1. Introduction

Metabolic syndrome (MetS) has become a global health concern, with a prevalence ranging from 12.5% to 31.4% according to various definitions [

1]. Notably, in the United States, the prevalence increased to 34.7% (95% CI, 33.1–36.3) between 2011 and 2016, indicating an increasing trend [

2]. The associations between MetS status and the risk of experiencing adverse health outcomes, including cardiovascular disease (CVD) and mortality, have been extensively investigated, revealing significantly elevated risks of CVD (RR: 2.35; 95% CI, 2.02–2.73), CVD mortality (RR: 2.40; 95% CI, 1.87–3.08), and all-cause mortality (RR: 1.58; 95% CI, 1.39–1.78) in individuals with MetS compared with control participants [

3].

Effective lifestyle modifications, such as aerobic exercise and dietary changes, have shown promise in mitigating MetS, as evidenced by various systematic reviews and meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) demonstrating improvements in biomarkers such as body mass index (BMI), insulin resistance, and visceral fat [

4,

5,

6,

7].

In Japan, significant efforts, backed by a budget of approximately 21.15 billion yen, have been invested in health guidance initiated by the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (MHLW) to combat MetS through lifestyle enhancements [

8]. However, the effectiveness of these interventions has been questioned, particularly in terms of achieving clinically meaningful weight loss, as demonstrated by a study revealing no association between receiving specific health guidance and experiencing substantial weight loss in men [

9]. Alarmingly, despite these initiatives, the number of people with MetS and potential MetS in Japan has continued to rise, with a slowing rate of decline observed from 2016 to 2020 [

10]. This underscores the need for more effective health guidance strategies.

While some cohort studies in Japan have explored the relationships between lifestyle factors and the risk of developing MetS in specific age groups, such as young and middle-aged individuals, no large-scale cohort studies encompassing all adult generations have been conducted. Moreover, the identification of lifestyle factors negatively associated with the risk of developing MetS remains contentious, with conflicting findings in existing research. For example, a study targeting middle-aged adults associated weight gain and eating before bedtime with the risk of developing MetS [

11], whereas another study focusing on young adults linked smoking and rapid eating to the development of MetS [

12]. Thus, the aim of this study was to bridge these gaps by comprehensively investigating lifestyle factors negatively associated with the risk of developing MetS across all adult age groups through a large-scale cohort analysis.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

A retrospective open cohort study was conducted.

2.2. Participants

The inclusion criteria encompassed individuals aged 18 years or older who attended their initial medical checkup at St. Luke's International Hospital Clinic Preventive Medical Center in Japan between January 1, 2012, and December 31, 2022. Participants were included if they remained free from MetS at their first visit and underwent a subsequent medical checkup more than ten months apart within the specified target period.

The exclusion criteria included individuals deemed at high risk for coronary artery disease, as determined by a Suita score of 56 points or more [

13]; those actively taking medication for blood pressure (BP), blood sugar, or lipids; those undergoing artificial dialysis, and pregnant women.

2.3. Data Collection

Data collection involved extracting information from both the health checkup questionnaire and subsequent health checkup results conducted approximately one year later. The parameters utilized for assessing MetS included waist circumference (WC), BMI, systolic BP (SBP), diastolic BP (DBP), high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol, triglycerides (TGs), and fasting blood sugar (FBG).

Specifically, lifestyle factor data were obtained from the Health Checkup Questionnaire provided by the MHLW (refer to the Supplementary Material). Information such as age, sex, medical history, medication use, weight, height, BMI, blood liver function, blood renal function, and general blood parameters was collected from the medical examination results.

2.4. Outcomes and Criteria

The primary outcome of interest was the time to the development of MetS from the baseline date. MetS was defined according to specific criteria, including a WC of 85 cm or more for men and 90 cm or more for women, plus meeting at least two of the following three criteria: elevated BP, abnormal lipid levels, and high blood sugar. These criteria included SBP ≥130 mmHg and/or DBP ≥85 mmHg, TG ≥150 mg/dL and/or HDL cholesterol <40 mg/dL, and FBG ≥110 mg/dL [

14].

