1. Introduction

Migraine has a high prevalence rate of 8.4% in Japan, and the high proportion of patients in the working age group causes significant socioeconomic losses [

1]. Despite this, the underlying causes and pathogenesis of migraine remain largely unknown. One clue to elucidating the pathomechanism of migraine is to study the genes that cause migraine. Migraine is characterized by two main types: migraine without aura (MO) and migraine with aura (MA) [

2]. Among migraine with aura, familial hemiplegic migraine, in particular, is a subtype of migraine that presents with headache after an aura of hemiplegia [

3].

Currently, the most well-known migraine genes are FHM1, FHM2, and FHM3, which are known as hemiplegic migraine. Hemiplegic migraine is classified as one of the migraine headaches with aura [

3]. Those with a family history of migraine, in particular, are referred to as familial hemiplegic migraine. Currently, there are three major types of the gene, CACNA1A, ATP1A2, and SCN 1A [

4,

5].

The CACNA1A is known not only as the causative gene for FHM type 1, but also for episodic ataxia type 2 (EA type 2) [

6,

7]. Hemiplegic migraine type 1 is characterized by headaches complicated by cerebellar symptoms such as "lightheadedness" and "dizziness," sometimes accompanied by brainstem symptoms. On the other hand, in EA type 2, its clinical manifestation is usually a rare disease with paroxysmal ataxia, usually not accompanied by headache [

6].

FHM2 (ATP1A 2) is the most frequent of the FHMs. Its analysis is also in progress: in FHM2, there are four sodium pump α subunit genes present during its attacks, three of which (α1, α2, and α3) are expressed in the central nervous system, and α2 is α2 is specific to glial cells. Based on cerebral blood flow scintigraphy in Japanese, it is thought to be able to reproduce CSD, and some of it’s mutations showed a preventive effect on lomerizine [

8,

9].

FHM3 caused by SCN1A is considered epidemiologically less frequent than other FHMs. SCN1A encodes the α1 subunit of the neuronal voltage-gated sodium (Nav1.1), which mediates the voltage-dependent sodium ion permeability of excitable membranes of the CNS. Voltage-gated sodium channels play a major role in neuronal excitation. Sodium channels are composed of an α-subunit, which is the main subunit that forms pores (holes through which ions pass), and a β-subunit that regulates the opening and closing of the pore. The α-subunit is expressed in different tissues and organs [

10,

11].

Other hand, Dravet syndrome of severe epilepsies is almost caused by SCN1A mutation [

12,

13]. These SCN1A mutations are caused by epileptic disorders more major than FHM3. Generalized epilepsy with febrile seizures plus 2 (GEFS+2) is a rare autosomal dominant, familial condition with incomplete penetrance and large intrafamilial variability. Patients display febrile seizures persisting sometimes beyond the age of 6 years and/or a variety of afebrile seizure types [

13]. This disease combines febrile seizures, generalized seizures often precipitated by fever at age 6 years or more, and partial seizures, with a variable degree of severity [

14,

15,

16].

In this study, we report our findings on SCN1A mutations causing FHM2 type, its phenotype, and treatment in Japanese patients.

