Introduction

Immunization remains a cornerstone of public health strategies aimed at reducing morbidity and mortality caused by vaccine-preventable diseases, particularly in children. Vaccines have proven to be highly effective in preventing serious illnesses such as measles, polio, and diphtheria, which historically led to high rates of illness and death among young populations. By providing immunity, immunization not only protects individuals from these diseases but also helps to protect communities by reducing the overall transmission through herd immunity. As a result, immunization plays a critical role in ensuring the well-being of children and promoting long-term public health [

1].

However, under-immunization continues to be a significant concern for public health authorities around the world. Many children, particularly in low-income or rural areas, do not receive the full range of vaccines required for optimal protection. Factors such as lack of access to healthcare, socio-economic barriers, misinformation about vaccines, and logistical challenges contribute to this issue. As long as gaps in immunization coverage persist, the risk of preventable diseases will remain, leading to unnecessary illness and deaths, as well as potential outbreaks that can strain healthcare systems. Addressing under-immunization is crucial to sustaining progress in the fight against vaccine-preventable diseases and safeguarding public health globally [

1,

2].

Vaccine-preventable diseases, such as measles, whooping cough, and tetanus, continue to present significant health risks, especially for children under the age of five. These diseases can cause severe complications, including pneumonia, brain damage, and even death, which are preventable through timely vaccination. The high vulnerability of young children makes them particularly at risk, as their immune systems are still developing and they have less resistance to infections. As a result, vaccination is essential in safeguarding children’s health and preventing outbreaks of these diseases, which can have devastating consequences for families and communities [

3].

The World Health Organization (WHO) highlights that around 20 million children worldwide are not fully vaccinated, with more than half of them living in Africa. This gap in vaccination coverage is a major concern for global public health, as it contributes to a rise in preventable illnesses and deaths among children. The lack of access to vaccines, misinformation, and logistical challenges are among the factors driving this issue. As a result, many children remain vulnerable to diseases that could otherwise be avoided, placing a heavy burden on healthcare systems and leading to unnecessary suffering. Addressing under-immunization is crucial to reducing child mortality and ensuring the health and well-being of future generations [

4,

5].

Africa faces a range of unique and complex challenges in achieving high vaccination coverage, making it difficult to ensure that all children are protected against vaccine-preventable diseases. Poverty remains one of the most significant barriers, as many families cannot afford healthcare services, and vaccination campaigns may not reach remote or underserved areas. Additionally, conflict and instability in several African countries disrupt healthcare infrastructure, making it difficult to maintain regular immunization programs and deliver vaccines to populations in need. Weak healthcare systems, characterized by shortages of trained healthcare workers and limited access to healthcare facilities, further hinder efforts to expand vaccination coverage. Cultural beliefs and misinformation about vaccines also contribute to resistance, as some communities may be wary of vaccination or prefer traditional healing practices over modern medical interventions [

6,

7,

8].

As a result of these challenges, vaccine-preventable diseases continue to be a leading cause of child mortality in Africa. In 2020, an estimated 572,000 children under the age of five died from diseases that could have been prevented through vaccination, highlighting the urgency of addressing under-immunization in the region [

9,

10].

The Expanded Program on Immunization (EPI) in Cameroon was established in 1976 to enhance vaccination coverage for children under five years of age. Over the years, the EPI has contributed significantly to increasing vaccination rates, achieving over 80% coverage in certain periods. However, despite these advancements, the program has faced challenges in maintaining and improving coverage levels. For instance, from 2013 to 2019, the coverage of the diphtheria-tetanus-pertussis (DTP-3) vaccine dropped from 89% to 67%, leaving many children without essential vaccinations [

11,

12,

13]. The EPI provides free vaccines against at least 14 preventable diseases, and it has been integrated into the national health system to ensure broader access. Despite the progress made, access to vaccination services remains limited in some regions, and ongoing efforts are necessary to address gaps in immunization coverage and to reach zero-dose children [

12,

13].

Cameroon has made significant progress in improving vaccination coverage in recent years, but under-immunization remains a challenge, particularly in urban areas. According to the Cameroon Demographic and Health Survey (CDHS) 2018, only 68% of children aged 12-23 months were fully vaccinated [

14]. Urban areas tend to have lower vaccination coverage rates than rural areas. For example, in the Southwest Region where Buea is located, the full vaccination coverage rate among children aged 12-23 months was 63% in urban areas compared to 70% in rural areas [

14]. This study aimed at determining the prevalence and determinants of under-immunization among children aged 0-59 months in the urban settings of Buea in Cameroon. Findings from this and similar studies could contribute to improved strategies for a more effective vaccine uptake especially among the vulnerable groups.

Methods

Study Design and Setting

This was a cross-sectional study to capture data on the prevalence and determinants of under-immunization. It was focused on the urban settings of Buea which include; Buea Road, Molyko, Bokwango, and Buea Town comprising 22 communities. Buea, as a major urban city which is diverse and densely populated with unique healthcare challenges and opportunities. Its urban landscape encompasses a mix of residential, commercial, and healthcare infrastructure, providing a dynamic backdrop for understanding childhood immunization in an urban context.

Data Collection and Sampling

The study focused on caregivers of children aged 0-59 months in urban Buea, a critical age for immunization. Using Cochran’s formula, the sample size was calculated to be 385, but data was collected from 438 participants.

A multistage sampling technique was used for the selection of study cohort; Purposive sampling to select Urban Health Areas in Buea, Probability proportionate to size to select participants per health area, Simple random sampling to choose 22 communities, Cluster sampling to create clusters within communities, Simple random sampling to select households from each cluster.

Primary caregivers of eligible children (0 – 59 months) who consented were included in the study. Those who were extremely sick were excluded from the study. Structured questionnaires were used to collect data on socio-demographics, immunization factors, and health system variables.

Data Management and Analysis

The structured questionnaire based on the World Health Organization Behavioural and Social Determinants (WHO BeSD) of vaccination tool. It is preferred because it provides a well-rounded, evidence-based, and context-sensitive framework for understanding and addressing the behavioral and social factors influencing vaccination decisions. The questionnaire was pretested and adjusted for clarity and relevance. Data were collected electronically via Google Forms and entered by trained personnel. Analysis was performed using SPSS version 26, with descriptive statistics summarizing the study population and vaccination coverage. Prevalence of under-immunization and zero dose were calculated, and chi-square tests and logistic regression identified significant predictors, with a p-value < 0.05 considered significant.

Ethical Considerations

Ethical clearance was obtained from the IRB at the Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Buea, ref no: ref: 2024/2359-01/UB/SG/IRB/FHS of 14 February 2024. The objectives of the study were explained to the caregivers of eligible children and signed consent form obtained before the questionnaire was administered.

