Submitted:

19 January 2025

Posted:

20 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

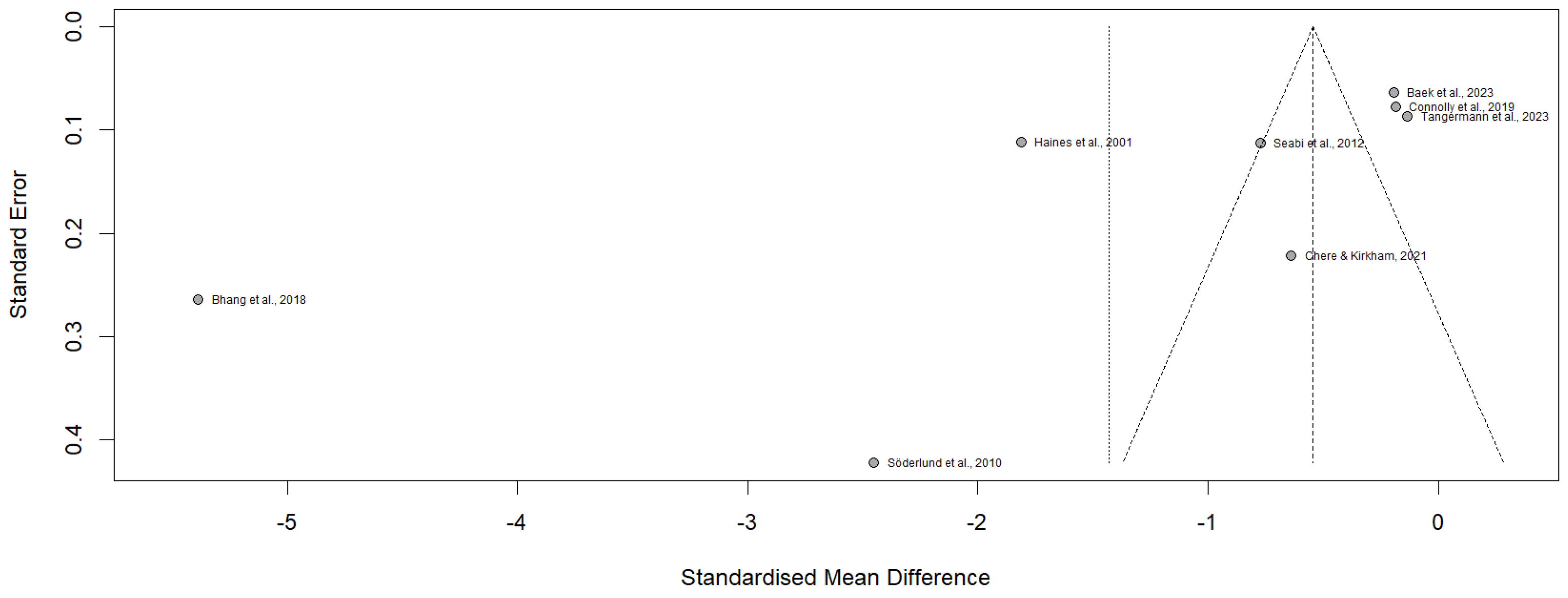

Environmental noise has been consistently associated with adverse effects on cognitive function in children and adolescents. This study aimed to systematically evaluate research examining the impact of noise exposure on young individuals on cognitive function. This meta-analysis systematically reviewed and synthesized findings on the effects of different types of noise from eight original studies published between 2001 and 2023, examining the impact of noise exposure on cognitive performance across various cognitive domains in young populations. Our results indicate that noise exposure exerts a detrimental effect on cognitive performance in children and adolescents, SMD= –0.544, 95% CI [-0.616 to -0.472], z= -14.85; p < 0.0001. These findings demonstrate the significant influence of noise on cognition function.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

