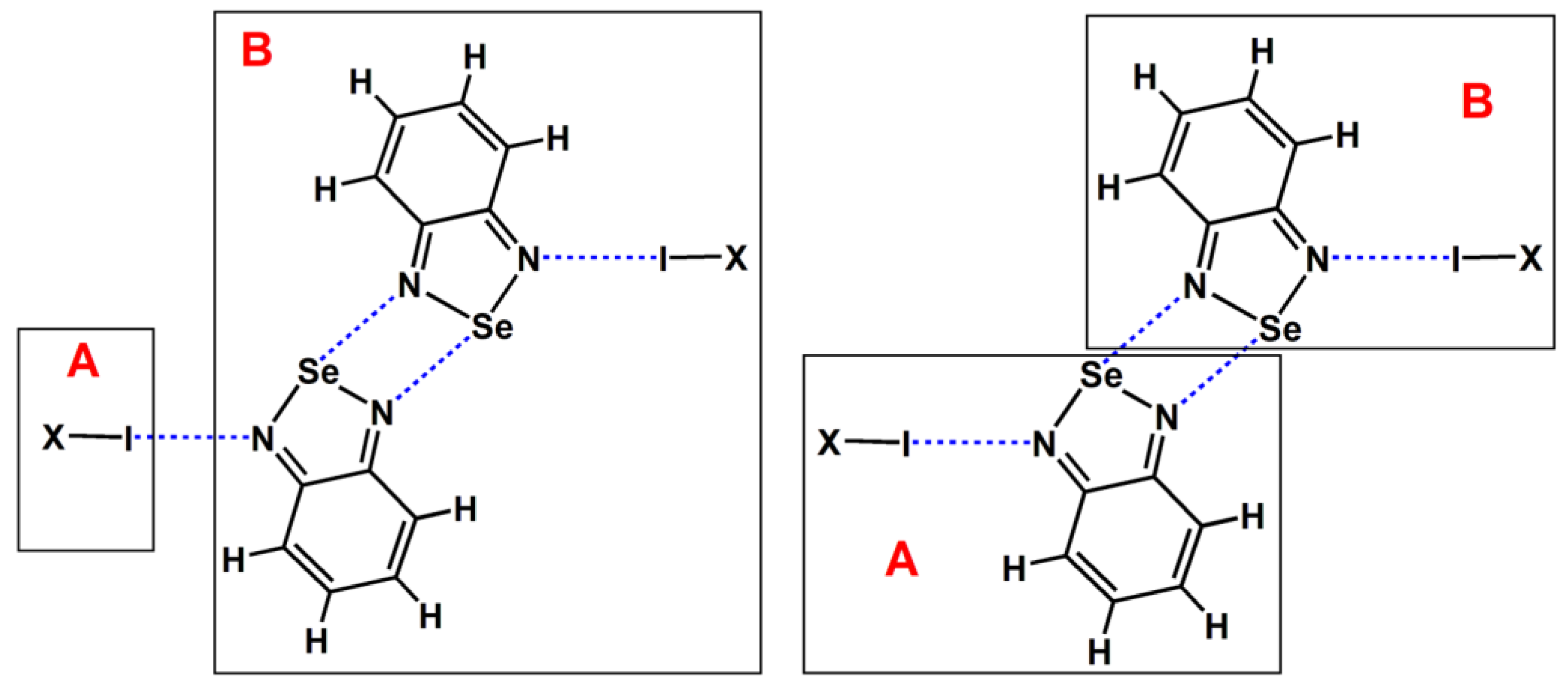

4]. The [Se–N]

2 in

Figure 1 is a cyclic supramolecular synthon assembled from two Se···N chalcogen bonds. The assembly of the two Se···N chalcogen bonds in [Se–N]

2 is stronger than a single Se···N chalcogen bond and has greater potential for applications. The chalcogen-bonded [Se–N]

2 cyclic supramolecular synthon has been used to synthesize many supramolecular architectures with special structures and properties [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13]. One impressive work is the synthesis of a series of supramolecular capsules by Yu and coworkers using the [Se–N]

2 supramolecular synthons [

13]. The supramolecular capsules are very useful because Rebek’s extensive previous work has shown that the chemistry inside supramolecular capsules is very fascinating and exciting [

14]. A search in the Cambridge Structure Database (CSD version 5.45) shows that there are 184 crystal structures which include the [Se–N]

2 supramolecular synthons [

15,

16]. Given the growing interest in chalcogen bonds, we believe that such crystal structures will become more prevalent in the future. At least in this work, we have synthesized five new cocrystals containing the [Se–N]₂ supramolecular synthons.

In addition to experimental investigation, there are also computational studies on the [Se–N]₂ supramolecular synthons [

17,

18,

19,

20,

21]. Lu’s group and Wang’s group conducted detailed computational studies on the effect of different substituents on the [Se–N]₂ supramolecular synthons. If selenadiazole molecules are used to construct the [Se–N]₂ supramolecular synthons, each selenadiazole molecule contains an additional nitrogen atom that can form noncovalent bonds, and this scenario is commonly observed in the crystal structures. Therefore, studying the effect of noncovalent bonds on the [Se–N]₂ supramolecular synthons is just as important as studying the effect of substituents on the [Se–N]₂ supramolecular synthons. On the other hand, studying the cooperativity and competition between different types of noncovalent bonds has long been one of the core aspects of crystal engineering. In this study, we investigated the effect of I···N halogen bonds on the [Se–N]₂ supramolecular synthons in both the gas phase and the crystalline state. We selected 2,1,3-benzoselenadiazole (BSeD) as a representative molecule of selenium-containing diazoles. This is mainly due to two reasons: 1) The complex formed by BSeD molecules and other small molecules is relatively small, making it suitable for high-precision quantum chemical calculations; 2) BSeD can easily form cocrystals with other iodine-containing molecules, making it an ideal molecule for crystallographic studies. Furthermore, in order to test the generality of the conclusions drawn from the [Se–N]₂ supramolecular synthons formed by BSeD, we also studied the [Se–N]₂ supramolecular synthons formed by the fluorine-substituted BSeD, namely 5-fluoro-2,1,3-benzoselenadiazole (F-BSeD).

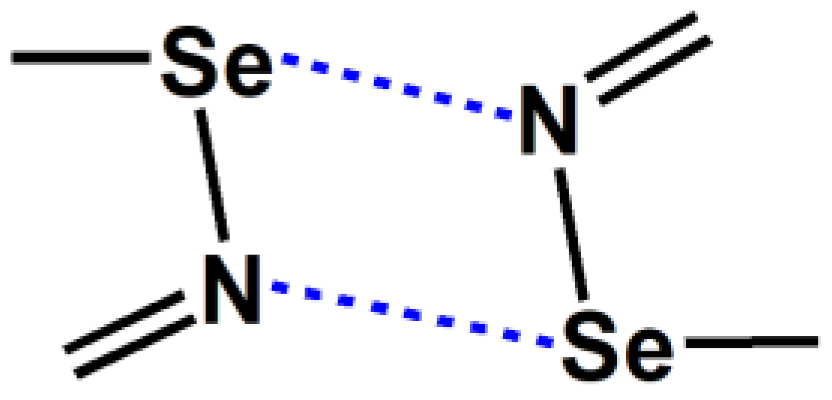

Figure 2 shows the electrostatic potential maps of the monomer BSeD and the dimer I

2···BSeD calculated at the PBE0-D3/def2-TZVPP level of theory [

22,

23,

24]. One Se atom in a BSeD molecule has two σ-holes [

25]. In

Figure 2, the negative electrostatic potential value represents the local minimum in the lone pair electron region of the N atom, and the positive electrostatic potential value represents the local maximum in the σ-hole region of the Se atom. The geometries of BSeD and I

2···BSeD were not optimized and taken directly from the crystal structure of the cocrystal between I

2 and BSeD (CSD refcode GAJQUG) [

7]. By comparing the electrostatic potential maps of BSeD and I₂···BSeD in

Figure 2, it can be seen that the formation of the I···N halogen bond causes the electrostatic potential at the regions of the two σ-holes of the Se atom and the lone pair electrons of the free N atom to become more positive. This aligns with general chemical intuition, as the formation of the I···N halogen bond leads to electron density shifting from the lone pair electrons of the N atom towards the

σ* anti-bonding orbitals of the I–I bond. In other words, the formation of the I···N halogen bond is equivalent to the effect of an electron-withdrawing substituent. However, the positive shift in the electrostatic potential at the region of the Se atom's σ-hole enhances the Se···N chalcogen bond, while the positive shift at the region of the lone pair electrons of the N atom weakens the Se···N chalcogen bond. Therefore, under the effect of the I···N halogen bond, whether the [Se–N]₂ cyclic supramolecular synthon becomes stronger or weaker remains an open question that requires further investigation. This is also the most important issue that this study aims to address in both the gas phase and the crystalline state.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. The Effect of Halogen Bonds on the [Se–N]₂ Supramolecular Synthons in the Gas Phase

We did not conduct experiments related to the gas phase; instead, we used the data from gas-phase quantum chemical calculations to replace the experimental data from the gas phase.