Results

Socio-Demographic Characteristics of Study Participants

Most of the participants (41.3%) were from Buea Road. Caregivers had a mean age of 31 years, mostly women (87.7%), aged 22-30 years (56.2%). Children’s ages were mainly 25-36 months (29.9%) and 0-12 months (28.8%). Most caregivers were married (49.5%), university-educated (53.7%), self-employed (56.2%), and had one child (56.8%). Monthly income was below 50,000 FCFA by 42.9%. The study population was predominantly Christian (94.3%) and leaseholders (74.2%).

Table 1 shows the sociodemographic characteristics of participants.

Attitudes and Vaccination Practices of Study Participants

This present study found that 74.4% of children received all recommended vaccines, with 80.6% of caregivers providing vaccination cards. Most children (78.3%) had not contracted vaccine-preventable diseases. However, only 59.4% of caregivers discussed vaccination concerns with healthcare workers. Family influence was significant for 53.2% of caregivers, while 28.3% faced societal stigma for not vaccinating. Additionally, 66.7% had never received unsolicited vaccination advice, and 78.8% did not hold positive cultural beliefs about vaccines.

Table 2 shows the distribution of attitudes and vaccination practices among study participants in the Buea municipality.

Prevalence of Under-Immunization

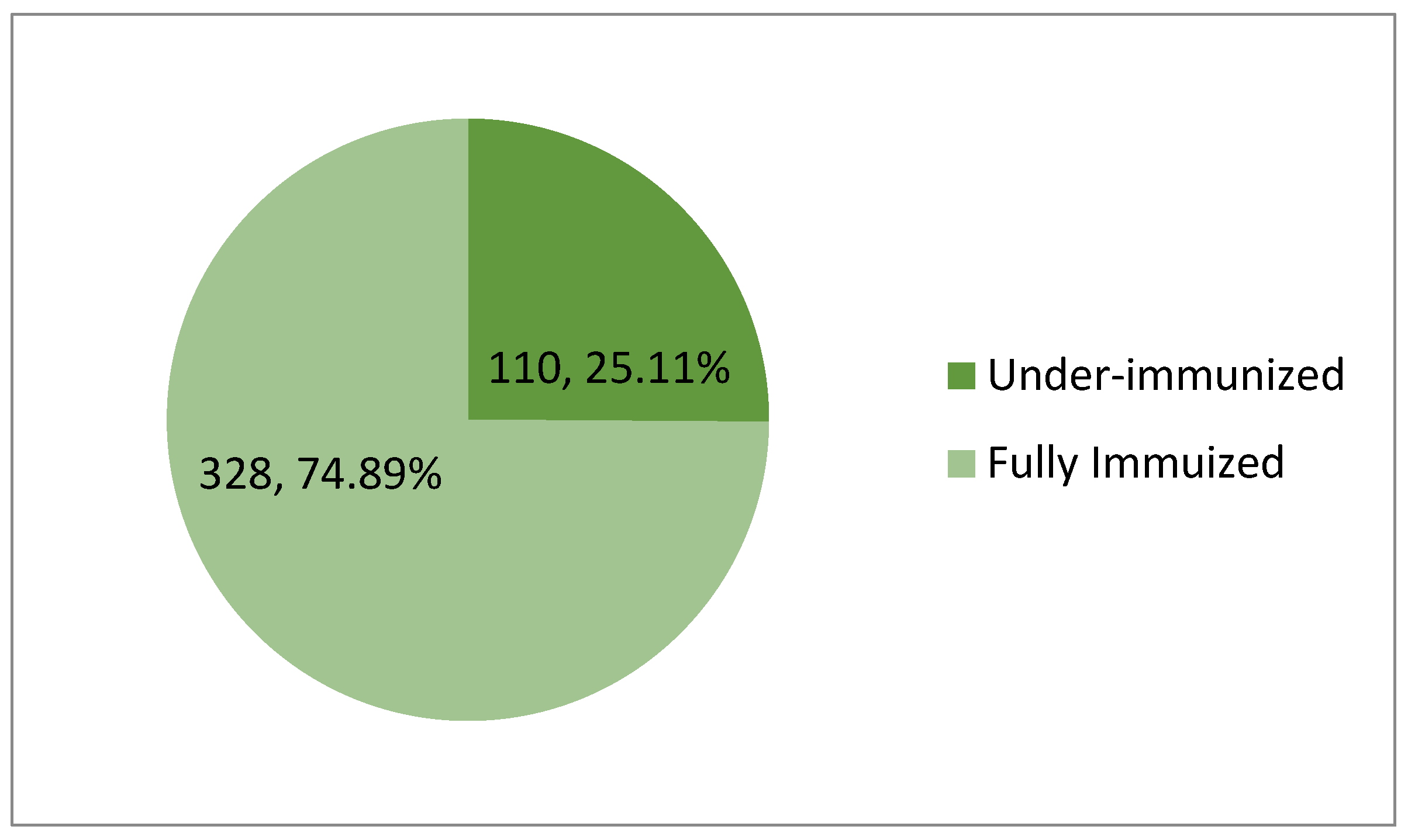

The proportion of participants who have received some but not all vaccine doses was calculated by (Number of under-immunized participants / Total number of participants) x 100%; (110 / 438) x 100% = 25.11%

Therefore, the prevalence of under-immunization in this study was 25.11%.

Figure 1.

Prevalence of under-immunization.

Figure 1.

Prevalence of under-immunization.

Behavioural and Health System Factors and Their Distribution among Caregivers of Children

The present study found that 292 (66.7%) of caregivers rarely discussed vaccines with healthcare providers, though 77 (17.6%) had positive cultural practices regarding vaccination. About 173 (39.5%) lived within 1 mile of a health facility, but 229 (52.3%) experienced vaccine stockouts. Waiting times were moderate for 219 (50%), and 291 (66.4%) received vaccination reminders. Most of the participants; 291 (66.4%) did not perceive changes in vaccine quality, suggesting it may not significantly impact vaccination decisions.

Table 3 shows the behavioural and health system characteristics of caregivers surveyed in the present study.

Association between Social Factors and Under-Immunization

Bivariate analysis showed that caregivers who didn’t receive unsolicited advice from peers were 1.7 times more likely to have under-immunized children (cOR = 1.7, 95% CI: 1.1 - 2.6, p = 0.025) than those did. Also, the children of caregivers without positive cultural beliefs about vaccines were 1.9 times more likely to be under-immunized (cOR = 1.9, 95% CI: 1.2 - 3.0, p = 0.014) than their counterparts (

Table 4).

