Submitted:

17 January 2025

Posted:

21 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Sexual health is a vital aspect of overall well-being, yet individuals with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) face significant stigma and discrimination, affecting self-esteem, relationships, and sexual expression. This review examined recent literature (2020–January 2024) on intimacy and sexuality among adolescents and young adults with ASD, incorporating 32 studies. Findings highlight poorer sexual health among autistic individuals compared to the general population, with difficulties in forming romantic relationships and navigating sexual interactions due to hypersensitivity. Autism is also linked to non-conforming gender identities and asexuality, exposing individuals to dual stigma within the LGBTQ+ community. Autism-related traits hinder sexual health knowledge, increasing risks of victimization, abuse, and sexually transmitted infections. Comprehensive sexual education and inclusive support are crucial to address these challenges and promote sexual well-being for autistic individuals.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

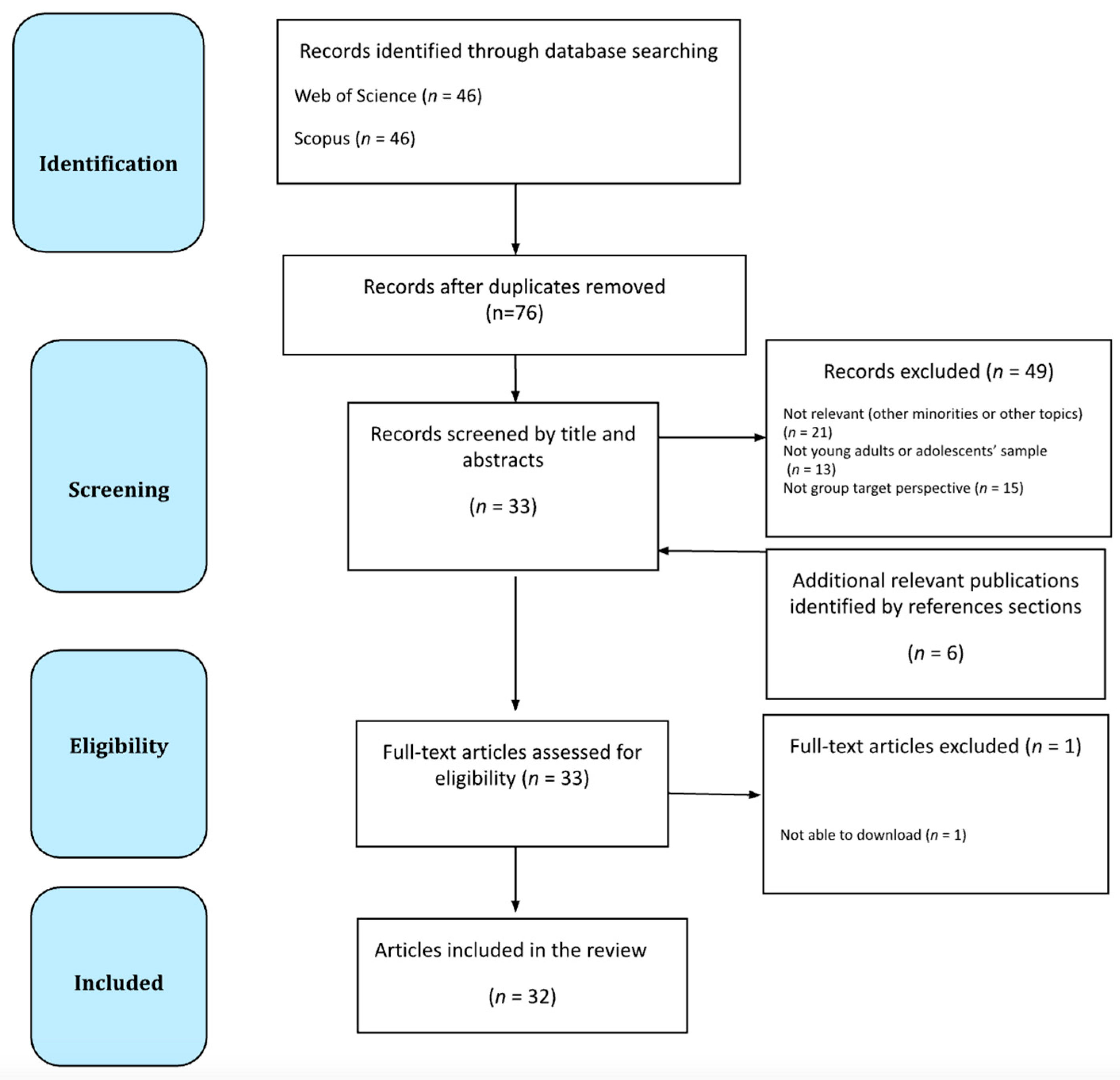

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Selection and Exclusion Criteria

2.2. Search Strategy and Databases Used

2.3. Relevance Assessment, Qualitative Analysis, and Review Type

2.4. Synthesis Process and Themes

3. Results

3.1. Intimacy, Sexuality and Relationships Among Autistic People

3.1.1. Experiences of Intimacy: Similarities and Differences Between Autistic and Non-Autistic Participants.

3.1.2. Sensory Processing and Sexuality

3.1.3. Insights from Long-Term Relationships Involving Autistic Individuals

3.2. Gender Identity and Sexual Orientation

3.2.1. Gender Identity

3.2.2. Sexual Orientation

3.2.3. Asexuality

3.3. Challenges

3.3.1. Hypothetical Explanations

3.3.2. Challenges and Risks in Sexual Behaviour for Autistic Individuals

3.3.3. Heightened Risk and Harsh Realities: Addressing Sexual Abuse and Victimization in Autistic Individuals

3.3.4. Rethinking Sexual Health Risks in the Autistic Population

3.3.5. Sexual Health and Autism: Navigating Challenges and Promoting Inclusive Education and Support

3.3.6. Barriers to Effective Sex Education

3.3.7. Facilitators for Improved Sex Education