2. Results

2.1. Sequence Analysis, Allele Frequency and Variant Prediction Analysis (Silico Analysis)

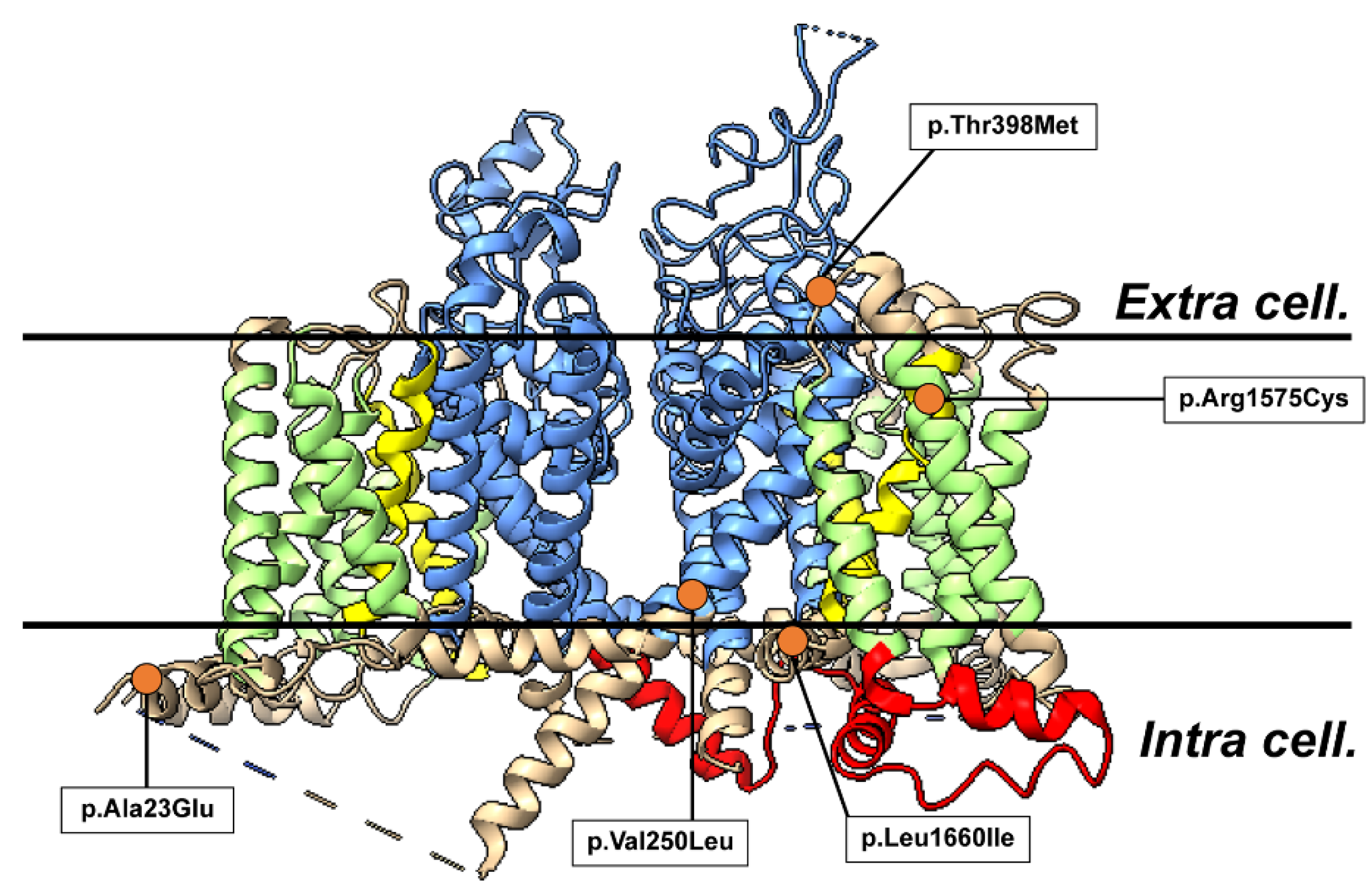

Sequencing of SCN1A was performed using the exome sequencing method in 45 blood samples from clinically suspected patients with familial HM. We detected five heterozygous missense mutations c.68C>A (p.Ala23Glu) of No1 patient, c.748G>C (p.Val250Leu) of No2, c.1193C>T (p.Thr398Met) of No3, c.4723C>T (p.Arg1575Cys) of No4 c.4979C>A ( p.Leu1660Ile) of No5 in SCN1A. Three variants p.Ala23Glu, p.Val250Leu, p.Leu1660Ile had not been reported in the ClinVar database (

Figure 1).

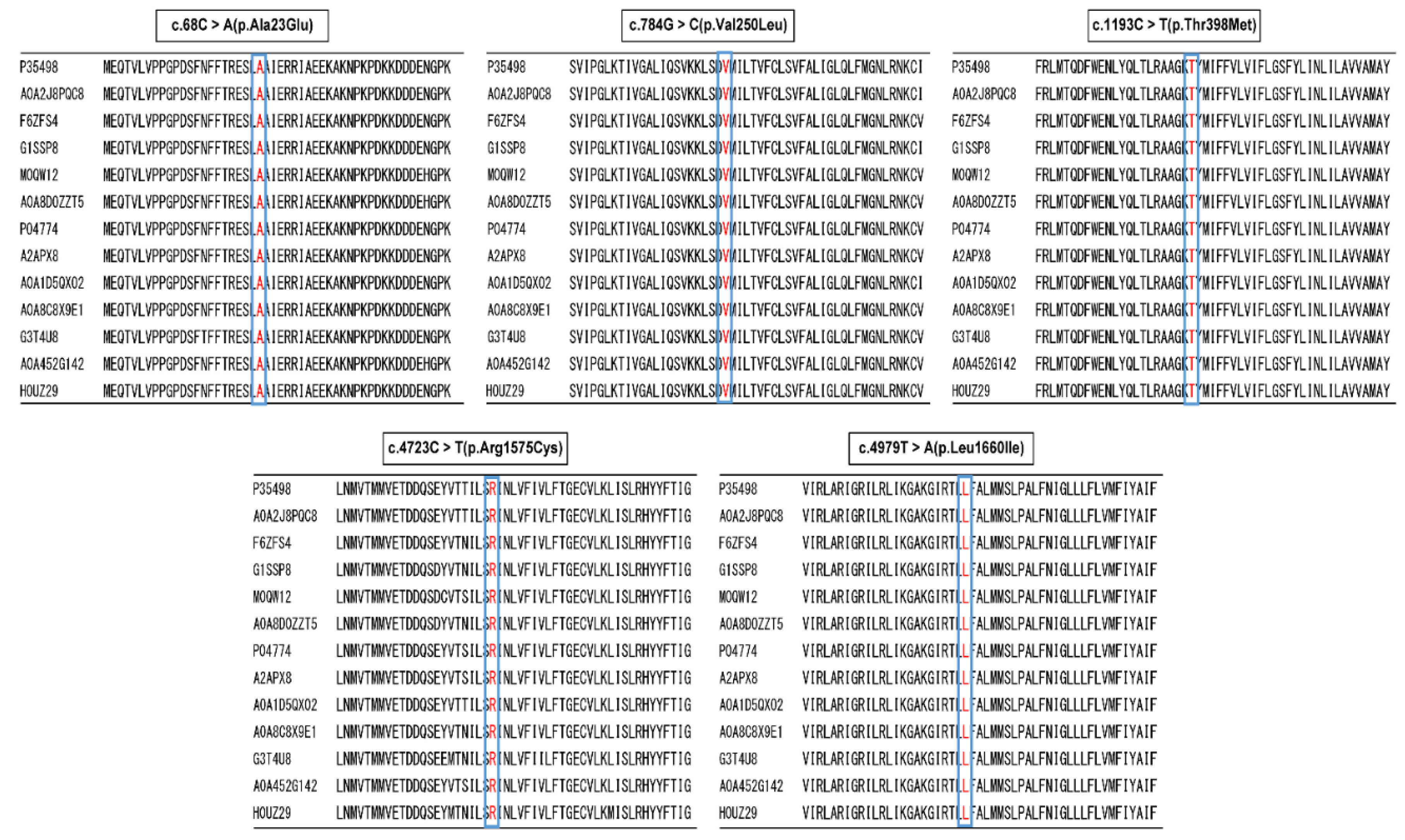

Moreover, all mutation sites were highly conserved across species in many mammals of Amino acid sequence alignment (

Figure 2). The mutations were predicted to lead to the formation of a new salt bridge and of a protein turn around the positive-charged residue. Moreover, these two mutations were not represented in the 1000 Genomes database of the Japanese (

https://ijgvd.megabank.tohoku.ac.jp) or the NCBI ClinVer site (

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar/).