Association of Accessibility, Acceptance, and Utilization of Vaccination Services and Under-immunization

Table 5 shows caregivers without supportive cultural practices were 1.9 times more likely to have under-immunized children (cOR = 1.9, 95% CI: 1.1 - 3.2, p = 0.018) than those with supportive cultural practices. Those who lived further away were more likely to have under-immunized children than those living nearby. Caregivers living less than 1 mile from health facilities were 3.3 times less likely to have under-immunized children (cOR = 3.3, 95% CI: 1.4 - 7.6, p = 0.005) than those living more than 10 miles away. Those who didn’t perceive improvements in vaccine quality were 1.7 times more likely to have under-immunized children (cOR = 1.7, 95% CI: 1.1 - 2.7, p = 0.016) than caregivers who perceived improvement in the quality of vaccines and services (

Table 5).

Table 5 below shows the factors that are associated with immunization coverage.

Association between Socio-Demographic Factors and Under-Immunization

Multivariable analysis found that participants who lived in Buea Town were 2.6 times more likely to be under-immunized than those in Molyko (adjusted odds ratio (aOR) = 2.6, 95% CI: 1.2 - 5.7, p = 0.016). Those with one child were 1.7 times more likely to have under-immunized children than those with two or more children (aOR = 1.7, 95% CI: 1.0 - 2.7, p = 0.041). Children of caregivers who were educated up to the primary level, were 2.1 times more likely to be under-immunized than those of caregivers who university education (

Table 6). Caregivers not living in rented or owned houses were 0.3 times less likely to have under-immunized children than those in rented houses (aOR = 0.4, 95% CI: 0.1 - 0.7, p = 0.005).

Socio-Cultural and Healthcare Accessibility Factors That Are Associated with Under-Immunization

Table 7 shows the multivariable analysis which found that children in Buea Town were 3 times more likely to be under-immunized than those in Molyko (aOR = 3.0, 95% CI: 1.3 - 7.3, p = 0.013). While children of separated caregivers were 0.2 times less likely to be under-immunized than those of widowed caregivers (aOR = 0.2, 95% CI: 0.1 - 0.9, p = 0.036). It was observed that children of private sector-employed caregivers were 4.3 times more likely to be under-immunized than those of unemployed caregivers (aOR = 4.3, 95% CI: 1.1 - 16.2, p = 0.031). Children in non-owned/non-rented houses were 0.3 times less likely to be under-immunized than those in rented houses (aOR = 0.3, 95% CI: 0.1 - 0.9, p = 0.030). Children whose caregivers didn’t receive unsolicited advice were 2.1 times more likely to be under-immunized (aOR = 2.1, 95% CI: 1.2 - 3.4, p = 0.006). It was also observed that children living less than 1 mile from health facilities were 2.9 times more likely to be under-immunized than those living more than 10 miles away (aOR = 2.9, 95% CI: 1.1 - 7.5, p = 0.030). Children whose caregivers didn’t perceive improvements in vaccine services were 1.9 times more likely to be under-immunized (aOR = 1.9, 95% CI: 1.1 - 3.2, p = 0.021) than who perceived improvements in vaccine services (

Table 7).

Discussion

The prevalence of under-immunization among children aged 0-59 months in the present study was found to be 25.11%. This figure contrasts with findings from a study conducted in the Foumban Health District of Cameroon, which reported a significantly higher vaccination coverage of 80% for the DPT-HiB+HB (diphtheria, pertussis, tetanus, Haemophilus influenzae type b, and hepatitis B) vaccine among children aged 0-59 months in Foumban [

15] suggests that under-immunization may vary geographically, with certain regions exhibiting better immunization coverage than others. Furthermore, a separate study focused on hepatitis B vaccination uptake among healthcare workers in Cameroon revealed a vaccination rate of 27.4% [

16]. This is lower than the 25.11% under-immunization rate identified among children in the current study. This comparison suggests that the prevalence of under-immunization is somewhat lower among children aged 0-59 months than it is among healthcare workers in Cameroon, indicating that healthcare workers may face unique barriers to vaccination, such as occupational risk factors, vaccine availability, or awareness issues, that differ from those affecting children. These findings highlight the importance of considering both demographic and geographical factors when assessing vaccination coverage and under-immunization rates, as well as the potential disparities between different population groups, including children and healthcare workers. Addressing these disparities will be crucial in achieving universal immunization coverage and reducing preventable diseases in both child and adult populations.

Children in Buea Town were found to be three times more likely to be under-immunized compared to those in Molyko (AOR = 3.0, 95% CI: 1.3 - 7.3, p = 0.013). This result is consistent with findings from various studies, which have highlighted that immunization rates can vary significantly within urban areas, often due to differences in healthcare access, socio-economic conditions, and levels of community engagement. For example, a study conducted in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, demonstrated that urban areas with poorer infrastructure and lower socio-economic status had significantly lower vaccination coverage rates compared to wealthier neighborhoods [

17]. Similarly, studies in India have shown that while urban areas may generally have greater access to healthcare services, factors like slum dwelling, low income, and educational barriers often result in lower immunization rates in specific urban pockets [

18]. These findings suggest that specific barriers in Buea Town, such as limited healthcare access, socio-economic disparities, and lower levels of community engagement, may contribute to the higher likelihood of under-immunization observed in this study. In urban centers, healthcare infrastructure can be uneven, with certain areas, especially informal settlements or economically disadvantaged neighborhoods, facing difficulties in accessing quality healthcare services [

19]. Socio-economic conditions also play a significant role, as families with lower incomes or lower levels of education may face greater challenges in accessing vaccines or may not be fully aware of the importance of immunization [

20]. Furthermore, gaps in community engagement and health promotion efforts can also lead to vaccine hesitancy or a lack of information about vaccination services, particularly in urban areas with diverse populations and high rates of migration [

21]. Addressing these barriers requires targeted interventions that focus on improving healthcare access, strengthening community-based health initiatives, and addressing socio-economic inequalities. Moreover, increasing outreach efforts to engage underserved populations in Buea Town, ensuring equitable distribution of healthcare resources, and enhancing public health education campaigns could help reduce the under-immunization rate observed in this study. By addressing these underlying factors, public health authorities can work towards achieving higher immunization coverage and improving health outcomes for children in both Buea Town and other urban areas facing similar challenges.