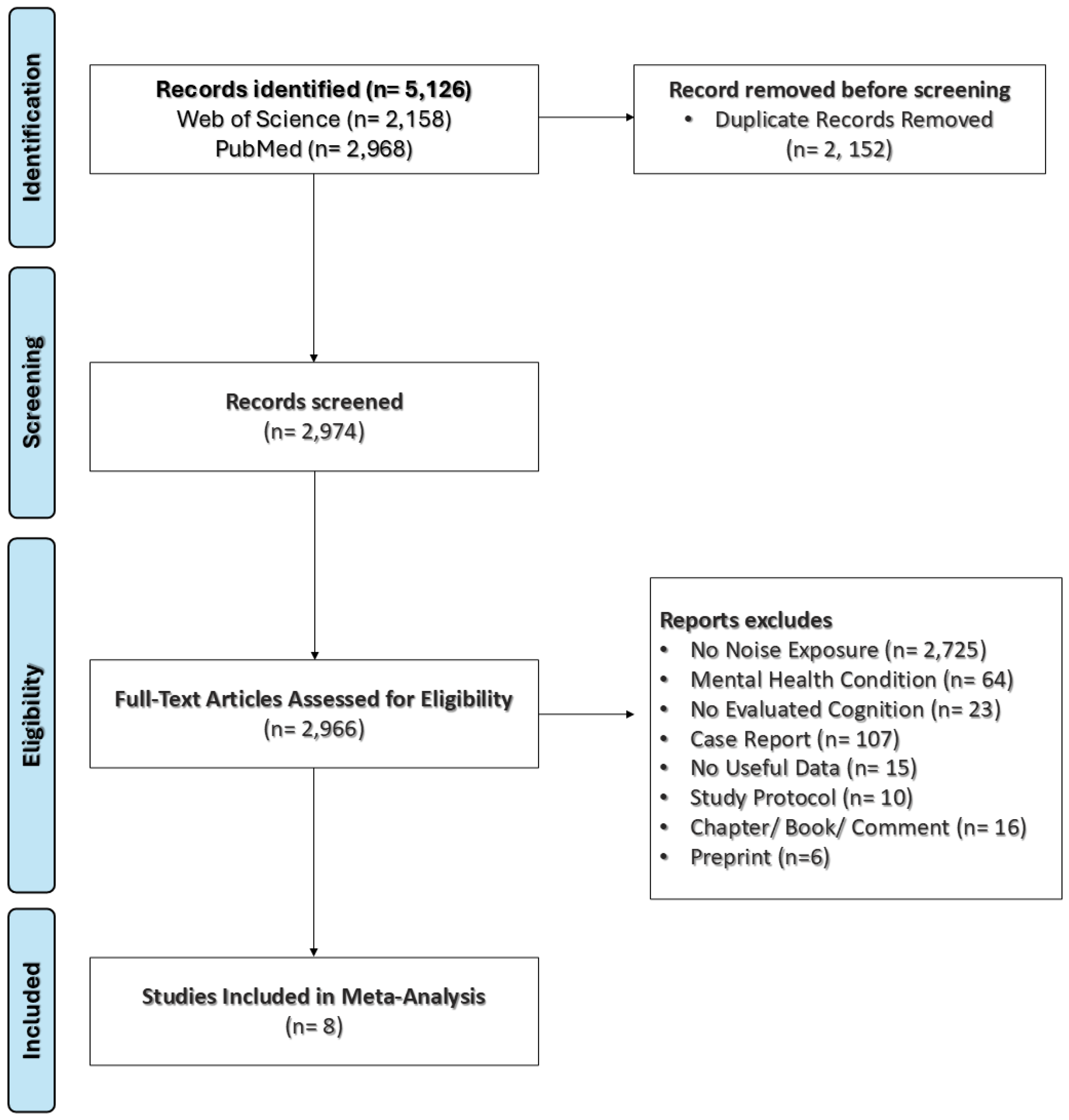

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Data Extraction

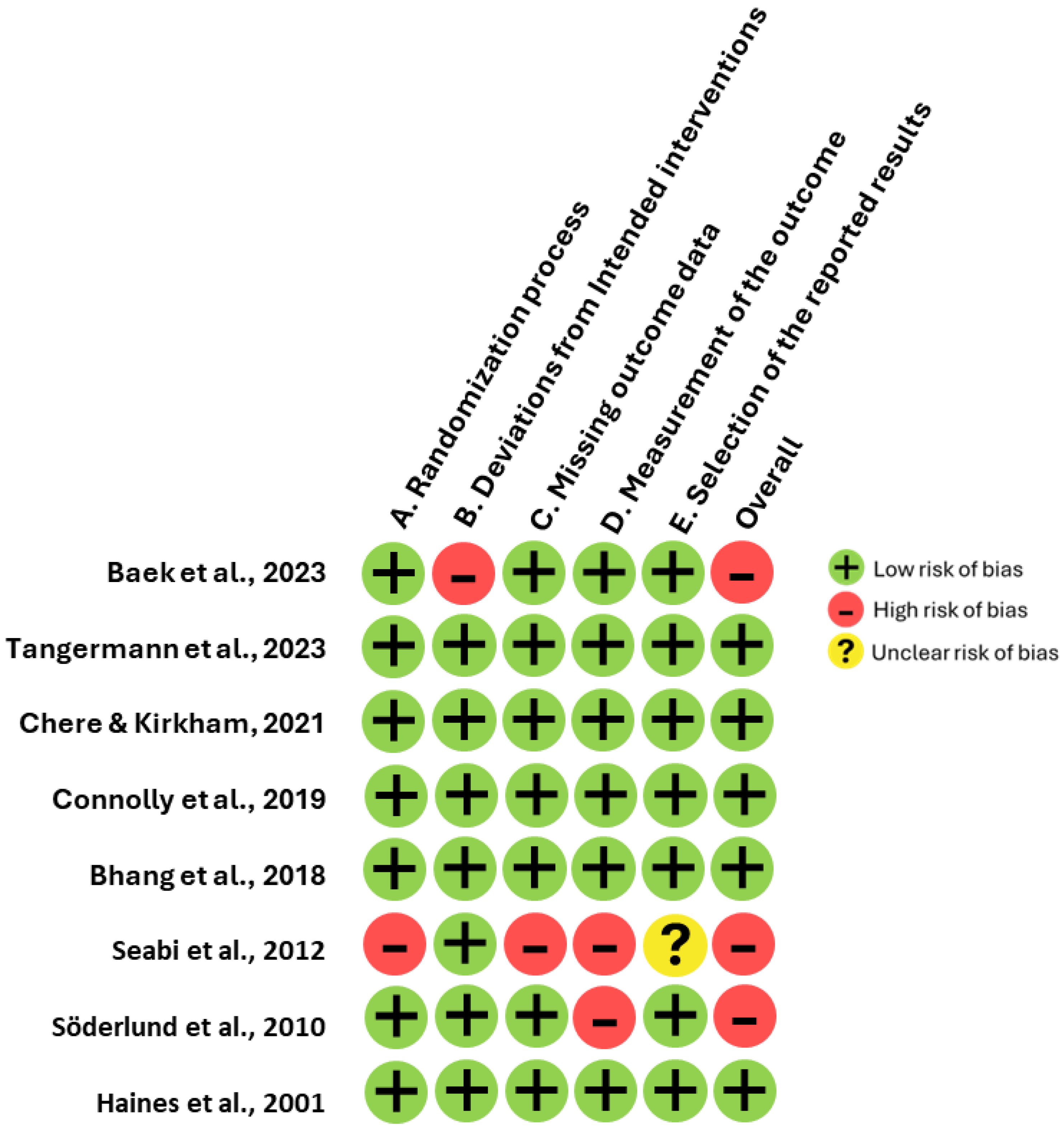

2.4. Quality Evaluation

2.5. Statistical Methods

3. Results

3.1. Study Characteristics

3.2. Impact of Noise Exposure on Cognition Function in Children and Adolescents

3.3. Sensitivity Analysis

3.4. Quality Analysis of Research Reports

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Spiegel, J.A.; Goodrich, J.M.; Morris, B.M.; Osborne, C.M.; Lonigan, C.J. Relations between Executive Functions and Academic Outcomes in Elementary School Children: A Meta-Analysis. Psychological Bulletin 2021, 147, 329–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahad, O.; Kuntic, M.; Al-Kindi, S.; Kuntic, I.; Gilan, D.; Petrowski, K.; Daiber, A.; Münzel, T. Noise and Mental Health: Evidence, Mechanisms, and Consequences. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tangermann, L.; Vienneau, D.; Saucy, A.; Hattendorf, J.; Schäffer, B.; Wunderli, J.M.; Röösli, M. The Association of Road Traffic Noise with Cognition in Adolescents: A Cohort Study in Switzerland. Environmental Research 2023, 218, 115031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chere, B.; Kirkham, N. The Negative Impact of Noise on Adolescents’ Executive Function: An Online Study in the Context of Home-Learning During a Pandemic. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Connolly, D.; Dockrell, J.; Shield, B.; Conetta, R.; Mydlarz, C.; Cox, T. The Effects of Classroom Noise on the Reading Comprehension of Adolescents. J Acoust Soc Am 2019, 145, 372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klatte, M.; Bergström, K.; Lachmann, T. Does Noise Affect Learning? A Short Review on Noise Effects on Cognitive Performance in Children. Front Psychol 2013, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valente, D.L.; Plevinsky, H.M.; Franco, J.M.; Heinrichs-Graham, E.C.; Lewis, D.E. Experimental Investigation of the Effects of the Acoustical Conditions in a Simulated Classroom on Speech Recognition and Learning in Children. J Acoust Soc Am 2012, 131, 232–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhang, S.-Y.; Yoon, J.; Sung, J.; Yoo, C.; Sim, C.; Lee, C.; Lee, J.; Lee, J. Comparing Attention and Cognitive Function in School Children across Noise Conditions: A Quasi-Experimental Study. Psychiatry Investig 2018, 15, 620–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stansfeld, S.A.; Berglund, B.; Clark, C.; Lopez-Barrio, I.; Fischer, P.; Ohrström, E.; Haines, M.M.; Head, J.; Hygge, S.; van Kamp, I.; et al. Aircraft and Road Traffic Noise and Children’s Cognition and Health: A Cross-National Study. Lancet 2005, 365, 1942–1949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herring, C.A.; Simmons, R.K.; Freytag, S.; Poppe, D.; Moffet, J.J.D.; Pflueger, J.; Buckberry, S.; Vargas-Landin, D.B.; Clément, O.; Echeverría, E.G.; et al. Human Prefrontal Cortex Gene Regulatory Dynamics from Gestation to