Submitted:

16 January 2025

Posted:

17 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

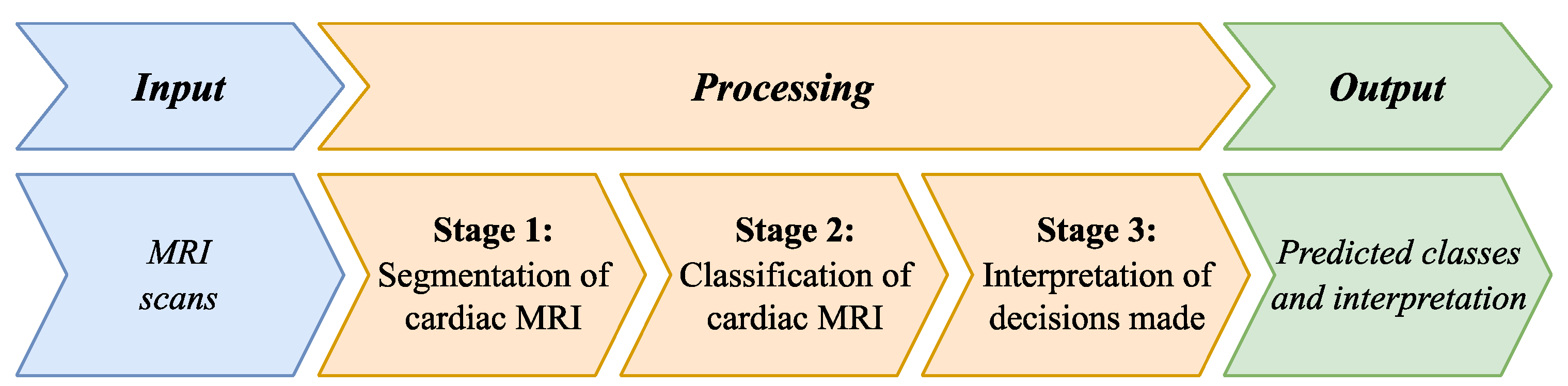

1. Introduction

- A multi-stage method is proposed for segmenting the heart region into the right ventricle (RV), left ventricle (LV), and myocardium, differing from existing approaches by combining the U-Net and ResNet DL models for localizing and segmenting these cardiac structures, followed by Gaussian smoothing for contour refinement and artifact reduction. This method significantly improves segmentation accuracy, with the Dice coefficient reaching 0.974 for LV segmentation and 0.947 for RV segmentation.

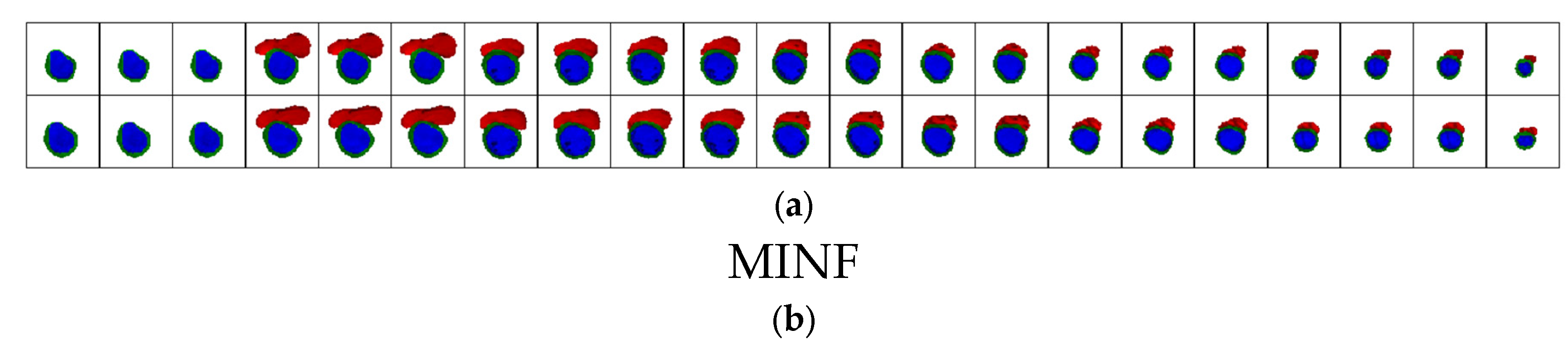

- A cascade classification method for pathologies—dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM), hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM), myocardial infarction with altered left ventricular ejection fraction (MINF), and abnormal right ventricle (ARV)—on MRI scans is proposed. This method differs from existing ones by applying a cascade of DL models to segmented MRI scans, achieving higher disease classification accuracy for the four pathologies under consideration: 0.96, 1.00, 1.00, and 0.90, respectively, and an overall classification accuracy of 0.972.

- A method for interpreting the decisions obtained by DL is proposed, differing from existing approaches by explaining the features used in medical practice, which makes the decisions transparent and comprehensible.

2. Related Works

2.1. Segmentation of Cardiac MRIs

2.2. Classification of Cardiac MRIs

2.3. Interpretation of DL Models

2.4. Aim of the Study and Research Objectives

- Develop a multi-stage segmentation method for dividing the heart region in MRI scans into the RV, LV and myocardium. This method combines U-Net and ResNet models for localizing and segmenting cardiac structures, followed by Gaussian smoothing for contour refinement and artifact reduction.

- Develop a cascade classification method for pathologies—DCM, HCM, MINF, and ARV—in MRIs, to more accurately categorize heart pathologies using segmented MRI data.

- Develop a method for interpreting DL decisions based on clinical features commonly used in medical practice.

3. Methods and Materials

- A multi-stage method for MRI scan segmentation.

- A cascade classification method for pathologies.

- A method for interpreting DL decisions.

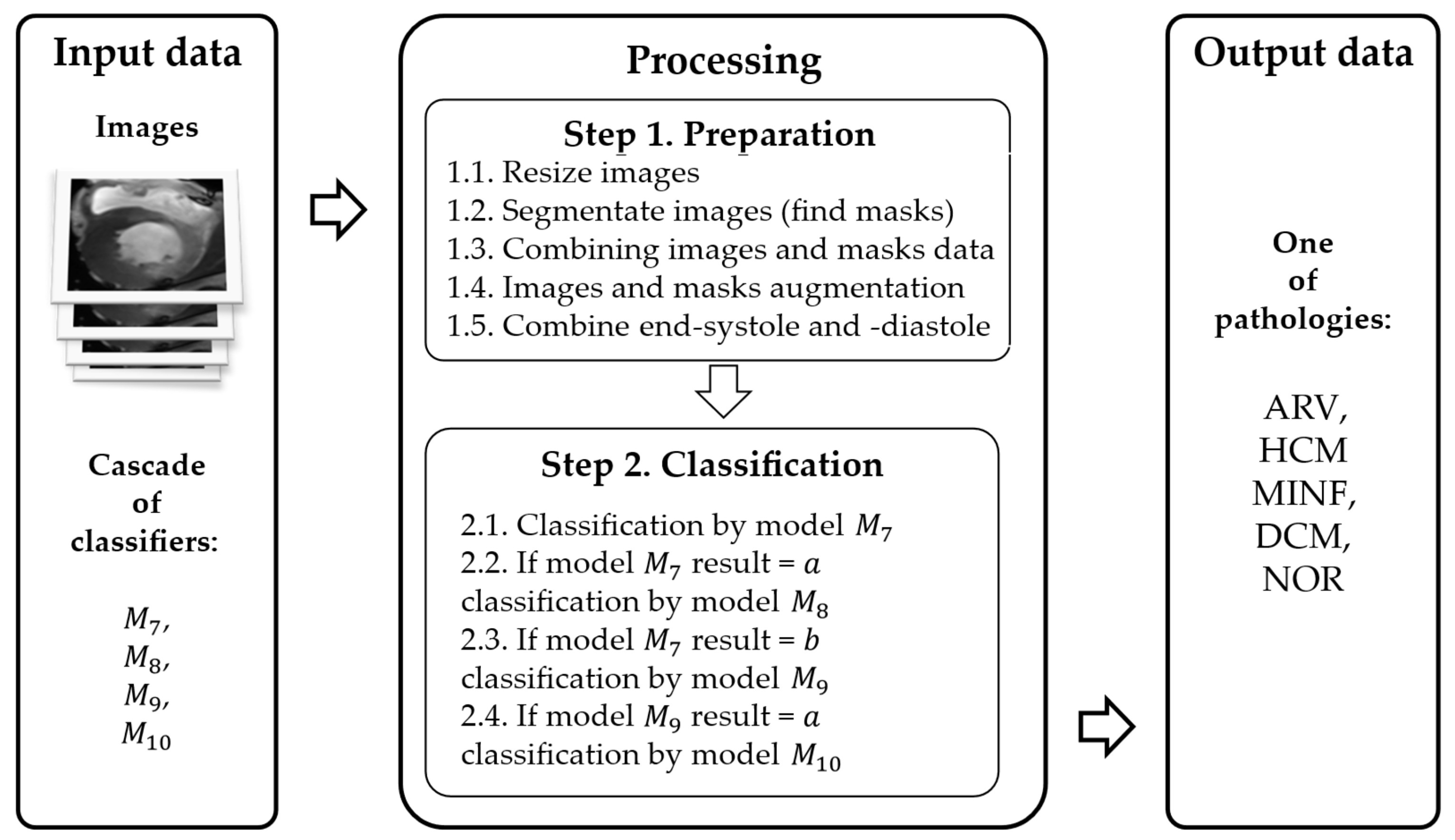

- Instead of analyzing the entire cardiac MRI scan, focus on the localized and segmented areas that are relevant for analysis (RV, LV, and myocardium). This enables the DL model to concentrate on essential regions rather than extraneous information. Isolating this function as a separate task allows for selecting specialized DL models best suited for such preprocessing.

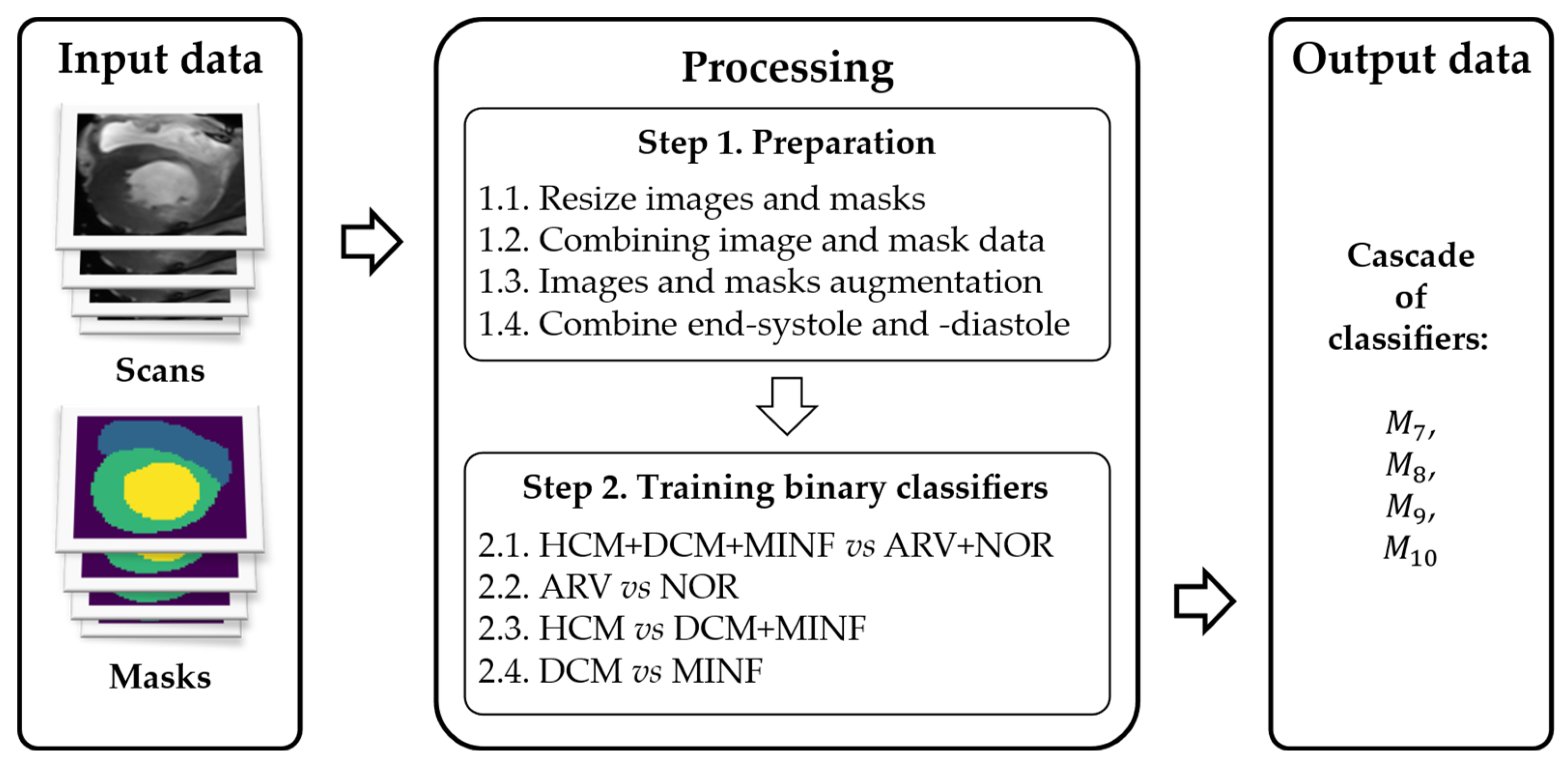

- Medical datasets for classifier training often have limited sample sizes, making it challenging to achieve sufficient model generalization for multiple classes. Class confusion is common. Many approaches have been proposed to address this issue, including data augmentation. Using a cascade of separate binary classifiers for aggregated classes allows the model to increase the number of samples per aggregated class and focus on specific features of two aggregated classes simultaneously, leading to higher classification accuracy.