The finding that children in Buea Town are three times more likely to be under-immunized compared to those in Molyko is in line with studies showing urban areas can exhibit varied immunization rates due to multiple factors such as healthcare infrastructure, socio-economic conditions, and cultural practices. For instance, a study in sub-Saharan Africa highlighted that urban areas, while often having more healthcare facilities, may experience disparities in immunization uptake due to overcrowding, inefficiency in service delivery, or issues related to migrant populations who may be less informed about available services areas might have lower access to healthcare facilities but tighter-knit communities that foster more consistent vaccination behaviors [

22]. Addressing barriers in Buea Town, such as improving service delivery, ensuring equitable access to healthcare, and strengthening community engagement, could be key to addressing these disparities.

The observation that children of caregivers who were separated from their spouse are less likely to be under-immunized compared to those with widowed caregivers contradicts the expected trend that single-parent households, particularly those headed by widows, are more likely to face barriers to healthcare. This could reflect differences in the support systems available to separated versus widowed caregivers. Research has shown that widowed caregivers may face heightened socio-economic vulnerabilities, which could limit their ability to prioritize and access healthcare for their children [

23]. In contrast, separated caregivers might benefit from broader family or social support networks that help ensure immunization adherence, even if they are single. However, further investigation into the dynamics of single-parent households in this context is warranted to fully understand the observed trend [

24].

Children of caregivers employed in the private sector are more likely to be under-immunized than the children of unemployed caregivers which supports the general expectations that employment increases access to healthcare. Several studies have found that employed caregivers, especially those in the public sector, often have better healthcare access due to benefits like paid leave, healthcare insurance, and better economic stability [

25]. However, the demanding nature of private sector jobs could create time constraints for caregivers, limiting their ability to take their children for vaccinations. This underscores the importance of considering both the economic benefits of employment and the time-related challenges posed by different work sectors when addressing immunization barriers.

The caregivers not living in their own house or rented property had children were less likely to be immunized compared to those leaving in rented houses. This presents a unique finding suggesting that housing stability may play a role in ensuring regular healthcare visits and adherence to vaccination schedules. This contrasts with the idea that renters or homeowners are more likely to have stable living conditions conducive to healthcare access. One possible explanation could be that families in non-rented housing such as those staying with relatives or in temporary housing, might benefit from more flexible or informal support networks that could aid in regular healthcare visits. Alternatively, this finding may reflect socio-economic factors tied to housing types that influence health-seeking behavior [

26].

It was more likely to see under-immunized children with caregivers who did not receive unsolicited advice compared to their counterpart. This aligns with research emphasizing the significant role of social networks in health behaviors. Studies have shown that peer influence and community engagement can strongly affect health decisions, including immunization adherence [

27]. Caregivers who are not exposed to informal he key information about immunization schedules, the importance of vaccines, or how to access healthcare services. This highlights the value of public health initiatives that leverage community-based outreach and peer support to improve vaccination rates.

The children living less than 1 mile from health facilities were more likely to be under-immunized and this contradicts the general assumption that proximity to healthcare services improves vaccination rates. In theory, closer proximity should make it easier for caregivers to access services. However, this result suggests that proximity alone is insufficient to explain immunization uptake. Other factors, such as the quality of healthcare services, healthcare worker attitudes, financial barriers, and perceived healthcare system trust, may play a more significant role. Studies have shown that even when healthcare services are geographically accessible, they may not be utilized if there are issues with service delivery, such as long wait times or negative experiences with healthcare workers [

28].

Caregivers did not perceive improvements in vaccine services were more likely to have under-immunized children compared to those who did. This is consistent with literature highlighting the importance of trust in healthcare services for improving vaccination compliance [

29]. Caregivers who believe that healthcare services have not improved may be less motivated to seek immunizations for their children, as they may perceive these services as inadequate or unreliable . Perceived quality of healthcare plays a critical role in health-seeking behaviours and improving this perception could lead to better immunization outcomes [

29].

Conclusion

These findings offer crucial insights into the multifaceted barriers to immunization in the municipality of Buea, highlighting the need to address socio-economic disparities, healthcare access challenges, and the role of social networks in shaping health behaviors. Tailored interventions must not only focus on proximity to healthcare facilities but also improve service quality, engage communities, and consider the distinct challenges faced by different caregiver groups.

However, the study’s limitations, including recall bias and its cross-sectional nature, suggest that further research is needed to deepen our understanding of vaccine uptake trends. Conducting qualitative studies will be essential to uncover the underlying reasons for under-vaccination, particularly in missed or marginalized communities. Given the specific context of this study in Cameroon, broader research is needed to determine whether these findings are applicable nationwide, especially in light of the impacts of civil conflict and the COVID-19 pandemic. These insights can guide the development of more effective, targeted vaccination strategies to enhance public health outcomes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.N.D.; methodology, F.N.N., N.T., G.E.M., H.Q., S.E.M., S.D.G., R.M., V.P.K.T.; data analysis, F.N.N., S.D.G., G.E.M., H.Q., S.E.M., I.A.; original draft preparation, J.N.D., N.T., G.E.M., S.D.G., I.A., S.E.M., R.M..; writing–review and editing, J.N.D., N.T., R.M., V.P.K.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in compliance with the Helsinki Declaration and all applicable national laws and institutional rules and has been approved by the author’s institutional review board. Ethical approval was granted by the institutional review board, Faculty of health sciences, University of Buea; ref no: 2359-01 of 14 February, 2024.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data used for this research are available from the Corresponding author upon request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

Our gratitude to the Michael Gahnyam Gbeugvat Foundation, Cameroon. Also, we would like to acknowledge the staff of the Faculty of Health Sciences, University Of Buea, Cameroon. The APC was covered by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation under grant no.: the OPP1075938-PEARL Program Support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Zhou F, Jatlaoui TC, Leidner AJ, Carter RJ, Dong X, Santoli JM, et al. Health and Economic Benefits of Routine Childhood Immunizations in the Era of the Vaccines for Children Program — United States, 1994–2023. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2024; 73(31):682–685. [CrossRef]

- Talbird SE, Carrico J, La EM, Carias C, Marshall GS, Roberts CS, et al. Impact of Routine Childhood Immunization in Reducing Vaccine-Preventable Diseases in the United States. Pediatrics. 2022; 150(3):e2021056013. [CrossRef]

- US Drug & Food Administration. Vaccines for Children - A Guide for Parents and Caregivers. 2024. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/vaccines-blood-biologics/consumers-biologics/vaccines-children-guide-parents-and-caregivers. Accessed on 31 December 2024.

- World Health Organization. Immunization coverage. 2023. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/immunization-coverage. Accessed on 19 November 2023.

- Kaur G, Danovaro-Holliday MC, Mwinnyaa G, Gacic-Dobo M, Francis L, Grevendonk J, et al. Routine Vaccination Coverage — Worldwide, 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2023; 72(43):1155–1161.