-

Theme 1: education and informationIt is advised to provide autistic individuals and their families with education and information regarding sexuality, relationships, and gender diversity. This initiative aims to ensure that autistic people have access to the knowledge necessary to understand and navigate their sexual and relational health and gender identity confidently.

-

Theme 2: Healthcare expertise and accessibilityThe recommendations call for improvements in healthcare professionals' expertise in, and the accessibility of, services related to sexuality, relationships, and gender diversity. This includes a specific focus on preventing sexual victimisation and offering support to those who have experienced it, acknowledging the heightened vulnerability within the autistic population.

-

Theme 3: ResearchThere is a strong emphasis on the meaningful inclusion of the autism community in future research projects that explore well-being in the context of sexuality, relationships, and gender diversity. This ensures that the research is relevant, inclusive, and respectful of the experiences and needs of autistic individuals.

3.3.8. Innovative Strategies for Sexual Education and Relationship Skills in Autistic Individuals

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations and Clinician Challenges

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ASD | Autism Spectrum Disorder |

References

- World Health Organization. Defining sexual health: Report of a technical consultation on sexual health, 28–31 January 2002, 28–31 January 2024.

- Dewinter, J.; Vermeiren, R.; Vanwesenbeeck, I.; Van Nieuwenhuizen, C. (2013). Autism and normative sexual development: A narrative review. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 2013;22:3467–3483. [CrossRef]

- Dewinter, J.; van der Miesen, A.I.R.; Holmes, L.G. INSAR Special Interest Group report: Stakeholder perspectives on priorities for future research on autism, sexuality, and intimate relationships. Autism Research. 2020;13(8):1248–1257. [CrossRef]

- Bertilsdotter Rosqvist, H. Becoming an ‘autistic couple’: Narratives of sexuality and couplehood within the Swedish autistic self-advocacy movement. Sexuality and Disability. [CrossRef]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed. American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013.

