1. Introduction

Mastication is a fundamental component of the stomatognathic system and is crucial in sustaining overall health and life [

1]. Malocclusion negatively impacts masticatory function [

2,

3], and its relationship with factors such as the number of remaining teeth [

4,

5,

6], bite force, and chewing ability [

4,

7,

8], as well as lateral induction factors influencing mandibular trajectories, have been extensively studied [

9]. However, many of these studies have been limited to group comparisons between individuals with healthy oral function and those experiencing hypofunction, often neglecting intra-individual variability. Consequently, the potential interplay between additional factors, such as oral hygiene [

10], dryness [

11], bite force, and tongue-lip movement remains insufficiently understood [

12].

Diagnostic criteria for oral hypofunction have been developed to assess oral functional decline in older individuals [

13,

14]. This condition encompasses a complex reduction in chewing, swallowing, vocalization, and salivation, which, if untreated, can lead to malnutrition, frailty, and systemic health deterioration. Effective prevention and management necessitate a deeper understanding of the mechanisms underlying masticatory dysfunction [

15,

16,

17]. Although previous studies [

18,

19,

20] have highlighted the importance of early interventions during childhood to support normal growth and development, specific preventive methods remain undefined.

To address these gaps, this study aimed to develop a noninvasive oral hypofunction model using a mouthpiece. Designed for use in healthy individuals, this simple and accessible method enables the analysis of oral function under controlled conditions, ultimately contributing to a more comprehensive understanding of masticatory mechanisms.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

This cross-sectional study adhered to the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Review Committee of the Institute of Science, Tokyo, Japan (approval number: S2024-018). Participants received detailed verbal explanations regarding the study's objectives, methods, safety measures, and potential risks and provided written informed consent prior to participation.

2.2. Participants

The inclusion criteria for participants were as follows:

Healthy adults aged 26–32 years;

Normal occlusion with no abnormalities in the stomatognathic system;

A minimum of 24 functional teeth;

Absence of prosthetic teeth, crossbite, scissors bite, or open bite;

No history of masticatory disorders or muscular diseases;

No cognitive impairments;

Ability to chew gummy jelly and no known gelatin allergies.

Exclusion criteria included:

Congenital abnormalities (e.g., cleft lip and palate);

Severe mandibular or nasal bone curvature;

Inability to evaluate mandibular shape due to facial hair, including beards and sideburns;

A BMI outside the range of 18.5–25, as defined by Japan Obesity Society standards;

Withdrawal of consent at any stage of the study.

2.3. Intervention

The experiments were conducted under four conditions (

Figure 1):

I: No mouthpiece;

II: A mouthpiece with large occlusal contact areas and canine guidance;

III: A mouthpiece with large occlusal contact areas but without canine guidance;

IV: A mouthpiece with small occlusal contact areas without canine guidance.

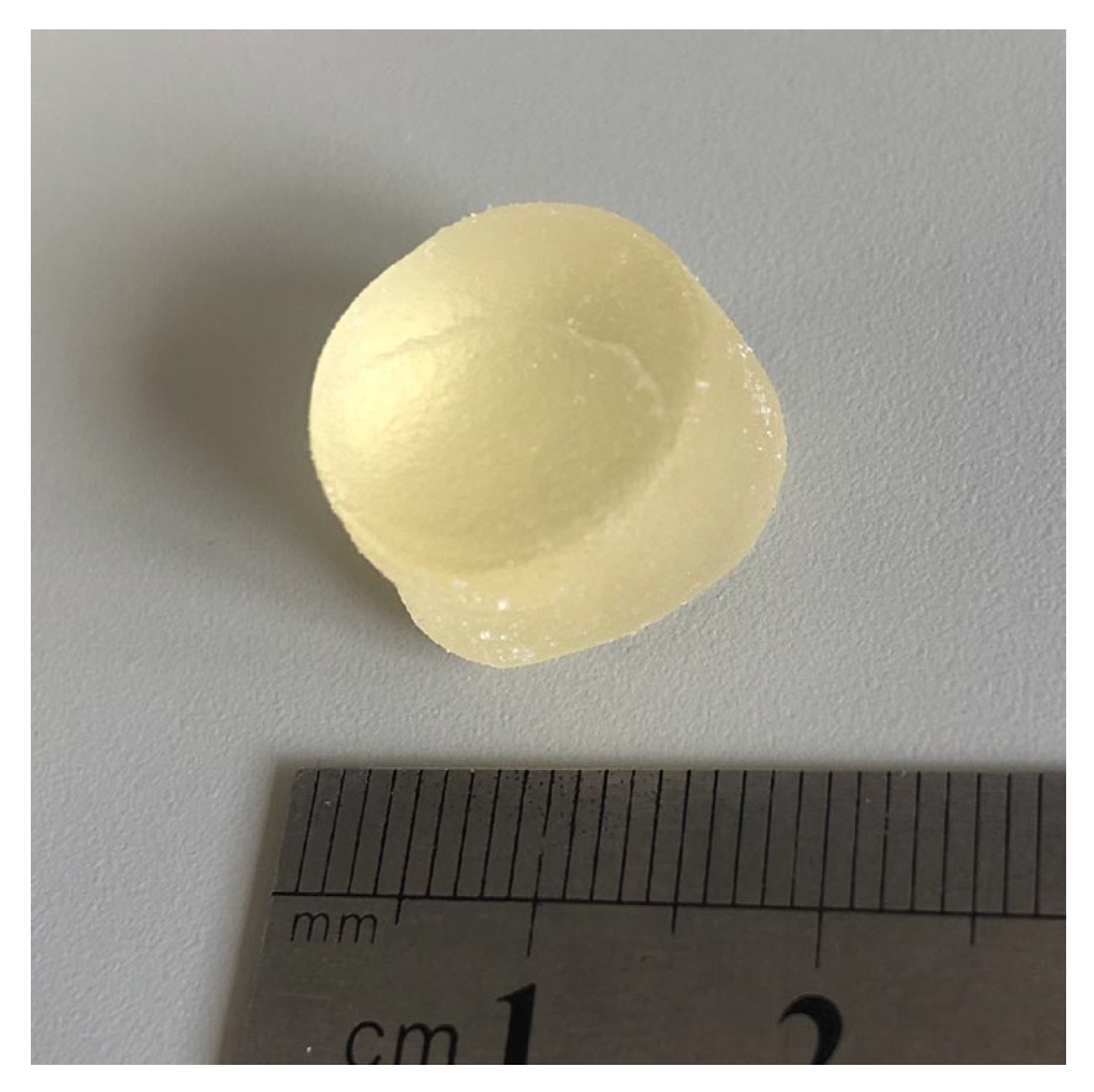

Glucose-containing gummy jelly (

Figure 2; GLUCOLUMN; GC Corp., Tokyo, Japan; [

21] diameter: 14 mm; height: 8 mm; weight: approximately 2 g) was masticated on the habitual chewing side for 20 seconds under each condition. After mastication, subjects rinsed their mouths with 10 ml of water and expectorated the jelly into a filtration device. Each condition was tested in three sets, with a 15-minute break between conditions and a 3-minute break between sets to minimize fatigue.