- Biks GA, Shiferie F, Tsegaye DA, Asefa W, Alemayehu L, Wondie T, et al. In-depth reasons for the high proportion of zero-dose children in underserved populations of Ethiopia: Results from a qualitative study. Vaccine X. 2024; 16:100454. [CrossRef]

- Mbonigaba E, Nderu D, Chen S, Denkinger C, Geldsetzer P, McMahon S, et al. Childhood vaccine uptake in Africa: threats, challenges, and opportunities. J Glob Health Rep. 2021. Available online: https://www.joghr.org/article/26312-childhood-vaccine-uptake-in-africa-threats-challenges-and-opportunities. Accessed om 31 December 2024.

- Bangura JB, Xiao S, Qiu D, Ouyang F, Chen L. Barriers to childhood immunization in sub-Saharan Africa: A systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2020; 20(1):1108. [CrossRef]

- Frenkel LD. The global burden of vaccine-preventable infectious diseases in children less than 5 years of age: Implications for COVID-19 vaccination. How can we do better? Allergy Asthma Proc. 2021; 42(5):378–85. [CrossRef]

- WHO African Region. Vaccine-preventable disease outbreaks on the rise in Africa. 2022. Available online: https://www.afro.who.int/news/vaccine-preventable-disease-outbreaks-rise-africa. Accessed on 31 December 2024.

- Ebile Akoh W, Ateudjieu J, Nouetchognou JS, Yakum MN, Djouma Nembot F, Nafack Sonkeng S, et al. The expanded program on immunization service delivery in the Dschang health district, west region of Cameroon: a cross sectional survey. BMC Public Health. 2016; 16(1):801. [CrossRef]

- Saidu Y, Gu J, Ngenge BM, Nchinjoh SC, Adidja A, Nnang NE, et al. The faces behind vaccination: unpacking the attitudes, knowledge, and practices of staff of Cameroon’s Expanded program on Immunization. Hum Resour Health. 2023; 21:88. [CrossRef]

- GAVI, The Vaccine Alliance. Half a century of EPI in Cameroon: Dr Tchokfe Shalom Ndoula takes stock. 2024. Available online: https://www.gavi.org/vaccineswork/Half-century-EPI-Cameroon-Dr-Tchokfe-Shalom-Ndoula. Accessed on 31 Dember 2024.

- Camerron Demographic and Health Surveys Program. Cameroon: DHS, 2018 - Cameroon 2018 Demographic and Health Survey - Summary Report. 2018. Available online: https://dhsprogram.com/publications/publication-sr266-summary-reports-key-findings.cfm. Accessed on 31 December 2024.

- Ateudjieu J, Tchio-Nighie KH, Goura AP, Ndinakie MY, Dieffi Tchifou M, Amada L, et al. Tracking Demographic Movements and Immunization Status to Improve Children’s Access to Immunization: Field-Based Randomized Controlled Trial. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2022; 8(3):e32213. [CrossRef]

- Ngekeng S, Chichom-Mefire A, Tendongfor N, Malika E, Ebob-Bessem M, Choukem SP. Impact of Behaviour Change Communication on Uptake of Hepatitis B Vaccination among Health Workers in Fako Division, Cameroon. OALib. 2024; 11(01):1–15. [CrossRef]

- Mekonnen W, Dechassa W, Melesse DY, Tejedor-Garavito N, Nilsen K, Getachew T, et al. Inter-district and Wealth-related Inequalities in Maternal and Child Health Service Coverage and Child Mortality within Addis Ababa City. J Urban Health. 2024; 101(S1):68–80. [CrossRef]

- Shrivastava R, Singhal M, Joshi A, Mishra N, Agrawal A, Kumar B. Barriers and opportunities in utilizing maternal healthcare services during antenatal period in urban slum settings in India: A systematic review. Clin Epidemiol Glob Health. 2023; 20:101233. [CrossRef]

- Zimba B, Mpinganjira S, Msosa T, Bickton FM. The urban-poor vaccination: Challenges and strategies in low-and-middle income countries. Hum Vaccines Immunother. 2024; 20(1):2295977. [CrossRef]

- Sacre A, Bambra C, Wildman JM, Thomson K, Bennett N, Sowden S, et al. Socioeconomic inequalities in vaccine uptake: A global umbrella review. Brunelli L, editor. PLOS ONE. 2023; 18(12):e0294688. [CrossRef]

- Wong J, Lao C, Dino G, Donyaei R, Lui R, Huynh J. Vaccine Hesitancy among Immigrants: A Narrative Review of Challenges, Opportunities, and Lessons Learned. Vaccines. 2024; 12(5):445. [CrossRef]

- Asmare G, Madalicho M, Sorsa A. Disparities in full immunization coverage among urban and rural children aged 12-23 months in southwest Ethiopia: A comparative cross-sectional study. Hum Vaccines Immunother. 2022; 18(6):2101316. [CrossRef]

- Gumikiriza-Onoria JL, Nakigudde J, Mayega RW, Giordani B, Sajatovic M, Mukasa MK, et al. Psychological distress among family caregivers of persons with Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias in Uganda. BMC Geriatr. 2024; 24(1):602. [CrossRef]

- Cooper S, Schmidt BM, Sambala EZ, Swartz A, Colvin CJ, Leon N, et al. Factors that influence parents’ and informal caregivers’ views and practices regarding routine childhood vaccination: a qualitative evidence synthesis. Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care Group, editor. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2021; 2021(10). [CrossRef]

- Henning-Smith C, Dill J, Baldomero A, Backes Kozhimannil K. Rural/urban differences in access to paid sick leave among full-time workers. J Rural Health. 2023; 39(3):676–85. [CrossRef]

- Keene DE, Schlesinger P, Carter S, Kapetanovic A, Rosenberg A, Blankenship KM. Filling the Gaps in an Inadequate Housing Safety Net: The Experiences of Informal Housing Providers and Implications for Their Housing Security, Health, and Well-Being. Socius Sociol Res Dyn World. 2022; 8:23780231221115283. [CrossRef]

- Li L, Wood CE, Kostkova P. Vaccine hesitancy and behavior change theory-based social media interventions: a systematic review. Transl Behav Med. 2022; 12(2):243–72. [CrossRef]

- Balgovind P, Mohammadnezhad M. Factors affecting childhood immunization: Thematic analysis of parents and healthcare workers’ perceptions. Hum Vaccines Immunother. 2022; 18(6):2137338. [CrossRef]

- Ames HM, Glenton C, Lewin S. Parents’ and informal caregivers’ views and experiences of communication about routine childhood vaccination: a synthesis of qualitative evidence. Cochrane Consumers and Communication Group, editor. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017; 2017(4). [CrossRef]

Table 1.