- Bury, S.M.; Jellett, R.; Spoor, J.R.; Hedley, D. “It defines who I am” or “It is something I have”: What language do [autistic] Australian adults [on the autism spectrum] prefer? Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 2020;53(2):677-687.

- Kenny, L.; Hattersley, C.; Molins, B.; Buckley, C.; Povey, C.; Pellicano, E. Which terms should be used to describe autism? Perspectives from the UK autism community. Autism, 2016;20:442–462.

- Pecora, L.A.; Hancock, G.I.; Mesibov, G.B.; Stokes, M.A. Characterizing the sexuality and sexual experiences of autistic females. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 2019;49(12):4834-46.

- Kansky, J. What’s Love Got to Do with It? Romantic Relationships and Well-Being. In: Diener E, Oishi S, Tay L, eds. Handbook of Well-Being, Salt Lake City, DEF Publishers; 2018:1-24.

- Braithwaite, S.R.; Holt-Lunstad, J. Romantic relationships and mental health. Current Opinion in Psychology. 2017; 13:120–125.

- Braithwaite, S.R.; Delevi, R.; Fincham, F.D. Romantic relationships and the physical and mental health of college students. Personal Relationships, 2010;17:1–12.

- Hancock, G.; Stokes, M.A.; Mesibov, G. Differences in romantic relationship experiences for individuals with an autism spectrum disorder. Sexuality and Disability, 2019;38(2):231–245. [Google Scholar]

- Strunz, S.; Schermuck, C.; Ballerstein, S.; Ahlers, C.J.; Dziobek, I.; Roepke, S. Romantic relationships and relationship satisfaction among adults with Asperger syndrome and high-functioning autism. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 2017;73(1):113–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engström, I.; Ekström, L.; Emilsson, B. Psychosocial functioning in a group of Swedish adults with Asperger syndrome or high-functioning autism. Autism, 2003;7:99–110. [Google Scholar]

- Renty, J.; Roeyers, H. Quality of life in high-functioning adults with autism spectrum disorder: The predictive value of disability and support characteristics. Autism, 10.1177/1362361317714587. [Google Scholar]

- George, R.; Stokes, M.A. Gender identity and sexual orientation in autism spectrum disorder. Autism, 10.1177/1362361317714587. 2018; 22(8):1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Miesen, A.I.R.; de Vries, A.L.C.; Steensma, T.D.; Hartman, C.A. Autistic symptoms in children and adolescents with gender dysphoria. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 2018;48:1537–1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewinter, J.; De Graaf, H.; Beeger, S. Sexual orientation, gender identity, and romantic relationships in adolescents and adults with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 2017; 47(9):2927–2934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristensen, Z.; Broome, M. Autistic traits in an internet sample of gender variant UK adults. International Journal of Transgenderism, 2016; 16(4):234–245. [Google Scholar]

- Vermaat, L.E.W.; van der Miese, A.I.R.; de Vries, A.L.C.; et al. Self-reported autism spectrum disorder symptoms among adults referred to a gender identity clinic. LGBT Health, 2018; 5(4):226–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skagerberg, E.; Di Ceglie, D.; Carmichael, P. Brief report: Autistic features in children and adolescents with gender dysphoria. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 2015;45(8): 2628–2632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priebe, G.; Svedin, C.G. Operationalization of three dimensions of sexual orientation in a national survey of late adolescents. Journal of Sex Research, 7: 50(8), 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bush, H.H. Self-reported sexuality among women with and without autism spectrum disorder (ASD). Graduate Doctoral Dissertations. 2016; 243. https://scholarworks.umb.edu/doctoral_dissertations/243. (Accessed on 20 Jan 2024).

- World Health Organization. FAQ on health and sexual diversity: An introduction to key concepts. Geneva; 2016. https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/255340/WHO-FWC-GER-16.2-eng.pdf?sequence=1 (Accessed on 20 Jan 2024).