Mouthpieces were fabricated using a thermoplastic resin (NEWIMPRELON S PD; JM Ortho, Tokyo, Japan; thickness = 1.5 mm) and adjusted with a polymerization resin (UNIFAST III; GC Corp., Tokyo, Japan) to ensure consistent bite height across conditions. Adjustments were made to prevent discomfort or interference with lip and tongue movements. All interventions were conducted between 13:00 and 17:00 on the same day, and participants were not required to fast prior to the study.

2.4. Outcomes

The outcomes were evaluated under each condition. Maximum bite force, occlusal contact areas, masticatory ability, and salivation were measured. To minimize fatigue, a 15-minute break between each condition and a 3-minute break between each experiment were given.

2.4.1. Maximum Bite Force and Occlusal Contact Areas

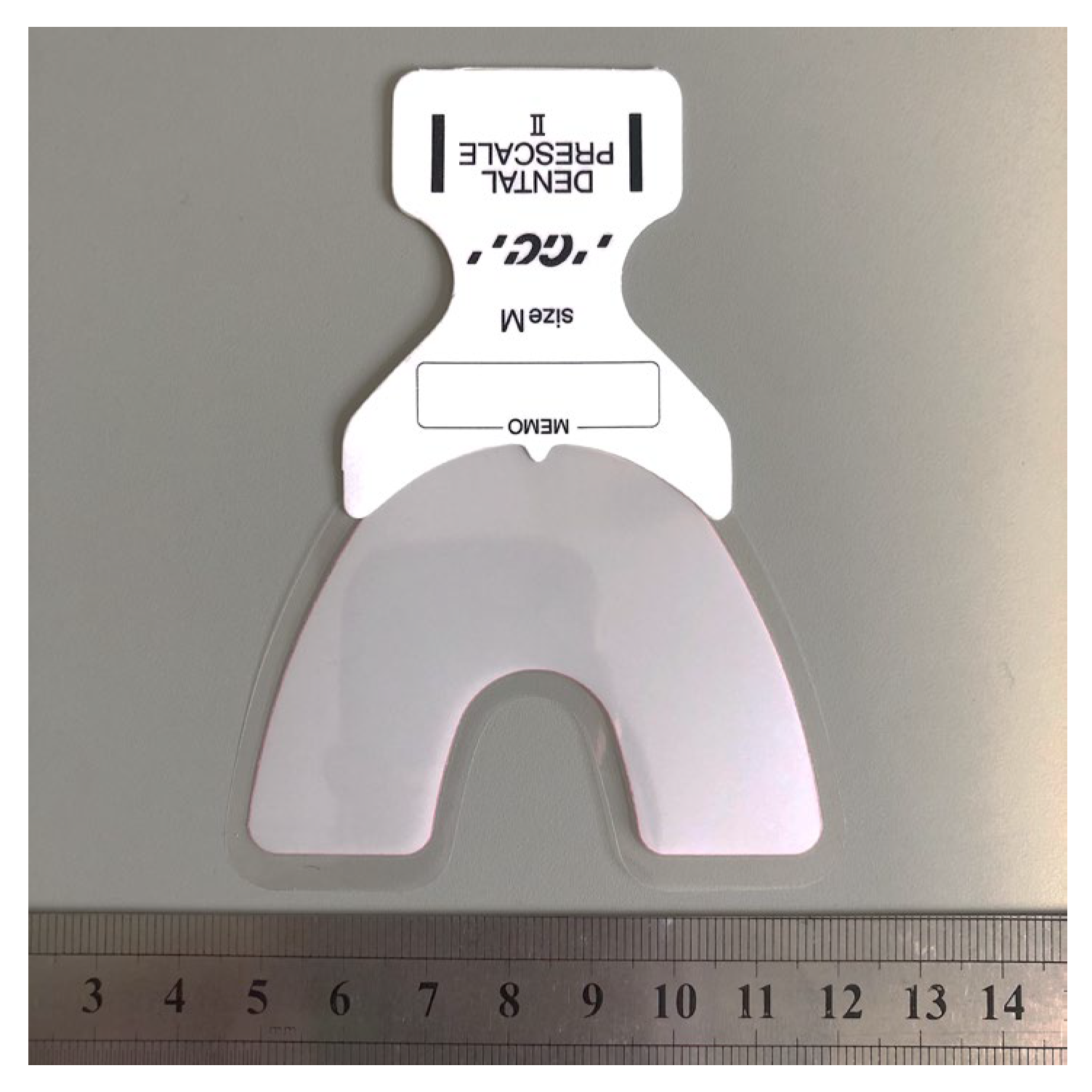

Maximum occlusal force and contact areas were measured using a pressure-sensitive film (

Figure 3; Dental Prescale II; GC Corp., Tokyo, Japan). The film was inserted into the oral cavity to ensure complete coverage of the dentition, and participants were instructed to bite the film for three seconds. The occlusal state was analyzed using occlusal force analysis software (Bite Force Analyzer; GC Corp., Tokyo, Japan) [

22,

23].