2.2. Allele Frequency and In Silico Analysis

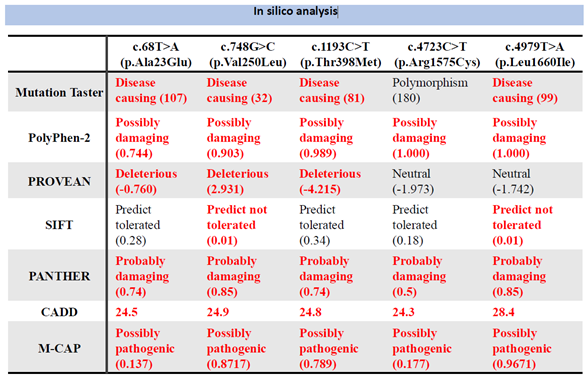

The allele frequencies for East Asians were confirmed by NCBI: No. 1 was 0.0000, No. 2 and No. 5 were not reported, No. 3 was 0.00, and No. 4 was 0.0022. The allele frequencies for Japanese were confirmed by jMorp: No. 1, 2, and 5 were not reported, No. 3 was 0.000646, and No. 4 was 0.0022. The allele frequencies of No. 1, 2, and 5 were not reported from jMorp, No. 3 was 0.000646, and No. 4 was 0.010001. In variant prediction analysis of the seven algorithms yielded the results shown in

Table 1. From the abnormalities, the five variants found in this study were judged to be mutations in SCN1A.

2.3. Three-Dimensional Structural Analysis

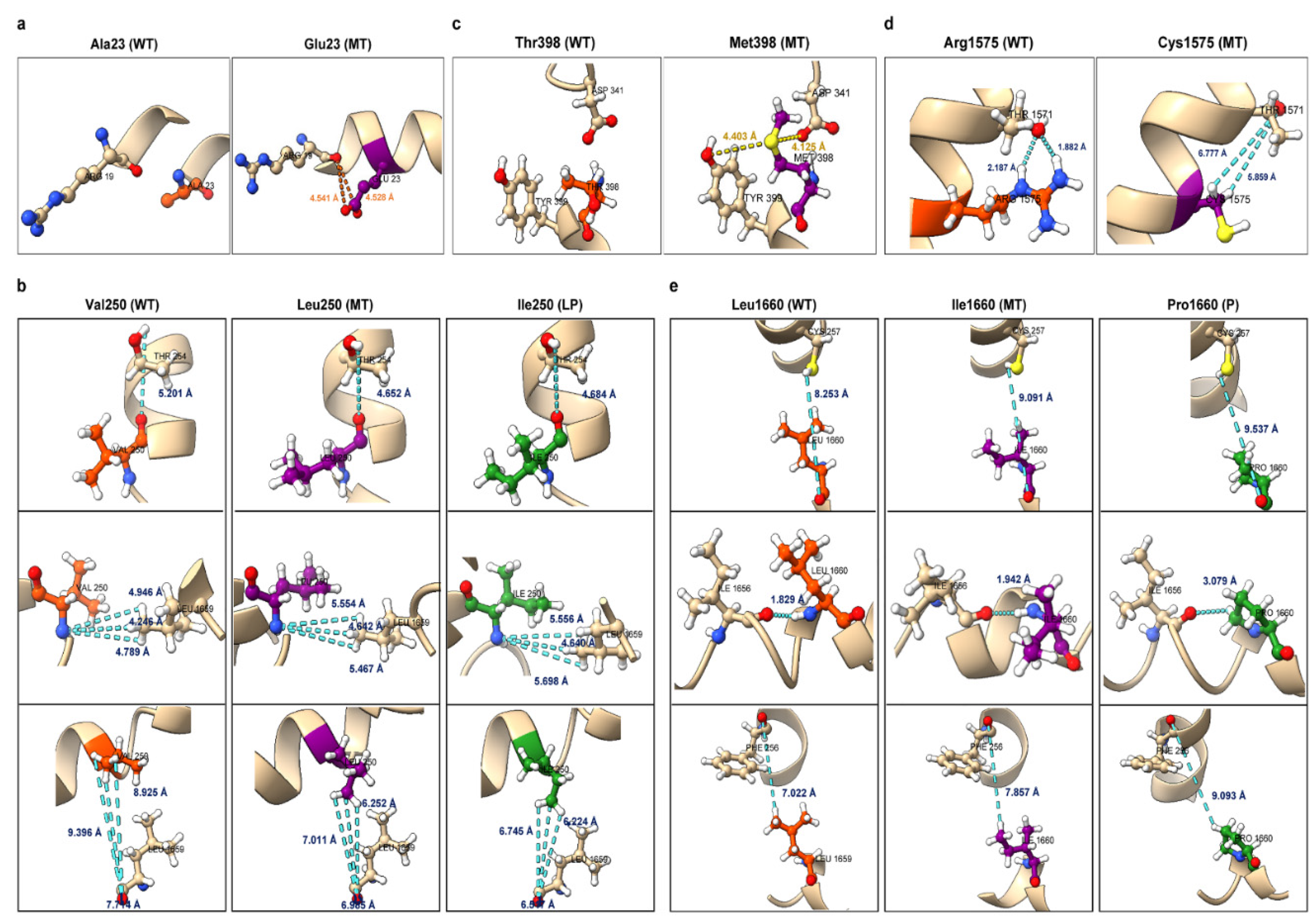

No. 1 was present at the site forming an α-helix in the intracellular loop structure of SCN1A domain I. Comparing the wild type (WT) and the mutant type(MT), the number of peripheral residues within 5 Å of the mutant was increased by one residue. In addition, the No. 1 variant was a change from a hydrophobic to a hydrophilic residue, confirming a change in hydrophobic environment and a change in volume of the side chain (

Figure 3a).