Socio-Demographic Characteristics of Study Population.

Table 1.

Socio-Demographic Characteristics of Study Population.

| Variable |

Category |

Frequency (Percentage) |

| |

Bokwango |

61 (13.9%) |

| |

Buea Road |

181 (41.3%) |

| |

Buea Town |

66 (15.1%) |

| |

Molyko |

130 (29.7%) |

| |

Total |

438 (100%) |

| Community |

|

|

| |

Bokwai Layout |

19 (4.3%) |

| |

Bokwango |

14 (3.2%) |

| |

Bonalyonga |

12 (2.7%) |

| |

Buea Station |

29 (6.6%) |

| |

Campsic |

11 (2.5%) |

| |

Check Point |

32 (7.3%) |

| |

GRA |

12 (2.7%) |

| |

Great Soppo |

35 (8.0%) |

| |

Likoko |

12 (2.7%) |

| |

Long Street |

15 (3.4%) |

| |

Lower Bonduma |

51 (11.6%) |

| |

Malingo |

30 (6.8%) |

| |

Mukunda |

11 (2.5%) |

| |

Naanga |

12 (2.7%) |

| |

Ndongo |

21 (4.8%) |

| |

Sandpit |

10 (2.3%) |

| |

Stranger East |

9 (2.1%) |

| |

Stranger west |

1 (0.2%) |

| |

Stranger West |

18 (4.1%) |

| |

UB 1 and 2 |

28 (6.4%) |

| |

Upper Bonduma |

41 (9.4%) |

| |

Wondongo |

15 (3.4%) |

| |

Total |

438 (100%) |

| Ages of Caregivers ( years) |

|

|

| |

22-30 |

246 (56.2%) |

| |

31-40 |

137 (31.3%) |

| |

41-50 |

47 (10.7%) |

| |

51-60 |

8 (1.8%) |

| |

Total |

438 (100%) |

| Ages of Children (months) |

|

|

| |

0-12 |

126 (28.8%) |

| |

13-24 |

90 (20.5%) |

| |

25-36 |

131 (29.9%) |

| |

37-48 |

48 (11.0%) |

| |

51-59 |

43 (9.8%) |

| |

Total |

438 (100%) |

| Sex of caregiver |

|

|

| |

Female |

384 (87.7%) |

| |

Male |

54 (12.3%) |

| |

Total |

438 (100%) |

| Marital Status |

|

|

| |

Divorced |

11 (2.5%) |

| |

Married |

217 (49.5%) |

| |

Separated |

21 (4.8%) |

| |

Single |

172 (39.3%) |

| |

Widowed |

17 (3.9%) |

| |

Total |

438 (100%) |

| Level of Education |

|

|

| |

No Formal Education |

12 (2.7%) |

| |

Primary |

29 (6.6%) |

| |

Secondary |

162 (37.0%) |

| |

University |

235 (53.7%) |

| |

Total |

438 (100%) |

| Occupation |

|

|

| |

Employed (Government) |

54 (12.3%) |

| |

Employed (Private Sector) |

25 (5.7%) |

| |

Self-employed (Business) |

246 (56.2%) |

| |

Unemployed |

113 (25.8) |

| |

Total |

438 (100%) |

| Number of Children |

|

|

| |

More than Two |

74 (16.9%) |

| |

One |

249 (56.8) |

| |

Two |

115 (26.3%) |

| |

Total |

438 (100%) |

| Monthly Income |

|

|

| |

Less than 50K |

188 (42.9) |

| |

50K-99K |

145 (33.1%) |

| |

100K-150K |

69 (15.8%) |

| |

Above 150K |

36 (8.2%) |

| |

Total |

438 (100%) |

| Religion |

|

|

| |

Christian |

413 (94.3%) |

| |

Muslim |

11 (2.5%) |

| |

Others |

14 (3.2%) |

| |

Total |

438 (100%) |

| Caregiver Status |

|

|

| |

Primary caregiver |

250 (57.1%) |

| |

Secondary caregiver |

54 (12.3%) |

| |

Shared responsibility |

134 (30.6) |

| |

Total |

438 (100%) |

| Housing Situation |

|

|

| |

Rented |

325 (74.2%) |

| |

Owned |

86 (19.6%) |

| |

Other |

27 (6.2%) |

| |

Total |

438 (100%) |

Table 2.

Distribution of attitudes and vaccination practices among study participants.

Table 2.

Distribution of attitudes and vaccination practices among study participants.

| Variable |

Category |

Frequency (Percentage) |

| Child Vaccination |

|

|

| |

Have not received a single dose |

2 (0.5%) |

| |

No, received some. |

110 (25.1%) |

| |

Yes, received all. |

326 (74.4%) |

| |

Total |

438 (100%) |

| Presence of Vaccination Card |

|

|

| |

No |

85 (19.4%) |

| |

Yes |

353 (80.6%) |

| |

Total |

438 (100%) |

| Child Experienced Vaccine-preventable Disease VPDs |

|

|

| |

No |

343 (78.3%) |

| |

Yes |

95 (21.7%) |

| |

Total |

438 (100%) |

| Discussed Vaccination Concerns with Healthcare workers |

|

|

| |

No |

178 (40.6%) |

| |

Yes |

260 (59.4%) |

| |

Total |

438 (100%) |

| Influence of Family |

|

|

| |

No |

209 (47.7%) |

| |

Yes |

229 (47.7%) |

| |

Total |

438 (100%) |

| Societal Stigma |

|

|

| |

No |

314 (71.7%) |

| |

Yes |

124 (28.3%) |

| |

Total |

438 (100%) |

| Received Advice |

|

|

| |

No |

292 (66.7%) |

| |

Yes |

146 (33.3%) |

| |

Total |

438 (100%) |

| Good Cultural Beliefs |

|

|

| |

No |

345 (78.8%) |

| |

Yes |

93 (21.2%) |

| |

Total |

438 (100%) |

Table 3.

Distribution of Behavioural and Use of Health System Characteristics Amongst the Caregivers.

Table 3.