2.4.2. Chewing Ability

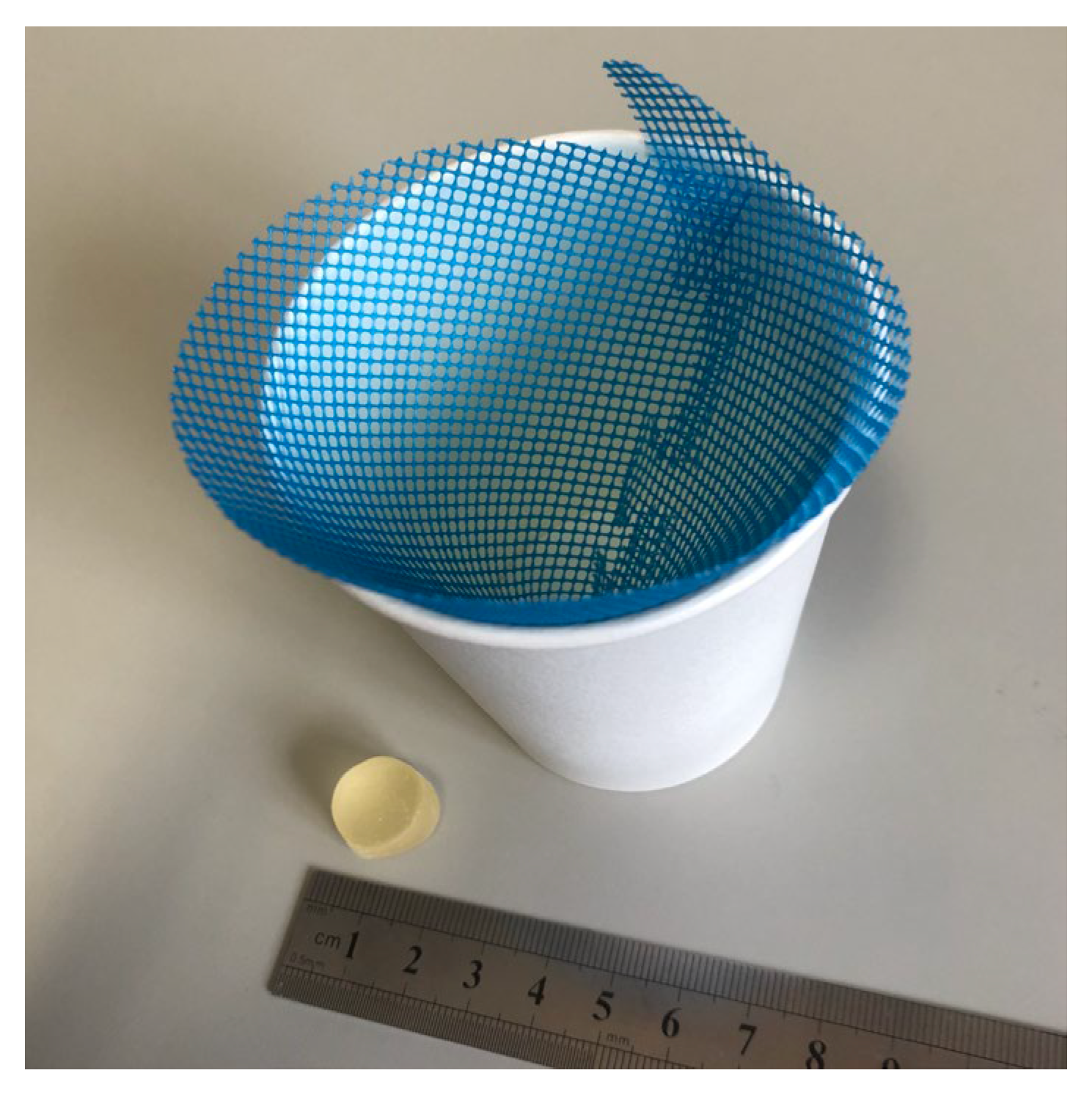

Glucose-containing gummy jelly was used to evaluate chewing ability. Participants masticated the gummy jelly on their habitual chewing side for 20 seconds without swallowing. After mastication, 10 ml of water was added to the mouth and gently rinsed, and the combined mixture of masticated gummy jelly and water was expectorated onto a filter (

Figure 4). The filtrate concentration was then analyzed using a glucose sensor (GLUCOSENSOR; GC Corp., Tokyo, Japan) [

21]. In addition, the gummy jelly was maintained at room temperature to prevent changes in hardness due to temperature fluctuations.

2.4.3. Salivation

The amount of saliva was measured by weighing the expectorated contents after chewing, and the gummy jelly’s weight was subtracted to calculate the net saliva production. As this study was a comparative experiment conducted with the same subjects, it was assumed that baseline salivary flow at rest did not vary significantly. However, because the method used to measure chewing ability in this study depended on the glucose concentration, the saliva volume was also measured to ensure accurate interpretation [

24].

2.5. Statistics

Statistical analyses were performed using t-tests with the Bonferroni correction. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