- Byers, S.E.; Nichols, S.; Voyer, S.D. Challenging stereotypes: Sexual functioning of single adults with high functioning autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 2013; 43(11):2617–2627. [Google Scholar]

- Brown-Lavoie, S.M.; Viecili, M.A.; Weiss, J.A. Sexual knowledge and victimization in adults with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 2014; 44(9):2185–2196. [Google Scholar]

- Kanfiszer, L.; Davies, F.; Collins, S. ‘I was just so different: the experiences of women diagnosed with an autism spectrum disorder in adulthood in relation to gender and social relationships. Autism, 2017; 21(6):661–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. 2006. https://www.un.org/disabilities/documents/convention/convoptprot-e.pdf. (Accessed on 20 Jan 2024.

- Nelson, B.K.; Odberg Pettersson, K.; Emmelin, M. Experiences of Teaching Sexual and Reproductive Health to Students with Intellectual Disabilities. Sex Education, 10.1007/s11195-017-9513-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, S.; Kohut, T.; Dillenburger, K. The Importance of Sexuality Education for Children with and without Intellectual Disabilities: What Parents Think. Sexuality and Disability, 2018; 36(2):141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Promoting sexual and reproductive health for persons with disabilities. Geneva, Switzerland. 2009. https://www.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/pub-pdf/srh_for_disabilities.pdf. (Accessed on 20 Jan 2024).

- Dekker, L.P.; van der Vegt, E.J.; Visser, K.; et al. Improving Psychosexual Knowledge in Adolescents with Autism Spectrum Disorder: Pilot of the Tackling Teenage Training Program. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 2015; 45(6): 1532–1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnard-Brak, L.; Schmidt, M.; Chesnut, S.W.; Richman, T.D. Predictors of Access to Sex. Education for Children with Intellectual Disabilities in Public Schools. Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 2014;52(2):85–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, E.B.; Lord, C. Social competence as a predictor of adult outcomes in autism spectrum disorder. Development and Psychopathology, 2020;1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Sala, G.; Hooley, M.; Stokes, M.A. Romantic intimacy in autism: A qualitative analysis. Journal of autism and developmental disorders, 2020;50(11):4133-4147. [Google Scholar]

- Dewinter, J.; Onaiwu, M.G.; Massolo, M.L. , et al. Recommendations for education, clinical practice, research, and policy on promoting well-being in autistic youth and adults through a positive focus on sexuality and gender diversity. Autism, 2023;28(3):770–779. [Google Scholar]

- García-Barba, M.; Nichols, S.; Ballester-Arnal, R.; Byers, E.S. Positive and Negative Sexual Cognitions of Autistic Individuals. Sexuality and Disability, 2024;42(1):167-187. [Google Scholar]

- Sala, G.; Pecora, L.; Hooley, M. , Stokes, M.A. As diverse as the spectrum itself: Trends in sexuality, gender and autism. Curr Dev Disord Rep, 2020;7:59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, S.; Kirby, A.V.; Graham Holmes, L. Autistic narratives of sensory features, sexuality, and relationships. Autism in Adulthood, 2021;3(3):238–246. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, L.F.; Ward, C.; Jarvis, N.; Cawley, E. “Straight sex is complicated enough!”: The lived experiences of autistics who are gay, lesbian, bisexual, asexual, or other sexual orientations. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 2021;51(7):2324–2337. [Google Scholar]

- Yew, R.Y.; Samuel, P.; Hooley, M.; Mesibov, G.B.; Stokes, M.A. A systematic review of romantic relationship initiation and maintenance factors in autism. Personal Relationships, 2021;28(4):777–802. [Google Scholar]

- Mogavero, M.C.; Hsu, K.H. Dating and courtship behaviors among those with autism spectrum disorder. Sexuality and Disability, 2019;38(2):355–364. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, R.; Netto, J.; Gribble, N.C.; Falkmer, M. ‘At the end of the day, it’s Love’: An exploration of relationships in neurodiverse couples. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 2021;51(9):3311–3321. [Google Scholar]