In MT, the distance of the hydrogen bond was elongated and the effect of the hydrogen bond was weakly modified.

Figure 3. e. NM_001165963.4: c.4979T>A (p.Leu1660Ile). Comparing WT and MT, the orientation of the side chain of Cys257 was changed. In addition, MT showed a change in the distance of interaction and peripheral structure similar to that of Pro1660. The Pro1660 substitution at the same site was reported to be pathogenic (P) by ClinVar, and the present mutation was also judged to be pathognomonic mutation.

No. 2 was located in S5 of the pore-forming region of domain I. Comparing the wild-type and mutant forms of No. 2, the number of peripheral residues within 5 Å increased by 2. Hydrogen bonds were observed between Val250 and Thr254 and between Leu250 and Thr254, but at equivalent distances of 1.796 Å and 1.836 Å, respectively (

Figure 3b). Structural changes were observed in the mutant compared to the wild type, such as the α-helix changing to a loop structure and the loop structure changing to an α-helix. Furthermore, Ile250 with the same site substitution has been reported to be Likely pathogenic; comparison of the modeling structure of Leu250 and Ile250 revealed changes in peripheral structure at 9 residues similar to those of Ile250.

No. 3 was located in the extracellular membrane pore of domain I. Comparison of the wild type and the mutant showed that the number of peripheral residues within 5 Å of the mutant was increased by 2 residues. Confirming the interaction between the variant site and the surrounding residues, hydrogen bonds were observed between Thr398 and Asp341, and Met398 and Asp341, but at comparable distances of 1.788 Å and 1.794 Å, respectively (

Figure 3c). New S-O interactions were observed at Ser339, Asp341, and Tyr399, with distances of 7.041 Å, 4.125 Å, and 4.403 Å, respectively. Compared to the wild type, the mutant mutant Ser339 was pulled toward the intracellular side, and a large conformational change was observed. Furthermore, the No. 3 variant was a change from hydrophilic to hydrophobic residues, confirming a change in hydrophobic environment and a change in volume of the side chain.

No. 4 was present in S2 of domain IV. Comparison of the wild type and the mutant showed that the number of peripheral residues within 5 Å was reduced by one residue, and the interaction between the variant site and the peripheral residues was confirmed by ChimeraX and MOE, showing that hydrogen bonds with the side chain of Thr1571 were observed at distances of 1.882 Å and 2.187 Å in the wild type, but these hydrogen bonds disappeared in the mutant. hydrogen bonds were lost in the mutant. Other hydrogen bonds were also observed in the main chains of Arg1575 and Thr1571 and Cys1575 and Thr1571, but at comparable distances of 1.865 Å and 1.847 Å, respectively. Hydrogen bonds were also observed in Arg1575 and Val1579, and Cys1575 and Val1579, with comparable distances of 2.049 Å and 1.979 Å, respectively (

Figure 3d). Furthermore, structural changes were observed, such as changes in the volume of the side chains and the orientation of the side chains around the variant site.

No. 5 was present in the cell between S4 and S5 of domain IV. Comparing the wild type and the variant, the number of peripheral residues within 5 Å increased by one residue and decreased by one residue. Confirming the interaction between the variant site and the surrounding residues, no new interactions were formed or lost; hydrogen bonds were observed between Leu1660 and Arg1657, and Ile1660 and Arg1657, but at comparable distances of 2.266 Å and 2.299 Å, respectively (Figure 17). Hydrogen bonds were also observed between Leu1660 and Ile1656 and Ile1660 and Ile1656, but at comparable distances of 1.829 Å and 1.942 Å, respectively (

Figure 3e). Structural changes were observed in the mutant compared to the wild type, such as the α-helix changing to a loop structure and the loop structure changing to an α-helix. In addition, the same site substitution, Pro1660, has been reported to be Pathogenic; comparison of the modeling structures of Ile1660 and Pro1660 revealed changes in the peripheral structure at 10 residues similar to those of Pro1660.

2.4. Variant Classification

No1variant was reported as a variant of uncertain significance (VUS) of the Clinver data base. But in this variant is extremely low allele frequency in East Asians. In silico analysis predicted pathogenicity for 6/7 algorithms. Conservation of the amino acid sequence was confirmed across four mammalian species identical to humans. Protein modeling localized No 1variant to an α-helical domain I intracellular loop, potentially disrupting structure. As No1 patient experienced childhood seizures, a causal role cannot be excluded. Integrating these data as per ACMG guidelines, No1 variant met criteria for Likely pathogenic. Similarly, when analyzed, No2 satisfied Likely pathogenic criteria and No3 matched Likely pathogenic criteria. No4 was reported as a variant of VUS. The structure of the variant was changed by changes in the volume of the side chains and the orientation of the side chains around the variant site, and it was finally judged to be a pathological mutation. No5 satisfied Likely pathogenic criteria, congruent with its likely detrimental effects. In summary, applying stringent variant curation protocols informed causal inferences for these SCN1A variants identified in our epileptic cohort. Further functional validations are still warranted.