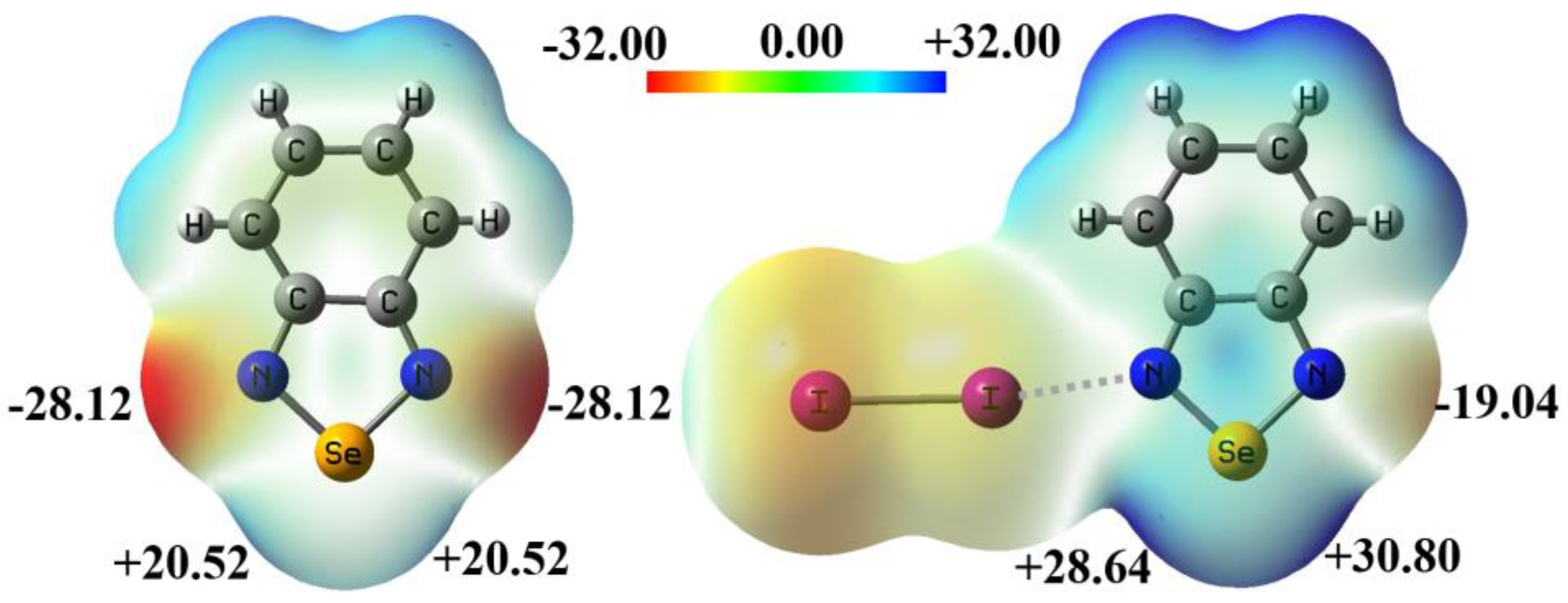

Figure 3 shows the chemical structures of the tetramers studied in this study. In

Figure 3, the molecular formula C

6F

4I

2 represents the 1,4-diiodotetrafluorobenzene molecule and C

6F

3I

3 represents the 1,3,5-trifluoro-2,4,6-triiodobenzene molecule. Except for C

6F

4I

2 and C

6F

3I

3, all the other substances are common small molecules, and their names can be inferred directly from their molecular formulas. The halogen bonds in

Figure 3 can be divided into four types: one type is halogen bonds formed by diatomic halogen molecules; another type is the C(

sp3)–I···N halogen bond; the third type is the C(

sp2)–I···N halogen bond; and the fourth type is the C(

sp)–I···N halogen bond. These four types of halogen bonds are widely representative.

The structures of all the tetramers in

Figure 3 were fully optimized at the PBE0-D3/def2-TZVPP level of theory.

Table 1 summarizes the total interaction energies of the halogen bonds in the tetramers, total interaction energies of the chalcogen bonds in the tetramers and BSeD···BSeD dimers, and dispersion energies of the chalcogen bonds in the tetramers and BSeD···BSeD dimers calculated at the PBE0-D3/def2-TZVPP level of theory. The differences between

(T) and

(D) and between

(T) and

(D) are also listed in

Table 1. Here, the chalcogen bond refers to the [Se–N]₂ cyclic supramolecular synthon, and actually it contains two single Se···N chalcogen bonds. Evidently, the chalcogen bonds in the tetramers are influenced by the I···N halogen bonds, while the chalcogen bonds in the BSeD···BSeD dimers are not influenced by the I···N halogen bonds. Therefore, the difference between

(T) and

(D) clearly reflects the effect of the I···N halogen bonds on the [Se–N]₂ supramolecular synthons. According to the values of

(T)−

(D) in

Table 1, the formation of I···N halogen bonds significantly strengthens the [Se–N]₂ supramolecular synthons.

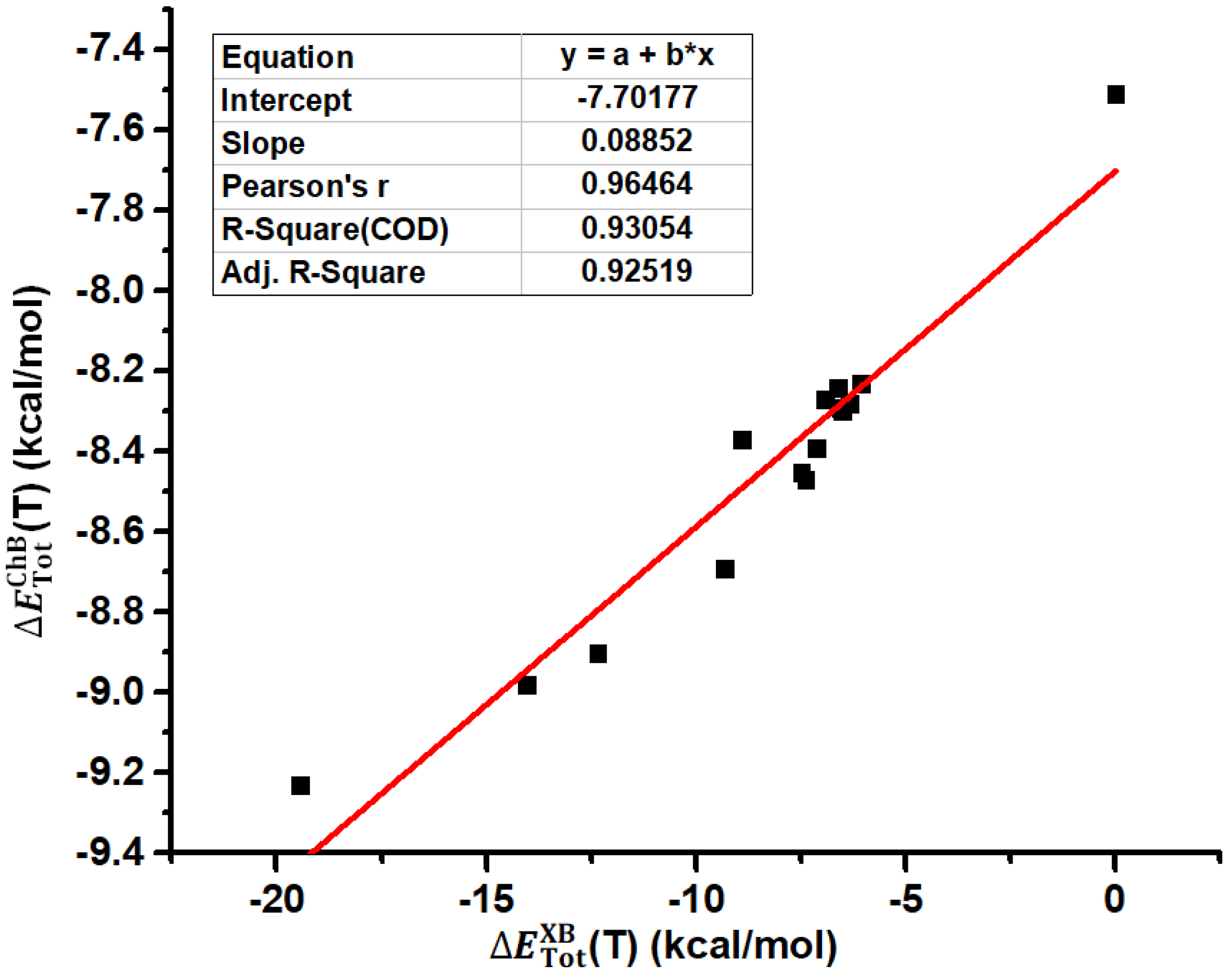

Figure 4 shows the correlation between

(T) and

(T). The total interaction energies of the I···N halogen bonds in the tetramers are positively correlated with the total interaction energies of the [Se–N]₂ cyclic supramolecular synthons in the tetramers, indicating that as the halogen bonds gradually strengthen, the [Se–N]₂ cyclic supramolecular synthons also gradually strengthen. The Pearson correlation coefficient is 0.96464, R-square, which is also known as the coefficient of determination (COD), is 0.93054 and adjusted R-square is 0.92519. Thus, the fitting result is pretty good.