3. Results

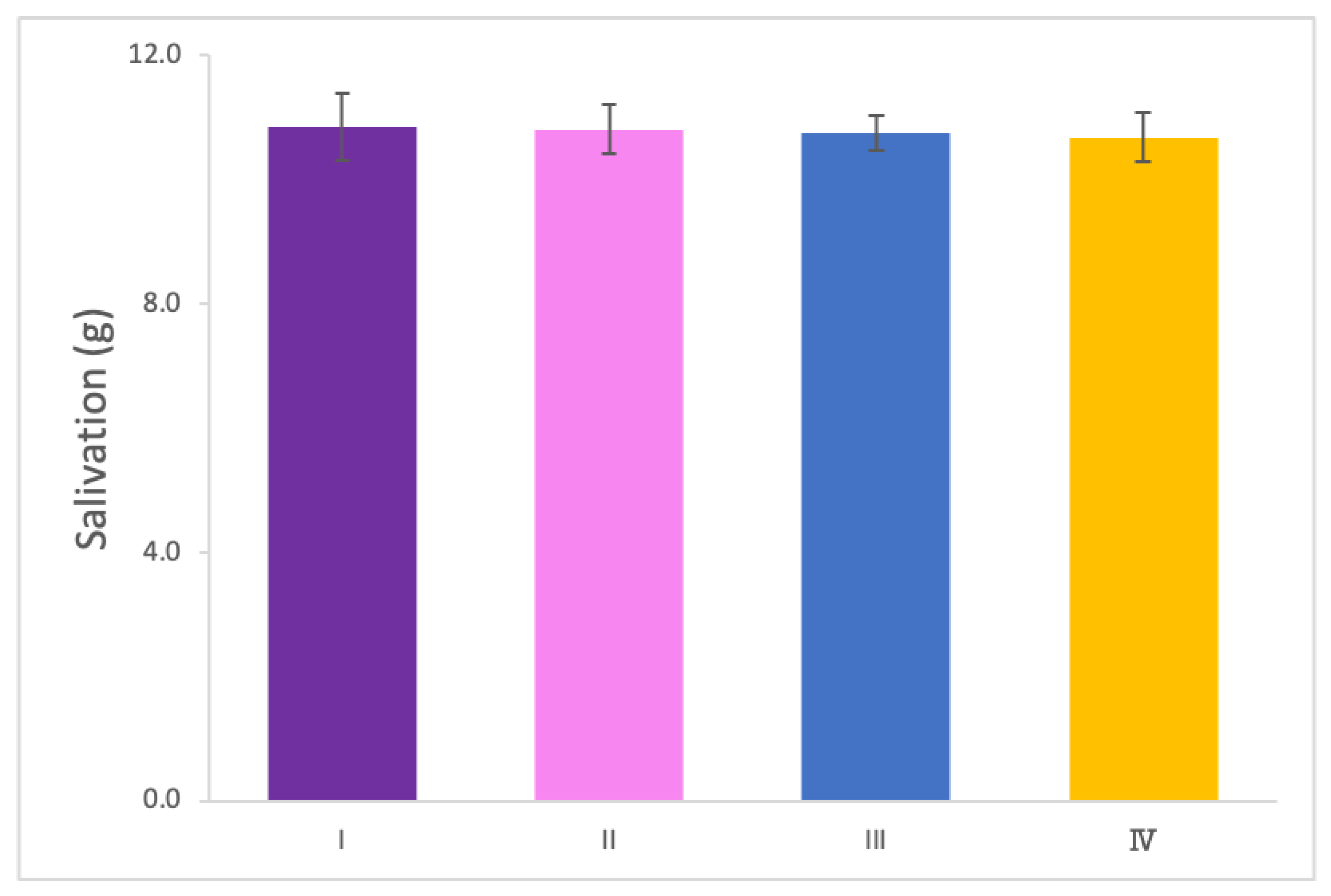

3.1. Salivation Measurement

The weight of the glucose solution mixed with saliva was measured under the four experimental conditions. No significant differences were observed in salivation levels across conditions, indicating that neither the occlusal state nor the use of a mouthpiece influenced saliva secretion (

Figure 5).

3.2. Relationship between Occlusal Contact Areas and Maximum Bite Force

3.2.1. Measurement of Occlusal Contact Areas

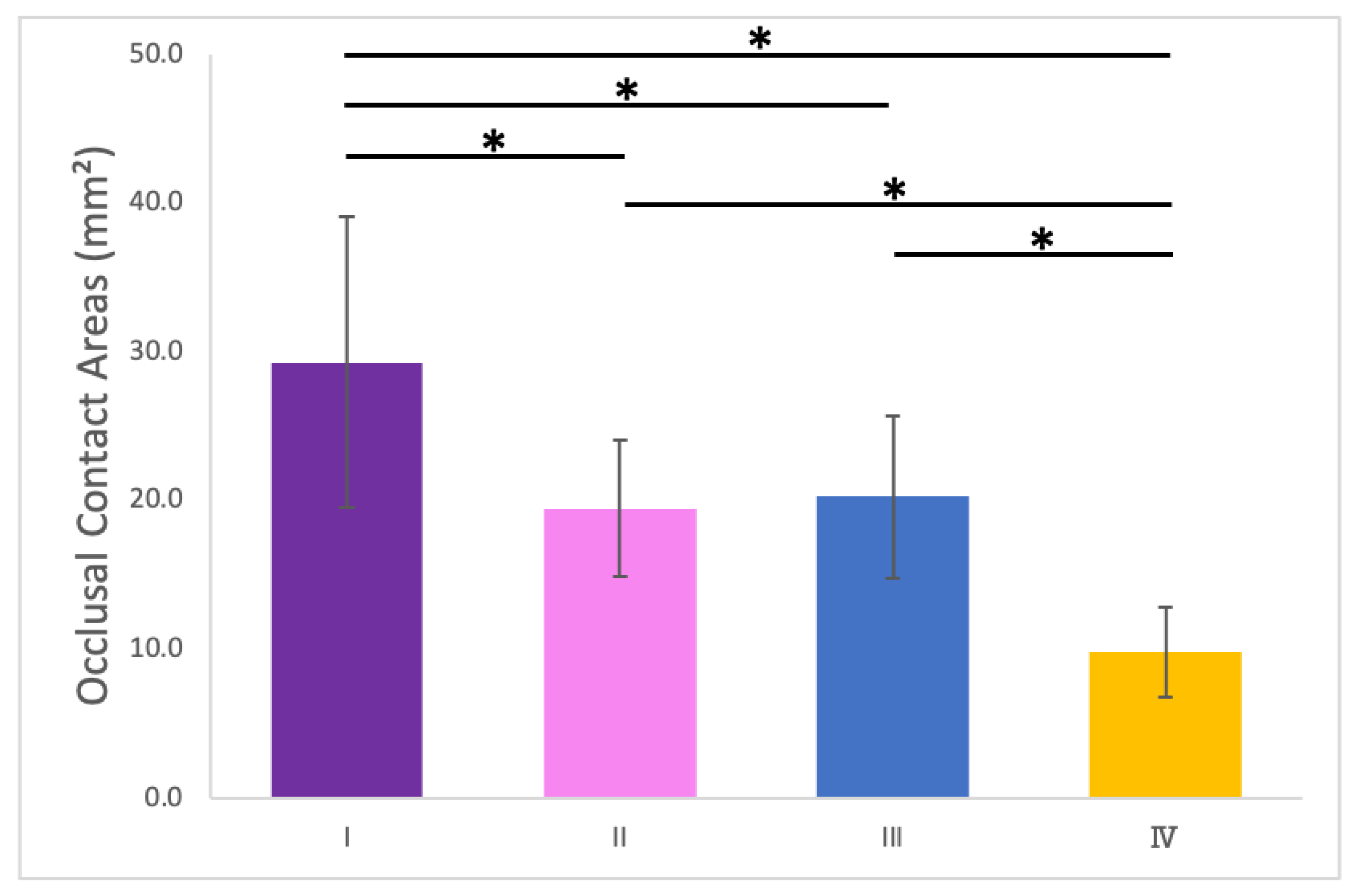

The occlusal contact areas were significantly larger under Condition I compared to the other conditions. No significant differences were observed between Conditions II and III, while Condition IV exhibited the smallest occlusal contact area (

Figure 6).