Distribution of Behavioural and Use of Health System Characteristics Amongst the Caregivers.

| Variable |

Category |

Frequency (Percentage) |

| Frequency of Vaccine Discussions |

|

|

| |

Frequently |

146 (33.3%) |

| |

Rarely |

292 (66.7%) |

| |

Total |

438 (100%) |

| Cultural Practices |

|

|

| |

No |

361 (82.4%) |

| |

Yes |

77 (17.6%) |

| |

Total |

438 (100%) |

| Proximity to Health Facility |

|

|

| |

1-5 miles |

159 (36.3%) |

| |

5-10 miles |

78 (17.8%) |

| |

Less than 1 mile |

173 (39.5%) |

| |

More than 10 miles |

28 (6.4%) |

| |

Total |

438 (100%) |

| Experienced Vaccine Stock outs |

|

|

| |

No |

229 (52.3%) |

| |

Yes |

209 (74.7%) |

| |

Total |

438 (100%) |

| Waiting Time |

|

|

| |

Long |

116 (26.5%) |

| |

Moderate |

219 (50%) |

| |

Short |

103 (23.5%) |

| |

Total |

438 (100%) |

| Reminders or Notifications |

|

|

| |

No |

147 (33.6%) |

| |

Yes |

291 (66.4%) |

| |

Total |

438 (100%) |

| Perceived Change in Quality of Vaccine and Services |

|

|

| |

No |

291 (66.4%) |

| |

Yes |

147 (33.6%) |

| |

Total |

438 (100%) |

Table 4.

Association Between Social Factors and Under-immunization in the Study Participants of the Buea Municipality.

Table 4.

Association Between Social Factors and Under-immunization in the Study Participants of the Buea Municipality.

| |

|

|

95% CI |

| |

|

No |

Yes |

Total |

cOR |

Lower |

Upper |

p-Value |

| Child Experienced Vaccine Preventable Disease (VPDs) |

No |

262 |

81 |

343 |

1.567 |

0.954 |

2.573 |

0.076 |

| |

Yes |

64 |

31 |

95 |

1 |

|

|

|

Discussed Vaccination

Concerns With Healthcare

workers |

No |

122 |

56 |

178 |

0.598 |

0.388 |

0.922 |

0.020 |

| |

Yes |

204 |

56 |

260 |

1 |

|

|

|

| Influence of Family |

No |

151 |

58 |

209 |

0.803 |

0.523 |

1.235 |

0.318 |

| |

Yes |

296 |

90 |

386 |

1 |

|

|

|

| Societal Stigma |

No |

240 |

74 |

314 |

1.433 |

0.903 |

2.275 |

0.127 |

| |

Yes |

86 |

38 |

124 |

1 |

|

|

|

| Received Unsolicited Advice |

No |

227 |

65 |

292 |

1.658 |

1.064 |

2.583 |

0.025 |

| |

Yes |

99 |

47 |

146 |

1 |

|

|

|

| Cultural Beliefs |

No |

266 |

79 |

345 |

1.852 |

1.131 |

3.033 |

0.014 |

| |

Yes |

60 |

33 |

93 |

1 |

|

|

|

Table 5.

Accessibility, Acceptance, and Utilization of Vaccination Services Factors Associated with Under-immunization.

Table 5.

Accessibility, Acceptance, and Utilization of Vaccination Services Factors Associated with Under-immunization.

| |

|

|

95% CI |

| |

|

No |

Yes |

Total |

cOR |

Lower |

Upper |

p-Value |

Frequency of Vaccine

Discussions |

Frequently |

116 |

30 |

146 |

1.510 |

0.938 |

2.430 |

0.090 |

| |

Rarely |

210 |

82 |

292 |

1 |

|

|

|

| Cultural Practices |

No |

277 |

84 |

361 |

1.884 |

1.115 |

3.184 |

0.018 |

| |

Yes |

49 |

28 |

77 |

1 |

|

|

|

| Proximity to Health Facility |

1-5 miles |

117 |

42 |

159 |

2.414 |

1.061 |

5.493 |

0.036 |

| |

5-10 miles |

57 |

21 |

78 |

2.352 |

0.961 |

5.760 |

0.061 |

| |

Less than 1 mile |

137 |

36 |

173 |

3.298 |

1.440 |

7.552 |

0.005 |

| |

More than 10 miles |

15 |

13 |

28 |

1 |

|

|

|

| Experienced Vaccine Stockouts |

No |

167 |

62 |

229 |

0.847 |

0.550 |

1.304 |

0.450 |

| |

Yes |

159 |

50 |

209 |

1 |

|

|

|

| Waiting Time |

Long |

82 |

34 |

116 |

0.900 |

0.499 |

1.624 |

0.727 |

| |

Moderate |

169 |

50 |

219 |

1.262 |

0.738 |

2.158 |

0.396 |

| |

Short |

75 |

28 |

103 |

1 |

|

|

|

| Reminders or Notifications |

No |

106 |

41 |

147 |

0.834 |

0.533 |

1.307 |

0.429 |

| |

Yes |

220 |

71 |

291 |

1 |

|

|

|

| Perceived Change in Quality of Vaccine and Services |

No |

227 |

64 |

291 |

1.720 |

1.105 |

2.677 |

0.016 |

| |

Yes |

99 |

48 |

147 |

1 |

|

|

|

Table 6.

Socio-Demographics Factors that Influence Under-immunization.

Table 6.

Socio-Demographics Factors that Influence Under-immunization.