According to symmetry-adapted perturbation theory, the total interaction energy can be divided into four components: electrostatic energy, exchange energy, induction energy, and dispersion energy [

26,

27]. Among them, electrostatic energy, induction energy, and dispersion energy are three attractive components of the total interaction energy. The values of

(T)−

(D) in

Table 1 reflect the contribution of dispersion energy in the process of halogen-bond-enhanced chalcogen bonding. Compared to the values of

(D), the increases in these quantities are almost negligible. Therefore, these computational results suggest that in the process of halogen-bond-enhanced chalcogen bonding, the contribution of dispersion energy is relatively small, with electrostatic and induction energies playing a dominant role. This is consistent with our chemical intuition.

As mentioned earlier, an increase in the electrostatic potential of the Se atom’s σ-hole region enhances the strength of the Se···N chalcogen bond, while an increase in the electrostatic potential of the N atom's lone pair electron region weakens the strength of the Se···N chalcogen bond. Here, the result that the [Se–N]₂ supramolecular synthon becomes stronger under the effect of the I···N halogen bond suggests that the change in the electrostatic potential of the Se atom’s σ-hole region plays a dominant role, while the change in the electrostatic potential of the N atom’s lone pair electron region plays a secondary role.

2.2. The Effect of Halogen Bonds on the [Se–N]₂ Supramolecular Synthons in the Crystalline Phase

In order to study the effect of the I···N halogen bonds on the [Se–N]₂ supramolecular synthons in the crystalline phase, we first conducted a search for the structural motif –I···[Se–N]₂···I– in the Cambridge Structural Database. The results revealed that only five crystal structures contain this structural motif. The refcodes of the five cocrystals are GAJQUG, GAJRER, GAJQIU, MAVHUQ and MAVJIG, respectively [

7,

12]. In the crystal structures of MAVHUQ and MAVJIG, various noncovalent interactions are intertwined, making it difficult to accurately calculate the interaction energies of the I···N halogen bonds and the [Se–N]₂ supramolecular synthons. Ultimately, only three cocrystals—GAJQUG, GAJRER, and GAJQIU—could be used for analysis, resulting in a small sample size. Considering that the structural motif –I···[Se–N]₂···I– is relatively strong, cocrystals assembled through this motif should be easier to synthesize. With BSeD and perfluoroiodobenzenes as the two components, we have also successfully synthesized three additional cocrystals containing this structural motif.

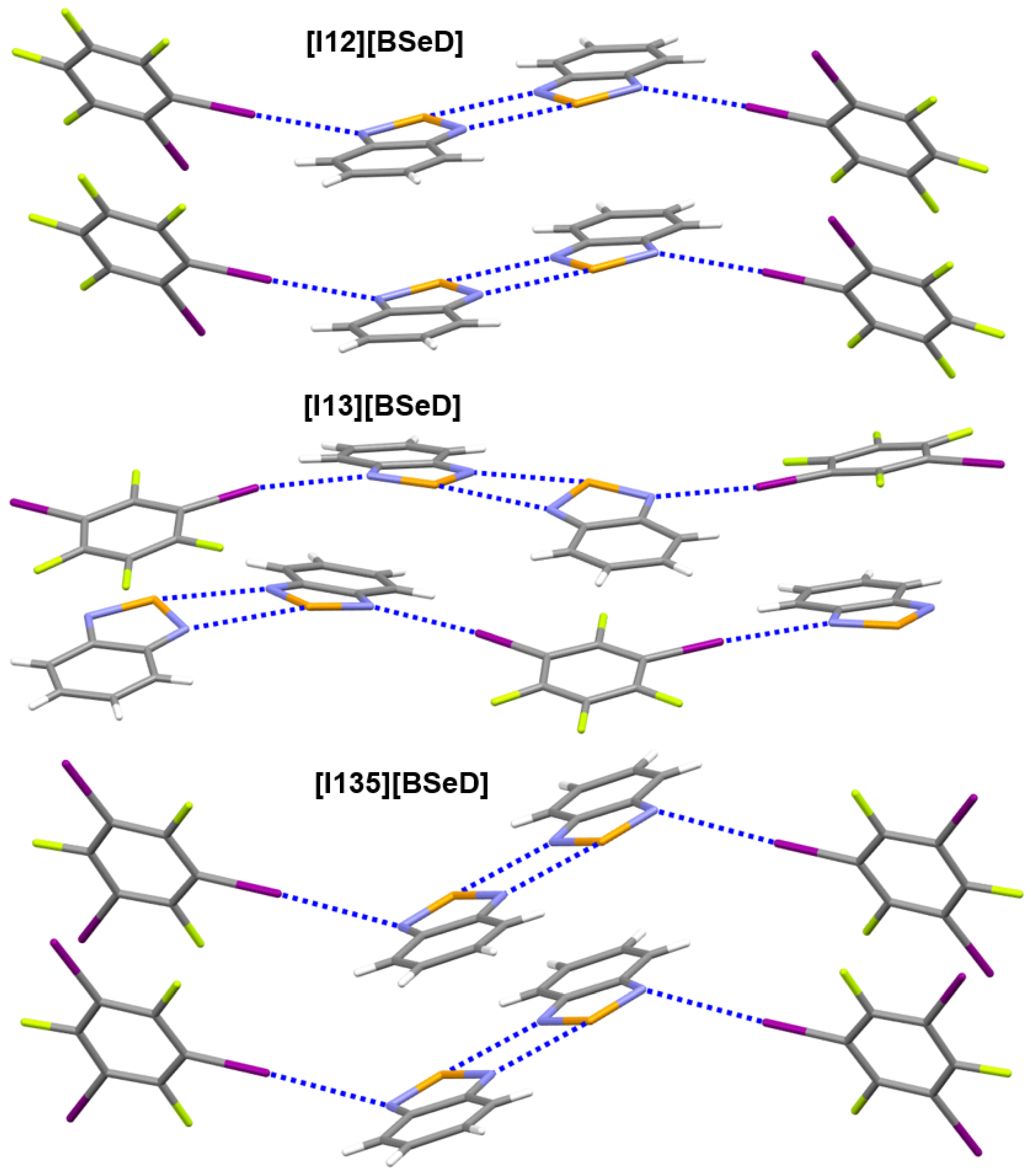

Table 2 lists the crystal and X-ray structure refinement data for the three cocrystals [I12][BSeD], [I13][BSeD] and [I135][BSeD]. Here, I12 represents the 1,2-diiodotetrafluorobenzene molecule, I13 represents the 1,3-diiodotetrafluorobenzene molecule, and I135 represents the 1,3,5-trifluoro-2,4,6-triiodobenzene molecule. The cocrystal [I13][BSeD] is of the orthorhombic crystal system, while the cocrystals [I12][BSeD] and [I135][BSeD] belong to the same crystal system, which is monoclinic.

Figure 5 shows the strong noncovalent interactions in the crystal structures of [

12][BSeD], [

13][BSeD] and [135][BSeD]. Other weak noncovalent interactions in the three crystal structures can be viewed from the crystallographic information files (CIFs) available as

Supplementary Materials. The motif –I···[Se–N]₂···I– exists in each of the three cocrystals. Since the crystal systems of the cocrystals [I12][BSeD] and [I135][BSeD] are the same, the noncovalent interactions in their crystal structures are also very similar. In addition to the I···N halogen bonds and Se···N chalcogen bonds, the crystal structure of [I12][BSeD] also contains π···π stacking interactions between I12 molecules and π···π stacking interactions between BSeD molecules, and the crystal structure of [I135][BSeD] also includes π···π stacking interactions between I135 molecules and π···π stacking interactions between BSeD molecules. In the crystal structure of [I13][BSeD], there are no π···π stacking interactions between I13 molecules, and instead there are π···π stacking interactions between [I13] and [BSeD] molecules. As shown in

Figure 5, in the crystal structures of [I12][BSeD] and [I135][BSeD], the two BSeD molecules forming the [Se–N]₂ supramolecular synthon are almost coplanar. However, in the crystal structure of [I13][BSeD], the two BSeD molecules forming the [Se–N]₂ supramolecular synthon exhibit a certain torsion angle and are not coplanar. The comparison of noncovalent interactions in these three crystals shows that the intermolecular π···π stacking interactions determine whether the two BSeD molecules that form the [Se–N]₂ supramolecular synthon lie in the same plane or not.