- In the medical domain, the problem of interpretability of AI models is particularly critical. Addressing this issue is essential to overcome the “black box” effect, which undermines trust in clinical AI outcomes. This study proposes presenting DL-based results in a physician-friendly format through clinically familiar features.

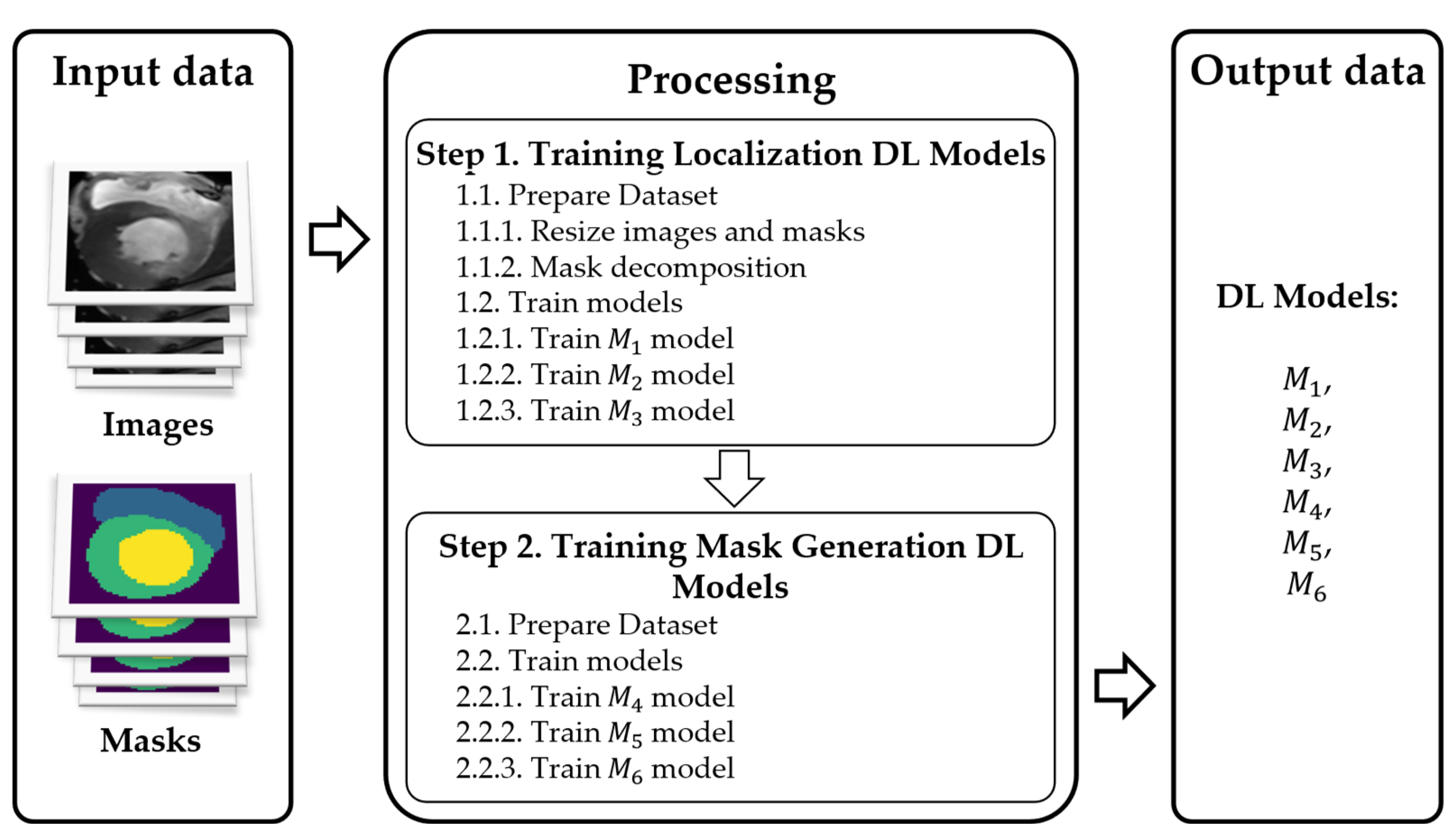

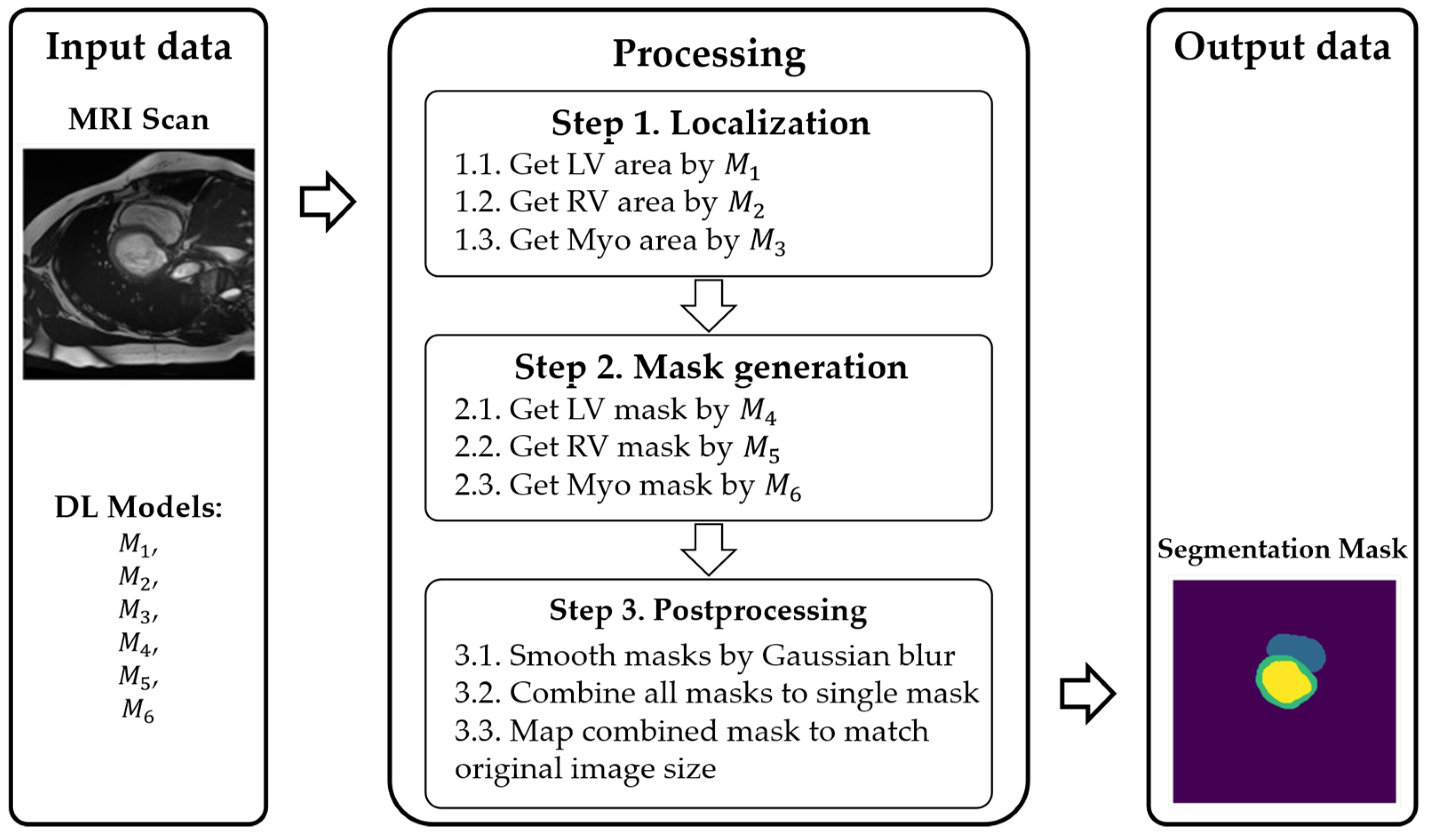

3.1. Method of Multi-Stage Cardiac MRI Segmentation

- Prelocalizing (detecting) LV, RV, and myocardium areas on the MRI scan.

- Using three separate masks instead of a single multistructure one.

- , , : localize LV, RV, and myocardium, respectively.

- , , : refine the contours (masks) for each of those regions.

3.2. Method of Cardiac MRIs Cascade Classification

- Accounting for anatomic heart parameters via certain modifications of an input MRI.

- Using both diastolic and systolic MRI phases.

- A cascade classification model.

- A custom DL architecture.