- Dekker, L.P.; van der Vegt, E.J.; Louwerse, A.; et al. Complementing or congruent? Desired characteristics in a friend and romantic partner in autistic versus typically developing male adolescents. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 2023;52(3):1153–1167. [Google Scholar]

- Noble, N.; Bueno, N.; Lourenco, M.; Williams, A.; Stafford, J.; O’Connor, J. College students with autism spectrum disorder’s experiences maintaining romantic relationships: Counseling implications. The Family Journal, 2023;32(1):56–62. [Google Scholar]

- Yew, R.Y.; Hooley, M.; Stokes, M.A. Factors of relationship satisfaction for autistic and non-autistic partners in long-term relationships. Autism, 2023;27(8):2348-2360. [Google Scholar]

- Pecora, L.A.; Hooley, M.; Sperry, L.; Mesibov, G.B.; Stokes, M.A. Sexuality and gender issues in individuals with autism spectrum disorder. The Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 2020.

- Genovese, A. Exploring three core psychological elements when treating adolescents on the autism spectrum: Self-awareness, gender identity, and sexuality. Cureus, 2021; 13(3): e14130. [Google Scholar]

- Joyal, C.C.; Carpentier, J.; McKinnon, S.; Normand, C.L.; Poulin, M.H. Sexual knowledge, desires, and experience of adolescents and young adults with an autism spectrum disorder: An exploratory study. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 2021;12.

- Maggio, M.G.; Calatozzo, P.; Cerasa, A.; et al. Sex and sexuality in autism spectrum disorders: A scoping review on a neglected but fundamental issue. Brain Sciences, 2022; 12(11):1427. [Google Scholar]

- Pecora, L.A.; Hancock, G.I; Hooley, M.; et al. Gender identity, sexual orientation and adverse sexual experiences in autistic females. Molecular Autism, 2020;11(1). [Google Scholar]

- Weir, E.; Allison, C.; Baron-Cohen, S. The sexual health, orientation, and activity of autistic adolescents and adults. Autism Research, 2021;14(11):2342–2354. [Google Scholar]

- Bush, H.H.; Williams, L.W.; Mendes, E. Brief report: Asexuality and young women on the autism spectrum. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 2020;51(2):725–733. [Google Scholar]

- Ronis, S.; Byers, S.; Brotto, L.; Nichols, S. Beyond the label: Asexual identity among individuals on the high-functioning autism spectrum. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 2021;50:3831–3842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillier, A.; Gallop, N.; Mendes, E.; et al. LGBTQ + and autism spectrum disorder: Experiences and challenges. International Journal of Transgender Health. 2019:21(1):98–110.

- Strang, J.F.; Anthony, L.G.; Song, A. , et al. In addition to stigma: Cognitive and autism-related predictors of mental health in transgender adolescents. Journal of clinical child & adolescent psychology, 2023;52(2):212-229.

- Allely, C.S. Autism spectrum disorder, bestiality and zoophilia: A systematic PRISMA review. Journal of Intellectual Disabilities and Offending Behaviour, 2020;11(2):75-91.

- Torralbas-Ortega, J.; Roca, J.; Coelho-Martinho, R.; et al. Affectivity, sexuality, and autism spectrum disorder: qualitative analysis of the experiences of autistic young adults and their families. BMC psychiatry, 2023;23(1):858.

- Strnadová, I.; Danker, J.; Carter, A. Scoping review on sex education for high school-aged students with intellectual disability and/or on the autism spectrum: Parents’, teachers’ and students’perspectives, attitudes and experiences. Sex Education, 2021;22(3):361–378.

- Picard-Pageau, W.; Morales, E. . Interventions on sexuality for adolescents with autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review. Sexuality and Disability, 2022;40(3):599-622.