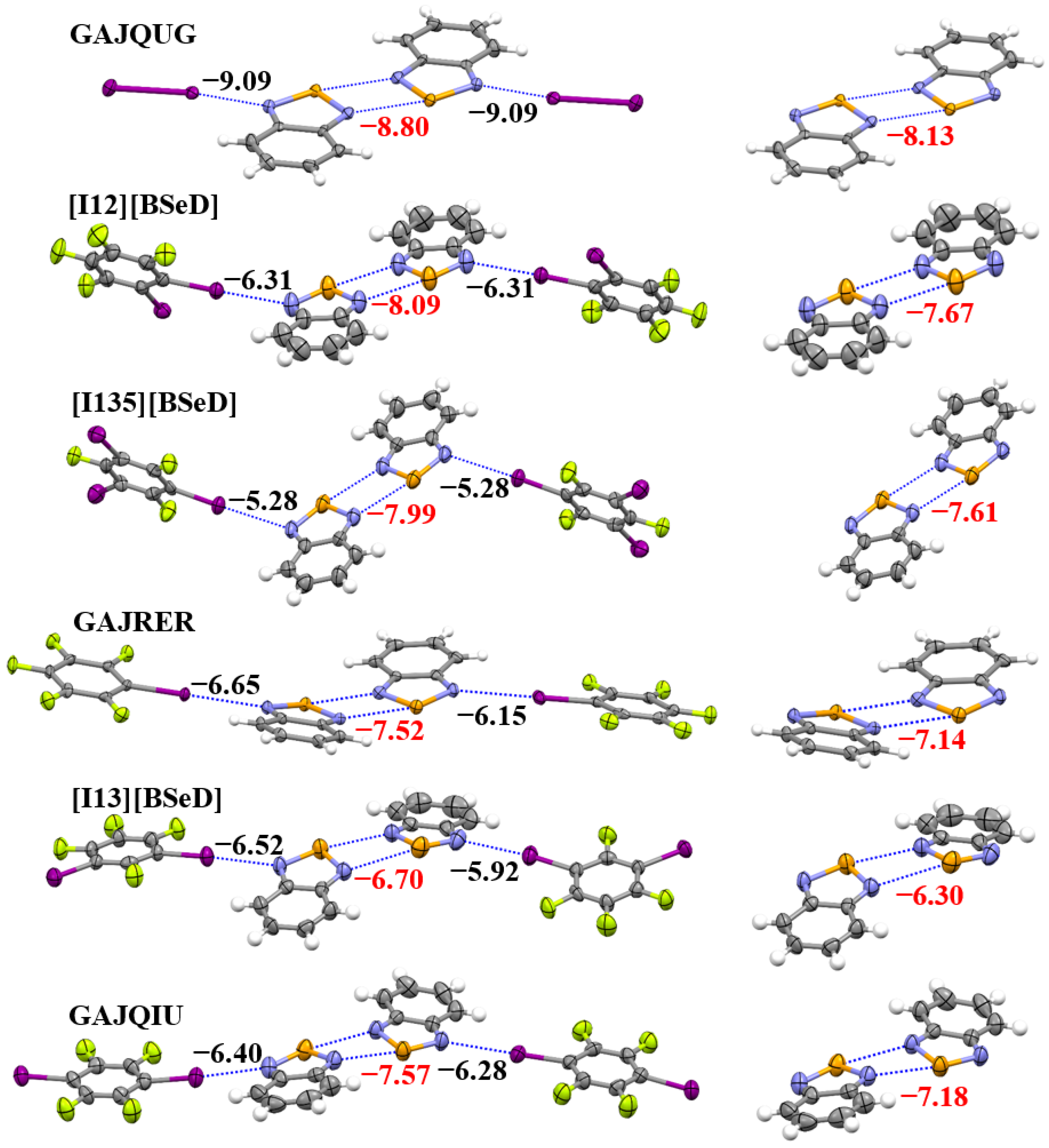

Figure 6 shows the tetramers (left) and dimers (right) in the crystal structures of GAJQUG, [I12][BSeD], [I135][BSeD], GAJRER, [I13][BSeD] and GAJQIU, along with the interaction energies of the I···N halogen bonds and [Se–N]₂ supramolecular synthons calculated at the PBE0-D3/def2-TZVPP level of theory. Although the introduction of I···N halogen bonds enhances the [Se–N]₂ supramolecular synthons, stronger I···N halogen bonds do not lead to stronger [Se–N]₂ supramolecular synthons. For example, the I···N halogen bonds in the crystal structure of [I135][BSeD] are weaker than the I···N halogen bonds in the crystal structures of GAJRER, [I13][BSeD] and GAJQIU, while the [Se–N]₂ supramolecular synthon in the [I135][BSeD] crystal structure is stronger than the [Se–N]₂ supramolecular synthons in the crystal structures of GAJRER, [I13][BSeD] and GAJQIU. However, such a conclusion requires further analysis. As can be seen from

Figure 6, the two I···N halogen bonds in each of the crystal structures of GAJQUG, [I12][BSeD] and [I135][BSeD] are symmetric, with the two BSeD molecules forming the [Se–N]₂ supramolecular synthon almost lying in the same plane. In contrast, the two I···N halogen bonds in each of the crystal structures of GAJRER, [I13][BSeD] and GAJQIU are asymmetric, and the two BSeD molecules forming the [Se–N]₂ supramolecular synthon are not in the same plane. This difference is clearly due to the effect of other noncovalent interactions in the crystal structures. Only the comparison of noncovalent bonds in the crystal structures of the three cocrystals, GAJQUG, [I12][BSeD] and [I135][BSeD], is meaningful. Although the sample size is small, with only three crystals, we can still draw two conclusions: (1) The introduction of the I···N halogen bonds strengthens the [Se–N]₂ supramolecular synthon; (2) As the I···N halogen bonds become stronger, the strength of the [Se–N]₂ supramolecular synthon also increases, showing a proportional relationship. This is consistent with the results in the gas phase.