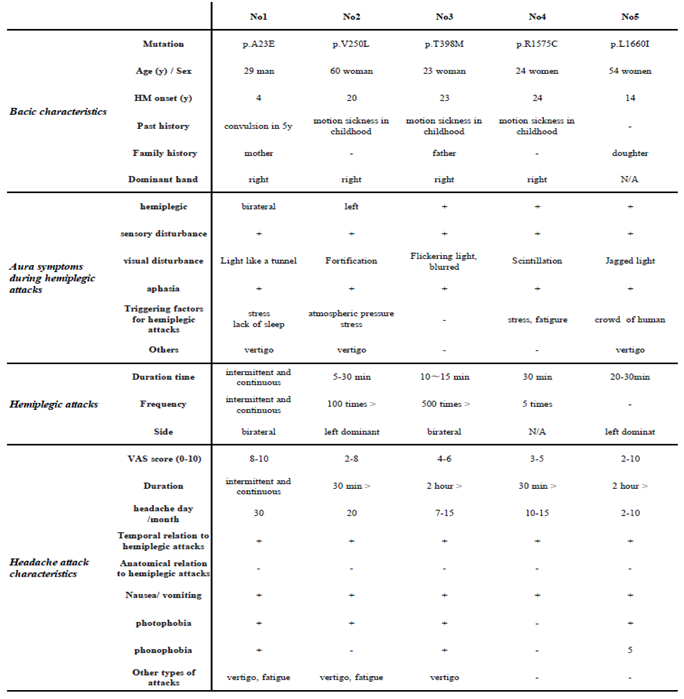

2.5. Clinical Features of Patients

In a clinical and genetic mutation association study, the five patients in whom missense mutations were detected shared common migraine symptoms with typical aura, including visual, sensory, motor, and speech symptoms, as well as dizzy attacks, in addition to headache and paralysis. Among them, visual symptoms such as visual field constriction and light perception were most common. In addition, first attacks were symptomatic from less than 20 years of age (

Table 2). On the other hand, the frequency of headache attacks and the duration and frequency of paralysis differed from case to case. However, no differences in clinical symptoms due to genetic mutations were observed (

Supplements data).

3. Discussion

We performed whole exome sequencing of SCN1A in a proband presenting with headache. Five missense variants were detected within SCN1A and subjected to further investigation. Standardized pathogenicity assessment involved searching public allele frequency databases and applying in silico predictive algorithms to estimate deleteriousness. Sequence conservation was determined across evolutionarily divergent species to infer evolutionary constraints. Protein structural modeling provided insight into potential functional consequences at the tertiary structure level.

Two variants (p. Ala23Glu of No1 patient and p.Val250Leu of No2) were classified as Likely Pathogenic and three variants as a VUS (p.Thr398Met of No3, p.Arg1575Cys of No4 and p.Leu1660Ile of No5) according to the previous clinver database. Three variants (No3, No4 and No5) were predicted to be pathogenic based on structural modeling (Table1 and

Figure 3). As our data, to summarize the present study, five pathological mutations were observed. While public database searches and structural analyses provide useful insights, comprehensive variant curation requires the integration of family history data and reported cases. Further evaluations including co-segregation analysis in biologically related family members as well as functional assays at the cellular level, such as measurements of ion channel currents, will strengthen causal inferences for identified variants. Applying multi-tiered variant assessment strategies offers the best approach for elucidating genotype-phenotype relationships.

The results of the clinical investigation showed that most of the patients in whom the missense variant in SCN1A was detected had migraine symptoms with typical aura, such as visual, sensory, motor, and speech symptoms, and dizzy attacks, in addition to headache and paralysis. Among them, visual symptoms such as visual field constriction and light perception were found to be common in the present patients. In addition, clinical symptoms commonly appeared in adolescents under 20 years of age. On the other hand, the frequency of headache attacks and the duration and frequency of paralysis experienced differed from case to case. We attempted to clarify the differences in clinical symptoms among the variants, but no clear relationship between the five missense variants and clinical symptoms could be confirmed. In the present genetic analysis, we found that some cases with sporadic genetic mutations were found even in the three cases with no family history of the disease. This result suggests that there may be an unexpectedly large number of cases showing de novo mutations in SCA1A, even in cases with no family history. Therefore, cases with hemiplegia or unilateral sensory impairment should be aggressively tested.

Consider the relationship between SHM/FHM and clinical symptoms. The study of severe forms of epilepsy and variants in Dravet syndrome in genetic studies is instructive. The SCN1A gene is also known as the gene for Dravet syndrome, a severe form of childhood epilepsy in which the primary seizure is usually a unilateral or generalized clonic or tonic-clonic seizure with or without fever within the first year of life [

17]. Subsequently, genetic analysis of patients with Dravet syndrome at multiple centers revealed that approximately 80% of the patients had SCN1 A gene mutations [

18,

19]. Dravet syndromes with SCN1 A mutations show a wide spectrum of phenotypes ranging from benign with spontaneous remission to refractory with fatal consequences.

Furthermore, patch-clamp analysis of electrophysiological properties of mutant channel proteins in Dravet syndromes associated with SCN1 A mutations reveals both gain- and loss-of-function phenotypes [

20], and the correlation with clinical symptoms is unclear. However, in more severe phenotypes, including severe myoclonic epilepsy of infancy (SMEI) and SMEI-borderline (SMEB), the rate of missense mutations is decreasing. Missense mutations identified in severe phenotypes occurred more frequently in the pore region of Nav1.1 than those underlying milder phenotypes [

21,

22]. Indeed, in our SHM /FHM studies, few of the proteins in the transmembrane region of the channel, even when present in the transmembrane region, resulted in major protein mutations based on their 3D structure [

23,

24].