Covariates included sex, age, height, weight, BMI, BP, blood sugar-related parameters, blood cell-related parameters, blood lipid-related parameters, liver function, uric acid (UA), renal function, and lifestyle factors (as listed in

Table S1). The independent variables entered into the Cox proportional hazards model included those that demonstrated significance in the univariate analysis (

Tables S2 and S3) and those previously associated with the risk of developing MetS in relevant studies.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

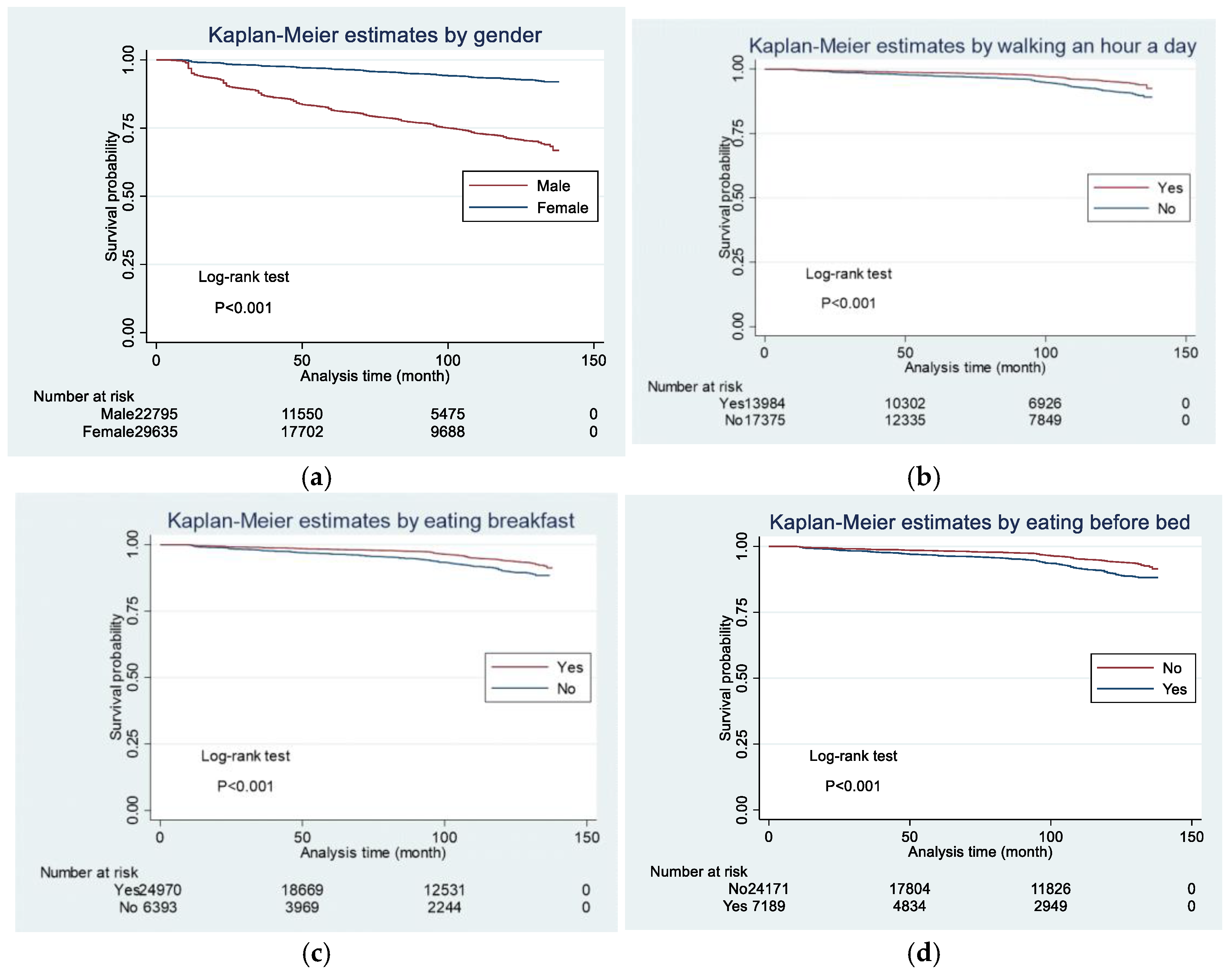

The characteristics of the subjects were divided into a MetS group and a non-MetS group and compared. The chi-square test was used to compare categorical data, and the t test was used to compare the means of continuous data. A Kaplan‒Meier curve was drawn for the time it took to develop MetS, and a log-rank test was conducted. Cox proportional hazards analysis was subsequently performed. Hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% CIs are shown. P values were two-tailed, and values <0.05 were considered to indicate statistical significance. Adjustments were made for confounding factors. The preconditions for proportional hazards were confirmed. The statistical software used was STATA SE-17 (64-bit, College Station, Texas, USA).