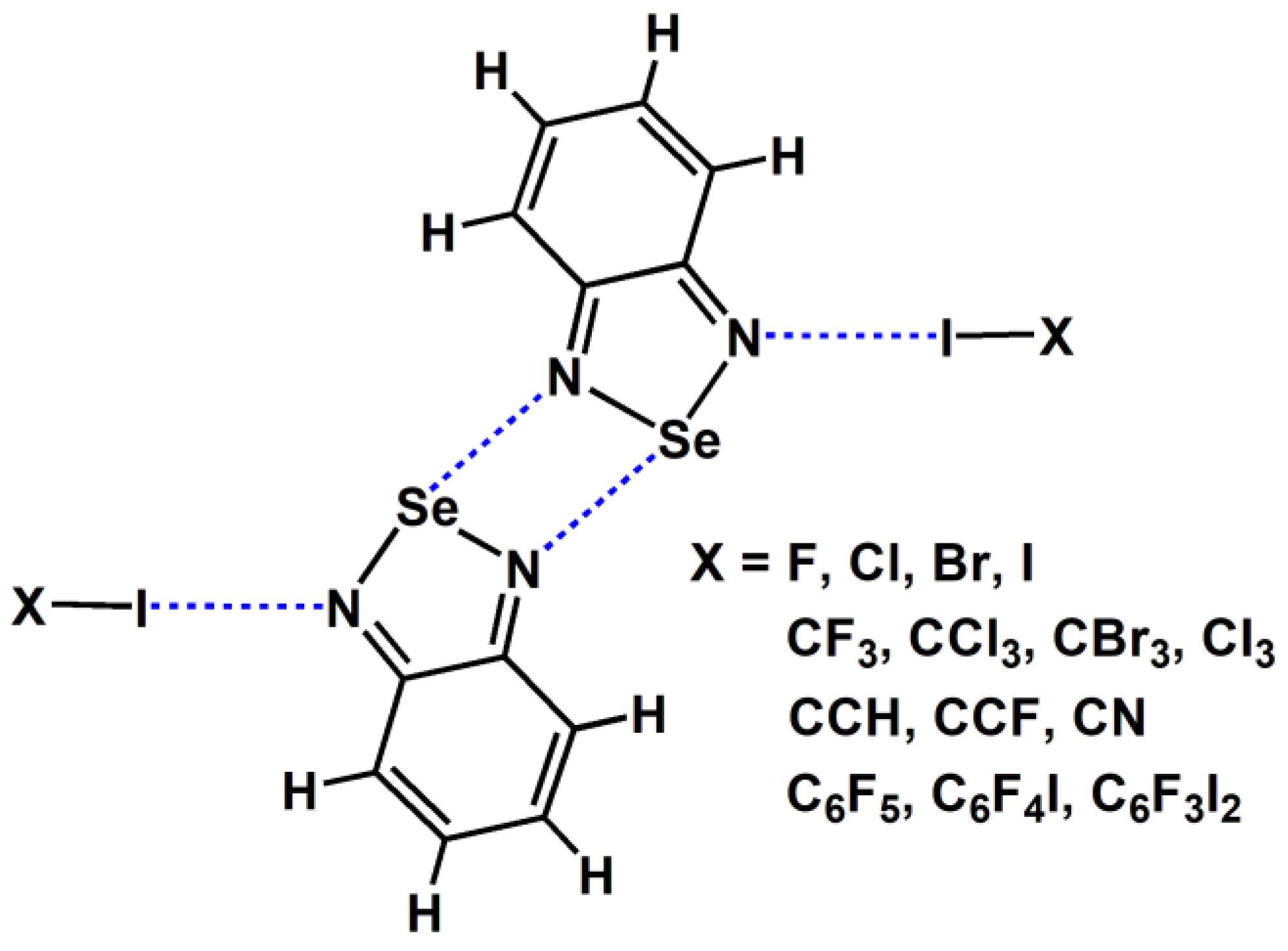

2.3. Expansion of the [Se–N]₂ Supramolecular Synthon

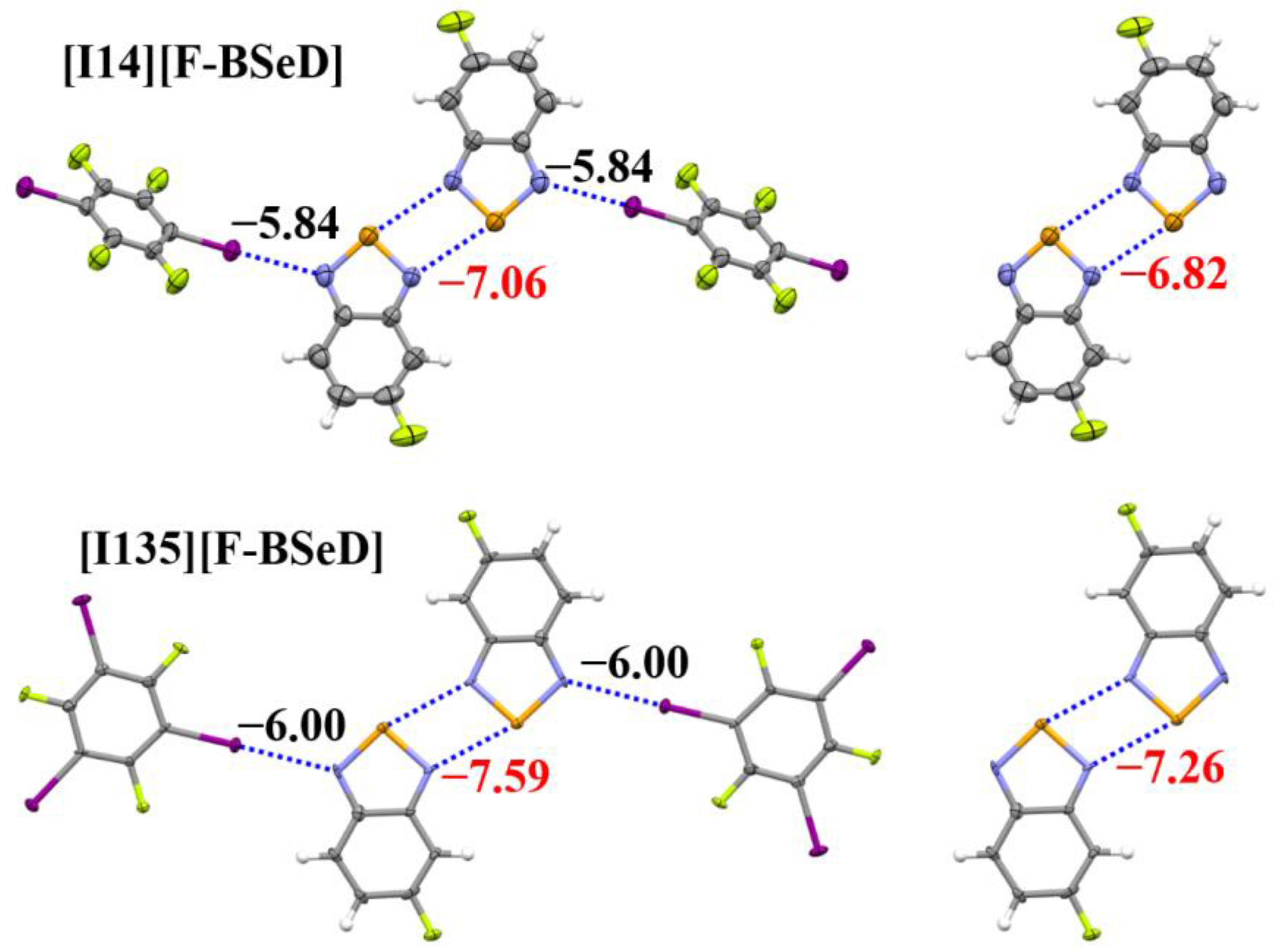

In the previous text, we selected BSeD as a representative molecule of selenadiazole to study the effect of I···N halogen bonds on the [Se–N]₂ supramolecular synthons. If BSeD were replaced with other selenadiazole molecules, the conclusions obtained should, in principle, remain the same. To verify this hypothesis, we tried to synthesize the cocrystals formed by F-BSeD with I2, I12, I13, 1,4-diiodotetrafluorobenzene (I14) and I135, respectively. Finally, only two cocrystals [I14][F-BSeD] and [I135][F-BSeD] were successfully synthesized and resolved. Similarly, the effect of I···N halogen bonds on the [Se–N]₂ supramolecular synthons formed by the F-BSeD molecule was studied.

Table 3 summarizes the crystal and X-ray structure refinement data for the two cocrystals [I14][F-BSeD] and [I135][F-BSeD]. The cif files of [I14][F-BSeD] and [I135][F-BSeD] have been given in the

Supplementary Materials. The crystal structures of [I14][F-BSeD] and [I135][F-BSeD] both belong to the monoclinic system. The noncovalent interactions in the crystal structures of [I14][F-BSeD] and [I135][F-BSeD] are also very similar. In addition to the I···N halogen bonds and Se···N chalcogen bonds that we focus on, there are also π···π stacking interactions between the F-BSeD molecules and π···π stacking interactions between F-BSeD and I14/I135 molecules.

Figure 7 shows the tetramers studied in the crystal structures of [I14][F-BSeD] and [I135][F-BSeD], along with the corresponding dimers for comparison. Both the tetramer and dimer are symmetrical structures. Meanwhile, the two F-BSeD molecules that form the [Se–N]₂ supramolecular synthons are approximately in the same plane. The interaction energies of the I···N halogen bonds and [Se–N]₂ supramolecular synthons are also shown in

Figure 7. The interaction energy from the dimer to the tetramer indicates that the formation of I···N halogen bonds strengthens the [Se–N]₂ supramolecular synthons. Additionally, by comparing the interaction energies of the tetramers in the crystal structures of [I14][F-BSeD] and [I135][F-BSeD], we observe that as the I···N halogen bonds strengthen, the [Se–N]₂ supramolecular synthons also become stronger, with a proportional relationship between the ···N halogen bonds and [Se–N]₂ supramolecular synthons. These results are consistent with the corresponding findings for the [Se–N]₂ supramolecular synthons formed by BSeD, confirming our hypothesis. Furthermore, it is believed that the conclusions drawn in this paper are also applicable to the [Se–N]₂ supramolecular synthons formed by other selenadiazoles or their derivatives.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Computational Details

In the gas phase, the geometries of the tetramers were fully optimized at the PBE0-D3/def2-TZVPP level of theory [

22,

23,

24]. In the crystalline phase, the geometries of the tetramers were not optimized and taken directly from the crystal structures. For comparison, the PBE0-D3/def2-TZVPP calculations of the dimers used their corresponding geometries in the tetramers. The electrostatic potentials and interaction energies were calculated also at the PBE0-D3/def2-TZVPP theory level. Our previous studies have confirmed the reliability of the PBE0-D3/def2-TZVPP calculations for accurately describing the noncovalent interactions [

28,

29,

30]. In fact, the PBE0-D3/def2-TZVPP calculations were often used in the study of noncovalent interactions in crystal structures [

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36]. The electrostatic potential maps were plotted on the 0.001 au electron density isosurfaces. All the interaction energies have been corrected for basis set superposition error by using the counterpoise scheme of Boys and Bernardi [

37]. The interaction energies (∆

E) were calculated with the supermolecule method. The calculation formula is as follows:

where

EAB is the energy of the complex AB,

EA is the energy of fragment A, and

EB is the energy of fragment B. Therefore, in order to calculate the interaction energies of the I···N halogen bonds and [Se–N]₂ supramolecular synthons in the tetramers, each of the tetramers was separated into its fragment A and fragment B subunits (see

Figure 8). Note that we only illustrate the division of the tetramer formed by BSeD in

Figure 8. The division method for the tetramer formed by F-BSeD is the same. The dispersion energy was calculated as the difference between PBE0-D3/def2-TZVPP interaction energy and HF/def2-TZVPP interaction energy. All the calculations were performed with the Gaussian 16 suite of programs [

38].