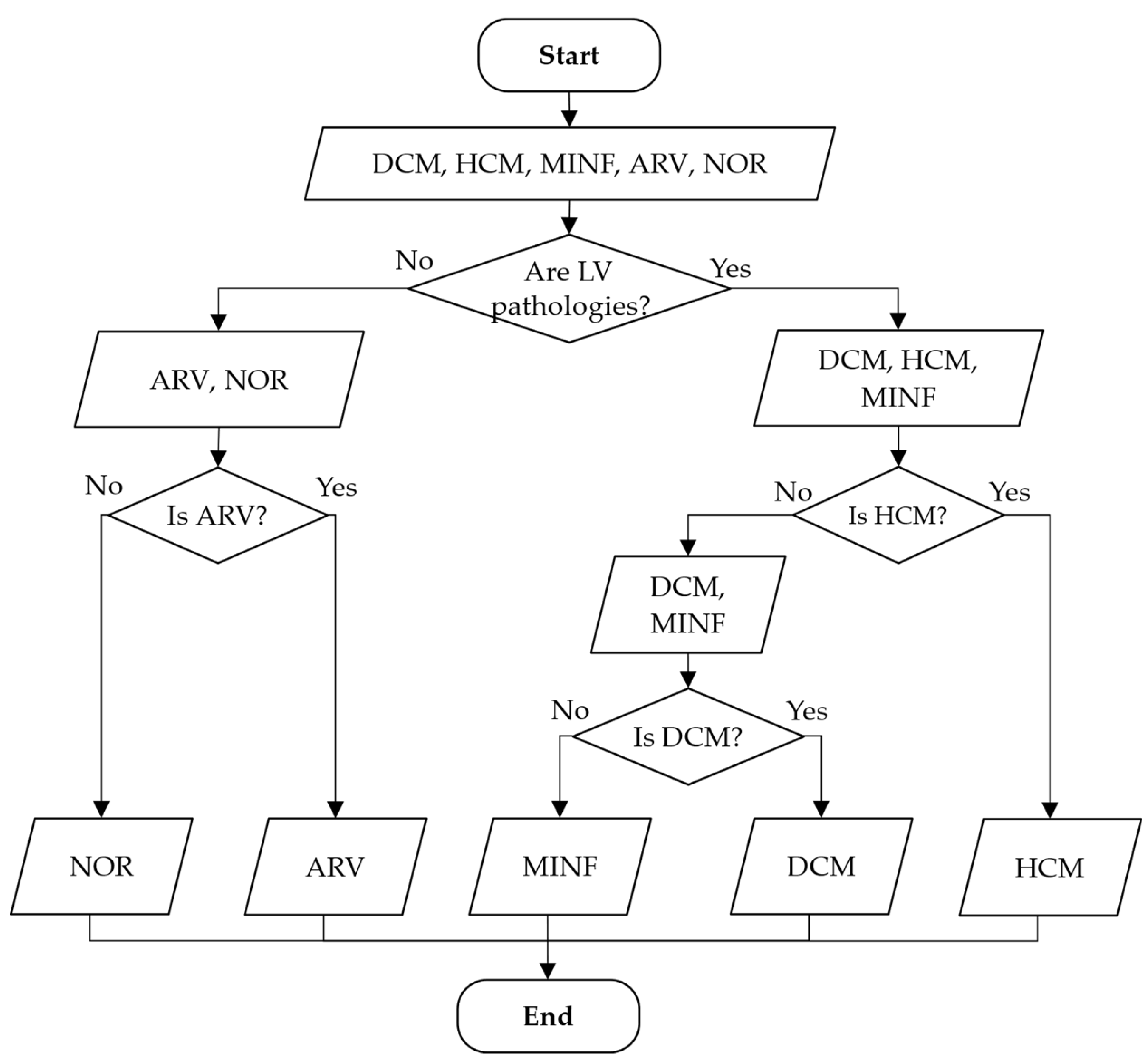

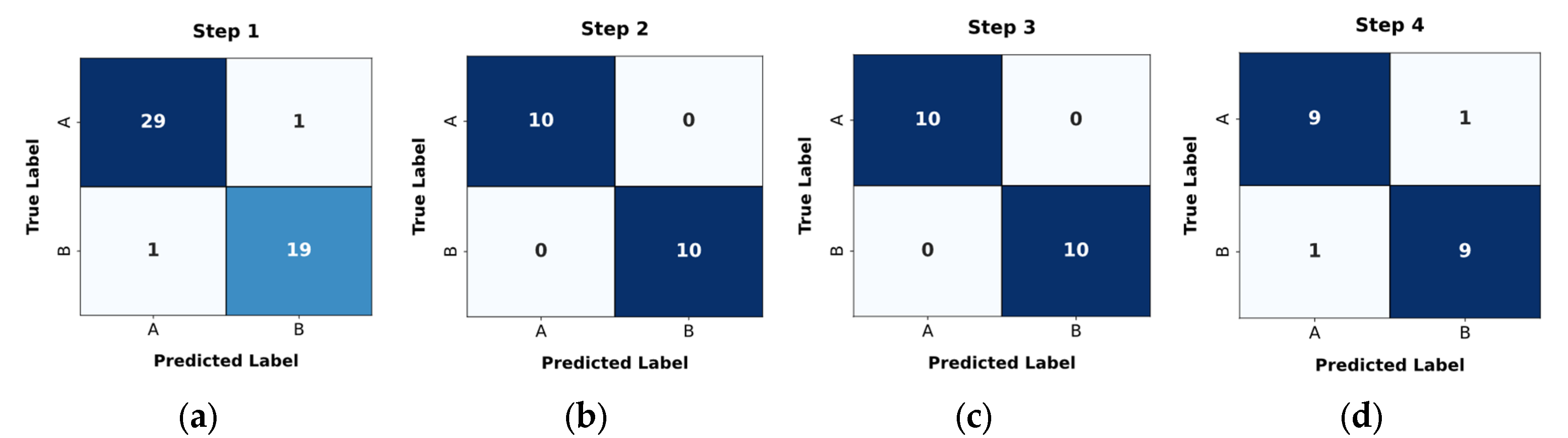

- —class a—aggregation of classes 1 and 5, class b—aggregation of classes 2, 3, and 4. This model separates all LV pathologies from ARV/NOR—LV pathologies vs. ARV/NOR.

- —class a—class 1, class b—class 5. is aimed to distinguish ARV from NOR, i.e., splits ARV vs. NOR.

- —class a—class 2, class b—aggregation of classes 3 and 4. It distinguishes ARV from NOR, i.e., splits ARV vs. NOR.

- —class a—class 4, class b—class 3. This model differentiates MINF from DCM.

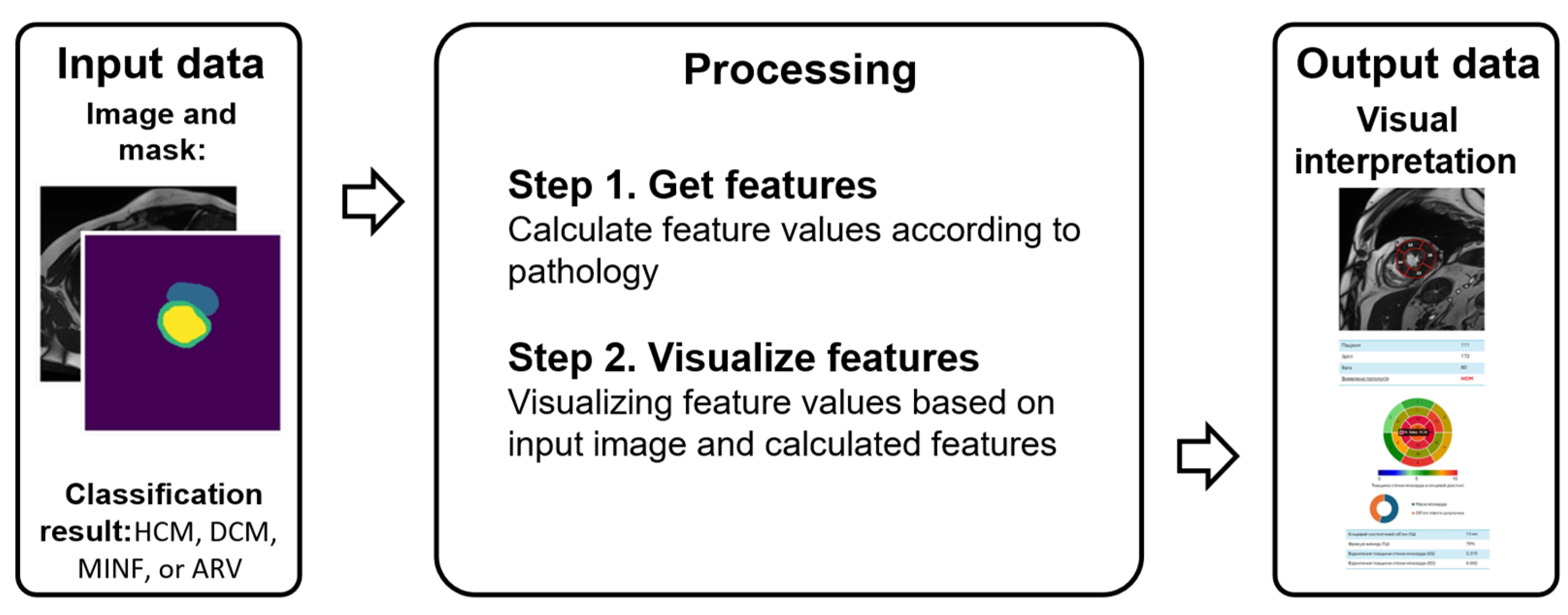

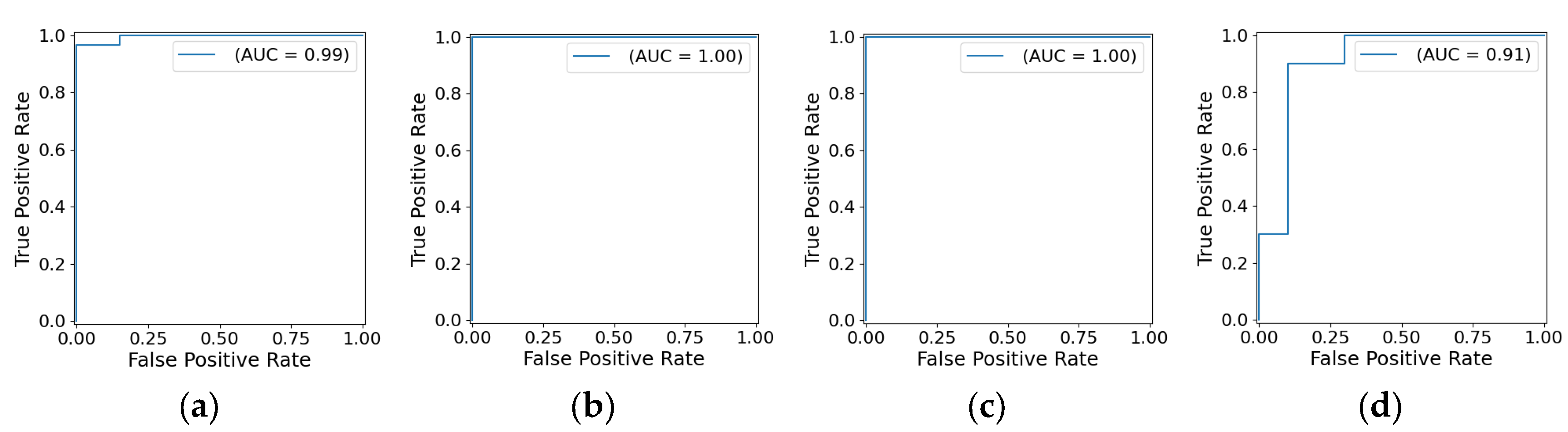

3.3. Method of Interpreting Obtained Decisions based on Cardial MRI

3.3.1. Features Indicating Heart Diseases

3.3.2. Interpretation and Visualization Model

- d = 1—DCM: = (LV ED volume, ); = (LV ES volume, ); = (LV ejection fraction, ); = (myocardial mass at ED, ); = (ratio of myocardial mass to LV ED volume, ); = (maximum average myocardial wall thickness in ED, ).