3.2.2. Relationship Between Occlusal Contact Areas and Maximum Bite Force

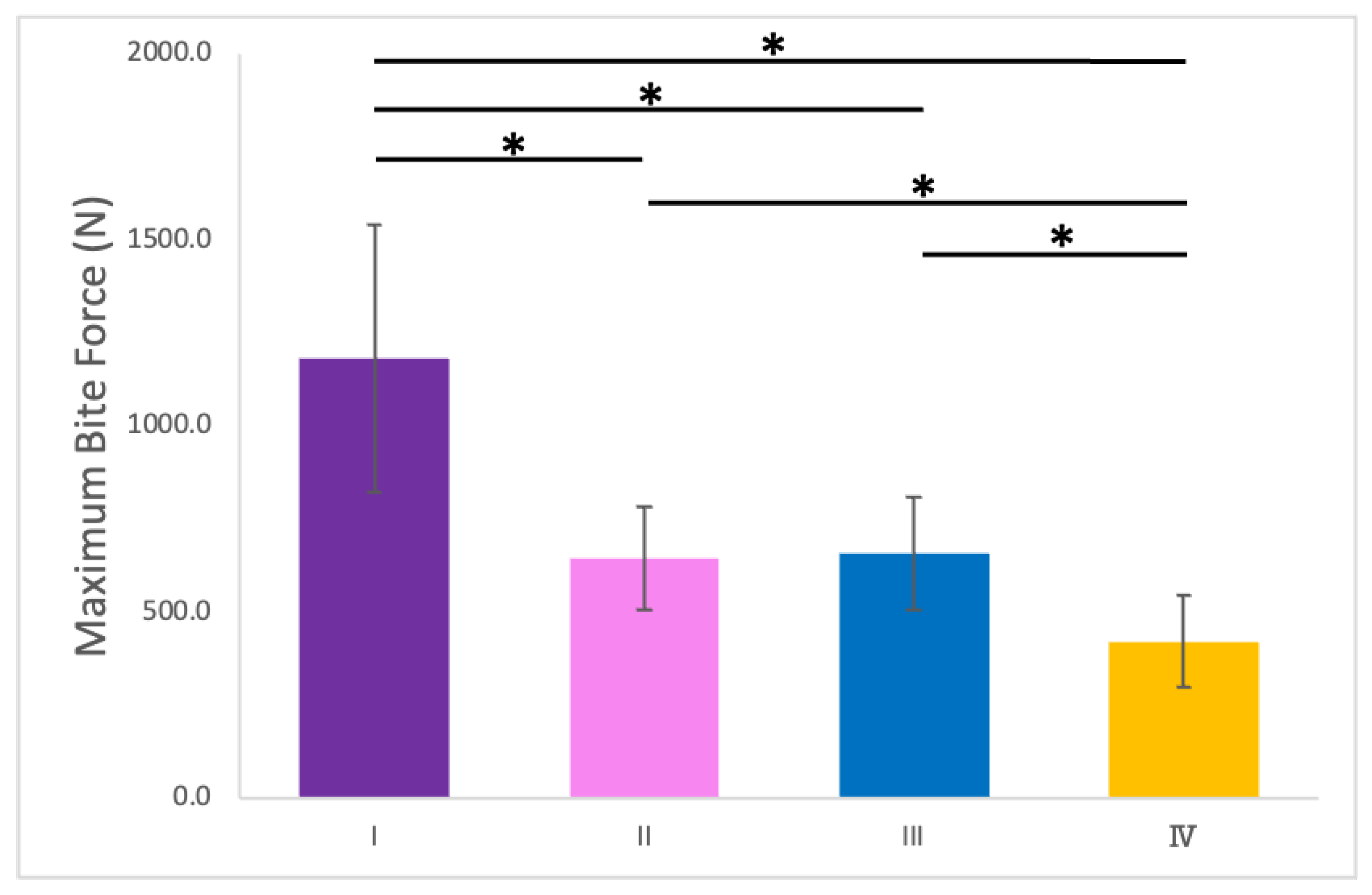

The maximum bite forces measured under the four conditions are shown in

Figure 7. Conditions II and III showed no significant differences in bite force. However, the bite force was significantly reduced in Condition IV compared with Conditions II and III.

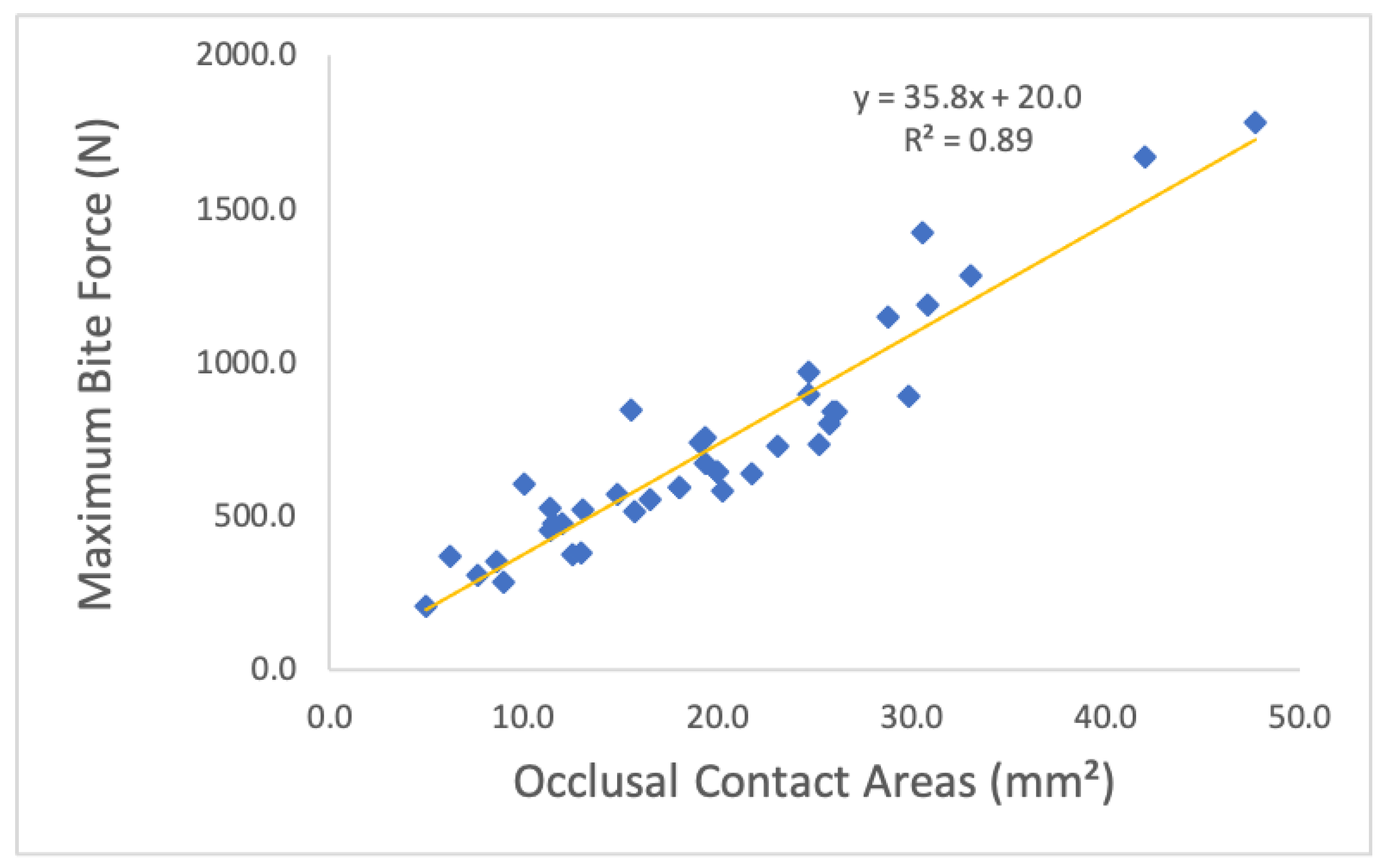

The maximum bite force mirrored the pattern observed for occlusal contact areas, with a significant positive correlation between the two variables (p < 0.001;

Figure 8).