Thirdly, it has been shown that the severity of orchitis in Scn1a knockout mice is greatly influenced by the genetic background of the strain [

25]. Nav1.1 is predominantly expressed in the inhibitory GABAergic nervous system compared to the excitatory glutamatergic nervous system.

Therefore, patients with SCN1A gene mutations are thought to have impaired Nav1.1 function (impaired Na+ passage), resulting in reduced function of inhibitory signaling and epileptic seizures [

26,

27]. If an alteration in SCN1A is identified in a patient that results in a more severe alteration of the SCN1A protein (e.g. a frameshift or nonsense mutation that results in a shortening of the protein), the patient is more likely to have a more severe symptomatic SMEI or SMEI-related syndrome rather than SHM or FS symptoms [

23,

24,

25]. These SCN1A-related Dravet syndrome disorders lie at different ends of the SCN1A-disease spectrum reflecting the degree of a loss of function in inhibitory interneurons. Given the underlying loss of function disease mechanism, individuals typically experience seizure exacerbation following sodium channel blocker (SCB) use [

23]. By contrast, a gain of function SCN1A variants are associated with FHM3. Individuals present with a severe subtype of migraine with aura characterized by hemiparesis during the attacks.

Administration of antiepileptic drugs that strongly inhibit Na+ channels in patients with Dravet syndrome leads to exacerbation of seizures [

28]. The reason for this is that SCN1A seizure disorder is inherited in an autosomal dominant manner, so probands with SCN1A seizure disorder may have hereditary or de novo pathogenic variants. the proportion of cases with de novo pathogenic variants depends on the phenotype: parents affected with SCN1A seizure disorder and The proportion of probands with the proband phenotype decreases with increasing severity of the proband phenotype. Thus, most cases of SCN1A-associated pediatric severe myoclonic epilepsy (SCN1A-SMEI) and ICE-GTC are the result of de novo pathogenic variants [

29].

On the other hand, patients with SHM/FHM have milder clinical symptoms than those with DS and are therefore able to carry offspring. Thus, mutations in SCN1A are often passed on to offspring.

In the present study, we investigated SCN1A gene mutations and clinical symptoms in Japanese migraine patients with FHM type 3. At the same time, we examined the form of SCN1A mutations based on previous studies in Dravet syndrome and found that they were in the form of missense mutations, with no major genetic mutations such as truncation mutations or deletion mutations. Further investigation of SHM/FHM and the clinical manifestations and the morphology and structural sites of the genetic mutations is needed.

4. Methods

4.1. Genome DNA Extraction from Peripheral Blood

Blood samples of 50 patients were collected from adults who understood the nature of the study and obtained a consent agreement. Peripheral blood was anticoagulated with sodium heparin and extracted using QIAGEN DNA Blood Mini Kit (QIAGEN). First, 20 μl of Protease K and lysis buffer (Buffer AL 200 μl) were added to 200 μl of whole blood, and incubated at 56°C for 15 minutes. Then 200 μl of 100% ethanol was added, transferred to a spin column, and centrifuged to adsorb the DNA onto the column. The column was washed with two different wash buffers (Buffer AW1 500 μl, Buffer AW2 500 μl) and DNA was extracted with elution buffer (Buffer AE 100 μl).

4.2. The Whole Exome Sequence of SCN1A

Screening of the SCN1A genes was performed using a sequencing analysis. Sequencing reagents were NovaSeq6000 S4 Reagent Kit and NovaSeq Xp 4-Lane Kit, and instruments were NovaSeq6000 for detection. The software NovaSeq Control Software vl.7.0 and Real-Time Analysis v3.4.4 were used. Read sequences obtained by sequencing analysis were mapped to the genome sequence. Duplicate reads were marked from the mapping results, and the 500 bp before and after the SureSelect target region was targeted to detect candidate variant nucleotides that differ from the reference sequence. The detected variant bases were then filtered, and the following annotation information was added using SnpEff and Vcftools. Mutations found by exome analysis were confirmed by direct sequencing.

4.3. Direct Sequencing of SCN1A

Mutations found by whole exome analysis were confirmed by direct sequencing. PCR products and primers were mixed and sequenced. 1.0 μL of BigDye terminator ver. 3.1 Cycle Sequence Mix and 1.5 μL of 5× Sequencing Buffer were added to each tube to make 10 μL. 10 seconds at 96°C and 5 seconds at 50°C) for 30Cycle and 60°C for 4 minutes Cycle sequencing was performed. Ten μL of the reacted sample was mixed with 125 mM EDTA ( pH 8.0) and 100% ethanol, left at room temperature in the dark for 15 minutes and centrifuged (room temperature, 8600 rpm, 5 minutes). The supernatant was removed by flushing, and 100 μL of 70% ethanol was added and centrifuged (room temperature, 8600 rpm, 5 minutes). The supernatant was removed by flushing. 10 μL of HiDi was added and left in the dark for 20 minutes to dissolve. 96°C, 3 minutes for reaction, and analyzed using ABI PRISM 3 130XL or ABI PRISM 3500XL.

4.4. Allele Frequency and in Variant Prediction Analysis (Silico Analysis)

SIFT (Sorting Intolerant From Tolerant) SNP function prediction algorithm analysis first converts the variant list into a VCF format that can be used by SIFT. Coding SNVs Fail to save the file, update the file for SNPs, and perform the analysis. For PolyPhen2, the protein registration number was entered in the protein or SNP identifier for PolyPhen2. If the SNP registration number was available, the number was entered in the Protein or SNP identifier. For Substitution, the amino acid substitution location (codon position) was entered, and the amino acid before amino acid substitution was selected in the upper row, and the amino acid after amino acid substitution was selected in the lower row for analysis [

7,

8,

9]. The mutation was entered in the Alteration field. PROVEAN was used to enter the gene name and protein reference sequence first. For PANTHER, mutant sequences were entered, DI List was selected, microarray IDs were converted to Ensemble IDs, and Homo sapiens was selected and analyzed. CADD (Combined Annotation Dependent Depletion) results are presented as score only, but reports suggest Pathogenic if above 20.0. [

30,

31]. M-CAP (The Mendelian Clinically Applicable Pathogenicity) score is a pathogenicity likelihood score that aims to misclassify no more than 5% of pathogenic variants while aggressively reducing the list of variants of uncertain significance [

32].