3.2. Syntheses of Cocrystals

I12 (purity: ≥98%), I13 (purity: ≥98%), I14 (purity: ≥98%) and I135 (purity: ≥98%) were purchased from J&K Scientific Ltd., Beijing, China. BSeD (purity: ≥98%) and F-BSeD (purity: ≥98%) were purchased from Alfa Chemical Co., Ltd., Zhengzhou, China. The solvents (analytical reagent grade) were purchased from local suppliers. All reagents and solvents were used without further purification. The synthesis steps for the five cocrystals [I12][BSeD], [I13][BSeD], [I135][BSeD], [I14][F-BSeD], and [I135][F-BSeD] are the same. We weigh 0.1 mmol of halogen-bond donor (I12, I13, I14 or I135) and 0.1 mmol of the corresponding halogen-bond acceptor (BSeD or F-BSeD), and dissolve them in 10 mL of chloroform solvent. The solution is gently stirred for 30 minutes, then filtered. The filtrate is allowed to slowly evaporate at room temperature, and after 2-3 days, single crystals suitable for X-ray diffraction measurements are obtained. In fact, we also attempted to synthesize other cocrystals of the same series. Since the attempts were unsuccessful, the synthesis details will not be reiterated here.

3.3. X-Ray Structure Determinations

Single-crystal X-ray diffraction data were collected on the Oxford Diffraction SuperNova area-detector diffractometer equipped with the Mo-Kα X-ray source (λ = 0.71073 Å). The cell refinements and data reduction were carried out by using CrysAlisPro software package [

39]. The crystal structure was solved with the ShelXT and ShelXL programs [

40,

41]. The H atoms in all structures were refined at idealized positions riding on the C atoms, with isotropic displacement parameters

Uiso(H) = 1.2

Ueq(C) and

d(C–H) = 0.93 Å. The CIF files of the five cocrystals (CCDC deposition numbers: 2239822-2239824, 2417680, 2417681) can be obtained free of charge via

https://www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/structures/. At the same time, the CIF files of the five cocrystals were also provided as the electronic supplementary materials. The checkcif files for the five cocrystal structures can be found in the

Supplementary Materials.

4. Conclusions

The [Se–N]₂ supramolecular synthon is one of the most important synthons formed by chalcogen bonds in the field of supramolecular chemistry. In this study, the effect of the I···N halogen bonds on the [Se–N]₂ supramolecular synthons has been investigated in detail by means of a combined theoretical calculation and single-crystal X-ray crystallographic experiment approach.

The results of the gas-phase calculations show that the formation of I···N halogen bonds significantly strengthens the [Se–N]₂ supramolecular synthons. At the same time, as the I···N halogen bonds strengthen, the [Se–N]₂ supramolecular synthons also increase, and there is a very good correlation between the I···N halogen bonds and [Se–N]₂ supramolecular synthons. Due to the effect of other noncovalent interactions, the relationship between I···N halogen bonds and [Se–N]₂ supramolecular synthons in the crystal structure is relatively more complex. However, if the effect of other noncovalent interactions is relatively small, the strength of halogen bond remains directly proportional to the strength of [Se–N]₂ supramolecular synthons.

Now, we can provide a clear answer to the question raised in the introduction section. That is, the positive shift in the electrostatic potential at the region of the Se atom's σ-hole, which leads to the enhancement of the [Se–N]₂ supramolecular synthon, plays a dominant role, while the positive shift at the region of the lone pair electrons of the N atom, which weakens the [Se–N]₂ supramolecular synthon, plays a secondary role. At the same time, our study also finds that, during the process in which I···N halogen bonds enhance the [Se–N]₂ supramolecular synthons, dispersion energy plays a secondary role, with electrostatic energy and induction energy dominating. This is consistent with our chemical intuition.

We also extended the [Se–N]₂ supramolecular synthons formed by BSeD to those formed by F-BSeD and found that the positive correlation between I···N halogen bonds and [Se–N]₂ supramolecular synthons still holds. If the I···N halogen bonds are replaced with other types of noncovalent interactions, such as hydrogen bonds and chalcogen bonds, we believe that the conclusions of this study would still hold.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