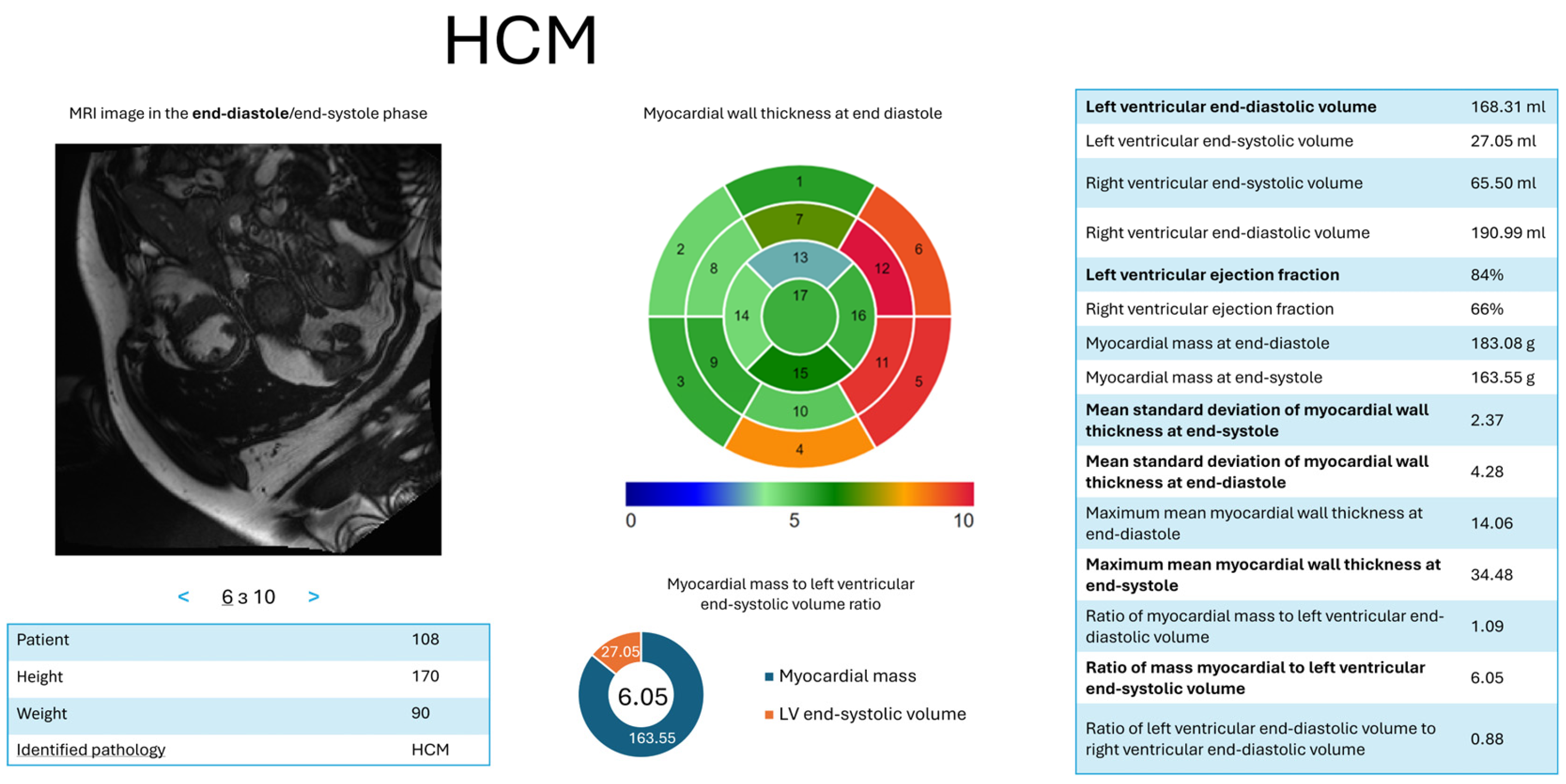

- d = 2—HCM: = (LV ES volume, ); = (LV ejection fraction, ); = (ratio of myocardial mass to LV ES volume, ); = (maximum average myocardial wall thickness in ED, ); = (mean standard deviation of wall thickness in ES, ); = (mean standard deviation of wall thickness in ED, ).

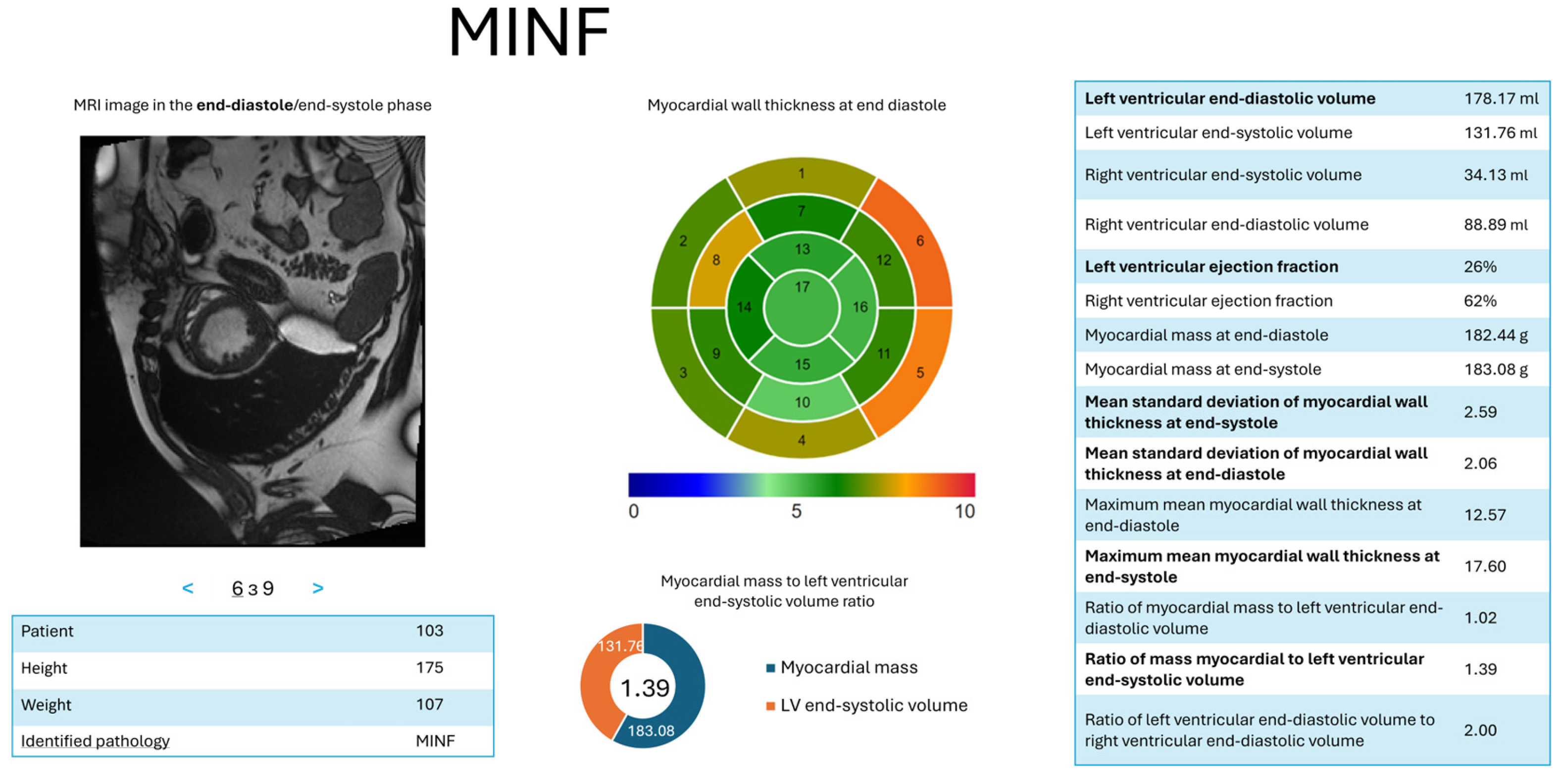

- d = 3—MYOC: = (LV ED volume, ); = (LV ejection fraction, ); = (myocardial mass at (ED), ); = (maximum average myocardial wall thickness in ED), ); = (mean standard deviation of wall thickness in ED, ).

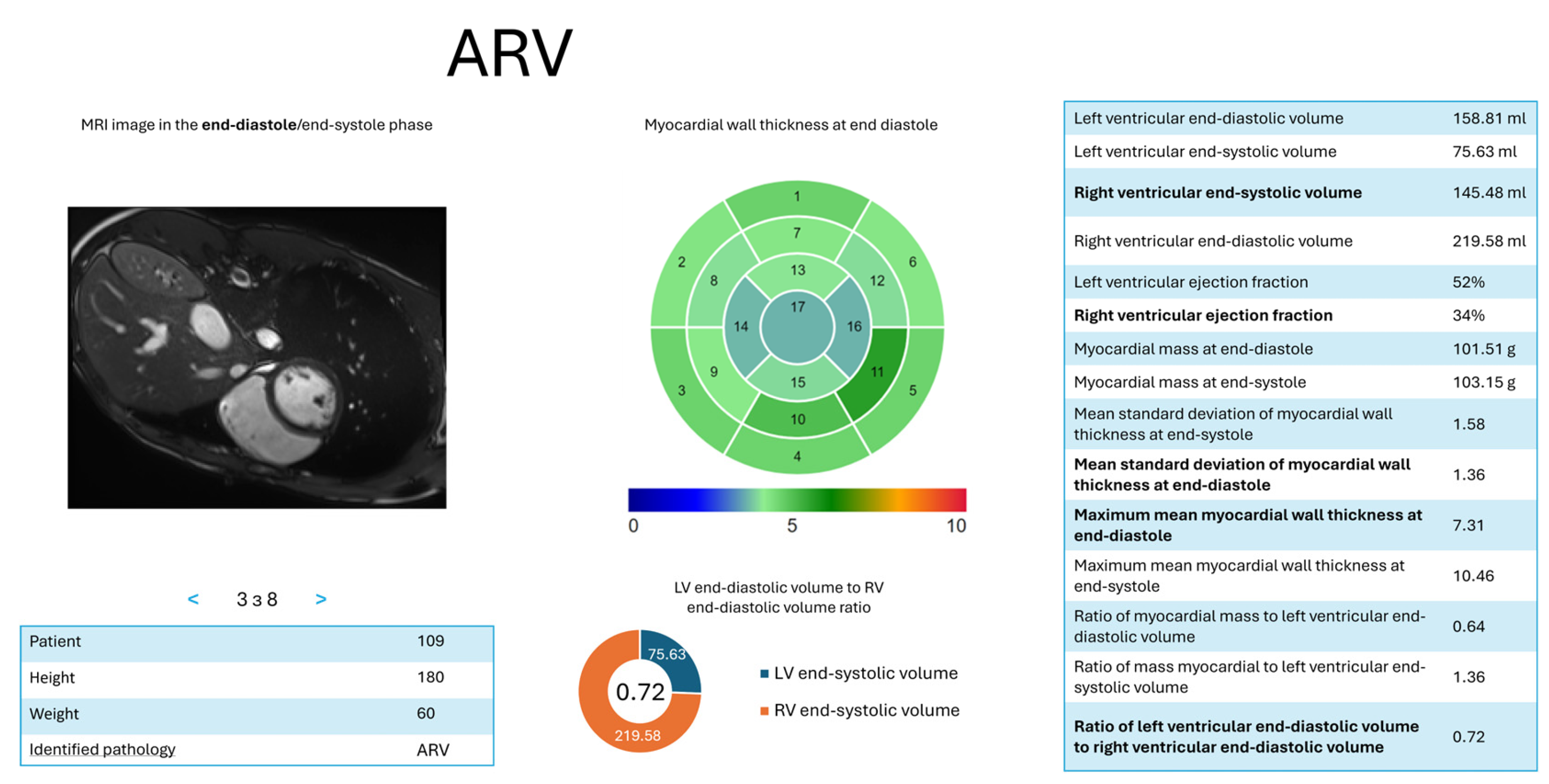

- d = 4—ARV: = (RV ED volume, ); = (RV ejection fraction, ); = (ratio of LV to RV ED volumes, ); = (maximum average myocardial wall thickness in ES, ); = (mean standard deviation of wall thickness in ES,