4.5. Three-Dimensional Structural Analysis

The crystal structure of the human voltage-gated Na+ channel (7DTD) was obtained from the Protein Data Bank (PDB), and the template structure was created using the Molecular Operating Environment (MOE). The three-dimensional structure of the variant was modeled based on the template structure. For modeling of variant sites for which three-dimensional structures had not been established, LocalColabFold was used. Changes in the surrounding structures and interactions between the wild-type and mutant modeling structures were analyzed using ChimeraX. For some variants, the structures of the variants detected in this study were compared to those of variants with the same site substitution for which virulence evaluations have already been reported and analyzed.

4.6. Variant Classification

It is necessary to evaluate whether variants detected in genetic analysis actually cause disease. The American College of Medical Genetics (ACMG), Association of Molecular Pathology (AMP), and College of American (CAP) jointly published guidelines [

33]. The ACMG guidelines are characterized by evaluating all variants according to multiple criteria for pathogenicity and then synthesizing each evaluation to determine the final pathogenicity.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, KS; Data curation, DD, ItO, NK, KY, YM and TT; Formal analysis, HT and IO; Funding acquisition, KS; Methodology, HT, IO and KS; Project administration, KS; Resources, DD, SK, SK, MS, YM and TT; Software, HT, IO and NK; Supervision, KS; Validation, MH, YN,TT and KS; Visualization, DD, YN and TT; Writing – original draft, HT and KS; Writing – review & editing, DD, NK, MH, KY, YM, YN, TT and KS.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was reviewed and approved by the Kinki University Ethics Committee and Tominaga Hospital (No16-11). Patients were informed in writing of their consent before the study was conducted.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported in part by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology of Japan (Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research, 22K07547).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Sakai, F.; Igarashi, H. Prevalence of migraine in Japan: a nationwide survey. Cephalalgia 1997, 17, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robbins, M.S.; Lipton, R.B. The epidemiology of primary headache disorders. Semin Neurol. 2010, 30, 107–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS). The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition. Cephalalgia 2018, 38, 1–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palvi, G.; Bhardwaj, N.; Ludhiadch, A.; Singh, G.; Munshi, A. Epilepsy and Migraine Shared Genetic and Molecular Mechanism: Focus on Therapeutic Strategies. Molecular Neurobiology 2021, 58, 3874–3883. [Google Scholar]

- Michael, B.R.; Anne, D. Sporadic and familial hemiplegic migraine: pathophysiological mechanisms, clinical characteristics, diagnosis, and management. Lancet Neurol. 2011, 10, 457–470. [Google Scholar]

- Hommersom, M.P.; van Prooije, T.H.; Pennings, M.; Schouten, M.I.; van Bokhoven, H.; Kamsteeg, E.J.; van de Warrenburg, B.P.C. The complexities of CACNA1A in clinical neurogenetics. J Neurol. 2022, 269, 3094–3108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indelicato, E.; Boesch, S. From Genotype to Phenotype: Expanding the Clinical Spectrum of CACNA1A Variants in the Era of Next Generation Sequencing. Front Neurol. 2021, 12, 639994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Tang, W.; Kang, L.; Kong, S.; Dong, Z.; Zhao, D.; Liu, R.; Yu, S. Functional correlation of ATP1A2 mutations with phenotypic spectrum: from pure hemiplegic migraine to its variant forms. J Headache Pain 2021, 22, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oda, I.; Danno, D.; Saigoh, K.; Wolf, J.; Kawashita, N.; Hirano, M.; Samukawa, M.; Kitamura, S.; Kikui, S.; Takeshima, T.; et al. Hemiplegic migraine type 2 with new mutation of the ATP1A2 gene in Japanese cases. Neurosci Res. 2022, 180, 83–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larry, B.; Haerian, B.S.; Ng, H.-K.; et al. Case-control association study of polymorphisms in the voltage-gated sodium channel genes SCN1A, SCN2A, SCN3A, SCN1B, and SCN2B and epilepsy. Hum Genet 2014, 133, 651–659. [Google Scholar]