S.M. synthesized the cocrystals and determined their X-ray crystal structures; X.S. and Y.Z. performed the calculations; W.W. designed and supervised this project; S.M., X.S., Y.Z. and W.W. wrote and revised the paper. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Please add: This research was funded by the Natural Science Foundation of Henan Province of China, grant number 232300421147. The APC was funded by 232300421147.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available on request from the authors.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Natural Science Foundation of Henan Province of China for the financial support. W.W. thanks the National Supercomputing Center in Shenzhen for the computational support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Cavallo, G.; Metrangolo, P.; Milani, R.; Pilati, T.; Priimagi, A.; Resnati, G.; Terraneo, G. The Halogen Bond. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 2478–2601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desiraju, G.R.; Ho, P.S.; Kloo, L.; Legon, A.C.; Marquardt, R.; Metrangolo, P.; Politzer, P.; Resnati, G.; Rissanen, K. Definition of the Halogen Bond. Pure Appl. Chem. 2013, 85, 1711–1713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Ji, B.; Zhang, Y. Chalcogen Bond: A Sister Noncovalent Bond to Halogen Bond. J. Phys. Chem. A 2009, 113, 8132–8135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aakeroy, C.B.; Bryce, D.L.; Desiraju, G.R.; Frontera, A.; Legon, A.C.; Nicotra, F.; Rissanen, K.; Scheiner, S.; Terraneo, G.; Metrangolo, P.; Resnati, G. Definition of the Chalcogen Bond. Pure Appl. Chem. 2019, 91, 1889–1892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondal, S.; Konda, M.; Kauffmann, B.; Manna, M.K.; Das, A.K. Effects of Donor and Acceptor Units Attached with Benzoselenadiazole: Optoelectronic and Self-Assembling Patterns. Cryst. Growth Des. 2015, 15, 5548–5554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, L.M.; Corless, V.B.; Tran, M.; Jenkins, H.; Britten, J.F.; Vargas-Baca, I. Synthetic, Structural, and Computational Investigations of N-alkyl Benzo-2,1,3-selenadiazolium Iodides and Their Supramolecular Aggregates. Dalton Trans. 2016, 45, 3285–3293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eichstaedt, K.; Wasilewska, A.; Wicher, B.; Gdaniec, M.; Połoński, T. Supramolecular Synthesis Based on a Combination of Se···N Secondary Bonding Interactions with Hydrogen and Halogen Bonds. Cryst. Growth Des. 2016, 16, 1282–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lekin, K.; Leitch, A.A.; Assoud, A.; Yong, W.; Desmarais, J.; Tse, J.S.; Desgreniers, S.; Secco, R.A.; Oakley, R.T. Benzoquinone-Bridged Heterocyclic Zwitterions as Building Blocks for Molecular Semiconductors and Metals. Inorg. Chem. 2018, 57, 4757–4770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centore, R.; Borbone, F.; Carella, A.; Causà, M.; Fusco, S.; Gentile, F.S.; Parisi, E. Hierarchy of Intermolecular Interactions and Selective Topochemical Reactivity in Different Polymorphs of Fused-Ring Heteroaromatics. Cryst. Growth Des. 2020, 20, 1229–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biot, N.; Bonifazi, D. Concurring Chalcogen- and Halogen-Bonding Interactions in Supramolecular Polymers for Crystal Engineering Applications. Chem. Eur. J. 2020, 26, 2904–2913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tiekink, E.R.T. Supramolecular Aggregation Patterns Featuring Se⋯N Secondary-Bonding Interactions in Mono-Nuclear Selenium Compounds: A Comparison with Their Congeners. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2021, 443, 214031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfuth, J.; Zadykowicz, B.; Wicher, B.; Kazimierczuk, K.; Połoński, T.; Olszewska, T. Cooperativity of Halogen- and Chalcogen-Bonding Interactions in the Self-Assembly of 4-Iodoethynyl- and 4,7-Bis(iodoethynyl)benzo-2,1,3-chalcogenadiazoles: Crystal Structures, Hirshfeld Surface Analyses, and Crystal Lattice Energy Calculations. Cryst. Growth Des. 2022, 22, 1299–1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, F.-U.; Tzeli, D.; Petsalakis, I.D.; Theodorakopoulos, G.; Ballester, P.; Rebek, J., Jr.; Yu, Y. Chalcogen Bonding and Hydrophobic Effects Force Molecules into Small Spaces. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 5876–5883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Y.; Rebek, J., Jr. Confined Molecules: Experiment Meets Theory in Small Spaces. Q. Rev. Biophys. 2020, 53, e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allen, F. The Cambridge Structure Database: A Quarter of a Million Crystal Structures and Rising. Acta Crystallogr. 2002, B58, 380–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, F. , Motherwell, W.D.S. Applications of the Cambridge Structural Database in Organic and Crystal Chemistry. Acta Crystallogr. 2002, B58, 407–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, Y.; Li, W.; Yang, W.; Zhu, Z.; Xu, Z.; Liu, H. 2Ch–2N Square and Hexagon Interactions: A Combined Crystallographic Data Analysis and Computational Study. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2019, 21, 21568–21576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalczyk, M.; Malik, M.; Zierkiewicz, W.; Scheiner, S. Experimental and Theoretical Studies of Dimers Stabilized by Two Chalcogen Bonds in the Presence of a N···N Pnicogen Bond. J. Phys. Chem. A 2021, 125, 657–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scheiner, S. Principles Guiding the Square Bonding Motif Containing a Pair of Chalcogen Bonds between Chalcogenadiazoles. J. Phys. Chem. A 2022, 126, 1194–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Li, B.; Wang, X.; Yin, F.; Wei, Q.; Wang, X.; Ni, Y.; Wang, H. First-Principles Study of Square Chalcogen Bond Interactions and its Adsorption Behavior on Silver Surface. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2023, 25, 10836–10844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radiush, E.A.; Wang, H.; Chulanova, E.A.; Ponomareva, Y.A.; Li, B.; Wei, Q.Y.; Salnikov, G.E.; Petrakova, S.Y.; Semenov, N.A.; Zibarev, A.V. Halide Complexes of 5,6-Dicyano-2,1,3-Benzoselenadiazole with 1:4 Stoichiometry: Cooperativity between Chalcogen and Hydrogen Bonding. ChemPlusChem 2023, 88, e202300523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamo, C.; Barone, V. Toward Reliable Density Functional Methods without Adjustable Parameters: The PBE0 Model. J. Chem. Phys. 1999, 110, 6158–6169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimme, S.; Antony, J.; Ehrlich, S.; Krieg, H. A Consistent and Accurate Ab Initio Parametrization of Density Functional Dispersion Correction (DFT-D) for the 94 Elements H-Pu. J. Chem. Phys. 2010, 132, 154104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grimme, S.; Ehrlich, S.; Goerigk, L. Effect of the Damping Function in Dispersion Corrected Density Functional Theory. J. Comput. Chem. 2011, 32, 1456–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, J.S.; Lane, P.; Clark, T.; Politzer, P. σ-Hole bonding: Molecules containing group VI atoms. J. Mol. Model. 2007, 13, 1033–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeziorski, B.; Moszyński, R.; Szalewicz, K. Perturbation Theory Approach to Intermolecular Potential Energy Surfaces of van der Waals Complexes. Chem. Rev. 1994, 94, 1887–1930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szalewicz, K. Symmetry-Adapted Perturbation Theory of Intermolecular Forces. WIREs Comput. Mol. Sci. 2012, 2, 254–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Sun, T.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.B. The Benzene⋯Naphthalene Complex: A More Challenging System Than the Benzene Dimer for Newly Developed Computational Methods. J. Chem. Phys. 2015, 143, 114312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.M.; Wang, Y.B.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, W. The Nature of the Noncovalent Interactions between Benzene and C60 Fullerene. J. Phys. Chem. A 2016, 120, 5766–5772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.B. Highly Accurate Benchmark Calculations of the Interaction Energies in the Complexes C6H6⋯C6X6 (X = F, Cl, Br, and I). Int. J. Quantum Chem. 2017, 117, e25345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolari, K.; Sahamies, J.; Kalenius, E.; Novikov, A.S.; Kukushkin, V.Y.; Haukka, M. Metallophilic Interactions in Polymeric Group 11 Thiols. Solid State Sci. 2016, 60, 92–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikherdov, A.S.; Novikov, A.S.; Kinzhalov, M.A.; Zolotarev, A.A.; Boyarskiy, V.P. Intra-/Intermolecular Bifurcated Chalcogen Bonding in Crystal Structure of Thiazole/Thiadiazole Derived Binuclear (Diaminocarbene)PdII Complexes. Crystals 2018, 8, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eliseeva, A.A.; Ivanov, D.M.; Novikov, A.S.; Kukushkin, V.Y. Recognition of the π-Hole Donor Ability of Iodopentafluorobenzene—A Conventional σ-Hole Donor for Crystal Engineering Involving Halogen Bonding. CrystEngComm 2019, 21, 616–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katkova, S.A.; Mikherdov, A.S.; Kinzhalov, M.A.; Novikov, A.S.; Zolotarev, A.A.; Boyarskiy, V.P.; Kukushkin, V.Y. (Isocyano Group π-Hole)⋯[dz2-MII] Interactions of (Isocyanide)[MII] Complexes, in which Positively Charged Metal Centers (d8-M=Pt, Pd) Act as Nucleophiles. Chem. Eur. J. 2019, 25, 8590–8598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nenajdenko, V.G.; Shikhaliyev, N.G.; Maharramov, A.M.; Bagirova, K.N.; Suleymanova, G.T.; Novikov, A.S.; Khrustalev, V.N.; Tskhovrebov, A.G. Halogenated Diazabutadiene Dyes: Synthesis, Structures, Supramolecular Features, and Theoretical Studies. Molecules 2020, 25, 5013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baykov, S.V.; Katlenok, E.A.; Baykova, S.O.; Semenov, A.V.; Bokach, N.A.; Boyarskiy, V.P. Conformation-Associated C···dz2-PtII Tetrel Bonding: The Case of Cyclometallated Platinum(II) Complex with 4-Cyanopyridyl Urea Ligand. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 4052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boys, S.F.; Bernardi, F. The Calculation of Small Molecular Interactions by the Difference of Separate Total Energies. Some Procedures with Reduced Errors. Mol. Phys. 1970, 19, 553–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frisch, M.J.; Trucks, G.W.; Schlegel, H.B.; Scuseria, G.E.; Robb, M.A.; Cheeseman, J.R.; Scalmani, G.; Barone, V.; Petersson, G.A.; Nakatsuji, H.; Li, X.; Caricato, M.; Marenich, A.V.; Bloino, J.; Janesko, B.G.; Gomperts, R.; Mennucci, B.; Hratchian, H.P.; Ortiz, J.V.; Izmaylov, A.F.; Sonnenberg, J.L.; Williams-Young, D.; Ding, F.; Lipparini, F.; Egidi, F.; Goings, J.; Peng, B.; Petrone, A.; Henderson, T.; Ranasinghe, D.; Zakrzewski, V.G.; Gao, J.; Rega, N.; Zheng, G.; Liang, W.; Hada, M.; Ehara, M.; Toyota, K.; Fukuda, R.; Hasegawa, J.; Ishida, M.; Nakajima, T.; Honda, Y.; Kitao, O.; Nakai, H.; Vreven, T.; Throssell, K.; Montgomery, J.A., Jr.; Peralta, J.E.; Ogliaro, F.; Bearpark, M.J.; Heyd, J.J.; Brothers, E.N.; Kudin, K.N.; Staroverov, V.N.; Keith, T.A.; Kobayashi, R.; Normand, J.; Raghavachari, K.; Rendell, A.P.; Burant, J.C.; Iyengar, S.S.; Tomasi, J.; Cossi, M.; Millam, J.M.; Klene, M.; Adamo, C.; Cammi, R.; Ochterski, J.W.; Martin, R.L.; Morokuma, K.; Farkas, O.; Foresman, J.B.; Fox, D.J. Gaussian~16 Revision C.01; Gaussian Inc.: Wallingford, CT, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Rikagu Oxford Diffraction. CrysAlisPro; Rikagu Oxford Diffraction Inc.: Yarnton, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Sheldrick, G.M. SHELXT–Integrated Space-Group and Crystal-Structure Determination. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. A Found. Adv. 2015, 71, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheldrick, G.M. Crystal Structure Refinement with SHELXL. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. C Struct. Chem. 2015, 71, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

The chalcogen-bonded [Se–N]2 cyclic supramolecular synthon.

Figure 1.

The chalcogen-bonded [Se–N]2 cyclic supramolecular synthon.

Figure 2.

The electrostatic potential (in kcal/mol) maps of BSeD and I2···BSeD. The values represent the locally most positive or most negative electrostatic potential.

Figure 2.

The electrostatic potential (in kcal/mol) maps of BSeD and I2···BSeD. The values represent the locally most positive or most negative electrostatic potential.

Figure 3.

The chemical structures of the tetramers studied in this study.

Figure 3.

The chemical structures of the tetramers studied in this study.

Figure 4.

Correlation between (T) and (T).

Figure 4.

Correlation between (T) and (T).

Figure 5.

The strong noncovalent interactions in the crystal structures of [

12][BSeD], [

13][BSeD] and [135][BSeD]. Color code: H, white; C, gray; N, blue; F, yellow green; Se, orange; I, purple.

Figure 5.