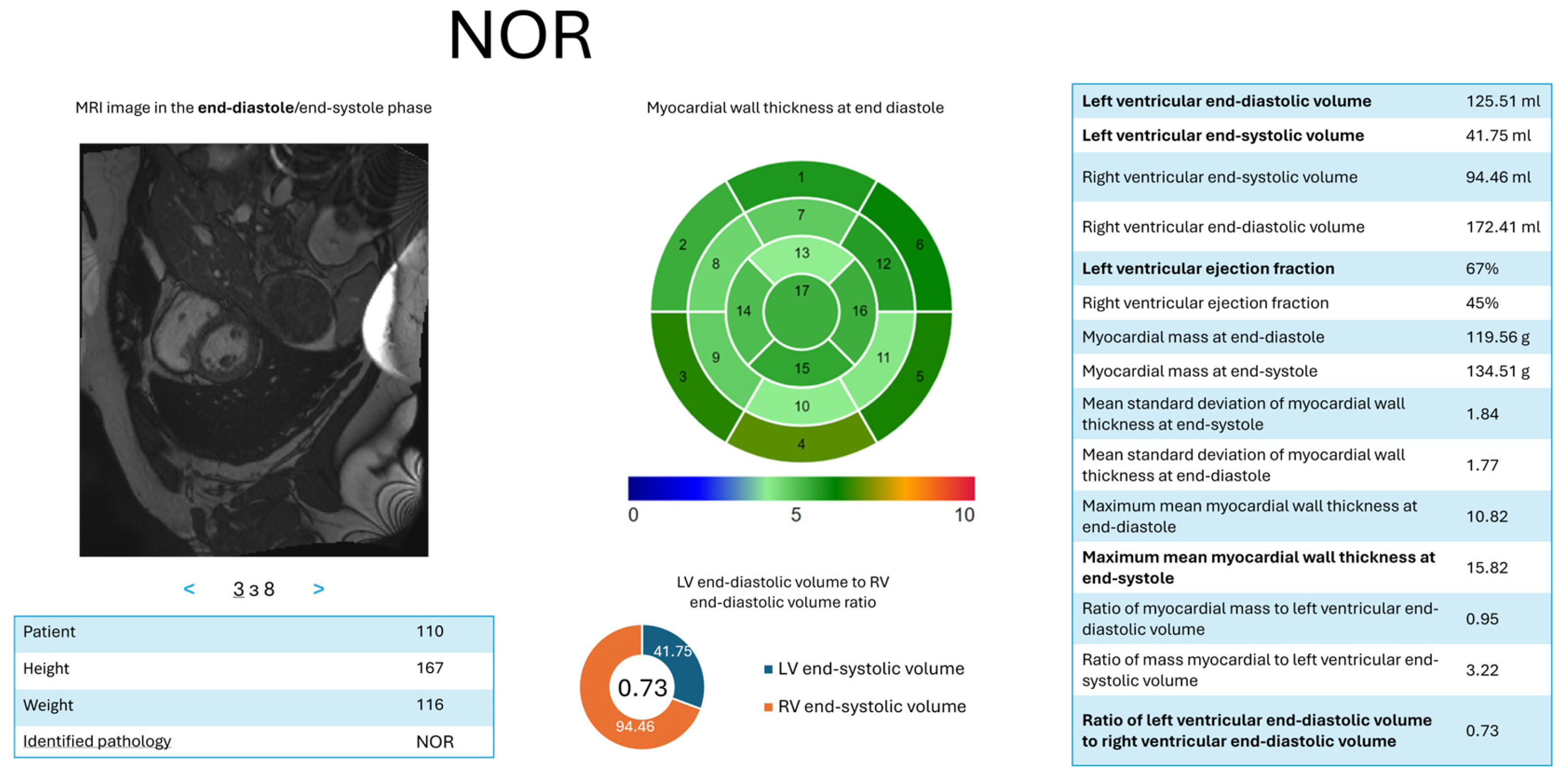

- d = 5—NOR: = (LV ES volume, ); = (LV ED volume, ); = (ratio of LV to RV ED volumes, ); = (LV ejection fraction, ); = (maximum average myocardial wall thickness in ES, ).

3.3.3. Main Steps of the Proposed Method

3.4. Evaluation Approaches and Metrics

3.4.1. Experimental Models for Validating the Multi-Stage Segmentation Method

- Base model : Trained without any optional preprocessing or postprocessing (only uniform resizing). It serves as a baseline for recognizing heart structures on the original ACDC dataset.

- Localization models and : localizes the heart region as a single binary mask, while segments LV, RV, and myocardium within that localized region. Both share the same input ACDC dataset.

- Decomposition models , and : Each model handles binary segmentation of one structure (LV, RV, or myocardium) using decomposed masks. The same ACDC dataset is resized and split accordingly.