2.6. Ethics Statement

This study protocol underwent submission to the data provider hospitals, assuring the anonymization of the data, and subsequently received approval from the responsible personnel. The data handling processes were exclusively managed by the researcher and took place in a controlled environment, either at St. Luke’s International University graduate school or at the researcher's home. Stringent security measures, including password protection on personal computers, were implemented to safeguard the data. Ethical approval for this research was obtained from St. Luke’s Ethics Review Committee (approval code: 23-R041).

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the Participants

The study included 52,516 subjects, with 5,482 (10.4%) developing MetS. Within this cohort, 4.2% of women and 18.6% of men developed MetS. The mean age was 52.1 years in the MetS group and 52.2 years in the non-MetS group, with a mean BMI of 25.9 kg/m² in the MetS group and 21.7 kg/m² in the non-MetS group (

Table 1). The median time to onset of MetS during the observation period was not available.

3.2. Factors Related to the Onset of MetS According to Kaplan‒Meier Curves

Kaplan‒Meier curves revealed that men developed MetS significantly earlier than women did, as determined by the log-rank test (p<0.001) (

Figure 1a). Similarly, individuals who walked less than one hour a day (

Figure 1b), skipped breakfast three or more days a week (

Figure 1c), and ate within two hours before bedtime three or more days a week (

Figure 1d) demonstrated a significantly earlier onset of MetS (p<0.001).

3.3. Lifestyle Factors and Parameters Associated with the Development of MetS Using Cox Proportional Hazards Models

The Cox proportional hazards model revealed that male sex had the strongest association with the risk of developing MetS (HR=2.37, p<0.001), followed by the red blood cell (RBC) count (HR=1.73, p<0.001) and BMI (HR=1.32, p<0.001) (

Table 2). According to the Cox proportional hazards model, the lifestyle factor with the lowest hazard ratio was walking for an hour a day (HR=0.72, p<0.001) (

Table 2). This was followed by skipping breakfast less than three times a week (HR=0.80, p=0.001) and eating dinner within two hours before going to bed less than three times a week (HR=0.85, p=0.009) (

Table 2). Interestingly, walking for more than one hour a day (HR=0.72) was more negatively associated with the risk of developing MetS than having a low BMI (HR=0.76). The number of people who skipped breakfast three or more days a week was 6,396 out of 31,369, constituting 20.4%. Notably, the rate of skipping breakfast increased with younger age: 35.9% for those under 39 years old, 25.5% for those in their 40s, 18.8% for those in their 50s, and 10.2% for those in their 60s (data is not shown).

3.4. Stratified Analysis of Factors Related to the Onset of MetS

In stratified analyses, age stratification revealed that male sex and BMI were associated with the risk of developing MetS in all generations (

Table 3,

Table 4,

Table 5 and

Table 6). Additionally, walking for more than one hour a day was negatively associated with the risk of developing MetS in both sexes (

Table 7 and

Table 8) and all age groups, except those under 39 years old and those in their 60s (

Table 3,

Table 4,

Table 5 and

Table 6).

4. Discussion

4.1. Key Findings

In this study, we analyzed data from 52,516 subjects, of whom 5,482 (10.4%) developed MetS. The Cox proportional hazards model revealed that male sex presented the strongest association with the risk of developing MetS, followed by a high red blood cell (RBC) count, high BMI, high UA, and frequent alcohol consumption. The lifestyle factors with the strongest negative associations with the risk of developing MetS included walking for more than one hour a day, skipping breakfast less than three days a week, and eating within two hours before going to bed less than three days a week.

Age-stratified analysis revealed that male sex and BMI were consistently associated with the risk of developing MetS across all generations. Notably, the RBC count was strongly associated with the risk of developing MetS in all age groups and sexes, except those under 39 years of age and those in their 60s. Smoking and sleep apnea syndrome, which are known to influence red blood cell parameters [

15,

16], may contribute to the observed associations.

Lifestyle factors that were negatively associated with the risk of developing MetS varied by age group and sex. For example, walking for more than one hour a day was negatively associated with the risk of developing MetS in people in their 40s and 50 s, while eating within two hours before going to bed less than three days a week was negatively associated with the risk of developing MetS in people in their 40s and eating slowly in people in their 60s.

Sex-stratified analysis revealed that walking for more than one hour daily was negatively associated with the risk of developing MetS in both men and women, whereas skipping breakfast less than three days a week was negatively associated with the risk of developing MetS only in men. This suggests the importance of tailoring health guidance on the basis of both age- and sex-specific factors.