- Picard-Pageau, W.; Morales, E.; Gagnon, M.P; Ruiz-Rodrigo, A. Co-Design of an Educational Toolkit on Sexuality for Autistic Adolescents and Young Adults. Sexuality and Disability. 2022; 42:149-165. [CrossRef]

- Płatos, M.; Wojaczek, K.; Laugeson, E.A. Fostering friendship and dating skills among adults on the autism spectrum: A randomized controlled trial of the Polish version of the Peers for Young Adults Curriculum. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 2023;54:2224–2239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothman, E.F; Graham Holmes, L.; Caplan, R.; et al. Healthy relationships on the autism spectrum (HEARTS): A feasibility test of an online class co-designed and co-taught with autistic people. Autism. 2022; 26(3): 690-702. [CrossRef]

- Pedgrift, K.; Sparapani, N. The development of a social-sexual education program for adults with neurodevelopmental disabilities: Starting the discussion. Sexuality and Disability, 40(3), 2022, 503–517. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Themes | Sub-themes |

|---|---|

| Intimacy, sexuality and relationships among autistic people. | 1.1. Experiences of intimacy: similarities and differences between autistic and non-autistic participants. 1.2. Sensory processing and sexuality 1.3. Insights from long-term relationships involving autistic individuals. |

| Gender identity and sexual orientation. | 2.1. Gender identity 2.2. Sexual orientation 2.3. Asexuality. |

| Challenges | 3.1. Hypothetical explanations. 3.2. Heightened risk and harsh realities: addressing sexual abuse and victimization in autistic individuals. 3.3. Rethinking sexual health risks in the autistic population. 3.4. Sexual health and autism: navigating challenges and promoting inclusive education and support. 3.5. Barriers to effective sex education. 3.6. Facilitators for improved sex education. 3.7. Innovative strategies for sexual education and relationship skills in autistic individuals. |

| Authors | Year | Pupulation | Demographics | Methods | Key Findigs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Allely | 2020 | Individuals with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) | No specific age or gender data provided | Systematic PRISMA review | Limited research on zoophilia and bestiality in ASD individuals. ASD may be associated with deviant sexual behaviour due to restricted interests or impaired social skills. Importance of sex education for ASD individuals. |

| Ronis et al. | 2021 | 561 individuals with High-Functioning ASD | 21-72 years old, majority Caucasian | Online survey assessing sexual and gender identity | 5.1% self-identified as asexual. Variability in sexual attraction. Asexual identity is linked to social difficulties rather than purely lack of sexual attraction. Researchers should use multidimensional approaches to assess sexual identity. |

| Płatos et al. | 2023 | 15 young adults with ASD | 18-32 years old | Randomised controlled trial of PEERS for Young Adults curriculum | Significant improvement in social cognition and social skills through the PEERS program. Limited improvement in social engagement and dating skills, suggesting need for continued post-treatment support. |

| Rothman et al. | 2022 | 55 autistic individuals | 18-44 years old | Feasibility test of online HEARTS program | Improvement in coping, motivation for socialising, and positive thinking. Interpersonal competence and loneliness did not significantly improve. Participants appreciated having an autistic co-teacher. |

| Sala et al. | 2020 | Autistic individuals | No specific demographics provided | Review of literature | Autistic individuals show higher rates of non-heterosexual attraction, more inappropriate sexual behaviours, and greater gender dysphoria. Issues like courtship and flirting are major challenges. |

| Sala et al. | 2020 | 31 autistic and 26 non-autistic individuals | No specific demographics provided | Online survey with thematic analysis | Both groups desire intimate relationships. Autistic individuals face specific communication difficulties and stigma. Adaptations like clear communication can help overcome barriers. |

| Yew et al. | 2023 | 95 autistic and 65 non-autistic individuals in long-term relationships | No specific demographics provided | Online survey assessing relationship satisfaction factors | Autistic participants reported higher satisfaction in relationships than non-autistic participants. Social loneliness and partner responsiveness were important factors influencing relationship satisfaction. |

| Yew et al. | 2021 | Autistic individuals | No specific demographics provided | Systematic review of romantic relationship initiation and maintenance | Social and communication challenges are the main barriers to relationship satisfaction. Partner support plays a critical role in relationship success. |