3.4.2. Metrics for Evaluating the Cascade Classification Method Results

3.4.3. Evaluation of the Interpretation Method Results

3.5. Dataset

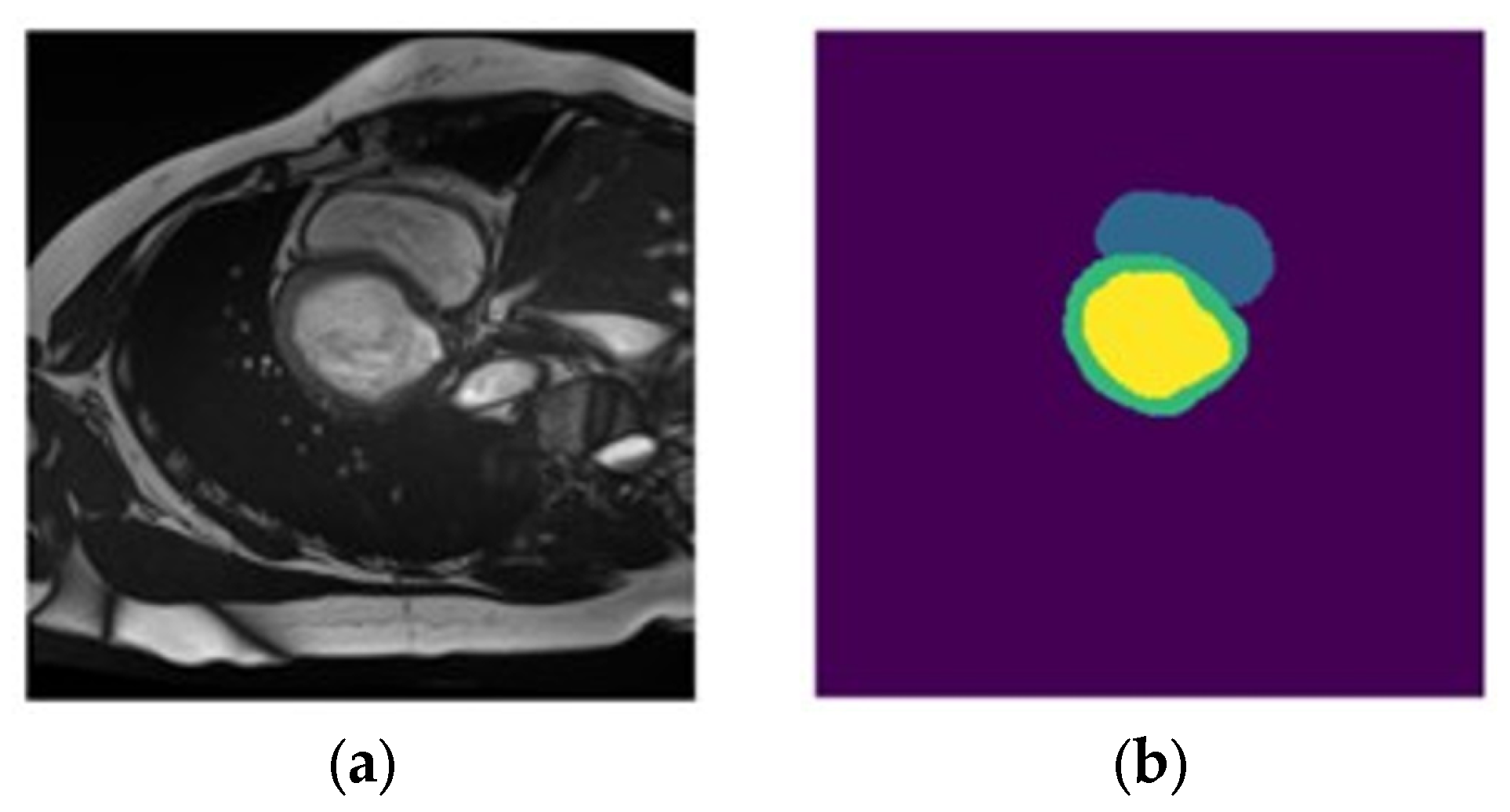

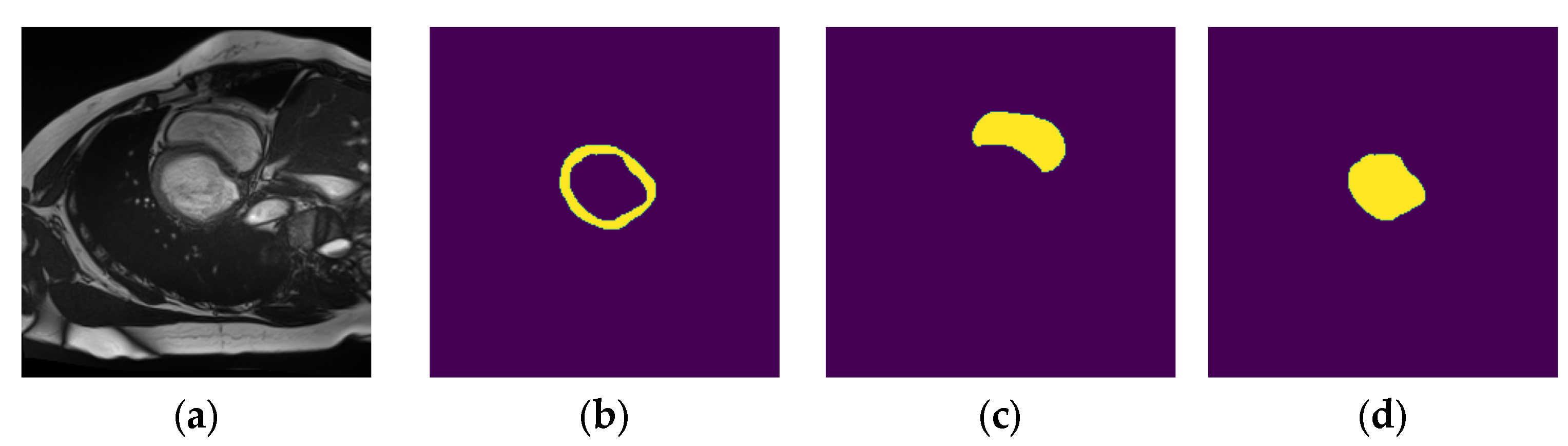

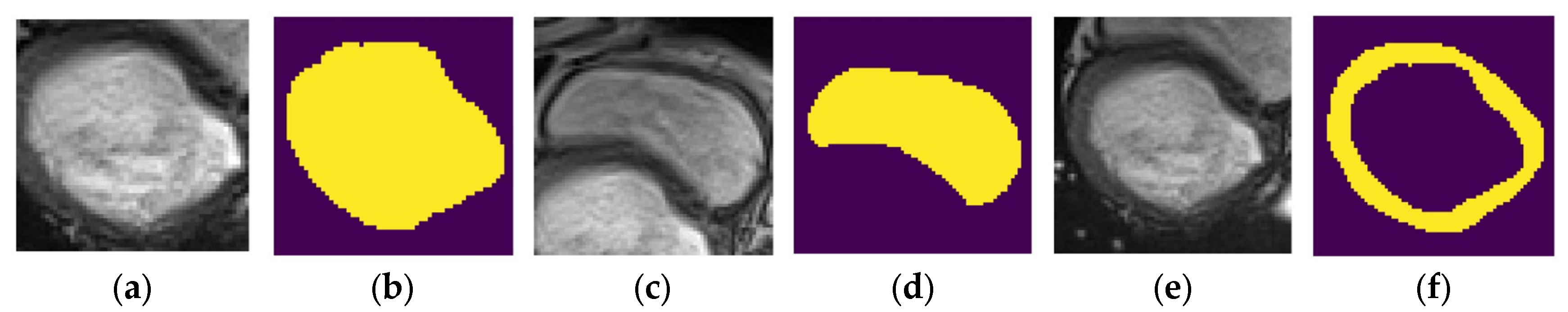

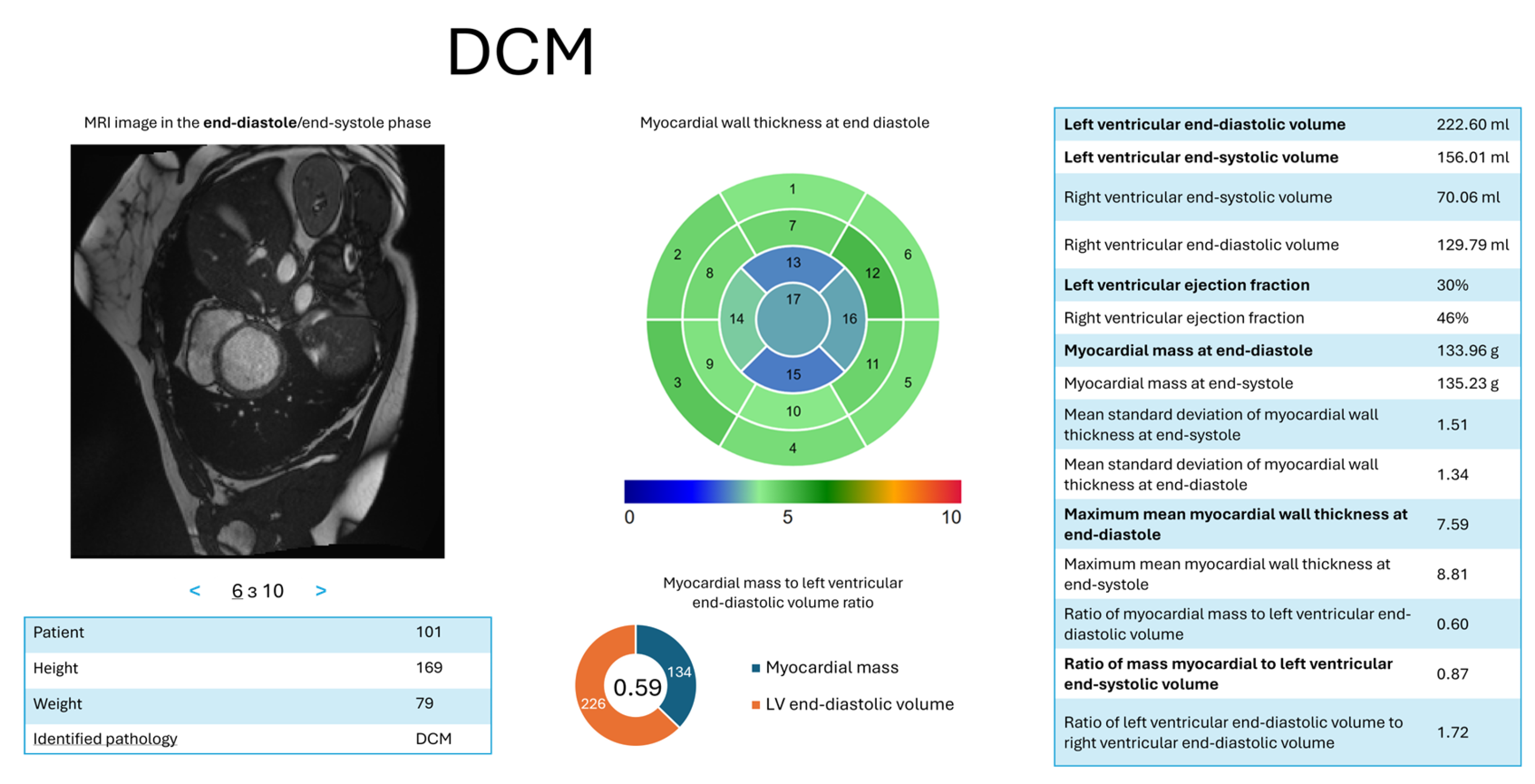

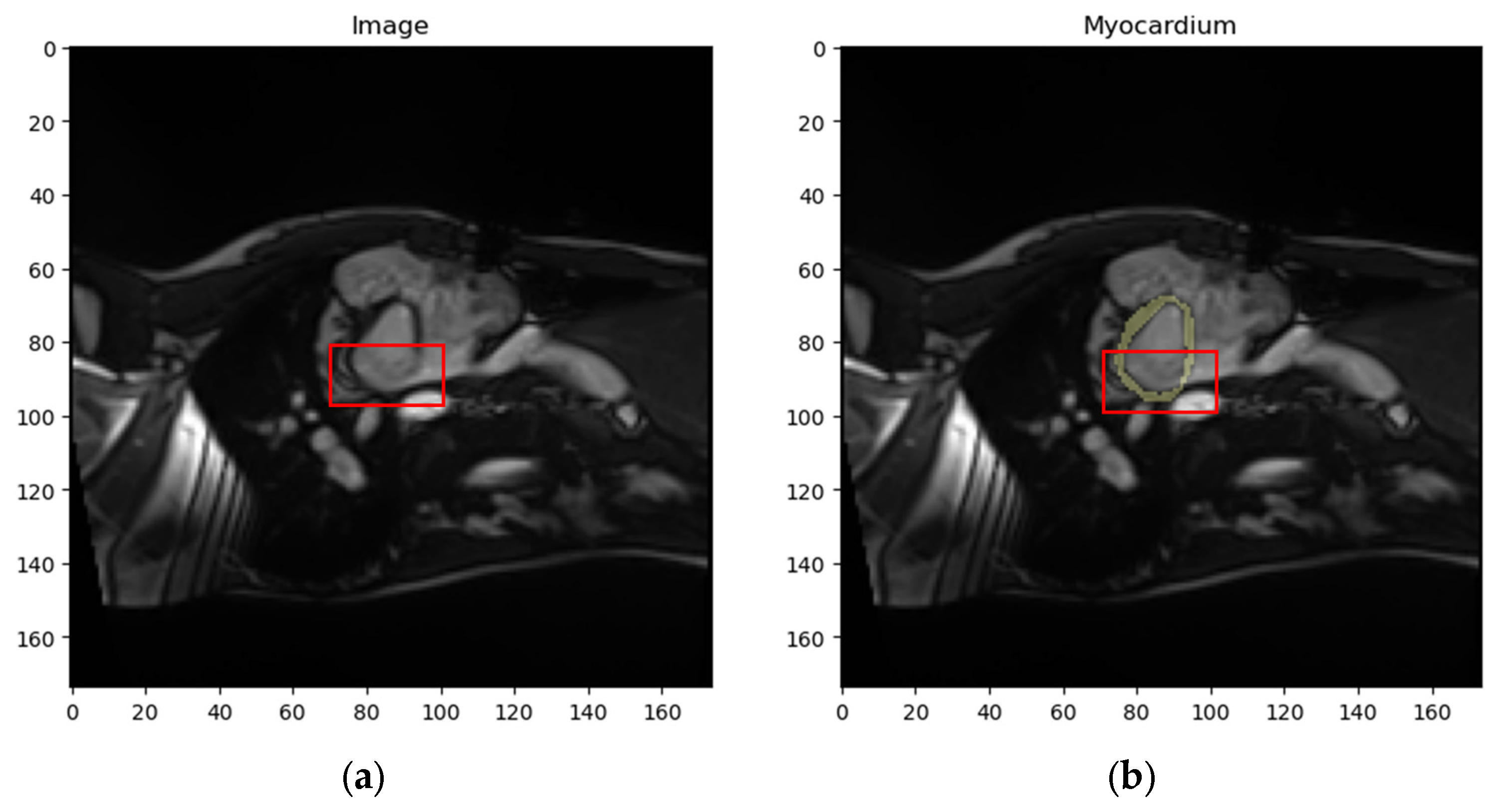

- Dataset : contains localized images of the LV and the corresponding localized mask. An example element of dataset is shown in Figure 11a,b.

- Dataset : contains localized images of the RV and the corresponding localized mask. An example element of dataset is shown in Figure 11c,d.

- Dataset : contains localized images of the myocardium and the corresponding localized mask. An example element of dataset is shown in Figure 11e,f.

4. Results and Discussion

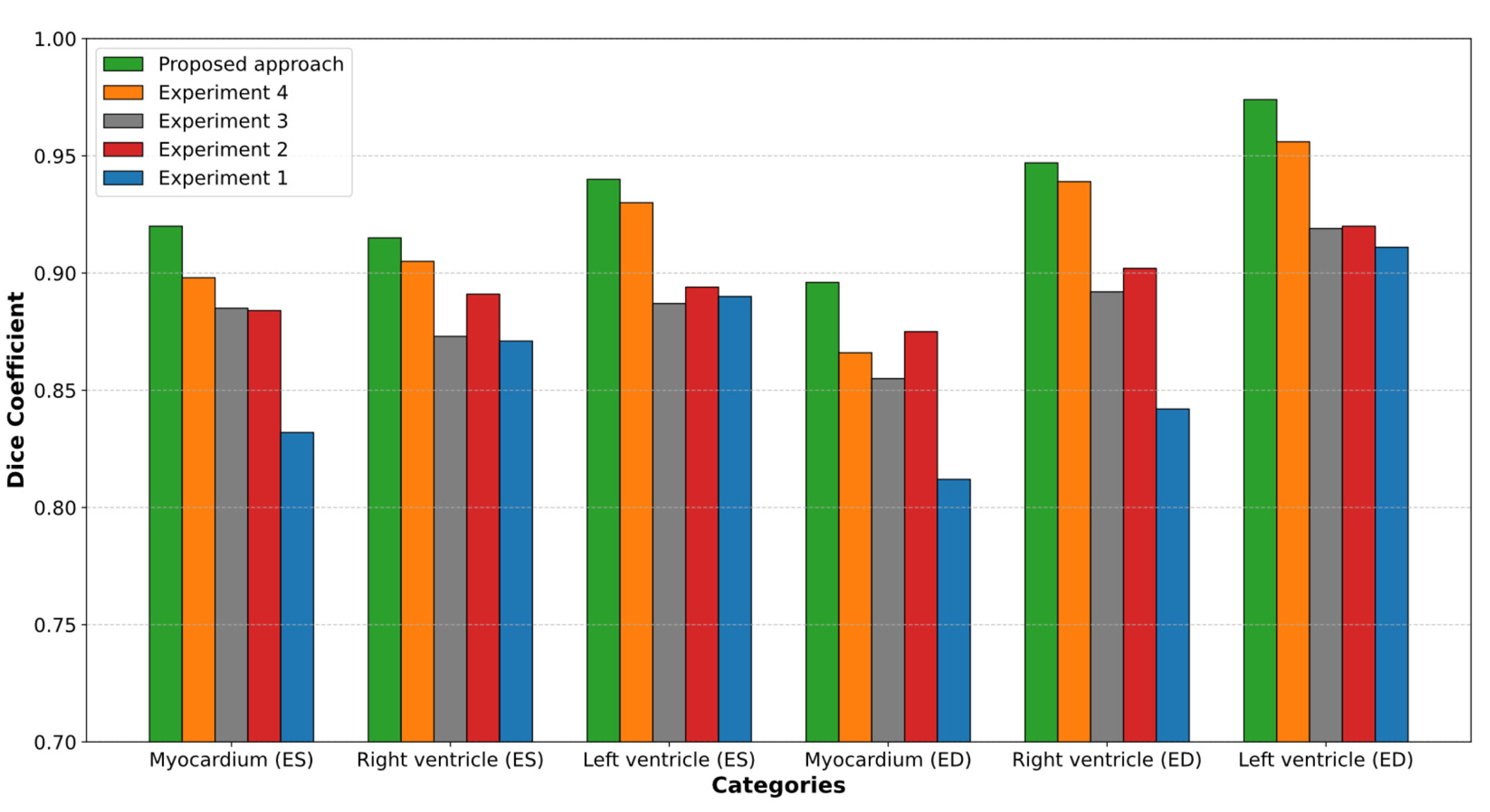

4.1. Results of the Segmentation Method

- Segmentation of original MRI scans: To determine the baseline capability of the DL model to recognize heart structures.

- Segmentation of localized MRI scans using original masks: To evaluate the impact of preliminary localization on the final segmentation result.

- Segmentation of original images using decomposed masks: To assess the use of binary segmentation instead of multi-structure segmentation.

- Segmentation of localized MRI scans using decomposed masks: To evaluate the combination of preliminary localization and binary segmentation instead of multi-structure segmentation.

- Segmentation of localized MRI scans using decomposed masks with postprocessing (proposed approach): To assess the combination of all steps of the proposed method.