- Barbieri, R.; Nizzari, M.; Zanardi, I.; Pusch, M.; Gavazzo, P. Voltage-Gated Sodium Channel Dysfunctions in Neurological Disorders. Life (Basel). 2023, 13, 1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matricardi, S.; Cestèle, S.; Trivisano, M.; Kassabian, B.; Leroudier, N.; Vittorini, R.; Nosadini, M.; Cesaroni, E.; Siliquini, S.; Marinaccio, C.; et al. Gain of function SCN1A disease-causing variants: Expanding the phenotypic spectrum and functional studies guiding the choice of effective antiseizure medication. Epilepsia 2023, 64, 1331–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marini, C.; Scheffr, I.E.; Nabbout, R.; Mei, D.; Cox, K.; Dibbens, L.M.; McMahon, J.M.; Iona, X.; Carpintero, R.S.; Elia, M.; et al. SCN1A duplications and deletions detected in Dravet syndrome: implications for molecular diagnosis. Epilepsia 2009, 50, 1670–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, Z.; Li, Y.; Zhao, X.; Li, B. Dravet syndrome: Advances in etiology, clinical presentation, and treatment. Epilepsy Res. 2022, 188, 107041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, J.; Li, X.; Tian, H.; Wang, L.; Guo, B.; Wang, Y.; Li, W.; Wang, F.; Sun, T. SCN1A Mutation-Beyond Dravet Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Narrative Synthesis. Front Neurol. 2021, 12, 743726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scheffer, I.E.; Nabbout, R. SCN1A-related phenotypes: Epilepsy and beyond. Epilepsia. 2019, 60 Suppl 3, S17–S24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohmori, I.; Ouchida, M.; Kobayashi, K.; Jitsumori, Y.; Inoue, T.; Shimizu, K.; Matsui, H.; Ohtsuka, Y.; Maegaki, Y. Rasmussen encephalitis associated with SCN 1 A mutation. Epilepsia. 2008, 49, 521–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Claes, L.; Del Favero, J.; Ceulemans, B.; Lagae, L.; Van Broeckhoven, C.; De Jonghe, P. De novo mutations in the sodium channel gene SCN1A cause severe myoclonic epilepsy of infancy. Am J Hum Genet 2001, 68, 1327–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohmori, I.; Ouchida, M.; Ohtsuka, Y.; Oka, E.; Shimizu, K. Significant correlation of the SCN1A mutations and severe myoclonic epilepsy in infancy. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2002, 295, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohmori, I.; Kahlig, K.M.; Rhodes, T.H.; Wang, D.W.; George, A.L., Jr. Nonfunctional SCN1A is common in severe myoclonic epilepsy of infancy. Epilepsia 2006, 47, 1636–1642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, F.H.; Mantegazza, M.; Westenbroek, R.E.; Robbins, C.A.; Kalume, F.; Burton, K.A.; Spain, W.J.; McKnight, G.S.; Scheuer, T.; Catterall, W.A. Reduced sodium current in GABAergic interneurons in a mouse model of severe myoclonic epilepsy in infancy. Nat Neurosci 2006, 9, 1142–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hız-Kurul, S.; Gürsoy, S.; Ayanoğlu, M.; Yiş, U.; Erçal, D. Expanding spectrum of SCN1A-related phenotype with novel mutations. Turk J Pediatr. 2017, 59, 570–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brunklaus, A.; Brünger, T.; Feng, T.; Fons, C.; Lehikoinen, A.; Panagiotakaki, E.; Vintan, M.A.; Symonds, J.; Andrew, J.; Arzimanoglou, A.; et al. The gain of function SCN1A disorder spectrum: novel epilepsy phenotypes and therapeutic implications. Brain 2022, 145, 3816–3831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, H.; Hu, W.; Kang, Q.; Kuang, X.; Wang, L.; Zhang, X.; Liao, H.; Yang, L.; Yang, H.; Jiang, Z.; et al. Clinical characteristics and genetic analysis of pediatric patients with sodium channel gene mutation-related childhood epilepsy: a review of 94 patients. Front Neurol. 2023, 14, 1310419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogiwara, I.; Miyamoto, H.; Morita, N.; Atapour, N.; Mazaki, E.; Inoue, I.; Takeuchi, T.; Itohara, S.; Yanagawa, Y.; Obata, K.; et al. Na(v)1.1 localizes to axons of parvalbumin positive inhibitory interneurons:a circuit basis for epileptic seizures in mice carrying an Scn1a gene mutation. J Neurosci 2007, 27, 5903–5914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishii, A.; Watkins, J.C.; Chen, D.; Hirose, S.; Hammer, M.F. Clinical implications of SCN1A missense and truncation variants in a large Japanese cohort with Dravet syndrome. Epilepsia 2017, 58, 282–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, H.; Xu, H.Q.; Yu, L.; Lin, G.W.; He, N.; Su, T.; Shi, Y.W.; Li, B.; Wang, J.; Liu, X.R.; et al. The SCN1A mutation database: Updating information and analysis of the relationships among genotype, functional alteration, and phenotype. Hum Mutat 2015, 36, 573–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wirrell, E.C.; Hood, V.; Knupp, K.G.; Meskis, M.A.; Nabbout, R.; Scheffer, I.E.; Wilmshurst, J.; Sullivan, J. International consensus on diagnosis and management of Dravet syndrome. Epilepsia 2022, 63, 1761–1777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, I.O.; Sotero de Menezes, M.A. SCN1A Seizure Disorders. 2007, Nov 29 [updated 2022, Feb 17]. In: Adam, M.P.; Feldman, J.; Mirzaa, G.M.; Pagon, R.A.; Wallace, S.E.; Bean, L.J.H.; Gripp, K.W.; Amemiya A.; editors. GeneReviews® [Internet].

- Rentzsch, P.; Witten, D.; Cooper, G.M.; Shendure, J.; Kircher, M. CADD: predicting the deleteriousness of variants throughout the human genome. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47(D1), D886–D894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kircher, M.; Witten, D.M.; Jain, P.; O'Roak, B.J.; Cooper, G.M.; Shendure, J. A general framework for estimating the relative pathogenicity of human genetic variants. Nat Genet. 2014, 46, 310–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagadeesh, K.A.; Wenger, A.M.; Berger, M.J.; Guturu, H.; Stenson, P.D.; Cooper, D.N.; Bernstein, J.A.; Bejerano, G. M-CAP eliminates a majority of variants of uncertain significance in clinical exomes at high sensitivity. Nat Genet. 2016, 48, 1581–1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, S.; Aziz, N.; Bale, S.; Bick, D.; Das, S.; Gastier-Foster, J.; Grody, W.W.; Hegde, M.; Lyon, E.; Spector, E.; et al.; ACMG Laboratory Quality Assurance Committee Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet Med. 2015, 17, 405–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).