| Smith et al. | 2021 | 13 neurodiverse couples | One partner diagnosed with autism | Phenomenological interviews | ND couples experience similar relationship phases as non-ND couples but face unique communication challenges. Support from neurotypical partners is critical. Lack of adequate resources for ND couples was highlighted. |

| Pecora et al. | 2020 | Individuals with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) | Primarily Western, without intellectual disability | Literature review | ASD individuals face difficulties in forming relationships, with increased risks of victimisation and inappropriate sexual behaviours. There’s a high prevalence of non-heterosexuality and gender variance among ASD individuals. |

| Bush et al. | 2020 | Young women with ASD, 18-30 years | No specific demographics provided | Comparative study on asexual spectrum vs. other orientations | Women with ASD on the asexual spectrum report lower generalised anxiety. Sexual satisfaction varies, with asexual individuals finding satisfaction outside of partnered sex. Highlights asexuality as a non-pathological identity. |

| Strnadová et al. | 2021 | High school students with intellectual disability and/or ASD | No specific demographics provided | Scoping review | Limited access to comprehensive sex education for ASD students. Barriers include lack of tailored curricula and societal stigma. Recommendations include early and explicit communication, parent involvement, and practical workshops. |

| Dewinter et al. | 2023 | Autistic youth and adults | No specific demographics provided | Literature review and community-driven recommendations | Emphasis on education, healthcare access, and research for ASD individuals to promote healthy sexual and gender identities. Recommendations to prevent victimisation and increase healthcare professional awareness. |

| Gray et al. | 2021 | 120 autistic individuals | Various sensory profiles | Qualitative analysis | Sensory processing differences affect sexual and relationship experiences for ASD individuals. Sensory sensitivities lead to adaptations in intimacy. Recommendations for targeted support and education on managing sensory aspects in relationships. |

| Weir et al. | 2021 | 2,386 adults, including 1,183 autistic individuals | Age range 16-90 | Anonymized online survey | Autistic individuals display a wider range of sexual orientations and experience similar STI risks. Higher likelihood of non-heteronormative orientation. Need for inclusive sexual health education and healthcare accessibility. |

| Pecora et al. | 2020 | 295 female participants (134 autistic, 161 non-autistic) | Mean age: 26.2 (autistic), 22.0 (non-autistic) | Online survey with Sexual Behaviour Scale-III | Autistic females, especially non-heterosexual, face higher rates of unwanted sexual experiences. Highlights vulnerabilities and the need for tailored interventions for gender-diverse and sexual minority groups within ASD. |

| Clarke & Lord | 2020 | 253 individuals with ASD | Ages 2-26 | Longitudinal cohort study | Social competence in adolescence predicts adult outcomes (employment, independence, friendships). ASD adults face significant barriers in employment and relationships. Suggests the need for personalised success measures for individuals with ASD. |

| Hillier et al. | 2020 | 4 autistic individuals (male, transgender; agender/nonbinary; agender; queer) | Ages 20-38 | Qualitative Analysis | Main themes are experiencing dual identities, autism spectrum, and LGBTQ+; multiple challenges experienced minority status; isolation caused by lack of understanding; lack of service provision. |

| Picard-Pageau & Morales | 2022 | Individuals, with an ASD diagnosis or in regular contact with them (family, therapist, teacher) | Age < 23 years old | Systematic review | Interventions focusing solely on knowledge transfer may not be sufficient to improve behavioural outcomes in youth with ASD. Combining direct intervention with homework or targeting parents may yield better results. School-based interventions show mixed results, while health professional interventions lack conclusive evidence. |

| Dekker et al., | 2023 | 38 male adolescents divided in neurotypical or autistic groups | Age 14-19 | Comparative study | There are no significant differences between groups concerning to what extent partners’ characteristics were desired. Autistic adolescents desire similar characteristics as TD adolescents in their romantic partners and friends. |