4.2. Social Implications

In Japan, where specific health guidance consumes a significant portion of the national budget, the findings underscore the need for effective and targeted interventions. While current evaluation indicators include weight, WC, and behavioral changes [

17], future indicators related to metabolism, such as muscle mass, may provide additional insights.

4.3. Strengths and Limitations of the Study

Consistent with the findings of previous studies [

18,

19], our findings reaffirm the higher prevalence of MetS among men in Japan. The positive associations of greater BMI and alcohol consumption and the negative association of light exercise with the risk of developing MetS observed in the present study align with the findings of previous studies [

12,

19,

20,

21]. However, our study diverges from prior research by highlighting the unique negative associations of walking for more than an hour a day and not skipping breakfast with the risk of developing MetS. These lifestyle factors, which are relatively easy to incorporate into daily life, hold promise for preventing MetS with potential long-term adherence. Although the energy intake of Japanese people is decreasing [

22], the incidence of MetS is increasing [

10]. A scoping review of observational studies examining the relationship between high protein intake at breakfast and increased muscle mass revealed that approximately 58.8% of the 11 studies showed participants had increased muscle mass [

22]. Eating protein at breakfast is also associated with more significant muscle mass gain than eating protein at other meals [

23]. This means that to reduce MetS it may be essential not only to reduce body weight and WC but also to increase basal metabolism by increasing muscle mass through the consumption of protein at breakfast and engaging in an appropriate walking routine. This suggests the need to add outcomes that measure metabolism, such as muscle mass, to health guidance that uses only current weight and WC as outcomes.

Despite its strengths, this study has several limitations. Self-reported lifestyle factors may introduce bias, and data from a single center may limit generalizability. The lower MetS incidence rate in our study compared with the national average raises concerns about potential underestimation of new-onset MetS. Further research with more extensive data is necessary to increase the applicability of these findings to national health guidance.

5. Conclusions

These findings suggest that certain lifestyle factors may serve as preventive measures against MetS, including engaging in a daily one-hour walk, regular breakfast consumption, and refraining from eating before bedtime. To further advance our understanding and refine these observations, future research endeavors should focus on collecting more extensive and diverse data.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Table S1: Characteristics of all participants by MetS status; Table S2: Hazard ratios for univariate analysis; Table S3: Hazard ratios for univariate analysis by criteria category.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.U.; methodology, K.U. and S.O.; software, K.U. and S.O.; validation, K.U., T.A., and S.O.; formal analysis, K.U. and S.O.; investigation, K.U.; literature review, K.U.; writing—original draft preparation, K.U.; writing – review & editing, K.U., T.A., and S.O; supervision, S.O.

Funding

This research received no external Funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical approval for this research was obtained from St. Luke’s Ethics Review Committee (approval code: 23-R041).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to all the participants in this study and to St. Luke's International Hospital for providing the data.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Noubiap, J.J.; Nansseu, J.R.; Lontchi-Yimagou, E.; Nkeck, J.R.; Nyaga, U.F.; Ngouo, A.T.; Tounouga, D.N.; Tianyi, F.L.; Foka, A.J.; Ndoadoumgue, A.L.; et al. Geographic distribution of metabolic syndrome and its components in the general adult population: A meta-analysis of global data from 28 million individuals. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2022, 188, 109924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirode, G.; Wong, R.J. Trends in the prevalence of metabolic syndrome in the United States, 2011-2016. JAMA 2020, 323, 2526–2528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mottillo, S.; Filion, K.B.; Genest, J.; Joseph, L.; Pilote, L.; Poirier, P.; Rinfret, S.; Schiffrin, E.L.; Eisenberg, M.J. The metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular risk a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2010, 56, 1113–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ostman, C.; Smart, N.A.; Morcos, D.; Duller, A.; Ridley, W.; Jewiss, D. The effect of exercise training on clinical outcomes in patients with the metabolic syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2017, 16, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, A.S.; Maiya, A.G.; Shastry, B.A.; Vaishali, K.; Ravishankar, N.; Hazari, A.; Gundmi, S.; Jadhav, R. Exercise and insulin resistance in type 2 diabetes mellitus: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 2019, 62, 98–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Li, Q.; Liu, Y.; Jiang, H.; Chen, W. Intermittent fasting versus continuous energy-restricted diet for patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and metabolic syndrome for glycemic control: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2021, 179, 109003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yarizadeh, H.; Eftekhar, R.; Anjom-Shoae, J.; Speakman, J.R.; Djafarian, K. The effect of aerobic and resistance training and combined exercise modalities on subcutaneous abdominal fat: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Adv. Nutr. 2021, 12, 179–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, Japan. Necessary Expenses for Specific Health Checkups and Health Guidance. Available online: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/jigyo_shiwake/dl/r04_jigyou01a_day1.pdf (accessed on 28 July 2024).