3.3. Relationship Between Occlusal Contact Areas and Glucose Concentration

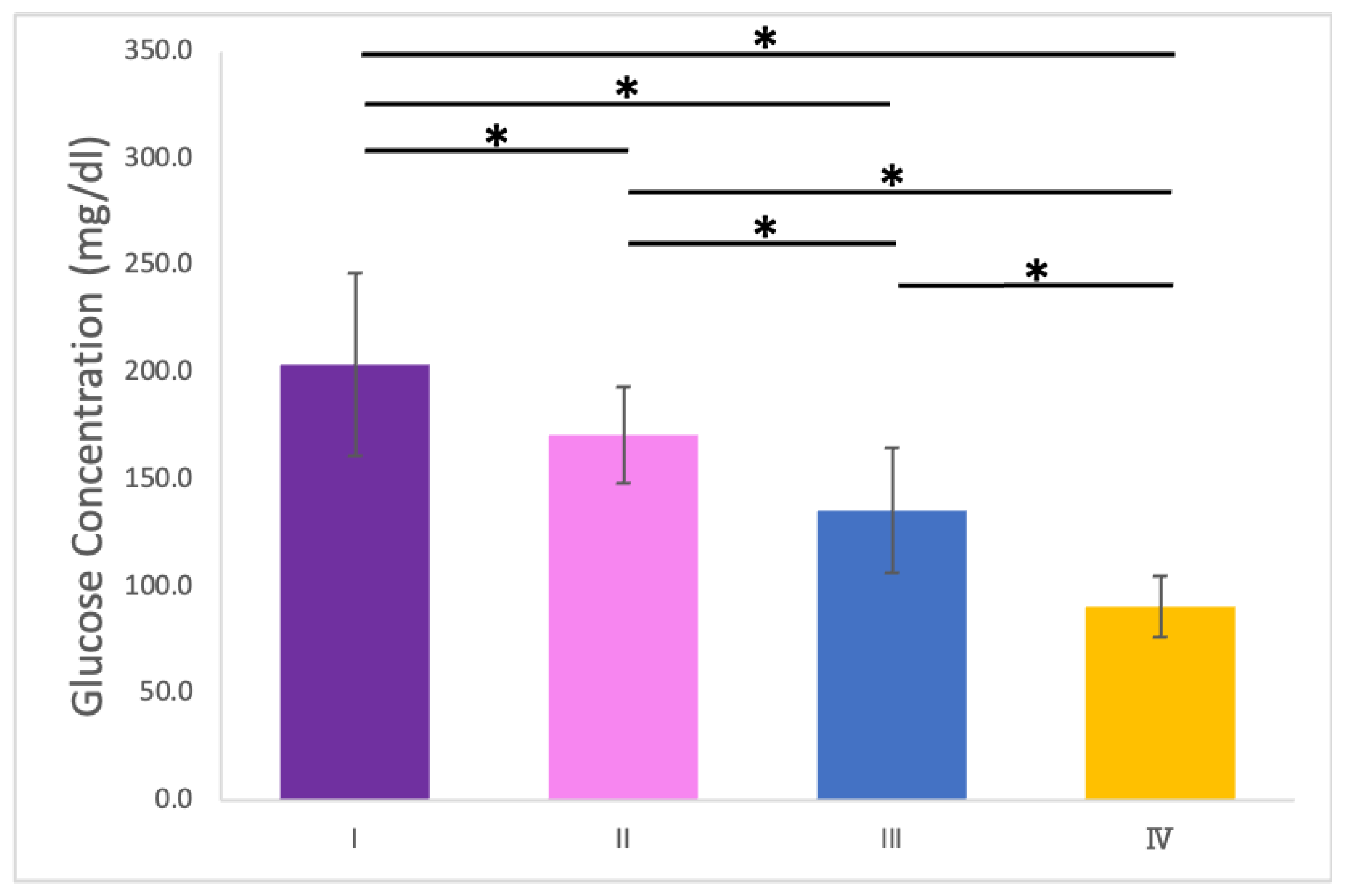

3.3.1. Measurement of Glucose Concentration

The glucose concentration of the filtered solution decreased significantly from

3.3.2. Relationship Between Occlusal Contact Areas and Glucose Concentration

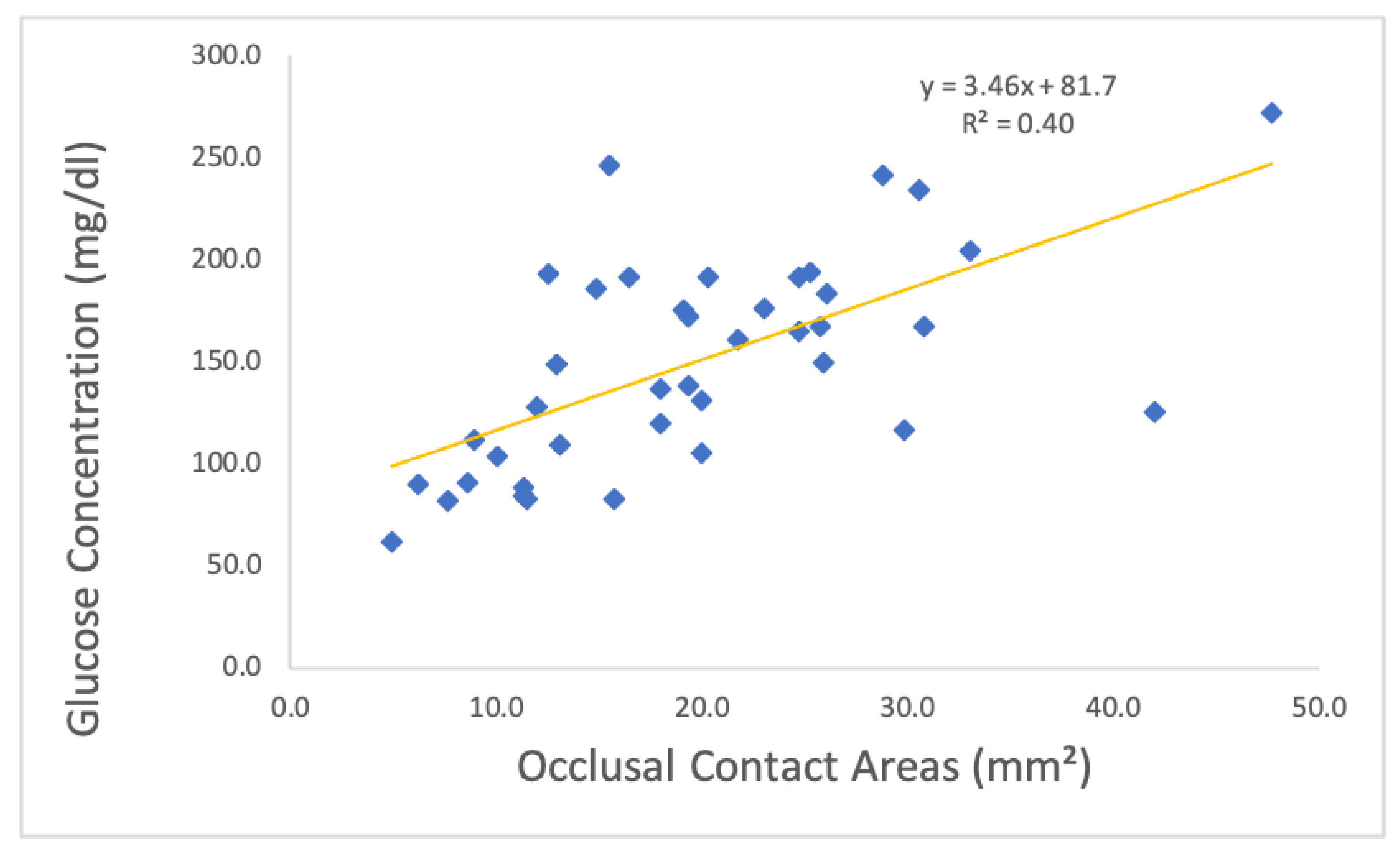

In contrast to the relationship between bite force and occlusal contact areas, a significant correlation was observed between occlusal contact areas and chewing ability, as indicated by glucose concentration (p < 0.001;

Figure 10).

4. Discussion

This study aimed to establish an oral hypofunction model using a mouthpiece and evaluate its effects on salivation, occlusal contact areas, maximum bite force, and mastication ability under controlled conditions. The findings are consistent with previous research and provide novel insights into the relationship between occlusal characteristics and masticatory performance.

4.1. Salivation

The absence of significant differences in salivation across conditions suggests that neither the occlusal state nor the presence of a mouthpiece significantly affects saliva secretion. This finding validates the experimental design, ensuring that variations in salivation did not confound the other measured outcomes

[24].

4.2. Occlusal Contact Areas and Bite Force

A significant positive correlation was identified between occlusal contact areas and maximum bite force. In Condition II, the occlusal contact areas were significantly smaller than those in Condition I. Under normal occlusion, the upper and lower teeth contact each other with the occlusal cusps fitting into the opposing occlusal cavities

[25]. However, in Condition II, the occlusal cusps of the maxilla were not reproduced in the mouthpiece, resulting in a “point contact” occlusion. In addition, comparisons between Condition I and the other conditions require careful interpretation. Condition I had a lower occlusal vertical dimension compared to Conditions II, III, and IV. Comparing Conditions II and III, no significant differences were observed in the occlusal contact area and occlusal force, as the only variable distinguishing these conditions was the lateral induction factor. In contrast, comparing Conditions II and III with Condition IV revealed a significant decrease in occlusal force, attributed to a reduction in occlusal contact area by approximately half. This finding was consistent with those of previous studies

[4,7]; however, those studies may have been influenced by factors such as muscle strength, as they did not compare results within the same subjects. In this study, the significant decrease in maximum bite force observed with the reduction in occlusal contact areas can be attributed to the controlled experimental conditions, as all measurements were performed on the same subjects under identical protocols.

4.3. Chewing Ability

A significant positive correlation was observed between occlusal contact areas and chewing ability. A comparison of Conditions II and III revealed that the presence of lateral induction factors, such as canine guidance, had a substantial impact on chewing ability. A previous study [

26] has highlighted that lateral induction factors influence mandibular movement pathways during chewing, establishing a relationship between mandibular trajectories and chewing ability [