| García-Barba et al. | 2024 | 332 participants (57.5% women; 42.5% men) | Age 21-73 | Online Survey and data analysis | In autistic individuals, sexual cognitions are less diverse and occur slightly and frequently than their neurotypical peers; nonetheless, their positive content may be indicative of sexual well-being. |

| Hancock et al. | 2019 | 459 individuals (232 diagnosed with ASD) | Age 5-17 | Online Survey and data analysis | Individuals with ASD experience similar levels of interest in relationships compared to neurotypical peers, but face more challenges in initiating and maintaining them. This is due to difficulties in social interaction and anxiety in social situations. |

| Genovese | 2021 | no participants | Age 10-21 | Narrative review | Autistic adolescents face unique challenges during a developmental period marked by increased social and emotional demands. Their difficulties in social interaction and emotional regulation can hinder their ability to navigate these challenges, potentially leading to emotional distress and behavioral problems. |

| Joyal et al. | 2021 | 194 participants | Age 16-22 | Exploratory study | Individuals with ASD share similar romantic desires and expectations as neurotypical peers, but often have fewer opportunities for sexual experiences. They may also experience difficulties in understanding and navigating sexuality due to limited knowledge and social skills. Early diagnosis and comprehensive sex education can positively impact their sexual experiences. |

| Lewis et al. | 2020 | 67 individuals who identified as autistic sexual minorities | Age >18 | Theme analysis of online interviews | Main themes: self-acceptance as a journey; autistic traits complicate identification of sexual orientation; social and sensory stressors affect sexuality; feeling isolated; challenges in satisfying relationships; difficulty recognizing and communicating sexual needs; a “double minority” status that increases vulnerability in sexual relationships. |

| Maggio et al. | 2022 | 11 articles | Not applicable | Scoping Review | Individuals with ASD may experience atypical sexual development, including higher rates of gender dysphoria and inappropriate sexual behaviours. They often have reduced sexual awareness and a higher prevalence of diverse sexual orientations. Comprehensive sexual health education and support are crucial for improving their quality of life and reducing risky behaviours. |

| Mogavero & Hsu | 2019 | 134 participants, 46 with ASD and 88 without ASD | Age 18-57 | Qualitative Study | Autistic individuals can form successful romantic relationships, but struggle with initiating and maintaining them due to challenges in social skills and communication. Many lack adequate knowledge about romantic relationships. The prevalence of minority sexual orientations and gender identities is higher among autistic individuals, highlighting the importance of inclusive sex education. |

| Noble et al. | 2023 | 124 participants | Age 18-25 | Data Analysis | Autistic students experience both positive and negative aspects of romantic relationships. While they share similar desires for relationships as neurotypical peers, they face challenges due to social communication difficulties and rigid thinking patterns that can lead to increased anxiety, fear of rejection, and difficulties in maintaining relationships. |

| Pedgrift & Sparapani | 2022 | 46 participants | Age 18-29 | Testing of a Sexual Education program | This sexual education tool is a promising program for professionals to use with their adult clients with neurodevelopmental disabilities. |

| Picard-Pageau et al. | 2023 | not specified | Age >18 | Toolkit Design | The tool developed in this study seems to be more relevant for providing support to school-based workers than to specialised clinicians. |

| Strang et al. | 2023 | 93 participants, evenly divided between autistic-transgender, autistic-cisgender, and allistic-transgender groups | Age 13-21 | Data Analysis | Autistic transgender adolescents experience higher levels of internalising symptoms compared to their allistic transgender and autistic cisgender peers. Social difficulties, executive function deficits, and female gender identity contribute to these increased mental health challenges. |

| Torralbas-Ortega et al. | 2023 | 8 participants | Age 14-27 | Qualitative Analysis | Communication and social interaction problems are barriers for young adults in developing affective/sexual relationships, leading to negative feelings and experiences that reinforce avoidance behaviours. Families have poor perception of their ability to provide guidance on the matter. There are reports of poor sex education and lack of support. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).