- Fukuma, S.; Iizuka, T.; Ikenoue, T.; Tsugawa, Y. Association of the national health guidance intervention for obesity and cardiovascular risks with health outcomes among Japanese men. JAMA Intern. Med. 2020, 180, 1630–1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, Japan. Materials on Efficient and Effective Implementation Methods for Specific Health Checkups and Specific Health Guidance. Available online: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/content/12401000/000973955.pdf (accessed on 28 July 2024).

- Tsutatani, H.; Funamoto, M.; Sugiyama, D.; Kuwabara, K.; Miyamatsu, N.; Watanabe, K.; Okamura, T. Association between lifestyle factors assessed by standard question items of specific health checkup and the incidence of metabolic syndrome and hypertension in community dwellers: A five-year cohort study of national health insurance beneficiaries in Habikino City. Nihon Koshu Eisei Zasshi 2017, 64, 258–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haruyama, Y.; Nakagawa, A.; Kato, K.; Motoi, M.; Sairenchi, T.; Umesawa, M.; Uematsu, A.; Kudou, Y.; Kobashi, G. Incidence of metabolic syndrome in young Japanese adults in a 6-year cohort study: The Uguisudani preventive health large-scale cohort study (UPHLS). J. Epidemiol. 2020, 30, 219–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kinoshita, M.; Yokote, K.; Arai, H.; Iida, M.; Ishigaki, Y.; Ishibashi, S.; Umemoto, S.; Egusa, G.; Ohmura, H.; Okamura, T.; et al. Japan atherosclerosis society (JAS) guidelines for prevention of atherosclerotic cardiovascular diseases 2017. J. Atheroscler. Thromb. 2018, 25, 846–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, Japan. Diagnostic Criteria for Metabolic Syndrome. Available online: https://www.e-healthnet.mhlw.go.jp/information/metabolic/m-01-003.html (accessed on 28 July 2024).

- Pedersen, K.M.; Çolak, Y.; Ellervik, C.; Hasselbalch, H.C.; Bojesen, S.E.; Nordestgaard, B.G. Smoking and increased white and red blood cells. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2019, 39, 965–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Lorenzo, B.; Pau, M.C.; Zinellu, E.; Mangoni, A.A.; Paliogiannis, P.; Pirina, P.; Fois, A.G.; Carru, C.; Zinellu, A. Association between red blood cell distribution width and obstructive sleep apnea syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 3302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, Japan. Standard Health Checkups and Health Guidance Program 2024. Available online: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/content/001081458.pdf (accessed on 28 July 2024).

- Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, Japan. National Health and Nutrition Survey, Comprehensive Government Statistics Counter (e-Stat) of Japan. Available online: https://www.e-stat.go.jp/dbview?sid=0003223783 (accessed on 28 July 2024).

- Kikuchi, A.; Monma, T.; Ozawa, S.; Tsuchida, M.; Tsuda, M.; Takeda, F. Risk factors for multiple metabolic syndrome components in obese and non-obese Japanese individuals. Prev. Med. 2021, 153, 106855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kobo, O.; Leiba, R.; Avizohar, O.; Karban, A. Normal body mass index (BMI) can rule out metabolic syndrome: An Israeli cohort study. Medicine 2019, 98, e14712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, Japan. Changes in Nutrition and Health in Japan. Available online: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/nutrition_policy/global/pdfs/changes_in_nutrition_and_health_en.pdf (accessed on 28 July 2024).

- Khaing, I.K.; Tahara, Y.; Chimed-Ochir, O.; Shibata, S.; Kubo, T. Effect of breakfast protein intake on muscle mass and strength in adults: A scoping review. Nutr. Rev. 2025, 83, 175–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.K.; Chijiki, H.; Fukazawa, M.; Okubo, J.; Ozaki, M.; Nanba, T.; Higashi, S.; Shioyama, M.; Takahashi, M.; Nakaoka, T.; et al. Supplementation of protein at breakfast rather than at dinner and lunch is effective on skeletal muscle mass in older adults. Front. Nutr. 2021, 8, 797004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).