| |

|

|

95% CI |

|

| |

|

No |

Yes |

Total |

aOR |

Lower |

Upper |

p-Value |

|

| Health Area |

Bokwango |

45 |

16 |

61 |

1.296 |

0.656 |

2.557 |

0.455 |

|

| |

Buea Road |

136 |

45 |

181 |

1.392 |

0.844 |

2.297 |

0.195 |

|

| |

Buea Town |

56 |

10 |

66 |

2.580 |

1.197 |

5.560 |

0.016 |

|

| |

Molyko |

89 |

41 |

130 |

1 |

|

|

|

|

| Age of Caregiver |

22-30 |

171 |

75 |

246 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.999 |

|

| |

31-40 |

109 |

28 |

137 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.999 |

|

| |

41-50 |

38 |

9 |

47 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.999 |

|

| |

51-60 |

8 |

0 |

8 |

1.00 |

|

|

|

|

| Age of Child |

0-12 |

95 |

31 |

126 |

1.479 |

0.695 |

3.150 |

0.310 |

|

| |

13-24 |

68 |

22 |

90 |

1.492 |

0.671 |

3.317 |

0.326 |

|

| |

25-36 |

95 |

36 |

131 |

1.274 |

0.605 |

2.682 |

0.524 |

|

| |

37-48 |

39 |

9 |

48 |

2.092 |

0.797 |

5.494 |

0.134 |

|

| |

51-59 |

29 |

14 |

43 |

1 |

|

|

|

|

| Sex of caregiver |

Female |

286 |

98 |

384 |

1.021 |

0.533 |

1.957 |

0.949 |

|

| |

Male |

40 |

14 |

54 |

1 |

|

|

|

|

| Marital Status |

Divorced |

8 |

3 |

11 |

1.455 |

0.277 |

7.637 |

0.658 |

|

| |

Married |

176 |

41 |

217 |

2.341 |

0.818 |

6.699 |

0.113 |

|

| |

Separated |

7 |

14 |

21 |

0.273 |

0.071 |

1.048 |

0.059 |

|

| |

Single |

124 |

48 |

172 |

1.409 |

0.494 |

4.023 |

0.522 |

|

| |

Widowed |

11 |

6 |

17 |

1 |

|

|

|

|

| Level of Education |

No Formal Education |

7 |

5 |

12 |

0.480 |

0.147 |

1.569 |

0.225 |

|

| |

Primary |

25 |

4 |

29 |

2.143 |

0.717 |

6.408 |

0.173 |

|

| |

Secondary |

119 |

43 |

162 |

0.949 |

0.602 |

1.496 |

0.821 |

|

| |

University |

175 |

60 |

235 |

1 |

|

|

|

|

| Occupation |

Employed (Government) |

45 |

9 |

54 |

2.338 |

1.032 |

5.296 |

0.042 |

| |

Employed

(Private Sector) |

21 |

4 |

25 |

2.455 |

0.785 |

7.676 |

0.123 |

| |

Self-employed (Business) |

183 |

63 |

246 |

1.358 |

0.833 |

2.213 |

0.219 |

| |

Unemployed |

77 |

36 |

113 |

1 |

|

|

|

| Number of Children |

More than Two |

54 |

20 |

74 |

1.281 |

0.672 |

2.442 |

0.452 |

| |

One |

194 |

55 |

249 |

1.673 |

1.022 |

2.738 |

0.041 |

| |

Two |

78 |

37 |

115 |

1 |

|

|

|

| Monthly Income |

100K-150K |

56 |

13 |

69 |

1.561 |

0.787 |

3.095 |

0.203 |

| |

50K-99K |

103 |

42 |

145 |

0.889 |

0.548 |

1.440 |

0.632 |

| |

Above 150K |

29 |

7 |

36 |

1.501 |

0.619 |

3.643 |

0.369 |

| |

Less than 50K |

138 |

50 |

188 |

1 |

|

|

|

| Religion |

Christian |

307 |

106 |

413 |

0.483 |

0.106 |

2.192 |

0.345 |

| |

Muslim |

7 |

4 |

11 |

0.292 |

0.042 |

2.023 |

0.212 |

| |

Others |

12 |

2 |

14 |

1 |

|

|

|

| Caregiver Status |

Secondary Caregiver |

30 |

24 |

54 |

0.353 |

0.191 |

0.652 |

0.001 |

| |

Shared Responsibility |

101 |

33 |

134 |

0.863 |

0.527 |

1.415 |

0.560 |

| |

Primary caregiver |

195 |

55 |

250 |

1 |

|

|

|

| Housing Situation |

Other |

13 |

14 |

27 |

0.318 |

0.144 |

0.705 |

0.005 |

| |

Owned |

71 |

15 |

86 |

1.623 |

0.882 |

2.988 |

0.120 |

| |

Rented |

242 |

83 |

325 |

1 |

|

|

|

Table 7.

Association of Socio-Cultural and Healthcare Accessibility Factors, and Under-immunization.

Table 7.

Association of Socio-Cultural and Healthcare Accessibility Factors, and Under-immunization.

| |

|

|

95% CI |

| Variable |

Category |

aOR |

Lower |

Upper |

p-Value |

| |

(Intercept) |

0.737 |

0.062 |

8.778 |

0.809 |

| Health Area |

Bokwango |

0.931 |

0.418 |

2.073 |

0.862 |

| |

Buea Road |

1.706 |

0.941 |

3.093 |

0.078 |

| |

Buea Town |

3.046 |

1.270 |

7.306 |

0.013 |

| |

Molyko |

1 |

|

|

|

| Marital Status |

Divorced |

2.310 |

0.348 |

15.330 |

0.386 |

| |

Married |

2.628 |

0.721 |

9.576 |

0.143 |

| |

Separated |

0.188 |

0.040 |

0.895 |

0.036 |

| |

Single |

1.899 |

0.515 |

6.998 |

0.335 |

| |

Widowed |

1 |

|

|

|

| Occupation |

Employed (Government) |

2.348 |

0.846 |

6.519 |

0.101 |

| |

Employed (Private Sector) |

4.295 |

1.139 |

16.196 |

0.031 |

| |

Self-employed (Business) |

1.423 |

0.792 |

2.559 |

0.238 |

| |

Unemployed |

1 |

|

|

|

| Religion |

Christian |

0.184 |

0.029 |

1.173 |

0.073 |

| |

Muslim |

0.105 |

0.011 |

1.048 |

0.055 |

| |

Others |

1 |

|

|

|

| Caregiver Status |

No, another family member is the primary caregiver |

0.481 |

0.229 |

1.008 |

0.053 |

| |

Shared care giving responsibility |

0.554 |

0.305 |

1.008 |

0.053 |

| Housing Situation |

Other |

0.346 |

0.133 |

0.900 |

0.030 |

| |

Owned |

1.623 |

0.761 |

3.462 |

0.210 |

| |

Rented |

1 |

|

|

|

Child Experienced Vaccine

Preventable Disease (VPD)

|

No |

1.564 |

0.872 |

2.806 |

0.134 |

| |

Yes |

1 |

|

|

|

Discussed Vaccination

Concerns with healthcare workers

|

No |

0.603 |

0.358 |

1.016 |

0.058 |

| |

Yes |

1 |

|

|

|

Received Unsolicited

Advice

|

No |

2.055 |

1.232 |

3.429 |

0.006 |

| |

Yes |

1 |

|

|

|

Frequency of

Vaccine Discussion

|

Frequently |

1.676 |

0.953 |

2.946 |

0.073 |

| |

Rarely |

1 |

|

|

|

Proximity to

Health Facility

|

1-5 miles |

2.105 |

0.810 |

5.469 |

0.126 |

| |

5-10 miles |

2.769 |

0.961 |

7.976 |

0.059 |

| |

Less than 1 mile |

2.887 |

1.109 |

7.511 |

0.030 |

| |

More than 10 miles |

1 |

|

|

|

Perceived change

in Quality of Vaccine

services

|

No |

1.881 |

1.100 |

3.216 |

0.021 |

| |

Yes |

1 |

|

|

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).