The strong noncovalent interactions in the crystal structures of [

12][BSeD], [

13][BSeD] and [135][BSeD]. Color code: H, white; C, gray; N, blue; F, yellow green; Se, orange; I, purple.

Figure 6.

The PBE0-D3/def2-TZVPP interaction energies of the I···N halogen bonds and [Se–N]₂ supramolecular synthons in the crystal structures of six studied cocrystals. Color code: H, white; C, gray; N, blue; F, yellow green; Se, orange; I, purple.

Figure 6.

The PBE0-D3/def2-TZVPP interaction energies of the I···N halogen bonds and [Se–N]₂ supramolecular synthons in the crystal structures of six studied cocrystals. Color code: H, white; C, gray; N, blue; F, yellow green; Se, orange; I, purple.

Figure 7.

The PBE0-D3/def2-TZVPP interaction energies of the I···N halogen bonds and [Se–N]₂ supramolecular synthons in the crystal structures of [I14][F-BSeD] and [I135][F-BSeD]. Color code: H, white; C, gray; N, blue; F, yellow green; Se, orange; I, purple.

Figure 7.

The PBE0-D3/def2-TZVPP interaction energies of the I···N halogen bonds and [Se–N]₂ supramolecular synthons in the crystal structures of [I14][F-BSeD] and [I135][F-BSeD]. Color code: H, white; C, gray; N, blue; F, yellow green; Se, orange; I, purple.

Figure 8.

The division of fragment A and fragment B for the calculations of the I···N halogen bonds and [Se–N]₂ supramolecular synthons in the tetramers.

Figure 8.

The division of fragment A and fragment B for the calculations of the I···N halogen bonds and [Se–N]₂ supramolecular synthons in the tetramers.

Table 1.

Total interaction energies of the halogen bonds in the tetramers ((T)), total interaction energies of the chalcogen bonds in the tetramers and BSeD···BSeD dimers ((T) and (D)), and dispersion energies of the chalcogen bonds in the tetramers and BSeD···BSeD dimers ((T) and (D)) calculated at the PBE0-D3/def2-TZVPP level of theory. All energies are in kcal/mol.

Table 1.

Total interaction energies of the halogen bonds in the tetramers ((T)), total interaction energies of the chalcogen bonds in the tetramers and BSeD···BSeD dimers ((T) and (D)), and dispersion energies of the chalcogen bonds in the tetramers and BSeD···BSeD dimers ((T) and (D)) calculated at the PBE0-D3/def2-TZVPP level of theory. All energies are in kcal/mol.

| Tetramer |

(T) |

(T) |

(D) |

(D) |

(T) |

(D) |

(D) |

| FI···BSeD···BSeD···FI |

−19.44 |

−9.23 |

−8.51 |

−0.72 |

−9.60 |

−9.46 |

−0.14 |

ClI···BSeD···BSeD···ClI

BrI···BSeD···BSeD···BrI

I2···BSeD···BSeD···I2

CF3I···BSeD···BSeD···CF3I

CCl3I···BSeD···BSeD···CCl3I

CBr3I···BSeD···BSeD···CBr3I

CI4···BSeD···BSeD···CI4

HCCI···BSeD···BSeD···HCCI

FCCI···BSeD···BSeD···FCCI

NCI···BSeD···BSeD···NCI

C6F3I3···BSeD···BSeD···C6F3I3

C6F4I2···BSeD···BSeD···C6F4I2

C6F5I···BSeD···BSeD···C6F5I |

−14.05

−12.35

−9.32

−6.06

−7.13

−7.49

−7.39

−6.62

−6.92

−8.91

−6.34

−6.53

−6.55 |

−8.98

−8.90

−8.69

−8.23

−8.39

−8.45

−8.47

−8.24

−8.27

−8.37

−8.28

−8.30

−8.29 |

−8.35

−8.29

−8.12

−7.81

−7.91

−7.93

−7.93

−7.81

−7.83

−7.94

−7.82

−7.83

−7.83 |

−0.63

−0.61

−0.57

−0.42

−0.48

−0.52

−0.54

−0.43

−0.44

−0.43

−0.46

−0.47

−0.46 |

−9.25

−9.14

−8.90

−8.39

−8.57

−8.64

−8.67

−8.43

−8.44

−8.57

−8.48

−8.47

−8.47 |

−9.16

−9.05

−8.79

−8.32

−8.47

−8.51

−8.51

−8.33

−8.35

−8.55

−8.34

−8.36

−8.37 |

−0.09

−0.09

−0.11

−0.07

−0.10

−0.13

−0.16

−0.10

−0.09

−0.02

−0.14

−0.11

−0.10 |

Table 2.

Crystal and X-ray structure refinement data for the three cocrystals [I12][BSeD], [I13][BSeD] and [I135][BSeD].

Table 2.

Crystal and X-ray structure refinement data for the three cocrystals [I12][BSeD], [I13][BSeD] and [I135][BSeD].

| |

[I12][BSeD] |

[I13][BSeD] |

[I135][BSeD] |

| CCDC deposition number |

2239822 |

2239823 |

2239824 |

| Empirical formula |

C12H4F4I2N2Se |

C18H8F4I2N4Se2

|

C12H4F3I3N2Se |

| Formula weight |

584.93 |

768.00 |

692.83 |

| Temperature/K |

293.00(2) |

290.00(10) |

293.00(2) |

| Crystal system |

monoclinic |

orthorhombic |

monoclinic |

| Space group |

P21/n

|

Pbca |

P21/c

|

|

a/Å |

15.0997(6) |

14.8028(4) |

4.4302(2) |

|

b/Å |

4.2279(2) |

15.5137(4) |

29.9768(14) |

|

c/Å |

23.6753(9) |

37.2860(14) |

12.2962(7) |

α/°

β/°

γ/° |

90

90.124(4)

90 |

90

90

90 |

90

91.505(5)

90 |

| Volume/Å3

|

1511.43(11) |

8562.6(5) |

1632.41(14) |

| Z |

4 |

16 |

4 |

|

ρcalc/g‧cm−3

|

2.571 |

2.383 |

2.819 |

| Color |

colorless |

colorless |

colorless |

| Crystal size/mm3

|

0.29 × 0.28 × 0.17 |

0.2 × 0.17 × 0.15 |

0.22 × 0.18 × 0.15 |

| Reflections collected |

16599 |

57076 |

19226 |

| Independent reflections |

3453 |

9660 |

3668 |

|

Rint

|

0.0371 |

0.0693 |

0.0547 |

| Number of refined parameters |

190 |

541 |

190 |

| Goodness-of-fit on F2

|

1.122 |

1.094 |

1.308 |

| Final R1 index [I ≥ 2σ(I)] |

0.0333 |

0.060 |

0.0770 |

| Final wR2 index [I ≥ 2σ(I)] |

0.0623 |

0.0756 |

0.1240 |

| Final R1 index [all data] |

0.0424 |

0.1217 |

0.0918 |

| Final wR2 index [all data] |

0.0657 |

0.0880 |

0.1286 |

Table 3.

Crystal and X-ray structure refinement data for the two cocrystals [I14][F-BSeD] and [I135][F-BSeD].

Table 3.

Crystal and X-ray structure refinement data for the two cocrystals [I14][F-BSeD] and [I135][F-BSeD].

| |

[I14][F-BSeD] |

[I135][F-BSeD] |

| CCDC deposition number |

2417680 |

2417681 |

| Empirical formula |

C18H6F6I2N4Se2

|

C18H6F5I3N4Se2

|

| Formula weight |

803.99 |

911.89 |

| Temperature/K |

293.00(2) |

100.00(10) |

| Crystal system |

monoclinic |

monoclinic |

| Space group |

P21/n

|

C2/c

|

|

a/Å |

13.0258(6) |

14.3599(6) |

|

b/Å |

6.3844(3) |

9.2659(4) |

|

c/Å |

13.4476(6) |

17.4527(9) |

α/°

β/°

γ/° |

90

104.852(5)

90 |

90

101.082(4)

90 |

| Volume/Å3

|

1080.97(9) |

2278.91(18) |

| Z |

2 |

4 |

|

ρcalc/g‧cm−3

|

2.470 |

2.658 |

| Color |

colorless |

colorless |

| Crystal size/mm3

|

0.33 × 0.25 × 0.18 |

0.13 × 0.12 × 0.10 |

| Reflections collected |

13343 |

2009 |

| Independent reflections |

2678 |

2009 |

|

Rint

|

0.0627 |

0.0334 |

| Number of refined parameters |

145 |

142 |

| Goodness-of-fit on F2

|

1.036 |

1.113 |

| Final R1 index [I ≥ 2σ(I)] |

0.0349 |

0.0674 |

| Final wR2 index [I ≥ 2σ(I)] |

0.0555 |

0.1818 |

| Final R1 index [all data] |

0.0579 |

0.0716 |

| Final wR2 index [all data] |

0.0626 |

0.1857 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).