27]. In this study, the loss of lateral induction factors altered mandibular trajectories, leading to a significant deterioration in chewing ability in Conditions III and IV. In addition, Lateral induction factors take various forms, such as group function and canine tooth induction. In this study, canine tooth induction was emphasized for its high reproducibility and minimal interference with the molars on the habitual and opposite chewing sides. However, as the presence or absence of canine tooth induction was not a criterion for subject selection, some subjects did not exhibit canine tooth induction. For these individuals, the glucose concentration in Condition II was higher than that of Condition I. Comparing Conditions III and IV under the same lateral induction factors revealed a significant decrease in chewing ability as the occlusal contact area decreased. While no previous studies have specifically examined the effects of conditions with or without lateral induction factors, previous studies [

3,

4] have shown that chewing ability decreases as occlusal contact areas decrease. This aligns with the findings of this study and highlights the complex interplay between occlusal factors and mandibular biomechanics.

4.4. Clinical Implications

These findings are consistent with those of previous studies, validating the mouthpiece model as a reliable tool for simulating oral hypofunction. The mechanism of oral hypofunction has been explored in studies investigating the relationships between the number of remaining teeth, bite force, mastication ability, and lateral induction factors affecting chewing pathways. However, many of these studies have lacked intrasubject verification, leaving key influencing factors unaddressed. This model offers a noninvasive and accessible method for simulating oral hypofunction in healthy individuals, enabling controlled intrasubject comparisons. Such an approach facilitates the understanding of how occlusal variables influence mastication mechanics, providing valuable insights into the complex interactions within the stomatognathic system. The simplicity and scalability of the model make it a valuable tool for future research. Furthermore, its ability to reproduce various malocclusions observed in clinical practice makes it useful for studying a wide range of chewing malfunctions.

5. Conclusions

This study successfully established an oral hypofunction model using a mouthpiece, with findings consistent with previous research. The model allows intrasubject comparisons under controlled conditions, enabling precise analysis of factors influencing masticatory performance. Its adaptability to healthy subjects and ease of use make it a promising method for advancing research into the mechanisms underlying oral hypofunction and for designing effective clinical interventions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.K., I.Y., K.S., H.T., Y.T., N.M. and M.W.; material preparation, Y.T-T.; data collection, M.K., K.S. and H.T.; data analysis, I.Y., H.T., K.S., K.S. and M.U.; writing—original draft preparation, M.K. and I.Y.; writing—review, H.T., K.S., K.S., M.U. and T.O. All authors read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by JSPS KAKENHI, grant number JP23K19092.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Review Committee of the Institute of Science, Tokyo (approval number: S2024-018).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are not publicly available because of the data confidentiality requirements of the ethics committee, but are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request and approval from the ethics committee.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number JP23K19092 for financial support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviation

The following abbreviation was used in this manuscript:

References

- Peck, C.C. Biomechanics of Occlusion - Implications for Oral Rehabilitation. J Oral Rehabil 2016, 43, 205–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rios-Vera, V.; Sánchez-Ayala, A.; Senna, P.M.; Watanabe-Kanno, G.; Del Bel Cury, A.A.; Matheus Rodrigues Garcia, R.C. Relationship among Malocclusion, Number of Occlusal Pairs and Mastication. Braz Oral Res 2010, 24, 419–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magalhães, I.B.; Pereira, L.J.; Marques, L.S.; Gameiro, G.H. The Influence of Malocclusion on Masticatory Performance: A Systematic Review. Angle Orthod 2010, 80, 981–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lujan-Climent, M.; Martinez-Gomis, J.; Palau, S.; Ayuso-Montero, R.; Salsench, J.; Peraire, M. Influence of Static and Dynamic Occlusal Characteristics and Muscle Force on Masticatory Performance in Dentate Adults. Eur J Oral Sci 2008, 116, 229–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hara, K.; Namiki, C.; Yamaguchi, K.; Kobayashi, K.; Saito, T.; Nakagawa, K.; Ishii, M.; Okumura, T.; Tohara, H. Association between Myotonometric Measurement of Masseter Muscle Stiffness and Maximum Bite Force in Healthy Elders. J Oral Rehabil 2020, 47, 750–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borg-Bartolo, R.; Roccuzzo, A.; Molinero-Mourelle, P.; Schimmel, M.; Gambetta-Tessini, K.; Chaurasia, A.; Koca-Ünsal, R.B.; Tennert, C.; Giacaman, R.; Campus, G. Global Prevalence of Edentulism and Dental Caries in Middle-Aged and Elderly Persons: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Dent 2022, 127, 104335. [CrossRef]

- Iwasaki, M.; Yoshihara, A.; Sato, N.; Sato, M.; Minagawa, K.; Shimada, M.; Nishimuta, M.; Ansai, T.; Yo-shitake, Y.; Ono, T.; et al. A 5-Year Longitudinal Study of Association of Maximum Bite Force with Development of Frailty in Community-Dwelling Older Adults. J Oral Rehabil 2018, 45, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Julien, K.C.; Buschang, P.H.; Throckmorton, G.S.; Dechow, P.C. Normal Masticatory Performance in Young Adults and Children. Archives of Oral Biology 1996, 41, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshida, E.; Fueki, K.; Igarashi, Y. Association between Food Mixing Ability and Mandibular Movements during Chewing of a Wax Cube. J Oral Rehabil 2007, 34, 791–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dawes, C.; Tsang, R.W.L.; Suelzle, T. The Effects of Gum Chewing, Four Oral Hygiene Procedures, and Two Saliva Collection Techniques, on the Output of Bacteria into Human Whole Saliva. Arch Oral Biol 2001, 46, 625–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, E.P.; Hwang, S.J.; Clovis, J.B.; Lee, T.Y.; Paik, D. Il; Hwang, Y.S. Enhancing the Quality of Life in Elderly Women through a Programme to Improve the Condition of Salivary Hypofunction. Gerodontology 2012, 29, e972–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ducret, M.; Mörch, C.M.; Karteva, T.; Fisher, J.; Schwendicke, F. Artificial Intelligence for Sustainable Oral Healthcare. J Dent 2022, 127, 104344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minakuchi, S. Philosophy of Oral Hypofunction. Gerodontology 2022, 39, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minakuchi, S.; Tsuga, K.; Ikebe, K.; Ueda, T.; Tamura, F.; Nagao, K.; Furuya, J.; Matsuo, K.; Yamamoto, K.; Kanazawa, M.; et al. Oral Hypofunction in the Older Population: Position Paper of the Japanese Society of Gerodontology in 2016. Gerodontology 2018, 35, 317–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.J.; Lee, J.Y.; Lee, E.S.; Jung, H.J.; Ahn, H.J.; Kim, B. Il Improvements in Oral Functions of Elderly after Simple Oral Exercise. Clin Interv Aging 2019, 14, 915–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, M.; Satoh, Y. Effects of Gum Chewing Training on Oral Function in Normal Adults: Part 1 Investigation of Perioral Muscle Pressure. J Dent Sci 2019, 14, 38–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shirai, M.; Kawai, N.; Hichijo, N.; Watanabe, M.; Mori, H.; Mitsui, S.N.; Yasue, A.; Tanaka, E. Effects of Gum Chewing Exercise on Maximum Bite Force According to Facial Morphology. Clin Exp Dent Res 2018, 4, 48–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patil, R.; Khubchandani, M.; Kanani, H.; Yeluri, R.; Dangore-Khasbage, S. Unravelling the Complexities of Bite Force Determinants in Paediatric Patients: A Literature Review. Cureus 2024, 16, e60630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Morais Santos Campos, M.P.; de Melo Valença, P.A.; da Silva, G.M.; Lima, M.D.C.; Jamelli, S.R.; de Góes, P.S.A. Influence of Head and Linear Growth on the Development of Malocclusion at Six Years of Age: A Cohort Study. Braz Oral Res 2018, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Duan, P.; He, H.; Song, J.; Hu, M.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Guo, J.; Jin, F.; Cao, Y.; et al. Expert Consensus on Pediatric Orthodontic Therapies of Malocclusions in Children. Int J Oral Sci 2024, 16, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uesugi, H.; Shiga, H. Relationship between Masticatory Performance Using a Gummy Jelly and Masticatory Movement. J Prosthodont Res 2017, 61, 419–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.F.; Wang, C.M.; Shieh, W.Y.; Liao, Y.F.; Hong, H.H.; Chang, C.T. The Correlation between Two Occlusal Analyzers for the Measurement of Bite Force. BMC Oral Health 2022, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shiga, H.; Komino, M.; Uesugi, H.; Sano, M.; Yokoyama, M.; Nakajima, K.; Ishikawa, A. Comparison of Two Dental Prescale Systems Used for the Measurement of Occlusal Force. Odontology 2020, 108, 676–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanehira, T.; Yamaguchi, T.; Asano, K.; Morita, M.; Maeshima, E.; Matsuda, A.; Fujii, Y.; Sakamoto, W. A Screening Test for Capsaicin-Stimulated Salivary Flow Using Filter Paper: A Study for Diagnosis of Hyposalivation with a Complaint of Dry Mouth. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2011, 112, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.Q.; Mehta, N. A Possible Biomechanical Role of Occlusal Cusp-Fossa Contact Relationships. J Oral Rehabil 2013, 40, 69–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogawa, T.; Ogawa, M.; Koyano, K. Different Responses of Masticatory Movements after Alteration of Occlusal Guidance Related to Individual Movement Pattern. J Oral Rehabil 2001, 28, 830–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imaoka, M.; Okuno, K.; Kobuchi, R.; Inoue, T.; Takahashi, K. Evaluation of Masticatory Performance by Motion Capture Analysis of Jaw Movement. J Oral Rehabil 2023, 50, 1020–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).