Adulthood at Single-Cell Resolution. Cell 2022, 185, 4428–4447.e28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Söderlund, G.B.; Sikström, S.; Loftesnes, J.M.; Sonuga-Barke, E.J. The Effects of Background White Noise on Memory Performance in Inattentive School Children. Behavioral and Brain Functions 2010, 6, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baek, K.; Park, C.; Sakong, J. The Impact of Aircraft Noise on the Cognitive Function of Elementary School Students in Korea. Noise Health 2023, 25, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seabi, J.; Cockcroft, K.; Goldschagg, P.; Greyling, M. The Impact of Aircraft Noise Exposure on South African Children’s Reading Comprehension: The Moderating Effect of Home Language. Noise Health 2012, 14, 244–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haines, M.M.; Stansfeld, S.A.; Brentnall, S.; Head, J.; Berry, B.; Jiggins, M.; Hygge, S. The West London Schools Study: The Effects of Chronic Aircraft Noise Exposure on Child Health. Psychol Med 2001, 31, 1385–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterne JAC, Savović J, Page MJ, Elbers RG, Blencowe NS, Boutron I, Cates CJ, Cheng H-Y, Corbett MS, Eldridge SM, Hernán MA, Hopewell S, Hróbjartsson A, Junqueira DR, Jüni P, Kirkham JJ, Lasserson T, Li T, McAleenan A, Reeves BC, Shepperd S, Shrier I, Stewart LA, Tilling K, White IR, Whiting PF, Higgins JPT RoB 2: A Revised Tool for Assessing Risk of Bias in Randomised Trials. BMJ 2019, I4898. [CrossRef]