4.1.1. Segmentation of Localized MRI Scans using Decomposed Masks with Postprocessing (Proposed Approach)

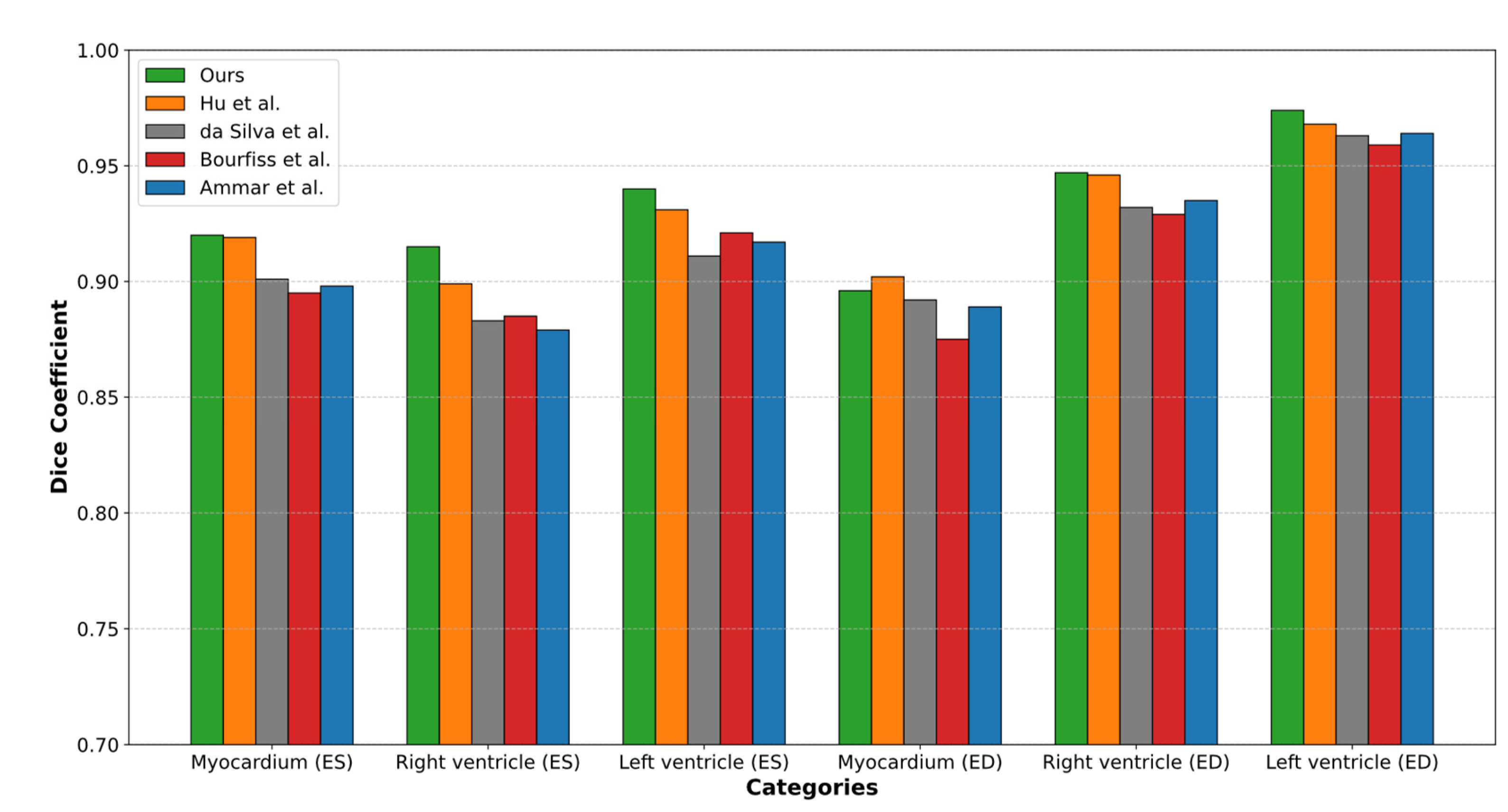

4.1.2. Comparison of the Proposed Approach with Current Segmentation Methods

- 0.54% higher than the results by Hu et al., who reported an accuracy of 0.927.

- 2.08% higher than the results by da Silva et al., who reported an accuracy of 0.913.

- 2.08% higher than the results by Ammar et al., who reported an accuracy of 0.913.

- 2.41% higher than the results by Bourfiss et al., who reported an accuracy of 0.910.

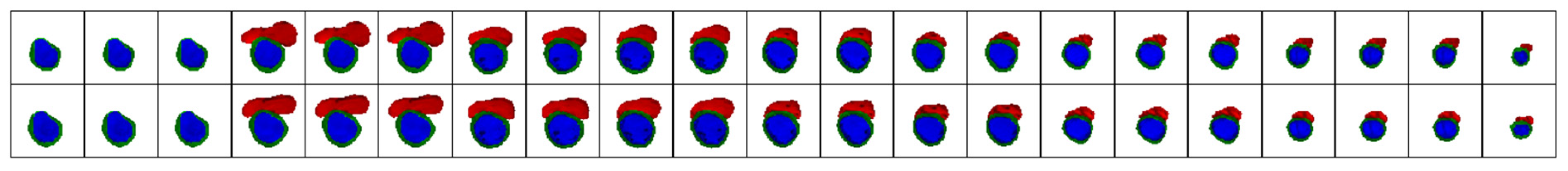

4.1.3. Validation of Expert Masks and Obtained Results by a Medical Specialist

- Myocardium masks: 133 masks generated by the proposed method were deemed more accurate, 56 by experts were more accurate, and 1 mask showed equally poor accuracy.

- LV masks: 136 masks from the proposed method were more accurate, 52 expert masks were more accurate, and 2 masks showed equally poor accuracy.

- RV masks: 122 masks from the proposed method were more accurate, 30 expert masks were more accurate, and 5 masks showed equally poor accuracy.

- Low resolution.

- Image artifacts (e.g., blurring due to patient movement during MRI).

- Low brightness or contrast caused by technical characteristics of the MRI device or challenges during patient imaging.

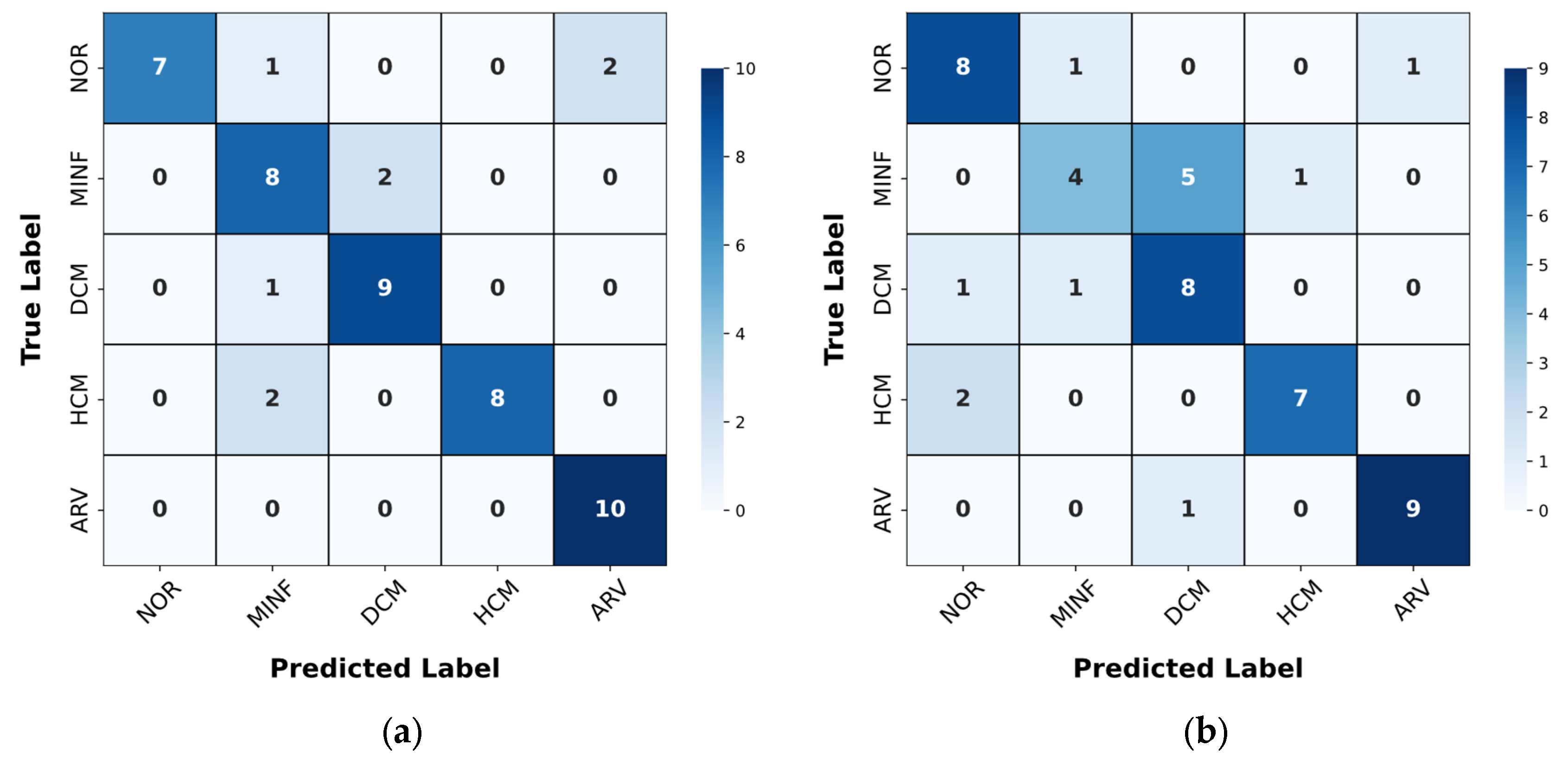

4.2. Results of the Classification Method

4.3. Results of the Interpretation Method

4.4. Limitations of the Proposed Methods

4.5. Discussion of the Results

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACDC | Automated Cardiac Diagnosis Challenge |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| ARV | Abnormal Right Ventricle |

| AUC | Area Under the Curve, a performance measurement for classification models |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| CT | Computed Tomography |

| DCM | Dilated Cardiomyopathy |

| DenseNet | Densely Connected Convolutional Networks |

| Dice | Dice Coefficient |

| DL | Deep Learning |

| D-TCAV | Deep Taylor Concept Activation Vector |

| ED | End-Diastole |

| ES | End-Systole |

| F1-score | F1 Score, the harmonic mean of precision and recall |

| HCM | Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy |

| LV | Left Ventricle |

| MLP | Multilayer Perceptron |

| MRI | Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| NOR | Normal State |

| ResNet | Residual Neural Network |

| RGB | Red, Green, Blue (color channels) |

| ROC | Receiver Operating Characteristic |

| ROI | Region of Interest |

| RV | Right Ventricle |

| SVM | Support Vector Machine |

Appendix A

References

- Morales, M. A.; Manning, W. J.; Nezafat, R. Present and future innovations in AI and cardiac MRI. Radiology 2024, 310, e231269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srinivasan, S.M.; Sharma, V. Applications of AI in cardiovascular disease detection—A review of the specific ways in which AI is being used to detect and diagnose cardiovascular diseases. In AI in Disease Detection; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd., 2025; Volume 6, pp. 123–146 ISBN 978-1-394-27869-5.