- Shim, S.R.; Kim, S.-J. Intervention Meta-Analysis: Application and Practice Using R Software. Epidemiol Health 2019, 41, e2019008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbas, A.; Hefnawy, M.T.; Negida, A. Meta-Analysis Accelerator: A Comprehensive Tool for Statistical Data Conversion in Systematic Reviews with Meta-Analysis. BMC Medical Research Methodology 2024, 24, 243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wan, X.; Wang, W.; Liu, J.; Tong, T. Estimating the Sample Mean and Standard Deviation from the Sample Size, Median, Range and/or Interquartile Range. BMC Med Res Methodol 2014, 14, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borenstein, M. How to Understand and Report Heterogeneity in a Meta-Analysis: The Difference between I-Squared and Prediction Intervals. Integrative Medicine Research 2023, 12, 101014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Shen, P.; He, T.; Chang, Y.; Shi, L.; Tao, S.; Li, X.; Xun, Q.; Guo, X.; Yu, Z.; et al. Noise Induced Hearing Loss Impairs Spatial Learning/Memory and Hippocampal Neurogenesis in Mice. Scientific Reports 2016, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Quezada, D.; Moran-Torres, D.; Luquin, S.; Ruvalcaba-Delgadillo, Y.; García-Estrada, J.; Jáuregui-Huerta, F. Male/Female Differences in Radial Arm Water Maze Execution After Chronic Exposure to Noise. Noise Health 2019, 21, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández-Quezada, D.; Luquín, S.; Ruvalcaba-Delgadillo, Y.; García-Estrada, J.; Jauregui-Huerta, F. Sex Differences in the Expression of C-Fos in a Rat Brain after Exposure to Environmental Noise. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Quezada, D.; García-Zamudio, A.; Ruvalcaba-Delgadillo, Y.; Luquín, S.; García-Estrada, J.; Jáuregui Huerta, F. Male Rats Exhibit Higher Pro-BDNF, c-Fos and Dendritic Tree Changes after Chronic Acoustic Stress. Biosci Trends 2019, 13, 546–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, B.; Peters, E.; Ettinger, U.; Kuipers, E.; Kumari, V. Understanding Noise Stress-Induced Cognitive Impairment in Healthy Adults and Its Implications for Schizophrenia. Noise and Health 2014, 16, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Westman, J.C.; Walters, J.R. Noise and Stress: A Comprehensive Approach. Environmental Health Perspectives 1981, 41, 291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neuman, A.C.; Wroblewski, M.; Hajicek, J.; Rubinstein, A. Combined Effects of Noise and Reverberation on Speech Recognition Performance of Normal-Hearing Children and Adults. Ear Hear 2010, 31, 336–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babisch, W. The Noise/Stress Concept, Risk Assessment and Research Needs. Noise and Health 2002, 4, 1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Faisal, A.A.; Selen, L.P.J.; Wolpert, D.M. Noise in the Nervous System. Nature Reviews Neuroscience 2008, 9, 292–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spreng, M. Central Nervous System Activation by Noise. Noise Health 2000, 2, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zijlema, W.L.; de Kluizenaar, Y.; van Kamp, I.; Hartman, C.A. Associations between Road Traffic Noise Exposure at Home and School and ADHD in School-Aged Children: The TRAILS Study. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2021, 30, 155–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Münzel, T.; Sørensen, M.; Gori, T.; Schmidt, F.P.; Rao, X.; Brook, J.; Chen, L.C.; Brook, R.D.; Rajagopalan, S. Environmental Stressors and Cardio-Metabolic Disease: Part I-Epidemiologic Evidence Supporting a Role for Noise and Air Pollution and Effects of Mitigation Strategies. Eur Heart J 2017, 38, 550–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Münzel, T.; Daiber, A. Environmental Stressors and Their Impact on Health and Disease with Focus on Oxidative Stress. Antioxid Redox Signal 2018, 28, 735–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henry, J.P. Biological Basis of the Stress Response. Integr Physiol Behav Sci 1992, 27, 66–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molitor, M.; Bayo-Jimenez, M.T.; Hahad, O.; Witzler, C.; Finger, S.; Garlapati, V.S.; Rajlic, S.; Knopp, T.; Bieler, T.K.; Aluia, M.; et al. Aircraft Noise Exposure Induces Pro-Inflammatory Vascular Conditioning and Amplifies Vascular Dysfunction and Impairment of Cardiac Function after Myocardial Infarction. Cardiovasc Res 2023, 119, 1416–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, I.; Kim, J.; Jung, S.; Kim, S.Y.; Kim, E.J.; Choo, S.; Kam, E.H.; Koo, B.-N. The Impact of Persistent Noise Exposure under Inflammatory Conditions. Healthcare (Basel) 2023, 11, 2067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farahbakht, E.; Alsinani, Y.; Safari, M.; Hofmeister, M.; Rezaie, R.; Sharifabadi, A.; Jahromi, M.K. Immunoinflammatory Response to Acute Noise Stress in Male Rats Adapted with Different Exercise Training. Noise Health 2023, 25, 226–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daiber, A.; Kröller-Schön, S.; Frenis, K.; Oelze, M.; Kalinovic, S.; Vujacic-Mirski, K.; Kuntic, M.; Bayo Jimenez, M.T.; Helmstädter, J.; Steven, S.; et al. Environmental Noise Induces the Release of Stress Hormones and Inflammatory Signaling Molecules Leading to Oxidative Stress and Vascular Dysfunction-Signatures of the Internal Exposome. Biofactors 2019, 45, 495–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Jiang, W.-J.; Wang, Y.-P.; Si, J.-Q.; Zeng, X.-S.; Li, L. CD36-Mediated ROS/PI3K/AKT Signaling Pathway Exacerbates Cognitive Impairment in APP/PS1 Mice after Noise Exposure. Sci Total Environ 2024, 952, 175879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.; Xiong, H.; Sha, S. Noise-Induced Loss of Sensory Hair Cells Is Mediated by ROS/AMPKα Pathway. Redox Biol 2020, 29, 101406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variables | Search Fields | Keyword |