- Ball, J. R.; Balogh, E. Improving diagnosis in health care: Highlights of a report from the national academies of sciences, engineering, and medicine. Ann. Intern. Med. 2016, 164, 59–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Invisible numbers: The true extent of noncommunicable diseases and what to do about them; World Health Organization: Geneva, 2022; p. 42; Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- Counseller, Q.; Aboelkassem, Y. Recent technologies in cardiac imaging. Front. Med. Technol. 2023, 4, 984492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rose, N.E.; Gold, S.M. A comparison of accuracy between clinical examination and magnetic resonance imaging in the diagnosis of meniscal and anterior cruciate ligament tears. Arthroscopy: The Journal of Arthroscopic & Related Surgery 1996, 12, 398–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramer, C. M.; Barkhausen, J.; Bucciarelli-Ducci, C.; Flamm, S. D.; Kim, R. J.; Nagel, E. Standardized cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging (CMR) protocols: 2020 update. J. Cardiovasc. Magn. Reson. 2020, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haskell, M. W.; Nielsen, J.; Noll, D. C. Off-resonance artifact correction for magnetic resonance imaging: A review. NMR Biomed. 2023, 36, e4867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeBenedectis, C. M.; Spalluto, L. B.; Americo, L.; Bishop, C.; Mian, A.; Sarkany, D.; Kagetsu, N. J.; Slanetz, P. J. Health care disparities in radiology—A review of the current literature. J. Am. Coll. Radiol. 2022, 19, 101–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meidert, U.; Dönnges, G.; Bucher, T.; Wieber, F.; Gerber-Grote, A. Unconscious bias among health professionals: A scoping review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 6569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radiuk, P.; Barmak, O.; Manziuk, E.; Krak, I. Explainable deep learning: A visual analytics approach with transition matrices. Mathematics 2024, 12, 1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shick, A. A.; Webber, C. M.; Kiarashi, N.; Weinberg, J. P.; Deoras, A.; Petrick, N.; Saha, A.; Diamond, M. C. Transparency of artificial intelligence/machine learning-enabled medical devices. NPJ Digit. Med. 2024, 7, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radiuk, P.; Barmak, O.; Krak, I. An approach to early diagnosis of pneumonia on individual radiographs based on CNN information technology. Open Bioinform. J. 2021, 14, 93–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.-q.; Gui, W.-h.; Chen, Z.-c.; Tang, J.-t.; Li, L.-y. Medical images edge detection based on mathematical morphology. In 2005 IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology 27th Annual Conference, Proceedings, Shanghai, China, January 17–18, 2006; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2005; pp. 6492–6495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, A.; Wang, L.; Feng, S.; Qu, Y. Threshold-based level set method of image segmentation. In 2010 3rd International Conference on Intelligent Networks and Intelligent Systems (ICINIS), Shenyang, China, November 1–3, 2010; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 703–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cigla, C.; Alatan, A. A. Region-based image segmentation via graph cuts. In 2008 IEEE 16th Signal Processing, Communication and Applications Conference (SIU), Aydin, April 20–22, 2008; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 2272–2275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Song, L.; Liu, S.; Zhang, Y. A review of deep-learning-based medical image segmentation methods. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berezsky, O.; Liashchynskyi, P.; Pitsun, O.; Izonin, I. Synthesis of convolutional neural network architectures for biomedical image classification. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 2024, 95, 106325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronneberger, O.; Fischer, P.; Brox, T. U-Net: Convolutional networks for biomedical image segmentation. In Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2015; pp. 234–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badrinarayanan, V.; Kendall, A.; Cipolla, R. SegNet: A deep convolutional encoder-decoder architecture for image segmentation. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2017, 39, 2481–2495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ankenbrand, M. J.; Lohr, D.; Schlötelburg, W.; Reiter, T.; Wech, T.; Schreiber, L. M. Deep learning-based cardiac cine segmentation: Transfer learning application to 7T ultrahigh-field MRI. Magn. Reson. Med. 2021, 86, 2179–2191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radiuk, P.; Kovalchuk, O.; Slobodzian, V.; Manziuk, E.; Krak, I. Human-in-the-loop approach based on MRI and ECG for healthcare diagnosis. In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Informatics & Data-Driven Medicine (IDDM-2022), Lyon, France, 18–20 November 2022; Shakhovska, N., Chretien, S., Izonin, I., Campos, J., Eds.; CEUR-WS: Aachen, Germany, 2022; Volume 3302, pp. 9–20. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, A.; Singh, K. K.; Izonin, I. Responsible and explainable artificial intelligence in healthcare: Conclusion and future directions. In Responsible and Explainable Artificial Intelligence in Healthcare; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2025; с 285–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wehbe, R. M.; Katsaggleos, A. K.; Hammond, K. J.; Hong, H.; Ahmad, F. S.; Ouyang, D.; Shah, S. J.; McCarthy, P. M.; Thomas, J. D. Deep learning for cardiovascular imaging. JAMA Cardiol. 2023, 8, 1089–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandey, S.; Chen, K.-F.; Dam, E. B. Comprehensive multimodal segmentation in medical imaging: Combining YOLOv8 with SAM and HQ-SAM models. In 2023 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision Workshops (ICCVW), Paris, France, October 2–6, 2023; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 2592–2598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azam, M. A.; Khan, K. B.; Salahuddin, S.; Rehman, E.; Khan, S. A.; Khan, M. A.; Kadry, S.; Gandomi, A. H. A review on multimodal medical image fusion: Compendious analysis of medical modalities, multimodal databases, fusion techniques and quality metrics. Comput. Biol. Med. 2022, 144, 105253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.; Pan, N.; Frangi, A. F. Fully Automatic initialization and segmentation of Left and Right ventricles for Large-Scale cardiac MRI using a deeply supervised network and 3D-ASM. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2023, 240, 107679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, I. F. S. d.; Silva, A. C.; Paiva, A. C. d.; Gattass, M.; Cunha, A. M. A multi-stage automatic method based on a combination of fully convolutional networks for cardiac segmentation in short-axis MRI. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 7352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Krishnan, D.; Isola, P. Contrastive multiview coding. In Computer Vision—ECCV 2020; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2020; pp. 776–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Kornblith, S.; Norouzi, M.; Hinton, G. E. A simple framework for contrastive learning of visual representations. In Proceedings of the 37th International Conference on Machine Learning, Virtual Event, July 13–18 2020; pp. 1597–1607. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C.; Amodio, M.; Shen, L. L.; Gao, F.; Avesta, A.; Aneja, S.; Wang, J. C.; Del Priore, L. V.; Krishnaswamy, S. CUTS: A deep learning and topological framework for multigranular unsupervised medical image segmentation. In Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer Nature Switzerland: Cham, 2024; pp. 155–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felfeliyan, B.; Forkert, N. D.; Hareendranathan, A.; Cornel, D.; Zhou, Y.; Kuntze, G.; Jaremko, J. L.; Ronsky, J. L. Self-supervised-RCNN for medical image segmentation with limited data annotation. Comput. Med. Imaging Graph. 2023, 109, 102297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, Q.; Delingette, H.; Ayache, N. Explainable cardiac pathology classification on cine MRI with motion characterization by semi-supervised learning of apparent flow. Med. Image Anal. 2019, 56, 80–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ammar, A.; Bouattane, O.; Youssfi, M. Automatic cardiac cine MRI segmentation and heart disease classification. Comput. Med. Imaging Graphics 2021, 88, 101864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bourfiss, M.; Sander, J.; de Vos, B. D.; te Riele, A. S. J. M.; Asselbergs, F. W.; Išgum, I.; Velthuis, B. K. Towards automatic classification of cardiovascular magnetic resonance Task Force Criteria for diagnosis of arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy. Clin. Res. Cardiol. 2023, 112, 363–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mofrad, F. B.; Valizadeh, G. DenseNet-based transfer learning for LV shape classification: Introducing a novel information fusion and data augmentation using statistical shape/color modeling. Expert Syst. With Appl. 2022, 213, 119261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Las Vegas, NV, USA, June 27–30, 2016; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 770–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, G.; Liu, Z.; Van Der Maaten, L.; Weinberger, K. Q. Densely connected convolutional networks. In 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Honolulu, HI, USA, July 21–26, 2017; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 4700–4708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isensee, F.; Jaeger, P. F.; Full, P. M.; Wolf, I.; Engelhardt, S.; Maier-Hein, K. H. Automatic cardiac disease assessment on cine-MRI via time-series segmentation and domain specific features. In Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2018; pp. 120–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khened, M.; Kollerathu, V. A.; Krishnamurthi, G. Fully convolutional multi-scale residual DenseNets for cardiac segmentation and automated cardiac diagnosis using ensemble of classifiers. Med. Image Anal. 2019, 51, 21–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, A.; Ketabi, S.; Namdar, K.; Khalvati, F. Improving disease classification performance and explainability of deep learning models in radiology with heatmap generators. Front. Radiol. 2022, 2, 991683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, M.; Olanisa, O. O.; Nzeako, T.; Shahrokhi, M.; Esfahani, E.; Fakher, N.; Tabari, M. A. K. Revolutionizing cardiac imaging: A scoping review of artificial intelligence in echocardiography, CTA, and cardiac MRI. J. Imaging 2024, 10, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szabo, L.; Raisi-Estabragh, Z.; Salih, A.; McCracken, C.; Ruiz Pujadas, E.; Gkontra, P.; Kiss, M.; Maurovich-Horvath, P.; Vago, H.; Merkely, B.; et al. Clinician’s guide to trustworthy and responsible artificial intelligence in cardiovascular imaging. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2022, 9, 1016032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janik, A.; Dodd, J.; Ifrim, G.; Sankaran, K.; Curran, K. M. Interpretability of a deep learning model in the application of cardiac MRI segmentation with an ACDC challenge dataset. In Image Processing, Online, February 15–19, 2021; Landman, B. A., Išgum, I., Eds.; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2021; p. 1159636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Jia, H.; Song, J. Accurate classification of non-ischemic cardiomyopathy. Curr. Cardiol. Rep. 2023, 25, 1299–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKenna, W. J.; Maron, B. J.; Thiene, G. Classification, epidemiology, and global burden of cardiomyopathies. Circ. Res. 2017, 121, 722–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernard, O.; Lalande, A.; Zotti, C.; Cervenansky, F. Deep learning techniques for automatic MRI cardiac multi-structures segmentation and diagnosis: Is the problem solved? IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 2018, 37, 2514–2525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slobodzian, V.; Radiuk, P.; Zingailo, A.; Barmak, O.; Krak, I. Myocardium segmentation using two-step deep learning with smoothed masks by gaussian blur. In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Informatics & Data-Driven Medicine (IDDM-2023), Bratislava, Slovakia, 17–19 November 2023; hakhovska, N., Kovac, M., Izonin, I., Chretien, S., Eds.; CEUR-WS: Aachen, Germany, 2024; Volume 3609, pp. 77–91. [Google Scholar]

- Slobodzian, V.; Radiuk, P.; Barmak, O.; Krak, I. Multi-stage segmentation and cascade classification methods for improving cardiac MRI analysis. In Proceedings of the X International Scientific Conference “Information Technology and Implementation” (IT&I 2024), Kyiv, Ukraine, 20–21 November 2024; Anisimov, A., et al., Eds.; CEUR-WS: Aachen, Germany, 2025; Volume 3900, pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Izquierdo, C.; Casas, G.; Martin-Isla, C.; Campello, V. M.; Guala, A.; Gkontra, P.; Rodríguez-Palomares, J. F.; Lekadir, K. Radiomics-based classification of left ventricular non-compaction, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, and dilated cardiomyopathy in cardiovascular magnetic resonance. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2021, 8, 764312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Afshin, M.; Ben Ayed, I.; Punithakumar, K.; Law, M.; Islam, A.; Goela, A.; Peters, T.; Shuo, Li. Regional assessment of cardiac left ventricular myocardial function via MRI statistical features. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 2014, 33, 481–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rainio, O.; Teuho, J.; Klén, R. Evaluation metrics and statistical tests for machine learning. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 6086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Models | ED | ES | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LV | RV | Myocardium of the LV | LV | RV | Myocardium of the LV | |

| 0.911 | 0.842 | 0.812 | 0.890 | 0.871 | 0.832 | |

| , , , , , + postprocessing | 0.974 | 0.947 | 0.896 | 0.940 | 0.915 | 0.920 |

| Experiments | ED | ES | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LV | RV | Myocardium of the LV | LV | RV | Myocardium of the LV | |

| Experiment 1 | 0.911 | 0.842 | 0.812 | 0.890 | 0.871 | 0.832 |

| Experiment 2 | 0.920 | 0.902 | 0.875 | 0.894 | 0.891 | 0.884 |

| Experiment 3 | 0.919 | 0.892 | 0.855 | 0.887 | 0.873 | 0.885 |

| Experiment 4 | 0.956 | 0.939 | 0.866 | 0.930 | 0.905 | 0.898 |

| Experiment 5(proposed approach) | 0.974 | 0.947 | 0.896 | 0.940 | 0.915 | 0.920 |

| Works | ED | ES | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LV | RV | Myocardium of the LV | LV | RV | Myocardium of the LV | |

| Hu et al. [27] | 0.968 | 0.946 | 0.902 | 0.931 | 0.899 | 0.919 |

| da Silva et al. [28] | 0.963 | 0.932 | 0.892 | 0.911 | 0.883 | 0.901 |

| Ammar et al. [34] | 0.964 | 0.935 | 0.889 | 0.917 | 0.879 | 0.898 |

| Bourfiss et al. [35] | 0.959 | 0.929 | 0.875 | 0.921 | 0.885 | 0.895 |

| Ours | 0.974 | 0.947 | 0.896 | 0.940 | 0.915 | 0.920 |

| Description | Number of marked samples | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Myocardium masks | LV masks | RV masks | |

| Mask obtained by the proposed method has higher accuracy | 133 | 136 | 122 |

| Expert-annotated maskhas higher accuracy | 56 | 52 | 30 |

| Both masks have high accuracy, and the difference between masks is insignificant | 1976 | 1962 | 1959 |

| Both masks have low accuracy,insufficient for medical conclusions | 1 | 2 | 5 |

| Classifier | Classes | Precision | Recall | F1-score | Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Classifier 1 | NOR+ARV | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.96 |

| MINF+HCM+DCM | 0.97 | 0.97 | 0.97 | ||

| Classifier 2 | NOR | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| ARV | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Classifier 3 | HCM | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| MINF+DCM | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Classifier 4 | MINF | 0.90 | 0.90 | 0.90 | 0.90 |

| DCM | 0.90 | 0.90 | 0.90 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).