|---|---|---|

| Independent | All Fields | Noise, acoustic, environmental noise, chronic noise, broadband, white noise |

| Dependent | All Fields | Cognition, cognitive, cognitive function, memory, learning, attention |

| Population | All Fields | Children, minor, youths, young, adolescents |

| study | n1 | m1 | s1 | n2 | m2 | s2 | md | sd | se | cohen_d | cohen_se |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baek et al., 2023 |

480 | 105.9 | 15.57 | 509 | 109.0 | 16.30 | -3.1 | 15.9499 | 0.5472 | -0.2 | 0.0637 |

| Tangermann et al., 2023 | 287 | 7.5 | 2.98 | 252 | 7.9 | 2.98 | -0.4 | 2.9800 | 0.2573 | -0.1 | 0.0915 |

| Chere & Kirkham, 2021 |

43 | 132.85 | 176.67 | 43 | 285.72 | 285.42 | -152.57 | 237.3572 | 51.1898 | -0.6 | 0.2205 |

| Connolly et al., 2019 |

335 | 6.7 | 3.2 | 334 | 7.4 | 4.3 | -0.7 | 3.7893 | 0.2930 | -0.2 | 0.0775 |

| Bhang et al., 2018 |

134 | 110.04 | 1.29 | 134 | 116.54 | 1.11 | -6.5 | 1.2034 | 0.1470 | -5.4 | 0.1296 |

| Seabi et al., 2012 |

151 | 30.16 | 13.76 | 191 | 40.95 | 14.06 | -10.79 | 13.9284 | 1.5167 | -0.8 | 0.1154 |

| Söderlund et al., 2010 |

21 | 0.41 | 0.02 | 20 | 0.46 | 0.02 | -0.05 | 0.0200 | 0.0062 | -2.5 | 0.3323 |

| Haines et al., 2001 |

236 | 37.11 | 1.02 | 215 | 38.97 | 1.03 | -1.86 | 1.0248 | 0.0019 | -1.8 | 0.1000 |

| First author | Year | Country | Sex (male/ female) | Noise source |

Noise value (dB) | Exposure assessment | Place of exposure | Age | Outcome | Measurement |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baek | 2023 | Korea | 520/469 | Aircraft Noise | 75≤80 dB | WECPNL | Schools | 10–11 | IQ | KIT-P |

| Tangermann | 2023 | Switzerland | 432/340 | Home Road Traffic Noise | >55 dB | SiRENE project | Home | 13-15 | Memory | IST |

| Chere & Kirkham | 2021 | UK | 72/88 | Environmental Noise | Perception of Noise | Questionnaire | Home | 11-14 | Executive function | Flanker (∆RT Accuracy score) |

| Connolly | 2019 | UK | Not reported | Sound events (chair, scrapes, pencil drops, and movement) | 70 dB LAeq | HATS | Schools | 11-16 | Learning | The reading task (latency word learning) |

| Bhang | 2018 | Korea | 135/133 | Road Traffic/ Aircraft Noise | 60.8–62.8 dB | NS | Schools | 10-12 | IQ | KEDI-WISC |

| Seabi | 2012 | South Africa | 322/331 (181 did not respond) |

Aircraft Noise | LAeq > 69-95 dBA | SVAN 955 Type 1 |

Schools | 09-14 | Learning | SRS2 |

| Söderlund | 2010 | Sweden | 21/20 | White Noise | 78 dB | NS | Schools | 11-12 | Memory | Verbal episodic recall test |

| Haines | 2001 | UK | 229/222 | Aircraft Noise | Leq > 63 dBA | NS | Schools | 08-11 | Memory and attention | Suffolk Reading Scale |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).